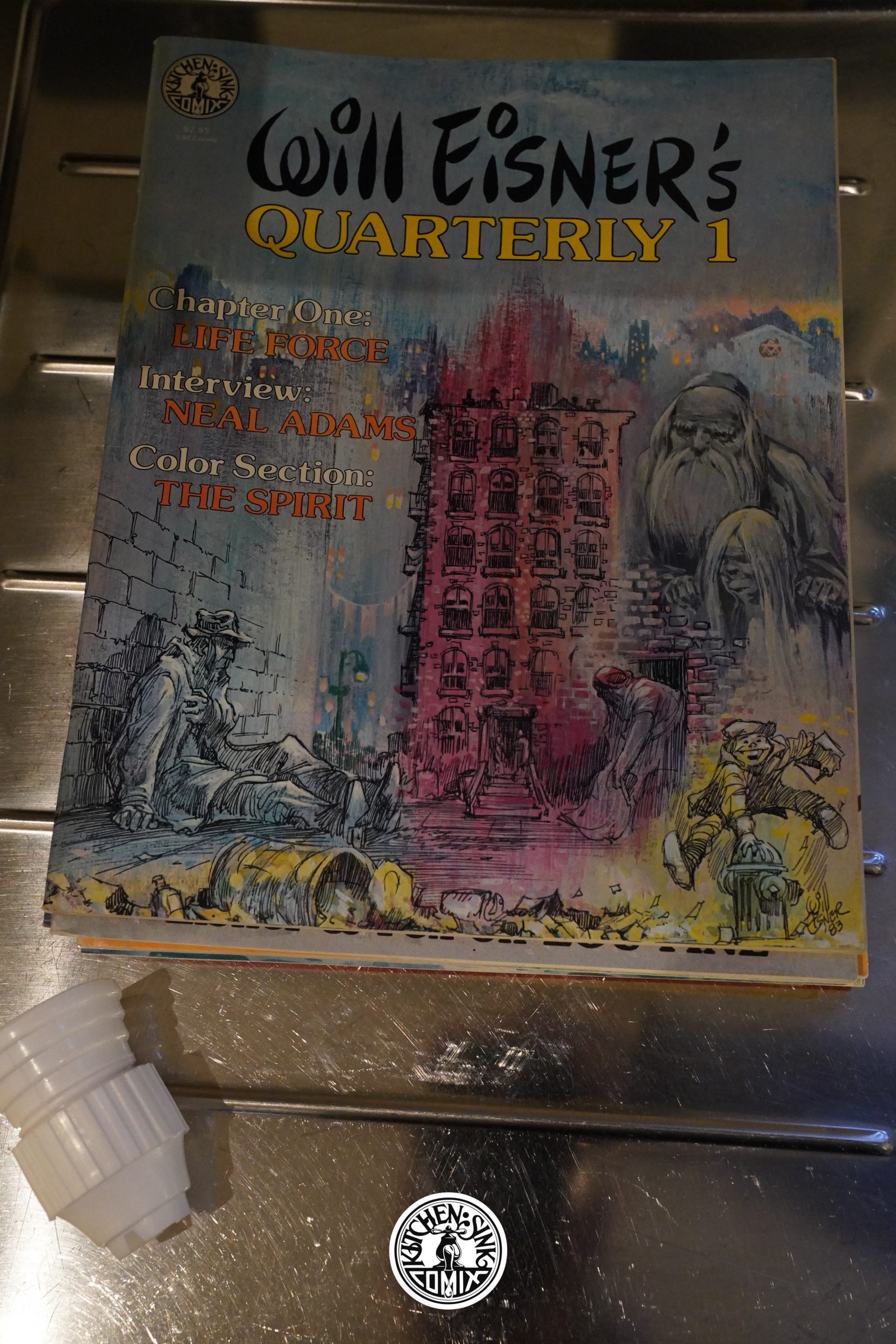

Will Eisner’s Quarterly (1983) #1-8 by Will Eisner

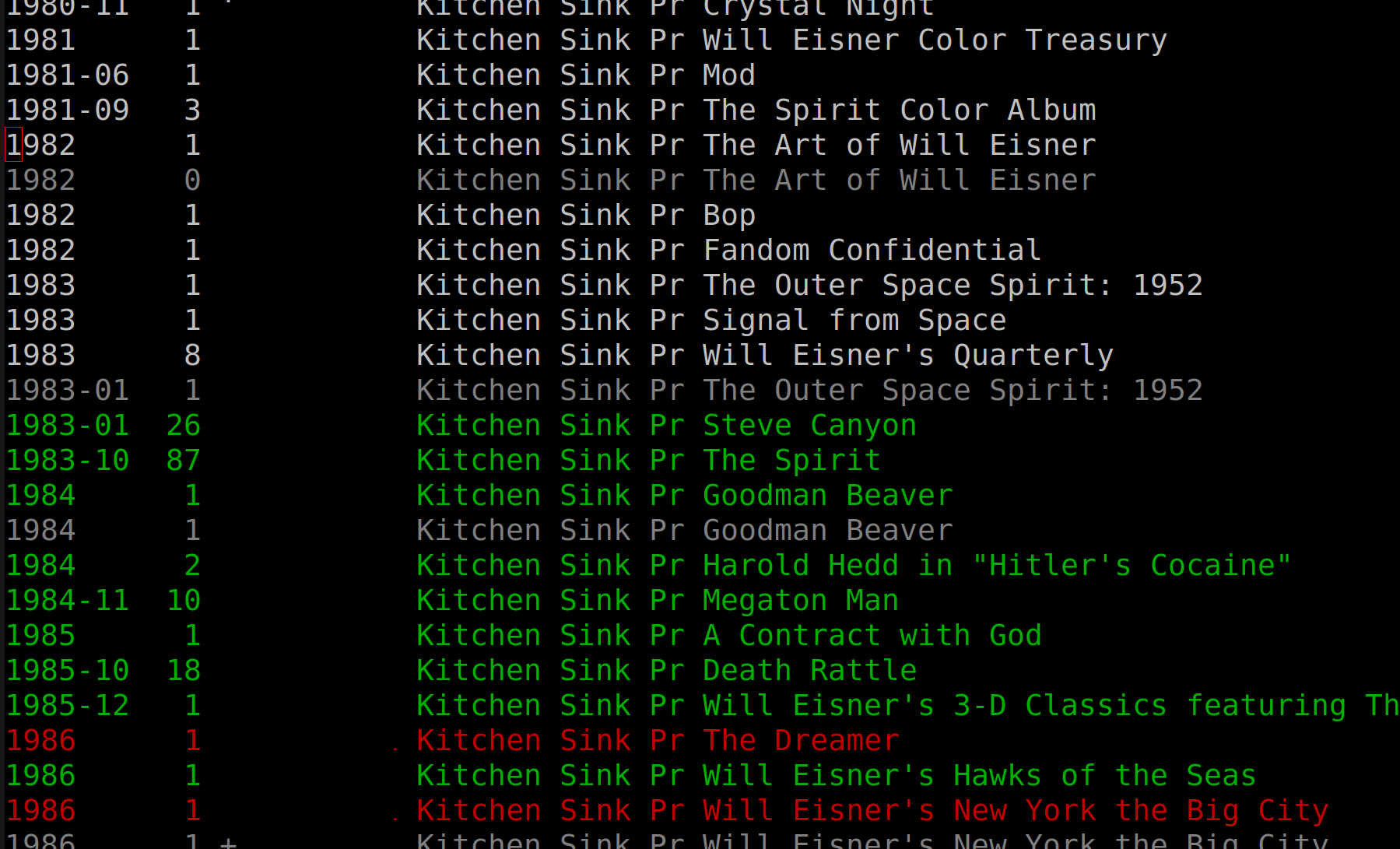

Kitchen Sink had published The Spirit for a few years, but in 1981 the Eisner side of the business really took off — and became the main part of the business. Of the 20 new titles Kitchen released between 1981 and 1986, 12 of them were Eisner titles. (Depending on how you count.) Now, some older titles continued to appear (like Gay Comix), but there’s only a handful of them. And Kitchen continued reprinting older Crumb undergrounds, but it’s nevertheless a striking shift.

Looking at the shortboxes of Kitchen stuff I have here, my guesstimate is that the Eisner stuff ended up being about… a quarter? of the total volume of things Kitchen published.

