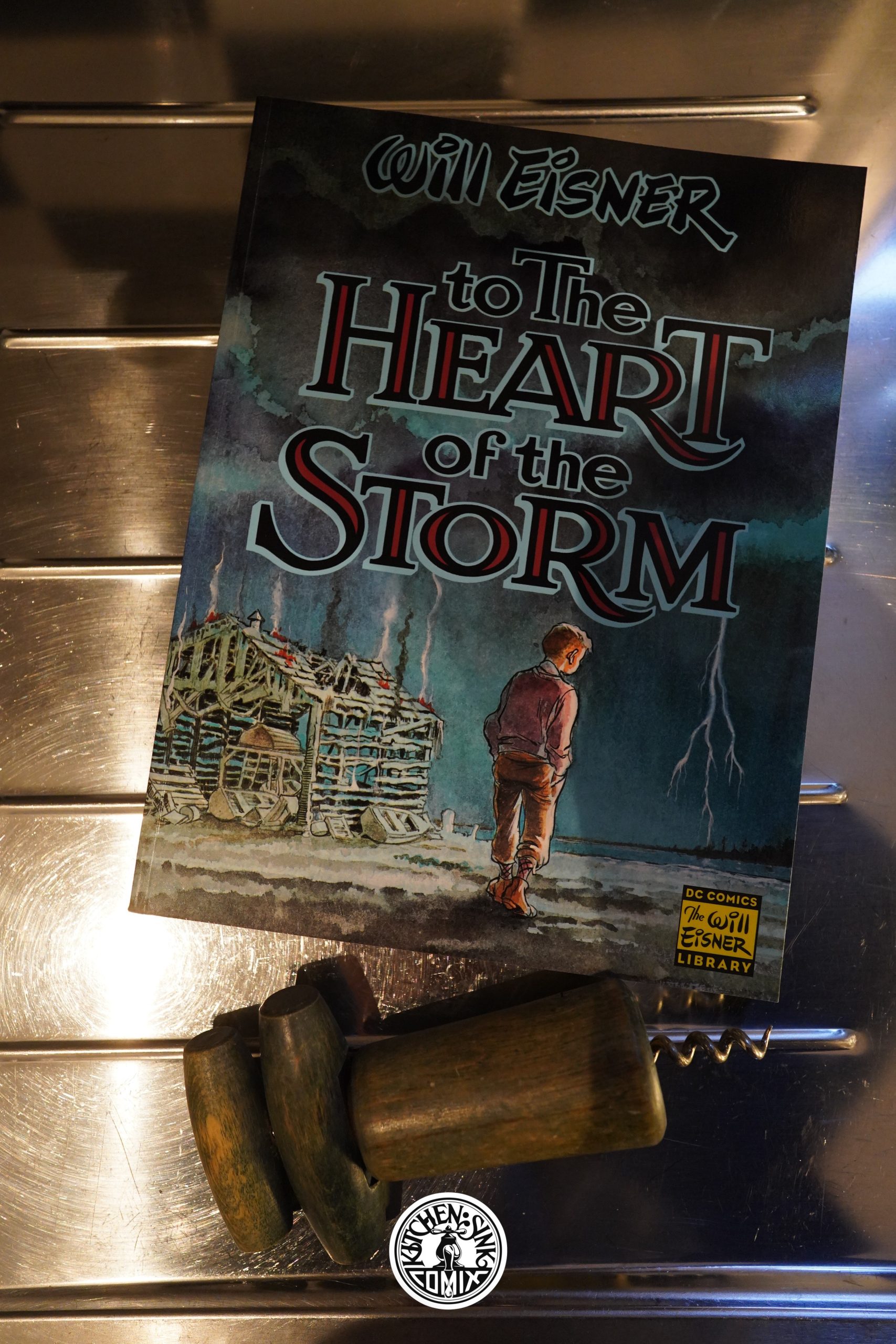

To the Heart of the Storm (1991) by Will Eisner

Oops! I’ve got the DC edition of this book here instead of the earlier Kitchen Sink version…

