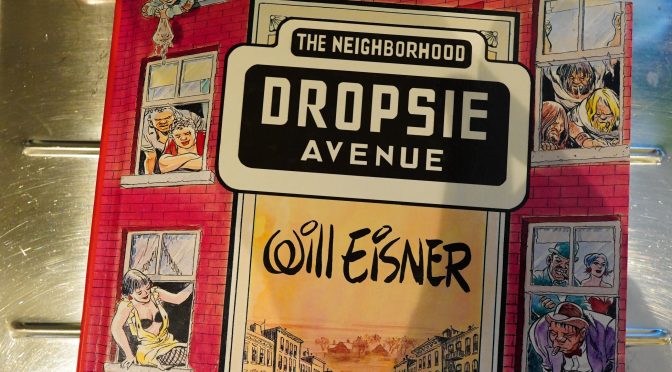

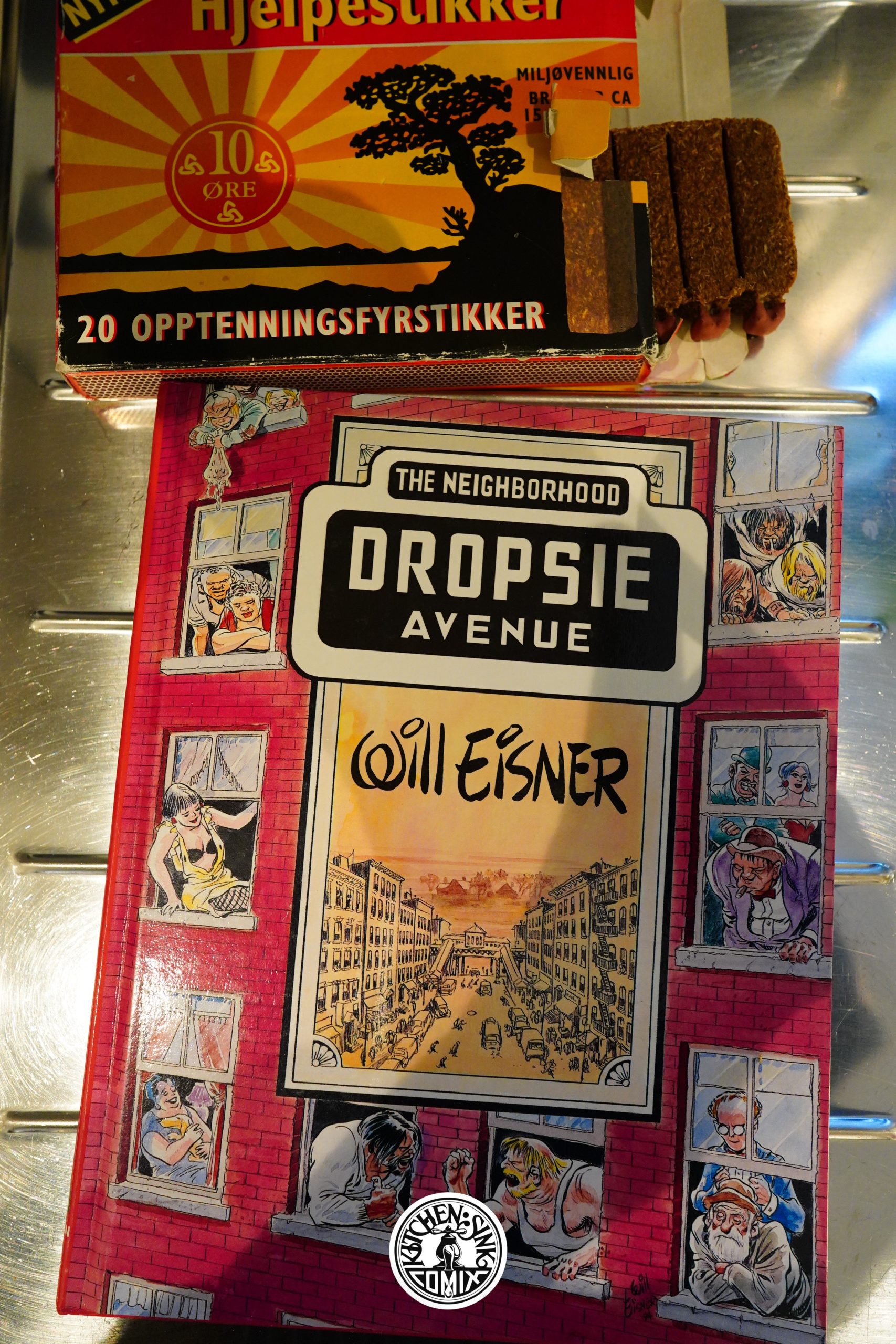

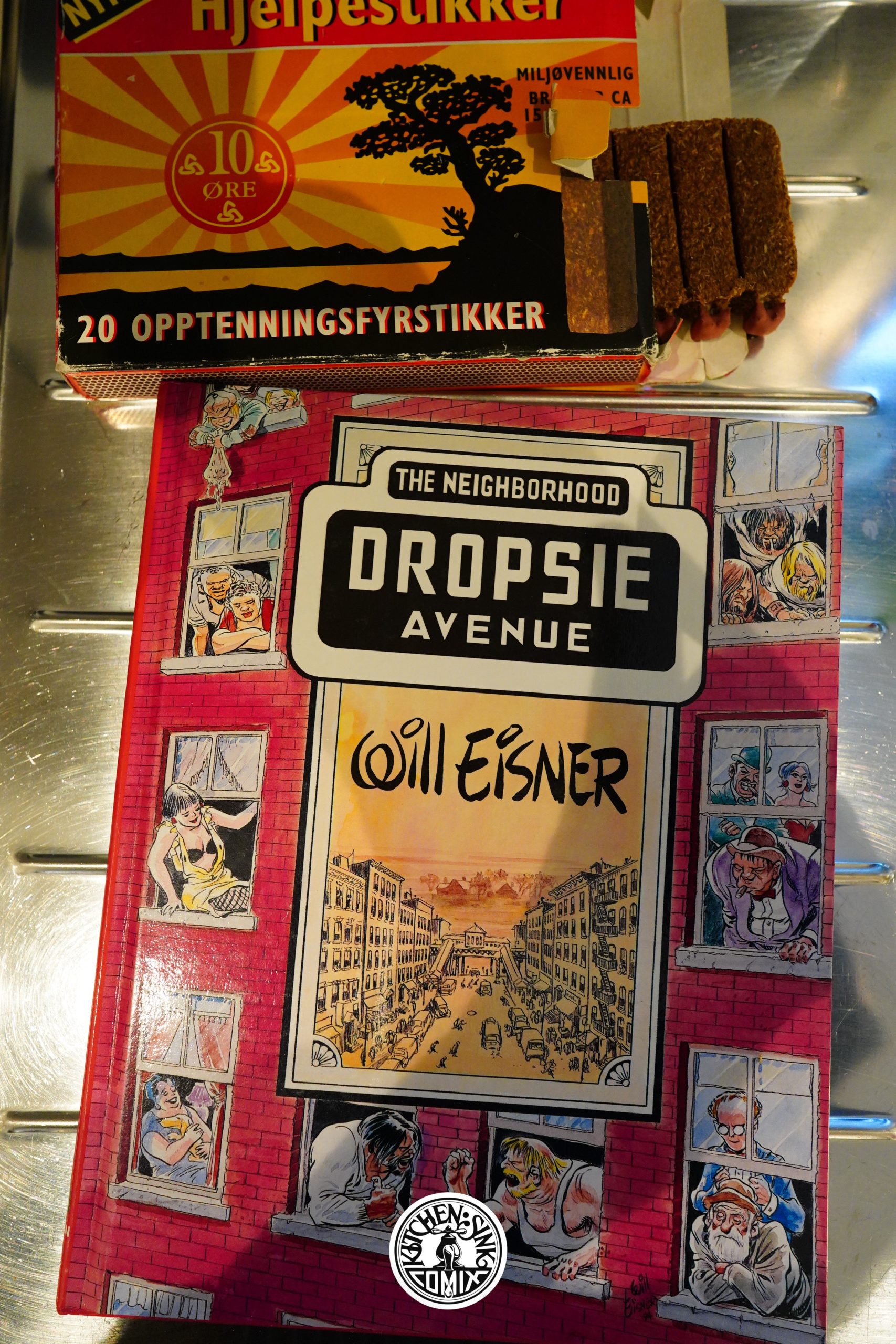

Dropsie Avenue: The Neighborhood (1995) by Will Eisner

Eisner returns to Dropsie Avenue, the fictional equivalent of the neighbourhood he grew up in, but this time he tells the full history of the neighbourhood, starting from when it was farm country. But… hasn’t he already done this? I seem to remember a shorter piece with the same premise? So this is an expanded version of that.

