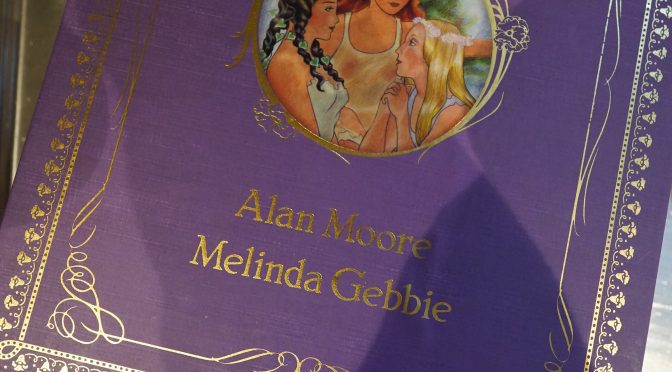

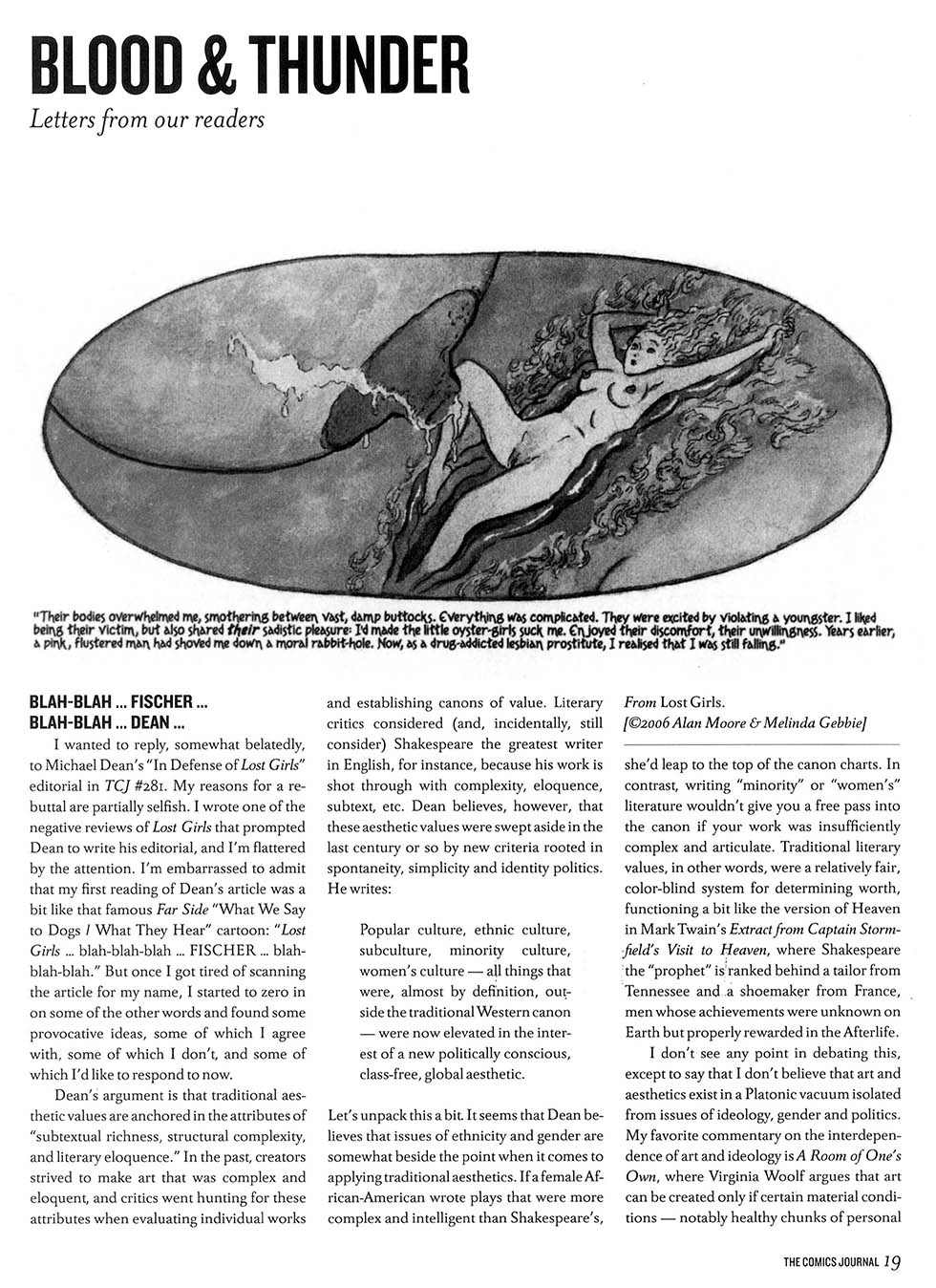

Lost Girls (1995) by Alan More and Melinda Gebbie

Welp! It’s been over a month since the last time I did one of these Kitchen Sink posts… which you will not have noticed, since I had a month’s backlog, so I think I only missed one day of posting?

I’m not quite sure why I put off doing Lost Girls — I love Melinda Gebbie’s artwork, and I quite like Alan Moore’s writing. But I vaguely remember this reading a lot like a whole lot of wink-wink recaps of The Wizard of Oz/Alice in Wonderland/Peter Pan, and 1) I loathe recaps and 2) I’ve never been a fan of either the Oz books or Peter Pan (while I quite like Alice in Wonderland).

Whatever the cause, I procrastinated for a month, but if I’m ever gonna get this stupid project done, I have to get to it. *rolls up sleeves*

Oh, and I guess I should give a little content warning on this one: There are sexually explicit drawrings in this blog post, so C-w if you want to avoid those. (But I’m not snapping any of the pages that might get this blog taken down, m’kay?)

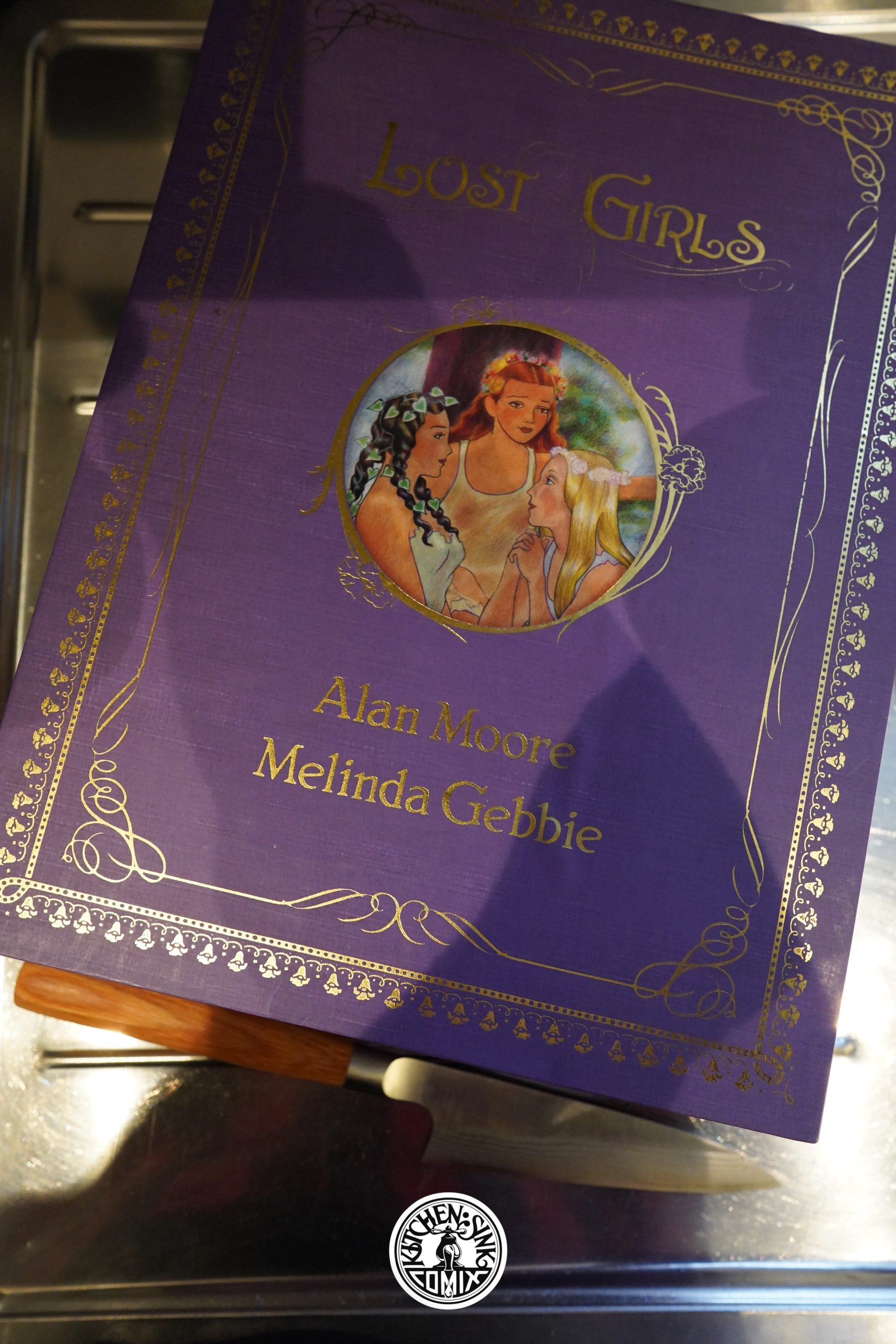

The edition of Lost Girls I have here isn’t the Kitchen Sink one, but the three-hardcover-in-a-slipcase edition from Top Shelf in 2006. The first five chapters were serialised in Taboo, and Kitchen Sink then published two issues collecting those chapters, adding two more chapters. And then stopped — Kitchen Sink hadn’t yet gone under (for the final time), so I’m not sure why the collections stopped. I remember people being surprised when the Top Shelf collection dropped: I think people assumed that it had been abandoned (like Alan Moore’s Big Numbers series).