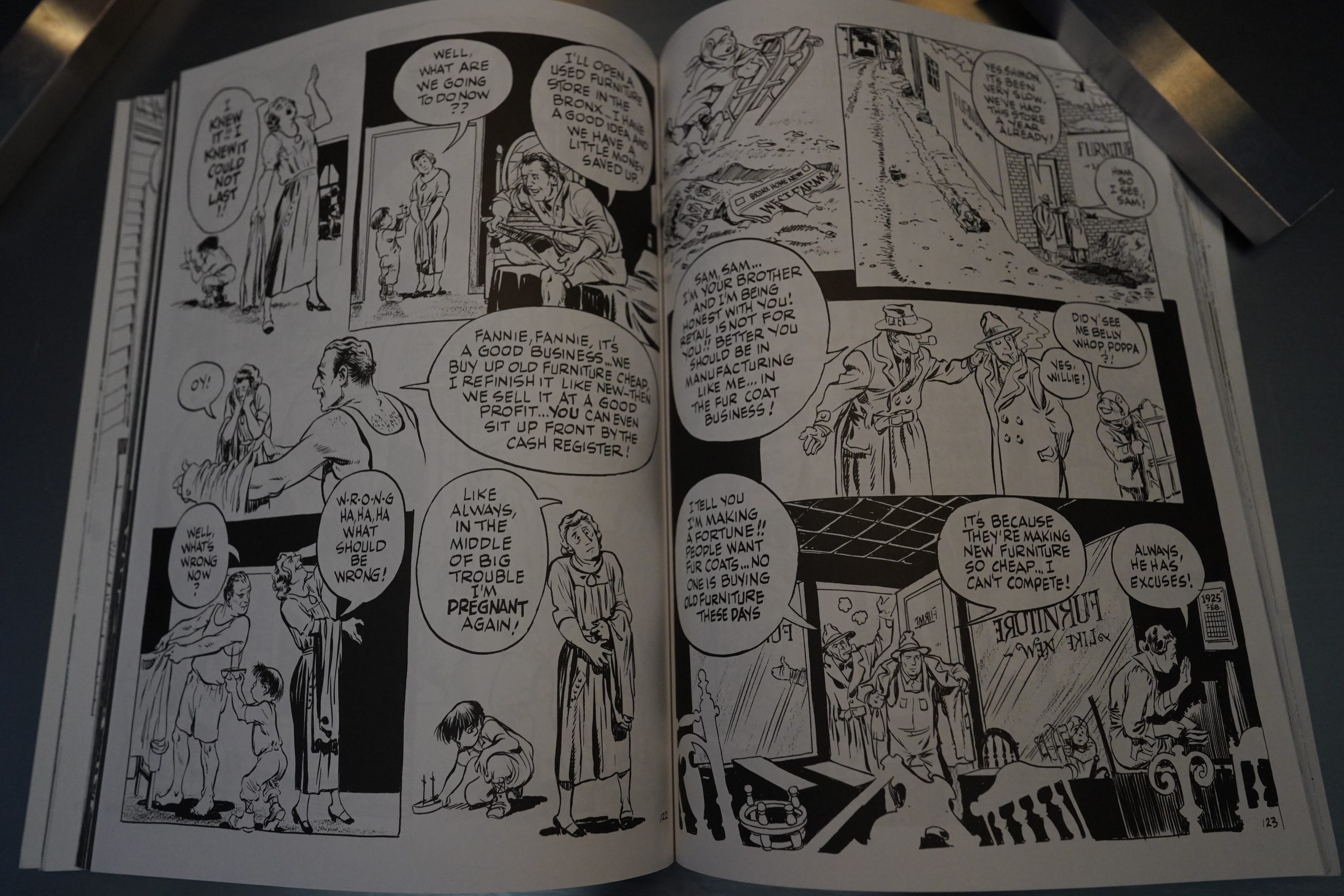

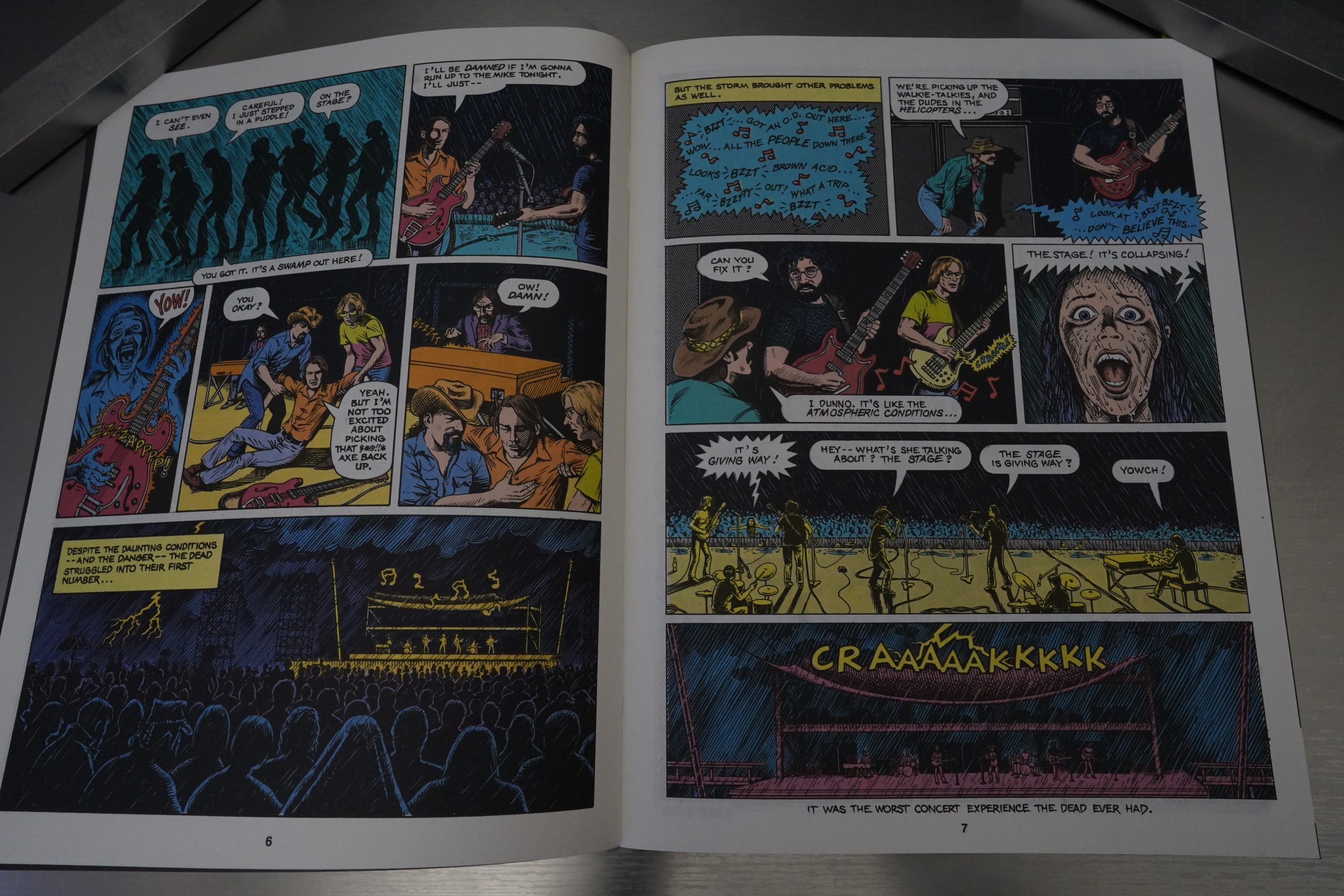

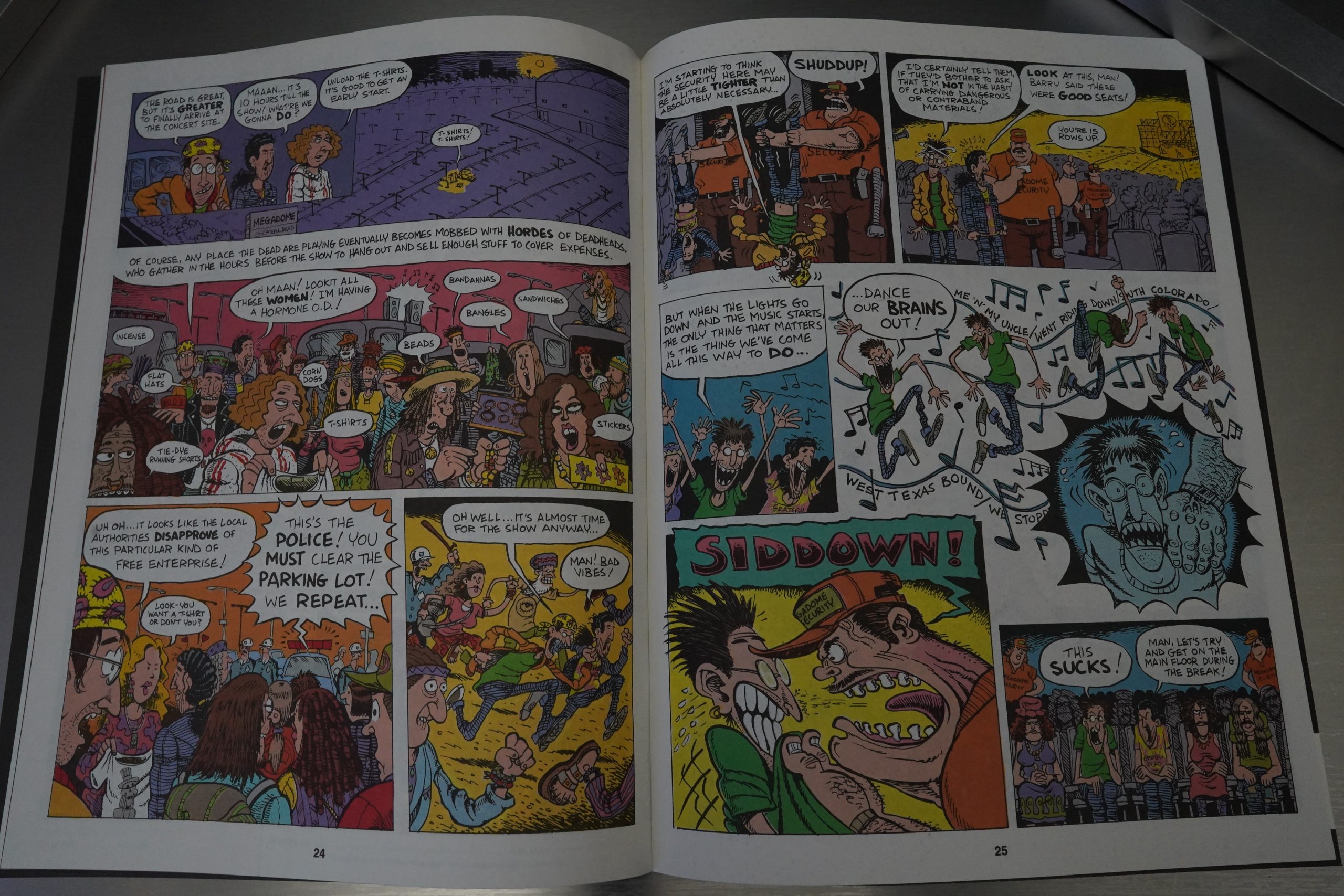

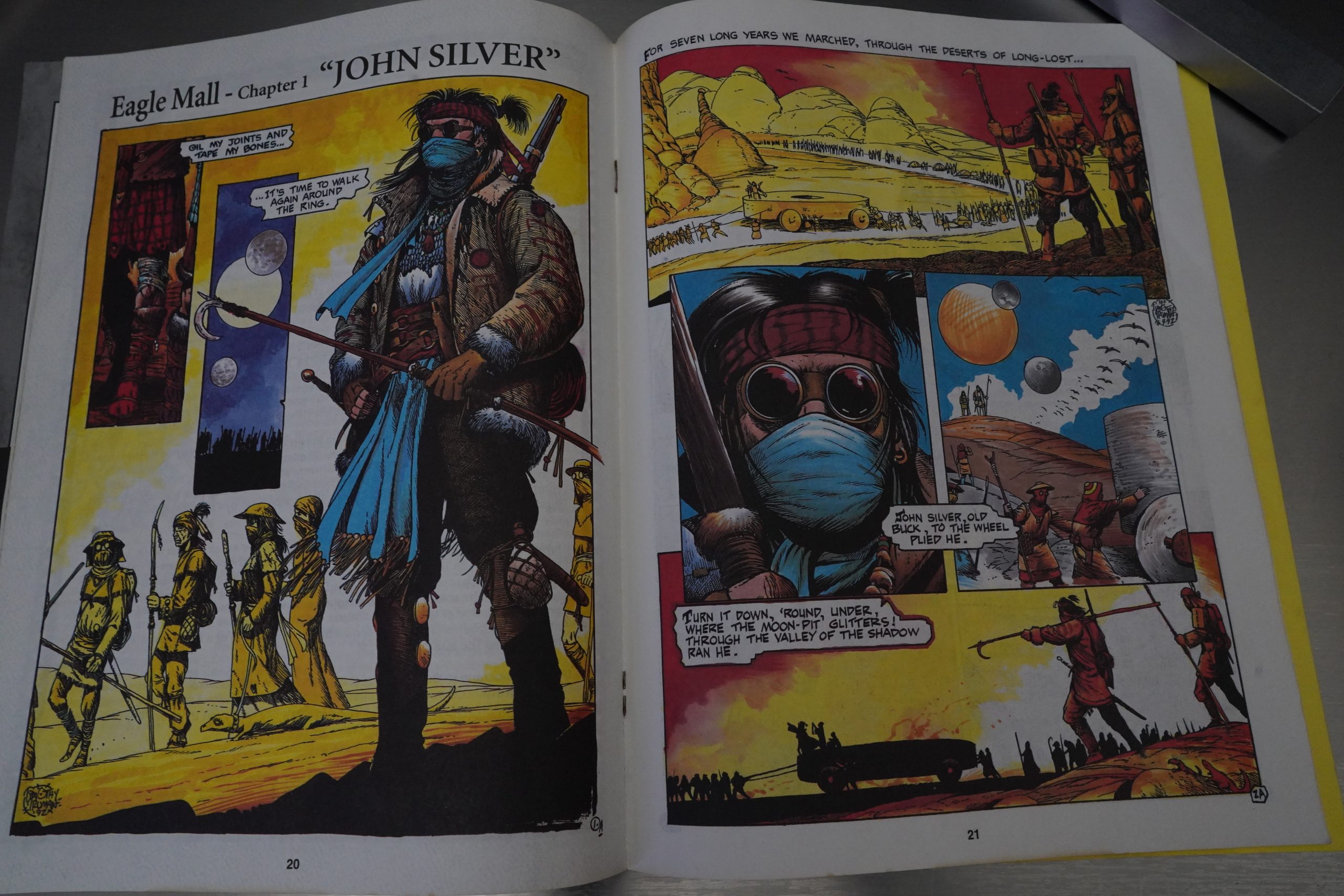

This feels, in some ways, like Eisner’s magnum opus — it covers the same ground as he’s done before, but more thoroughly. And this time over, it’s presented as one single tale, instead of a series of vignettes.