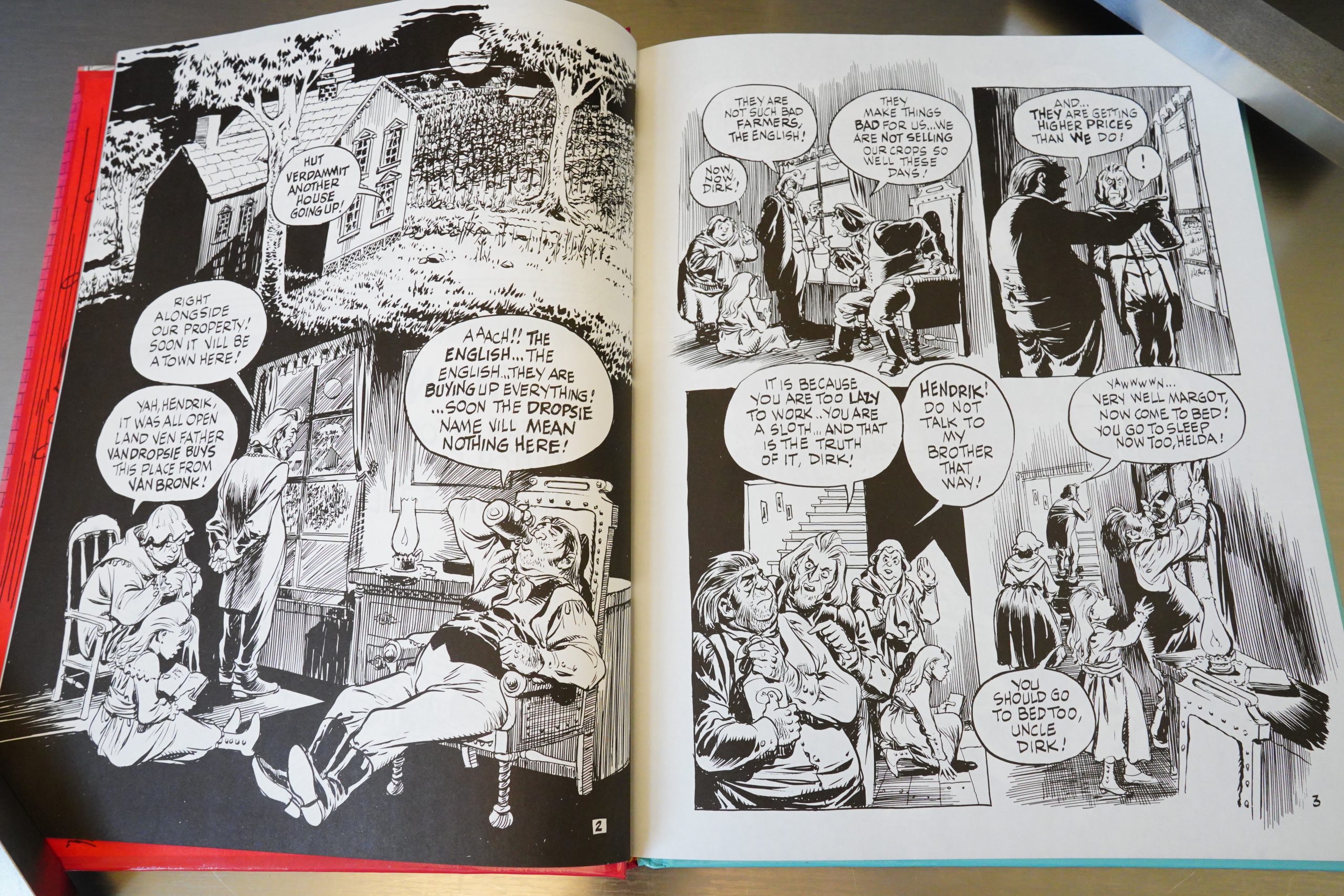

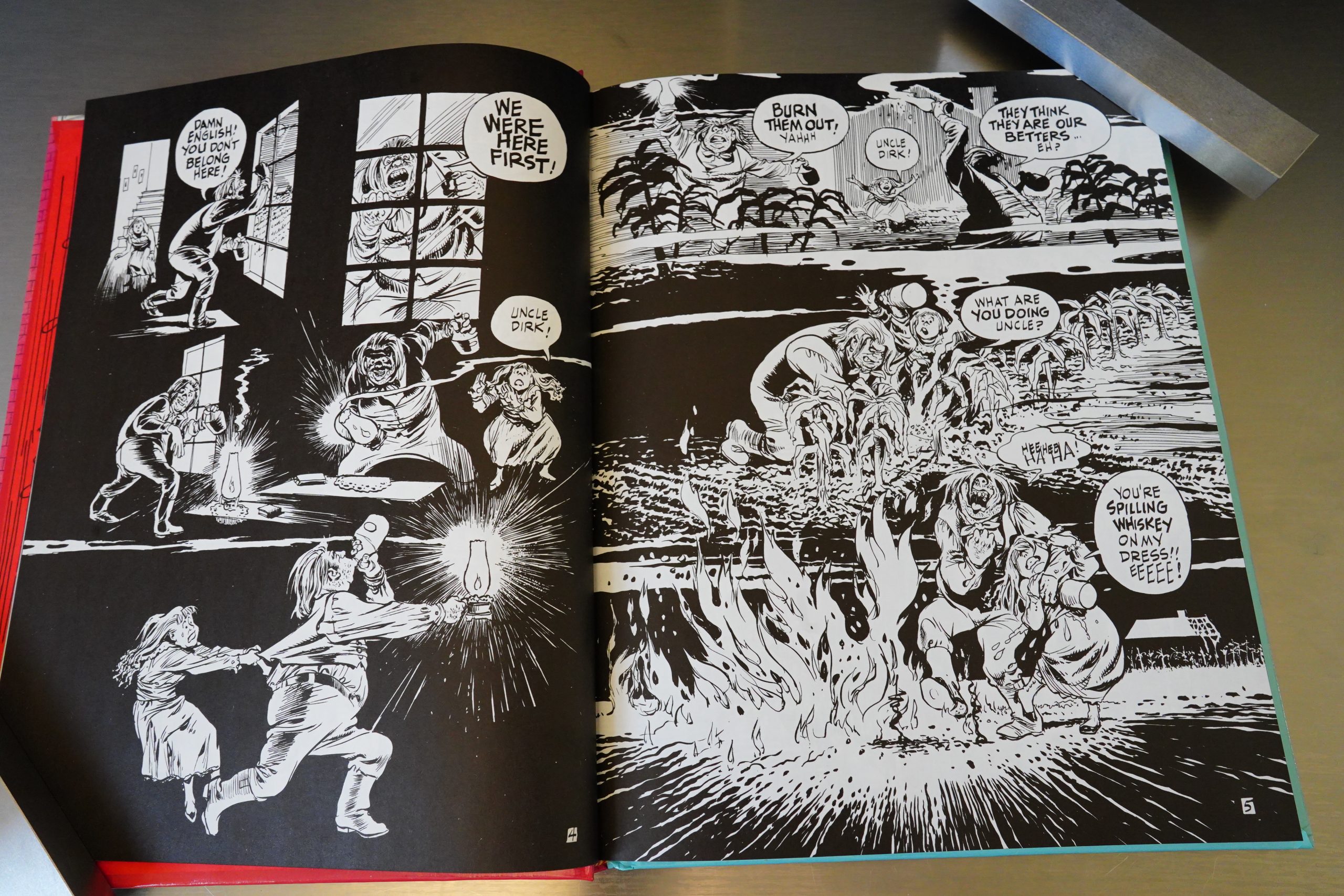

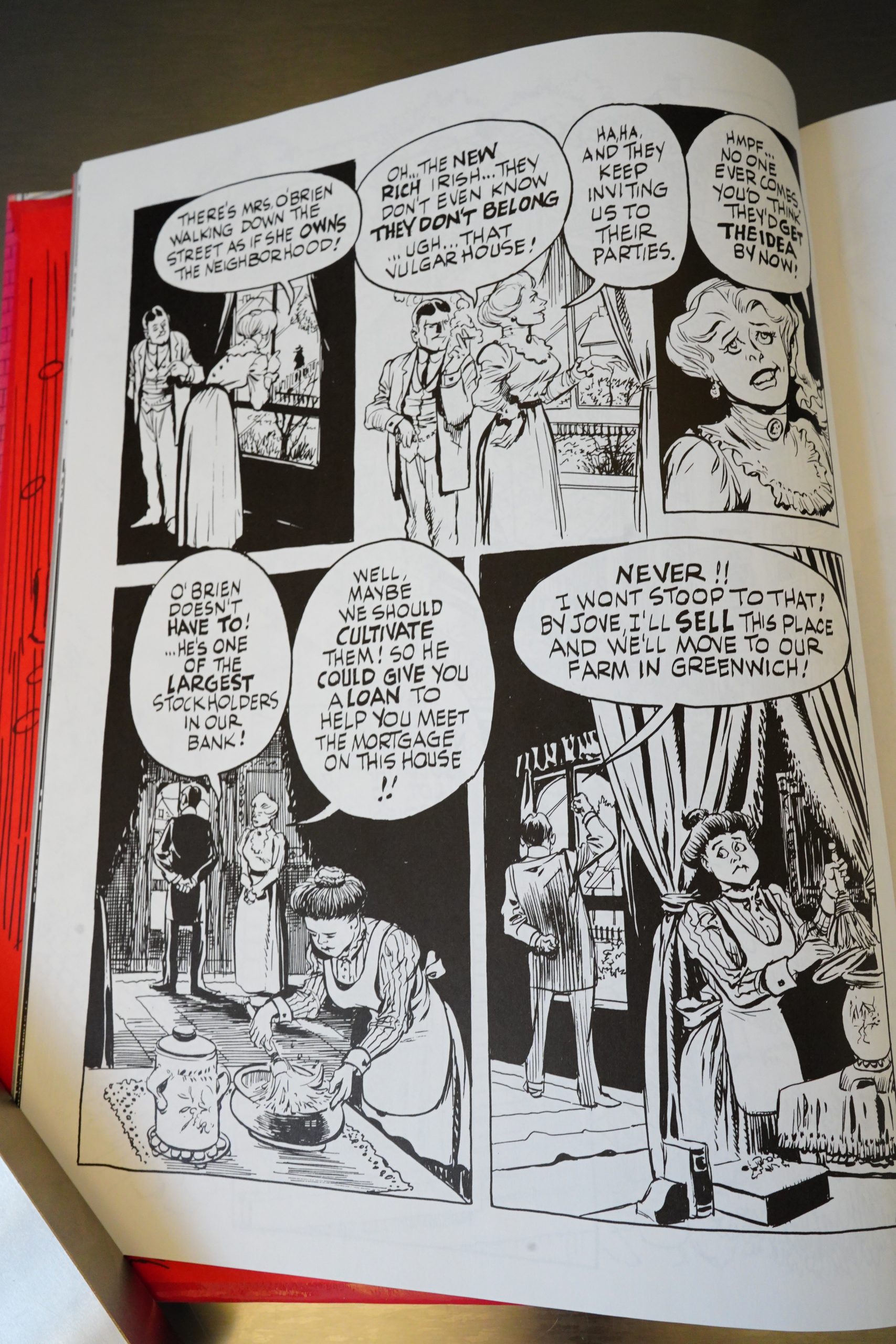

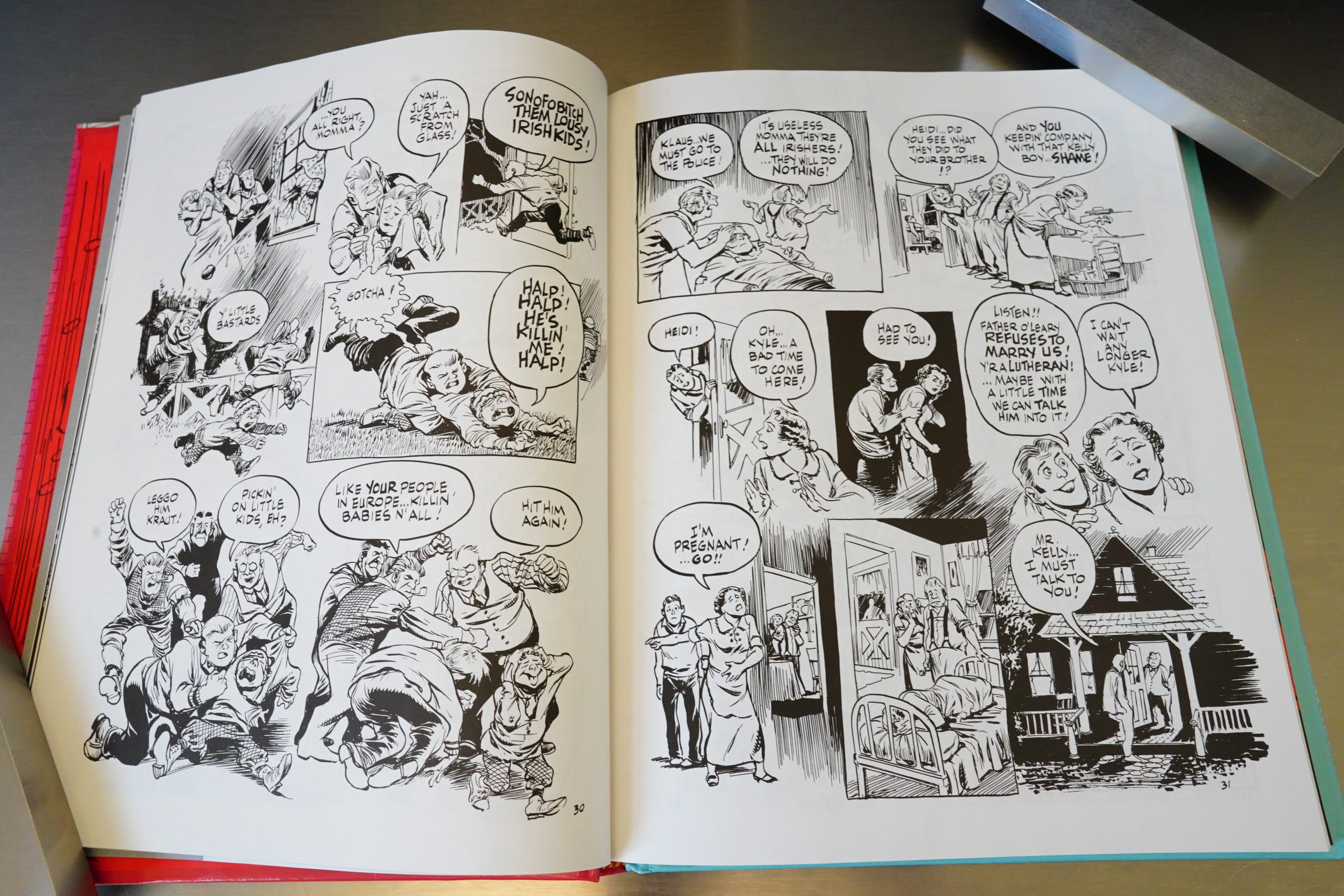

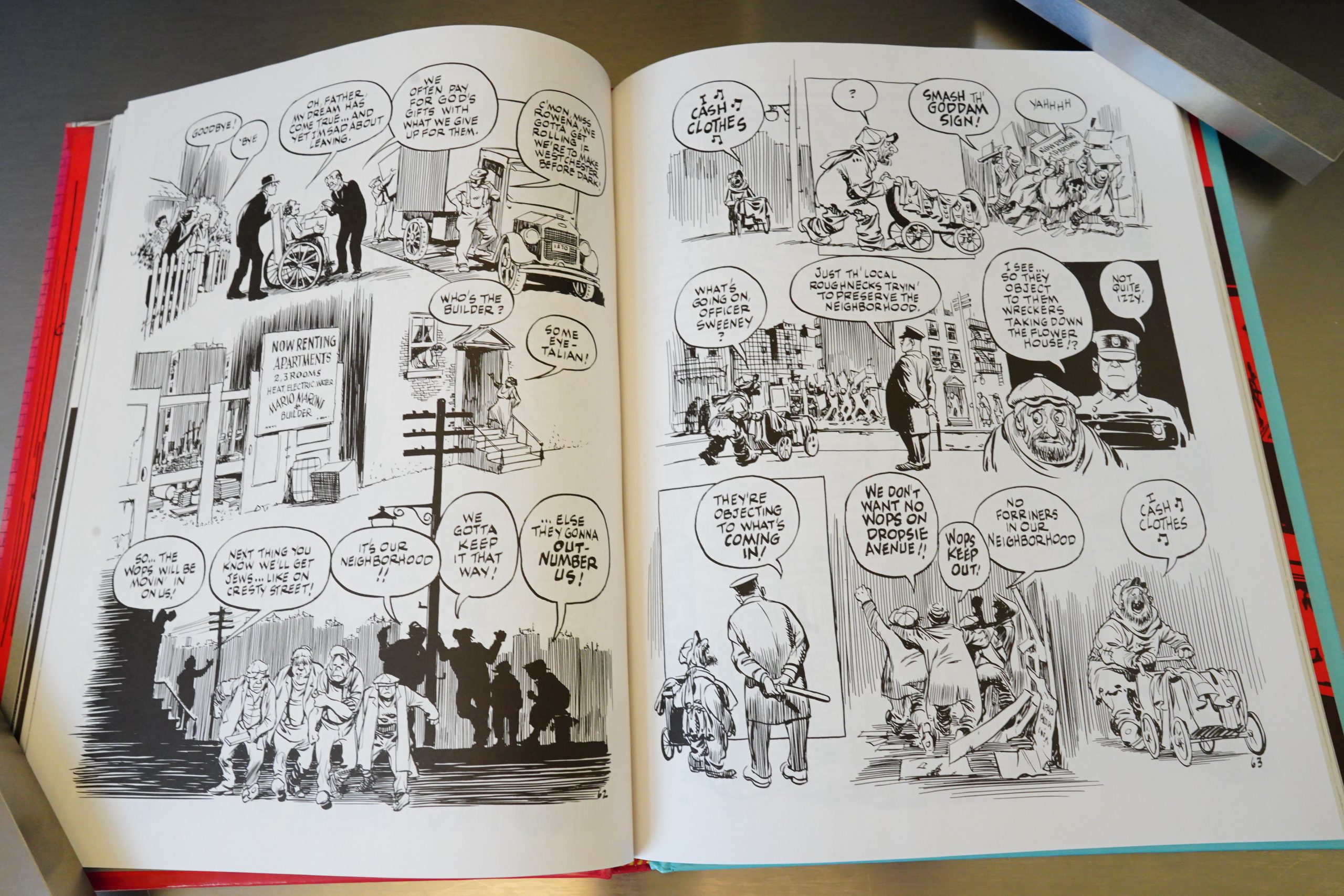

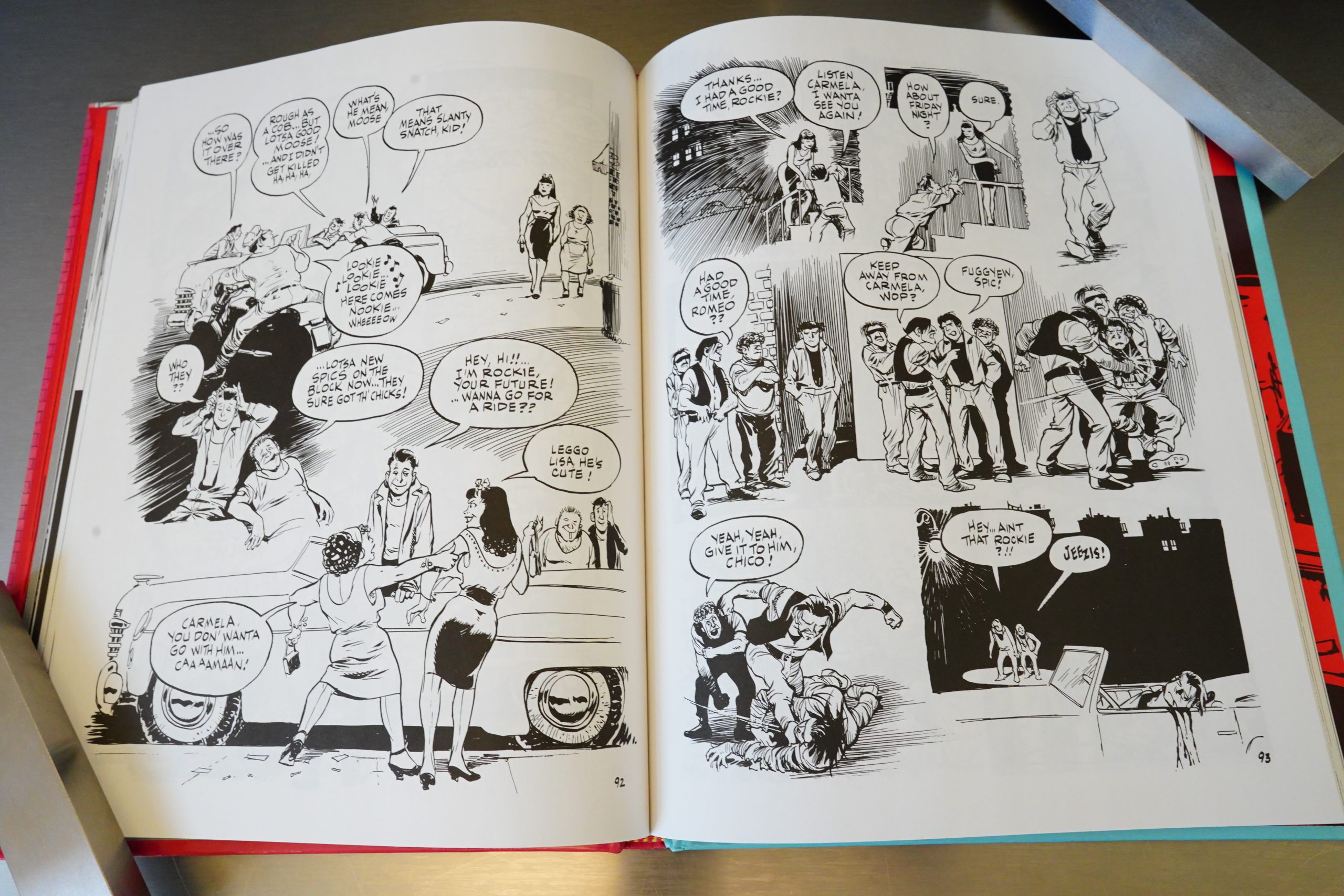

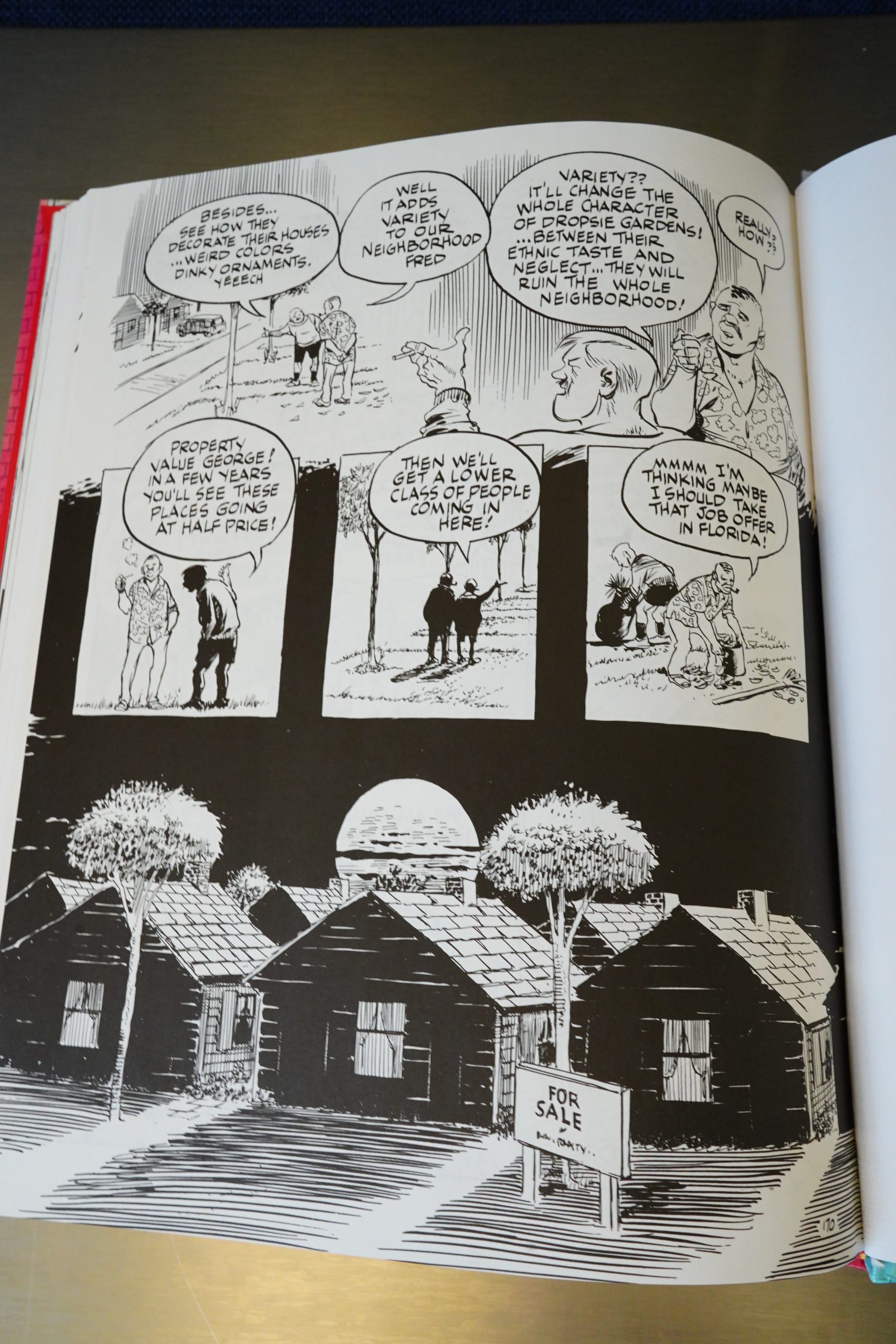

