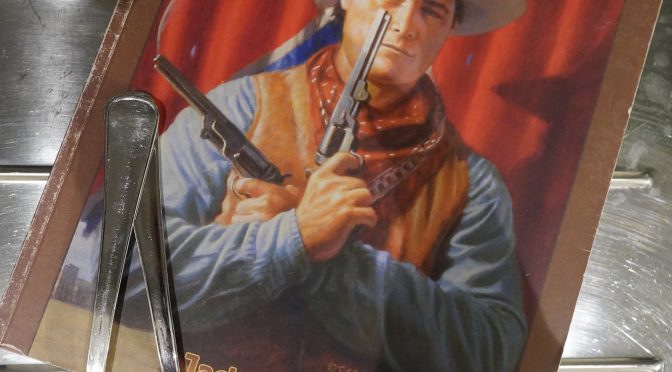

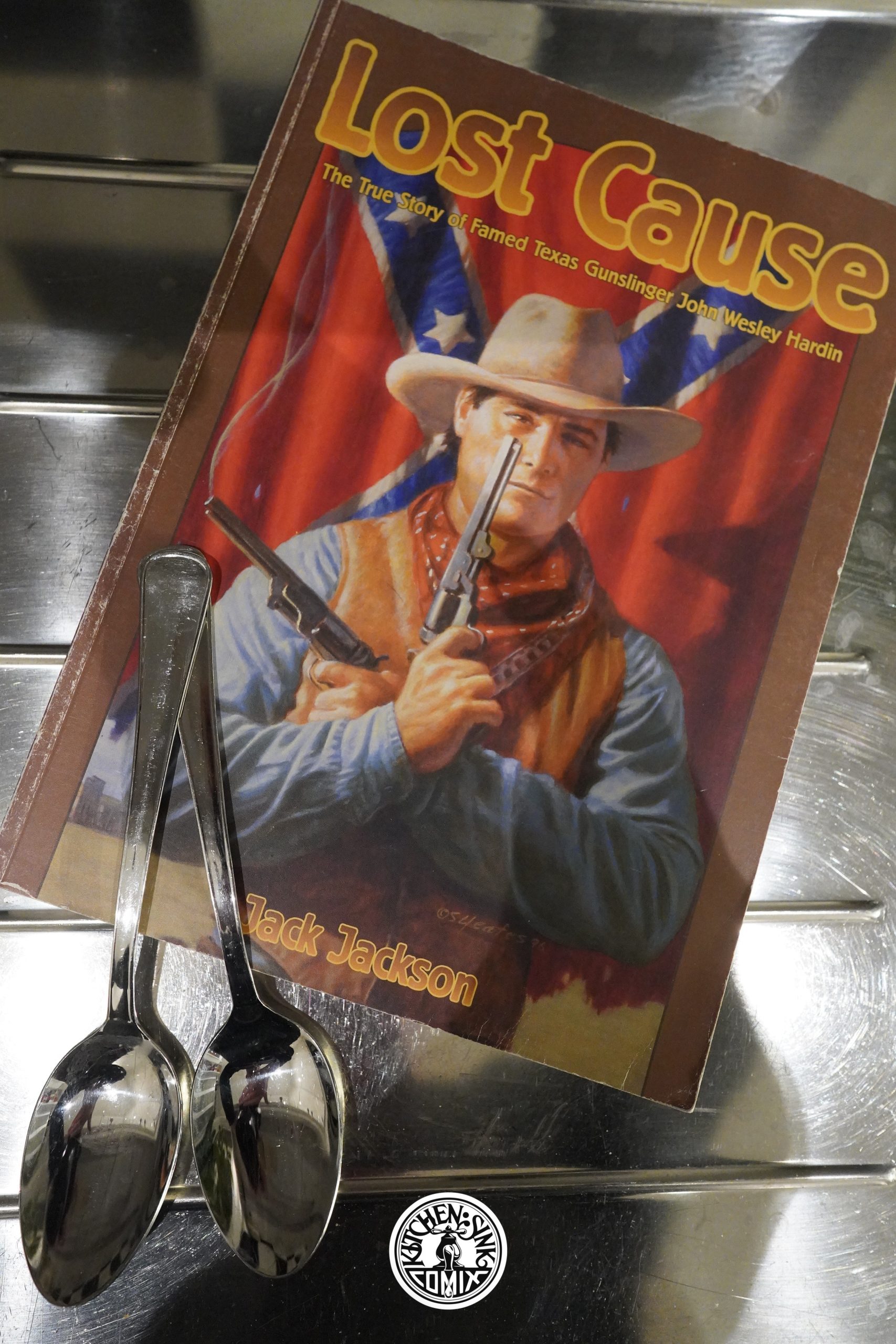

Lost Cause: John Wesley Hardin, the Taylor-Sutton Feud, and Reconstruction Texas (1998) by Jack Jackson

I’m not quite sure what the real title of this is — the cover says “Lost Cause: The True Story of Famed Texas Gunslinger John Wesley Hardin”, but the indicia says that more accurate thing in the link above.

Anyway, I’m sort of a Jack Jackson fan (or Jaxon, as called himself back in the day), and have been since before I was a teenager. I’m not quite sure why, because his obsessions are mostly not mine. That is, I don’t really have any particular interest in the history of Texas and stuff.

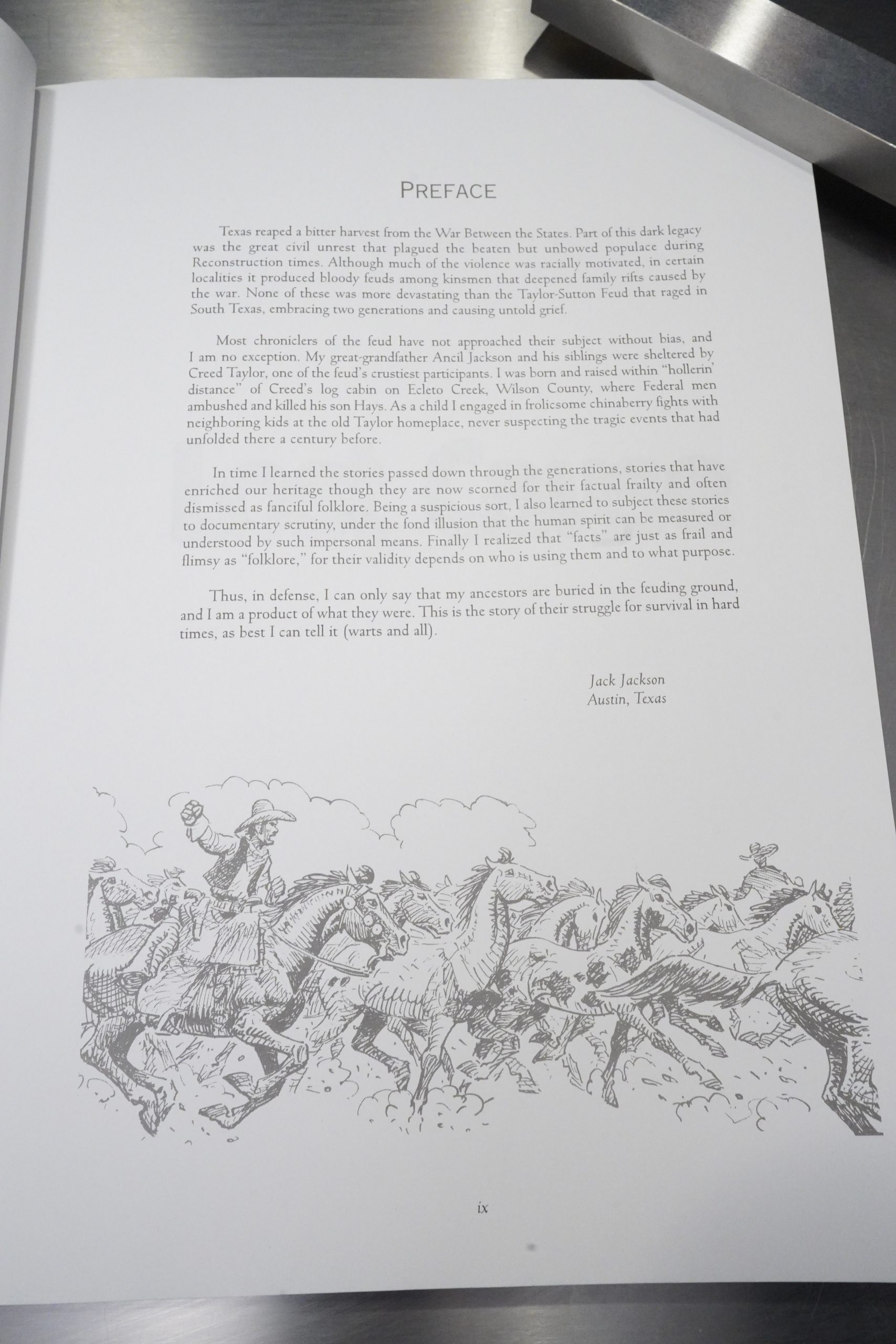

We start this book with an introduction where Jackson explains that this isn’t going to be an… objective… telling of this story.