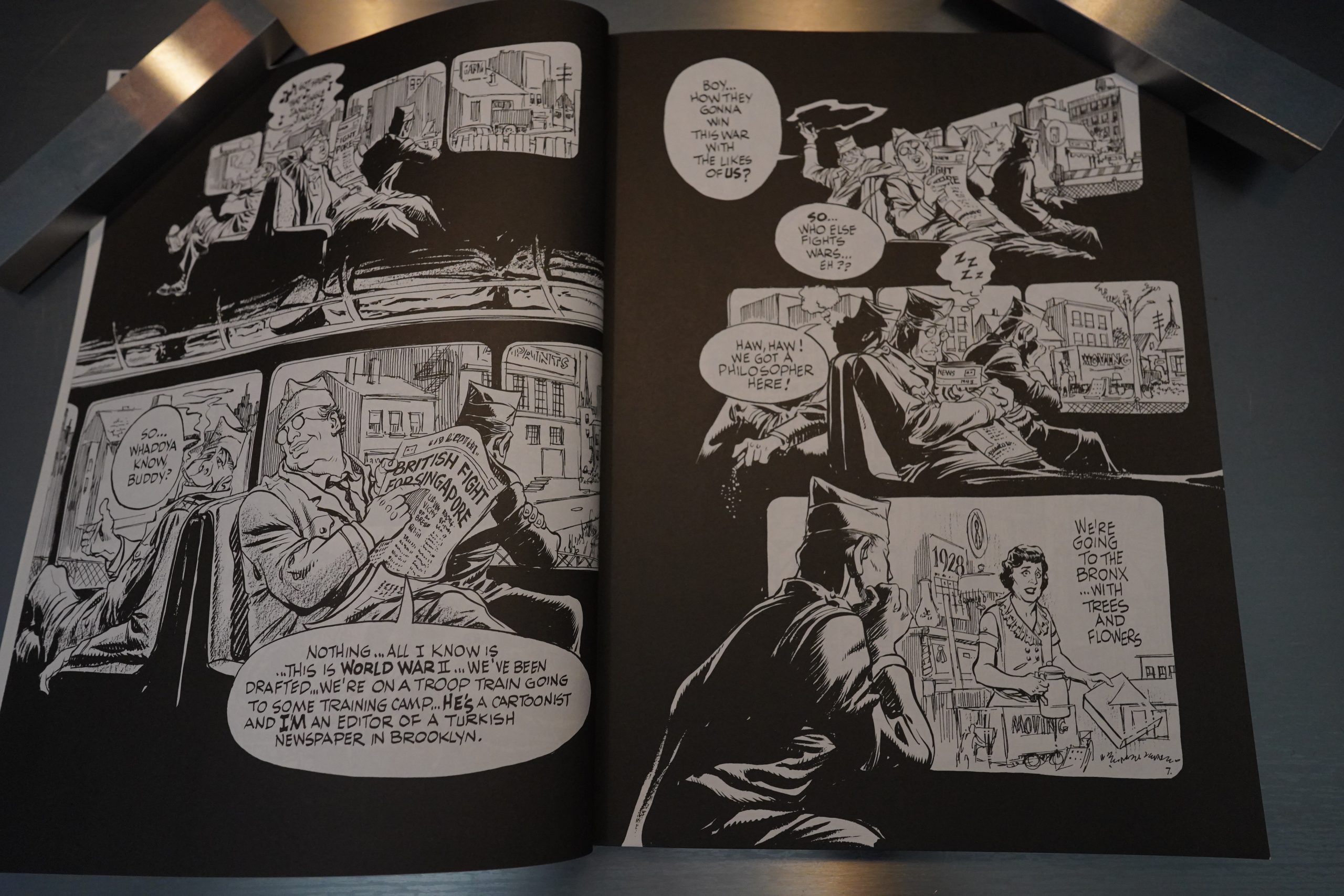

The structure is classic — Eisner has been drafted in 1942, and on the train down to camp, he’s thinking about olden times. (Well, I’m assuming “Willie” is Will Eisner — the book doesn’t say whether it’s fiction or autobiography.)

