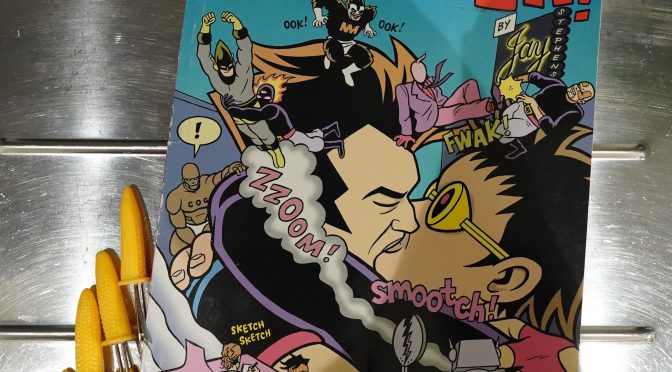

Go Power!: The Complete Atomic City Tales Collection (1997) #1 by Jay Stephens

As far as I can tell, this is the last thing that the (post-)Ocean Group iteration of Kitchen Sink published before (almost) going under, and then being bought by a new investor. So I’m going to cover more of that at the end of this blog post, but let’s read the book first.

From the title, I had assumed that this would be a, well, complete collection of all the Atomic City Tales stuff (including the three issues that Kitchen Sink had published), but I missed the “vol 1”, I guess, and Atomic City Tales wasn’t officially dead yet. (Reading interviews with Stephens, he seemed rather burned out on the concept, so I was thinking that he’d decided to cancel it already.)

Bu I think Oni Press printed the entire series in two volumes, judging by the titles of the collections alone.