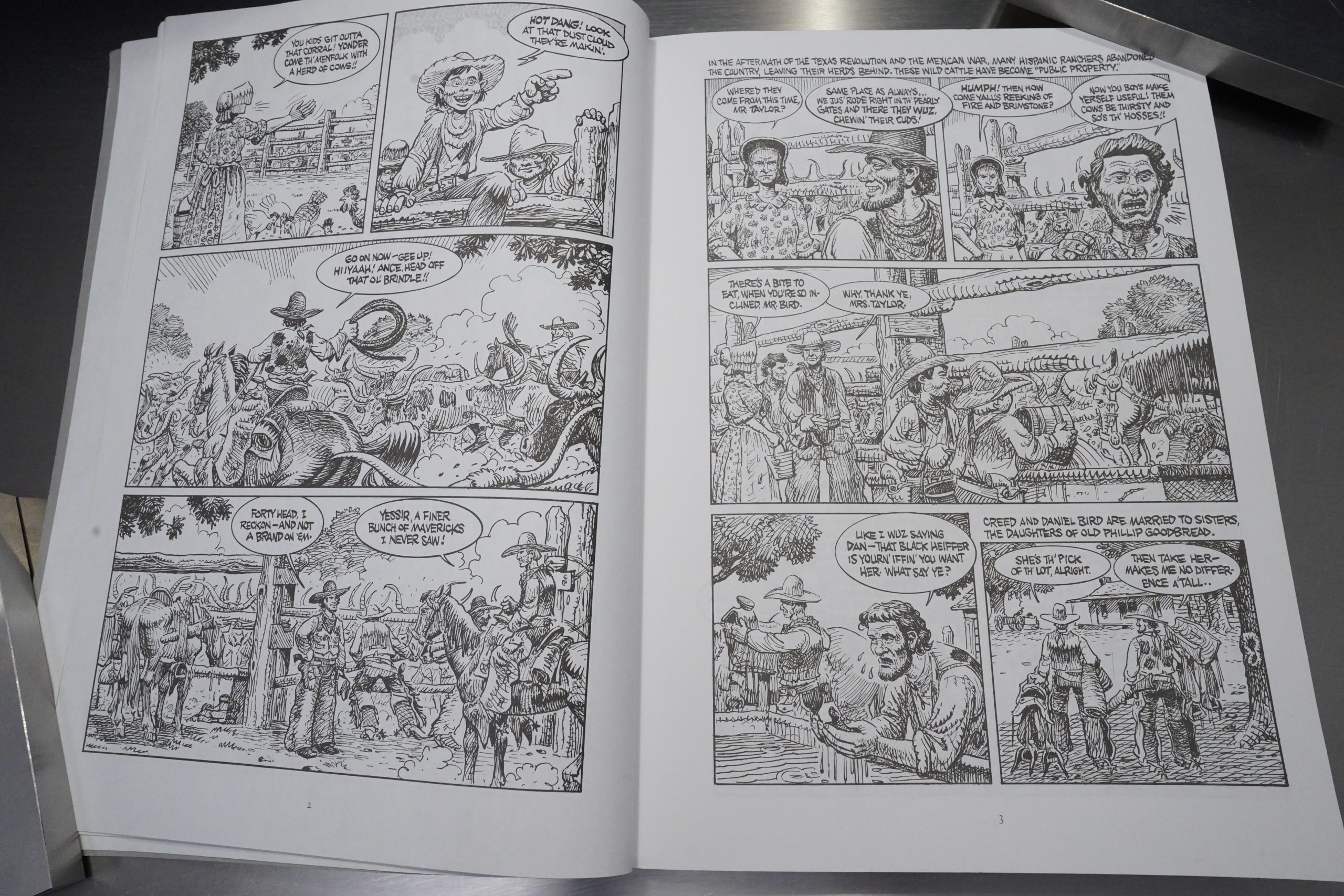

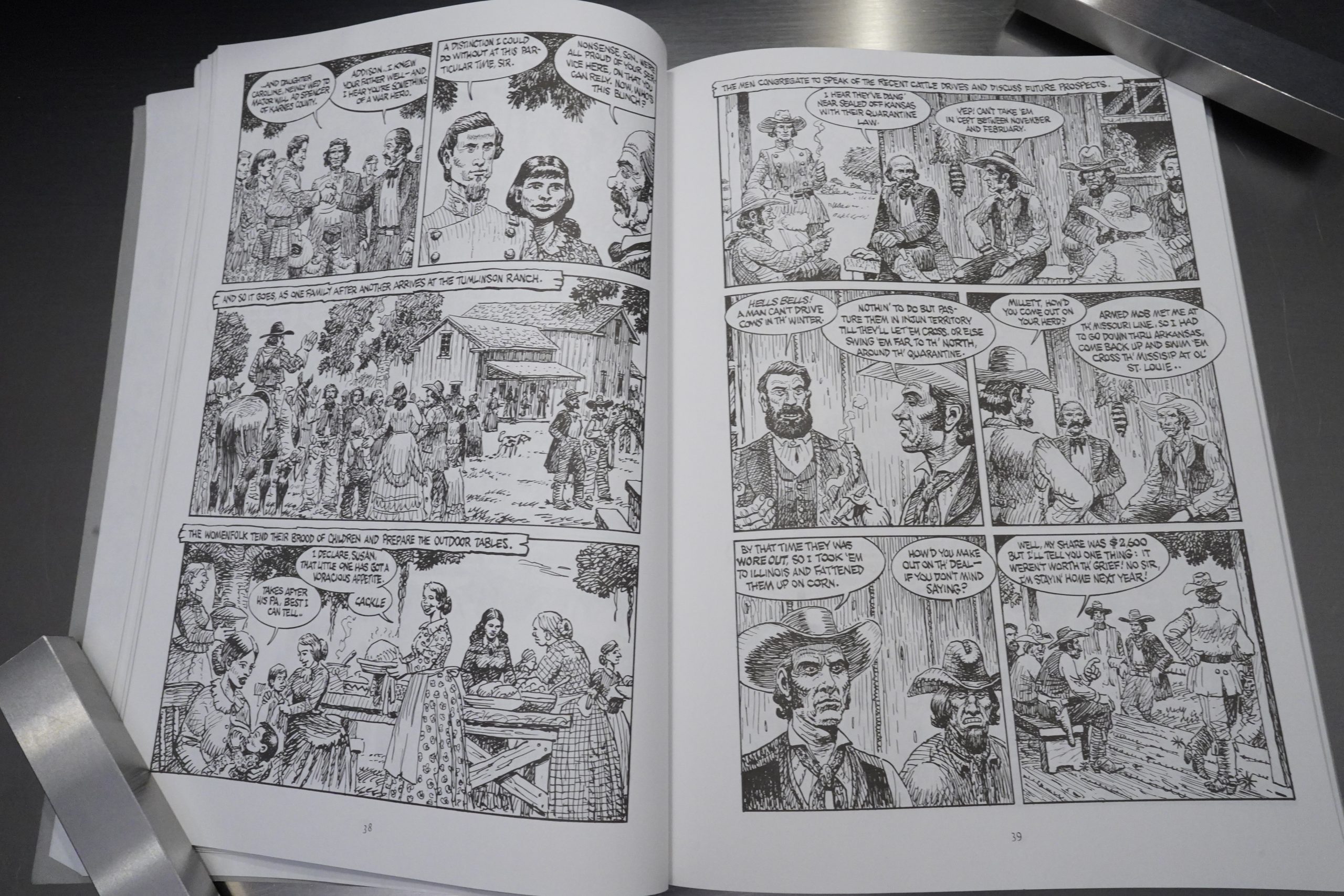

I think part of Jackson’s appeal to me is just how gnarly his drawing is. His figures are really stiff in an ECish way, while his rendering is down and dirty, and the juxtaposition just makes his pages look interesting. (I guess the rendering isn’t totally dissimilar to Jean Giraud’s western comics, especially his early 70s one, but I’m assuming neither was influenced by the other, but had a parallel take on drawing western stuff.)

