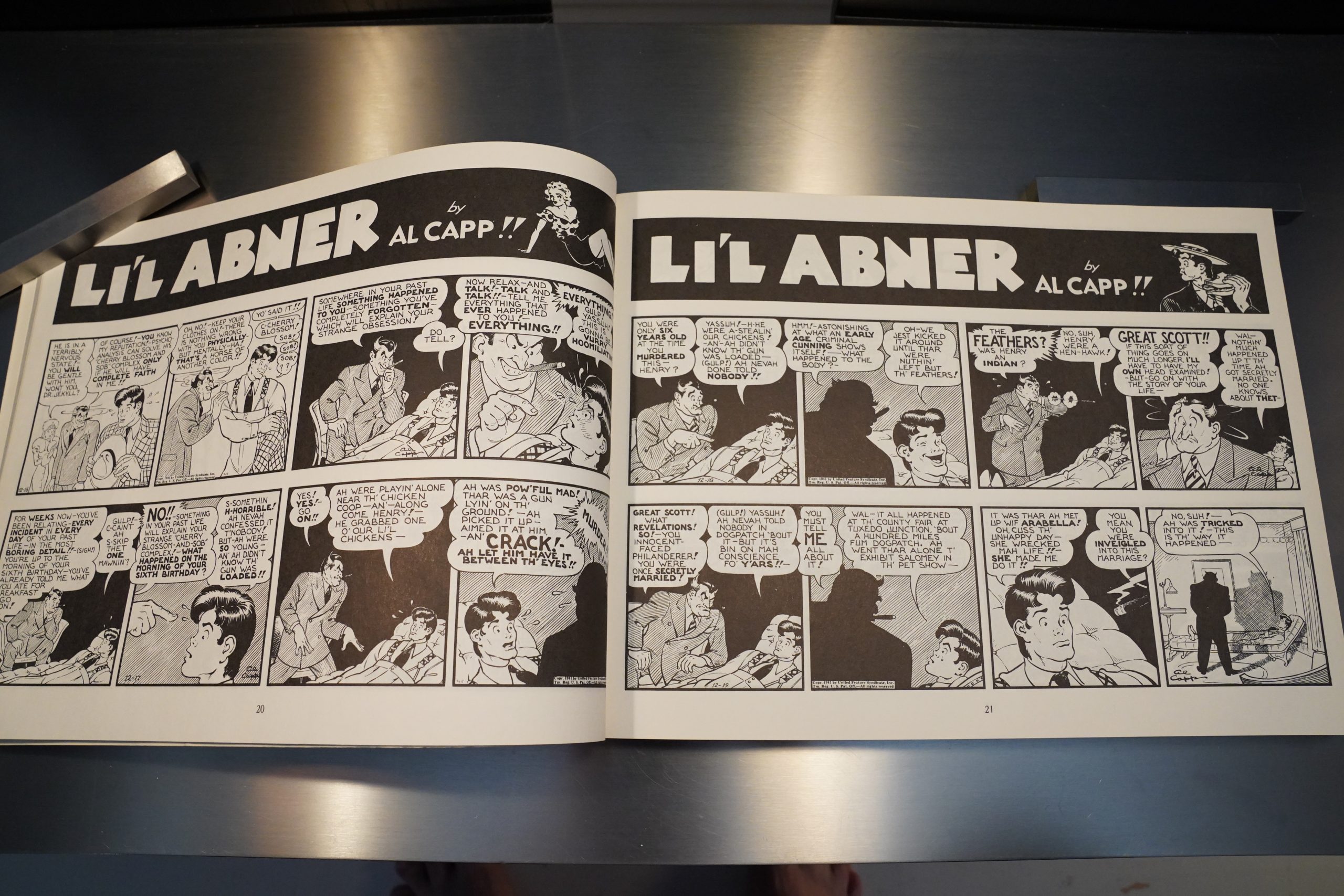

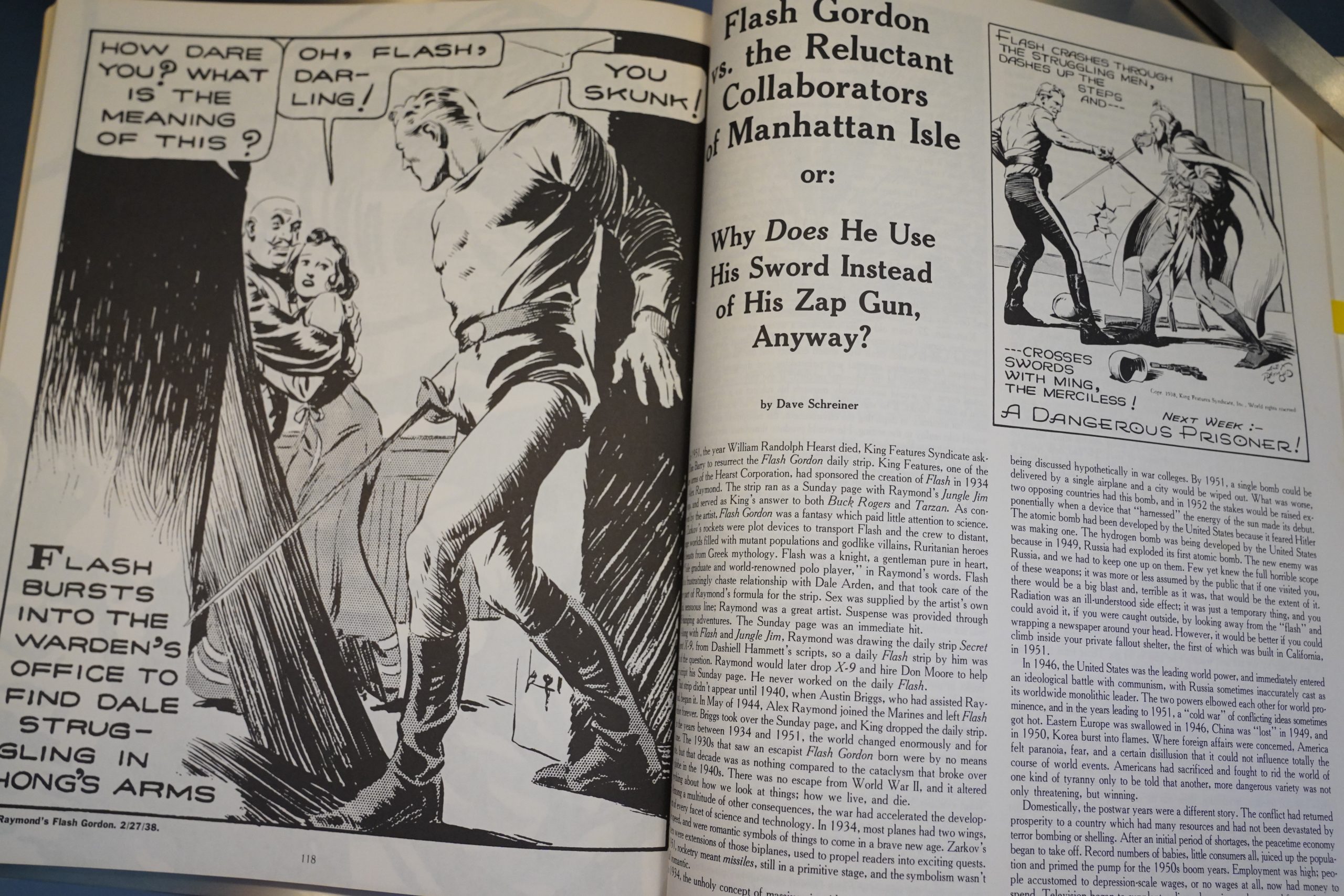

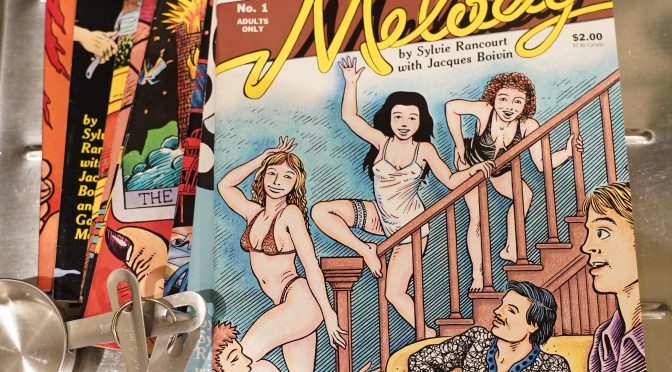

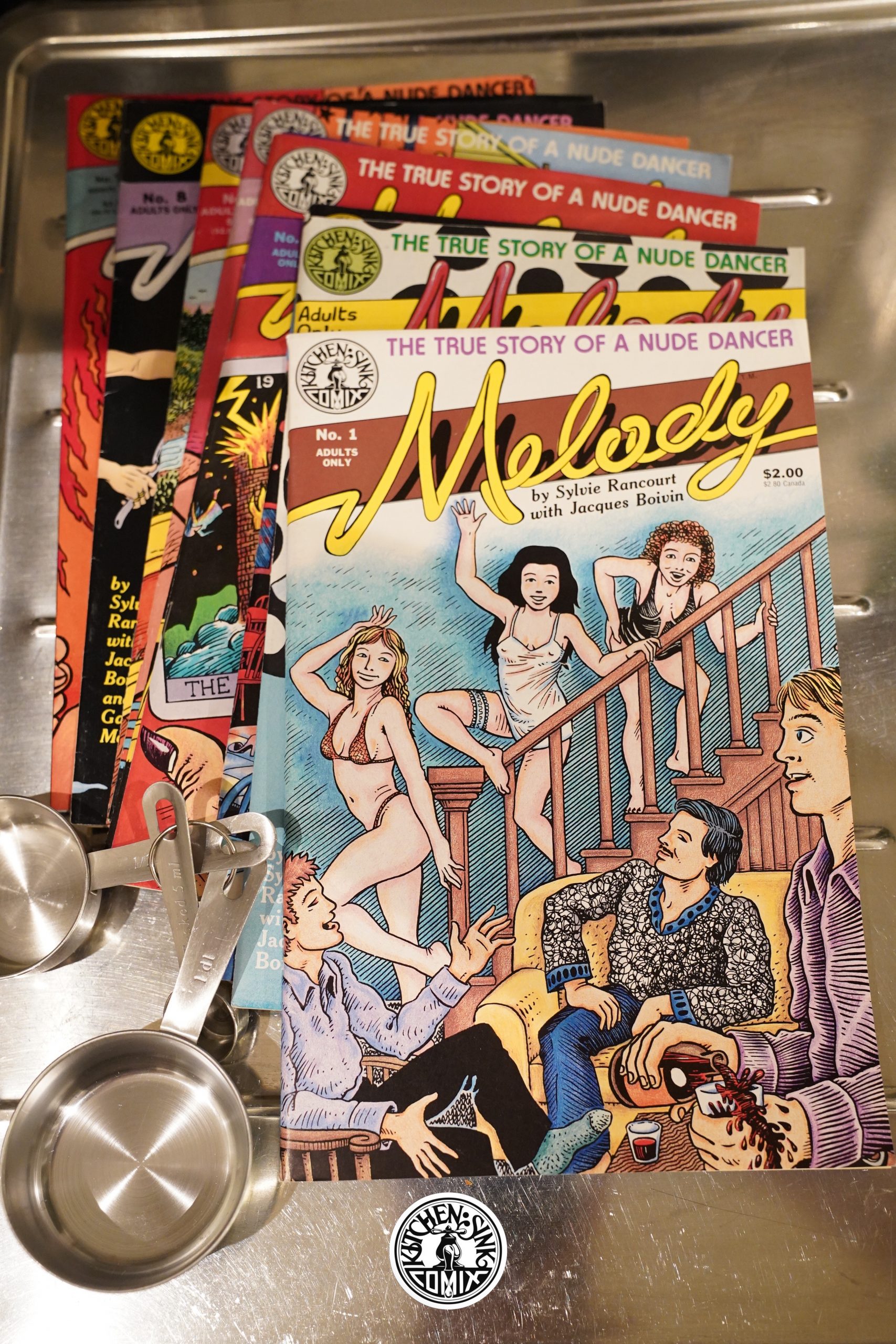

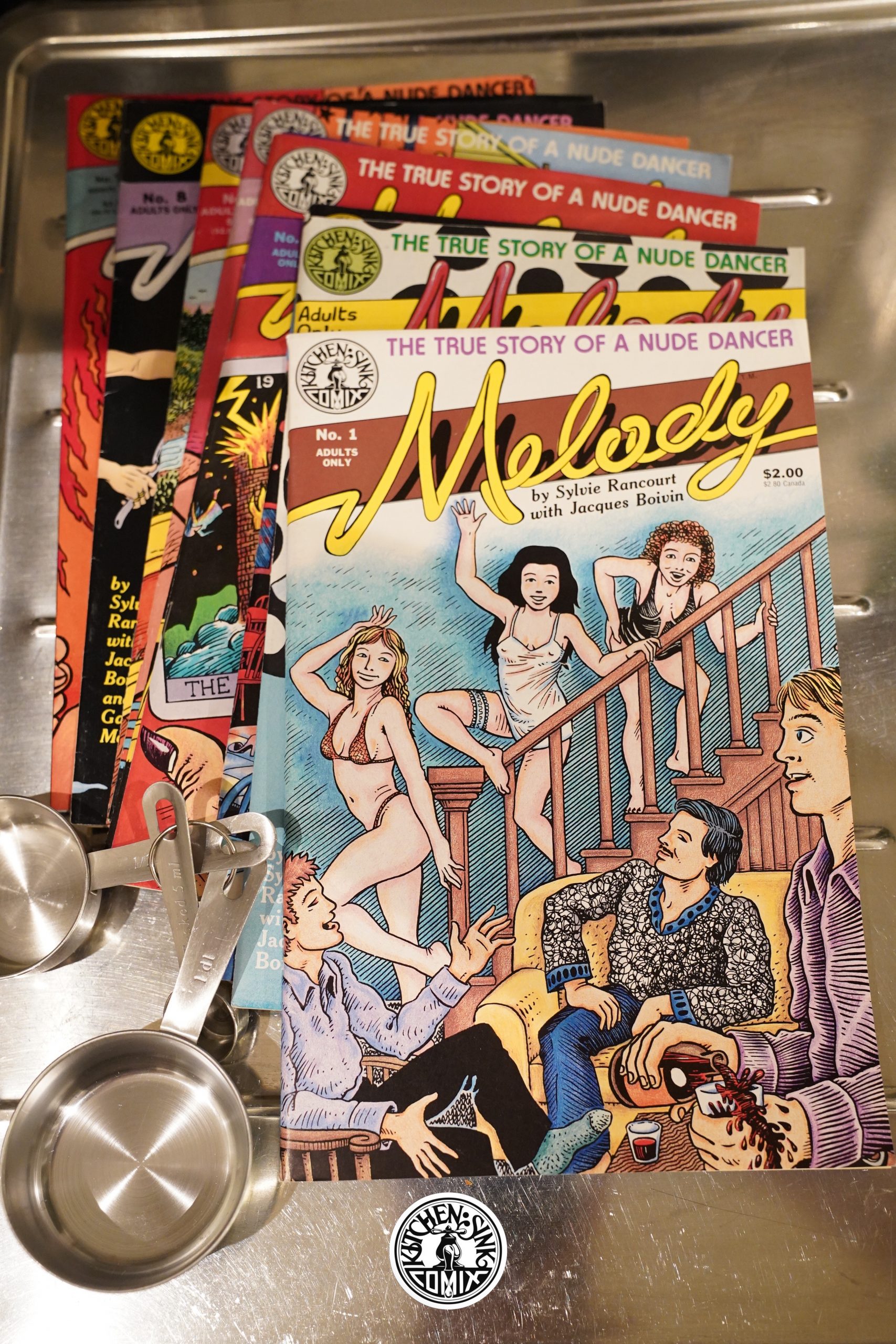

Melody (1988) #1-10 by Sylvie Rancourt, Jacques Boivin and Gabriel Morrissette

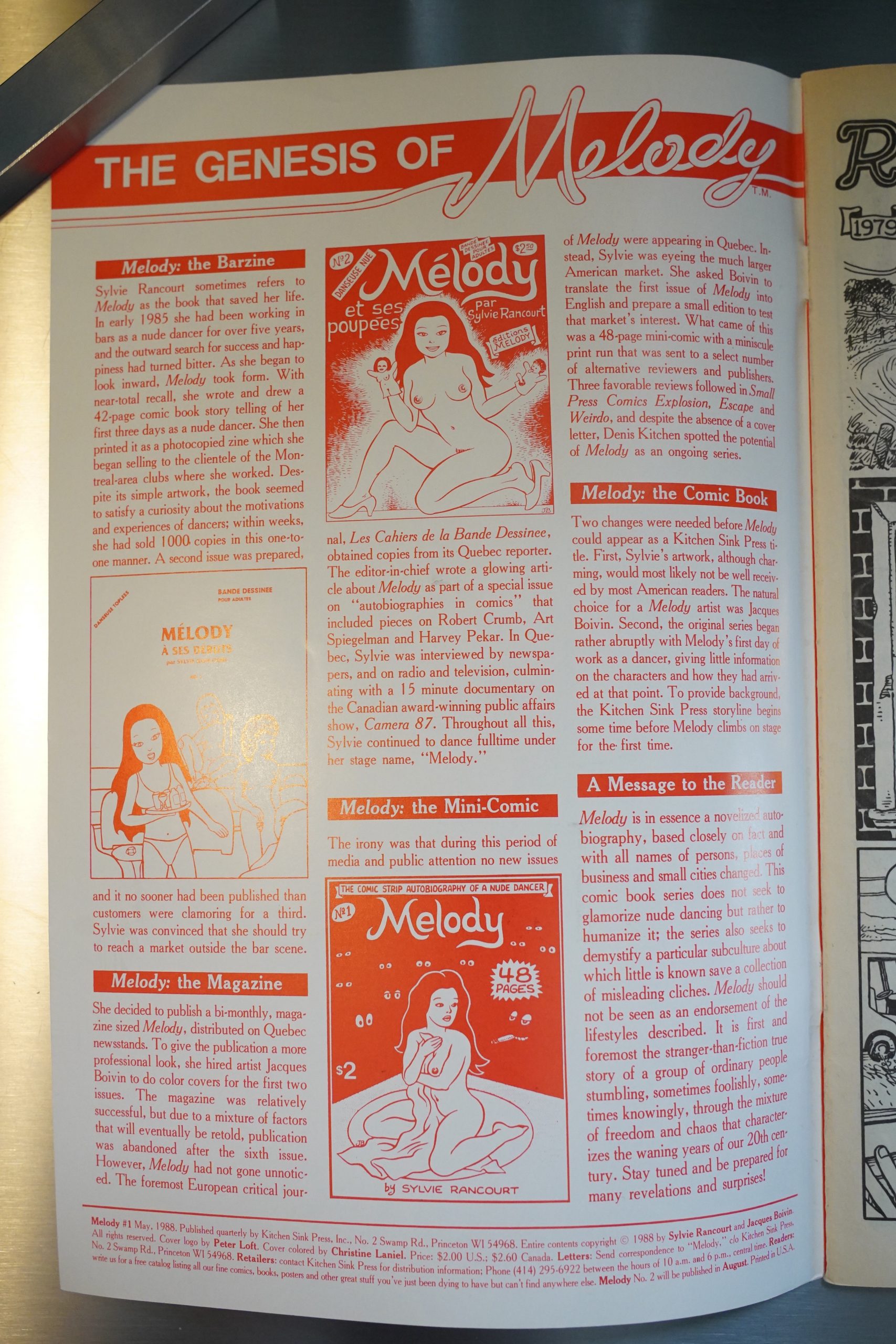

I vaguely remember this book being slightly controversial — Rancourt had published a number of mini comics on her own, but when Kitchen Sink picked up the project, they didn’t think Rancourt’s artwork looked professional enough, so they got Boivin to do the artwork.

(This is all from memory; I have no idea whether that’s accurate.)

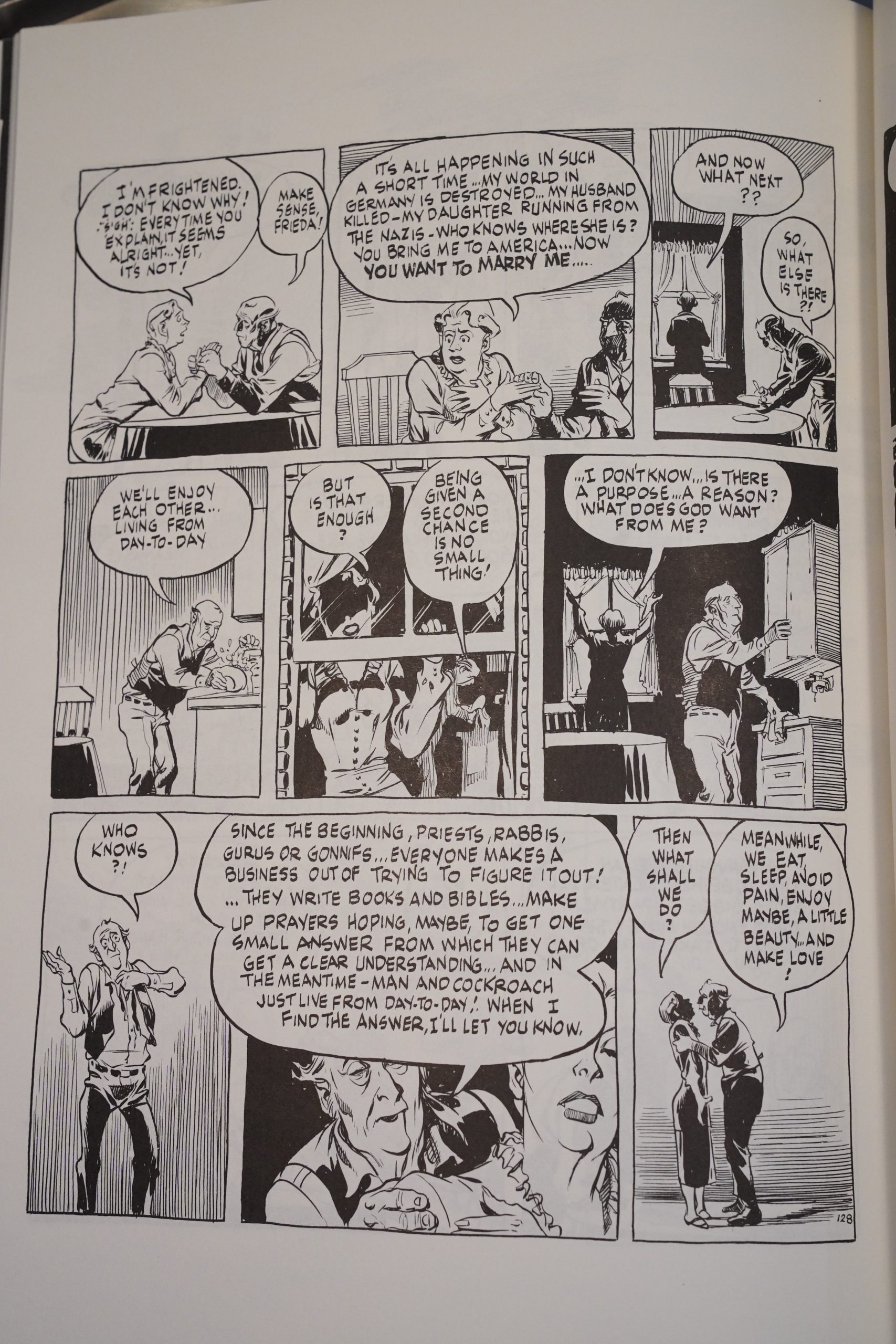

But Drawn & Quarterly published a collection of her original mini-comic a few years back, and it was generally well received. Here’s a sample page:

So, yes, I can understand why Kitchen Sink didn’t think that’d fly in the comics shops, and I can also understand why the Boivin-drawn comic has never been reprinted after 1990 or published to a bookstore market.

One other note before I start reading — Kitchen Sink would only start publishing a single original series after this that lasted more than ten issues after this, which means there’ll be less reading pr. blog post for me from now one, so perhaps I can keep to a daily schedule…

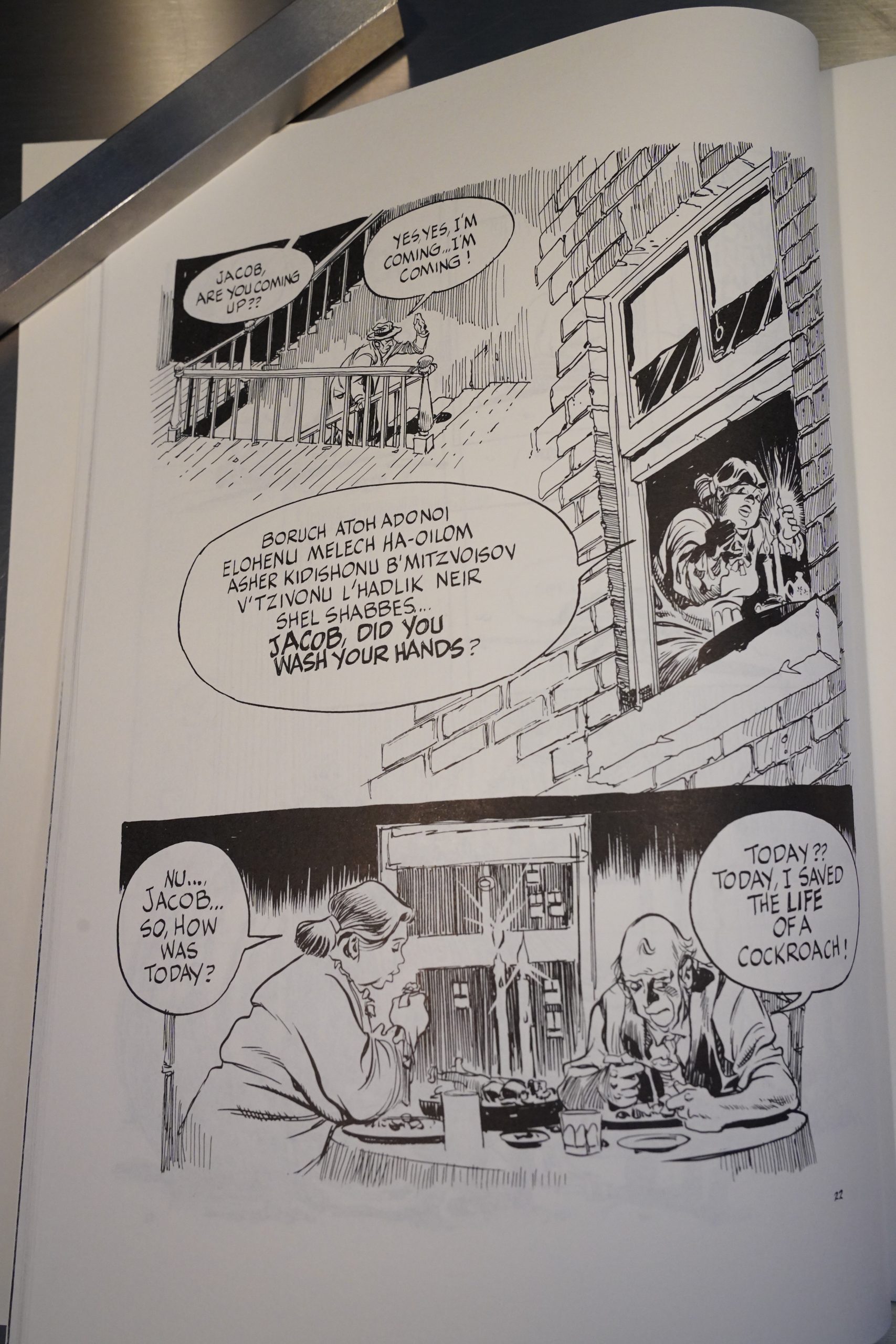

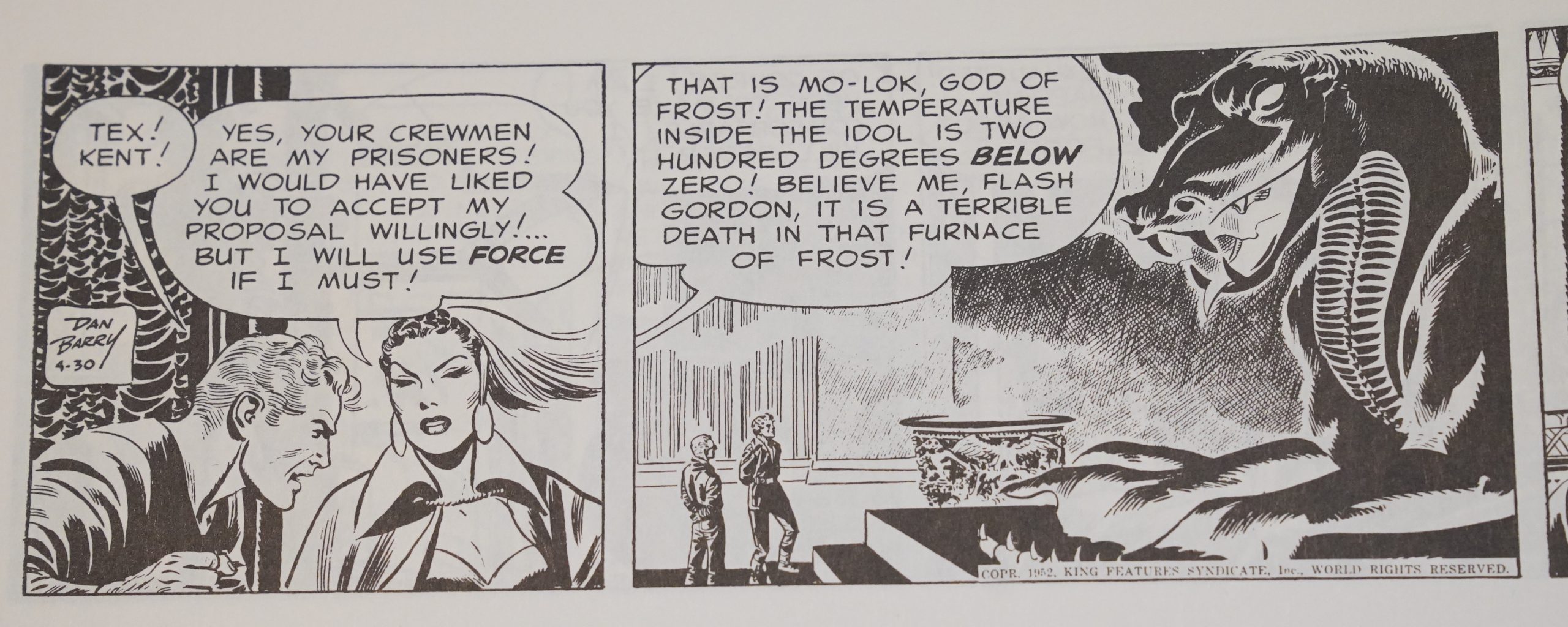

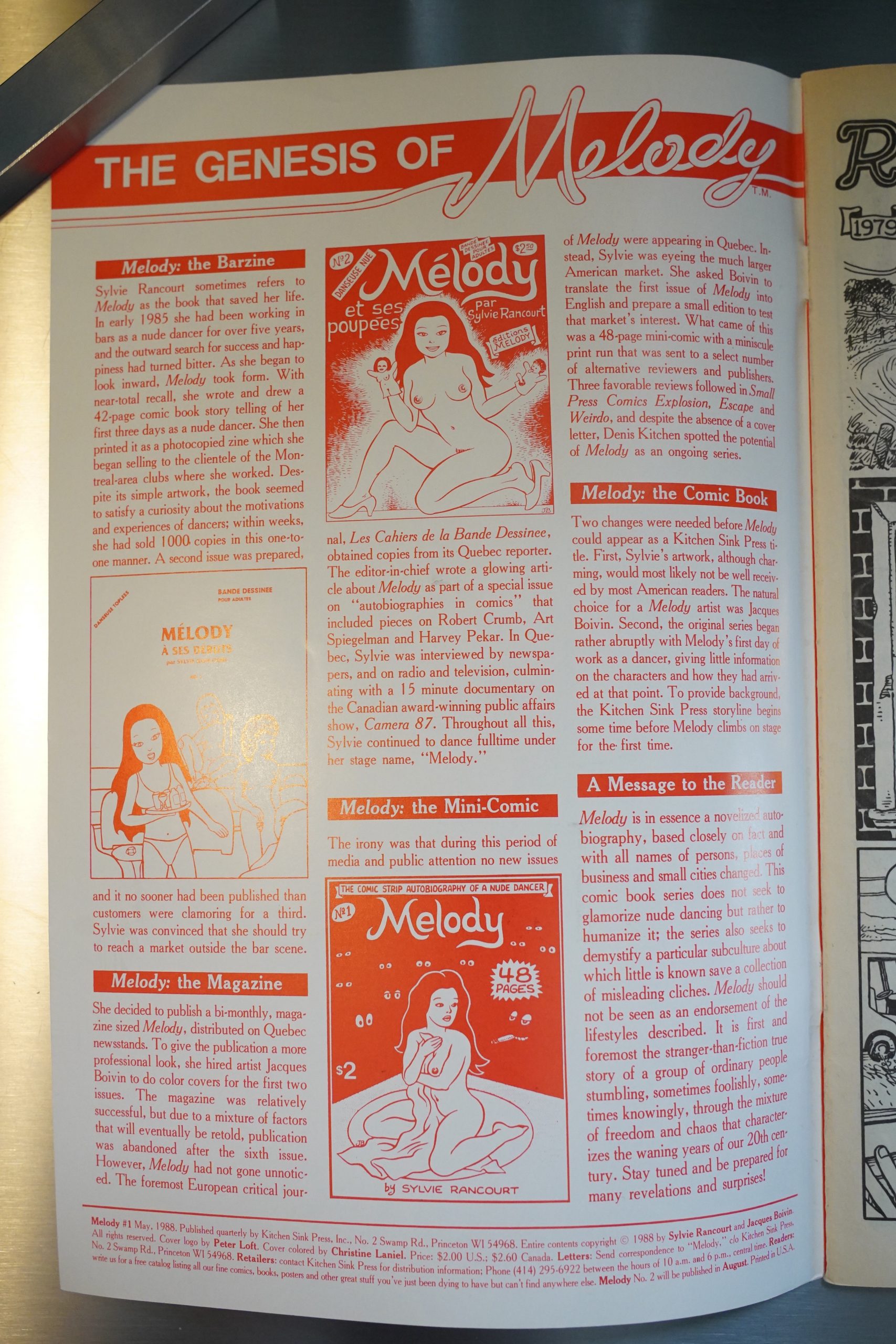

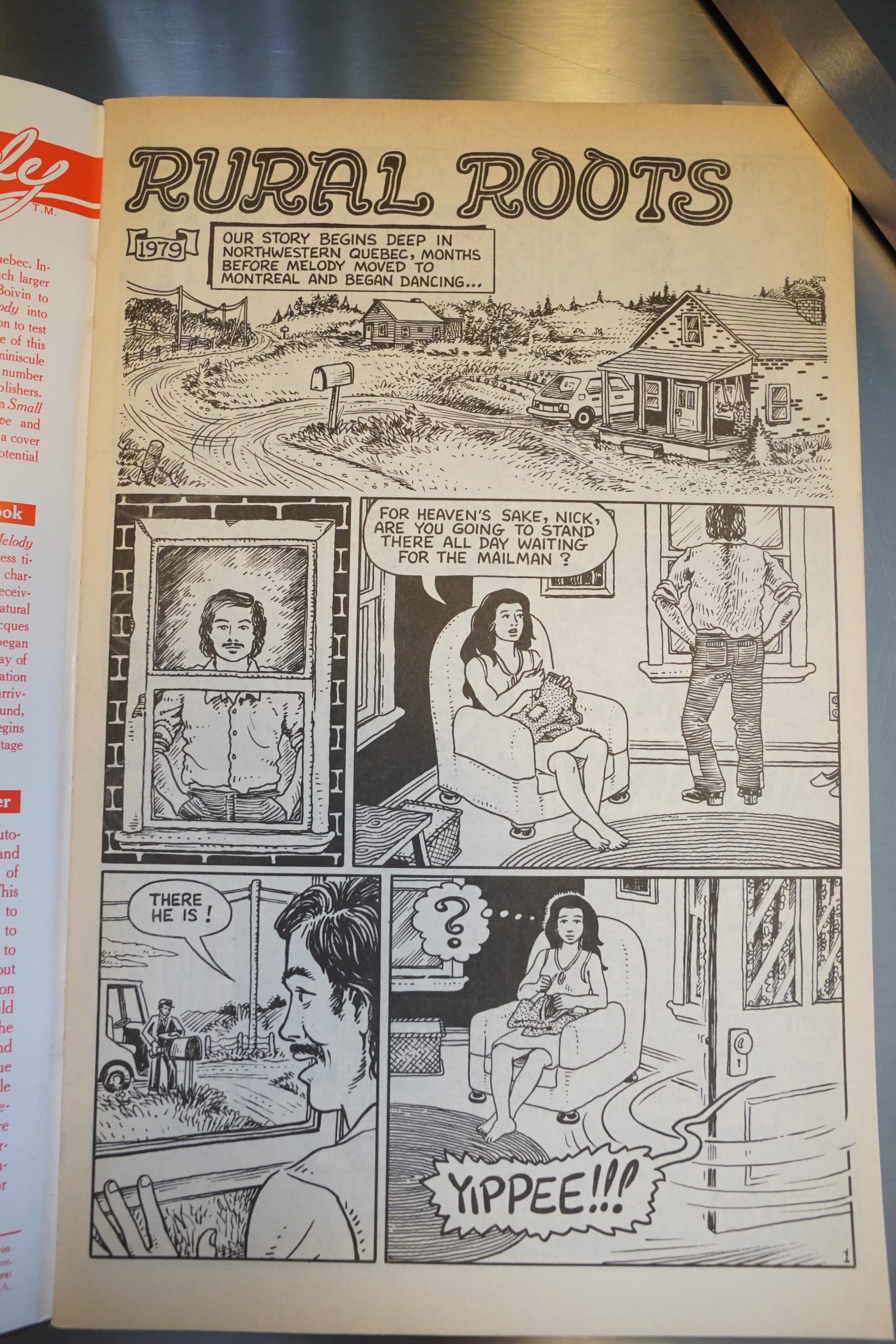

Ah, right — the inside cover on the first issue has the whole publication history. But I’d forgotten that Kitchen had requested that Rancourt give us her “origin story” — comics people are such nerds. Her solo work had just been about working as a nude dancer, but this series is about her life before she started dancing.