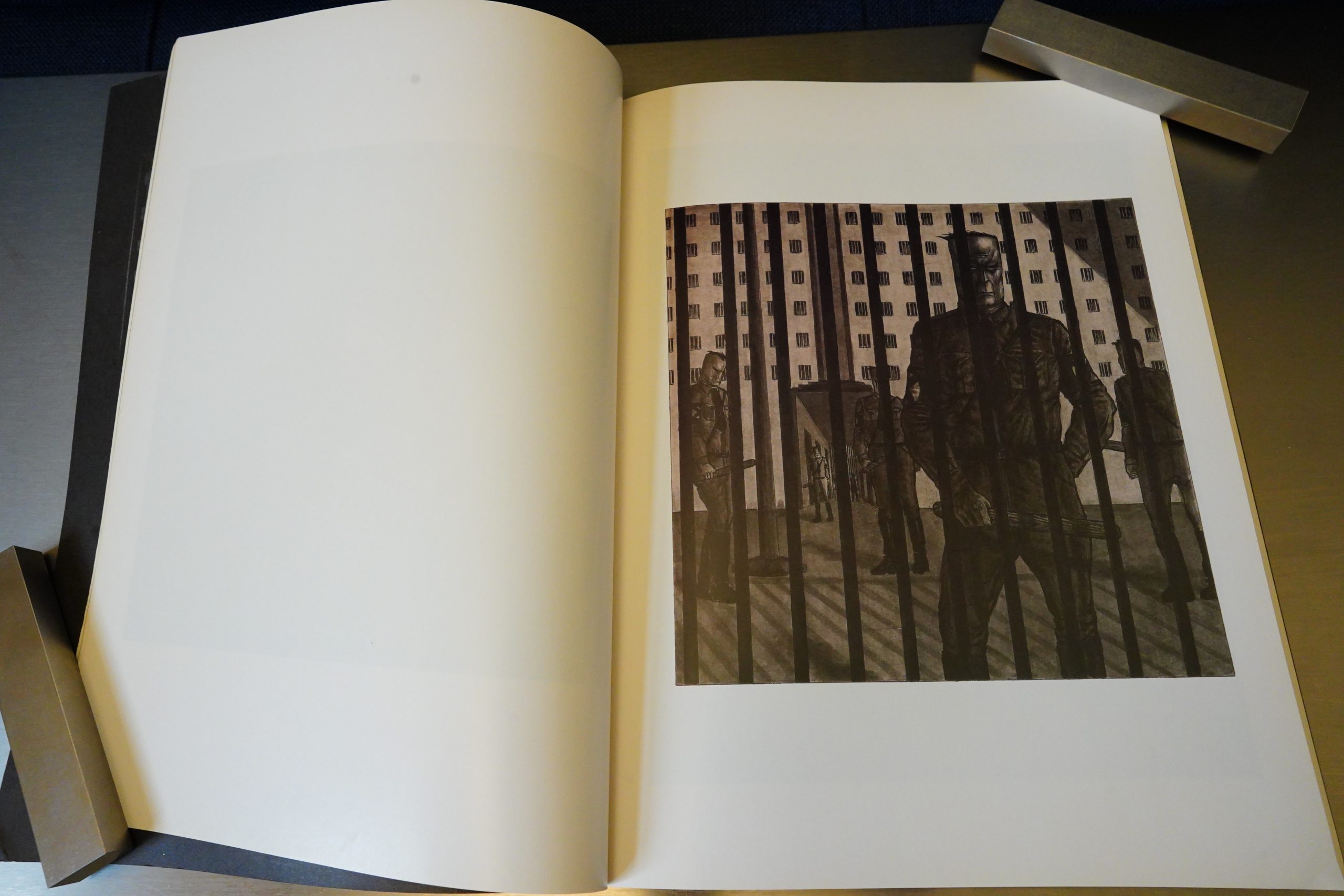

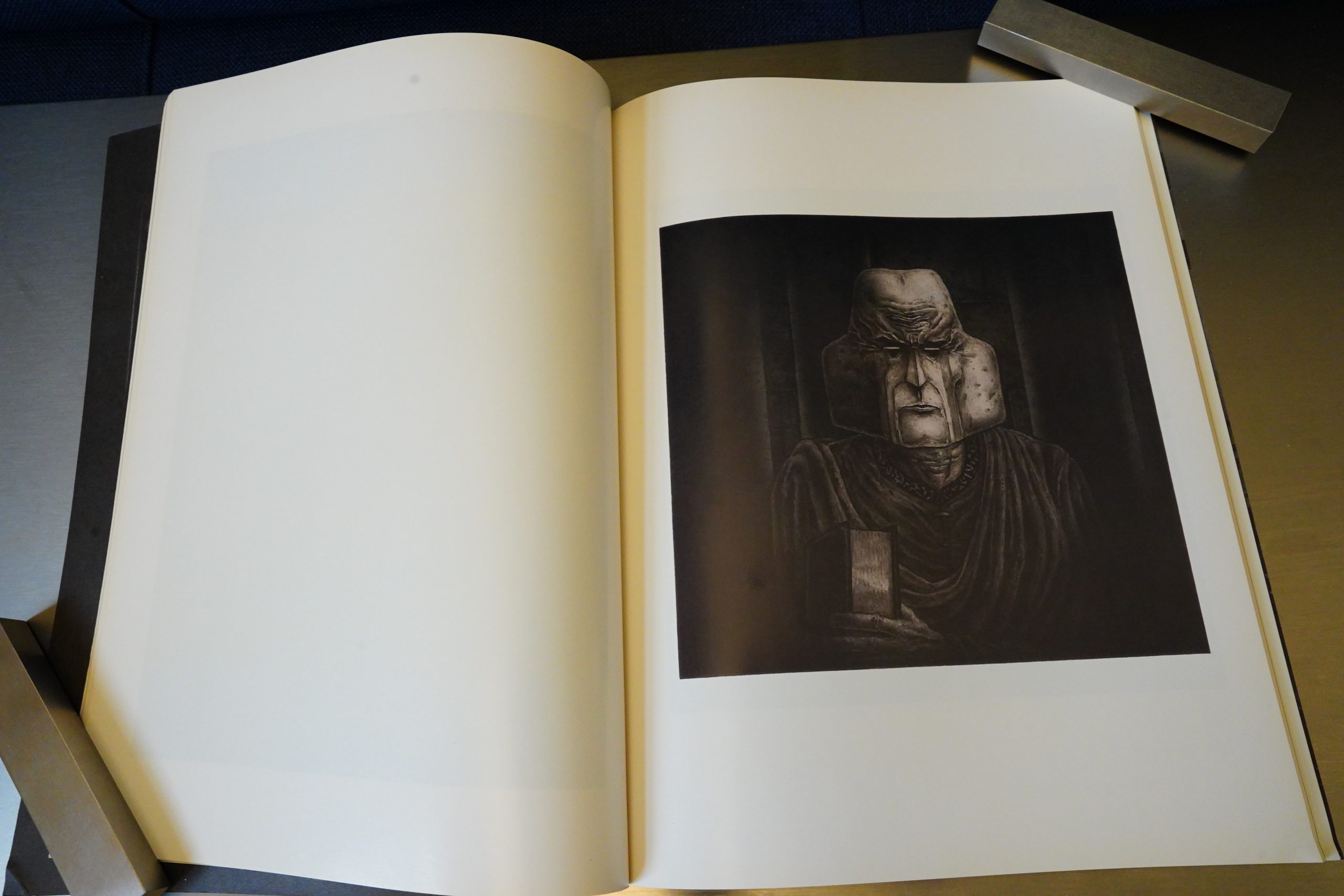

The Top Shelf thing does everything it can to signal that it’s Serious Stuff, Not Porn At All, Mr. Customs Officer. It’s in a classy box set, weighs several kilos, and is printed on matte paper (the Taboo chapters were on shiny paper).

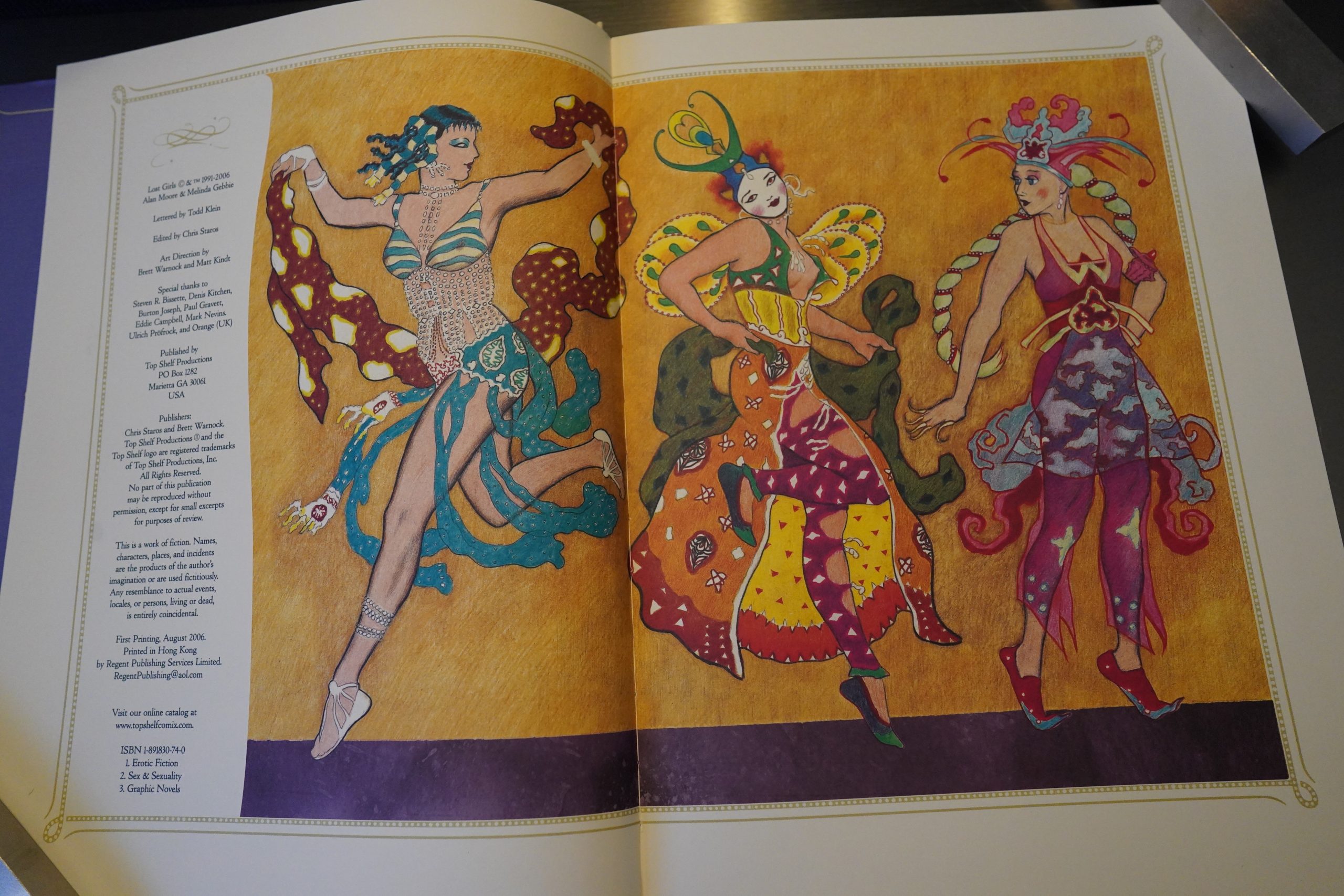

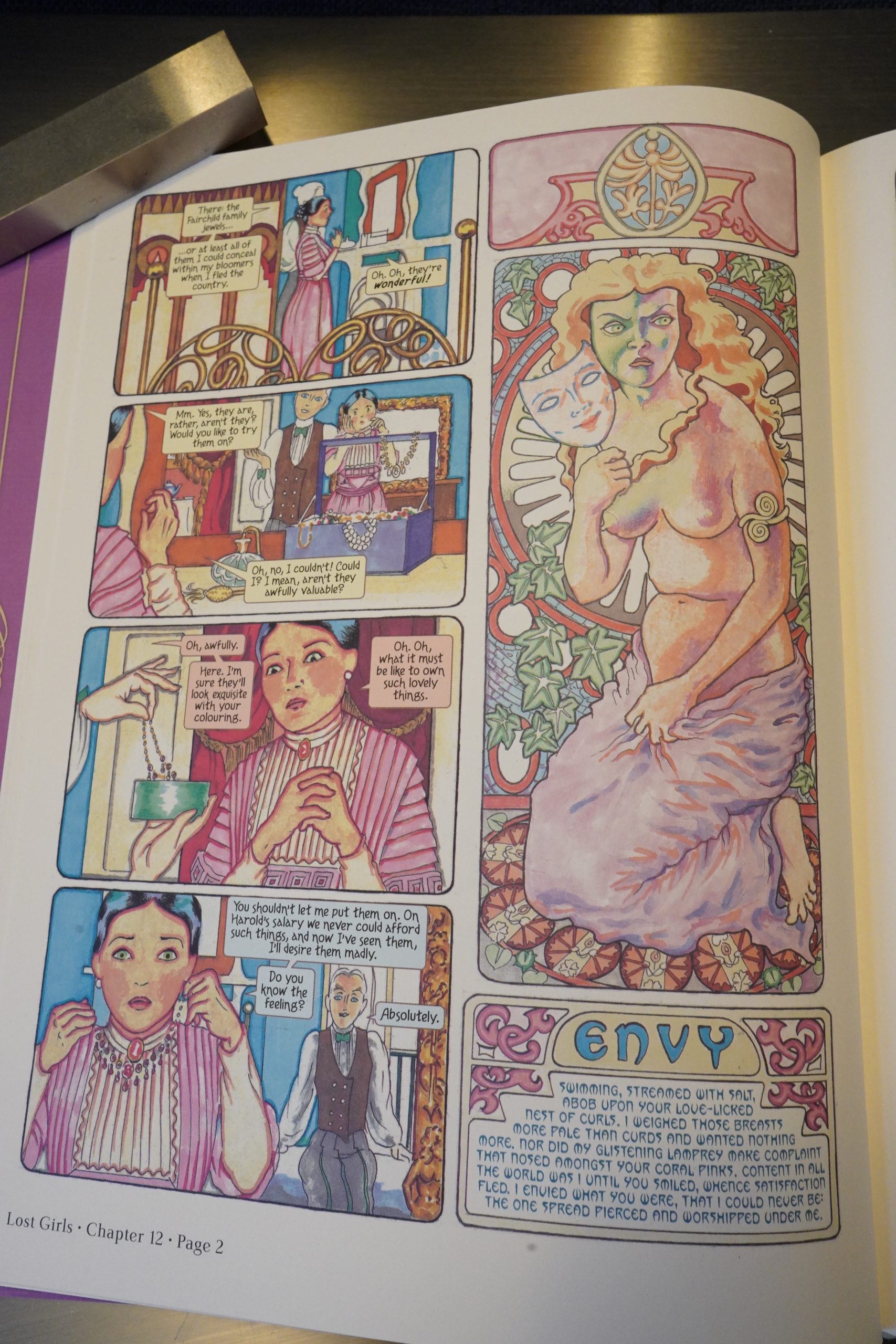

And it looks great! Gebbie’s colour pencils are reproduced wonderfully here.

But as is often the case, “classing it up” in the US often means “adding more”, so we get a text on each page saying “Lost Girls, Chapter 1, page 3” which just seems annoying.

