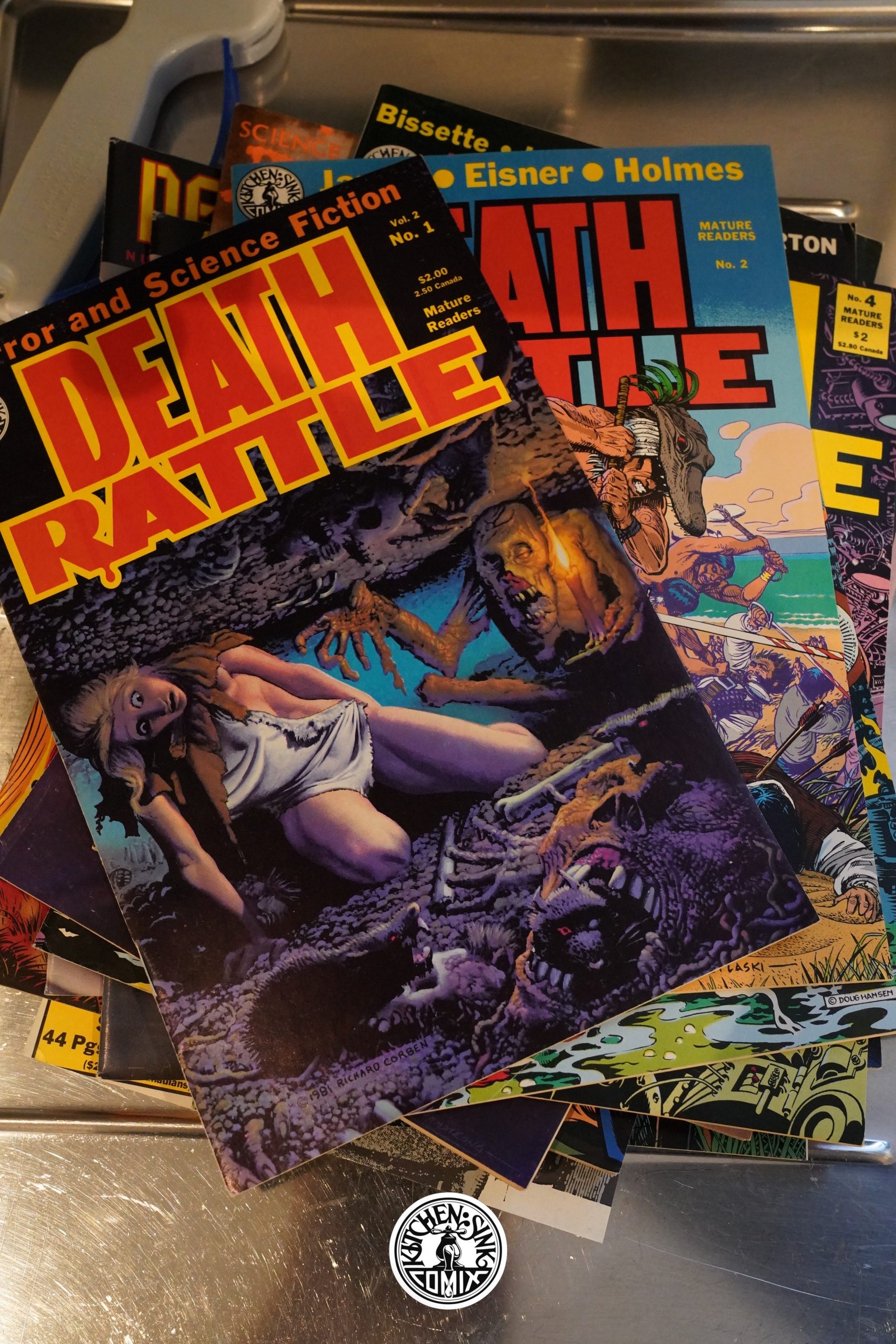

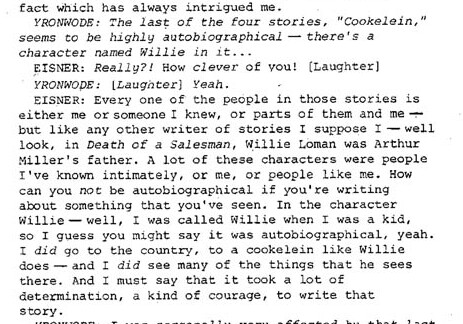

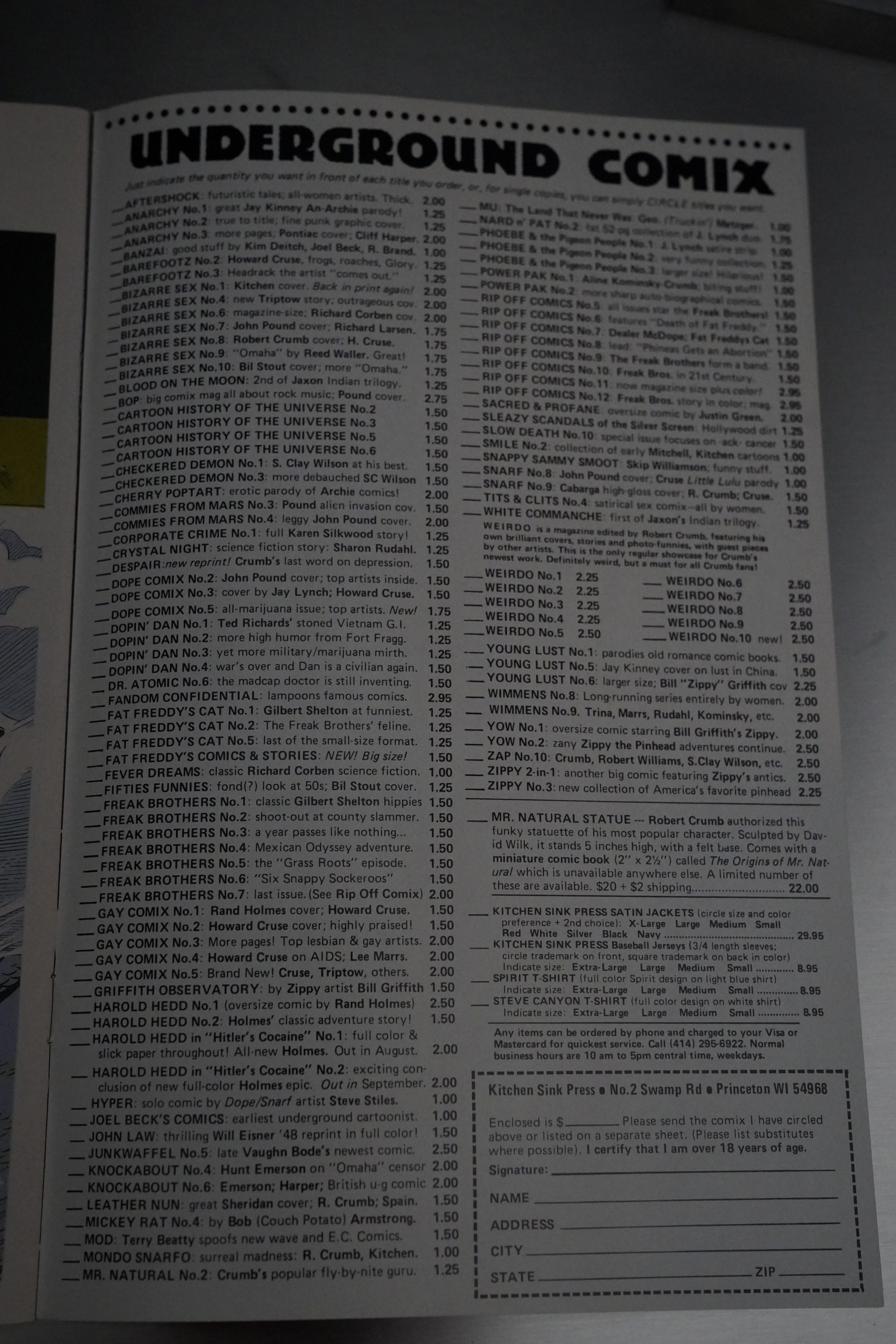

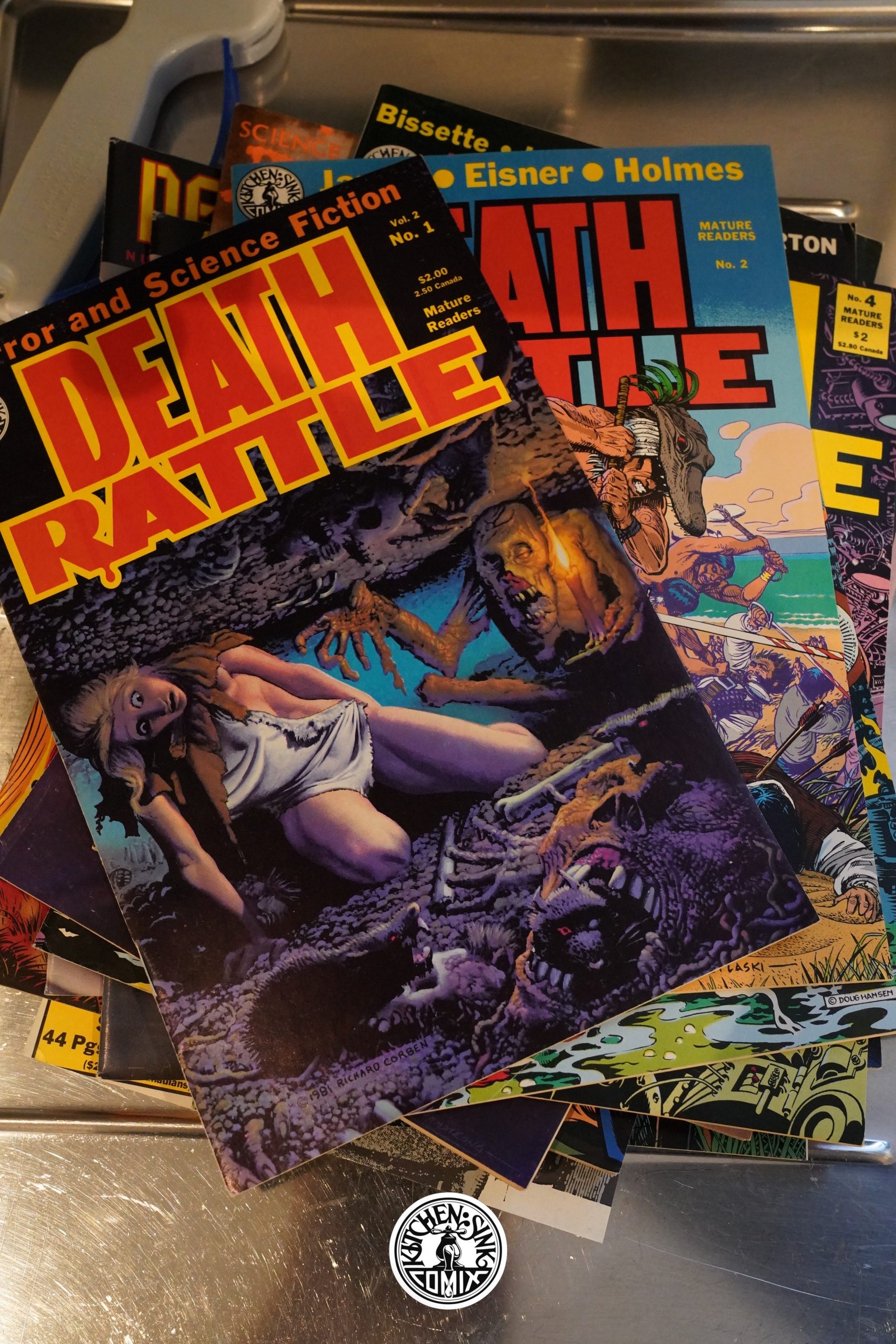

Death Rattle (1985) #1-18 edited by Denis Kitchen and Dave Schreiner

The 32 page anthology format is a difficult one to pull off. With a higher page count, you can achieve a nice mix of longer and shorter stories, and if you include one story that doesn’t quite work, it’s no big deal. And you can have a roster of familiar faces as well as dropping in surprises now and then. With a 32 page anthology, everything becomes harder — if you have a long story, it ends up totally dominating the issue. If you only run shorter stories, it gets samey after a while. If you use the same artists every issue, it gets boring. If you don’t have any recurring artists, the anthology can become schizophrenic.

But there were other successful 32 page anthologies around at the time — perhaps most notably Twisted Tales (published by Pacific). However, they solved all these issues by having most of the stories being written by Bruce Jones.

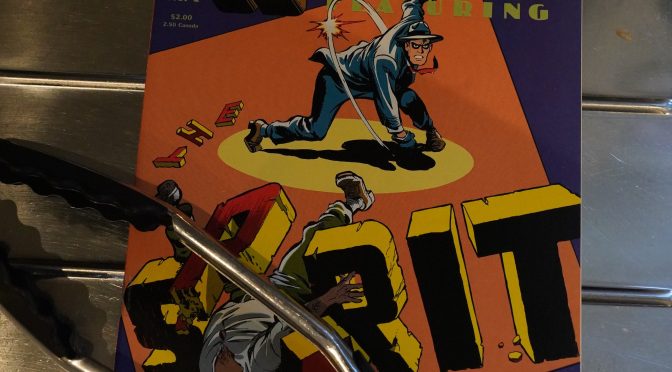

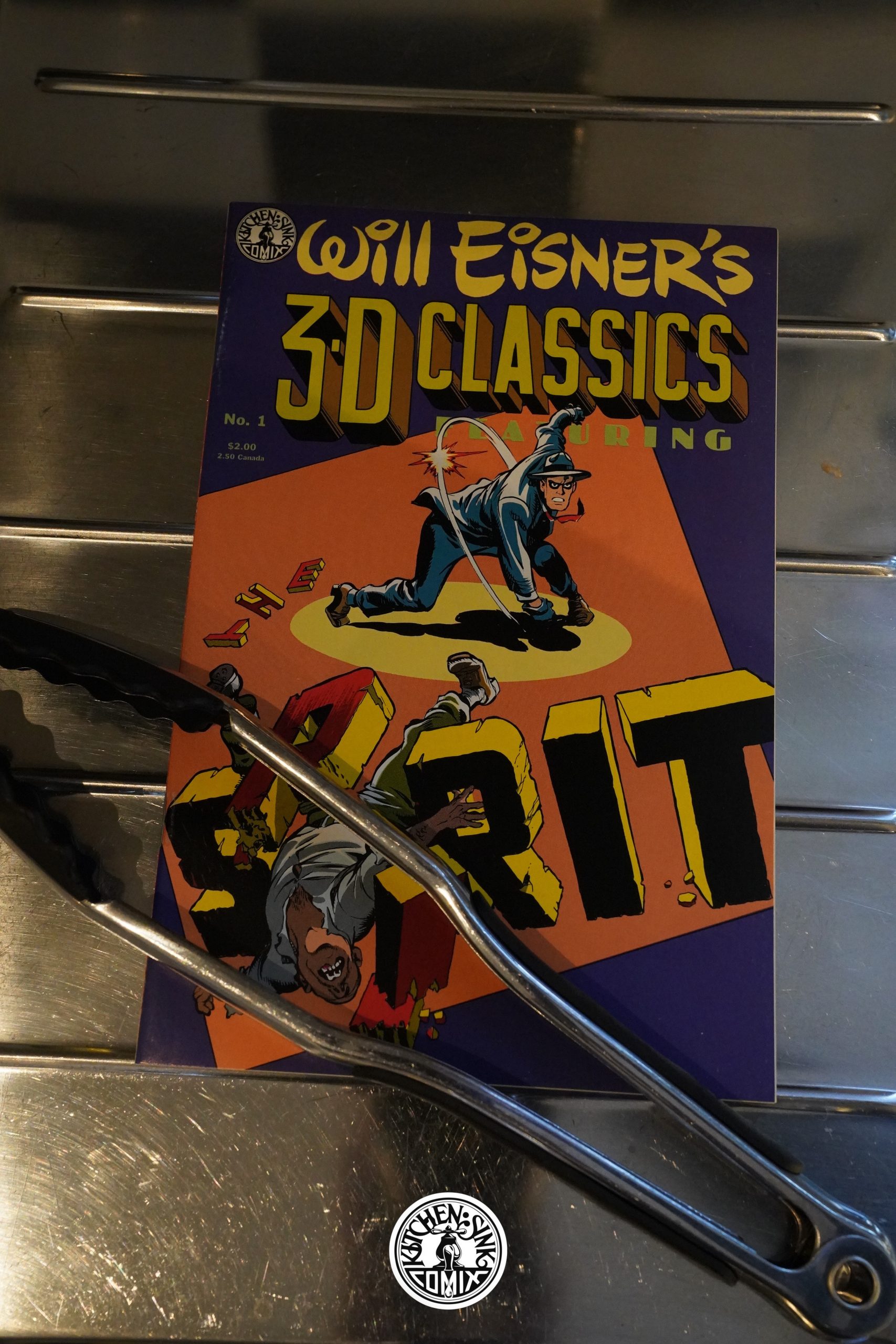

Kitchen Sink had a go at the Death Rattle title in 1972, and it was pretty horrific. I mean, not scary, but just really bad. So it’s slightly odd that they re-used the same title for their horror anthology in 1985 — but it’s a good title. And they managed to publish 18 issues before it was shut down (which is pretty unique), so it sounds like it sold well, and perhaps it’s really good?

I certainly thought so as a teenager: I bought (almost) the entire series at the time, and I remember reading and re-reading them — at least the early issues. So I’m excited to re-read them now: Do I remember correctly, and these are really good, or do they suck? Let’s find out!

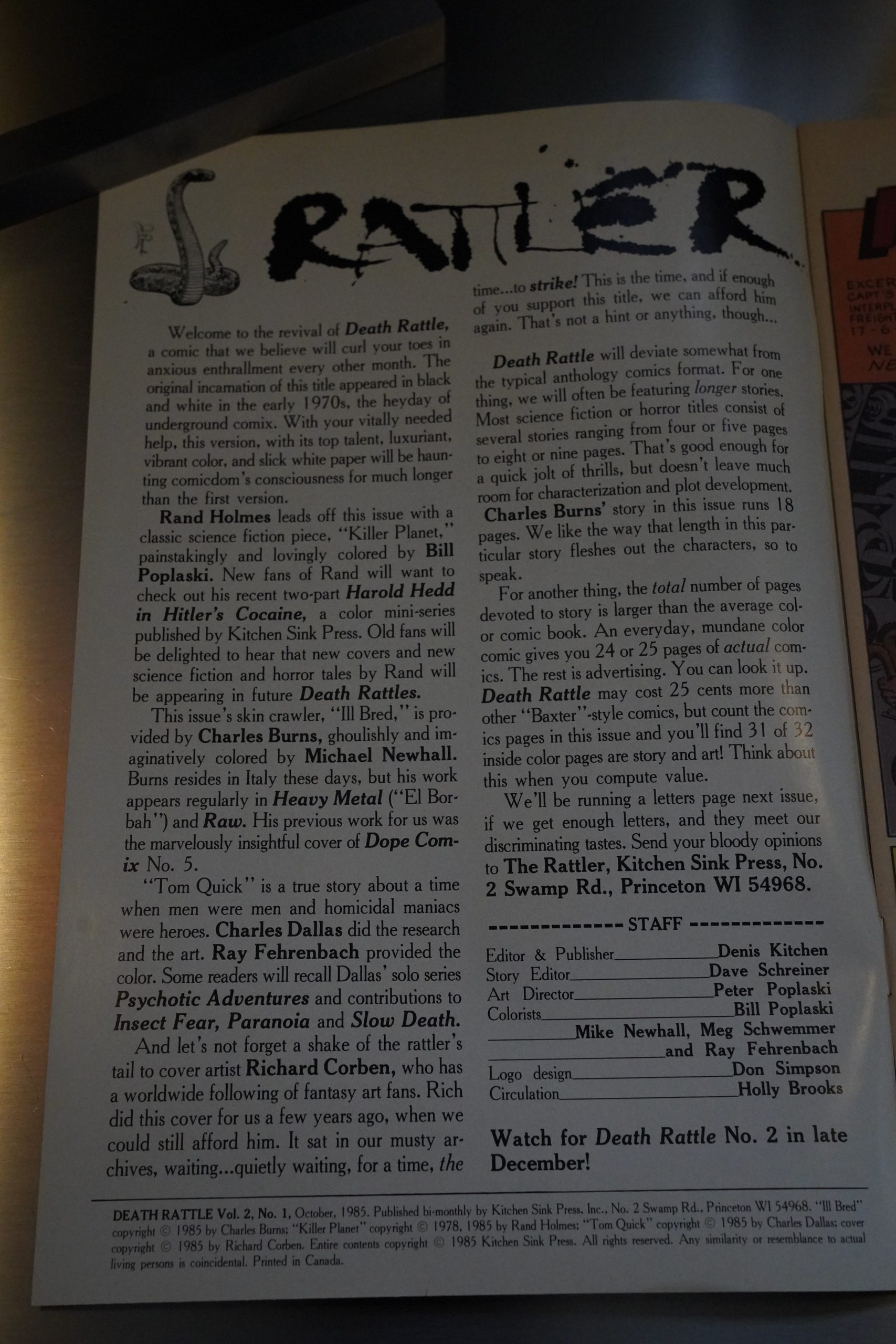

Kitchen Sink’s previous anthologies have had a tendency to be… er… sloppily put together? In an interview in the 70s, Kitchen described how he’d be buying work over a long period of time, and then, when he has enough for an issue, he’d put an anthology together. Which explains why so many of Kitchen’s 70s anthologies were so incoherent, and didn’t really have much of an identity (even if individual stories in the anthologies were great).

Here he’s also insisting that there’ll be no ads, and that explains the (for the time) high price of the book (comics fans are notoriously cheap). And that also makes me go “right, as opposed to the earlier anthologies”, which were padded in all kinds of ways.

I’m not being grouchy or anything! I’m just wondering whether this is another one of Kitchen’s assembled-from-a-forgotten-drawer anthologies, or whether it’s… like… been edited.

So, on the inside front cover he mentions that the Corben cover is older work that he’d had lying around for a while. But nothing about the rest of the work.

