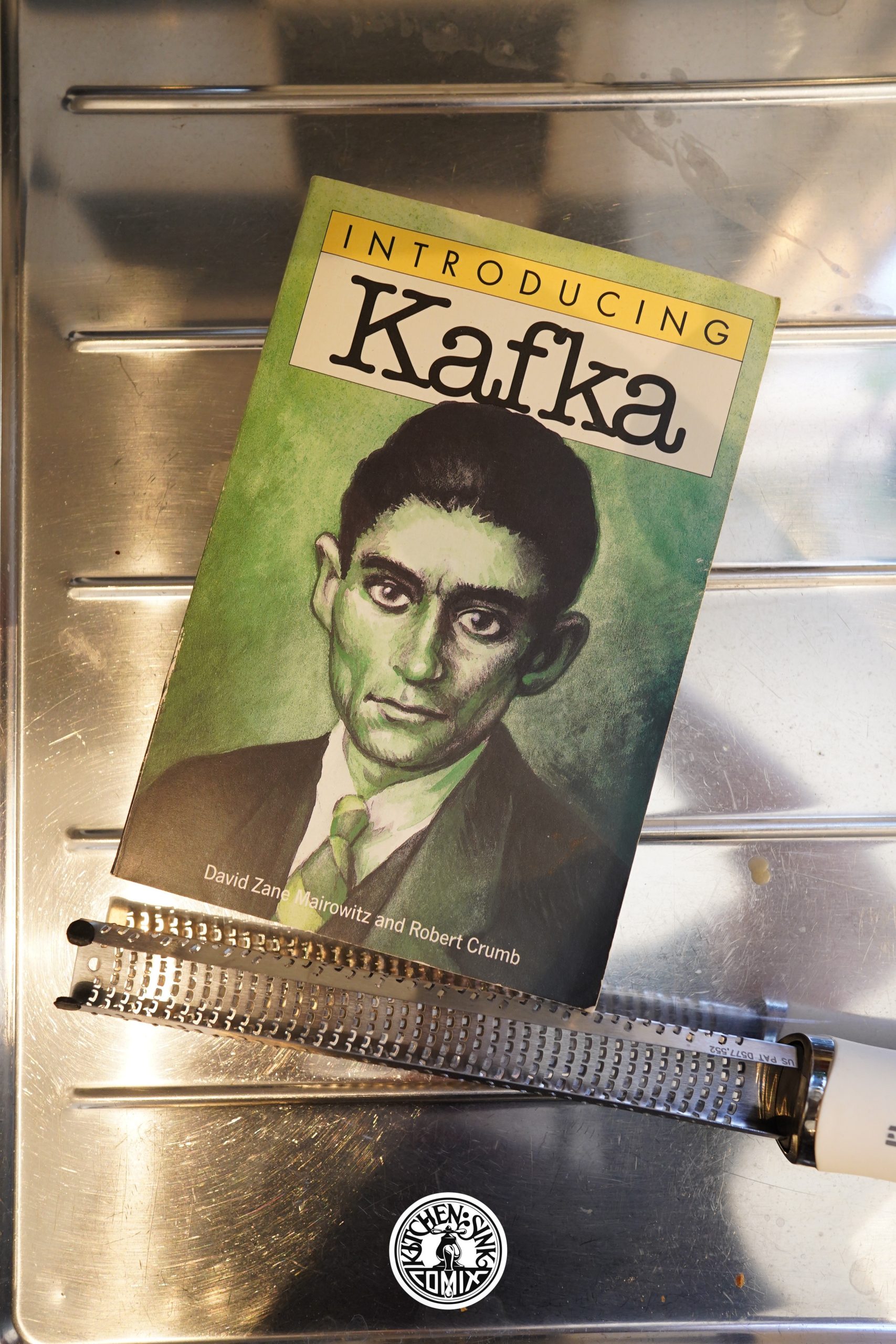

Introducing Kafka (1994) by David Zane Mairowitz and Robert Crumb

This was originally published in the UK under the name “Kafka for Beginners”, which is a much better name, I think.

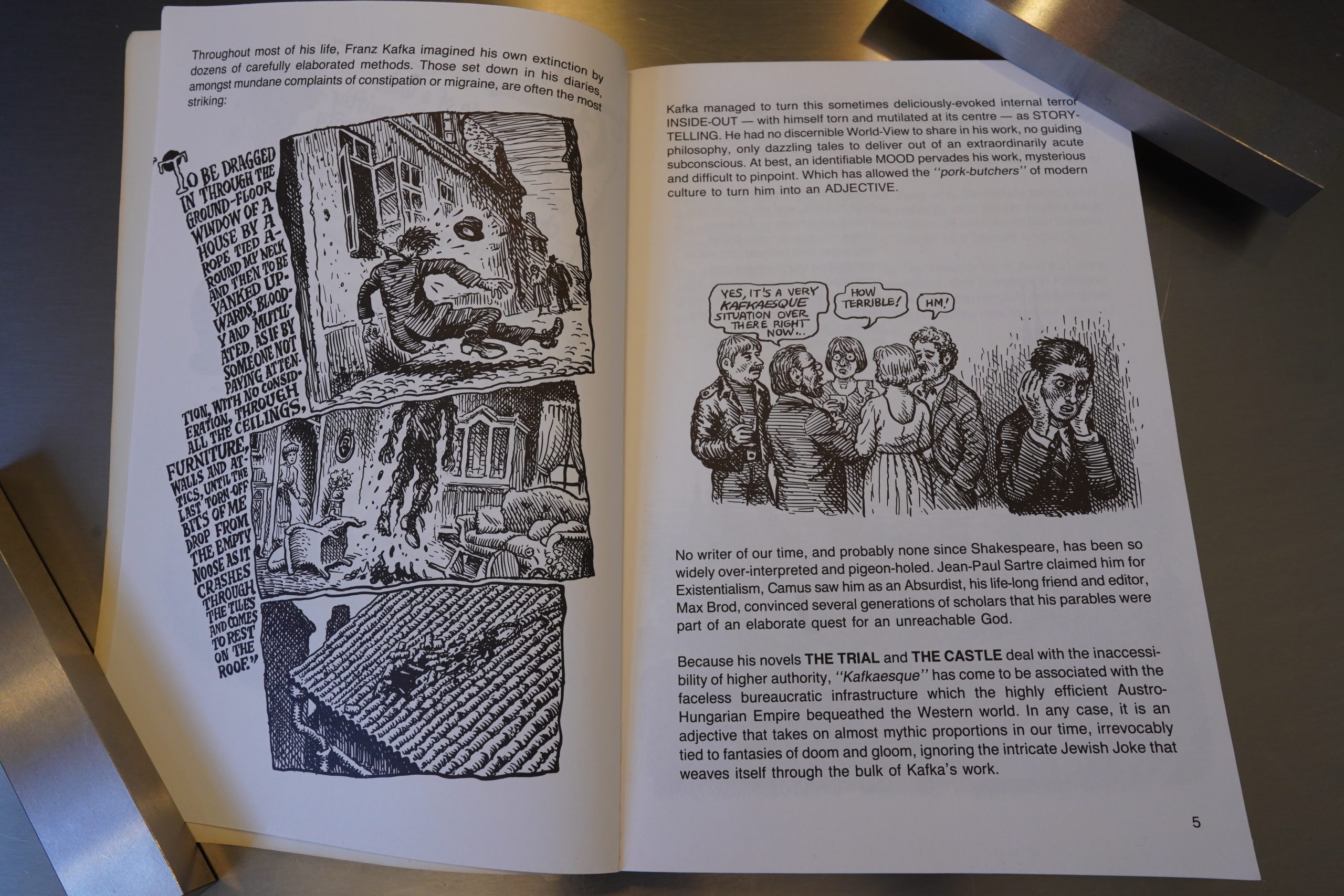

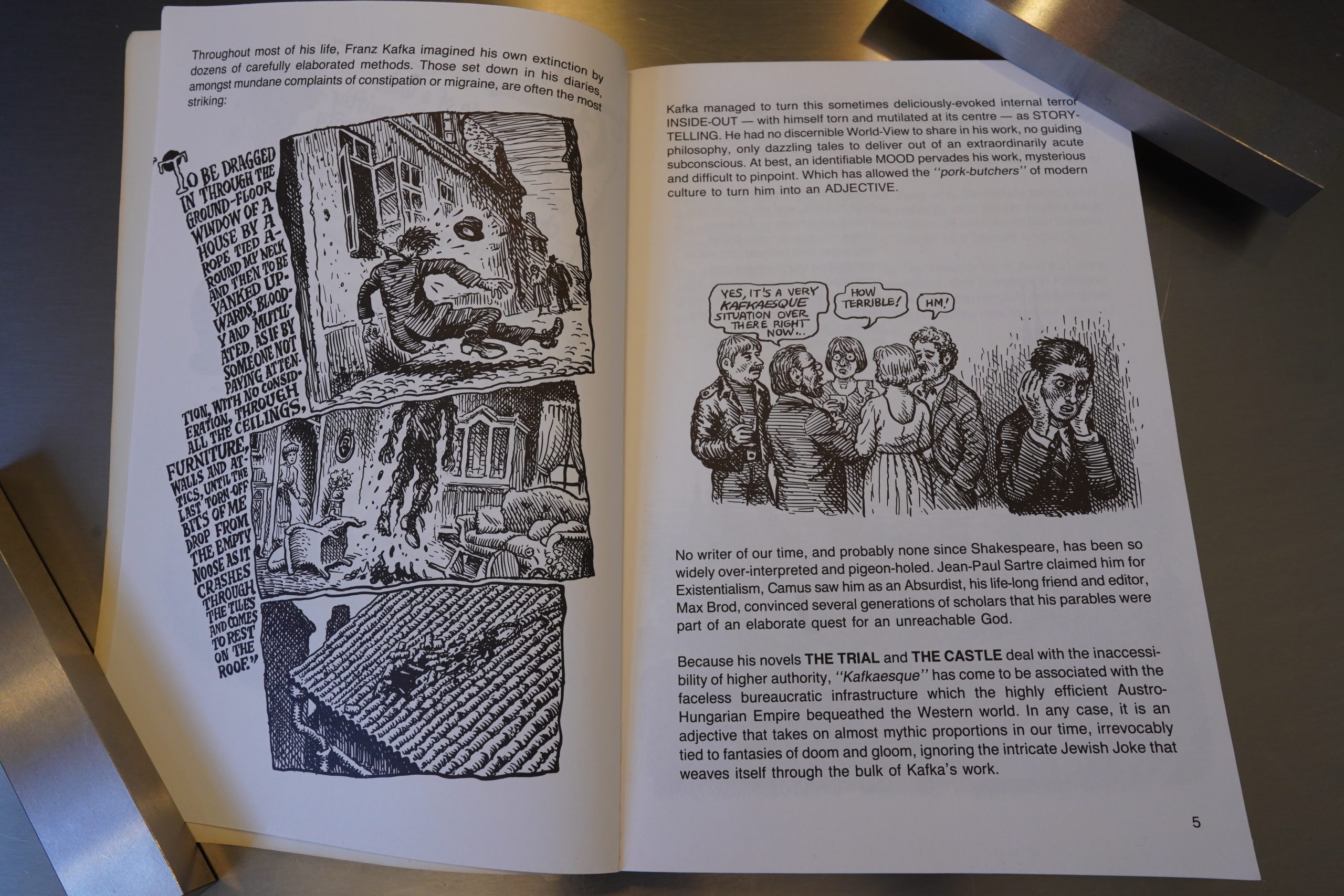

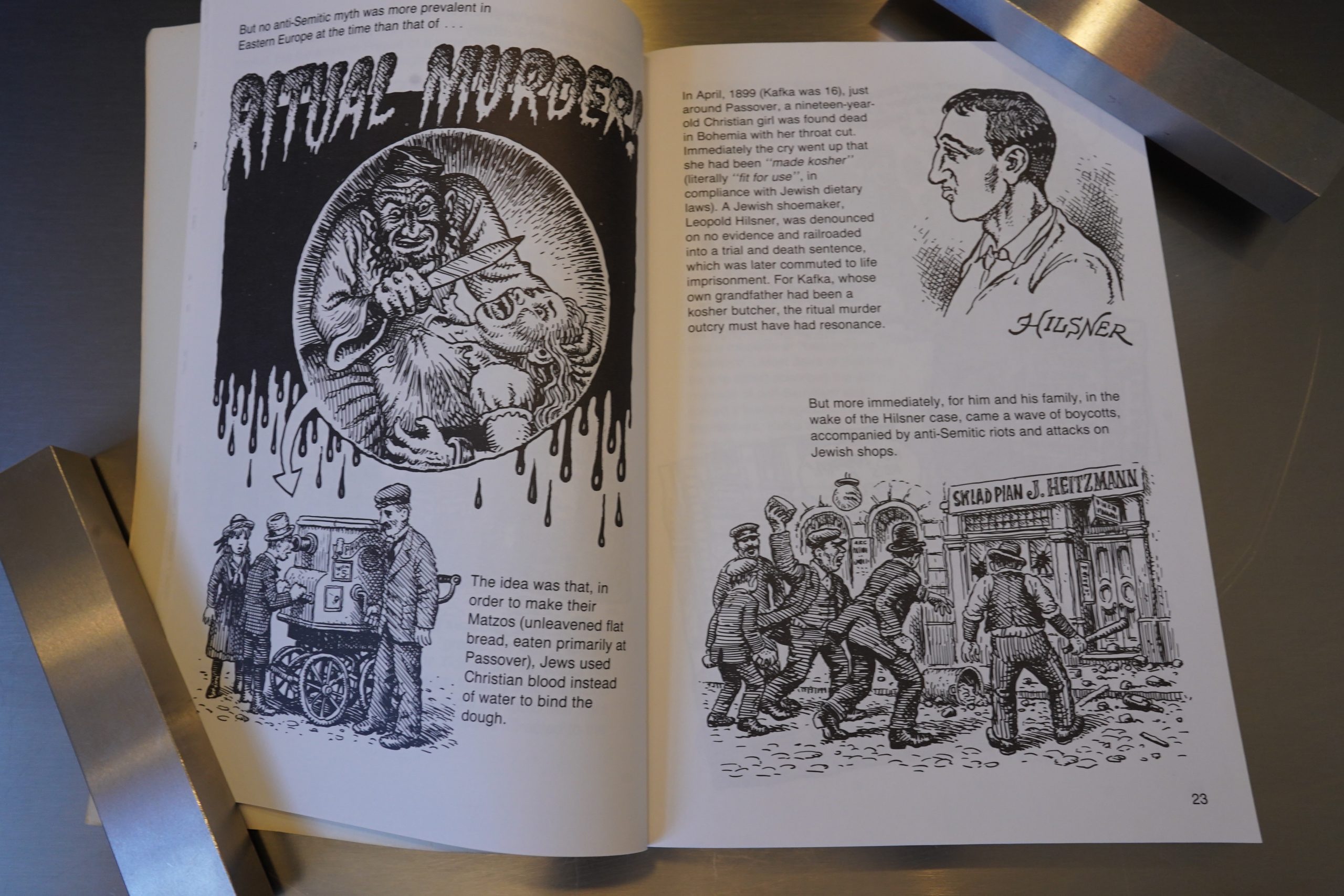

The book is a quite chatty one — it starts off with a polemic against the concept of “kafkaesque”, which is a slightly odd choice. But perhaps it makes sense: What most people know about Kafka is that he is an adjective, and starting with what the reader knows is smart.