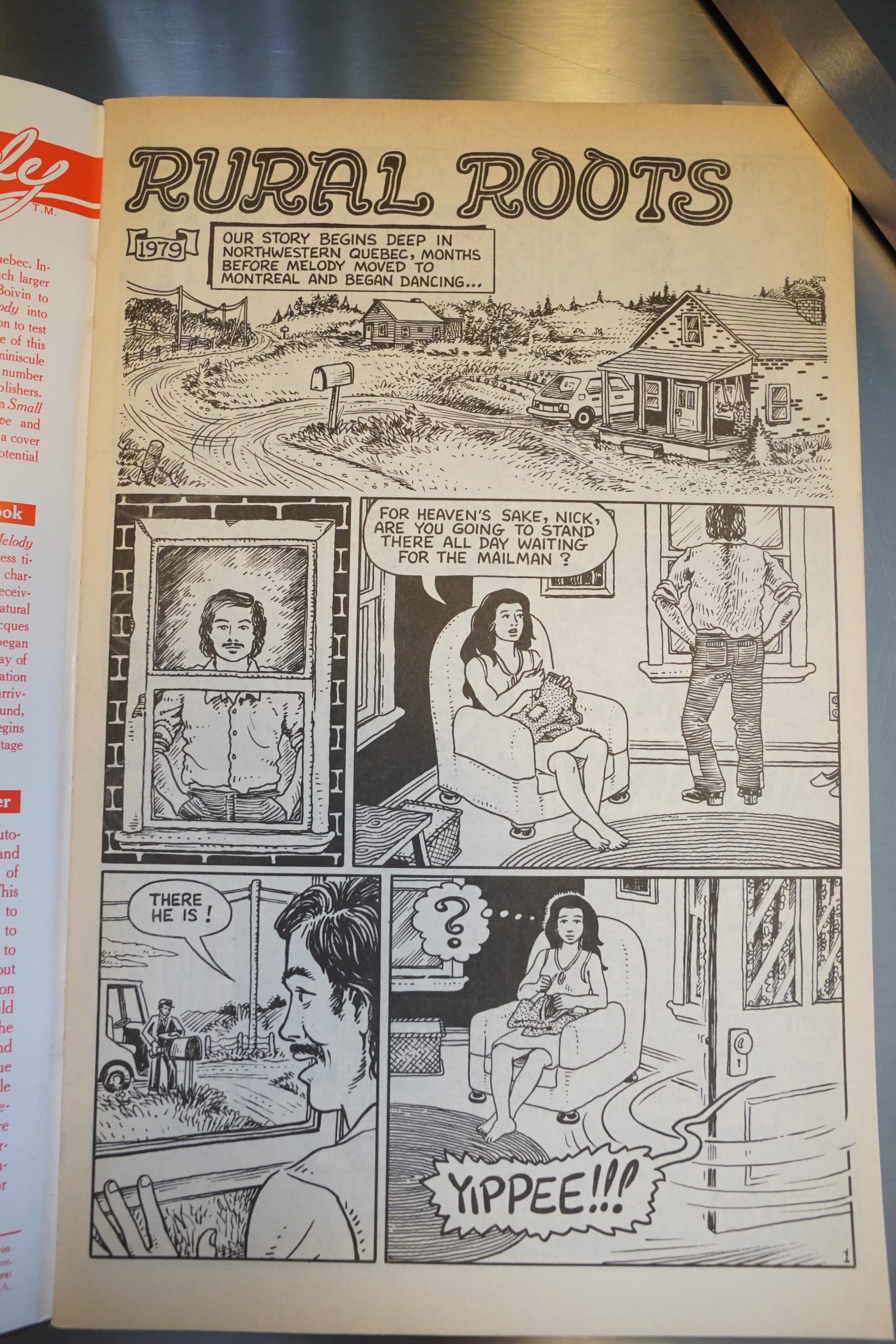

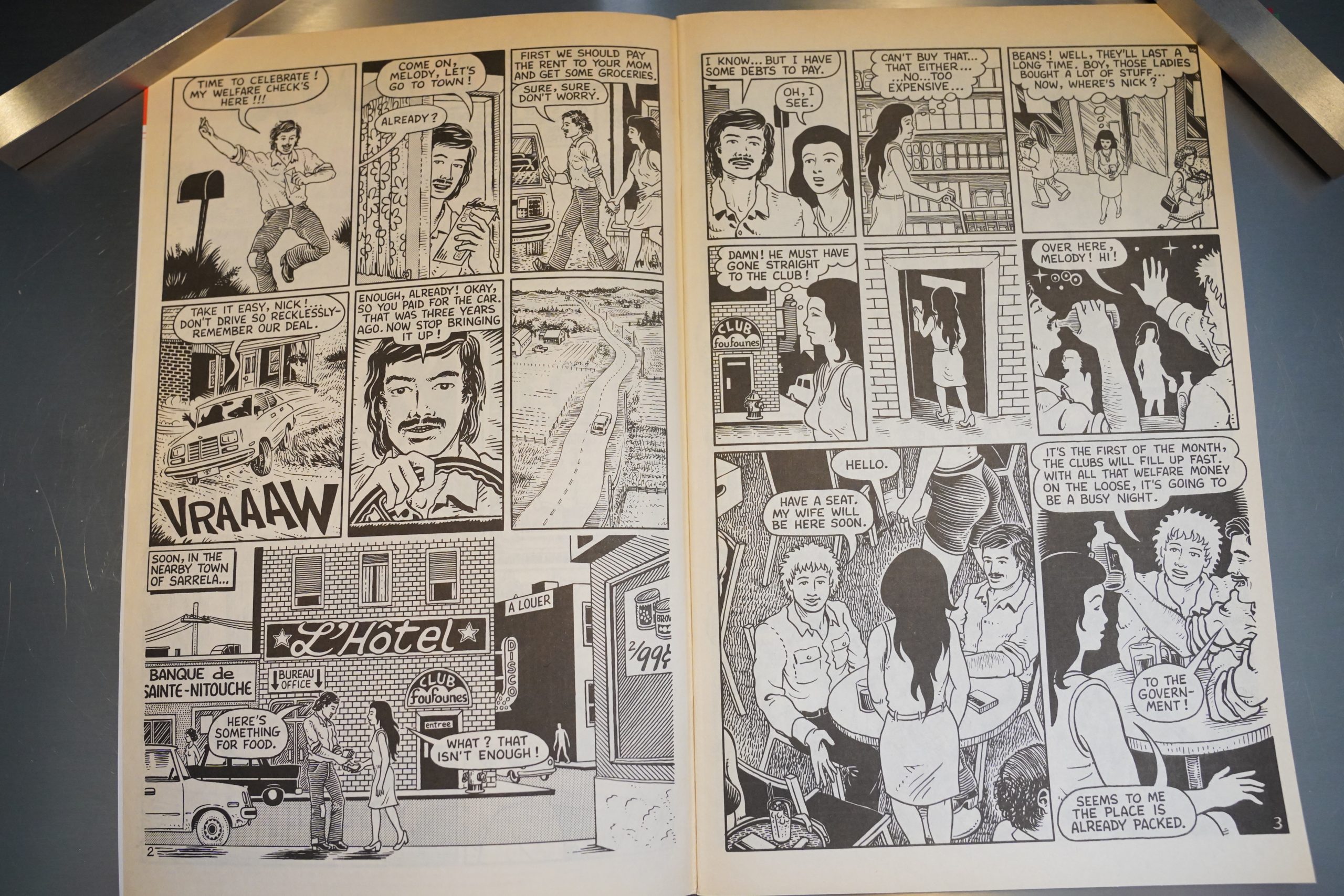

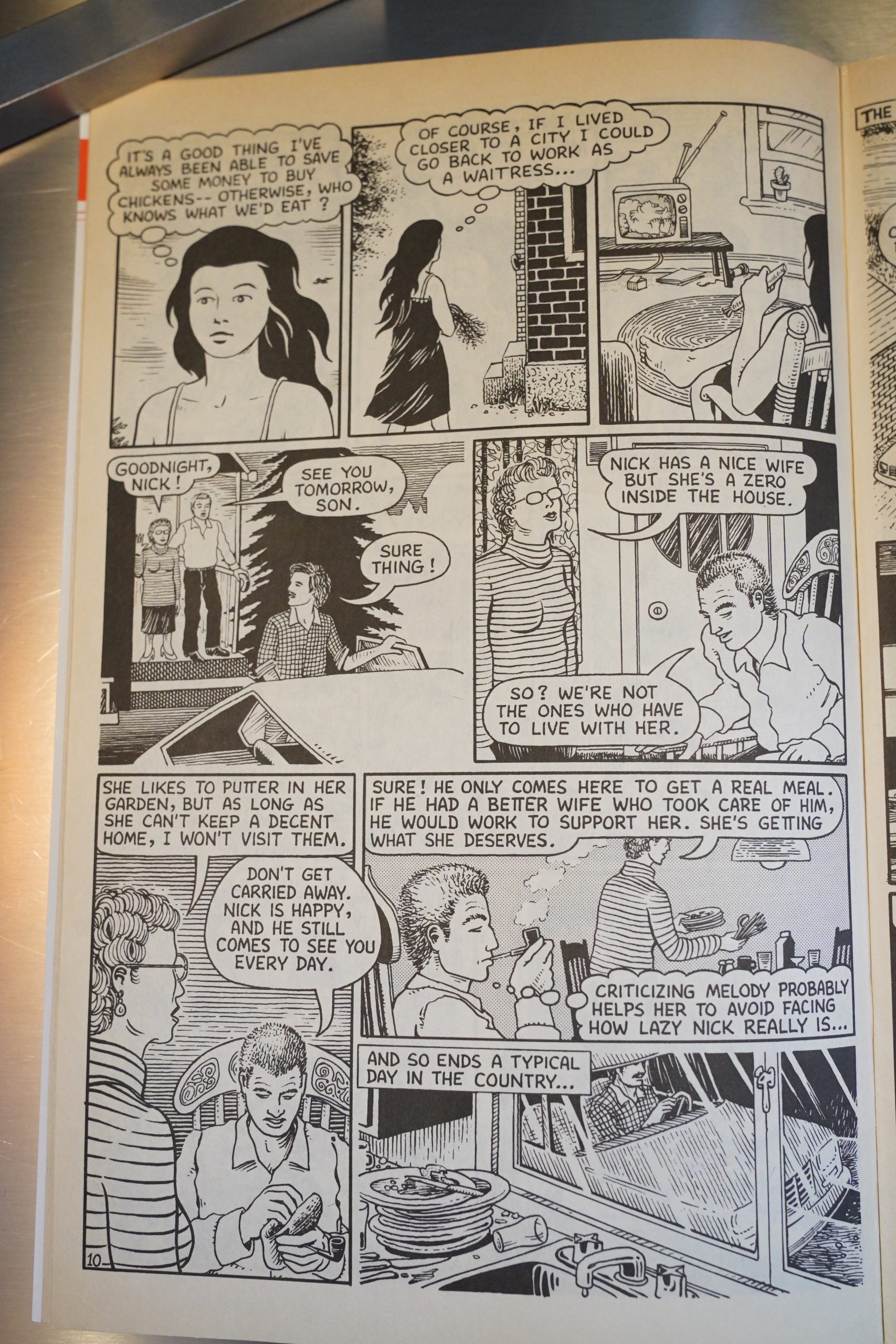

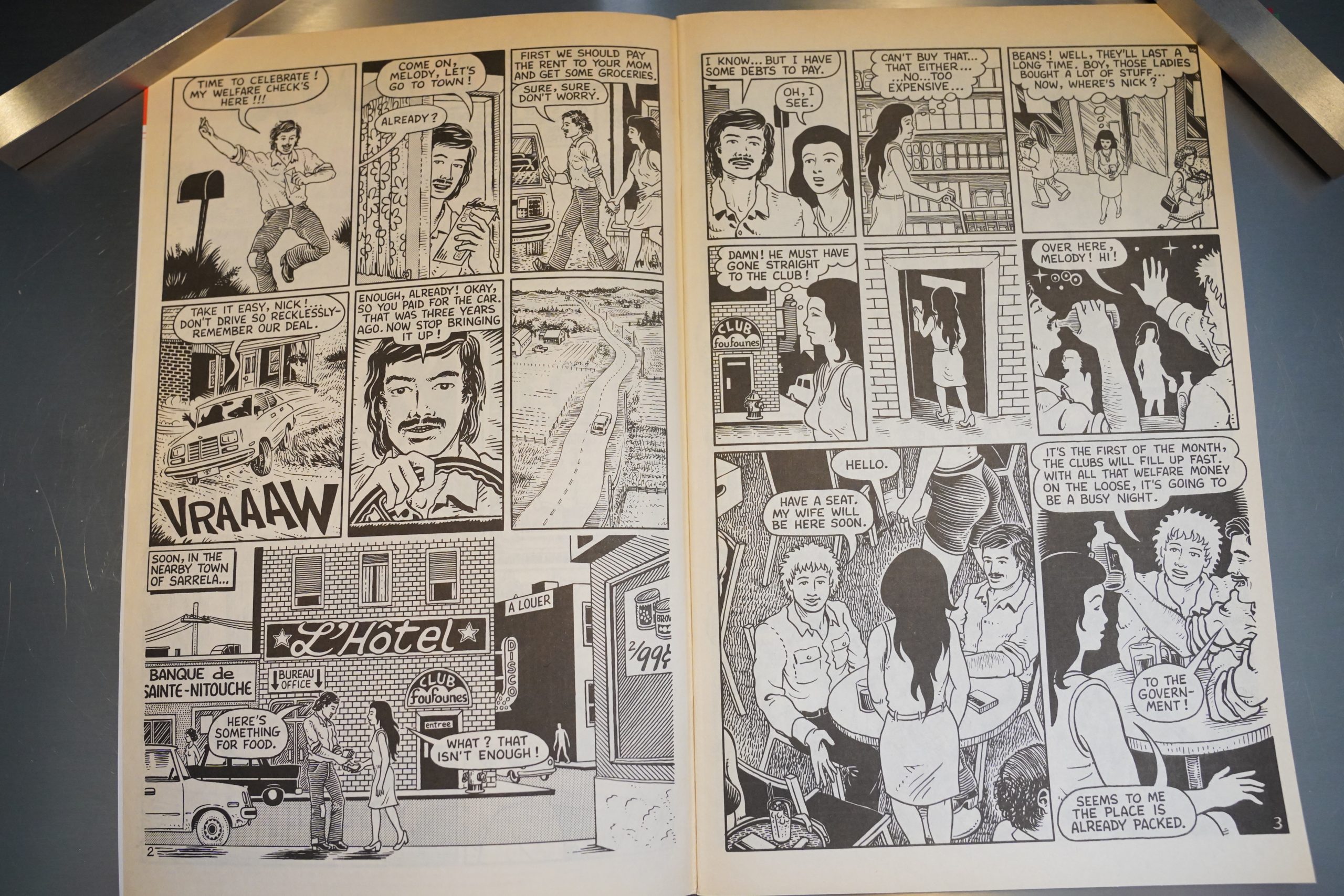

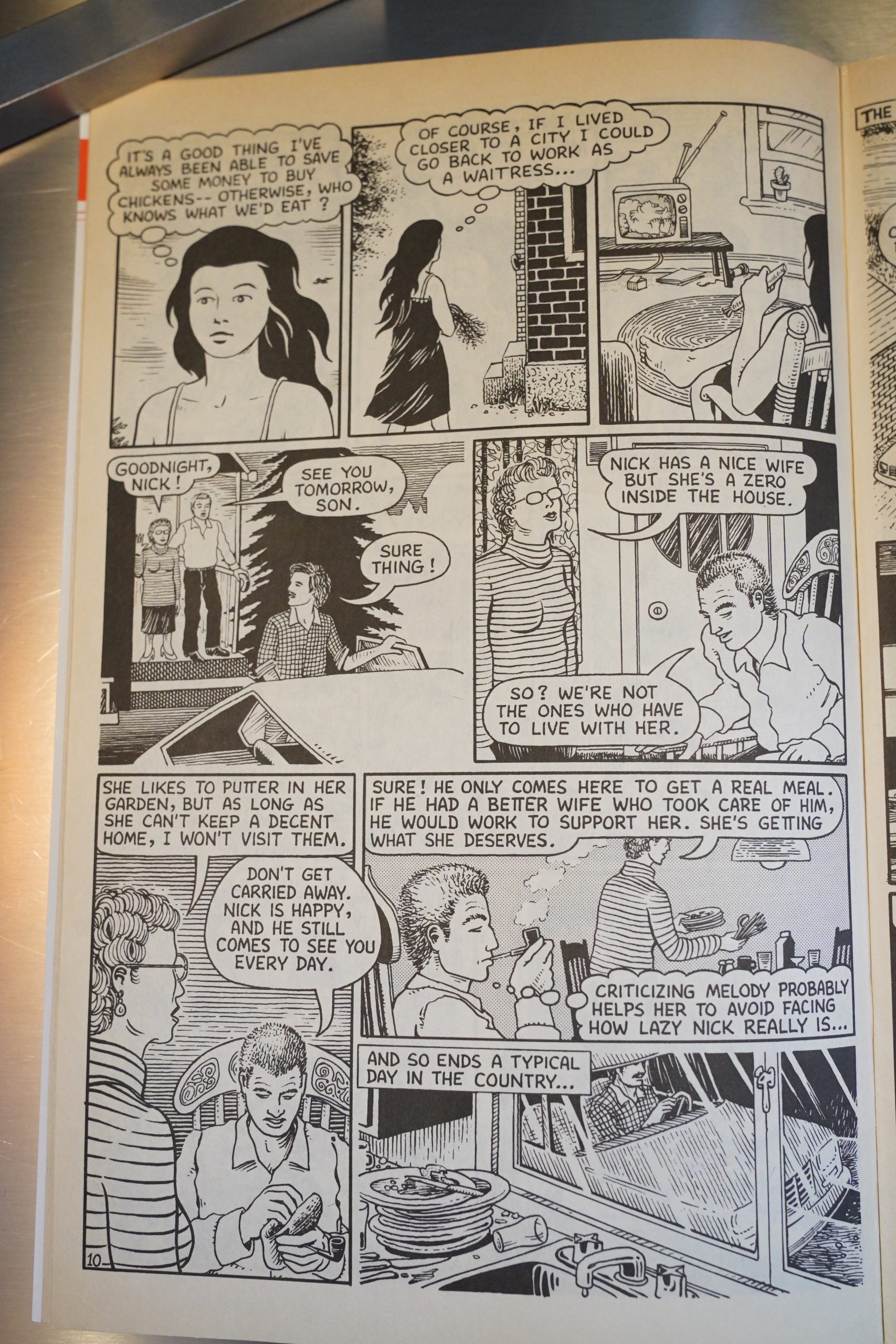

So we’re in rural Abitibi, which (I’m guessing from this book) is pretty rural, but a very poor part of Ontario? Or perhaps it’s just the people Melody’s hanging out with, and especially her slacker husband, who’s pretty hopeless when he comes to money.

His routine is getting his welfare check, and then spending it all in one day at the local strip club. (He eats at his parent’s house, but Melody doesn’t go there, because they don’t really like her.)

I know, I’m recapping the plot here 3000% more than I usually do, but it’s just so tempting somehow.

