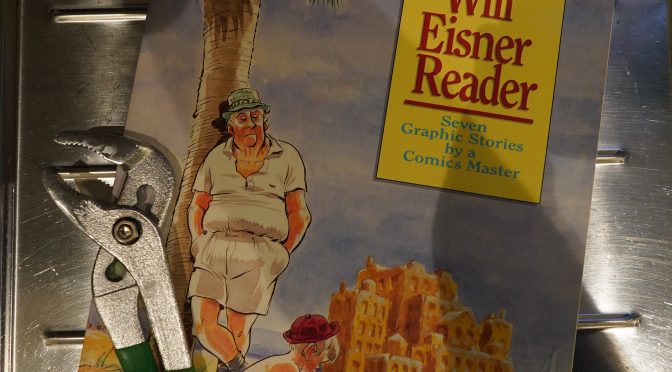

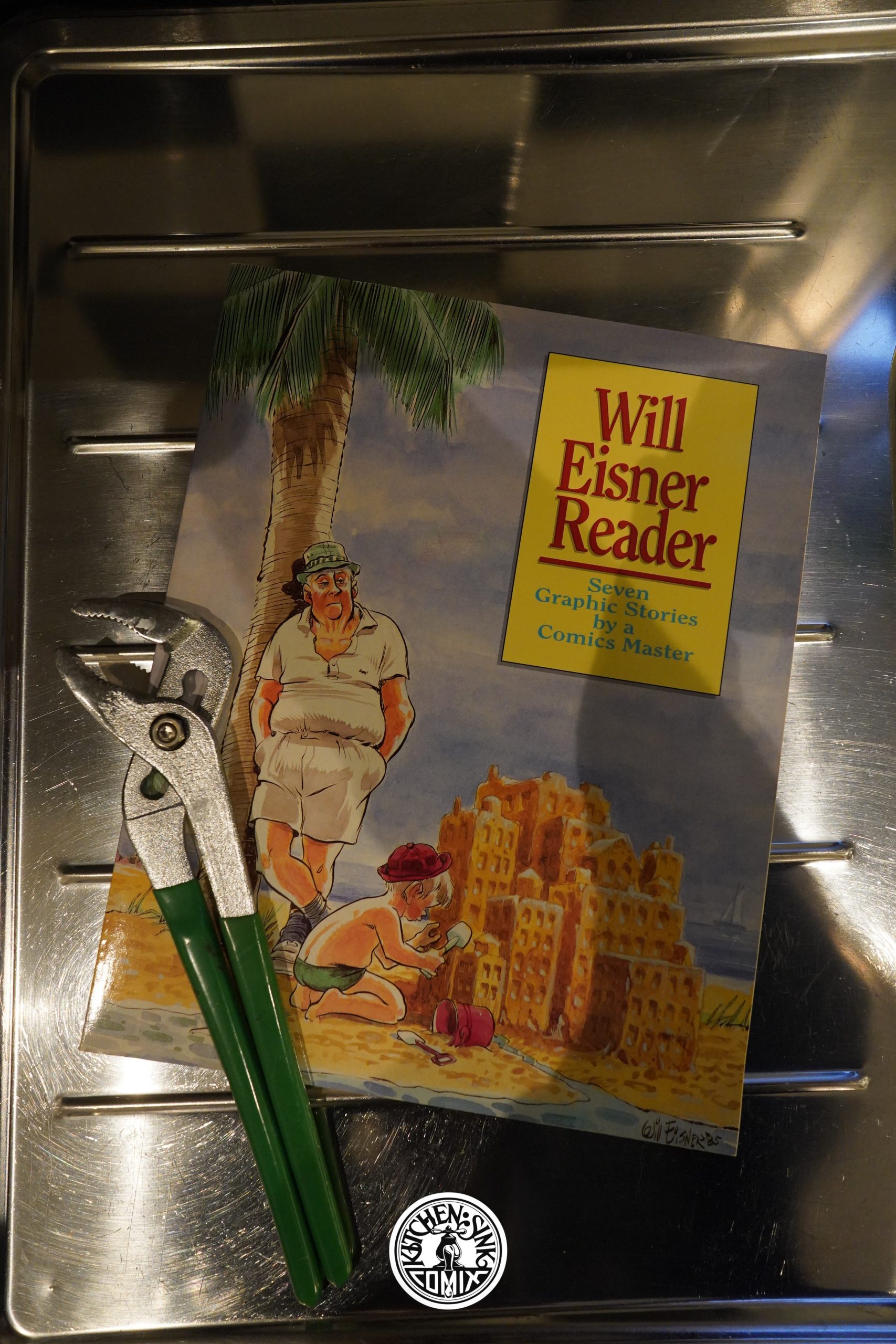

Will Eisner Reader (1991) by Will Eisner

This is a collection of pieces from Will Eisner’s Quarterly…

… so I wasn’t going to re-read these stories, but I ended up doing so, anyway.