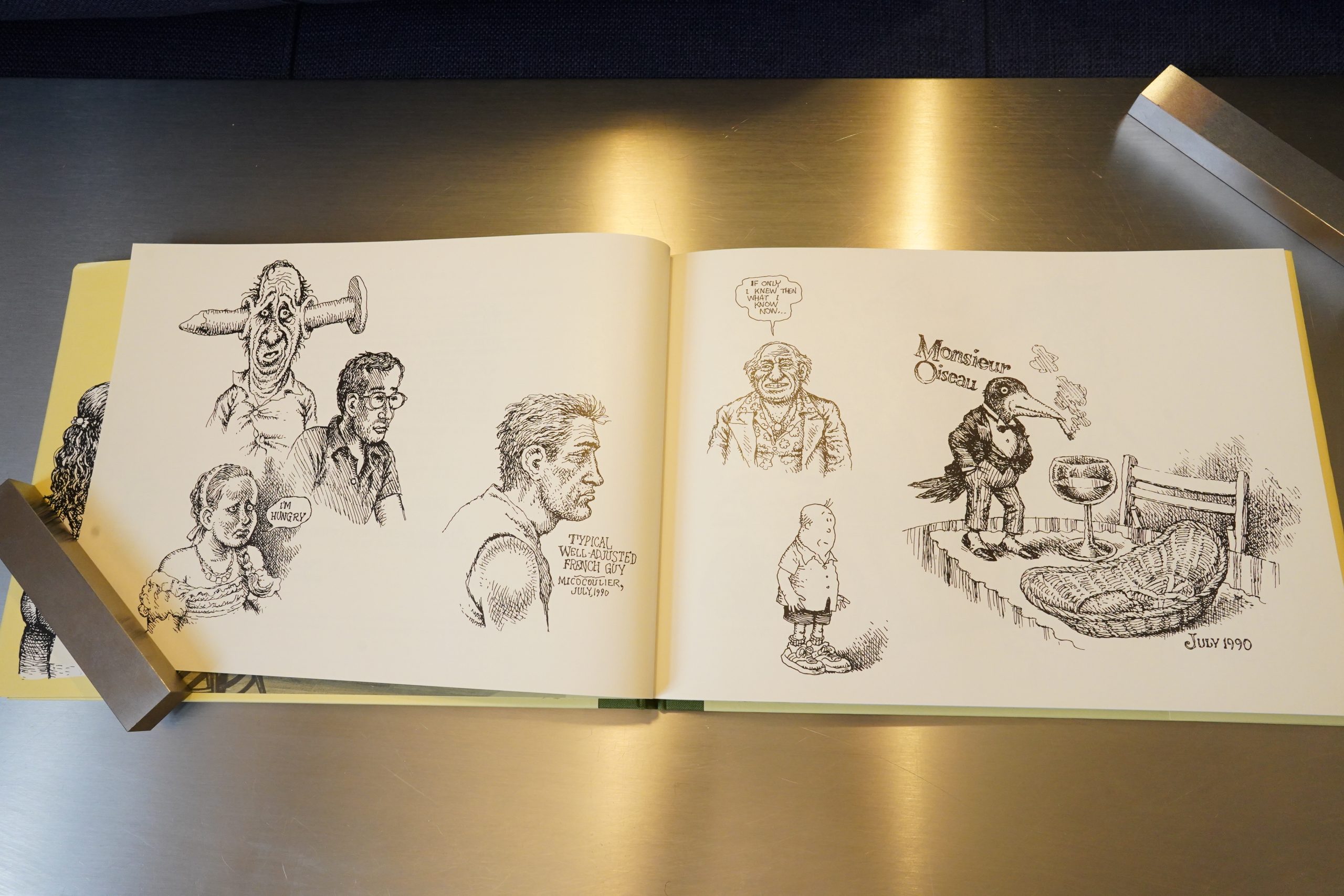

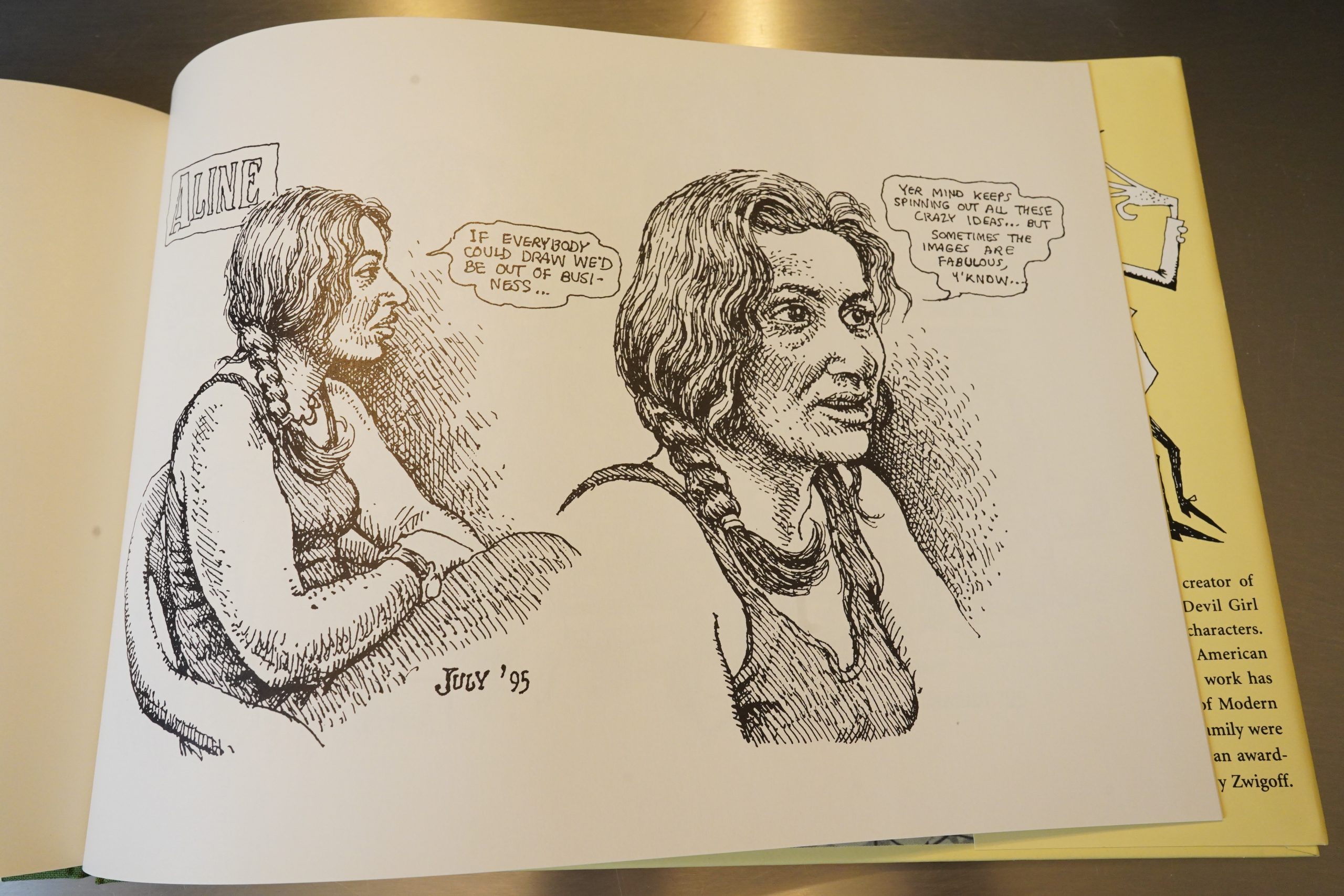

This is one of the biggest illustration jobs Crumb has taken on. Crumb was in a creatively odd place at the time (doing many blues biographies and not so many personal books), so perhaps it just gave him breathing space while trying to figure out where to go next. On the other hand, I can totally see that illustrating this book could be something that Crumb had been wanting to do for years.

Mairowitz’s text rolls along quite nicely, but it’s not exactly… scholarly. There’s many, many instances where Mairowitz writes that Kafka “had to have”, or “must have had”, or some other assertion of some conjecture that Mairowitz obviously doesn’t have any reference to back that up.