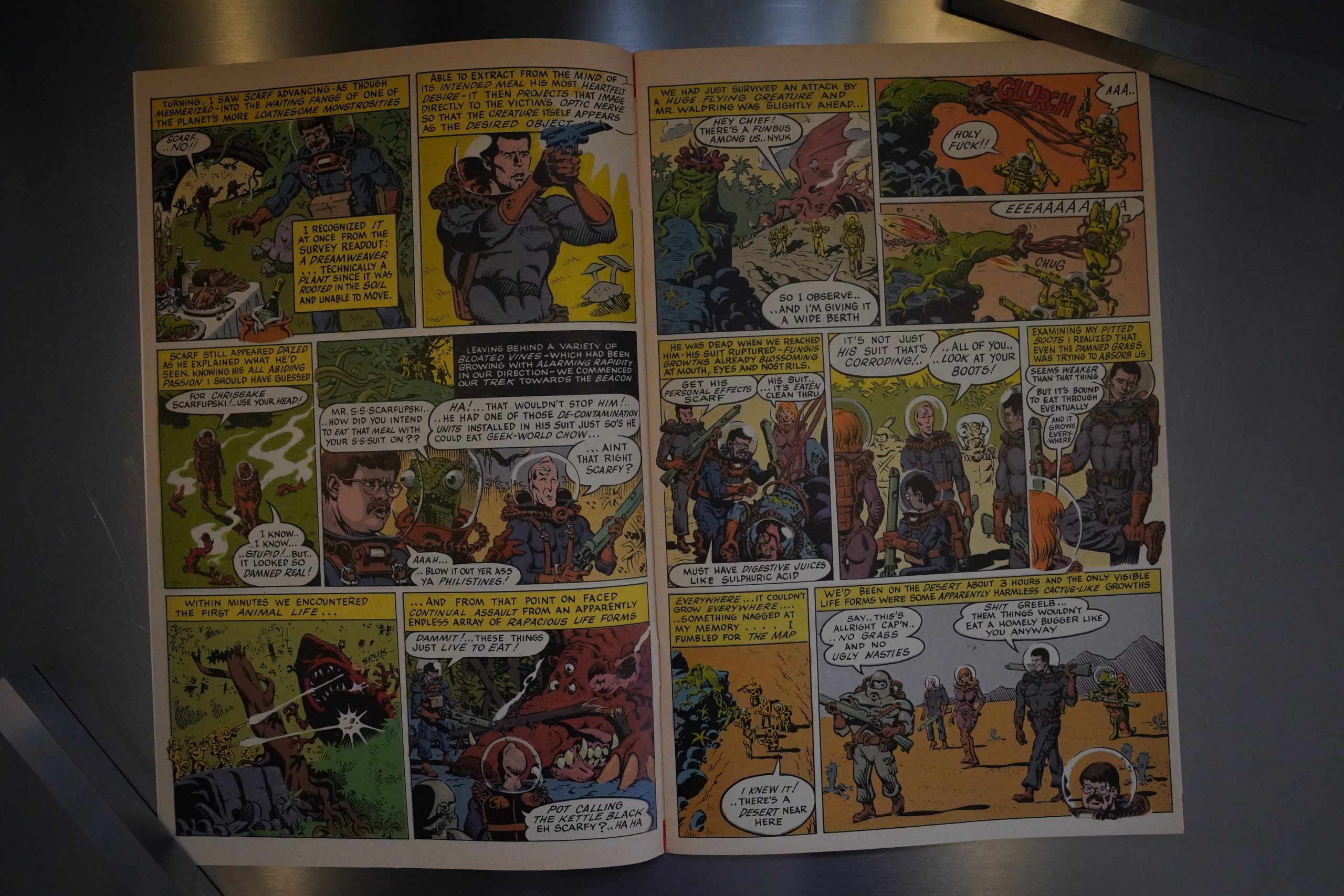

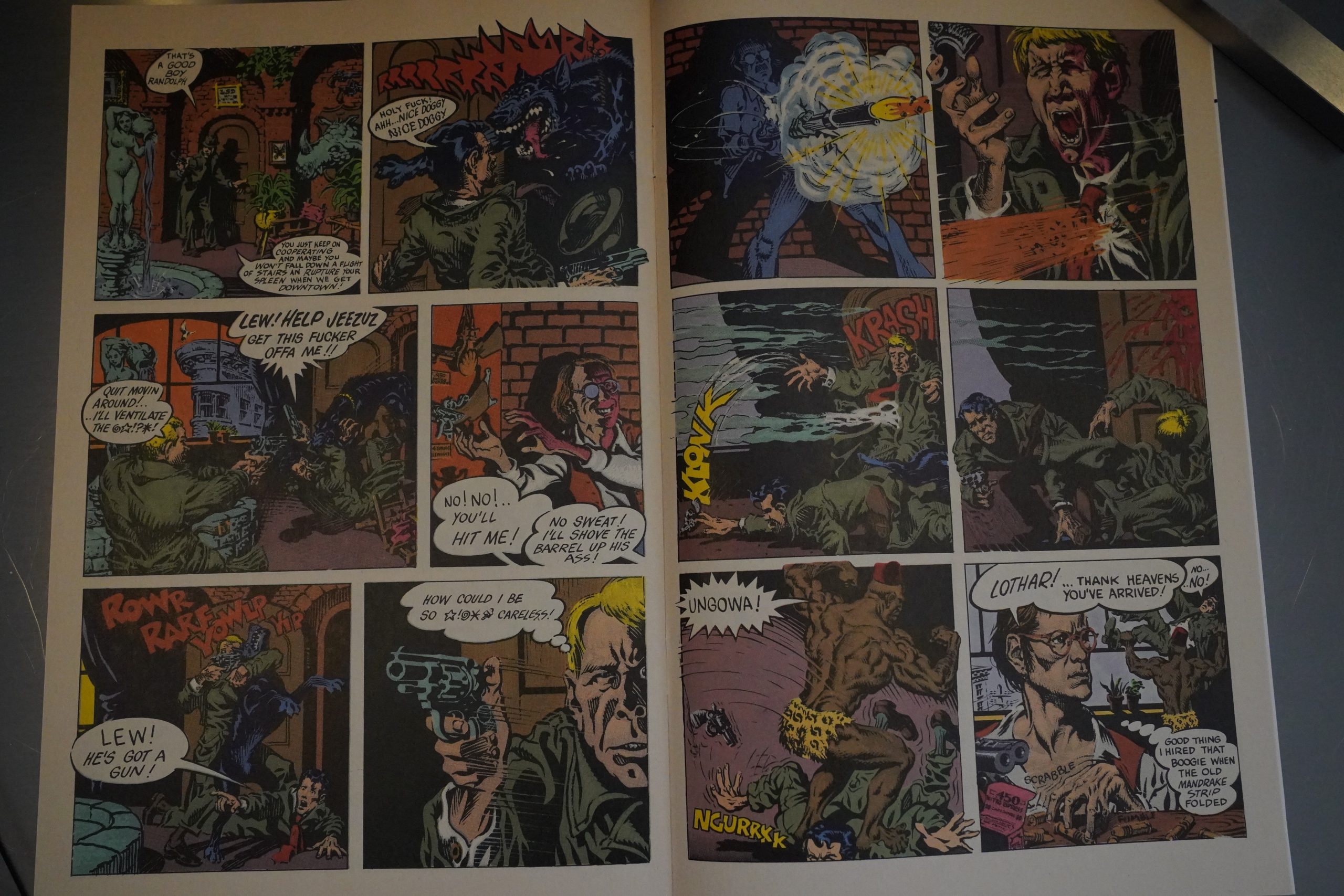

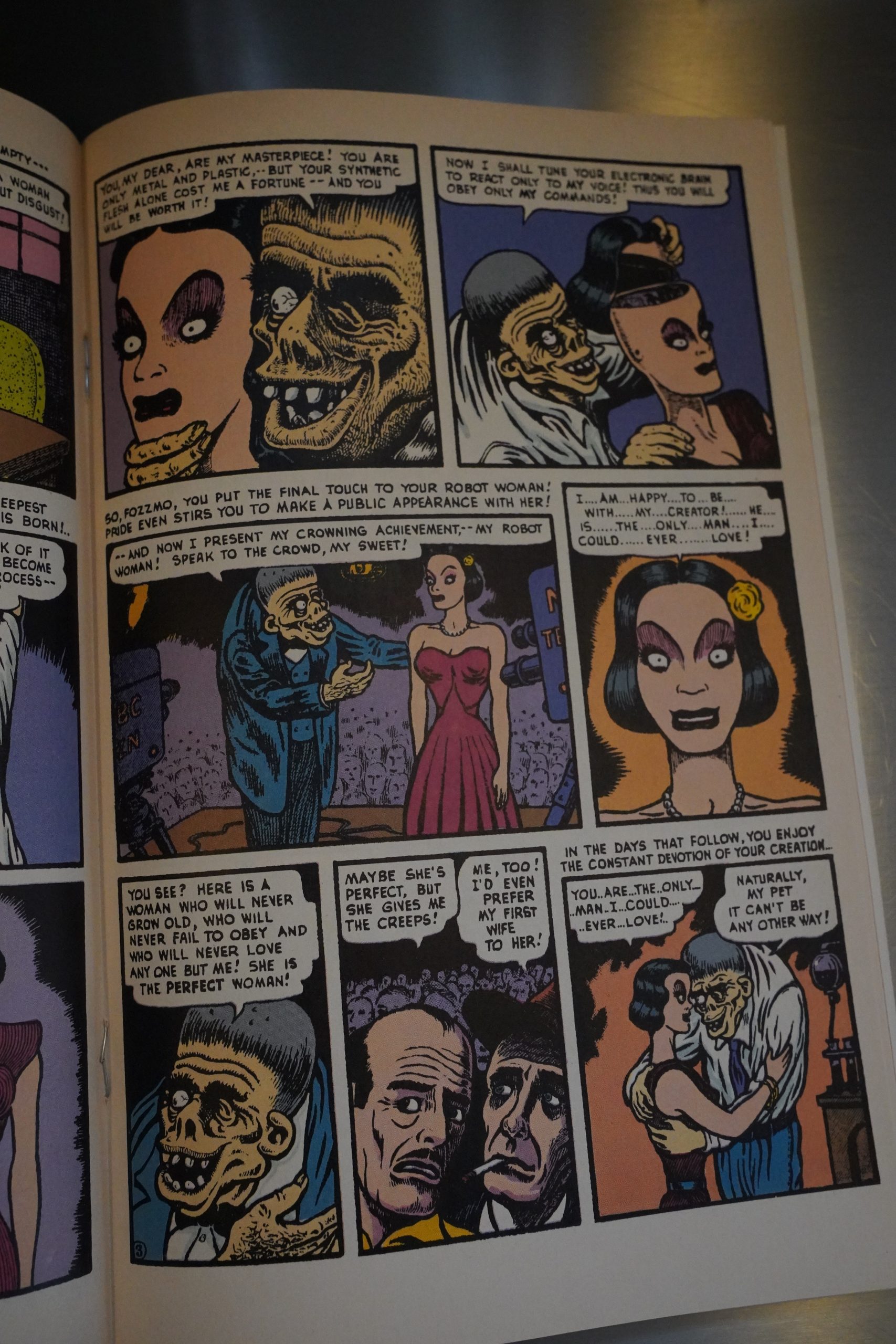

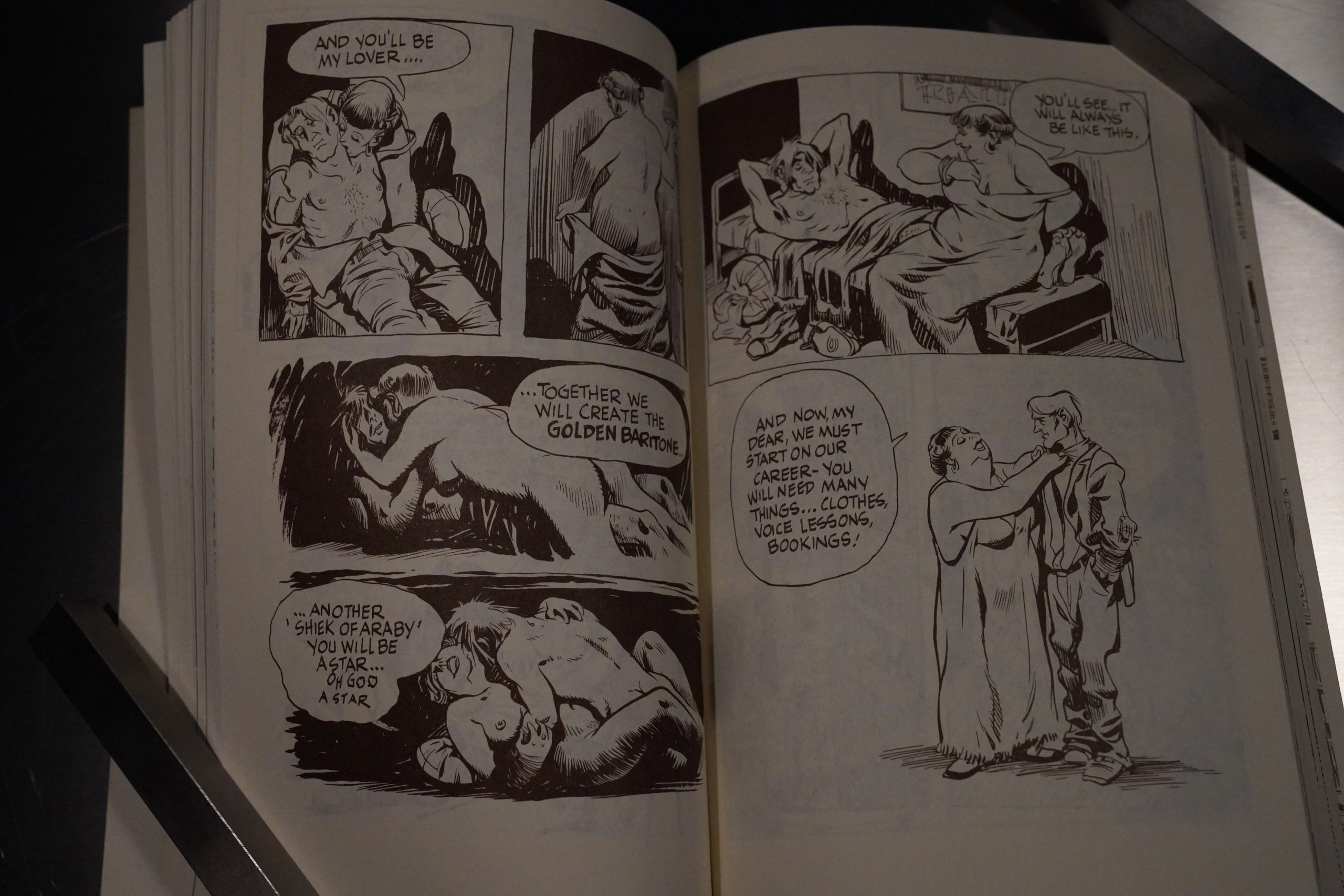

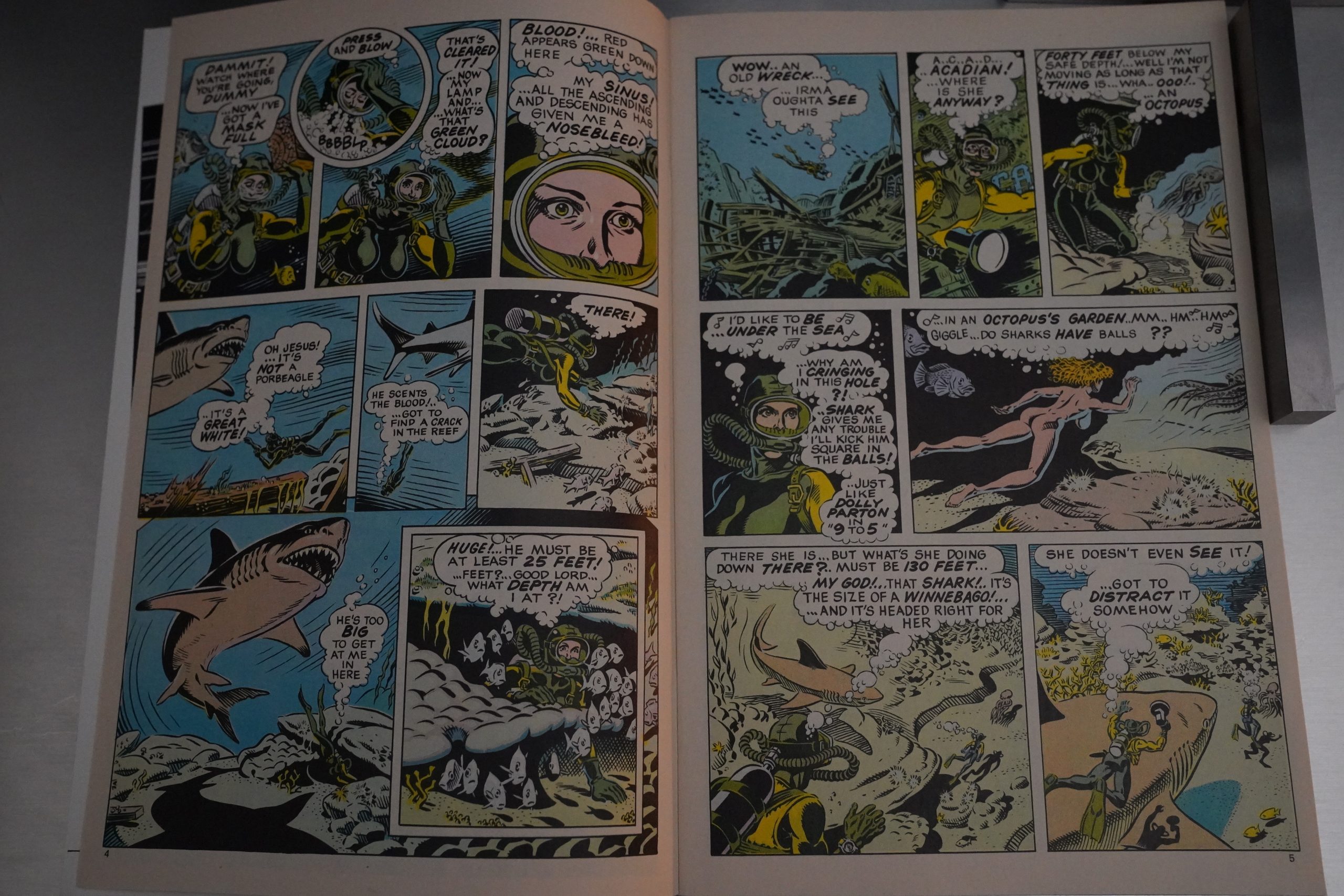

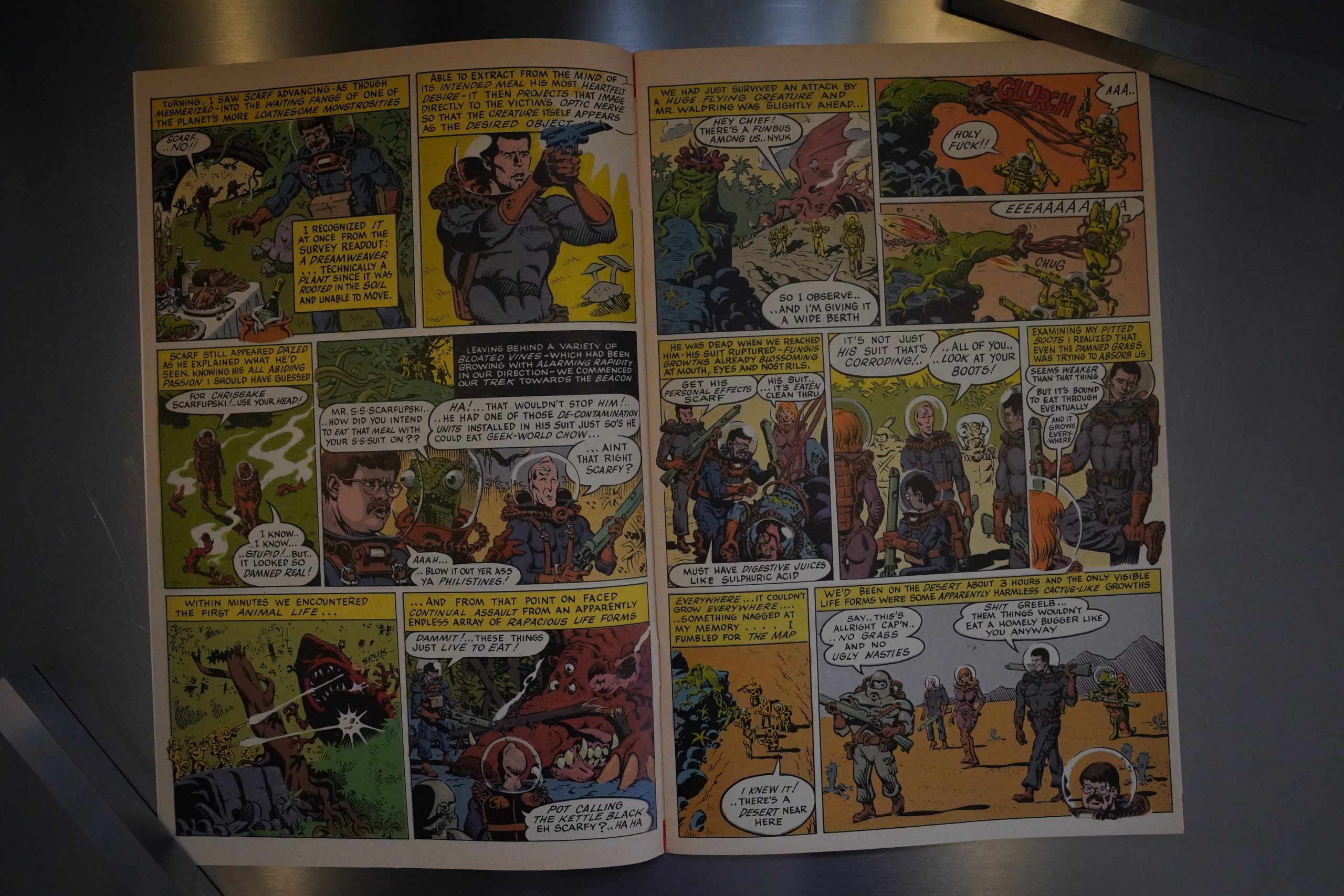

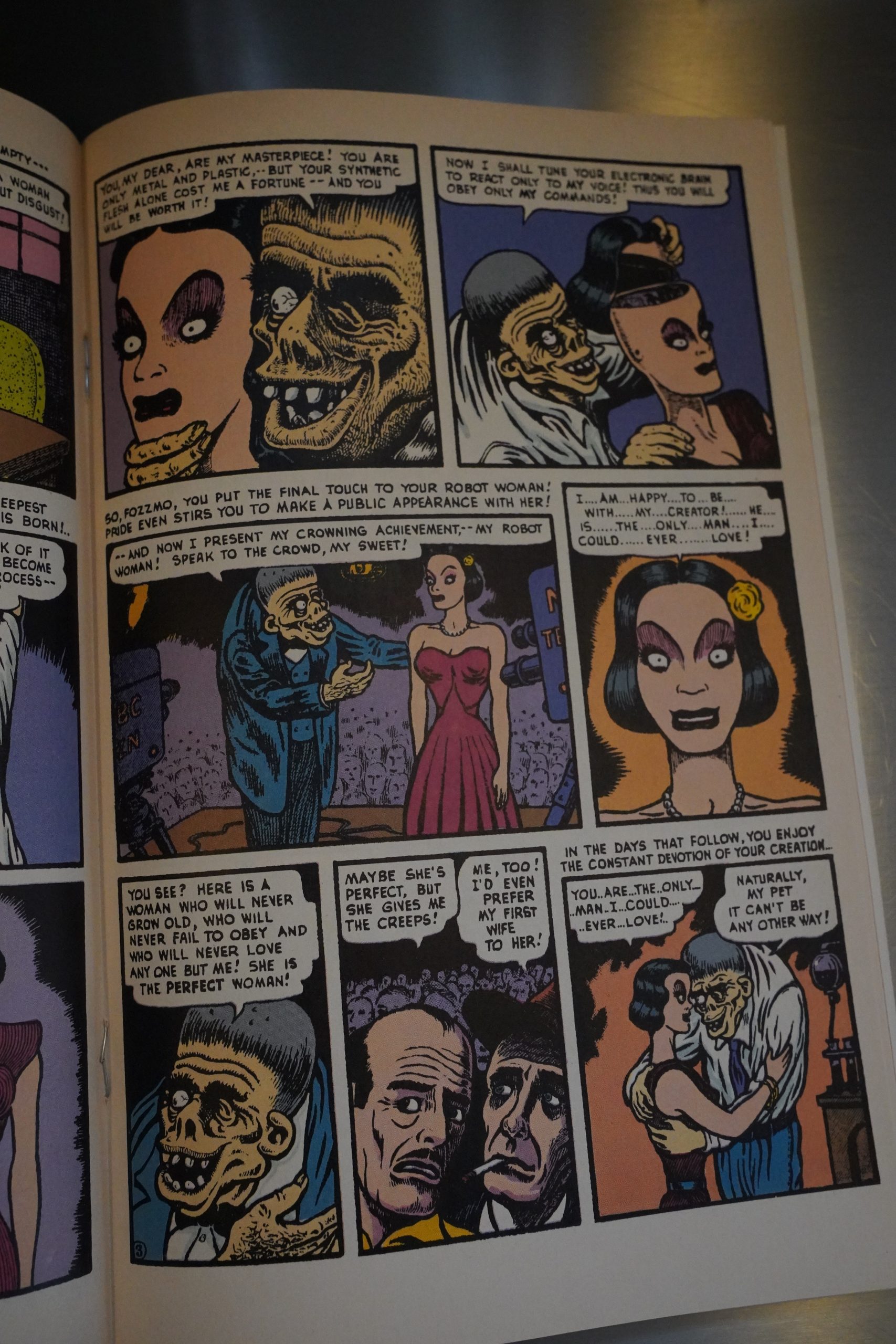

And so it turns out that the Rand Holmes is a reprint from the late seventies, but newly coloured. It’s a fun take on a classic EC story, somewhat incoherently told, but with Holmes doing his very best Wally Wood impersonation, so that’s fine.

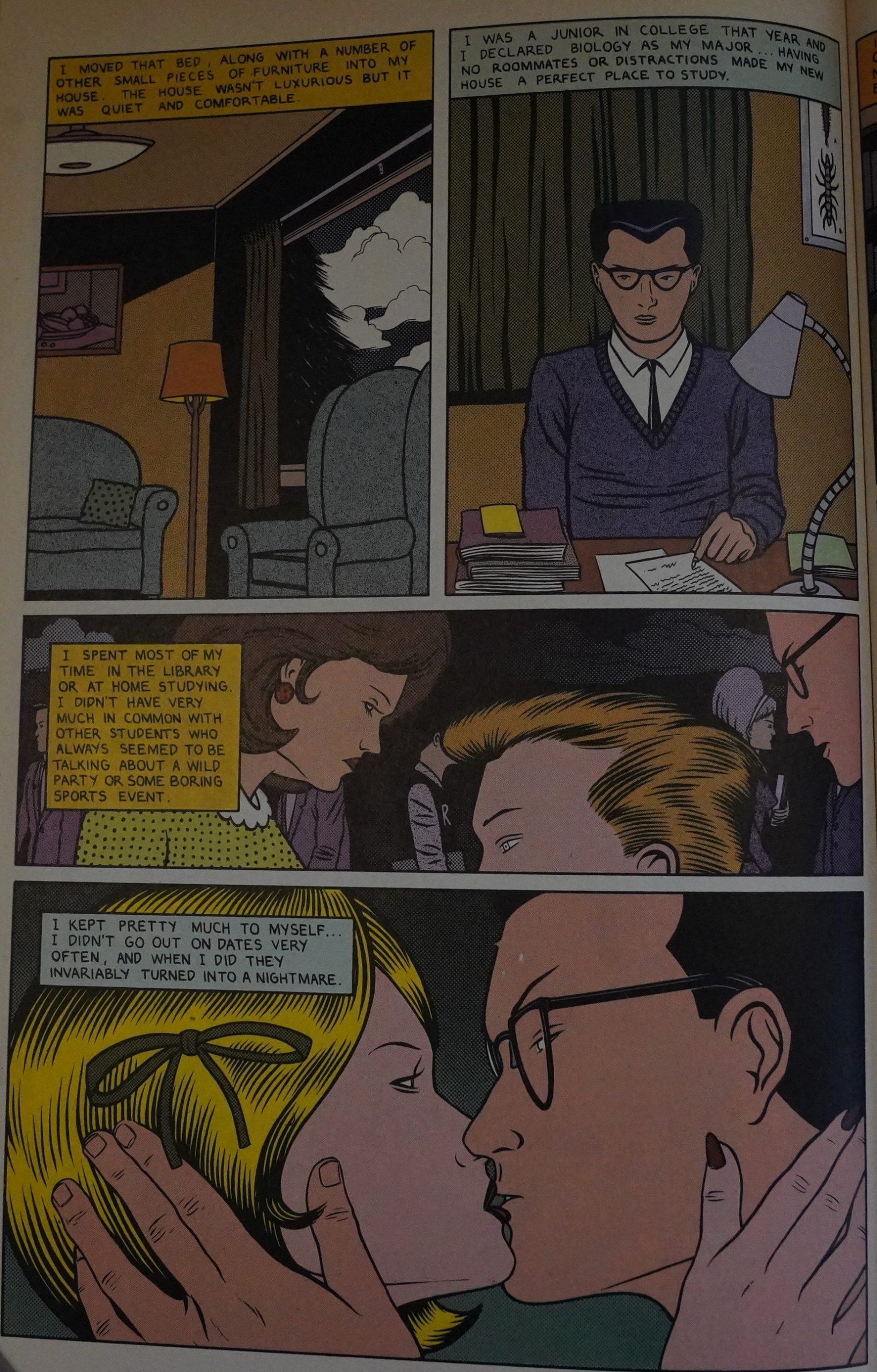

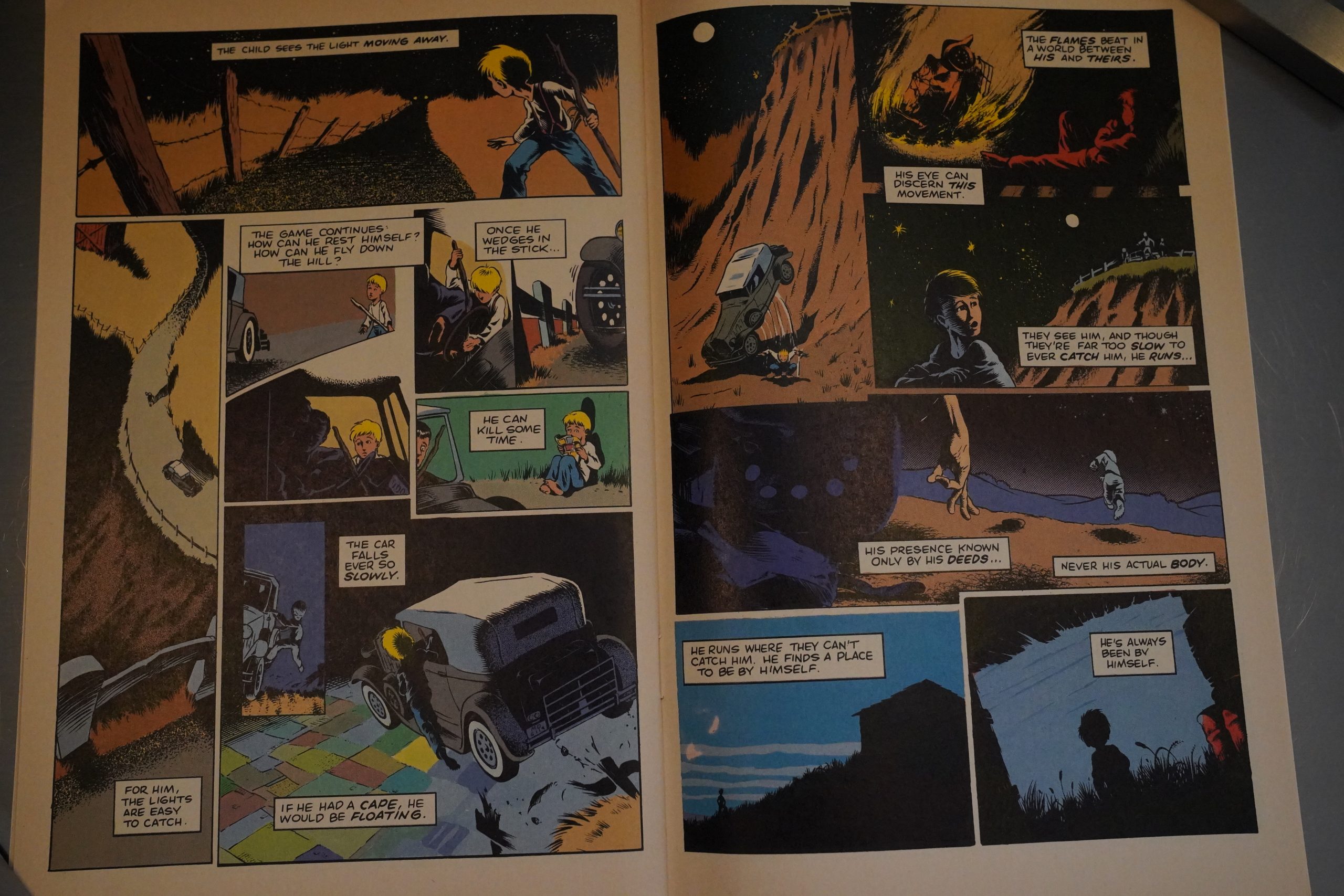

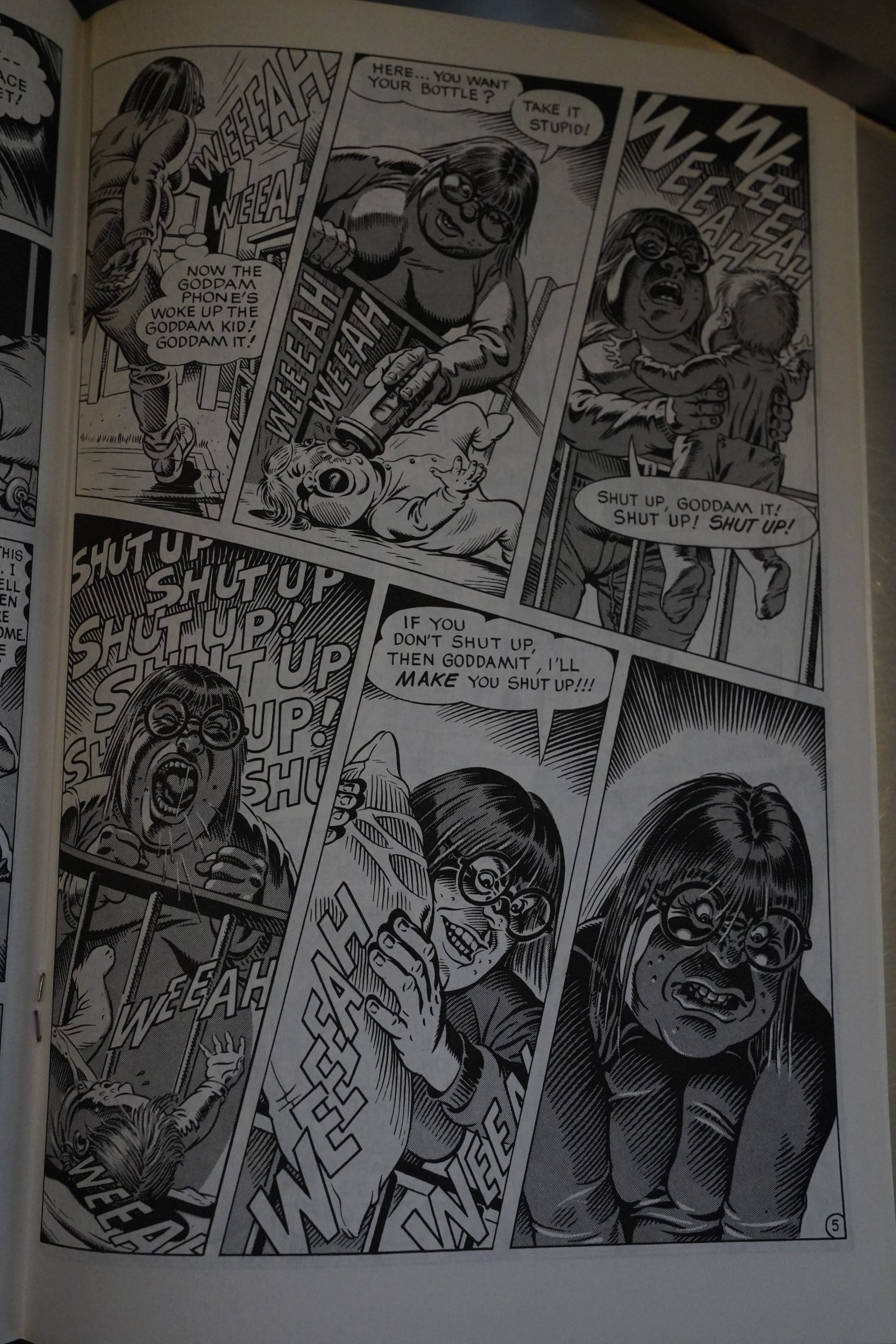

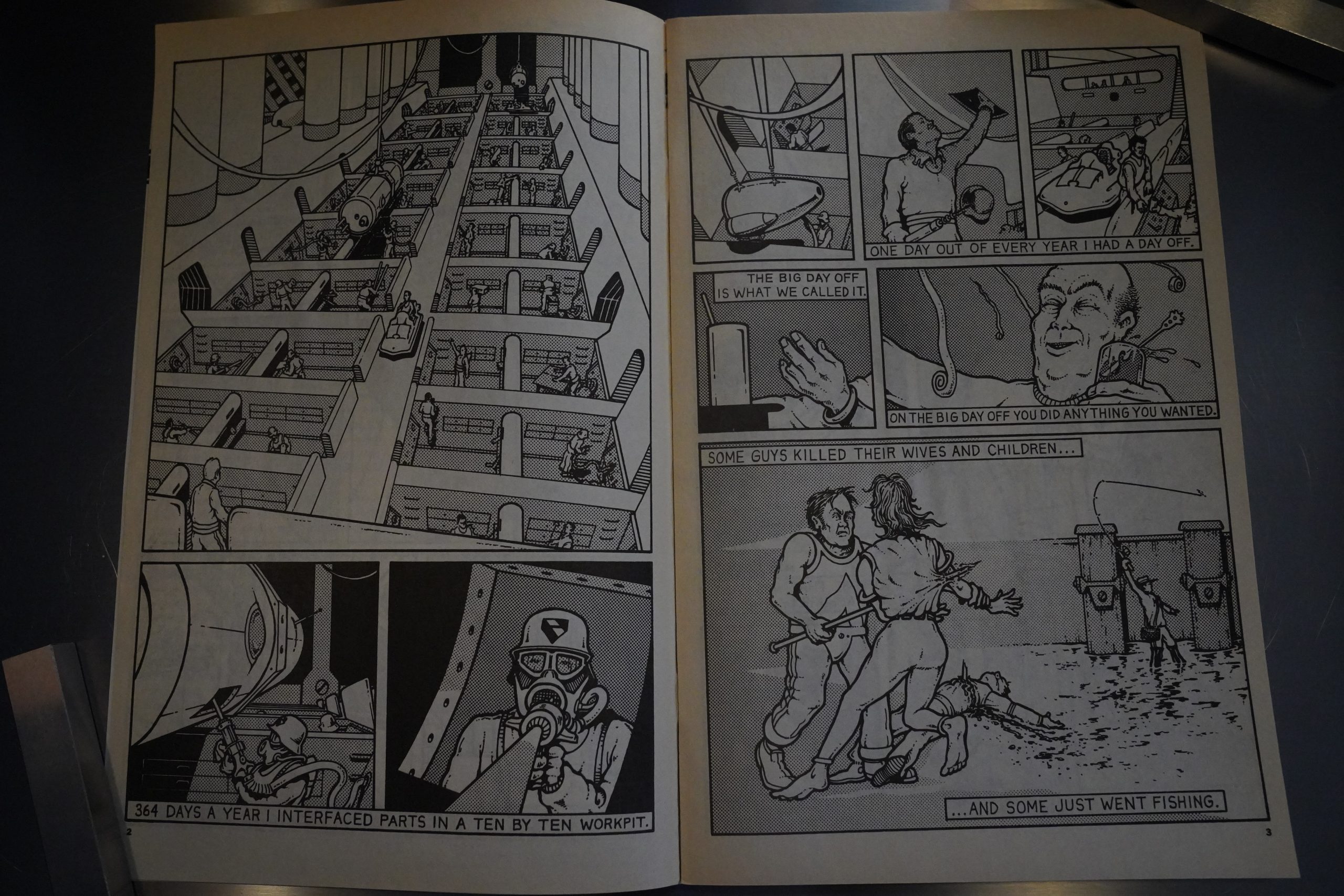

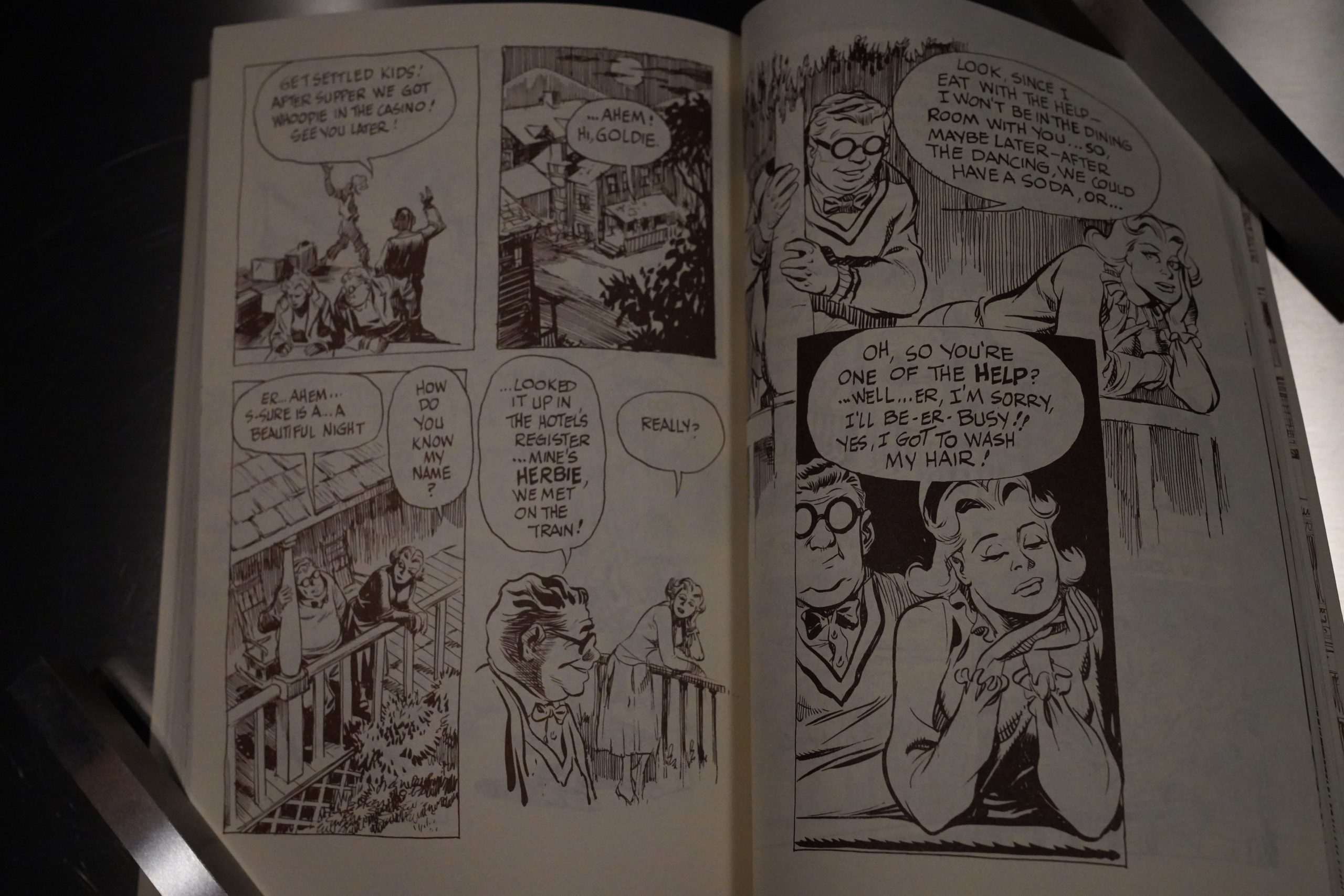

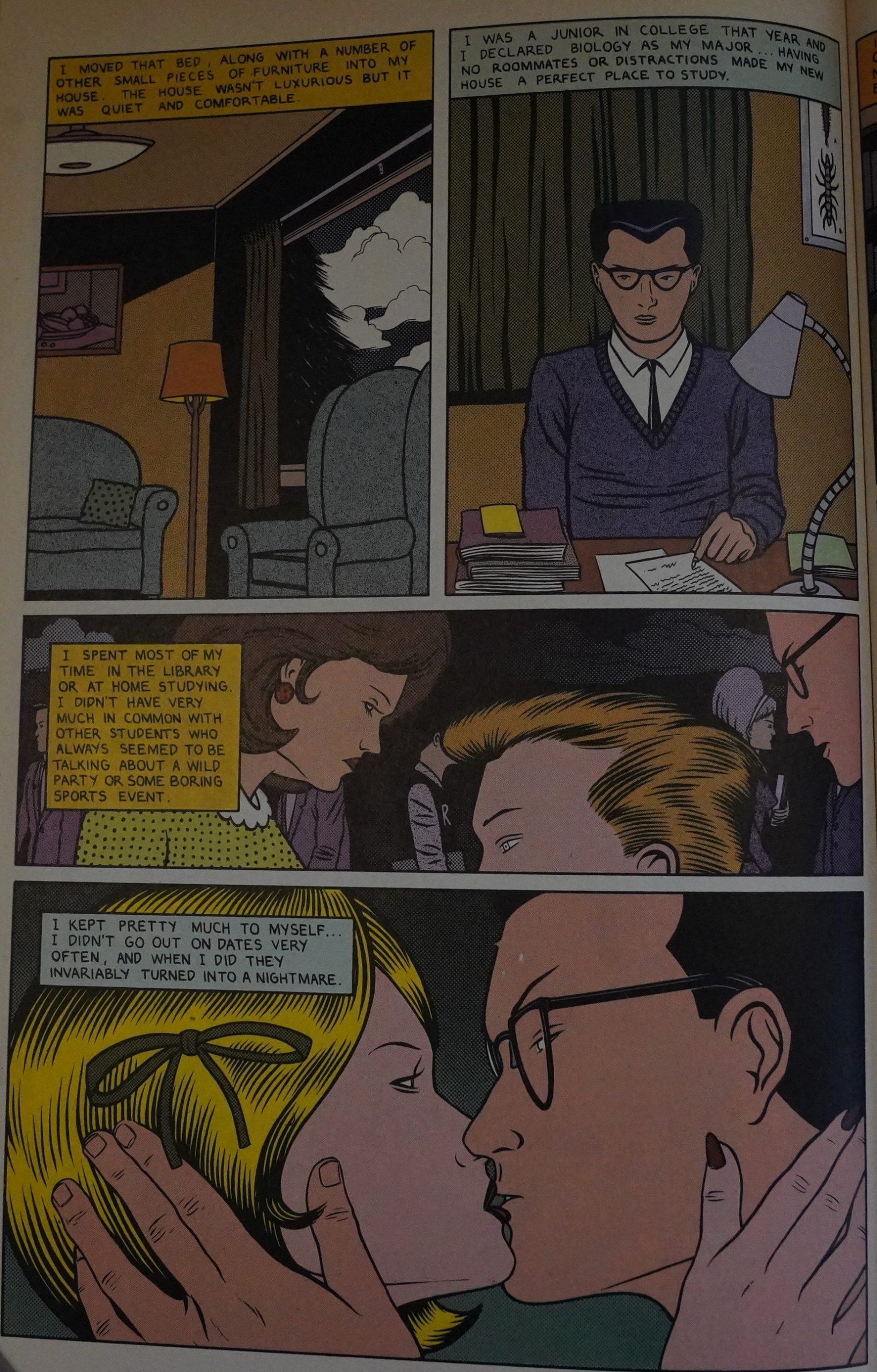

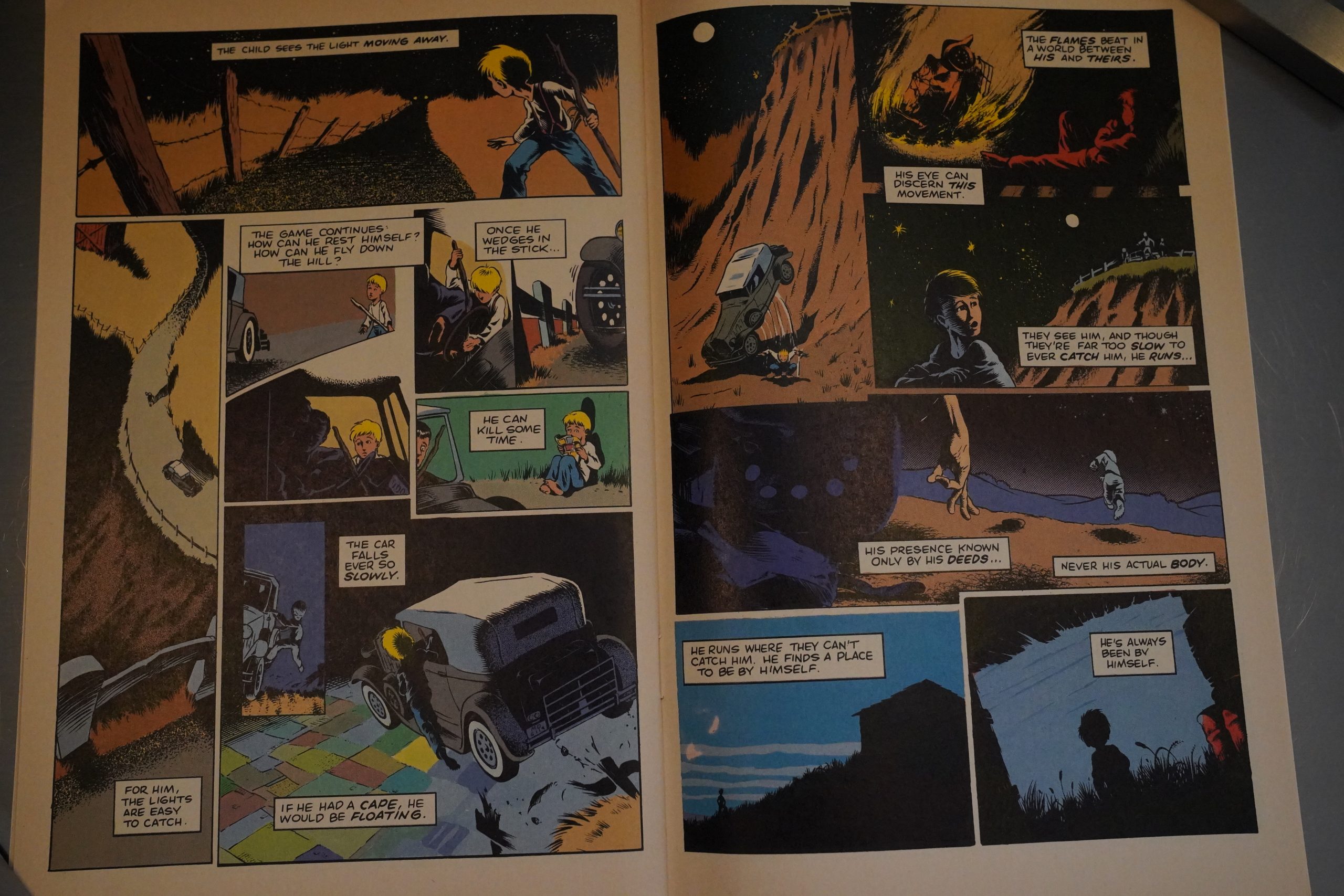

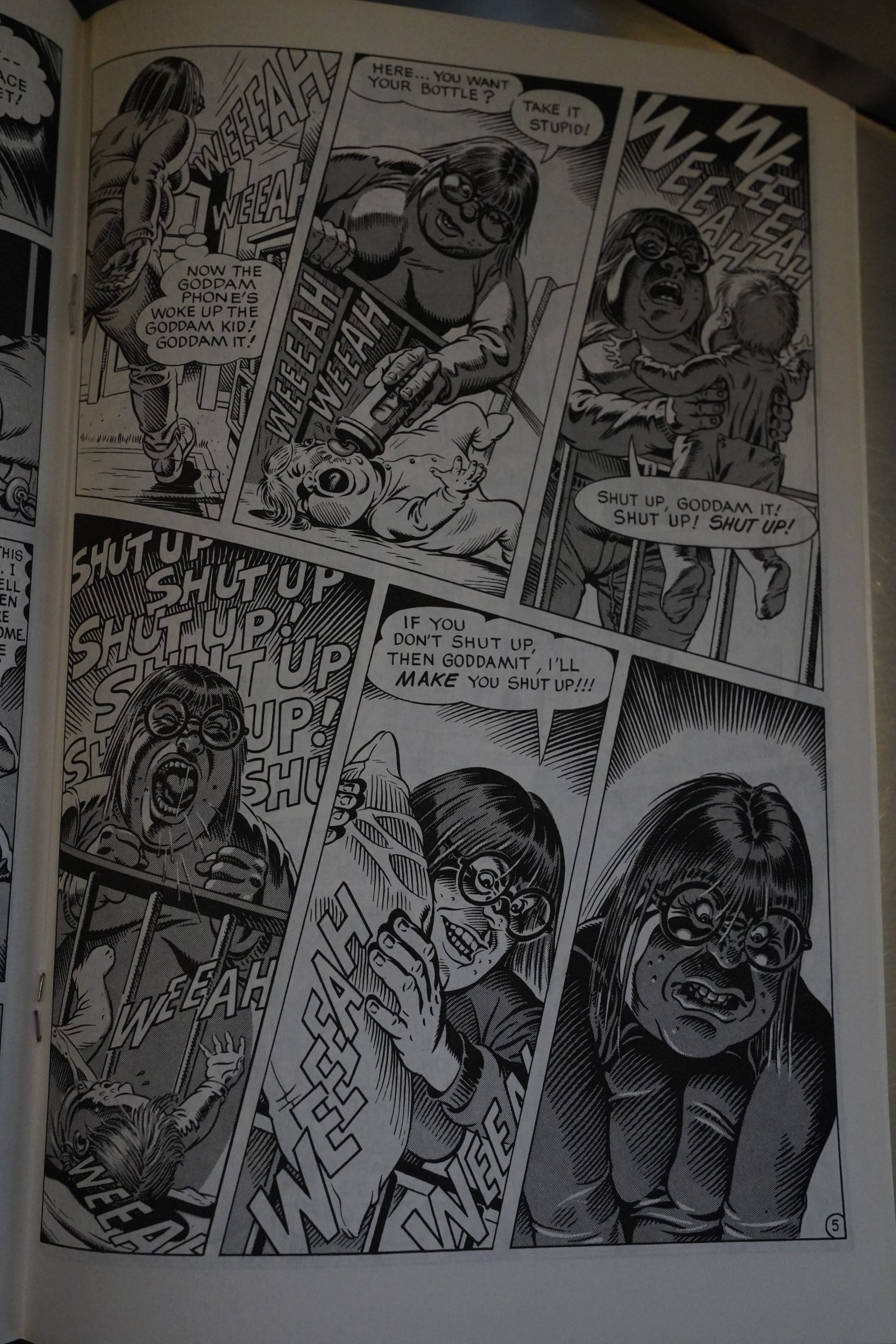

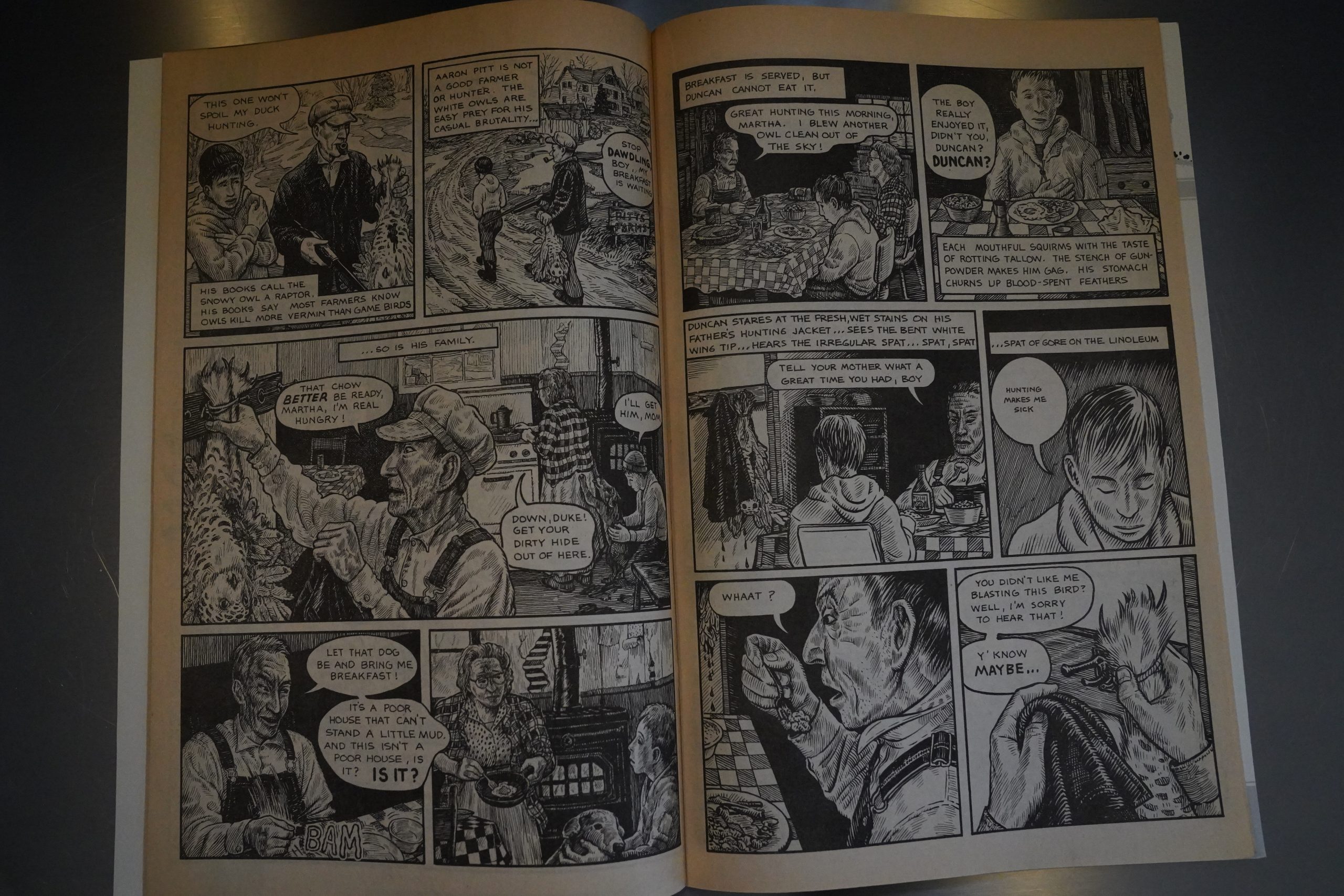

The centrepiece of the book is eighteen pages of exquisite Charles Burns horror, and I think this story basically explains why I remember Death Rattle so fondly. I mean, not that the rest of the series doesn’t have good stuff, but this is just so super creepy, and stylish, and alien. That little insect/monster is so fascinating.