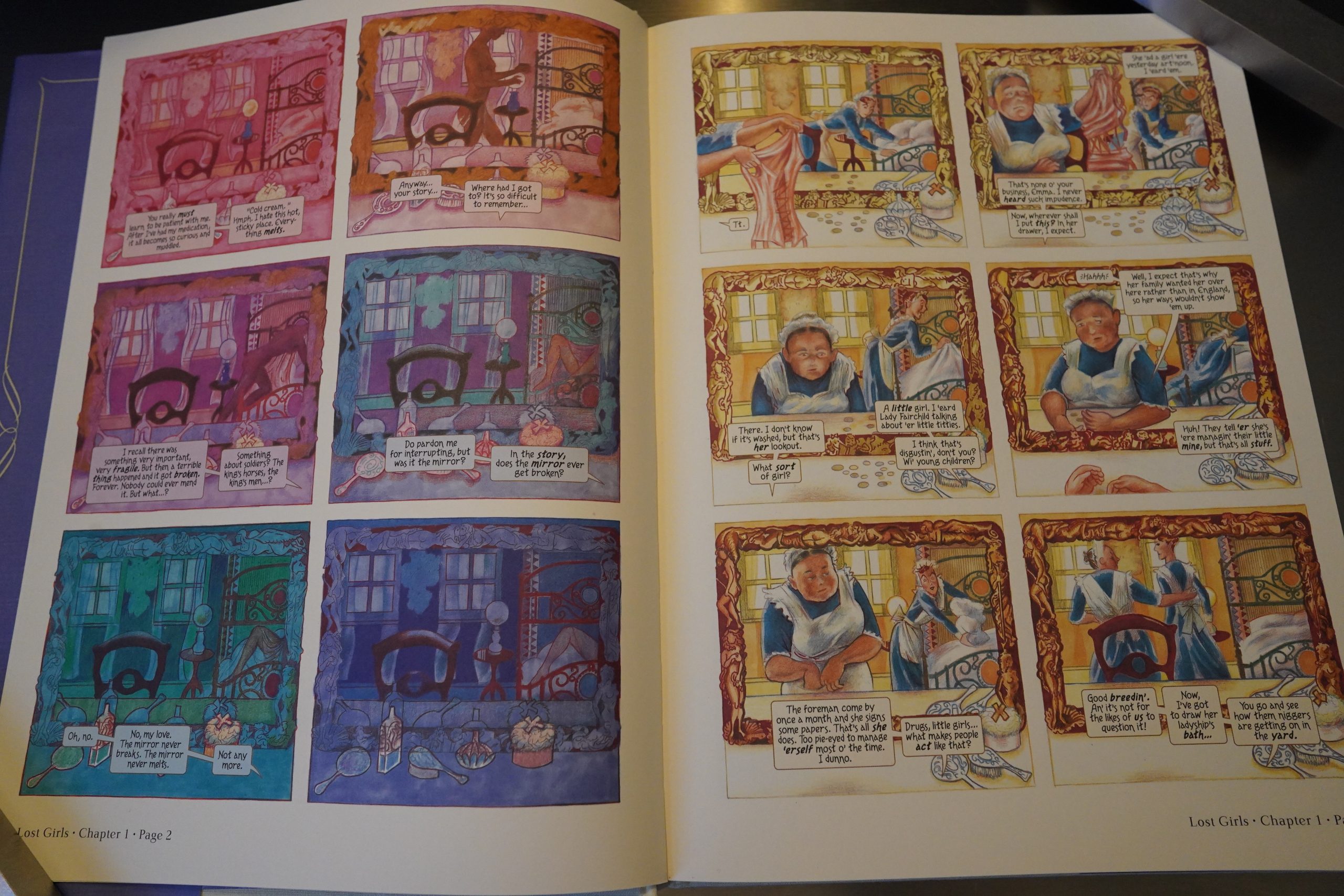

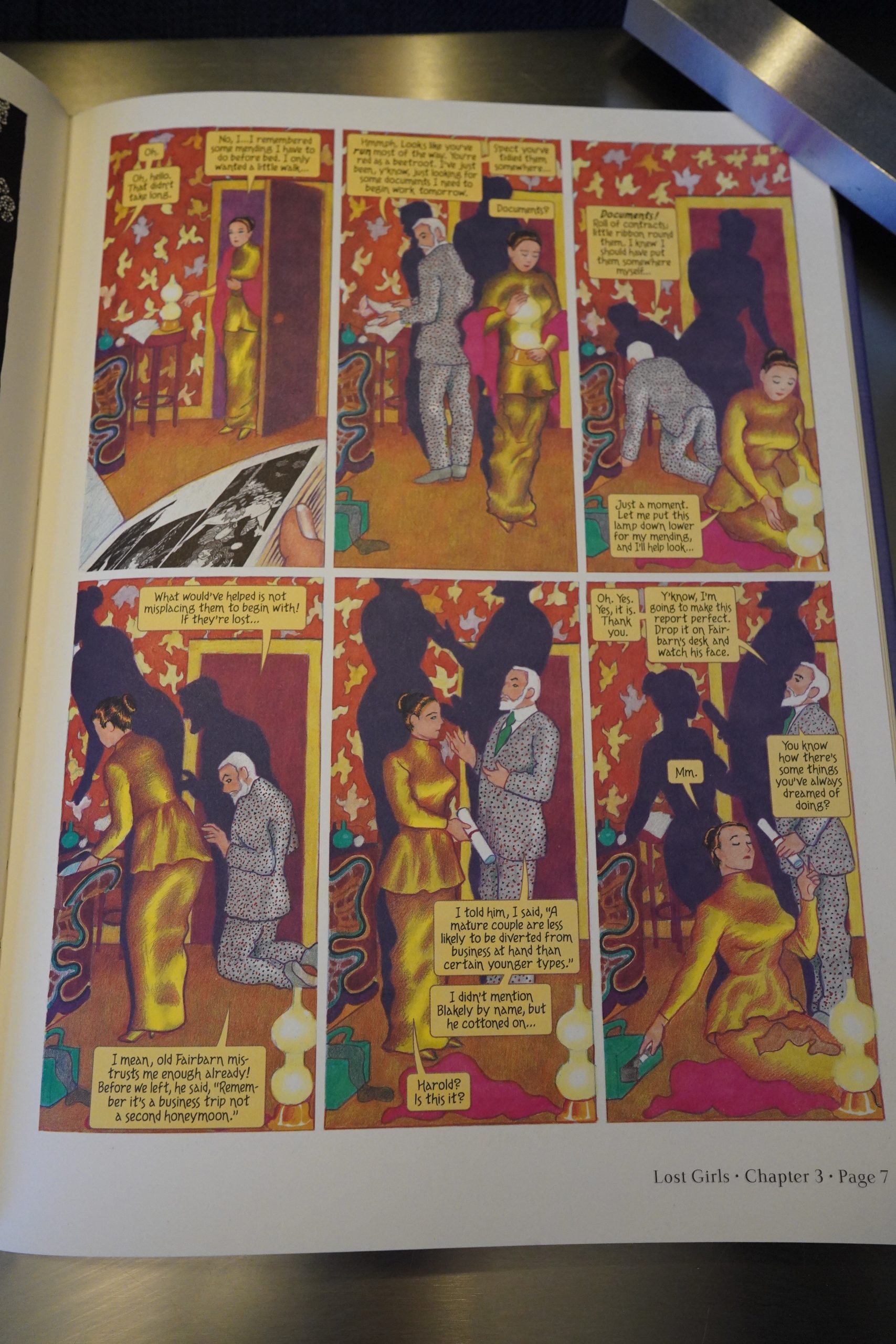

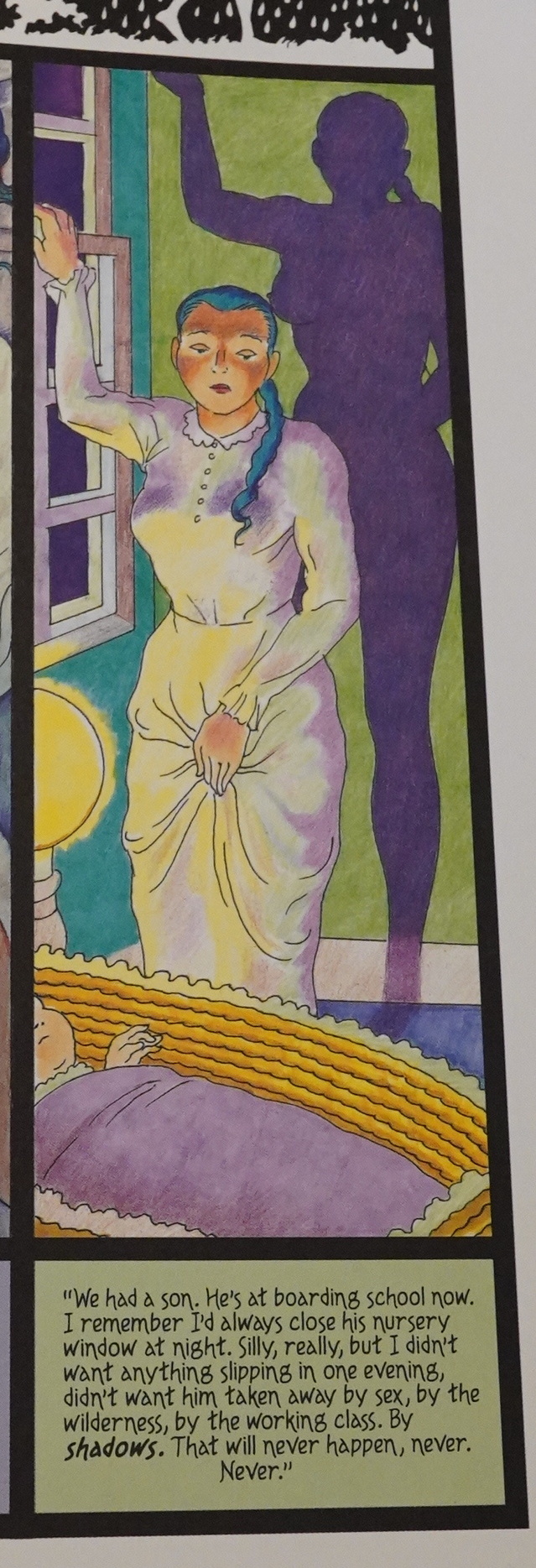

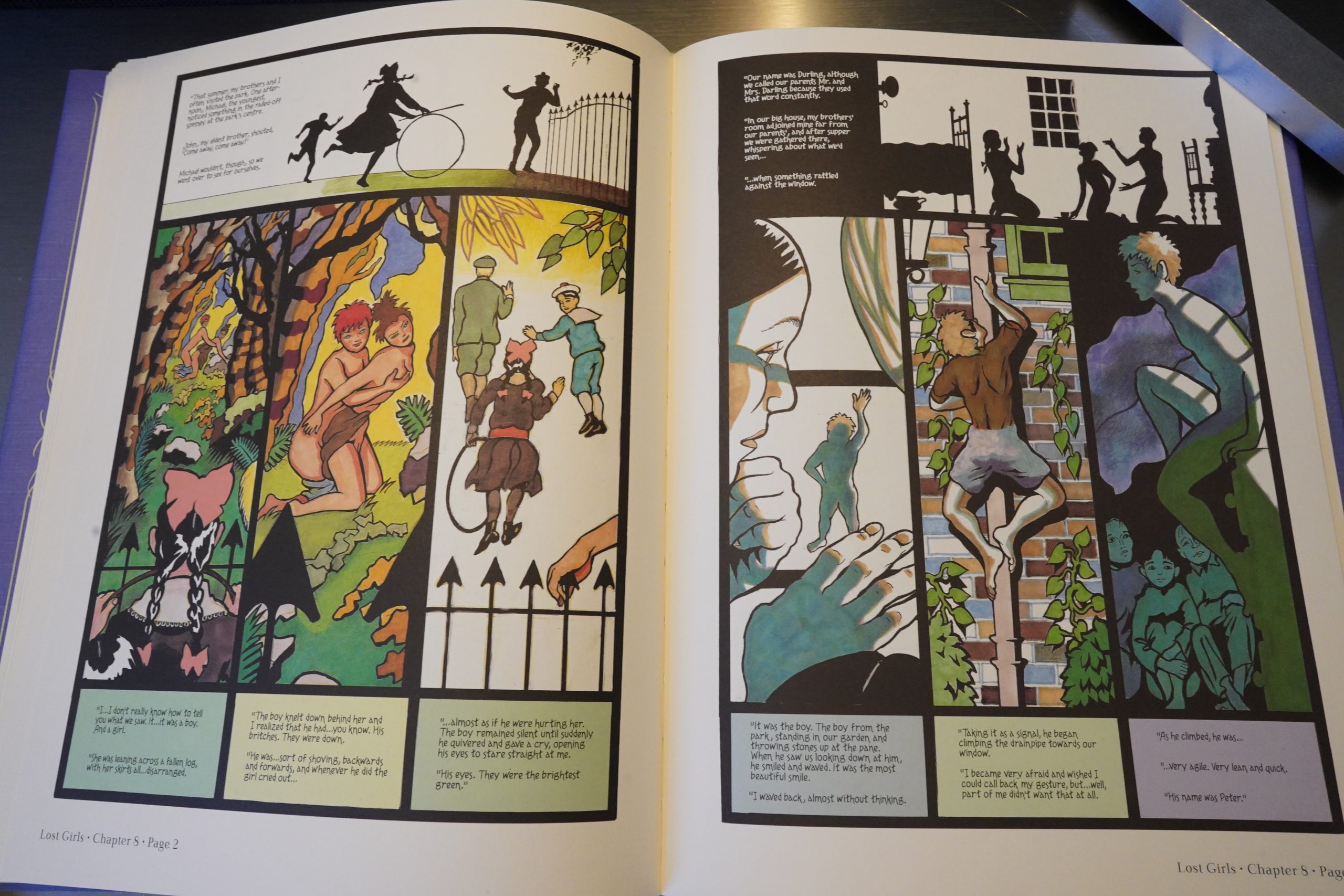

This is a page that gets cited a lot — probably because it hints at sex without actually showing it, but more importantly, because it shows how “clever” Alan Moore is. Look! The shadows are having sex! While everything they say can be interpreted as double entendres! Clever!

If my eyes could roll any faster, they would.