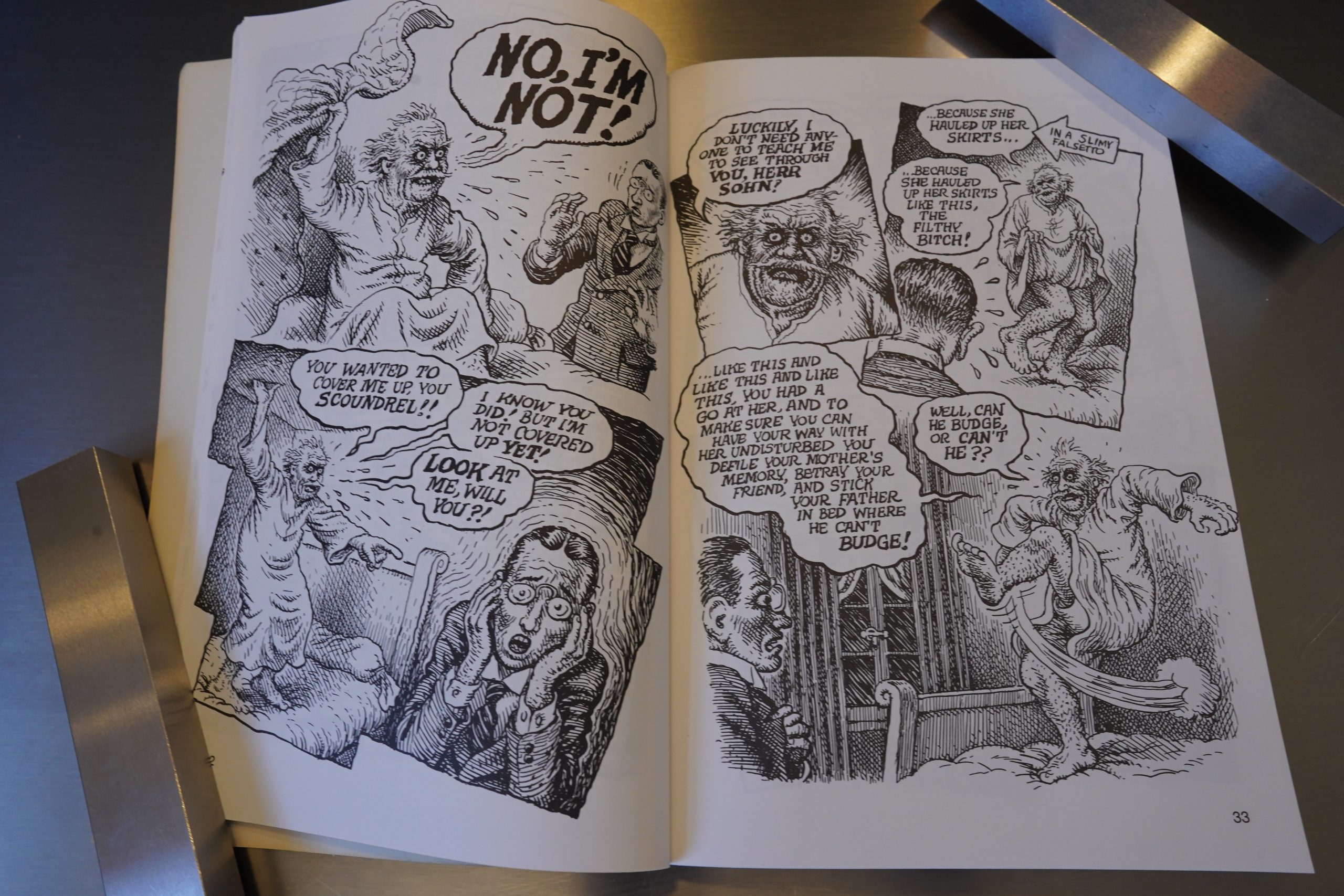

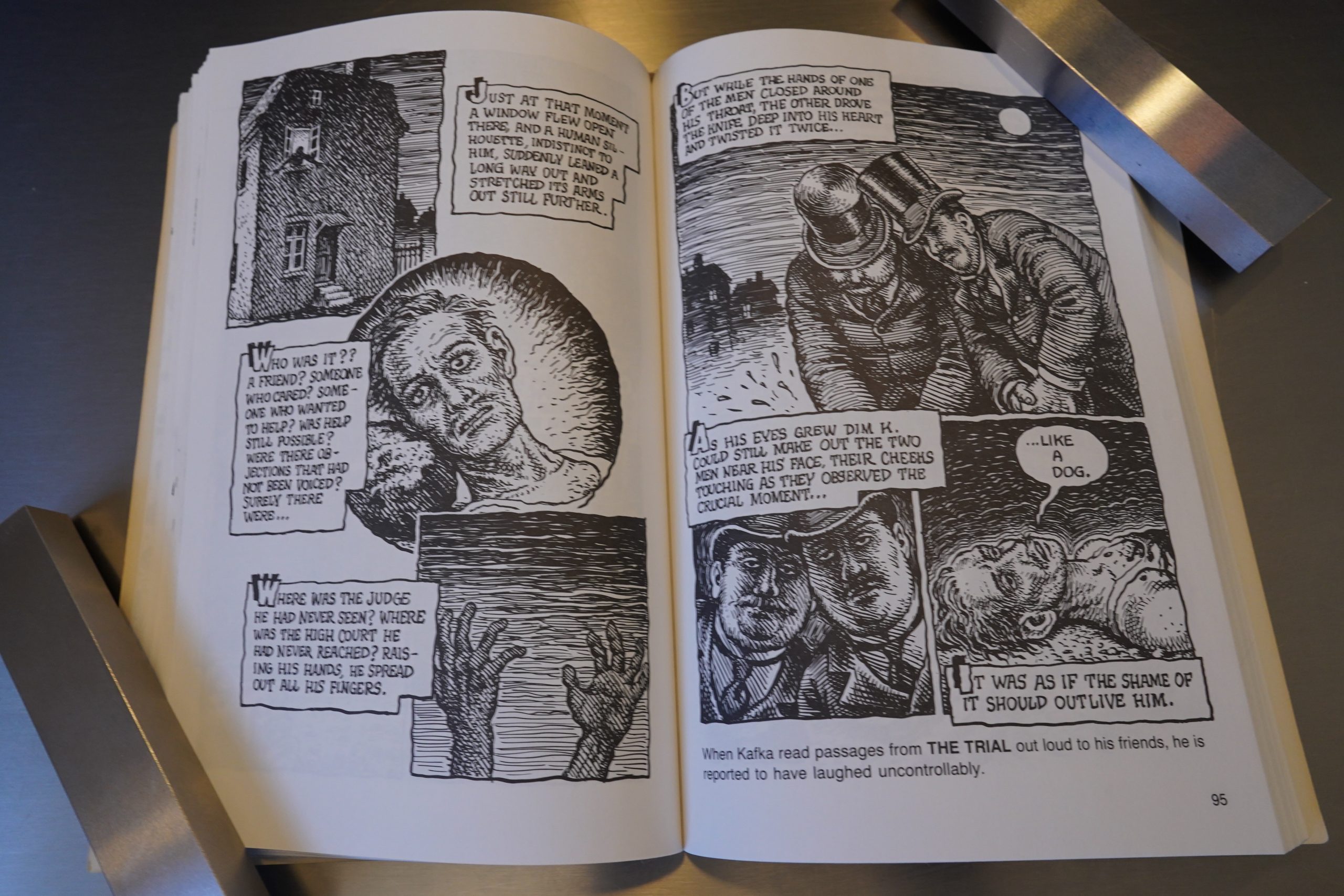

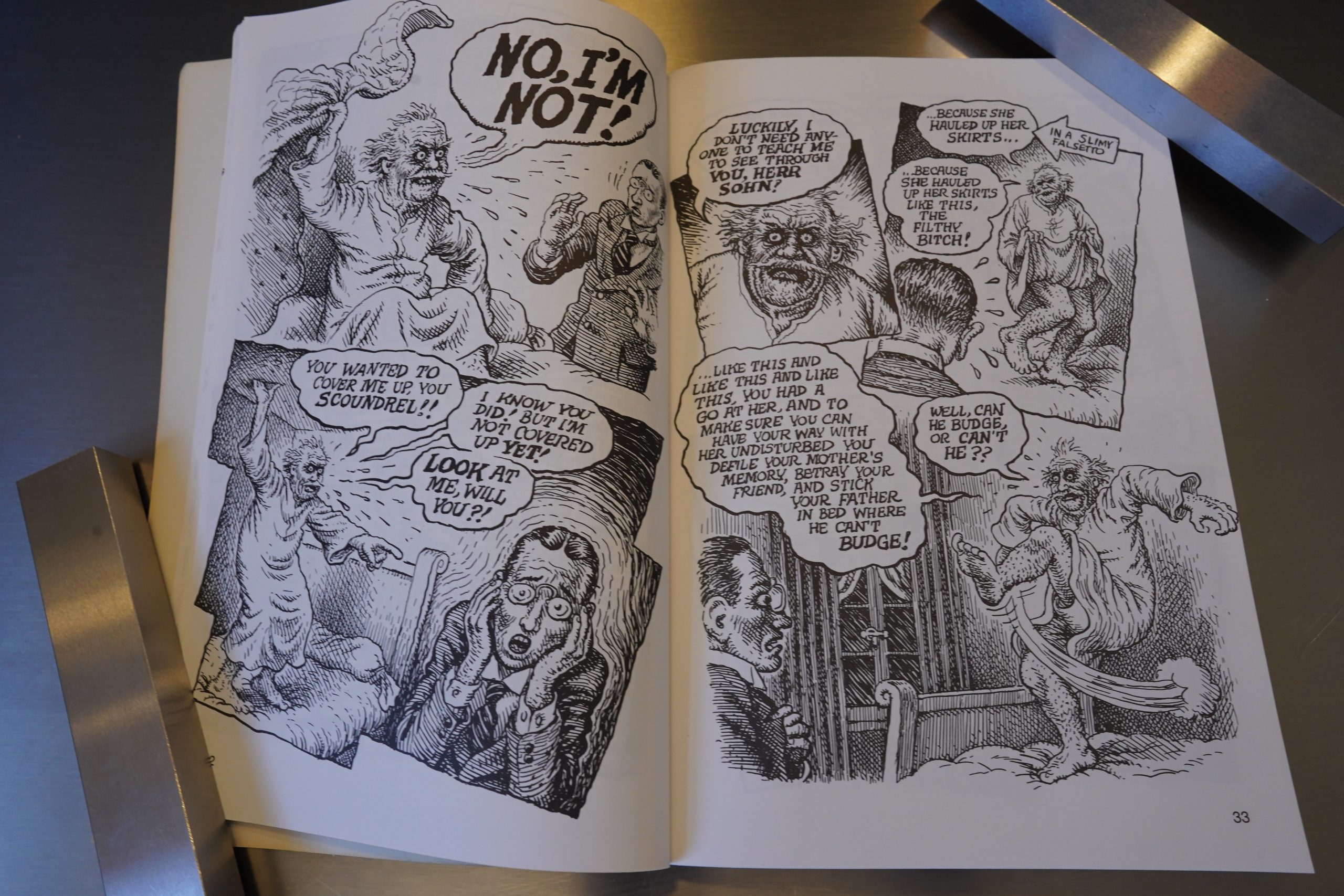

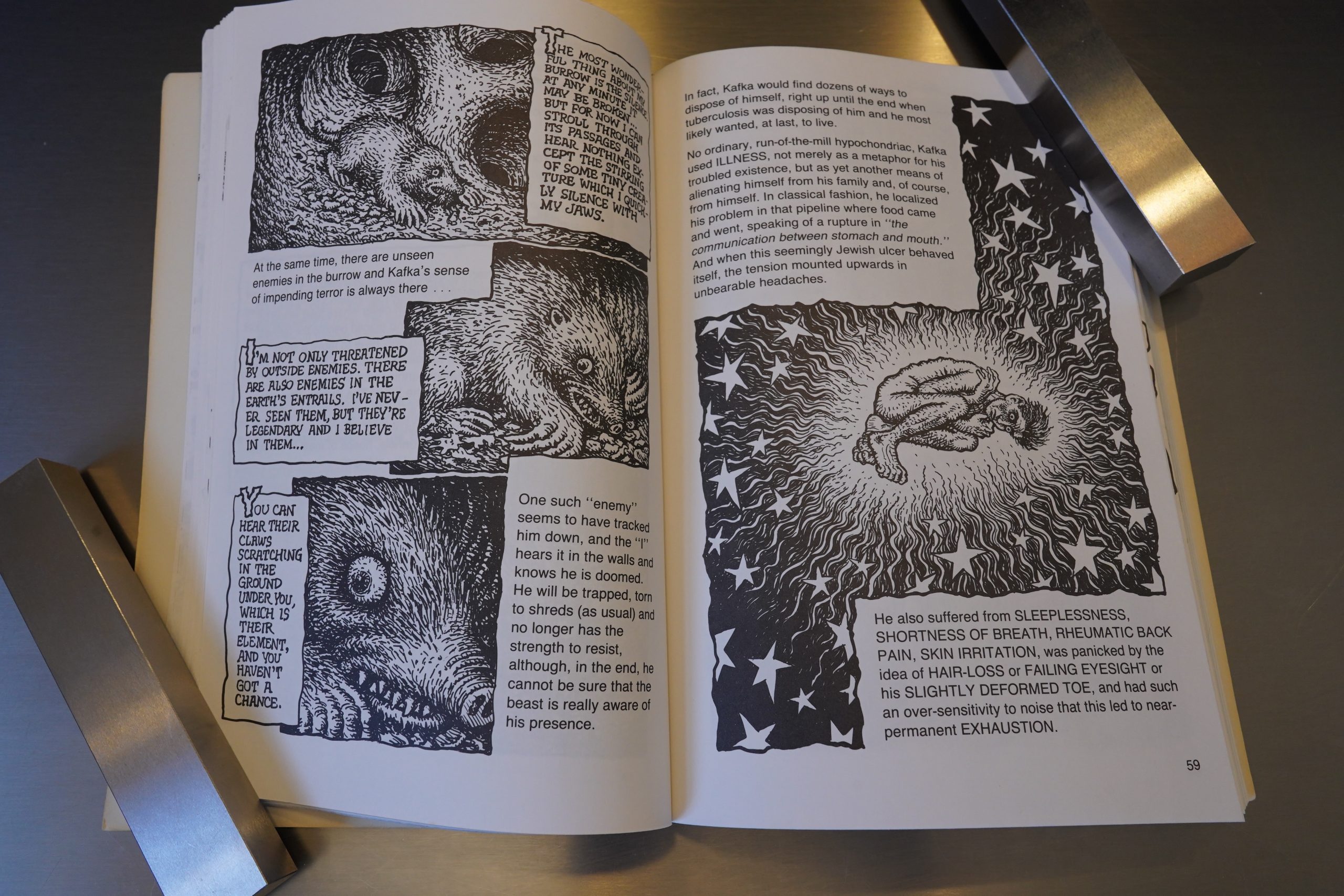

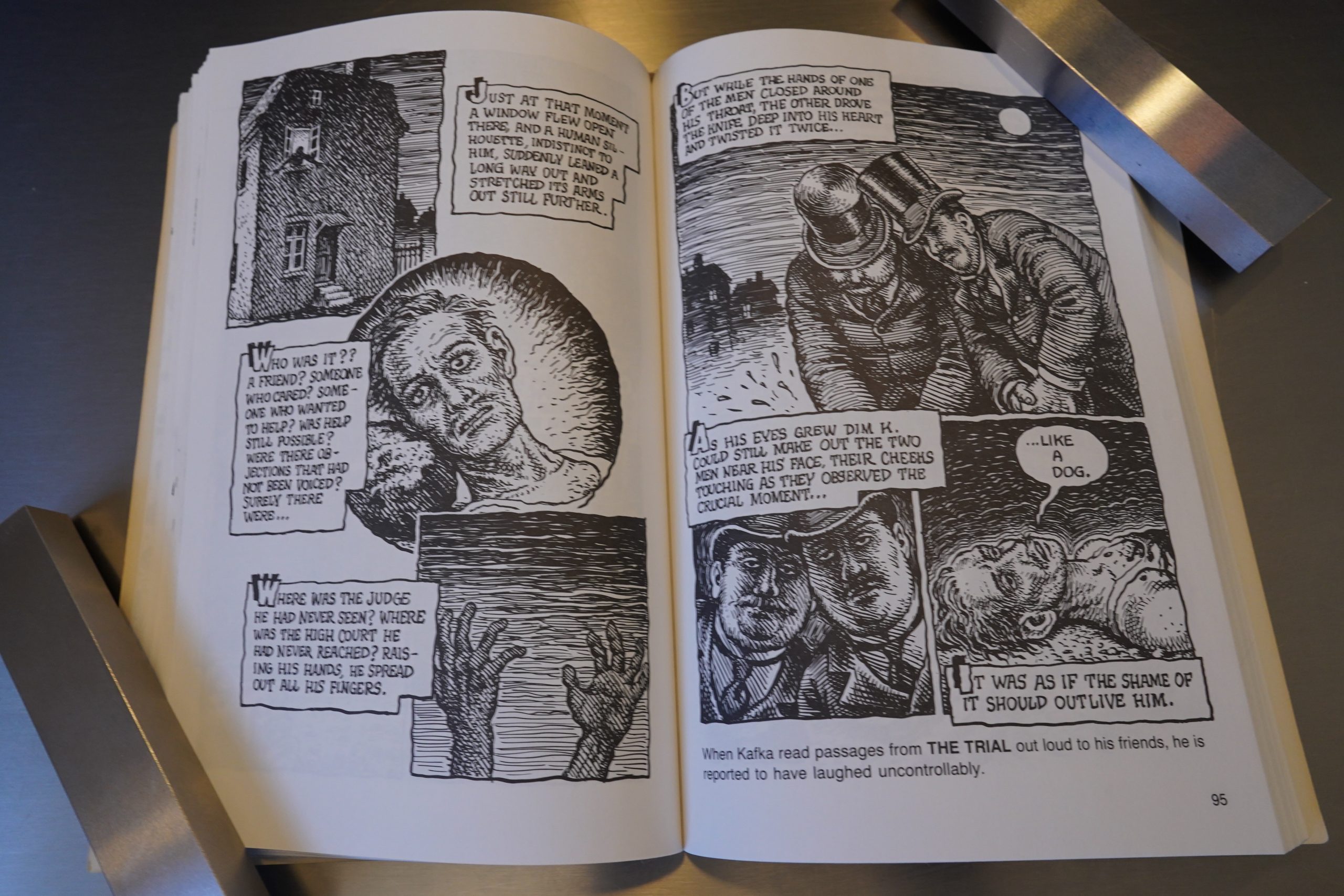

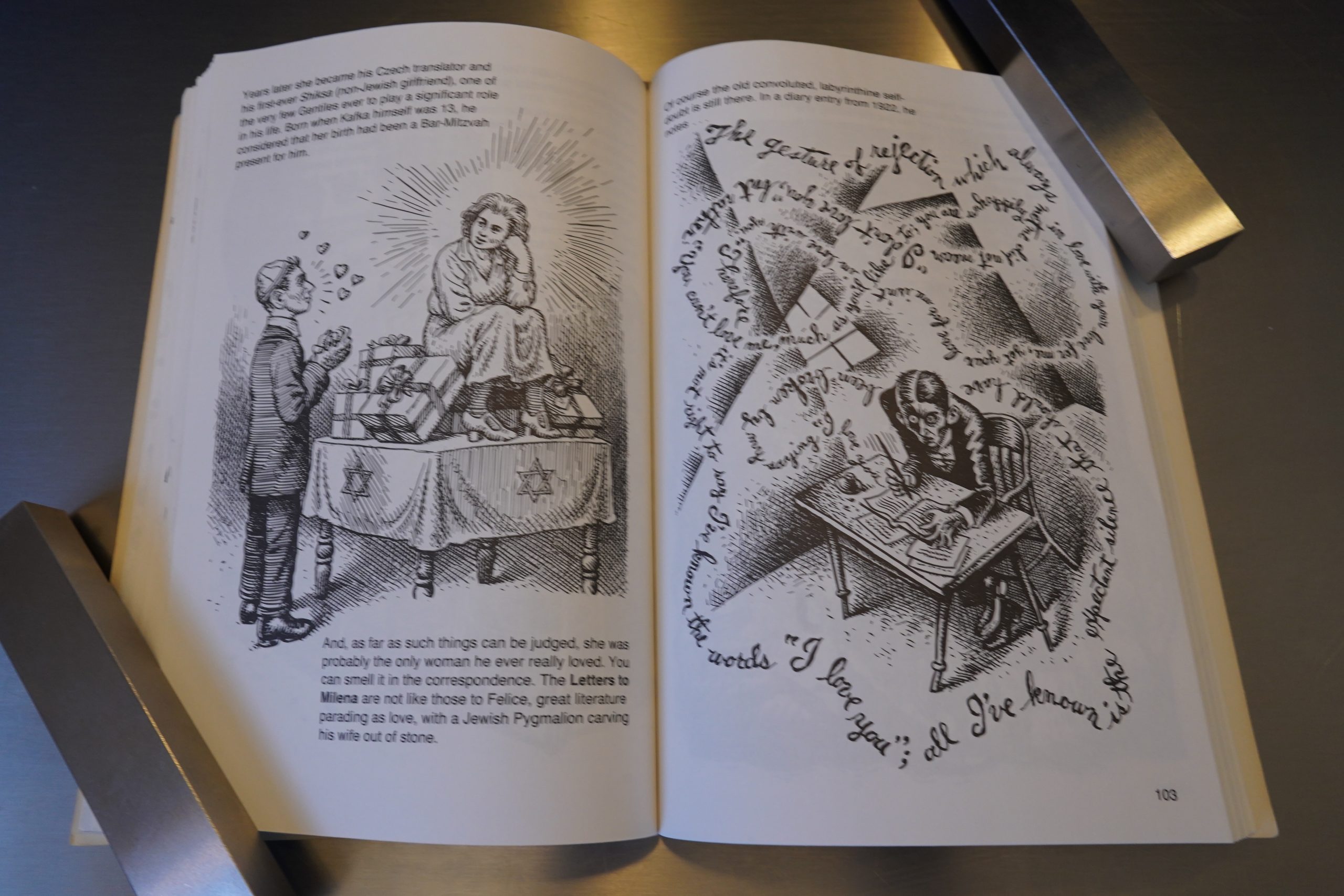

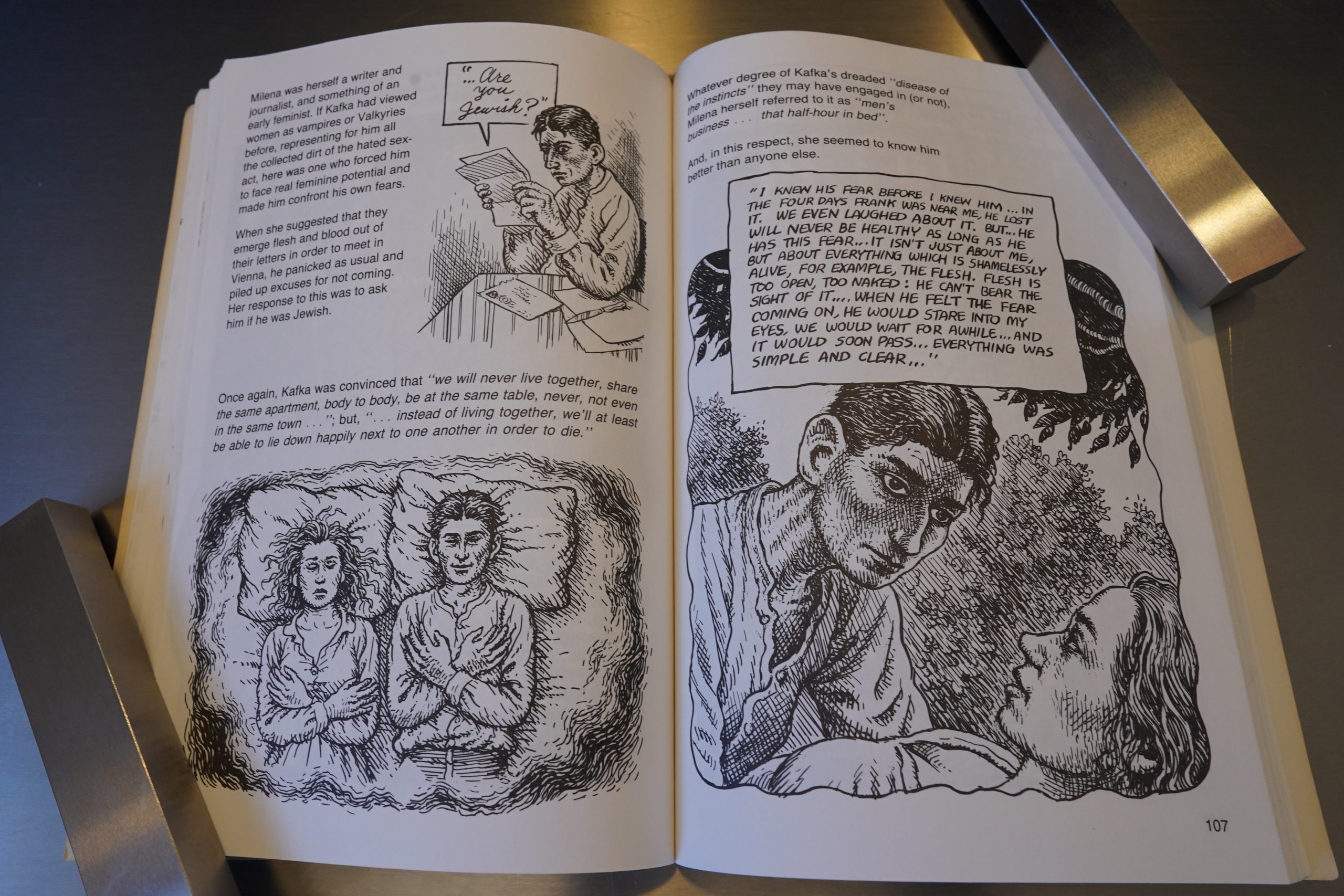

Most of the book consists of text illustrated by