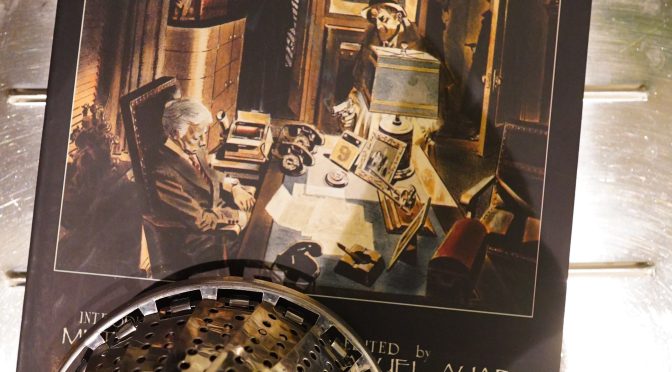

Alex Toth (1995) by Alex Toth

I’m sorry if the tone of this blog series has gotten a bit… chilly. It’s just that I didn’t quite realise before I started this just how many things Kitchen Sink had published that I didn’t really have much interest in. It’s not that the things Kitchen published were necessarily bad — it’s just that I find it hard to even summon even a cursory interest in writing about some of these books, so I may come off more like Grumpy Old Man Shouts At Decades-Old Comics than I intended.

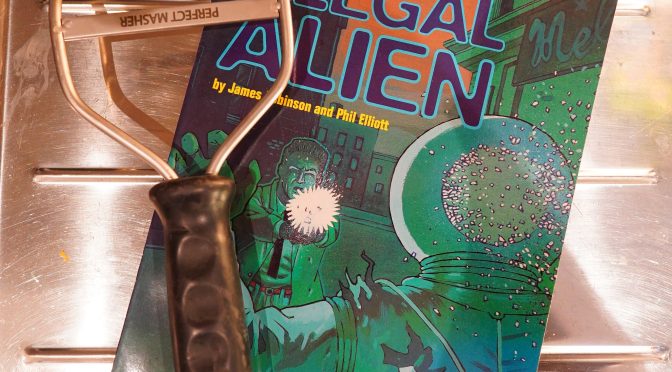

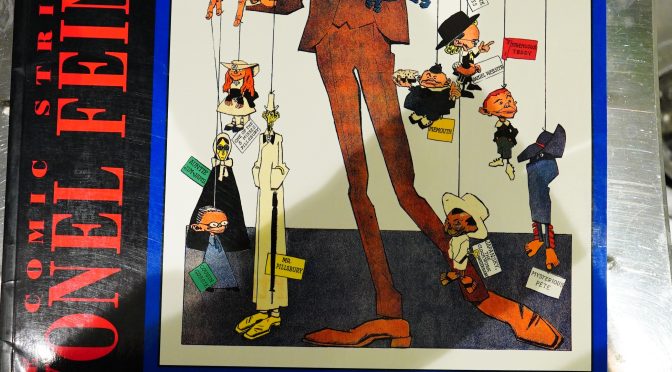

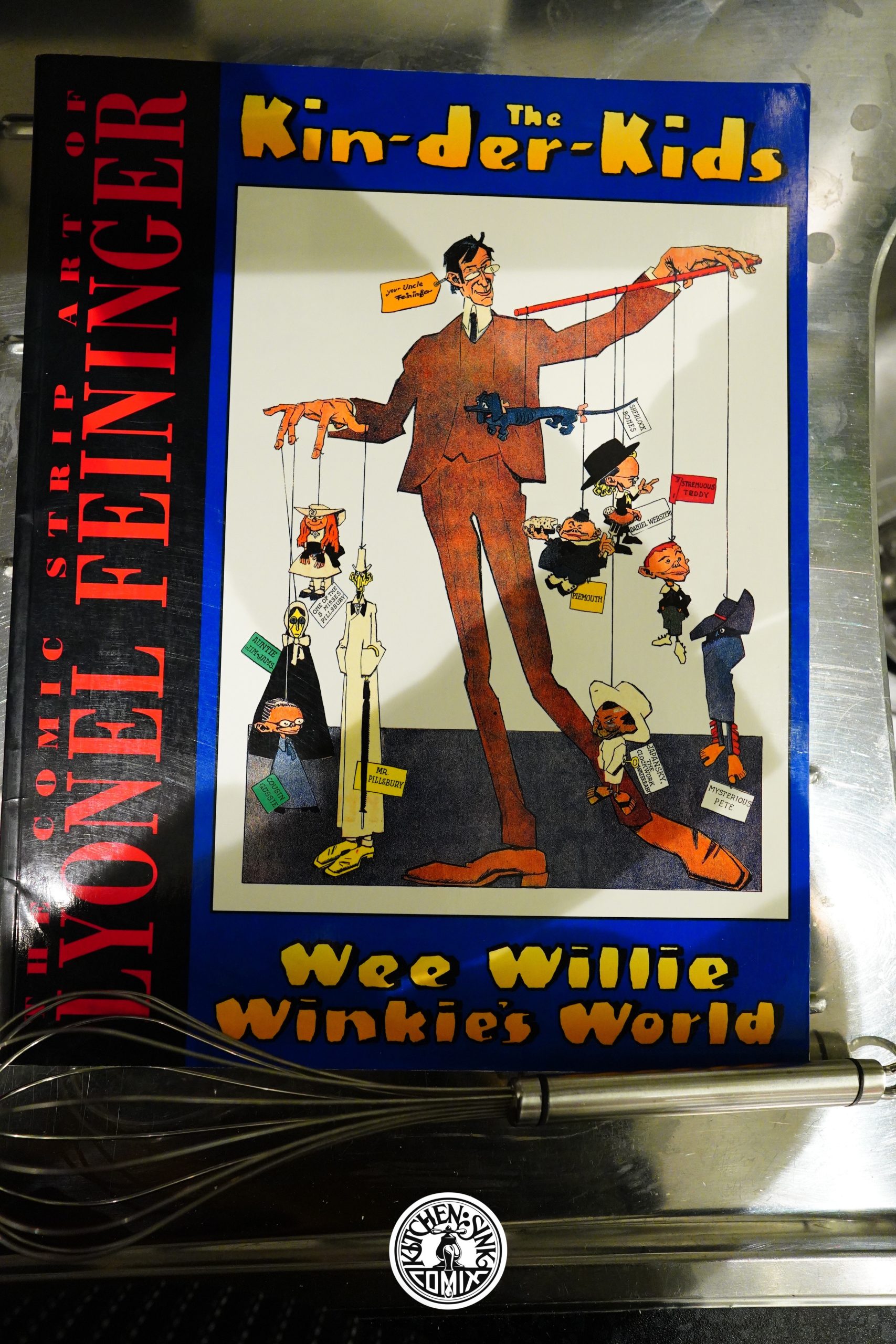

Like — what is this book, anyway? It doesn’t really say so explicitly anywhere what the concept behind the book is.