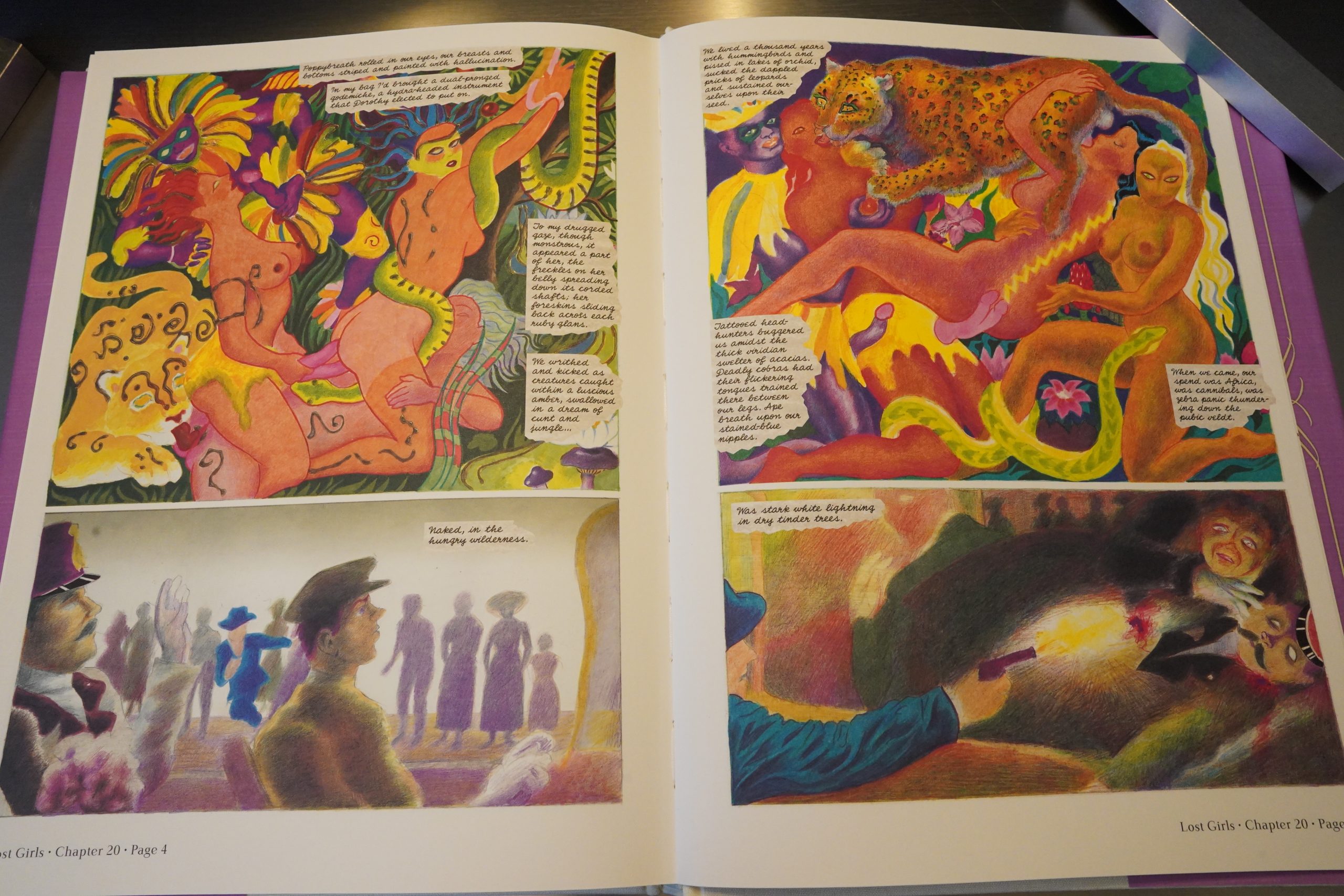

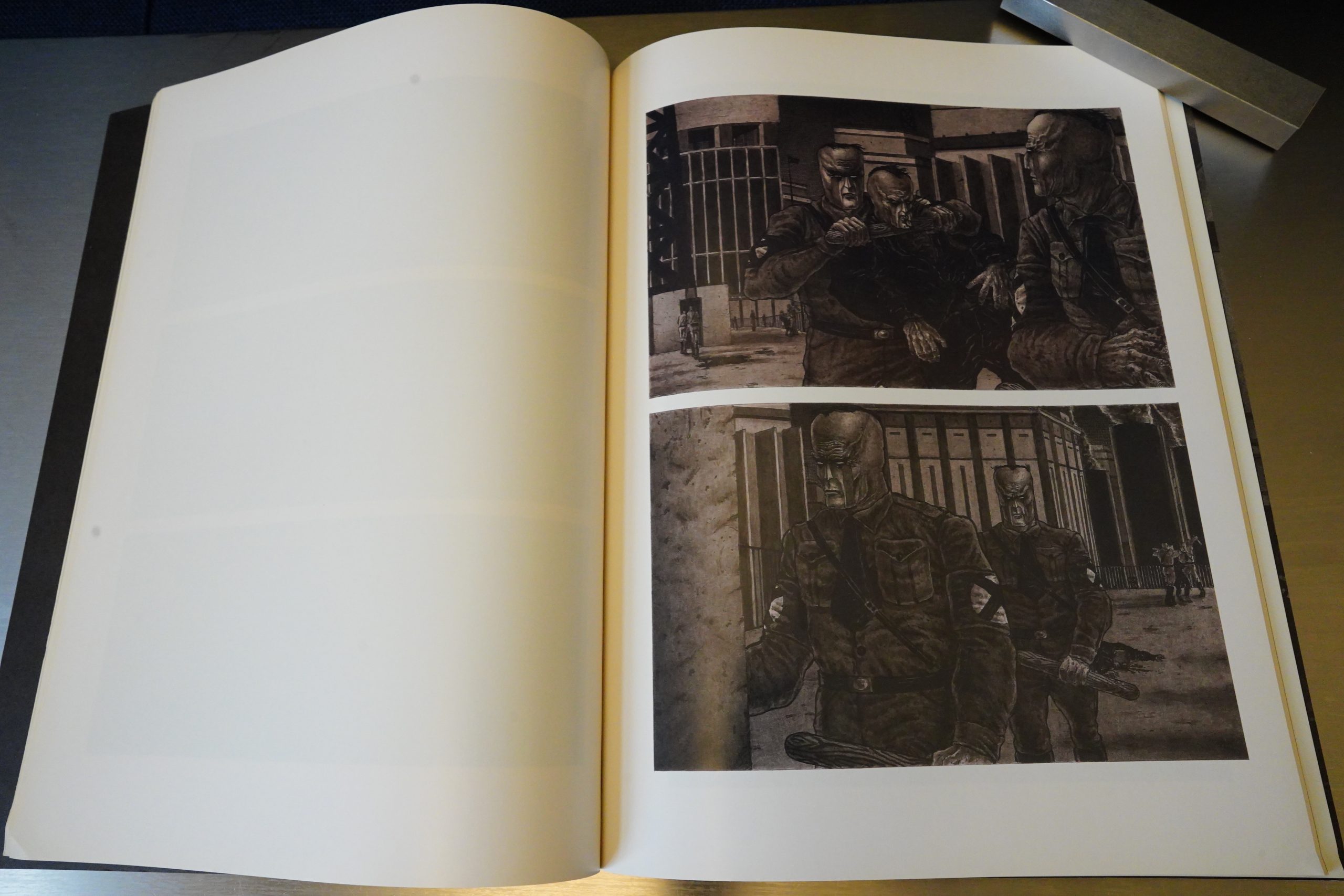

The set consists of 30 eight page stories, and Moore and Gebbie gets a lot into each eight page stretch. Most of these stories consist of Wendy (from Peter Pan), Alice (from Alice) or Dorothy (from Oz, shown above) tell a bit of their familiar stories to the other two (who are usually masturbating at the time). But the schtick is that everything we know from the stories are actually bowdlerised versions, where the “real story”, is about the people in the stories having sex.

So Oz is a metaphor fox sex, Peter Pan is a metaphor for sex, and Alice in Wonderland? You guessed it.

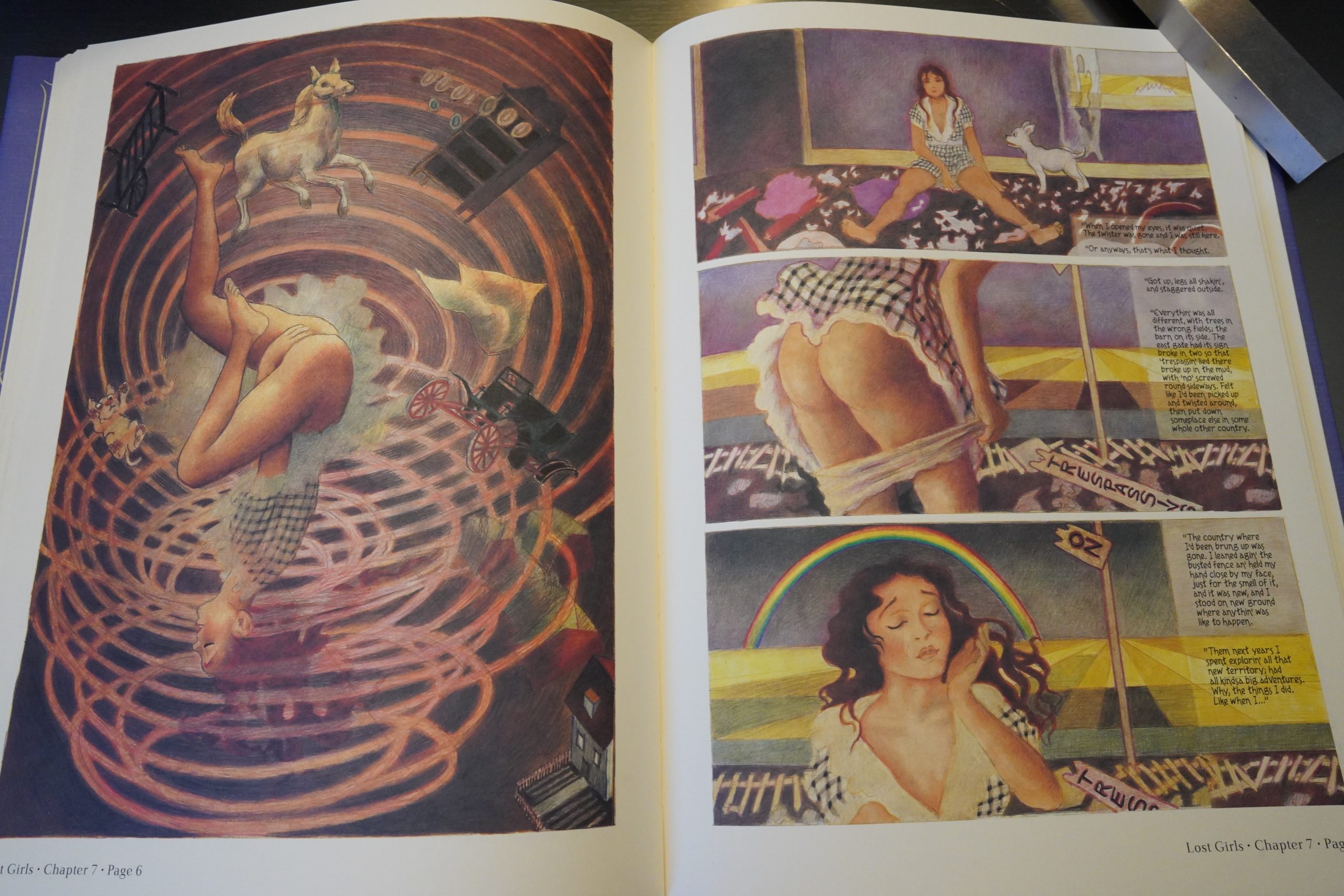

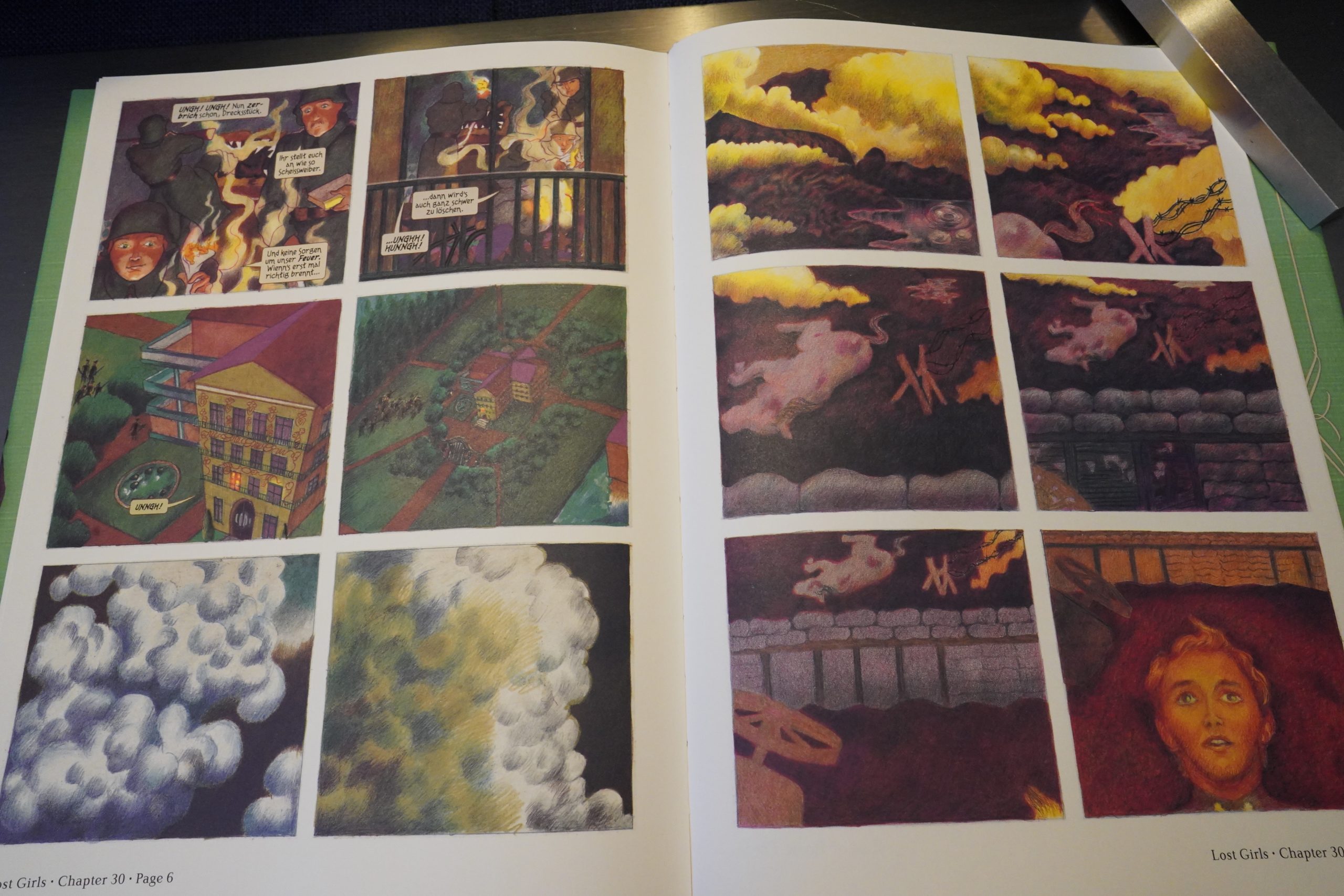

Sometimes this works eerily well — like, “yeah, I could see a hurricane being a pretty good metaphor for orgasm” — but sometimes it’s kinda strained, and the “reveals” (left page above) that tells the reader “IN CASE YOU DIDN”T GET IT< THAT BIT WAS ABOUT THE HURRICANE IN OZ", which feels pretty condescending. On the other hand, perhaps Gebbie just really wanted to draw those "reveal" pages. In which case I can't blame her, because they looks pretty great.