Crumb, but there’s a handful of pure-comics sequences, which is nice, because it provides variety. And besides, if you have Crumb, you’d be insane not to have him do some comics.

Using hand lettering for excerpts from Kafka’s works and typeset for Mairowitz’s text is great.

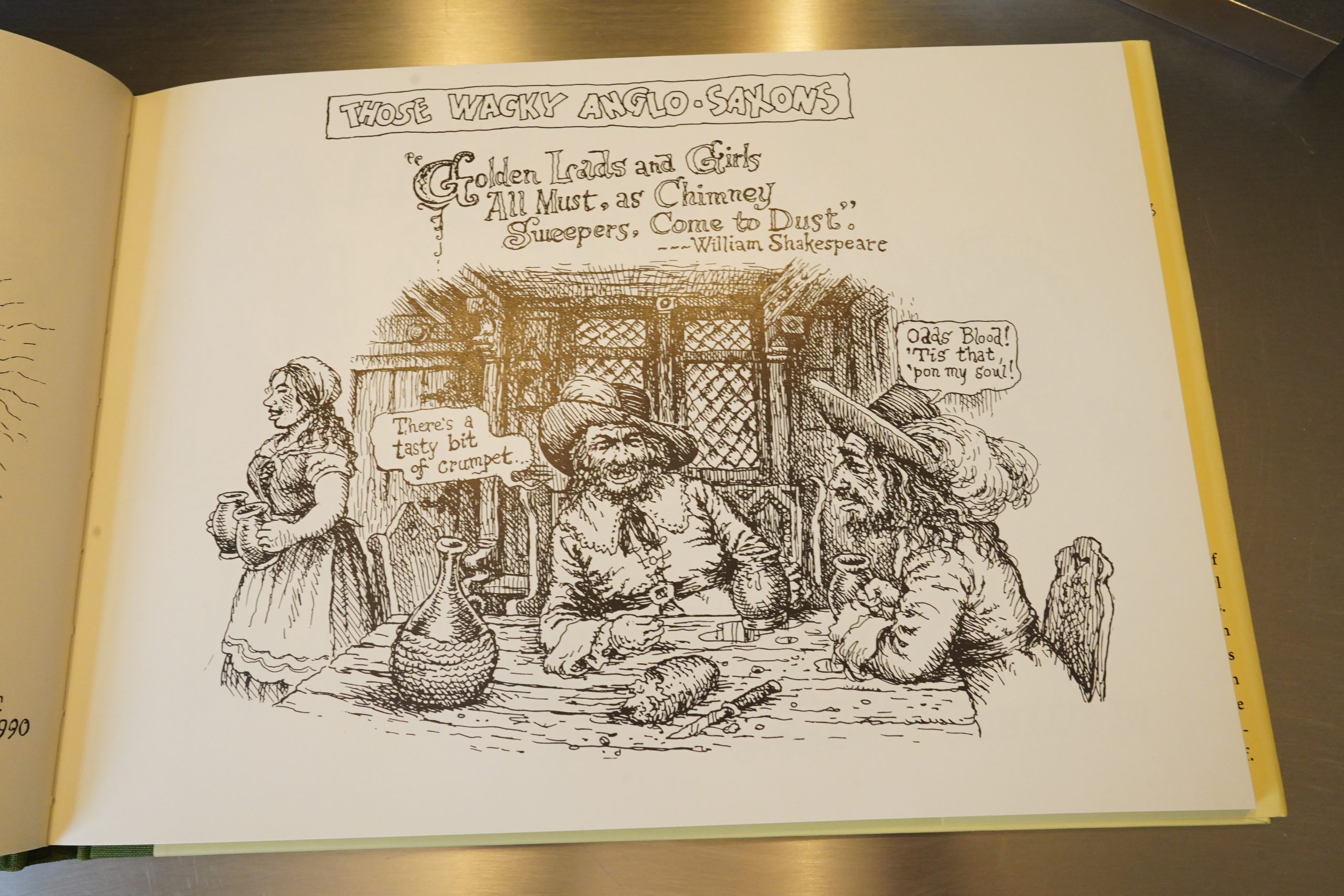

It’s a knee-slapper alright.