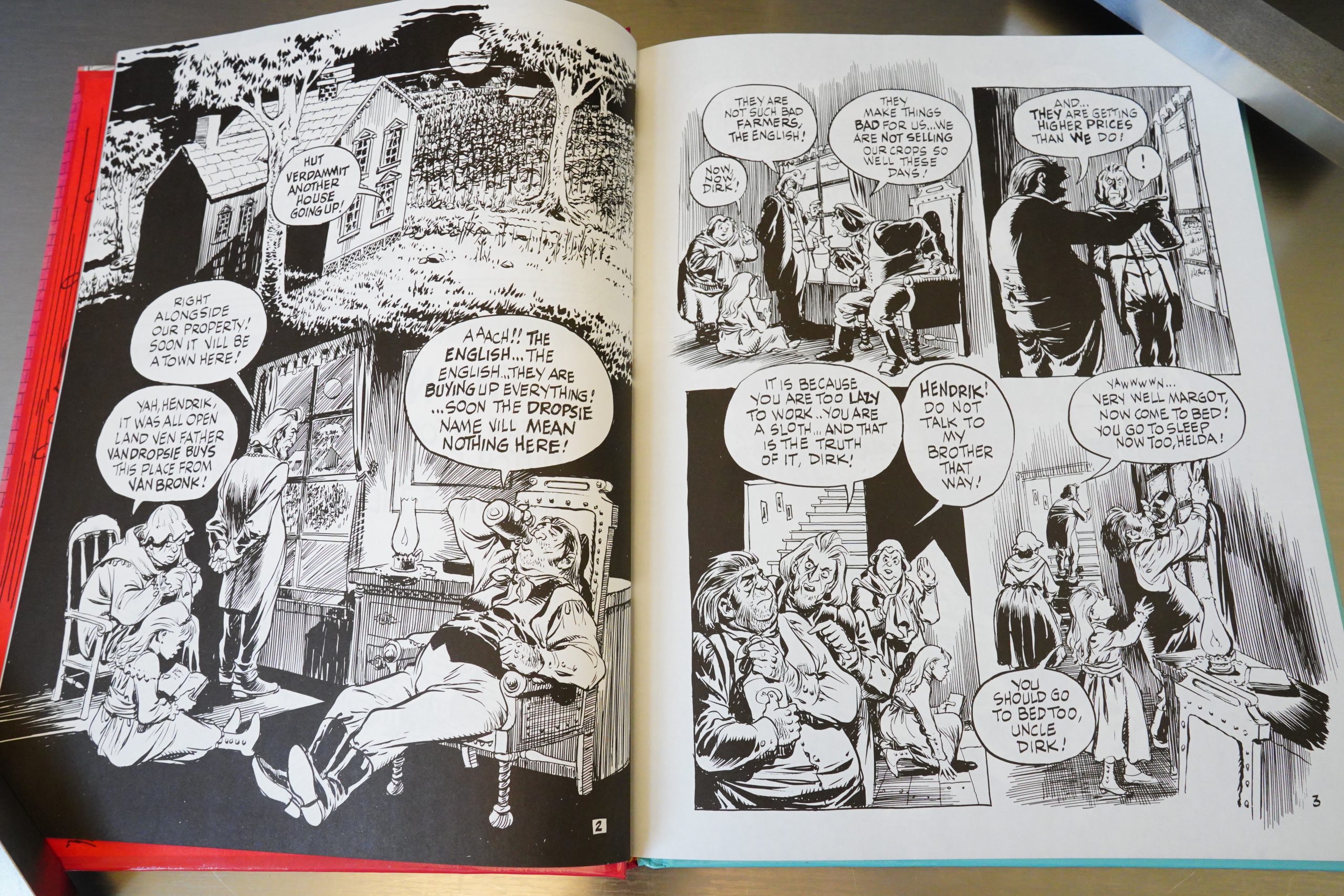

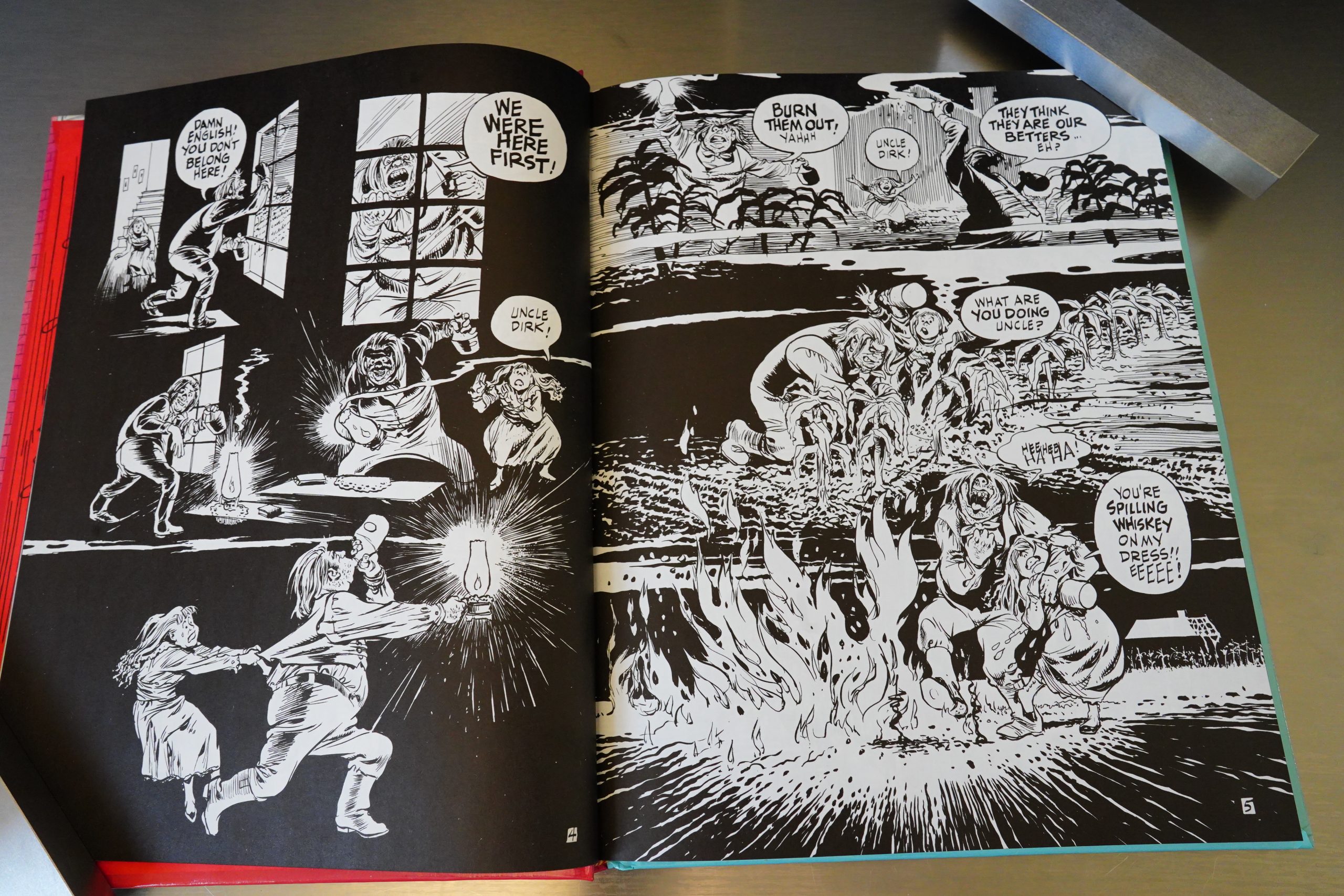

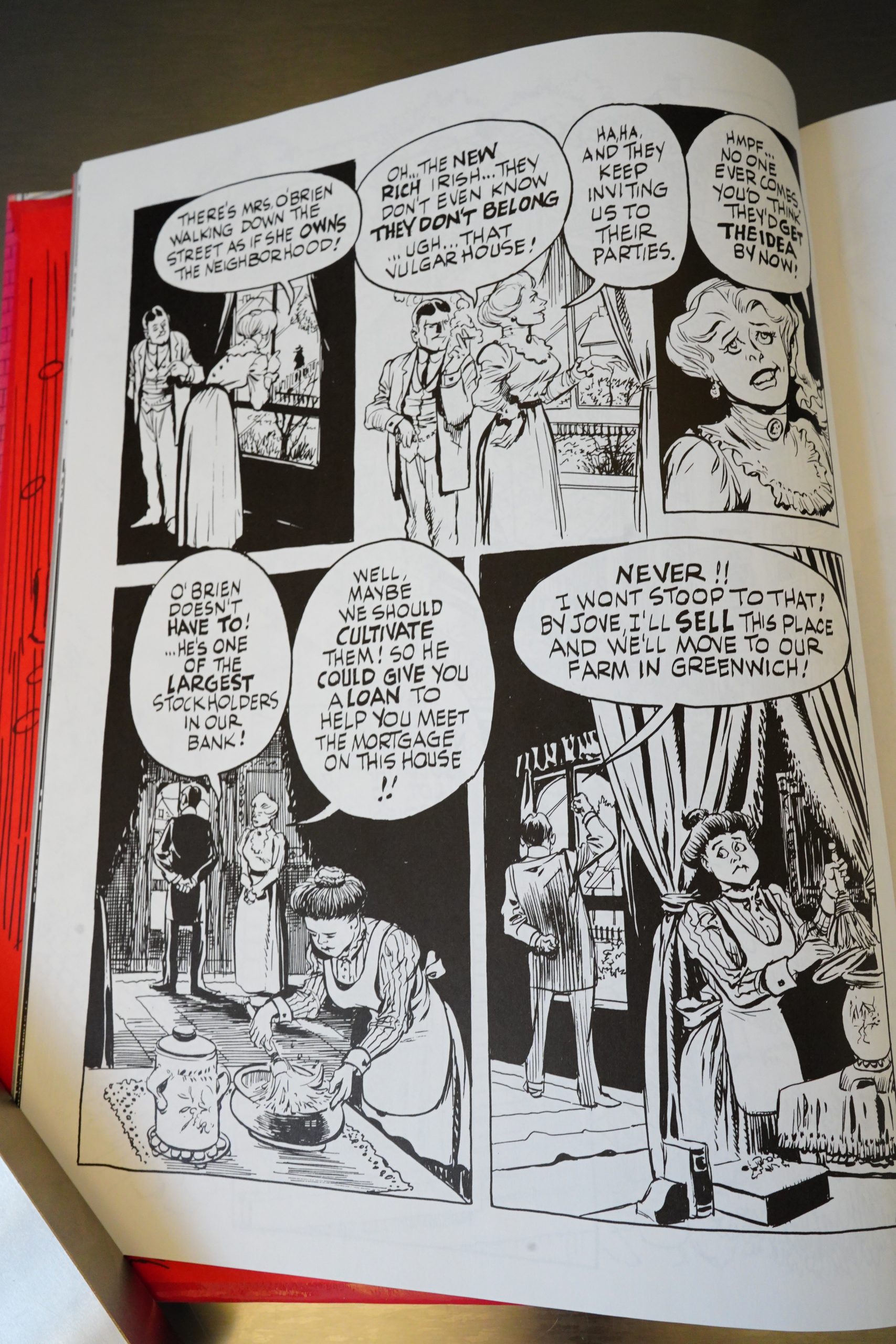

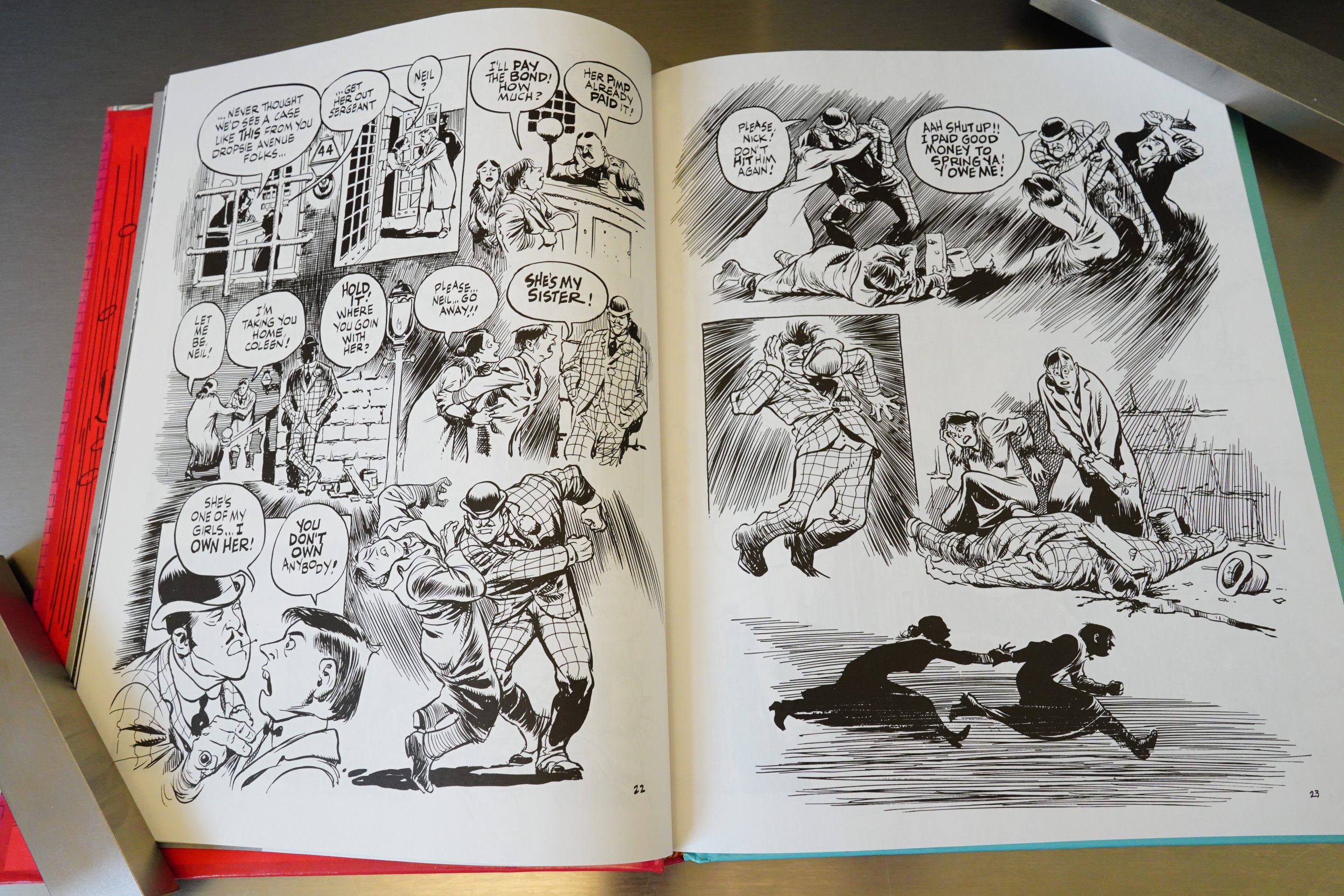

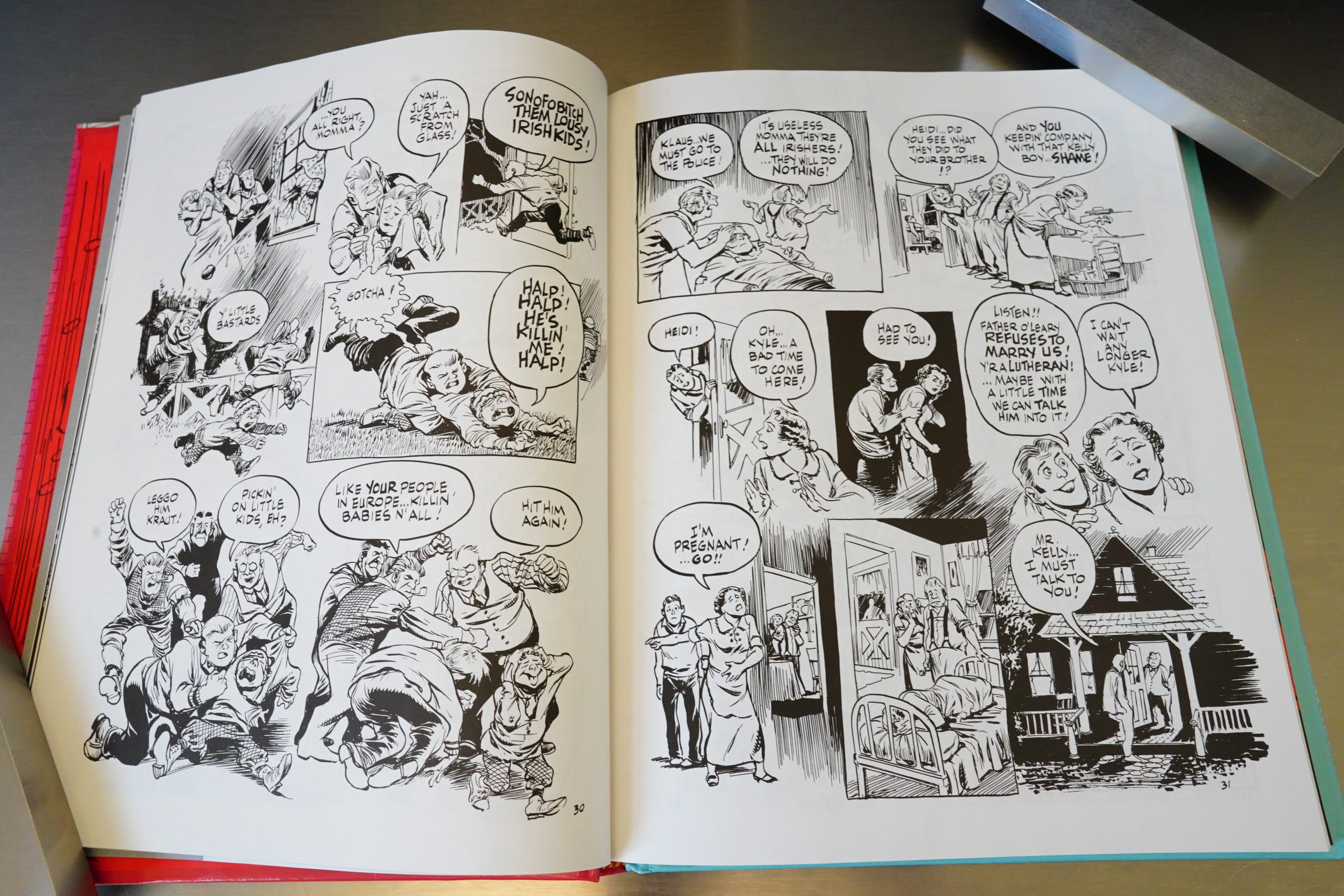

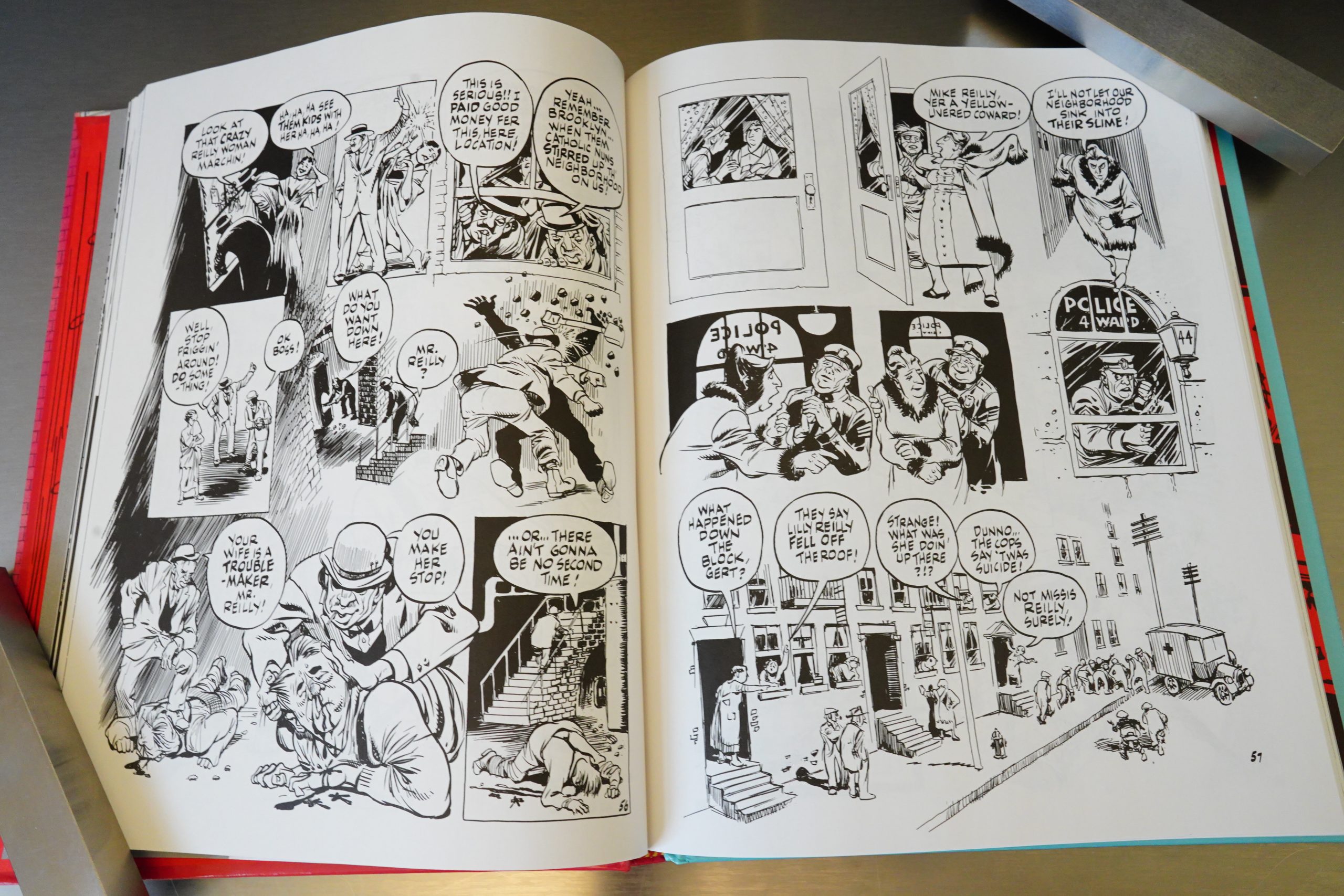

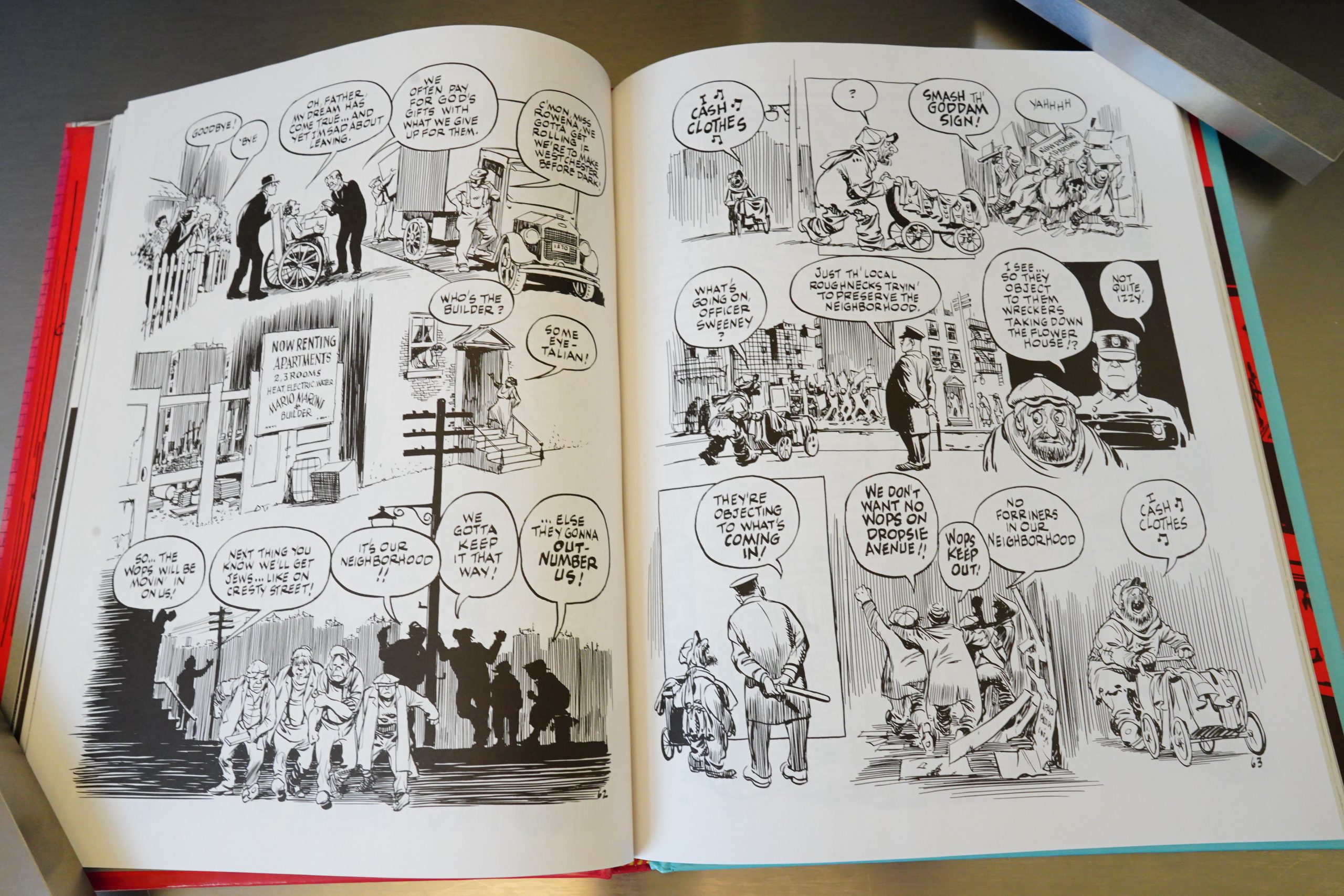