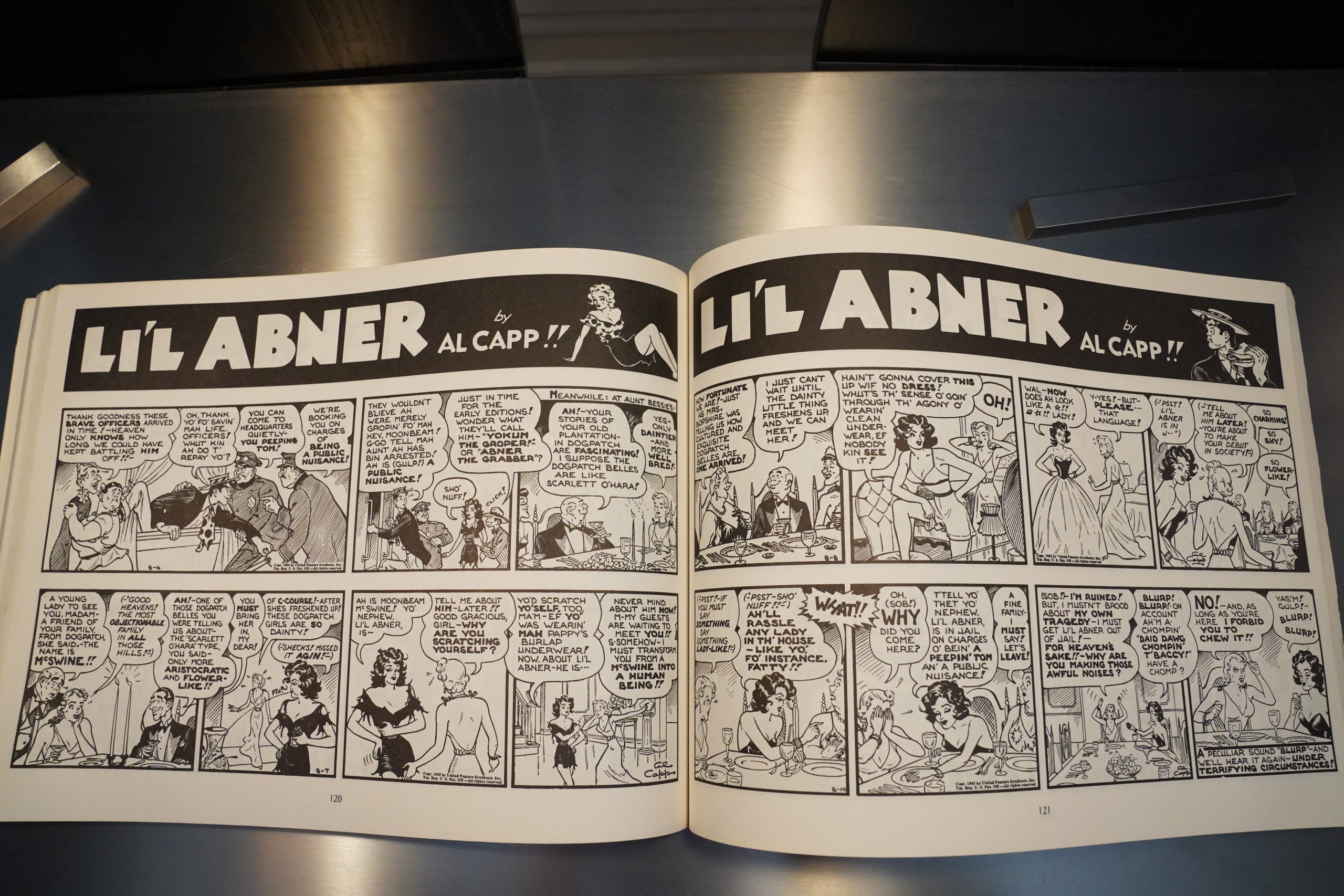

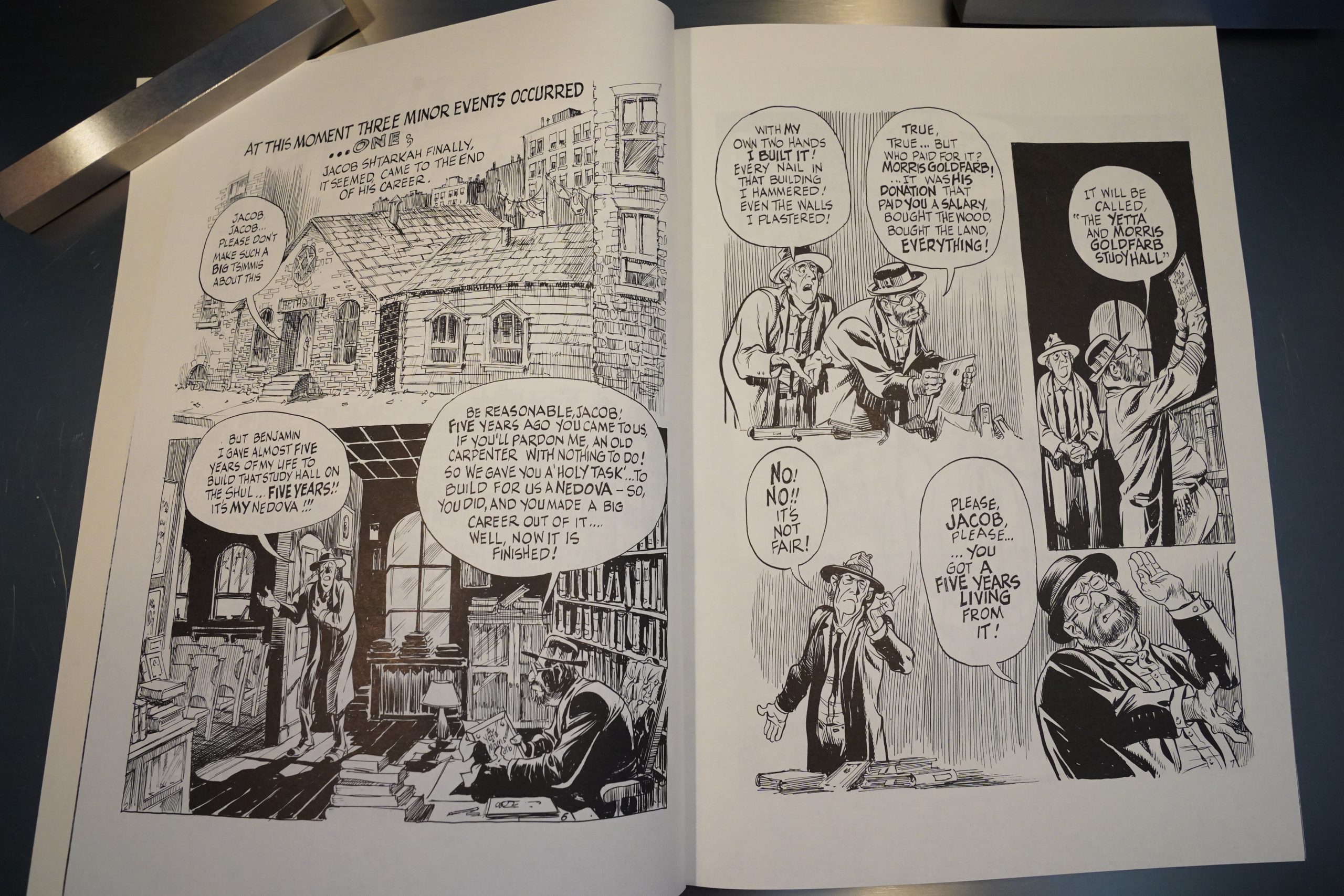

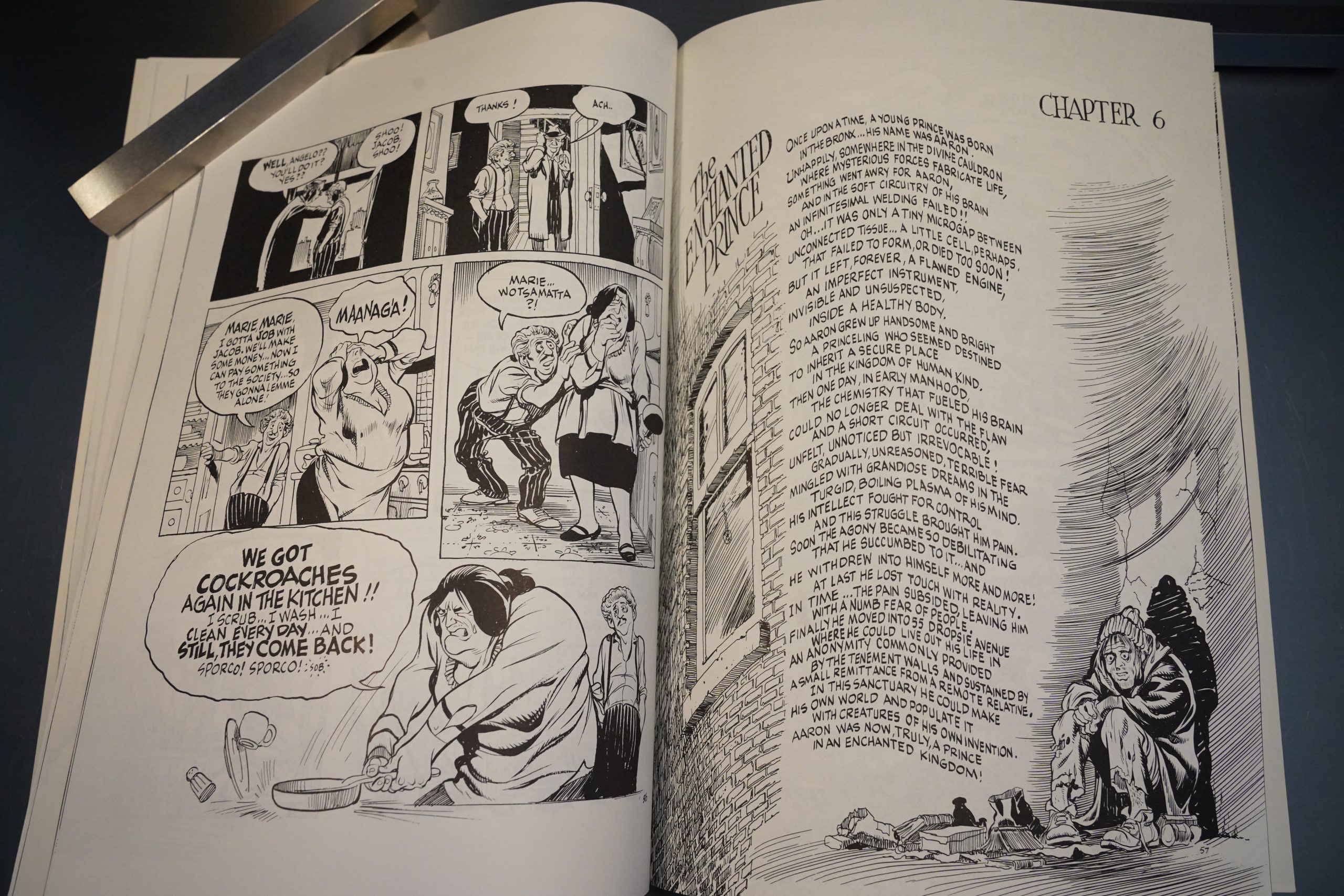

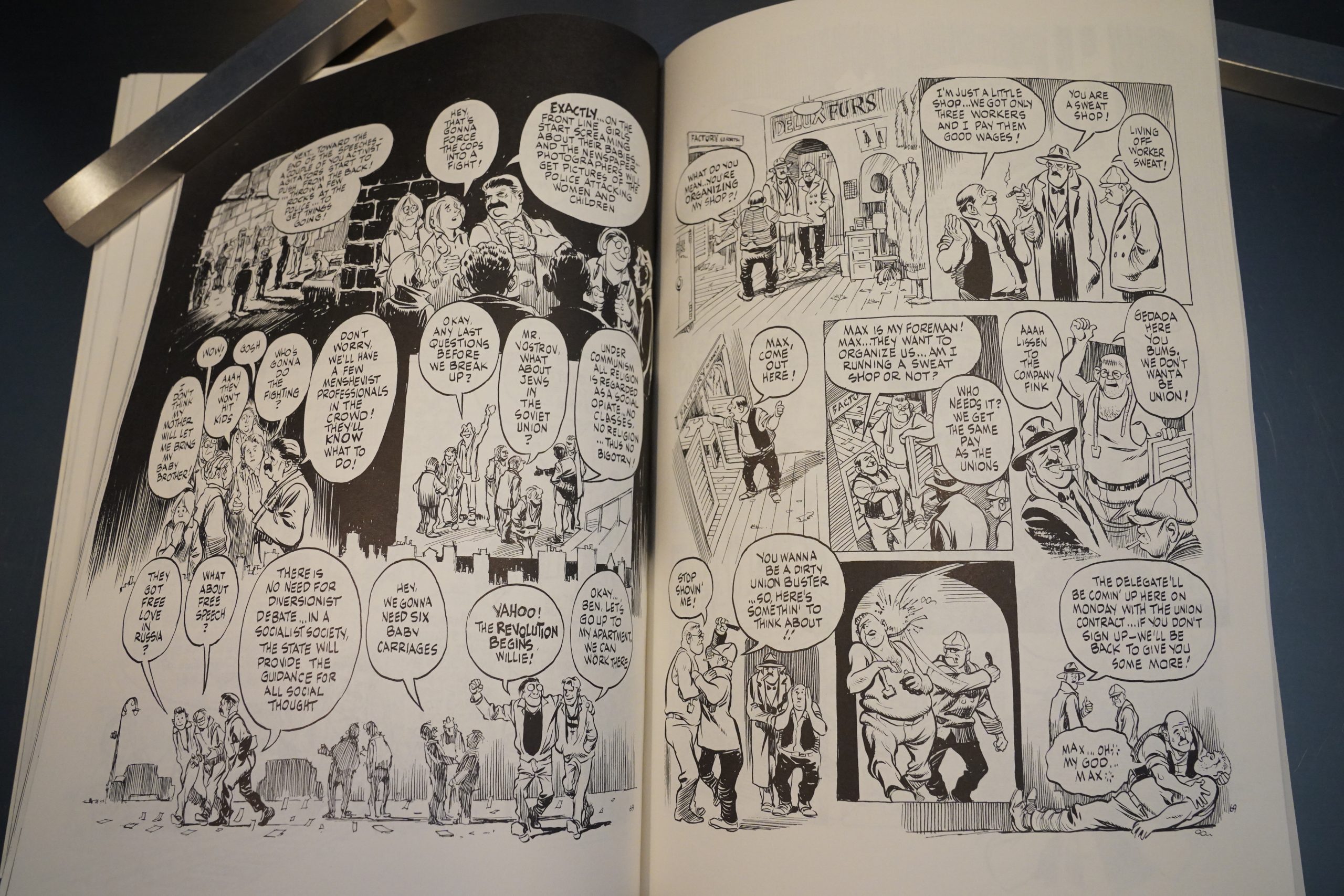

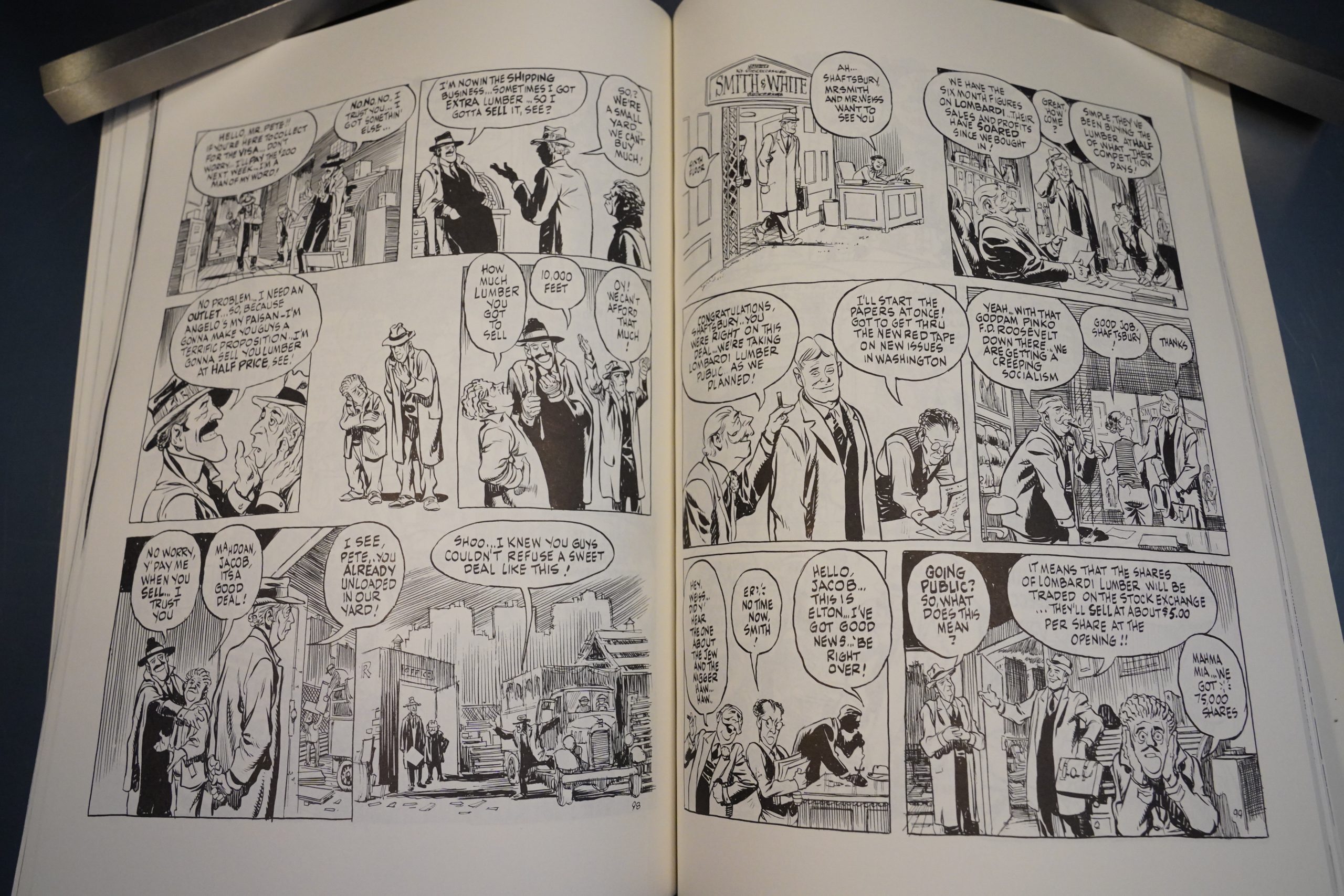

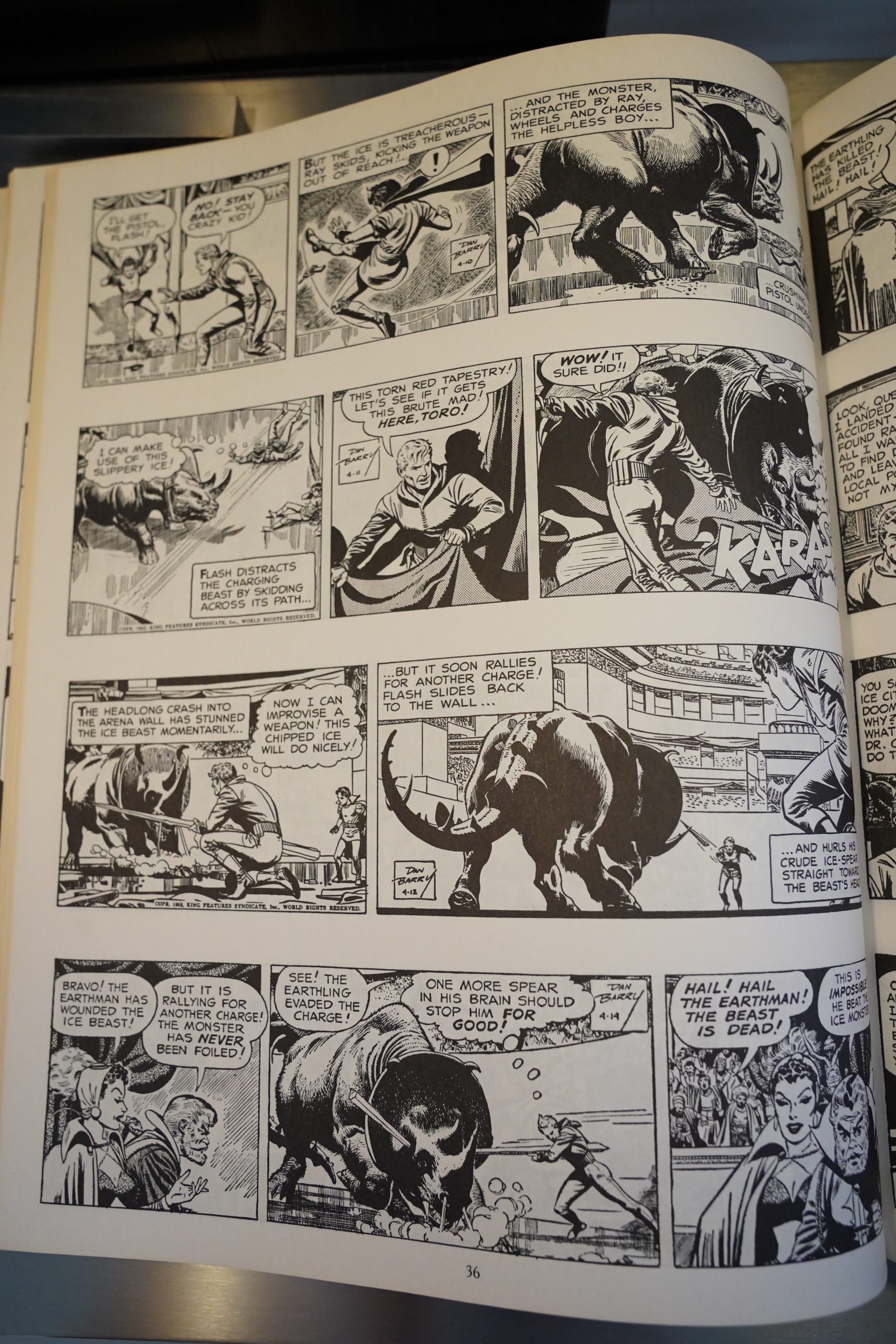

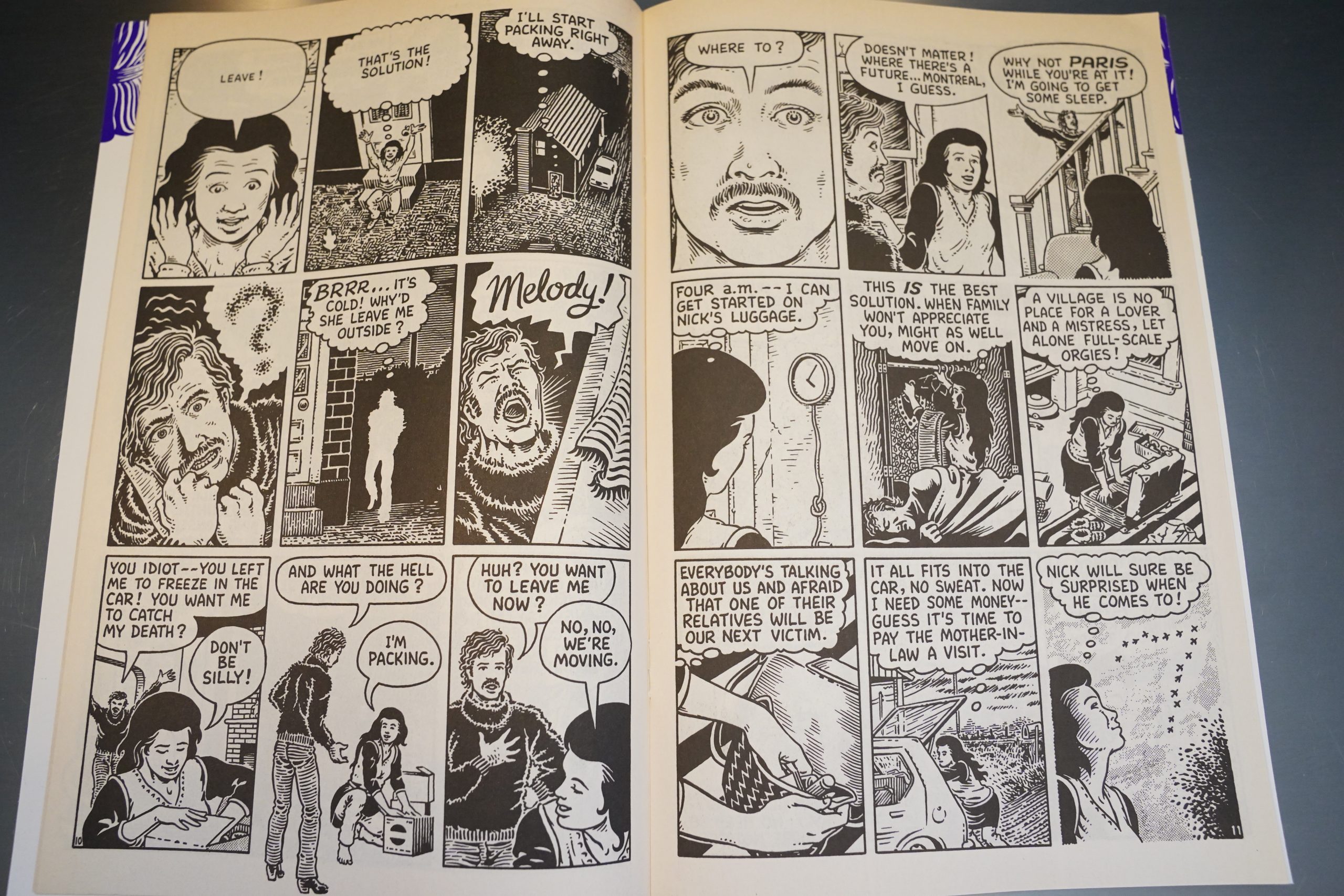

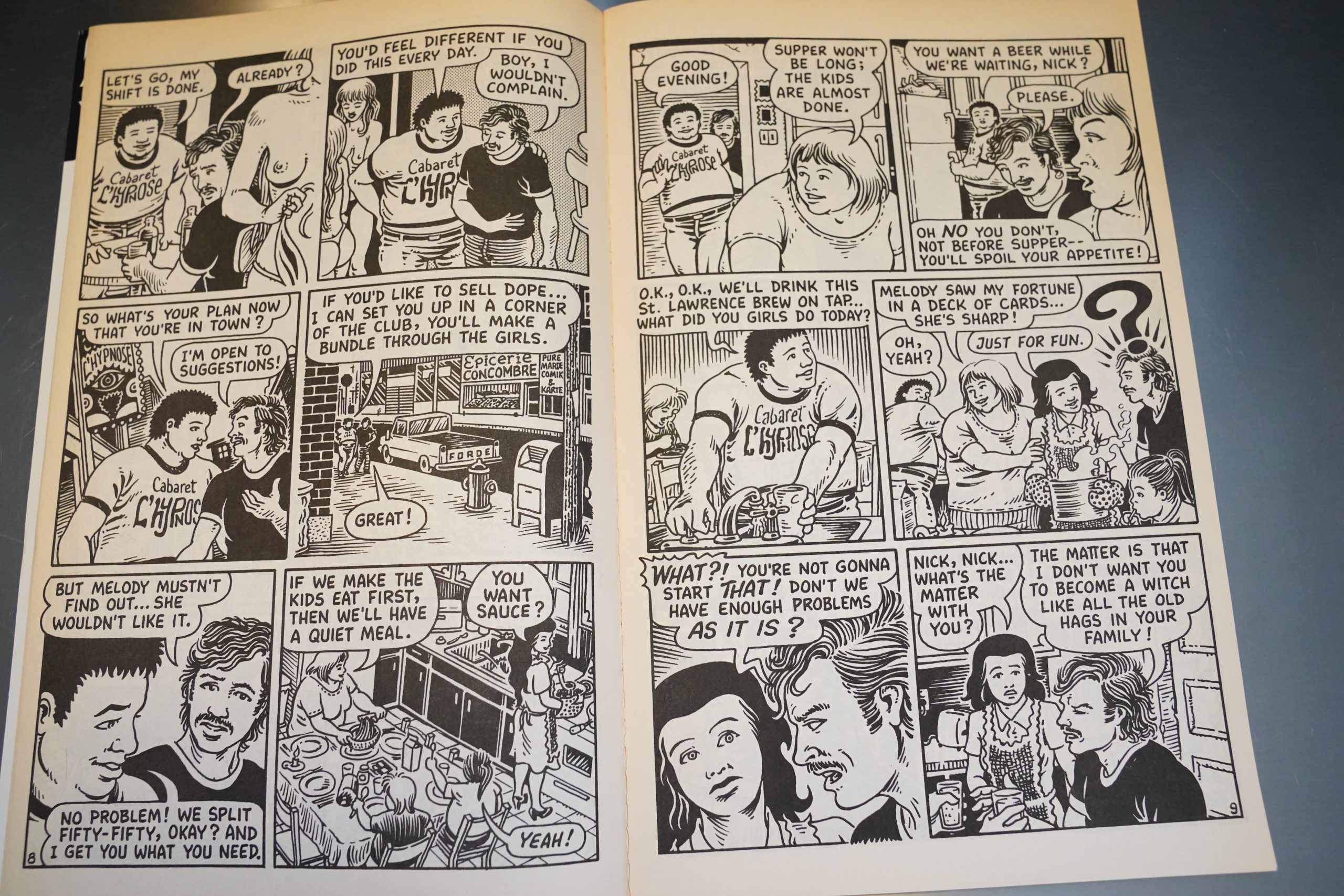

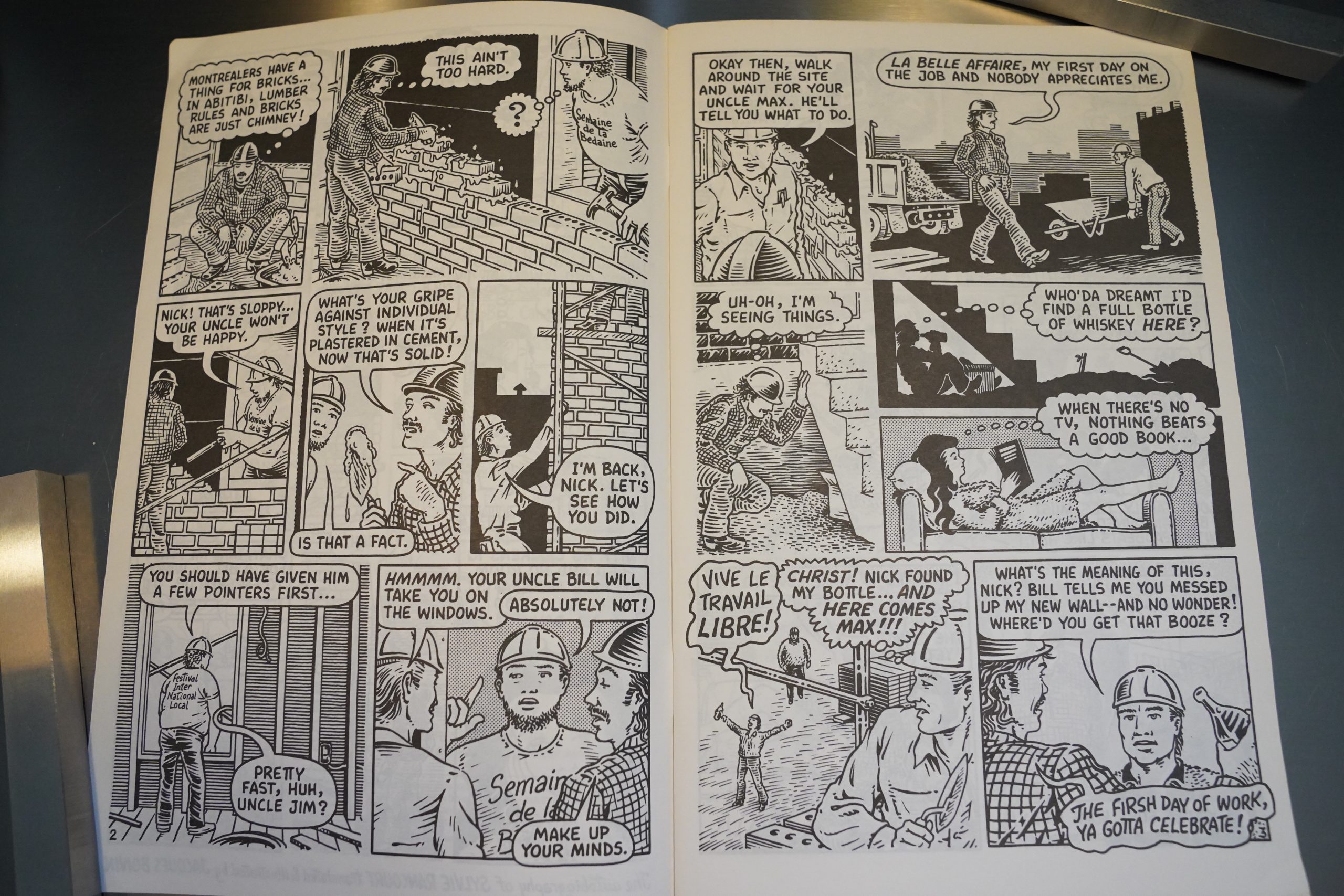

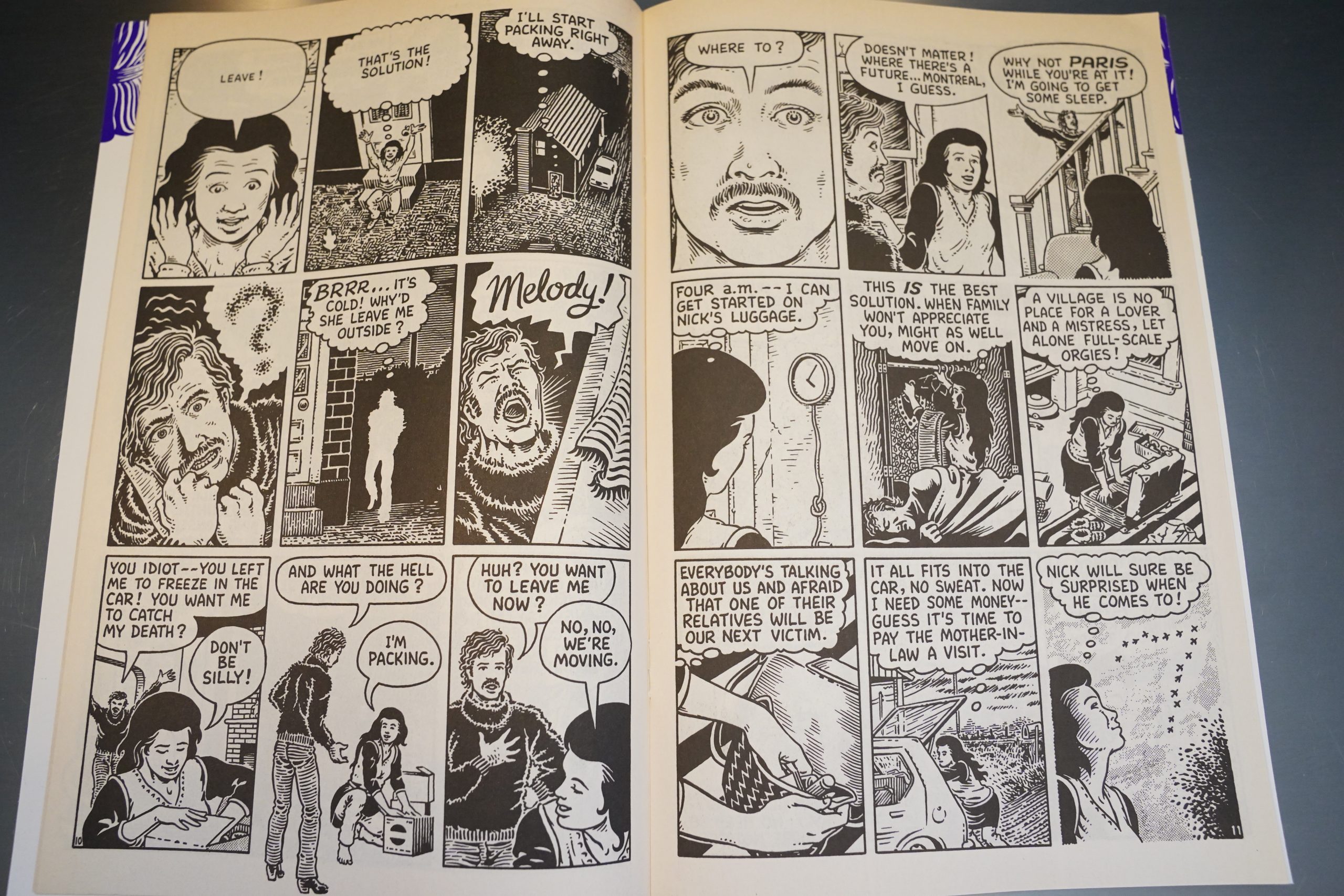

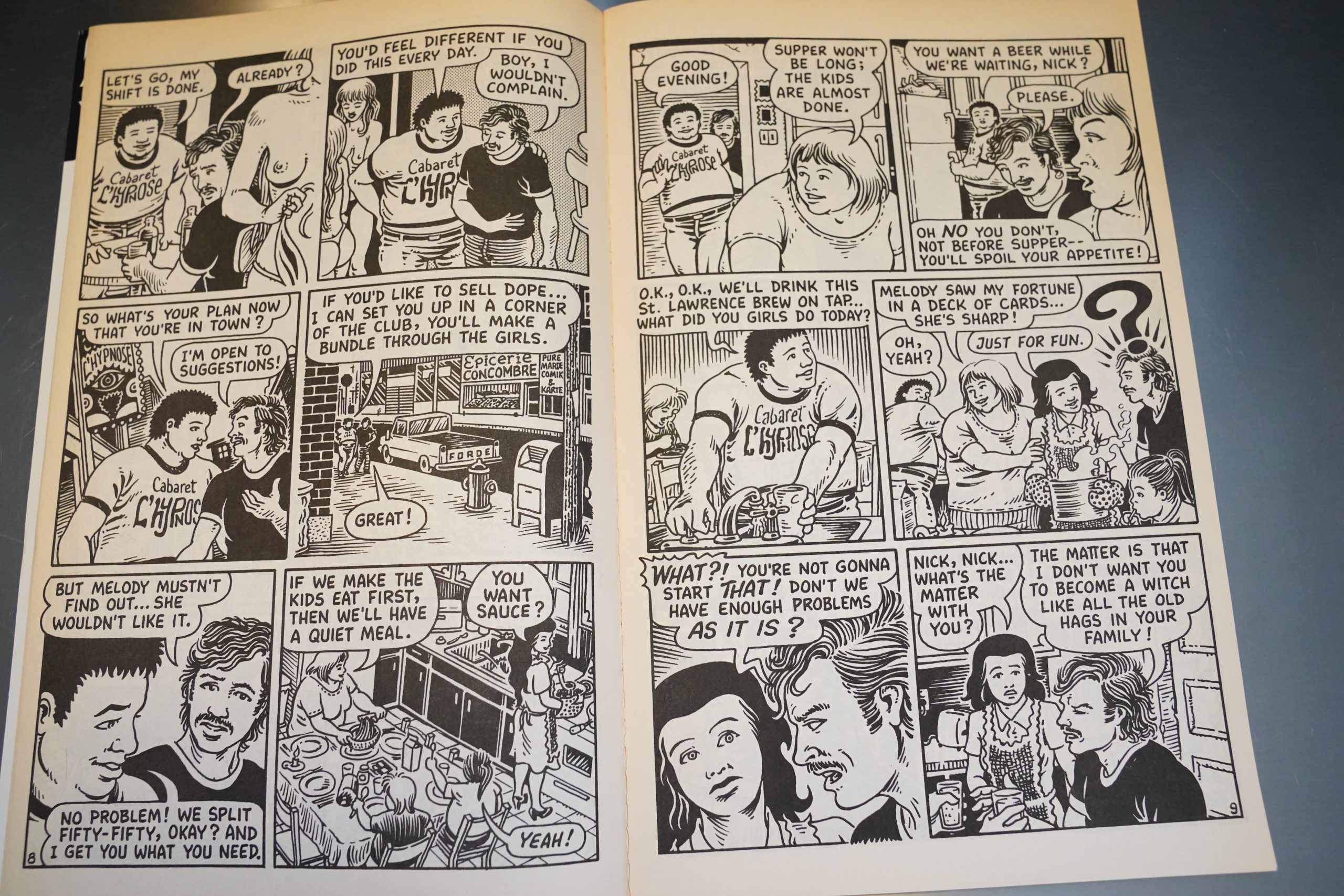

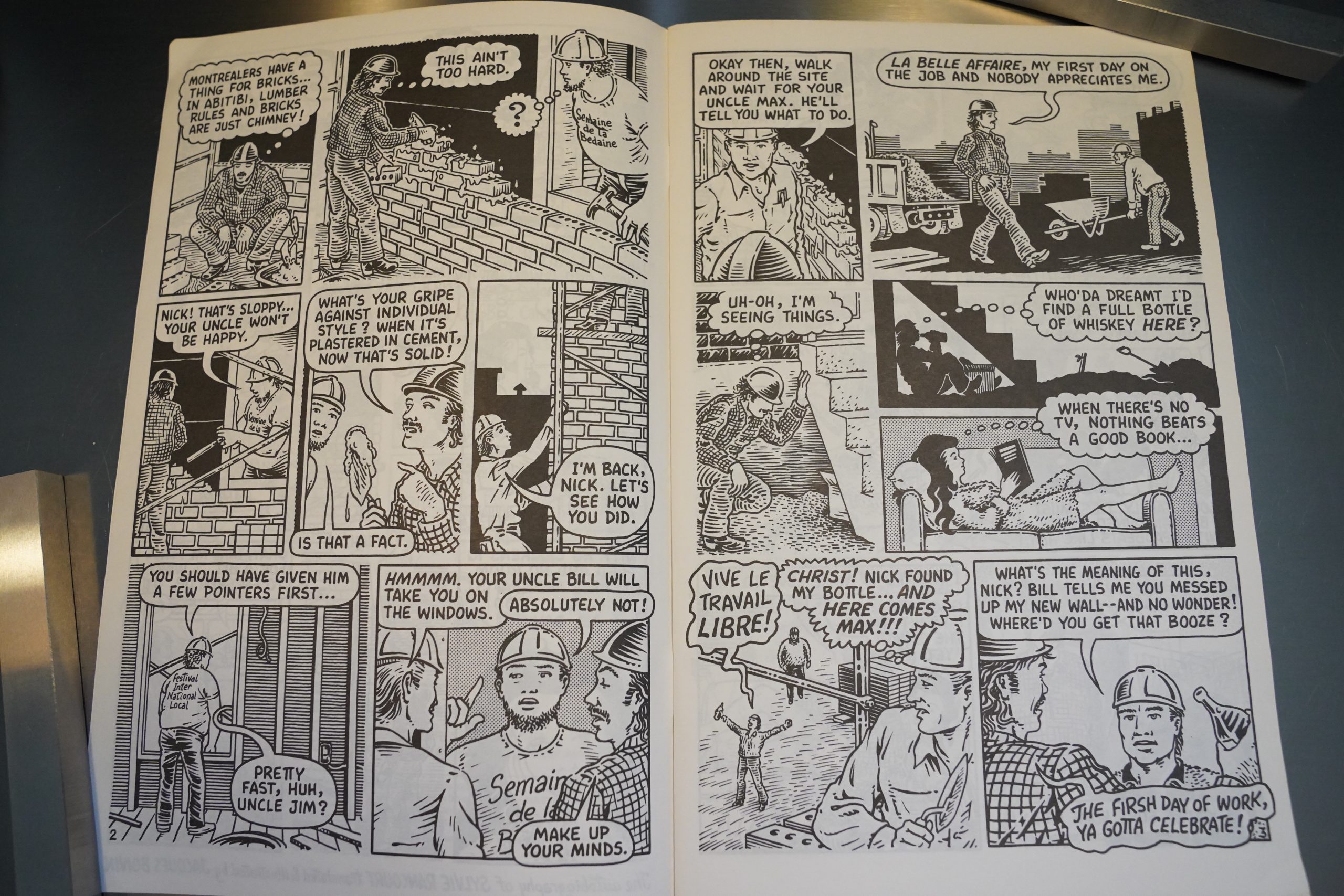

Anyway, Boivin’s artwork is fine — but it’s in a style that gone pretty much out of style. It’s very, very straightforward, with nary any inventive blush.