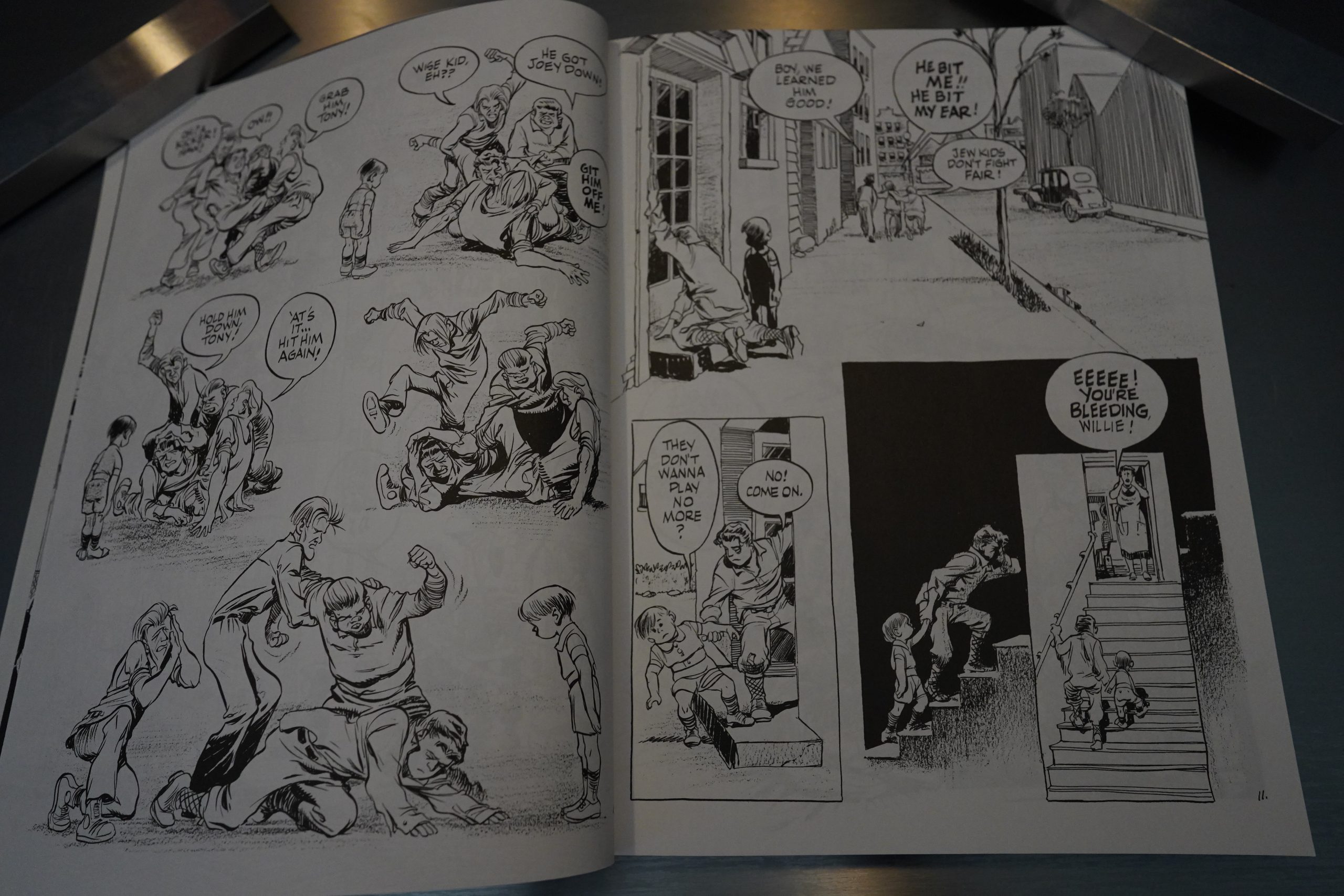

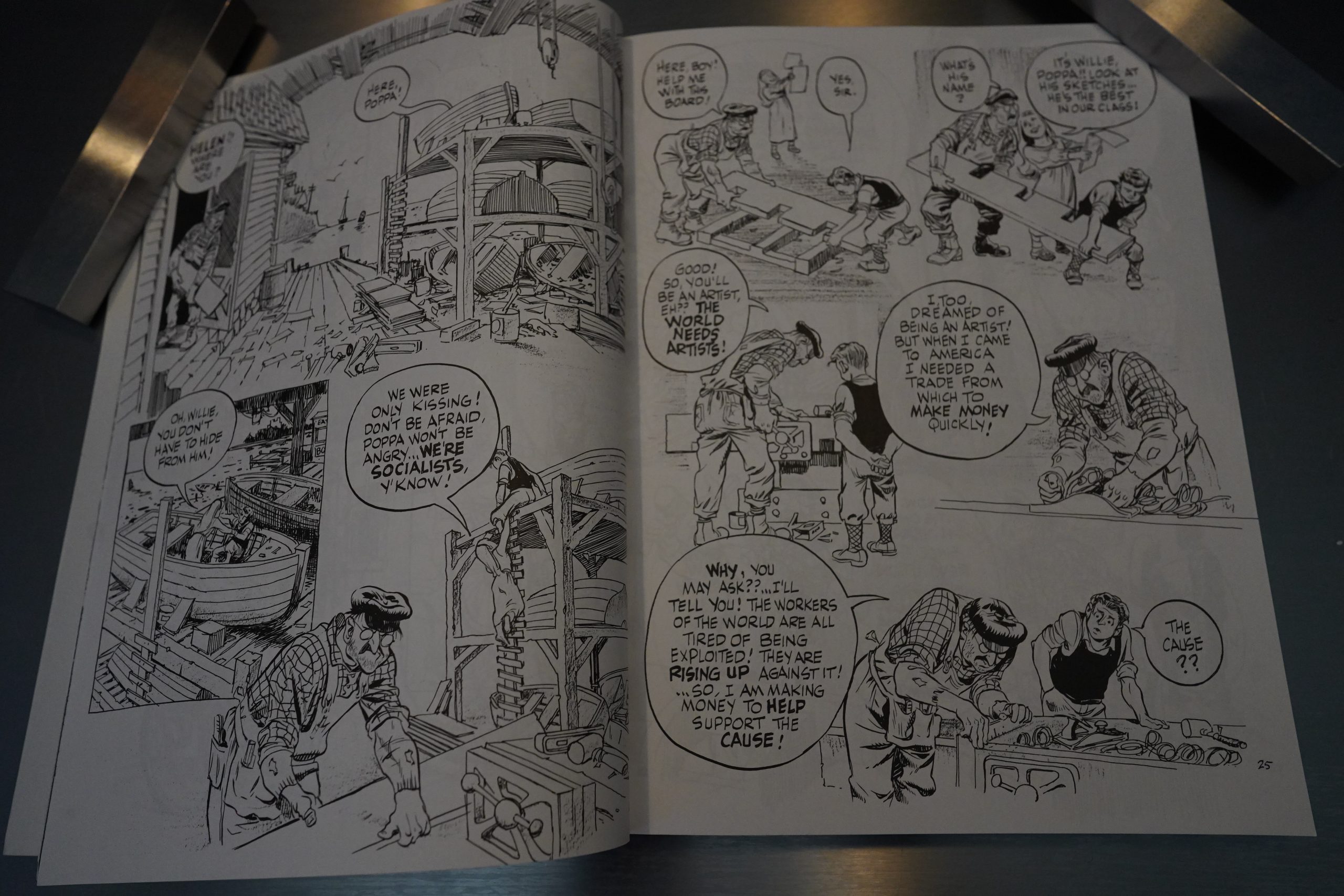

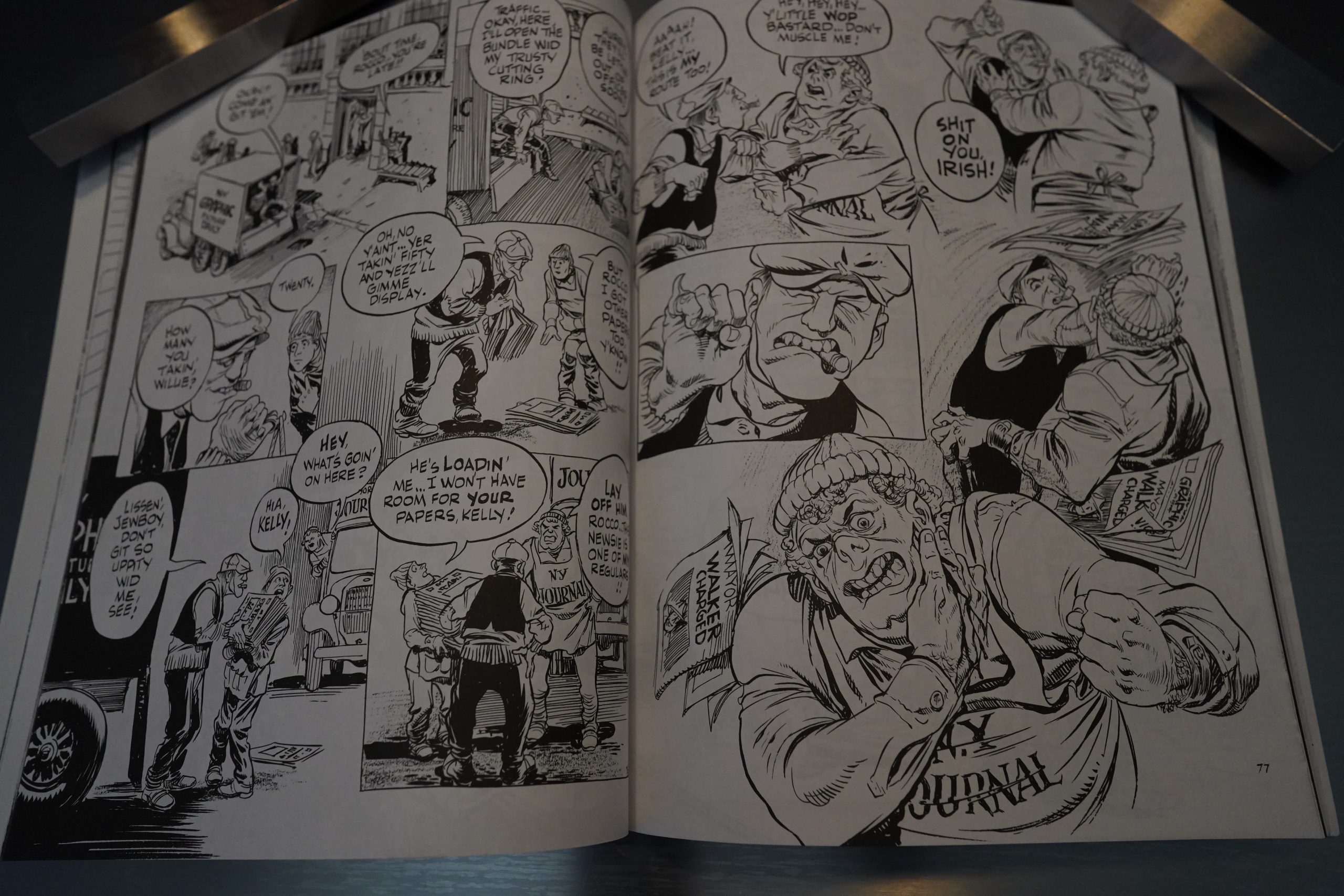

And we get… a bunch of vignettes from Eisner’s life — quite a lot from his childhood, and some from his teenage years. But these aren’t random vignettes: They’re (almost all) on the theme of living as a Jewish boy in New York, and the prejudices and abuse he suffered.

Finally somebody sensible!