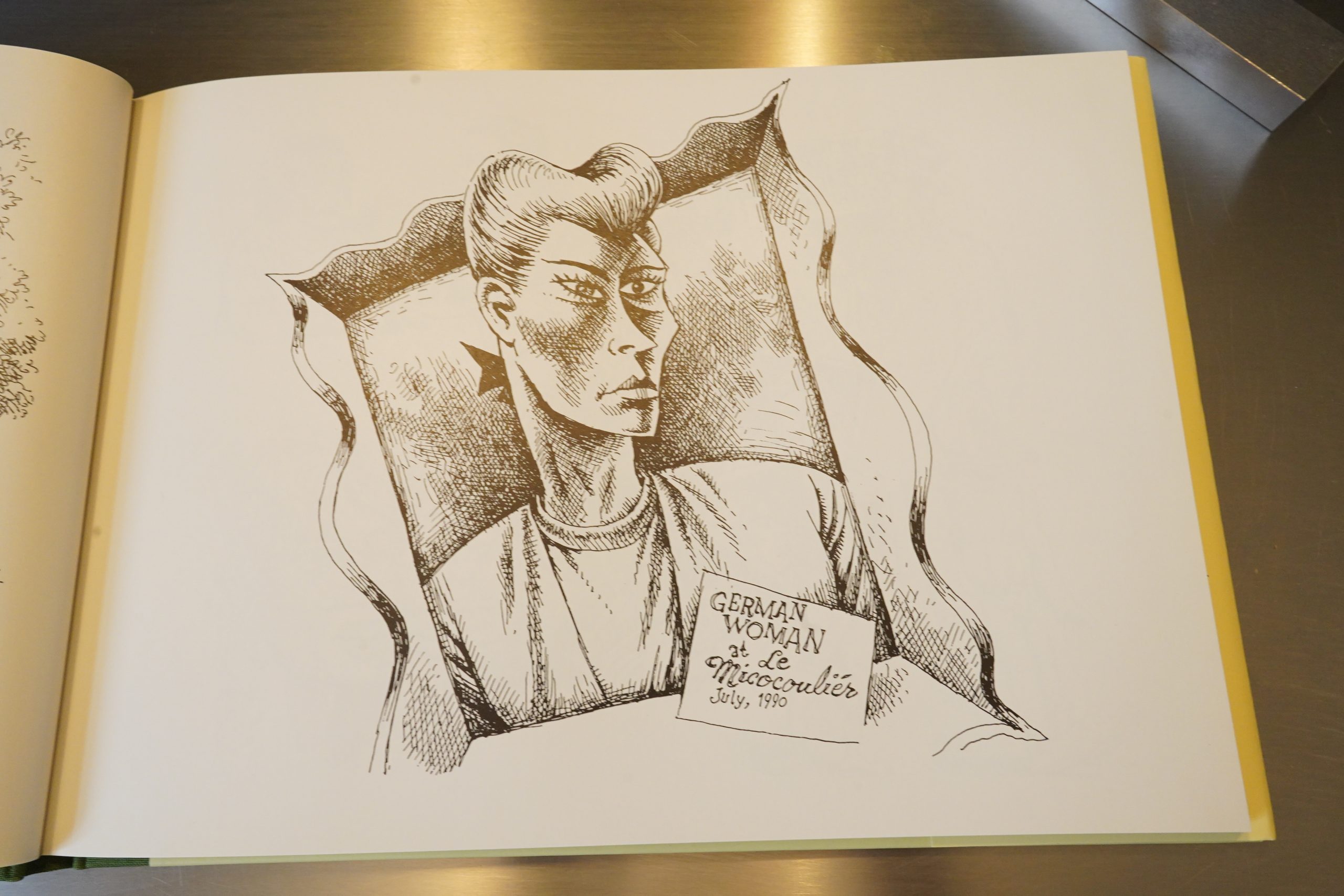

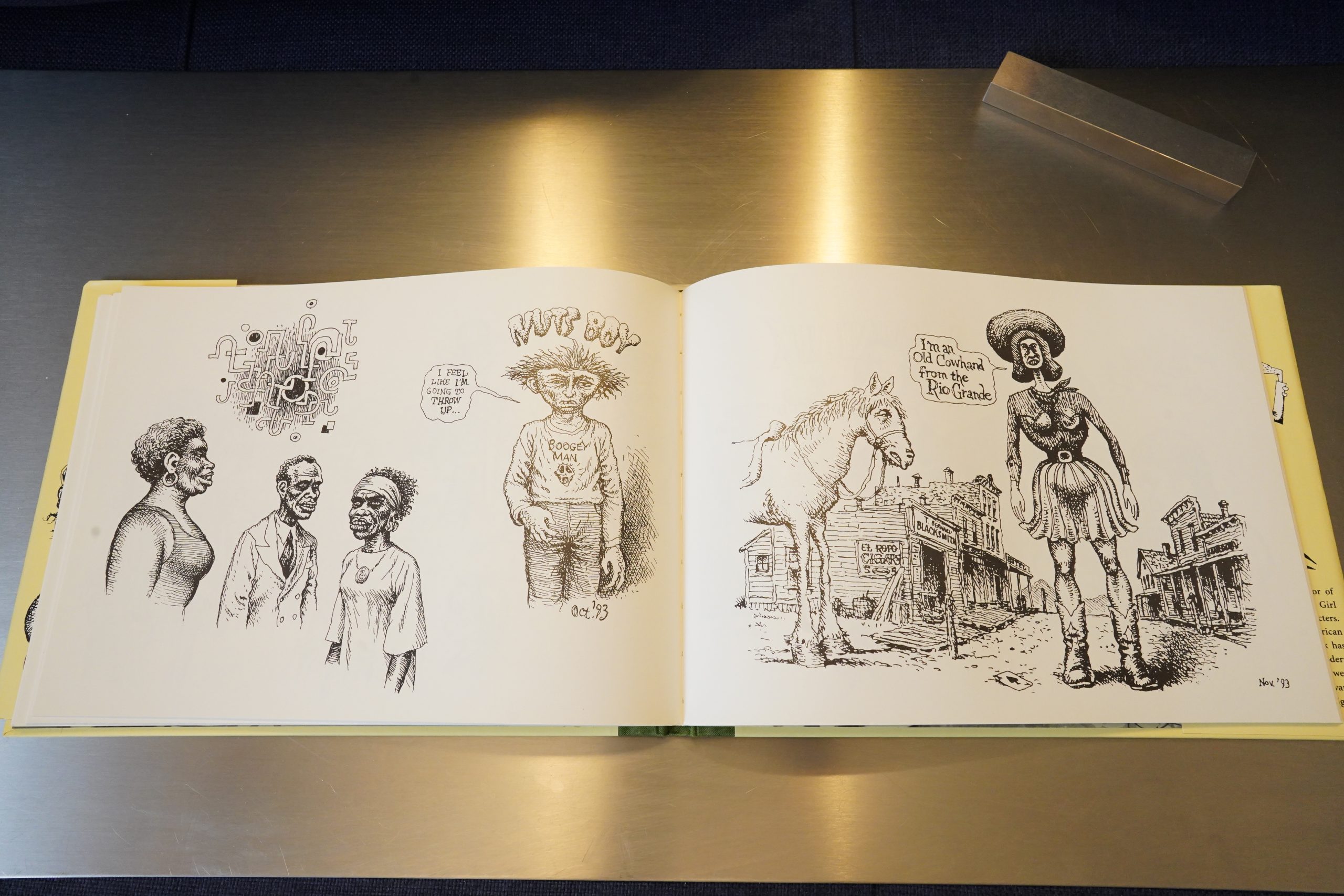

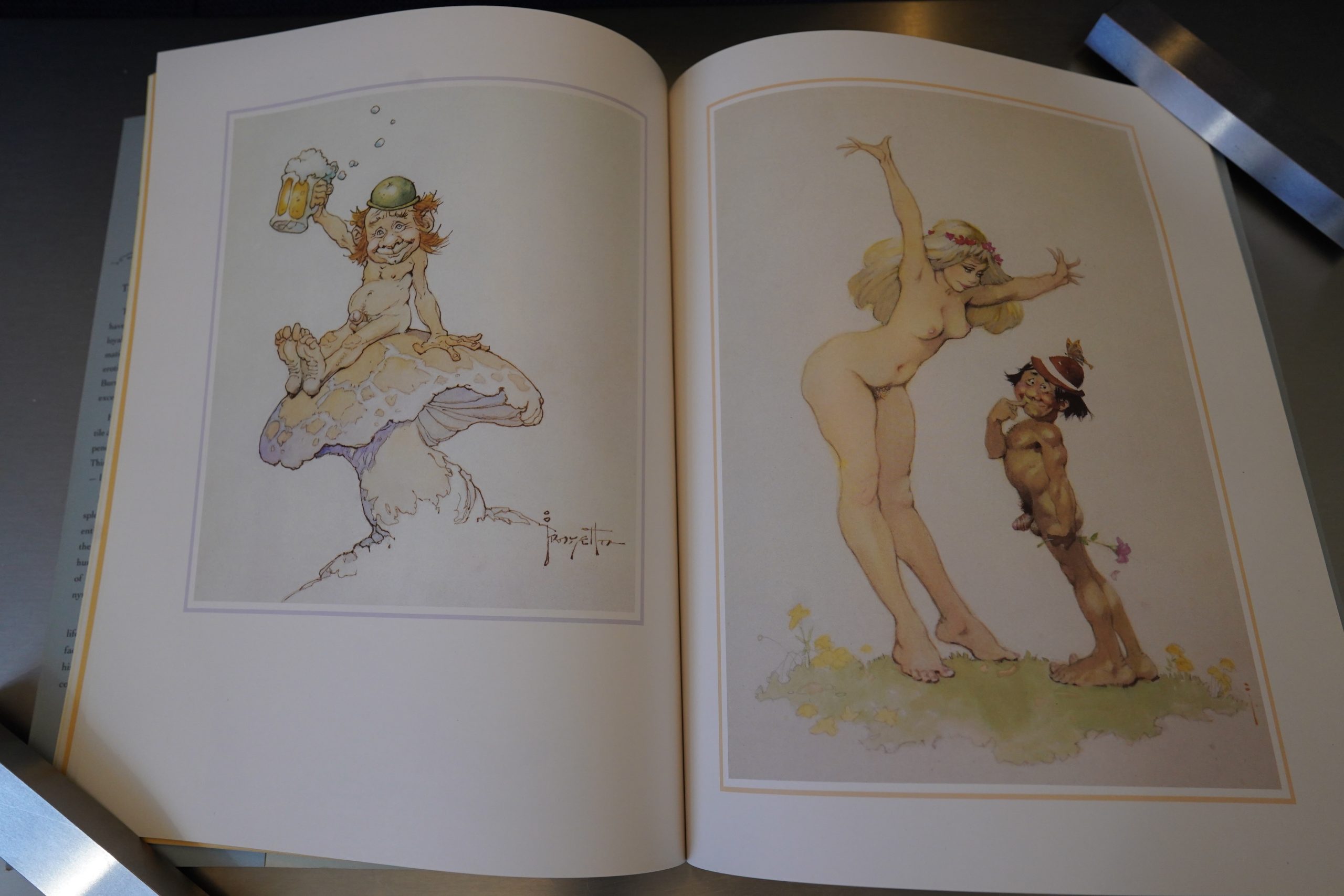

Crumb mostly sticks to his well-known style, but he mixes it up here and there to great effect.

The structure of the book is… er… what structure? We sort of start in the middle, and then zip back and forth and then seem to come to an end, and then the book continues for a couple more dozen pages. It’s very odd, but I think it kinda works? I mean, I was entertained re-reading this.

Crumb is interviewed by Gary Groth in The Comics Journal #180, page 50:

GROTH: Speaking ofsomebody

else’s tragedy, you spent a

year of your life illustrating

Kafka ‘s biography.

CRUMB; Yeah.

GROTH: Which is an unusually

long amount ofrimefor you to

spend on a single project.

CRUMB: I got kind of unknow-

ingly roped into this year’s

work because when I first

agreed todo it I said I could do

an abbreviated bunch of draw-

ings like those other books in

that series. But of course it

turns out I got immersed in all

this detail, so it dragged on

and on and on. But it was an

interesting project. I got to

know Kafka very well. I

hardly ever read him before I

got involved in that. I barely

knew anything about him. But

I got •deeply immersed in

Katka from working On that. I

mean, I ‘m probably one Of the

foremost Kafka experts in the

world now!

GROTH: [laughs] I would assume you would have some sort

of real affinity with him.

CRUMB: It turned out that I did. yeah. The more I worked on

it, the deeper that affinity became until it almost got

spooky after a while; I felt so close to him after a while, it

was almost like I knew him. Have you read much of Kafka?

GROTH: Yeah, I’ve read his short stories.

CRUMB: When you start talking about Kafka, almost every-

body says, “Oh yeah, I had to read him in college.”

GROTH: I read him five or six years ago.

CRUMB: Most people in America have not read much of

Kafka. And his best stuff is the long. books, although

they’re harder to read. But they’re his best work.

GROTH: The novels? Like America and The Trial ?

CRUMB: America… And The Castle I think is the best One.

The Castle is really a masterpiece. But it’ s so claustropho-

bic! But it’s well worth it. Since I was illustrating it, I had

to go back and read certain scenes very closely to make

sure I was accurately portraying this stuff he was describ-

ing. Reading it closely, you get to another level with it, an

incredibly detailed, layered writing that is deceptively

under the surface. You can read it at a certain pace and it’s

written in such a polite. dissident style, that you miss a lot.

You’ rejust reading along, cruising along with it. Butifyou

go back and read it slowly, you start discovering the whole

other layer of stuff that’s going on. It’s really strange that

way, very strange, dream-like. Levels like in dreams.

When I found out that he actually wrote a lot of the time

at night when he was groggy — he was a night writer. He

had a job during the day. and he worked [wrote] at night.

He was probably almost asleep while he was writing. So

he was writing in a very dream-like way. He was such a

compulsive writer that he could… You know how if you

do something enough, you can almost do it in your sleep?

It’s like that with writing. It’s like some musicians are so

good they can almost play music while they’re half asleep.

It’s the same thing.

GROTH: I remember when I read The Meta morphosis

that, like so many people who hadn ‘t yet read it,

I had this vague understanding of what it

was about—a guy turns into a beetle. But

when I read it, all of my expectations went

right out the window and it became SOme•

thing completely other and greater than

I could ever have imagined,

CRUMB: A lot of people assume he’s

going to be like Edgar Allan Poe or

something, a writer of horror stories.

But it’s not quite a horror story. It’s

something much more personal. Psy-

chological, dream-like revelations. Very

Jewish in a way.

Ng Suat Tong writes in The Comics Journal #171, page 57:

WHAT DO CAROLINE LEAF, Peter

Milligan, Brett Ewins, Kenneth Smith, and

Robert Crumb have in common? Well, okay, so

it’s a little obvious. Walk into any library and

you’re bound to find a stack of critical reviews

about Kafka, and Introducing Kafka by David

Zane Mairowitz and Robert Crumb hardly

purports to add anything new to the reams of

literature. This 175-page primer contains

biographical text with illustrations and

adaptations of Kafka’ s short stories and novels.