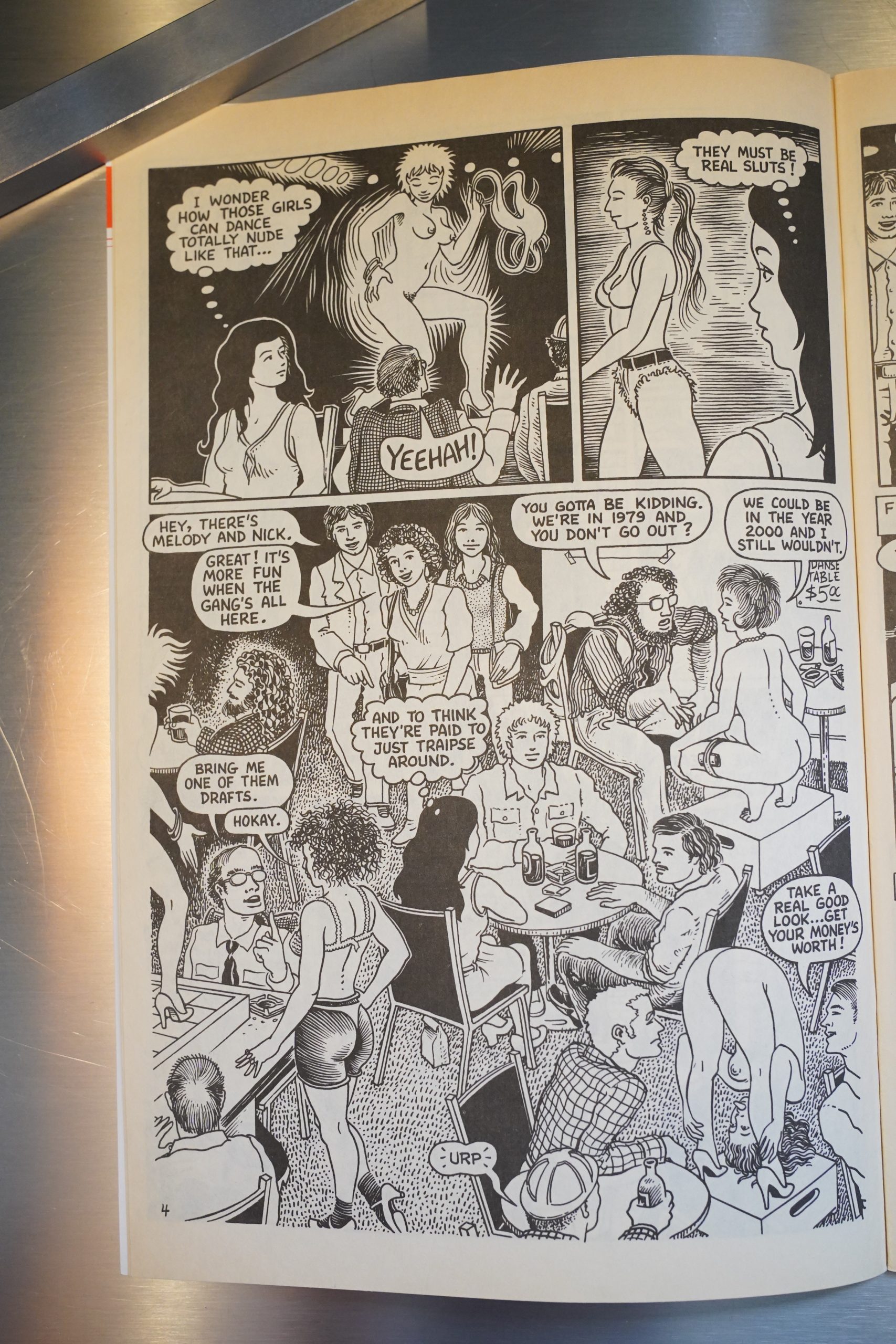

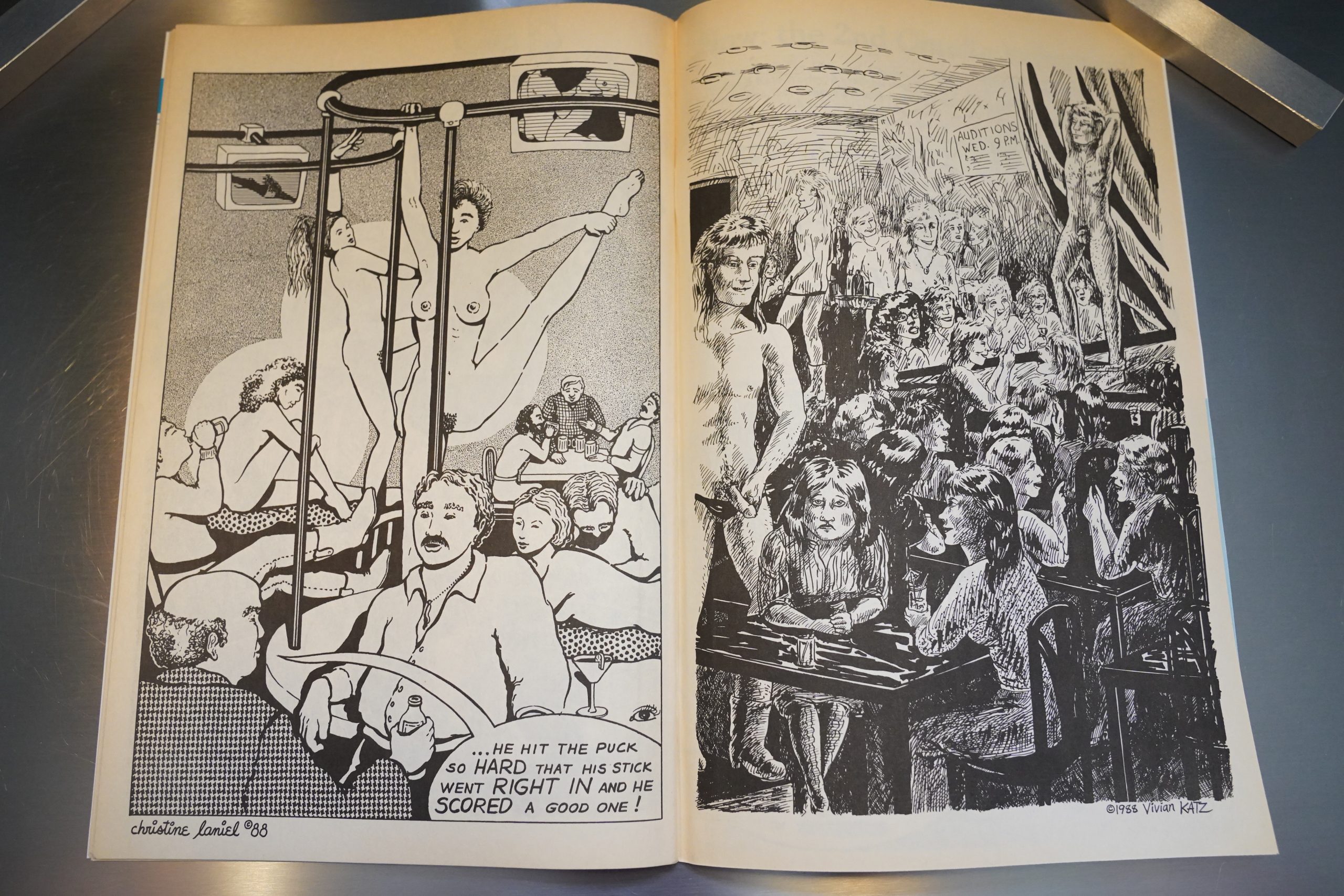

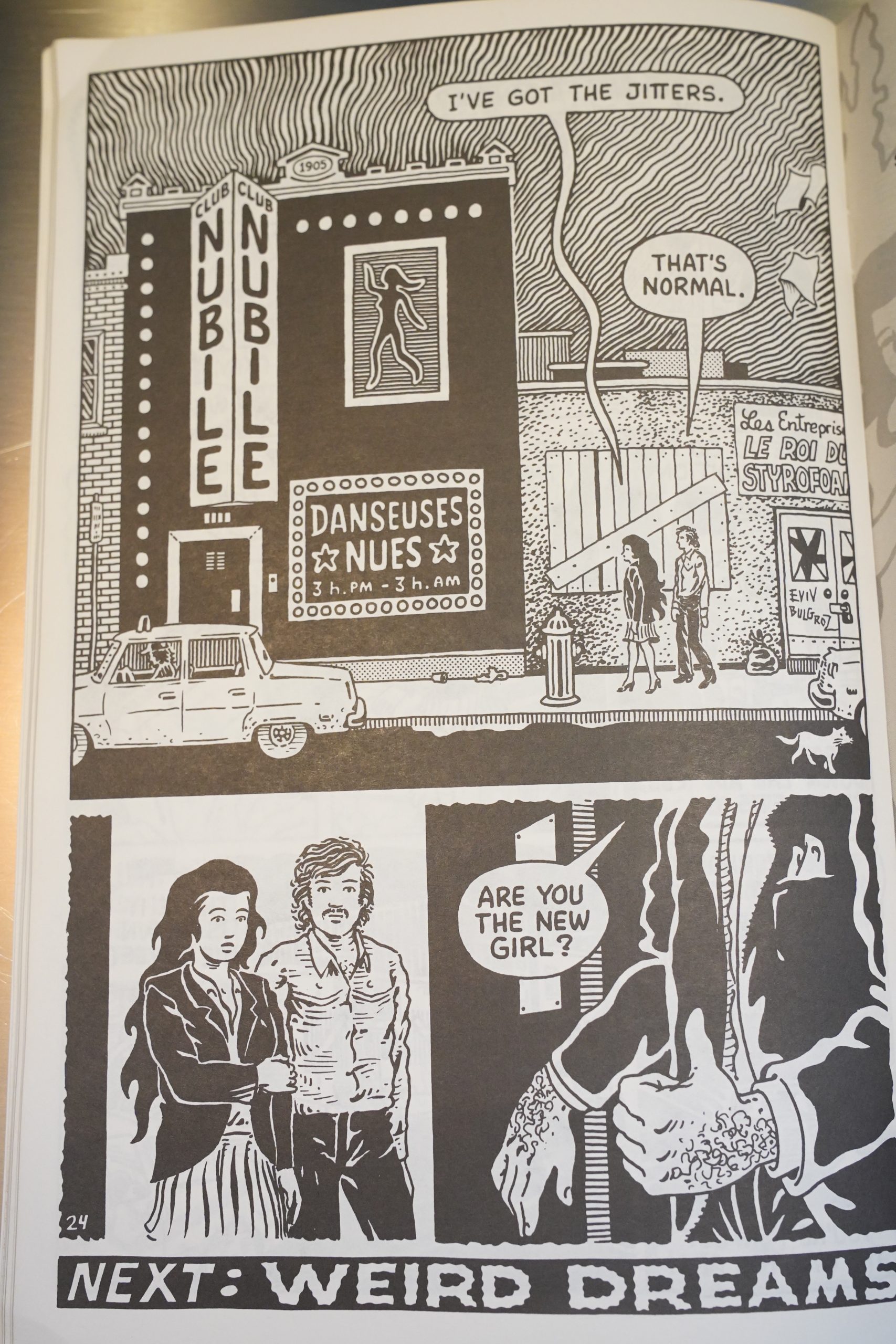

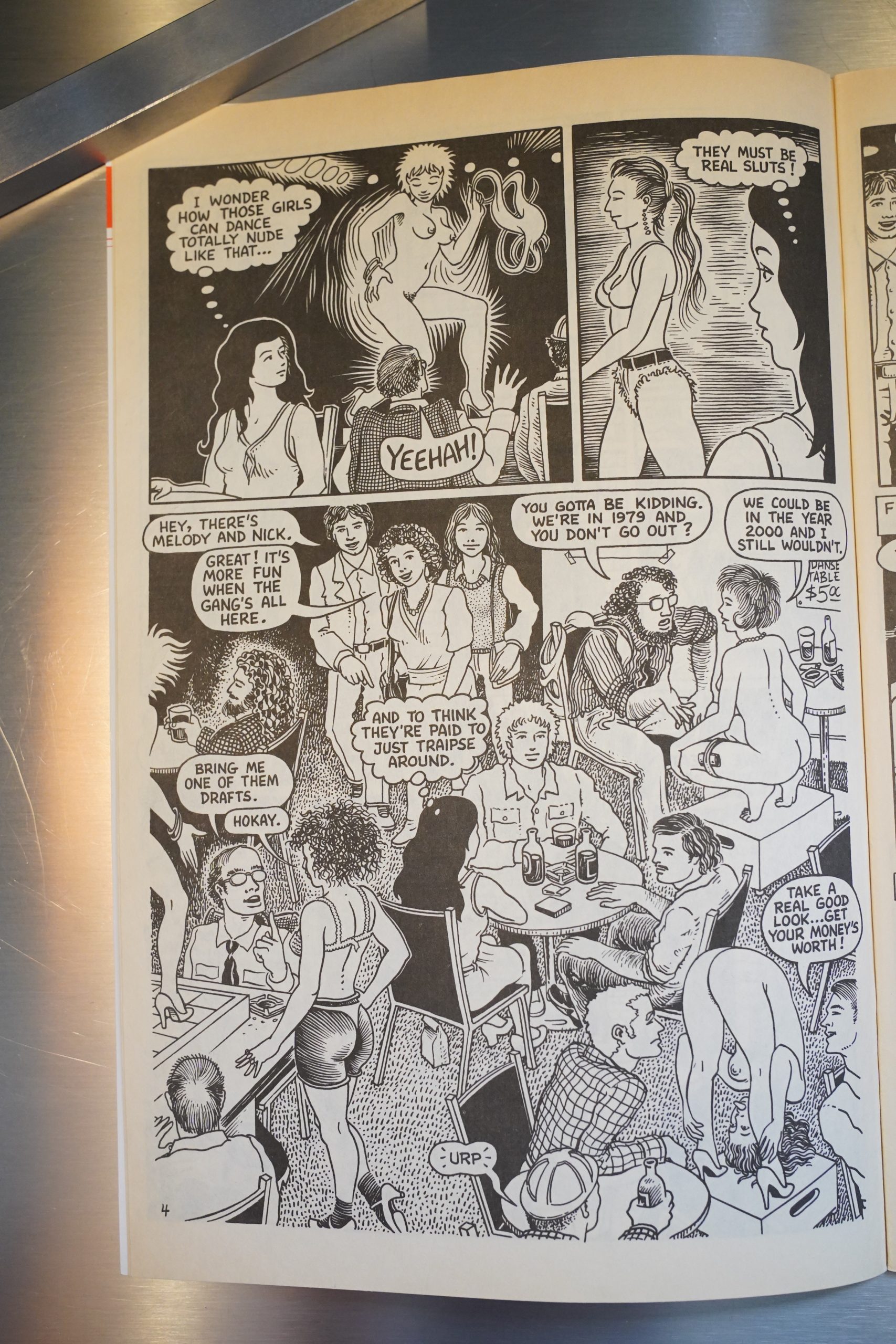

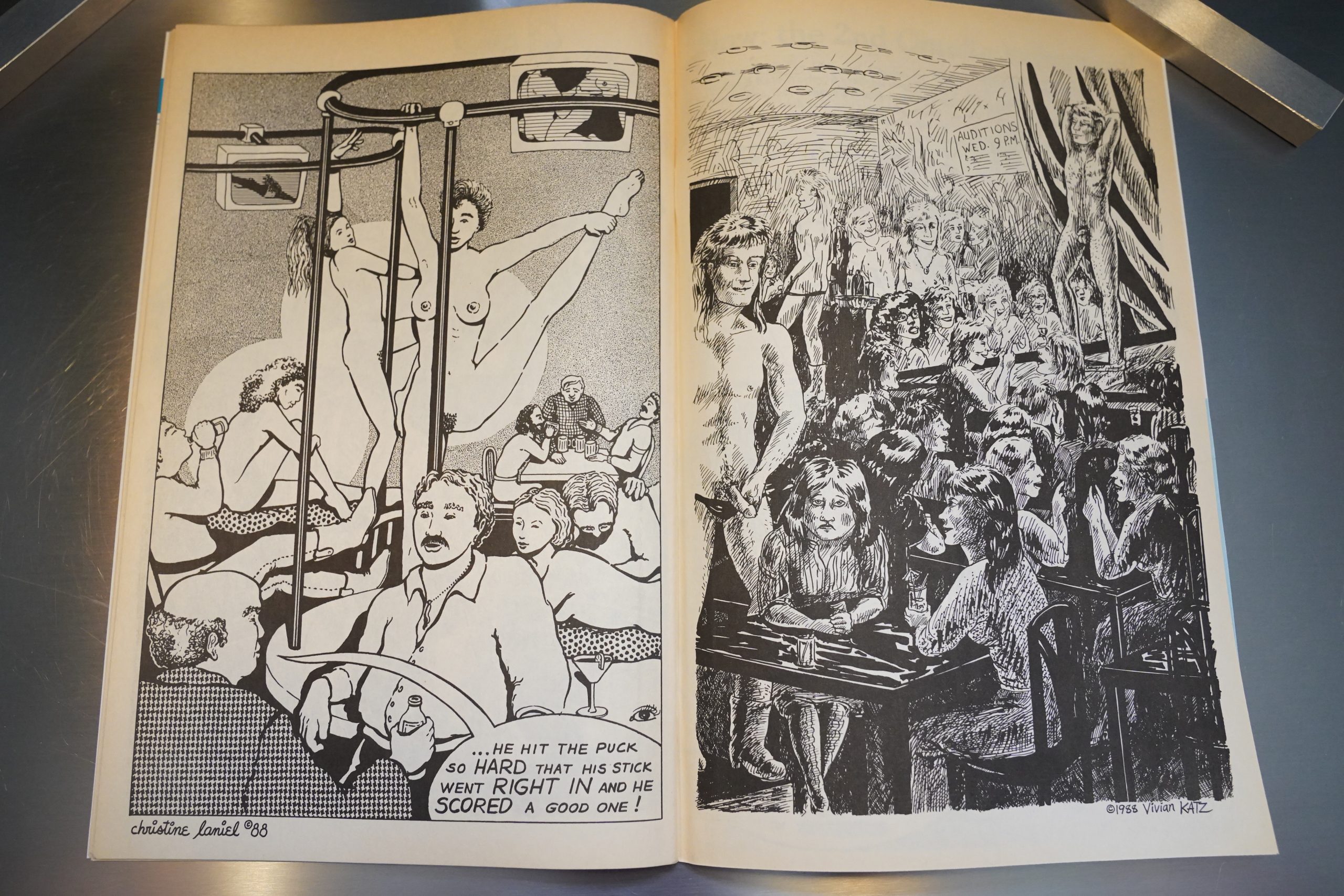

I guess the most innovative thing he does are these tableaux from strip bars, where we catch all the patrons and the dancers all at once. It’s sorta kinda oddly abstract, because the perspectives aren’t really meant to be realistic… it’s interesting.

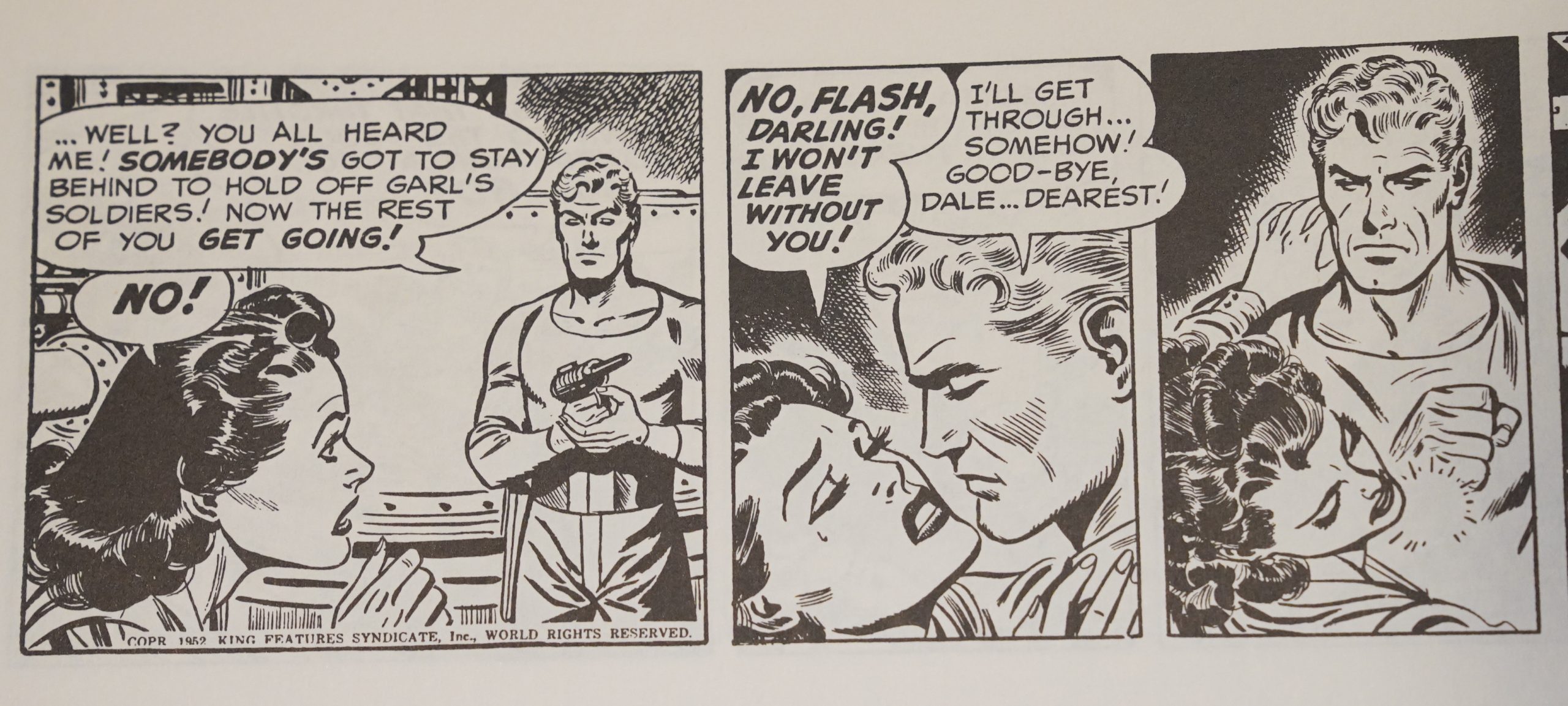

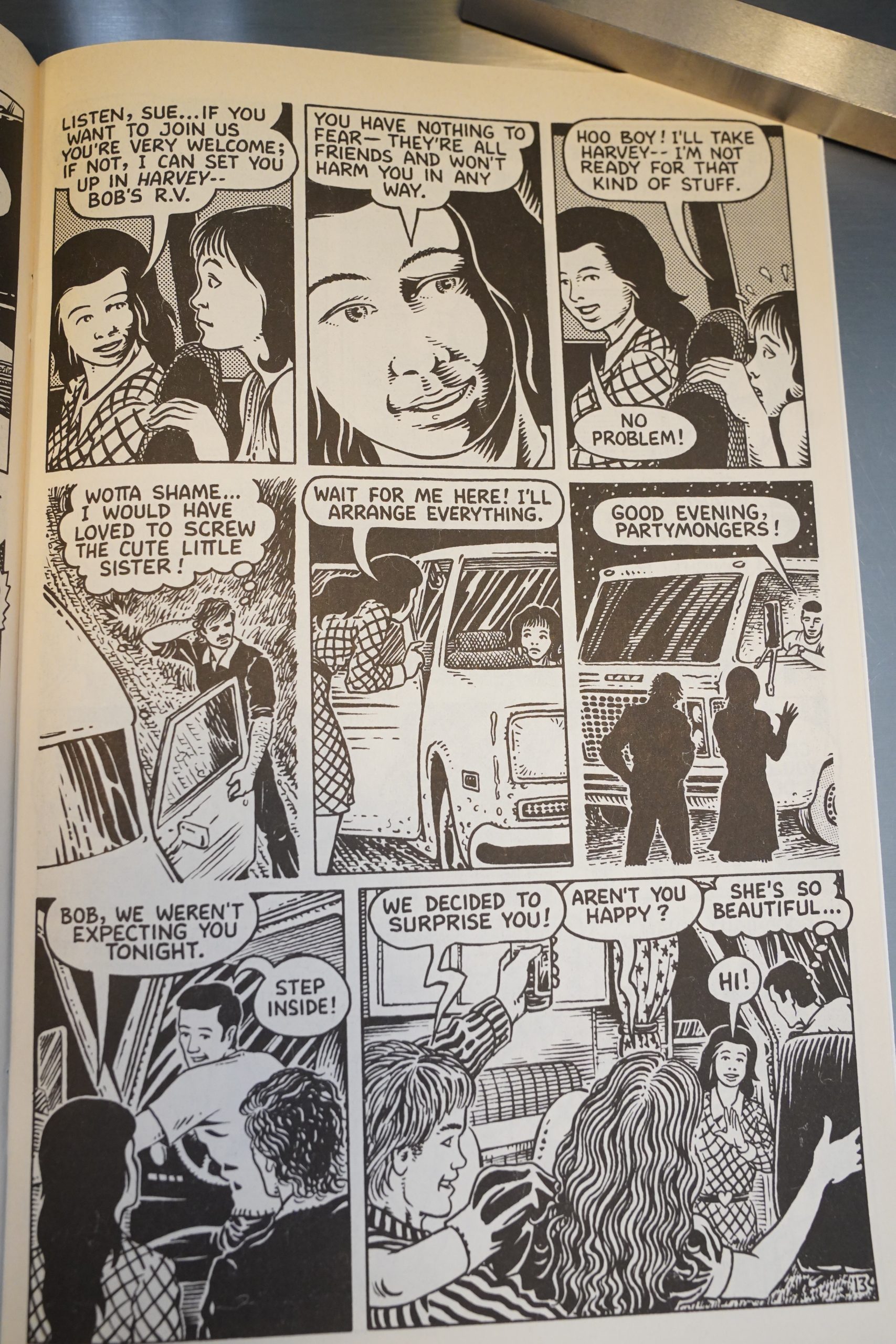

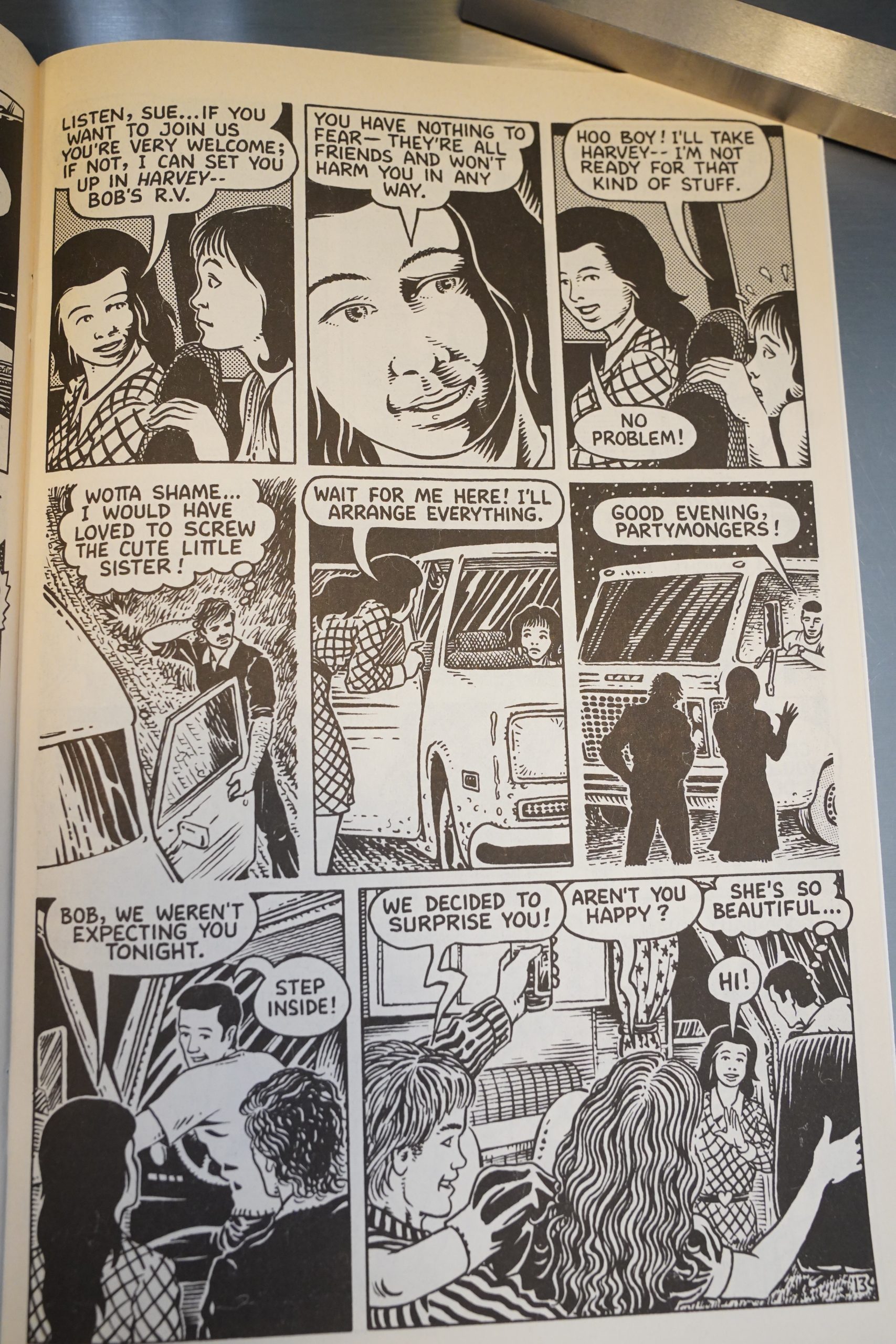

The storytelling overall is befuddling. I mean, if you think about it too much. It’s Rancourt’s autobio, but we’re somehow given more insights into the though processes of other people, and things that happens when Melody’s not around, than we’re given into Melody herself. So we have an omniscient author point of view… except what’s actually going on with Melody herself. I mean, we get thought bubbles like the above, but it’s surface stuff.