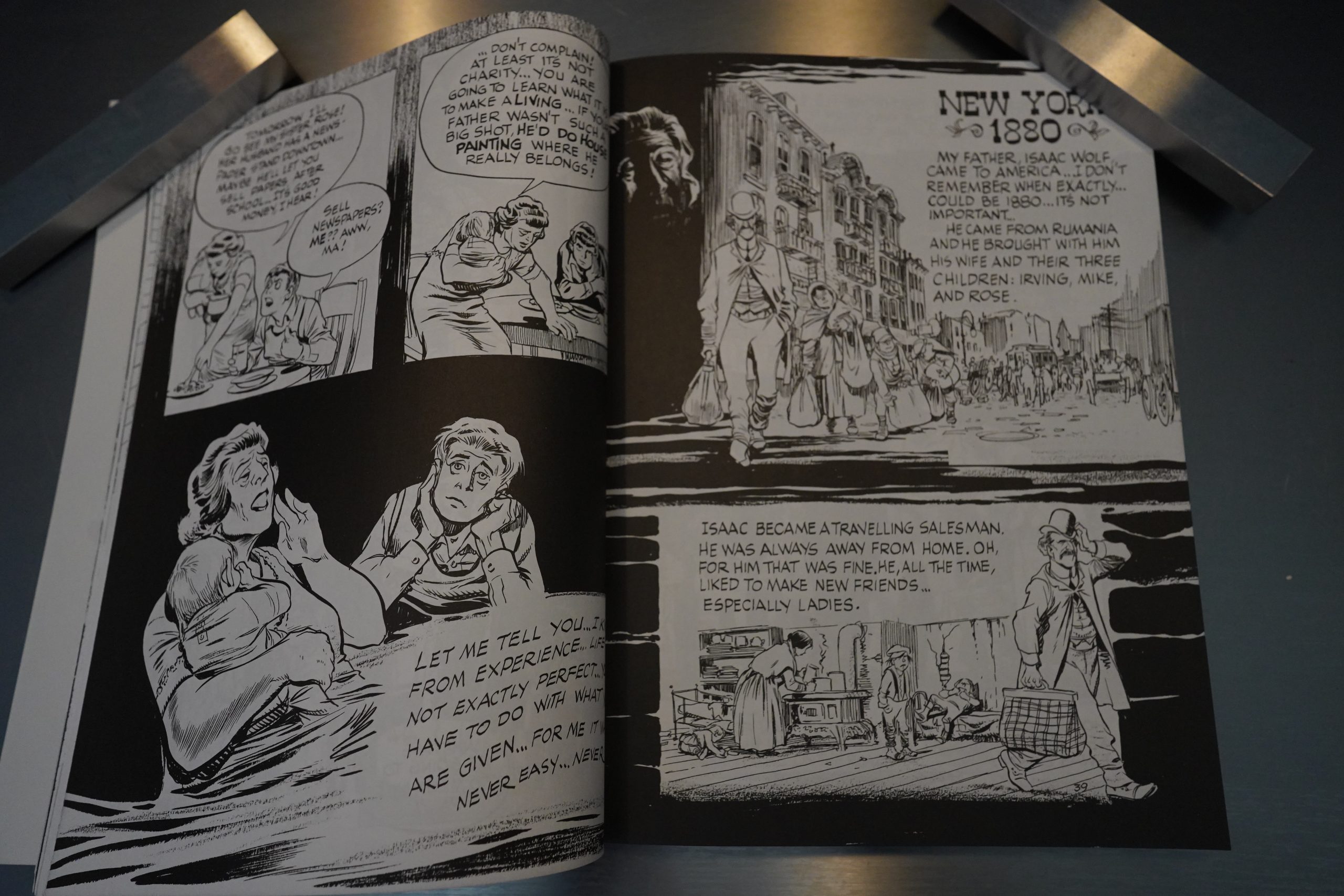

So it seemed like we were going to have something more focused than Eisner’s usual books, but nope: We then get a whole bunch of flashbacks inside the flashbacks to Eisner’s parents, and their parents even. And it’s not that the individual anecdotes aren’t interesting — but there’s just a lot of them. So it’s a book without any momentum, and is instead a contemplative, kinda quiet book.

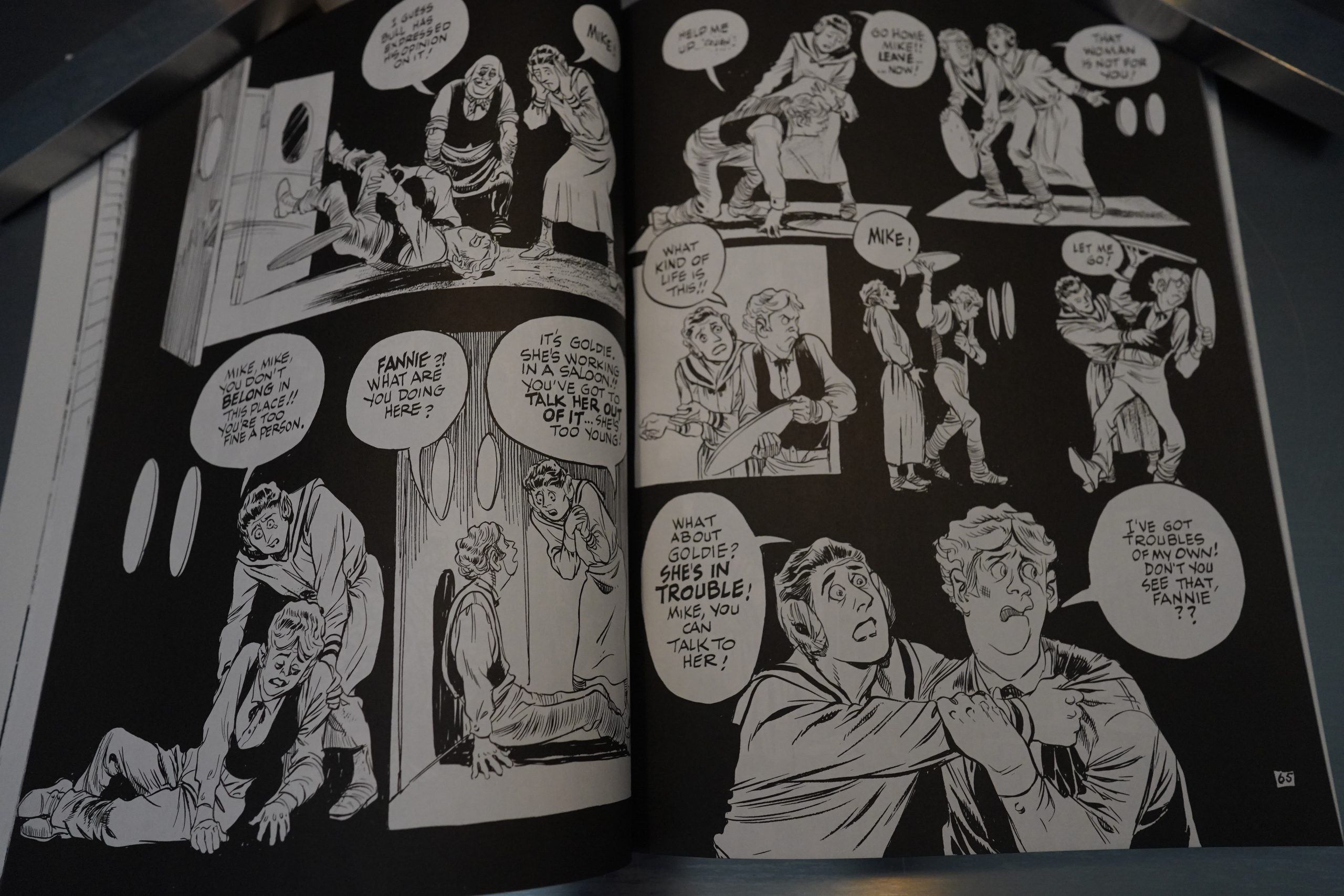

Except for the melodrama. Oh, so much melodrama. It gets a bit hard to take after a while — the family suffers so many setbacks that it gets a bit difficult to take seriously after a while.

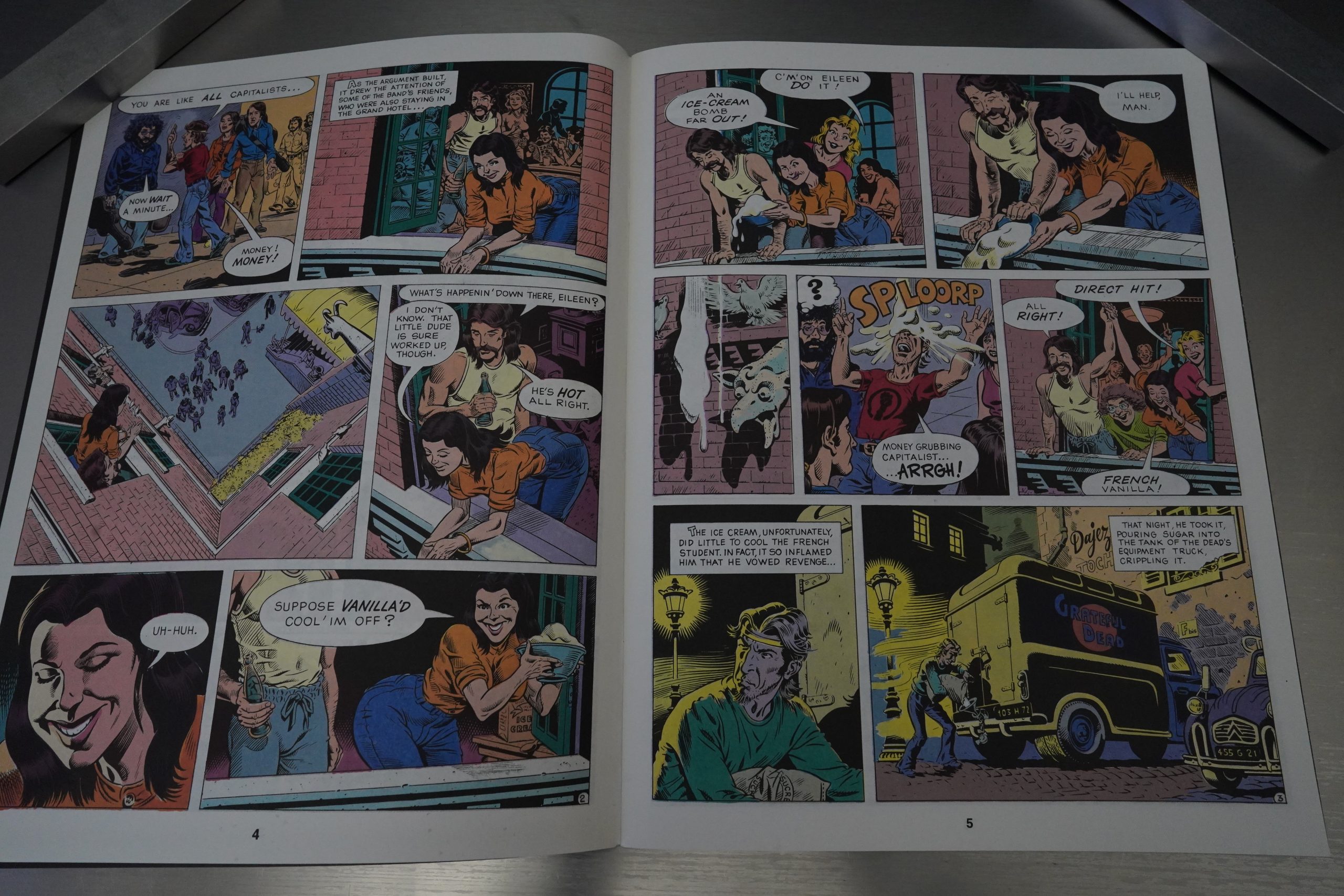

There’s interesting stuff all along, though, like the on-ground newspaper distribution wars here.