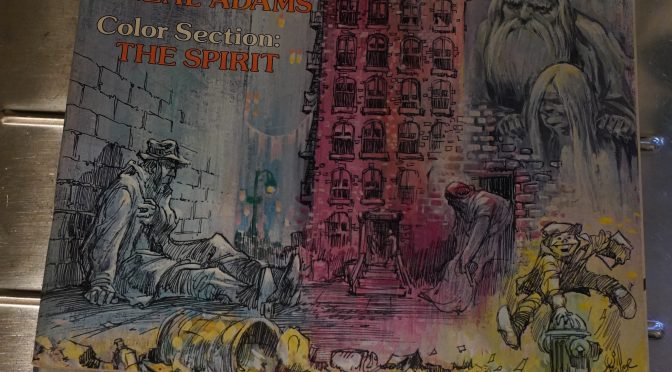

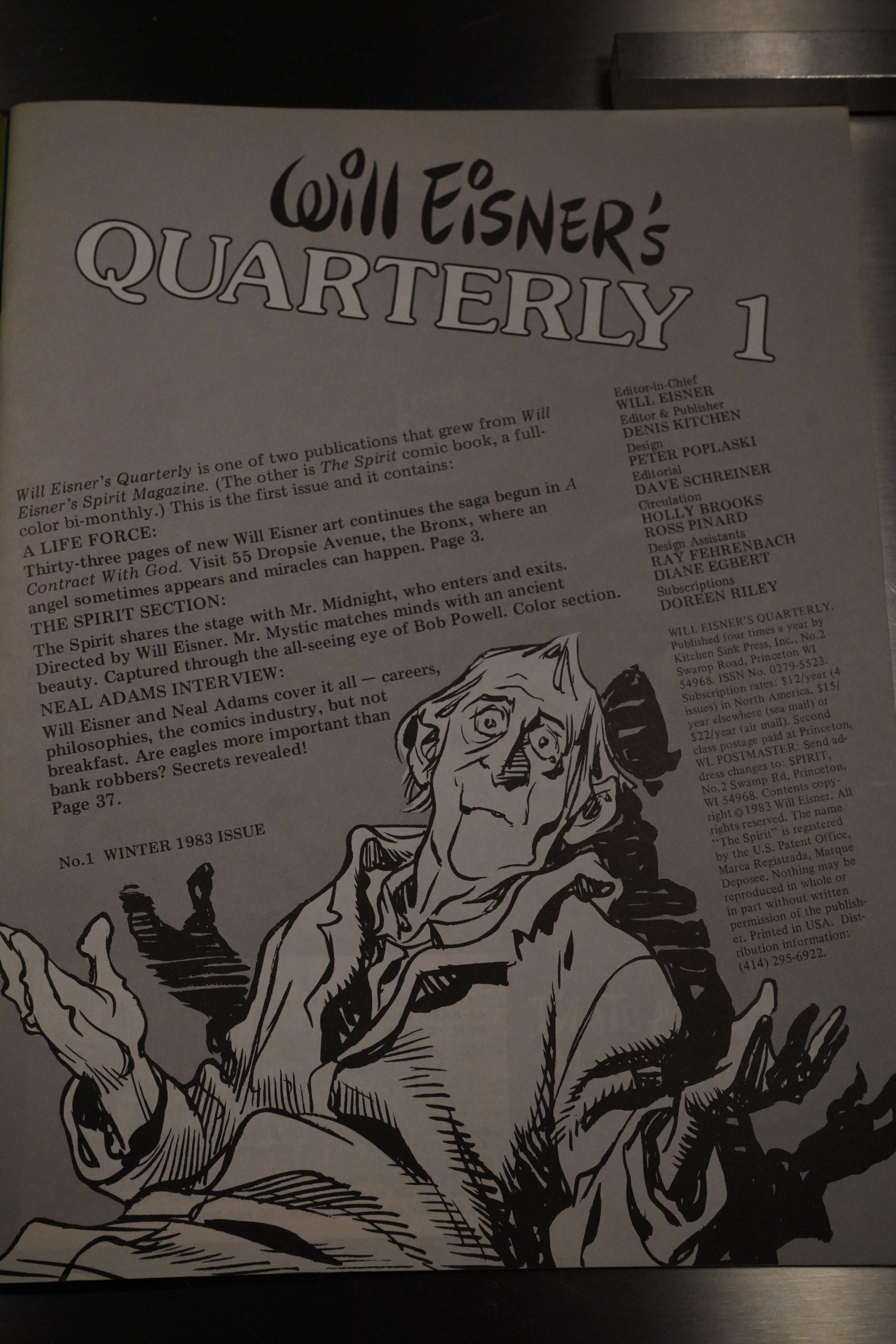

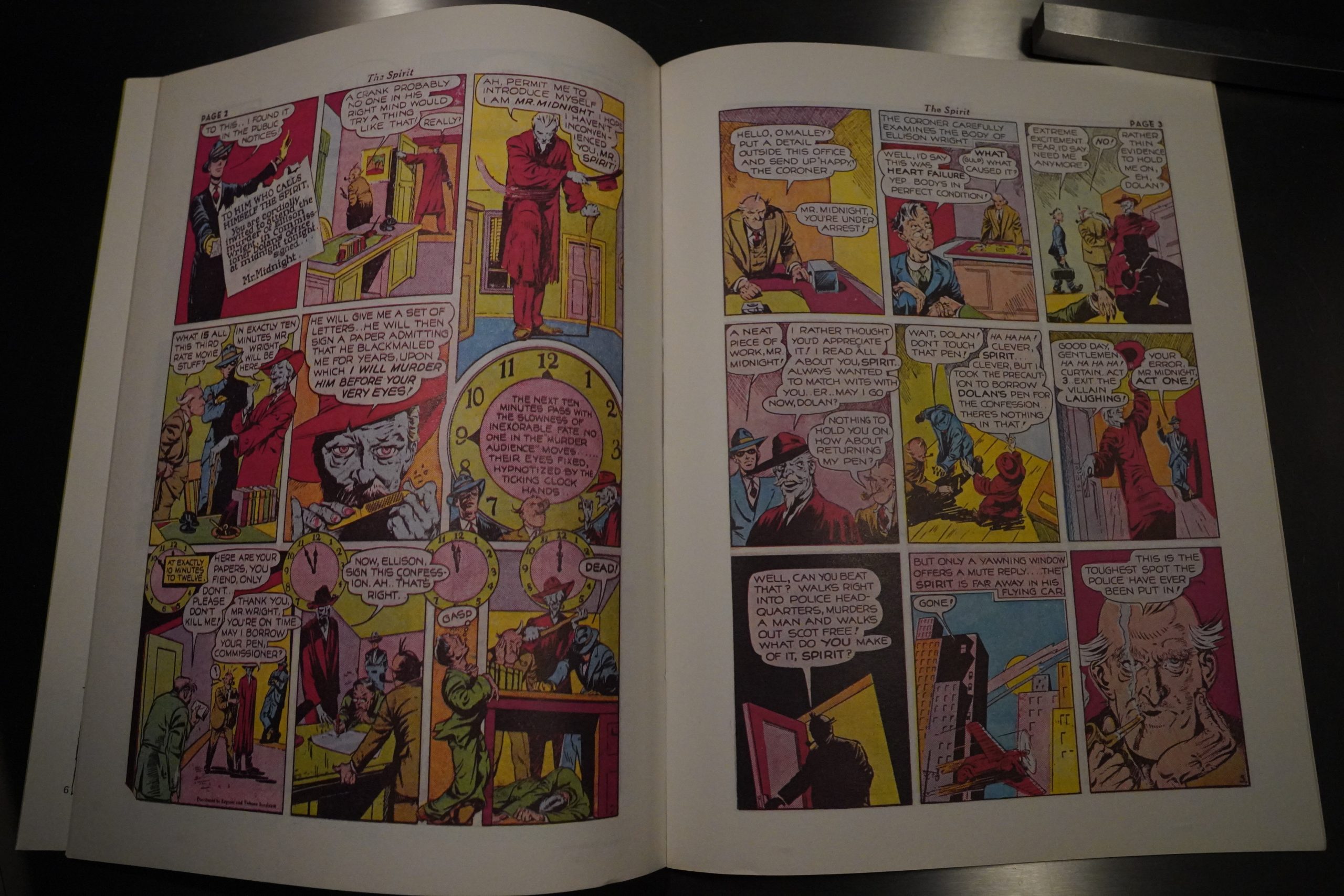

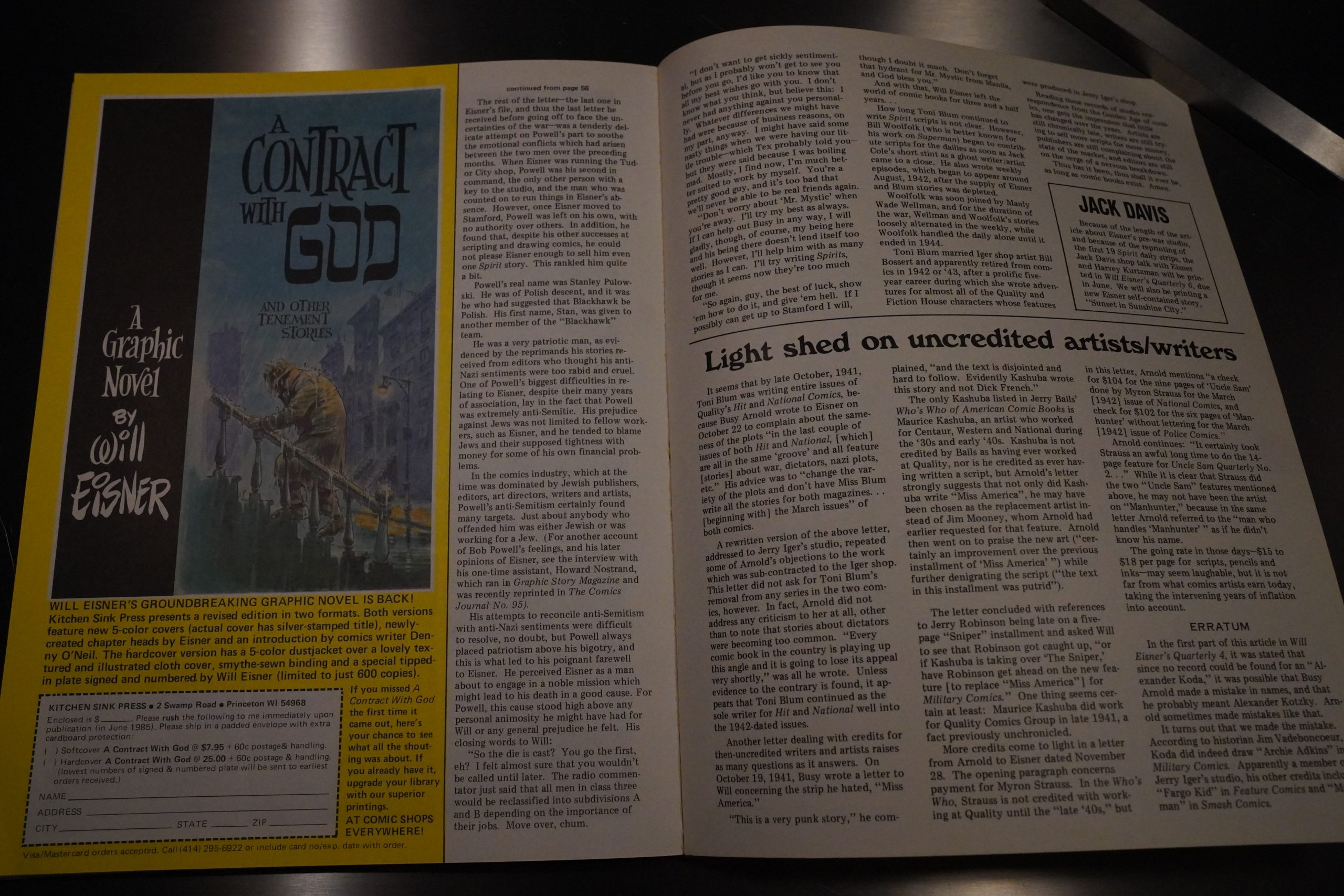

Anyway, the Spirit magazine had been a pleasant mix of random Spirit stories and… well, whatever Eisner wanted to do. So you got illustrations, serialisations of new work, and whatever. It worked quite well, I thought. But The Spirit was relaunched as a comic book sized bi-monthly (later monthly) 32 page book, with no room for the other Eisner stuff, so Kitchen created this book to carry on the er spirit of the Spirit magazine.