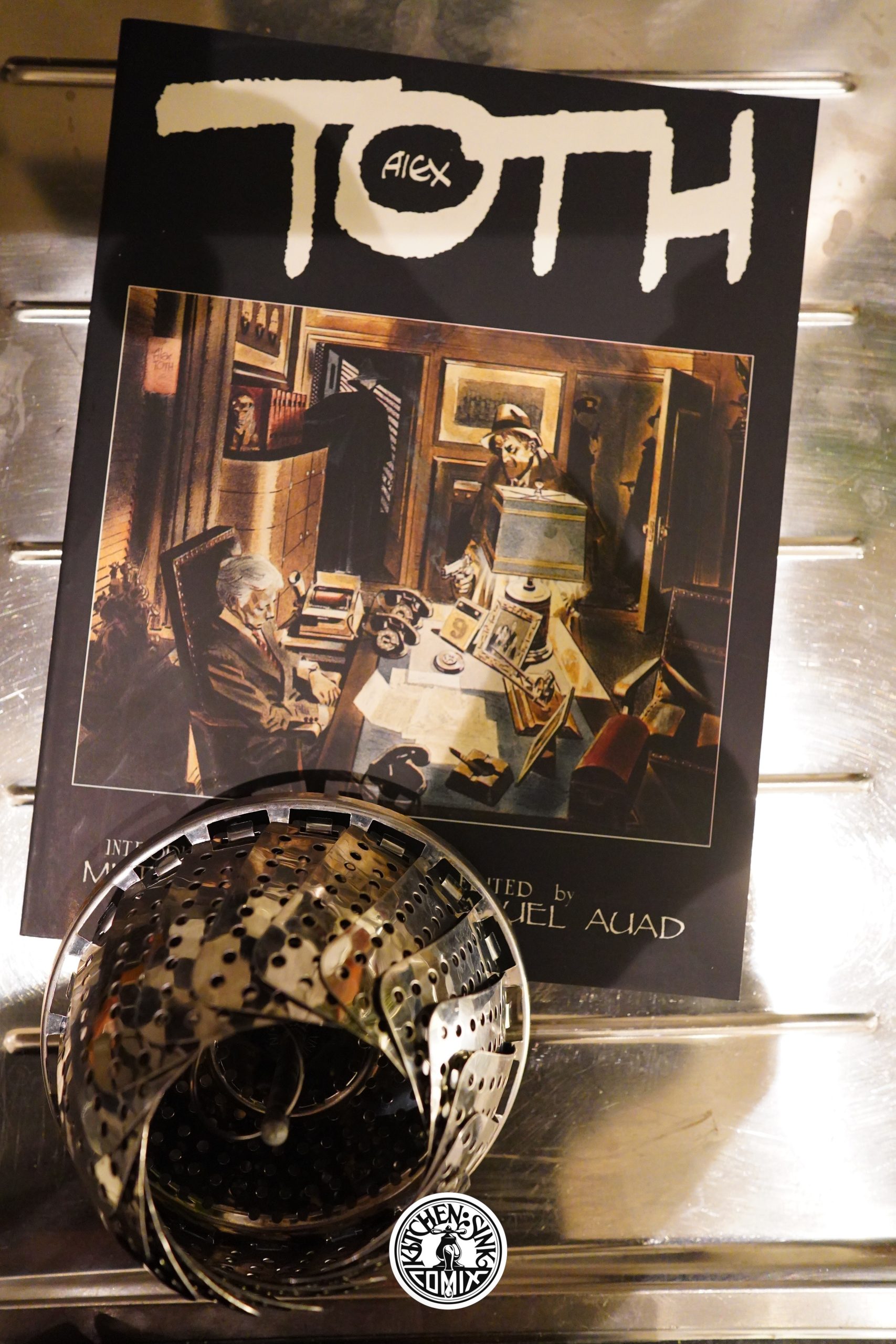

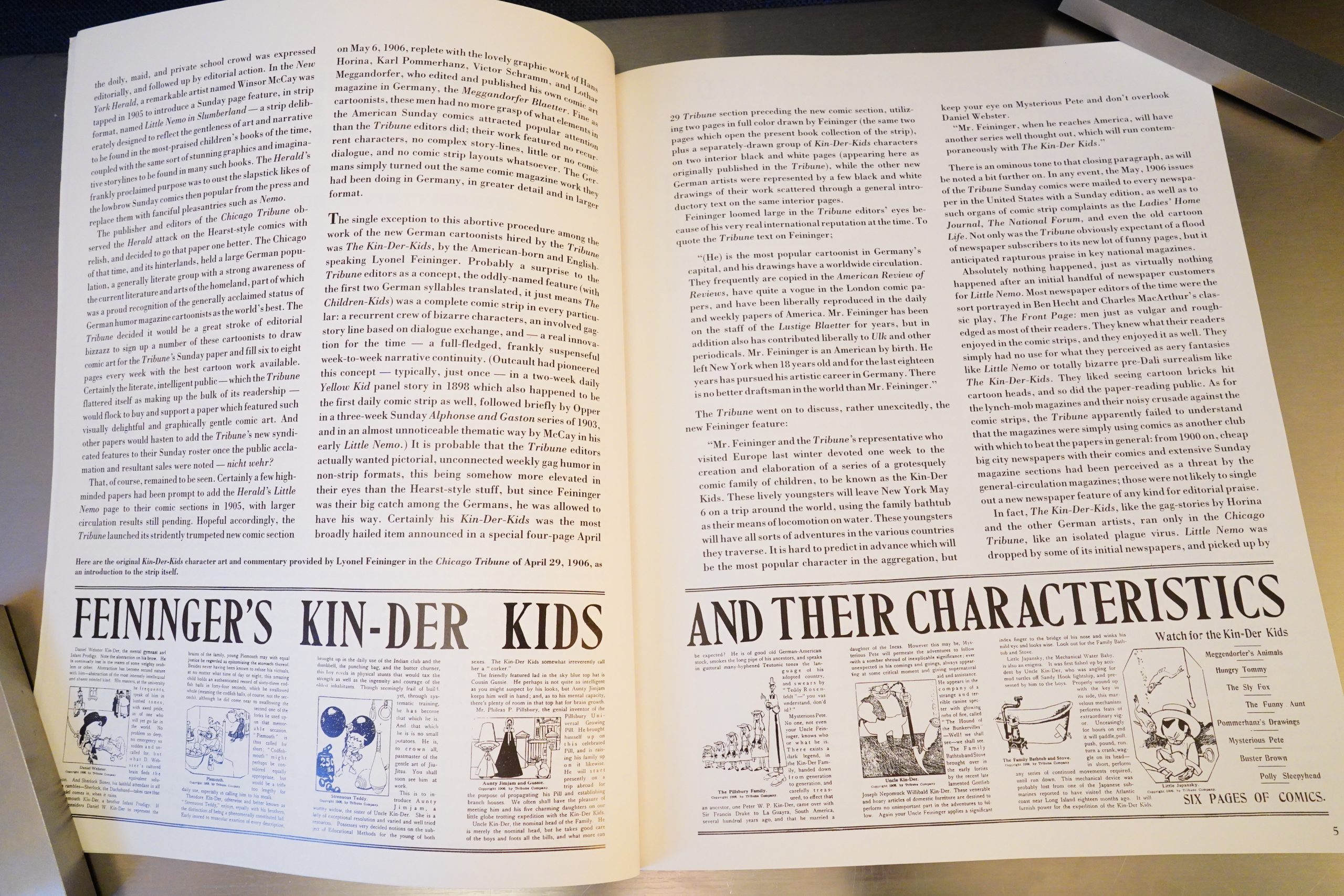

We start with a bunch of introductions that don’t really clarify anything…

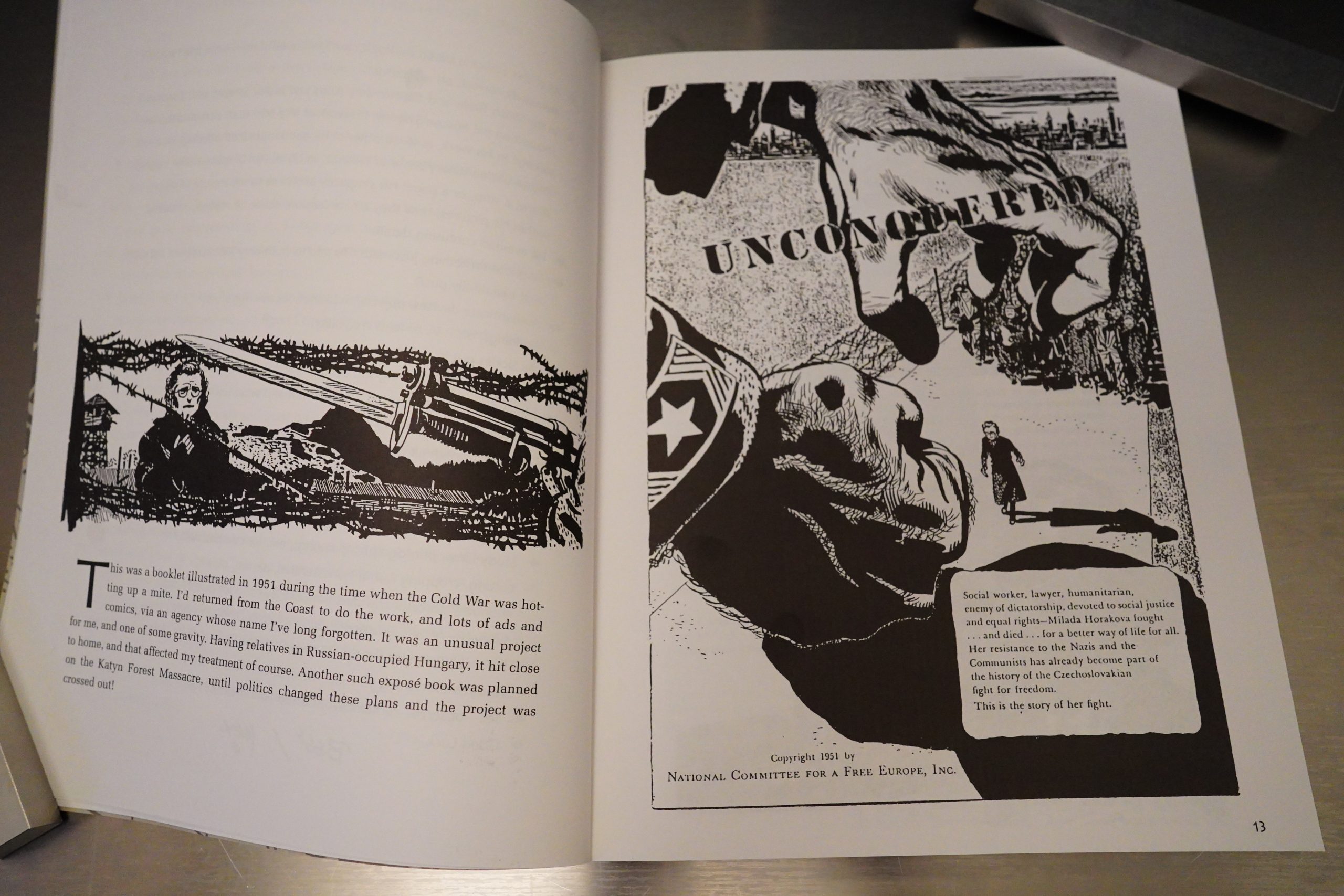

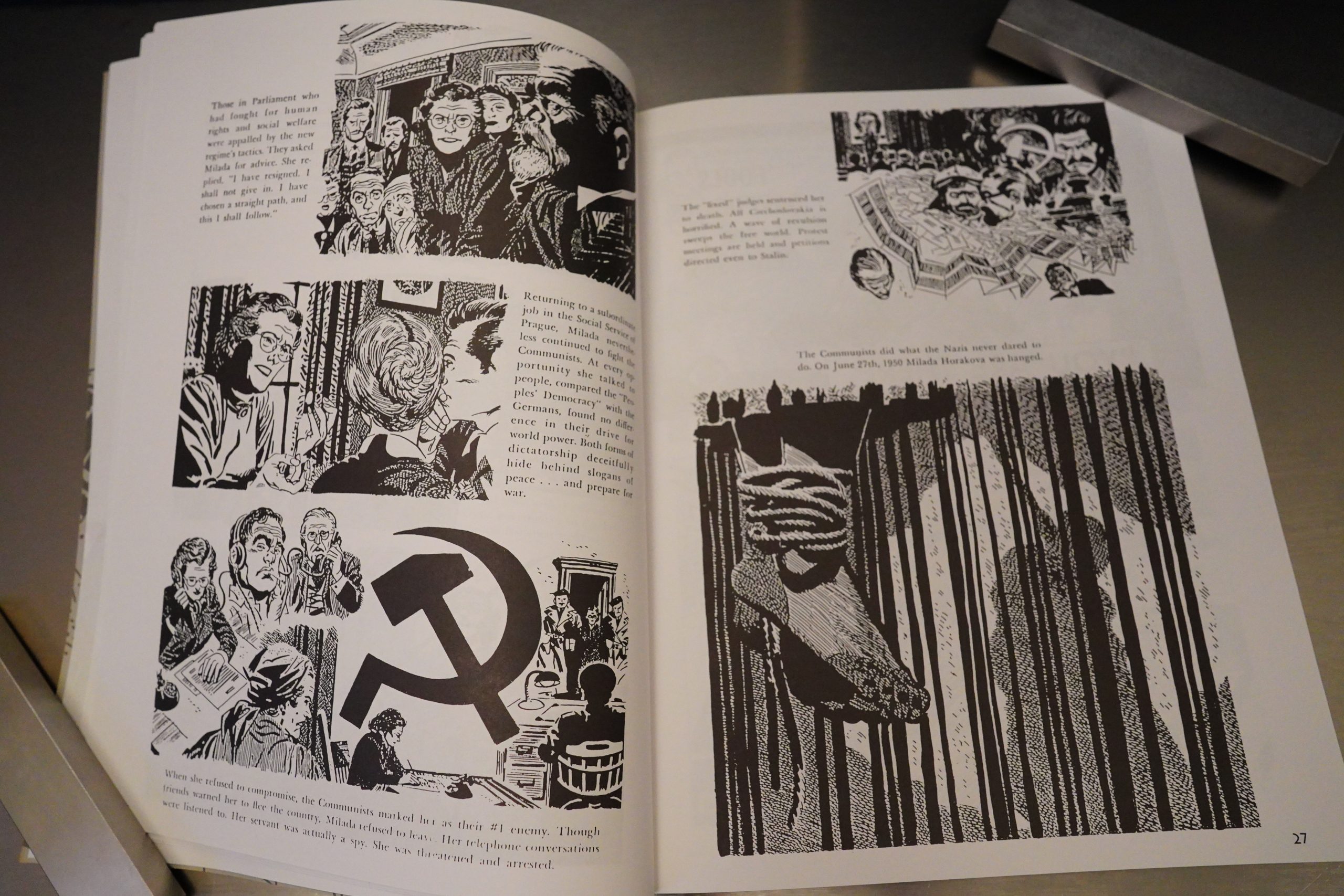

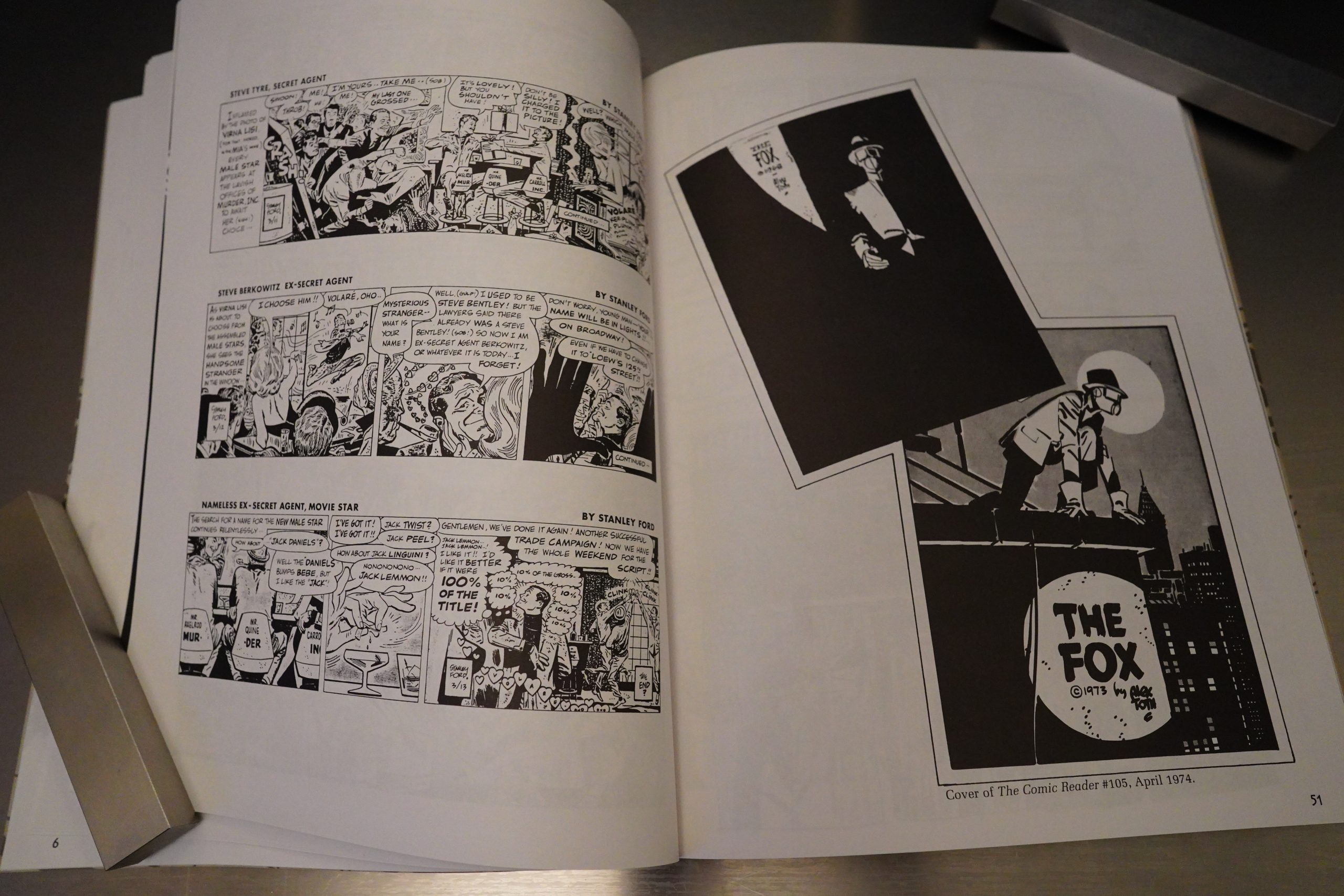

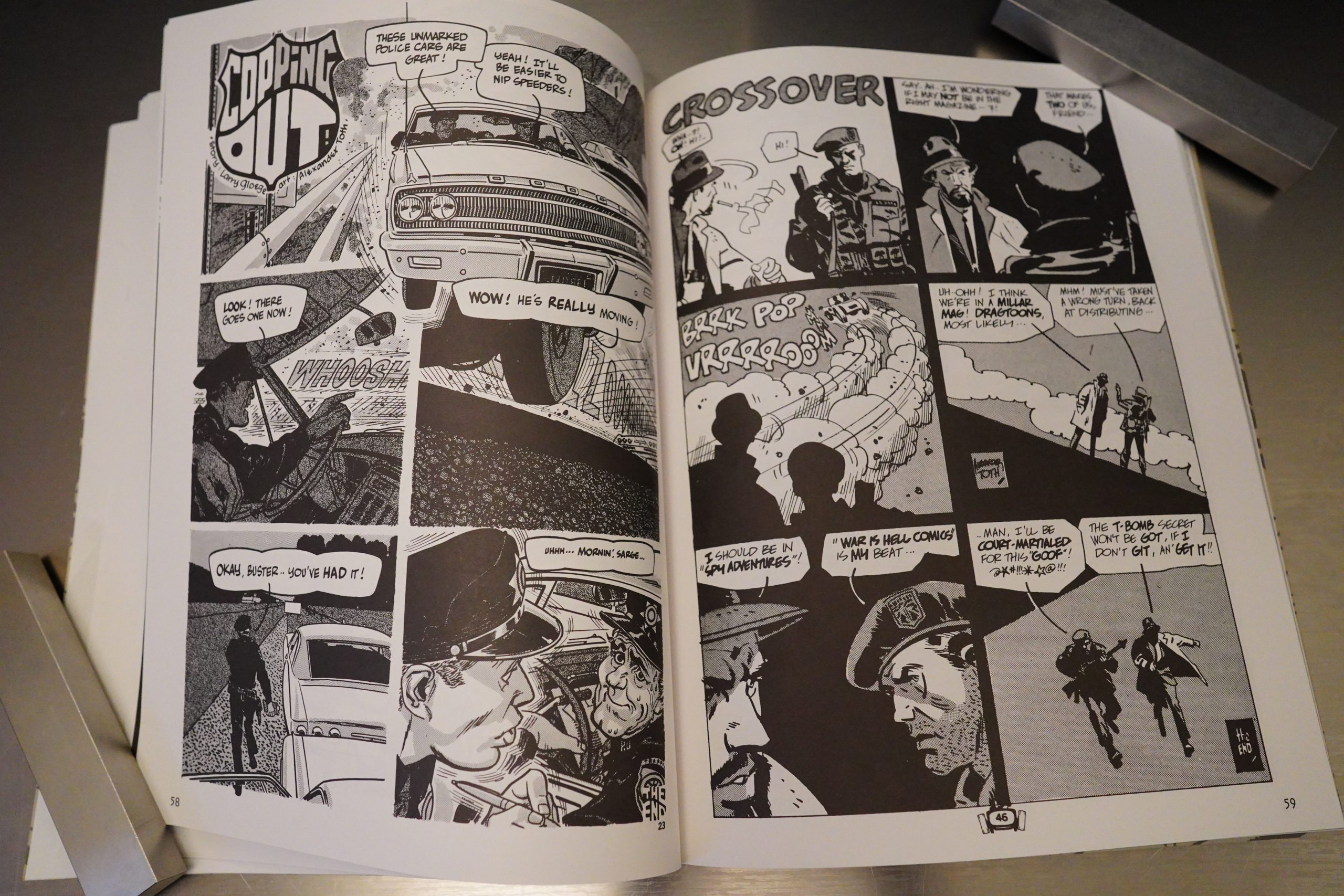

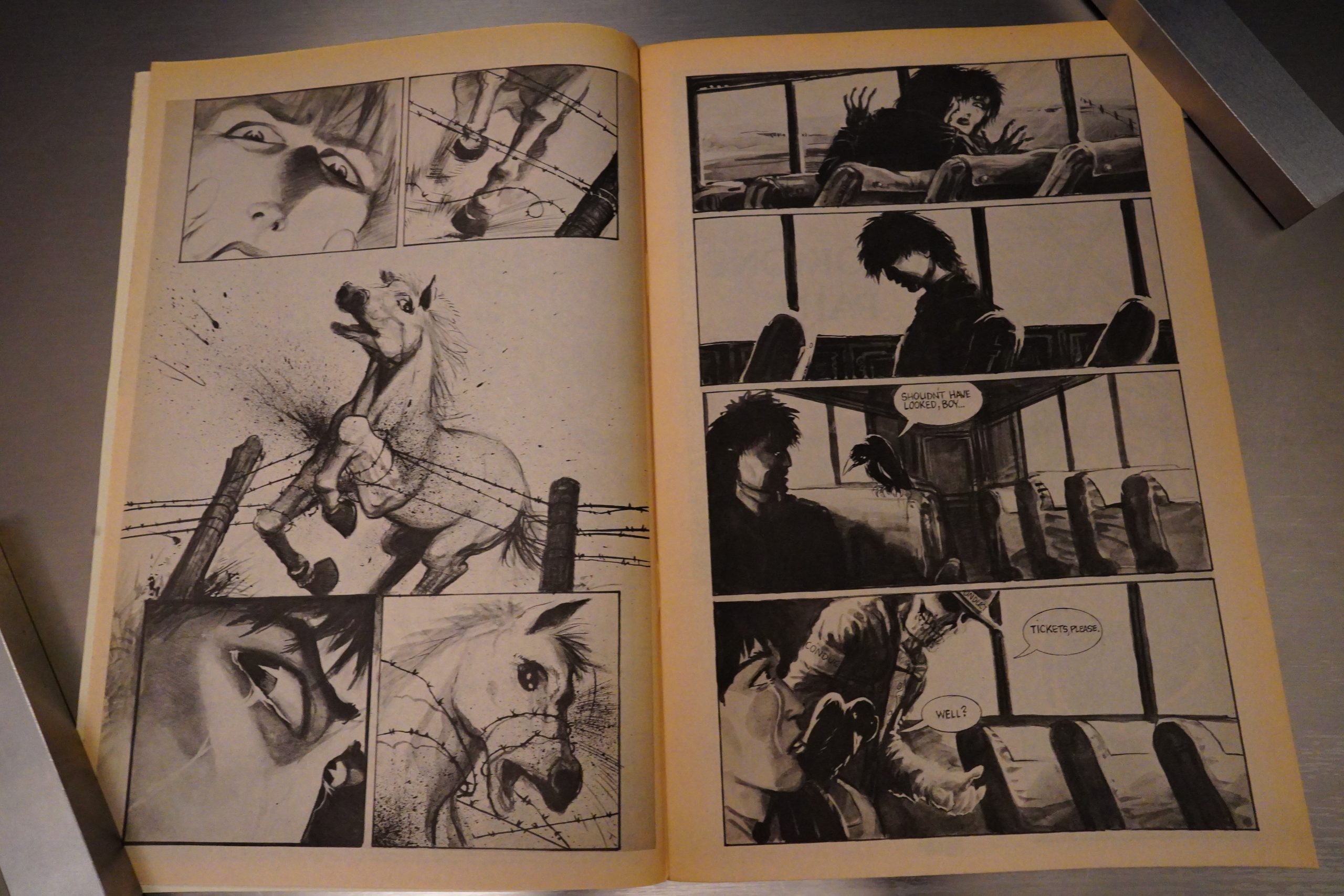

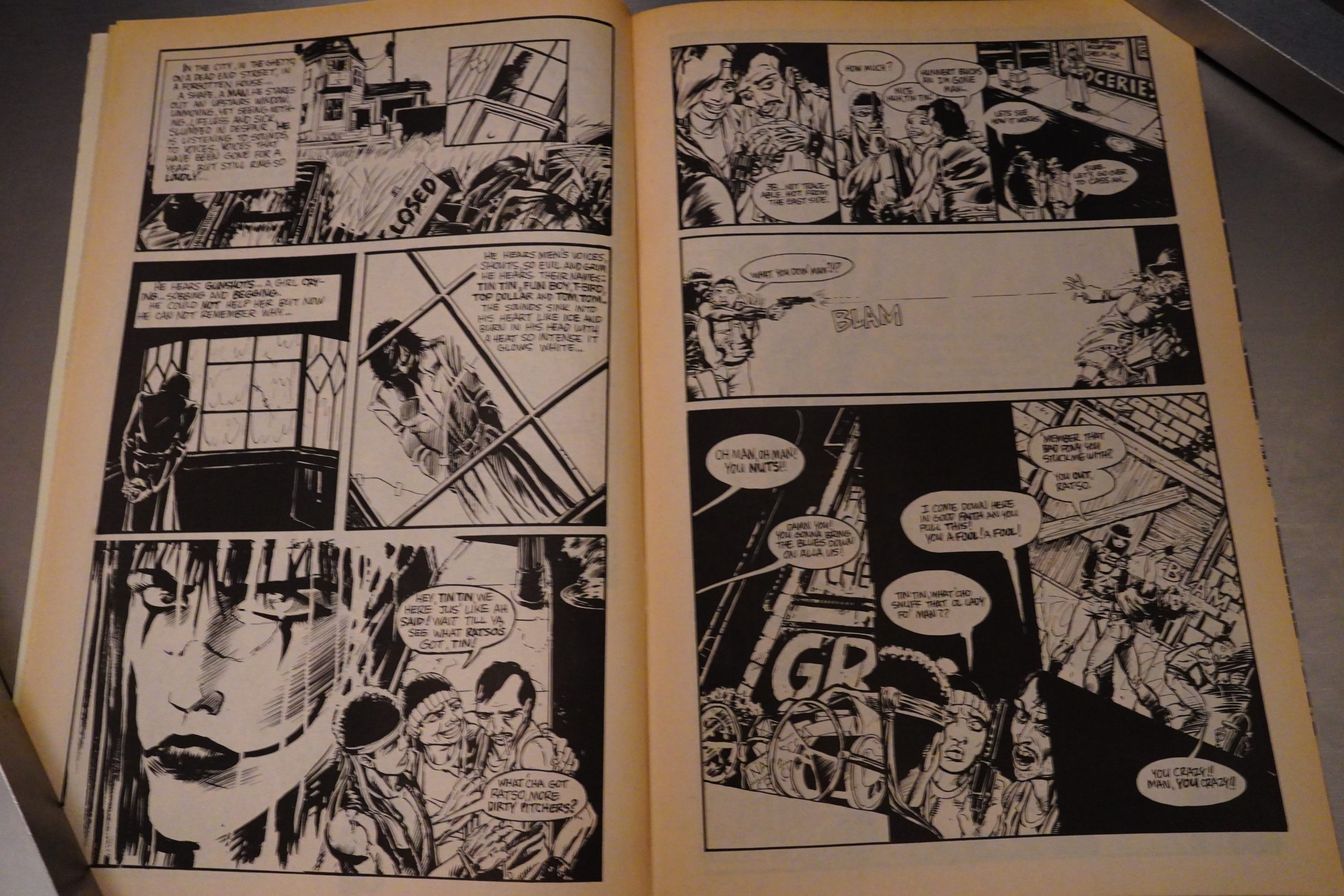

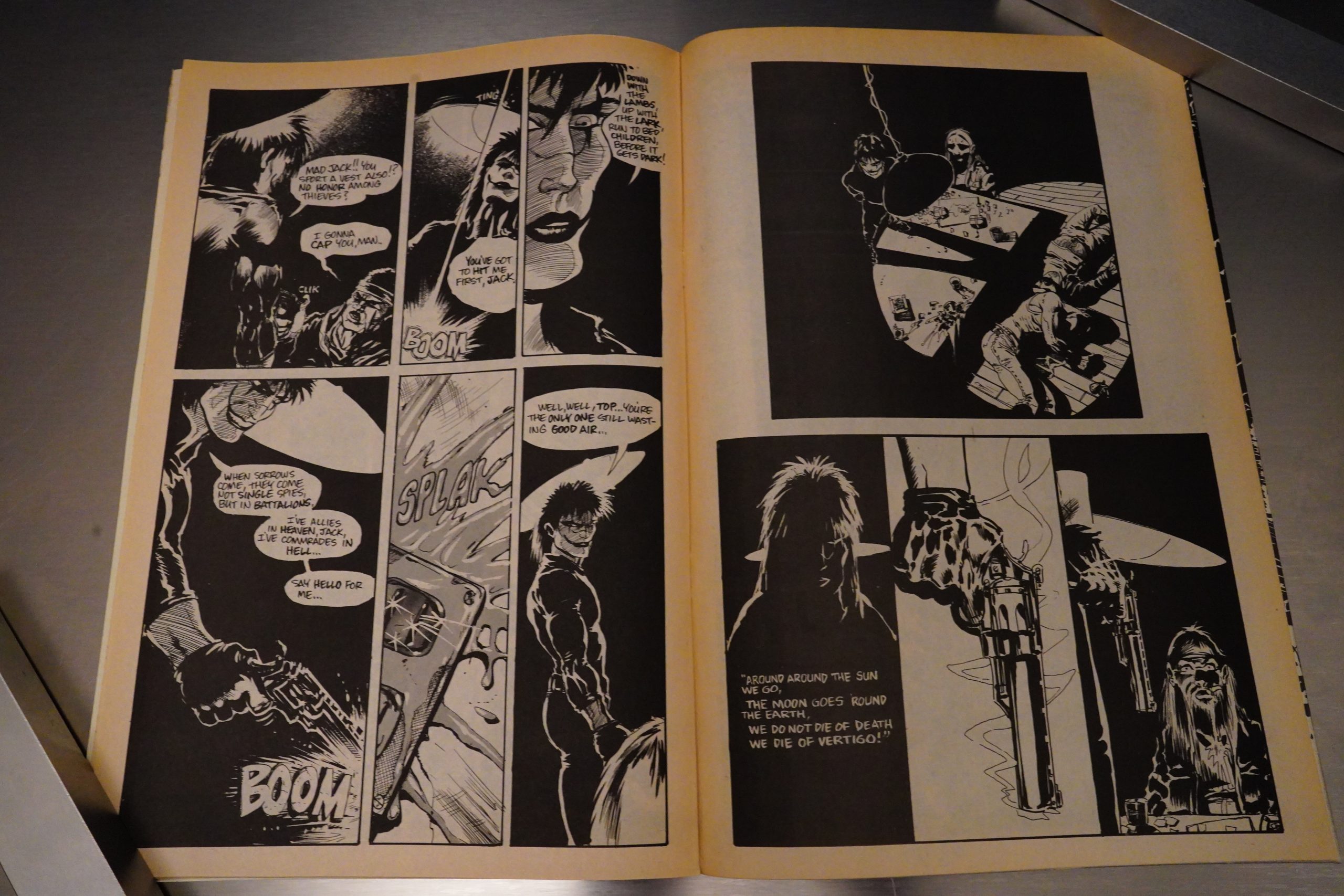