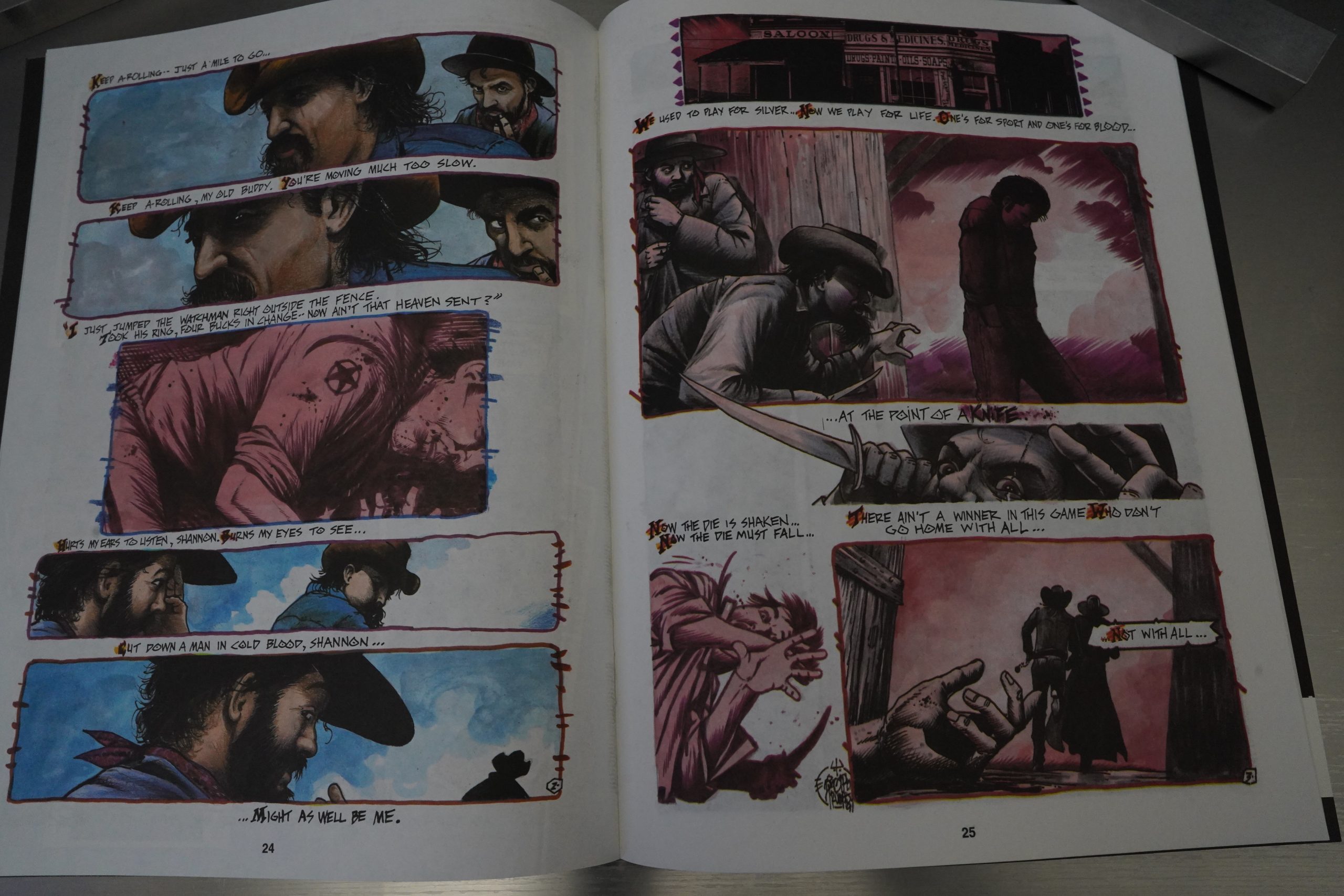

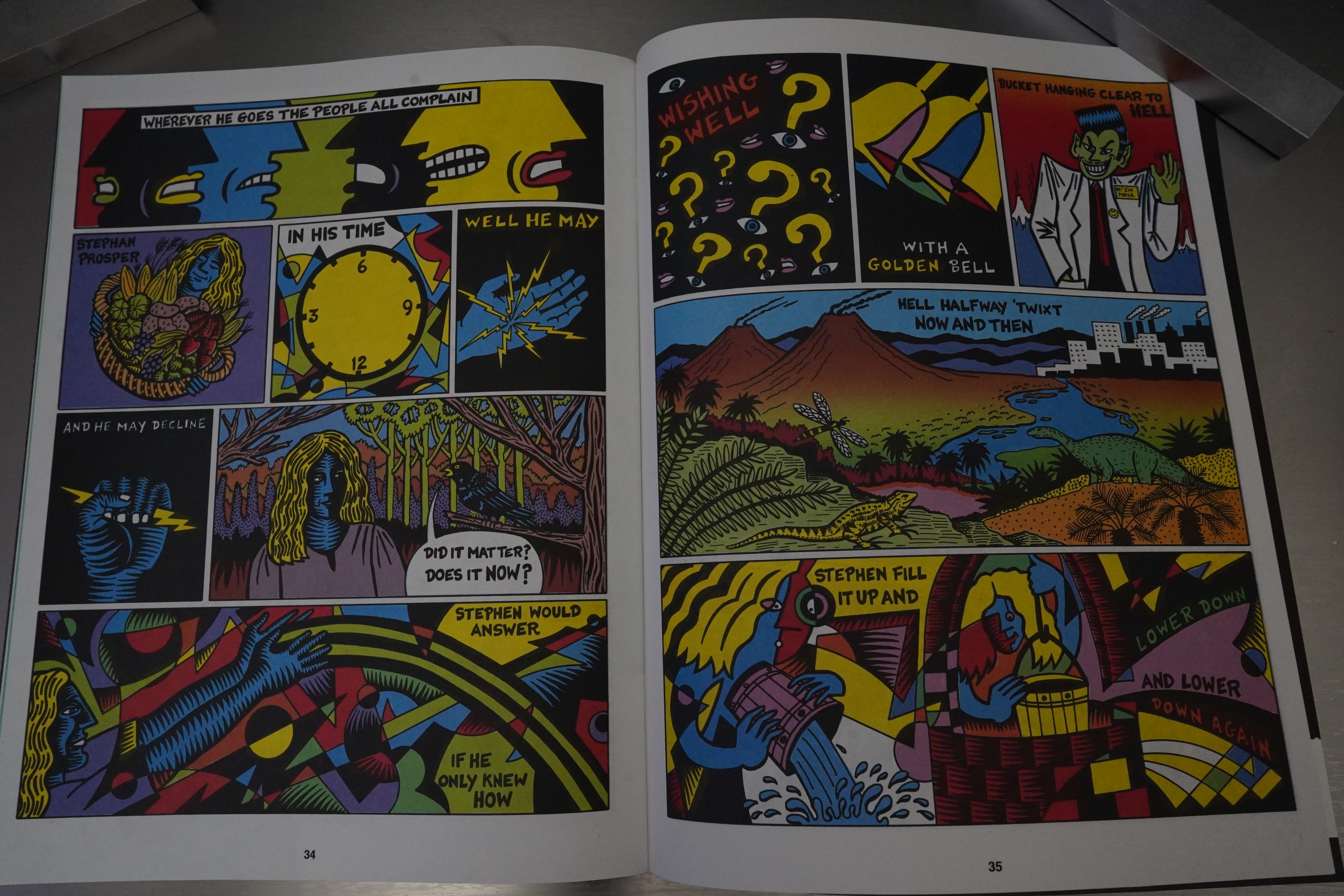

Eisner shifts between doing free-flowing layouts without (clear) panels, to doing more traditional layouts, apparently on a whim. But it reads well — it’s got a nice flow.