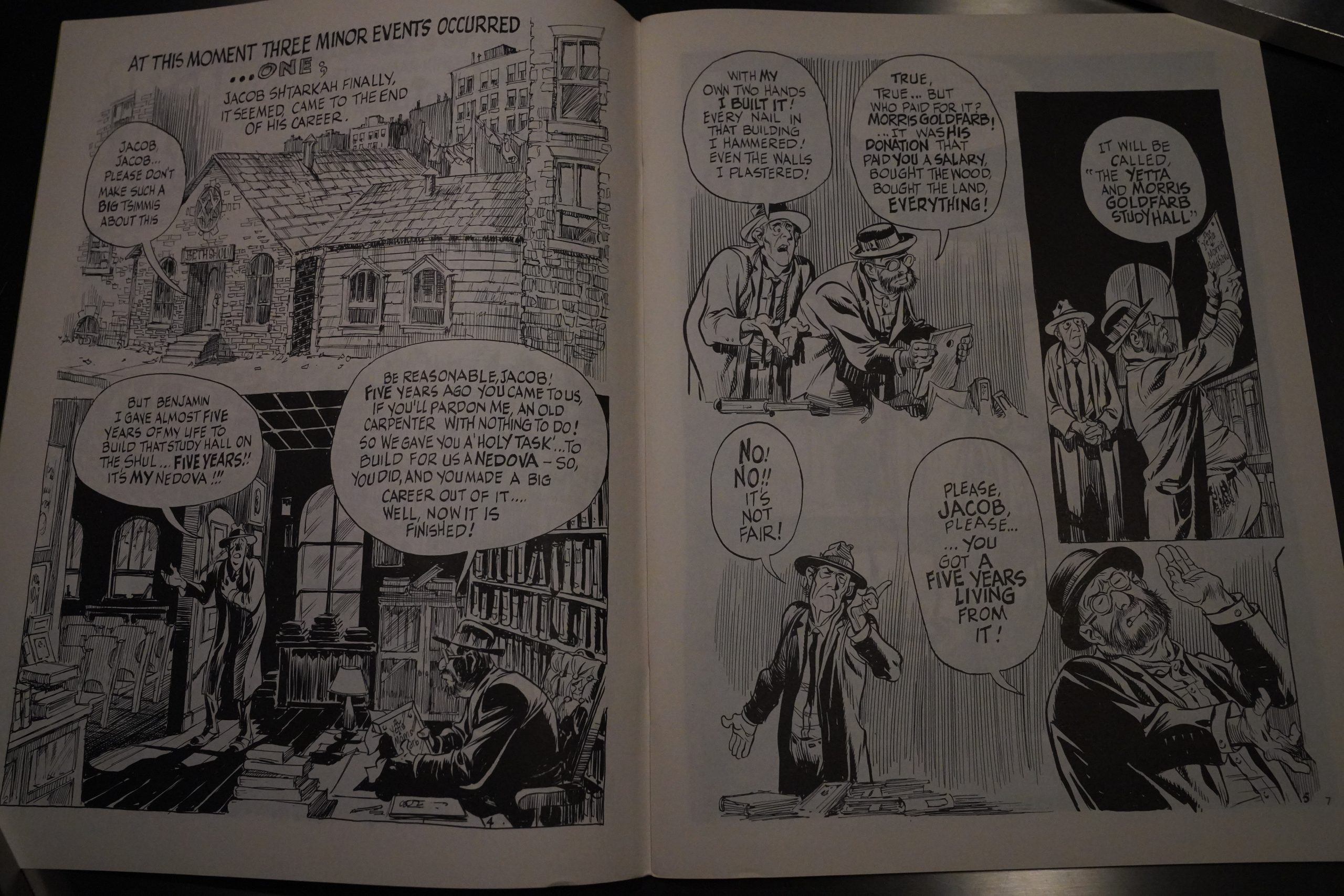

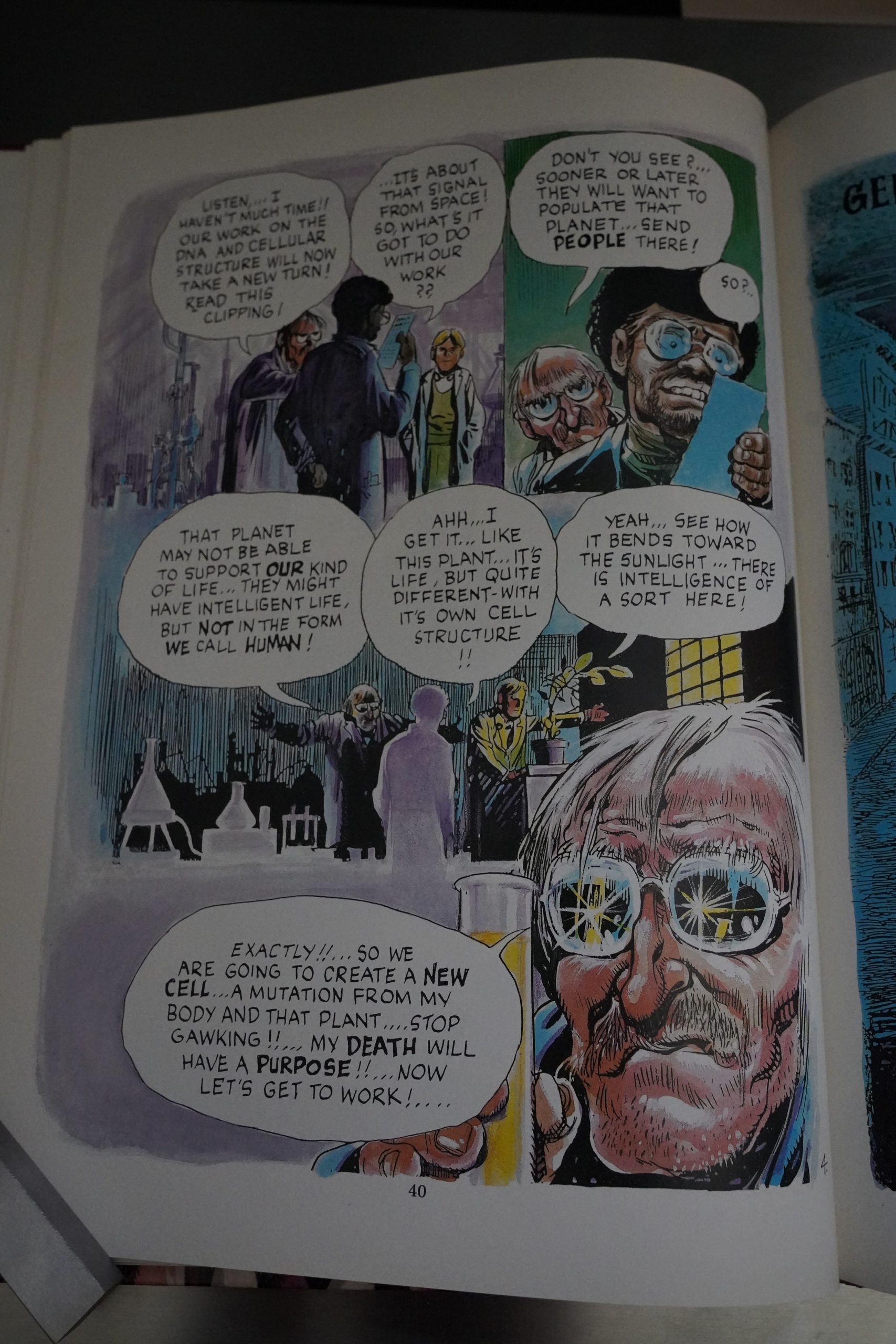

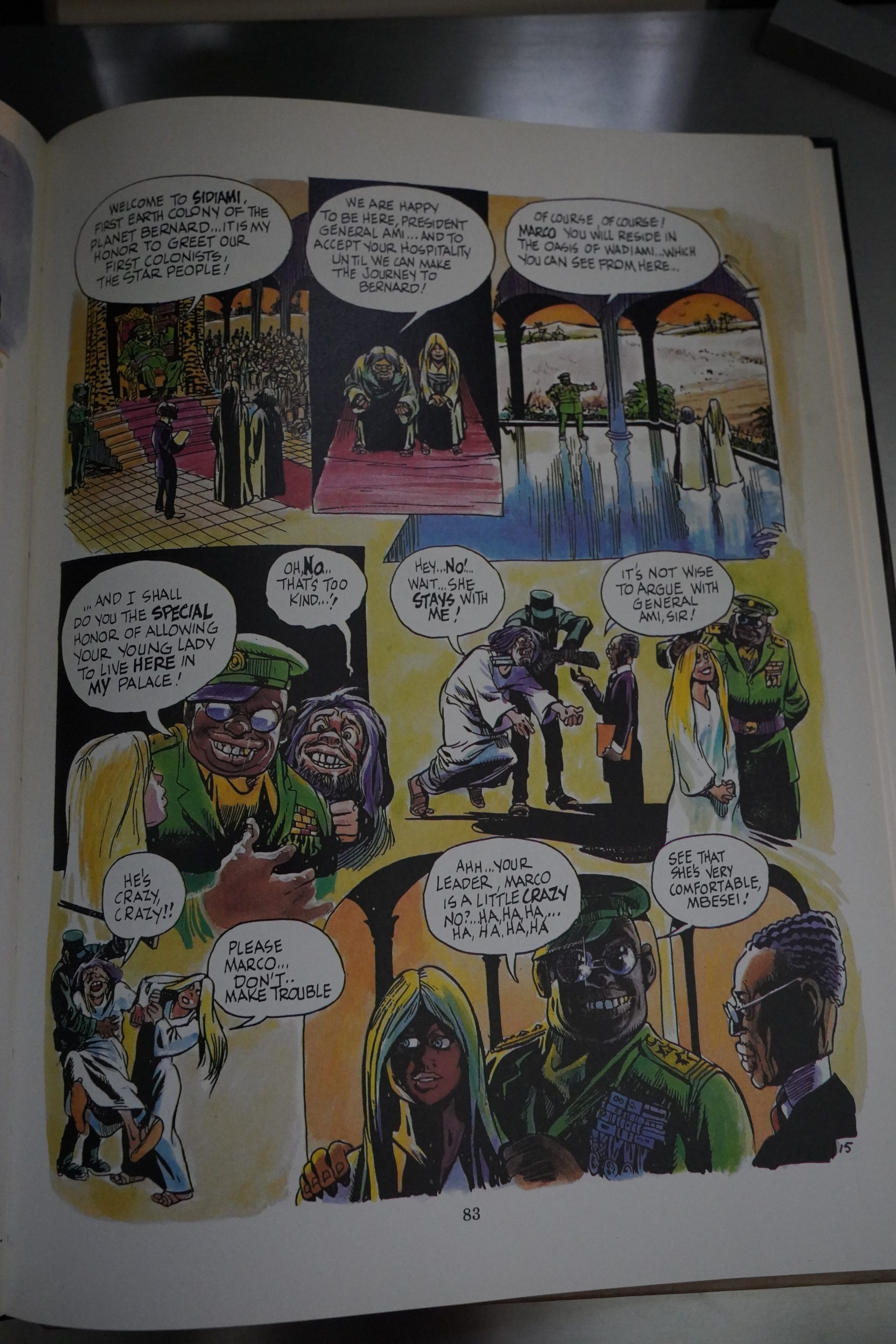

So we get a serialisation of the current Eisner thing (in this case A Life Force, which ran for six of the Quarterly issues). (I’m not re-reading this bit now, because I’ll be covering A Life Force when I get to that as a collected book.)