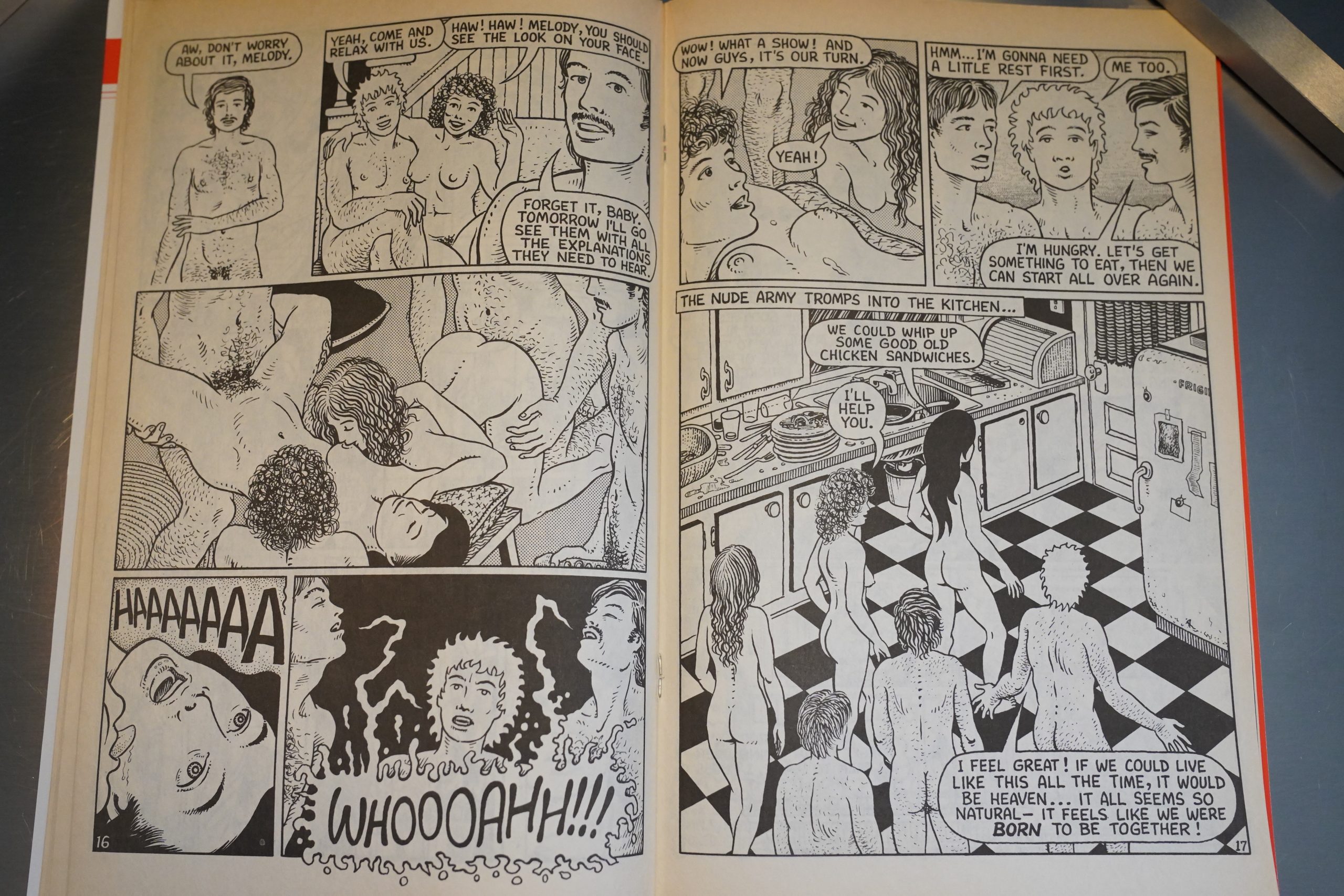

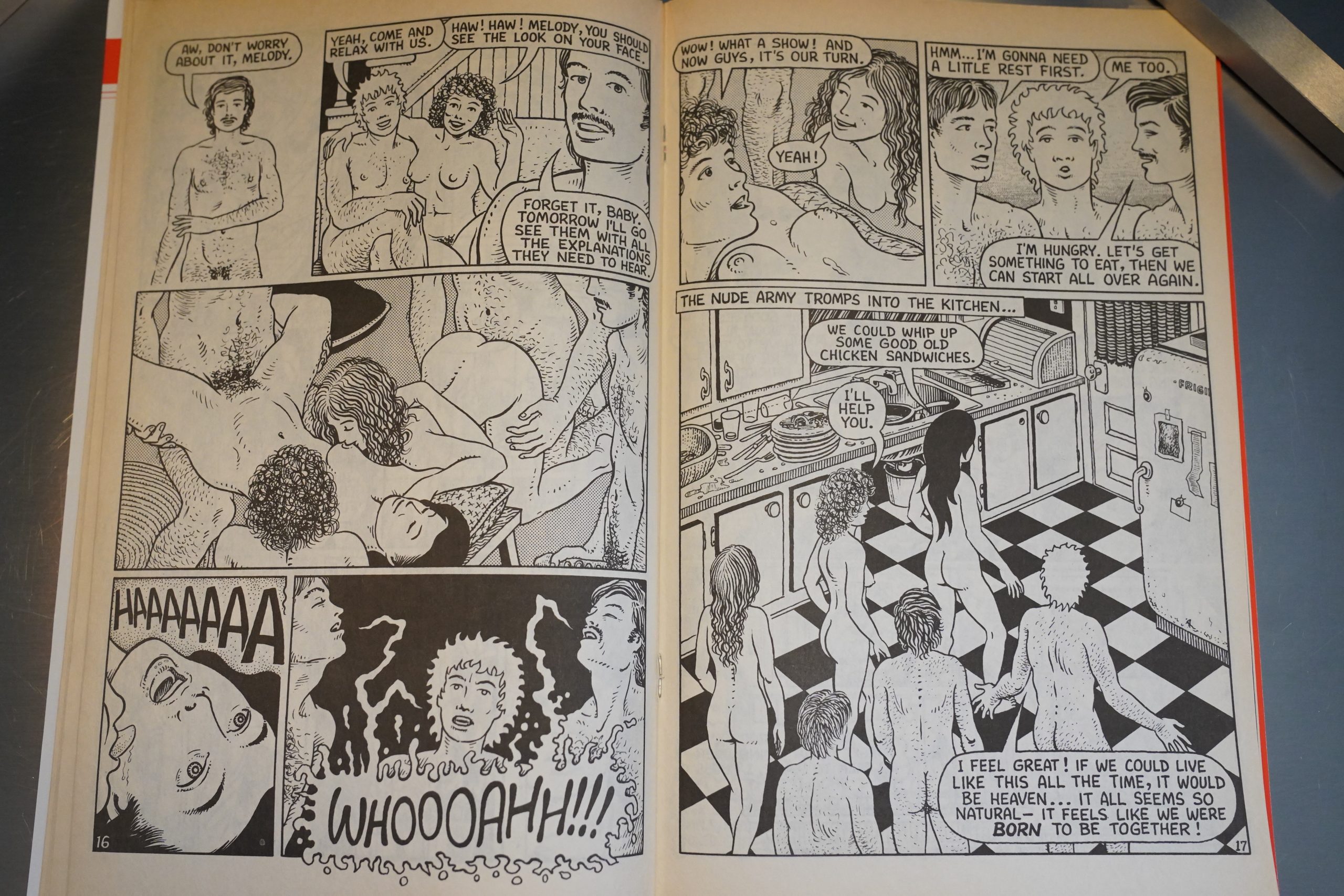

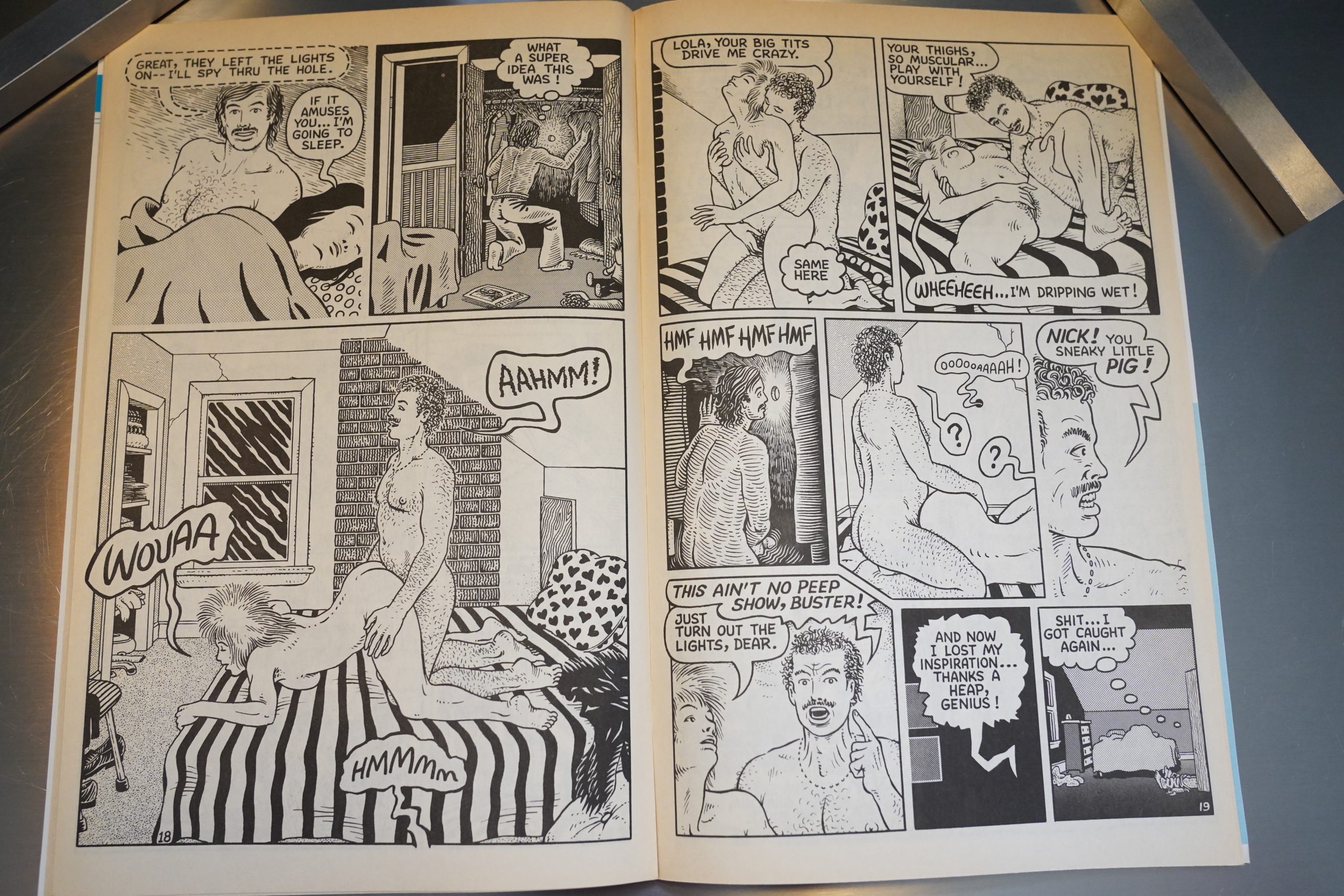

The collected edition of the first issues is called The Orgies of Abitibi, and that’s, of course, a major selling point here. They’re very amiable orgies… down home and relaxed.

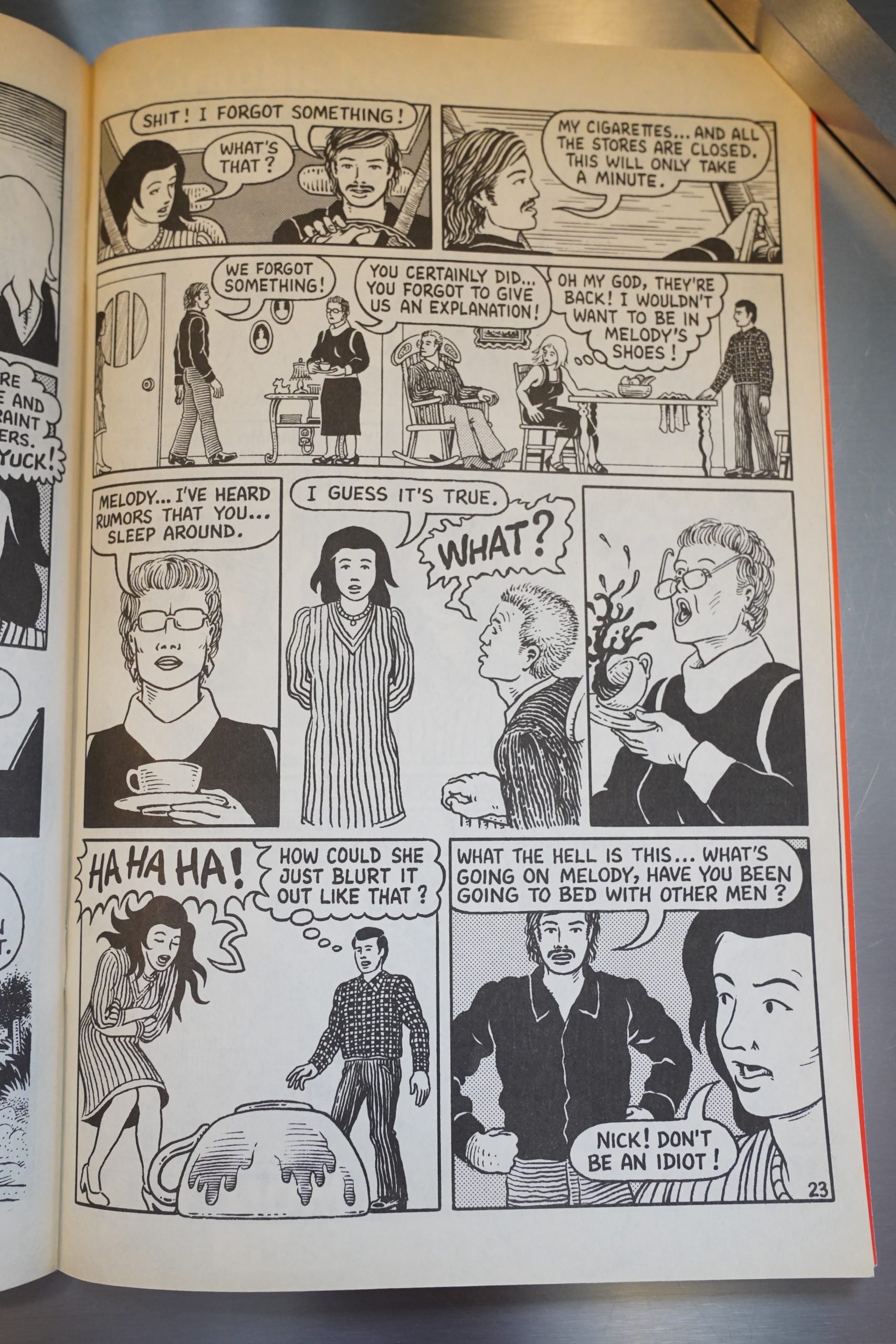

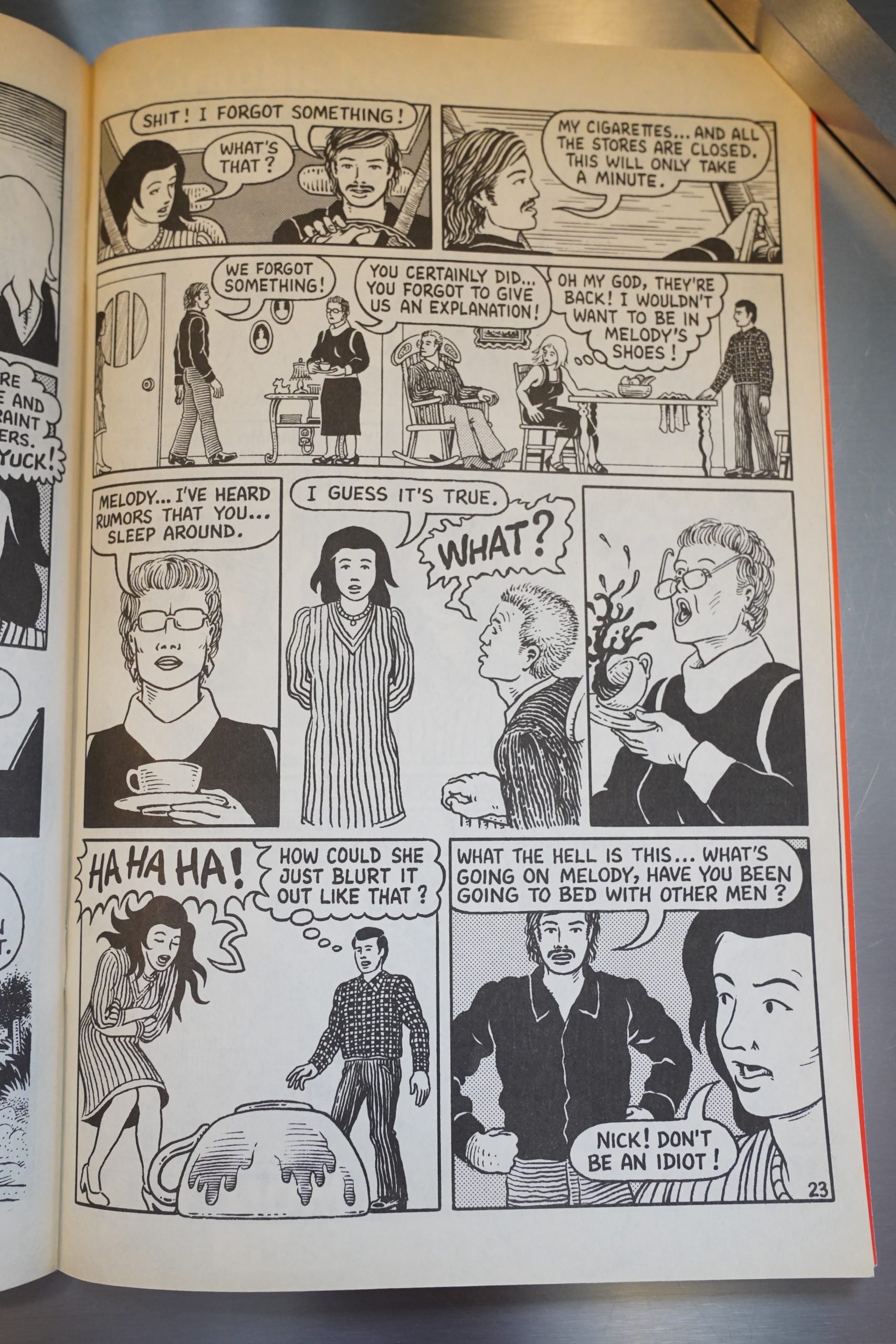

Melody is portrayed as being pathologically honest… They way she’s drawn, it’s easy to forget that she’s 19 here, and her behaviour makes more sense in that context.

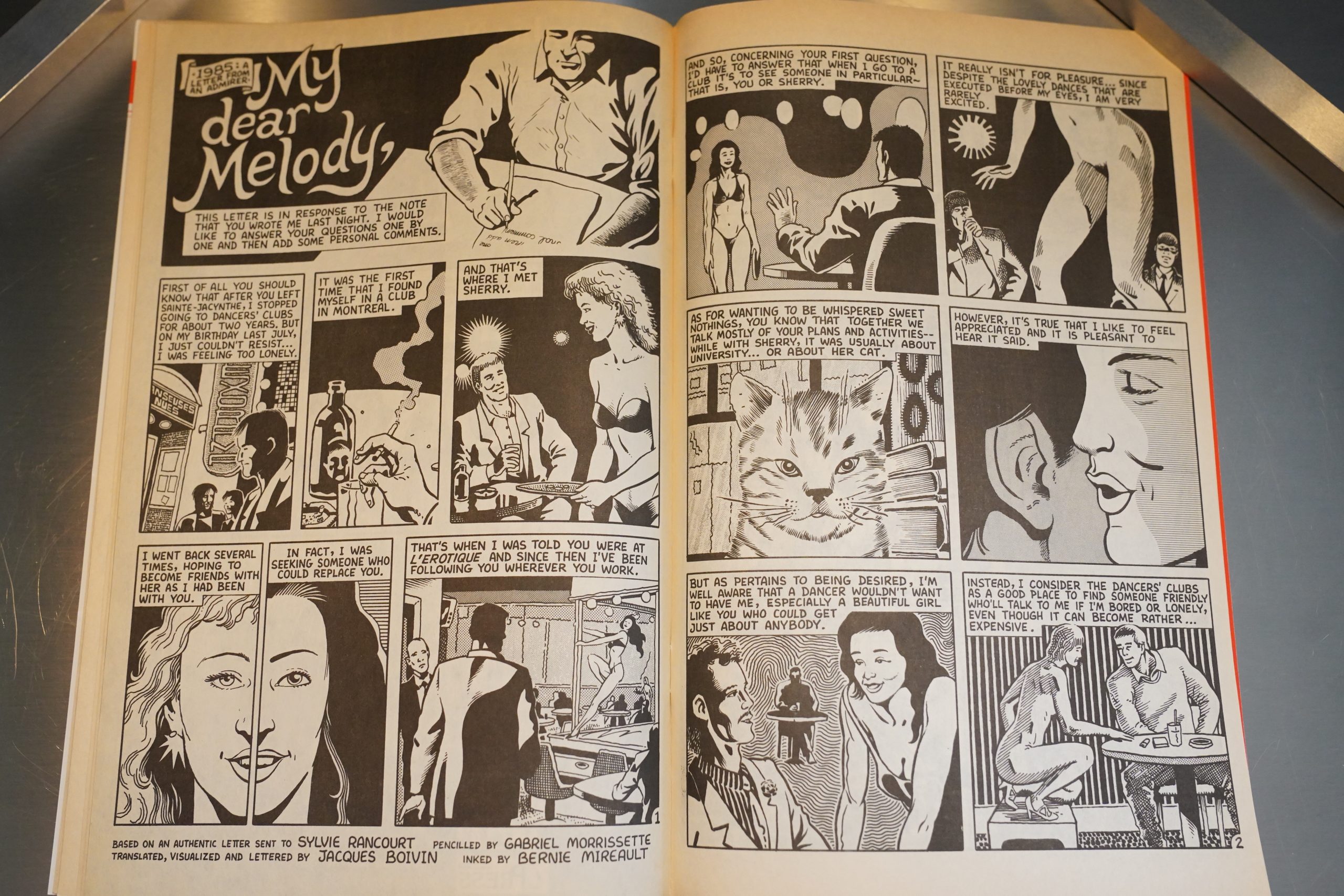

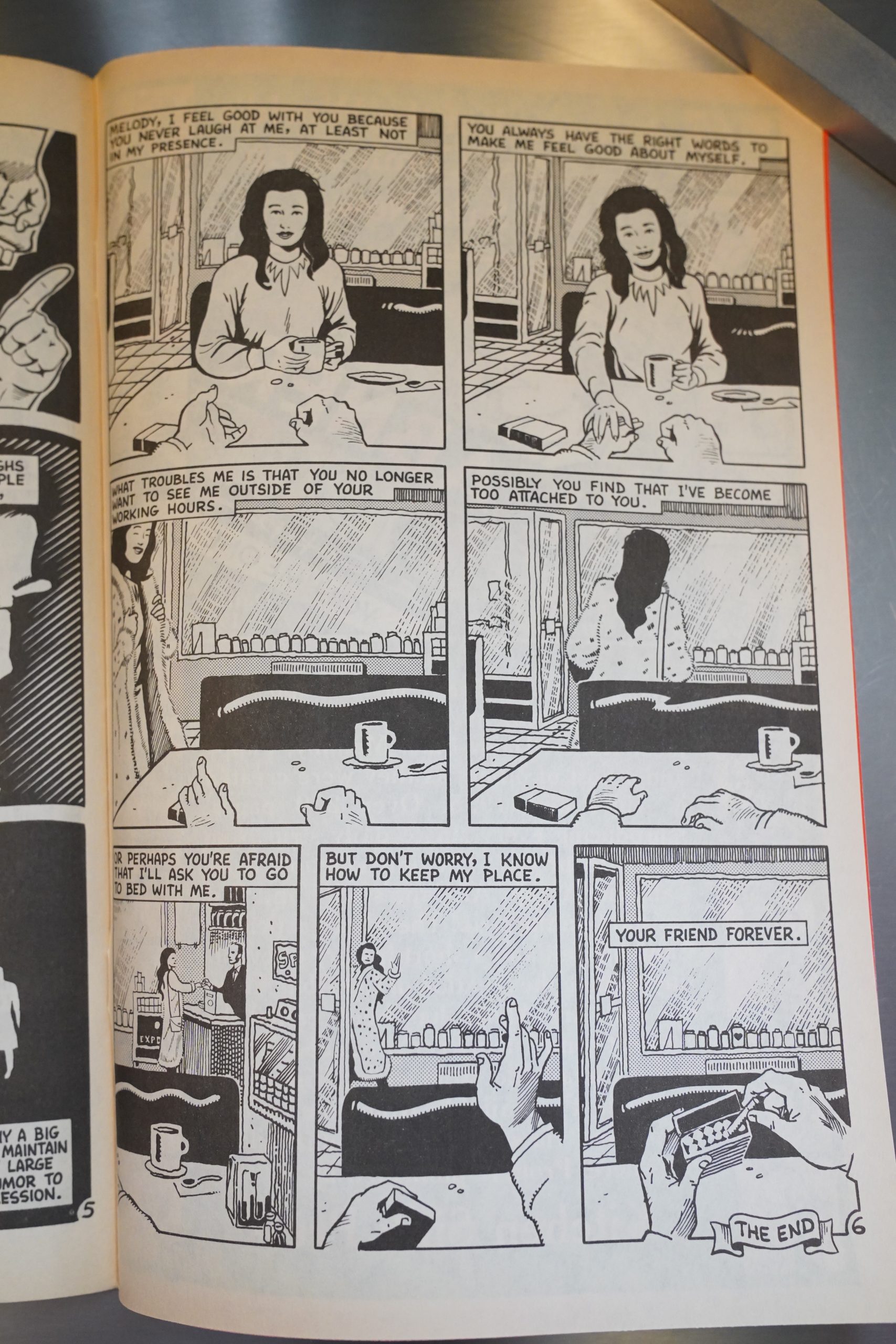

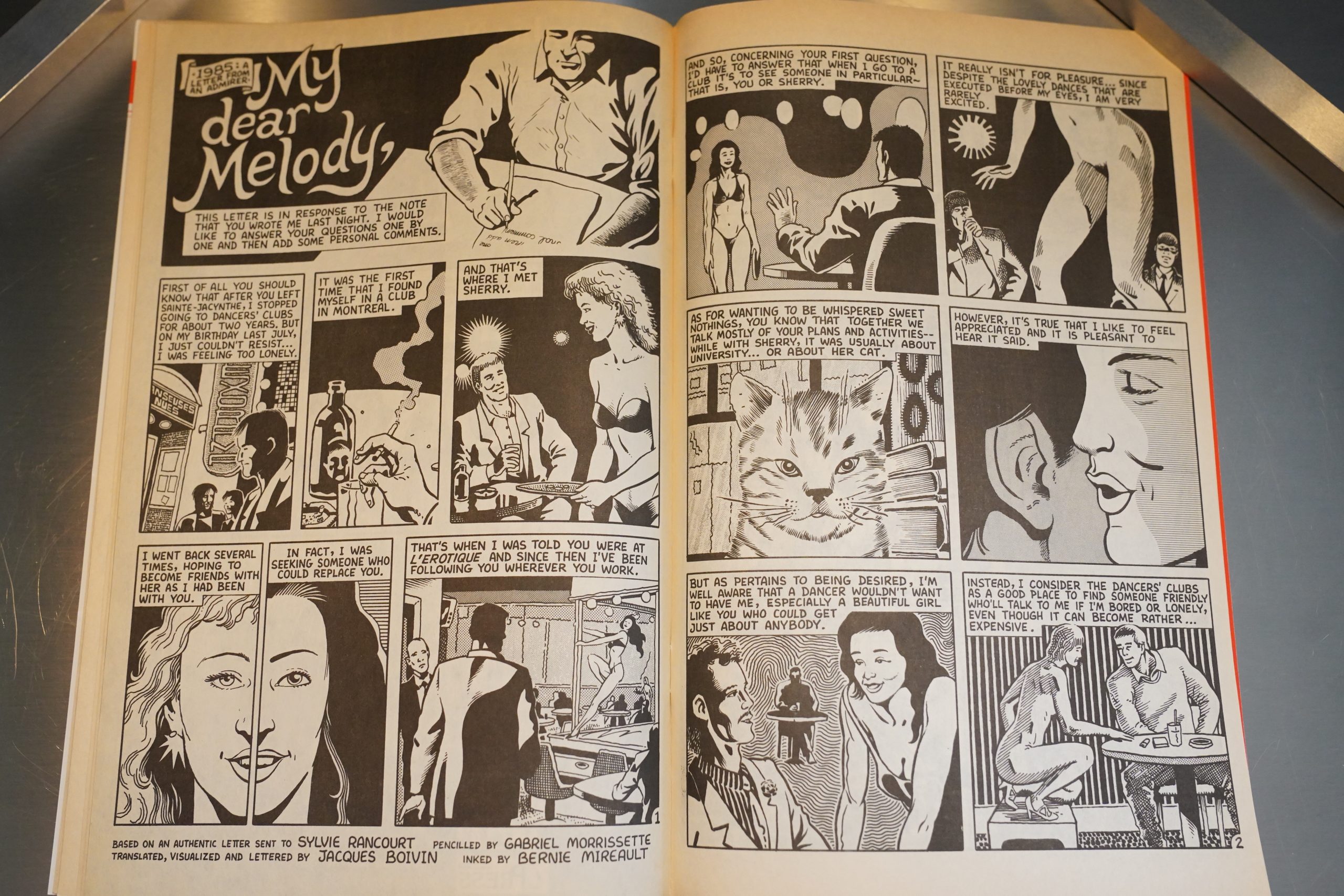

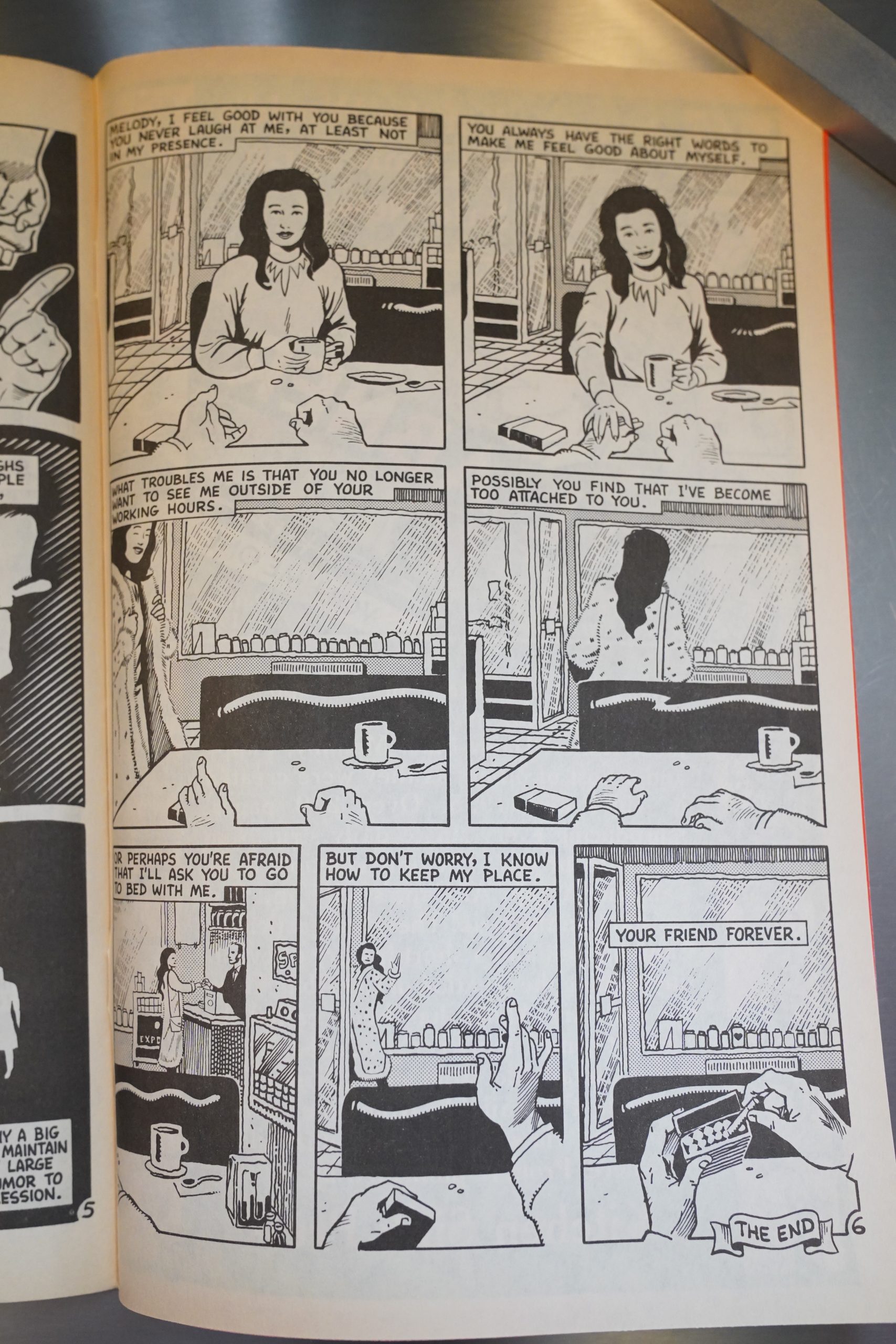

In each issue, we get a solid 24 pages of story, and then a there’s also back up features. A few of these are illustrated versions of letters she’s received, and they veer from the wistful…

… to the unnerving, and sometimes in the same story.