I’d wager that most Journal readers have

probably bought this book by now, simply on

the basis ofcuriosity. As one ofthe last surviving

“old masters,” Crumb simply demands attention.

But there are potential problems here. Probably

for the first time, Crumb is working with

someone unfamiliar with the art of comics, and

while neuroticism and Jewishness are familiar

hunting grounds, one hardly associates this

kind of material with him.

I suspect that Mairowitz left Crumb very

much to his own devices when it came to the

adaptations in this book. Crumb may even have

been left to illustrate the biographical material

with little or no guidance on Mairowitz’s part,

but I seriously doubt this, since there are certain

sections in the work which do suggest a degree

of cohesiveness — such as this scene where a

group of academics spout words of wisdom

concerning Kafka, including gems like: “The

dream images seem to merge Kafka’s brothel

experiences with his parents’ sexuality and his

mother’s cooking” and “Dietary habits no less

austere than those of orthodox Judaism helped

to cut him off from society.”

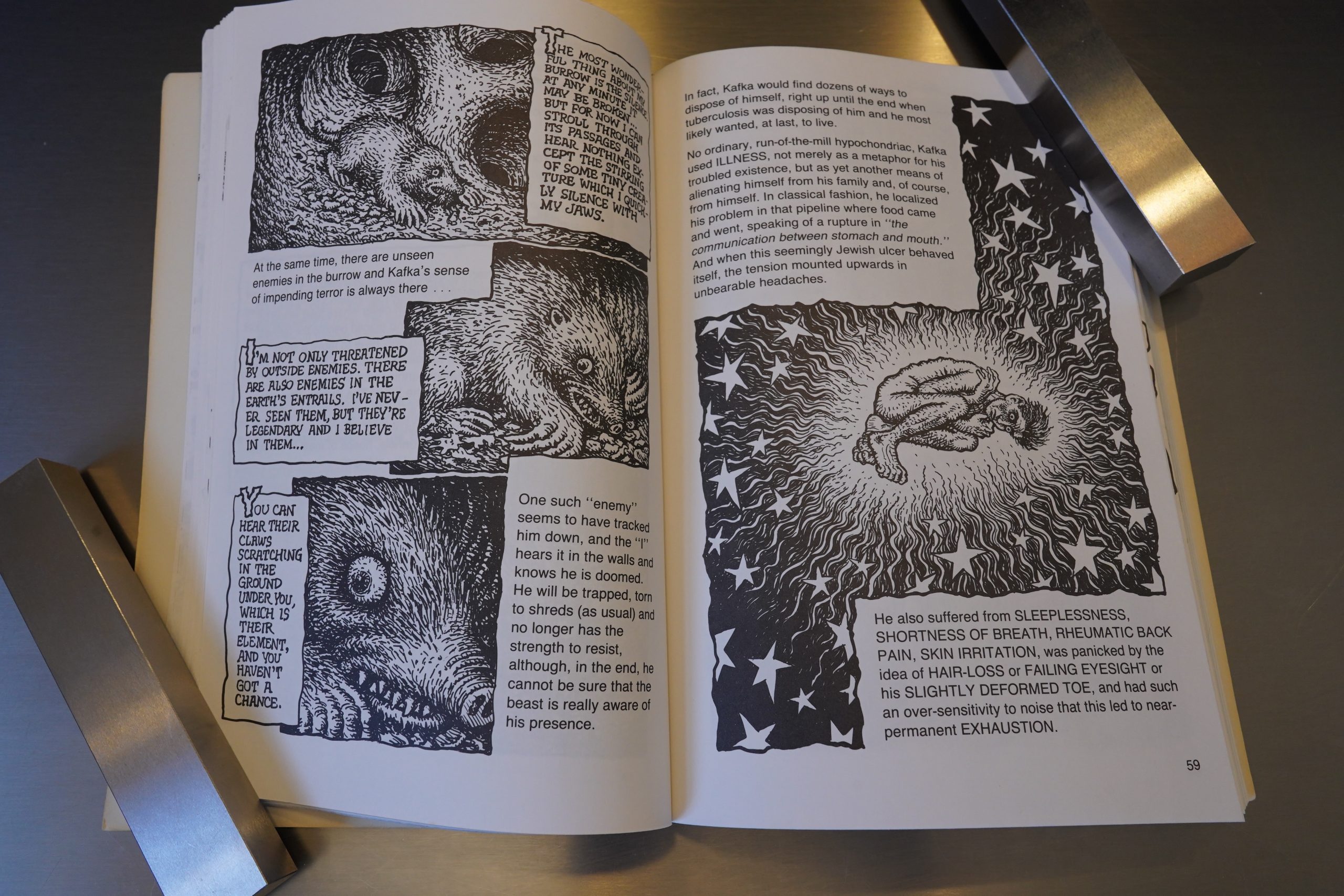

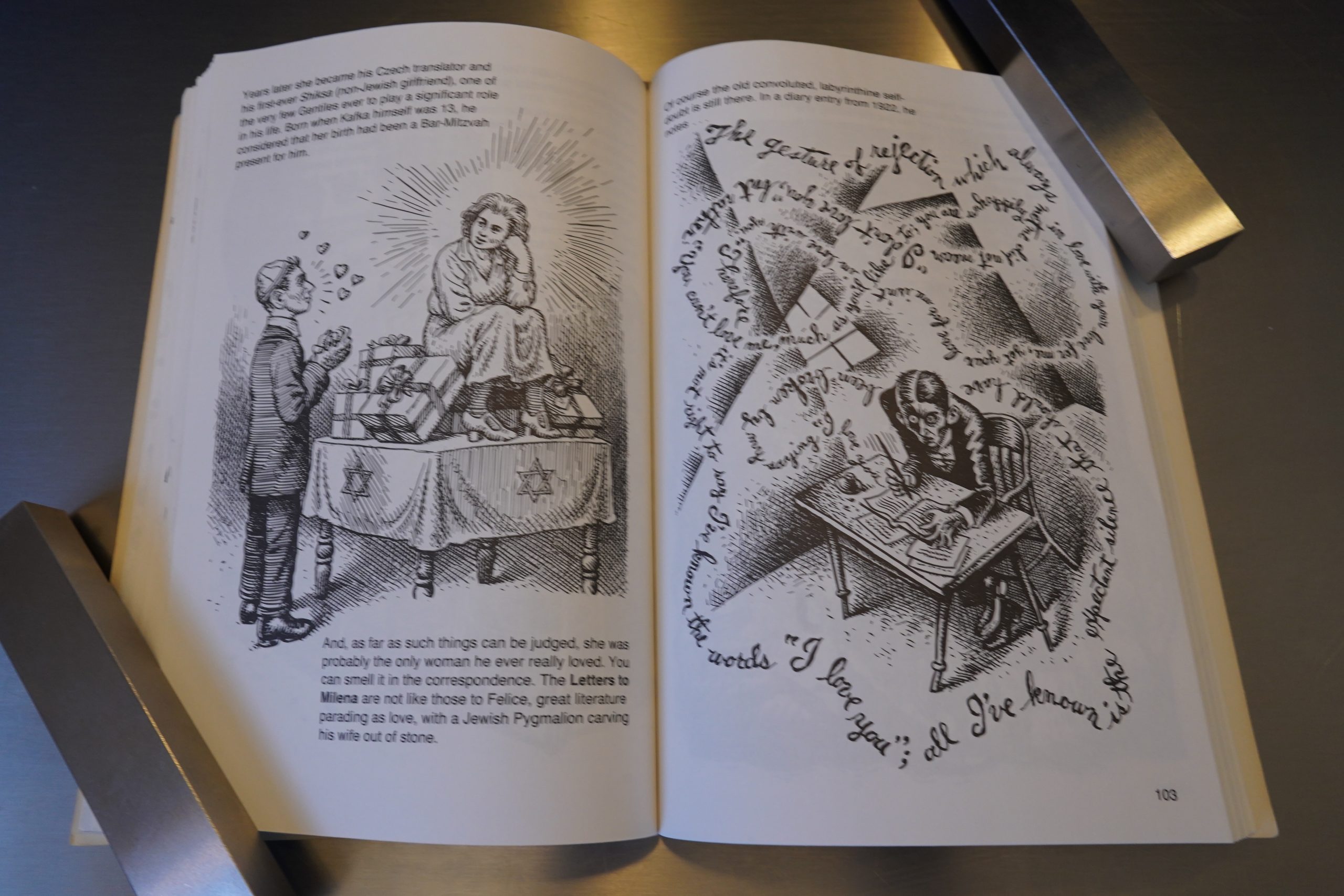

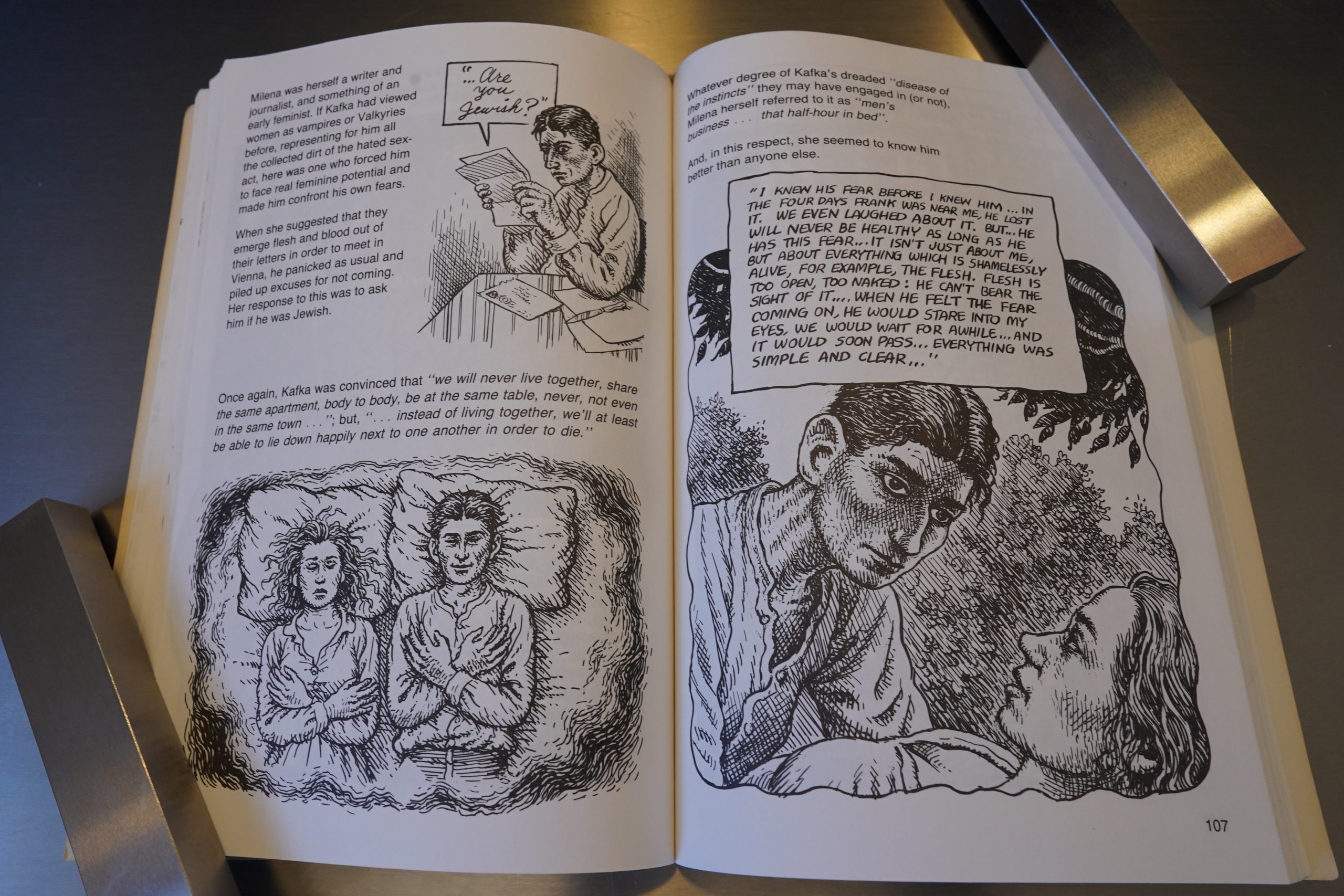

There is another section in the book in

which Mairowitz attempts to link the string of

contradictions in Kafka’s life. Here his per-

ceived unhealthiness is contrasted with his abil-

ity to take long walks and to swim during the

winter. In addition, Kafka’s apparent asceti-

cism and unease with sex (“a punishment

for the happiness of being

together”) are thrown into

conflict with his easy

dealings with prosti-

tutes and his somewhat

erotic relationships with

his fiancées. Crumb

(rightly or wrongly)

seems to stress a simple

level of causation in both

these contradictions by

showing a rather tense

Kafta holding the hand

of his irrepressible fa-

theras he leads him away

for a swimming lesson in

the first instance, and then

showing a similarly anxious

Kafka being led away to bed

by his chosen whore. Are we

experiences with prosti- a •

tutes and his father lie at

the root of his feelings

of inadequacy and self-

doubt?