But this looks like really early Burns work? It’s much simpler than the work Burns was doing in 1985, and it looks like it was originally done for publishing in black and white (what with the zip-a-tone and stuff).

What a nightmare!

This story has apparently never been reprinted. I guess that means that Burns doesn’t much like it? Burns has done plenty of horrific stories, but this tips way over into despair and torture porn, really — the ending is, to put it mildly, a downer. Which is probably why it made such an impression on me at the time.

I mean, apart from the fascinating artwork.

And then we end with a three-pager by Charles Dallas that doesn’t seem to have anything to do with anything, which is a typical Kitchen Sink think to do.

So: I think Kitchen’s approach to anthologies hasn’t changed since the 70s. I’m guessing he’d gotten the rights to the Burns story, and then he coupled that with the Corben painting he had, reprinted an old Holmes story, and then added some padding, and presto! Death Rattle is reborn!

But it’s totally worth it. This issue is wonderful.

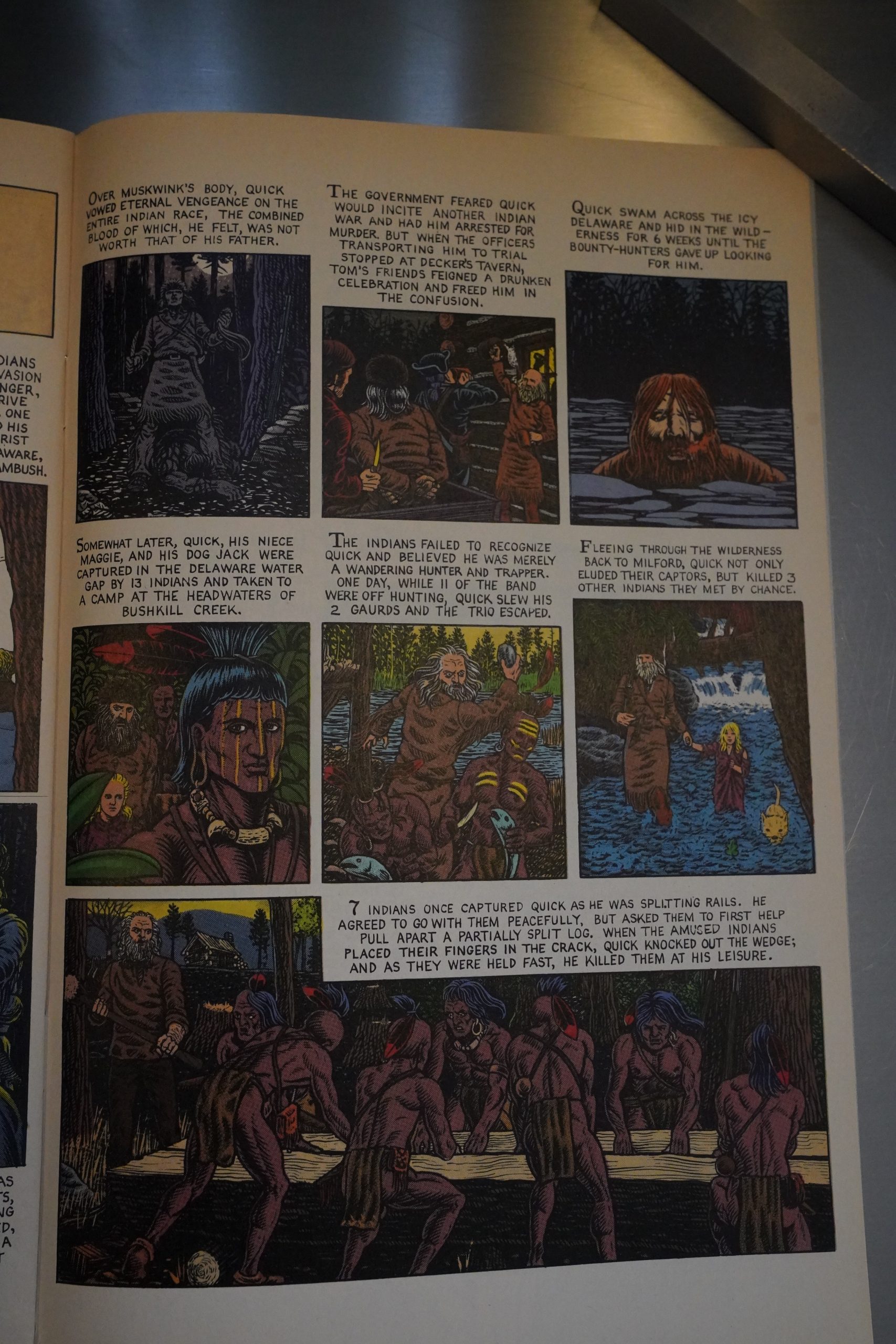

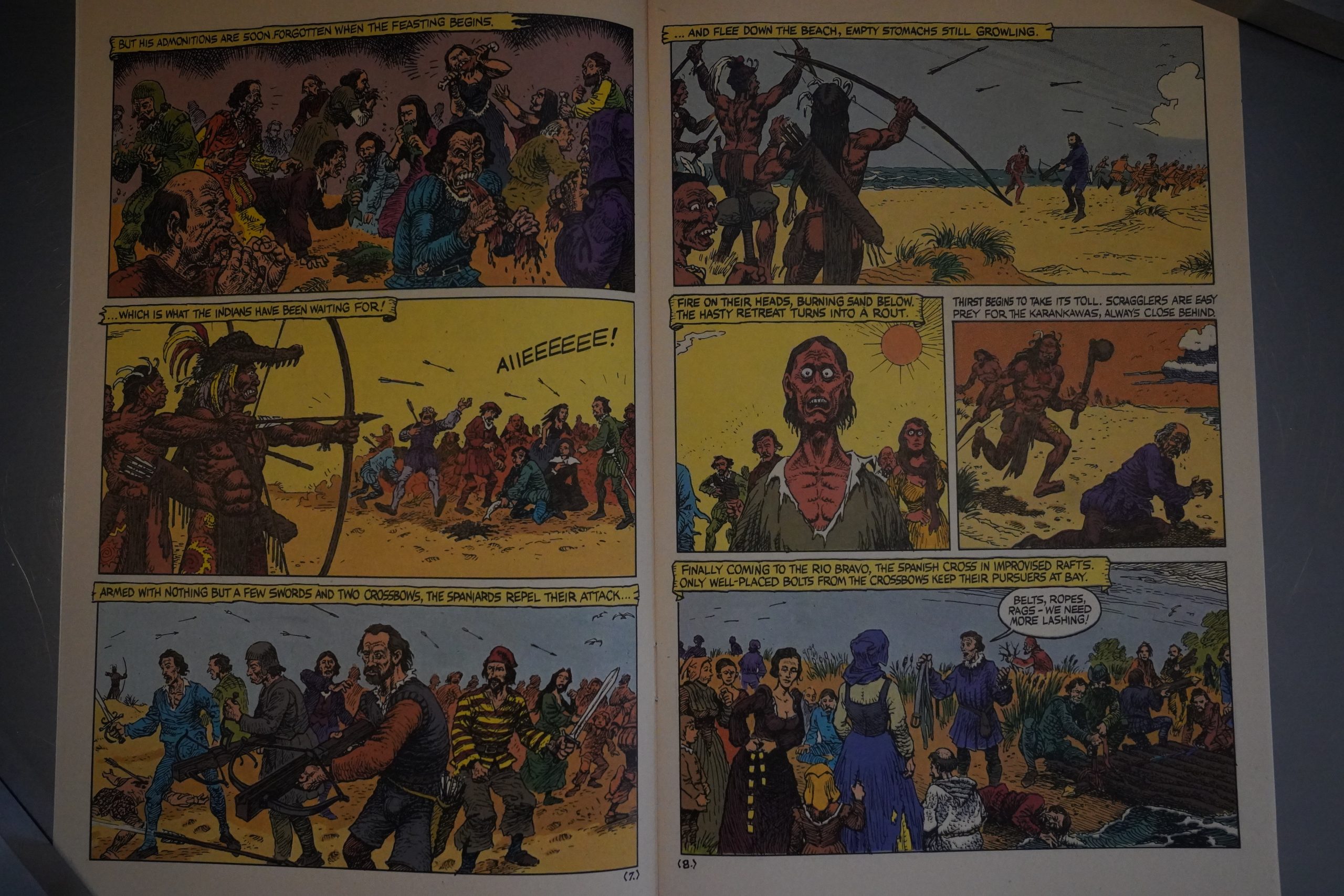

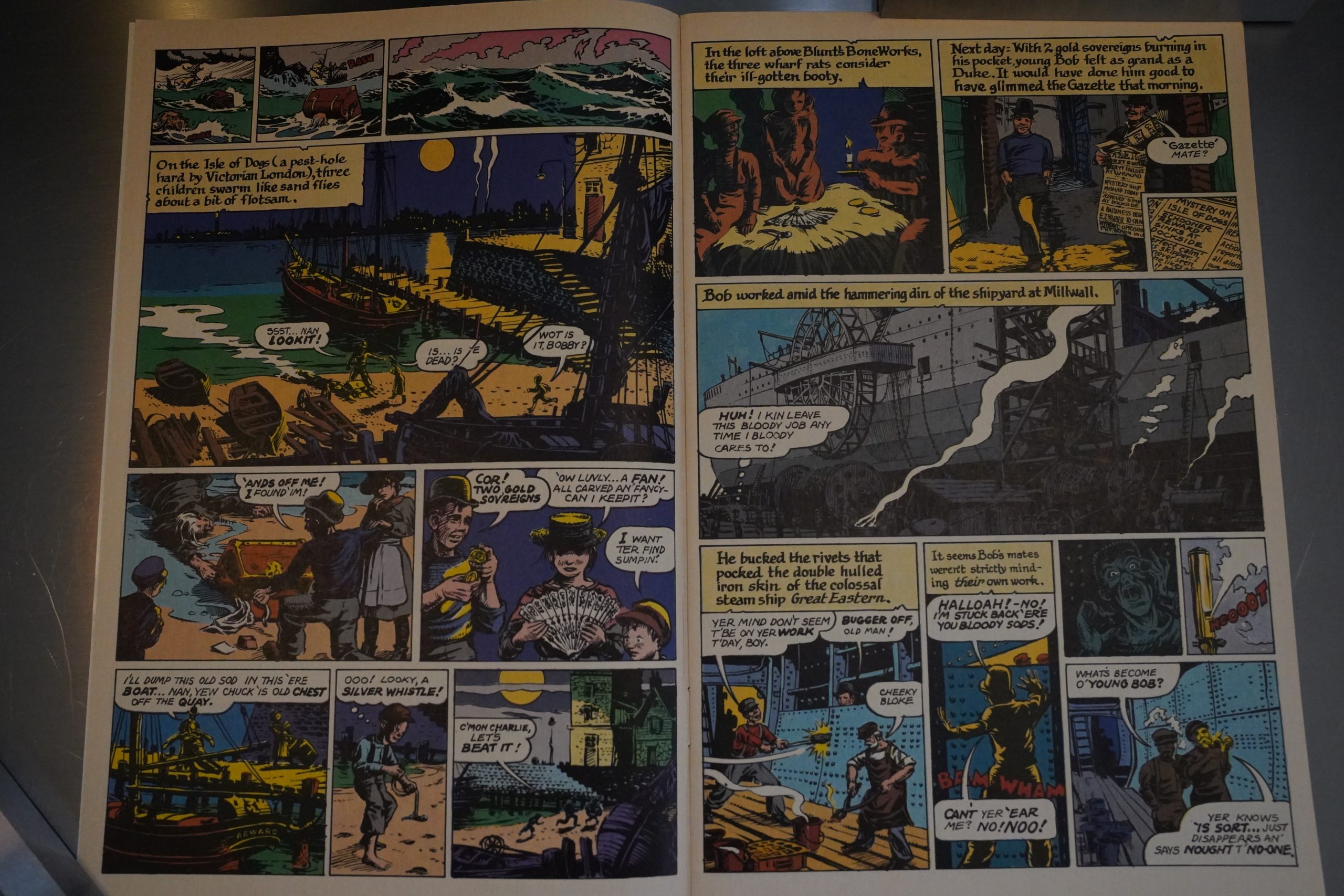

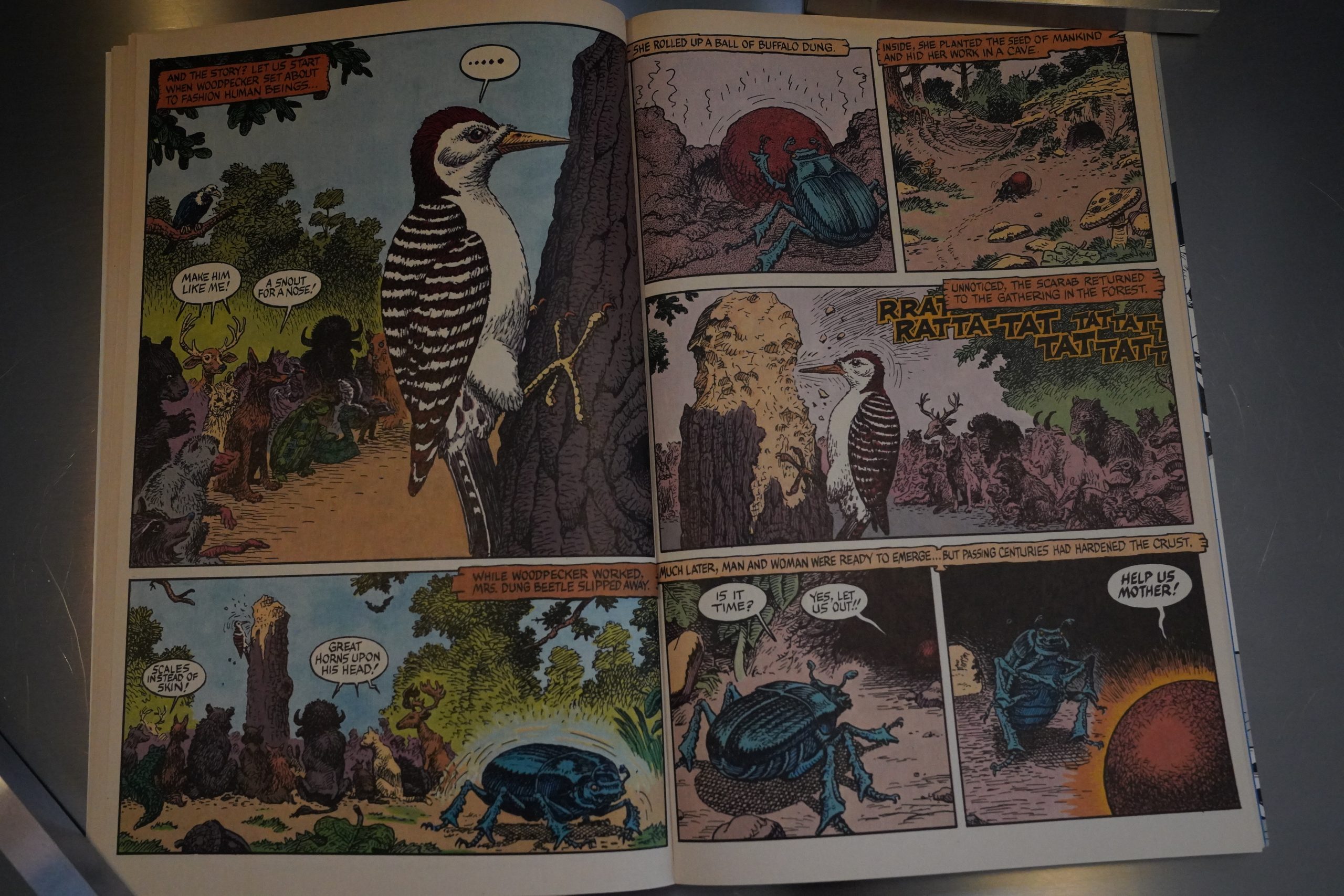

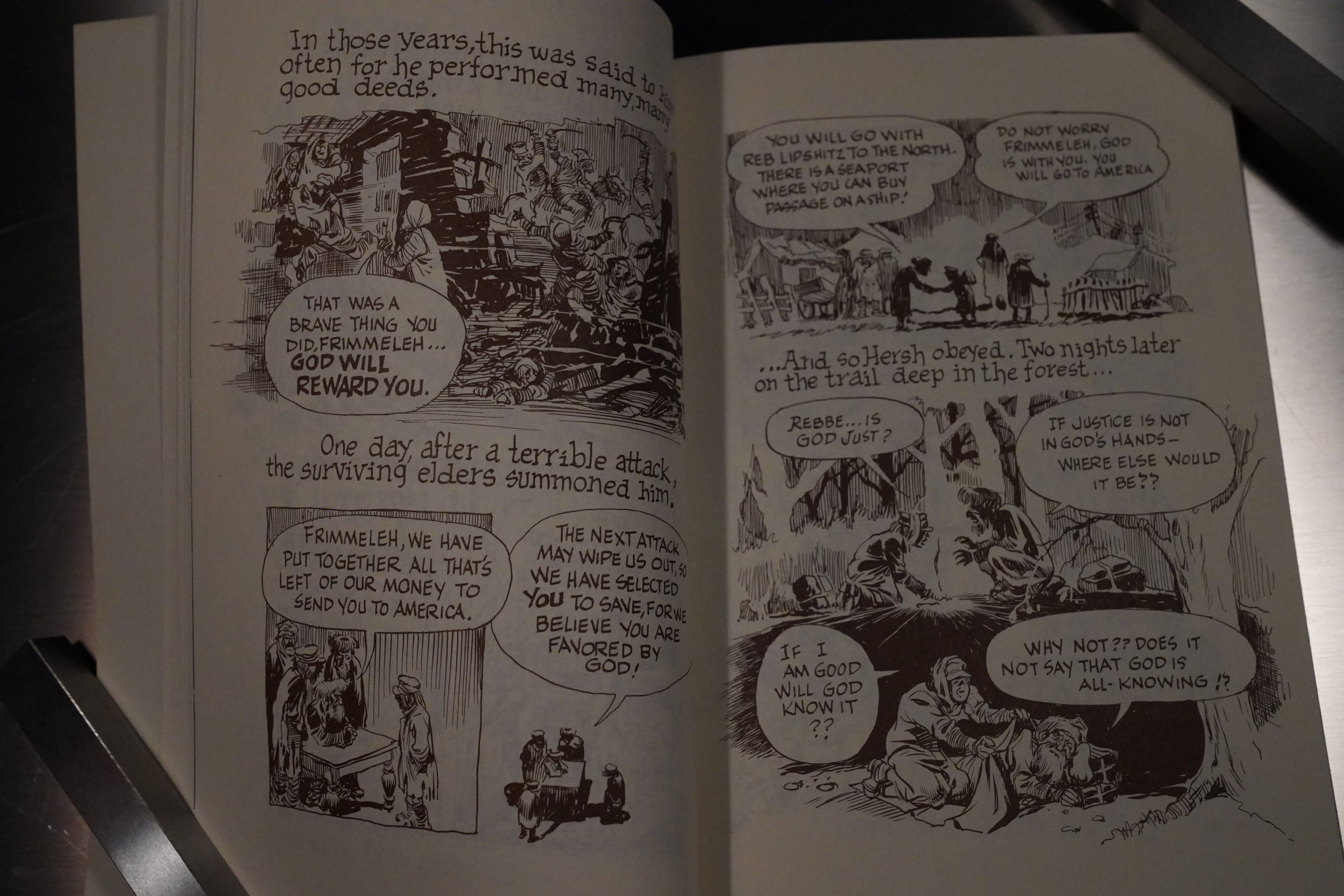

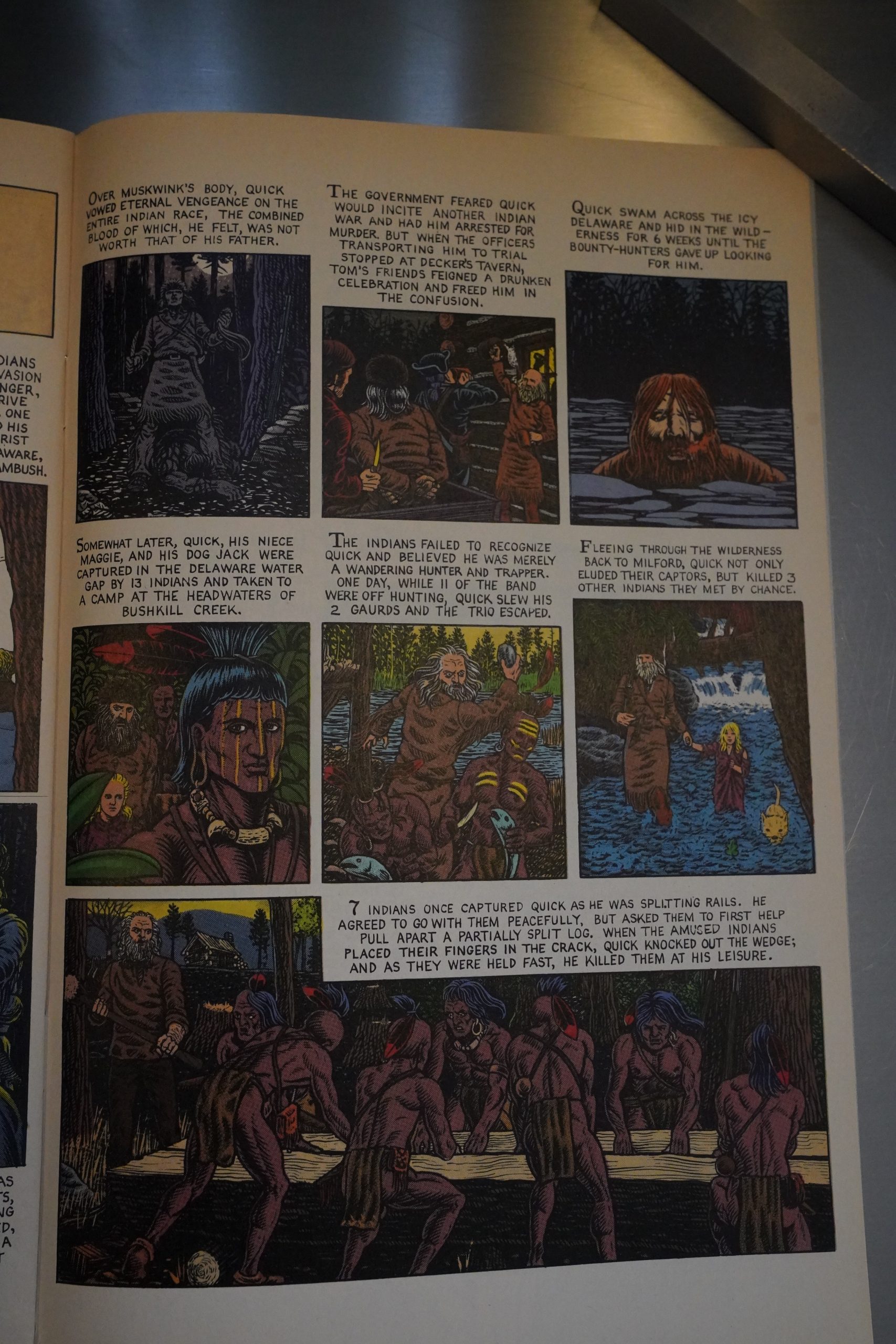

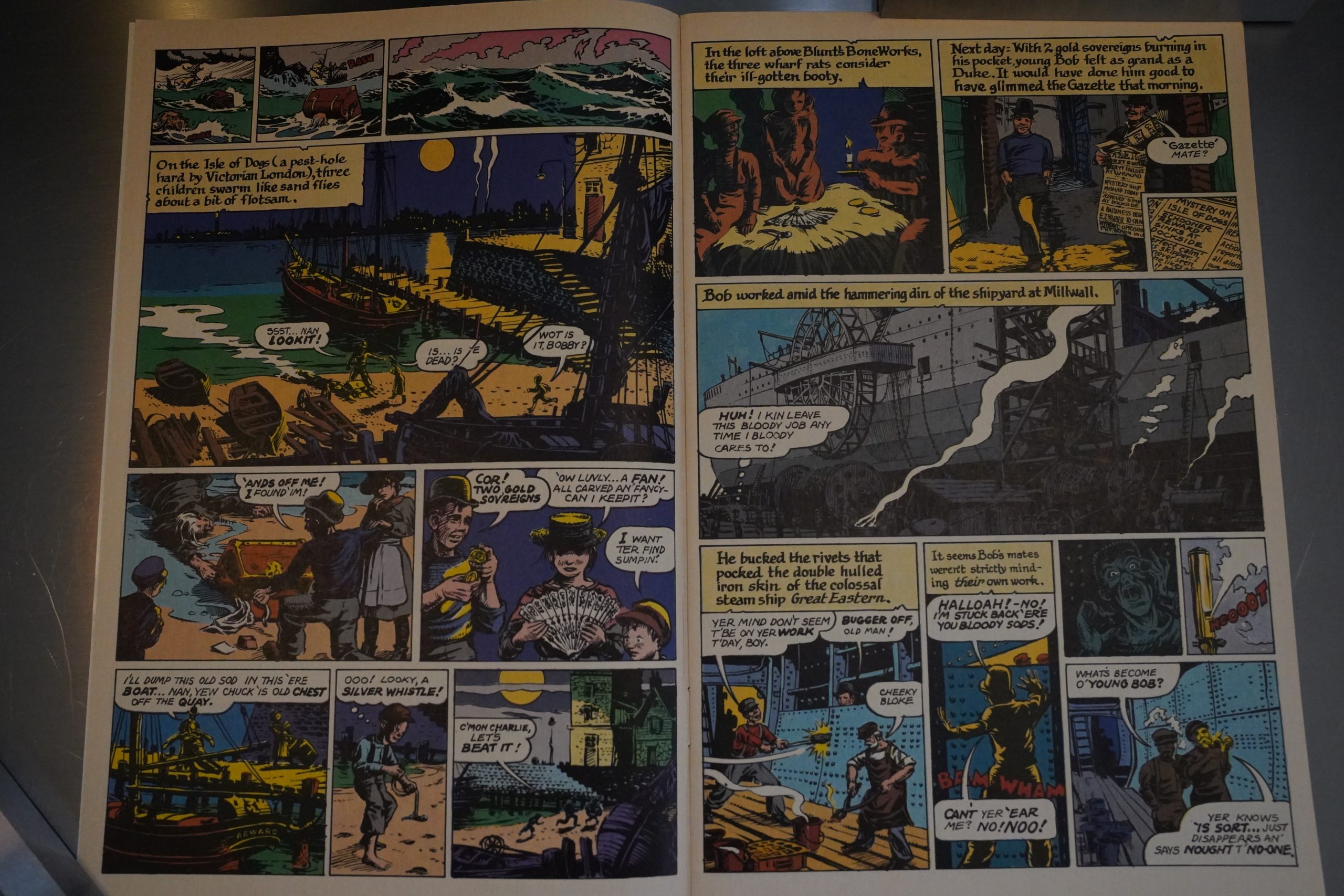

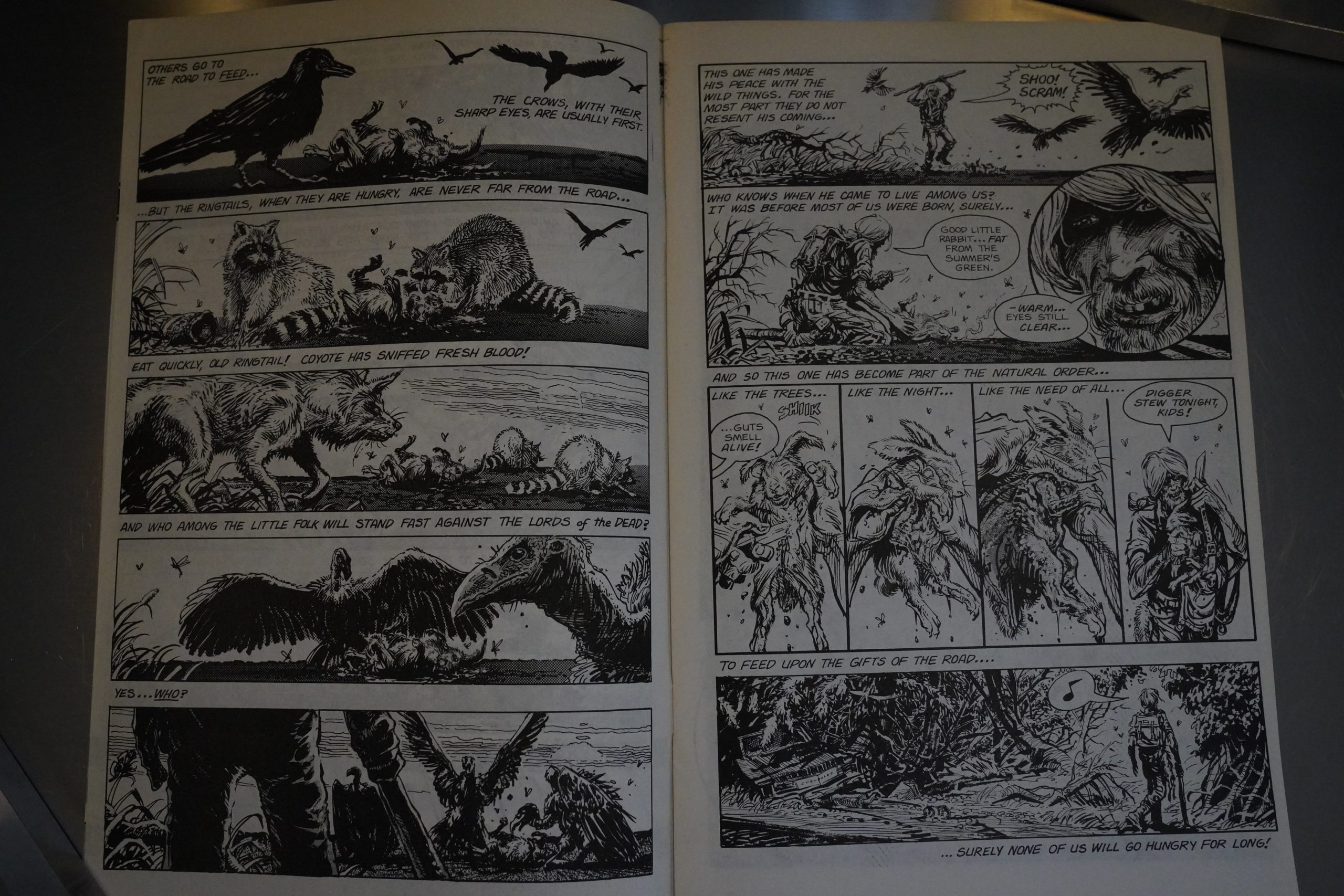

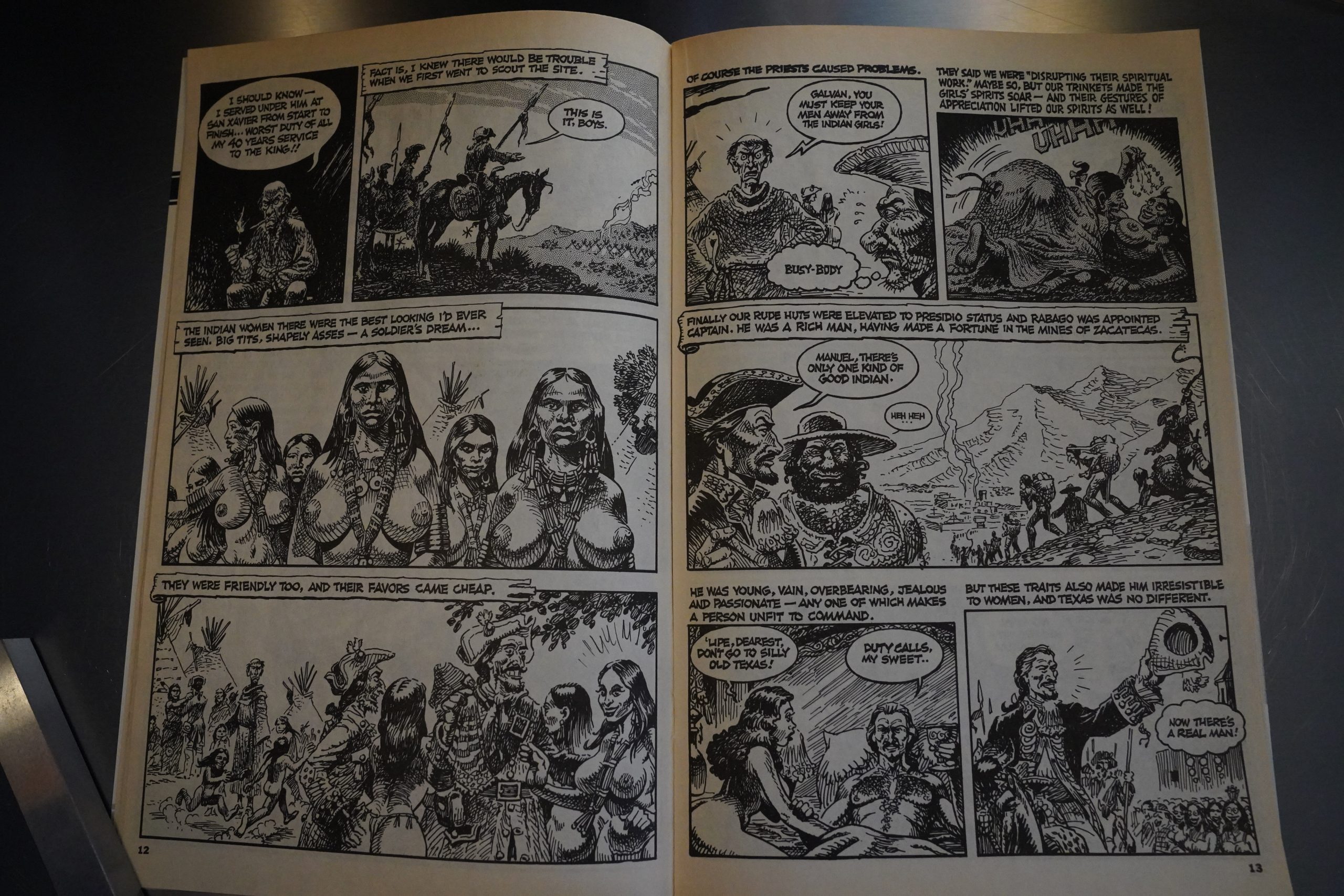

So what to do for the second issue, then? Does Kitchen have more stuff? The point of the second issue is this Jaxon story, which is a harrowing, horrific and apparently true story. And Jaxon’s clear storytelling style makes things even more gruesome, somehow.