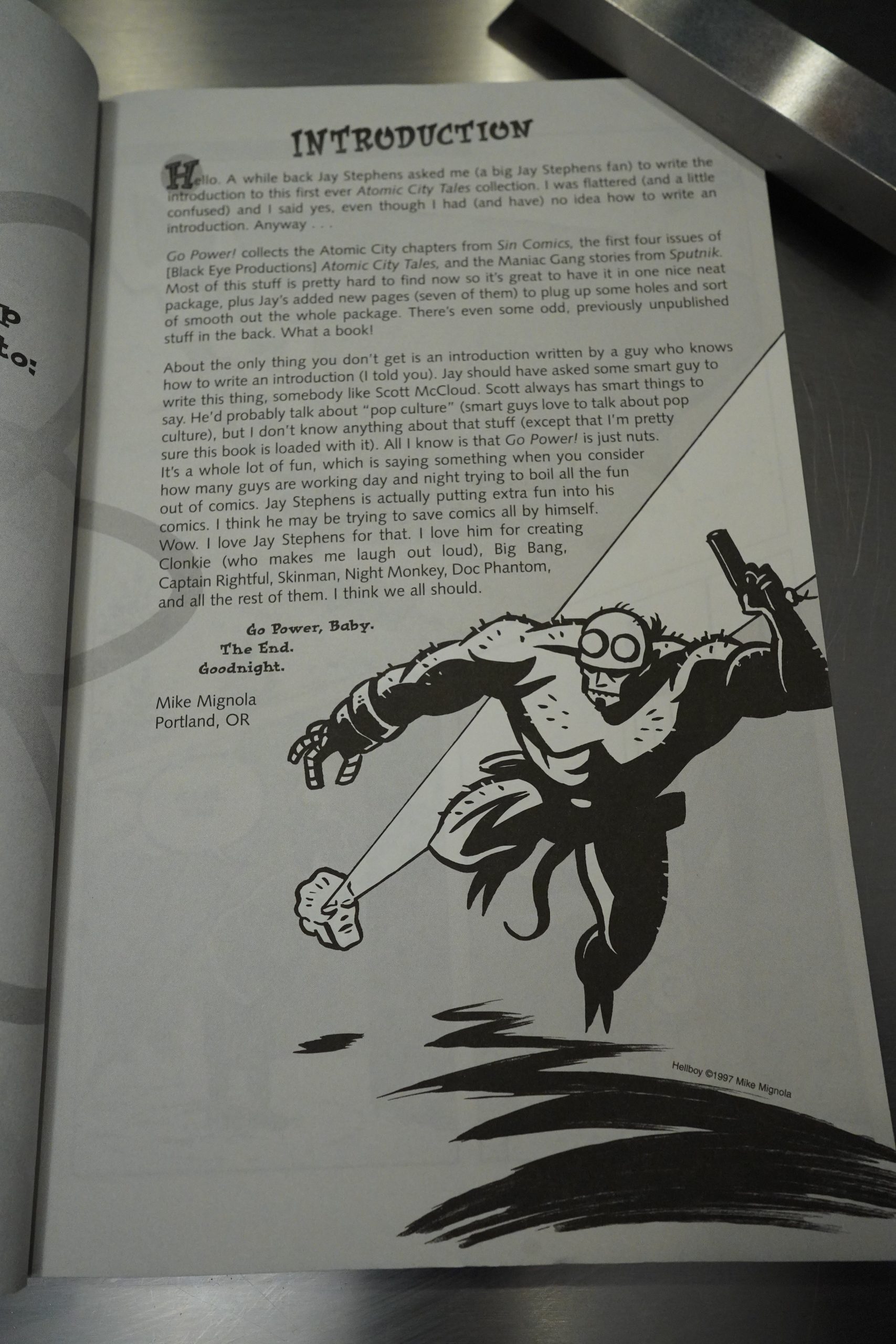

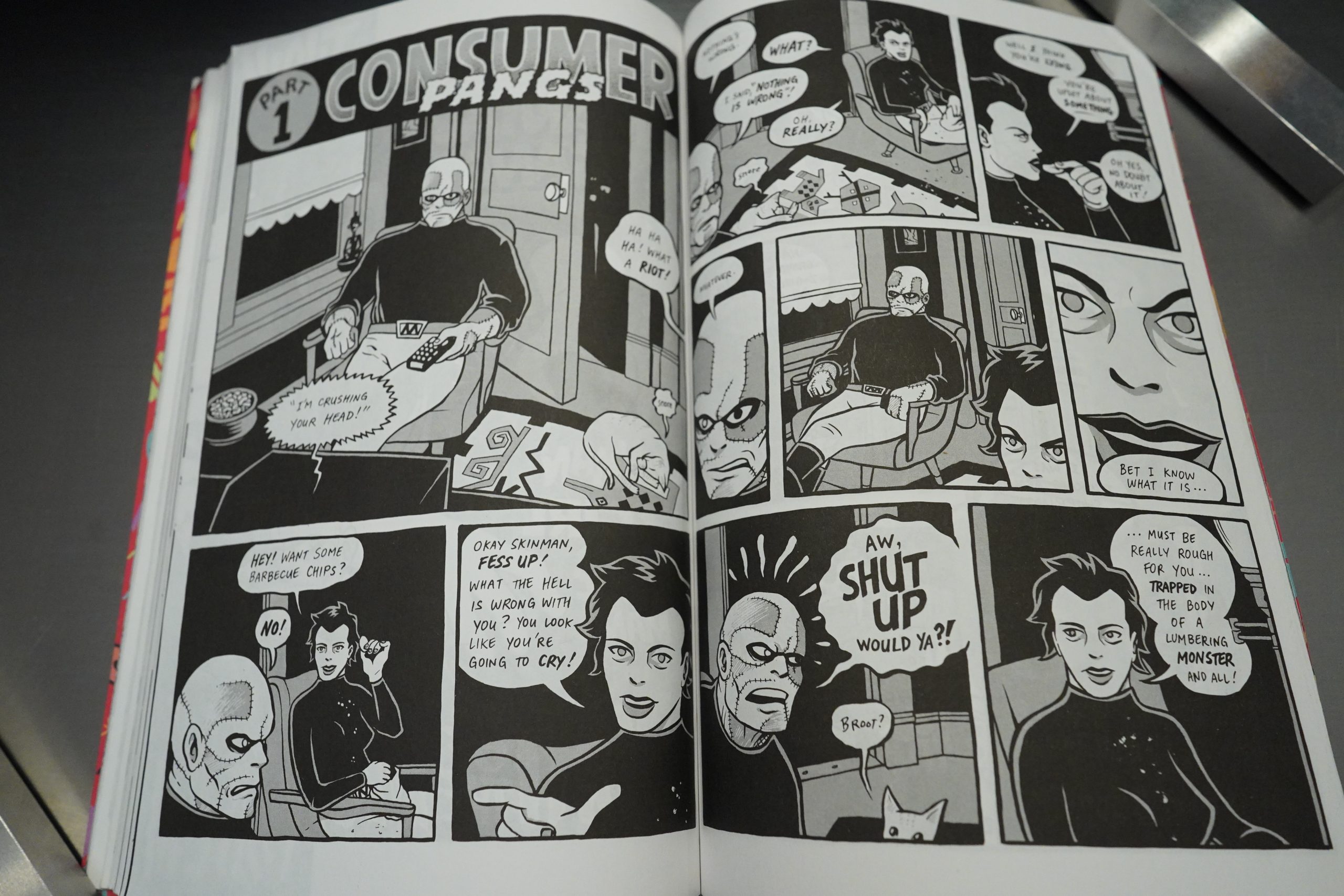

So: This collection collects all the old stuff (published by Black Eye, mostly), and adds stuff like this framing story.