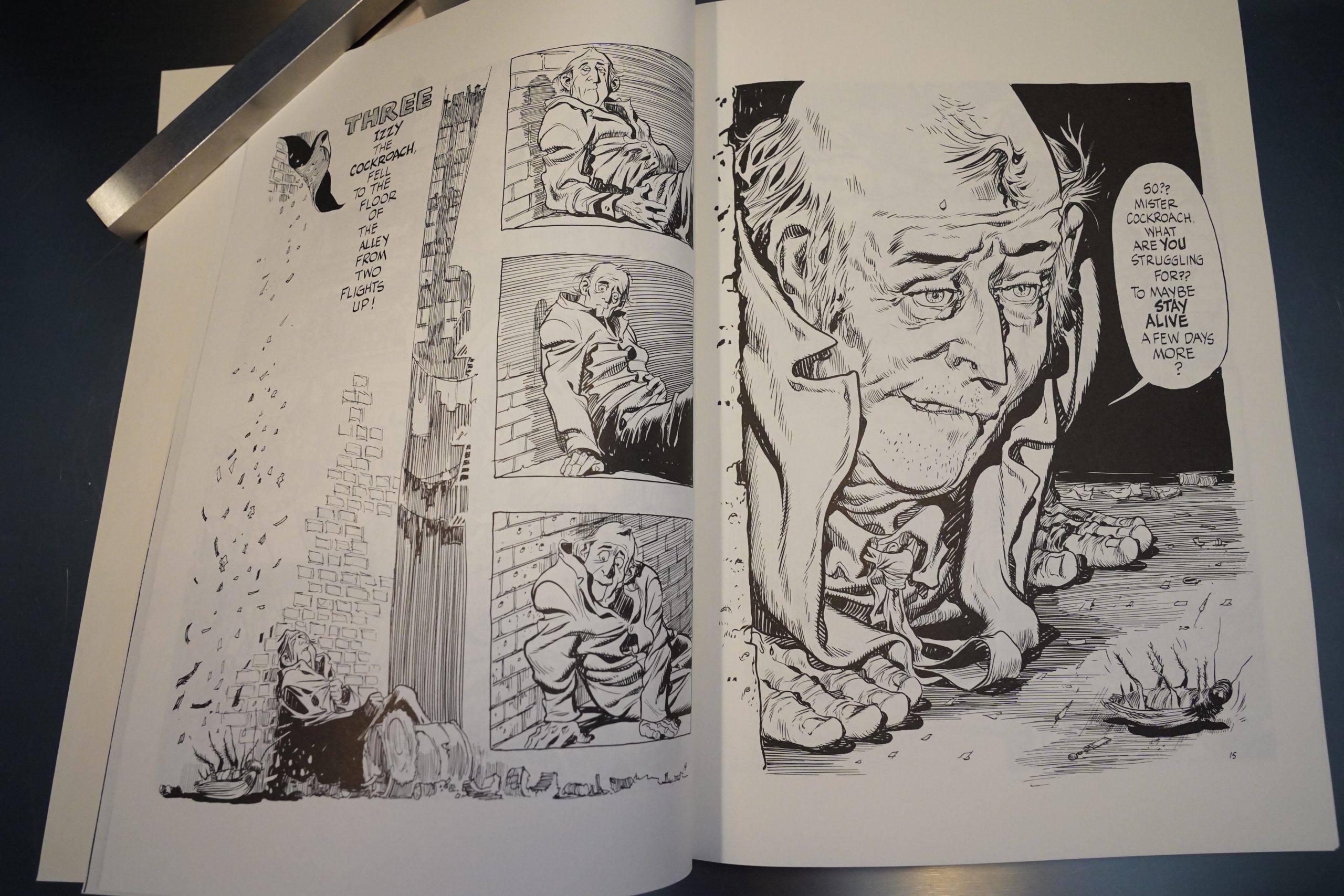

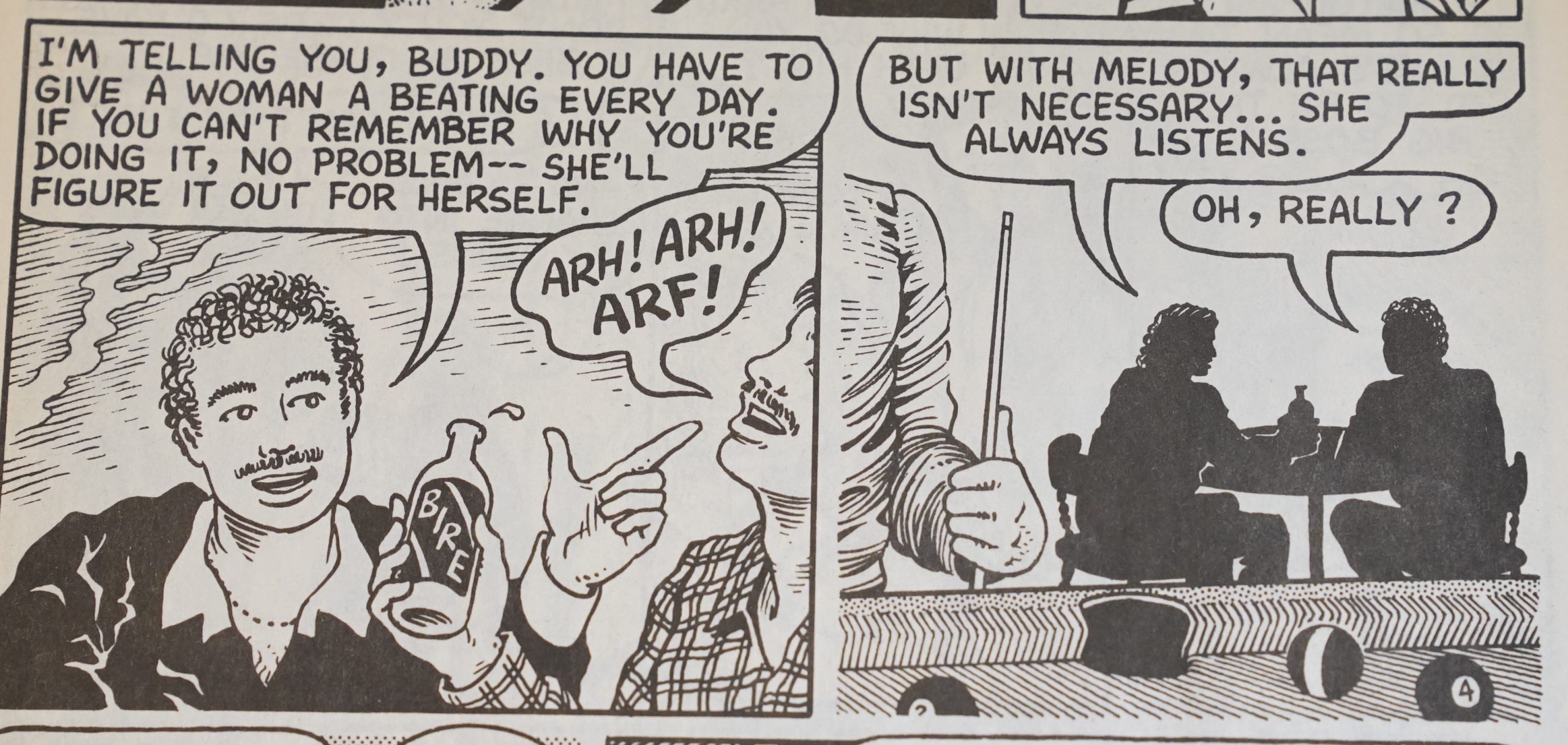

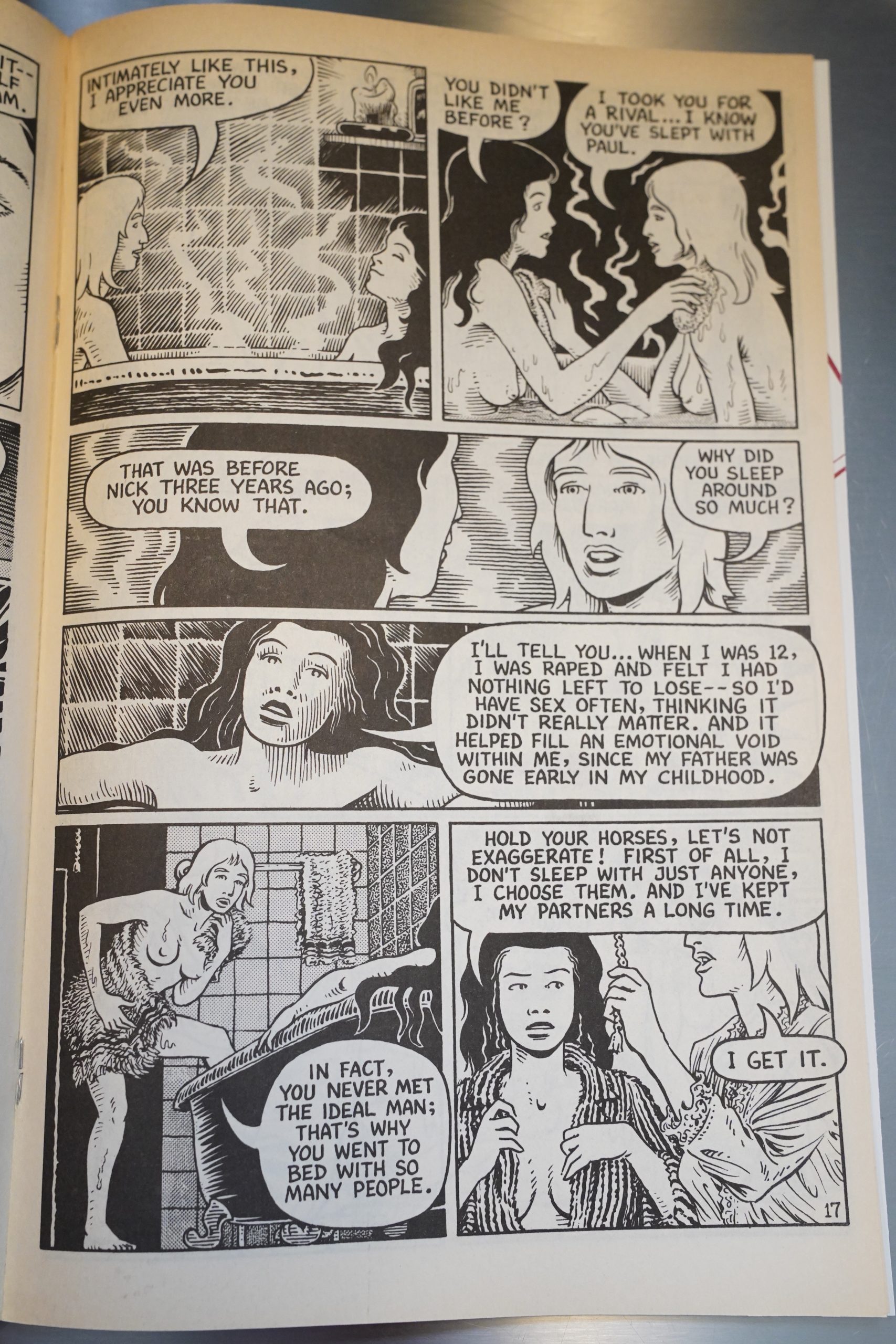

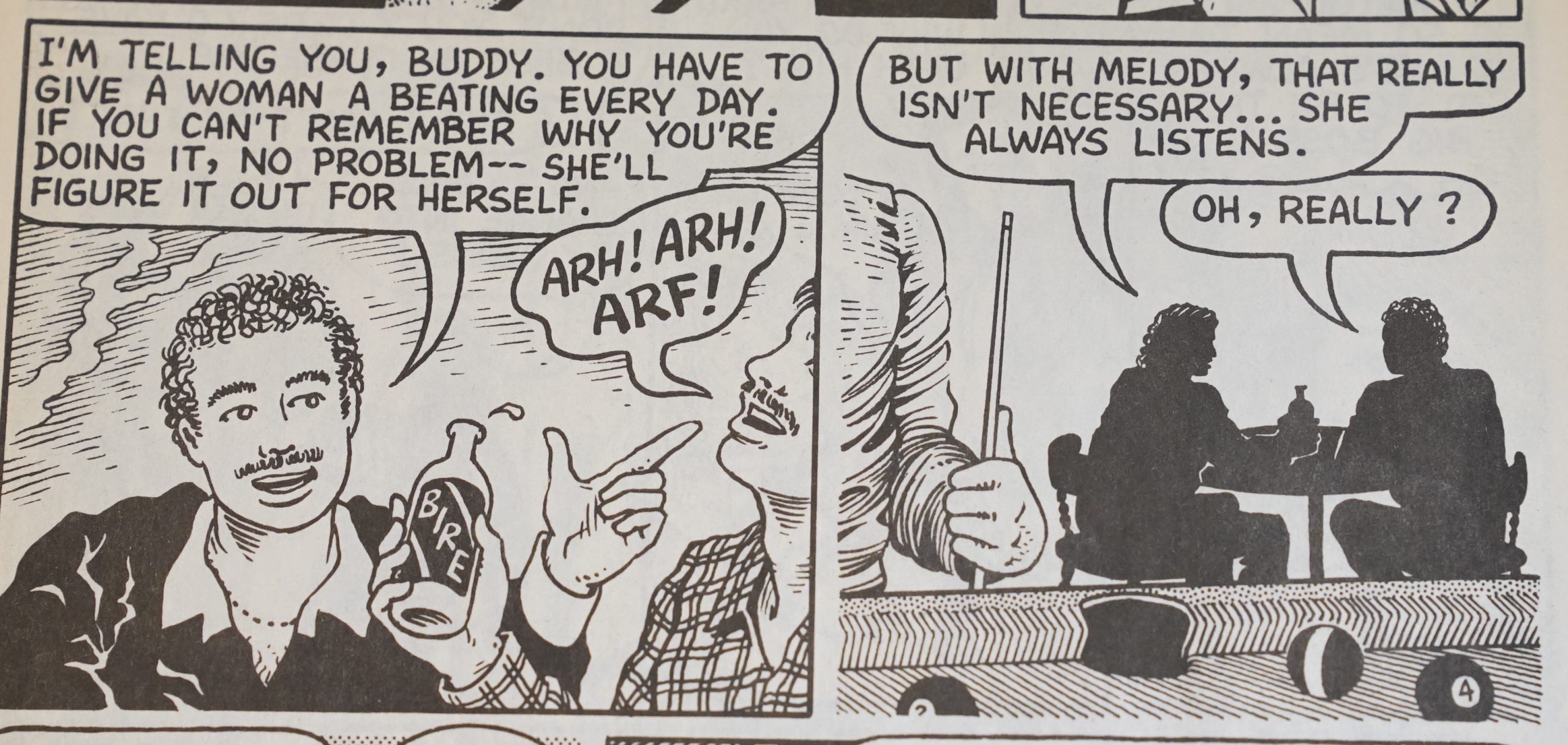

The autobio-with-an-omniscient-point-of-view leads to these jarring scenes, where you’re thinking — where did this come from? And moreover, Rancourt never comments what she’s depicting… Oh, writing this, I’m starting to realise what’s so special about the storytelling in this series: It’s an autobio book that feels oddly impersonal; it feels very distanced.

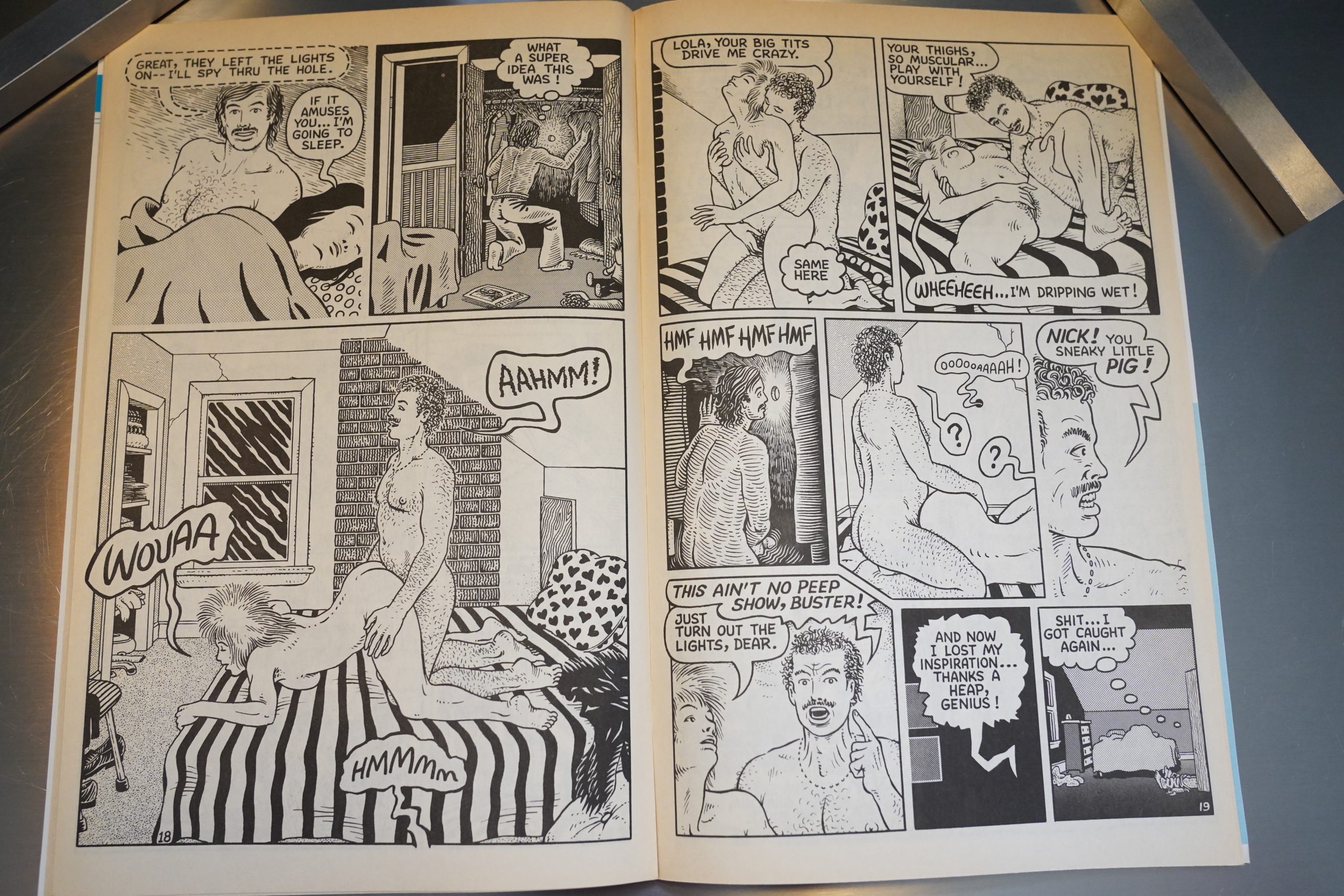

And it’s also — here she’s depicting her husband having made a peep hole into their guest room so that he can peep at guests having sex. And again, she doesn’t really comment — she depicts herself saying “if it amuses you” and doesn’t participate, but that’s as far as it goes.

It’s a strange lack of affect.

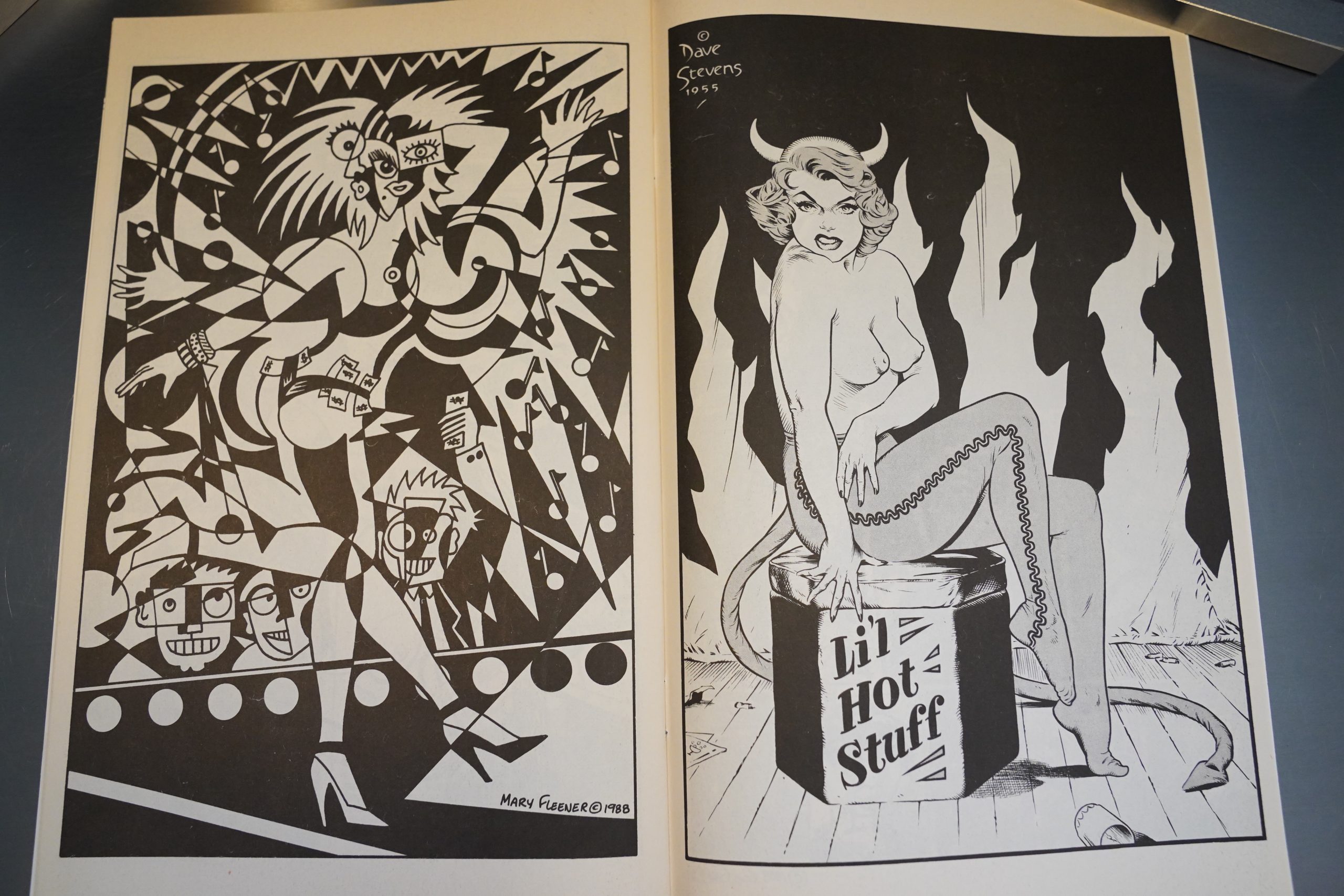

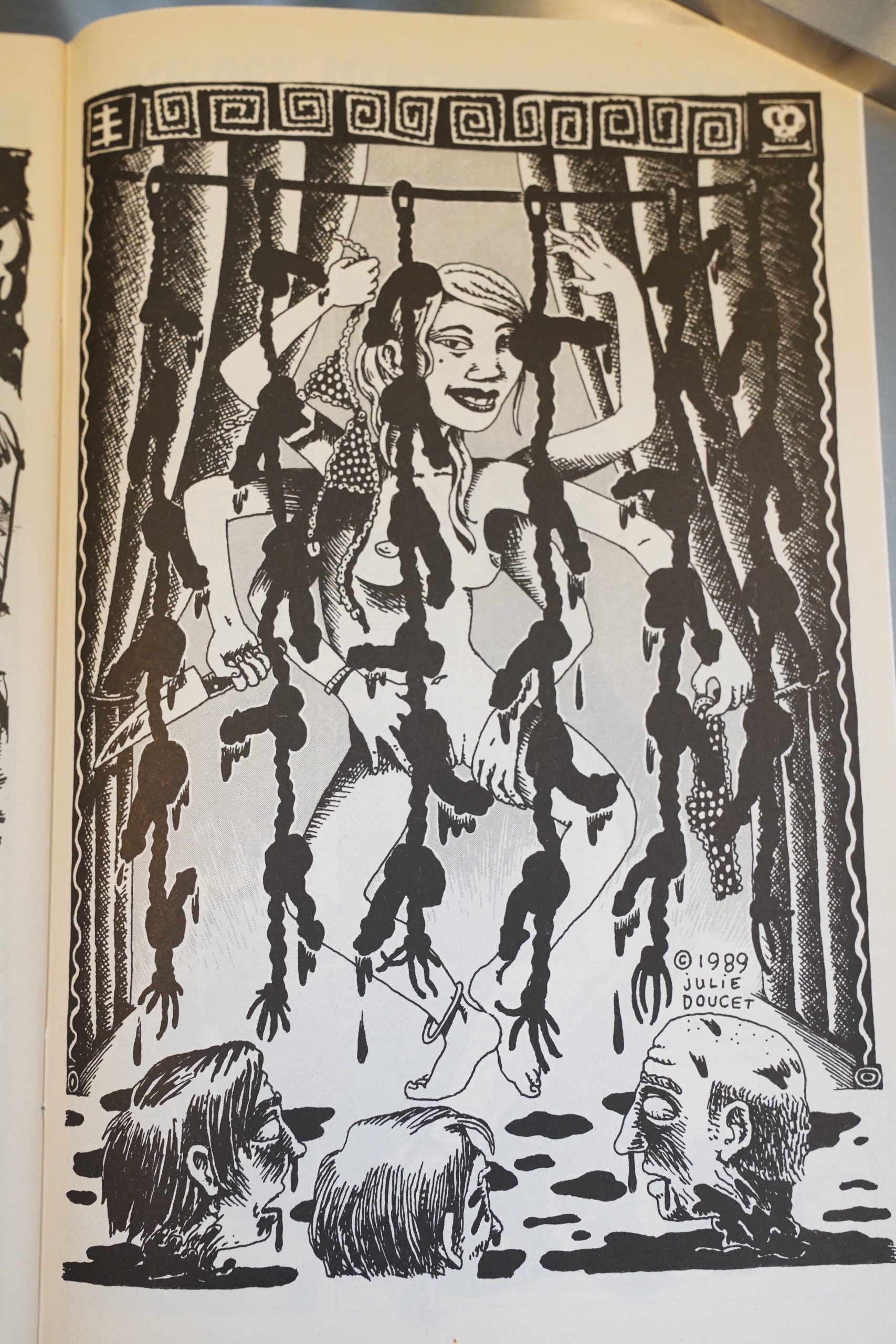

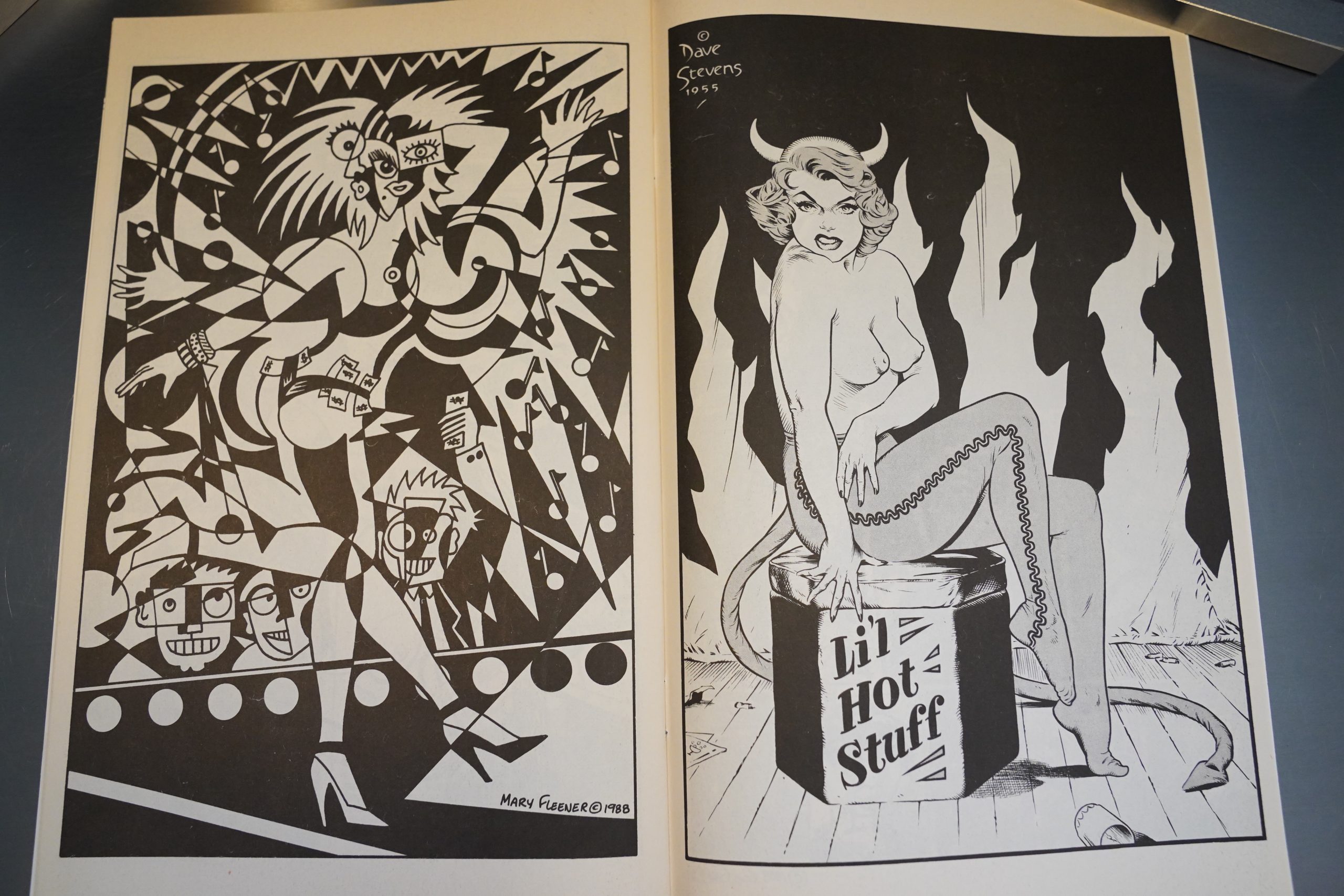

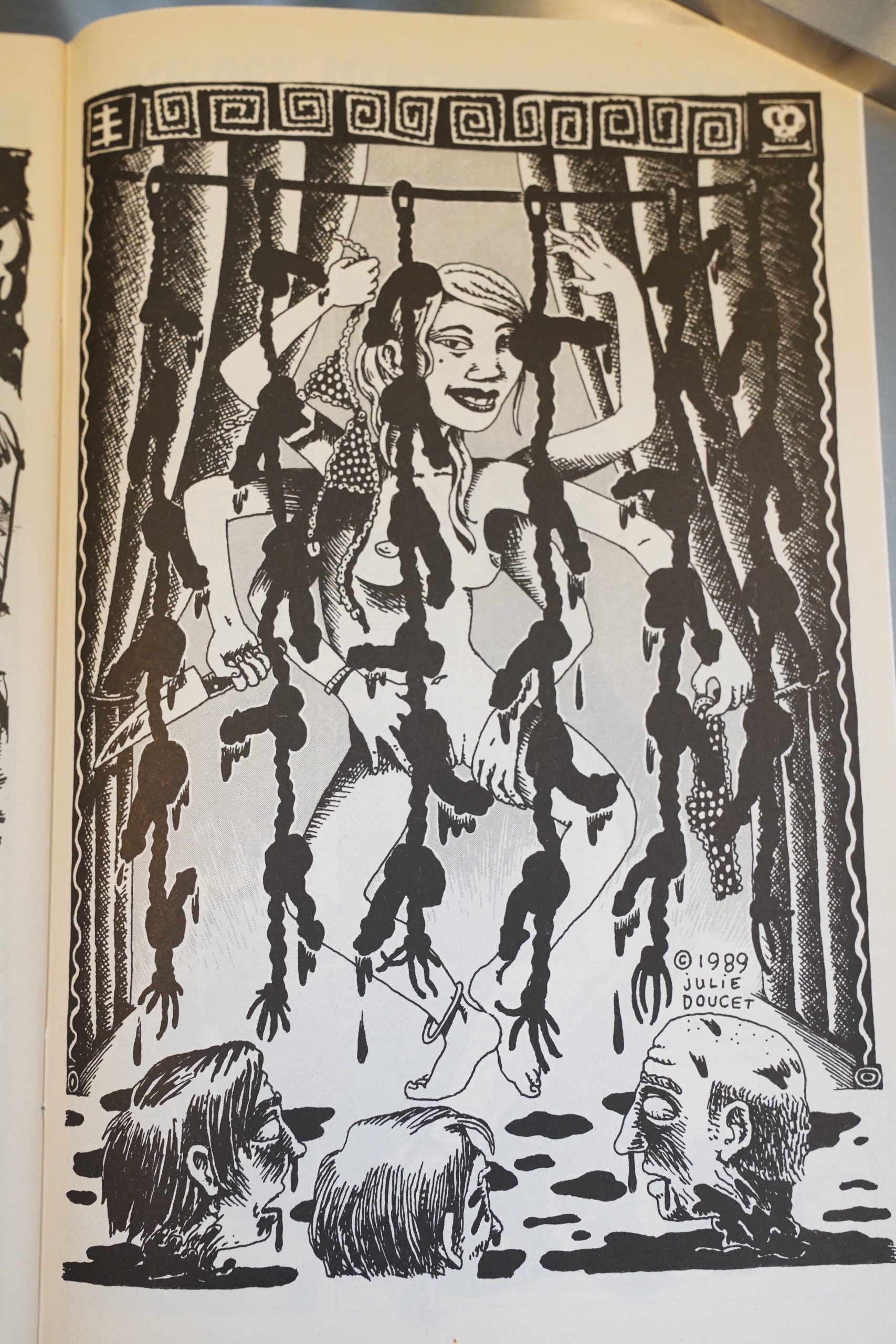

In the issues where there’s no illustrated letters, we get pin ups. The male artists mostly go for glamour shots; the female artists mostly go for humour, horror or disgust.

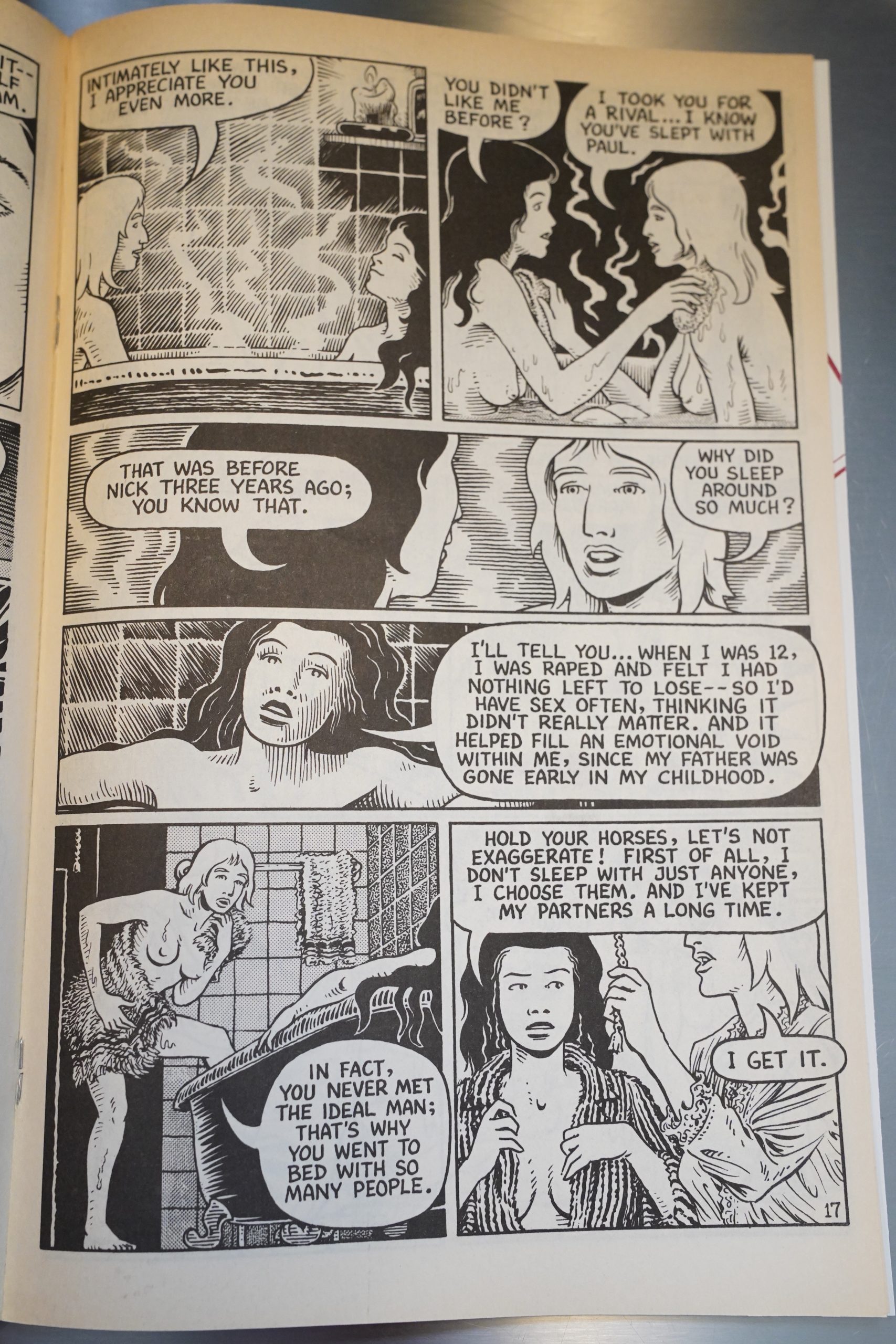

That thing I said about a lack of affect? In the fourth panel — this is the only mention of this in this book.