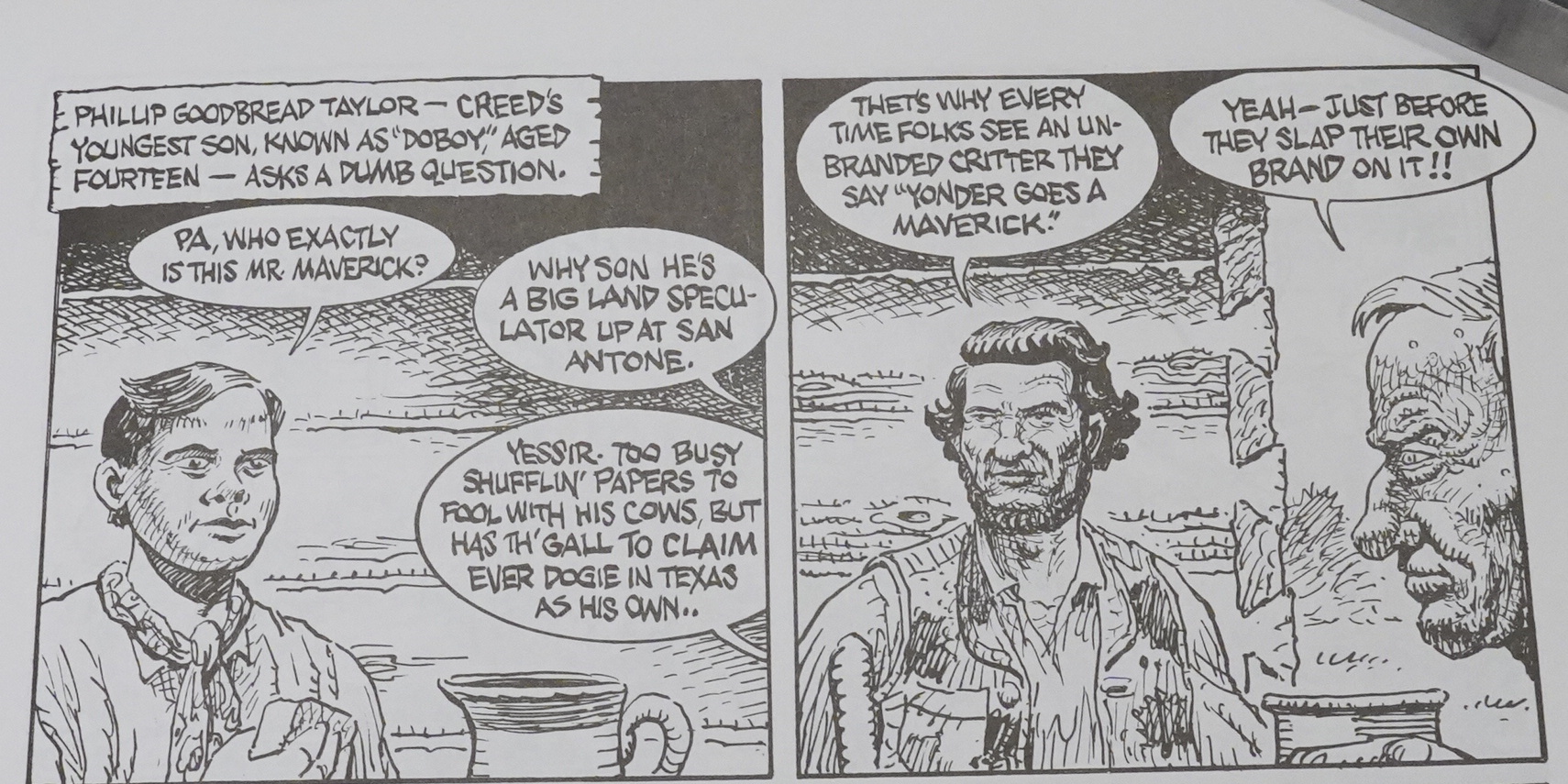

Oh, is that where the term “maverick” comes from? Jackson is, as ever, very edumacational.

The material here could be tough sledding — there’s so many names, factions and events that somebody like me (who has zero recall for names) could easily be totally confused all the time. But somehow it works. Jackson manages to imbue these people with at least some character to allow the reader to distinguish just who is killing who this time.

But there’s a lot of this recaps of current affairs, especially at the start of the book, and I can see how many people would just rather not.

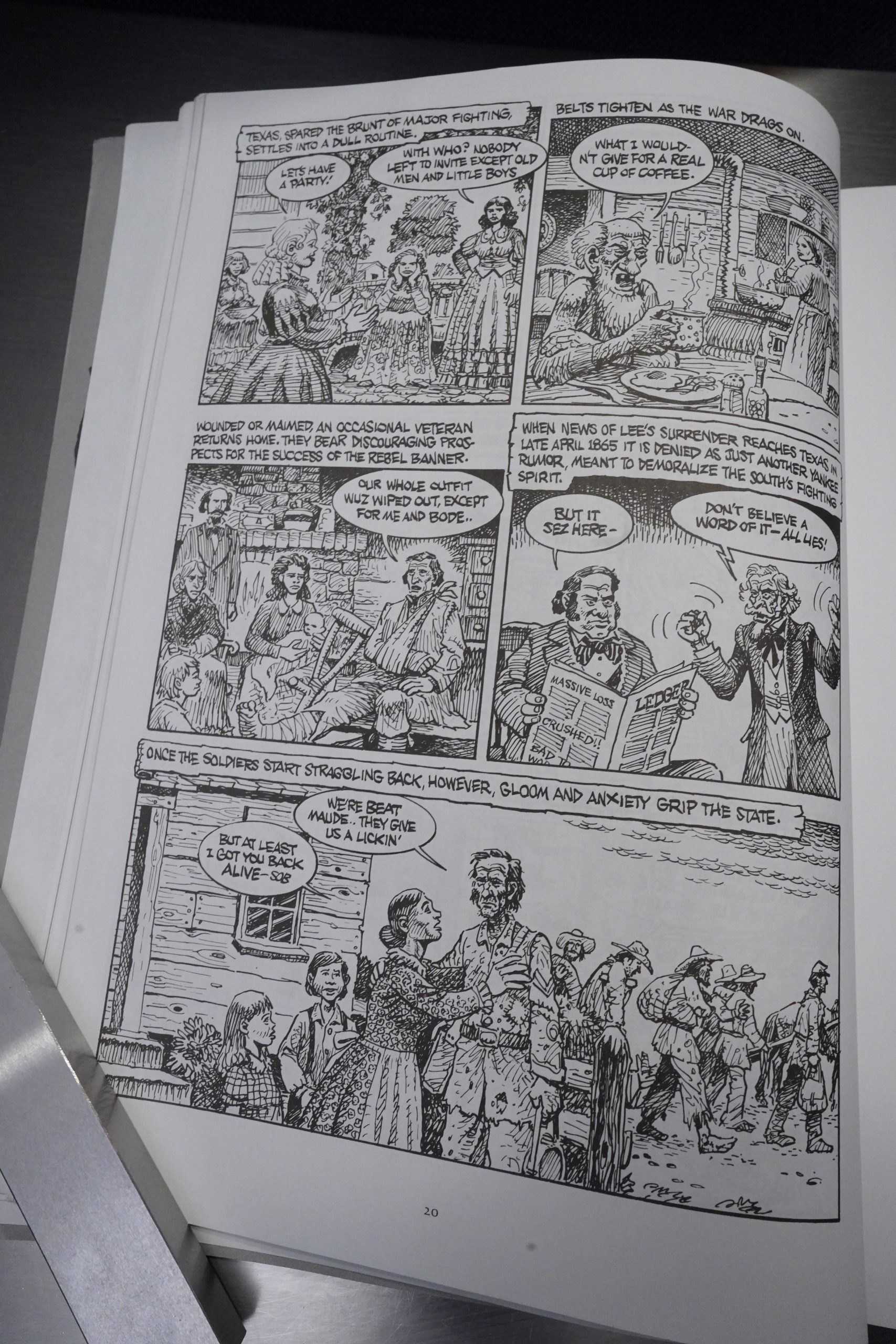

The US civil war takes place — and Jackson mercifully skips the entire thing. We only get the aftermath, which is a smart choice.

The aftermath told from the view of the white Texans that we’re following, that is.

Jackson wisely has many longer sequences in between all the infodumping where people can actually interact with each other; more like a traditional comic book and less like a lecture. Which, again, is a smart move, because it allows you to relax a bit before the next onslaught of names, names, names. (And also get to know the characters a bit.)