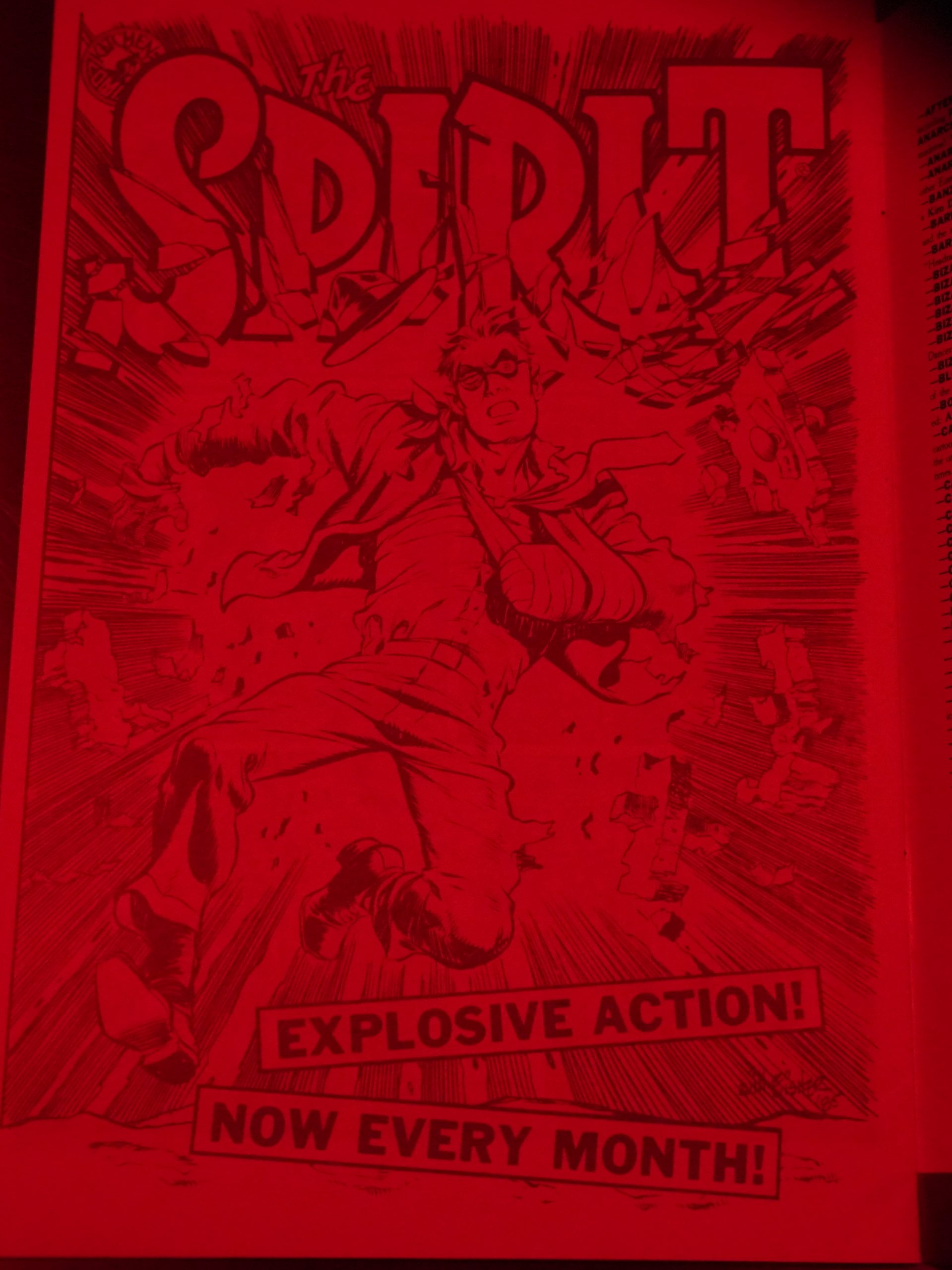

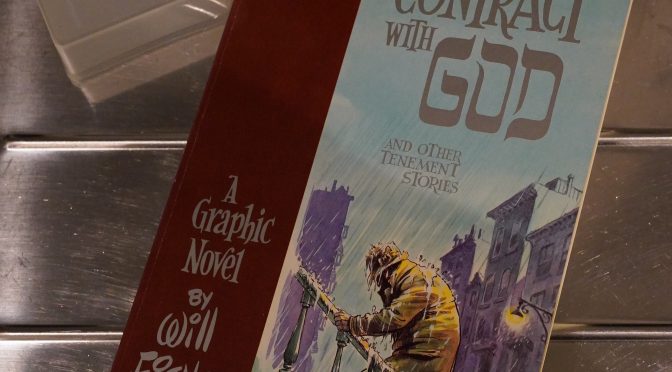

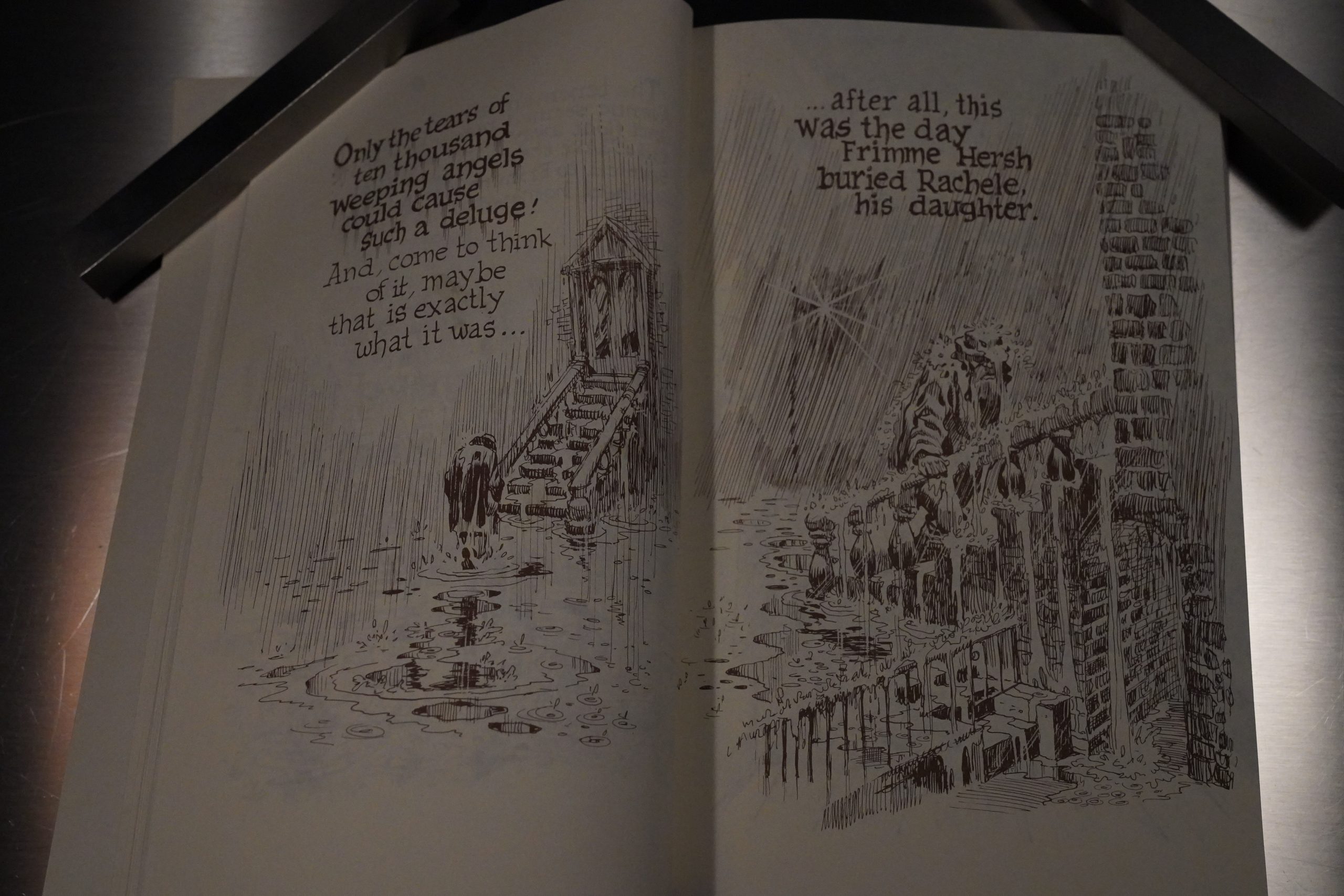

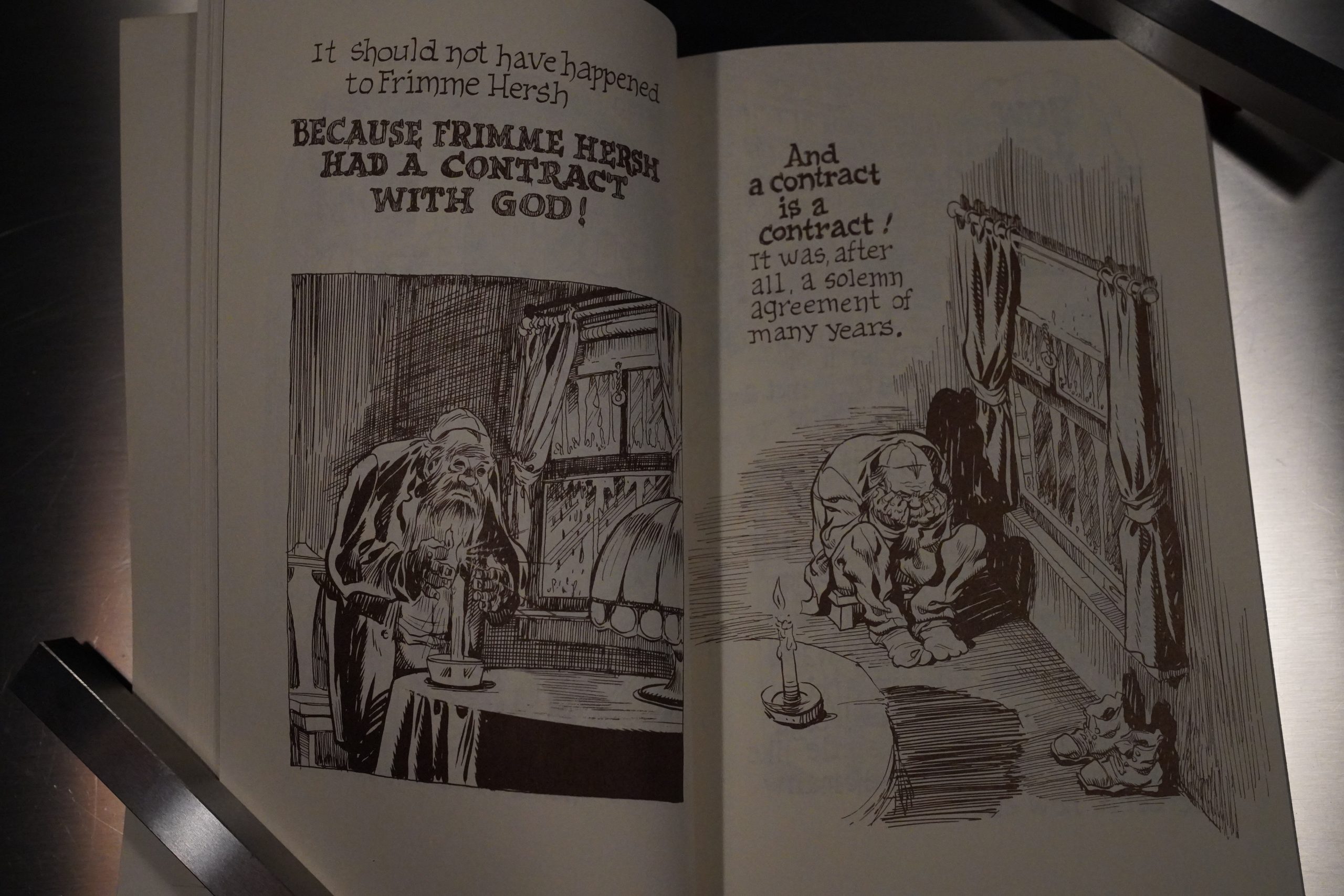

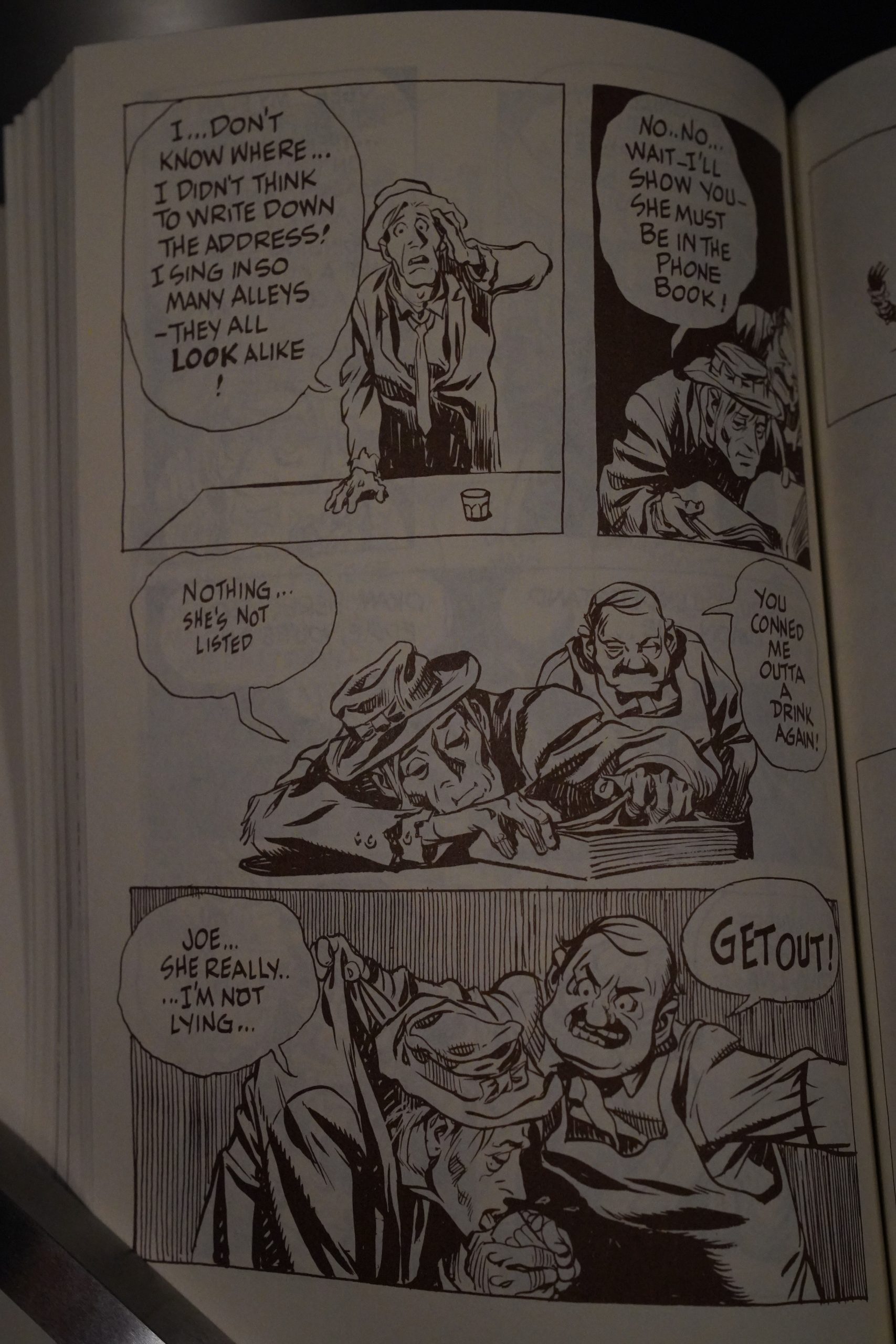

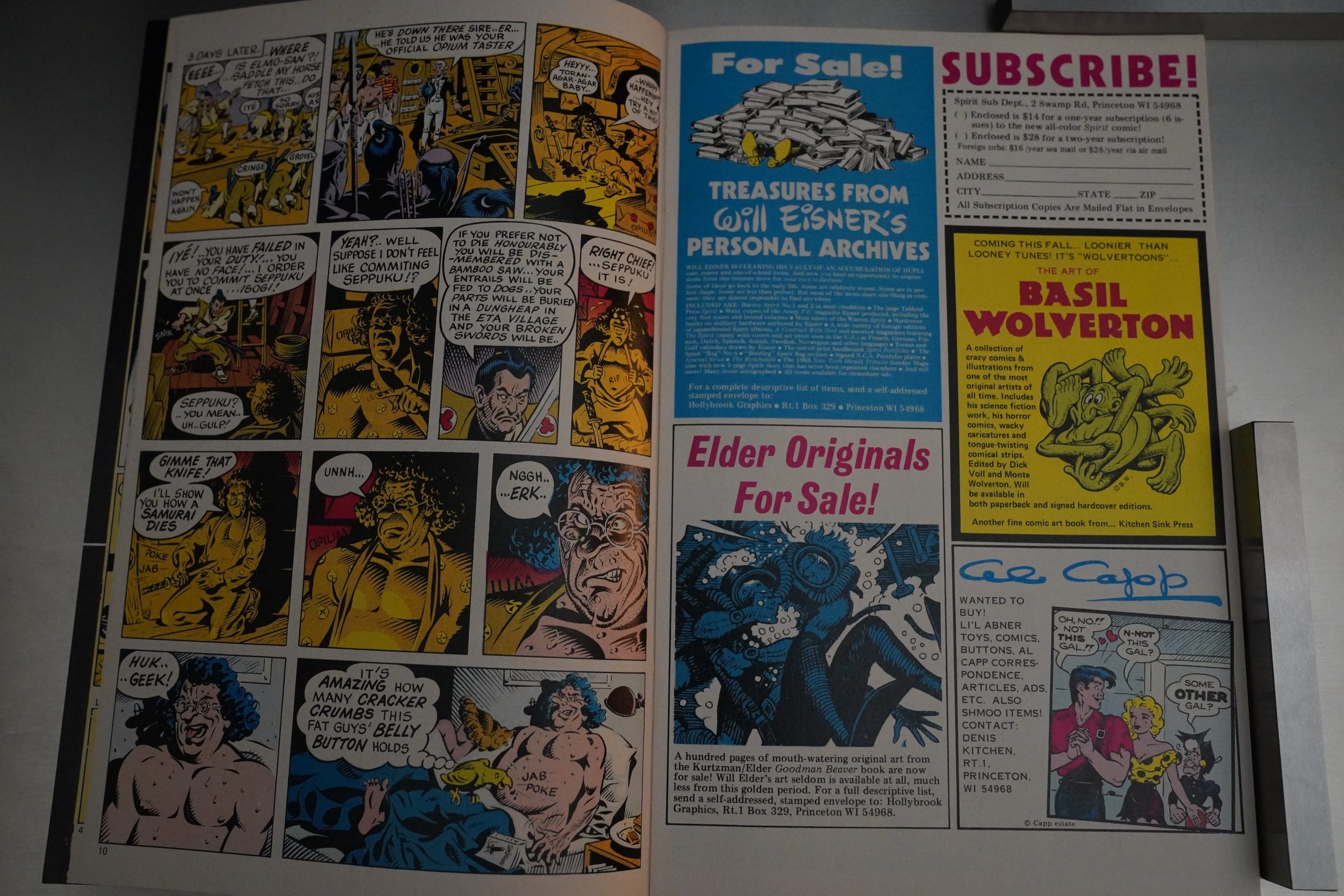

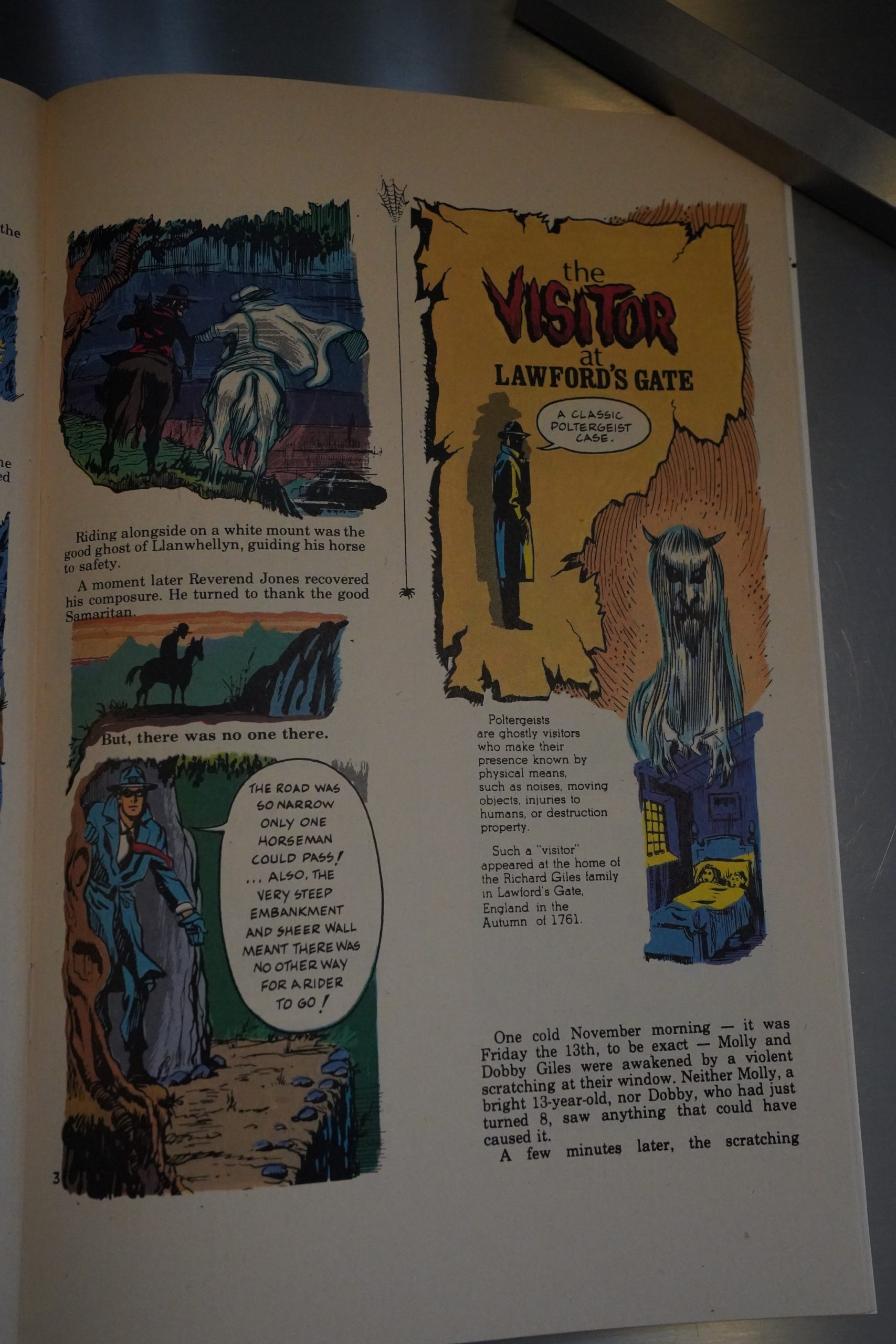

And then we get to the padding: A reprint of something Will Eisner did in the 70s?

And really fun thing Rand Holmes did in the late 70s. Check! So the second issue is also a “make this work” thing… but surely Kitchen would have to start actually soliciting people for new work to keep the series going?

And indeed, with the third issue there seems to be money to pay people for new material… but not too much, apparently, since we get this really bad thing from Doug Hansen.