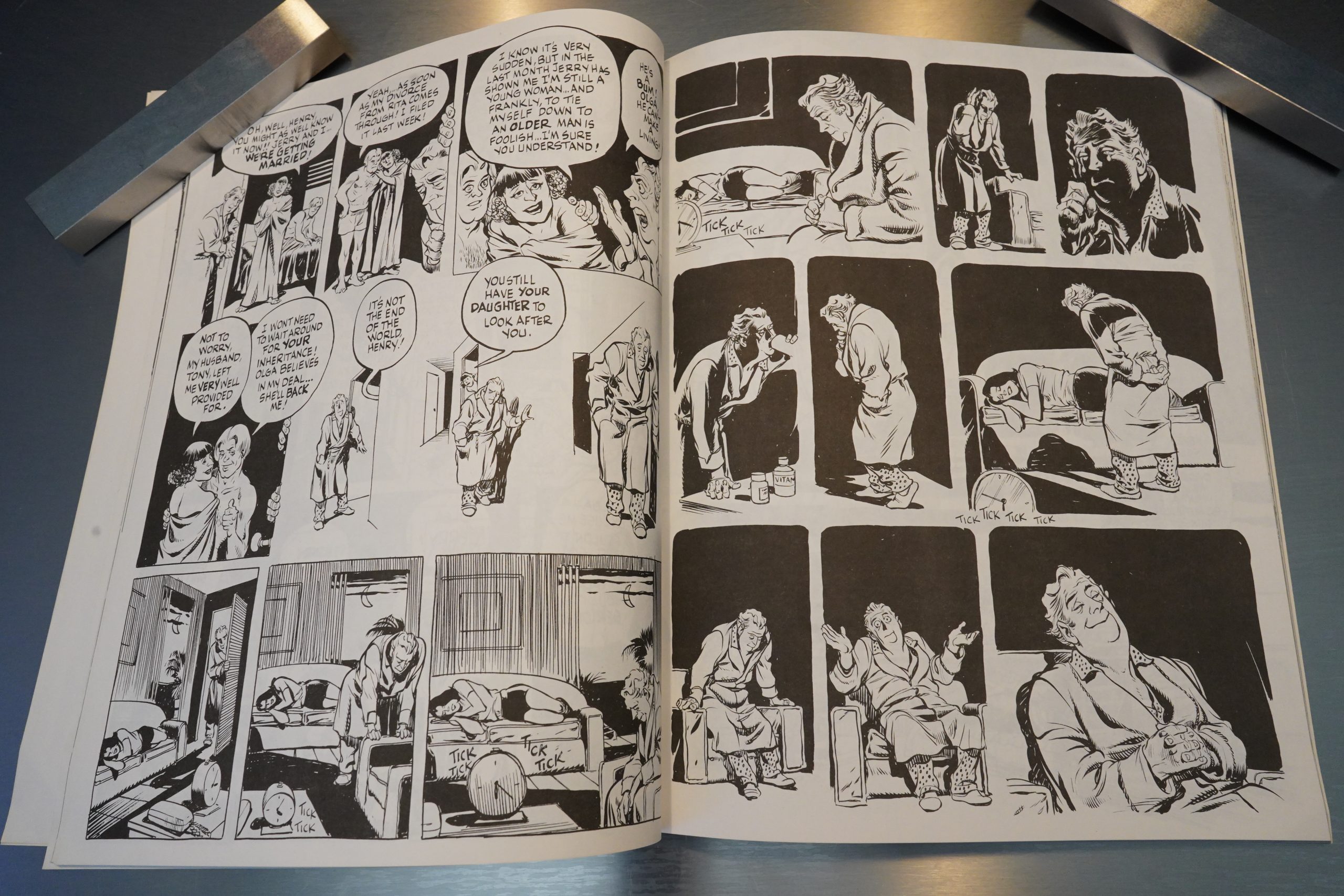

It’s a pretty good selection of works — it includes some of the more satisfying “ironic” stories.

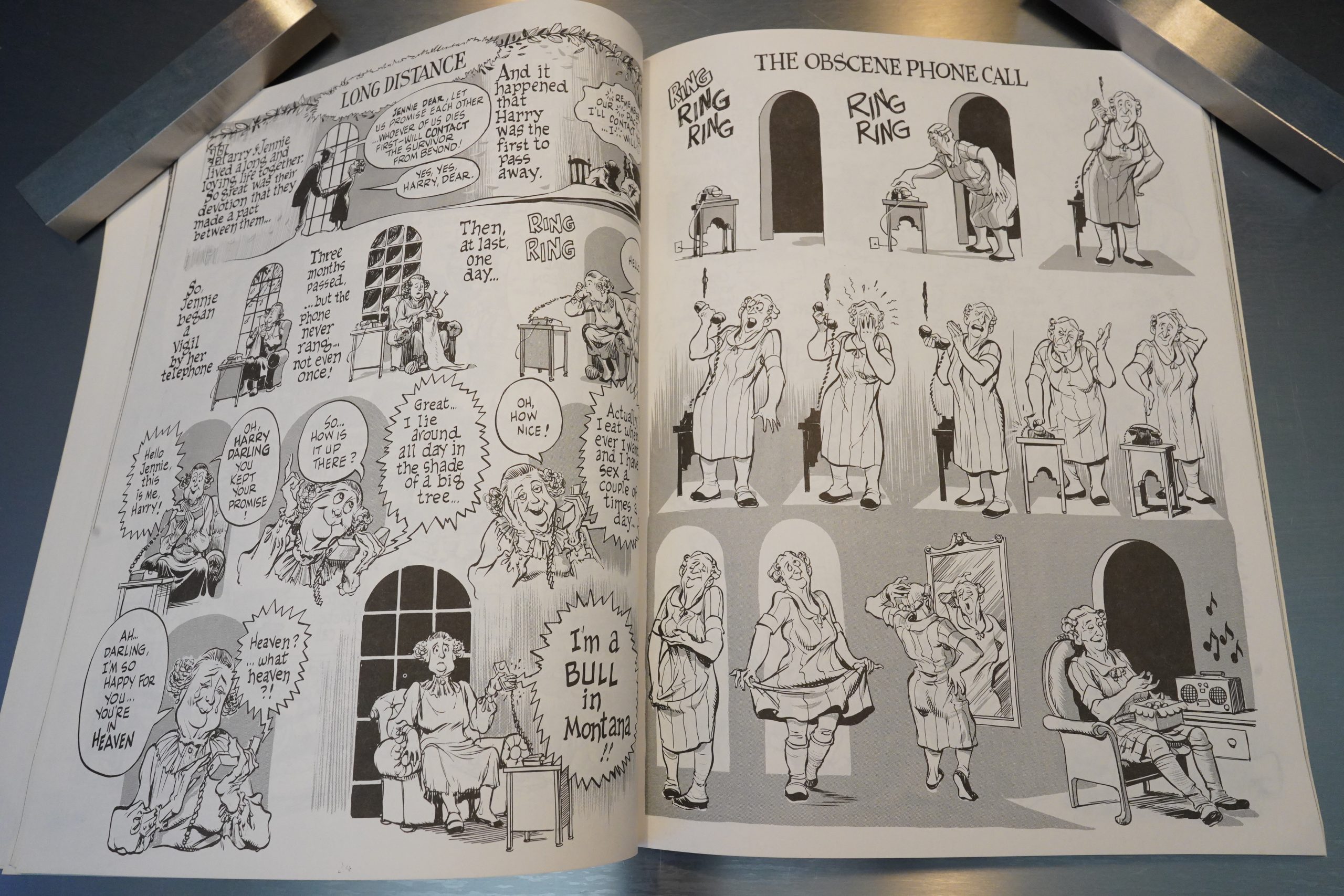

And a collection of one-page slightly off-colour jokes.