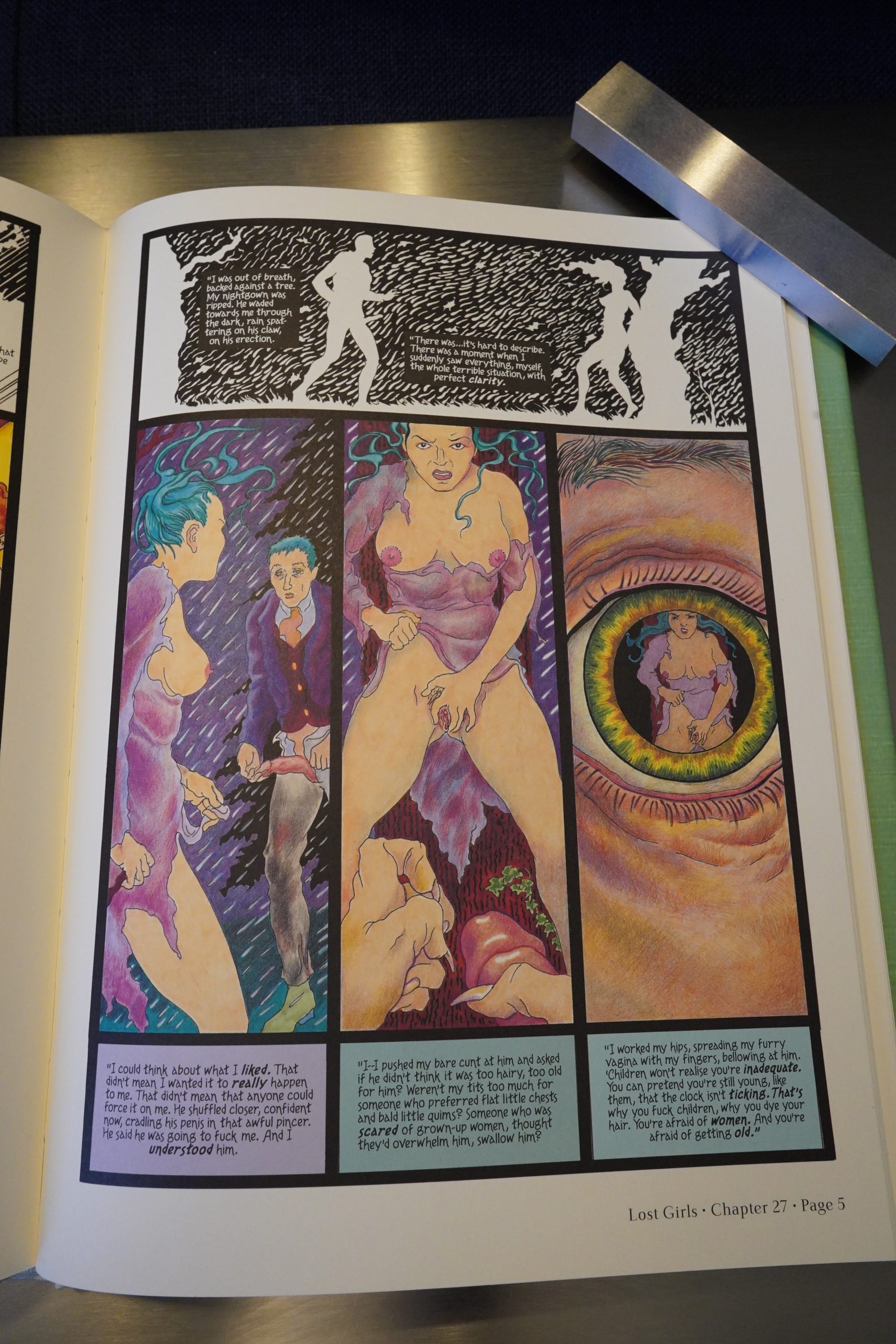

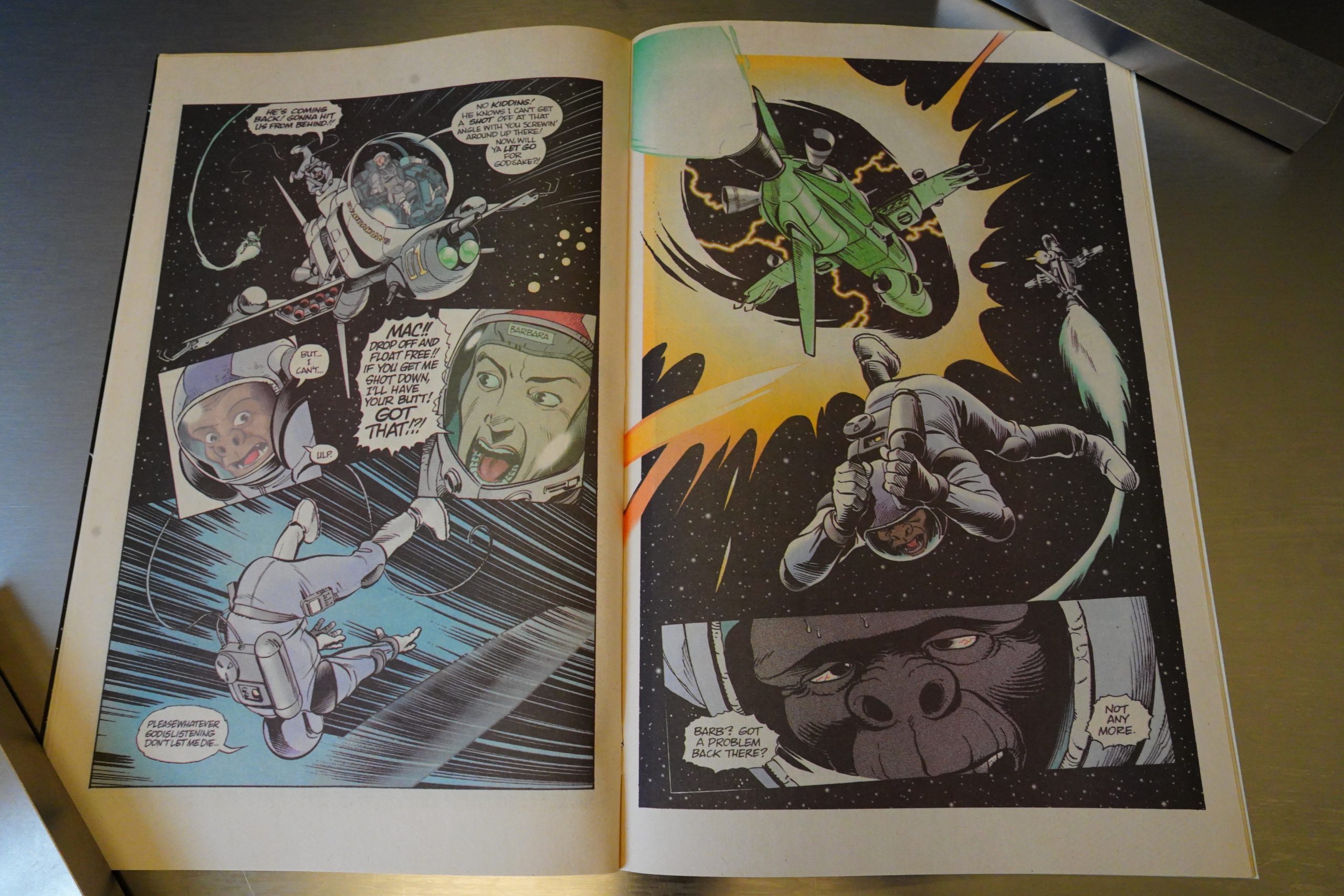

We basically get the three entire stories, but they’re told in an interleaved fashion, and usually with a distinct visual style to set the apart. So the Peter Pan bits are in this layout…

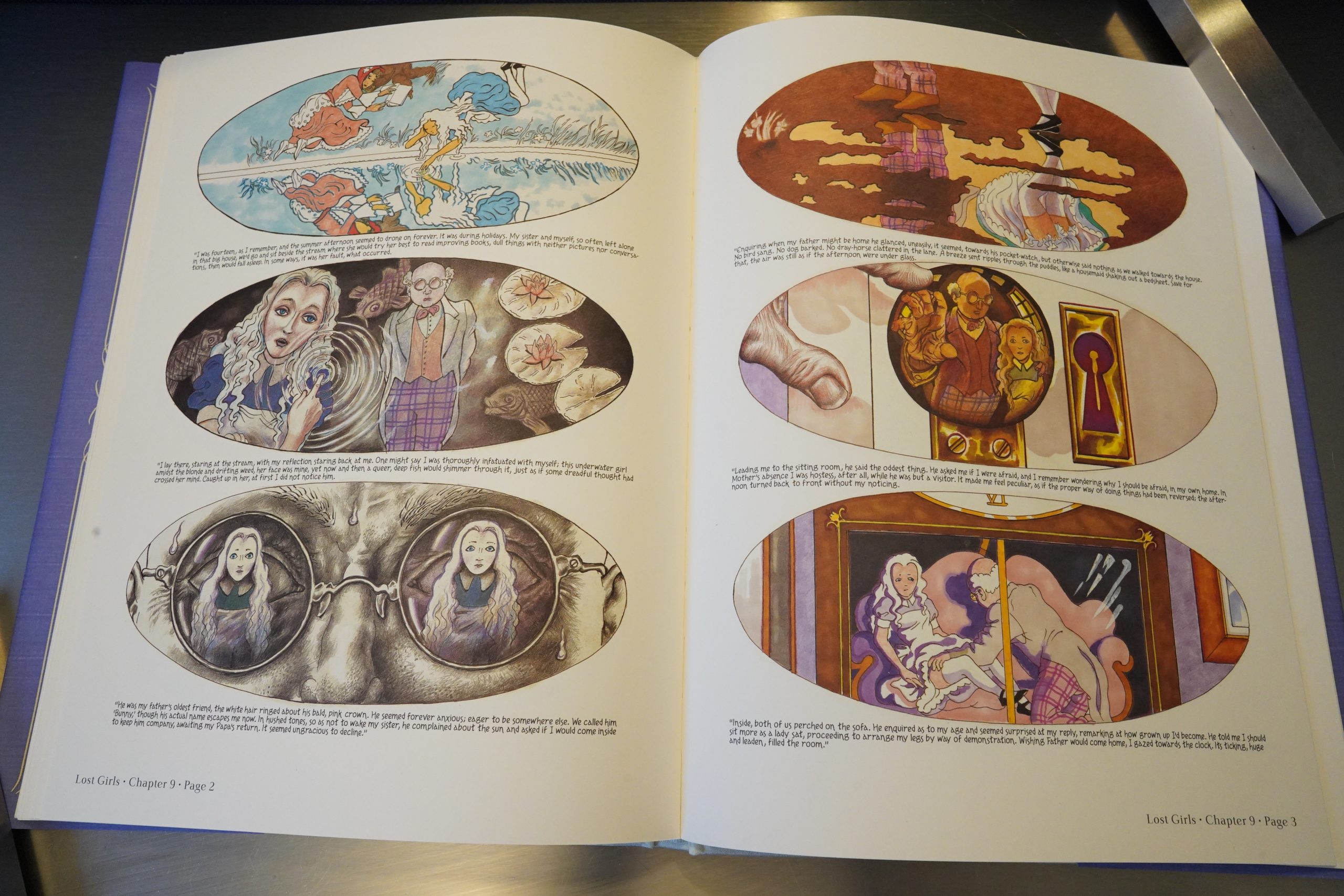

… and the Alice bits use this style.

While this is, mainly, a porn book, they bring in a lot of horrifying things, too. The book is constantly on the precipice of being a horror book, in some ways. And in other ways, it’s a pretty embarrassing book: Alice “origin story” is that she’s raped as a child by this prick, and she has an epiphany towards the end of the book that SPOILERS perhaps she’s a lesbian just because of that, and not because she’s into women.