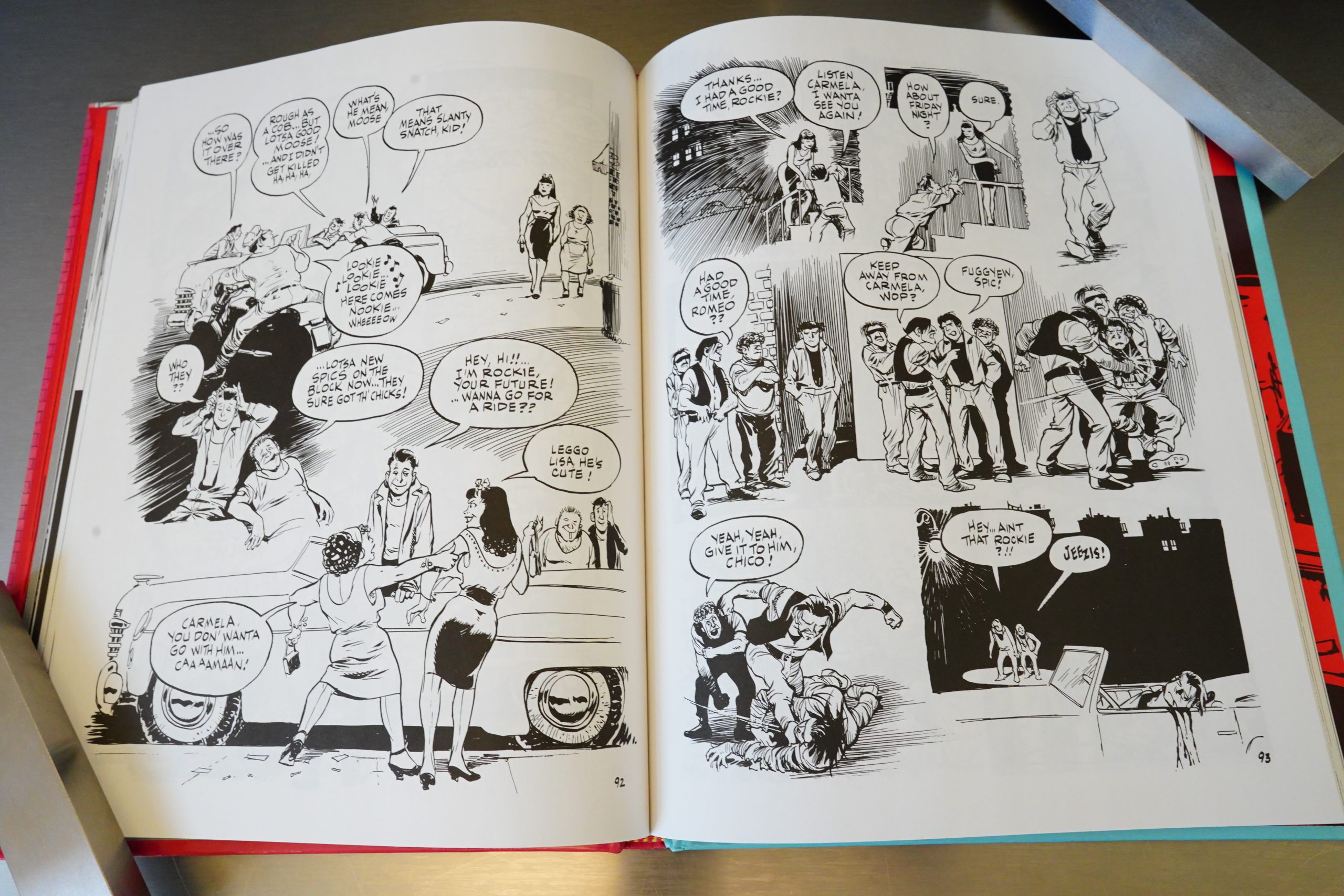

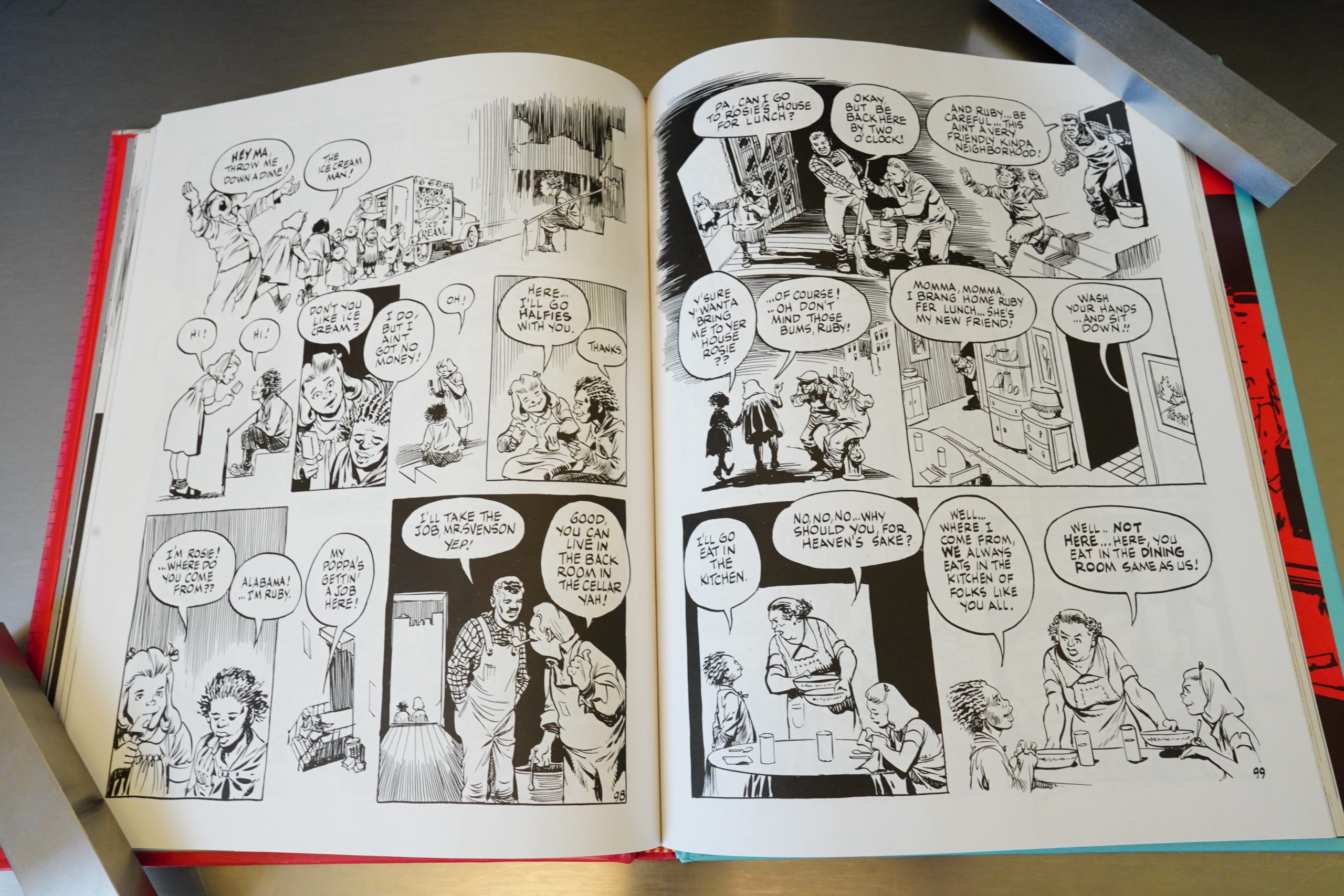

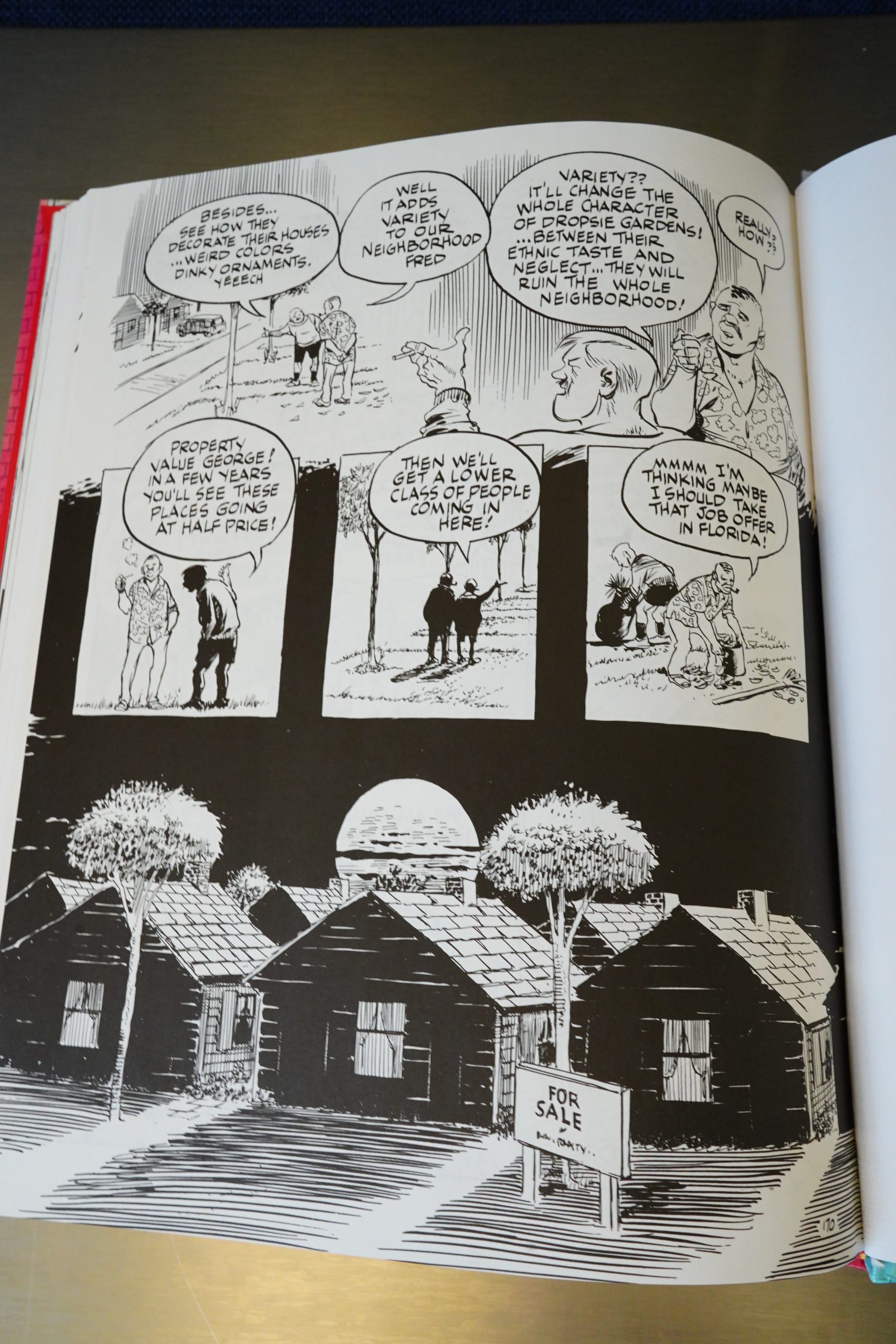

And, once again, Eisner’s theme is that every generation sees the next generation as low-down encroaching riff-raff, from the Germans looking down on the English on. And as usual, when Eisner has a theme, he hammers it home.

Eisner isn’t much for subtlety in general.

So we get this repeated over and over, being very ironic: New people move in, the older generation moves to greener pastures.

It’s a 160 page book, but it covers more than a century, so we don’t get many pages per character — especially in the first half. That leaves us with a bunch of these vignettes without having any impetus to care about what happens, and it makes for tedious reading. The first half of this book may be Eisner’s most exquisitely boring work ever. It’s a pain to get through, and I almost ditched the book.