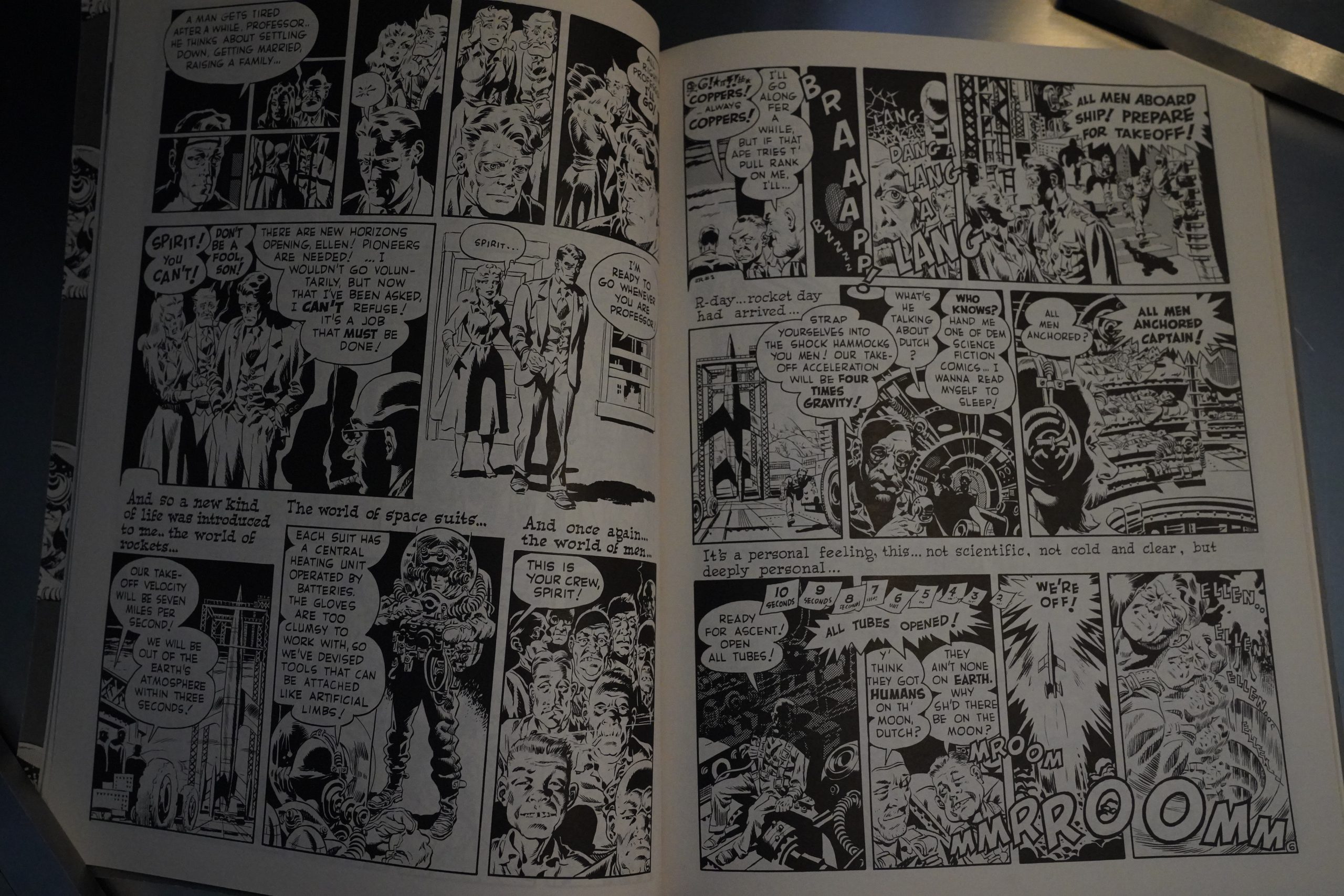

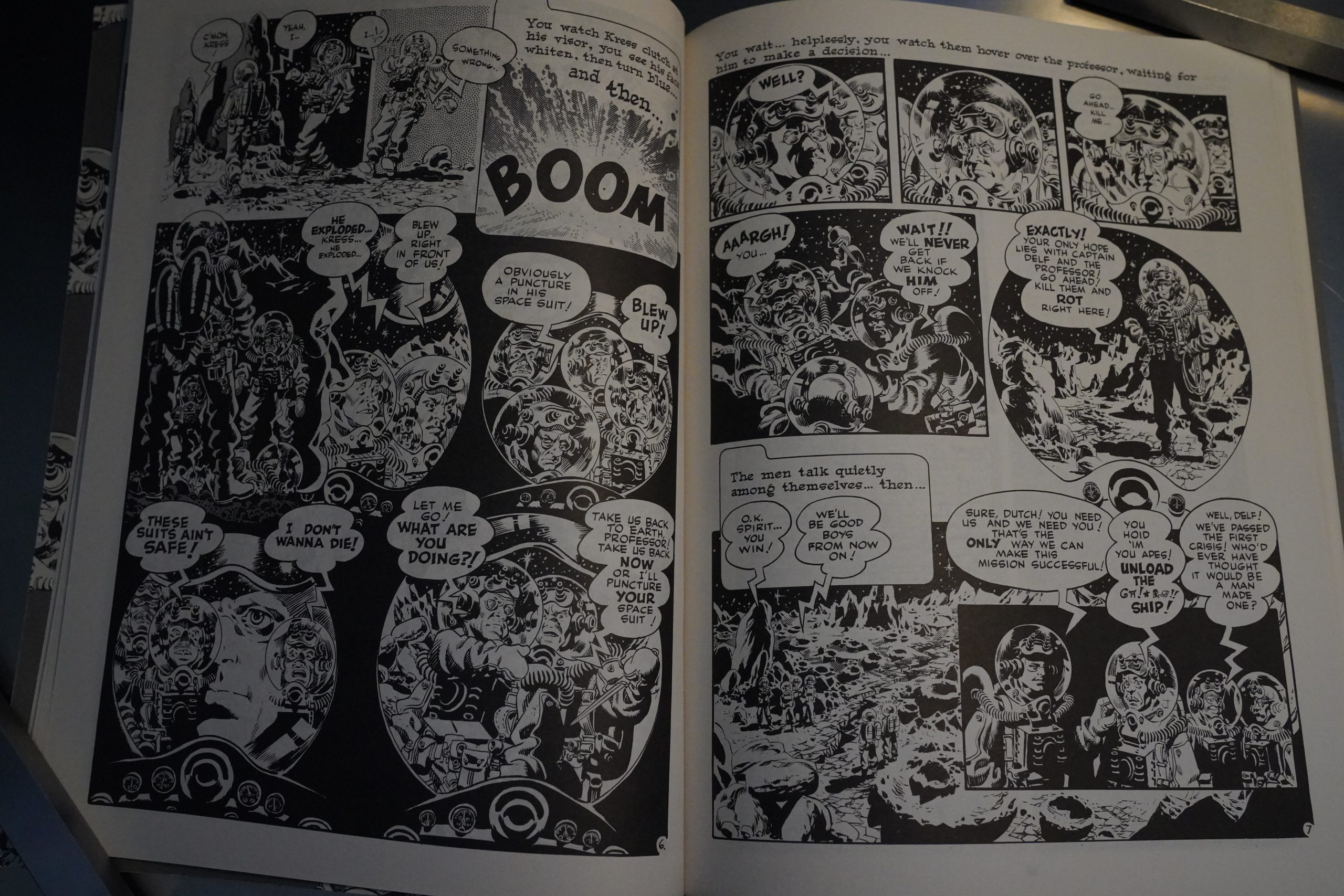

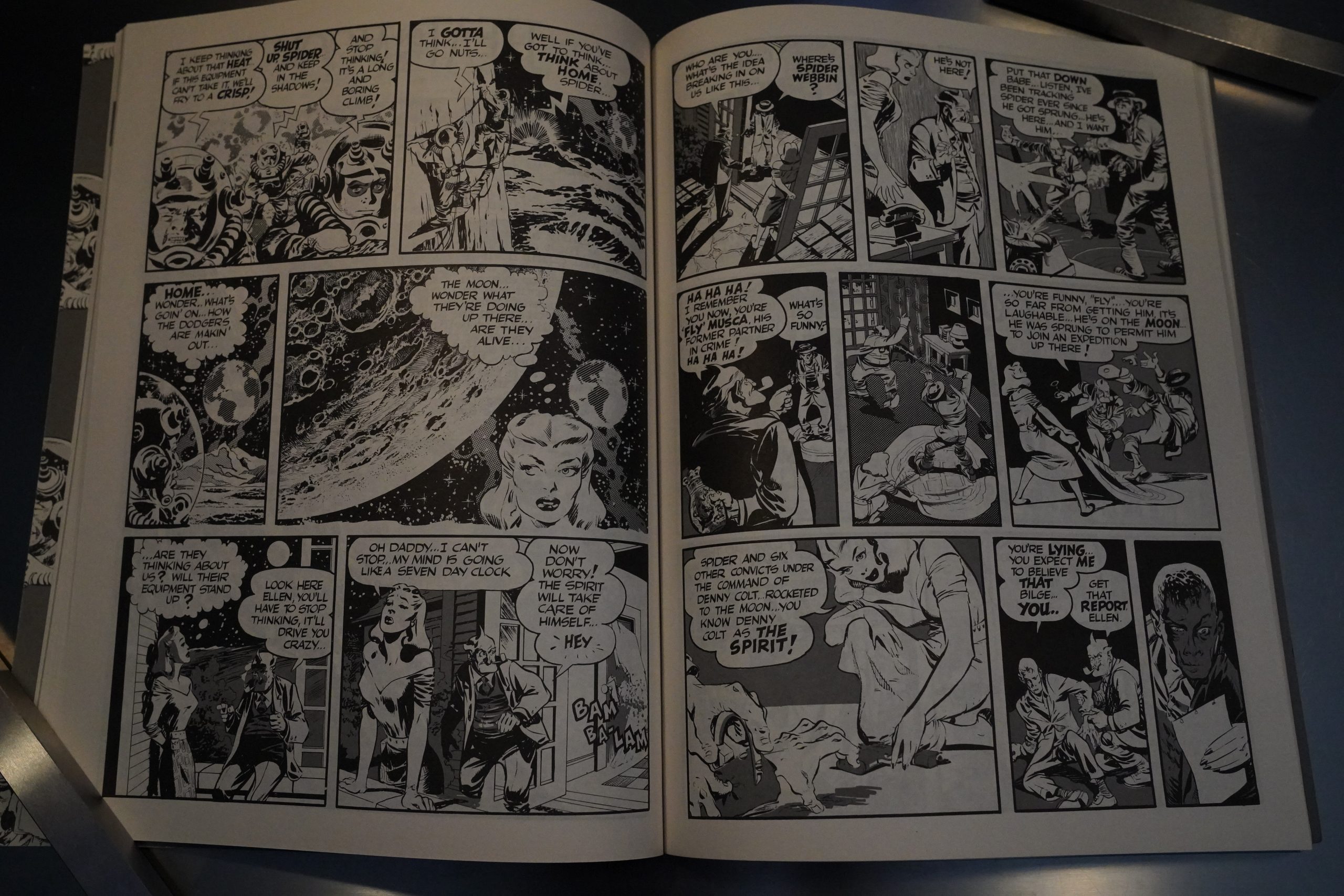

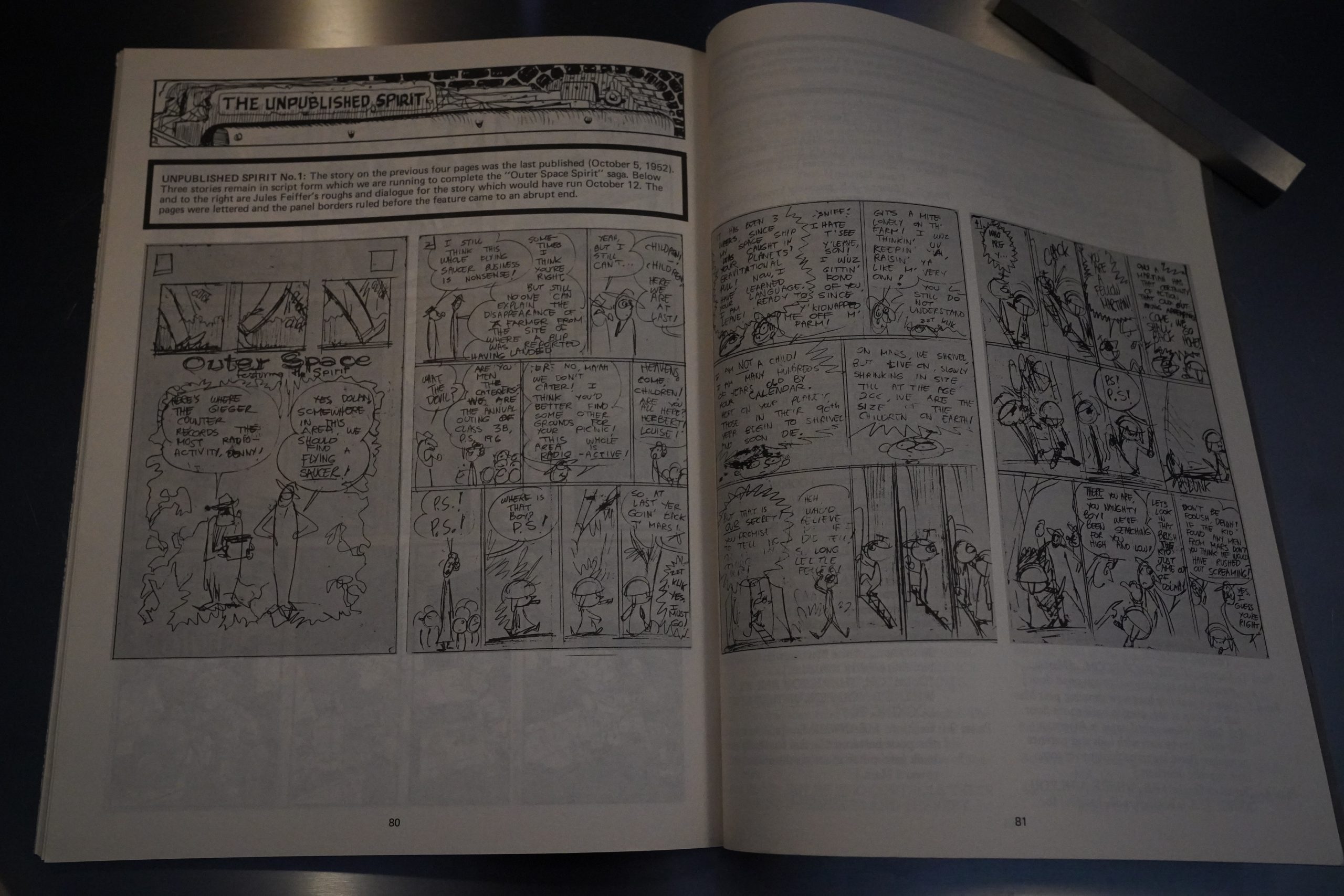

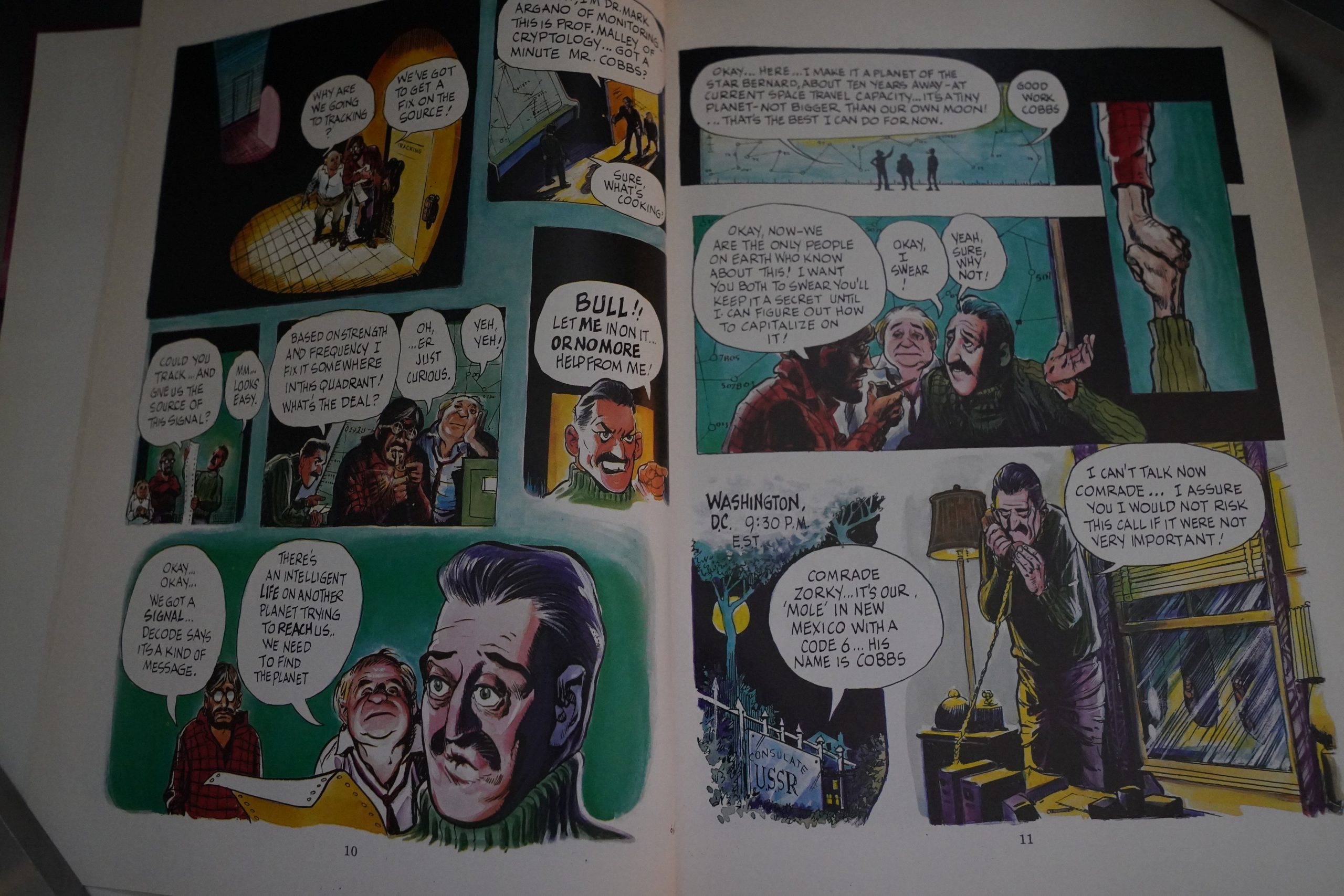

And then we get reprints of the (almost) complete 16 page Spirit newspaper inserts, starting with the first one, and continuing chronologically. So not only The Spirit…