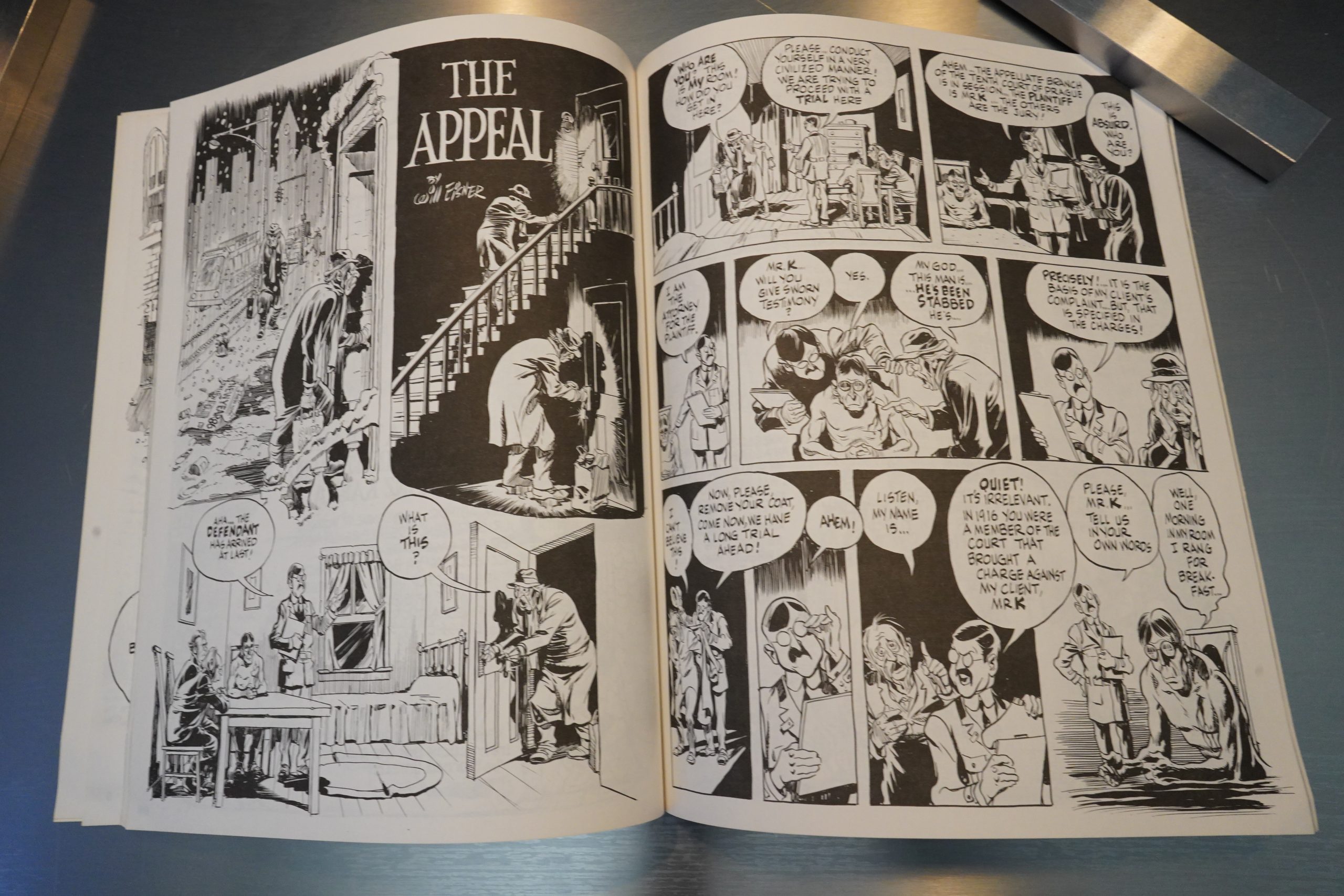

And even a Kafka adaptation.