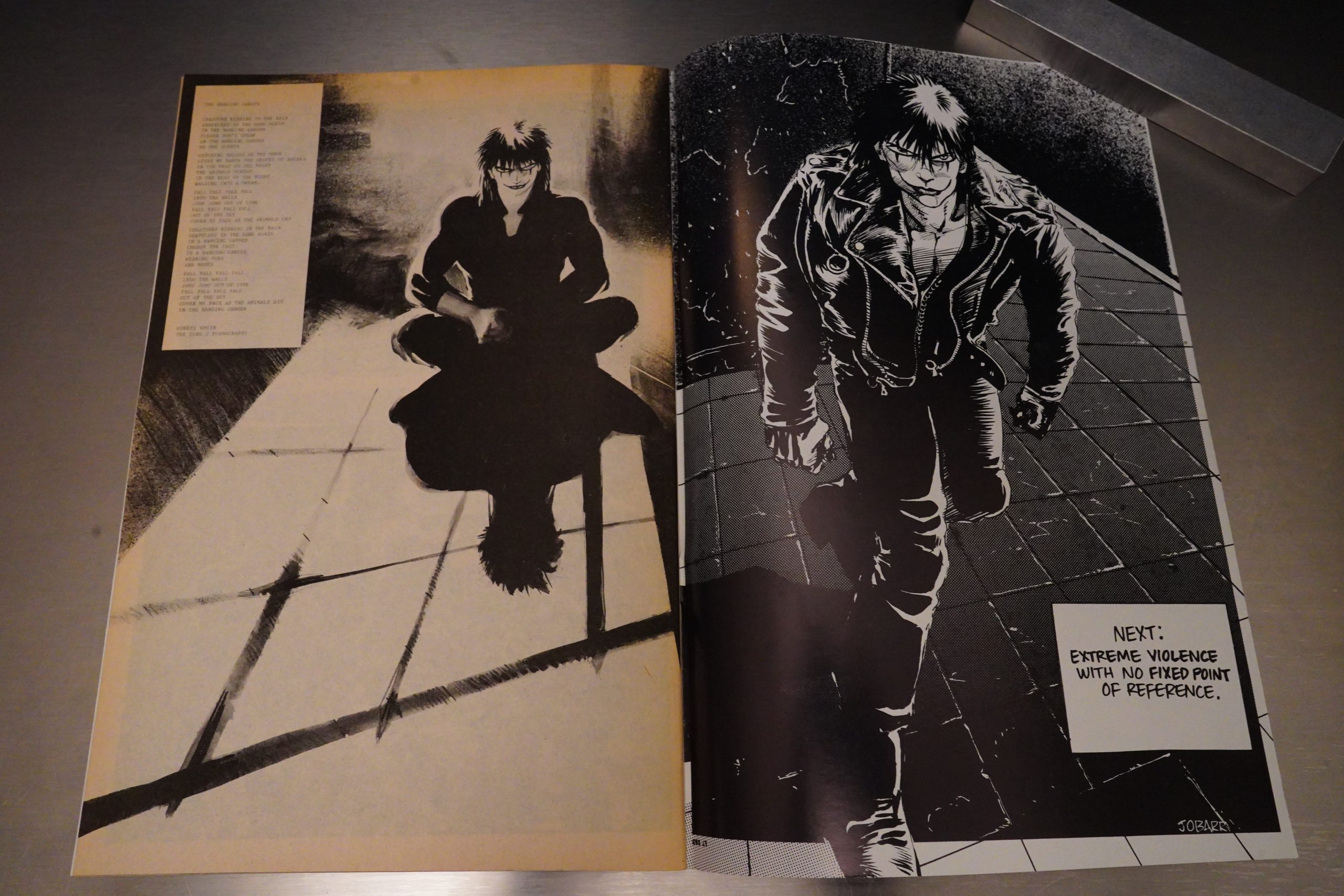

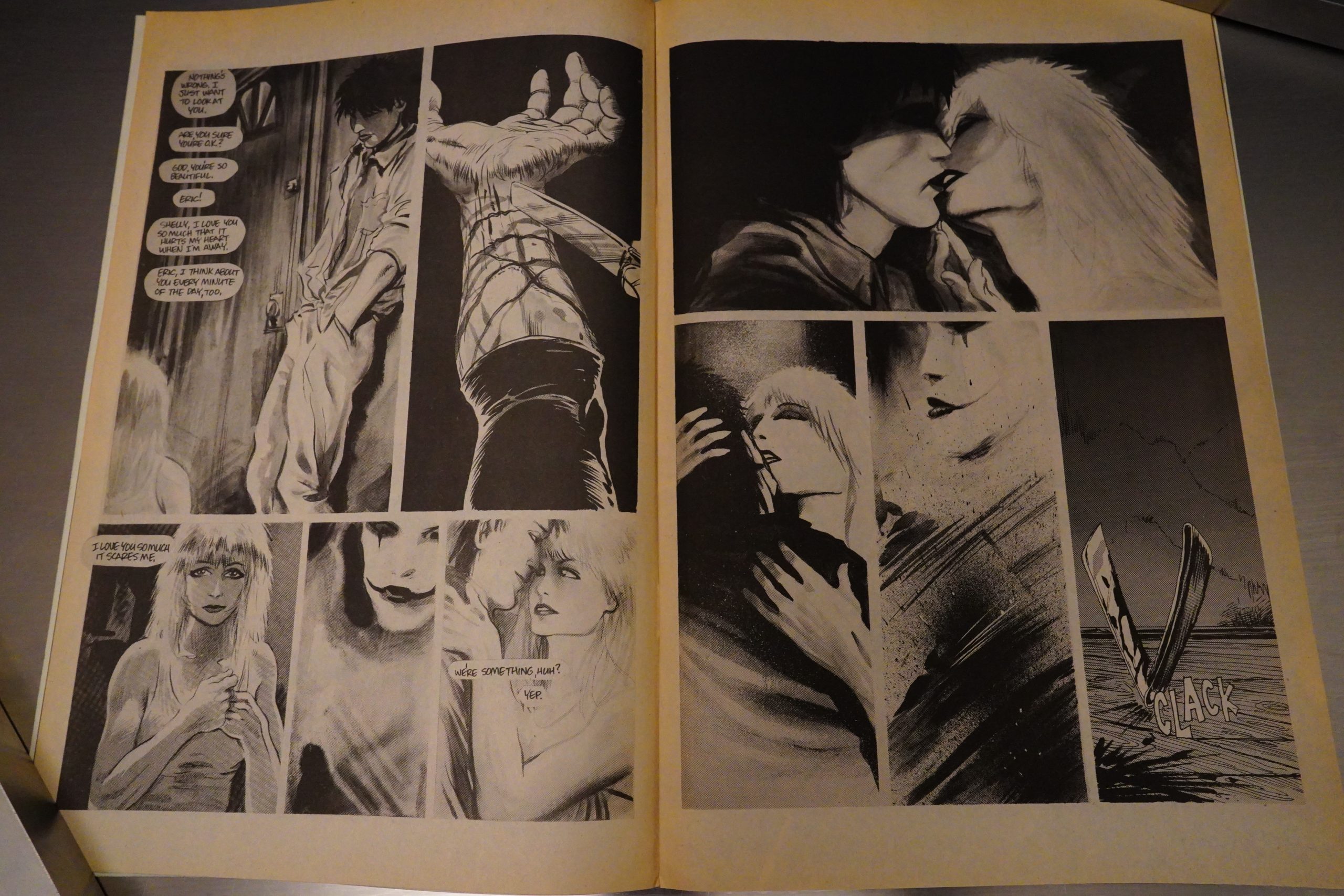

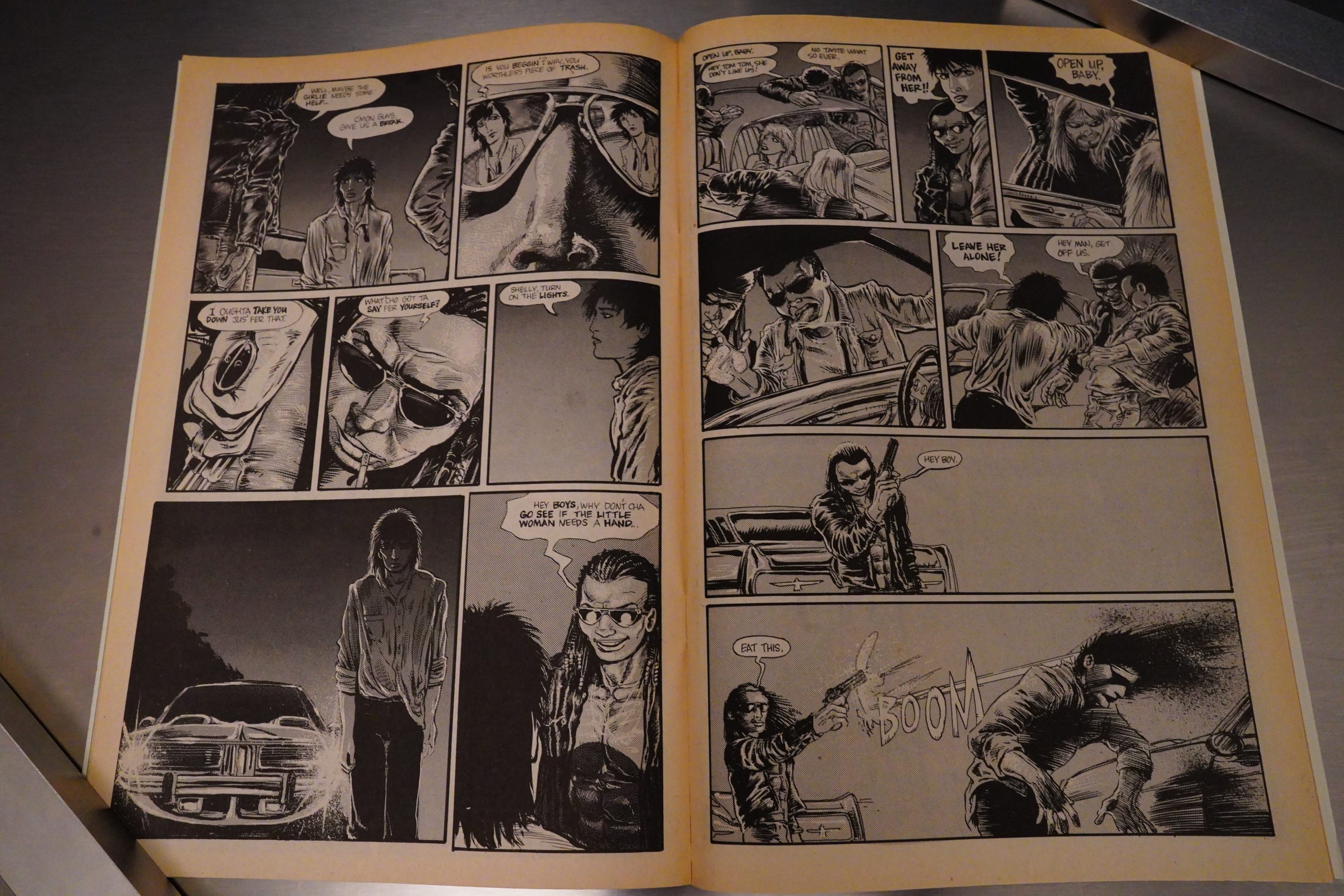

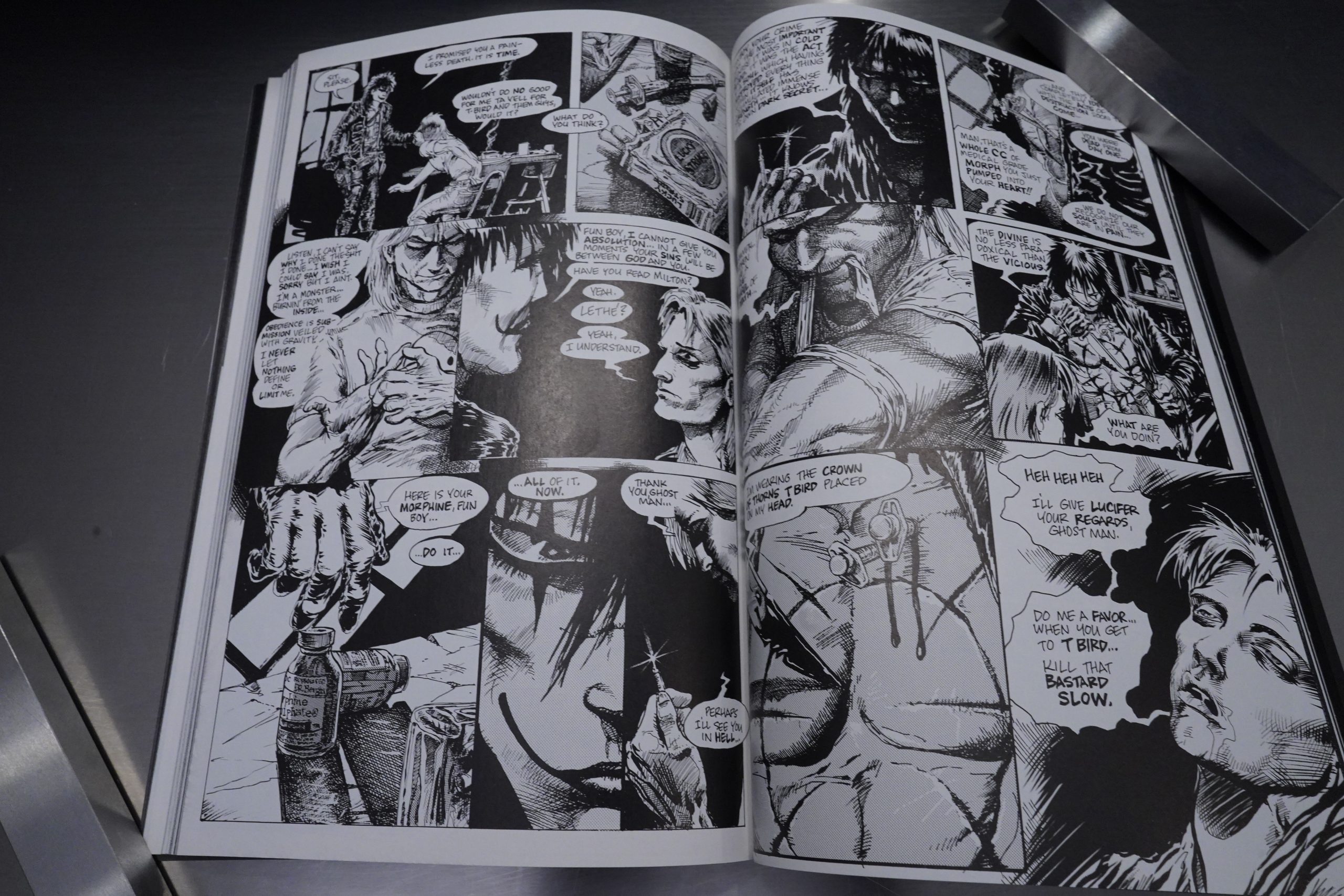

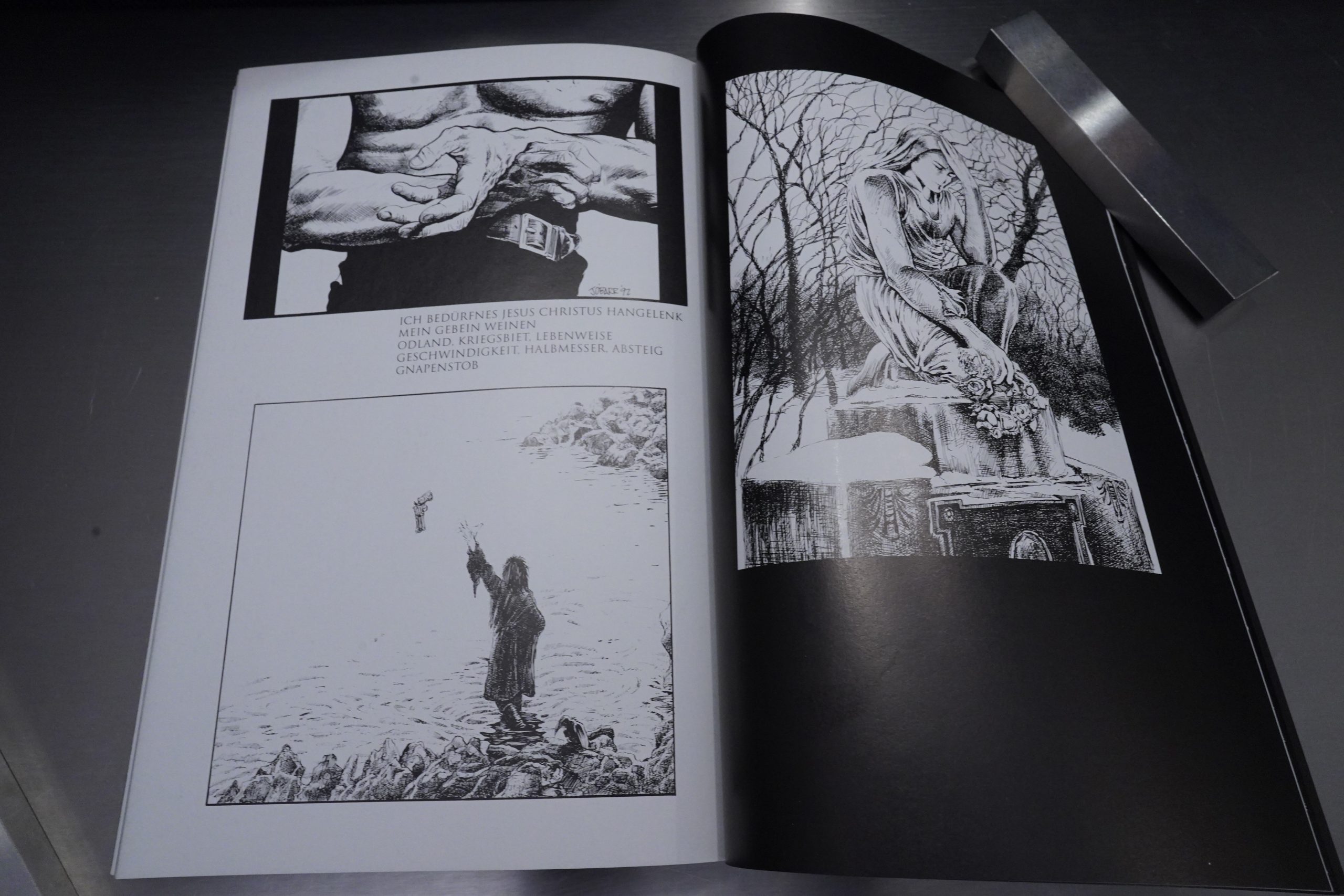

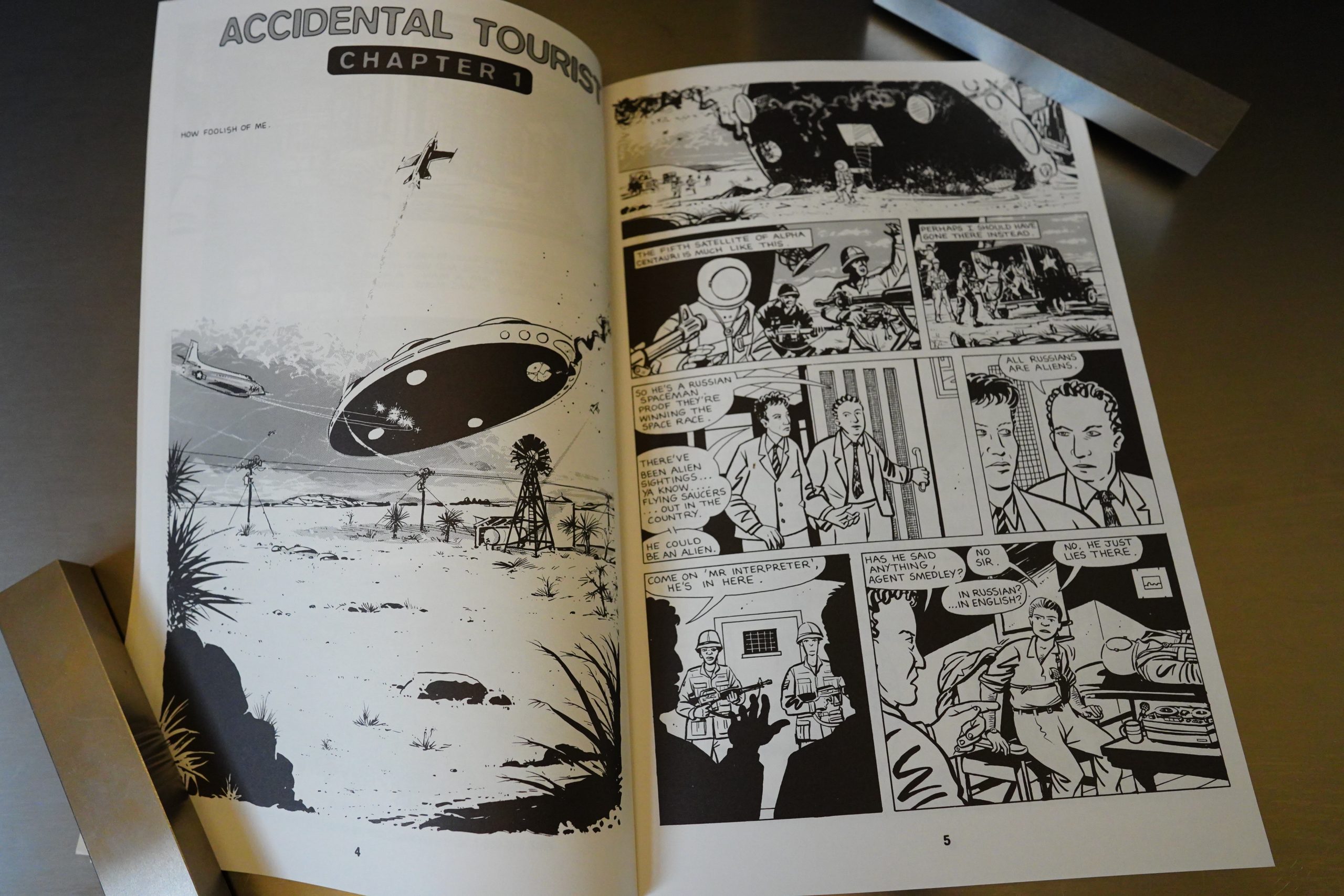

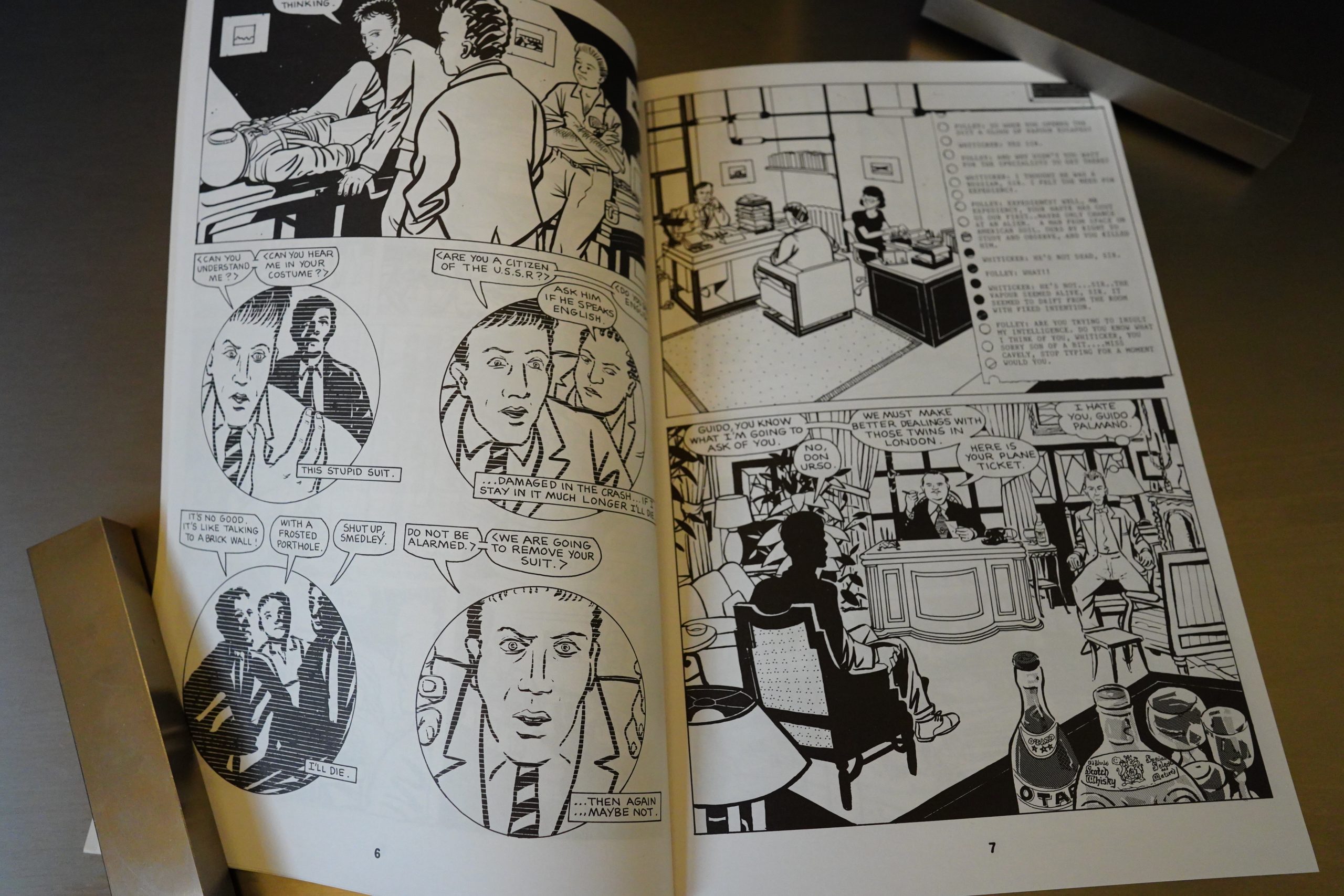

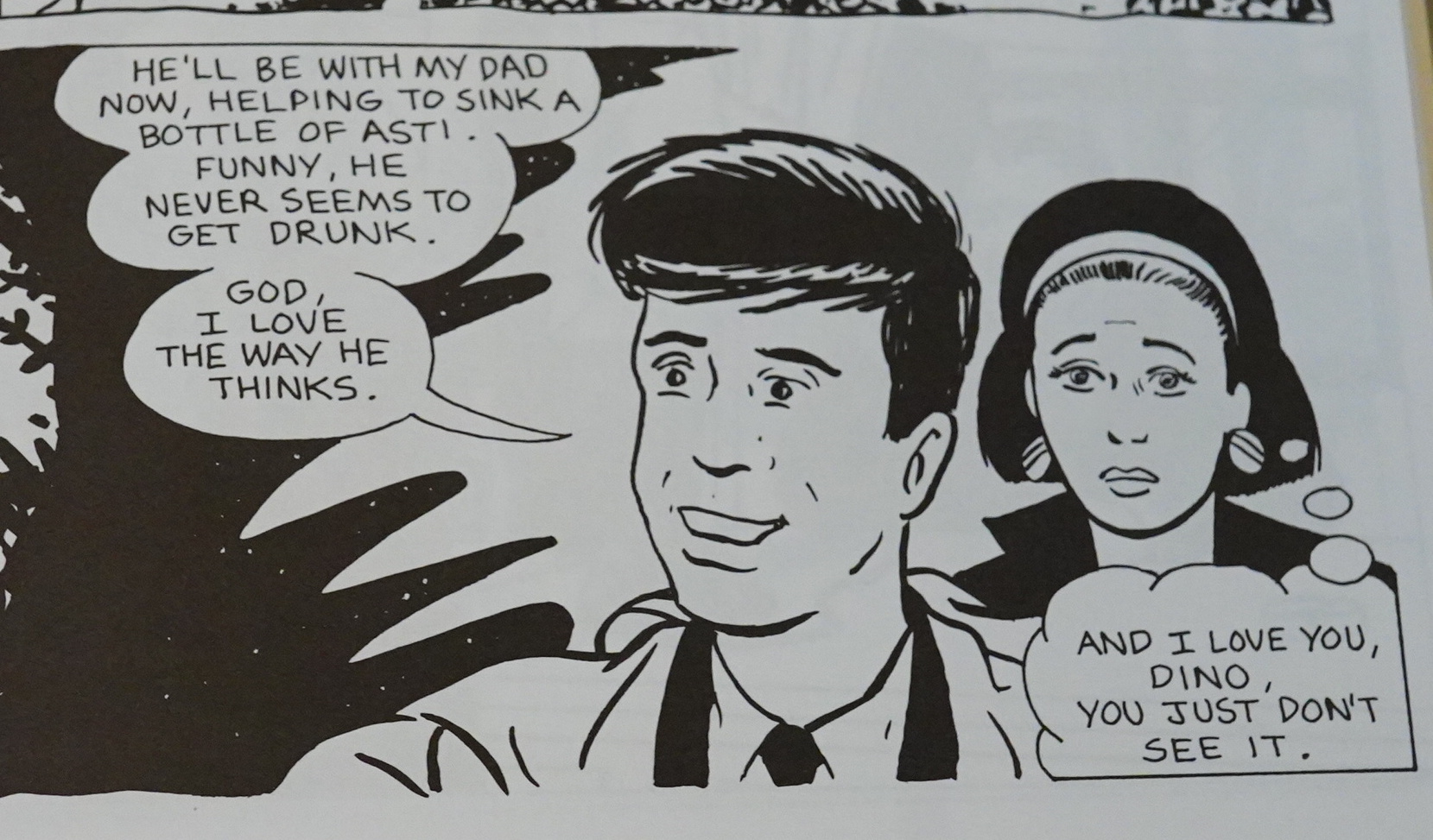

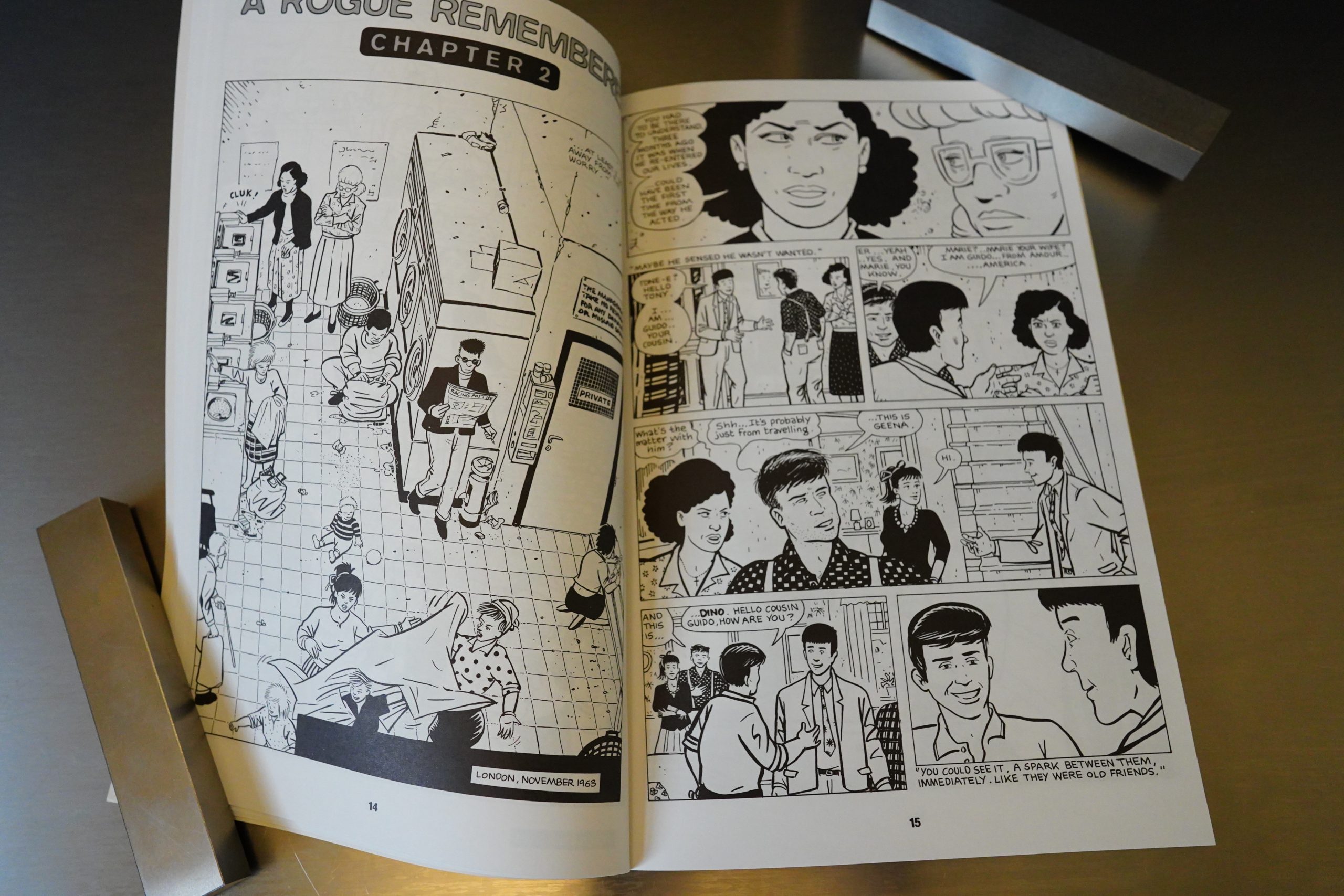

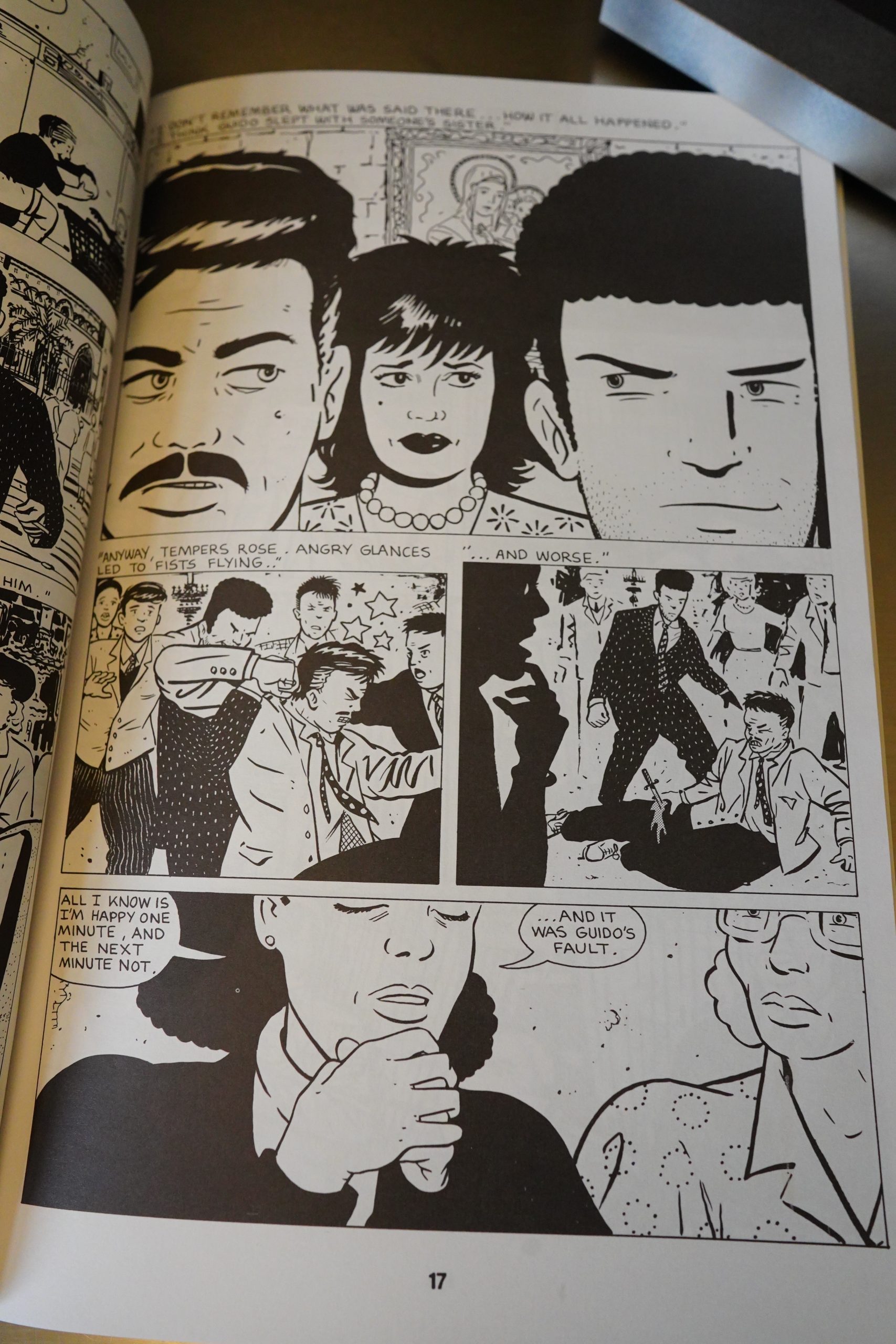