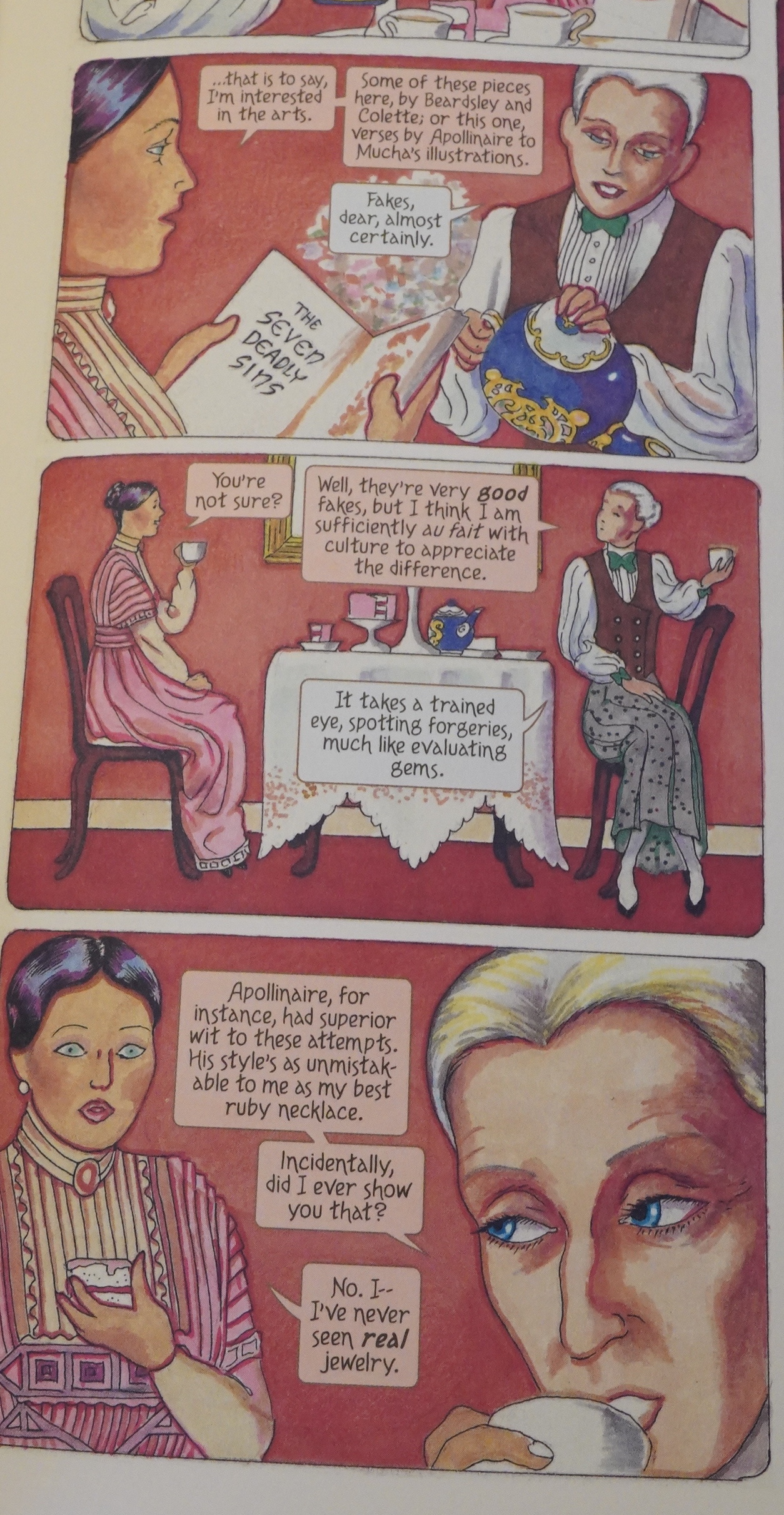

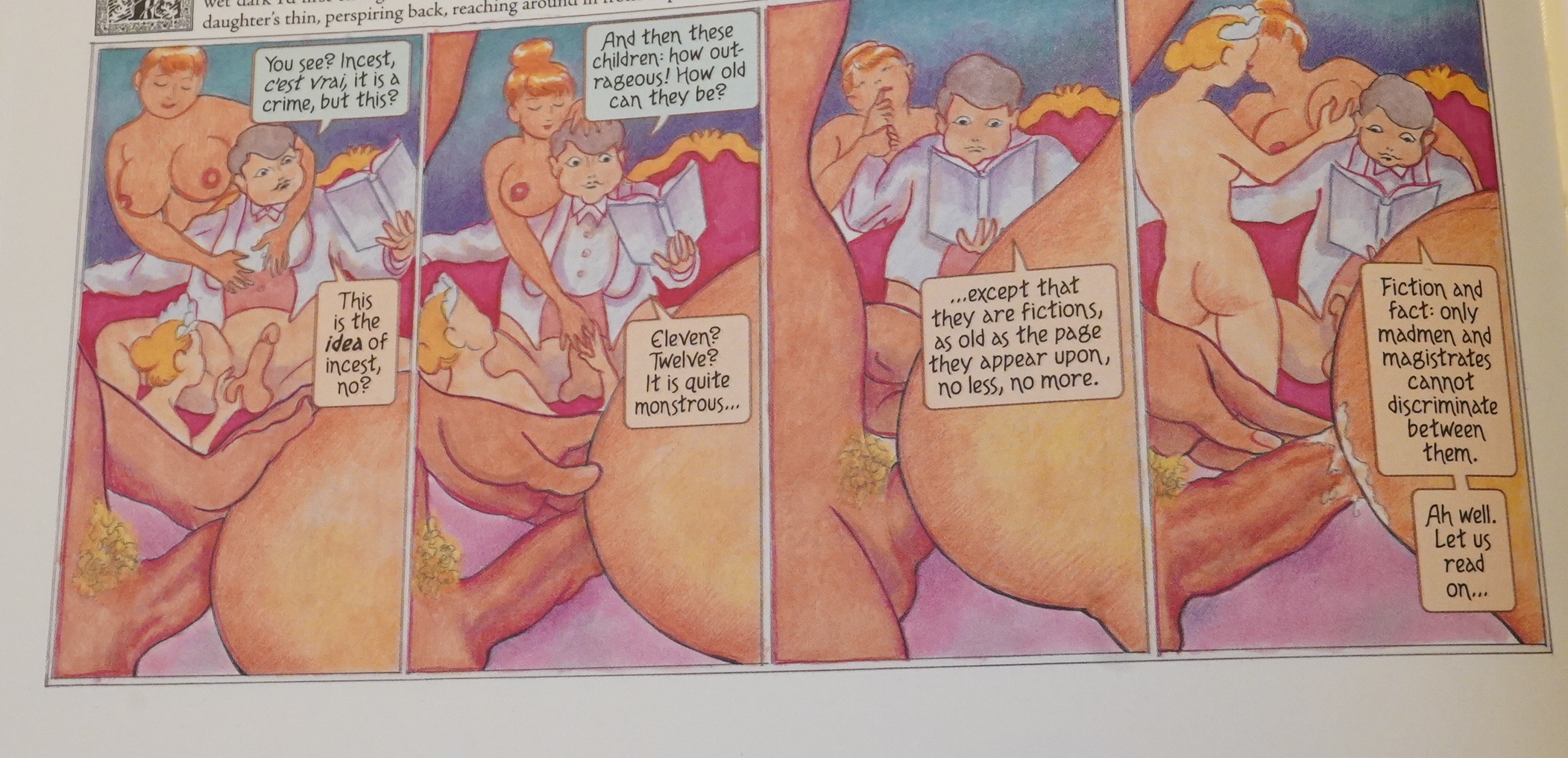

It’s very pomo, what with the main story itself being a skewed retelling of other stories, but there’s (of course) also a book in the book (isn’t there always?) that is of unclear provenance. It’s being presented as possibly being a collection of erotic texts from famous writers, but more likely a forgery, and Moore hedges by having a character giving a critique of the book. So he gives himself the appraisal that they are “very good” but obviously not as good as if they were actually real.

Which is smart! Because the bits from this book (excerpt on the right above) are pretty leaden. And it’s a common problem when writing something about finding books/art that’s supposed to be incredibly well done. How do you work around that? If you don’t include it, it feels like a cheat, and if you do, it better be really good, otherwise the whole thing becomes totally risible. Moore, smart as he is, tells us that the “lost book” isn’t that good up front. *slow clap*

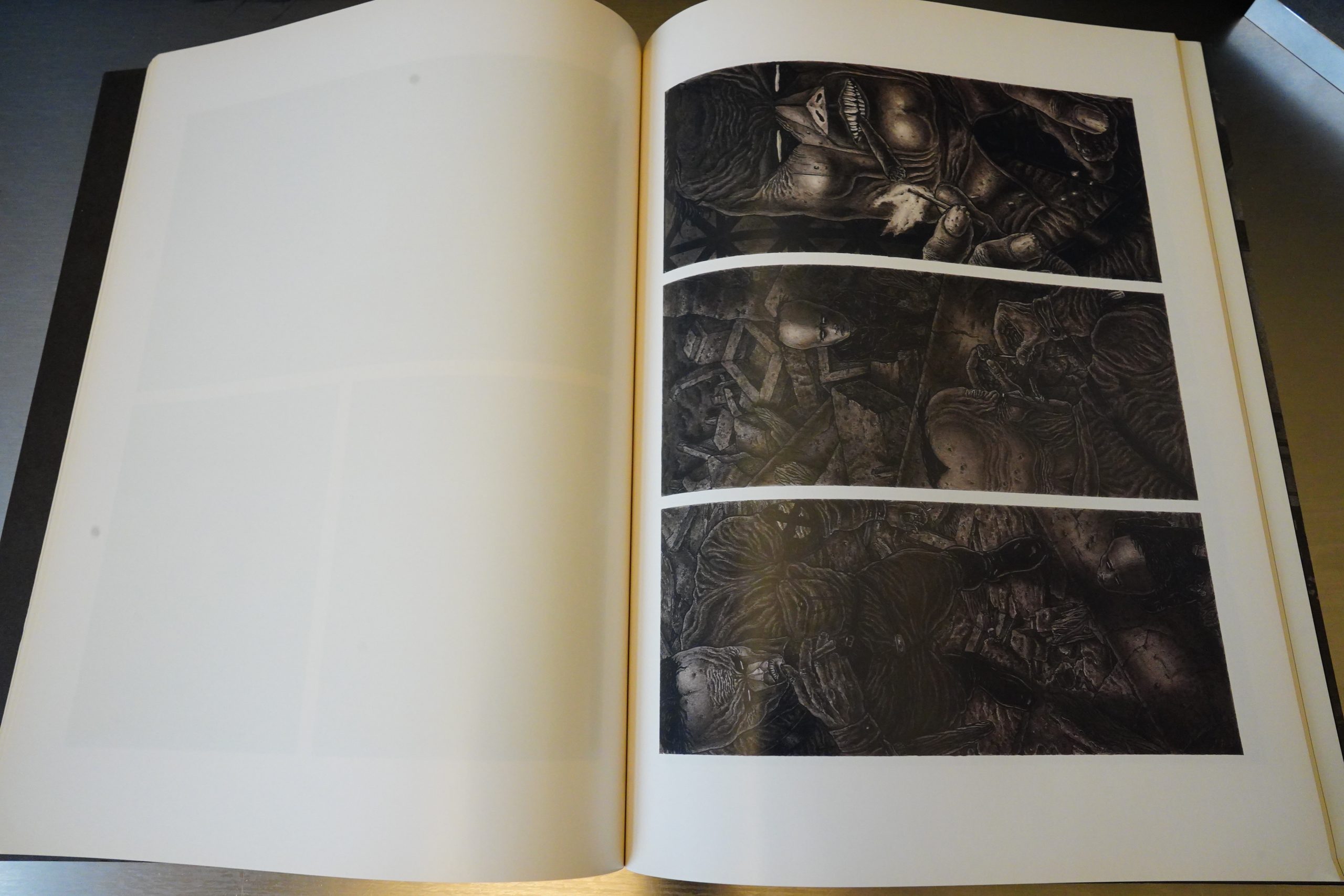

While I was in no hurry to re-read this book, I found myself enjoying it more than I expected. Gebbie’s artwork is fantastic, of course, but there’s more of a storyline than I remembered. In addition to the many stories within the story, the main setting isn’t static, either: World War I breaks out while they’re in the hotel, and war encroaches upon the third volume.

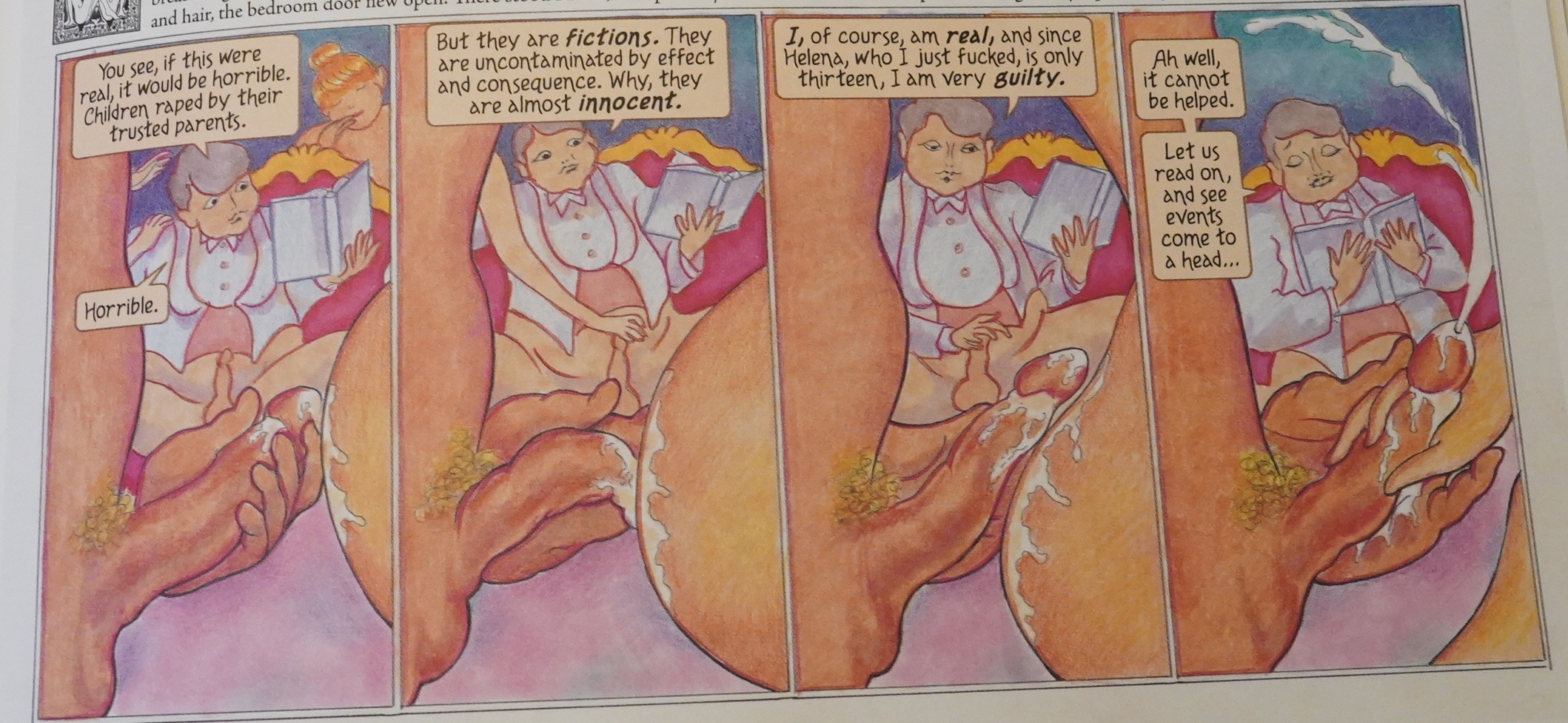

The main subject of the book is porn. Moore delivers an in-story defence of porn, which is the quite standard one…

… but then he complicates it. Oh, the layers.