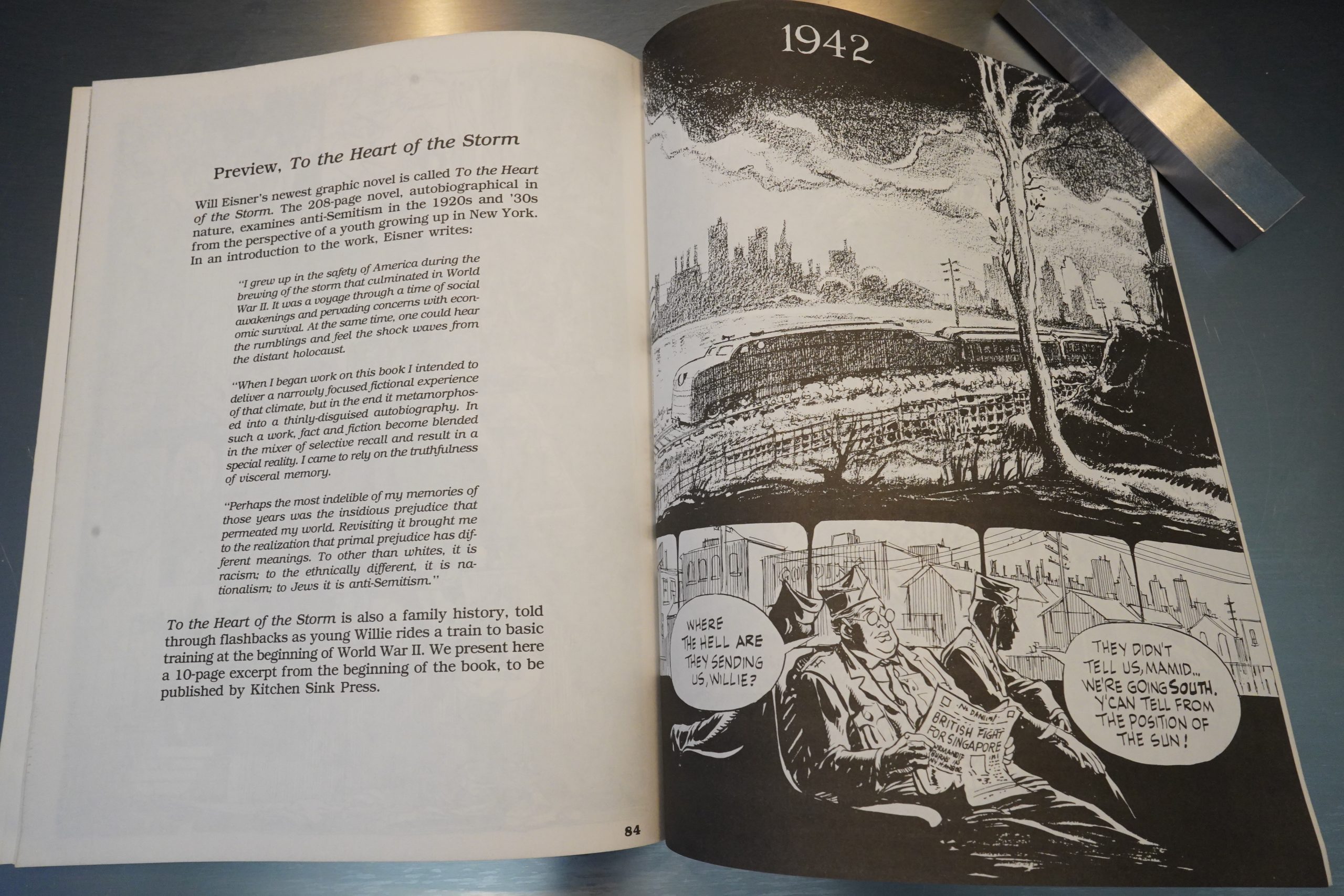

And it ends with an excerpt of To the Heart of the Storm.