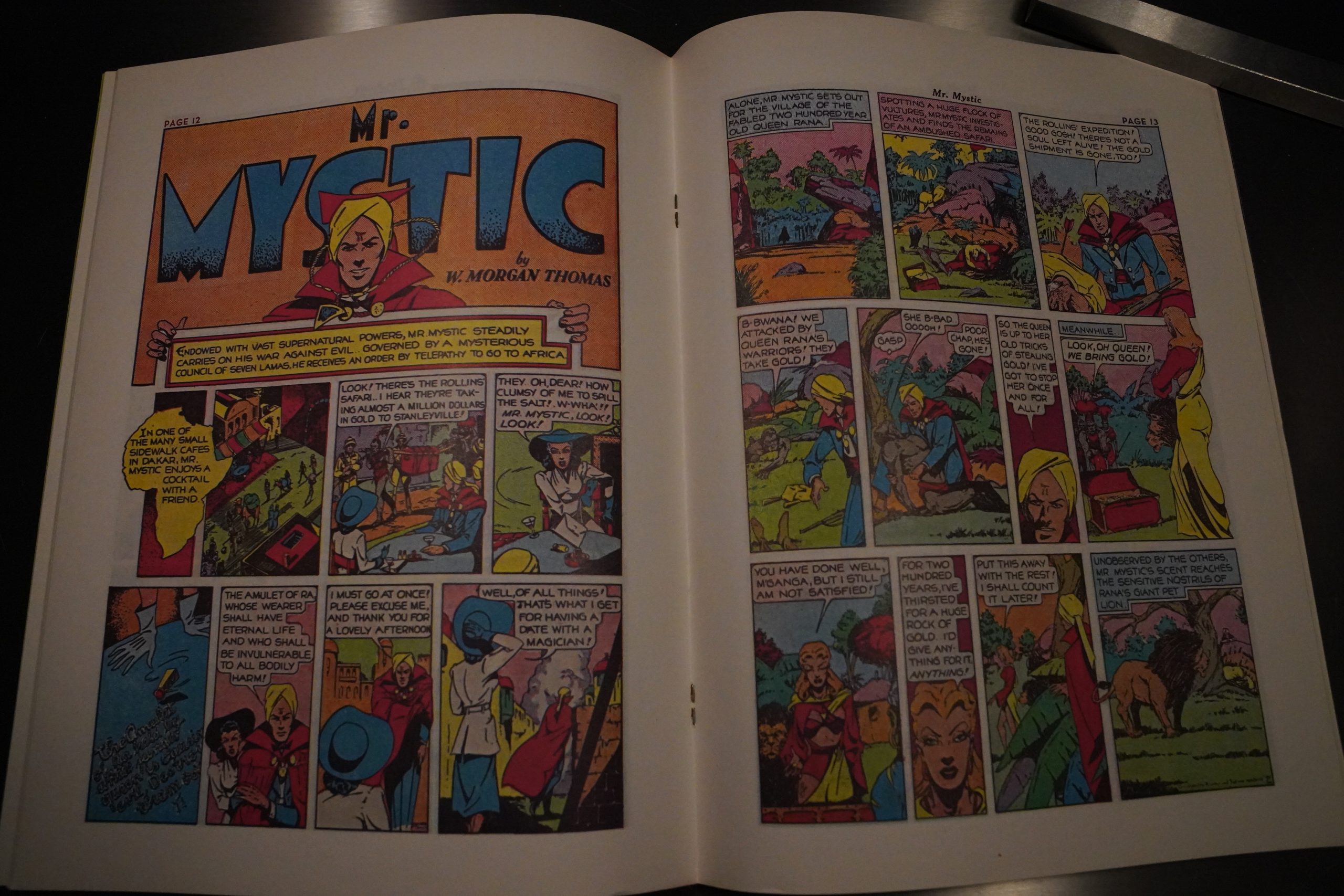

… but also the other features, like Mr. Mystic.

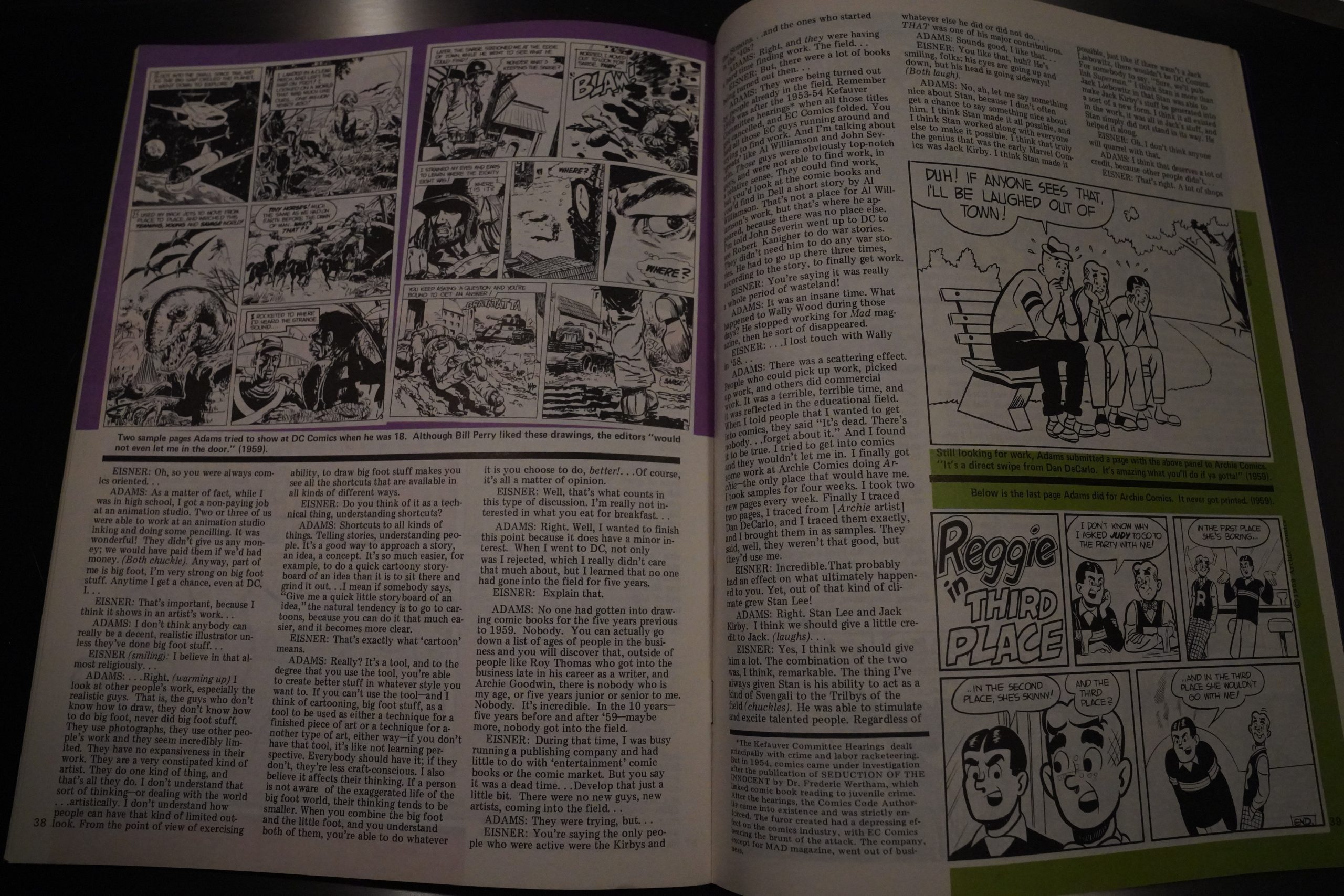

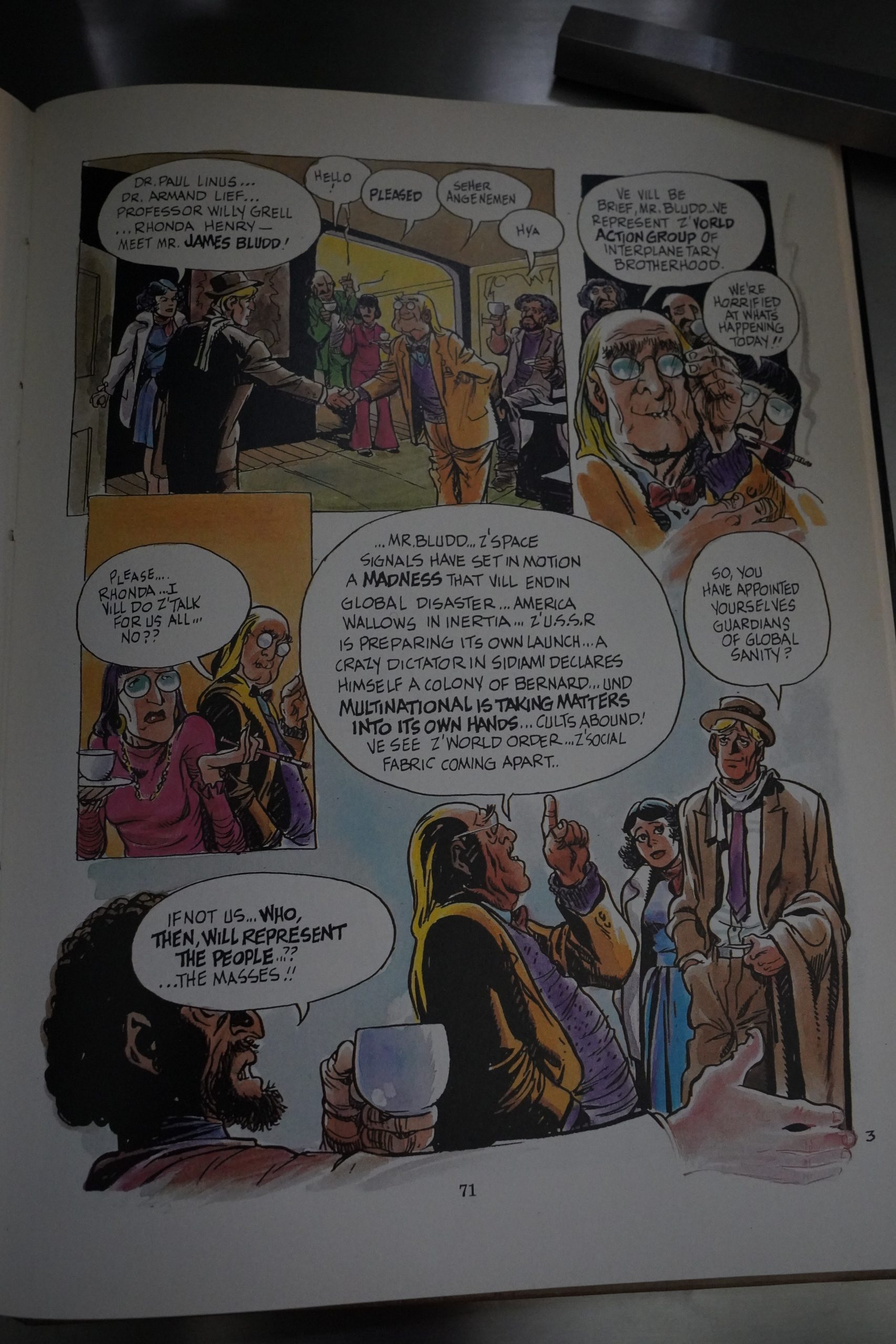

And then the third thing in each issue is the “Shop Talk” thing, where Eisner interviews some other artist.