The book isn’t just a series of vignettes, either — it gets gradually more and more unhinged, building up to a crescendo. It’s like the entire book is a metaphor for sex or something.

But there’s a lot of eye-roll inducing stuff here. Like Wendy unmanning a rapist by confronting him with some hard truths.

*gasp* By the working class!

And of course, the real obscenity is war.

I poke fun, but it is a good comic book. This book apparently took 15 years for Gebbie to draw, though, and I love the wilder, strange stuff she wrote herself, so I’d prefer myself she’d done more of that stuff instead. But that’s not how the markets work, so we’d probably have gotten a whole less stuff than these 240 pages, so…

IDW released an expanded version in 2019. It’s 350 pages — that’s more than a 100 pages more? I googled around to find what in those pages — sketches and interviews and essays and stuff, or a continuation of the story? I was unable to find anybody giving the dirt on the edition. INTERNET! WHY YOU SUCK!

The groundbreaking and controversial masterpiece of erotic comics, decades in the making, is now available in a sumptuous hardcover collecting all three volumes plus 32 pages of new artwork and commentary.

Well, that doesn’t help a lot. Hm… Oh, I guess the old version was more like 300 pages, not 240, because there’s a couple extra pages per eight issue story for titles and stuff.

Paul Tobin writes in The Comics Journal #184, page 53:

I APPROACHED Lost Girls with preg-

nant trepidation. It has been some time since

the name of Alan Moore has been asurefire sell

to me. Too many unfinished projects, blood-

soaked demons, shapely bad girls and untamed

felines have thrown a good deal of muck upon

the flame and tarnished the once shini ng bronze.

But since Lost Girls was a project which began

years ago, perhaps, I hoped, Moore’s muse was

still a potent one at that time. So when I picked

up Lost Girls it was with both cautious hands

and timorous hope for a book where either

character or story could anchor an ultimately

successful project. Unfortunately, even those

diffident hopes were almost immediately

dispatched. Ins,’ Girls, on any level, can Only

be considered a failure.

The basic plot of Lost Girls , by writer Alan

Moore and artist Melinda Gebbie, is the chance

meeting of three women in the opulent Hotel

Himmelgarten, located on the remote Austrian

border. The year is 1913. The three women are

the Lady Alice Fairchild, who has been ostra-

cized from her noble family due to her sexual

improprieties; Dottie Gale, an American girl

on vacation; and Mrs. Harold Potter, who is on

business vacation with her uninterested and

uninteresting husband. After the single intro-

duction of these women, sexual antics spas-

modically ensue between them and various

secondary characters. These liaisons occur

neither in story flow nor because of any actual

attraction between characters, but simply be-

cause this is supposed to be erotica, where such

things happen.

Of course, there is more to Last Girls than

this. Moore has never been the type of writer to

be content with simply telling a story. There

must be circles within circles — clues for the

astute (or at least the sighted) reader to pick up.

Presumably we are then supposed to marvel at

how wonderfully tricky a writer Moore is. In

actuality, though, these clues more often serve

as story breaks, actually tugging readers away

from the story. In Lost Girls, Moore is just a

two-bit magician, content with clichéd tricks

and obvious effects. Worse, we don’t simply

look at the created tricks, we are forced to gaze

upon the act of creating them itself. And once

the viewer is looking notat the trick, but instead

at the trapdoor on the bottom of the box, of the

magic is gone. In Lost Girls, the tricks which

dissolve what little magic there is are the women

themselves. Through various clues, Moore lets

the readers know that the women are grown up

versions of characters from famous children’s

books. The Lady Alice Fairchild is Alice of

Alice in Wonderland. Dottie Gale is Dorothy

from The Wizard ofOz and Mrs. Harold Potter

is Wendy of Peter Pan fame. The choice of

these characters seems to serve no purpose

other than Moore thought it would be neat

The Story Of these lost girls is told in chap-

ters. Chapters one through six were originally

presented within the pages of Taboo , but lwst

Girls volume one concerns itself with Only the

first three, with the first, entitled ‘The Mirror”,

focused upon Lady Fairchild.

In chapter one we see everything, in every

panel , through reflections in a mirror— through

the looking glass, if you will. The sex, the story

rHEC0.wcSJ0tJRNAL FIRING LINE ./84 FEBRUARY

and, above all, the Lady herself are presented as

very flat. Moore seems to believe that since his

own Alice is the familiar Can-oll character, the

character depth of the original is automatically

instilled within his new version. He’s simply

incorrect; not only that, it’s lazy writing. Add-

ing to the monstrous ennui of this chapter is the

mirror framing device, which becomes tedious

by panel six, at which point there are 42 more

panels of it to go.

Dottie Gale (aka Dorothy) arrives with an-

other “similar panel” motif, but soon merci-

fully abandons it. We first see her in a succes-

Sion of panels as nothing but legs wearing her

bright silver shoes. Dottie Gale is the typical

dumb American Midwestem girl usually pre-

sented in slacker literature. Despite her naivete,

within scant hours of her solo arrival she is

compliantly laying naked on the hotel’ s lawn as

Captain Rolf Bauer masturbates and ejaculates

upon her shoes. Her reaction to his apologetic

stammerings concerning his passions is a simple

“Ha Ha Ha. Well, I’m sure not in Kansas

anymore.” I saw the line coming, but still shud-

dered with its delivery.[…]

The stated goal of the projected 240 pages

Lost Girls is to create a work which rivals that

Of Crépax and other notables in the genre Of

erotica. Perhaps they’ve actually fooled them-

selves into believing they’ ve succeeded in this,

but, in reality, Moore and Gebbie have com-

bined to do little but sew colorful nude portraits

into the fabric of the emperor’ s new clothes.

I don’t think he liked it.

Craig Fisher writes in The Comics Journal #278, page 138:

Journal editor Michael Dean asked

me to participate in this critical round-

table on Alan Moore and Melinda Gebbie’s

Lost Girls, I was flattered, but also worried.

What if the Other critics had better things to

say about Lost Girls than me? so even before

reading the book, I began to think about

what hook I could give my review. I thought

itmightbe fun to write something playful and

unconventional — my inspiration was Darcy

Sullivan, who once “wrote” a review of Tom

Scioli’s ne Myth Of 8-0pus by assembling

quotes from Other writers — and I came up

With What I thought was a clever idea: I’d

frame the review like a 20-year love affair be-

tween Alan Moore and me. My opening sen-

tence could be “Alan and I started dating in

the summer Of ’83,” and then I’d segue into a

discussion Of how Moore treats sexuality in

his comics. I could even insert subsections

in the review with punny titles like “The

Anatomy Lesson” and “A Love Supreme.”

While I for the Lost Girls proofs to ar-

rive in the mail, I scanned through a stack of

Old Moore comics (even Deathblow Byblows,

which really blows), looking for phrases I

could twist into double entendres.

The proofs arrived, I read Lost Girls, and

I don’t feel like writing my review any more.

How come? One reason is that reading so

many Moore comics in a short period of time

made me realize how acute Moore’s decline

has been in the last 15 years. I still remember

the joy I felt when I bought the first issue of

Big Numbers: Moore was finally free Of DC,

finally free to pursue his obsessions (which,

back then, focused on Fibonacci numbers

rather than fictional snake gods) and write the

masterwork we all just knew he had in him.

After his publishing company Mad Love fell

apart, however, Moore walked a tightrope

between corporate comics (scripting for

— sigh — Rob Liefeld’ s Maximum and Awe-

some imprints) and more personal, alterna-

tive projects. The personal stuff, like From

Hell, ne Birth Caul and Snakes and Ladders

(all drawn by Eddie Campbell), holds up

well, although sections of all of these books

are mind-numbingly ovenvritten, a tendency

in Moore’s work that resurfaces in Lost Girls.

I also liked Supreme’s evocation Of Weis-

inger-era Superman comics. But America’s

Best Comics were, for me, anything but. Tom

Strong started out, well, strong, then quickly

spoiled; I always thought Top Ten was over-

rated: and I found Tomorrow Stories so lousy

that I actually stopped buying it after issue

five, unthinkable for someone who’d previ-

ously gotten headaches from the anticipation

he’d felt waiting for the next issue of Watch-

men. (The exception to my blanket dismissal

of ABC is Promethea, which I still like for its

wonky mysticism and extraordinary final is-

sue.) To write the “dating Alan” review, then,

I’d have to acknowledge that our relation-

ship wasn t by-making-love-i n-

the-forest-while-ingesting-psilocybin” any

more. In fact, these days it feels more like a

fatal tryst between Mr. Hyde and the Invis-

ible Man.

The other reason I abandoned my clever

review was my lack of enthusiasm for Lost

Girls itself: It feels like nothing more than

a retread of Moore’s older, more distin-

guished work. Let’s 100k, for instance, at the

structure of Lost Girls. The first five chapters

of the book introduce Lady Fairchild (the

grown-up Alice from Alice in Wonderland),

an adult Dorothy Gale from The Wizard of

Oz, and Wendy from Peter Pan, who’s now

caught in a loveless marriage with a ship

manufacturer. The three women meet at the

Hotel Himmelgarten, an Austrian establish-

ment run by the effete Monsieur Rougeur.

In Chapter 6, “Queens Together,” Alice

and Dorothy stroll off into the forest sur-

rounding the Himmelgarten and just begin

to settle into a comfortable 69 (“Y,/e must re-

semble people on a playing card,” says Alice,

who’d know) when they realize that Wendy

is watching this beast With two backs. After a

brief confrontation, Alice and Dorothy make

friends with Wendy, and the chapter ends

With Alice suggesting that the three women

“devote this afternoon to storytelling.”

From this point on, the narration Of Lost

Girlsrigidly alternates between past and pres-

ent The past events are the stories the wom-

en tell to each other, pornographic takes on

Wonderland, oz and peter pan. In Chapter

7, for instance, Dorothy describes how she

masturbated and reached orgasm for the first

time While a twister ripped apart her Kansas

farm. In contrast, the events that unfold in

present-time in Lost Girls show the decline

of traditional Europe circa 1913-14 — Chap-

ter 10 chronicles the riot accompanying the

premiere of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, while

in Chapter 20 the Archiduke Ferdinand gets

plugged —

or present the Himmelgarten

as a safe, sexy space briefly protected from

Europe’s collapse. (Moore’s Himmelgarten

is a direct nod to the Chateau de Silling, the

castle retreat occupied by libertines

ing the Thirty Years’ in the Marquis de

Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom.) The Top Shelf

edition of Lost Girls divides into three hard-

cover volumes of 10 chapters each, and be-

low I’ve listed how the balance between past

stories and present events plays out in each

volume. (Anyone allergic to spoilers should

skip this list.)[…]

This list makes one point clear: Lost Girls

follows an amazingly schematic Structure,

With the subject matter Of each chapter

termined as much by its place in that

ture as by the organic unfolding of the story.

In other words: Lost Girls is Watchmen, but

with lots more fucking. Six of the chapters of

Watchmen (2, 4, 6, 7 , 9 and 1 r) present us with

the story’s past; they reveal the origins Of spe-

cific heroes, and narrate the histories Of the

Minutemen and the stillborn Crimebusters.

The alternating chapters (1, 3, 5, 8, 10 and 12)

chart present-day events in the fictionalized

Watchmen world, including Rorschach’s

hunt for the Comedian’s murderer, and es-

calating nuclear gamesmanship between the

and the USSR. In a similar fashion, each

of the three volumes of Lost Girls sandwiches

stories from the past (the erotic “origins” of

Alice, Dorothy and Wendy) between pres-

ent-day chapters that chronicle apocalyptic

events (the assassination of Archduke Ferdi-

nand and the beginning of WWI).

Given that Moore has spent much of the

last decade either assembling Leagues of Ap-

propriated Characters Or “inventing” slight

variations on copyright-protected ones like

Superman and Wonder Woman, it was na-

ive Of me to expect too much originality from

the structure of Lost Girls. But the problem is

more than structural; it extends to the book’s

subject matter, where Moore’s desire to re-

write Wonderland, Oz and Peter Pan leads

to crushing boredom. Dorothy’s first flash-

back, for instance, is presented in Chapter

7, with her she-bop during the tornado. She

continues her tale in Chapter 14, “The Straw

Man,” where she seduces a farmhand with

“no thoughts an’ no imagination” and, in the

process, encourages him to develop a brain.

After I read this chapter, I was ready to throw

myself at Moore and beg, “No, no, Alan!

Please don’t make Dorothy fuck the Cow-

ardly Lion and the Tin Man and the Wizard

too! I’Vouldn’t it be wacky if she got it on with

a milkman or traveling salesman completely

unrelated to the Oz characters?” But Alan

wasn’t feeling wacky When he wrote Lost

Girls, and by halfway through volume two

I could roughly guess what was going to ocv

cur in the rest of the flashbacks. Predictable

structure, predictable subject matter read-

ing Lost Girls became a grind, entirely bereft

of thefnn I ‘d expect from either good porn or

Moore at the top of his game.[…]

A persistent rumor among alt-comics fans is

that Top Shelf needs to sell a lot of copies Of

Lost Girls, or the company will go bankrupt.

While I wish Top Shelf all the best, Lost Girls

is, alas, empty and unoriginal, and Moore

has become the Straw Man, leaving comics

none too soon and many years too late.

Sorry for quoting at length, but I thought that was a pretty good review.

Tom Crippen writes in The Comics Journal #278, page 141:

“HEY-YOH!”

If you couldn’t write a masterpiece, then

probably you couldn’t write Lost Girls ei-

ther. Still, the book is no masterpiece. Alan

Moore reports that one time he spent a

couple of weeks believing that cherubs were

the most important thing in the universe and

next his hallway was painted solid with cher-

ubS and he couldn’t figure out why he ever

wanted them there. Lost Girls is a bit like that

— kind of a wrong turn.