[…]

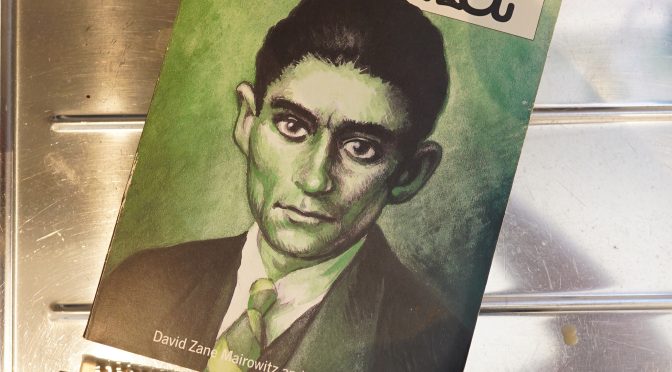

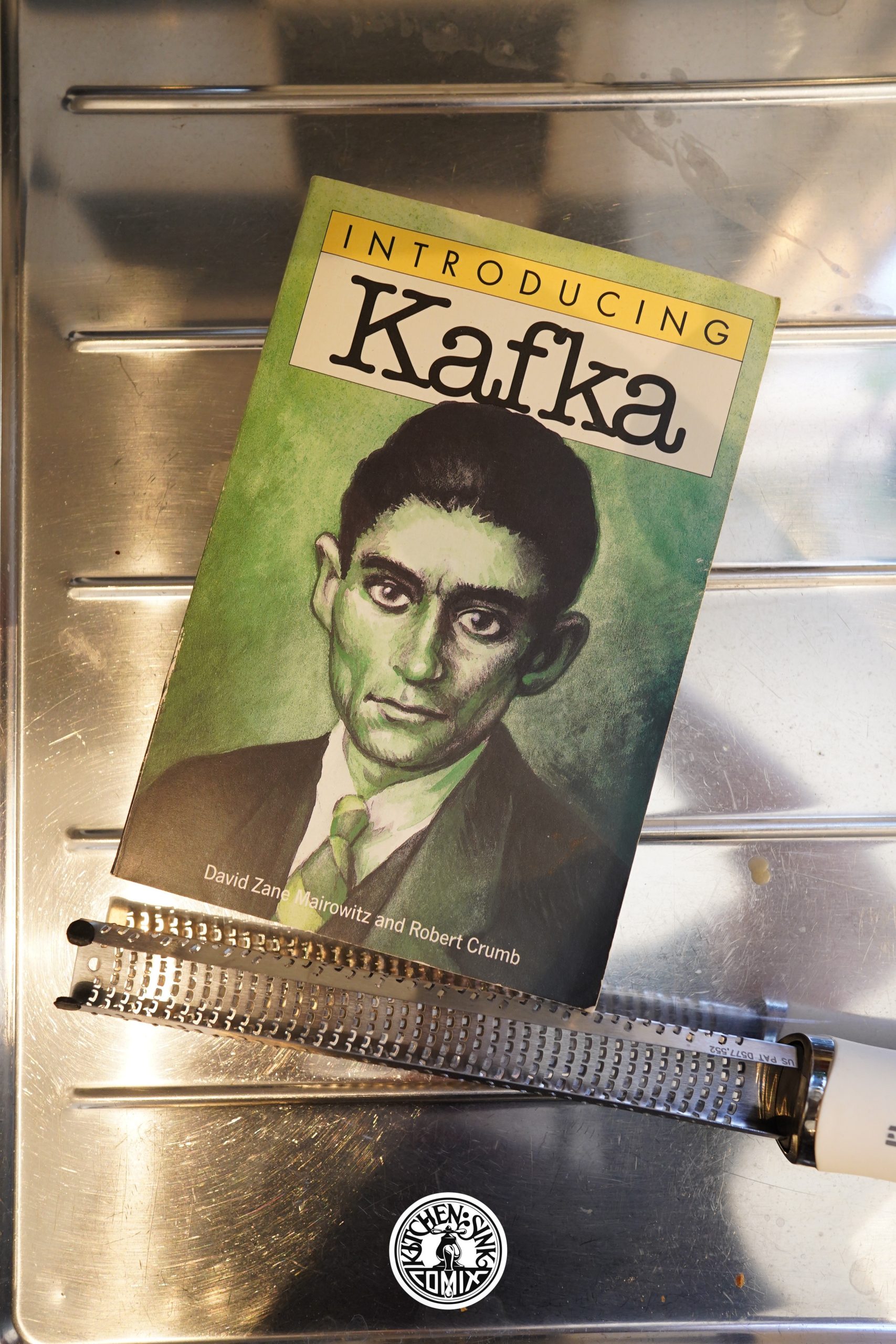

Introducing Kafka is part of a series of

books which have dealt skillfully and amus-

ingly with demi-gods like Darw’in, Einstein,

and Freud, and topics like feminism. The work

in question is certainly as well-drawn as any of

the others I’ve read, and Crumb’s style seems

particularly suited to capturing likenesses (as

may be seen from the British cover to the book,

a portrait of Kafka). But is it as inventive as

Michael McGuiness’ Jung for Beginners, for

example? The comparison may be an unfai r one

since McGuiness had decidedly more leeway in

terms of ideas covered, using etchings and

collage to enhance the text while making know-

ingjibes at Jung’s life and relationships. Some-

how there seems to be little mileage to be gai ned

from making fun of the rather tragic-comic life

of Franz Kafka. Others

would disagree.

On the other hand,

Crumb’s drawings do

give a greater sense of

time and place. He

draws on photos, repro-

ducing and altering

them to suit his pur-

poses and that of

Mairowitz’s text. The

panel layouts and siz-

ing and overall page

design are not to be

dismissed lightly, and

one need only flip

through this book to find

numerous exquisite

borderless drawings.

On a purely superficial

basis, this is probably

one of Crumb’s most

beautiful books, and

that is hardly a word

one normally associates with Crumb’s comic

work (his portfolios being very studious). Hu-

morous, gritty, and confrontational, maybe, but

beautiful?

Ifthis review seems in any way negative, let

me add hastily that I enjoyed reading this little

book. You’ll be hard pressed to find a better

illustrated text On Kafka, and only rarely will

you find Crumb showing as much care with

eachpanel of his work. And let me say one more

thing: this book deserves to be nominated for a

prize. Not for the art, mind you (that hasn’t

changed much over the last few years), but for

the excellent

lettering: ac-

curate and

professional,

demonstrat-

ing an admi-

rable range,

and changing

with each new

letter from

Kafka or his

colleagues.

Dramatically

accentuated at

times,

yet

wholly in har-

mony with the art and, occasionally, adding

considerable beauty to it. If you’re a person

who has read tons of books about Kafka, this

book does afford one or two hours Offun. If you

haven ‘t read any Kafka before (highly unlikely,

I suspect), this book may be slightly expensive,

but does have the potential to encourage further

reading. Which leaves me with but this to say:

buy this book Not only because it’ s by Crumb,

but also because it’s rather good.

The book was reissued by Fantagraphics under the name “Kafka”.

Noah Berlatsky writes in The Comics Journal #286, page 115:

Though they share a superficial interest in

the grotesque and neurotic, R. Crumb and

Kafka are very different artists. Crumb’s

work is confessional, satiric and expansive

— his sexual hang-ups, prejudices and pass-

ingfanciesare splashed about with a visceral,

muddy abandon. Kafka, on the other hand,

is a controlled and understated writer. He

meticulously combines this particular mun-

detail with that incongruous notion

until, in excruciating slow motion, reality

crumbles away in dry, granular flakes.

Having Crumb illustrate Kafka’s biogra-

phy was, therefore, a risky move — and, as it

turns out, a disastrous one. Rather than trp

ing to find a way to adapt his style to Kafka’s

needs, Crumb simply blasts ahead With his

own tropes, turning Kafka’s sly, ambiguous

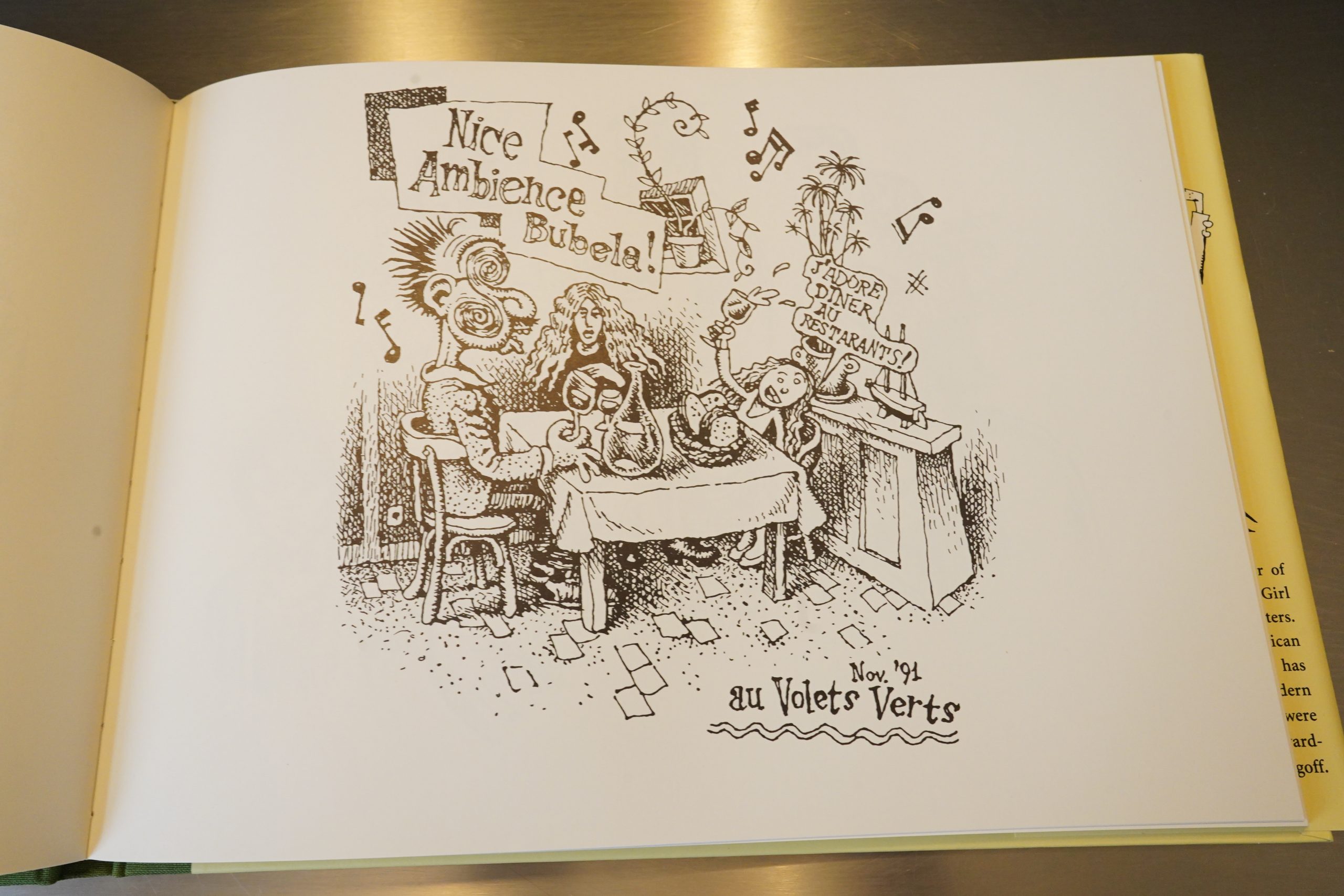

parables into gag-fests, complete with lov-

ingly rendered gore, big-butted fräuleins,

scrawny protagonists and ironically retro

splash pages.

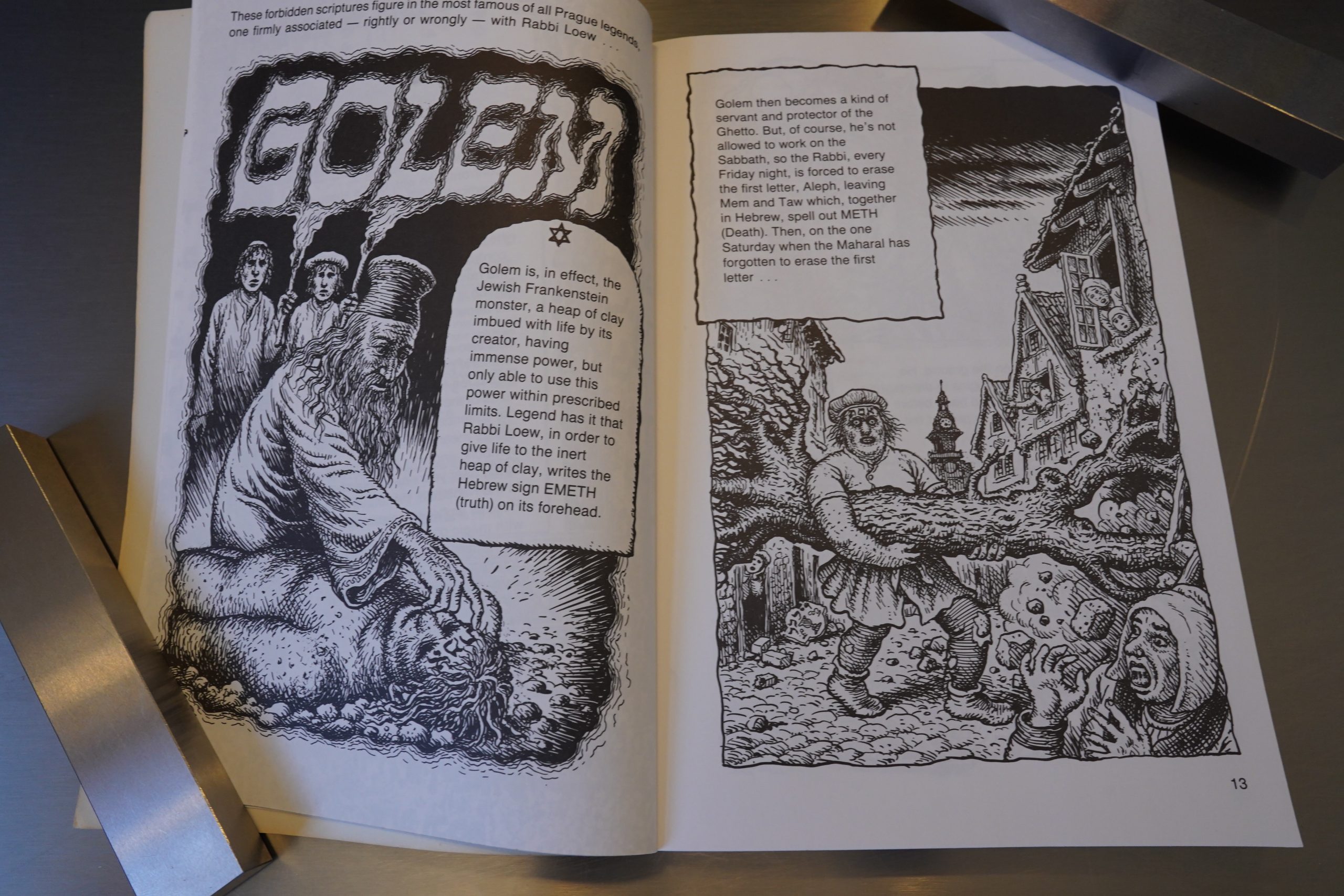

Not to be left out. writer David Mairow-

itz also does his bone-headed best to turn his

subject into his collaborator. For Mairowitz,

Kafka’s life and art must, like Crumb’s, be

Obviously and everywhere intertwined, and

if the facts don’t fit, well, to hell With them.