It’s a pretty good package? But… while the Spirit magazine had all these random things, we get exactly these three things, and only these three things, for the first few issues. So it’s more, dependable, mature, and feels a bit staid.

And I guess it didn’t sell all that well, because with the fourth issue, the magazine goes squarebound, and ups the price to a then-scandalous $6. Knowing how stingy comics people are, this seems like quite a gamble.

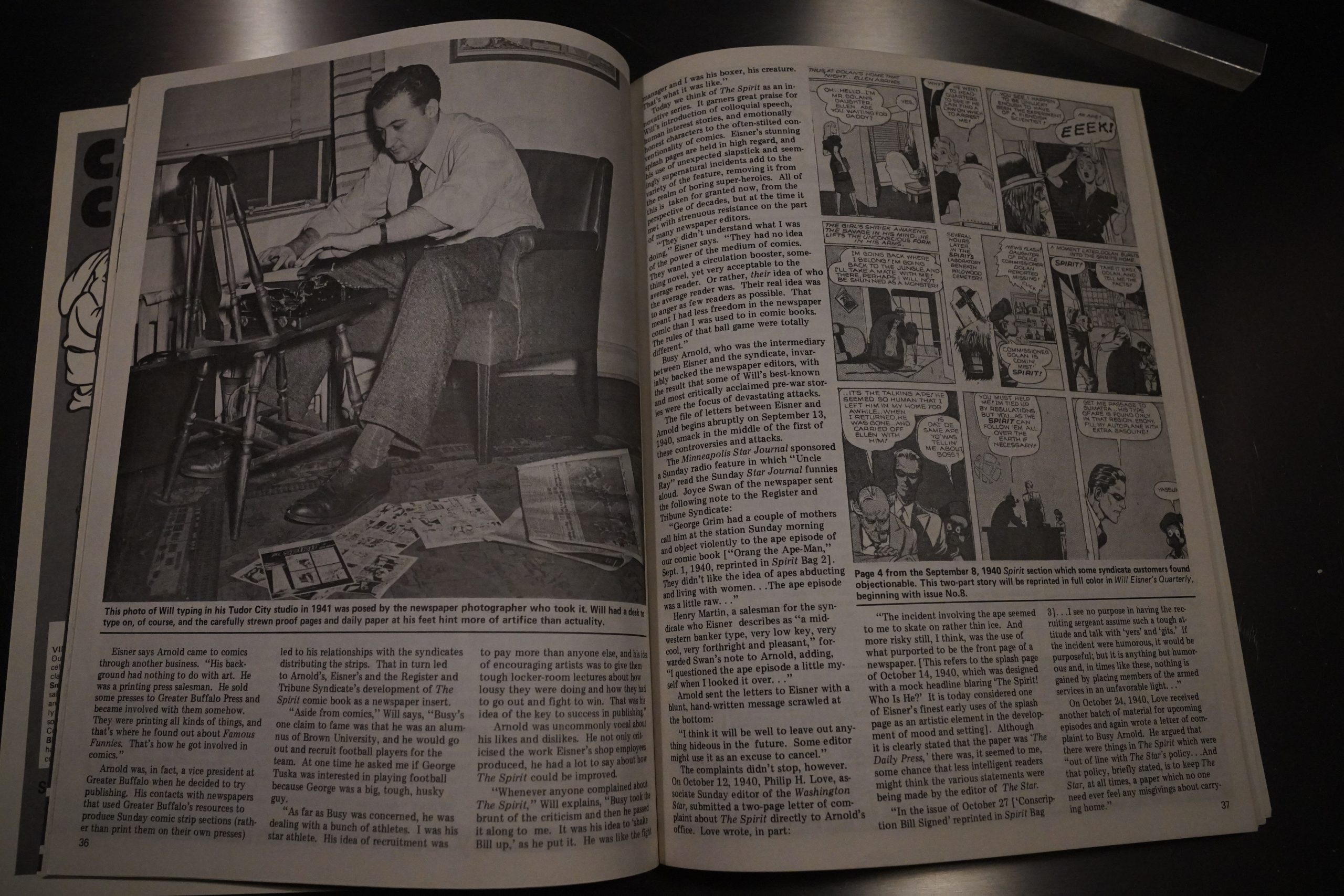

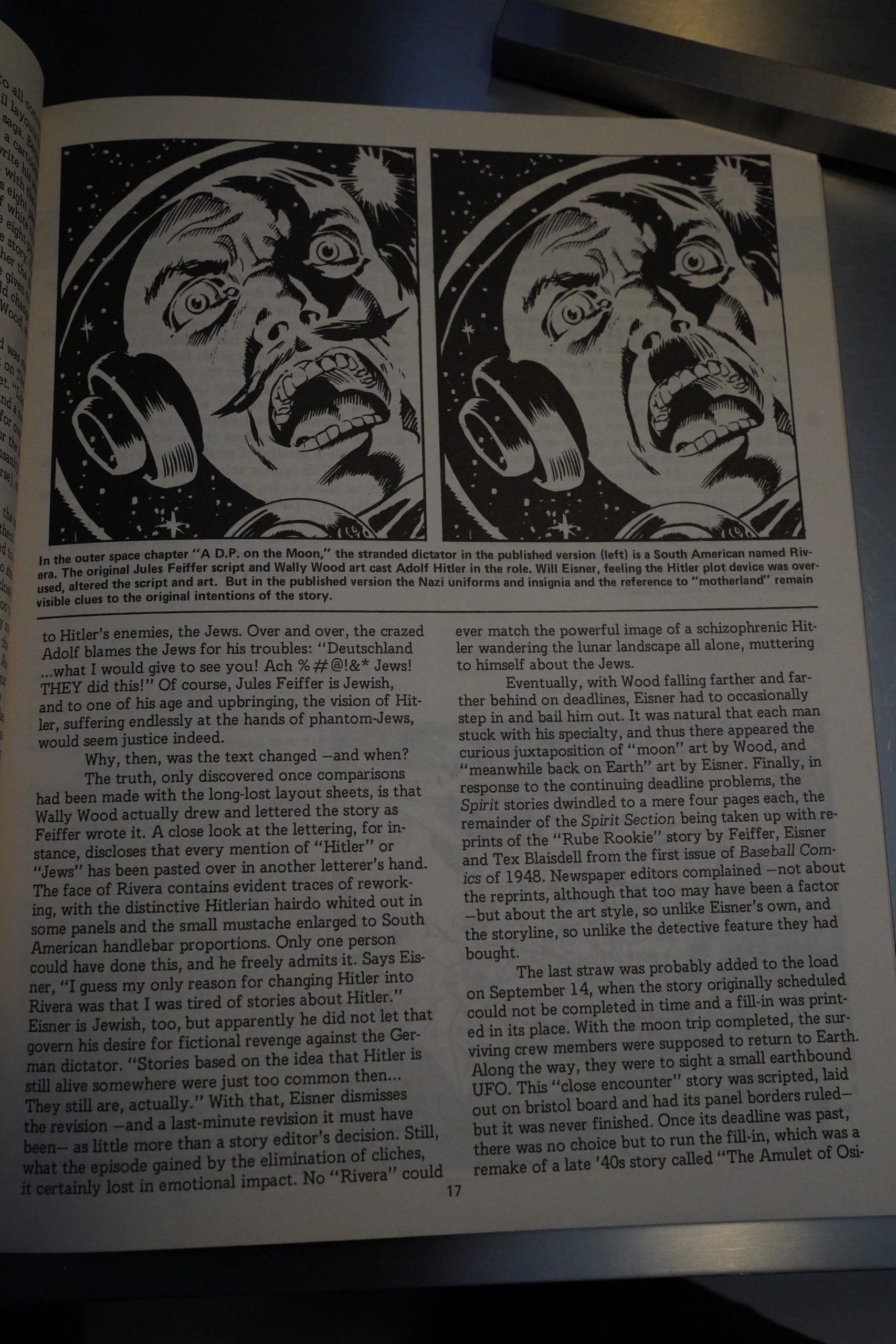

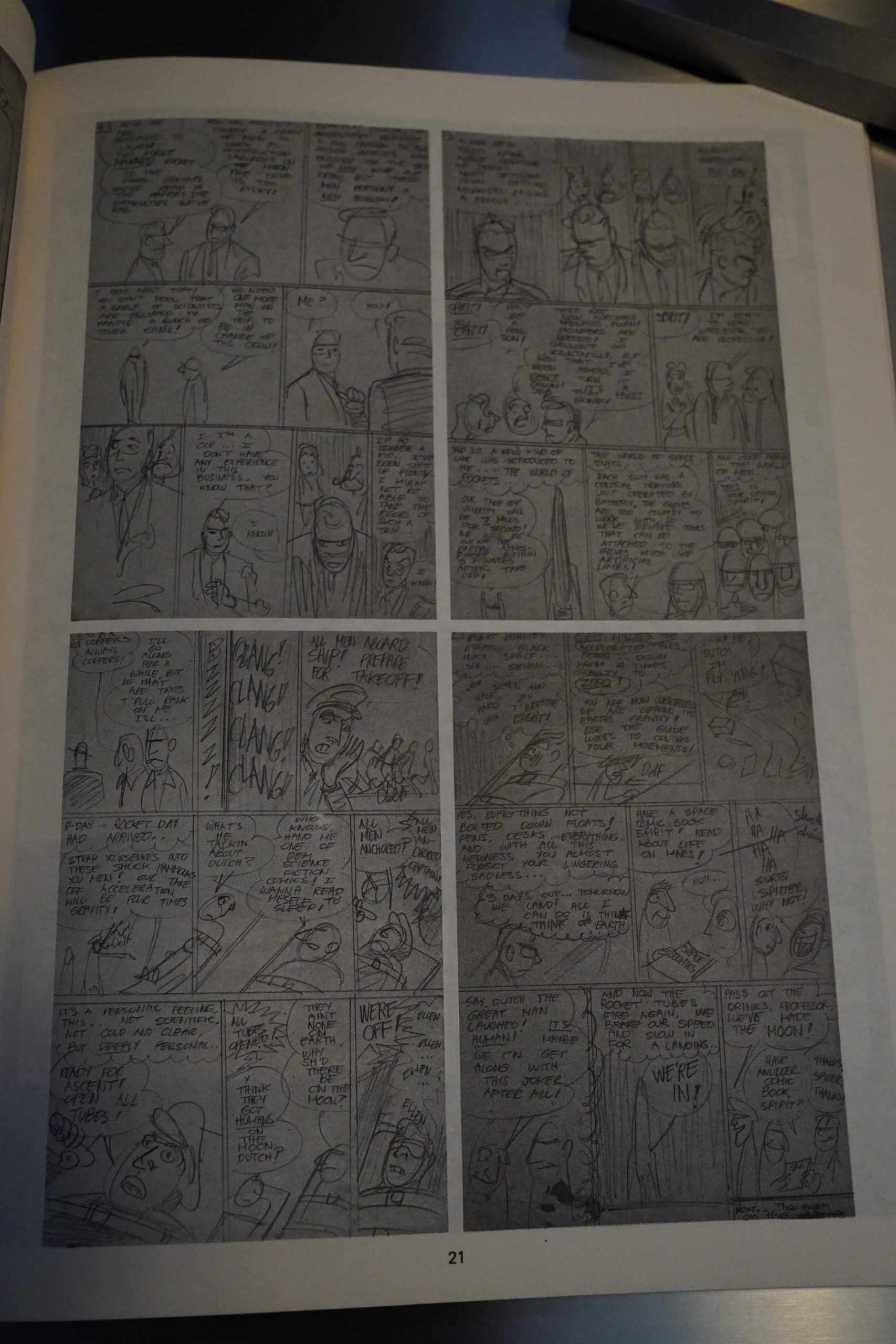

But the increased page count allow them to run features like this, where Cat Yronwode has a peek at the business correspondence between Eisner and Busy Arnolds, and it’s quite entertaining (and interesting).