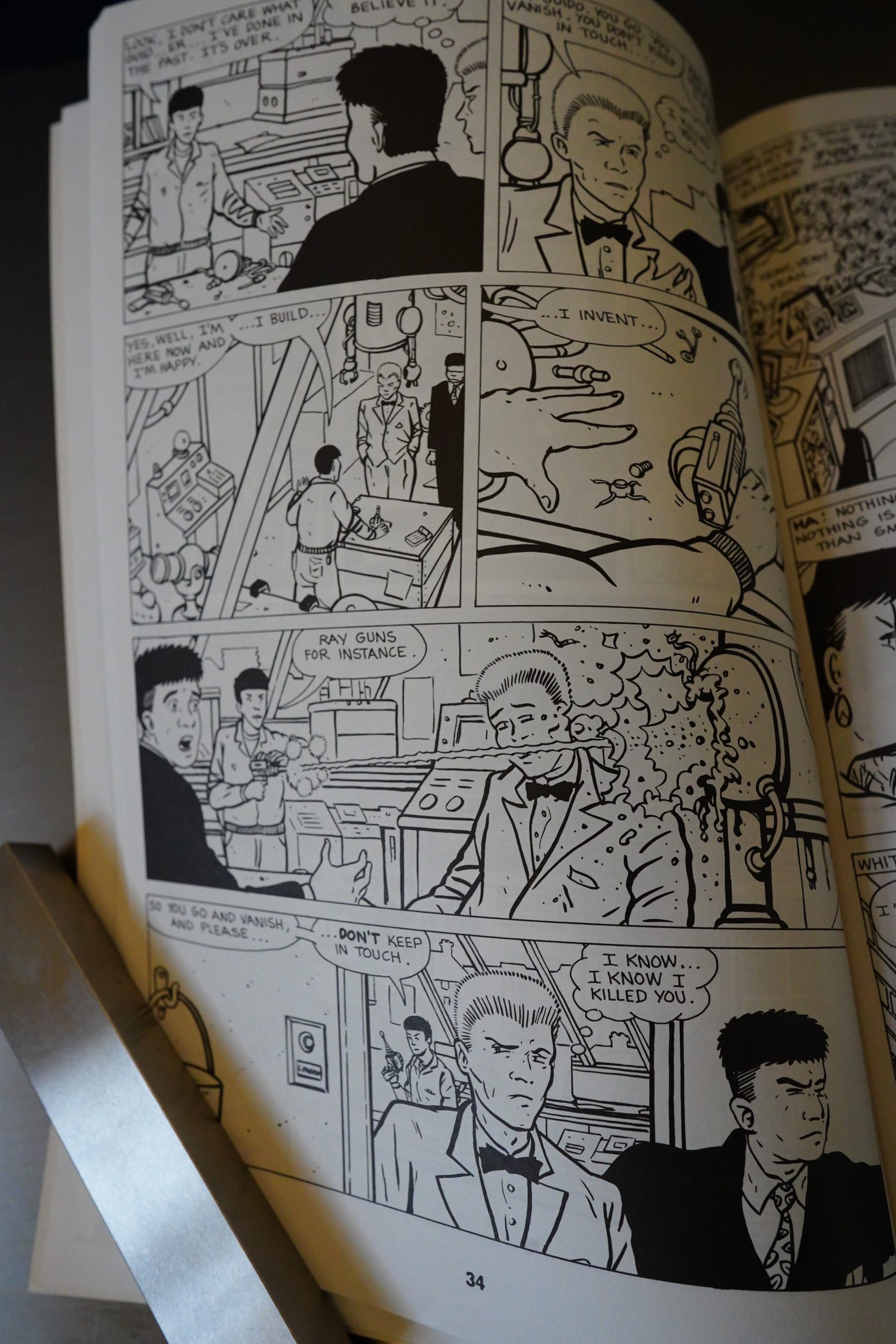

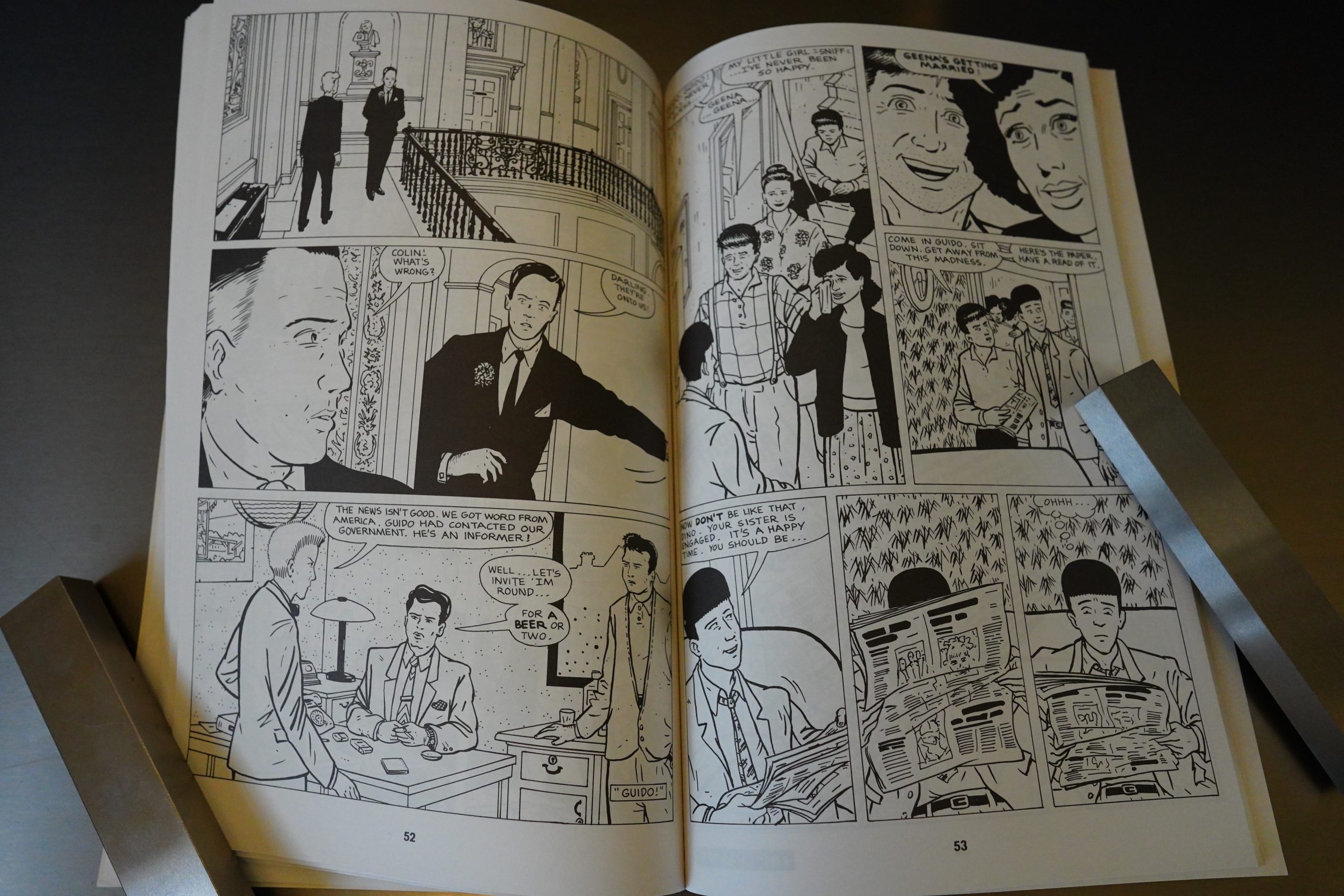

… but reading the book, it’s a kinda sorta overview of Toth’s career. But in a very vague way. We’re presented with a few odds and bobs that Toth has illustrated, and a couple of them are reproduced in full…

… like this badly reproduced CIA-financed pamphlet. (Toth doesn’t say how he came to work for the CIA, because… er… well, perhaps he didn’t even know that it’s a CIA publication?)