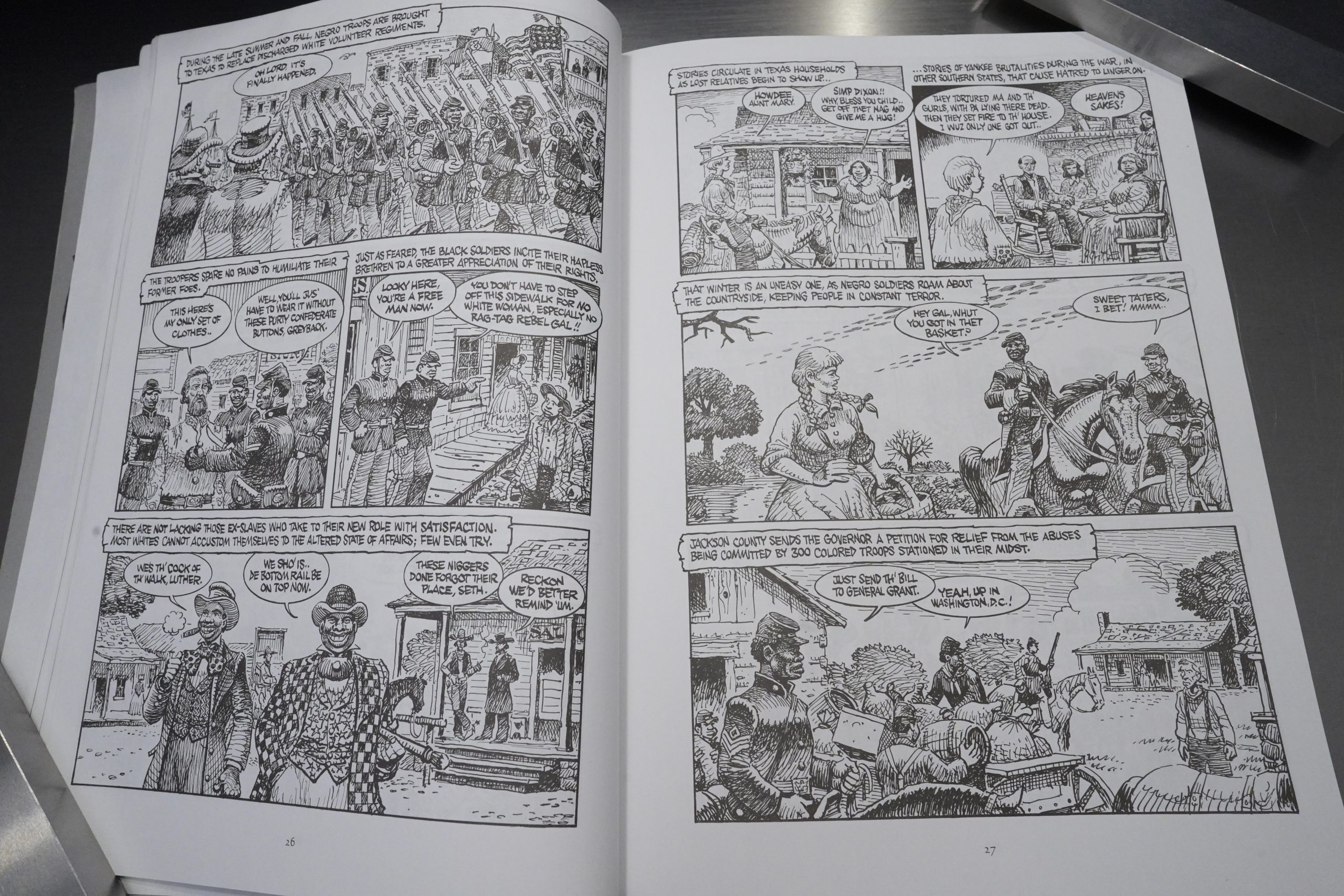

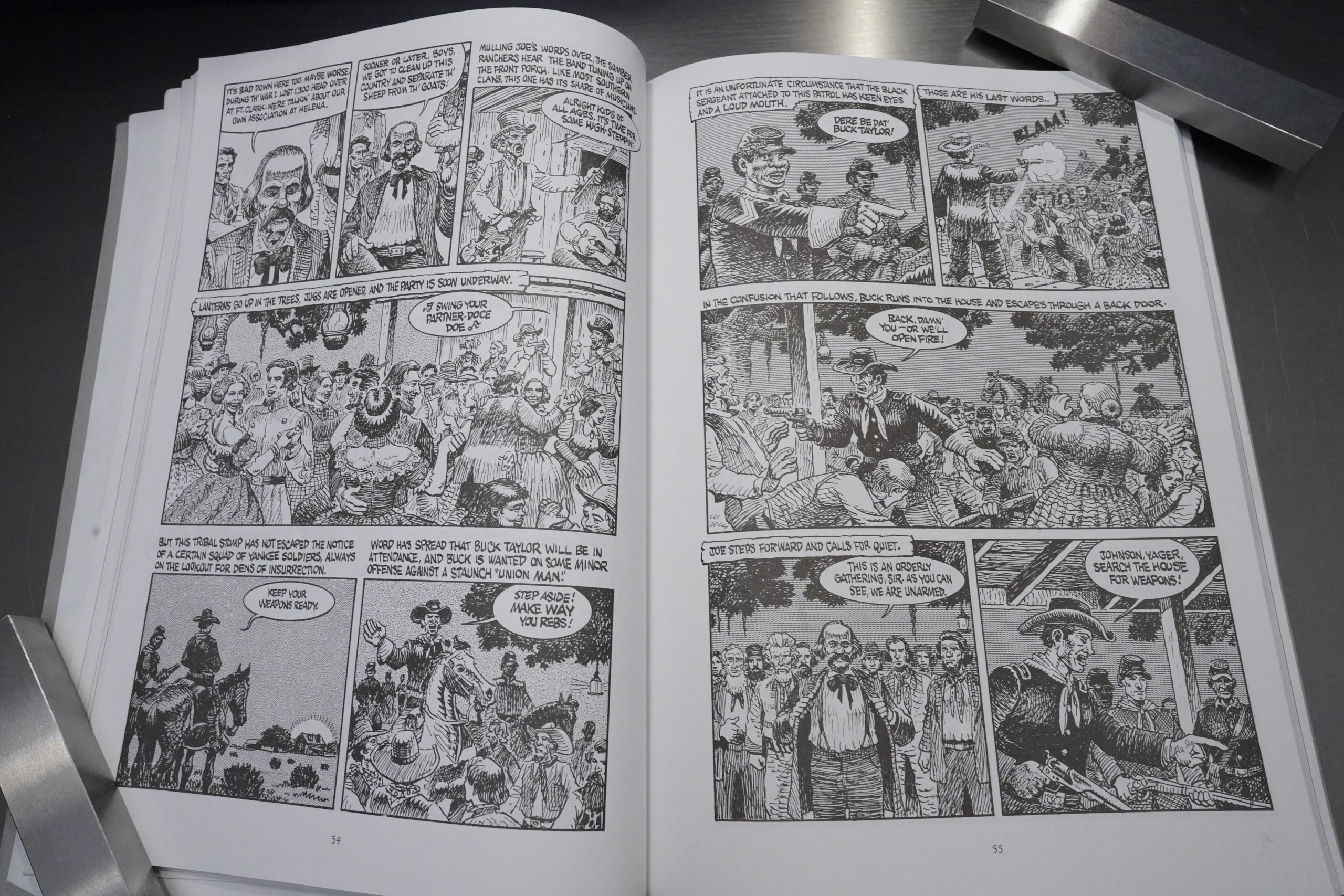

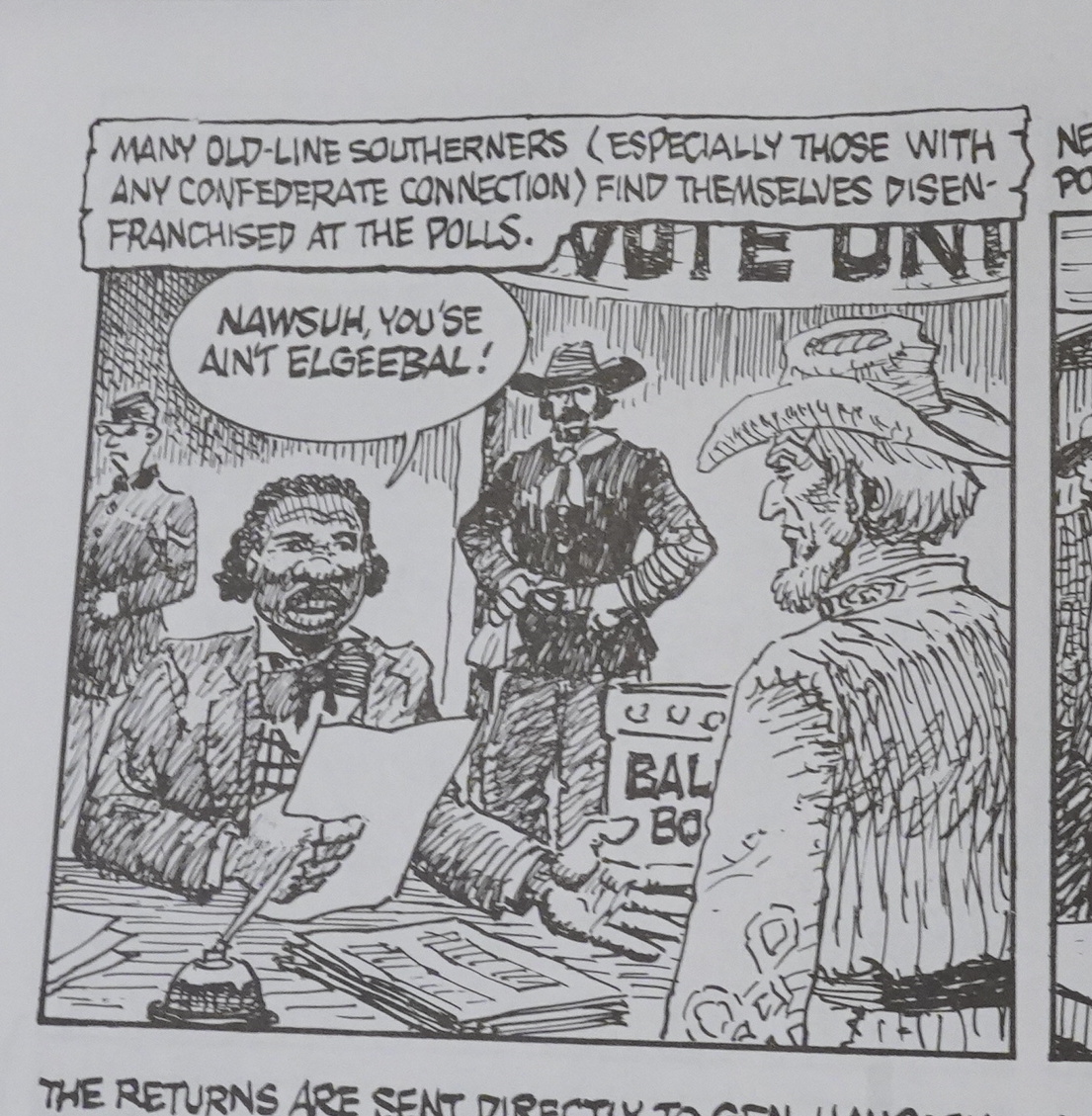

When Jackson said he wasn’t approaching this subject without bias, he wasn’t joking. How would you sum up these two pages, for instance? A reasonable summation would be “cops ride up to a party to arrest a guy wanted for murder, and that murderer kills one of the cops” would be a reasonable one, right? But