However, by the second instalment, I was really starting to fade. Too many details and too many editors complaining about the strip being too anti-Nazi.

The concluding bits about Bob Powell are interesting, though.

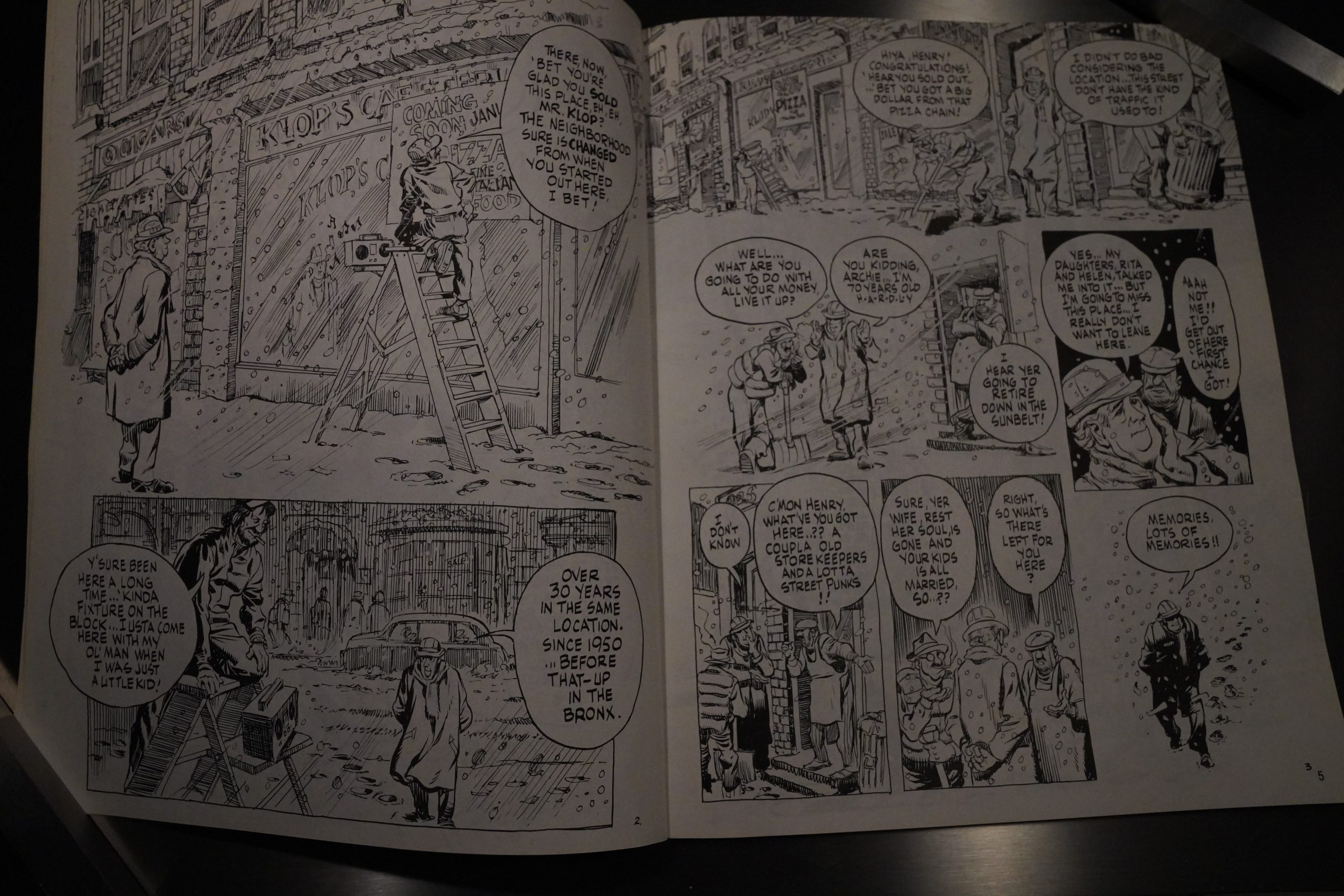

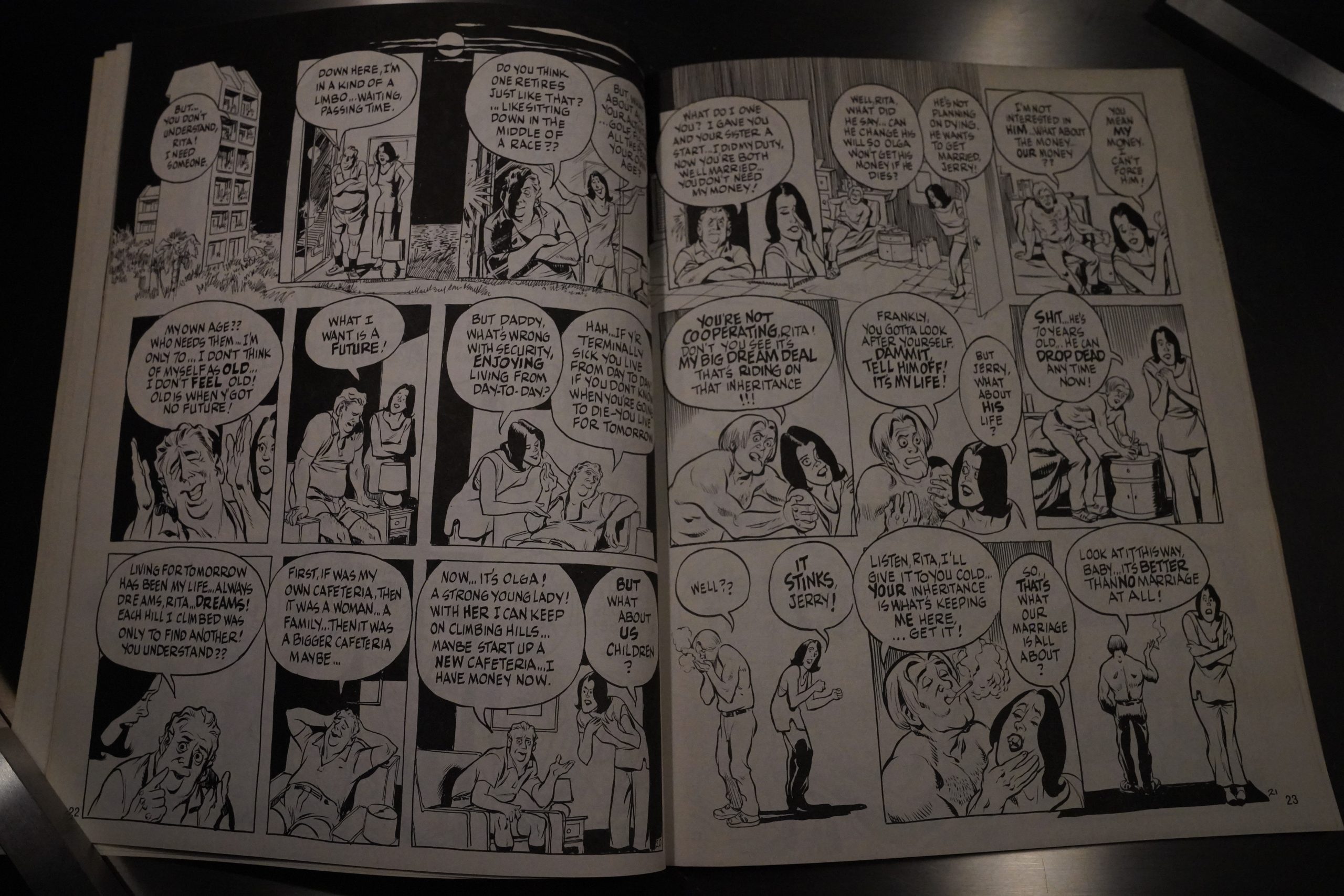

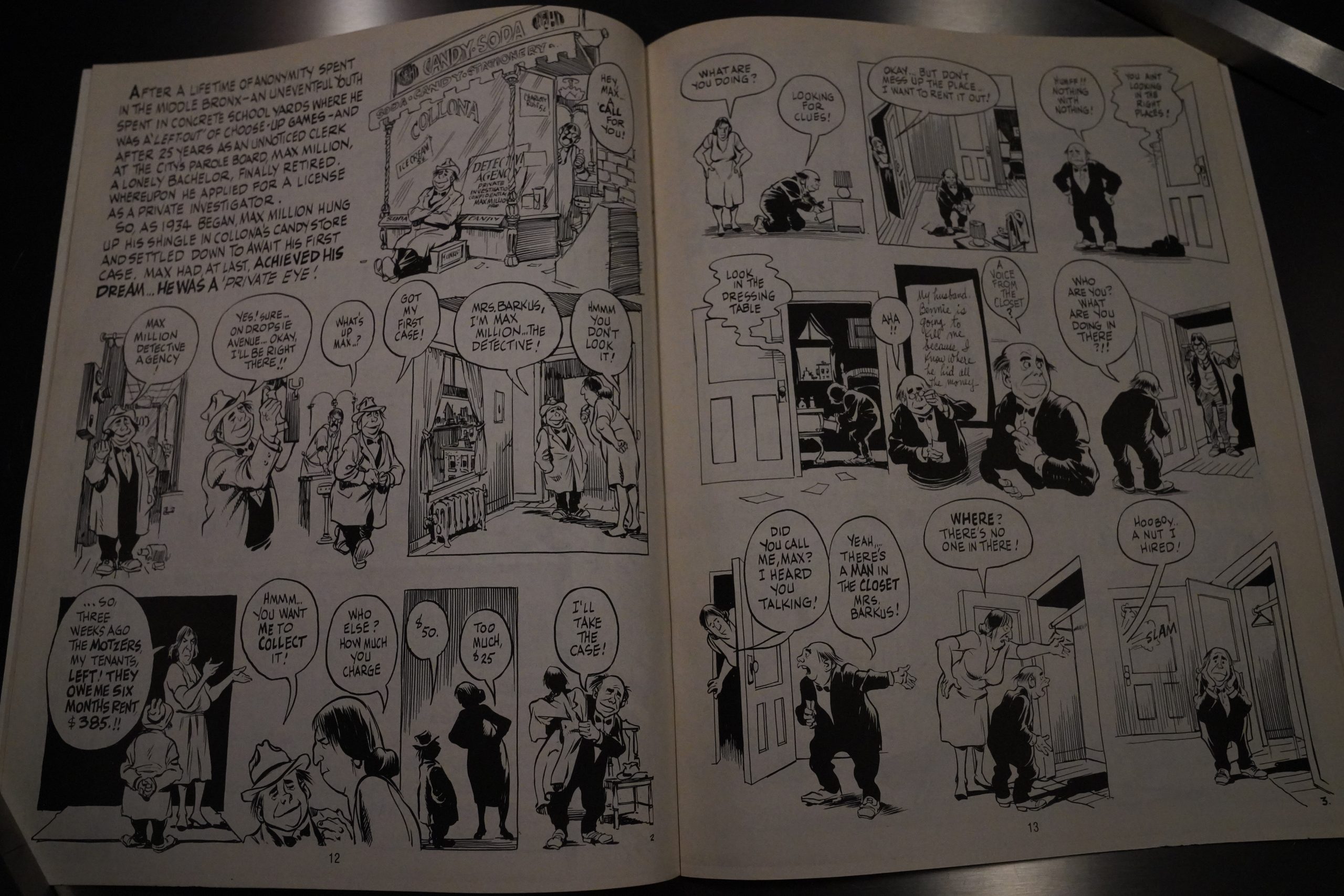

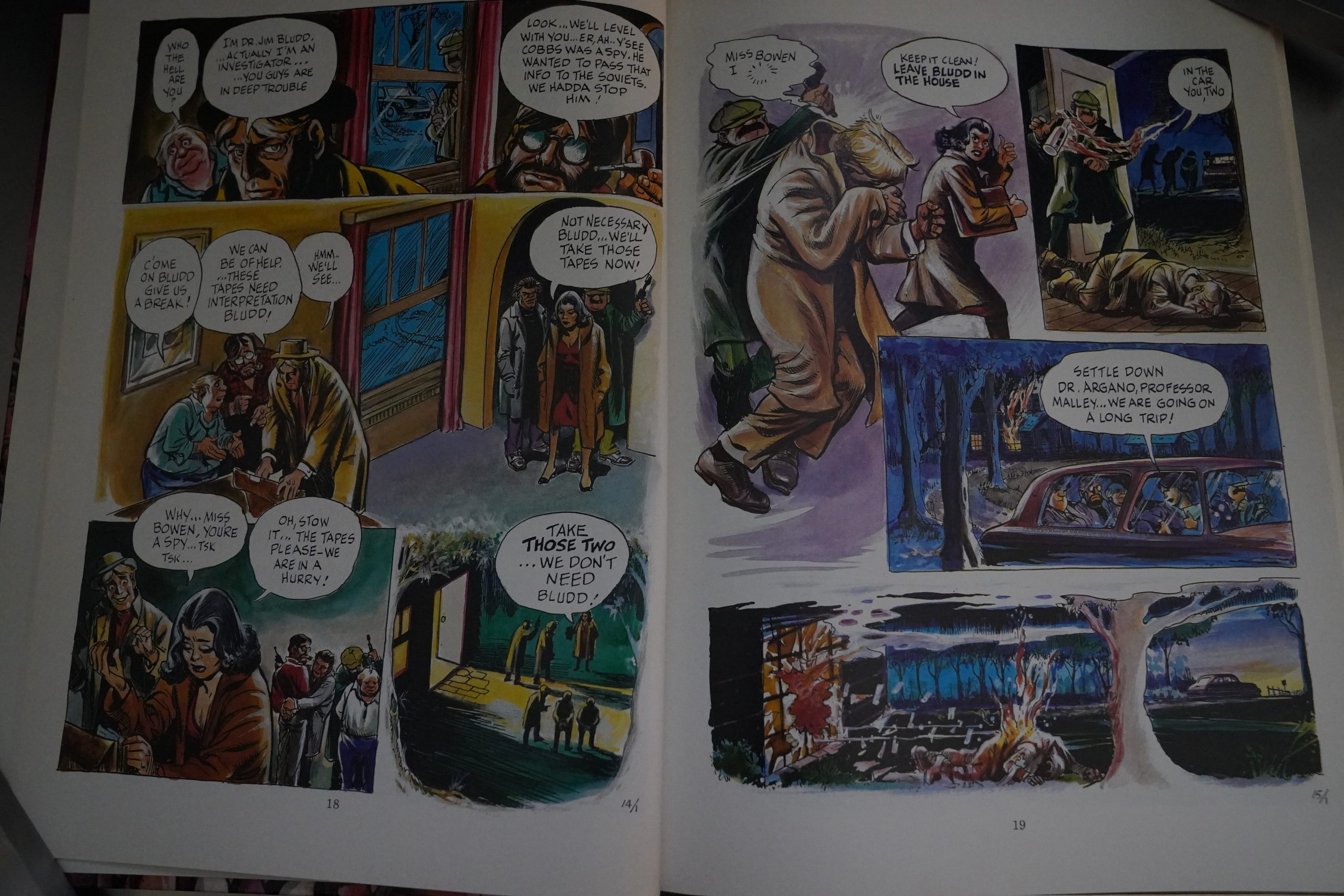

A Life Force concludes, so we get a number of shorter (I mean, less than 30 pages) things. Nice artwork, eh?