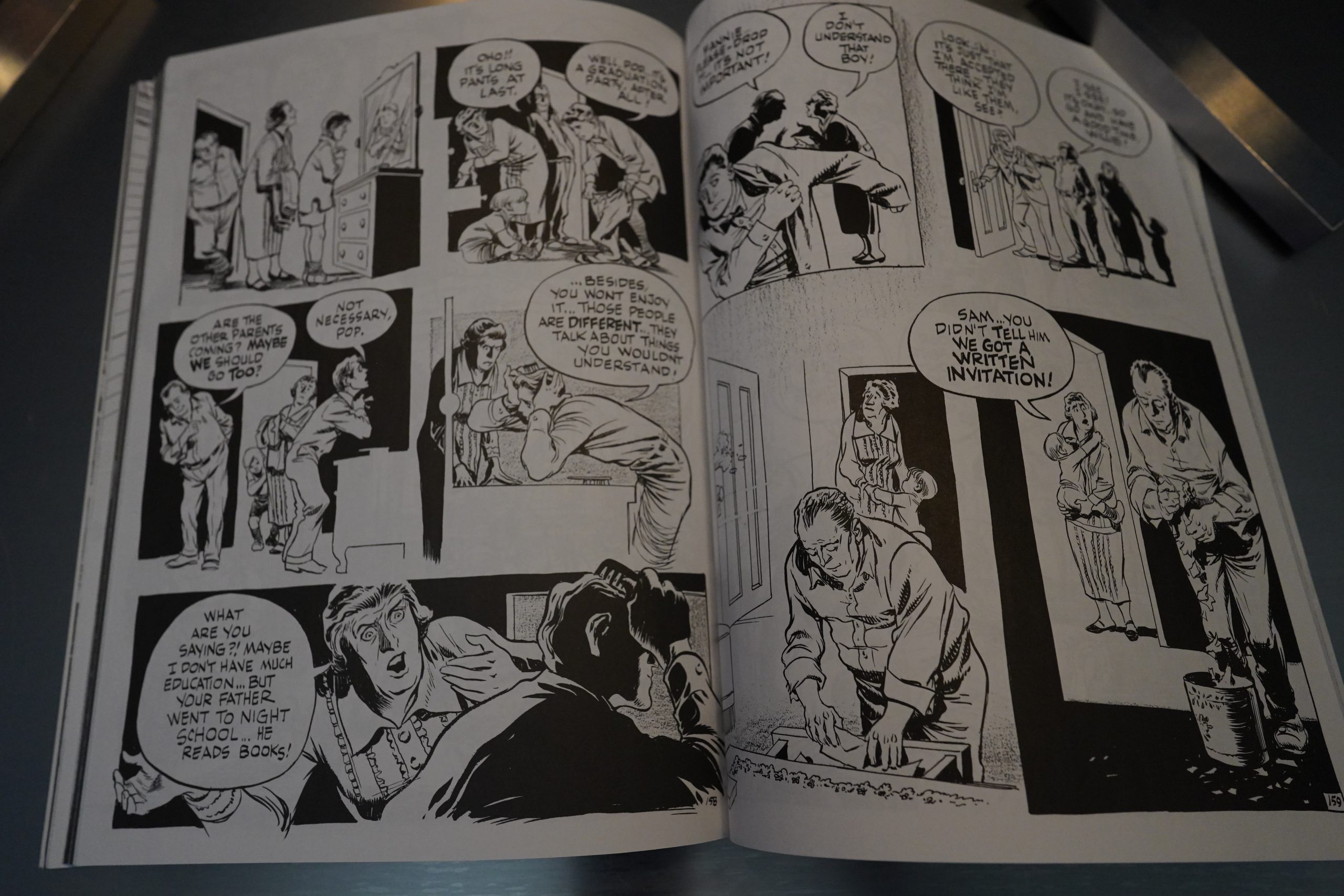

Eisner is pretty reticent about including really embarrassing stuff here (as autobiographies go), but the bit about passing as a gentile to go to a German girls’ prom thing (and disinviting his own parents) is shockingly heartbreaking.

So… I think this might be one of Eisner’s most successful works — it’s structurally sound, and has real flow, and doesn’t any of the many 40s schlock twists and turns that mar much of his other work. But it’s not exactly a thrilling book: It feels somewhat self-indulgent. Not all of the anecdotes we get are all that interesting.

Rob Rodi writes in The Comics Journal #144, page 45:

Will Eisner honed his craft, and

what many would call his art (l “Ouldn’t dis-

agree) on the seven-page Spirit sections he

created for Sunday newspapers during the 1940s

and 1950s. He became an expert at conveying

much more than was actually on the page; his

works were little miracles Of succinctness.

Thirty-odd years later, that’s still where his

greatness lies; the shorter the works, the bet-

ter. His first collection of non-genre stories, A

Contract with God, is very fine, and City Peo-

ple’s Notebook and New York: The Big City, two

recent volumes of even briefer pieces (often

nothing more than observations) are his most

graceful and powerful works to date; some

of the vignettes achieve an almost mythic

transcendence.

So it’s not surprising that To the Heart ofthe

Storm, his years-in-the-making, 208-page,

quasi-autobiographical graphic “novel,” should

prove to be such a disappointment; it plays to

his weaknesses. Its rambling. episodic structure

leads the reader in too many different directions,

and while certain sequences are memorable,

they don’t cohere into a thematic whole. Liber-

ated from page-count restrictions, the master Of

economic storytelling has no idea what to do.

The confusion starts almost immediately.

The title of the work suggests an inexorable des-

cent into sound and fury — and the kind of

sound and fury we’re expecting is war (World

War II, to be exact). After all, on the first page,

we’re given a look (in a rather uninspired

documentary fashion) at the induction of raw

recruits into the armed services in 1942. “It was

a time of thunder and lightning” is the opening

line, and though your eyes may fog a little at

so cliched a metaphor, at least you’re pretty sure

where you’re being led. And sure enough, the

next pages find us on a train heading south with

a couple of newly enlisted men. We don’t know

much about them, until someone in an adjoin-

ing seat turns and asks one of them, “Whad-

daya know, buddy?” and gets the reply, “All I

know is…This is World War II…We’ve been

drafted.. .We’re on a troop train going to some

training camp…He’s a cartoonist and I’m an

editor of a Turkish newspaper in Brooklyn.” (All

of which kind of reminds me of the get-it-out-

of-the-way-in-one-breath backstory you’d hear

characters spout at the beginning of ’40s “B”

pictures, except I don’t think even they were

quite so blatant about it.)

But then, instead of following these draftees

to their destinations and then on to Europe and

war, we’re almost immediately sidetracked by

an extended flashback sequence, as played out

in the window of the train that a draftee named

Willie (the Eisner character) is staring into. The

flashback takes place in 1928, and recounts Wil-

ly’s family’s move from Brooklyn to the Bronx,

where, Willie’s mother warns, Jews musn’t feel

too safe, as there are “Italians, Irishers, and

Only knows what else on the block.” Despite the

warning, Willie promptly gets into a fight with

some local toughs, after which his father

demonstrates that a Jew needn’t fight — he can

always think and talk his way out of a potential-

ly dangerous situation. The sequence is cute;

but what, you uonder, is it doing here? You ask,

when do we get back to the war?

The answer is, we don’t; every flashback

leads to another flashback — there are even

flashbacks-within-flashbacks — which collec-

tively comprise a nonlinear history Of Willy’s

family. The focus, in most of these (but not all),

is on the way anti-Semitism permeated our

culture in the early decades of the century, and

of the ways immigrant and first-generation

American Jews dealt (or avoided dealing) with

such oppression.

Eisner is often very affecting on this theme,

especially in the story Of Willie’s summer-long

toil at building a sailboat with his best friend,

Buck (a Gentile of German ancestry). While the

noisy politics Of race obsess the boys’

tive families, the boys themselves become in-

creasingly and pleasurably immersed in their

project, oblivious (or nearly so) to all the

ruckus. The pacing the tone of this sequence

are exactly right; it’s one of the best represen-

tations of a pure boyhood friendship (the kind

men can’t have, because they’ve learned about

status and money and power) that I’ve seen in

this medium. Eisner conveys Willie and Buck’s

golden afternoon with perfect control and a

sureness of touch.

But virtually all the other sequences are

simply overwrought —

particularly the

flashback-within-a-flashback in which Willie’s

mother tells him the story of her life. (“Let me

tell you,” she moans, “I know from experi-

ence… life is not exactly perfect.. .you have to

do with what you given. . .for me it was

never easy.. .never.. ..”And that’s just the se-

gue.) I’ll give Eisner the benefit of the doubt

and presume that the litany of oppressions that

constitute Willie’s mother’s life conforms to the

hard facts Of Eisner’s (Nn mother’s life; but the

tenor of that life has here been hyped up to an

almost hysterical degree — it comes off as a kind

of melodramatic binge. As her troubles magniW,

Fannie Wolf clutches her breast, she to her

knees, she raises her hands in supplication to

those who might help her. She’s a vulnerable

innocent in a hard, cruel world, ami we’re PNC-

tically exhorted to weep for her. But the fever

pitch of the narrative subverts any sympathy we

might have for her; I found myself remember-

ing Oscar Wilde’s remark on Dickens’s The Old

Curiosity Shop: “One would need a heart Of

stone not to laugh at the death of Little Nell.”

The problem here is that the exaggerated,

cynical cartoon vocabulary that Eisner invented

so many years ago works for his ironic,

comic Spirit stories (and for his short urban

anecdotes), but it’s not remotely suited for

anything resembling an epic Or a saga. Every

artist has limitations, and maybe Eisner simply

hasn’t come up against his before; but just as

Damon Runyon couldn’t have written Anna

Karenina, Eisner can’t pull off the kind of thing

he’s trying for here — it’s beyond his range.[…]

So, To the Heart of rhe Storm doesn’t take

us into the heart of a storm at all — the best

it can manage is a couple of quick cloudbursts.

Had Eisner presented this as a stream-of-

consciousness memoir, or a kind of folk family

history, it might have gone down more easily;

but its pretensions sink it. What is the purpose

of the framing sequence (Willie on the troop

train heading toward boot camp)? Why is the

title of the work To the Heart of the Storm? Is

Eisner really suggesting that American anti-

Semitism Or ethnic separatism was a cause of

the Second World War? Your guess is as good

as mine. (If he thinks it is, he needs to give us

more proof.)

Eisner himself explains how this confusion

came about in his introduction: “I intended to

deliver a narrowly fictional experience of that

(pre-war) climate, but in the end, it metamor-

phosed into a thinly-disguised autobiography.”

Why, then, keep us pointed at the “Storm” in

Europe if the only storm he’s going to show us

is the teapot variety?[…]

I don’t mean to dismiss Eisner as an old

master who can’t learn new tricks (a label that

seems, sadly, to apply to Harvey Kurtzman); his

range may be limited, but there is plenty to ex-

plore within that range — besides which, the

autobiographical form has sabotaged other

writers and artists (Ray Bradbury and Federico

Fellini come to mind). It tempts them with the

sort of excesses of sentimentality they otherwise

would have enough objective distance to avoid.