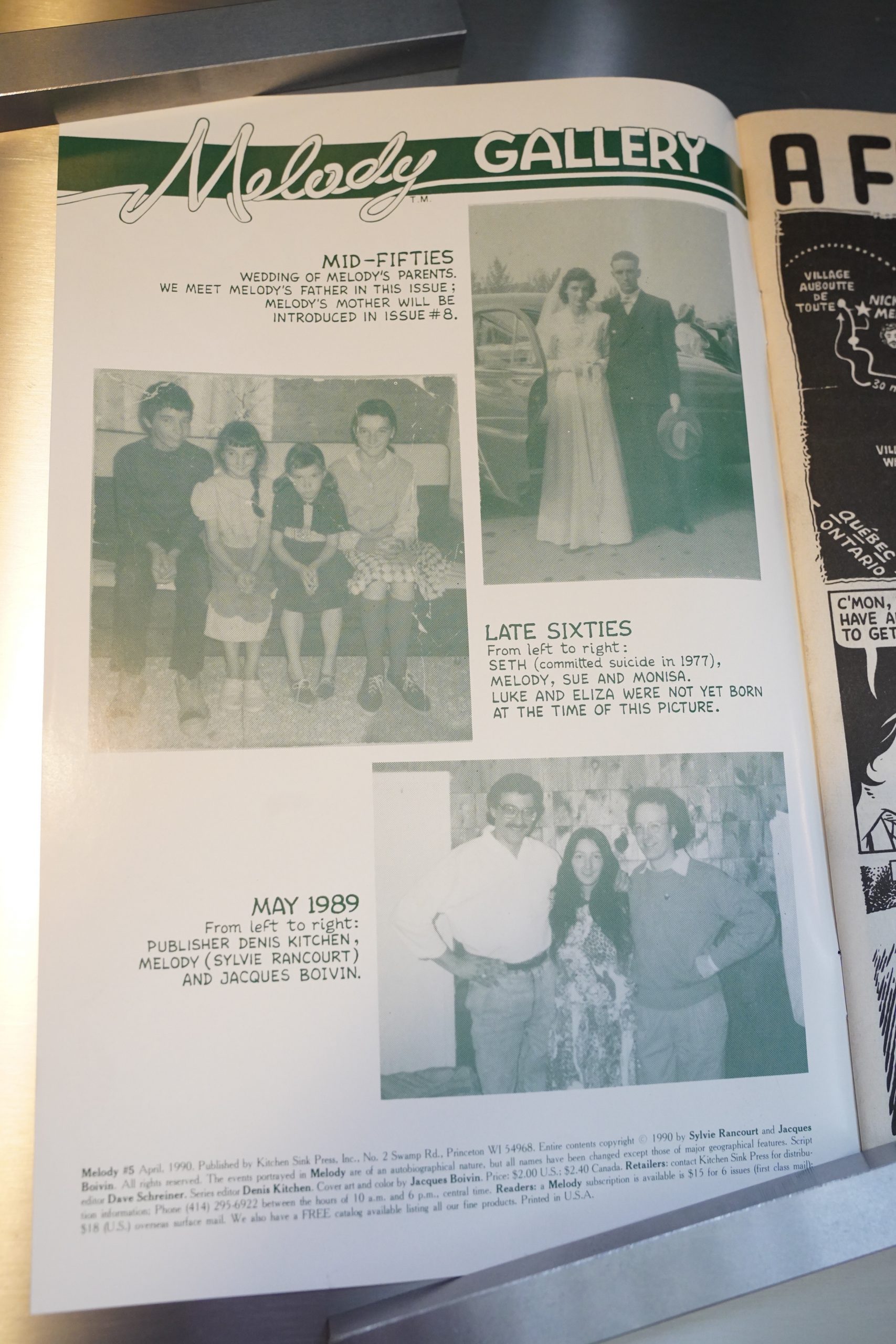

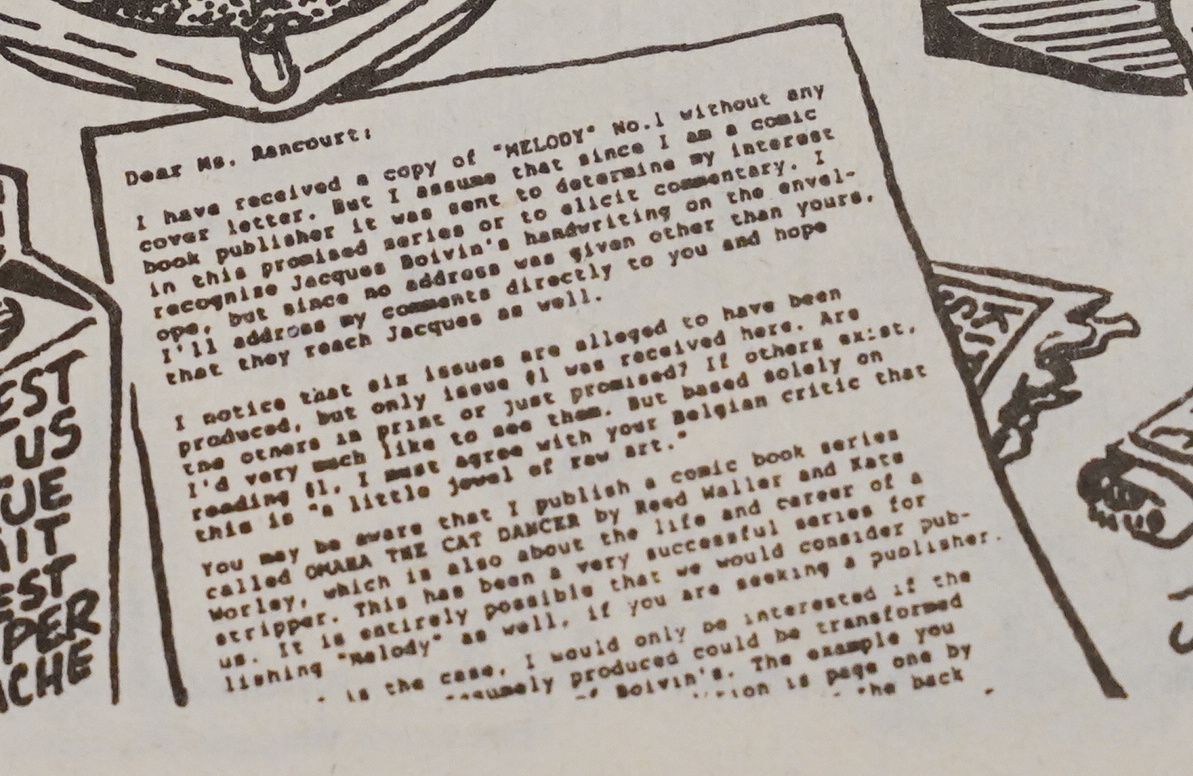

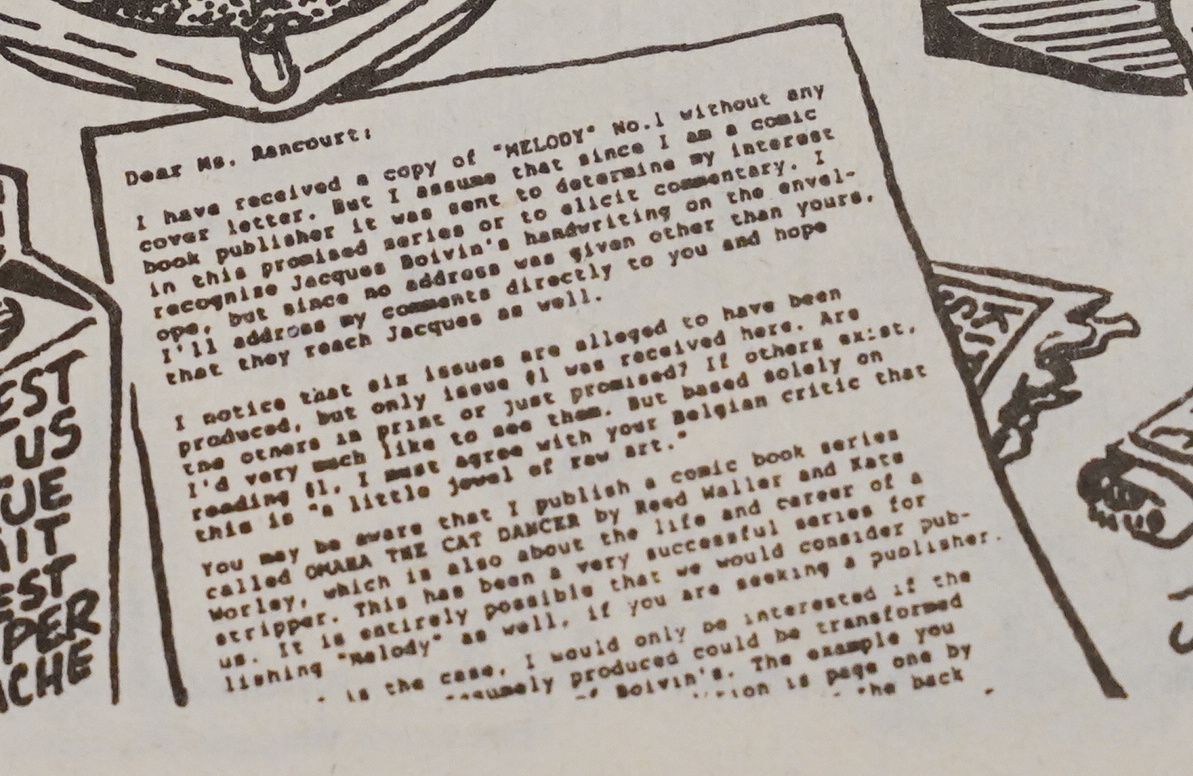

Huh. They had the covers for the first ten issues drawn already? They’d really been planning out this entire story…

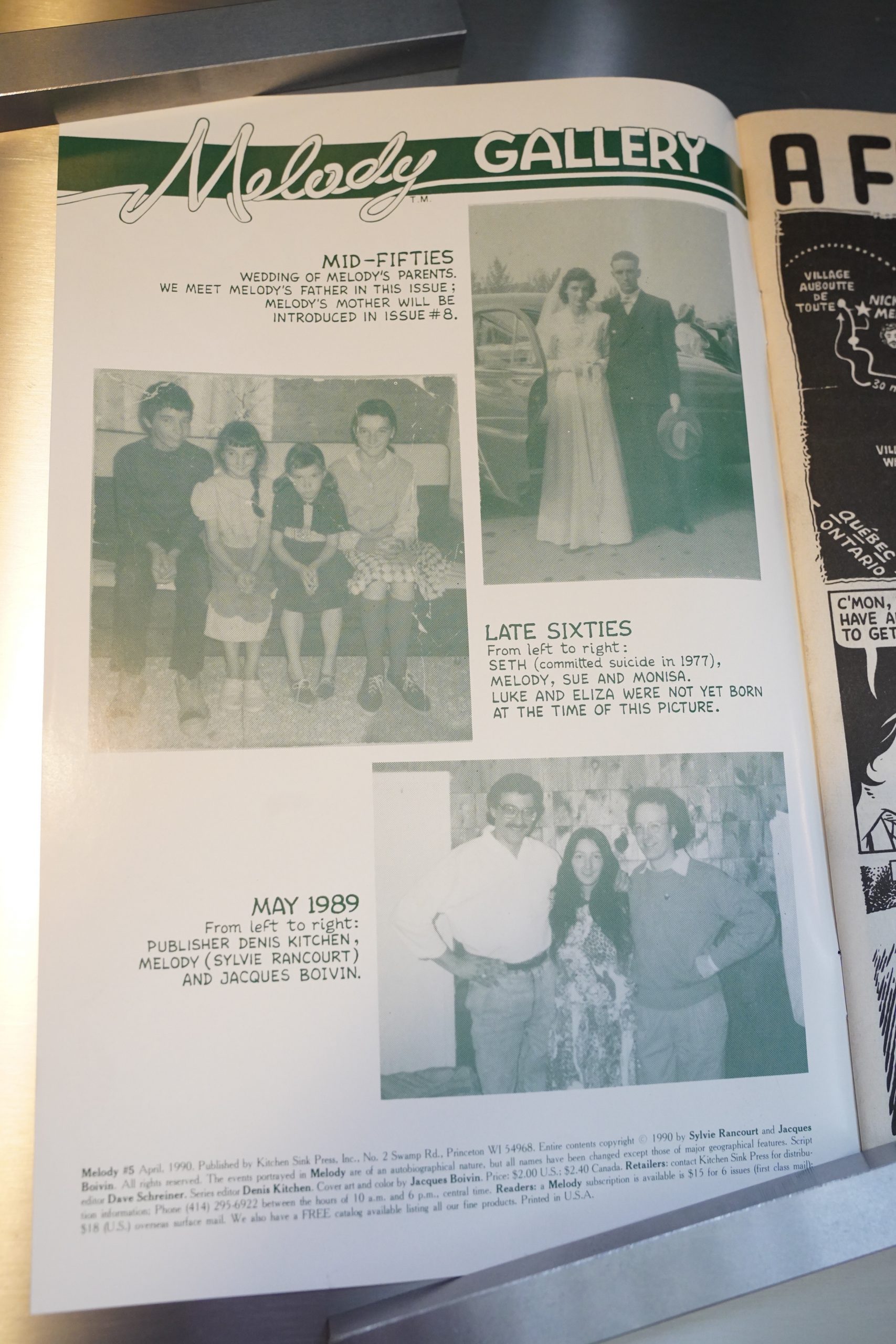

And that’s the only mention of her brother committing suicide.

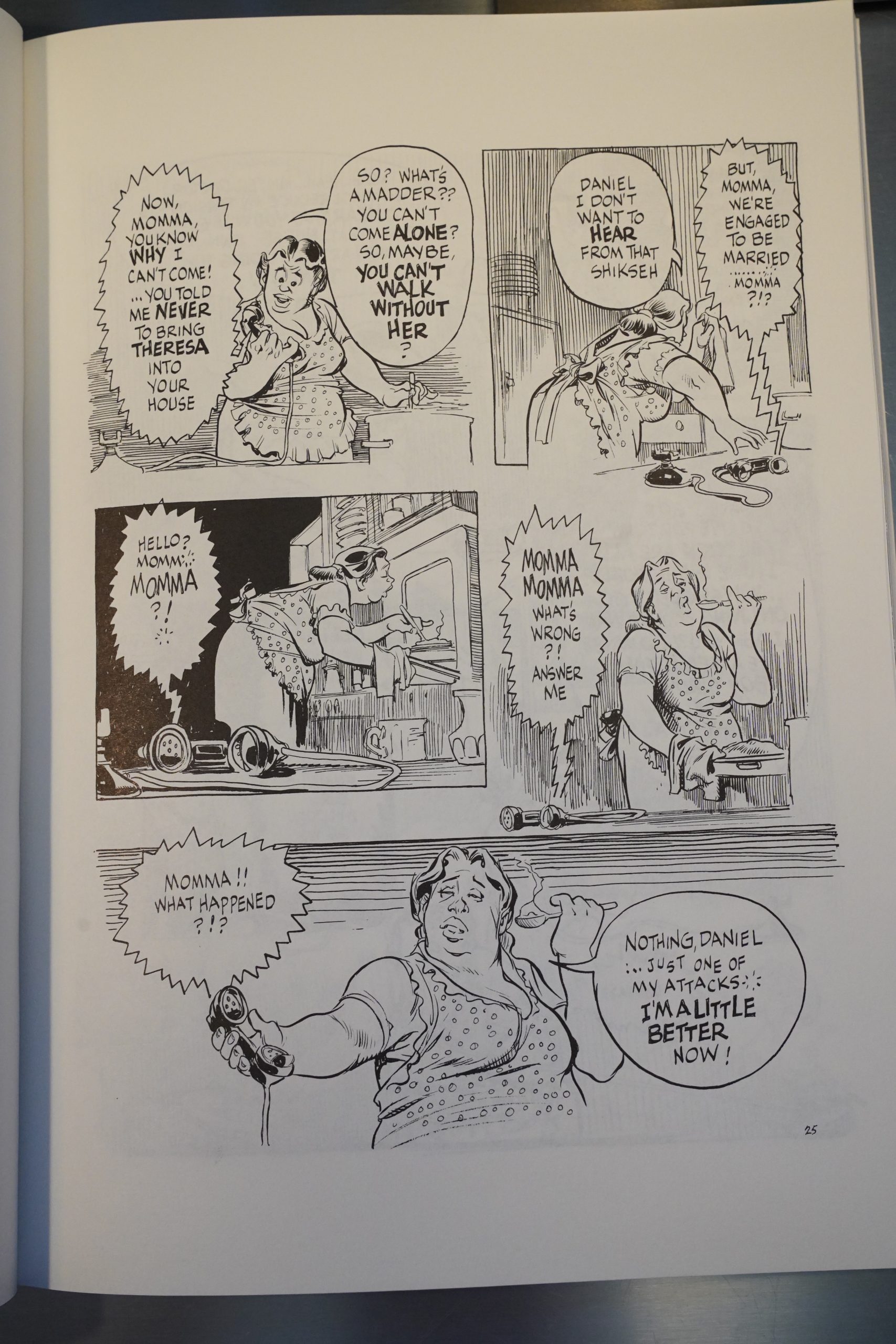

The must befuddling issue of them all is this one. Melody meets up with her family, and she ends up bringing her seventeen year old sister home with her. But this turns out to be an orgy night, so she (with her usual lack of affect) gives her the choice of staying in a camper or joining the orgy.

Later in the book (the day after) her father comes storming in and gives her a proper chewing out, and her reaction is, basically going “hm, perhaps that was a bad thing to do? If he’s that angry, then that can’t have been right.”

It feels like reading some transmission from an alien planet.

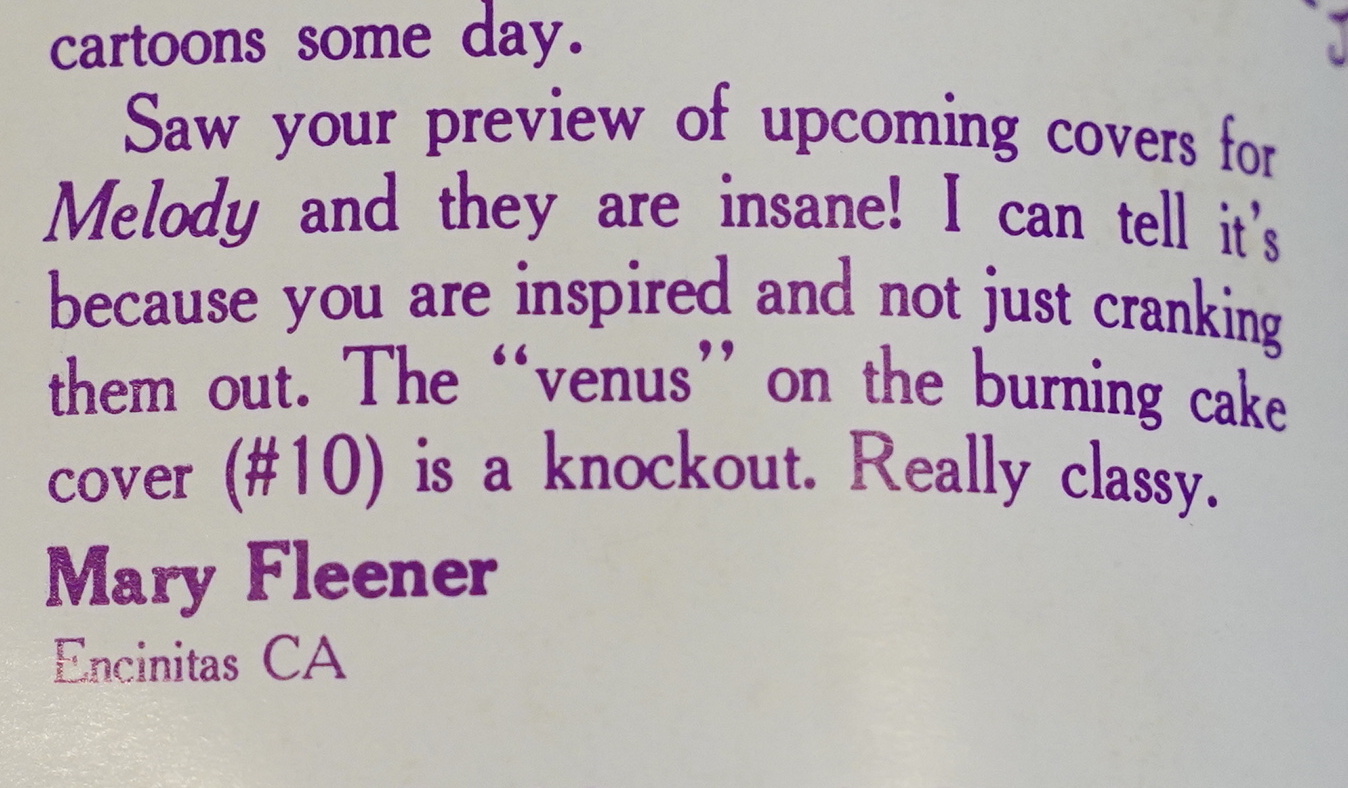

The pin-ups continue, with a very sexy drawing by Mary Fleener and a scary one from Dave Stevens.

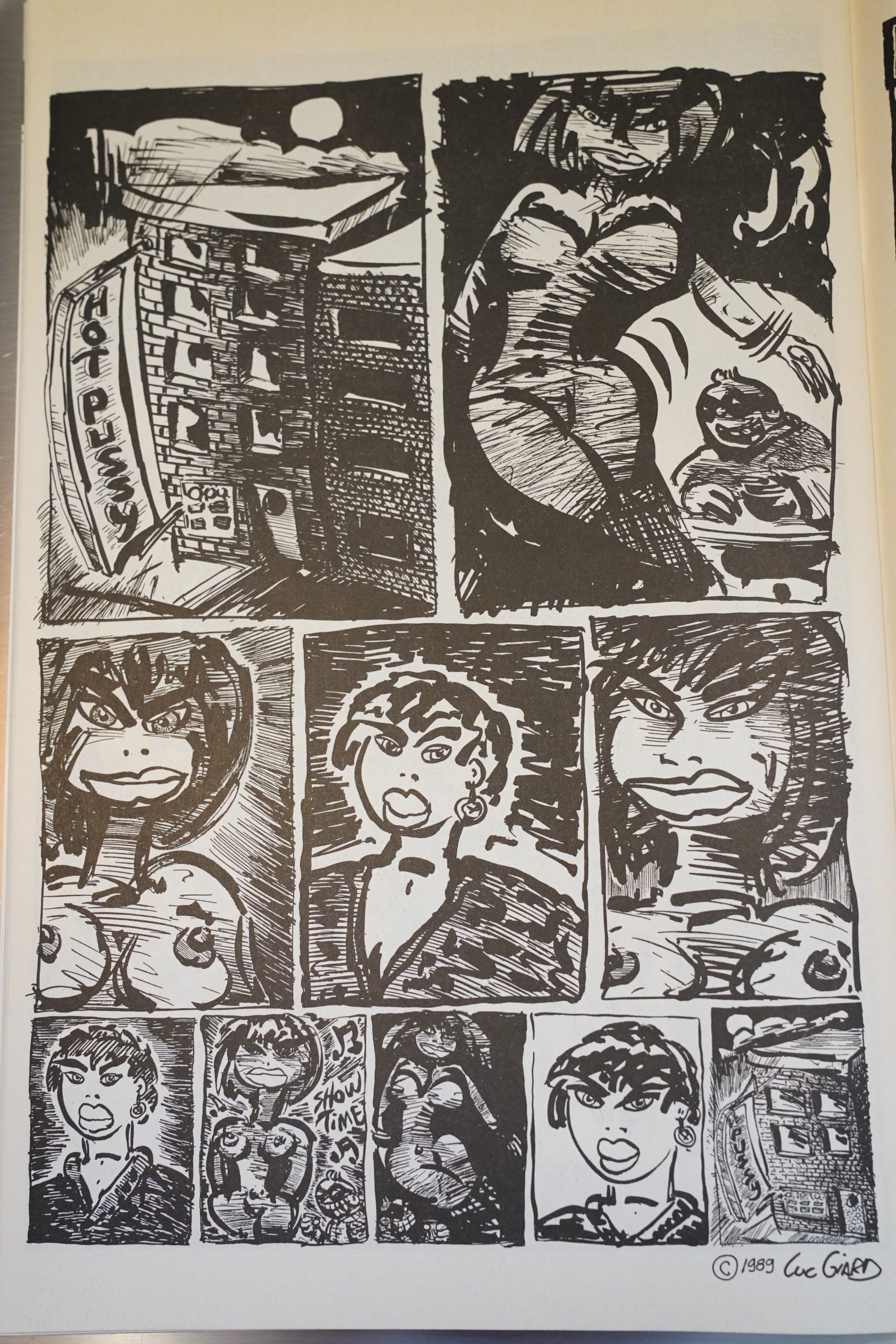

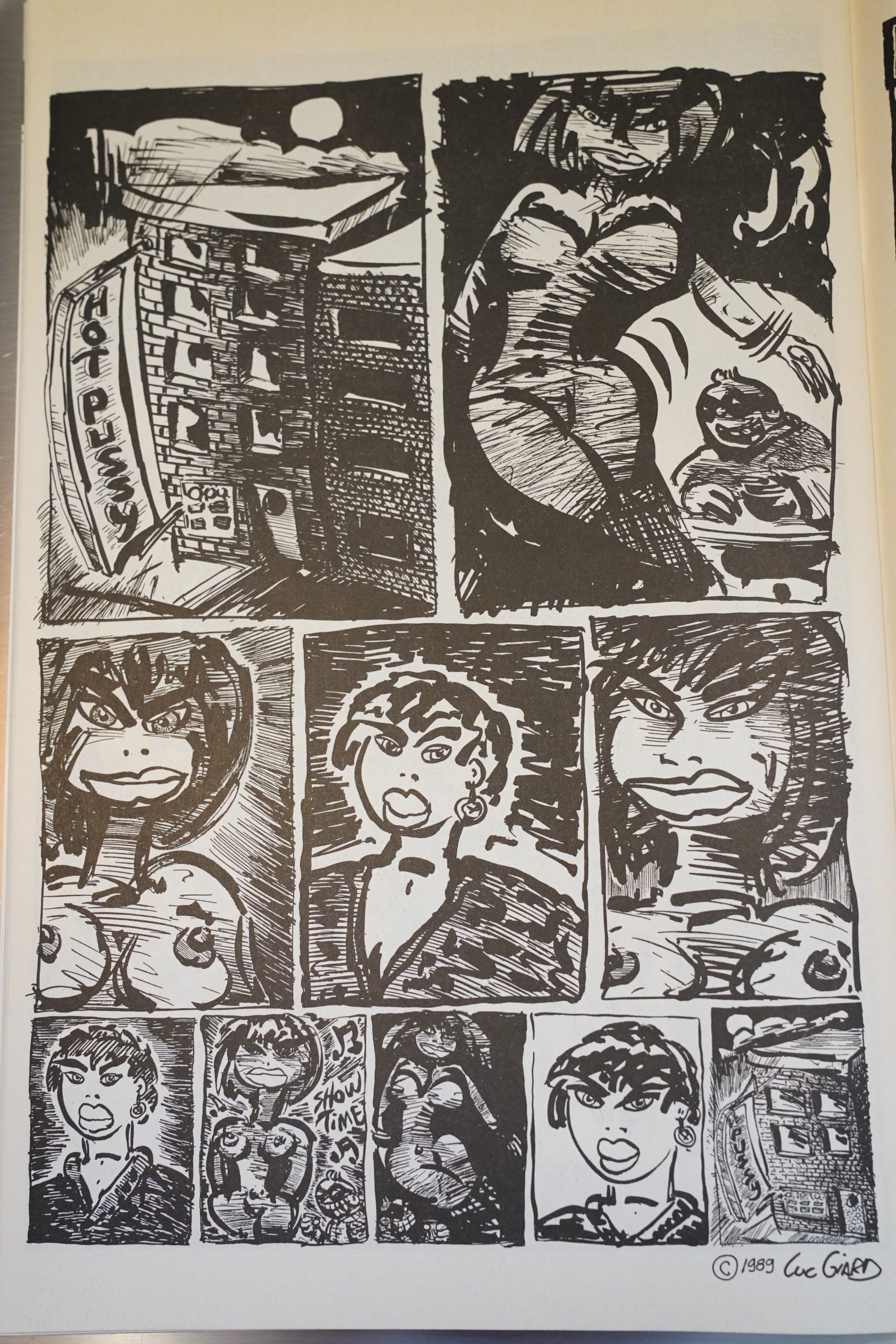

I love this one by Luc Giard.

But the most amazing pin up of them all is this one by Julie Doucet. She wins again.

The schedule starts slipping — we’re now down to about twice a year.

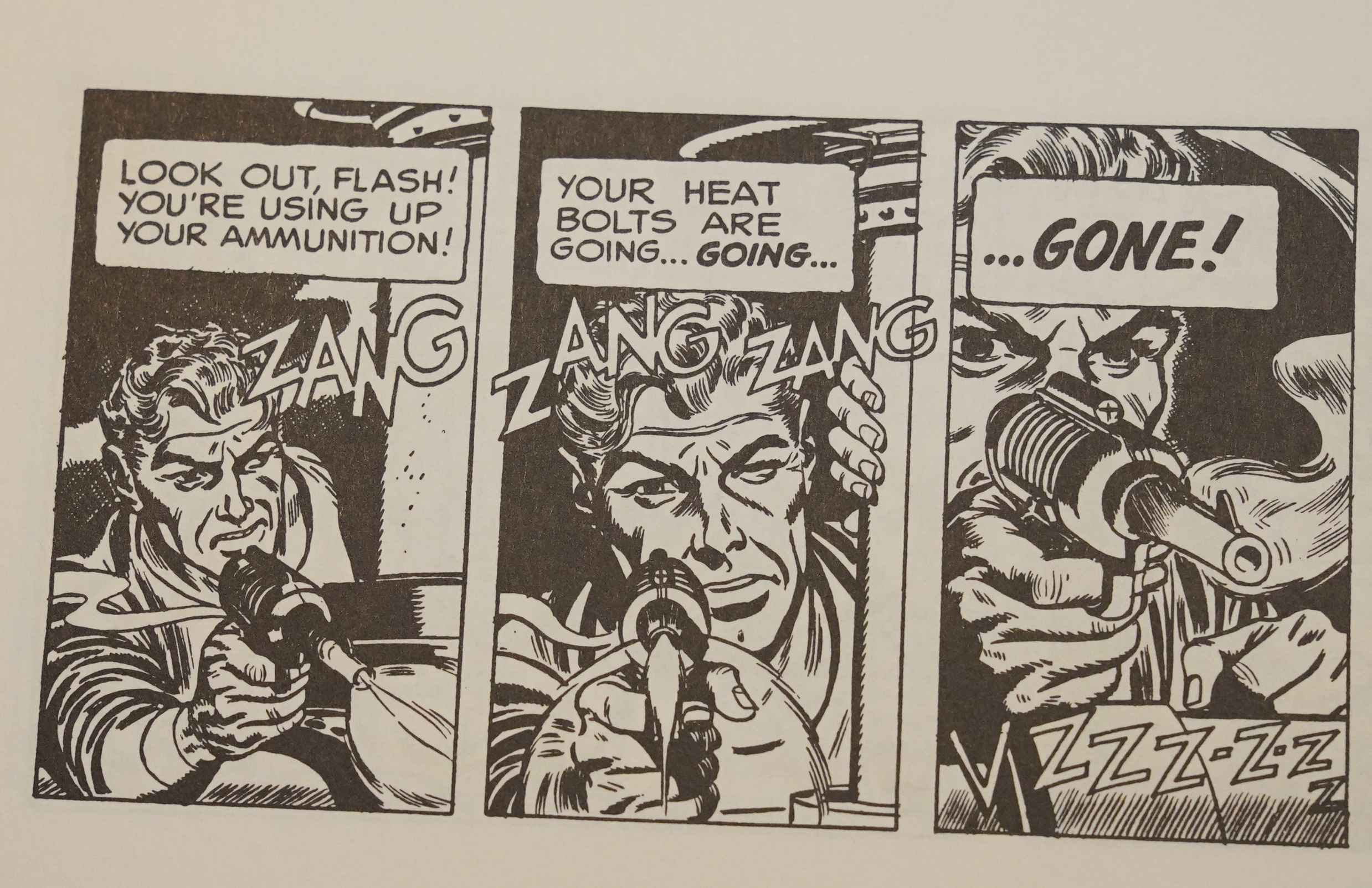

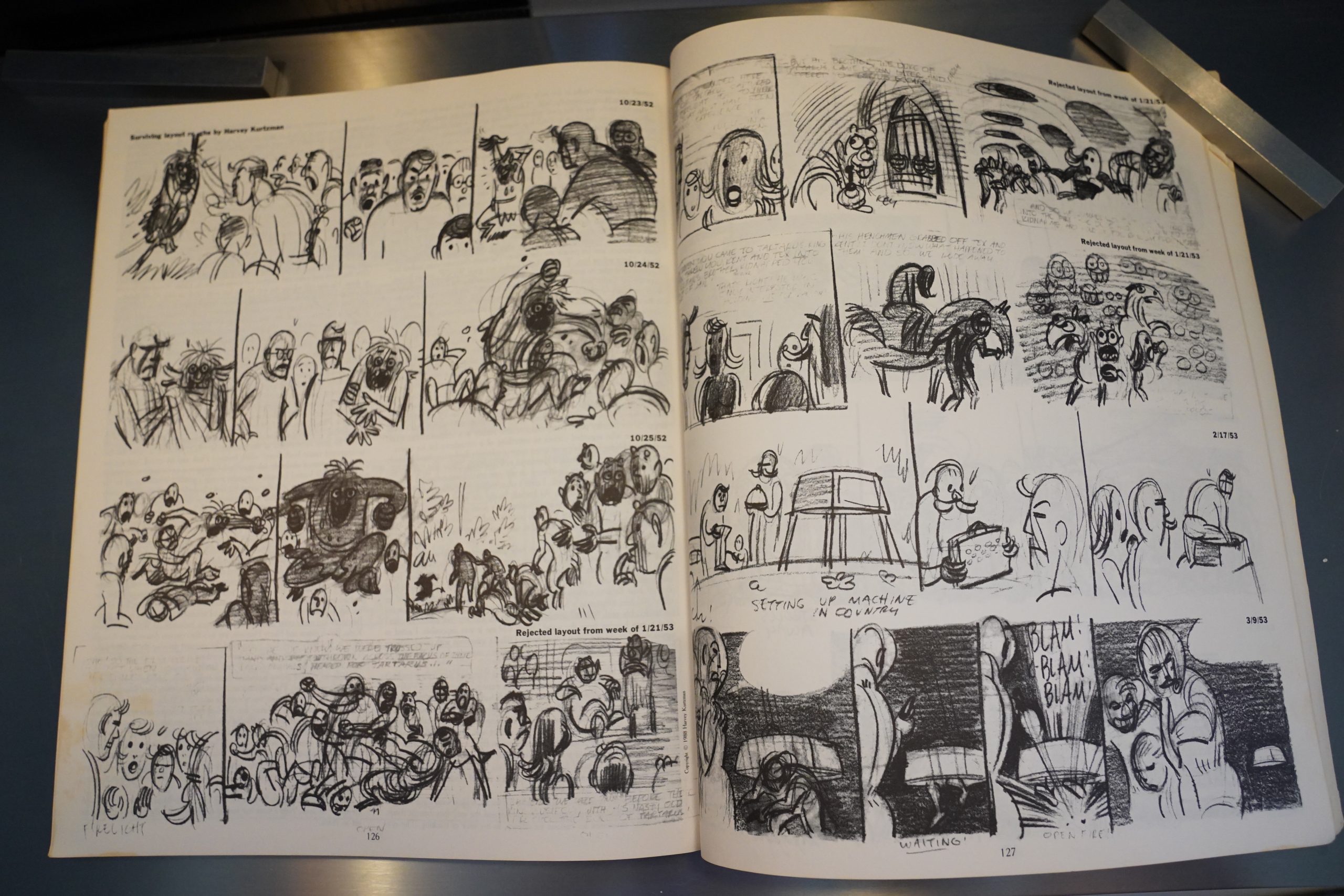

Perhaps this explains it — Morrissette is now doing most of the pencilling, and Boivin is doing most of the inking, but sometimes Morrissette does all of the artwork.