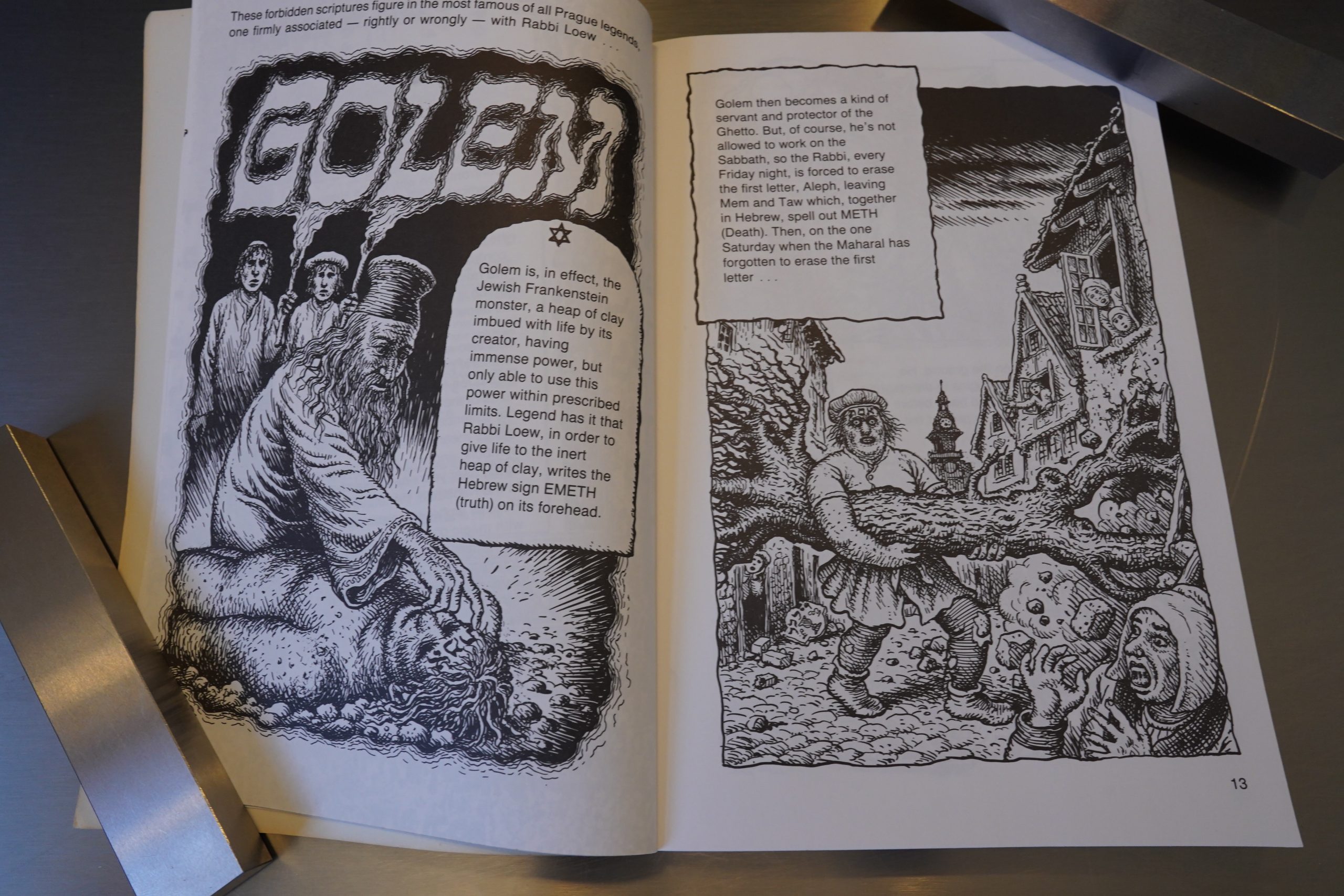

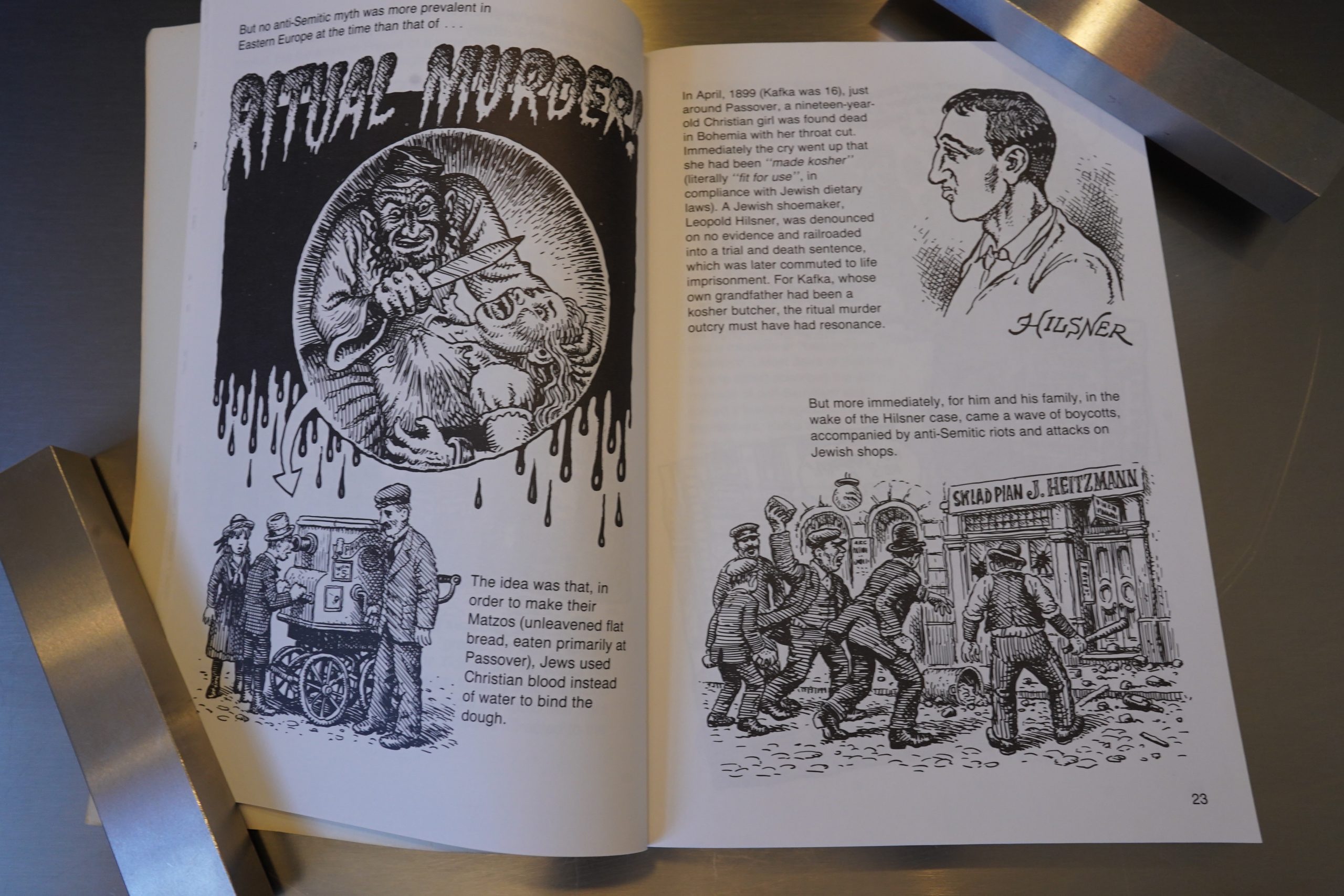

Mairowitz is, for example, desperate to link

Kafka’s writing with his Judaism, so he sen-

tentiously retells that hoary folk tale about

the Golem — only to end by admitting that

there’s no evidence that Kafka even knew the

Story.

Heh heh heh; I love it.

Most irritating, though, is Mairowitz’s

knee-jerk tendency to treat Kafka’s art as a

confessional expression Of neurotic symp-

toms, rather than as conscious craft. For

example, Mairowitz notes that Kalka did

not want an insect pictured on the cover of

“Metamorphosis.” the famous novella in

which a man turns into a bug. Mairowitz

explains this reticence by descending into

inane psychobabble, speculating that re-

jecting the picture was a way for Kafka to

mentally “contain the horror of the trans-

formation” or that it was necessary because

“the line between [Kafka’s) feelings about

his body in human form and its ‘insecthood’

was not all that clear.” In the first place, what

rot And, in the second, couldn’t we at least

consider the possibility that one of the most

careful writers in the history of the world

made his aesthetic decisions for, y’know,

aesthe tic reasons?

Don’t get me wrong: I’m Sure that the

links between Kafka’s Judaism, his psychol-

ogy and his art, have been analyzed in many

insightful volumes. This just isn’t one of

them. If you can’t get enough of Crumb be-

ing Crumb, then by all means, pick this up.

But ifyou want to know about Kafka’s life

well, I’d try Wikipedia first.

That’s a brilliant review.

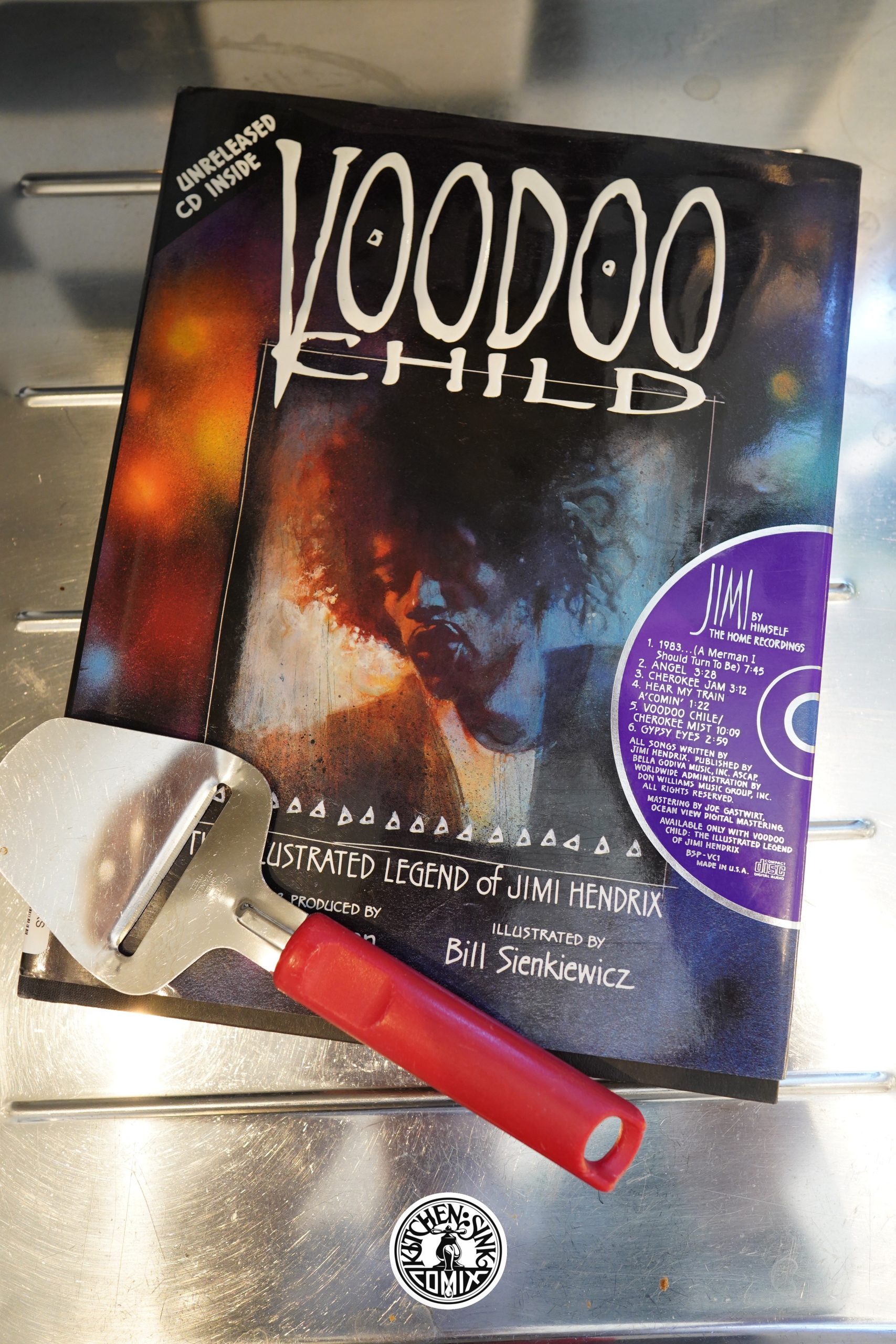

This is the two hundred and thirty-third post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.