As genres go, pornography makes super-

hero comics 100k good. Both are builtaround

spasms of activity that apparently can’t be

left out of the action. You have to have fight

scenes, you have to have sex scenes. But at

least the fight scenes come with some mo-

tivation. The man wants to rob the jewelry

store, or the man is mad because he was im-

prisoned in the Parallax Zone. The maid who

jumps the bellboy in Book II of Lost Girls

doesn’t have a particular reason to do so. He

has less reason to take part, since he already

came a couple of minutes ago during some

fooling around With a third party. But they

go ahead anyway. Getting through Lost Girls

is like reading three volumes about people

who eat fried chicken and don’t care about

anything else. NO matter what, they’re going

to eat fried chicken, and they’re going to do it

With a chummy Rotarian air that sounds like

nothing on earth: ” My prick, he would think

Of it as an honour, Madame,” nrvlonsieur

Rougeur’s narrations and his member are

both very nice indeed.”

You have heard there’s shocking stuff

in Lost Girls: pedophilia and bestiality and

incest. Indeed there is, plenty. From inter-

views, it appears Moore conscientiously de-

cided to carry the exercise to the limit. If he

was going to do pornography, he was going

to do real pornography, not some polite liter-

ary substitute. Of course Moore believes in

consciousness-expanding everything, so he

believes in consciousness-expanding porn.

Apparently, real porn is supposed to be

transgressive” and set loose fantasies that

can never be acted upon, fantasies from the

core Of our being. TO know ourselves is to

know them too.

You start out with freeing the psyche and

you wind up with a girl jerking Off a horse.[…]

Melinda Gebbie’s art is hard to size up

because the book was sent to reviewers as

a set of black-and-white photocopies. She

drew most Of the pages with layers of col-

ored pencil; from what I remember of the

few chapters issued by Kitchen Sink years

ago, the effect is beautiful and gives the work

a lot of its body. Of course, black and white

doesn’t keep her Aubrey Beardsley pastiche

from coming through, and it’s lovely. Per-

haps best of all, Lost Girls’ panel sequenc-

ing shows Moore hasn’t lost his juggling

arm. If you want to see chapters told entirely

through reflections in a mirror on a dresser,

or see fully-clothed characters unwittingly

produce a sex scene by means of their shad-

ows, or watch many small moving bits of

plot, language, and symbol chime together

like a three-volume cuckoo clock, then Lost

Girls won’t entirely disappoint you. Alan

Moore can’t help being brilliant. It’s just that

here he’s ridiculous.

Michael Dean writes in The Comics Journal #281, page 31:

IN DEFENSE OF LOST GIRLS

by Michael Dean

If ever a book needed no defense, it is Alan

Moore and Melinda Gebbie’s Lost Girls,

which has been praised by critics and attend-

ed to by commentators and reporters from

every corner of the Internet to the most main-

stream of print, radio and television cover-

age. Print runs ofits $75 deluxe three-volume

sets have sold out again and again, allowing

Top Shelf a major sigh of relief at the success

of its gamble. Partly to guard against falling

into lockstep praise of the book and partly

because virtually all the Journal’s contribu-

tors wanted to review the book, I assigned

it to not one, but three critics. Since they

were regular reviewers for the Journal (Noah

Berlatsky, Craig Fischer and Tom Crippen),

I probably shouldn’t have been surprised

when each critic, one after the other, gave the

book thumbs down — each writer proudly

carrying on the Journal’s contrarian, icono-

clastic tradition by refusing to give Lost Girls

the free pass that every other critic would pre-

sumably give it. The result was that instead of

the Point-Counterpoint effect I had been

aiming for, we ended up with a sort of Coun-

terpoint-Counterpoint-Counterpoint

Under the circumstances, I imagine Lost

Girls artist Melinda Gebbie was a little puz-

zled to have her work included in theJournars

Best of 2006 a mere three issues after it had

been panned by a sizable percentage of the

Journal’s pool of critics. To Gebbie, it began

to look less like an honor than an ambush,

and she hesitated to give us her corrections

for the interview that appears on page 56.

The question that arises has two faces:

If Lost Girls is one of the best comics works

of 2006, then why did it get nothing but bad

rewie”.vs in theJournal, and conversely, if the

book struck out with three Journal critics,

why is it now being celebrated by the maga-

zine as one Of the best Of the year?

I’m not going to give the book a fourth

— more positive — review here. (Non-Jour-

nal-regular Kristian Williams provides that

on page 34.) Nor am I going to try to analyze

the book, because a close reading of its many

layers and themes would take more space

than this issue can spare. Instead, I’m aiming

to read the readings of the book, in order to

reflect on what has been at stake in the vari-

ous critical responses to Girls, especially

in the pages Of the Journal.

In a way, it’s easy to explain how the

same work could be panned and praised in

the Journal: The magazine is not monolithic.

Gebbie’s interview appears in this issue,

because I think Lost Girls is one of the best

works of the year, but my opinions don’t

always coincide with publisher/editor Gary

Groth’s opinions, let alone those of all the

rewiewers.Journal critics are assigned books

to revien.v because they have proven that they

can write about comics articulately, insight-

fully, and sometimes provocatively. I have

no way of knowing whether they will review

a book favorably or disparagingly.

Nevertheless, I think the three negative

critiques of Lost Girls are consistent with a

particular unified aesthetic, a set of cultural

attitudes that have been a growing presence

in the Journal and in the alt-comics commu-

nit}’ it serves. Berlatsky, Fischer and Crippen

each elucidated his own individual take on

Moore and Gebbie’s work, but it’s not hard

to identify the book’s most prominent de-

feet as seen through all three pairs of critical

eyes: Revered author Alan Moore was again

and again (and again) charged with being

the creative team’s weak link and accused of

devising a narrative that was too stultifyingly

schematic and at the same time painfully

obvious in its symbolism and overly lush

language. Feedback from Journal readers in-

dicated more agreement With the critics than

disagreement, though one noted that three

negative reviews seemed a little like overkill.

Wow, there was a lot of stuff in the Comics Journal about Lost Girls at the time…

Noah Berlatsky writes in The Comics Journal #278, page 143:

ACCEPTING PORN AS

YOUR PERSONAL SAVIORThis is a work of pornography — not

erotica — which also presents itself as a

work Of art. The graphic style is gorgeous and

distinctive, the characters have individual

personalities, and their relationships are re-

spectfully and realistically explored in a way

designed to appeal to women as well as men.

The sex is violent, complicated, straight, gay,

sadistic, very occasionally vanilla, and woven

seamlessly into the storyline. I’m talking, of

course, about Michael Manning’s Spider-

garden series.

All right, it’s my little joke — I’m review-

ing Lost Girls, just like everybody else. But

one of the things that has annoyed me about

the hype surrounding Alan Moore and

Melinda Gebbie’s book is the suggestion

— promu Igated by both authors and review-

ers — that our cultu1T is somehow starved

for aesthetically pleasing, intellectually seri-

ous stroke material. Granted, there is a lot

of crappy porn out there — but then, there

is an almost unlimited quantity of every kind

of porn out there. Underage porn? Sure.

porn with people dressed up in bunny suits?

Check. Porn created by surprisingly clever

people with humor, insight, wit and taste?

Yes, indeed, grasshopper, for the Internet is

vast, and most of it is devoted to smut. (For

one example of well-written, thoughtful and

very funny porn, check out EyeofSerpent’s

storiesonwum’.mcstories.com.) Even the use

Of pre-existing characters in compromising

positions has become common — though,

to be fair, slash fiction is fairly uncommon

in comics form, and it was, in any case, a lot

less high-profile when Moore and Gebbie

first decided to, er, fool around with Wendy,

Dorothy and Alice 15years ago. (Ifyou’re not

in the know, slash fiction is a type Of porno-

graphic fan fiction devoted to homosexual

relationships. For example, a slash story

might feature sex between Star Trews Kirk

and Spock, or between Frodo and Sam from

Lord of the Rings. Slash is overwhelmingly

written and read by heterosexual women.)

Don’t get me wrong. I liked a lot ofthings

about Lost Girls, even if it doesn’t exactly re-

invent porn as we know iL It’s an ambitious

and Often bizarre undertaking, produced

with obvious care. Moore’s decision to refer

to it as pornography rather than erotica is

admirable, and it is refreshing to see a book

with this kind of aesthetic caché and market-

ing budget present itself so directly as an aid

to orgasm, complete with contortionist sex

positions, multiple partners, full-frontal ev-

erything, and even the occasional gratuitous

slurping. In that vein, and purely as porn, it

worked for me in the utili tarian way that such

things do — there were scenes I found stimu-

lating, they occurred with relative frequency,

and the action that happened in the intervals

wasn’t so off-putting that it killed the mood.

I found the adult Wendy’s progress from

buttoned-up, repressed Victorian hausfrau

to insatiable, big-bosomed tart particularly

scorching. (Which means, I suppose, that,

like Alan Moore, I enjoy the idea of fucking

with the bourgeoisie.)

Despite its pleasures, though, there

are some serious problems with the book.

Moore and Gebbie clearly have an encyclo-

pedic knowledge of Edwardian smut, but

they have some trouble translating that into

formal mastery. Gebbie’s artwork is hard to

evaluate in the black-and-white photocopies

we were sent for review, but the color panels

I have seen are underwhelming. I admire her

ambition, and I’m all for ravishing confec-

tionary art, but Gebbie just doesn’t have the

chops to pull it off. Her drafting isn’t strong

enough to render anatomy convincingly ; nor

is it stylized enough to make up for the defi-

ciency. Her color sense is erratic — some of

the panels really work, but others are garish

and even ugly. Her designs and layouts are

0K, but hardly arresting. When Moore’s

script calls for her to mimic the styles of art-

ists like Aubrey Beardsley or John Tenniel,

her limitations become painfully obvious.

Like the art, the plot and writing both

creak audibly. Moore has always been a

heavy-handed writer, but in books like Halo

Jones and Watchmen, he had such a thorough

grasp on the genre material that it didn’t mat-

ter. At his best, even his clumsiness takes on

meaning, irony and resonance — the pirate

sequence in Watchman, for example, is both

ridiculously over the top and cool as hell, just

like the pulp masterpieces it draws on.

There are great moments in Lost Girls,

too: I love the scene where Wendy says good-

bye to her husband from an upper-story win-

dow; he thinks she’s wailing in despair at his

departure, when actually a bellhop is fuck-

ing her from behind. In general, though,

throughout the book, Moore seems ever so

slightly — well, lost The idea of sexualizing

famous children’s stories is a good one: I

certainly found the transformations in the

Alice tales weirdly erotic when I was a kid.

Moore’s follow-through, however, is only

sporadically successful. The Jabberwocky

as a giant penis is funny —

but it’s ruined

when Moore has to tell us that it’s going to

jab Alice. Dorothy masturbating while the

tornado hits is 0K; the labored metaphors

that transform her subsequent lovers into

the scarecrow, lion, and tin woodsman, on

the other hand, wander dangerously close

to the earnest pretension of literary fiction.

In fact, much of Dorothy’s dialogue sounds

like it was written in a college creative-writ-

ing workshop by a Reynolds price wannabe.

One colorful, earthy metaphor per page is

plenty, thank you very much.[…]

Perhaps Moore’s most focused discus-

Sion Of the damaging possibilities Of erotic

narratives involves Wendy. After fantasizing

about sex with a dangerous child molester

(Captain Hook), she semi-unconsciously

seeks him out, and is almost killed as a result.

In Faulkner’s novels, this sort Of collabora-

tion between victimizer and victim is a recur-

ring theme, and is used to raise questions

about how our dreams, identities and des-

tinies are attached to cultural expectations

that we often can’t control, even when we

recognize them. Led to the brink of such a

depressing insight, Moore backpedals fran-

tically, assuring us that Wendy’s real nemesis

is not her fantasy, per se, but rather her mis-

guided feeling Of responsibility for it This

is a big fat cop-out, and the immediately fol-

lowing scene, wherein Wendy scares off the

rapist by thrusting her cunt at him, was for

me the least convincing in the whole book,

and perhaps the only one that felt genuinely

exploitative.

This failure of nerve is emblematic of the

book as a whole. Moore and Gebbie make

extravagant claims for pornography, but

(or perhaps because) they don’t really seem

to have faith in the genre. Do readers really

need to be constantly assured that the-fre

fighting The Man and/or finding themselves

in order for it to be 0K to read a book with

explicit sex in it? porn has some ugly

tions, but so do most genres and mediums,

from the police State paranoia Of superhe-

roes, to the militarism Of science fiction, to

the casual disregard Of life in mystery novels.

to, for that matter, the gushy disempower-

ment of romance. It would be a surprise if

genre conventions weren’t bound up with

such implications, considering that all are

part and parcel of a reality, which is, after all,

imperfect. Despite what some critics of porn

might tell you, that’s not a reason to Stop

imagining (as if such a thing were possible),

or to endorse censorship, or even to wallow

in guilt. But it is something to think about

before you ram a dildo up your ass and

it freedom.

Non-comics media seem to like the book:

In fact, as the shadow of war engulfs the Himmelgarten, Lost Girls reveals itself to be an elegy for lost innocence. Rougeur and his increasingly vulnerable guests demonstrate that they are only too well aware of the difference between pornography and reality. “Fiction and fact: only madmen and magistrates cannot discriminate between them,” he says, before disappearing into the night. Lost Girls, despite its sometimes over-explicit philosophising, is ultimately a humane and seductive defence of the inviolable right to dream.

See?

Lost Girls is a bittersweet, beautiful, exhaustive, problematic, occasionally exhausting work. It succeeded for me wonderfully as a true graphic novel. If it failed for me, it was as smut. The book, at least in large black-and-white photocopy form, was not a one-handed read. It was too heady and strange to appreciate or to experience on a visceral level. (Your mileage may vary; porn is, after all, personal.)

I have also overlooked an interesting point Neil Gaiman raised in a recent review of Lost Girls (Neil suggested you read the book slowly, taking a break between each of the chapters to let the story settle – and he has a good point, it can be overwhelming particularly by the time you reach the third volume.)

This is the one hundred and ninety-first post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.