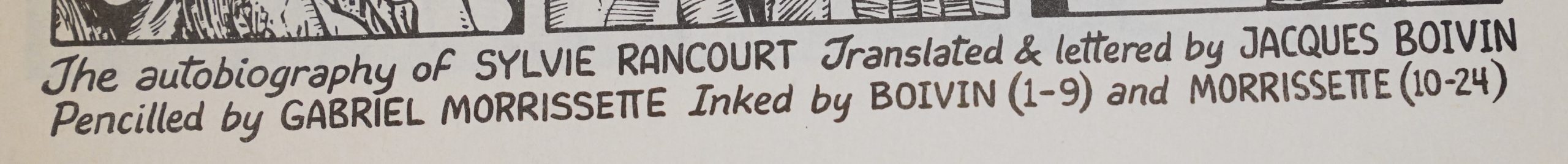

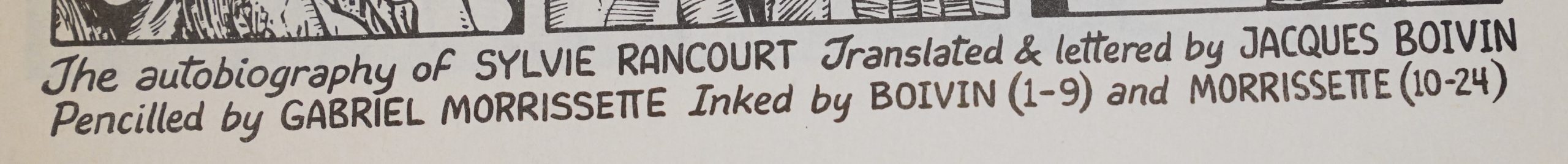

Oh, wow — is that Denis Kitchen’s original letter to Rancourt? It was reproduced to tiny that I couldn’t make it out on the page, but I’ve got the advanced technology to embiggen.

“Expect increased frequency in 1991.” That’s the traditional way alternative comics announce that they’re shutting down, but that’s not the case here:

There were no issues published in 1991, and we’re now basically on an annual schedule (and the page count drops to 24 for a couple issues).

This is how Melody moves from Abitibi to Montreal — she just has an epiphany, sells the contents of the house, and they leave.

I really enjoyed (re-)reading these issues now, but structurally, the book takes some odd detours, like this issue which is half about moving to Montreal, and half about various superstitions. Rancourt is dropping in things that… didn’t really need to be here?

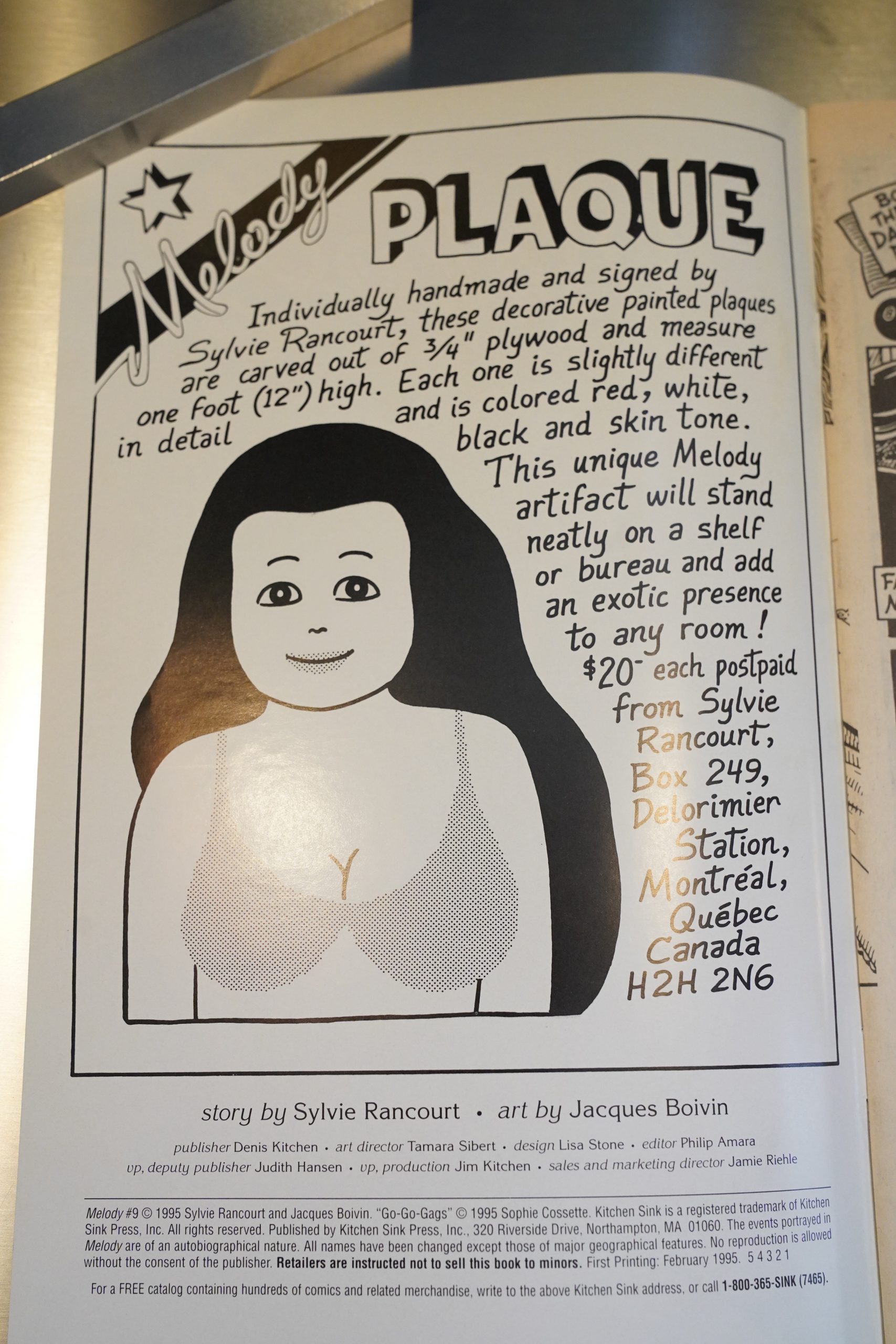

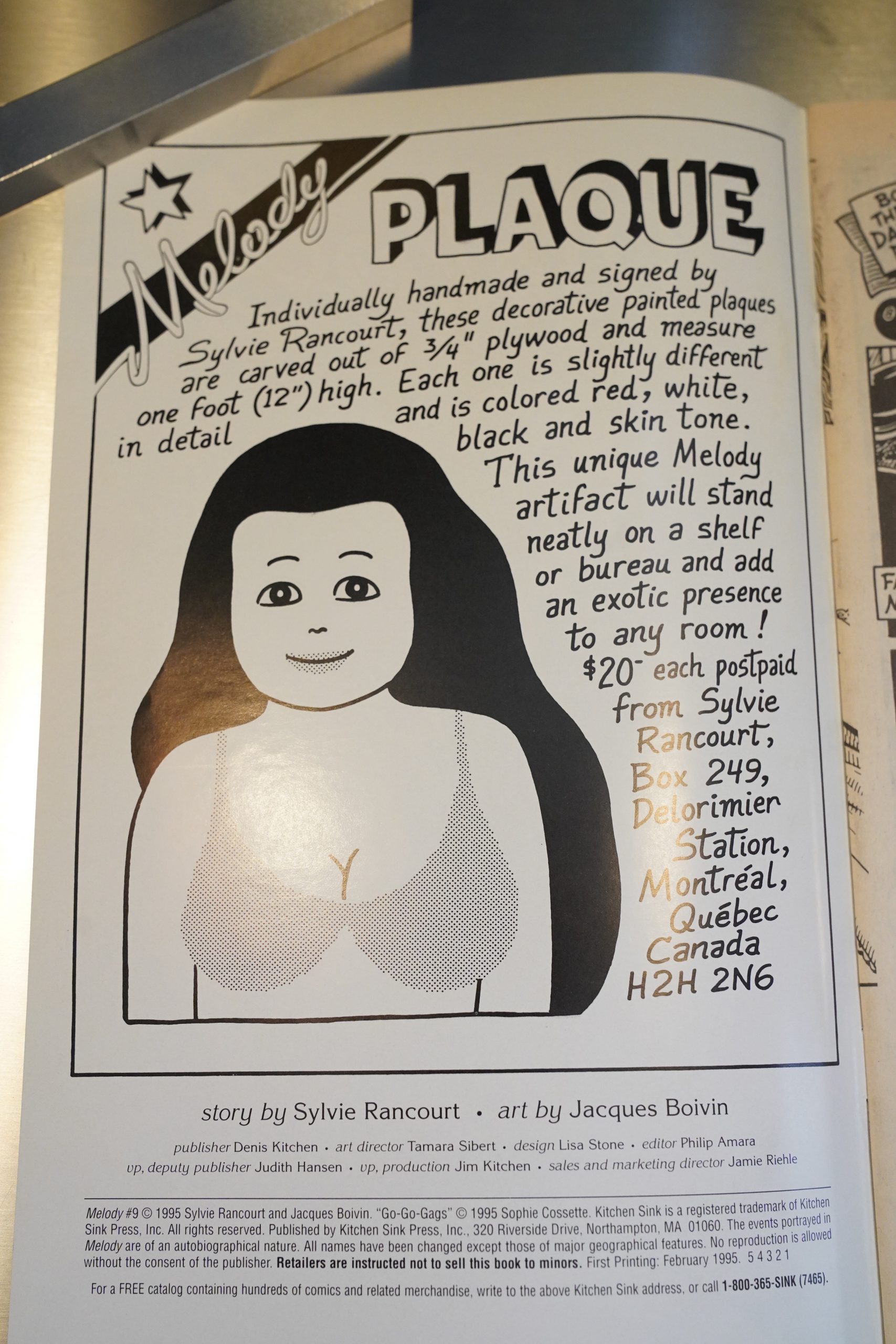

We’re now in 1995, and you could have bought one of those plaques back then.

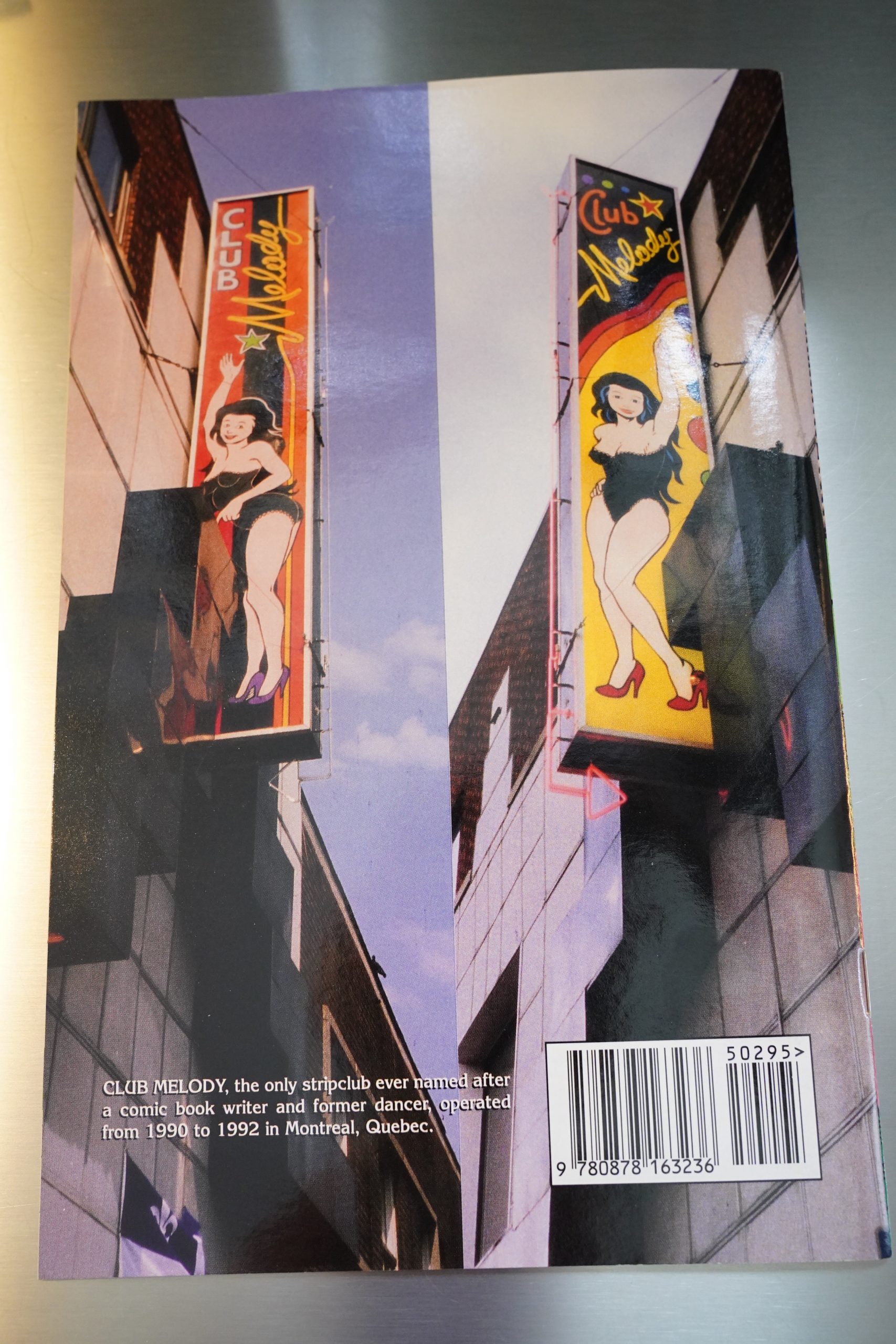

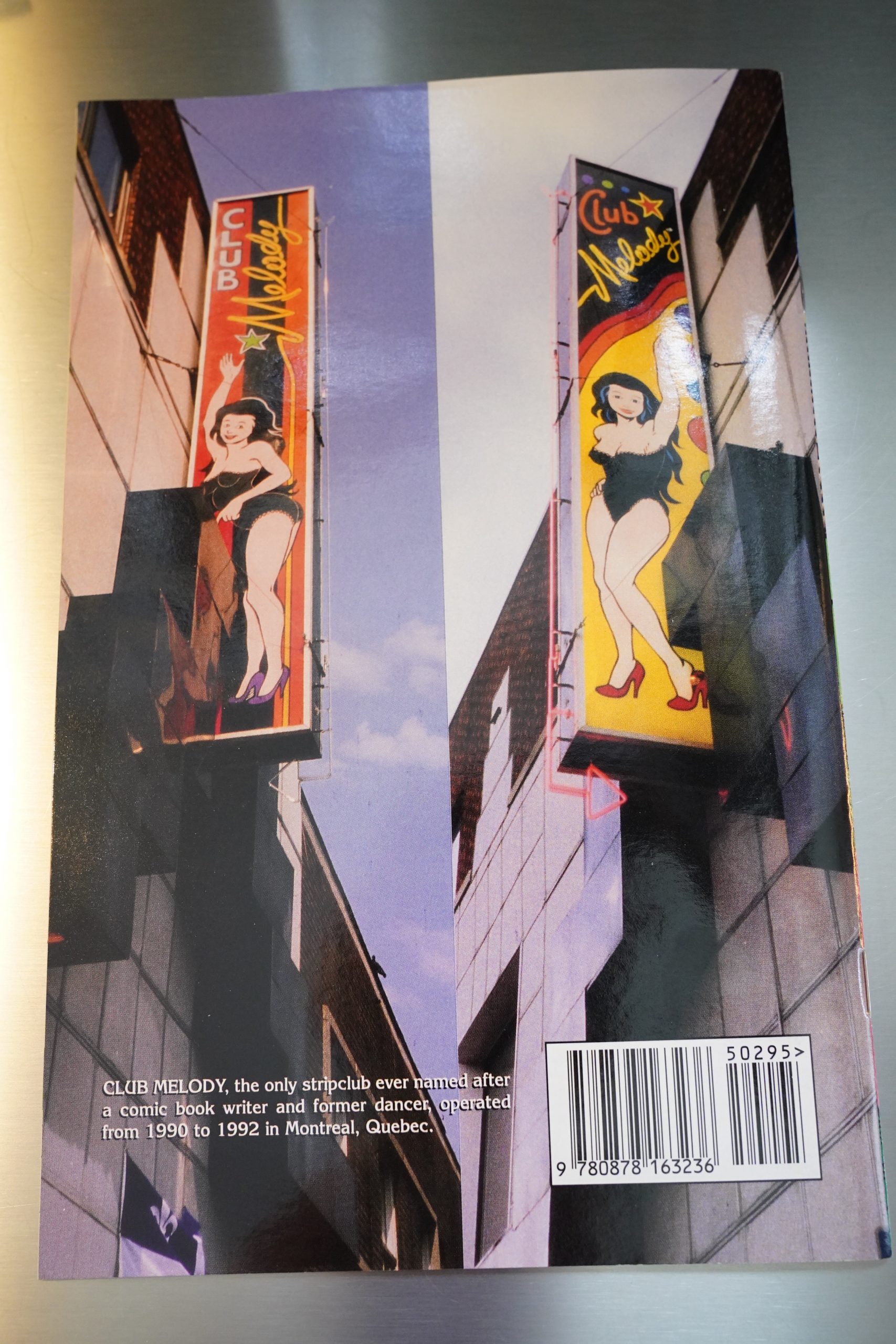

Or visited Club Melody in 1992.

Her husband is kind of a loser, eh?

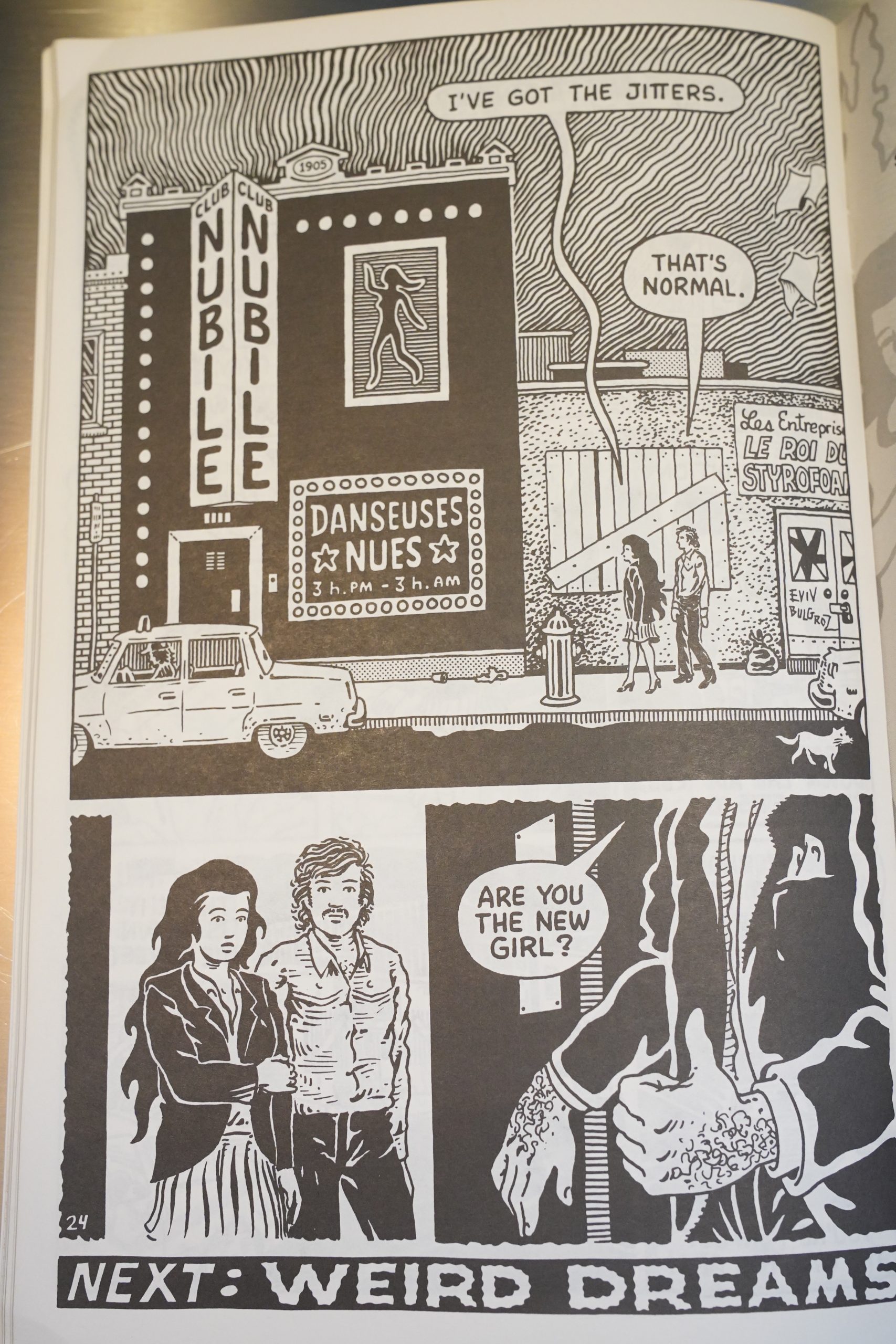

This is the final page in the series. And at least it has the traditional alternative comics final issue flair: A “next” tag line.

I have not been able to google why the book was cancelled. Kitchen Sink “bought” Tundra around this time (as far as I can tell, it was more of an aquihire situation where Tundra bought Kitchen Sink so that Denis Kitchen could take over running the Tundra tar pit), and many of the older Kitchen comics went the way of the dodo. But perhaps Rancourt and/or Boivin had just run out of steam.

It’s a shame, and it’s a shame that a collected edition of these comics still hasn’t been published… but I do understand why.

But in a way it’s fitting that the book ends here, before Melody becomes a nude dancer.

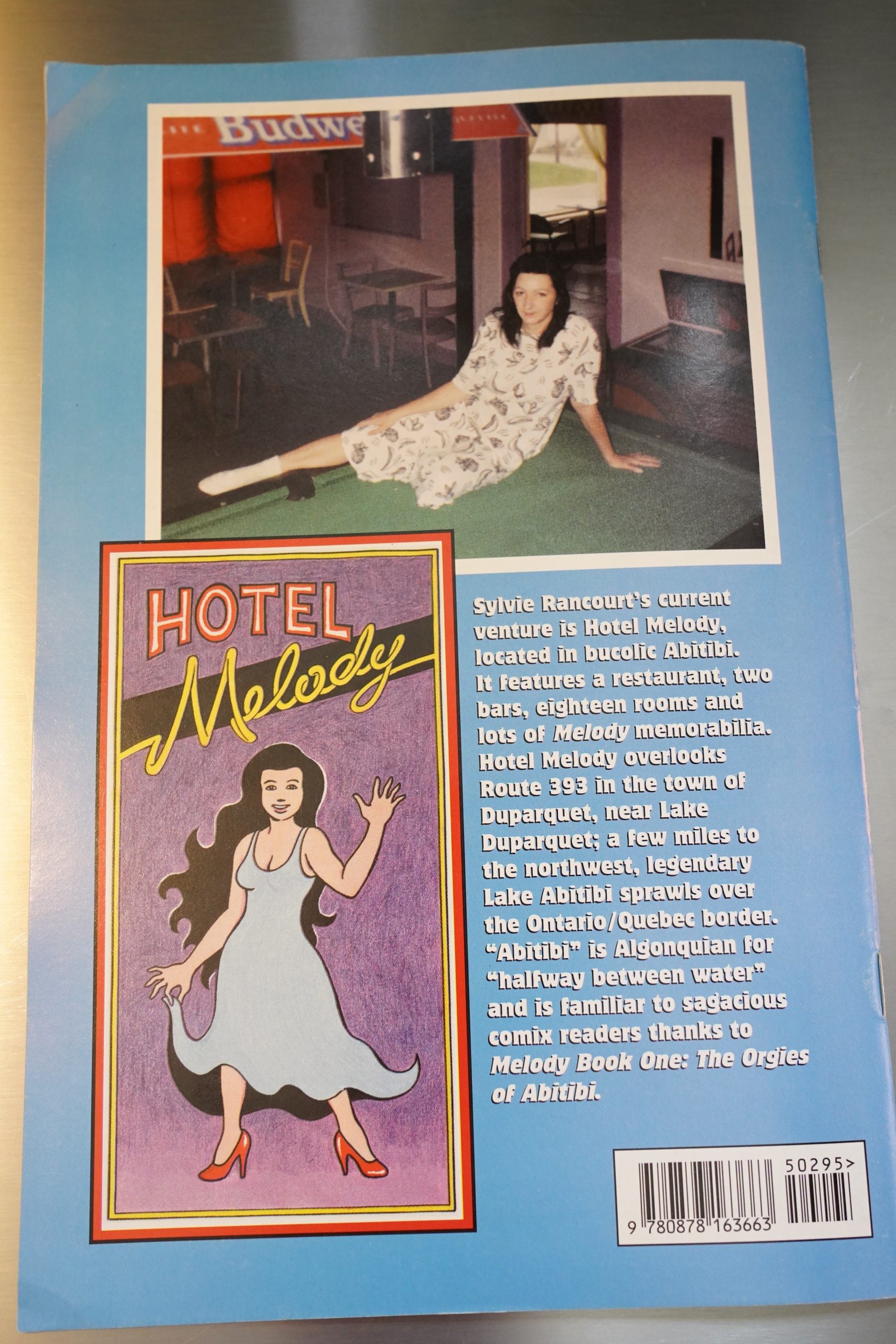

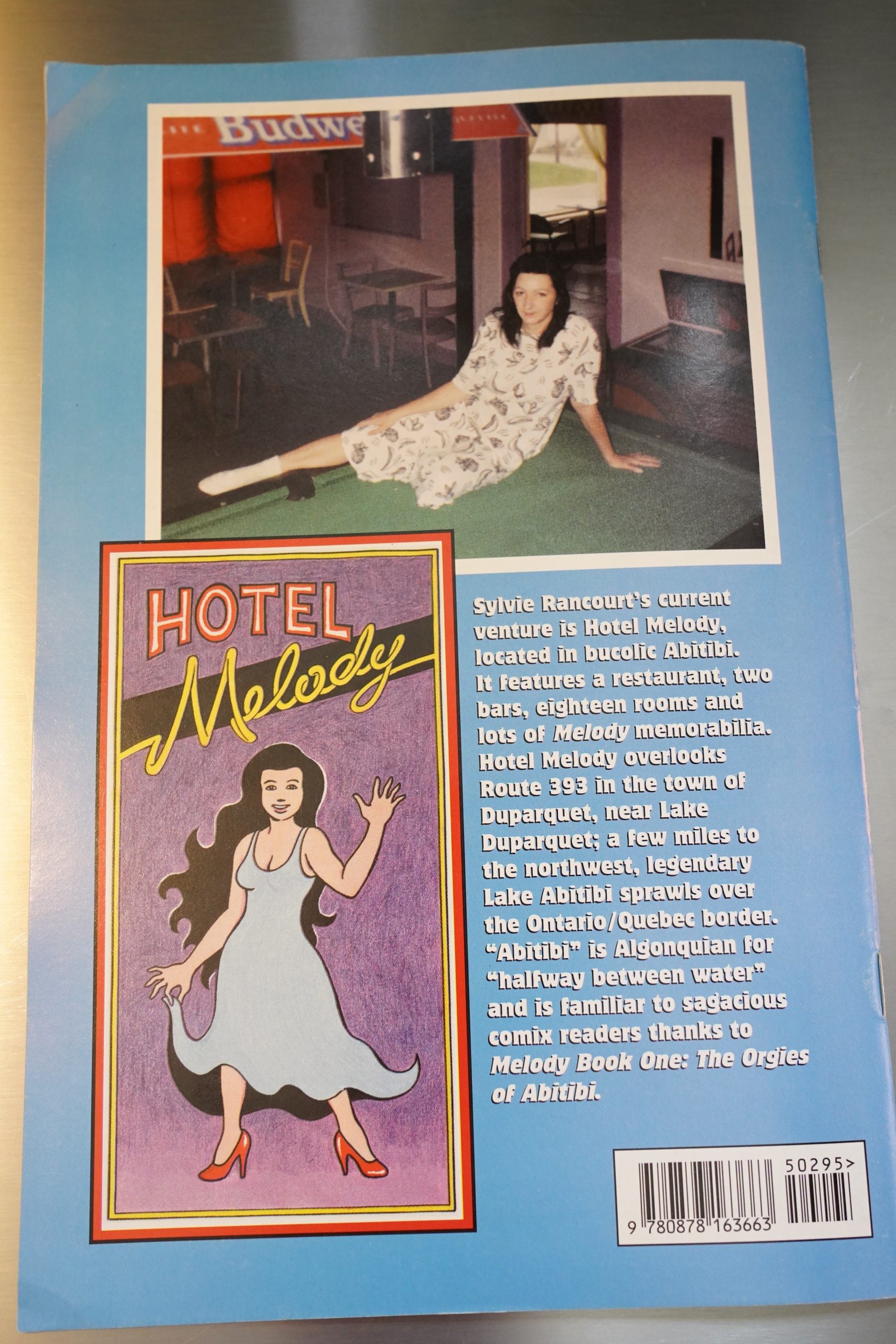

By 1995, Rancourt had apparently moved back to Abitibi and opened a hotel.

In 2015, Drawn & Quarterly finally published a translated collected version of Rancourt’s original comic, which has a storyline that almost starts on the heels of that final page up there. By the pacing of this series, I think we’d probably have half a dozen issues to go before we reached the start of the book?

It was well received:

“[Rancourt] is one of the pioneers of autobiographical comics . . . The republishing of this long-out-of-print and difficult-to-find saga . . . plunges the reader straight into a profoundly sensitive work that no moral judgment could taint.” —Le Monde

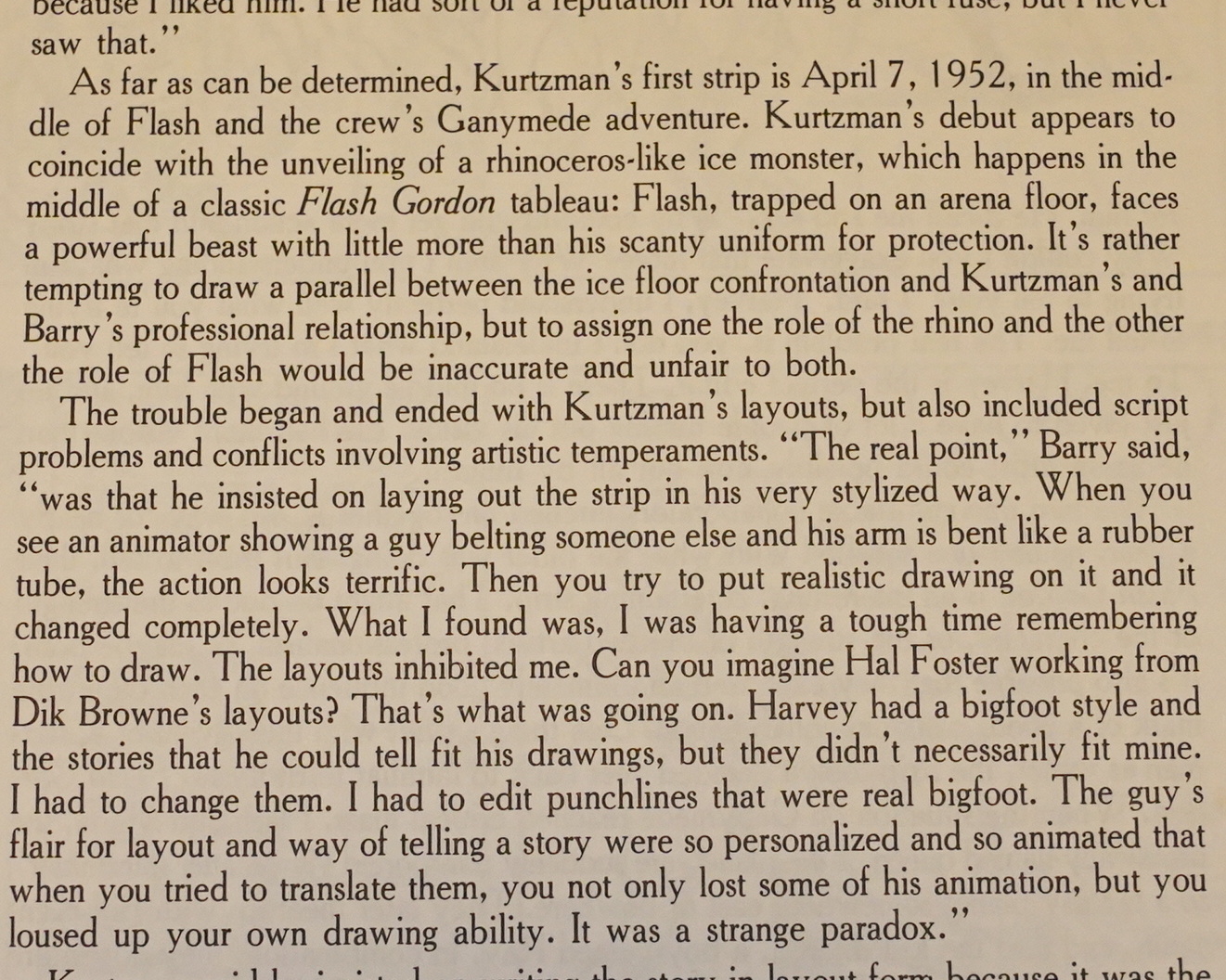

Heidi MacDonald writes in Amazing Heroes #151, page 59:

Melody (Kitchen Sink) is, as you’ve

probably heard, a new entry in the

field of tell-all autobiographical

comics, written by Sylvie Rancourt,

visualized by Jacques Boivin, and

based on Rancourt’s real-life adven-

tures. Publisher Denis Kitchen points

out that it is probably the first such

comic to be done from a woman’s

point of view, but it’s not a point of

view that most women would

recognize—Melody is a nude dancer

in the Montreal red light district.

You could peg this as a cross bet-

ween Omaha and American Splendor

and it is—but it’s also an unapologetic

look at the way people really

behave—not the way they pretend to.

In issue #1 we meet Melody and her

husband, Nick, living on welfare in

some god-forsaken tract of Quebec,

raising chickens and complaining

about eating a lot of chicken. Nick

squanders most of his welfare check

at nude bars. For a good time, they

invite a few close friends over for

evenings of Monopoly and group sex.

It may sound pretty sordid, and

some of it is, but like Omaha, Melody

deals with sexuality as just another

perfectly normal part of human

nature. In fact, the most sensa-

tionalistic elements often seem the

most mundane. Melody herself is so

straightforward that it’s totally dis-

arming. This openness is carried over

to her storytelling, which is utterly

natural and unforced.

The book has a rather convoluted

history—it originated as a French-

Canadian mini-comic written and

drawn entirely by Rancourt, but is

appearing in a version translated and

redrawn by Boivin. I’ve been a fan of

Boivin’s •charming artwork for several

years and it’s nice to see him get an

opportunity to work on a worthwhile

project. His art is, of course, far

slicker than Rancourt’s completely

naive style, and I think it uould be fair

to say that you can tell a guy drew the

book. There’s a kind of obsessive

quality to the original that is missing

in this far more accessible version—

however, Boivin’s efforts here

shouldn’t be overlooked.

This is the one hundredth post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.