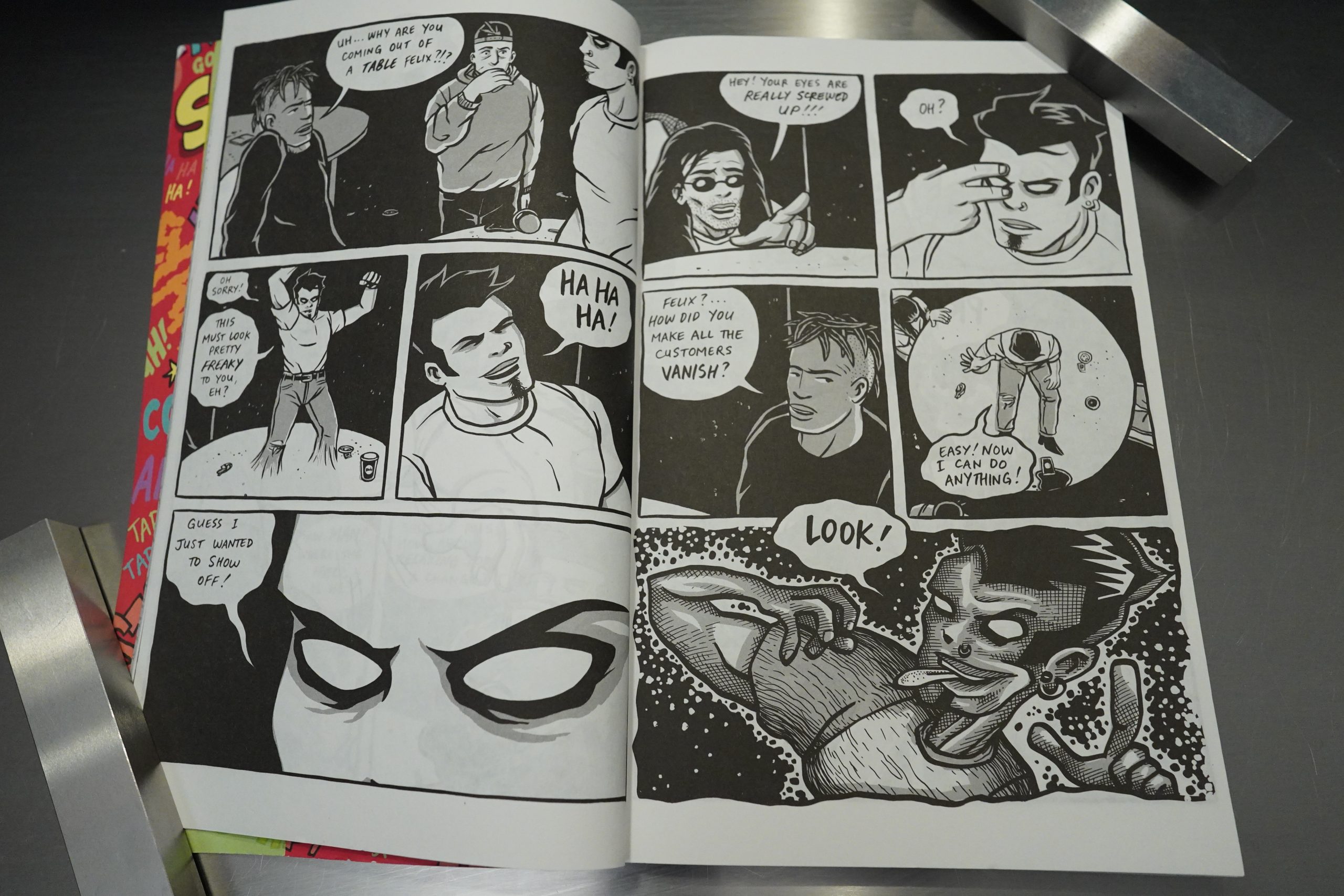

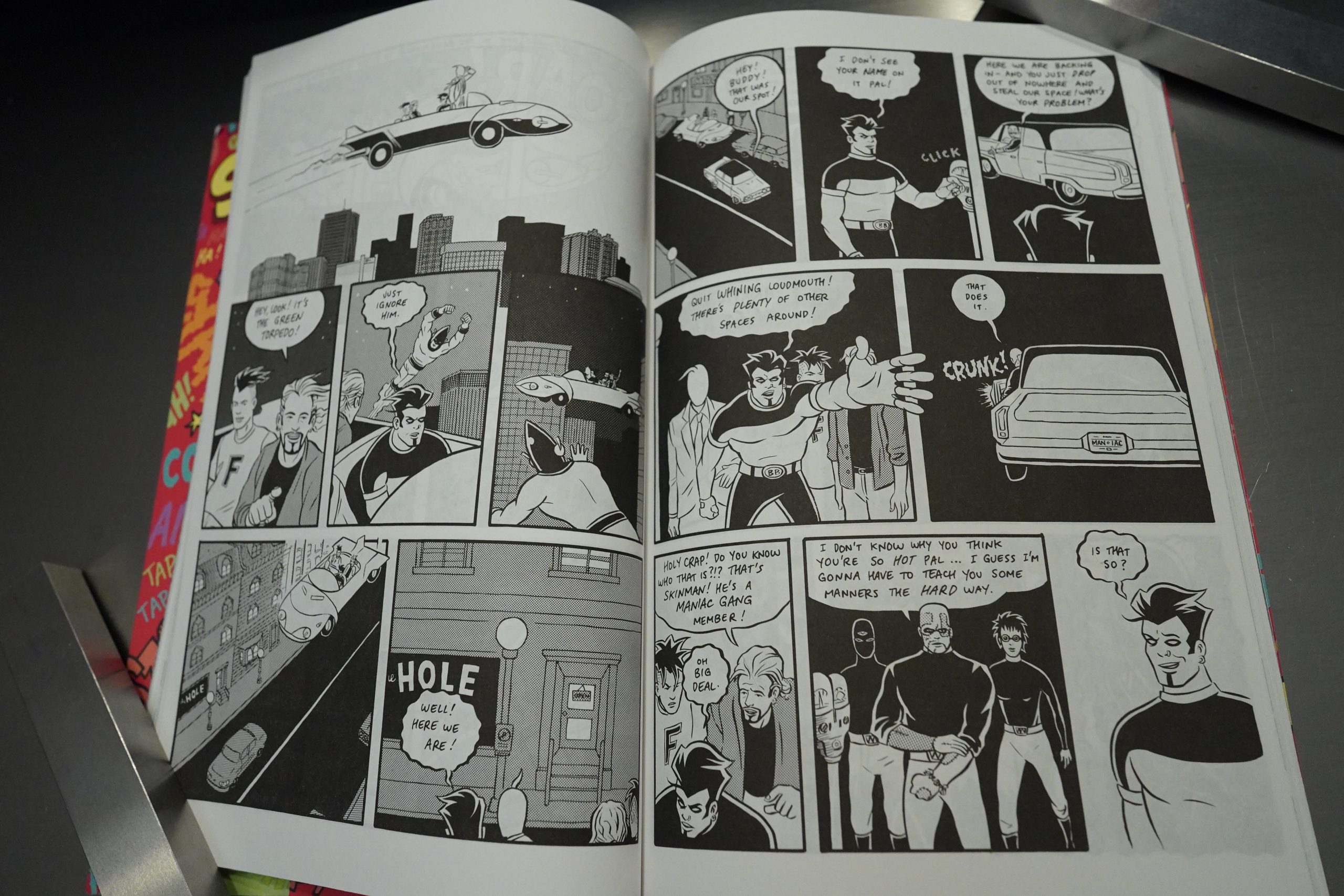

The earliest stories have more rough-hewn artwork.