It’s a pretty good collection, if you’ve never read any of this stuff. But these stories have also been collected in other books, so…

R. Fiore writes in The Comics Journal #267, page 186:

[…]

The reader may have detected a

certain hedging on my part about the

artistic significance Of the third career. I

must confess that I’ve never derived a great

deal of enjoyment from them. Having spent

a lifetime doing work made to order Eisner

was going to do what pleased him, which

wasn’t necessarily What pleased fans of The

Spirit. What I missed in the later work was

the tightness and virtuoso turns of The

Spirit. I’m going to have to take another

look at it without preconceptions one of

these days. Looking at what I have on hand

(The Will Eisner Reader and To the Heart of

the Storm) dispels some misconceptions. To

begin With, think the Whole third career

has to be considered gravy, a gift from Eisner

to his cult and a gift from his cult to Eisner.

Next, the commonly held belief that there

was a great falling off after A Contract With

God won’t hold water. It would be more

accurate to say that many of us upon reading

Contract concluded (a) that we’d seen late

Eisner and (b) that we’d seen enough of it.

The style of late Eisner is looser than early

Eisner but it’s not loose. He didn’t lose a lot

of skill to age, and he didn’t “grow” a whole

terrible lot. It’s as if he had learned to play

the clarinet, and at a certain point he knew

how; the playing became a little mellower

and less showy With age but didn’t change

much in its essentials. The virtuosity of

The Spirit I suspect had more to do with

injecting originality into formulaic material

and later on maintaining interest in subject

matter that had come to bore him. The

stories in the Reader, which are not bad at all

for the most part, are a lot like the material

he was interpolating into the postwar Spirit.

Eisner a natural spinner Of yarns. He

was a sentimental ironist whose sentiment

is leavened by a Lardneresque cynicism

about human nature. He was usually more

sophisticated than hc seemed at first. He

aimed to subvert cliché, but (he subversion

often comes so latc in the Story that cliché is

the dominant impression.