that’s not how Jackson frames this. “It’s unfortunate” that the killed (Black) cop has “keen eyes and a loud mouth”.

Yeah, mm-hm, right.

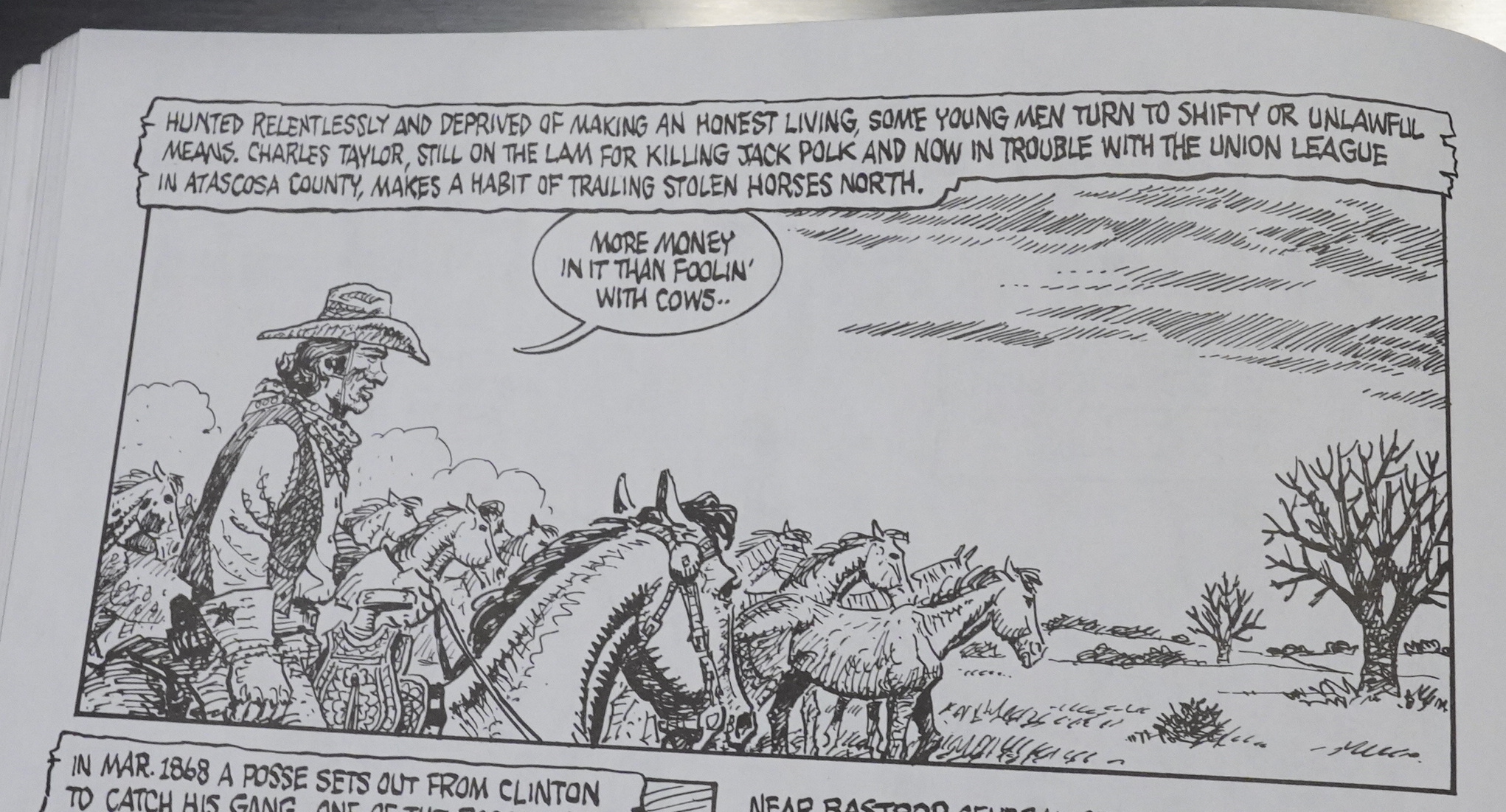

And what about this guy? Yes, Jackson says he’s a horse thief. But what about that framing?

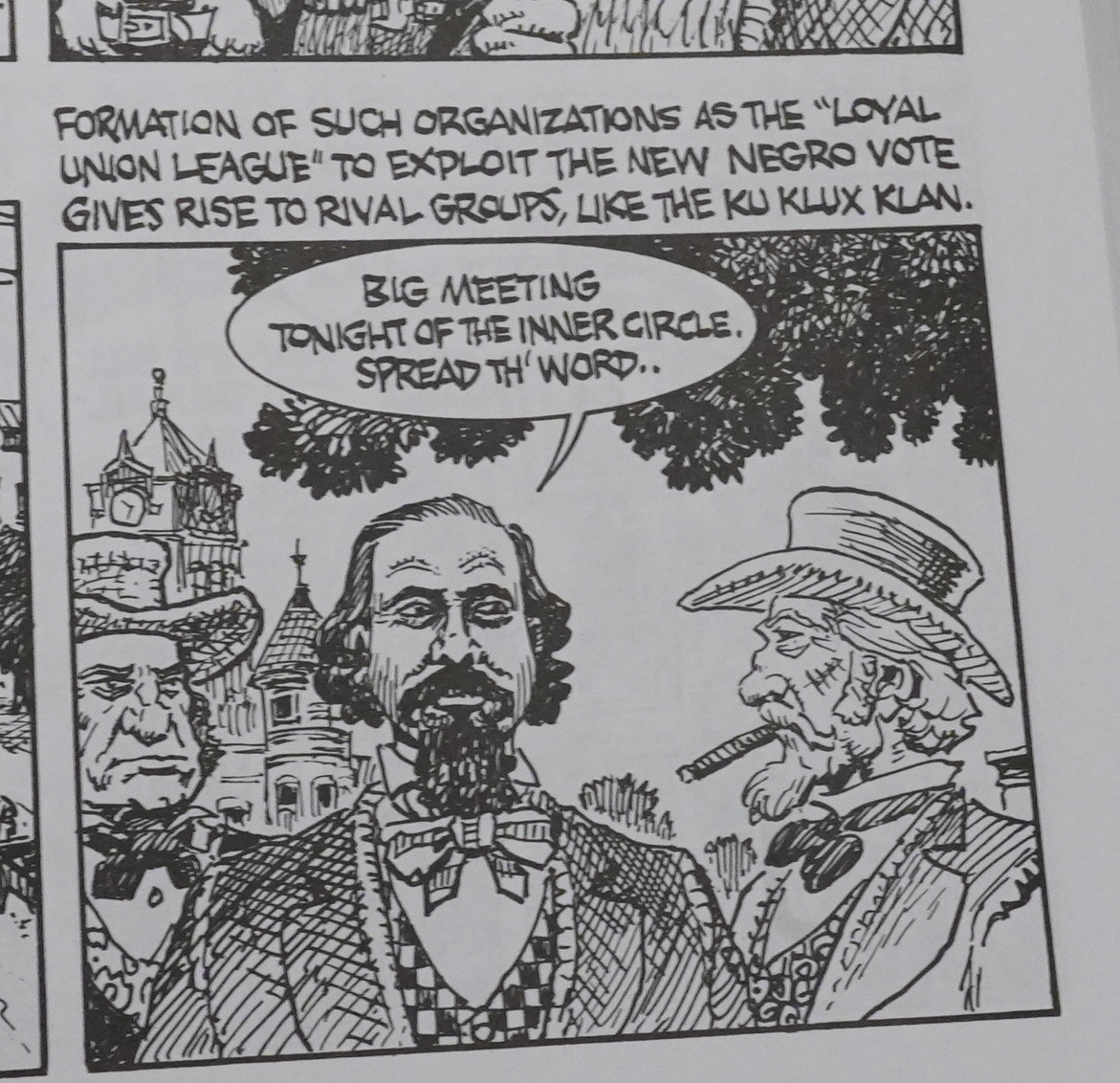

And why was the Ku Klux Klan started? Because of “rival groups” who presumably were really bad, right?