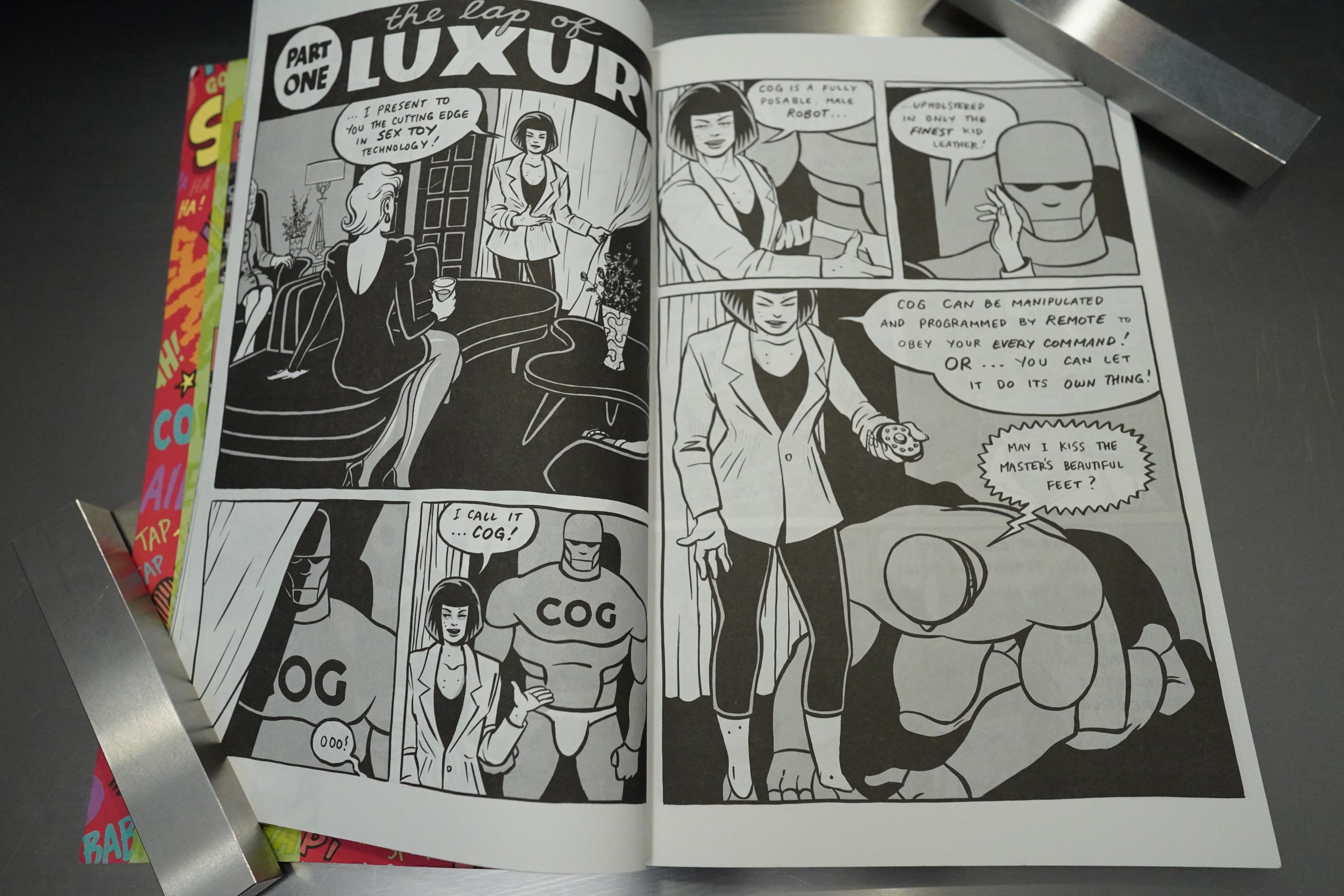

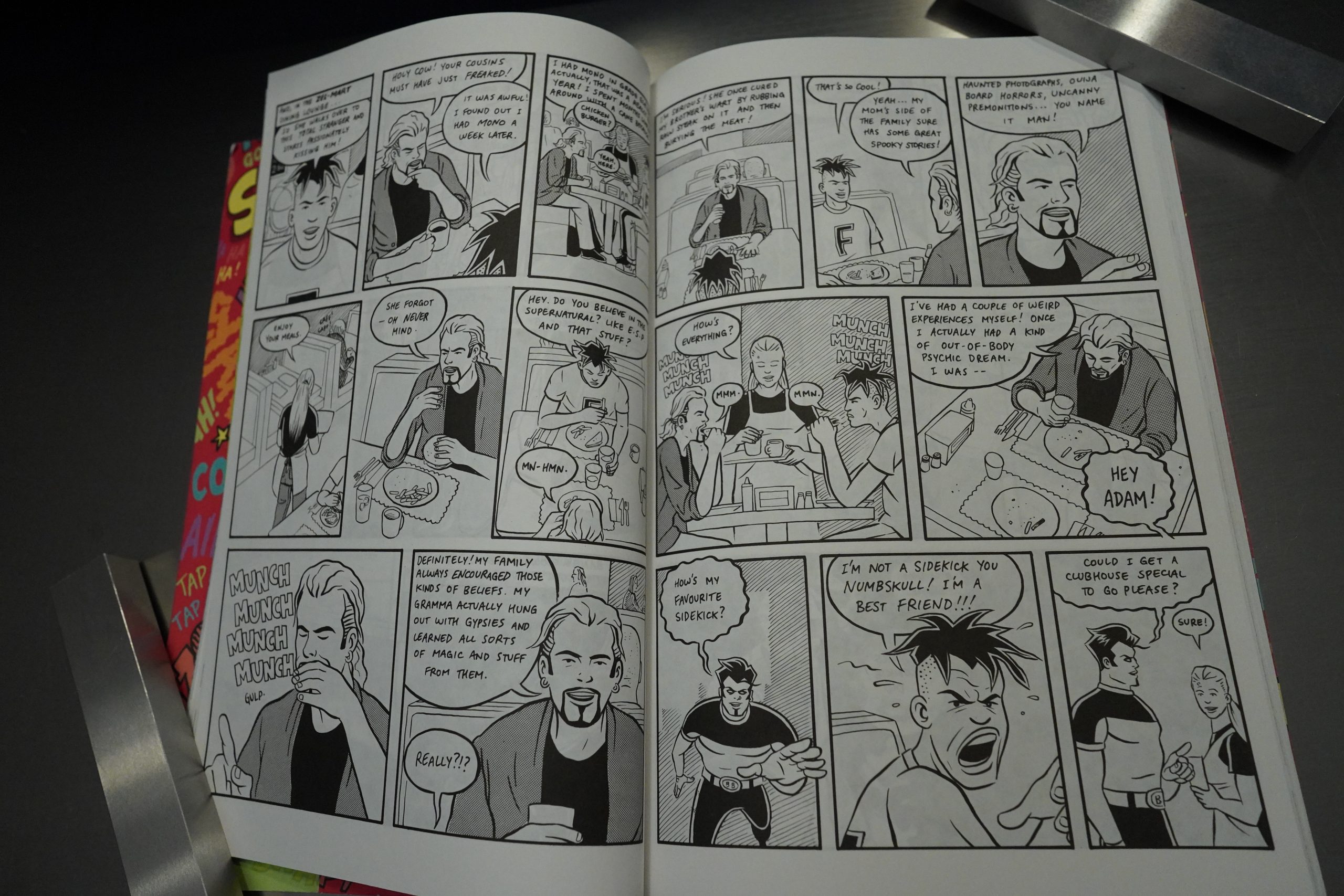

These were originally published in Stephens’ one person anthology Sin, I think? And you can see how the concept might have grown organically, from a pretty goofy “what if one of these slackers got the powers to change