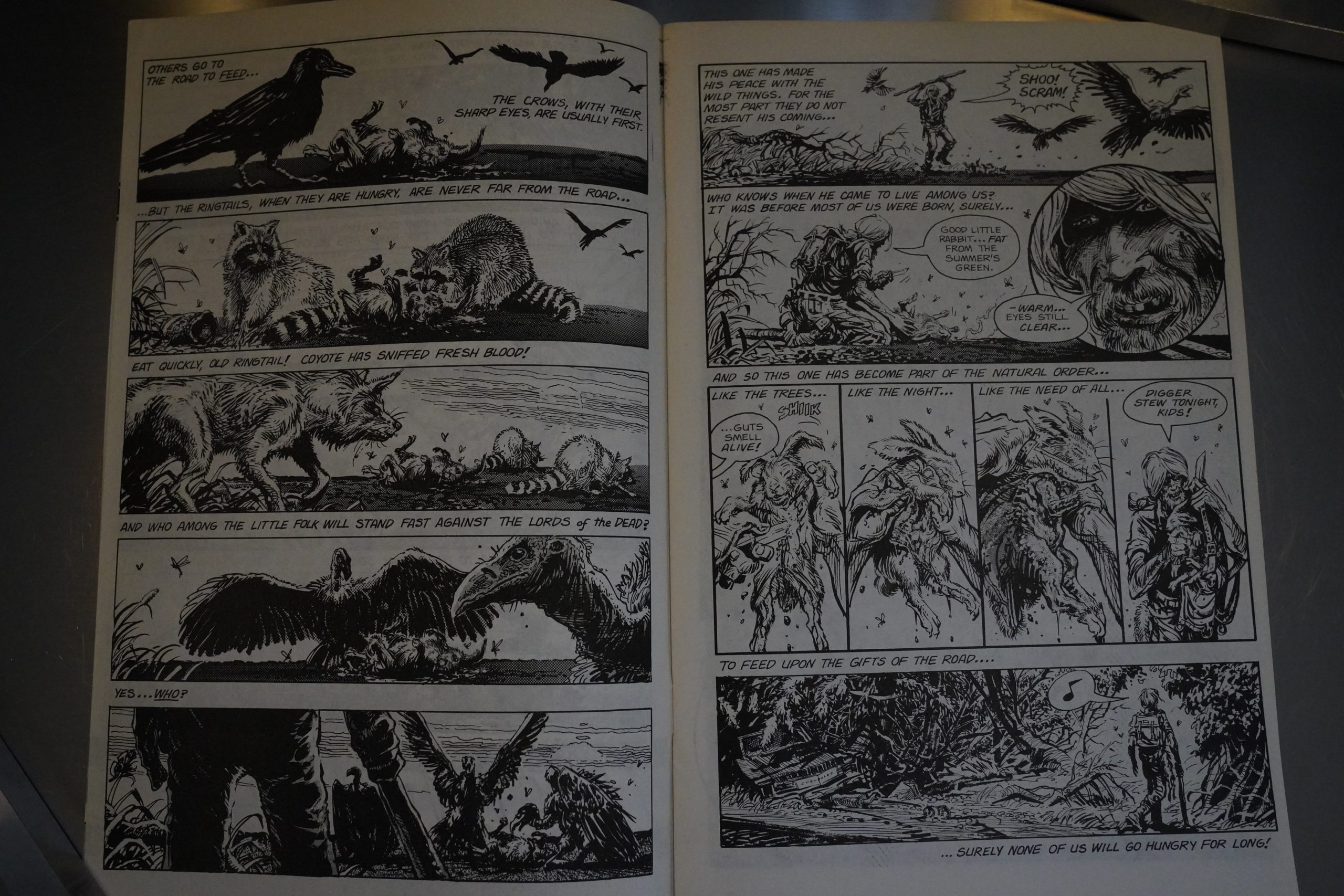

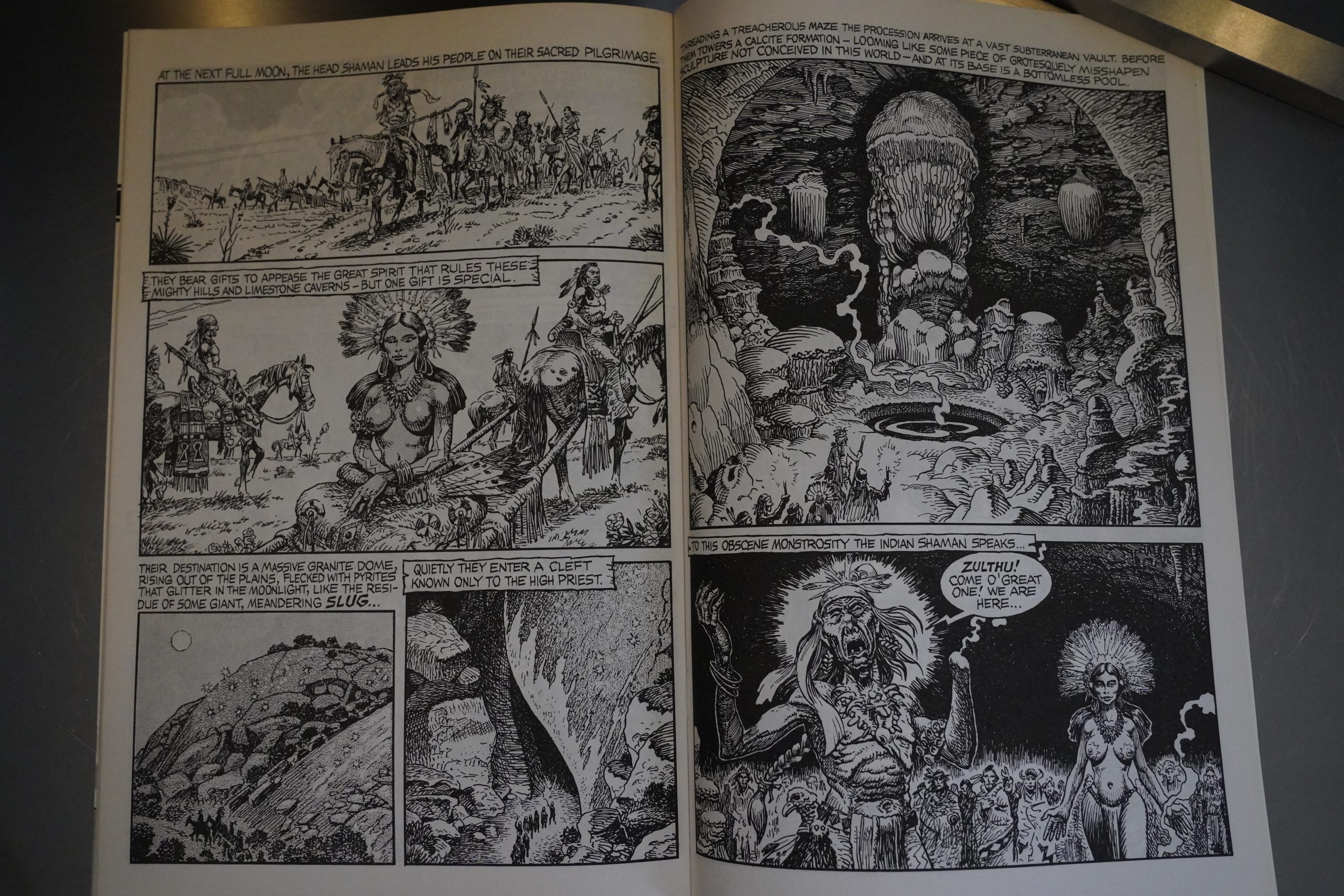

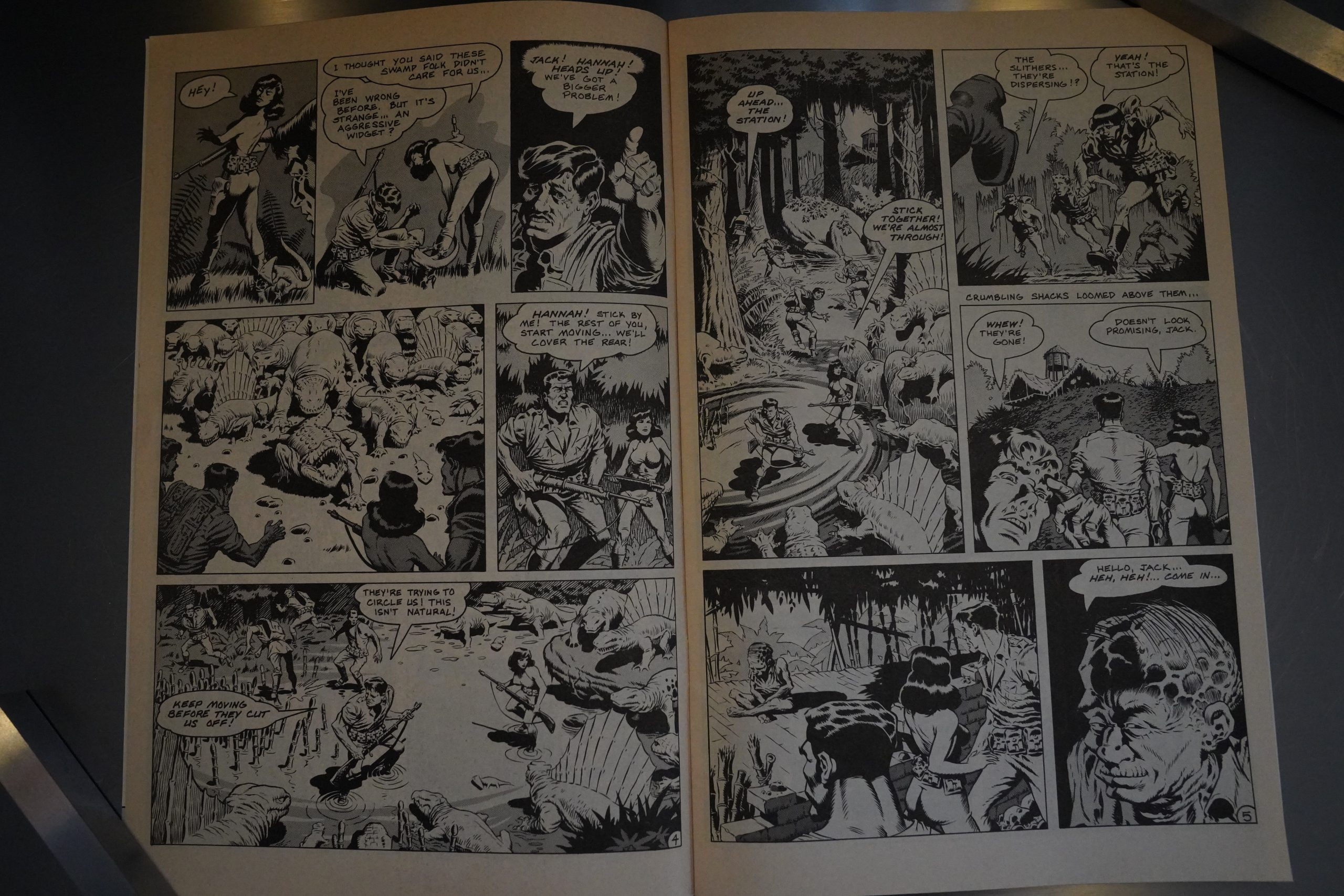

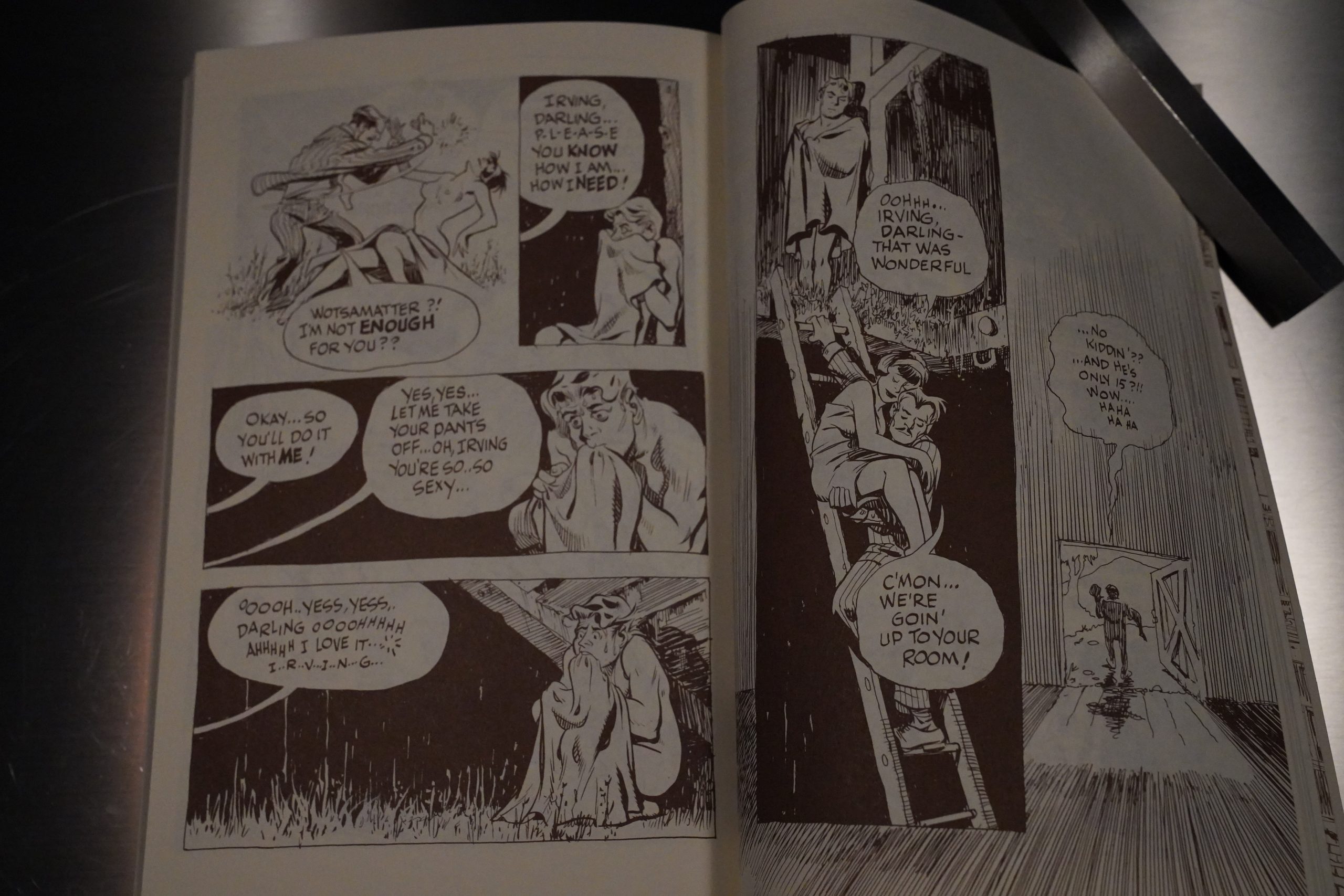

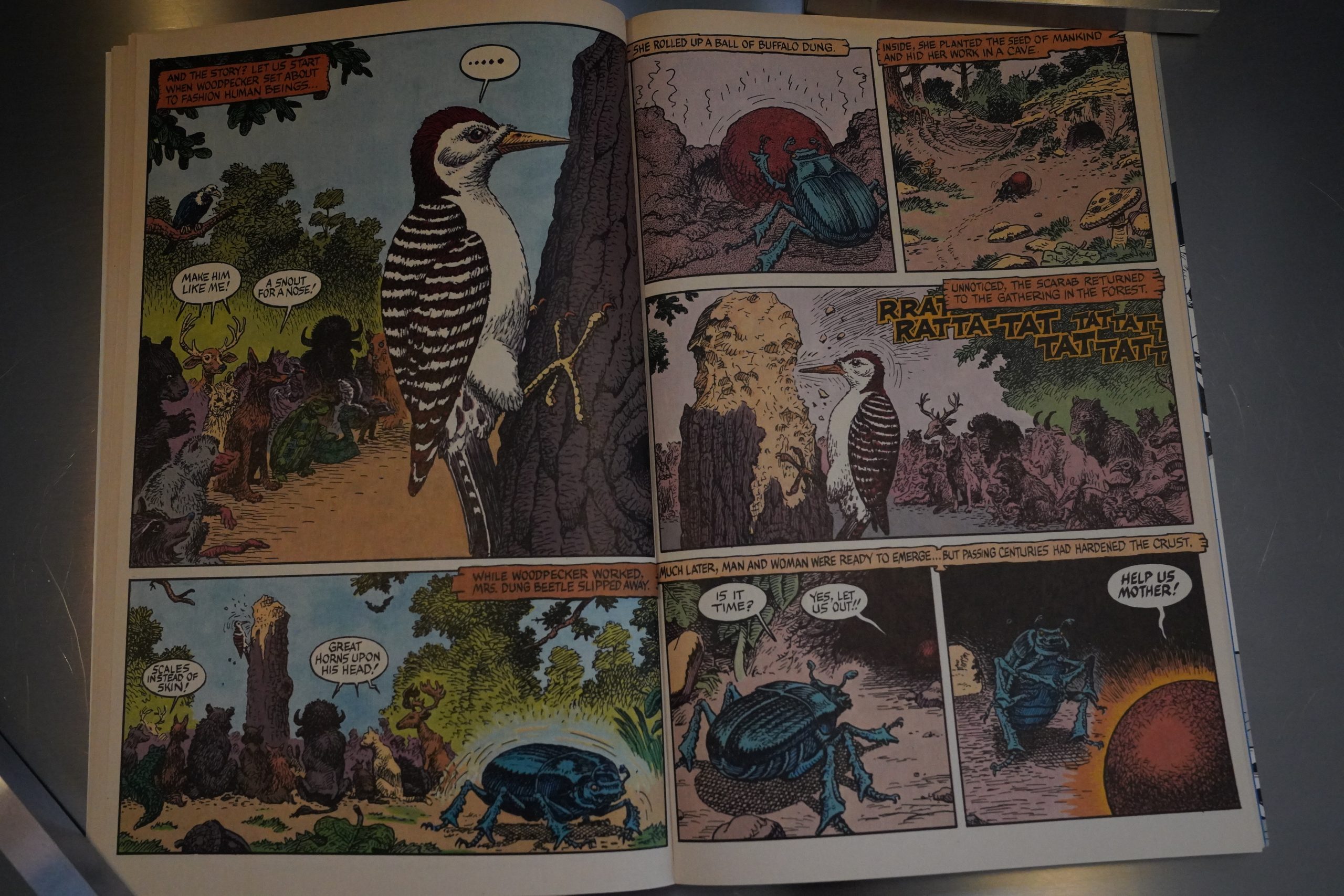

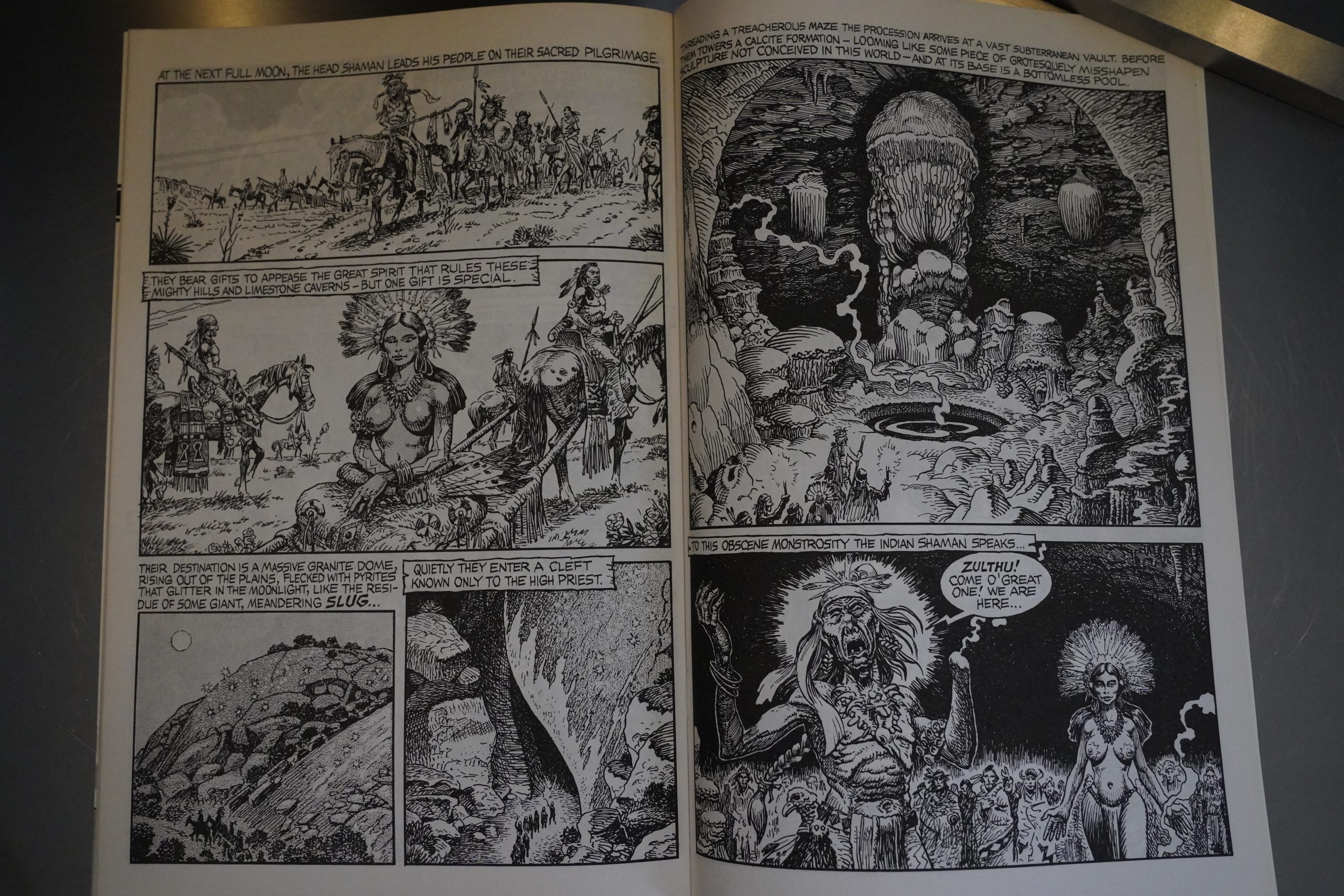

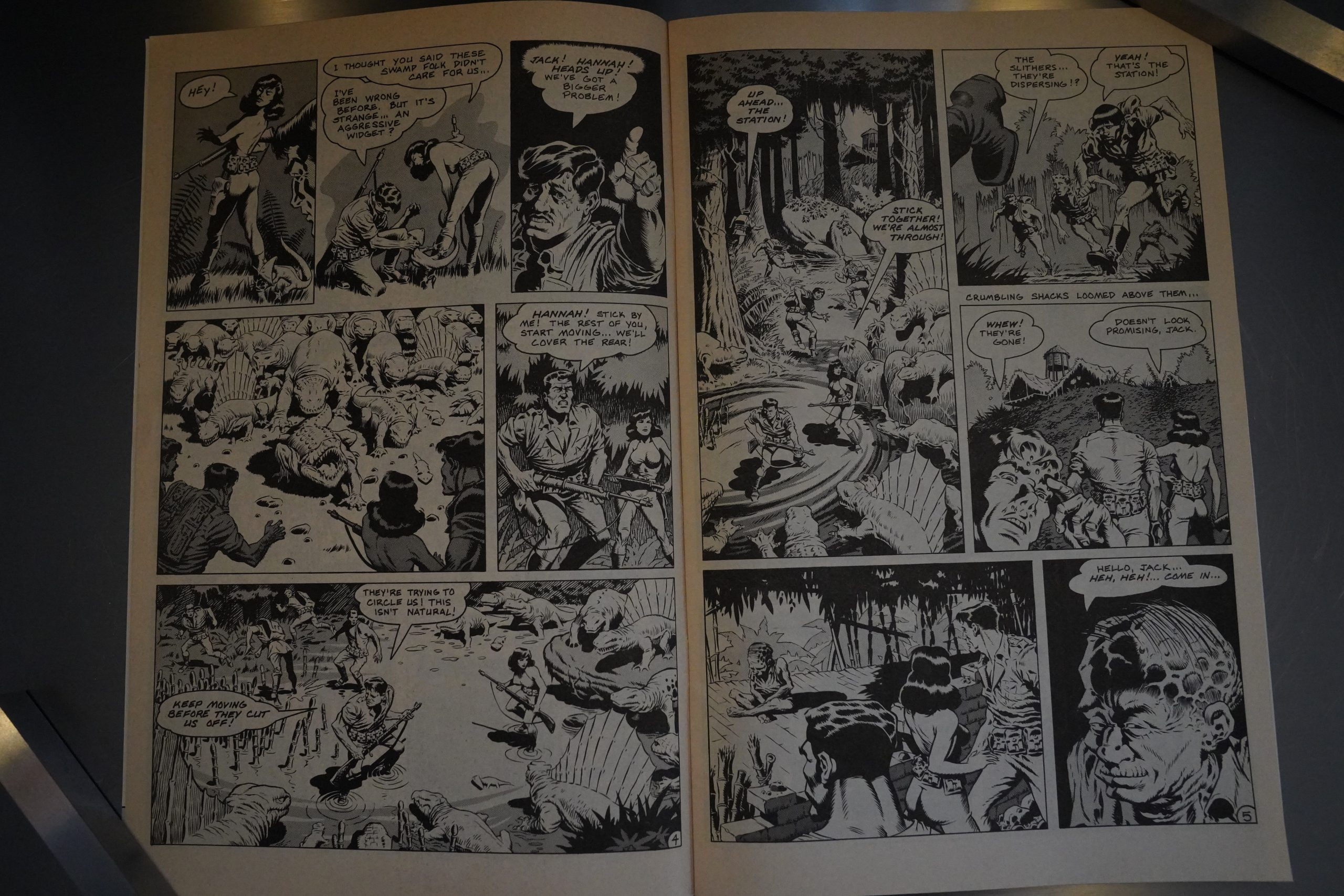

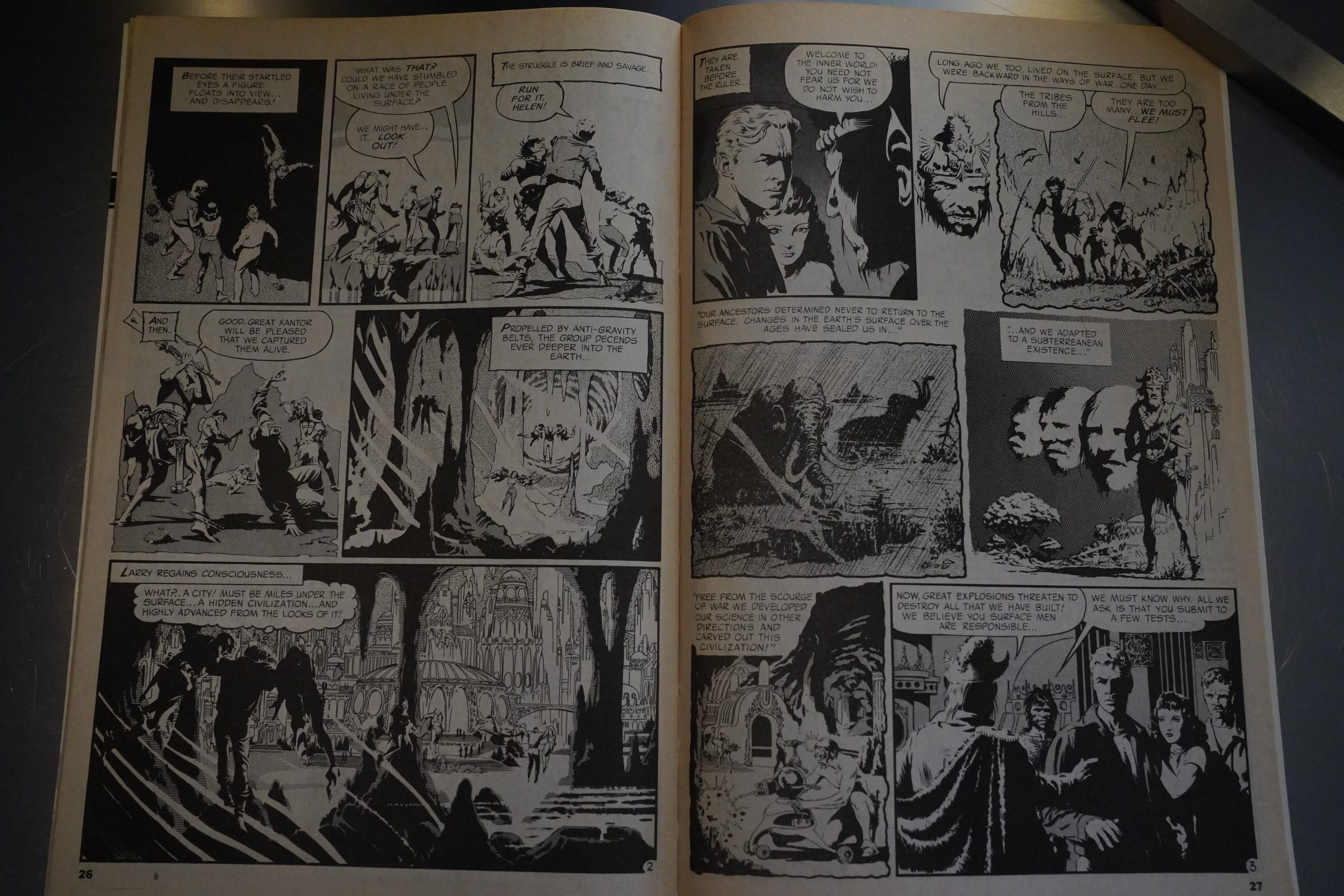

More significantly: Jaxon. He starts his Bultu, The Cosmic Slug serial, which .would run throughout most of Death Rattle’s subsequent run. His artwork really is kinda gorgeous when he wants to, isn’t it?

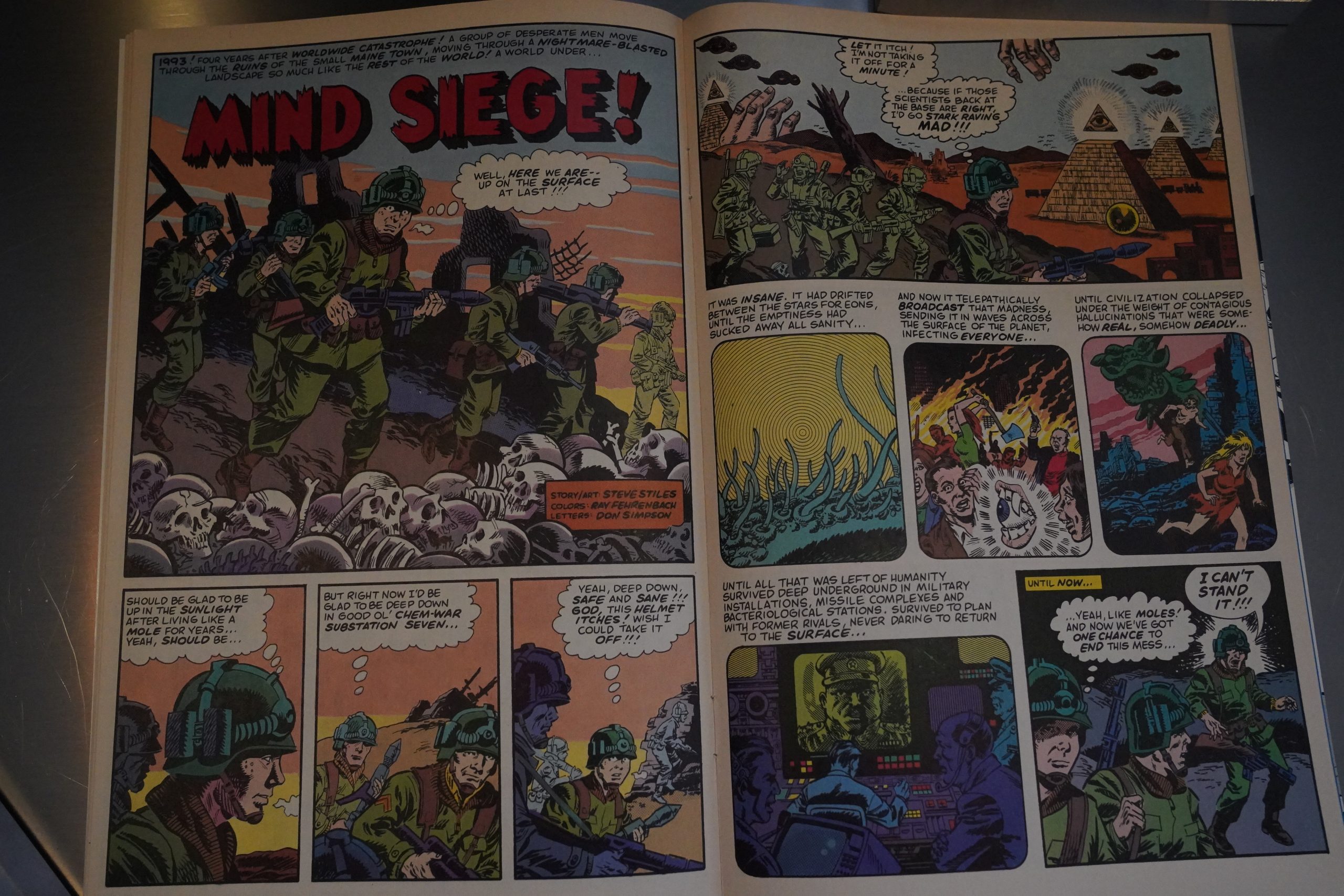

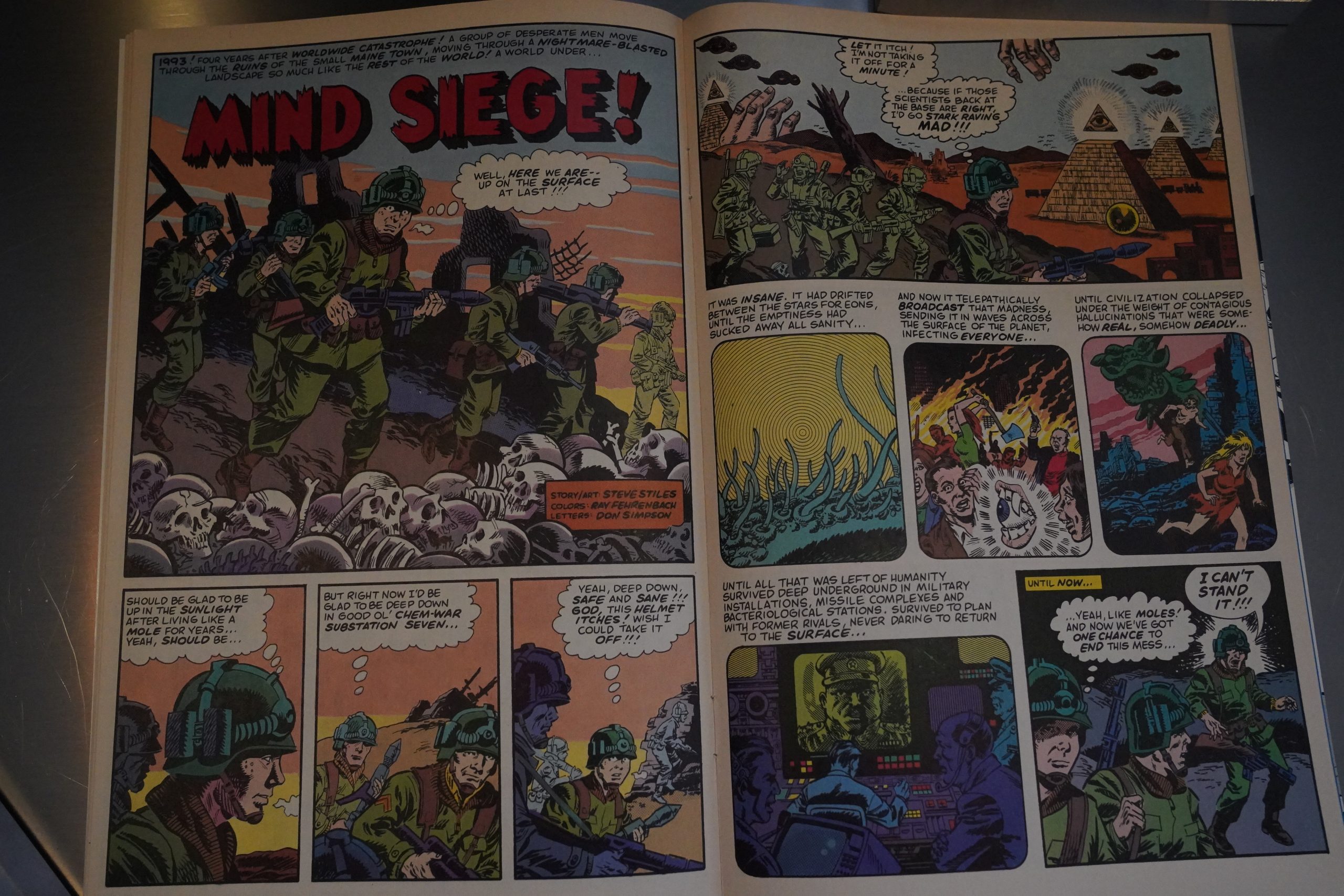

Steve Stiles, a staple of Kitchen’s 70s anthologies, also makes a return, and contributes a bunch of EC-inspired shorts over the rest of the run

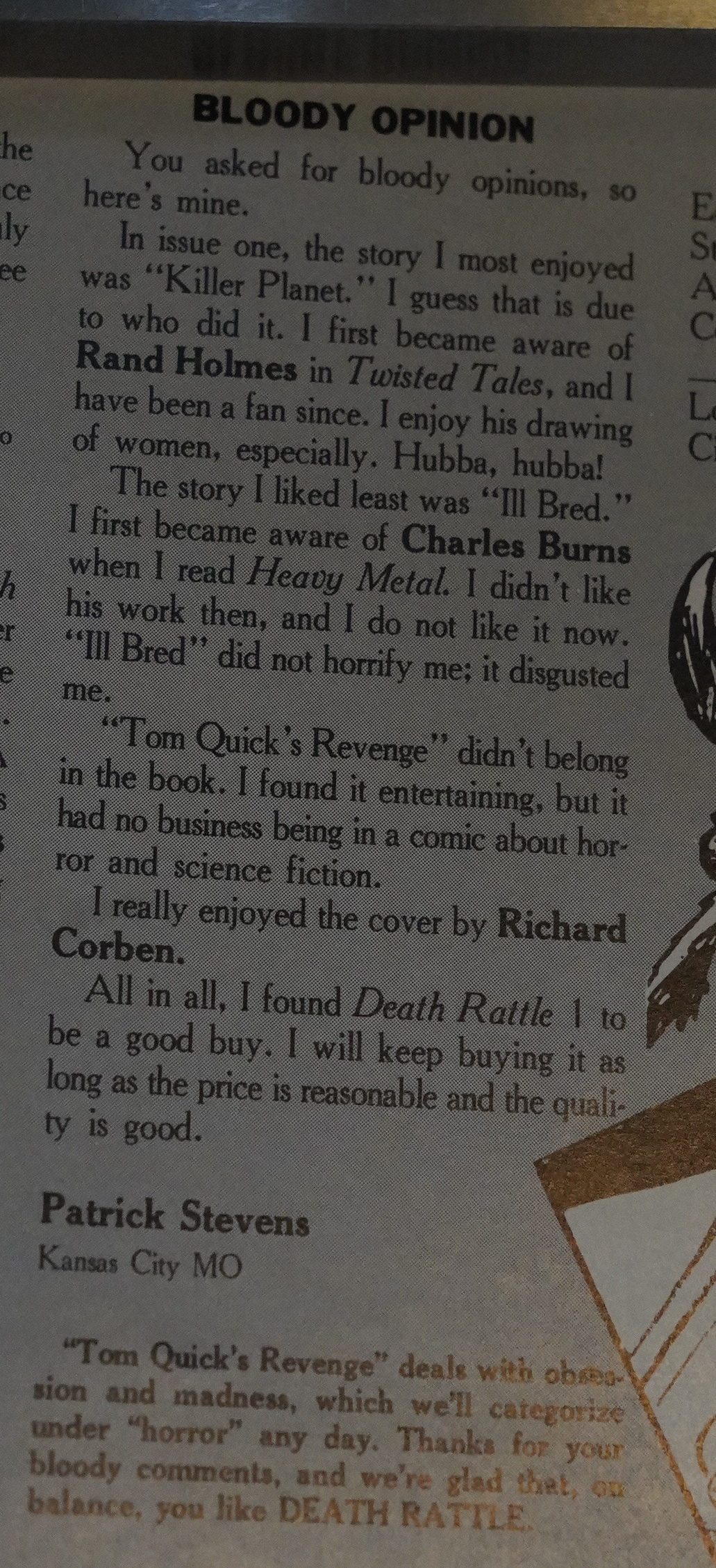

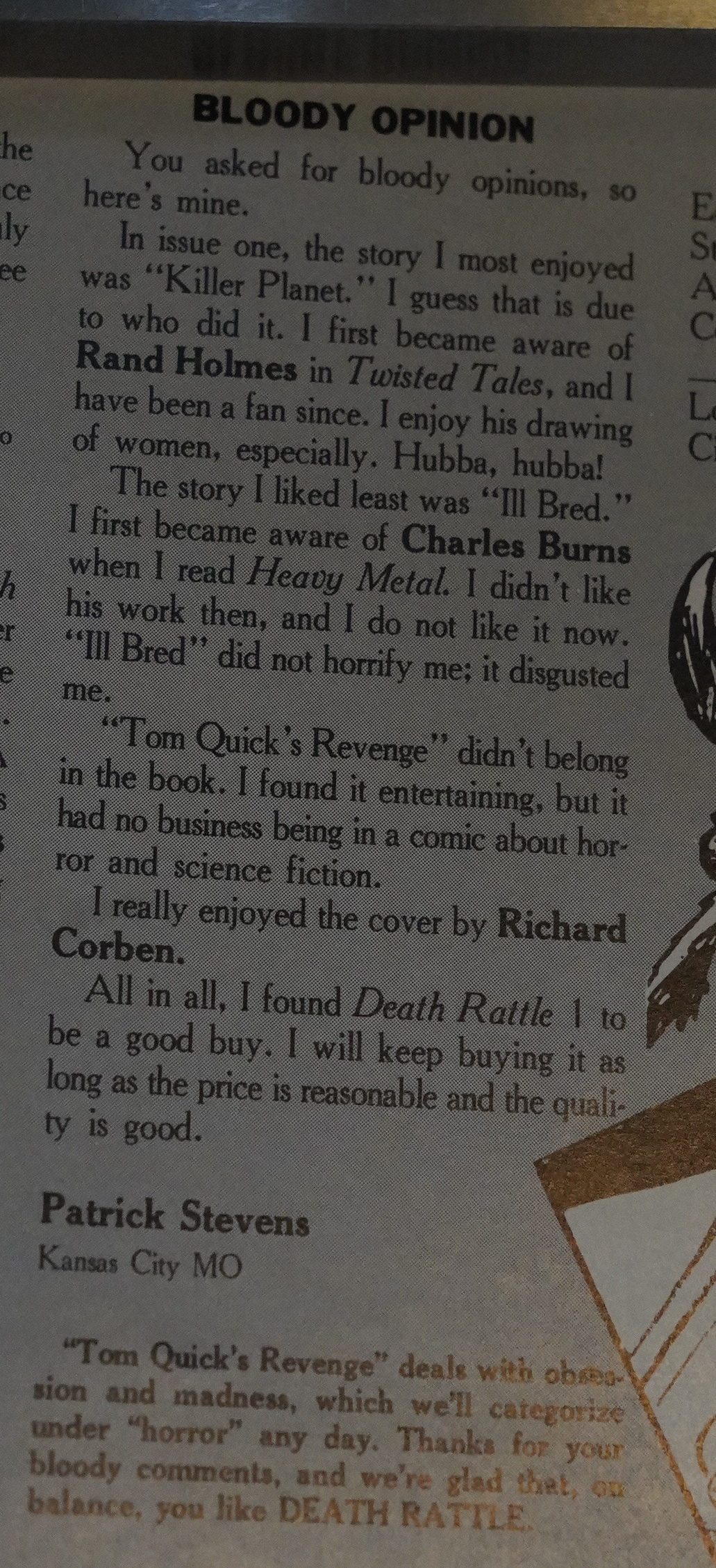

A number of people write in to say that they didn’t much like the Charles Burns story. I guess it unnerved more than it entertained?

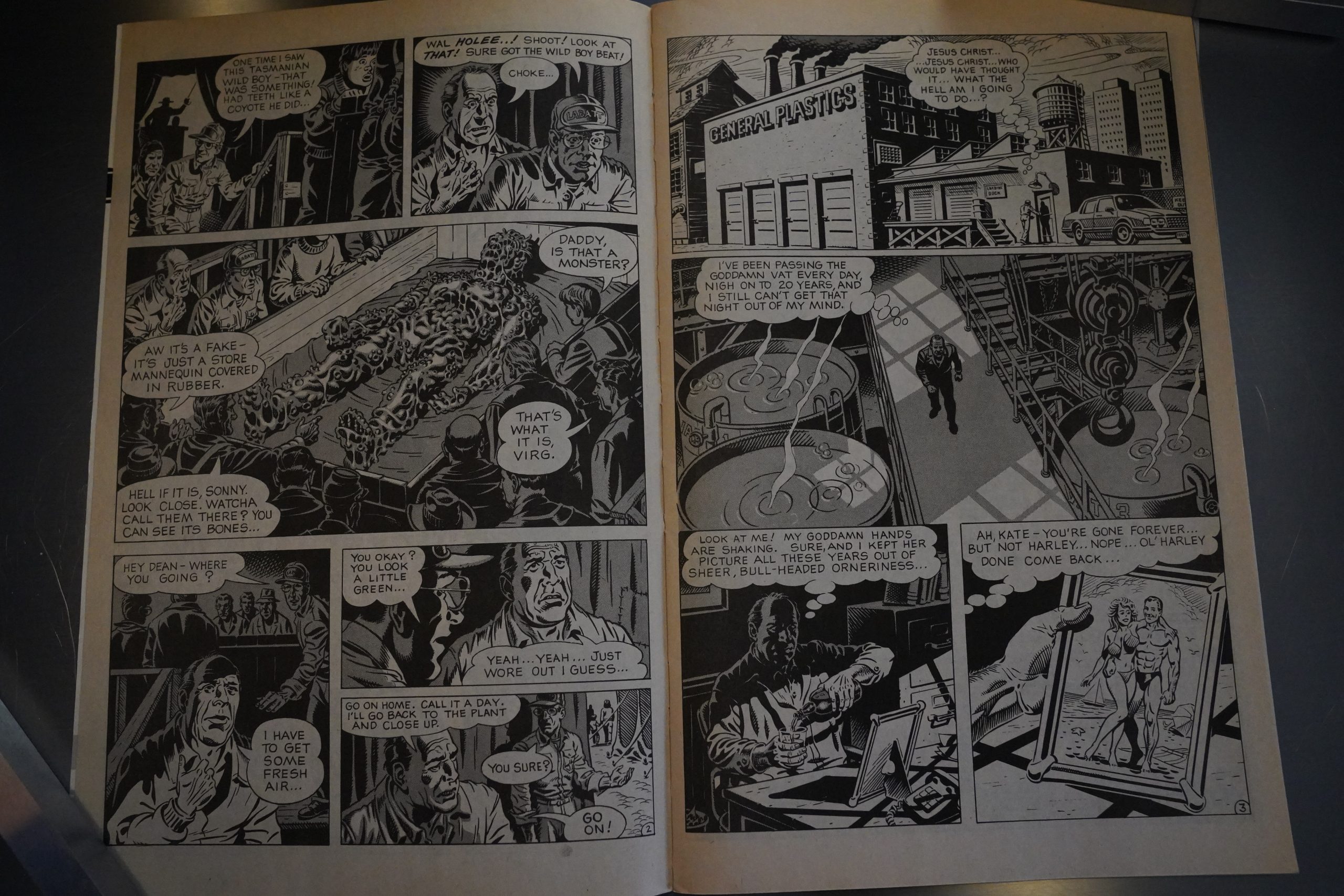

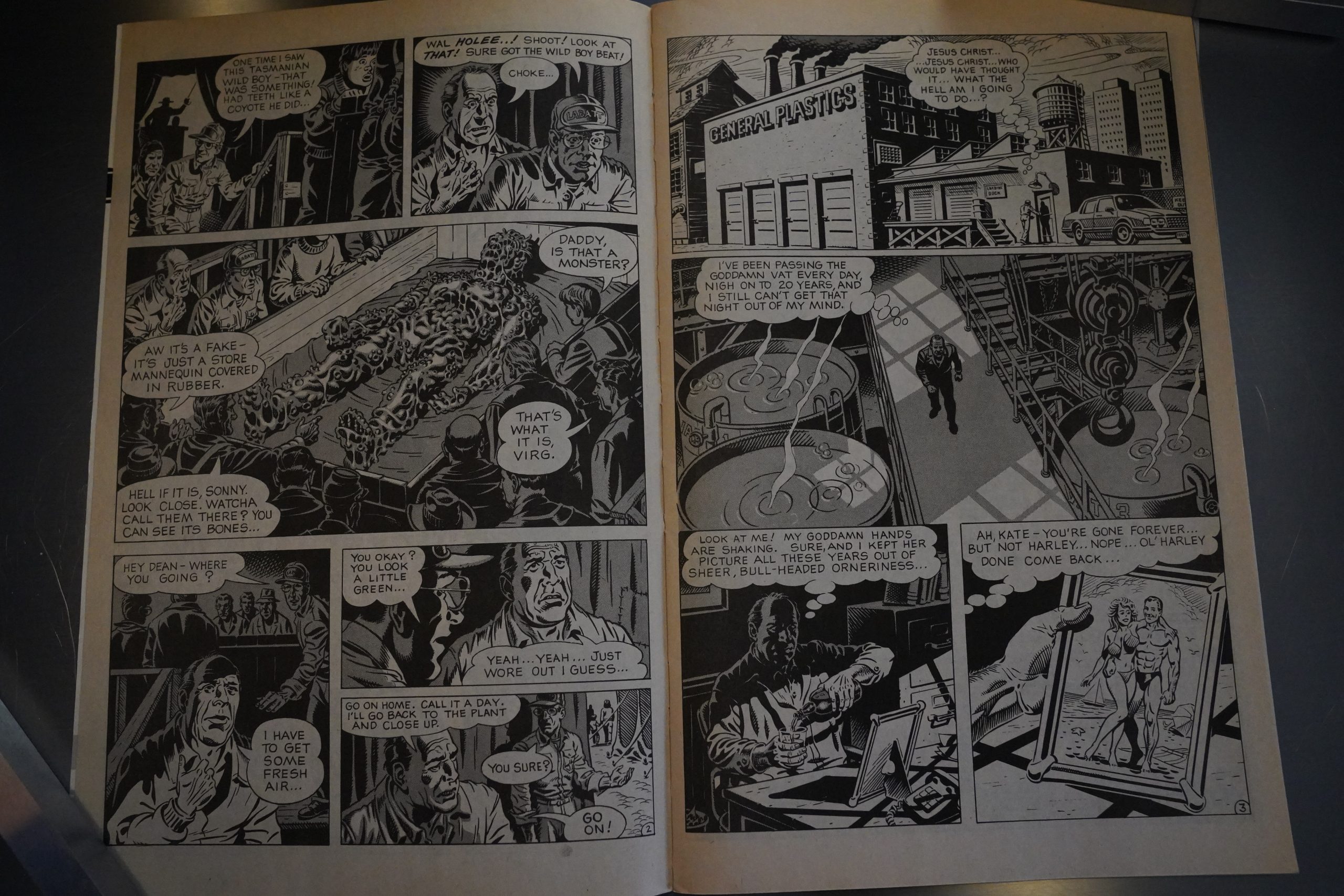

Finally some new Rand Holmes (in a story scripted by Mike Baron). It’s very EC, but more gruesome, so very much on brand.

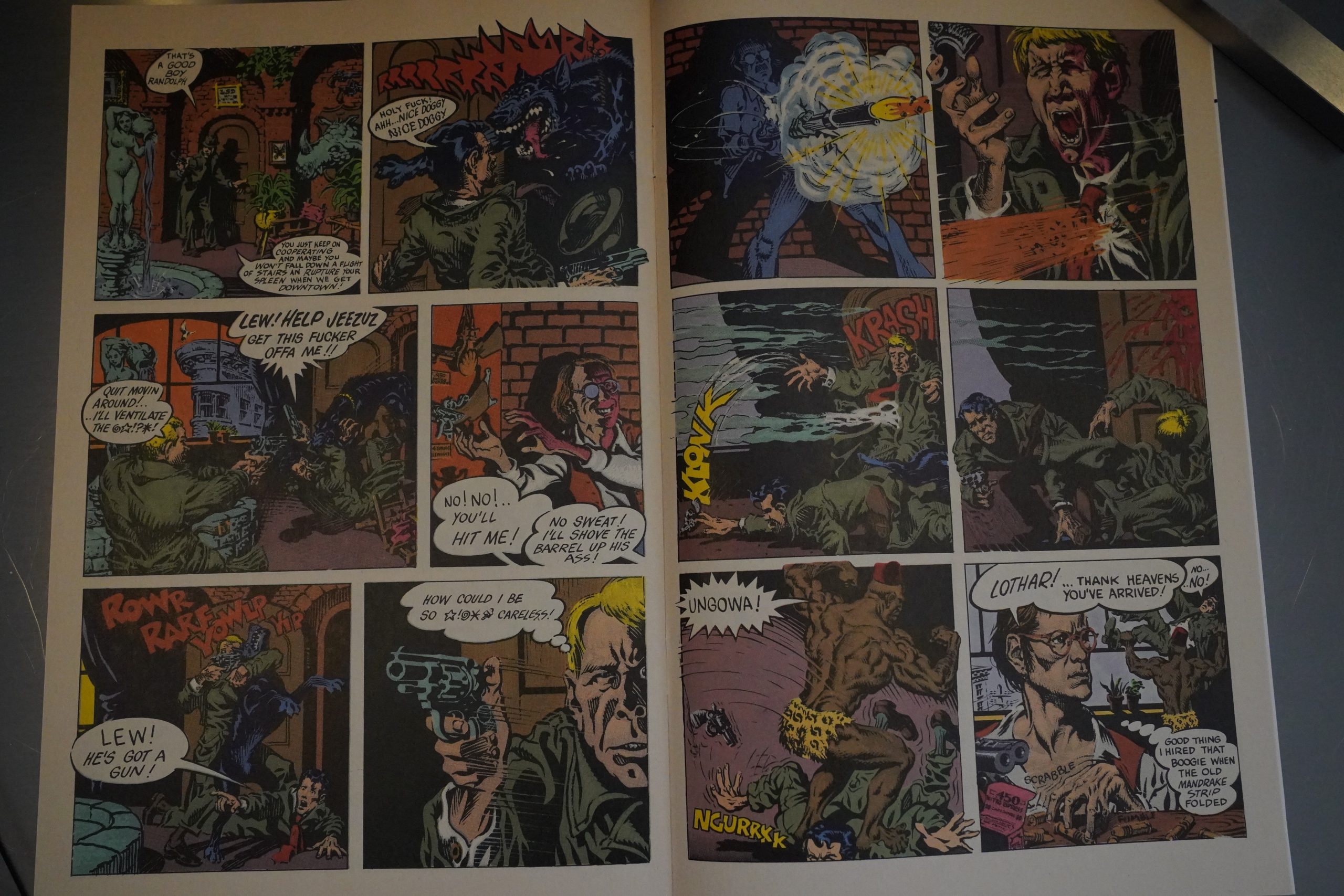

Death Rattle hits a kind of stride — we get a bunch of younger artists, like Sam Kieth and John Holland, contributing really strong stuff. The anthology has a good flow, and most of the stories work.

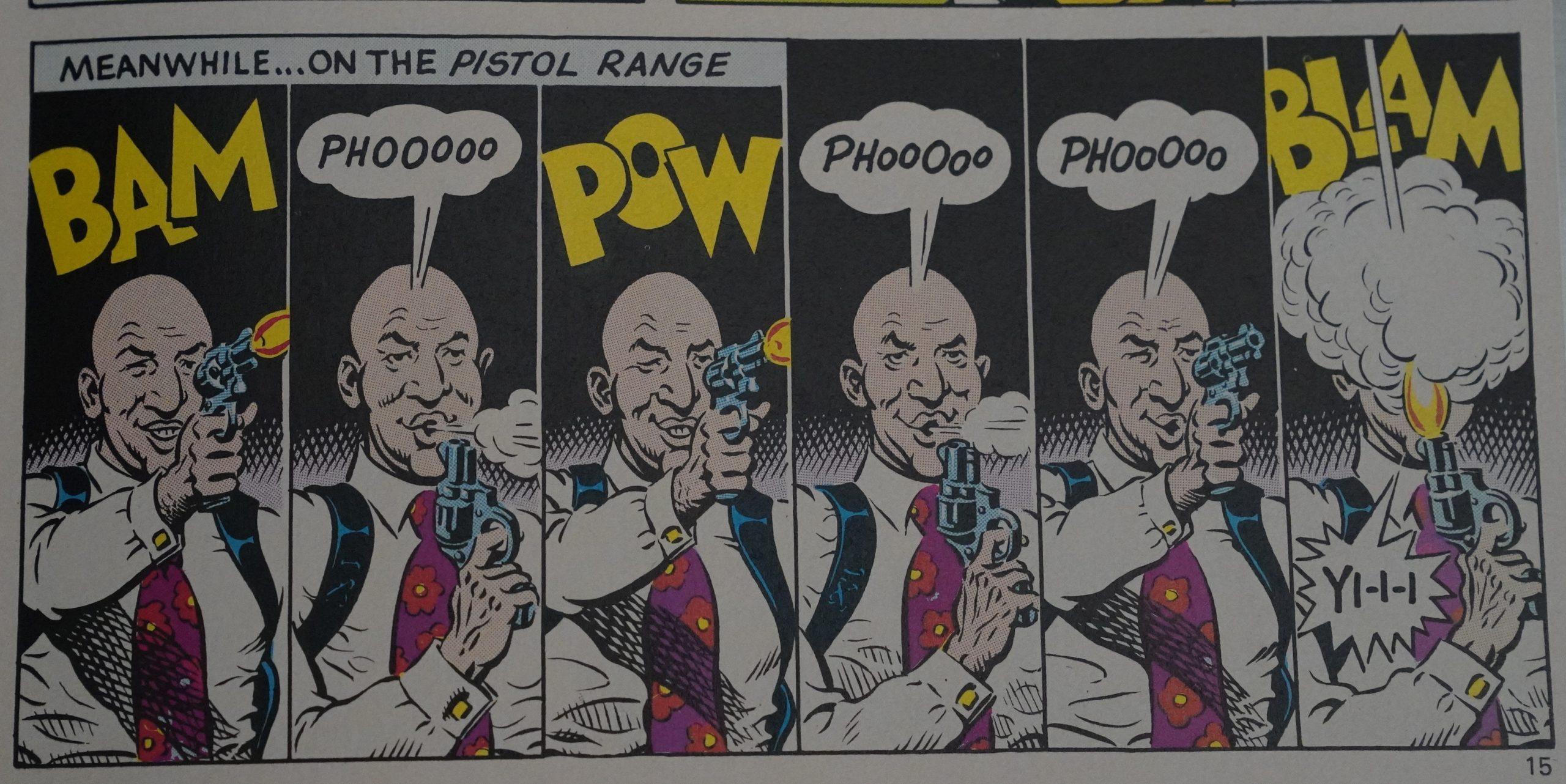

We do get some padding, but it’s superior padding, like Basil Wolverton.

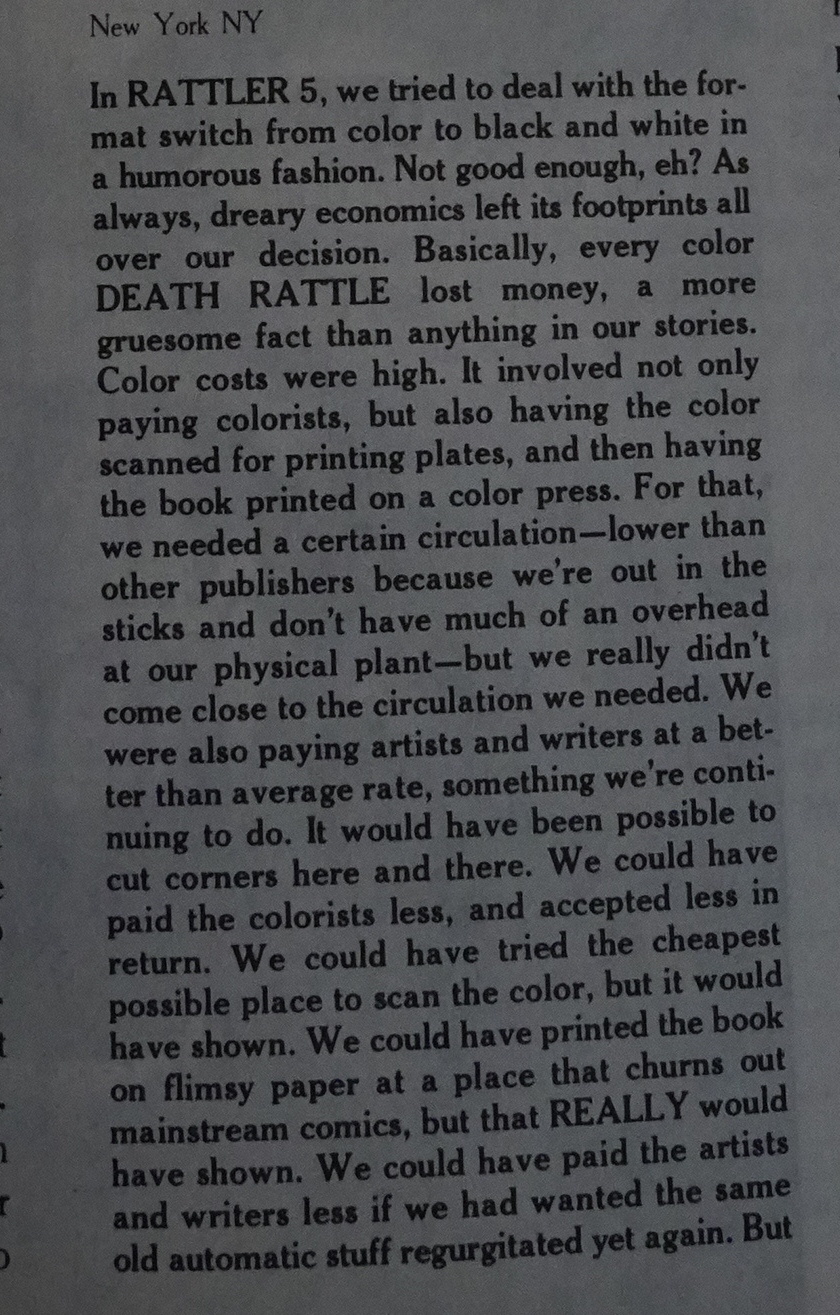

The first half of the 80s was an interesting time for comics. When the direct sales market was created, there was such a hunger for product, any product, that publishers like Pacific and Eclipse were able to publish some pretty quirky and unusual books, in colour with good production values, and still make some money. After a few years, apparently the comics buying public had enough of that stuff, and reverted to only buying Marvel and DC super-hero comics again, but those few years were fun.