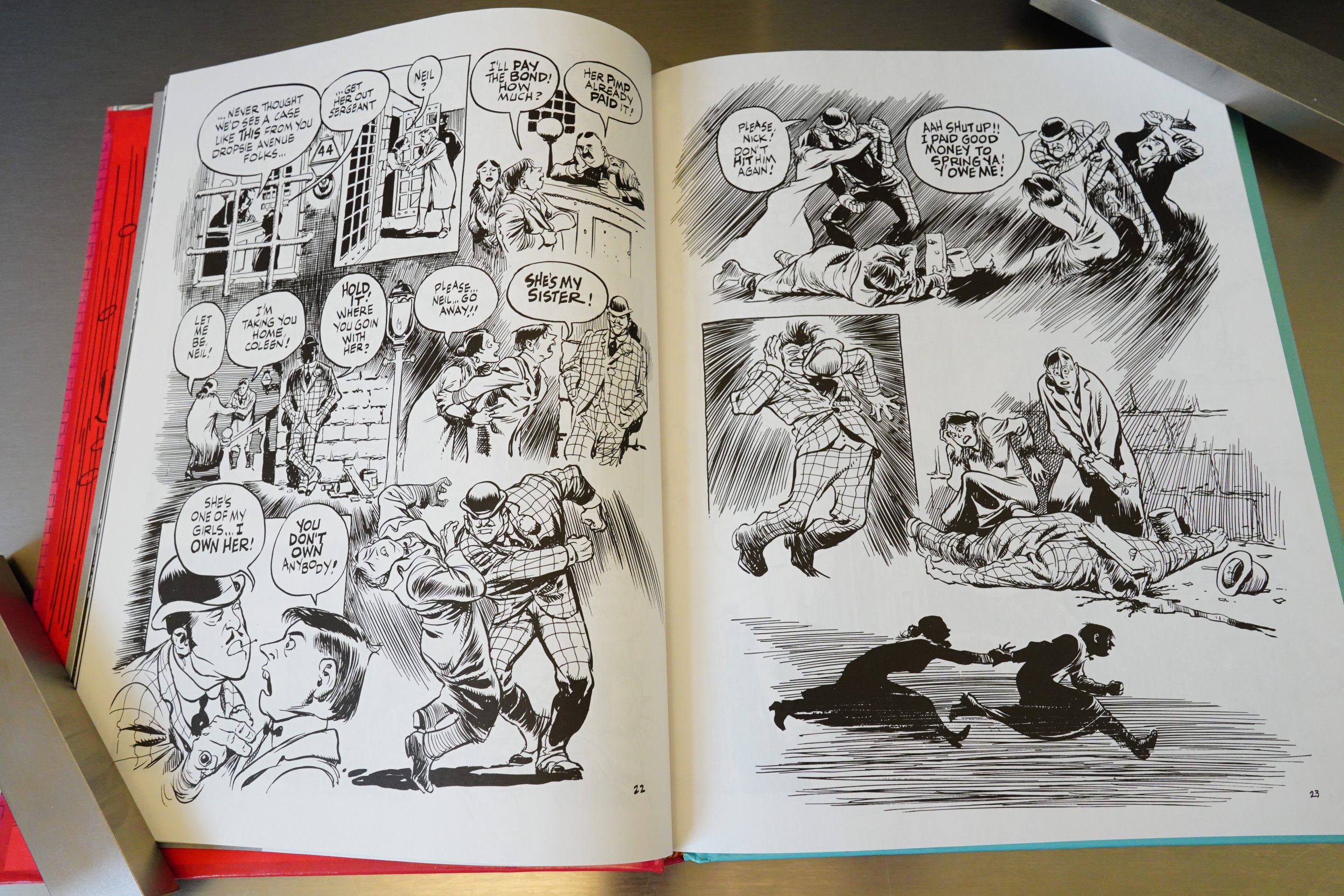

Eisner was about 80 when he did this book, so I guess you can’t blame him for doing retreads. But the art’s as accomplished as ever, even if he’s not as extravagant with his layouts as earlier. Within the straitjacket of his concept, the storytelling is very smooth.

The cops are the worst.