reality” to being a almost a super-hero comic book.

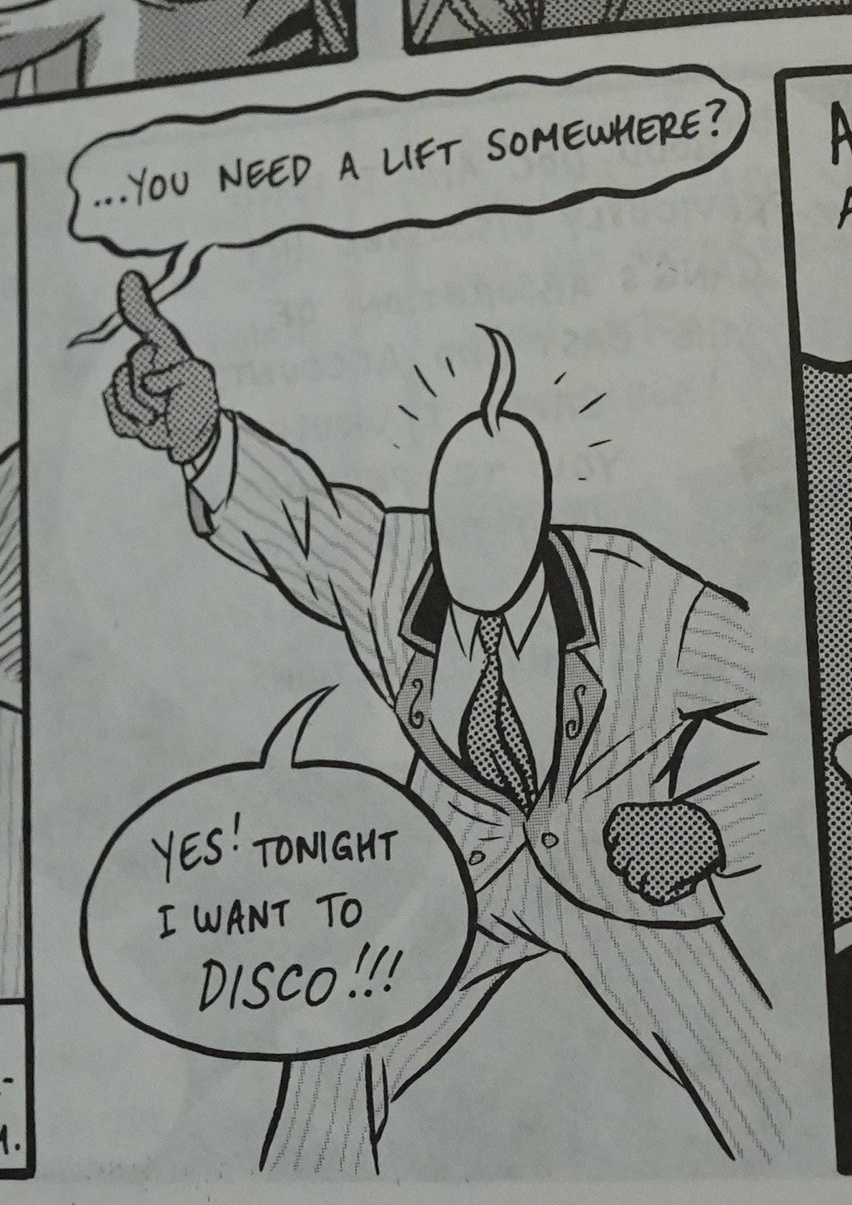

In interviews, Stephens said he got consistent feedback about the Atomic City stuff (as opposed to the rest of his material): People didn’t like it (as much as they liked his other stuff). It’s plenty amusing…