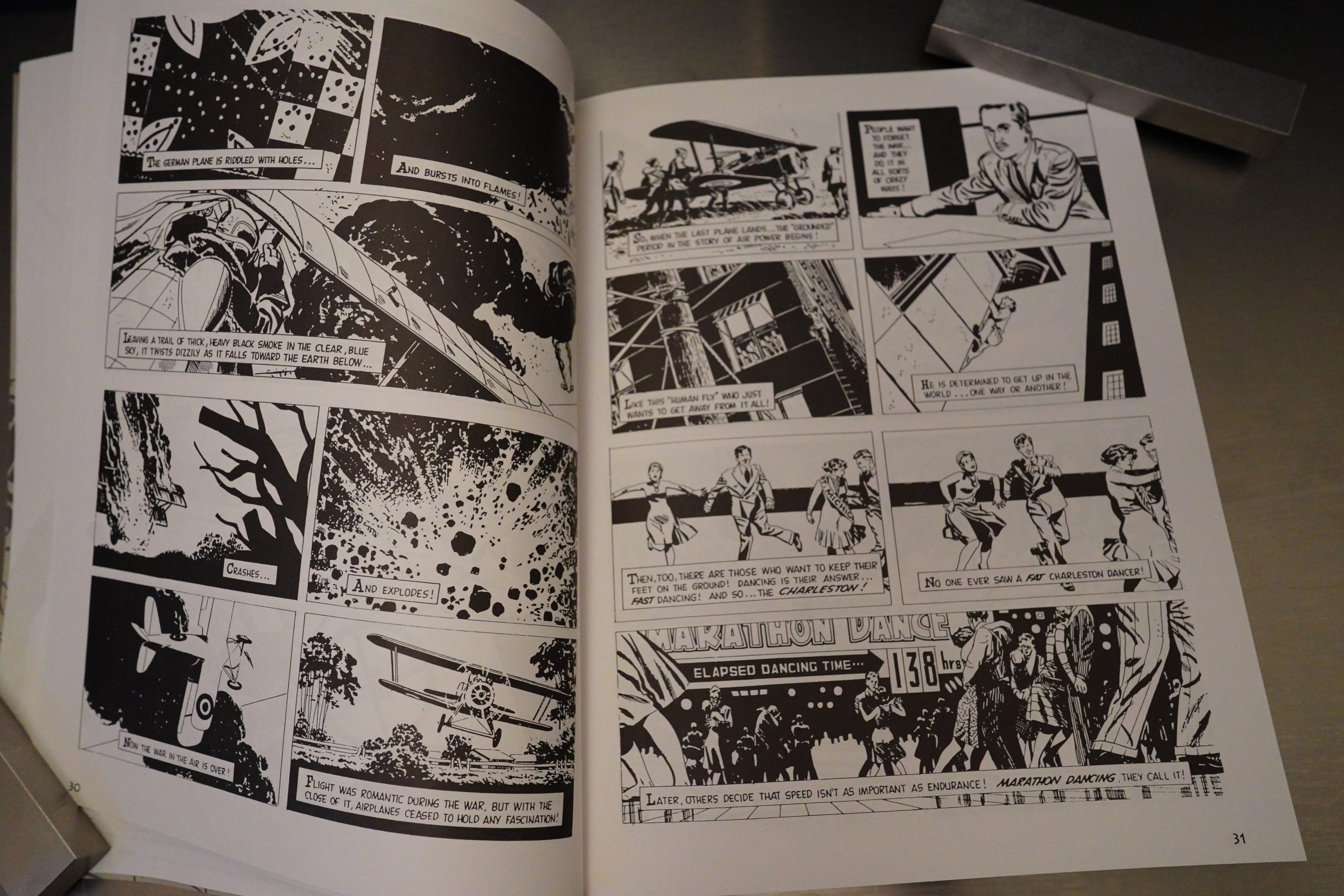

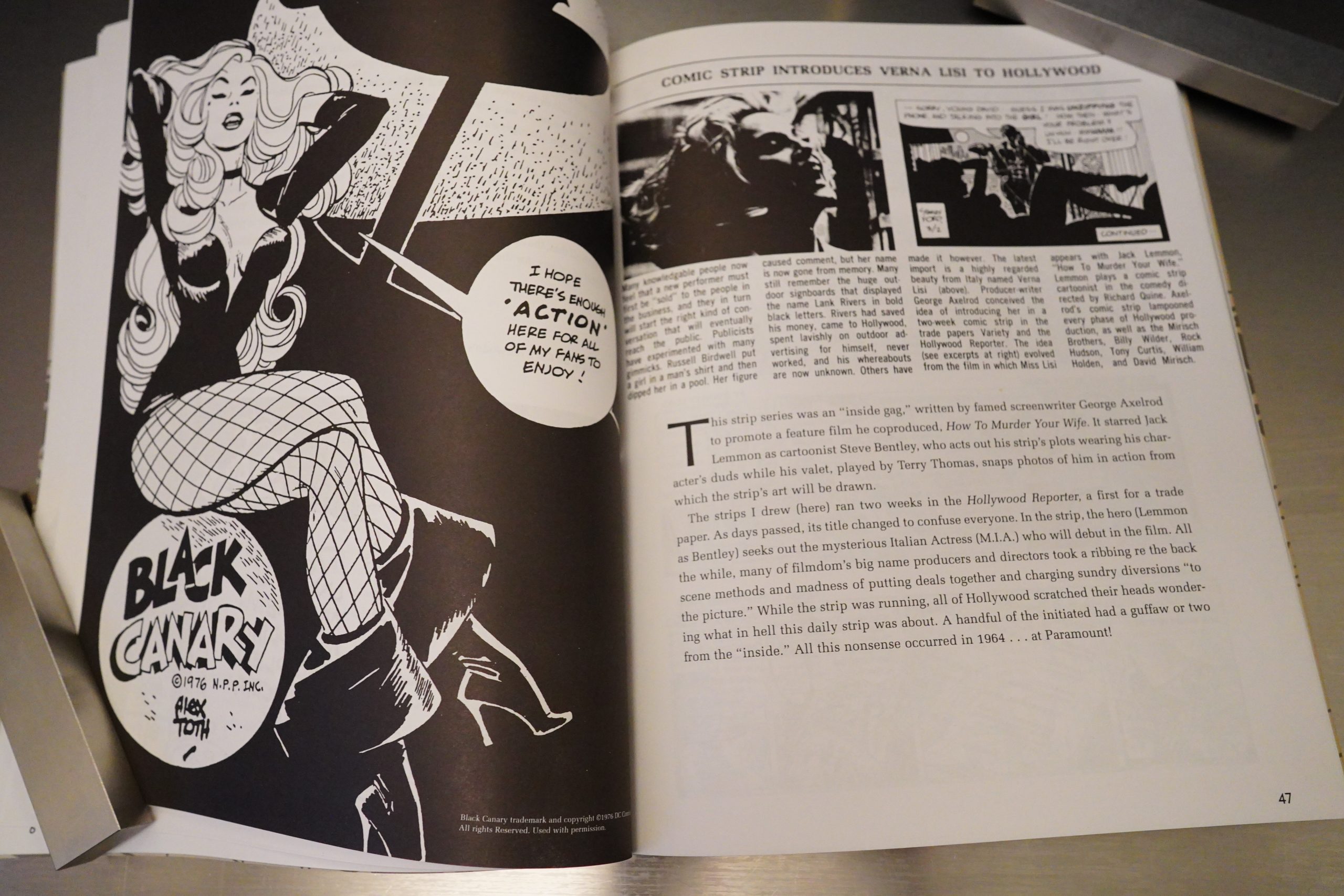

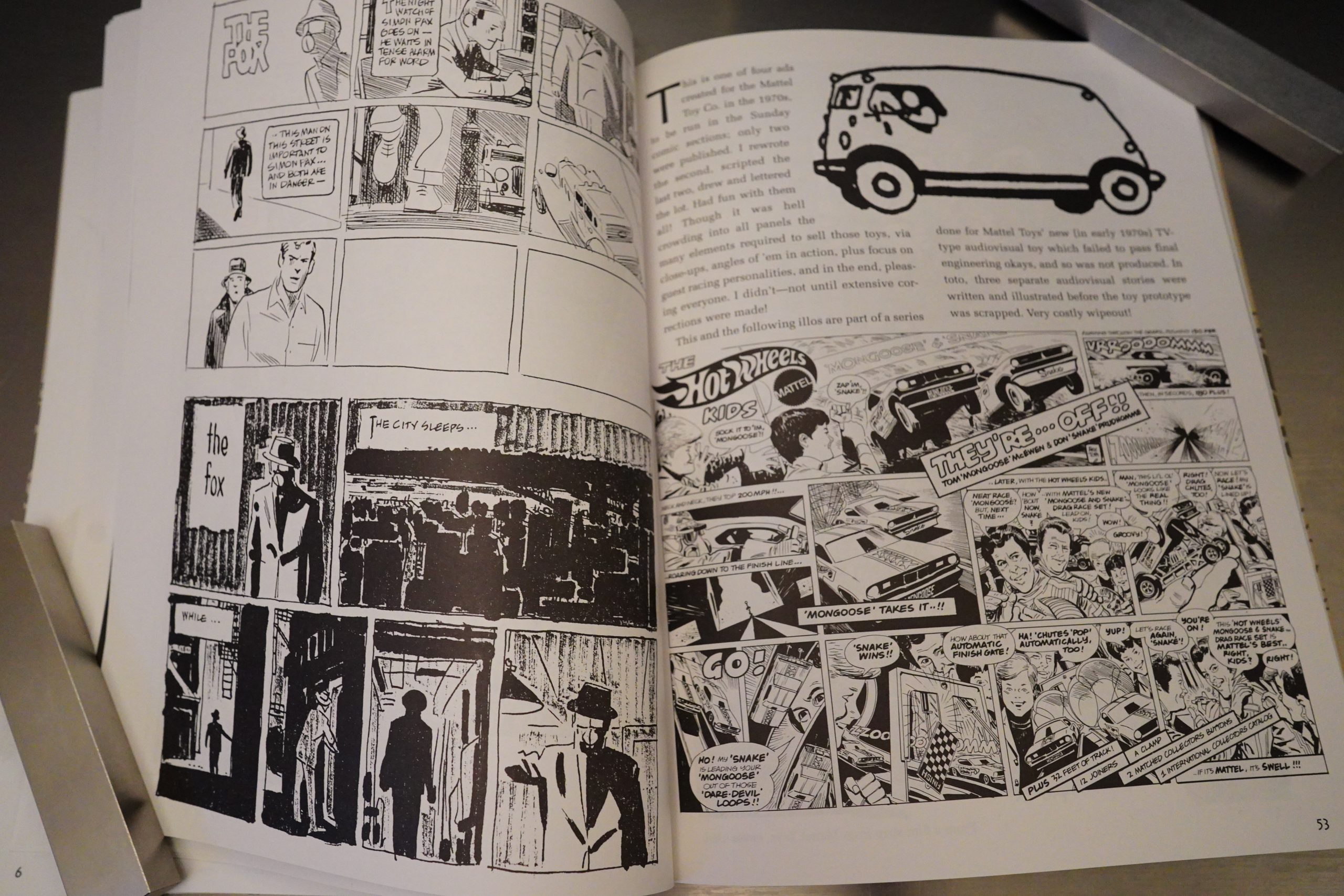

Similarly, we get other random illustration jobs he’s done.

And some of them are very random ideed, and the introductions are very helpful.

But as with virtually everything Toth has done, the artwork is good, but the stories are either hokey or barely there at all.