And while Jackson has many of the people speaking in broad dialect, he reserves the most illiterate talk to the few Black characters that appear.

What I’m saying is that this book is fucking racist.

Now, Jackson has previously done books seen from the point of view of Native Americans (Comanche Moon) and Mexicans (Los Tejanos), so perhaps he’s just hewing closely to the viewpoint of the fucking racist white Texans he’s depicting, but reading this book, it’s pretty relentless. Is there a single slightly sympathetic Black character in this book at all? Are there any murders or crimes done by the Taylors that Jackson doesn’t weasel word his way around? (I mean, he does show them killing a lot of people, so you might say that that’s him not trying to weasel out of anything, but it’s constantly done in a context that explains why they’re doing their murders.)

Right. But remember John Wesley Hardin, the man on the front of this book? He does show up here and there, but his part in this story doesn’t really start until the book is two thirds over. The book is mostly about how the Taylors are hunted (for very good reasons!) by a shifting state of law enforcement, and Hardin becomes involved with that.

But the cover isn’t a total lie: We do get a lot of Hardin stuff in the last third of the book.

Many of Jackson’s books veer towards incomprehensibility as they go along. That thing about the silver slug? Man. Jackson is on his best behaviour here, plot wise — it’s all structured well and keeps on being exciting (and readable) till the very end.

The Comics Journal #278, page 27:

Criticism was something to be expected

because history is open to interpretation and

people often have a vested interest in seeing

their version of the facts presented. Folks in

Texas take their history seriously, acknowl-

edged Jackson, but it was a personal attack

that gave him the most grief in 1998, when

he published his book Lost Cause, which de-

scribed the Reconstruction period in Texas

following the Civil War.

priest recounted, “When he started that

book, he said, ‘I’m going to catch hell for this

one.’ He said, ‘l ‘ve done the Indians and I’ve

done the Mexicans and I’m fixing to do the

white folks. It’s a time Of American history

that they just leave out Of the books, because

it was so damn ugly.’ He said, ‘I’m going to

try to give it as even a hand as I can. I’m going

to put all my sources and put all my footnotes

andjust hope for the best, because I got to do

it. The Story hasn’t been told.'”

The Austin Chronicle ran a review by Mi-

chael Ventura on Sept. 21, 1998, tearing Lost

Cause to shreds. The reviewer accused Jack-

son of racism in his treatment of blacks, and

trashed graphic novels as a serious literary

form. He even suggested Jackson’s weapons

were historically inaccurate. As damaging

as the false allegations was the subsequent

refusal of the editorial staff to allow Jackson

to publish a rebuttal of those charges in their

newspaper.

“That was idiotic on their part,” said

Priest. “He just didn’t know as much about

rifles as Jackson did. And the crap about a

graphic novel? They didn’t even know what

a graphic novel was. I think they were horri-

fied by the intensity Of the Story that he told.

I think they killed the messenger. think

they just couldn’t get over the impact of that

story.”

Fellow cartoonist Mack White offered

to help Jackson mount a defense. “He felt

grievously betrayed by the ChronicVs staff,

whom he had thought were his friends. The

day after the review appeared, Jack called

me. He was beside himself with anger. He

was considering legal action, at the very least.

If it had been an earlier era in Texas, I think

Jack would have strapped on his six-guns,

marched down to the Chronicle’s office, and

called out both the editor and reviewer to

receive a powerful dose of frontier justice.

He was that mad. I suggested an alternative.

Publish your rebuttal on the Internet. Jack

didn’t have Internet access at that time, so

he gave me the 10 or so handwritten pages,

which I typed and posted On the old ‘co-

mix@’ e-mail discussion list. This brought

the matter to the attention of the larger com-

ics community outside Texas, causing a great

many people to inundate the Chronicle with

letters defendingJack.”

The Comics Journal further defended him

by publishing an interview on the subject in

issue #213 in July of 1999, where he stated his

case to publisher Gary Groth. “When you do

a book, you have to take a perspective, 0K?

My perspective in this case was from the side

of the white Southerners during the Recon-

struction period. Basically, I saw the book,

because it is about a feud, as dealing with

white-on-white violence, none Of which Ven-

tura even mentioned in the review. He only

saw the white-on-black aspect of it, which in

fact is a very minor part of the book. I am not

trying to tell the story of John Wesley Har-

din from the black point of view. And I’m

not even interested in what happened to the

blacks except insofar as it was a contribut-

ing factor to the overall violence of the era in

terms of military rule and Reconstruction. So

I am takingprobably the most unpopularper-

spective for the book imaginable. And that is

the politically incorrect idea that you can tell

a story about racists sympathetically. You see

what I’m saying? Because they were racists,

as Ventura points out, but they were also hu-

man beings. In other words, racism was just

part of the mind-set of that day and time. So it

just seems mind-boggling to me thatyou can-

not take any perspective you deem appropri-

ate in the story you’re telling. I think that an

artist should have that latitude, in terms of

putting together his story, and deciding on a

perspective that is key to all that follows. And

I say, hey, I’m not telling this story like Alex

Haley would tell it I understand and appre-

ciate his approach, but it’s not my cup of tea.

Roots come in different colors. Now, is it ‘in-

trinsically morally questionable’ to attempt

a story from the oppressor’s perspective? I

don’t know. People are just people, and few

are perfect. Yes, white Texans of Reconstruc-

tion times were racists (as we now define the

term), but they also had the same hopes and

dreams of any era. Their lives had some re-

deeming qualities, and I don’t think it’s right

to sweep them into the historical dustbin be-

cause they did politically incorrect things by

current moral standards.

Jackson’s ultimate response to these

scurrilous charges resulted in a privately

published book calledJackson•s Rant, which

included his thoughts and copies of letters

from his supporters. Only 20 or so copies

were distributed to close friends.

It is indeed a pretty harsh review:

Jackson is a racist because he finds these qualities only in white people. Almost without exception, he presents blacks as oafs — exactly as blacks were presented in the old-timey movies that are the model for his dialogue. Amazingly, nearly every drawing of a black man is the same drawing. Same bone structure, same expression, same lips. His whites, by contrast, are differentiated. This is more than a simple gaffe. This is how Jackson sees. It’s also a necessary function of his storytelling — for if he drew blacks as humanly as he drew whites, then the racism of the whites would be harder for the reader to take.

[…]

In this panel, there are two blacks in the foreground — both with the same generic face — at the voting table. The black election official tells the black voter, “Mark it rat der — then come back in an hour and do it again!” “Then I gets my bottle?” the voter asks. There’s nothing racist in writing dialogue in dialect, no matter what the politically correct crowd says. Both races speak in dialect in Jackson’s work, and it’s appropriate. Nor is there anything racist in documenting election fraud — he shows election fraud on the part of the whites too. But with the whites Jackson is careful to show that there were many who were against such fraud. Yet this is all we see of black attitudes toward voting. Jackson gives the clear impression that this is how blacks took to their new and long- delayed franchise. Which is a lie. There is massive documentation that most freed slaves were deeply serious about their freedom — many, so very many, died, murdered, as proof of their seriousness. To suggest otherwise, in a work touting itself as history, is disgusting.

Jackson is interviewed in The Comics Journal #213, page 85:

GARY GROTH: talk about Lost

Cause and the controversy aeated by the

review by Michael Ventura in the Austin

Chronicle.

JACK JACKSON: I was pretty upset

about it, and didn’t really have any way

to deal with it, except appeal to the

Chronicle to let me defend myself, which

they wouldn’t do. And that was even

more aggravating than the review itself.

GROTH: they wouldn’t give you the

same kind Of space that theygaye I found

to be pretty contemptible. Tie retietvran in

the Austin Chronicle on September 18,

1998. there any backlash towards you,

asfaras you could tell, after he called you and

your racist?

JACKSON: No. On the contrary, people

were nsing to my defense — calling me,

writing me, and trying to e-mail me—

but I’m not on the internet, so a friend

of mine who was passed these things

along. I was amazed at the issues that

were being discussed on these posts, you

know? They were going to the nitty-

gritty , and halfofthem hadn ‘t even read

the book yet. They werejust lookingat

the review itself, and the ignorance that

it manifested.

GROTH: so didn’t catch any moreJlak

because of the review?

JACKSON: Oh. absolutely not. No, it

very supportive, and that’s what

finally made me realize that hey, there’s

no point in trying to dodge this, you

might as well grab the bull by the horns,

you know? I don’t want to use the term

“milk it,” but controversy sells books.