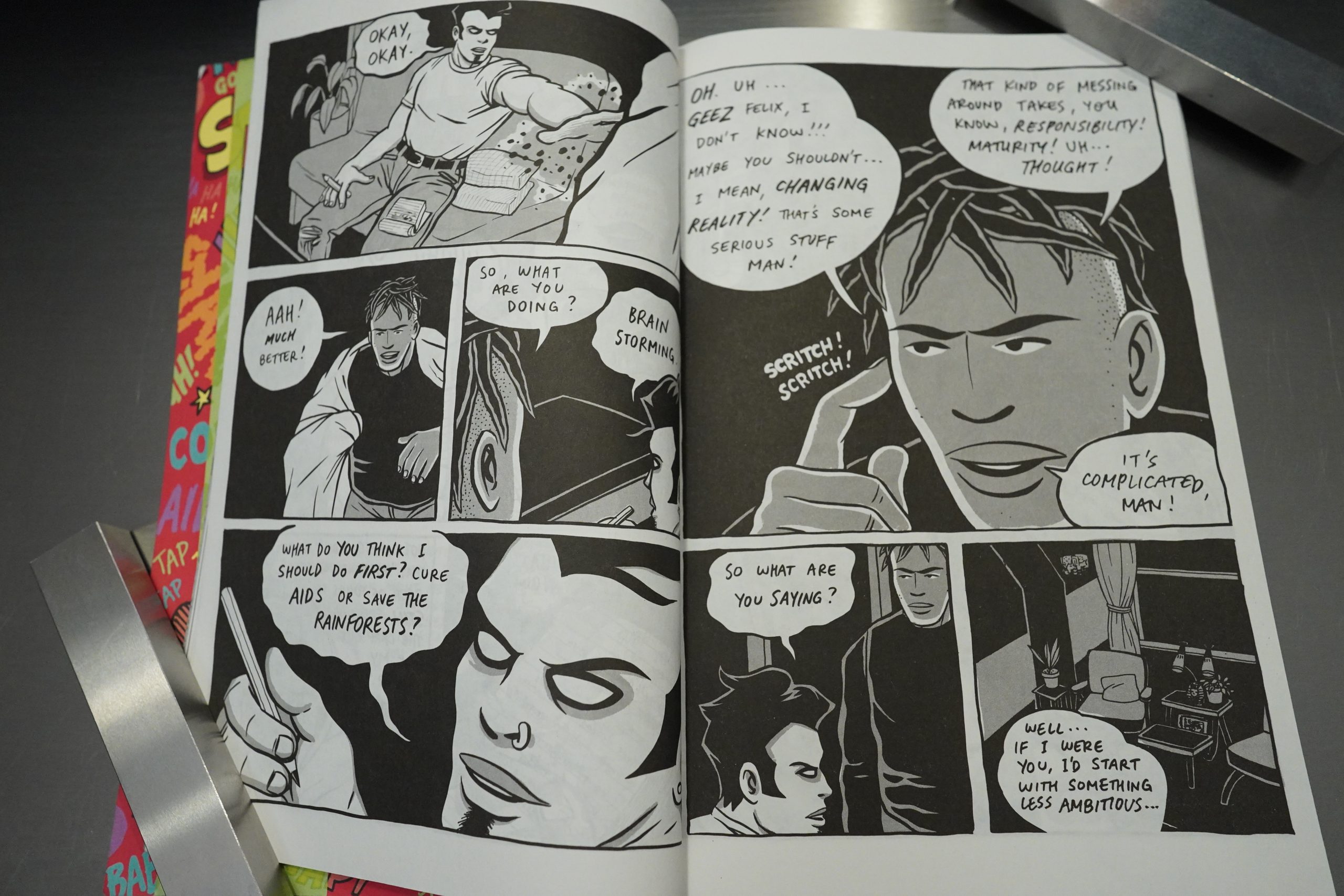

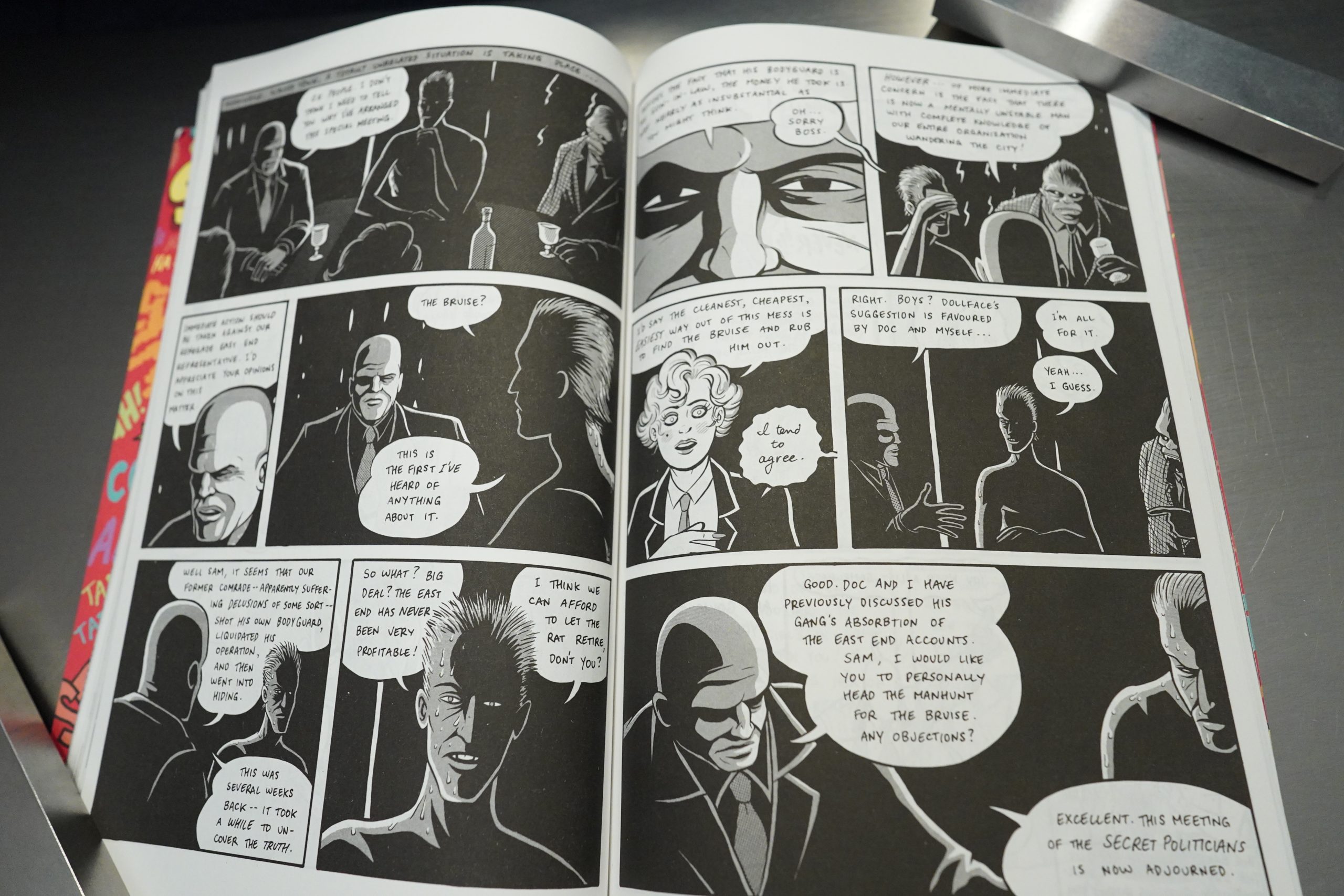

… but it doesn’t really seem to go anywhere. Which is perhaps not that surprising if it just sort of… grew… and reading the collection, it’s charming, but it’s not really compelling.

The artwork is extremely appealing, though.

But it’s like… he hand-waves at perhaps building to some sort of more complex narrative, but then nothing ever comes of it. I’m assuming he put scenes like this in just to fuck with people (“haha! you think this is going somewhere? I’ll show you!”), and I’m all for that, but in collected form, it’s hard not to grow impatient with it all.

I guess I never made the connection to Flaming Carrot before — this isn’t just inspired by The Jam or Mike Allred, but is perhaps also inspired by Bob Burden?

The storylines in this book all have endings of sorts, but they aren’t all that satisfying. I think reading this in a monthly book would be more satisfying — the lack of it all building towards anything would be less jarring.

After doing these stories for Black Eye, Stephens got feelers from Matt Groening’s Zongo Comics to take Atomic City Tales there. They dicked him around for almost a year, finally giving him a ridiculous contract where Zongo would own most of the rights to the entire concept, and he finally told them to go fuck themselves. (I’m paraphrasing a couple interviews slightly. Sliiightly.) He then took the series to Kitchen Sink, who were great about everything, but had economic problems, so things didn’t really go that well there either.

But before we leave this book and go on to talk about Kitchen Sink’s near-bankruptcy in 1997, Stephens has an interesting take on being published by small publishers like Black Eye.

Stephens is interviewed in The Comics Journal #212, page 95:

[talking about The Land of Nod]

STEPHENS: What happened is.. .Michel for some rea-

son decided that even though the artwork’s all messy

and rough, the lettering might have a bit too many

black flecks on it for reproduction. I was in Prague for

all of this. The issue should have been out and on the

stands before I left, and wasn’t, which was another

continuing problem with Black Eye. I mean, poor

Michel — I don’t know why he thinks it has to be a

one-man operation, but you can’t do everything. Any-

way , so first ofall he decided to Scan the lettering, clean

it up and drop it back in. Whatever. Thadshis preroga-

tive, I suppose, as a publisher. So he personally made

the mistake of dropping the same thing in twice, or

forgetting to drop something in. Thads fine. The

tragedy comes when the bluelines, which he’s paying

good money for, come in, and he doesn’t look at them.

He didn ‘t checkover the printer’s blueline copy, and he

had the book printed — the fill run — with errors,

which is a pretty big mistake. And from what I hear, in

the same couple of months that he did that was the

whole Black Eye disaster, which I don’t need to cover

— I mean, it was covered in an earlier Journal article.

There were missing pages in Bnlbakeds book He

printed poor Brian Biggs’ cover upside down — it was

a disaster. He forgot to ship books to a small press

convention — just a disaster. It was a mess. I’m

embarrassed talking about it.

SULLIVAN: It’s unfortunate, because he uas publishing a

lot Of teOrk. He Obviously cared about it. I’m sure he

either not making money or not making Very much

money.

STEPHENS: He was not making money. But that brings

up an interesting point. You say that as ifthaes a good

thing.

SIILIVAN: NO, no, r m not saying that’s a good thing.

I’m saying poor Michel.

STEPHENS: Yeah. Well, I think that was one of the

problems. I think that Michel though the was martyring

himself to get good comics out there, and what he was

really doing is not adequately promoting the works and

therefore not making the artists any money.

I don’t bear that much ill will. I mean, publishers

are publishers, and I pretty much know what to expect.

Yowza. That’s a harsh take on being a micro publisher.

Darcy Sullivan writes in The Comics Journal #196, page 112:

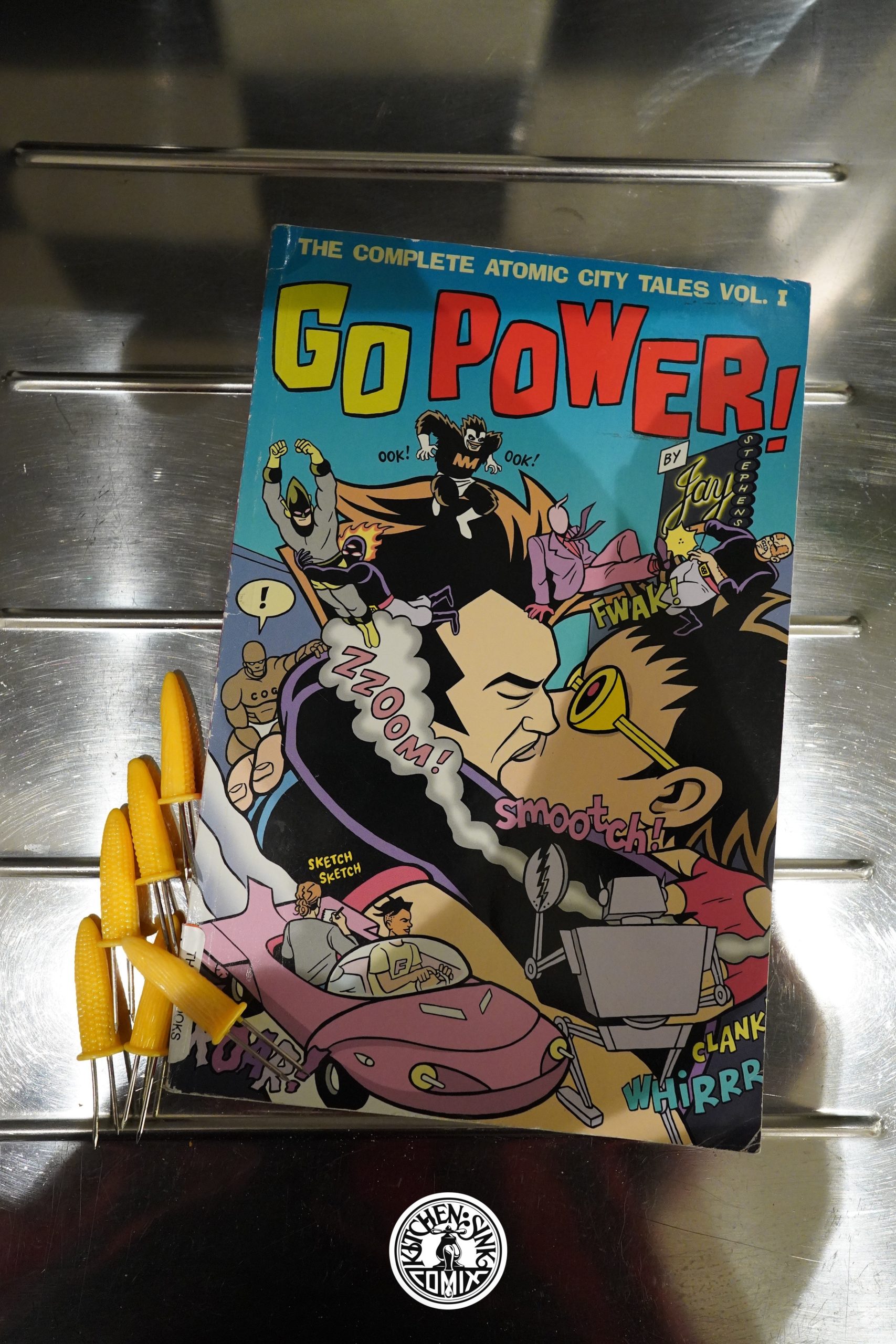

Any comics fan who doesn’t like

Jay Stephens’ work is a clod. That said, this book isn’t

the nirvana Of The Land of Nod, the greatest kiddie work

for adults on the stands. Go Power instead collects

Stephens’ silly superhero work from his Atomic City Tales

series, with some “Maniac Gang” strips from Black Eye’s

superlative, short-lived Sputnik anthology thrown in.

Even second-tier Stephens can make milk come out

of your nose. When Skinman upbraids a colleague with

“Quit goofing off Z-Girl! We’ve got a lot of evil to do

tonight!” — and when mood maestro Mike Mignola

pens a fannish introduction — you know you’re onto a

good thing. Atomic City Tales probably suffered by

sharing the market with Mike Allred’s Madman, which

also drained attention away from another superior romp,

Don Simpson’s Bizarre Heroes. But Stephens far outdoes

Allred in the laughs department, and if Kitchen Sink

would spring for some color we

might get a real horse race

going here.

On the other hand,

better we keep Stephens

focused on The Land of

Nod, his true claim to

comic genius. So buy this

book — c’mon, ya gotta

— but if you see Jay, tell

him you only kinda sorta loved

it. Liked it. I mean.

The Comics Journal #212, page 94:

SLLLIVAN: Now, you had a collection of this, called Go

Power. That really sneaked out.

STEPHENS: It didn’t sneak out, it’s the last thing that

came out before Kitchen Sink went temporarily bank-

rupt. Again, my timing could not have been worse.

The collection had been printed, and Kitchen Sink

didn’t really exist any more. There was no system to get

itoutthere. I think the initial orders wentthrough, and

then that was it. les been remaindered at Diamond,

so. another disaster.

SULLIVAN: Did you end up with Kitchen Sink owingyou

money ?

STERENS: Oh no, they were great! I loved working

with Kitchen Sink. Denis is great. I wish I’d done

better by them. I wish I could have put it out faster, and

I wish I’d had that clear vision I was just talking about.

[laughs] It was just bad timing. They were in the

middle Of that mess with the second Crow film. They

were kind enough to apprise meofthe coming troubles,

but I truly did think they were out of business for

awhile, which was when I moved to Europe, and I

didn’t know they were back till much later. But when

I did find out they were in business and I gave them a

call, they promptly paid me. I had no problem. Of

course, when the Journal did the report on that, they

didn’t bother to call me. [laughs] They never call me

for news, because I only have good news. What news

would that be?

OK, back to Kitchen Sink’s woes.

The Comics Journal #196, page 9:

After weeks of speculation that the

struggling Kitchen Sink press was on

the verge of shutting down, the

company’s taunder and president

Denis Kitchen — desperate to find a

“white knight” to help hint buy back

his company froin shareholders who

had withdrawn financial support

earlier this year— was able to secure

a statement ofinterest from a possible

new Investor on Thursday, June 4,

one day before a deadline to repay a

loan owed to the company’s bank.

(According to Kitchen, if the bank

calls in the loan, a probable scenario

would be the liquidation of company

assets to pay the loan.) The move

gives Kitchen and his brother Jim

(V.P. m charge of production) an

additional month to engage in further

discussions with a small group Of

interested parties — that at one at

time included Diamond Distribution

before a deal between the two

companies apparently fell through,

Kitchen acknowledged, partly due to

opposition from one or more of

Diamond’s exclusive suppliers. But

while it appears that Kitchen still has

chance to save the company, 18 of

KSP’s 30 enlployees reportedly have

been laid off, KSP projects scheduled

to ship through September are in

limbo, and the company has recently

relocated its offices after having

problems paying rent at its previous

location in Northampton, Mass.

The Comics Journal #197, page 7:

NEW LEASE ON LIFE

FOR KITCHEN SINK?After narrowly averting a shutdown

in June, Kitchen Sink Press founder

and president Denis Kitchen has re-

portedly secured a letter of intent

from a prospective investor to help

him buy back his company from a

current group of majority sharehold-

ers who informed Kitchen earlier this

year that they were withdrawingtheir

financial support from the company.

While the interested party is currently

examining KSP’s assets — a process

that could several weeks — KSP’s

senior director ofsales and marketing,

Jamie Riehle, confirmed to the Jour-

nal that KSP has “what we hope are

the investors that we need in place”;

and although “there’s still an enor-

mous amount of paperwork and le-

galities that have to be gone through,

the company is resuming at least part

ofits publishing schedule in the hopes

of getting some books out in time for

Comic-Con International, held July

17-20 in San Diego (Kitchen was

absent from the KSP offices and un-

available for comment following his

wife’s recent childbirth).

But even if the company has in-

deed found its “white knight,” the

period of uncertainty took its toll.

More than halfofthe staffwas laid off

in May, and at least two of KSP’s

projects — the alternative anthology

Blab! and Larry Welz’s racy adult

comic Cherry — have broken ties

with their former company in the

midst Ofthe upheaval.

The Comics Journal #202, page 19:

The financial maneuvering that al-

lowed Kitchen Sink Press to

re-emerge from near-bankrupcty last

year also left in its wake a whopping

debt of approximately $2.25 million,

much of it completely unrecoverable

by the creditors. Kitchen Sink press

found its financial savior last fall in the

form of TV producer Fred Seibert,

whose invesunent— along with capi-

tal from Denis kitchen, Jim Kitchen,

and DreamWorks’ Robin Sloane —

in Disappearing, Inc. led the group to

buy back KSP’s assets from a bank

that had foreclosed on KSP’s million

dollar loan. But while Seibert’s move

saved KSP as a publisher — allowing

the new company to begin rebuild-

ing, move to new offces and rehire

employees that had been laid of —

the old company, KSP Inc., was most

likely dissolved, Kitchen said, and as

such, is no longer responsible for the

debts it incurred during the period Of

financial turmoil.