I can’t believe, for instance, that Eisner would

have made Fannie into such an impossibly vir-

tuous cipher if the character hadn’t been based

on his mother. We’re only shown her suffering

and endurance; we never feel any identification

for her — we never even know whether she loves

(or has ever loved) her husband

Well… I think that’s a fair review, but I disagree with some of it.

Bruce Canwell writes in Amazing Heroes #191, page 112:

Only Eisner’s youthful counterpart

Willie is able to avoid the mistakes of

his father: in World War I Sam Eisner

immigrated from Austria to America

to avoid conscription, then he married

shortly after attaining citizenship to

avoid the U.S. military draft. But

when Willie is called upon to serve

during World War II he refuses all the

available dodges and reports for

duty—he is determined to face the

unknown rather than perpetuate old

ways, old mistakes; Only when a

person can make such a decision is he

truly an adult; only then can he break

the vicious cycle of bigotry.

The story is richly textured, the art

is fluid and full offemotion—united,

they turn To the Heart of the Storm

into a major comics experience, a fit-

ting companion to Eisner’s A Contract

with God, A Life Force, and that most

underappreciated graphic novel, The

Dreamer.

If there is any justice in the world,

Mr. Kitchen and Mr. Eisner are gonna

sell a lot of copies of this one… •

The Comics Journal #146, page 11:

You Eisner-

Basher, You

RANDY REYNALDOOf all the “Eisner-bashing” I’ve seen

in the Comics Journal in the last couple of years,

I was compelled to comment on Rob Rodi’s

negative review of Will Eisner’s graphic novel,

To The Heart of the storm (Journal #144).

I disagree with Rodi’s assertion that the book

doesn’t cohere to a “thematic whole.” Many of

the flashback sequences recounted in the graphic

novel not only underscore Eisner’s theme of

anti-Semitism (as well as racism and prejudice

on a larger scale) , but also demonstrate how they

shaped him as an artist and an adult. Rodi in

his own review points out th… many of the

story’s episodes revolve around “the way that

anti-Semitism permeated our culture in the early

decades of the century.” Furthermore, many of

these scenes are Often echoed throughout the

work, strengthening the cohesion of the story

even more.

Eisner uses America’s entry into World War

II, for instance, to create a parallel between the

son, Willie (Eisner), entering the service and

the father, Sam, •who left Austria at the begin-

ning of WOrld War I to avoid the draft. Although

he too could have avoided the draft, young Willie

decides to enlist because, unlike the father, Wil-

lie is more enfranchised as an American Jew

than his father was as an Austrian Jew. Because

they were only one of Many ethnic groups strug-

gling to establish themselves, Eisner shows that

Jews had more opportunities to integrate into

the mainstream and succeed in the U.S. than in

Austria. Willie’s father welcomed and encour-

aged this integration, sometimes over his wife’s

objections, by choosing to live in non-Jewish

areas and not discouraging Willie to make

friends with non-Jews. As a result, Willie is will-

ing to fight when the U.S. enters the war.

Eisner is not suggesting, however, that this

period was not without its problems; nor, as

Rodi proposes, is Eisner suggesting that “Amer-

ican anti-separatism or ethnic separatism was

a cause of the Second World War.” Instead,

superimposing world War II over Willie’s mem-

ories allows Eisner to demonstrate the irony of

Americans happily going off the war to fight

ethnic-based oppression without realizing that

similar prejudices existed right here at home.

As Rodi points out, young Willie is told that “a

Jew needn’t fight,” but as he matures, Willie

finds out that sometimes there’s no choice,

especially if it’s for a cause one believes in —

even the pacifistic and often compromising

father understood that.

In direct response to one of the questions

raised in Rodi’s review, the purpose of the fram-

ing sequence (the train trip to boot camp) is to

create a metaphoric link to the father’s asser-

tion that “life is a journey” — this too creates

a coherence that ties many of the stories within

the book together. This “journey,” along with

the parents’ own experiences and attitudes, all

contribute to the sum of Willie, the adult.

(A parent’s attitudes can have a negative ef-

fect on an individual as well; when Willie’s

mother tries to convince him that his father is

a failure as a businessman, Willie comes to his

defense by asking his father for business advice,

thus embarrassing his mother. This reverence

Of the father over the mother, which partly

results from the father and son’s similar tem-

peraments, may explain why the mother

sometimes comes across as unsympathetic.)[…]

ROB RODI REPLIES: Randy, I’d like to reply to

your letter at greater length than I’m able to;

unfortunately, once I’d finished with it, I threw

Out the photocopy of To the Heart of the Storm

that was sent to me for review. This was not an

aesthetic decision, but a practical one. The need

for art may be strong, but the need for closet

space is eternal.

Even so, the work is fresh enough in my

mind to allow a few general responses.

First off: you state that “superimposing

World War II over Willie’s memories allows

Eisner to demonstrate the irony of Americans

happily going off to war to fight ethnic-based

[sic] oppression without realizing that similar

prejudices existed right here at home.” But it

isn’t the nur that frames (not superimposes) the

flashback sequences; it’s Willie’s ride on a troop

train. And his fellow recruits aren’t “happily go-

ing off to war” — they seem a bit dazed, if

anything; Willie’s seatmate even gives voice to

the general bewilderment. And, most impor-

tantly, WOrld War II was far more than a fight

against ethnic oppression; Germany’s invasion

and occupation of Austria, France, et al, was

a far greater incentive to fight than the plight

of Jews, Slavs and gypsies under Nazi rule. So

if it was German oppression of ethnic groups

that inspired Willie and his fellow soldiers to

enlist, Eisner should’ve said so.

But, uait — just as To the Heart ofthe Stom

doesn’t cohere, neither, it seems, does your let-

ter. A paragraph later you write that “the pur-

pose of the framing sequence [the train trip to

boot camp] is to create a metaphoric link to the

father’s assertion that ‘life is a journey'”; but

this contradicts what you just said about the pur-

pose of the framing sequences being to demon-

strate the “irony” of ethnic Americans going

abroad to fight ethnic oppression when it exists

in such force at home. Now, I know that in a

sophisticated work of fiction, a narrative device

(such as the train trip) can do thematic double-

duty — but To the Heart of the Storm is far from

a sophisticated work of fiction. Its characters

are leaden, its tone is consistently overwrought,

and its various themes — even presuming you’re

correct in your assertions — are deadeningly

banal: “life is a journey,” “it’s ironic to fight

oppression abroad when it exists at home.”[…]

In the end, I can’t help thinking that you put

more work into analyzing Eisner’s intentions

than Eisner did, which is, I think, a common

failing of critics who approach cartoonists of

Eisner’s stature. His reputation not only sends

many nascent critical sensibilities scampering

away into dark corners, it also inspires even

those who should know better to give him the

benefit of the doubt when they see something

in his work that quite register. “He’s WIII

Eisner; he must have meant to do that,” they’ll

tell themselves. “And if I think hard enough,

I’ll find a reason he could’ve meant it.”

Fortunately, most of the Journal writers are

made of sterner stuff; I think few of us would

deny Eisner’s contributions to the comics me-

dium, but the “Eisner-bashing” you refer to in

these pages is, even so, not a case of lese-

majesre. Eisner is a working cartoonist, and

must continue to be judged as such. If you want

to hear the usual chorus of hosannahs every time

Eisner puts his pen to paper, there are plenty

of publications devoted to slavishness of that

sort; but as a Journal critic, I say a cartoonist

is only as good as his most recent work. It’s up

to those of us who want to see the medium grow

to stand toe to toe with such artists and say,

“What have you done for us lately?”

Harsh!

This book has been reprinted several times. Here’s some reviews on the interwebs:

Ironically, a lot of Eisner’s autobiographical stuff is really boring. He gets into fights with the neighbourhood kids because he’s Jewish, he builds a small boat with a wealthy German kid – ehhh. It’s nothing special.

To the Heart of the Storm isn’t among my favourites of Will Eisner’s books, and I wouldn’t say it’d appeal to anyone but fans, but it’s not a bad read, particularly if you’re in the mood for a Dickensian comic!

Hm:

The one criticism that could possibly be levelled is the simplicity of characters’ approach to situations, which could come across as being stereotyped and formulaic, but equally, could just be the obverse of the energy and straightforward narrative drive of the story. It would rather be like criticising Hamlet for being full of cliches and hackneyed old sayings. It’s a ‘Yes’. Highly recommended.

Hm:

From his denial of Jewish prejudice in America to his determination to escape a cultural stereotype by choosing to fight in World War II, Eisner’s story feels familiar and overlooked. This book comes highly recommended for its high quality narrative and illustrations, as well as the reminder it serves about America’s own history and legacy of continued discrimination during a time period when history books still too often overemphasize the country’s blameless and heroic character.

There sure are a lot of reviews:

We found the way in which the author’s train-travelling alter ego remembers his past to be a little too chaotic though, especially interspersed as it is with further dramatised recollections built from the memories of his parents. This is probably one best left to those with a particular interest in the era or the circumstances in which Eisner grew up, as it left us feeling like we wanted more, that too few conclusions had been drawn. Or perhaps that’s just the way life is.

So… it doesn’t seem to be a generally well-reviewed book — opinions differ more than usual for Eisner.

This is the one hundred and thirty-first post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.