Toth is a very influential illustrator, and amazingly talented, but he has an unerring sense that draws him exclusively to illustrate pap. I’m not sure he’s even actually done something that’s actually a memorable read? If he has, I’ve forgotten.

(See, that’s like a joke, in that it’s structured as a joke, but not actually funny.)

Much like Toth’s own gag strips.

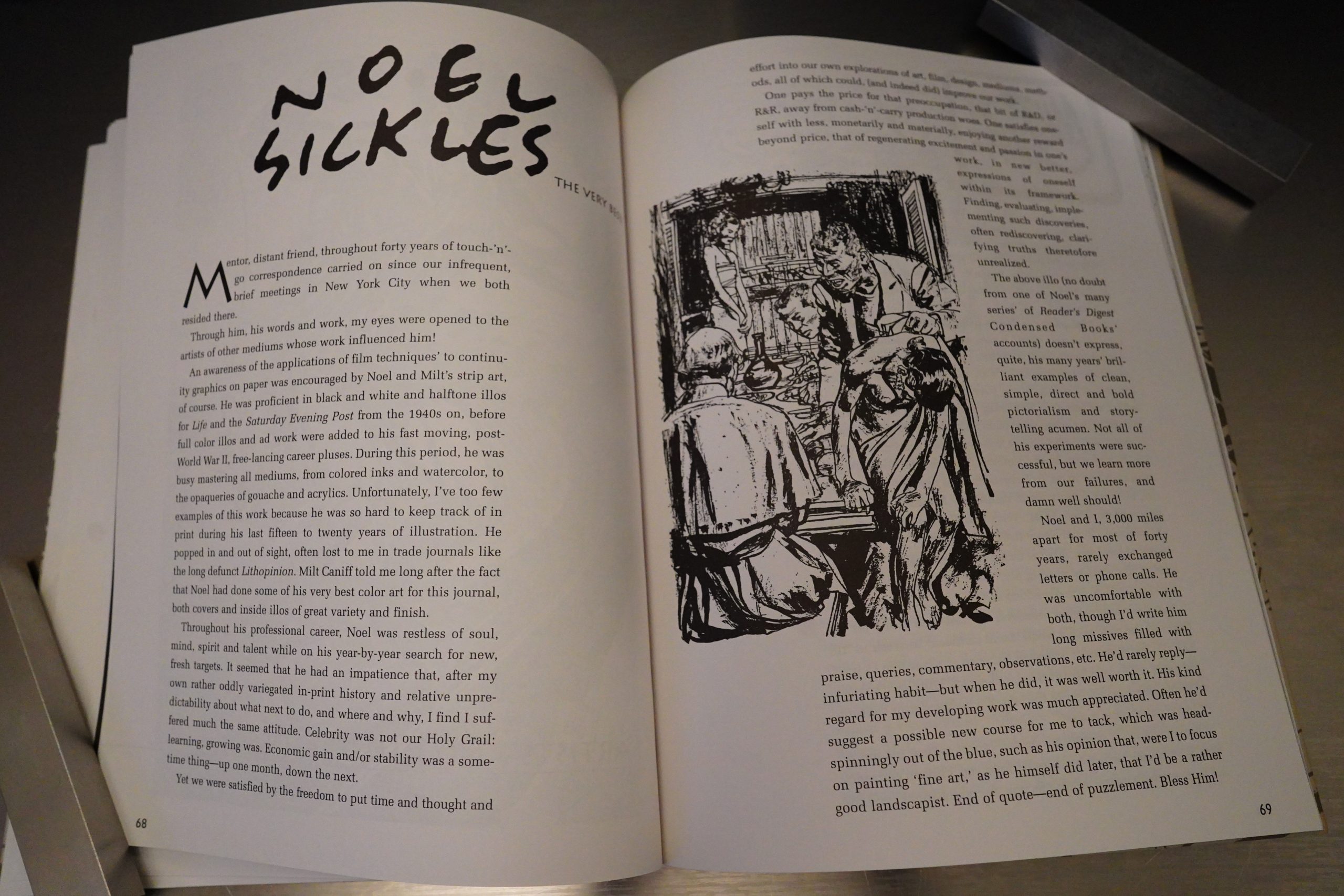

And then we get a long section of illustrators Toth thinks are swell.