According to Kitchen, the bank

received all of its money back — the

biggest losers from the default were

the old investors — such as New

York lawyers Leonard Lichter and

James Spitzer. along with Pierre

as guarantors when the bank agreed

to gave Kitchen the loan in 1996.

And many Ofthe unsecured creditors

— such as printers, manufacturers,

and others who did freelance work

for KSP — who were owed money

when KSP defaulted have no hopes Of

ever gettingit back, although Kitchen

said that he had “voluntarily” paid

“the vast majority” ofKSP’s creators.

The financial turmoil at KSP last

year stemmed in part from two major

losses: the July 1996 demise ofCapital

City Distribution, which had signed

KSP as an exclusive supplier, and the

box-offce failure of The Crow: City of

Angels, the success of which KSP had

gambled on by producing far more

merchandise than they were able to

sell. By January 1997, the investors

who were keeping KSP afloat — the

same group that included Lichter,

Spitzer and Schoenheimer — told

Kitchen that they were withdrawing

their financial support, an announce-

ment which set Kitchen offin search

Of a new backer(s). The parties who

discussed investing in KSP included

Diamond Distribution owner Steve

Geppi — but that deal fell through

amidst rumors that Dark Horse, One

of Diamond’s exclusive publishers,

owed; not counting the previous in-

vestors, the largest portion of the

debt, he estimated, was owed to

Ronalds, a printer that såll does business

with KSP. artisß and writers who

were owed money, Kitchen added, were

paid voluntarily Out of the new Influx Of

money from the new invstors[…]

Because the new corporation

purchased only the assets ofKSP and

none Of the liabilities, Kitchen said,

much of the debt incurred by the

now-defunct KSP Inc. is unrecover-

able by the creditors to whom it is

problems at KSP, his initial response

sympathetic: “l aware that it

was happening.. I felt bad for Denis

personally — duis could be happening

to me personally as a businesman —

and hoped for the best.

But when he approached

Kitchen at last year’s Comic-Con

International inJuly, while the refi-

nancing was still taking place,

Kitchen explained to him that he

was unlikely to ever get paid for his

work. Sawyer followed up on the

matter on Sept. 15 through his law-

yer, who requested information

which would confirm that KSP had

insuflcientassets to pay the $17 ,253

the company owed Sawyer — and

after receiving several documents

relating to the sale, Sawyer’s lawyer

informed him that KSP was not ob-

ligated to pay him.

“I’m upset but I don’tknow that

I have any further recourse,” said

Sawyer. “According to U.S. business

law they don’t owe me any money. I

would suspect in a very cynical way

that the sale is above board and is

perfectly legal”

• ‘The only thing that’s tarnished in

this is the reputation of Denis Kitchen

as the savior ofthe little guy,” Sawyer

added, well as the notion ofKSP “as

an artist-friendly company where art-

ists have an Oasis from the corporate

practices of the major companies.”

Kitchen responded to Sawyer’s

complaints by stating all of the credi-

tors in position had been

informed Of the transaction and

seemed to understand what had hap-

pened.

Hm! I can’t find any news from the time period then the Fred Seibert takeover was taking place, but here’s a later retelling:

The Comics Journal #213, page 24:

“He gave me a long

convoluted story of how

he had stood up to the FBI and

wouldn’t be a stool pigeon against a

friend,” Kitchen said. “He put it in

terms of being a hippie outlaw. The

FBI Was out to get him. The truth is

he got caught doing something ille-

gal. I remember being a little

nonplussed, but one thing he is is

charming. He’s a charming scoun-

drel. and his tactic worked on me.”

Having convinced Kitchen,

Todrin rolled up his sleeves and set to

work casting a spell on the Ocean

investors. By the time they left the

meeting, thanks largely to Todrin’s

presentation, Kitchen had everything

he had wanted from the Ocean Group

and a free rein to strike a new invest-

ment deal with Fred Seibert.At this stage of the game, KSP

had been foreclosed upon after de-

faulting on a $1 million bank loan.

That loan was personally guaranteed

by certain Of the Ocean investors,

including Kitchen, and those guaran-

tors were forced to come up with the

money to repay the loan. Kitchen’s

share ofthat repayment was $25,000.

Having covered the loan, the guaran-

tors were in possession of KSP assets

and looking for a buyer to take them

over. The Kitchens formed Disap-

pearing Inc. to negotiate the

acquisition of KSP on behalfof new

investors. After Geppi fell out, Seibert

became the principal investor of a

group which also included, in addi-

tion to Jim and Denis Kitchen,

money paid to the guarantors. Seibert

and his small group Of investors put

up the entire amount (in a down

payment, monthly installments and a

final lump-sum payment) in exchange

for 70% interest. The Kitchens to-

gether retained 30% equity in

recognition of their expertise and

experience with the company. Seibert

obtained the assets ofKSE, but not its

liabilities, so unsecured creditors were

out ofluck, and more than $2 million

in debts were left unpaid. Kitchen

claimed that, at his insistence, KSE

creators were paid what they were

owed, usingDisappearing Inc. money.

Todrin’s powers of persuasion

were less successful with the FBL The

investigation was resolved when he

pled guilty to bank fraud. Todrin was

disbarred and sentenced to house ar-

rest, required to wear a monitoring

device on his ankle and allowed to

leave his home only during working

hours.

“We’d be in a meeting,” said

Kitchen, “and it’d get to be 5 or 6

p.m. or whenever his curfew and,

all of a sudden he’d say, ‘I’ve gotta

run,’ and we’d say, ‘Can’t it wait—

the meeting’s almost over,’ and he’d

say, ‘No, I’ve really gotta run. ‘ When-

ever a bunch ofus got together to play

poker, it always had to be at his house,

because he couldn’t leave.

Once the full story of his bank-

fraud sentencing came out, Kitchen

and Grover said, Todrin showed no

shame or remorse around the Kitchen

Sink offices. “The ankle bracelet was

always visible, because he always wore

shorts, even though he’s probably not

the sort of person who should wear

shorts,” said Kitchen. ‘ ‘He wore the

bracelet like a badge of honor.”

Grover told the Journal, “He

would put his feet on the table be—

cause he wanted you to know they

were there.”

Ankle bracelet aside, Todrin’s

hard-sell manner quickly began rub-

bing Kitchen Sink staff the wrong

way. According to Grover, “He’d say

stufflike, ‘Here’s the problem. Here’s

the solution. We’re gonnna sell stuff,

because we’re a sales-driven com-

pany.’ The next week he’d come in

and say it was up to the marketing

department. because the sales staff

was worthless.”

Whoever else he was alienating,

however, Todrin was winning over

the biggest customer ofall. “As I was

gradually starting to see Don Todrin

for what he was, the opposite was

happening with Fred Seibert,”

Kitchen told theJ0umal. “He tho*t

Don was the most fabulous person in

the world.’ •

But now we’re into the next part of this epic saga, when Todrin fucked Denis Kitchen over, which we’ll cover at the end of this blog series (which will be the “Mona” post).

This is the two hundred and sixth post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.