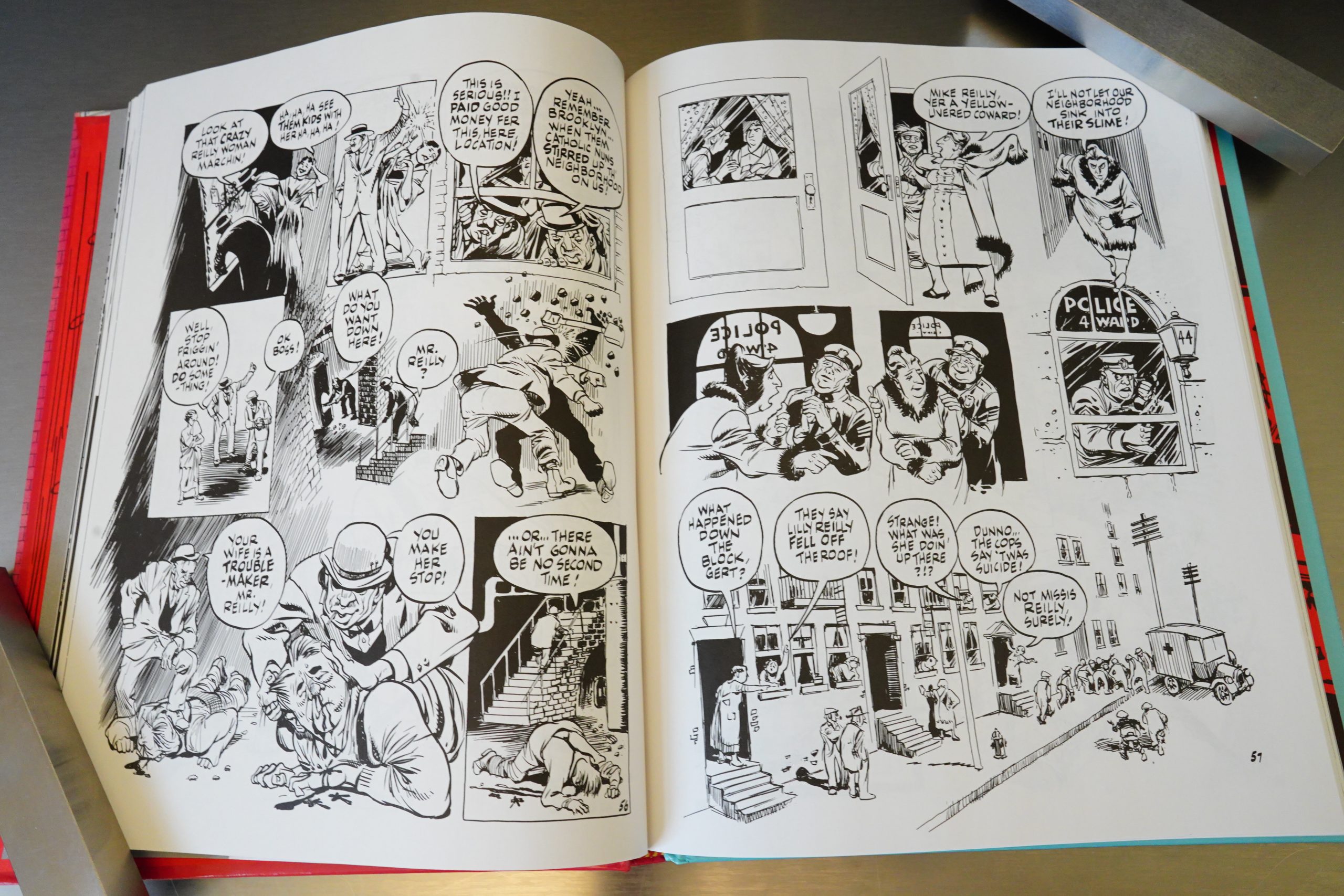

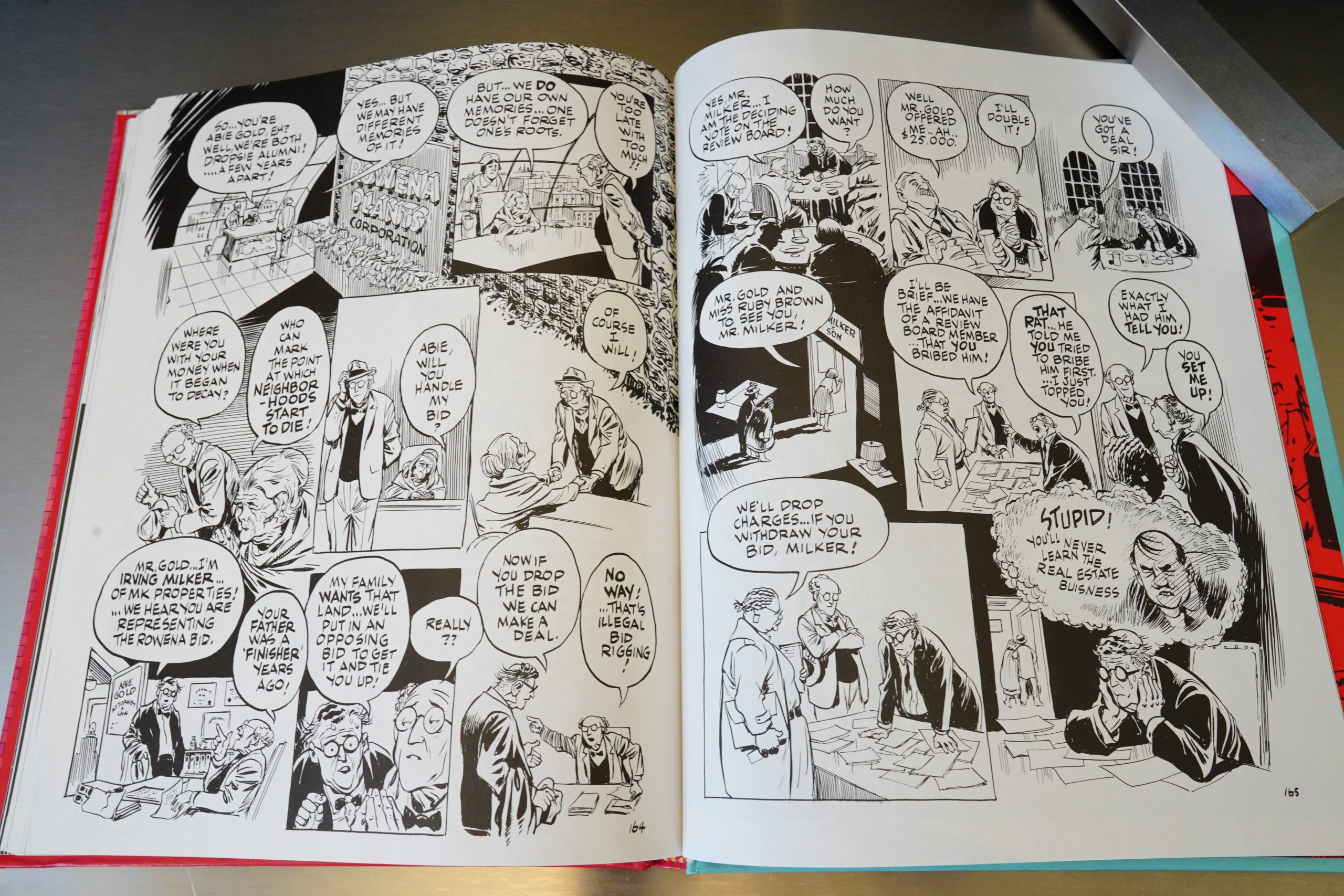

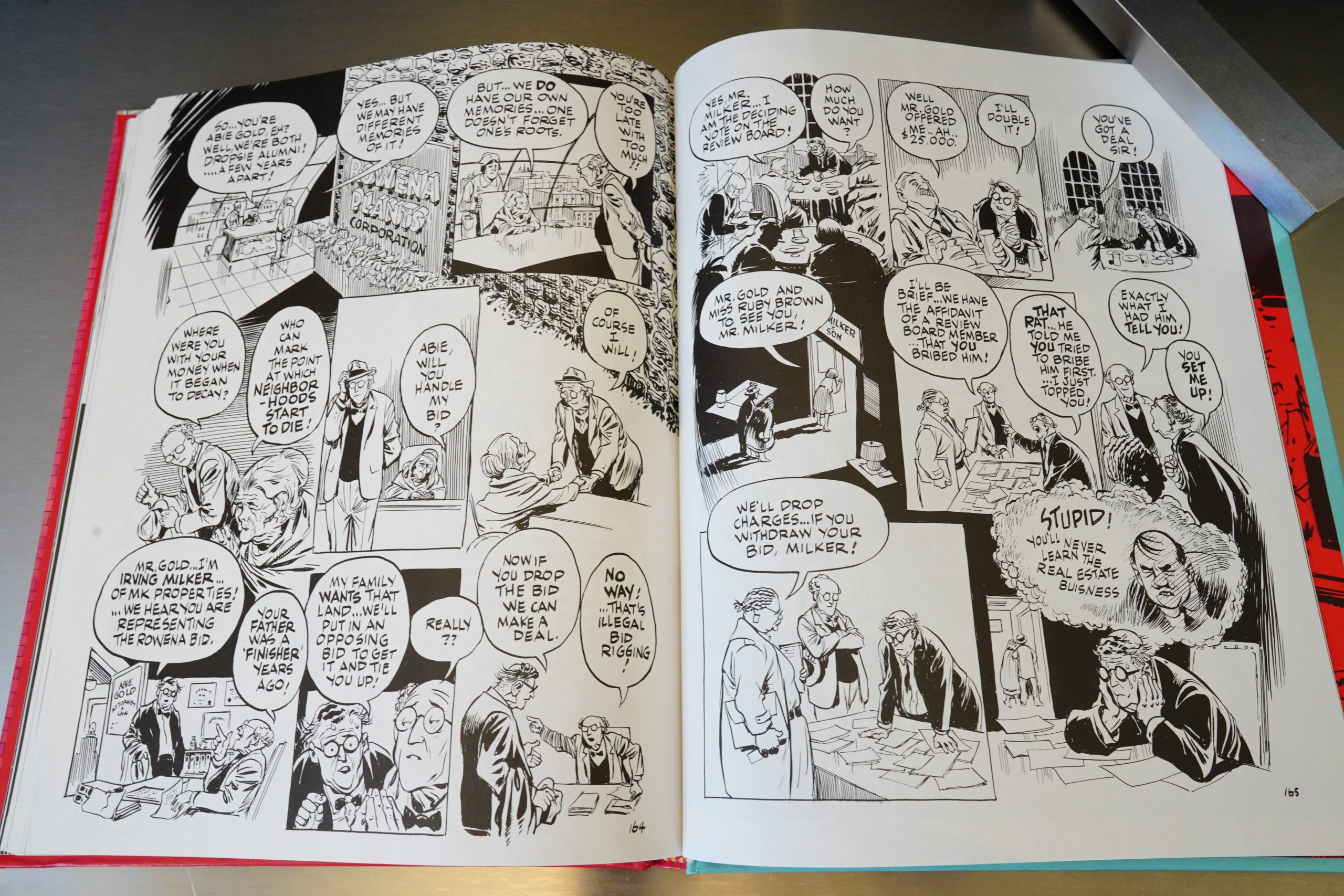

We get a shift around the half-way point of the book (which coincides with the timeline catching up with Eisner’s own life). Eisner starts introducing more interesting characters, and we start following their wheelings and dealings over the decades, and the book actually starts becoming rather interesting.

But, as ever, we return to The Theme.

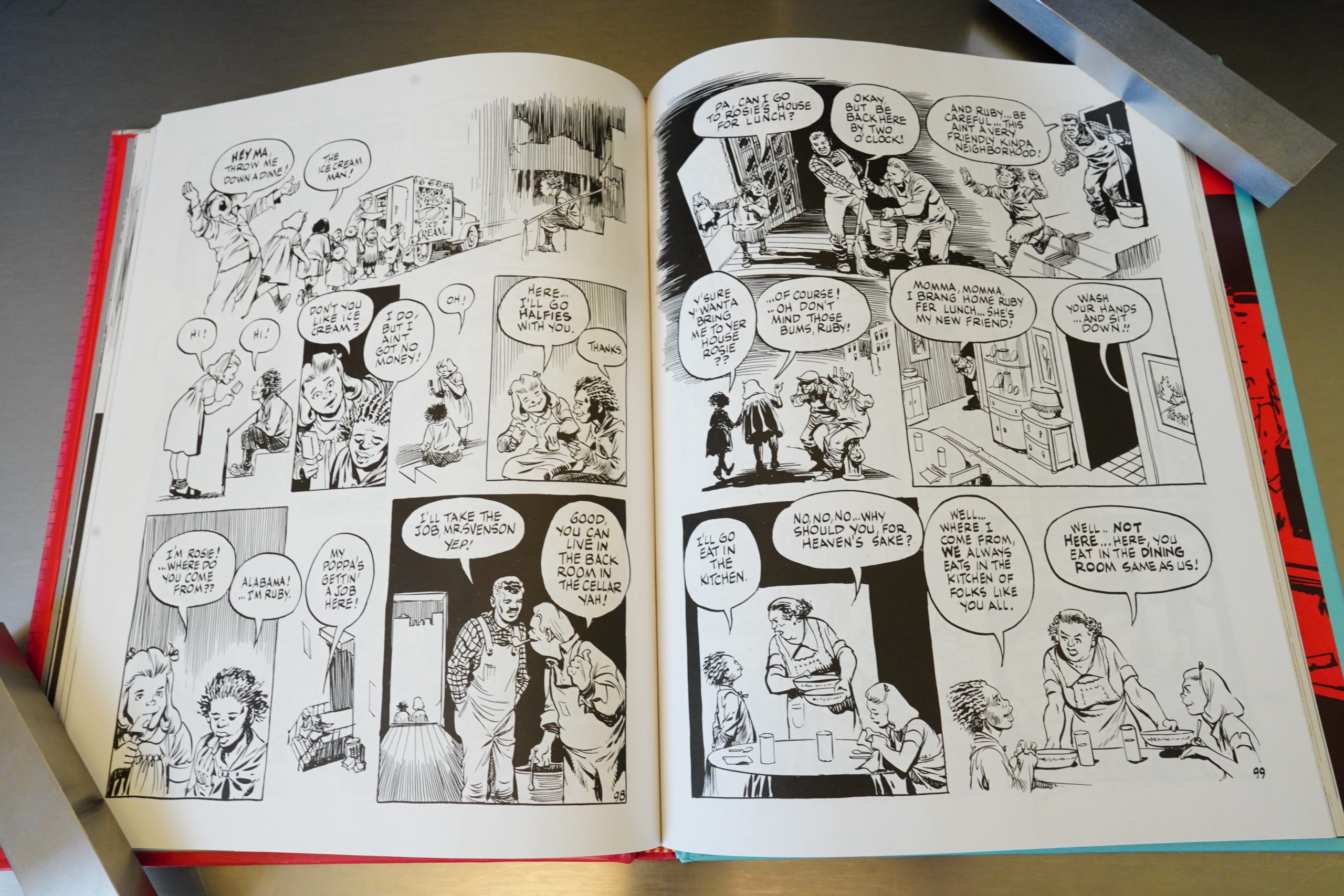

There’s only a single population shift that Eisner portrays as being rather civilised — when Black characters move in from the South, the Jewish population is kinda cool about it.

By the end of the book, I found myself rather gripped by the story — totally unexpectedly, scenes like this started having an emotional impact.

And we end on the requisite ironic note. OOPS SPOILERS

So — this was a lot better than I had expected, but the first half of the book is tough sledding.

Bill Skelly writes in The Comics Journal #183, page 42:

Dropsie A venue: The Neighborhood begins

with a nine-page sequence that is as perfectly

conceived and executed as anything Eisner has

ever crafted. In 1870, the Van Dropsie family

(descendants of the original Dutch settlers)

bemoans the division of the remaining small

farms into lots. A drunken uncle rages into the

night against the English newcomers. and acci-

dentally sets fire to his young niece. This pow-

erful opening segment, which ends with the

dead girl’ s father exacting immediatejustice on

the uncle, is both shocking in its sudden vio-

lence and

sublime in its

economy.

Uhm… I’m guessing the author here has never seen a 30s B movie melodrama?

The Comics Journal #183, page 44:

Eisner’s principal challenge in tracing the

125-year history of a single community in-

volved finding story-telling strategies to com-

press the timespan into 170 pages while still

involving the reader in well-defined characters

and situations. Typically, he rejects the obvious

method of creating text-laden chapter di visions

to easily delineate the passage of time and fill in

the narrative gaps. Nor does he rely on captions

— there are only a handful of captions in the

entire book. To his credit, Eisner effectively

weaves the indicators of the passage of time

(and other expository material) into the flow of

the pages, which average five or six panels

each.

A word about these page layouts: they are

largely without standard panel borders, yet the

eye is directed through the page, from image to

image, without hesitation. Unlike so many

mainstream comics of today, one never has to

pause to decide which panel to read next. When

you consider the complexity of Eisner’s pages’

it becomes apparent that his mastery of the

form, at 77 years Of age, has reached near

perfection.

In Dropsie A venue, as in his other graphic

novels. substance is more important than style.

[…]

Up to that point, it seems to me, the author

has shown us that individuals motivated by

greed will overpower those well-meaning souls

who seek to preserve a neighborhood’ s quality

of life. One might wish for a happier conclu-

sion, and it’s true that Eisner tacks onanequivo-

cal twist at the very end rather than expect us to

swallow the sugar straight; but, one can’t help

but go back to his original unvarnished state-

ment: “Neighborhoods have life spans. They

begin, evolve, mature and die.” Had his narra-

tive adhered to this statement, the death of

Dropsie Avenue would have had a power only

suggested, finally, by the image on the back

cover of the book, which resembles nothing so

much as a bombed-out war-zone.

Even with that sort of uncompromising

ending, the book wouldn’t be a total bummer.

For if no particular action or group of actions

could have permanently halted the decline of

a neighborhood, Eisner’s dramatization of

some of the positive moments that derive from

the community pulling together offers a kind

of inspiration. The best example that comes to

mind is the moment when Father Gianelli and

Rabbi Goodstein surprisingly agree to preside

over an inter-faith wedding. Though the fami-

lies are at first skeptical, the union of an Italian

girl and a Jewish boy gives Dropsie Avenue

one of its finest moments. The marriage stays

together, and the two families find an accom-

modation. Ethnic tensions in the area are tem-

porarily eased. Eisner knows how to deepen a

story by using the unexpected. There is hope in

the inner city.

Paul J Grant writes in The Comics Journal #177, page 32:

With Dropsie Avenue, his latest graphic

novel, Will Eisner returns again to the ficti-

tious Bronx neighborhood he first introduced

in 1978’s A Contract with God. However,

where his previous works used the locale as a

backdrop against which human stories were

enacted, this time the human stories serve to

delineate the story of the gradual corruption

and destruction of the urban microcosm

known as the South Bronx. This time, the

street is the main character, as it weathers

120 years of change.

[…]

Some will doubtless read Dropsie Avenue

and accuse Eisner of resorting to ethnic ste-

reotypes. This is a criticism he not only un-

derstands, but welcomes: “I have a very

strong feeling about stereotypes. It is almost

impossible to function in this medium with-

out the use of stereotypes, which are a very

important part of the language of the me-

dium. Without the use of stereotypes, you

cannot successfully achieve instant recogni-

tion of a charactev So I have absolutely no

apology.”

Eisner has also been accused of sentimen-

talizing the past in earlier works. Although

there are many sentimental parts in Dropsie

Avenue, the novel has a hard, cynical edge.

Eisner concedes that this work was largely

fueled by his anger. “Asl got into this thing,

the more I realized there was a lot of inexcus-

able greed and moral corruption that goes

into the destruction of the neighborhood. The

whole point of doing a book like this is to

show the disintegration is not physical, but

rather a result of human dynamics… an inter-

nal force.”

[…]

Dropsie Avenue is powerful stuff,

wrenched from real-life events, and a far cry

from the typical comics fare. When asked

who he sees as his target audience, Eisner

laughs and replies, “Whenever I’m asked

this, I always say my reader is a 40-year-old

man who’s just had his wallet stolen in a sub-

way in New York.” He continues, on a more

serious note. “I’m addressing myself not so

much to an age group but to a group of

people who have similar experiences and can

understand what I’m saying. Certainly, I can-

not expect a callow youngster who has had

maybe 12 to 15 years of life experiences,

whose life has centered around MTV, to be

interested in the disintegration of a neighbor-

hood or be concerned about why it disinte-

grates. But there are things one can do in this

medium to raise the level of the storytelling

to reach the intellect of the reader. I’m con-

sciously trying, in my work, to make contact

in a context with the internal emotions of

people.”

Here’s somebody on Goodreads:

The art was terrific, but the storytelling quickly became repetitive. Okay, I get the idea — each group that lives in this part of the Bronx thinks that it is better than the newcomers and the neighborhood slowly gets worse and worse. But because we are going through decades, we don’t have any characters to follow, and it quickly just becomes the same thing over and over again, with differently dressed ethnic types despising each other. Feh!

Unexpectedly negative review from PW:

Even his virtuoso draughtsmanship and composition appear to have ossified into self-imitation and pictorial cliche. Despite his obvious affection for urban life, Eisner reduces decades of social patterns to unsatisfying, symbolic characterizations that awkwardly represent an era, rather than embodying genuinely wrought, particularized human interaction.

This is the one hundred and eighty-second post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.