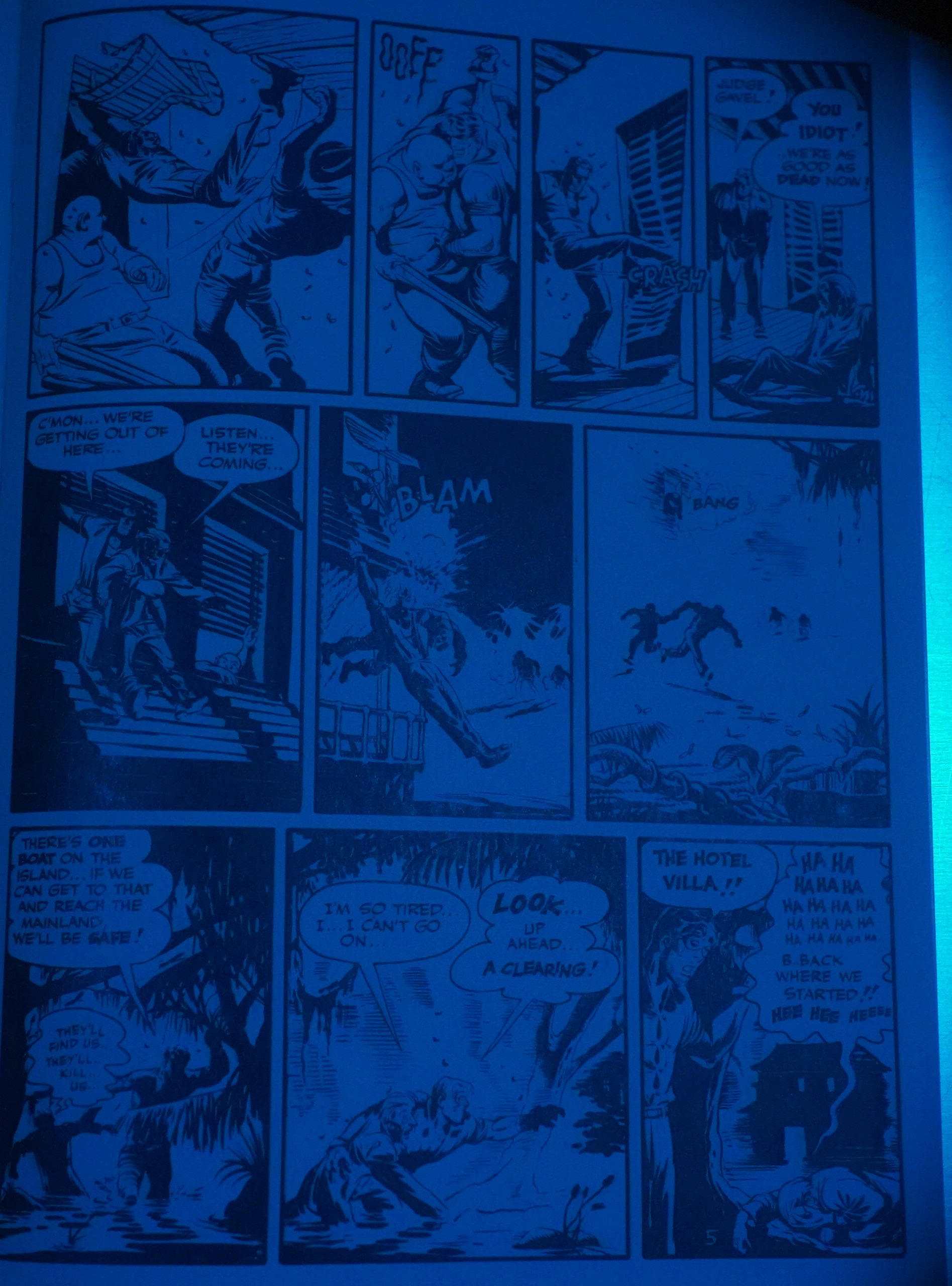

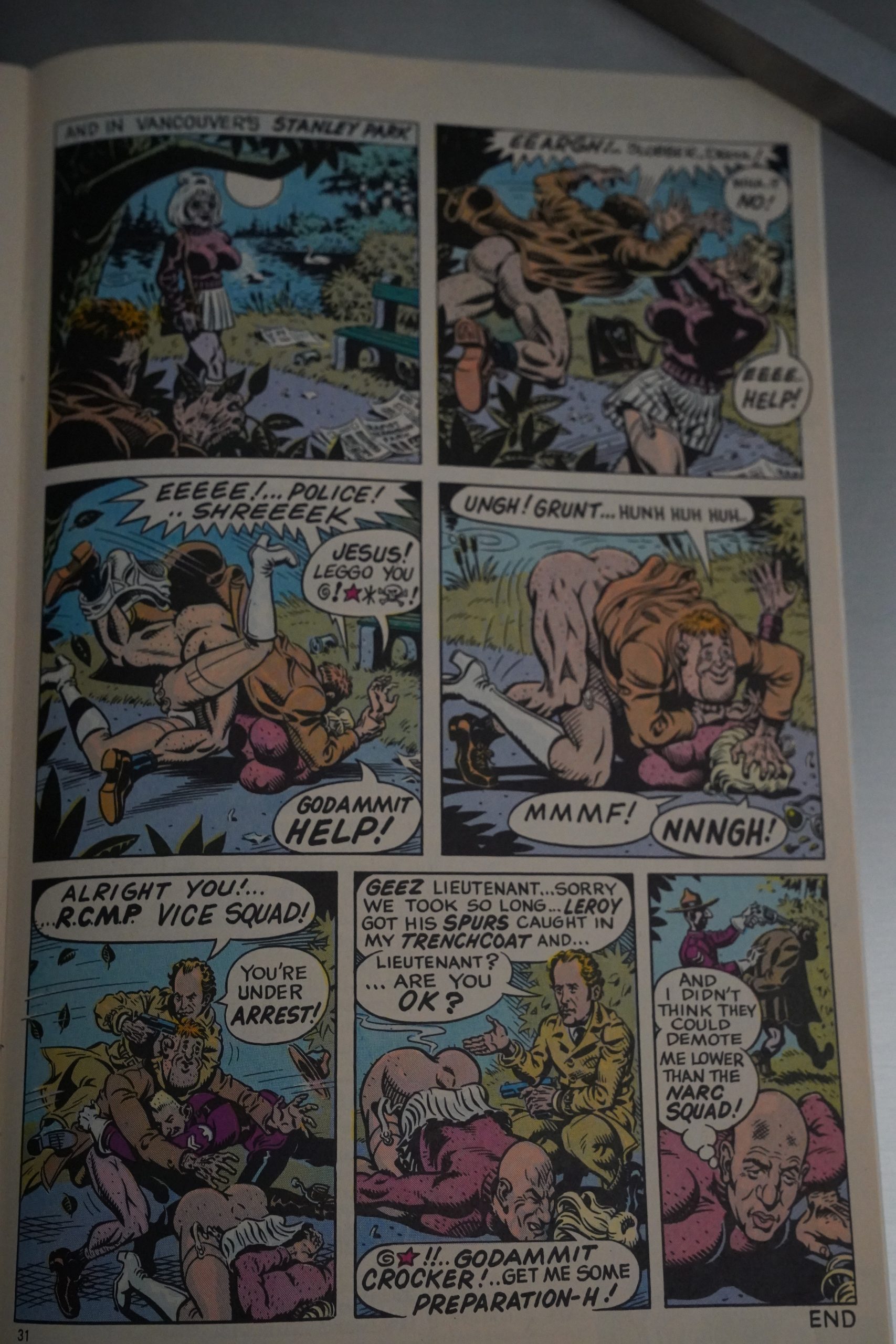

So with the sixth issue, the book switches to black and white, because sales were just too low. But horror looks good in black and white, too. Here’s Tom Veitch and Steven Bissette above, doing a twisty horror thing.

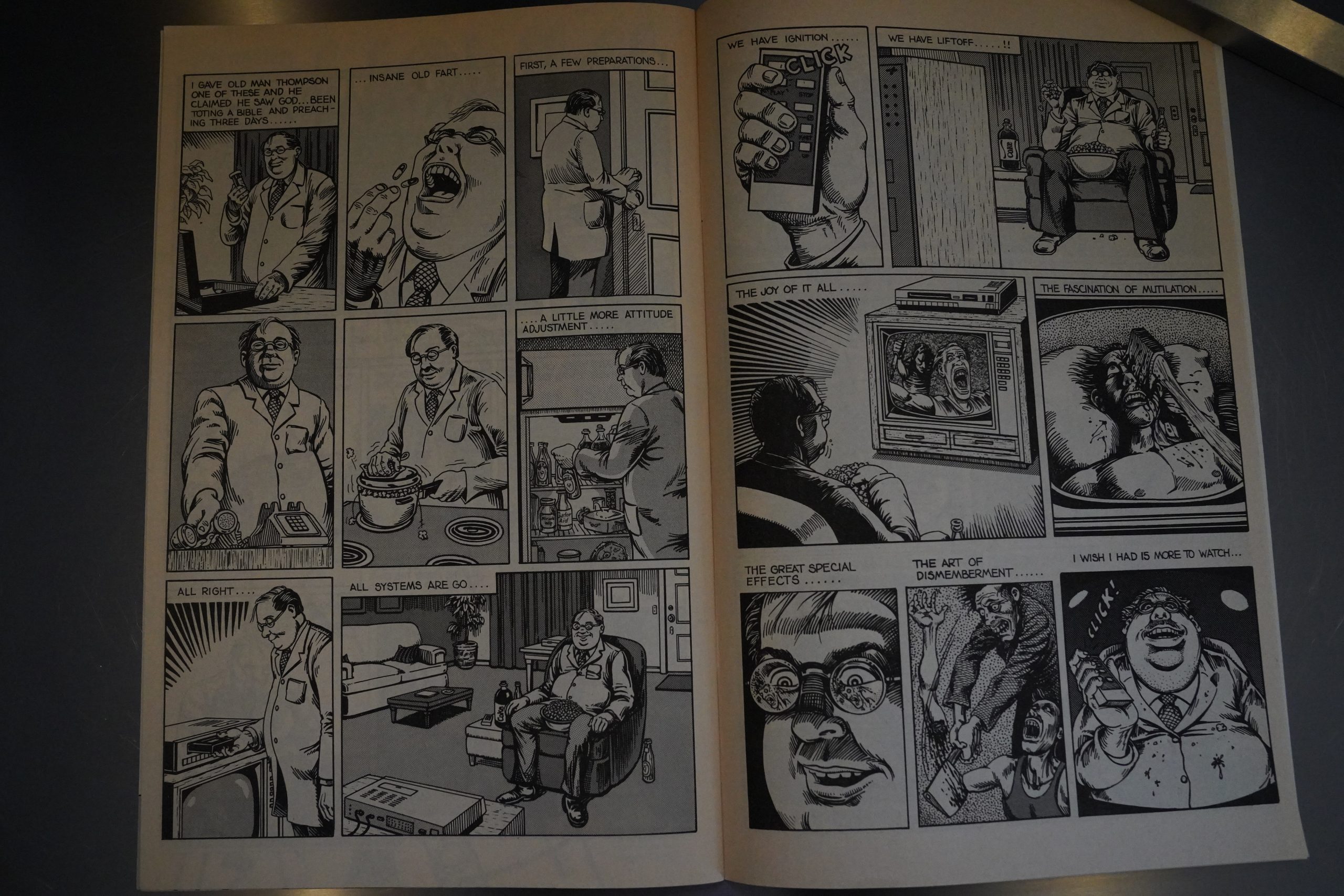

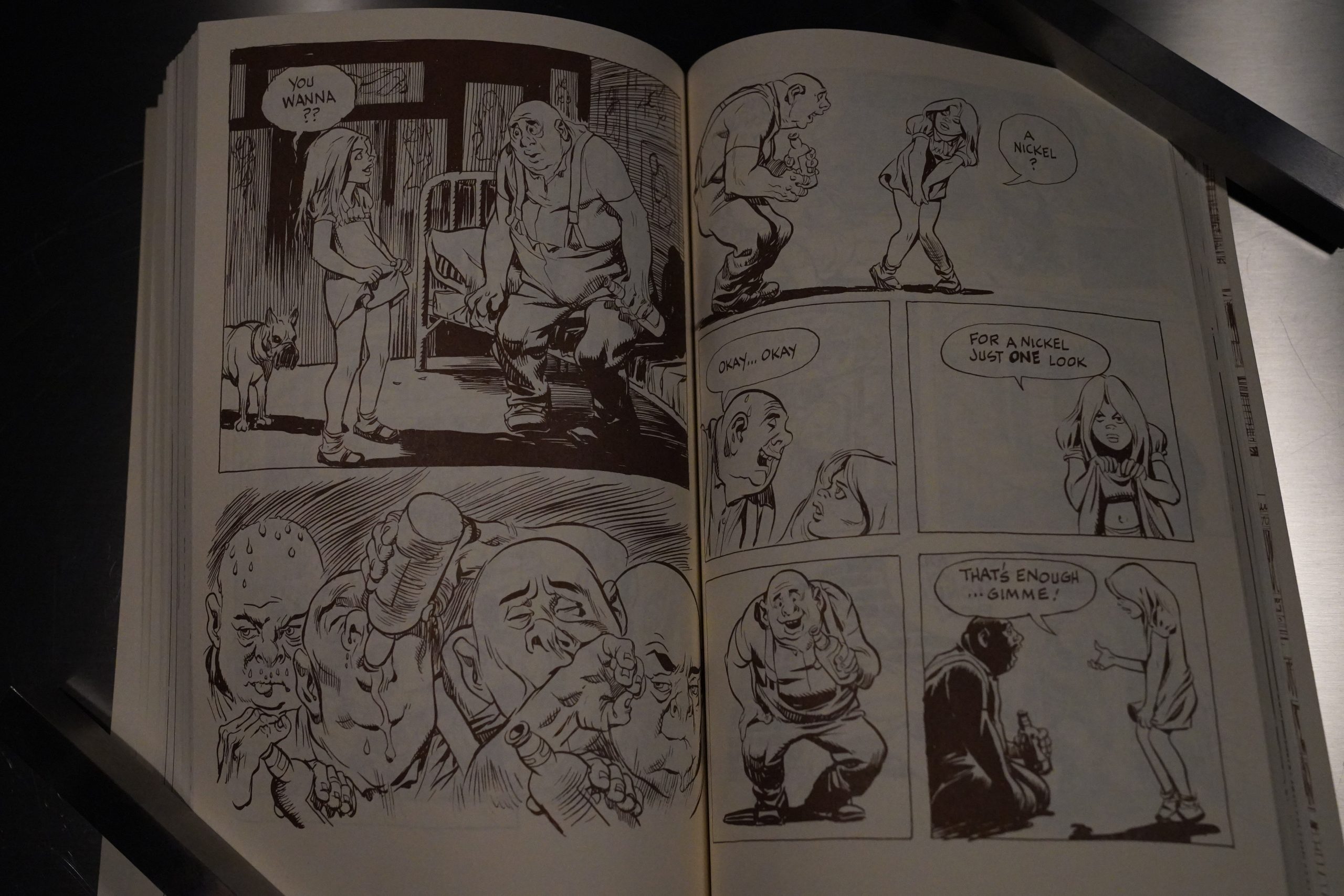

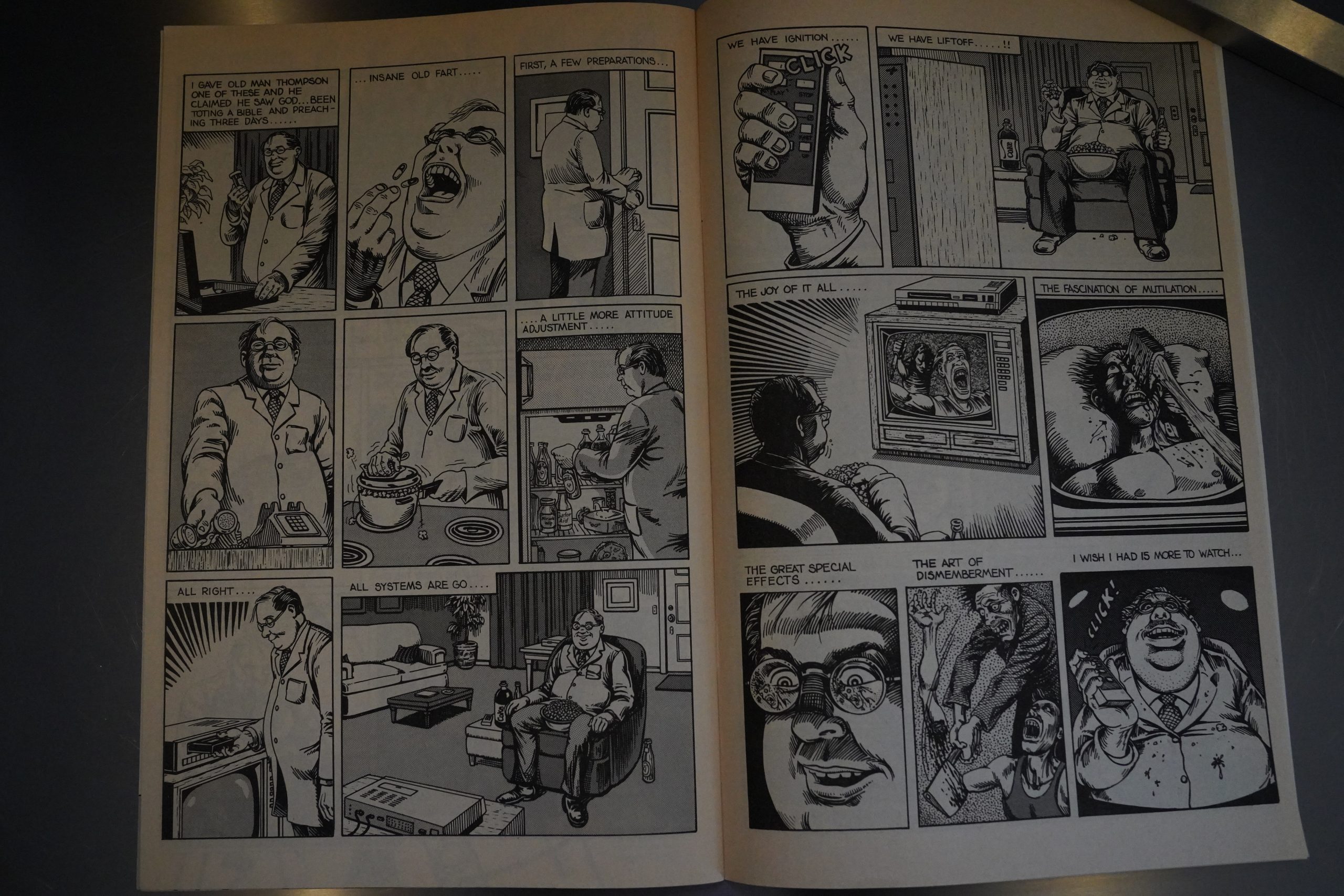

Rand Holmes and Jan Strnad explain to us that fat people are monsters.

And Jaxon takes to black and white in his stride.

It’s still a really entertaining anthology.

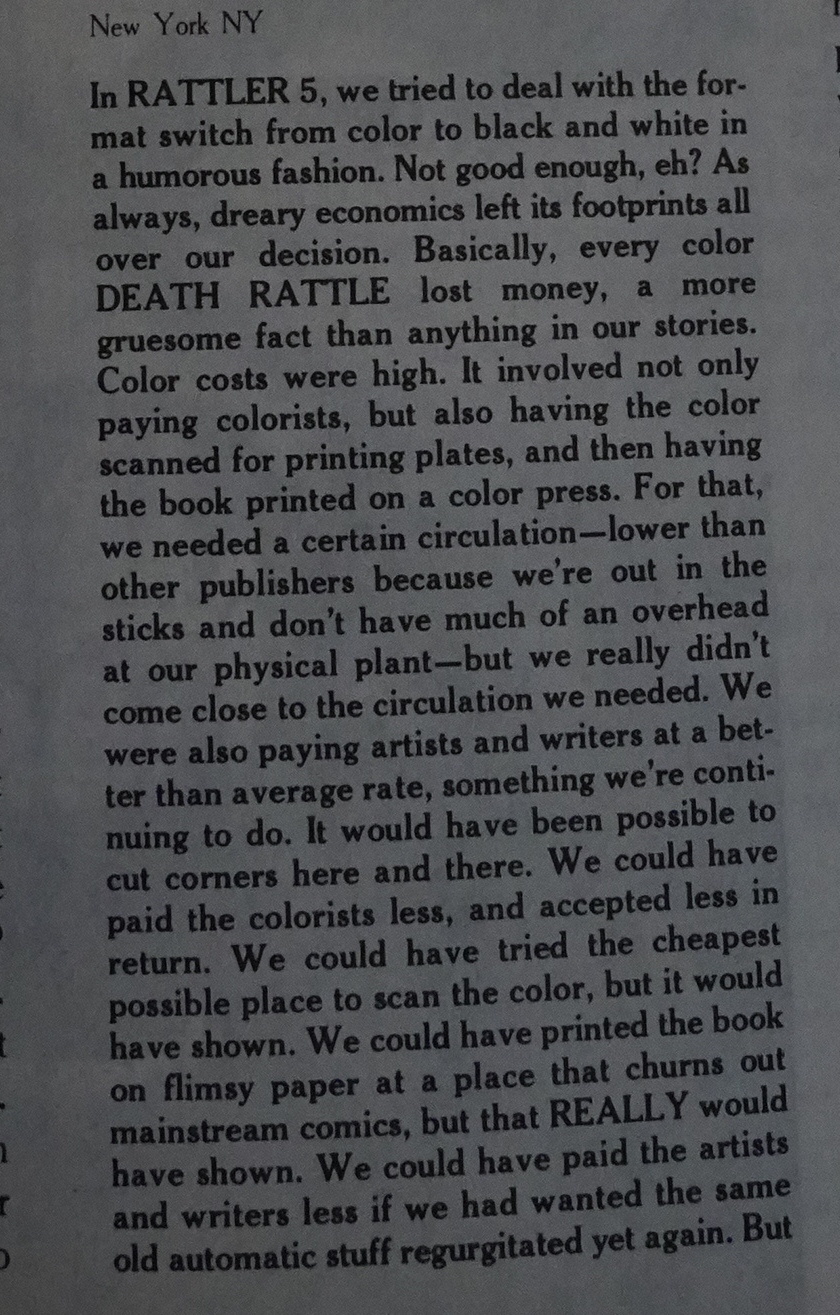

Kitchen explains that they lost money on every colour issue of Death Rattle? Uhm… well, if he says so.

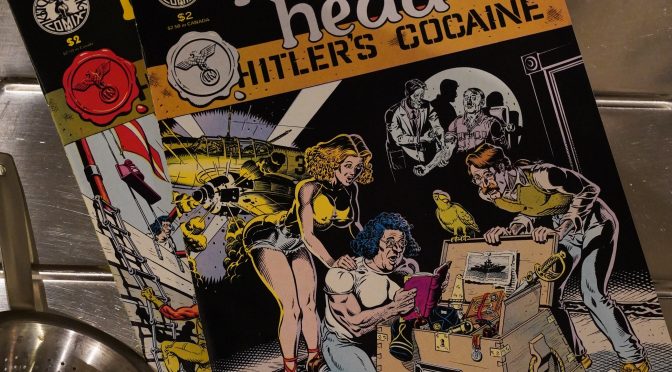

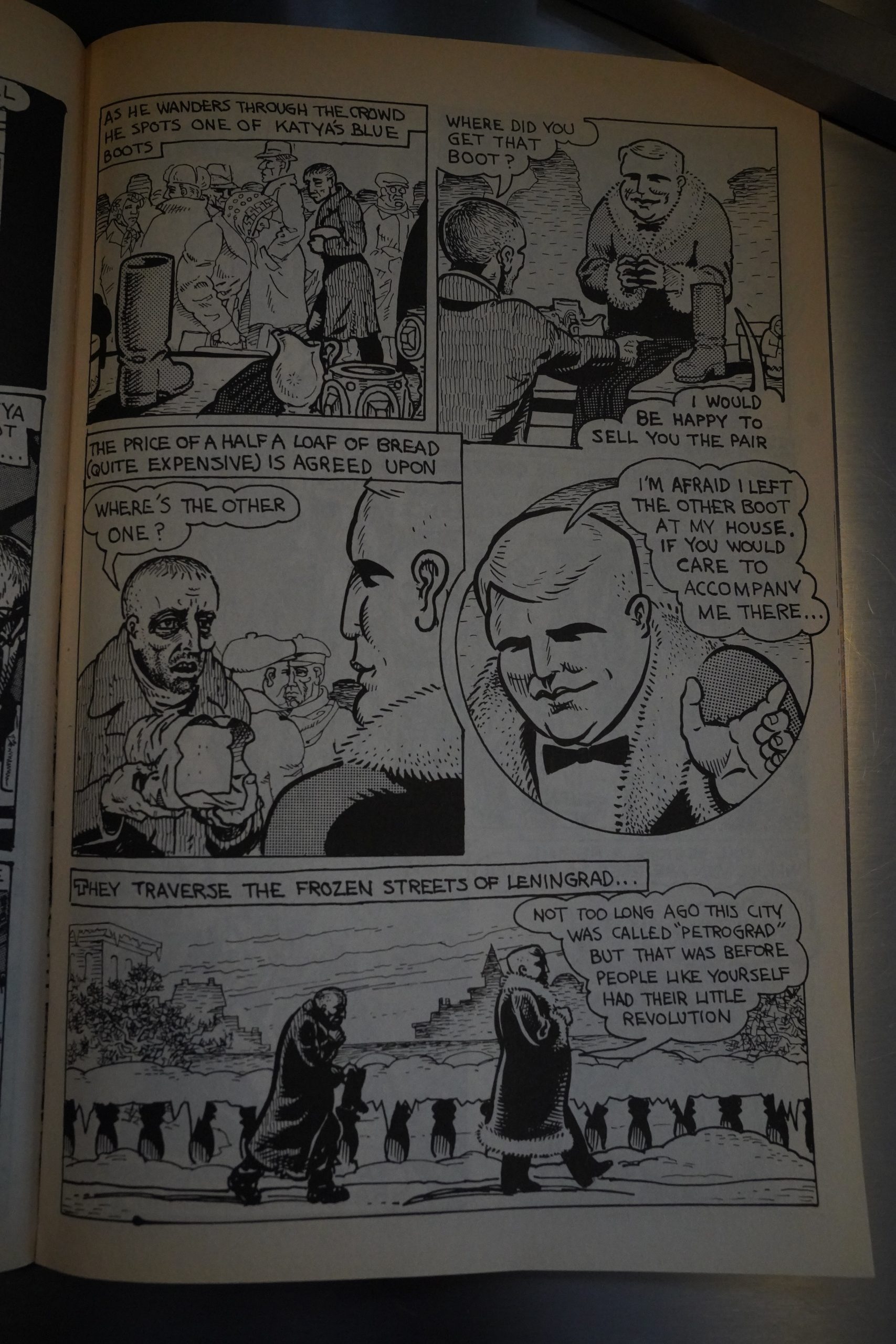

Spain! Wow. (It’s one of those “Nazis are bad” stories, which is always good.)

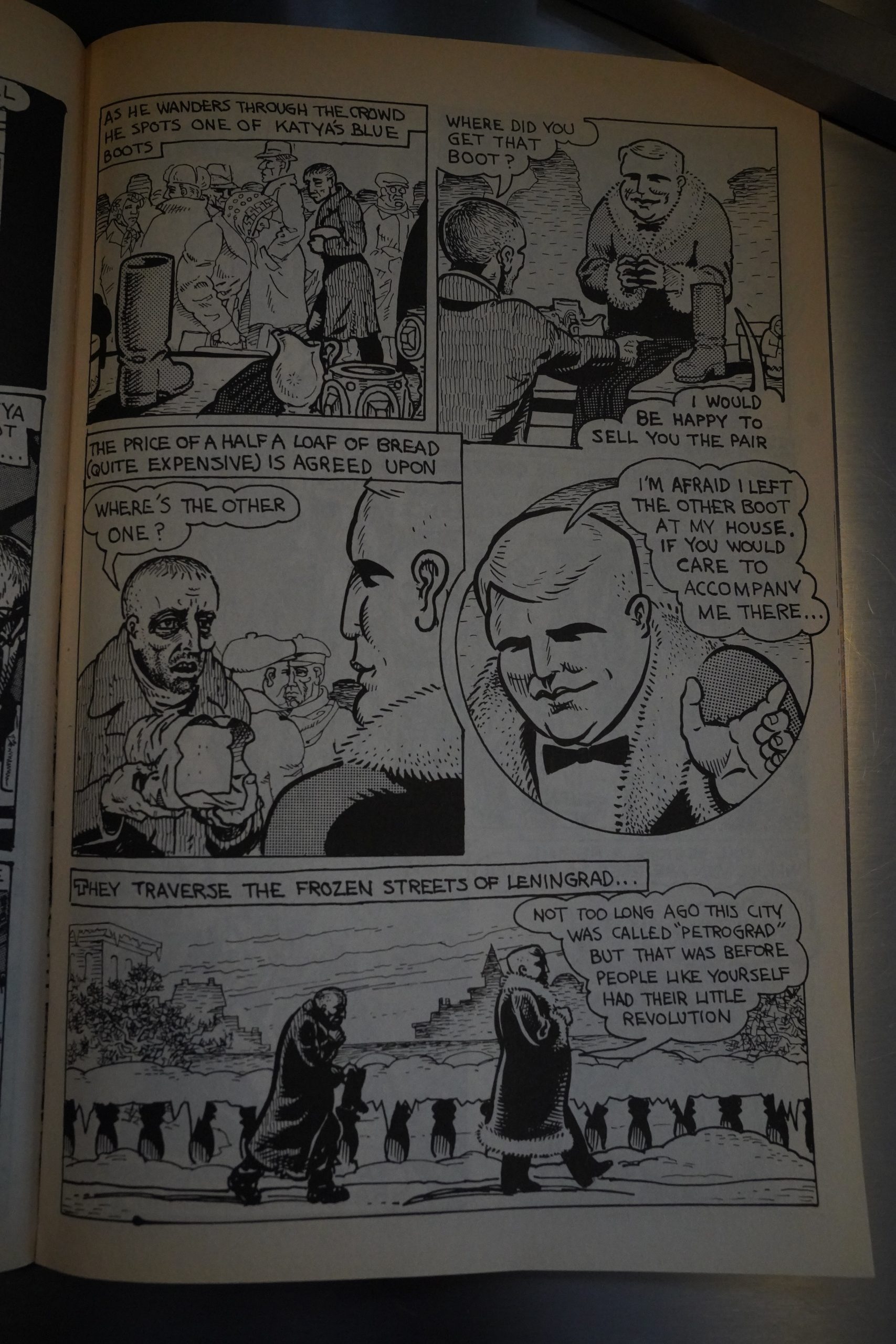

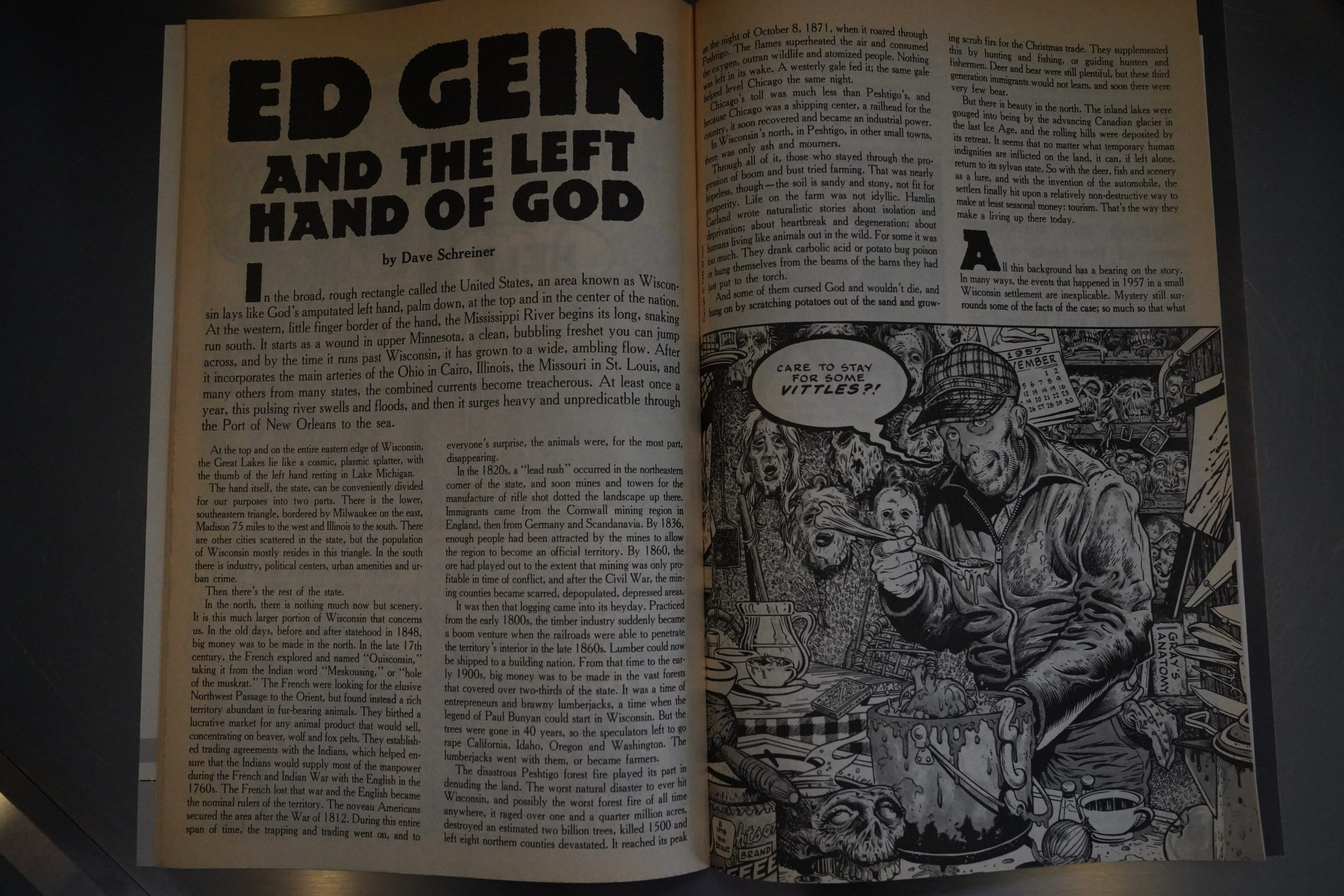

One frustrating thing about many earlier Kitchen anthologies was the way he’d just drop in bits from other anthologies he’d also published. So here we get a long article about Ed Gein… that had run in Weird Trips earlier, I think?

I know that indie comic books usually hover on the brink of losing money, so you can’t be too annoyed with Kitchen doing this: Getting some pages of good comics is better than getting no pages, right?

Mark Schultz’ Xenozoic Tales makes it debut here, which makes this issue an expensive one on ebay…

Kenneth Whitfield and Dan Burr gives an accurate portrayal of the readers of the comic.

There’s definitely fewer well-known names in the anthology as the issues roll by. Here’s Nick Burns and Joseph Schmough — but it looks pretty interesting, doesn’t it? And it’s a good little horror story.

Note that the paper has gone from nice and white to newsprint, so I guess that’s another cost saving thing.

The series does have a strong identity, though — mainly through the many stories illustrated by Rand Holmes (and written various people), and, of course, the Jaxon serial.

But the fillers keep coming.

And on and on. I think the tenth issue had eight pages of new comics and the rest was filler? Text pages and…

… this Williamson (and a cast of thousands) thing from the 50s that was redone and printed in Witzend originally.

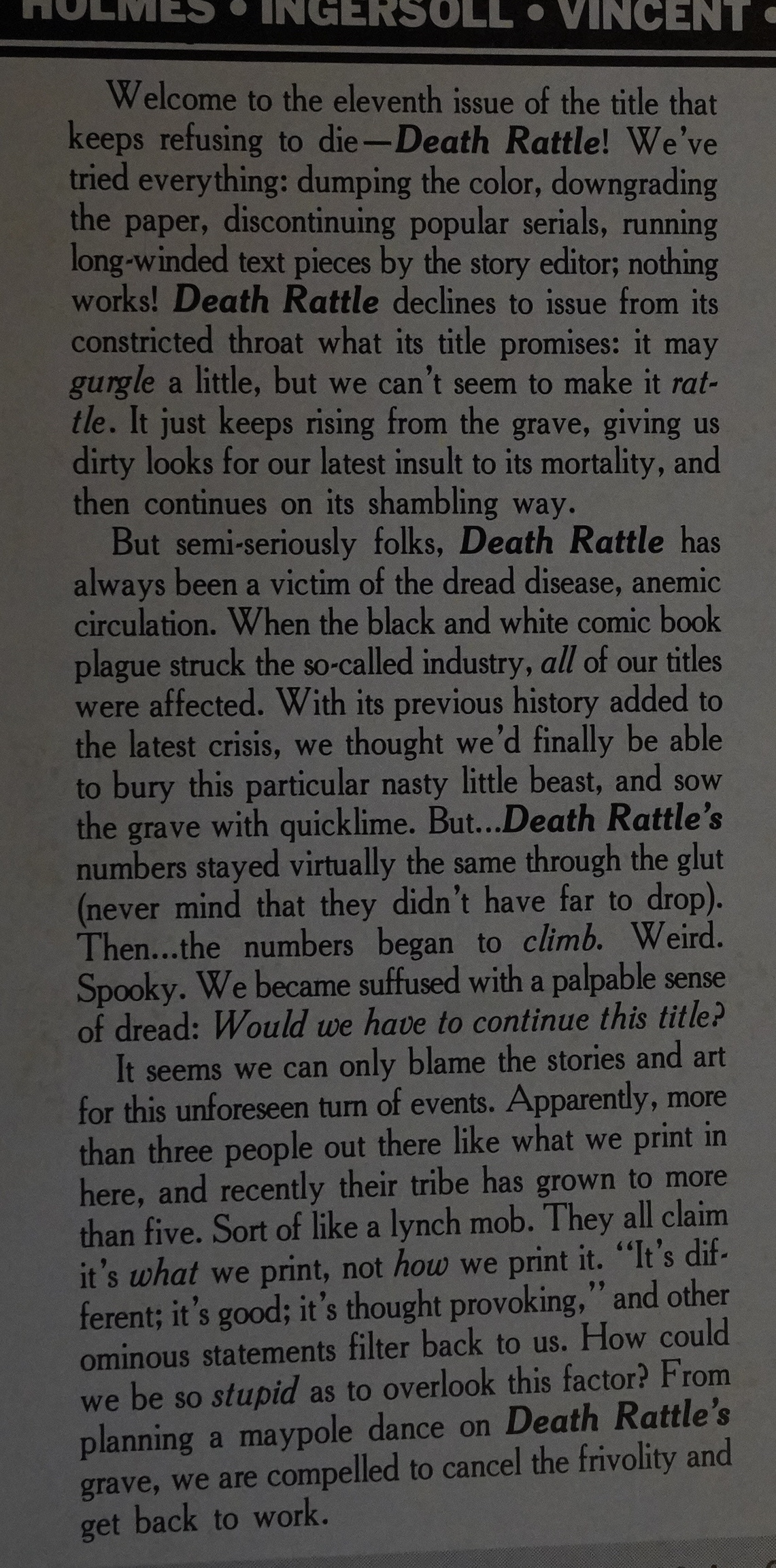

We get the explanation next issue — they had planned on cancelling the series with the eleventh issue, so they had presumably stopped taking in new submissions? But! The circulation unexpectedly increased, so they’re continuing the series.