So if this guy wants to label me a racist,

sure, let’s talk aboutit. Consequently, I

was going to book-signings and discuss-

ing the racial aspects of my book. For

example, the governor’s wife every year

throws a thing down at the state capitol

called the Texas Book Festival, and I was

an invited speaker on a panel on John

Wesley Hardin — and guess what came

up? The review. So I figure there’s black

people sitting in the audience, and you

just have to deal with it, once somebody

decides that your work is racist garbage.

That’ s basically what the guy was saying,

that bst Cause is gomg to pervert and

tw•ist the minds ofinnocent young chil-

dren, and he sees himself as their savior,

as it were, by denouncing my work. To

say it blind-sided me would be an un-

derstatement, because as you know, all

my previous work had done just the

opposite. It had tried to tell the story of

“the neglected historical others, ” as Rusty

Witek would call them. And simply

because I wanted to do a book and tell

the story from the perspective of the

be your social equals. So you had these

pockets of resistance, which I think is

natural in any similar situation. Even

worse here. And violence, of course,

was a necessary aspect of this transitional

period before the kinks were worked

out. Hell, they’re still not worked out.

But you can imagine in those days what

the situation was like. The difficulty

came mainly with the young men, the

young-bloods, those who weren’t old

enough to have taken part in the Civil

War. They had not experienced all of

the obscene things that go on during

war. They’re sitting around listening to

their older brothers, cousins, and uncles

talk about them, and they kind Of saw

themselves as the champions of this life

style which all of a sudden is gone.[…]

JACKSON: Well, the guy needs glasses

very badly, and several of the people

whose letters the Chmnide did publish

pointed this out, that there is as much

differentiation in the black people in the

book — because I’m working from

photographs, forheaven’s sake—as there

is with white people. But the reviewer

evidently did not notice these. He

thinks that because my blacks have flat-

ter noses and larger lips than my whites,

that these anatomical differences are

somehow an insidious plot on my part

to dehumanize thesepeople. Gary, he’s

saying that I’m operating on exactly the

same level as the Nazi artists in Ger-

many.

GROTH: Right, nght.

JACKSON: Those artists/cartoonists Who

depicted the Jews as squat. fat, little

hooked-nose subhumans to prepare the

German population for the idea that

they should be exterminated. He’s say-

ing that I’m doing the same thing, and

that by depicting my blacks in this fash-

ion, I make the white violence against

them more acceptable. Hey, man, that’s

a heavy charge. And it is notjustified by

the artwork. Ifyou look at it, you will

see these people come in differentshapes

and flavors like the white folks.

GROTH: I didn’t detect that the blacks u,ere

any more caricatured Within your style than

the udlites.

JACKSON: This is what is happening:

I’ve never seen a single bit of art-work

that Michael Ventura’s ever produced,

yet he claims to be an artist in his review,

and he is not even perceptive enough to

note the differences in the people that

I’m drawing. And I wasjust floored by

that and many of his other accusations.

I’m not an ignoramus. This was not

kind ofa happy-go-lucky, “Let’s try to

draw these subhuman Negroes so that

everybody will think that they got what

Was coming to them,” sort of thing.

Ventura’s write-up was just a litany of

putdowns — everybody who read it

said that it was the most bitterkind Ofso-

called review they had ever read in their

life and that it really amounted to a

personal attack, a smear. I certainly wasn’t

prepared for it. So like I said, it put me

in a state ofmind where for like a couple

of weeks, I didn’t even want to do

anything, you know? Why bother? If

this is the kind of response that you get

to something that you slaved on for a

couple Of years… It really did take the

wind out ofmy sails, Imustsay. Andhe

later defended himself, because evidently

he had been getting a lot of letters and

feedback from people himself.

GROTH: where did he defend himself

JACKSON: He has a weekly column

called “After 3 AM,” or “Midnight

Hour,” or something like that. I don’t

know ifhe lives here in Austin or in L.A.

I know that he bounced back and forth

for a while, trying to become a screen-

writer out there, and had no luck at it.

One Ofhis projects, as it turns out, was

a screenplay dealing with John Wesley

Hardin, which nobody wanted. I think

that when he saw my book, a lot of

something — antagonism — came into

play. Ijustdon’tknow. I’venevermet

the gentleman, who, I understand, hails

from the Bronx.

Well, that explains … er… it. So basically, there was one negative review of the book (which basically had the same response I had, apparently), and then everybody went apeshit trying to defend Jackson, sending letters to the newspaper etc.

The Comics Journal #213, page 89:

So to me there’s no “moral con-

flict” in humanizing your subjects, be

they scumbags or saints, and I don’t

think the goals of art are incompatible

with such an approach. Ifthe story has a

compelling ring of truth, it’s art, and

political correctness can take the hind-

most.

GROTH• Note, have been criticized, in

Lost Cause, being a bit all over the map,

because it’s not only about John Wesley

Hardin, it’s also about the Taylor-Sutton

Feud, and there’s less one central character in

this book ‘Iran there is in say, Los Tejanos.

about.

Did you feel that scattered?

JACKSON: No, not really. Part ofthe

problem comes from the fact that the

editor there at Kitchen Sink wanted to

use a different subtitle on the cover.

Something about “the story of famous

gunfighter John Wesley Hardin”. Soa

lot Of people saw that and bought the

thing thinking that they were getting a

full-fledged book about the life of John

Wesley Hardin. Actually, I’m not inter-

ested in him except in terms ofthis feud

that I’m writing about, and the era itself.

So I think some people were disap-

pointed, because the “main character”

doesn’t show up until deep into the

book. But ifyou look on the title page

itself, you will see what the book is really

about.

GROTH: I noticed that.

JACKSON: That’s misleading hype, but

I don’t feel like I should be blamed for

that. I understand that when a publish-

ing company does a book, they want to

market it on the basis ofname recogni-

tion, via the Bob Dylan song, and the

Time-Life blurb about him being so

mean that he shot a man for snoring,

blah blah blah. True. the book has sort

ofa “castofthousands.” And I guess that

that’s discombobulating, if you’re ex-

pecting a very focused story told just

from one individual’s experiences

throughout. But I didn’t really see any

other way I could deal with it, because

this one person is not there all the time.

Well, that’s chutzpah for you.

Ron Evry writes in The Comics Journal #213, page 91:

This is part and parcel what the Texas

revolutionaries were after: the right to

grab whatever they could from what

they perceived to be a vast, free-for-all

country. While not outwardly men-

tioned in the comic, the breed of men

that Jackson writes about didn’t have

noble motives to create a democracy in

Texas, but were empire builders (of

course, this did not stop the Texans

from adopting the outward pretentions

of democracy, and Jaxon often depicts

citizens dressed in formal clothing and

making public speeches). Much is made

in the beginning of the book about

ranchers and cowboys fighting and kill-

ing each other for the right to take

unbranded (and sometimes branded)

cattle roaming freely on the range, The

cowboysjoked about rounding up ” Mr.

Maverick’s” cattle (a reference to the

businessman who claimed all the mil-

lions of free cows in the state from an

office somewhere), providing a popular

nickname for the animals. While not

mentioned in Imt Cause, actually, Mr.

Maverick himself was a hero of the

Texas revolution, trying to claim what

he could as well as the others.

Jackson’s depiction of thß atmo-

sphere of naked grabbing for anything

that Texas had to offer reveals a series of

events that led to massive splis and

creation of hostile factions. Business-

men in the cities, desperate to have their

goods shipped out from within the state

hired cowboys and ranchers to protect

the low paid Mexican caravan drivers

from attacks by Anglos. Awash

with the power of vigilantism, these

“protectors” took it on theirselves to

fight “lawlessness” by lynching and at-

tacking competitors on the range who

they find rounding up unbrandedsteers.