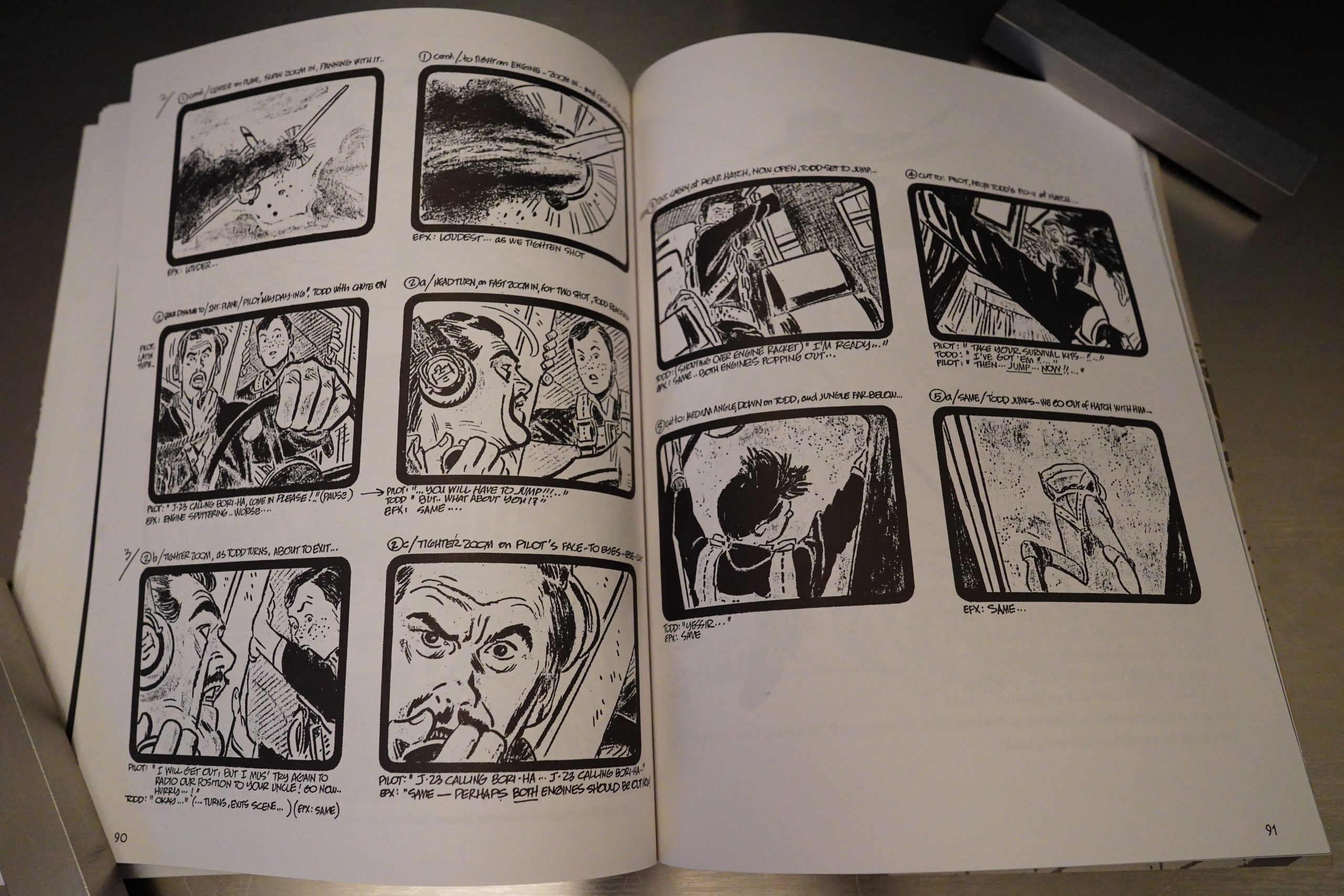

And storyboards.

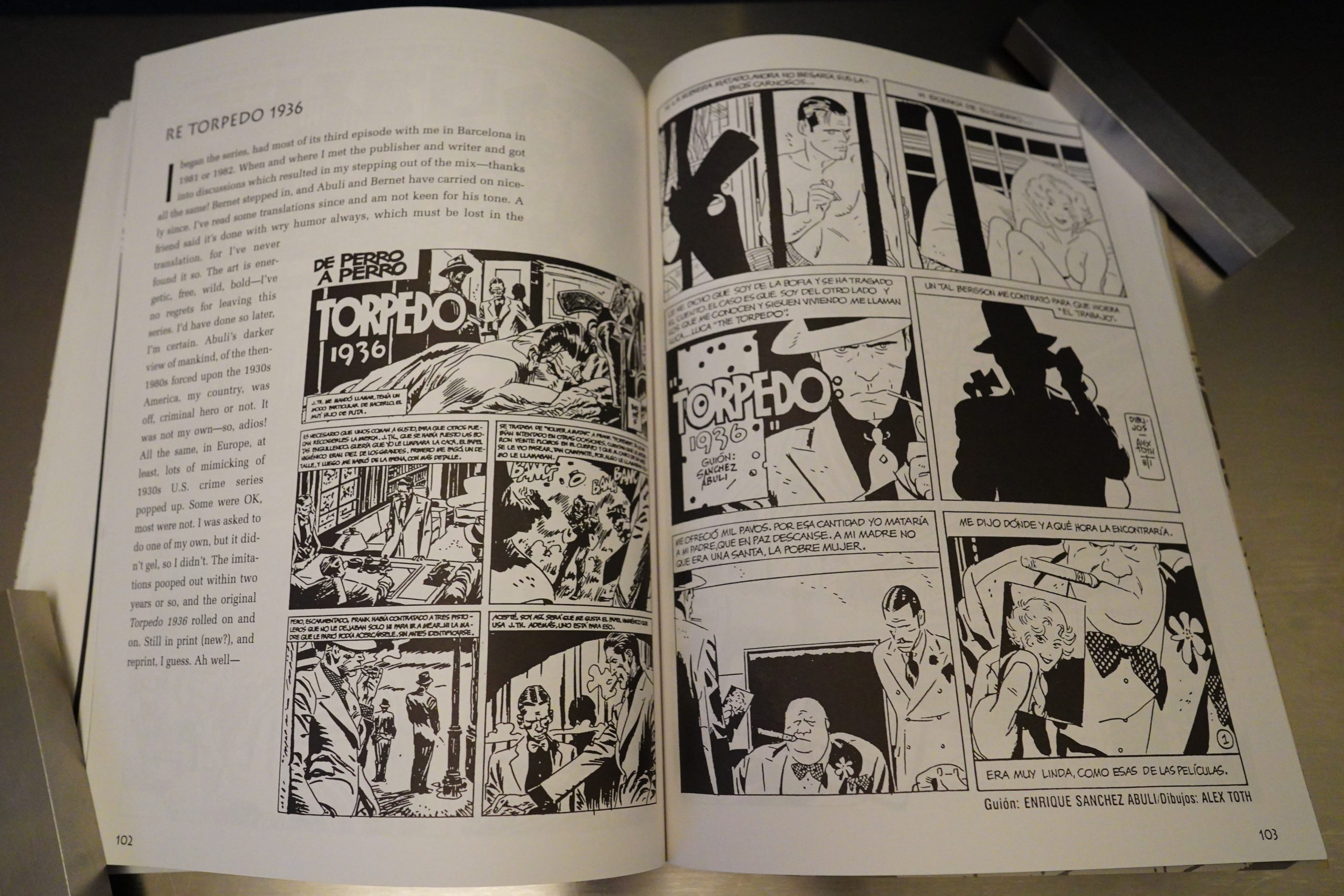

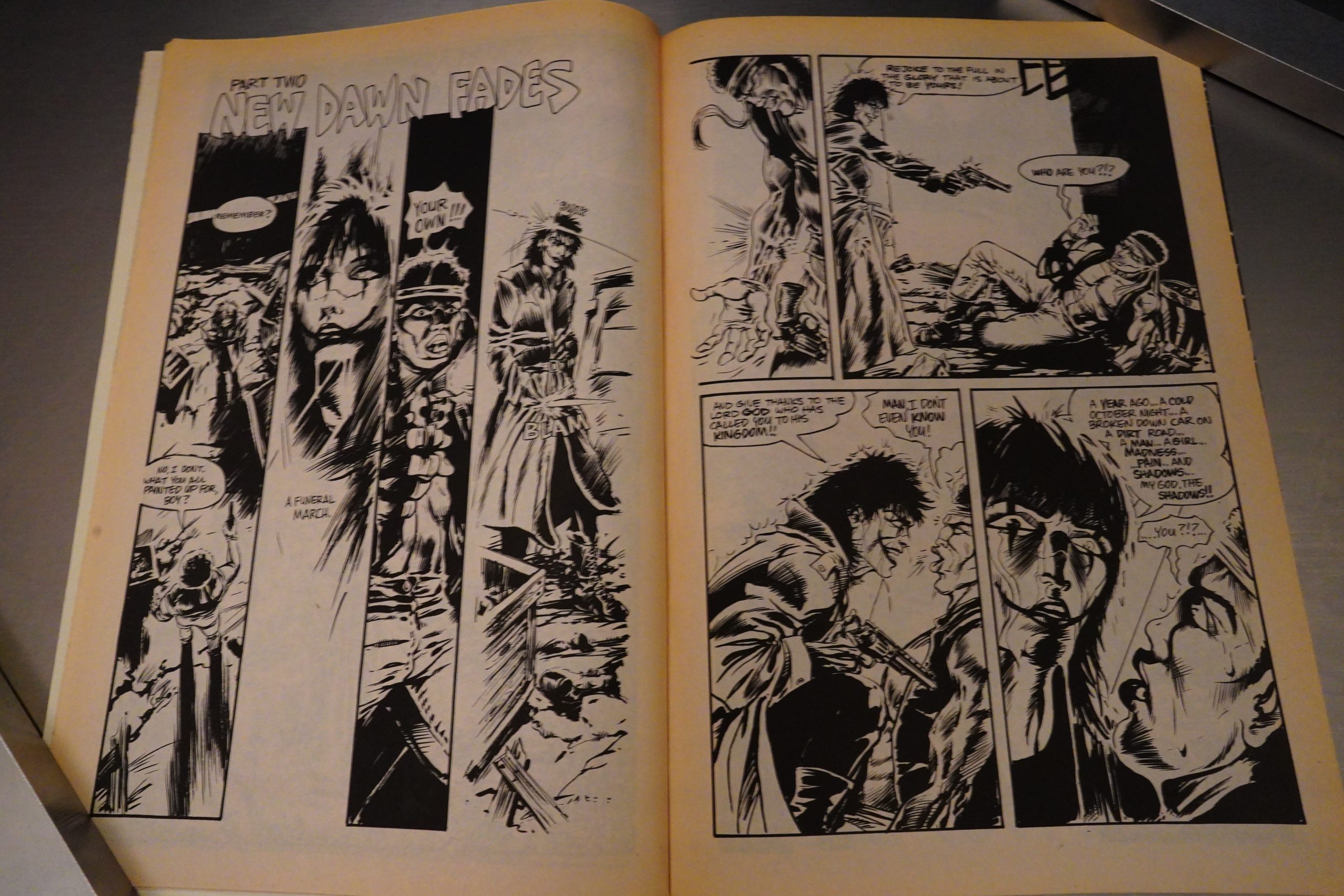

Oh, right, he illustrated the first couple of Torpedo 1936 episodes — those are actually good. And he left that, of course, and doesn’t think much of it, because he found it repugnant (I’m reading between the lines here).

And even here, the reproduction is horrible! Surely they had access to better material than this?

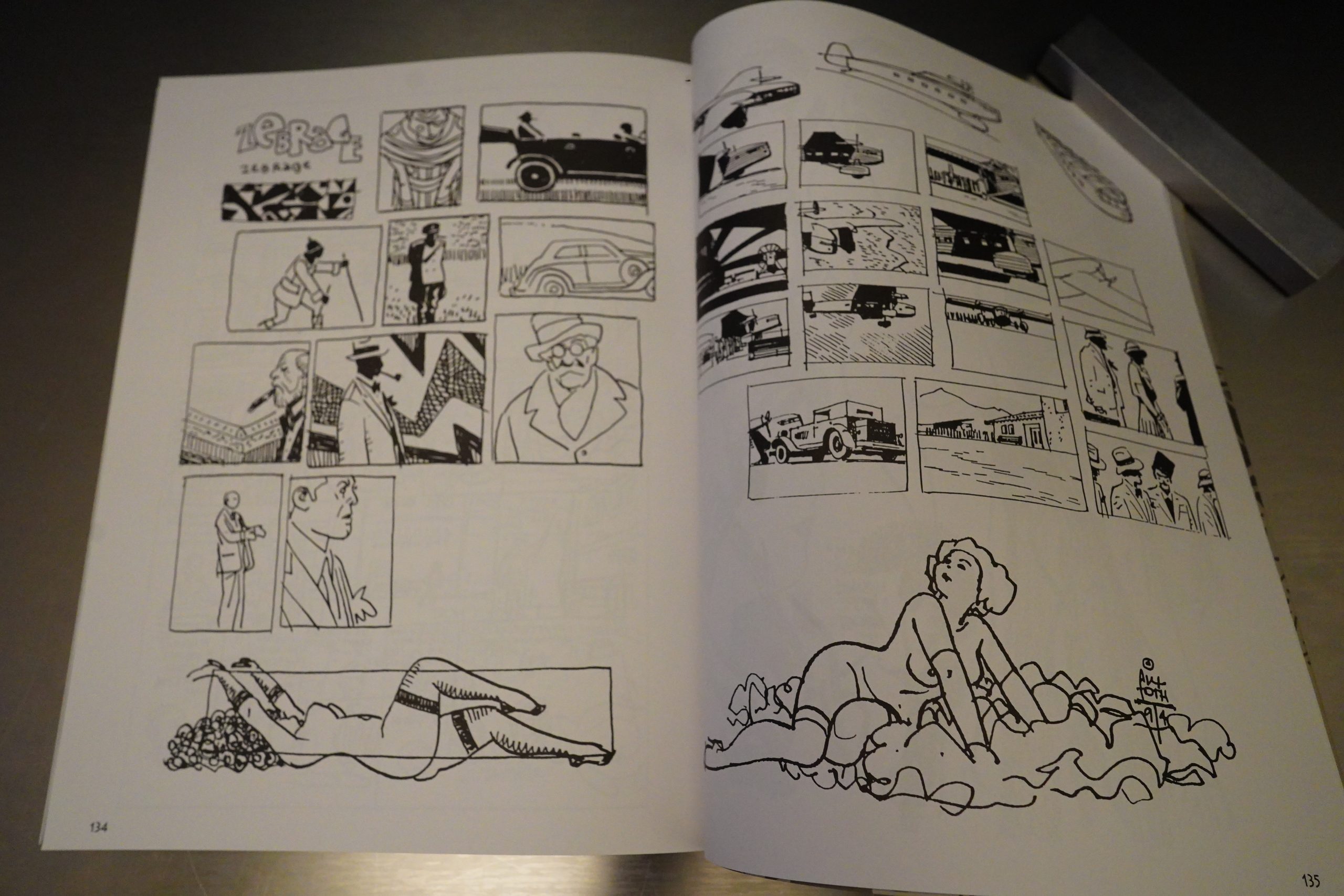

And then there’s some sketchbook stuff.