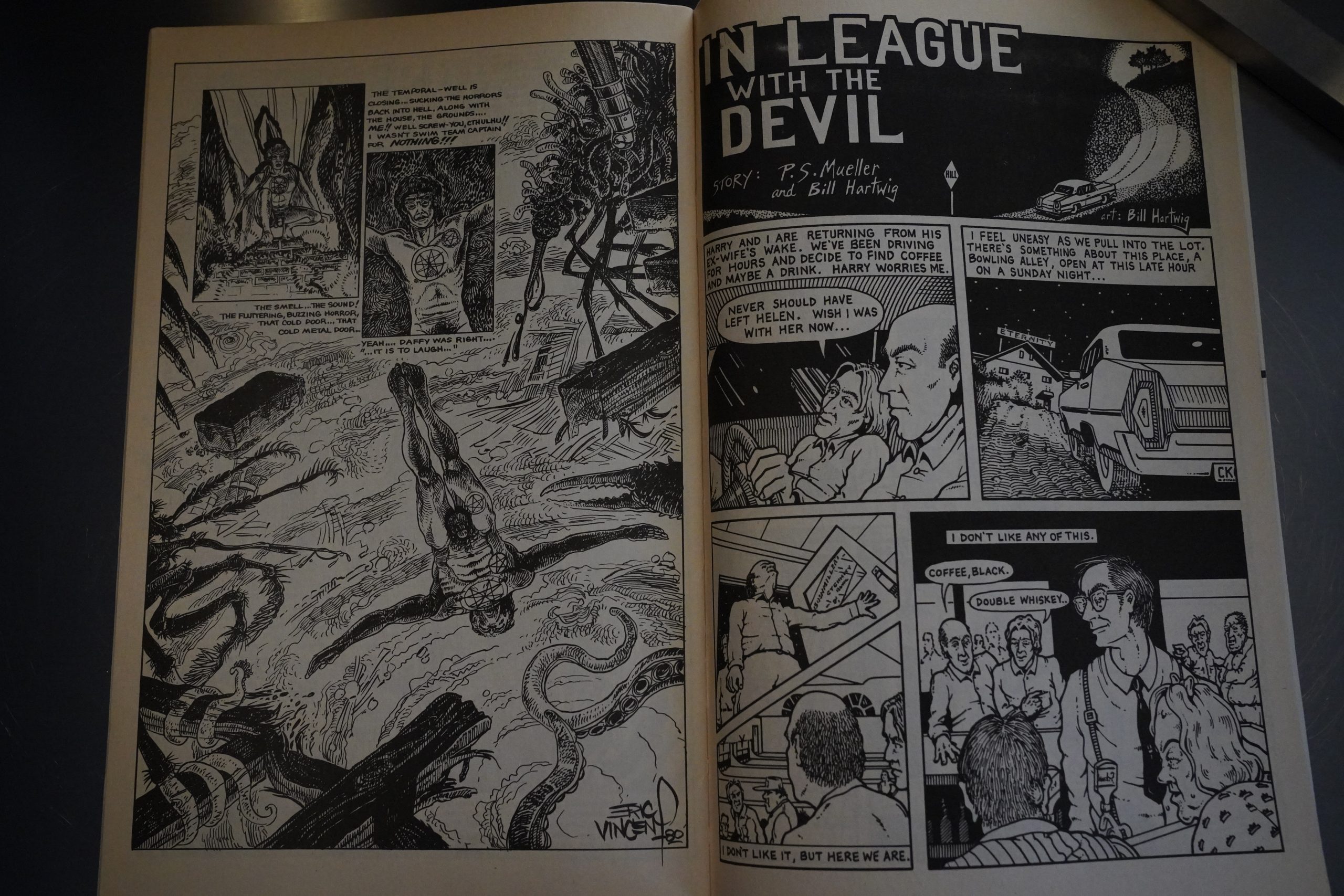

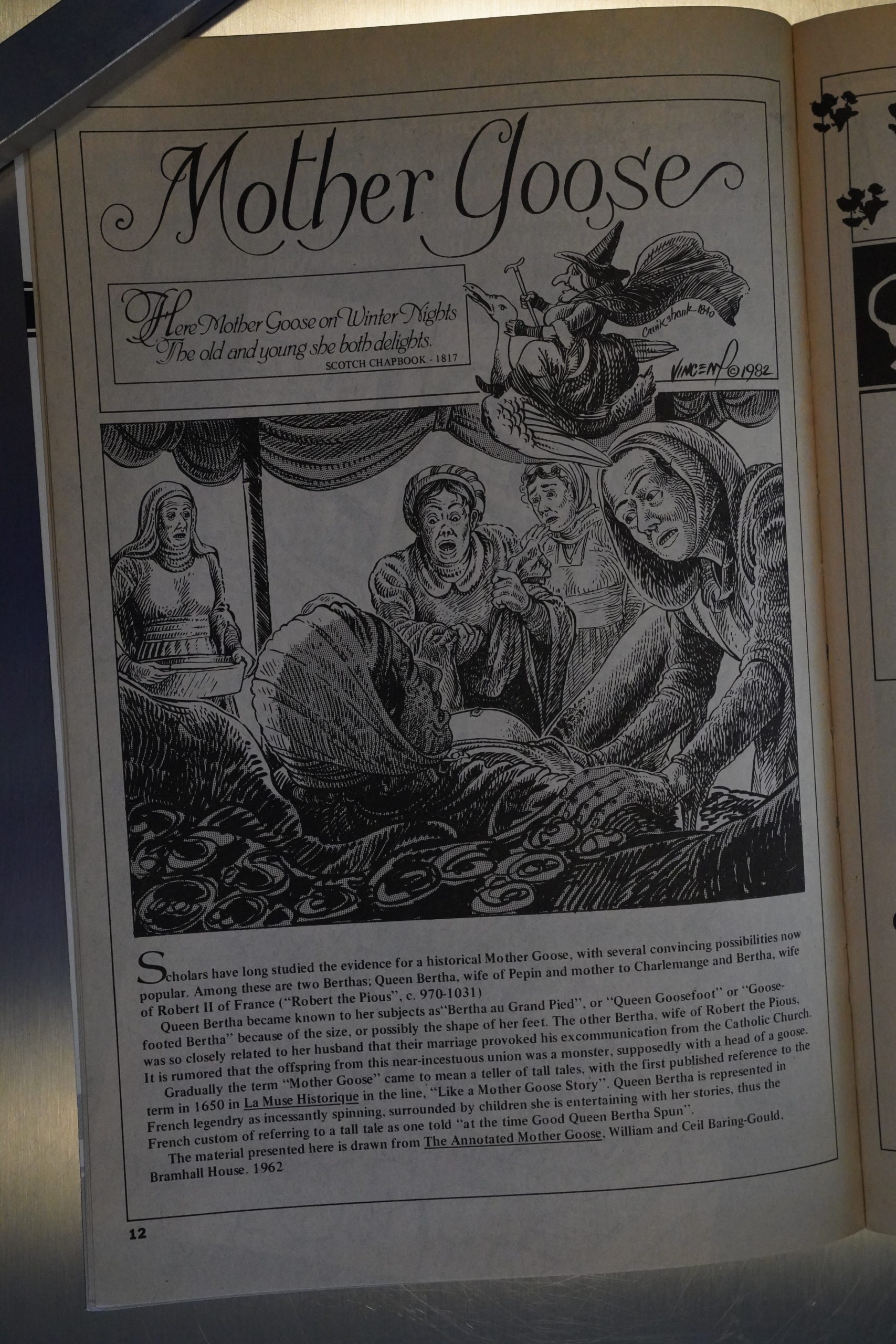

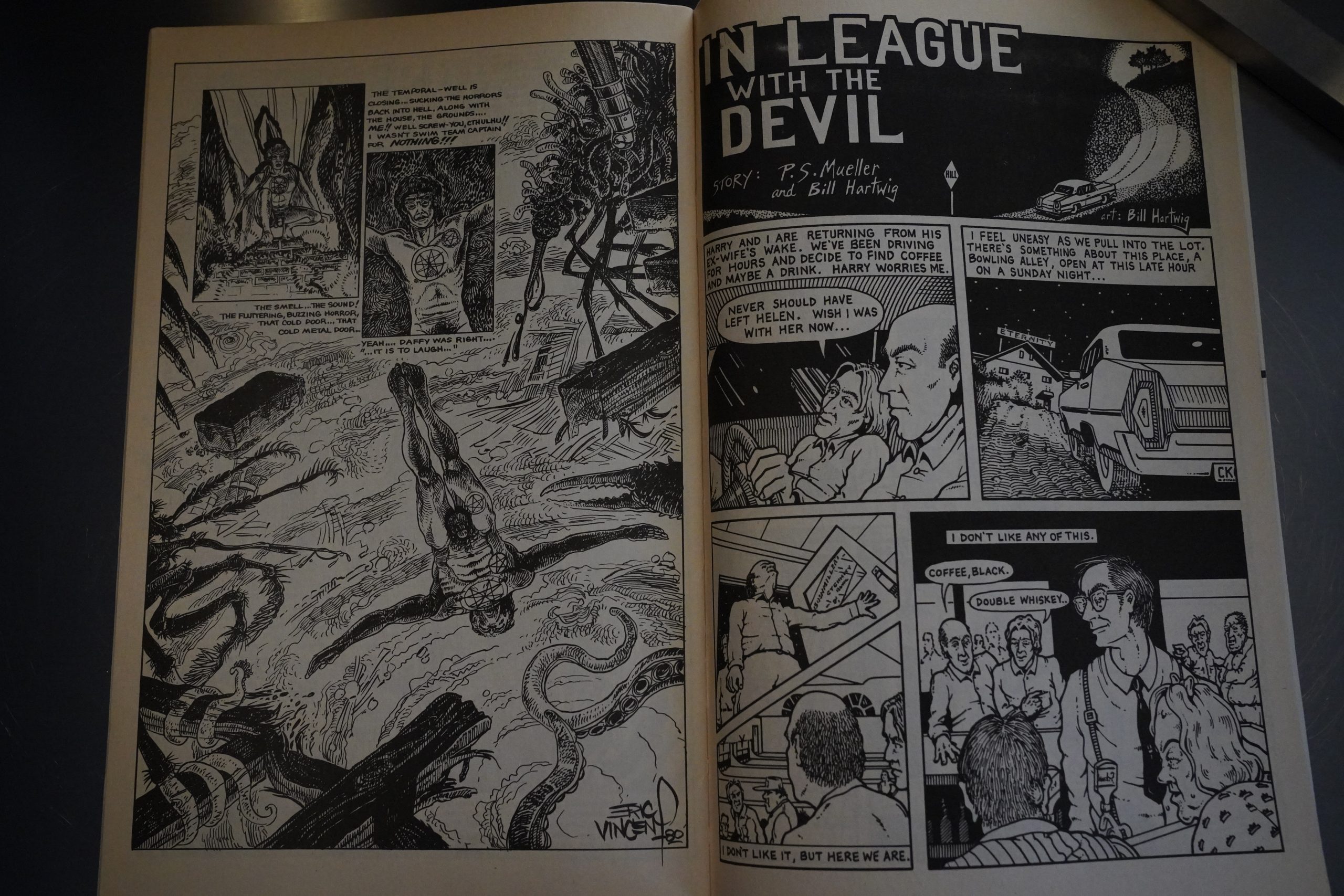

Most of the contents of the 11th issue is pretty dire, though, with this Eric Vincent piece from 1980, for instance. But the Muller/Hartwig thing is pretty solid, and so are their subsequent pieces over the rest of the issues.

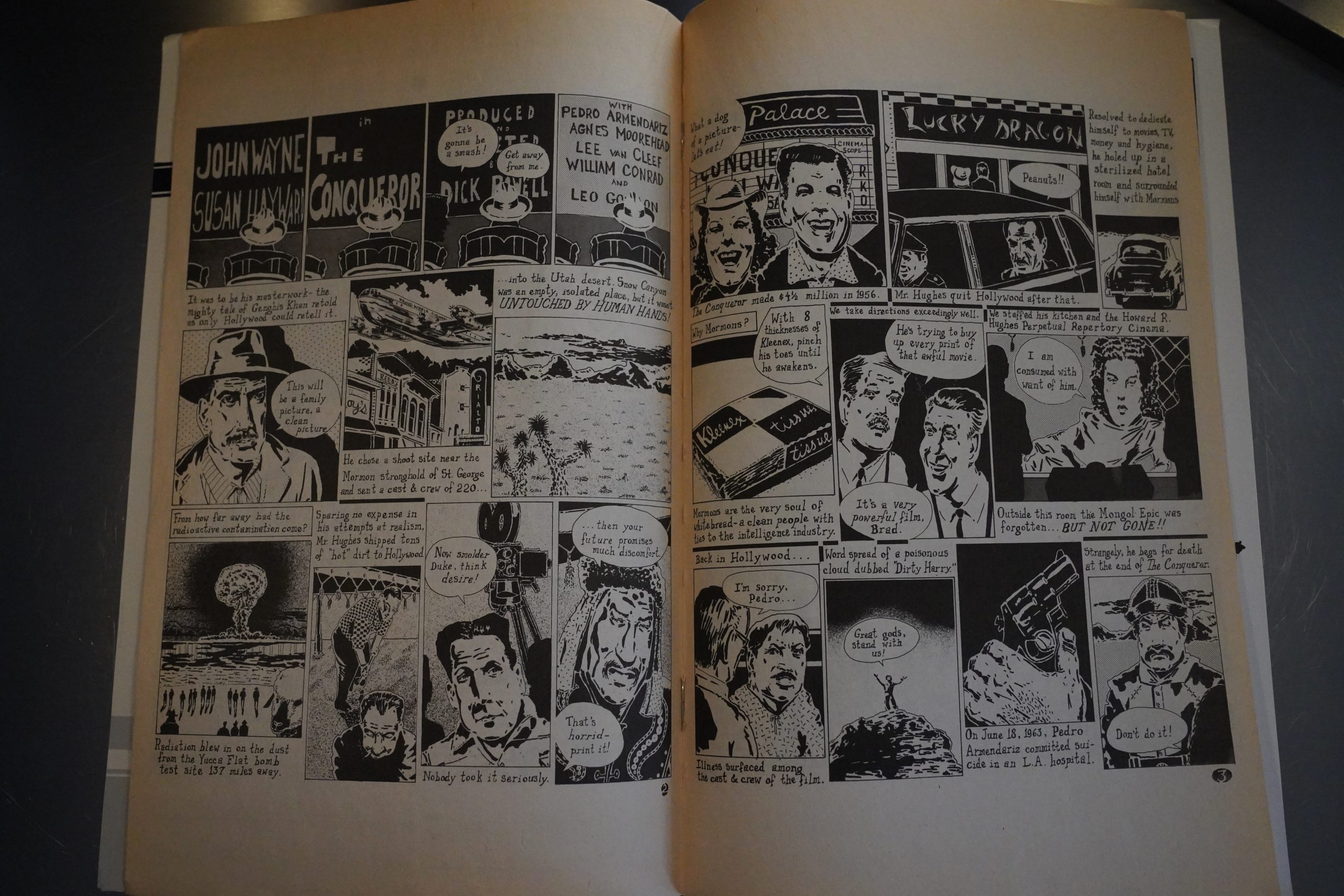

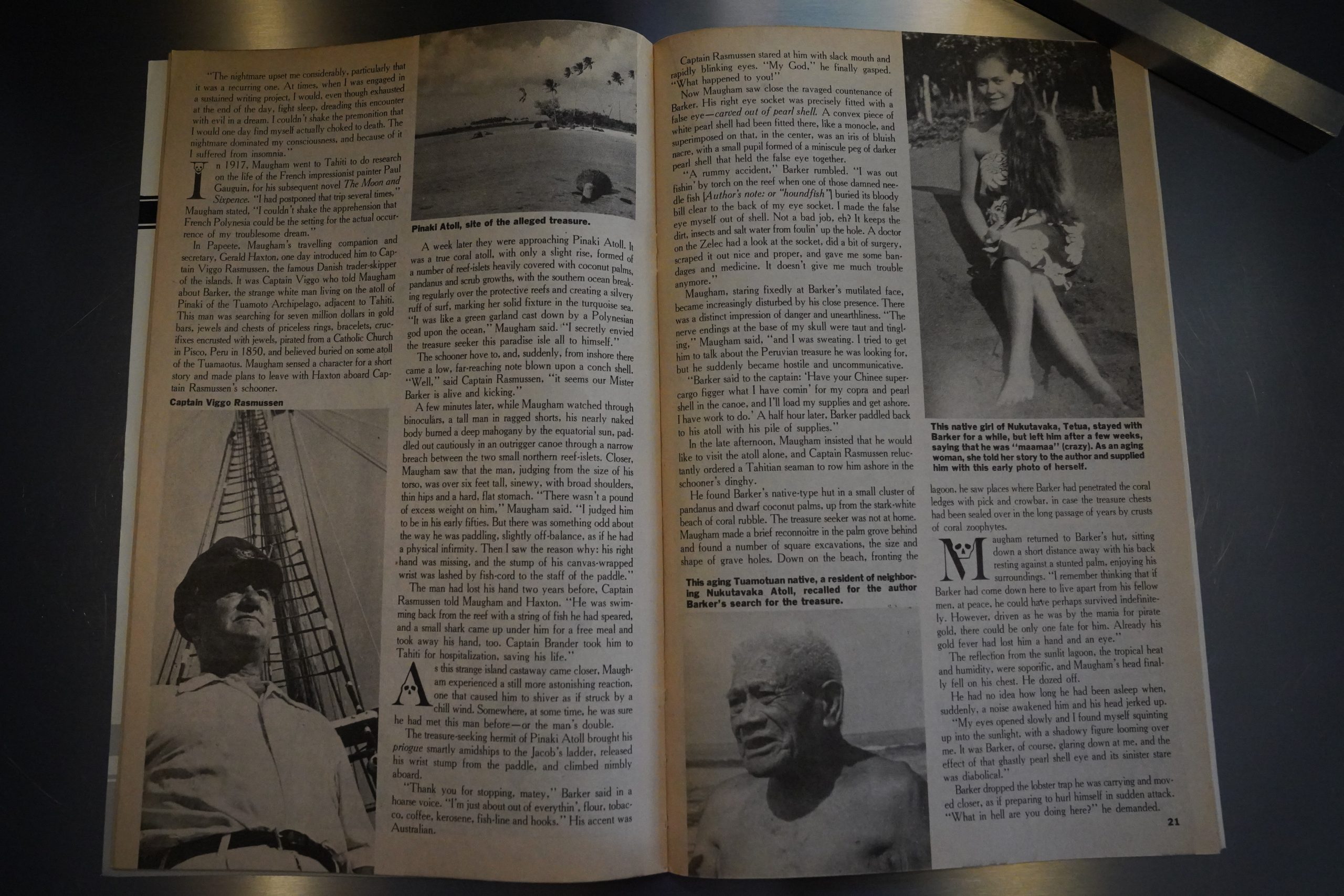

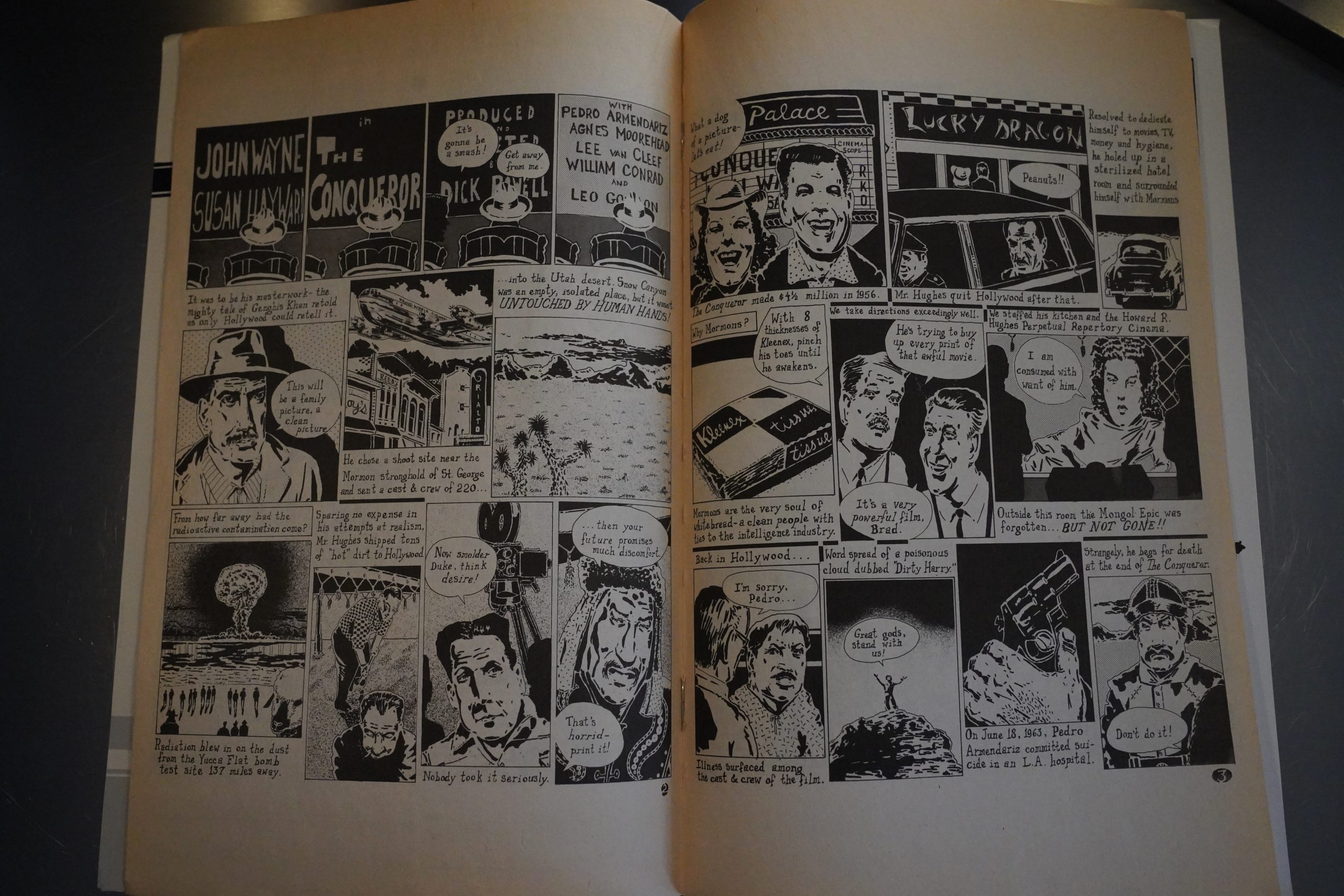

This Matthew Finch story about Howard Hughes, and the movie he made (where most of the crew got cancer, including John Wayne, to quote the song) was obviously meant for a different publication (note magazine form factor), but it’s graphically kinda intriguing.

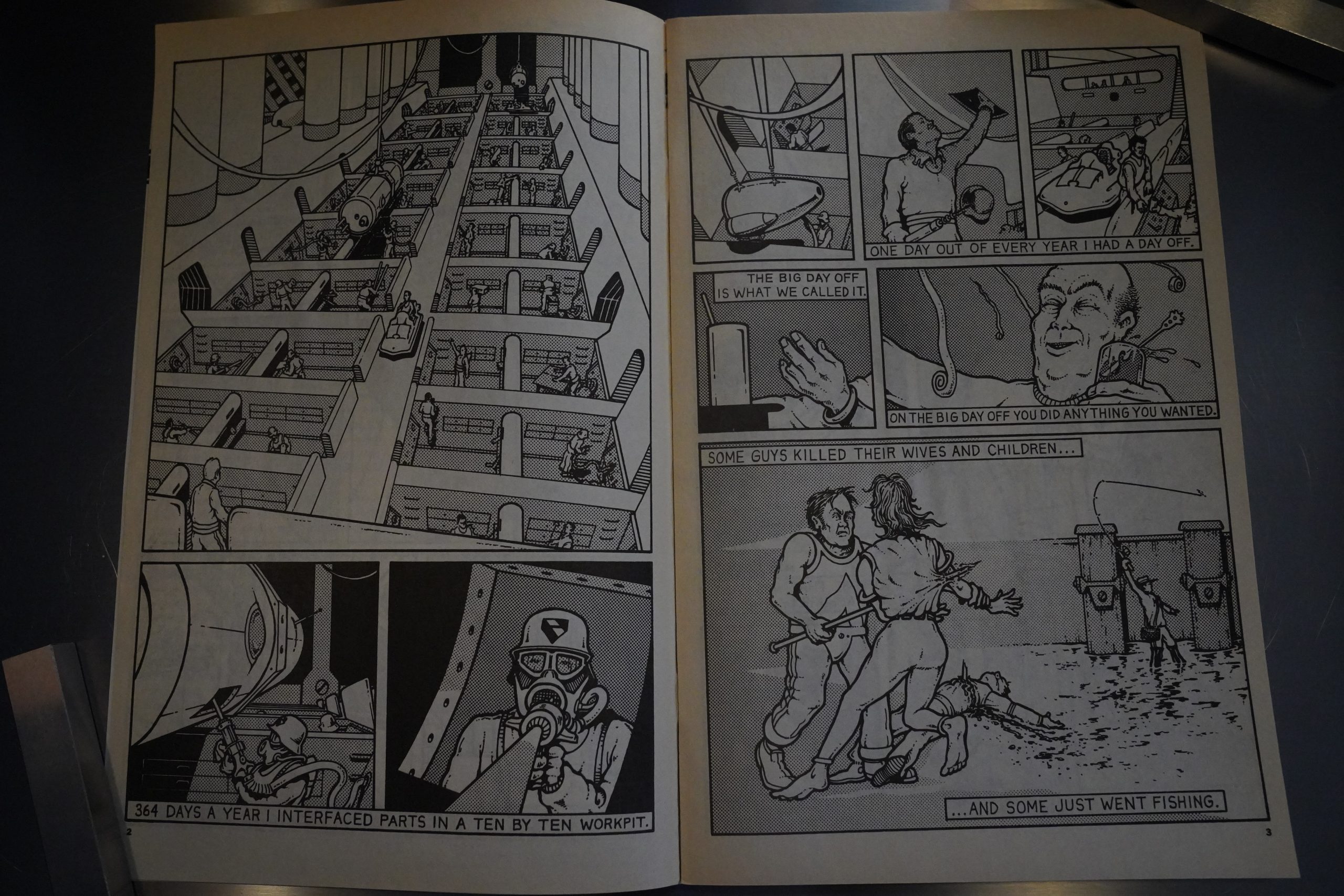

Note that no women killed their husbands, because women aren’t protagonists here. (Mueller/Hartwig.)

Which brings me to something I meant to mention earlier: There are no women contributing to this series — at all. That’s pretty peculiar in itself, but it’s more than odd for a Kitchen series. Kitchen’s earlier anthologies always had more than a couple of talented women appearing, but none here. I guess it’s the 80s.

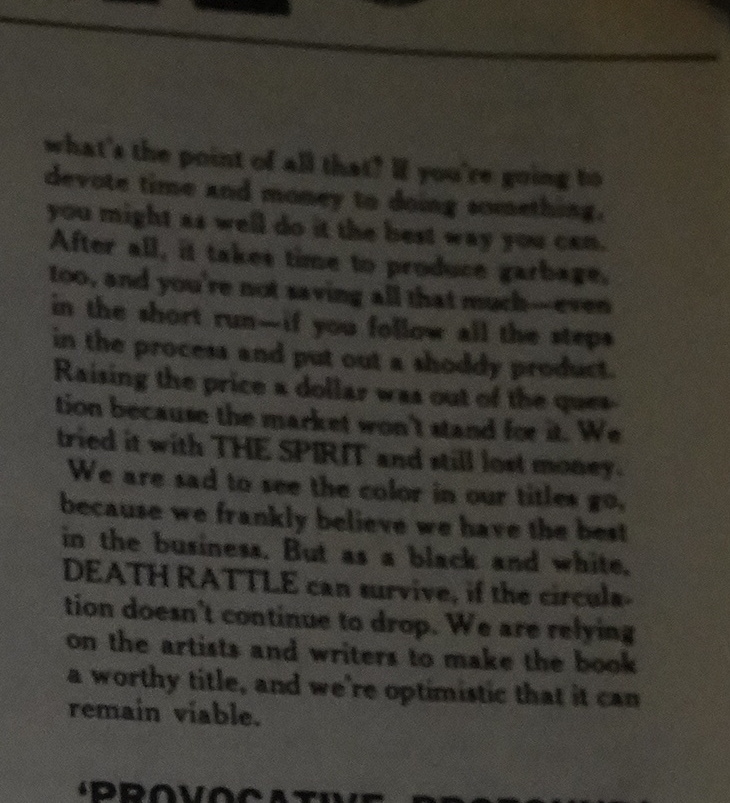

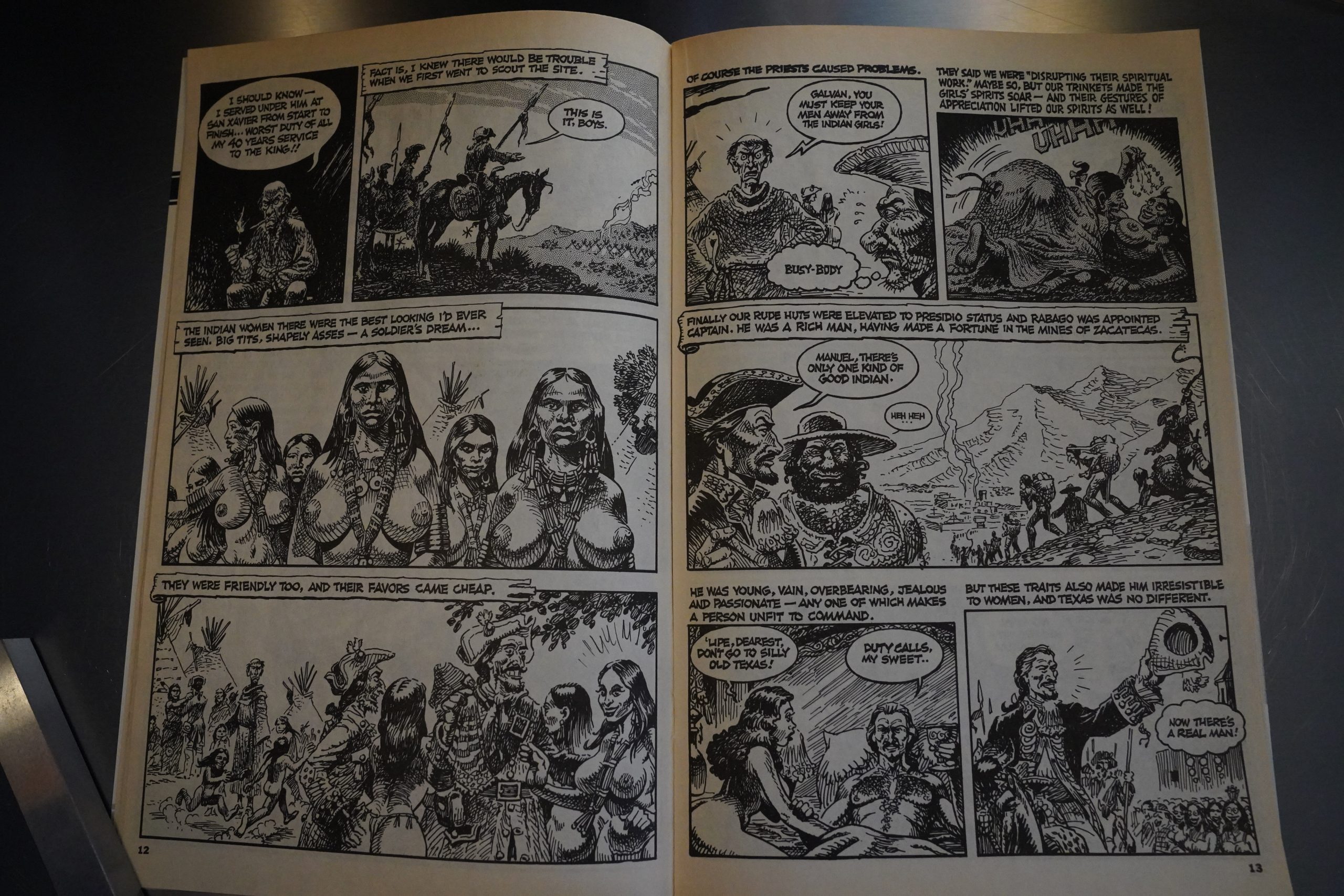

I wish I could say that the Jaxon epic turned out to be… epic… but he gets lost in the weeds. The story is ostensibly about an alien that is worshipped by some Native Americans, but Jaxon spends several issues digressing into stories about various Spanish commanders and stuff. In the end, the story just kind of fizzles.

It doesn’t help that many of the chapters feel like recaps of longer stories, either.

But the artwork’s solid.

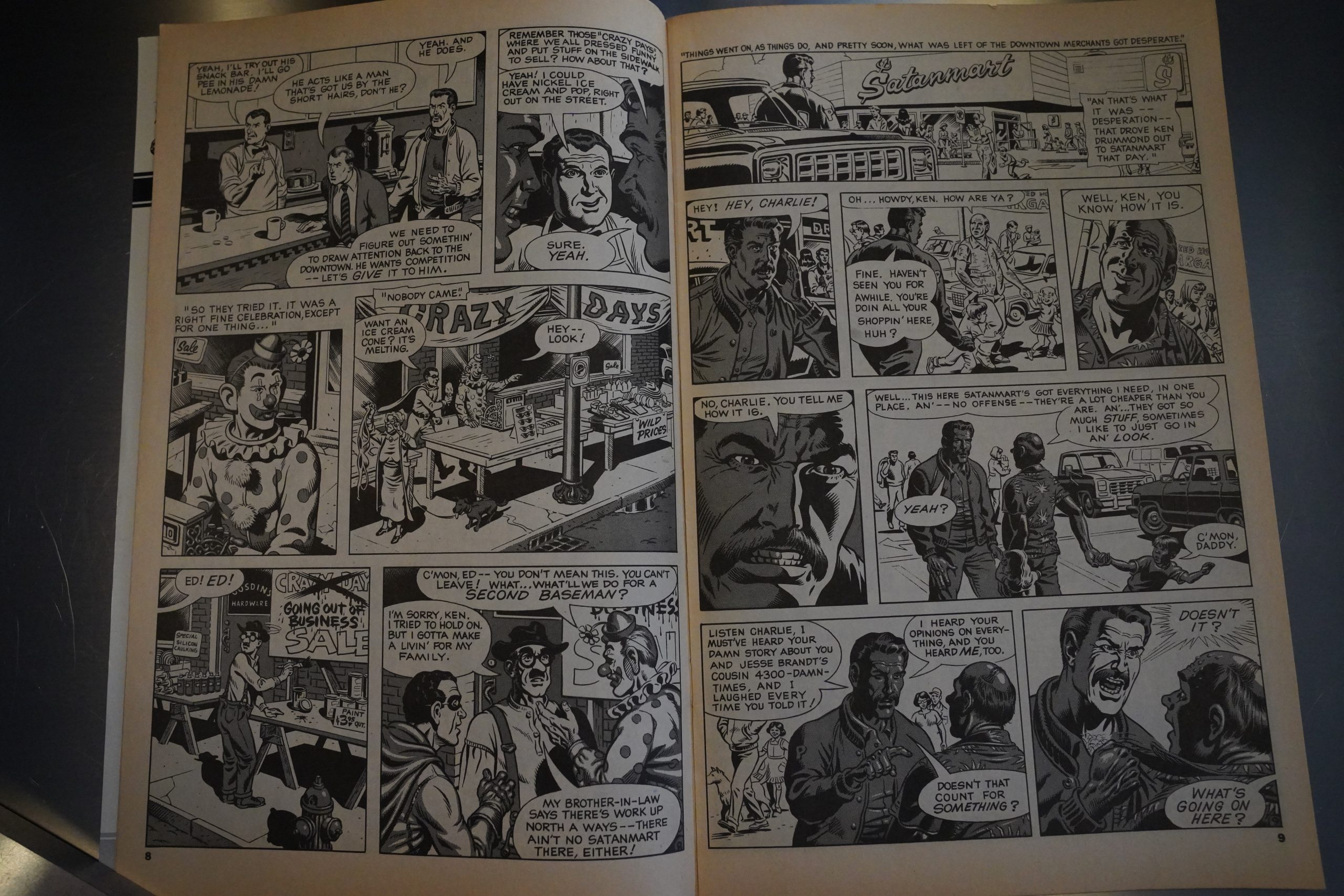

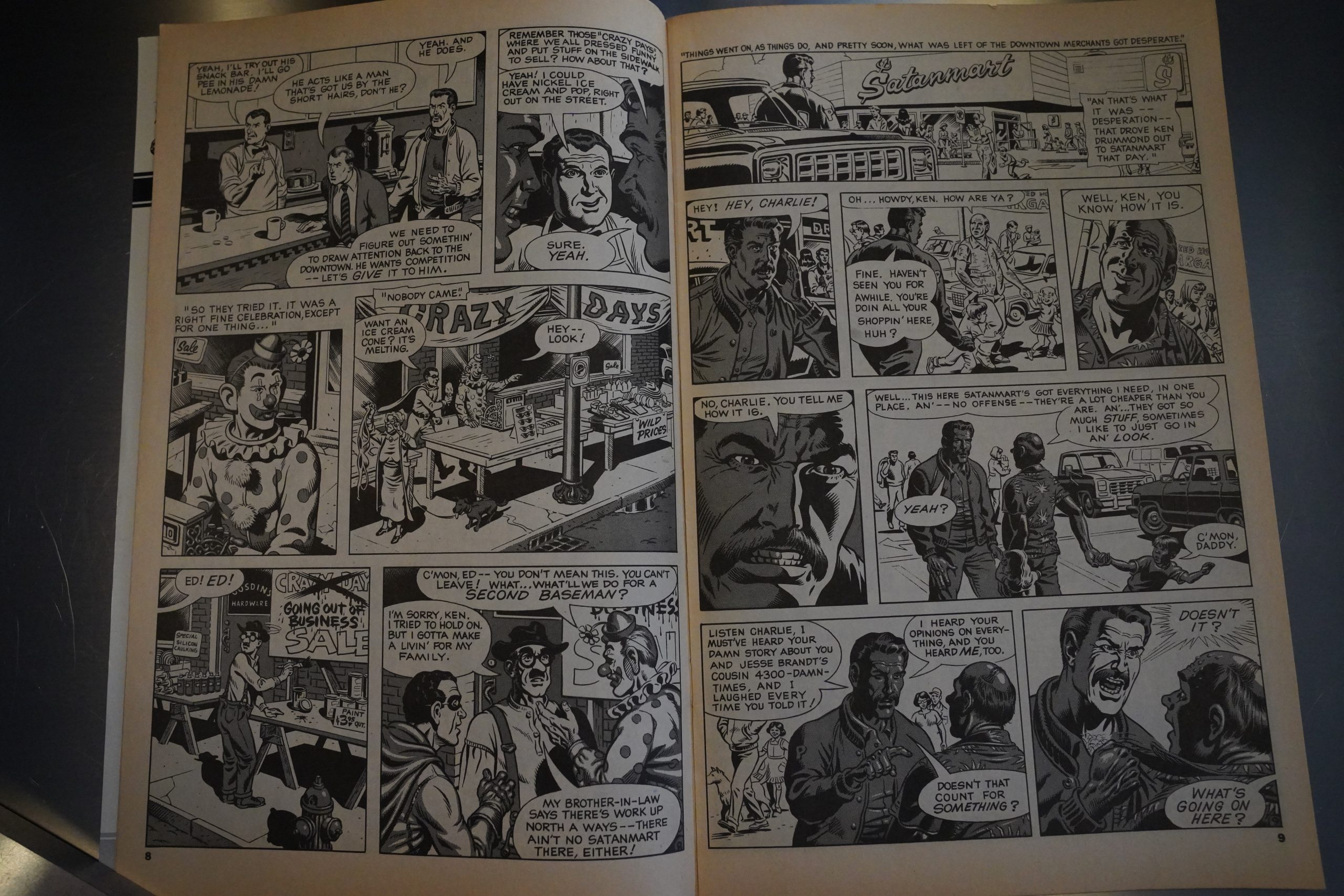

John Wooley and Jim Millaway writes a story about Walmart coming to town, and you couldn’t choose a subject that Rand Holmes would be less interested in drawing. I don’t think there’s any female characters in this at all? Or half naked men? Instead it’s just pages and pages of people standing around talking, and then seemingly ninety pages of a baseball match.

It’s pure tedium.