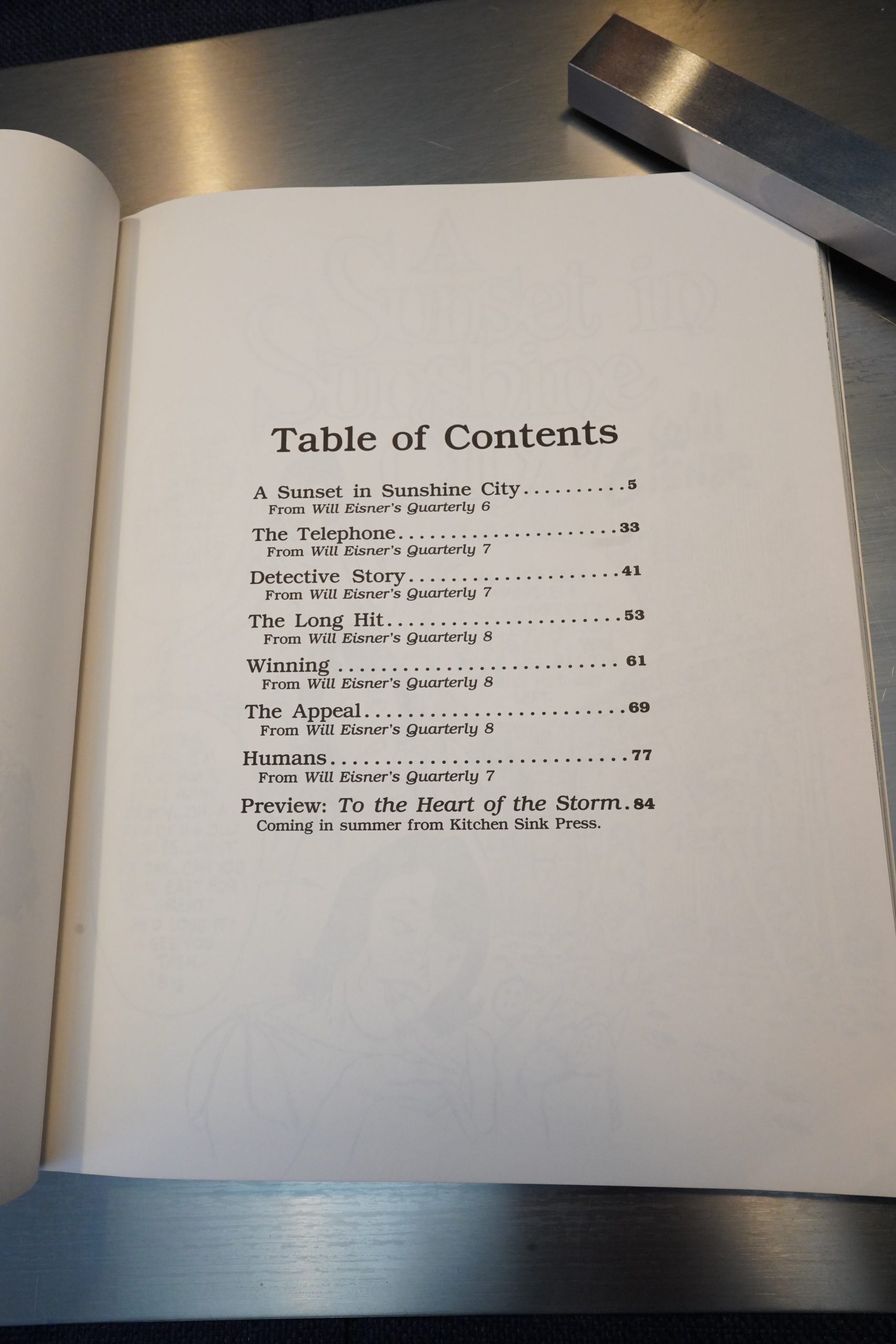

Take “A Sunset in Sunshine City”

from the Reader. It appears to be standard

melodrama: A widower whose business is

slowly fading is convinced by his daughter

to retire [o Florida. As he looks around the

old neighborhood for the last rime his mind

is filled With bittersweet reminiscences about

his domineering Wife and his daughter’s

marriage to a nogoodnik against his wishes.

In Florida he meets a slightly younger fellow

retiree Who pursues him and eventually

convinces him to remarry, though he doesn’t

seem that enthusiastic. This sends a shock

up the coast, because the nogoodnik son-

in-law had been counting on the eventual

inheritance to shore up his shady business

deals. He pressures the daughter to come

down with him to Florida to put the kibosh

on the marriage. It’s not until the last

three pages that the string is pulled. The

nogoodnik has discovered that the matron

has more money than the widower. He asks

her to marry him instead, and she is quite

satisfied to be used in this way if it means a

young man in her bed. Initially the widower

is upset by this development, but in a deft

wordless sequence it dawns on him that

his situation is not nearly as bad as it first

appears. After a lifetime of being pushed

around by every female in his life from Start

to finish, he realizes that his to be divorced

daughter is now entirely dependent on him.

As the story ends he’s got her waiting on him

hand and foot.

In To the Hearn Storm the semi-

autobiographical main character, a recruit

en route to be trained to fight the ultimate

expression Of anti-Semitism, reflects on

episodes of anti-Semitism in his life and the

life of his family. TO begin With, the framing

device is a bir glib. The larger problem,

however, is that he’s addressing subject

matter that’s been done by some of the finest

writers of the last century, and comparisons

are inevitable. And the largest problem is a

failure of reflection, i.e., that if his character

is anything like him then he’s spent the last

several years retailing racial caricatures, and

will resume upon his return. Now, I’m not

one of those people who wrings his hands

over Ebony White, and Eisner had examined

his conscience and found it clear, but not to

confront this issue renders his self-analysis

superficial.

Well, I guess that’s a point…

This is the one hundred and thirty-second post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.