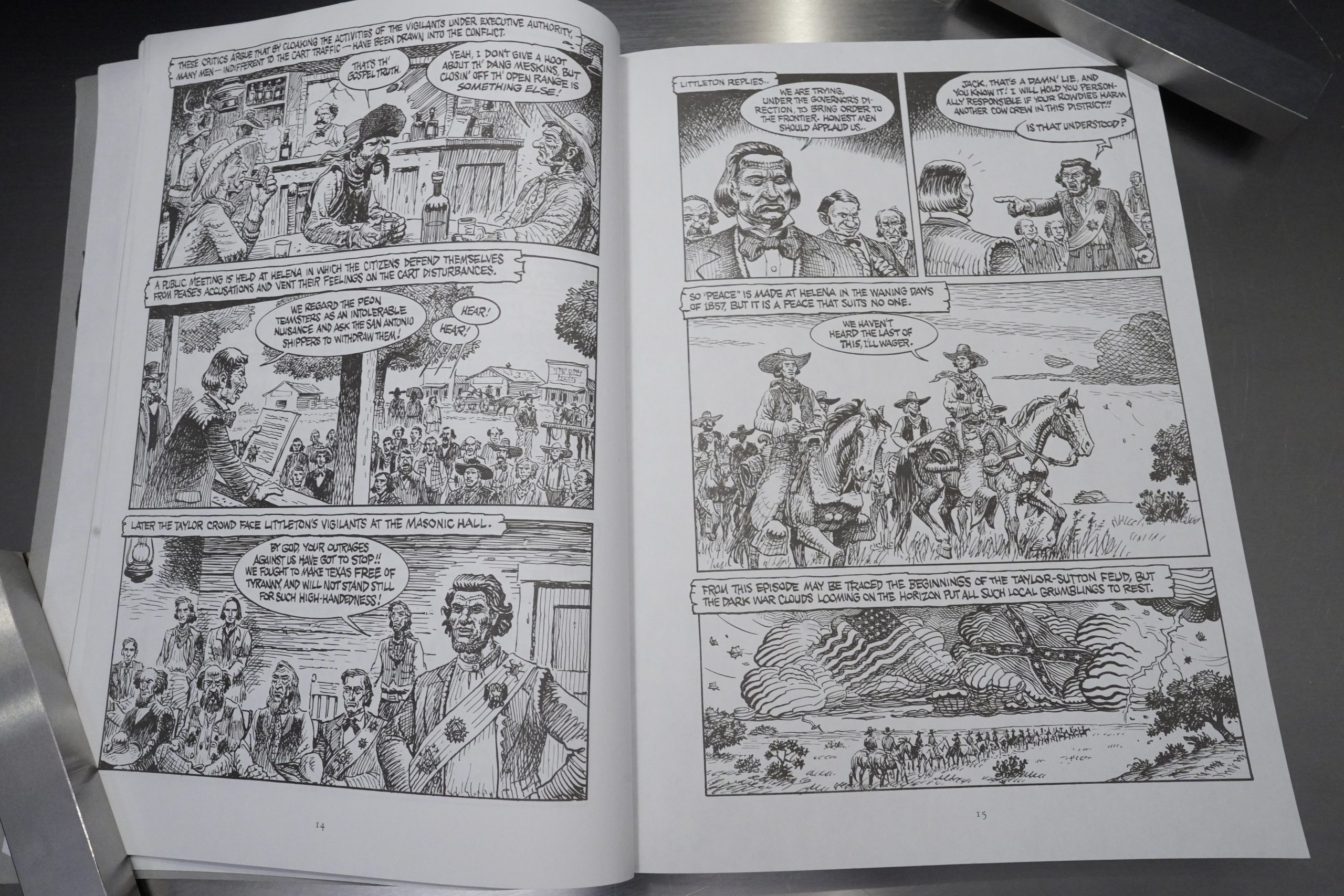

Jaxon often depicts these vicious com-

peting groups as being on first name

familiarity with each other. The draw-

ing of one of the first dividing lines

between the Taylorled ranchers and the

Litdeton vigilants is shown at a summit

meeting held at a Masonic Lodge. The

participants are dressed in their Sunday

best clothing wearing their Masonic

sashes, even while threatening each other

with primitive brutality.[…]

Throughout the remainder of Lost

Cause, the factions become even more

complicated and the string ofshootings,

hangings, and vengeance killings runs

rampant. Eventually, a young Billy

Sutton kills one of the Taylors and

becomes a leader in the faction. His

name has become attached to the feud of

the years, as his side became known as

the Sutton Party, but even after his

death, the feud lingered on. The Taylor

side included Wes Hardin, the infamous

outlaw who may have killed more men

than anyone else in the west, although

Jackson’s comic tries to put at least a

slight justification on many of his kill-

ings. Throughout the second halfofthe

book, much ofthe action is centered on

Hardin, and in contrast to the talky

events of the early chapters, Jackson

includes plenty of action and bloody

encounters.[…]

Jackson’s work is a testimony to the

power of the comic book to graphically

depict a truly long and complex story

with a depth that is unavailable to film-

makers and a visual flair that is utterly

impossible for the written word to

achieve. The plot of Lost Cause is so

complicated that numerous rereadings

are truly necessary to understand it. I not

only got a lot ofhistory out ofthis book,

but I also found myselffrequently exam-

ining the events of the party at Joe

Tumlinson’sfor entertainment. Thispar-

ticular chapter stands as one of the best

examples ofthe comic artist’s skill, and

could stand on its own.

Michael Hureaux Perez writes in The Comics Journal #215, page 6:

It seems to me that the brunt of the flack Jack

Jackson has caught for the work Lost Cause is the

usual crap that goes flying whenever any his-

torical portrait is attempted in our culture. It’s a

tough gig, and harder still if one should choose

the subject of post-war Reconstruction in the

South. I applaud Gary Groth’s decision to offer

Jackson a forum to defend the artistic choices he

has made.

But at the risk of being called “politically

correct” by Jack Jackson, it should be noted that

most popular histories of post-war South and

Reconstruction that were circulated in this coun-

try up until twenty years ago chose to focus on

the excesses of federal troops during the federal

occupation. I haven’t studied Reconstruction in

East Texas as well as Jackson has. But in all truth,

I don’t think he should be surprised at all by this

hornet’s nest that has arisen. I don’t trust

Ventura’s crusade, but I don’t think a certain

wariness of representation of black experience

by white artists in inappropriate. For, as W.E.B.

DuBois observed in his criticism of most white

memoirs of the era in his work Black Reconstruc-

tion:

Suppose the slaves of 1860 had been white folk.

Stevens would have been a great statesman, Sumner

a great democrat, and Schurz a keen prophet, in a

mighty revolution of rising humanity. Ignorance

and poverty easily would have been explained by

history, and the demand for land and the franchise

would have been justified as the right of natural

freemen.

Or, the excesses of time would have been

overlooked by historians in that epoch. I think

it’s interesting that white southerners were so

traumatized by an era relatively brief compared

to 15 generations of chattel slavery. Perhaps the

state didn’t “have the right to force people to live

or think differently than they had in the past,” as

Jackson put it in his interview. But I think it

would have been asking a lot of black troops

who were affected by slavery to have responded

any differently than some may have in the years

following the civil war. After all, what was

slavery, if not a displacement of people from

everything they had know in in the past? And

even Lincoln, conciliator that he was, noted in

his second inaugural address that he wanted the

war to end quickly, but if it was willed by

“providence” that it go on until every drop of

blood drawn with the lash was paid with an-

other drawn with the sword, so be it. This is not

to imply that the historic victor was always

correct justbecause they won, but merely to say

that the experience of slavery was an abomina-

tion, and like most savagery, sent weird off-

shoots out of the ground.

I haven’t seen the work yet myself, but I have

to admit that the effort Jackson has apparently

made to put black dialect on the page set my

teeth on edge when I saw the selected pages in

the Journal. That’s not what we sound like to me,

and I’ve known a lot of southern black folks

from East Texas. White artists who want to

attempt this need to tread that kind of ground

gently, or get a damn hearing aid, or something.

All in all, though, it’s bloody important for

artists to attempt to explore what happened to

the dispossessed white in the South. Charles

Frazier has provided us with one very fine ex-

ample of how this can be done with an artistic

subtlety that honors the complexity of human

beings in his novel Cold Mountain. It looks as

though Jack Jackson has attempted an equally

ambitious project within his own discipline with

this graphic novel Lost Cause, and here’s hoping

that the flame surrounding the “delicacy of writ-

ing politically charged drama,” as Groth puts it,

won’t singe his butt feathers too badly. I’m

looing forward to seeing the entire work.

The book was re-published along with Los Tejanos:

However, especially with Lost Cause, Jackson’s concern with presenting every facet leads to him being unable to convey the essence. With the net spread so wide encompassing so many minor players, readers will have difficulty remembering who people are and their earlier relevance.

Which was a smart thing to do.

Bob Levin has a thoughtful review, as always:

When “Lost Cause” first appeared, a reviewer in “The Austin Chronicle,” an independent newspaper, attacked it as racist. Jackson defended himself in a lengthy interview in “The Comics Journal,” conducted by Gary Groth in 1998, which is included in this volume. (The review is not.) Jackson explained he had written the book from the perspective of Reconstruction era Southerners, an “oppressed” and “subjected people.” His position was that he could portray racists sympathetically … (because) racism was just part of the day” and they “had the same hopes and dreams… (as anyone) of any era.” His mission, he told Groth, was to “take people back in a time machine… and let them see events as they occurred through these people’s eyes.” (Emphasis in original.)

[…]

Even when he was speaking with Groth, Jackson seems somewhat tone-deaf, foggy-visioned, and disingenuous. The fact is, he did not create either of his books, strictly speaking, from the point-of-view or in the voice of a 19th century Texan. Both presented as the work of a 20th century historian, which would seem to require an objectivity and balance, no matter how partial he was to one side or another, that is not always present.

Hey, this is a really good review. In that, I mean that Levin agrees with me!

Then there is Jackson’s ear. His reproduction of Afro-American speech is so replete with “massa,” “dawg,” “we’s,” “sho is” “suh,” and “dere be dat,” he might have been writing dialogue for a minstrel show. Maybe the people he portrayed did speak like this, but Jackson’s whites, no matter how ill-educated, consistently speak with better syntax and grammar. They never swear. They do not even have a Southern drawl. So he can not convincingly claim he was simply reproducing speech. He was characterizing in a prejudice-inflaming fashion.

Go read that one instead of this one.

This is the two hundred and nineteenth post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.