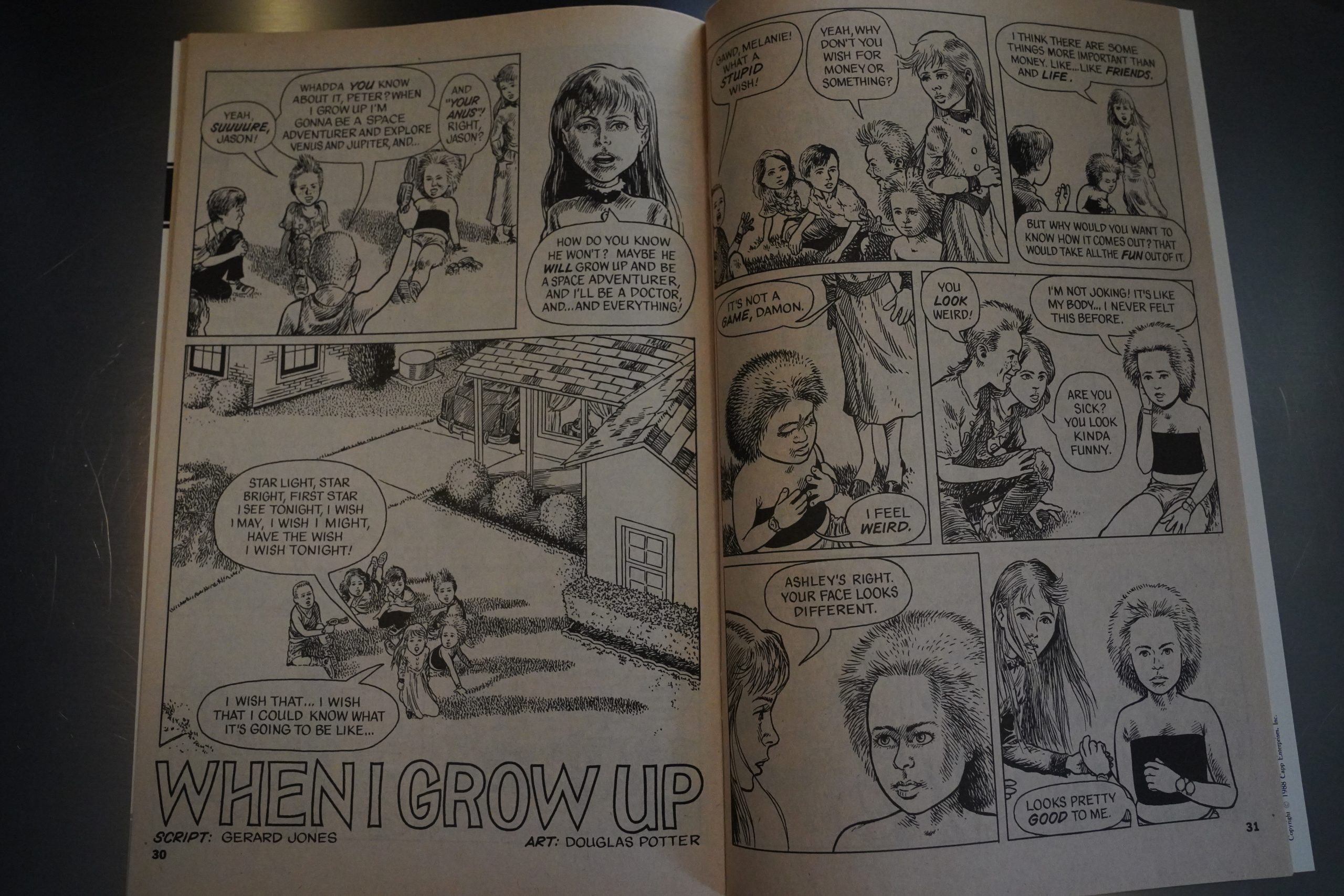

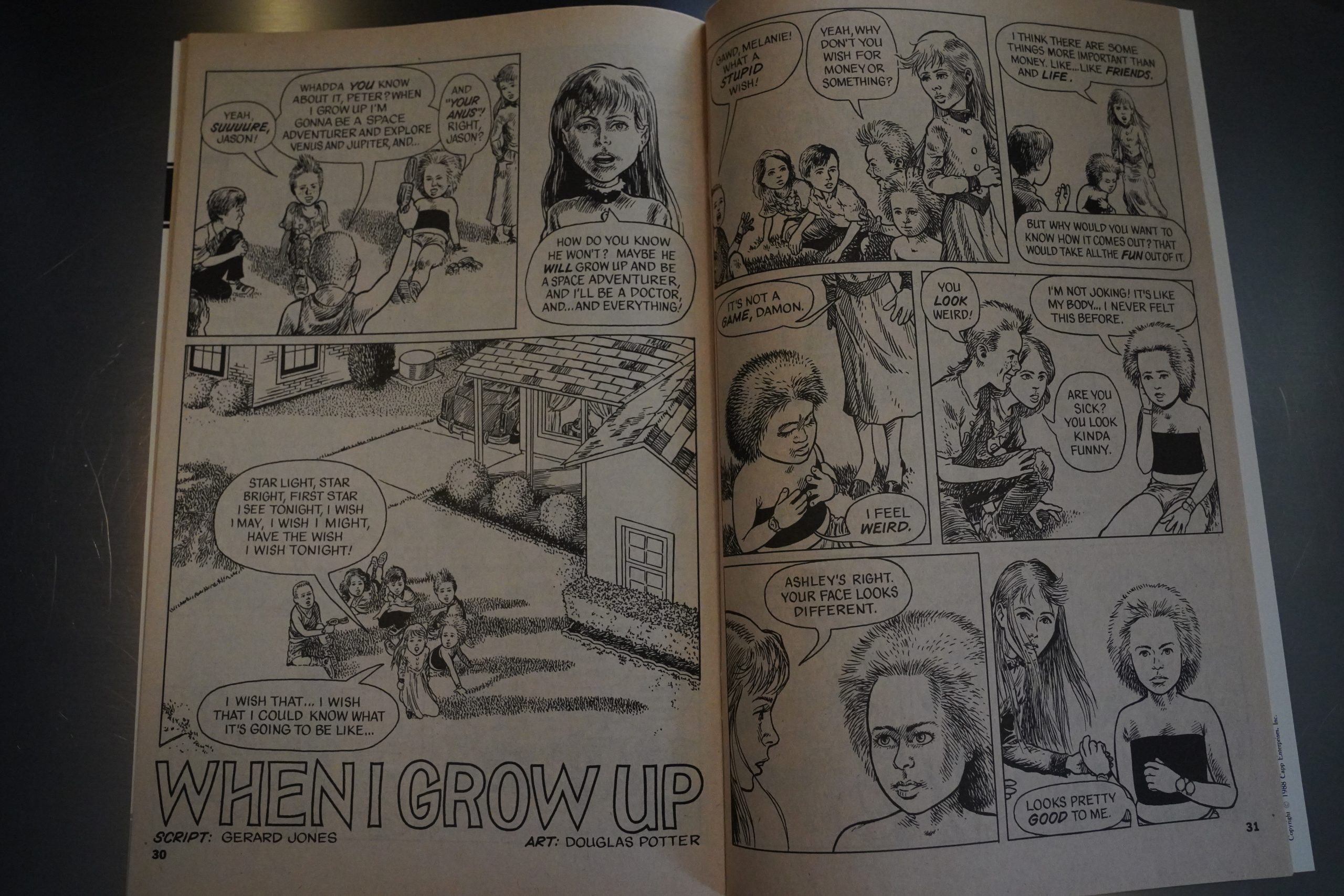

But perhaps not as bad as this creepy thing by Gerard Jones and Douglas Potter. And not creepy in the way it’s meant to be creepy either.

Chris McCubbin writes in Amazing Heroes #151, page 70:

No All-Hallows summary of scary

comics would be complete without

Death Rattle, the uncrowned king of

the moment. Sadly, hmvever, the most

current issue is actually a remarkably

mediocre example of the comic.

While an issue of Death Rattle can

and often does hold five storys or

more, #17 has only two. The culprit

this issue is the cover story, “Slide,

Sinner, Slide,” written by John Wooley

and Jim Millaway, and illustrated by

DR regular Rand Holmes.

The story is an obvious homage to

the classic TWilight Zone TV show,

which always built up a satisfying level

of terror, then resolved at the last

moment into a happy ending which re-

enforced the wholesome values of the

time and kept the network off Rod

Serling’s back.

This is a bit of a departure for Death

Rattle, where the stories almost always

end grimly, and that’s fine. However,

Wooley and Millaway commit the

unpardonable sin of smirking at their

source material. On the last page,

when the hay-chewin’, pickup-drivm ,

overall-wearin’ narrator drawls “Nmv

I know that some of you—specially

those of you with liberal arts

degrees—might try an’ sift through

this story for a moral or somethin’,

some symbolism or maybe a

metaphor. Heck, some of you might

even think this is one of them

allegories.” I just wanted to slap

somebody.

The story isn’t completely irre-

deemable. There is a nice satiric edge

to it—the central premise is that the

huge Ke and Wal- type convenience

marts are a (literally) diabolic plot to

undermine small-town life. And Rand

Holmes’s art is, as always, gorgeous,

and a remarkable evocation of the EC

style.

Much better is the penultimate

chapter of Jaxon’s long-running

historical fantasy “Bulto.”

Jaxon is one of the most original

comics artists on the scene today, and

“Bulto” is, in many ways, his most

unusual uork. Like many other Death

Rattle stories ‘ ‘Bulto” takes the

inhuman, intergalactic, pulp horrors

of Lovecraft and sets them up against

simple human cruelty, bigotry, and

callousness. Human evil wins, every

time. As I said, “Bulto” will run only

one more issue in Death Rattle. If

Kitchen Sink doesn’t give us a graphic

novel it will be a crime.

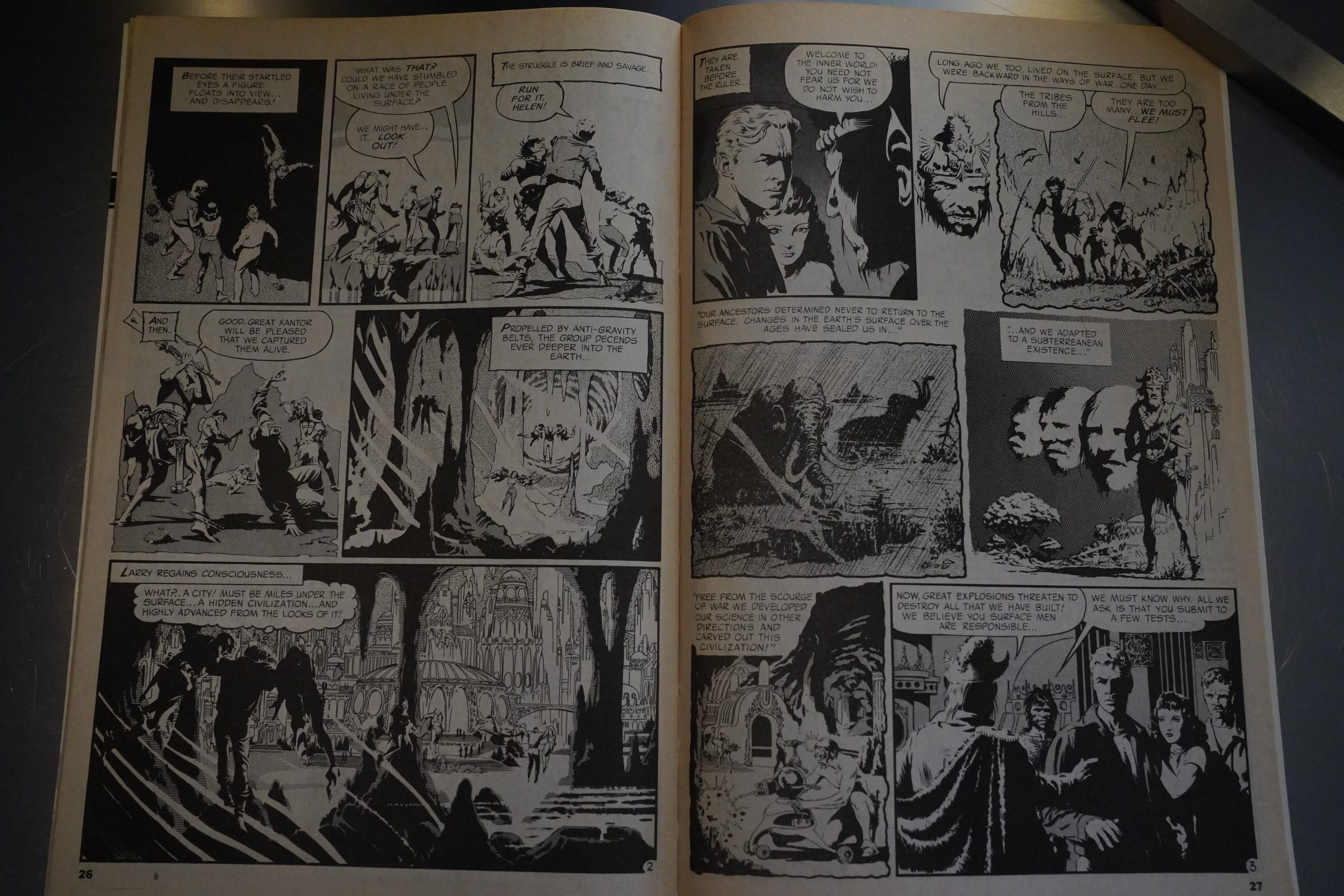

The Comics Journal #110, page 72:

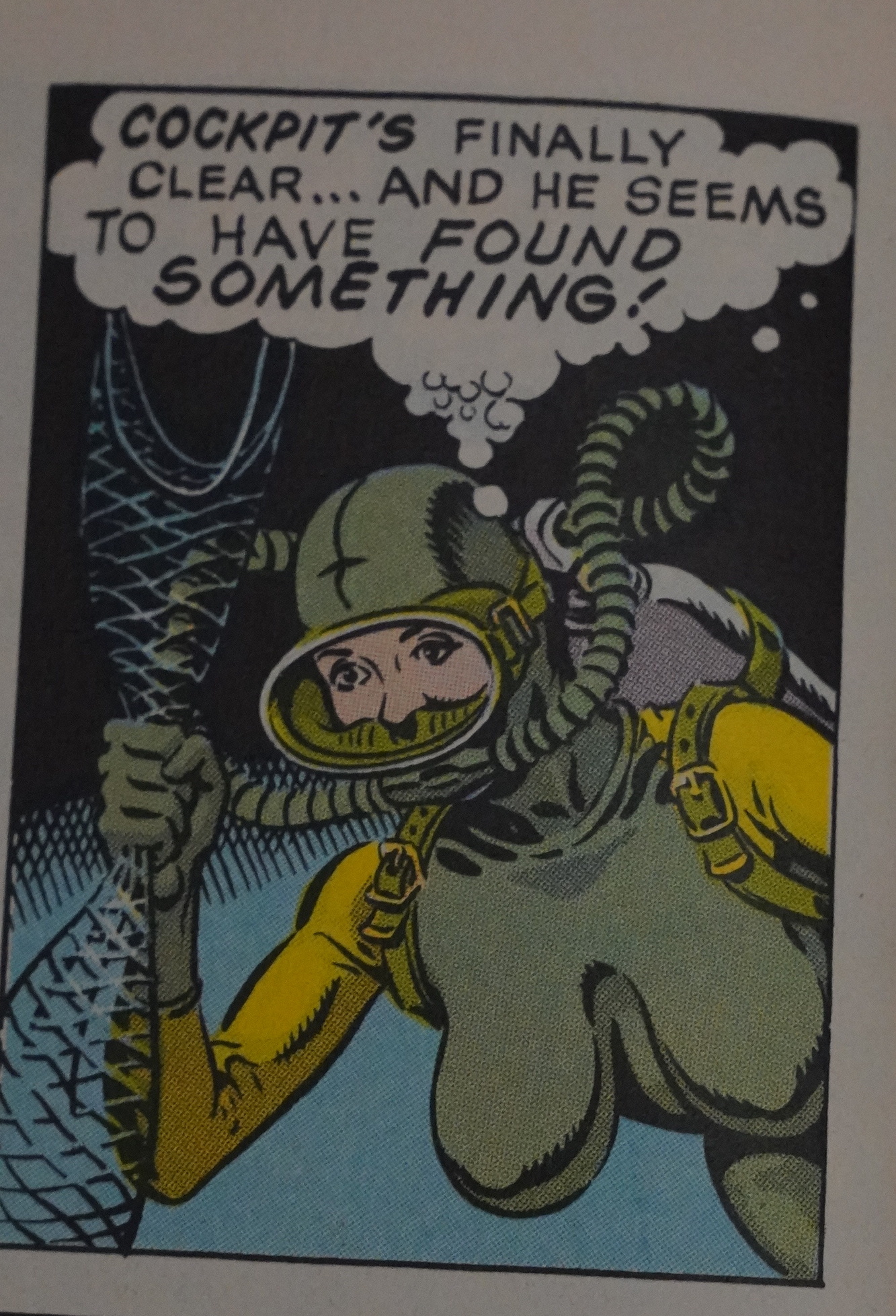

When you encounter something like

Rand Holmes’s IO•page “Killer Planet” in

the first issue or Steve Stiles 7•page “Mind

Siege!” in the third, it’s clear these artists

are paying hommage to certain traditions of

science fiction-horror Without tinkering

with the traditions. In the Holmes story, for

example, there are lots Of BEMS and a large

share of Wally Wood hardware and space

helmets; there is even the hallucinatory

vision of a prodigally endowed female, trig•

gered in the central character’s imagination

by a hostile ‘ ‘dreamweaver.” (At least the

character has the good sense to recognize

what he’s seeing and back away from the

apparition: it’s as if he’d read all the science

fiction stories in which characters don’t.)

This story, as well as Stiles’s “Mind Siege!,”

are satisfying examples of a writer-artist

working within an easily recognizable tradi-

tion While avoiding the hoariest cliches and

more ossified conventions of the by-now

sanctified standard-bearers in the field. The

reader thus garnet•s the satisfication of a

competently managed use Of the genre and

draws reassurance from the visual expertise.

Death Rattle has its ambitions, though.

Charles Burns’ Is-page “Ill Bred” (sardon-

ically subtitled Horror Romance’) is a

grotesque and haunting slice of horror that

is positively Strindbergian in its disturbing

overtones. Burns’s creepy image-making has

found its way into a number of publications.

(His most impressive showcase was in Raw).

While there’k an eccentricity about his style

that is rather distancing, he’s probably as

adept at establishing an atmosphere of

floating anxiety and soliciting a response of

genuine dread as any other current artist

that comes to mind.

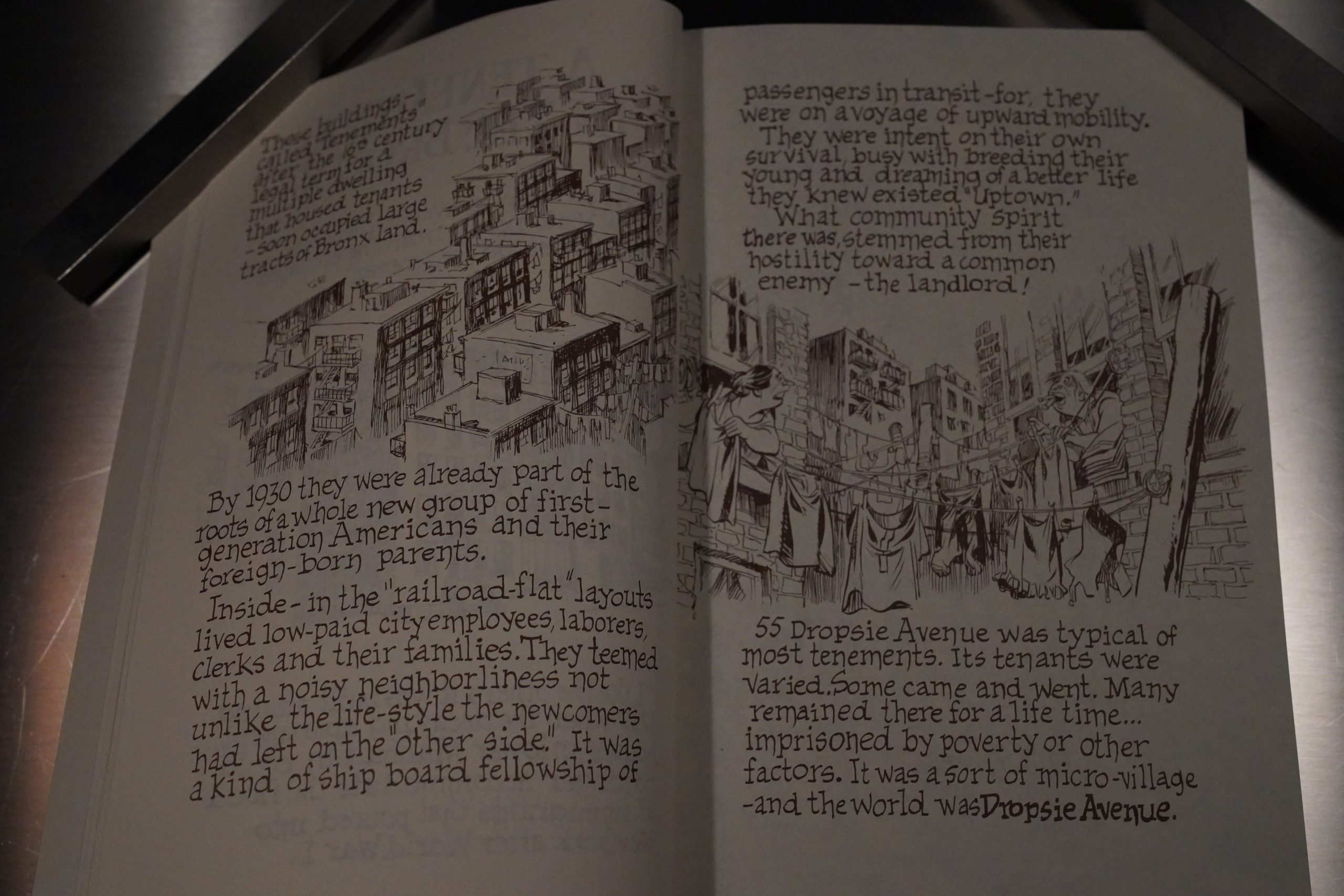

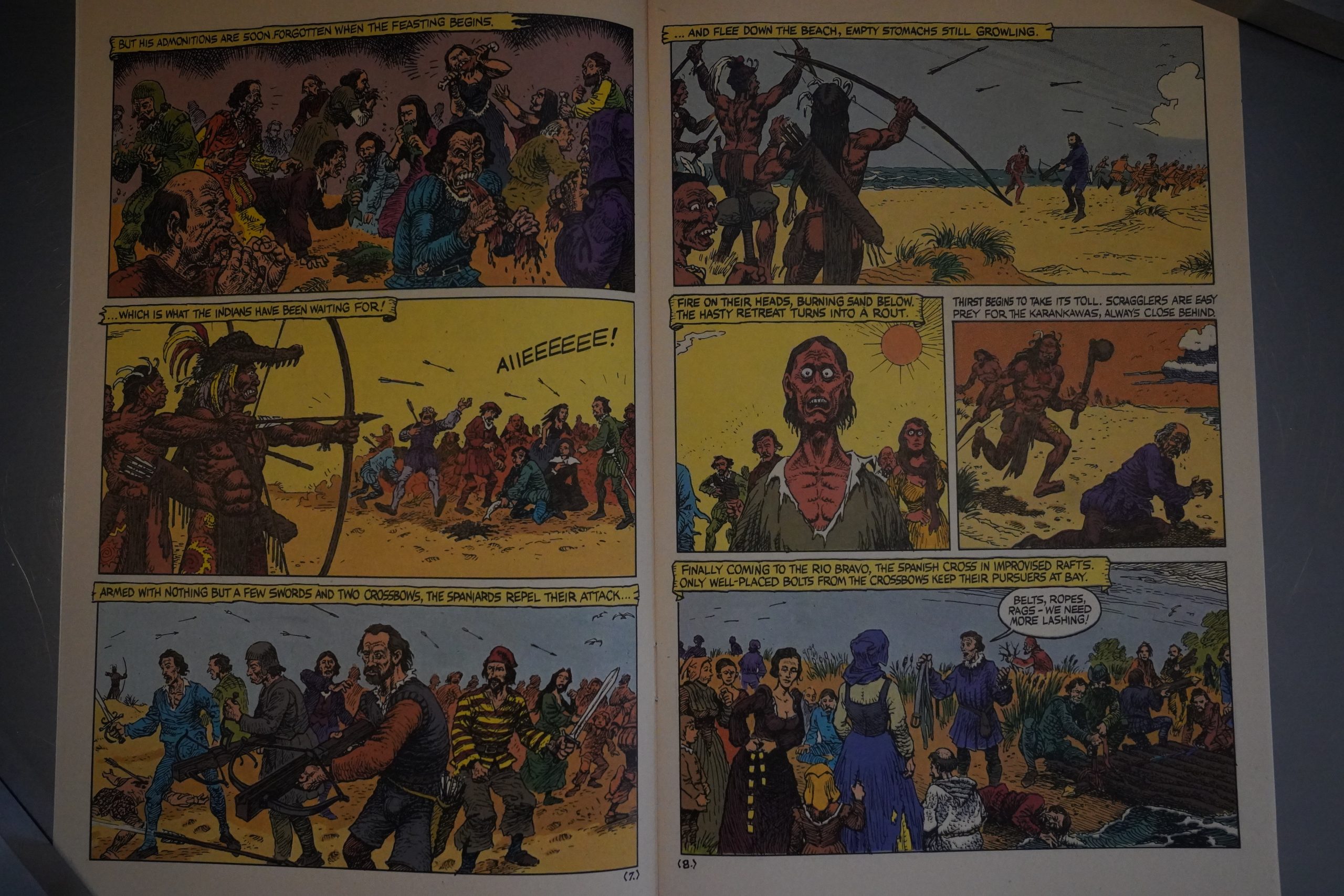

Another major piece, Jaxon’s

Bosom” in the second issue, is an unex-

pected use Of historical sources—a group Of

shipwrecked Spaniards are systematically

terrorized and murdered by hostile Texas

Indians during the 16th century—as the

basis for horror. Jaxon’s visual approach to

comix in books is extremely sophisticated,

but there’s a kind Of emotional distancing

effect in much of his work. He doesn’t create

characters through whom the reader might

participate sympathetically in the telling of

the story. Jaxon doesn’t seem inclined to

individualize or develop his characters as

human beings; in a book like Los Tejanos,

you begin to suspect he pulls back from

exploring character in any depth because he

feels it would falsify the historical authen•

ticity of the stories he’s telling. (In Los

Tejanos, the characters Often seem stiff and

archly posed, like images from Old photo-

graphs.)

Russell Freund writes in The Comics Journal #107, page 48:

Death Rattle is the name of Kitchen Sink

Press’ new book of horror and full-blooded

adventure, and while the

first two issues range widely

in tone—the unifying theme

for this book’s tales might be

“no two alike-each con-

tains some first-rate work.

Could you ever mistake

Charles Burns for anyone

else? What a bleak, weirdly

compelling stylist he is. He

contributes “Ill Bred” to

issue a horror story that

expands on some images

that have appeared in his

non-narrative pieces, partic-

ularly ‘… And Pressed my

Hand Against his Face..

in RAW 3. In that pageful of

panels from a cool night-

mare, we saw a man and a

woman, bland and serene,

face a bed in which lay a

monstrous insect. That same

insect lives within the pro-

tagonist’s bed in “Ill Bred.”

I don’t want to give the

premise away, because much

of the story’s fascination is

in its horrid, almost vomitous premise, but

it’s a story of sexual dread that intertwines

human sex with the copulating of insects

(bug lust figured in the RAW piece, too).

Burns is onto something crawly. He is an

artist in the grip of grim fascinations, and

he has the ability to transmit those fascina-

tions to the reader.

At first his drawing looks as bland and

affectless as the art in a hack romance book.

But there is great dread at the edges. Take

the panel where the caption reads, didn’t

go Out on dates very often, and when I did,

they invariably turned into a nightmare.”

At first the illustration seems to contradict

the caption, as we see the protagonist kiss

a pretty blonde. Where’s the nightmare in

that? But wait, look at their eyes. They’re

open. Eyes like slits, staring at each other

as they’ kiss with, what, apprehension?

Loathing? Zonked-out boredom? Whatever

it is, there’s something lurking in those

nothing little eyes that takes the kiss into

the realm of nightmare.

[…]

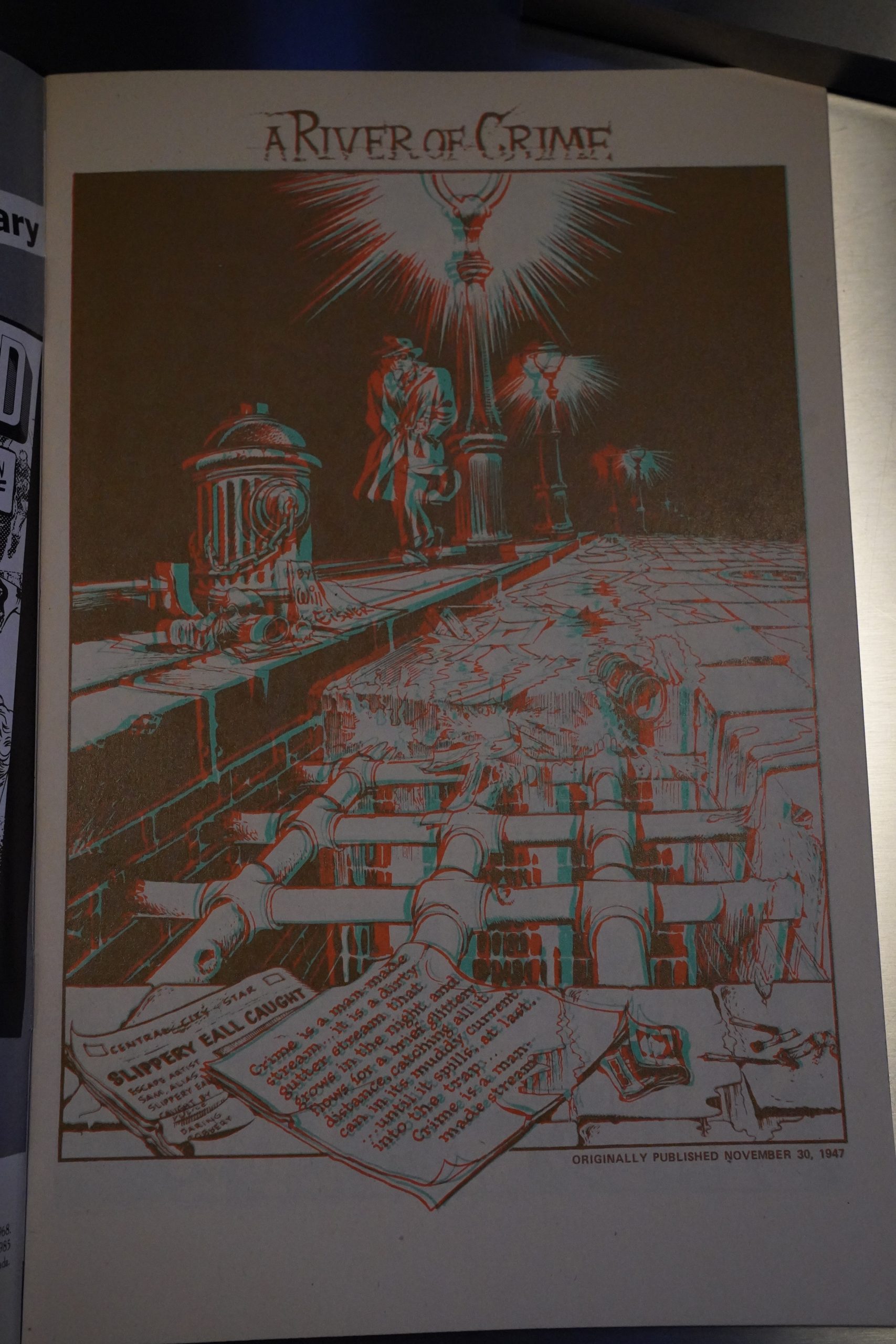

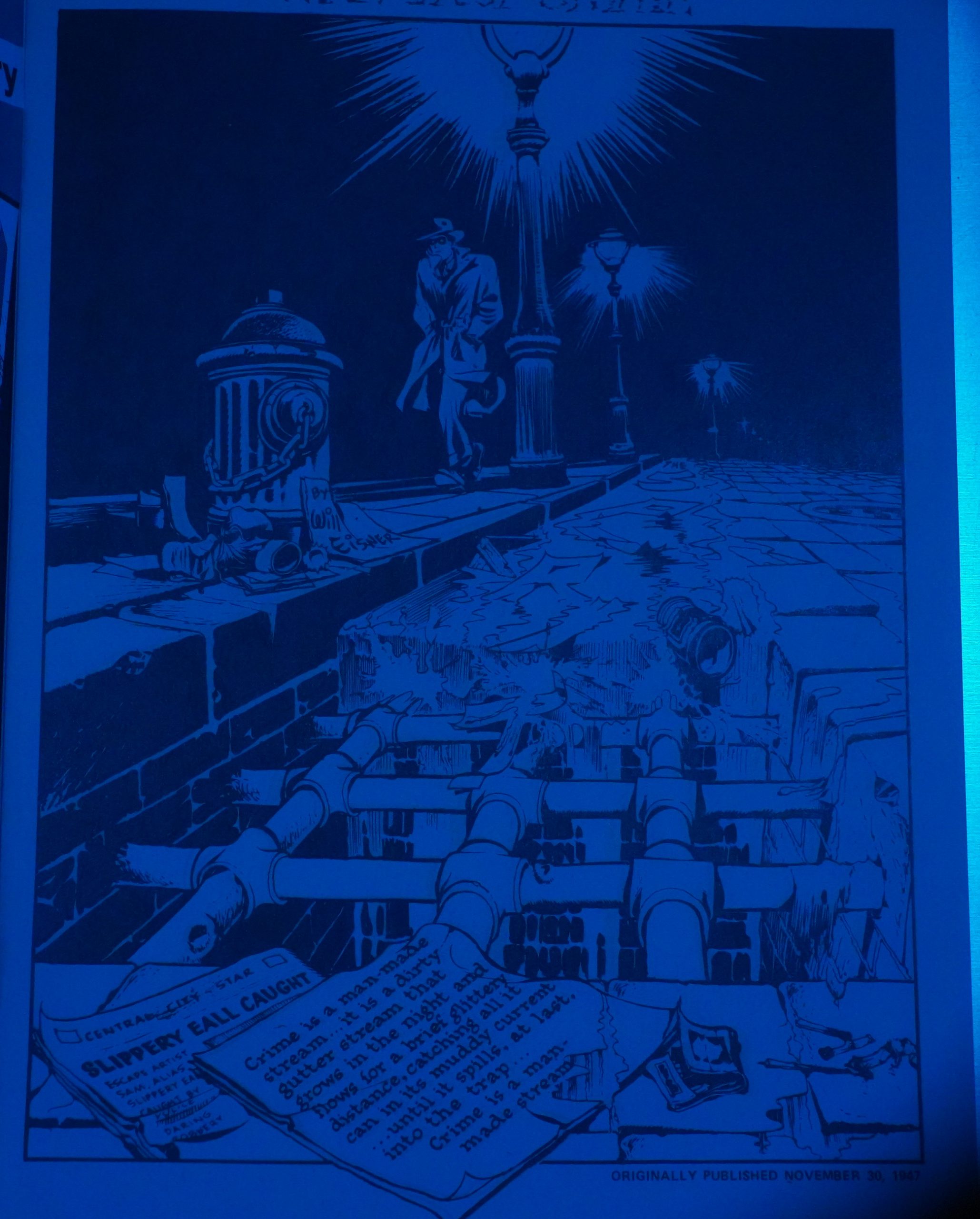

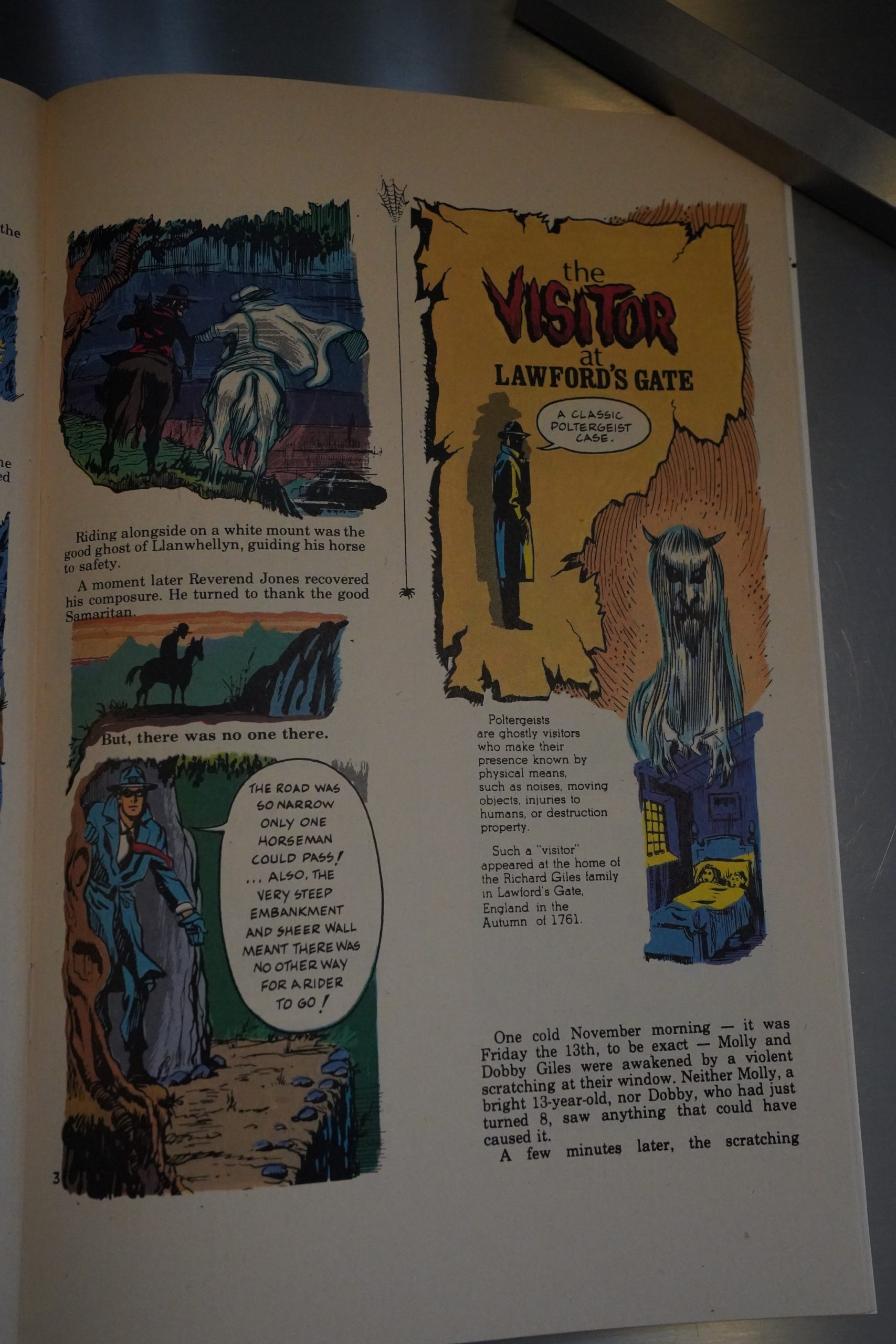

Something by Will Eisner, evidently done

a decade ago, is printed in Death Rattle

Called ‘A QUagmire of Occult Stories,” it’s

not really a comic story, but a short text

piece with lots of illustrations. It’s very

minor Eisner, there isn’t much suspense, or

even interest, in these three musty ghost

stories, and telling the stories in text

supplemented by pictures robs us of the

pleasure of seeing Mr. Eisner do what he

does so brilliantly, that is to tell stories with

pictures, supplemented by words. Still,

Eisner is Eisner, and he favors us with no

fewer than seven drawings of the Spirit, who

narrates.

Rand Holmes is in both issues. “Killer

Planet” in issue ‘l lands some spacemen on

a planet teeming with exotic menaces, and

Holmes gives us one B.E.M. after another.

Holmes doesn’t quite have the control

needed to duplicate

the chilled-out poise of

Wally Wood, whom

he so clearly adores,

but he’s close enough

for the purposes of

this somewhat silly

material, and gives it a

good ride.

Amazing Heroes #120, page 64:

Okay, one last addition to the Best

of ’86 list before I drop the subject

(Oh, the anal-retentive’s lot is not a

happy one). This is one i kept vacil-

lating on, because it’s been so incon-

sistent, but overall this is a comic

book that’s made a good and distinc-

tive contribution to the field.

The best thing about Death Rattle

is “Bulto the Cosmic Slug,” an in-

termittent serial of mystical horror

by Jack Jackson (Jaxon), one of the

most powerful and consistent talents

to emerge from the old underground

comix. Telling the story of an alien

monster slug that appears as a god

to the Apaches during the Spanish

conquest of Texas, it combines

Lovecraftian chills with the Indian

lore and carefully detailed Texas

history that Jackson has made his

special provinces. It’s a potent com-

bination of elements, beautifully

crafted and told the only guy who

could pull such a mixture off, and

I am waiting eagerly for its

continuation.

Unfortunately, the rest of Death

Rattle hasn’t been nearly as solid,

and the issues without “Bulto” often

have trouble standing on their own.

Even when it’s weaker, hmvever, this

remains a distinct and creative com-

ic book. The greatest fun it offers

is its echo of the old E.C. Horror

comics. But this isn’t a slick pastiche

of craftsmanly E.C. stories, like

Twisted Tales and others. This stuff

is rooted in the underground, often

produced by writers and artists

whose vvork was shaped in the com-

ix of the late ’60s and early ’70s.

E.C. had an enormous influence on

the undergrounders, both through its

subtly antisocial horror comics and

the brazen irreverence of Harvey

Kurtzman’s Mad; its prematrue

demise at the hands of whitelipped

and trembling do-gooders seems to

have left many of those rebel car-

toonists with an angry desire to

revive those “nasty things” that has

not abated even after more than 30

years.

This is the seventy-fourth post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.