So what is this book? It’s like visiting Toth and having a peek through his archives, while he’s chatting a bit, I guess? And that’s probably a lot of fun for die-hard Toth fans, but for the rest of us, it’s a bit… er… not very interesting, really.

Toth is interviewed by Gary Groth in The Comics Journal #277, page 21:

I don’t think I realized to what extent

Toth refused to countenance opinions with

which he differed. I happily sparred with Gil

Kane and Burne Hogarth, two artists Toth

despised, incidentally, who were every bit as

principled and opinionated as Toth, but who

never took such arguments personally. Toth

did.

Following is my last conversation with

Alex. He agreed to an interview and I called

him up with the hope that we could get

started. I expected (or hoped) that our initial

warm-up conversation would segue into the

interview proper, but it was, sadly, derailed

before we got there. He said he was not in a

very civilized mood, and I suppose he was

right. Here’s a glimpse Of the man at his fierc-

est, most unmediated, and combative — typ-

ical of many of our conversations and of his

take-no-prisoners conversational style.[…]

GARY GROTH, There was a nice book that came

out about you recently.

ALEX Yeah, full of typos and all kinds of

fuck-up s.

GROTH, Jokingl:You should have reviewed it

for us.

TOTH, Review my own bloody, so-called

book?

GROTE-I, [Jokingl:Yeah, you could have torn it

to pieces.

TOTH, Well, first of all, it really wasn’t my

book. It was Manuel Auad’s book, and those

bastards at Kitchen Sink did not send him a

proofed copy. That’s why those damn typos

and glitches and lousy color separation on

the cover existed. And then they screwed ev-

erything up even more by copyrighting the

damn thing in my name instead of [Manuel

Auad’sl, so there’s a lot to be desired in this

publishing thing, and I don’t think I want to

dance that tune again.

GROTHt Well, I haven’t actually sat down and

read it. just looked through it, but it looked

handsome, We actually have a review in the next

issue Of the magazine. I’m sure you’ll love it.

TOTH, Yeah, R. C. Harvey’s. Yeah, he was very

gentle. He didn’t note all of the typos and

misspelled well-known names.

GROTTI, Well, I cut all that Out Of his review.

TOTH, Oh, you did?

GR(YI’H, No, I’m just kidding.

TOTHt Well, he could have cited it because

I think Kitchen Sink’s editor needs a good

bump on the head for what he did. He used

his own editorial judgement, which was

wrong in every case.

GROTH: You think it was just sloppiness?

TOTH, Well, they complain about not [hav-

ingl enough budget for more proofreaders.

Well, hell, they had two free, absolutely

free proofreaders right here. Manuel, he

would’ve done it and then he would’ve sent

it down to me to double-check again. And I

would have sent it back and it wouldn’t have

cost them a penny. And it would’ve been cor-

rect and I would’ve caught omissions that

were glaring. There was no reason for what

they did; they fucked up some of the pages,

the arrangements of them, and omitted stuff,

Manuel had submitted like 180 pages, and

they cut it down to 144 and I think most of

those pages were the doodle pages, which

everyone who’s called me or written me

has said, “Gee, I wish there had been more

doodle pages.” Well there were. There were.

And some asshole editor decides on his own

hook, whether by pressure of other work-

loads, Which I heard was the big complaint

— “Well, gee, we got so many books to do

here, you know, we don’t have enough peo-

ple todo them.” Well, Christ. That’s no alibi.

Alibis just don ‘twork: it’s wha€s in print that

counts. I don’t want to hear anybody’s sob

story. It’s what’s in print that counts: that’s

what talks and walks.

GROTH, Well, that’s damned unfortunate. I

forget W’hat the book costs but it seems like they

could have made it a larger book andjust.

TOTH, Thirteen [dollars).

GROTH, They could have made it a larger book

and charged $15.

TOTH, Well, firstofall, ithad very little, ifany,

promotion. I was getting Manuel to [push

them] way back in March oflastyear because

they were sitting on it for a year, to get them

to get it ready for the big San Diego con. If

you’re gonna debut a book, debut it there.

And if the thing has got any value at all, word

of mouth will make it sell and they’ll have a

pretty good temp reading as to whetherwe’ve

got a dog or if we’ve got something that will

fly. So, no, no, they knew better. They knew

better. so they fucked around With it until

the end Of the year and that’s when it Came

out. And it was just a total botch.

GROTH, Did they cut it down with the editor’s

permission? Manuel’s or

TOTH, I think he caved on some of the stuff,

but I think they did some more. The most ir-

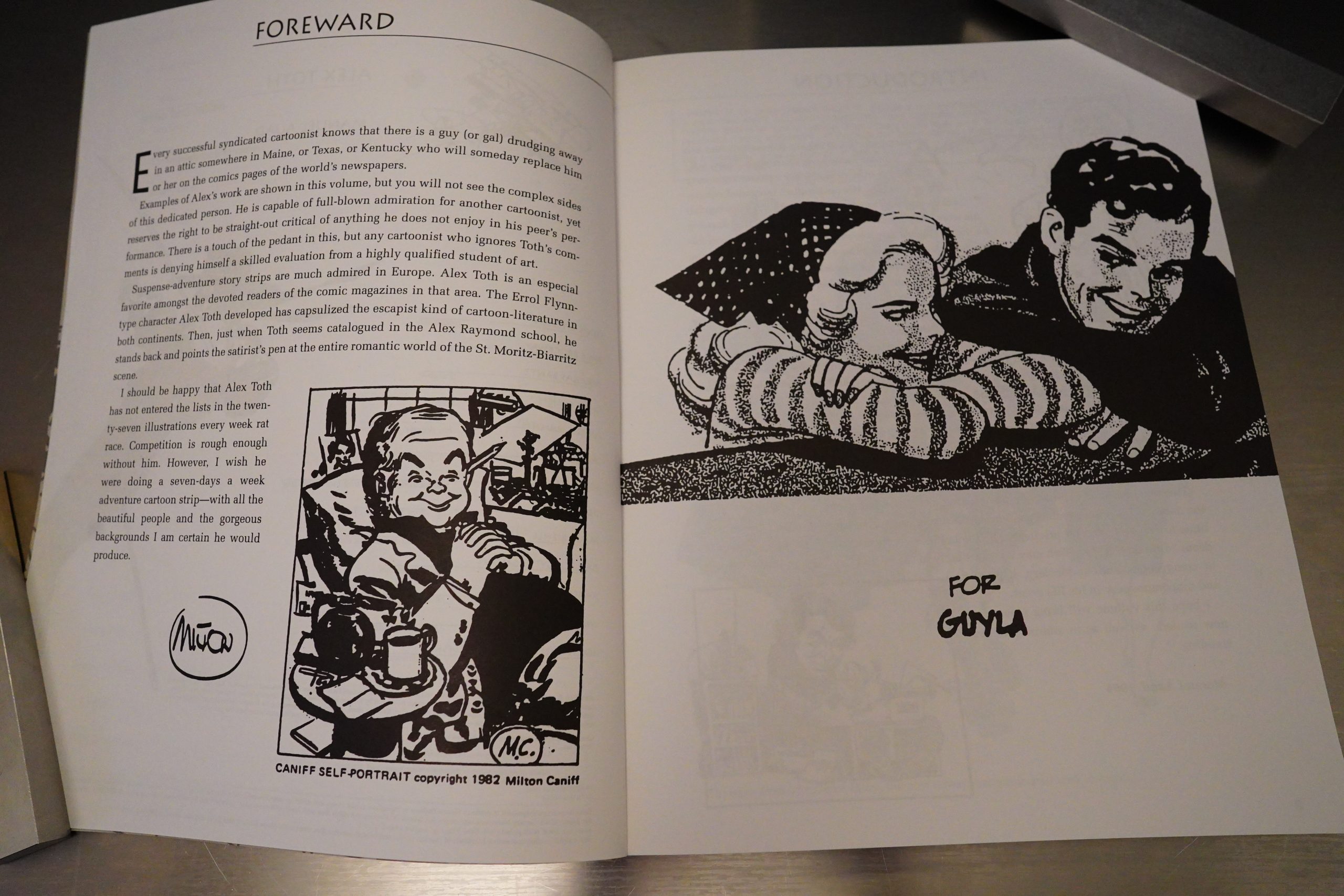

ritating — first of all, I hand-lettered all my

stuff and they converted all that to type.

GROTH, They did?

TOTH, Yeah. And they convinced Manuel that

was the best way to go because my lettering

was uneven, and I’ll confess to that Yes it

was. But it was there and it was in my hand

and they couldn’t fuck with it if they would

just reprint it as it was done. Another thing

that really pissed me off is that the letter that

Milt Caniff wrote to Manuel, for some god-

damn reason, don’t ask me why, I can’t figure

it out, and I haven’t got a copy of the letter

handy now. it’s buried under tons of crap

here. They chopped off the opening and the

closing paragraphs Of that letter, for no god-

damn good reason. They have no right to do

that That was a communication written ex-

pressly for the proposed book that Manuel

had in mind for years, and they didn’t even

know about it

GROTH, They did that without Caniff’s knowl-

edge?

TOTH V/ithouthis permission. I mean, there

it was. It’s gone: the opening and the clos-

ing. And they set that to type too when his

original note with crossovers and etceteras

would have made it much more personal and

genuine because I was getting very strange

phone calls from guys saying, “How come

a dead man has just written a forward for

your book?” And that wasn’t very funny,

and that’s the position that we were put in

because Milt always dated his notes. His jot

notes, you know, his freehand notes and all

of his little typed notes. So the whole thing

sucked, you know. It robbed us of that little

personal touch which would’ve been much

warmer. And the same thing would apply to

whatever I hand-lettered on my own.

GRO-n-it It’s an academic question at this point,

but Why didn’t Manuel Past say, “do it the way

I submitted it”?

TOTH, Well, Manuel was a virgin. He never

did this before. This was his first publishing

venture. It was his idea to gang all this stuff

up Of mine and shoot it into somebody and

see if they’d want to do it And I can’t remem-

ber if he submitted it to Bud Plant or anyone

else before he shot it over to the Sink. I was

blowing in his ear and telling him, “Try this,

try that. Talk to these people,” and he was un-

known, so he was getting a fast shuffle from

everybody. “Who the hell are you?” you

know. And so, here he had the damn dummy

ready to go and then finally it winds up in the

Sink’s hands and they sit on the goddamn

thing for a year or so. It’s not their property.

They have no bloody right to do that Either

you move on it within a fixed amount of time

or forget it “Fuck you. You’re not the Only

publisher in the business.” The Sink was

undergoing its own strange transformation

with all of this crap, the merger, the buyout,

who bought who, I don’t care. With what’s

his name back there — and then moving,

physically, his whole operation to the East

Coast All of that got in the way and whatever

turmoil there was showed up in this book.

So Toth wasn’t happy with the book as printed. To say the least.

The Comics Journal #262, page 106:

Some of his break-ups seem leveraged

by demons whose consequences for the

man in their possession, as well as for

those they crash him against, make one

shudder — if not weep. Dick Giordano,

with whom Toth once sought to work,

heard himself denounced at a convention

as “the man who ruined comics.” When

Jerry De Fuccio, who had grown up with

Toth, was receiving chemotherapy, he

became infatuated with a nurse. Toth,

who had been calling and writing regular-

ly, announced, “You’ve got a family now”

and cut Off contact. Manuel Auad had

edited and published several Of •roth’s

books. Toth’s late wife had a son by a prior

marriage whose wife, like Auad, was

Filipino. On visits she brought pastries, of

which Toth grew fond. After his mother

died, the son stopped coming. Toth, who

missed the pastries, asked Auad for some.

Gradually, Over nine years, he began send-

ing Toth more and more ofwhat he

ed. “Frozen foods, underwear, chicken

thighs, cigarettes, you name it. But if any-

thing was late, there was hell to pay.”

Eventually this hell caused the two to stop

speaking. “Alex can be funny, generous, all

the nice you can think Of,” Awad

says. “Once my Wife fractured a finger,

and the next day two dozen roses arrived

from Alex. But if you get on his wrong

side, he will lay it on you.”

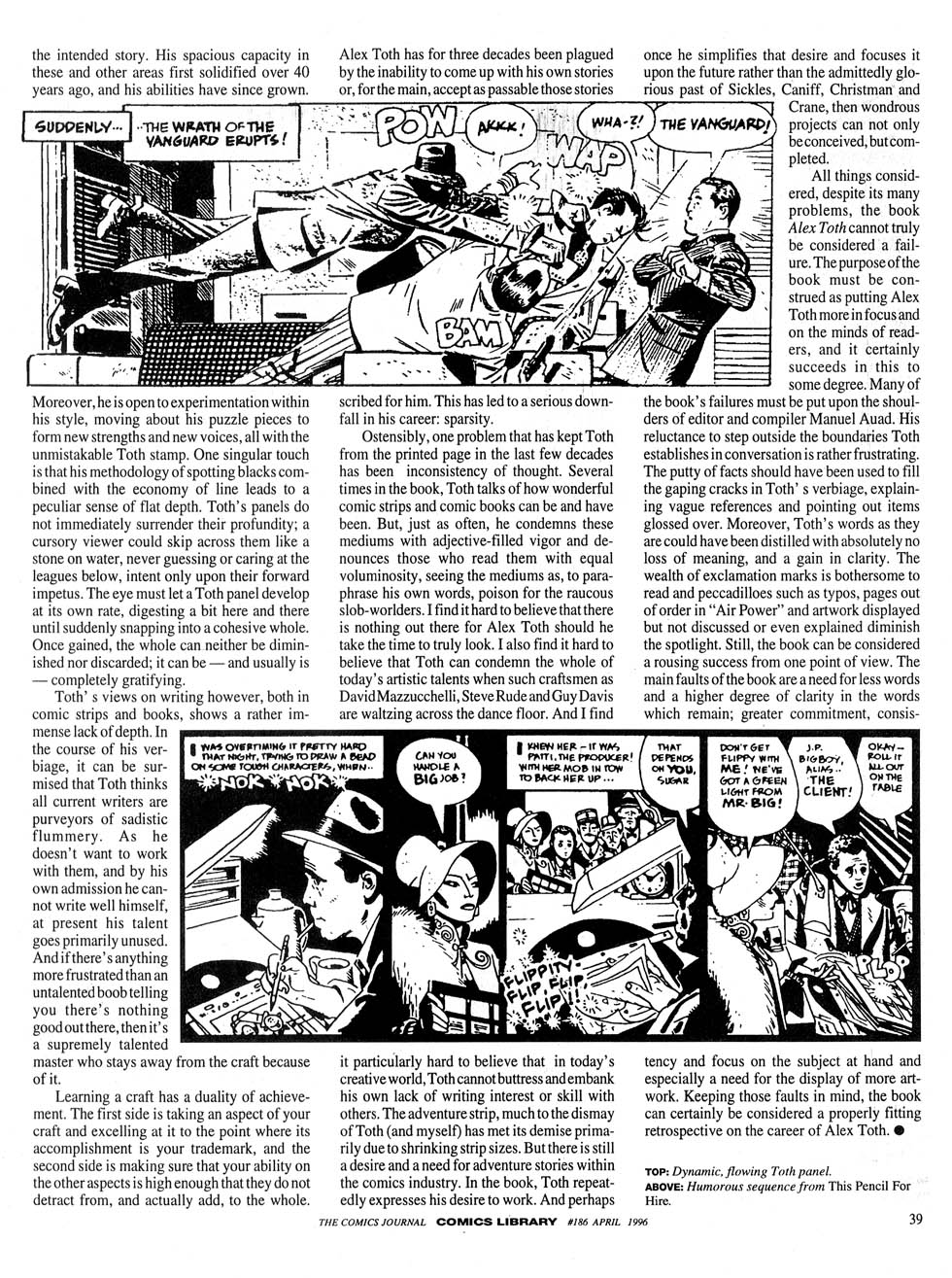

Paul Tobin writes in The Comics Journal #186, page 40:

Tbyrgin lies the tragedy of>the.book, for

Oops, the OCR on this page is totally illegible, so I’ll just include the page:

He’s more critical of the book than I am, and I think the book sucks, so…

This is the one hundred and seventy-fifth post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.