And the story seems like it’s going to be all pathos and stuff, but it’s got an amusing twist ending. Well, Eisner usually does that, with varying degrees of success, I guess.

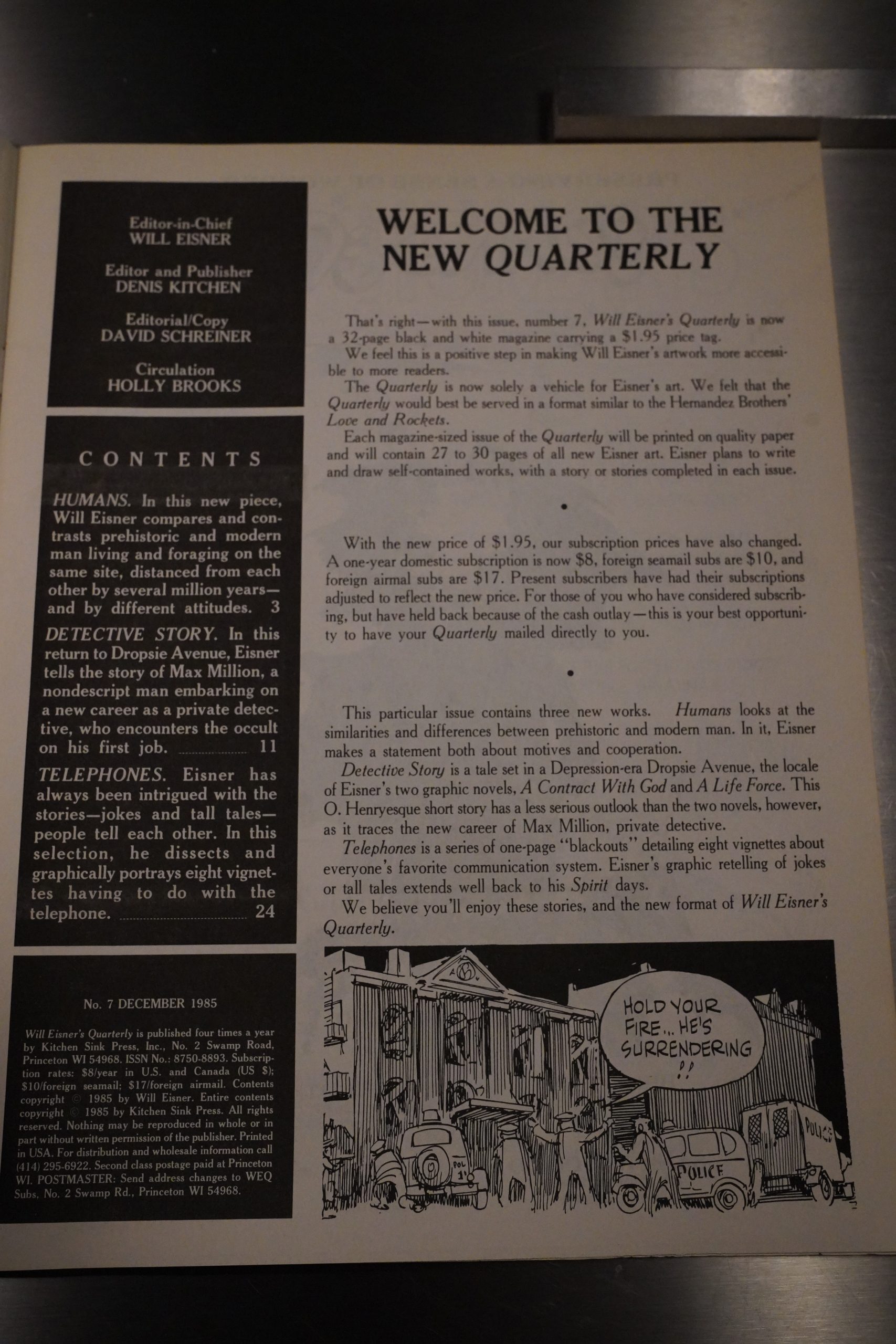

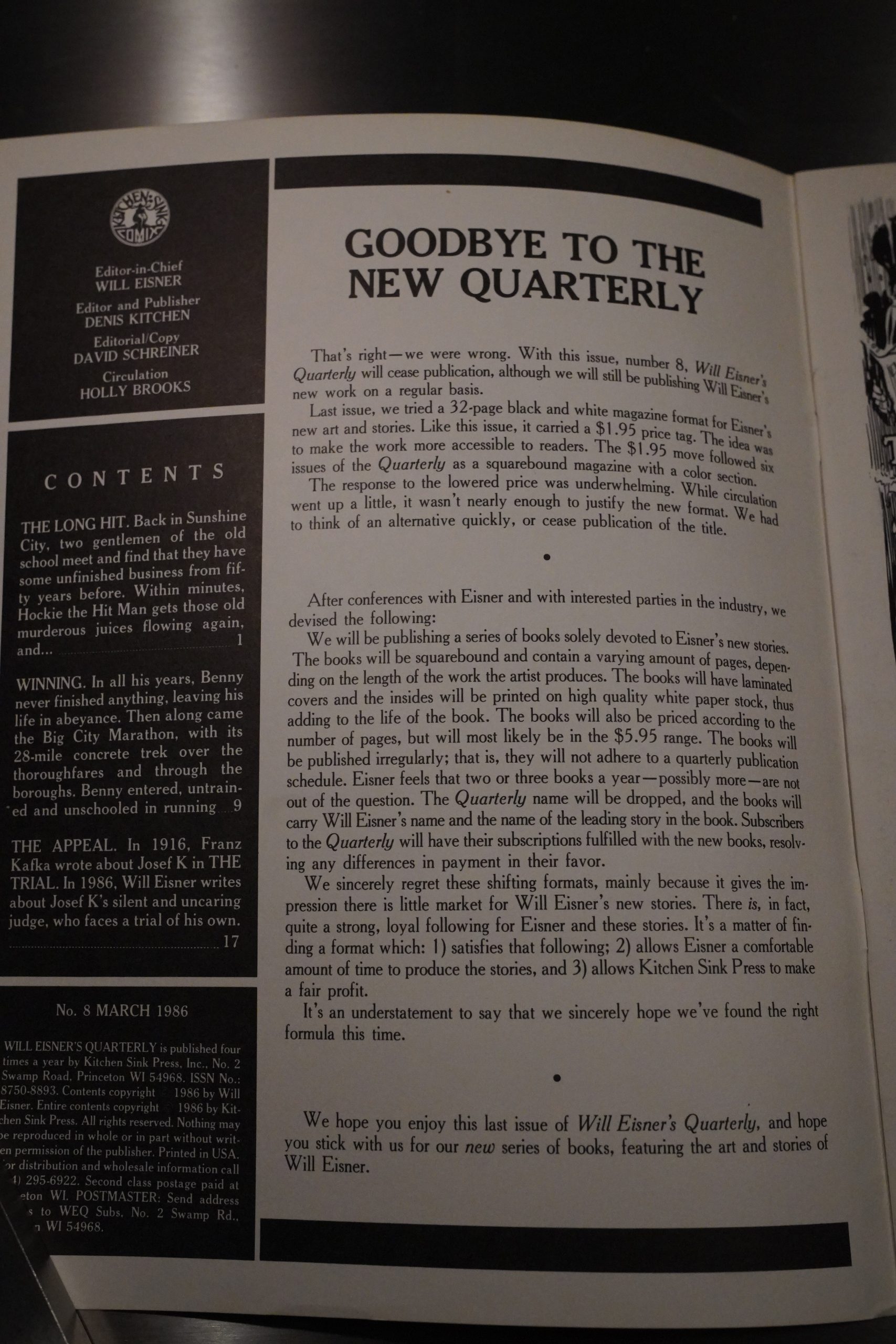

Another format change! Shocker: People weren’t up to paying $6 for a quarterly magazine after all, so it moves to a slimmed-down stapled format again. I find it interesting that Kitchen namechecks Love and Rockets as the model for the format…

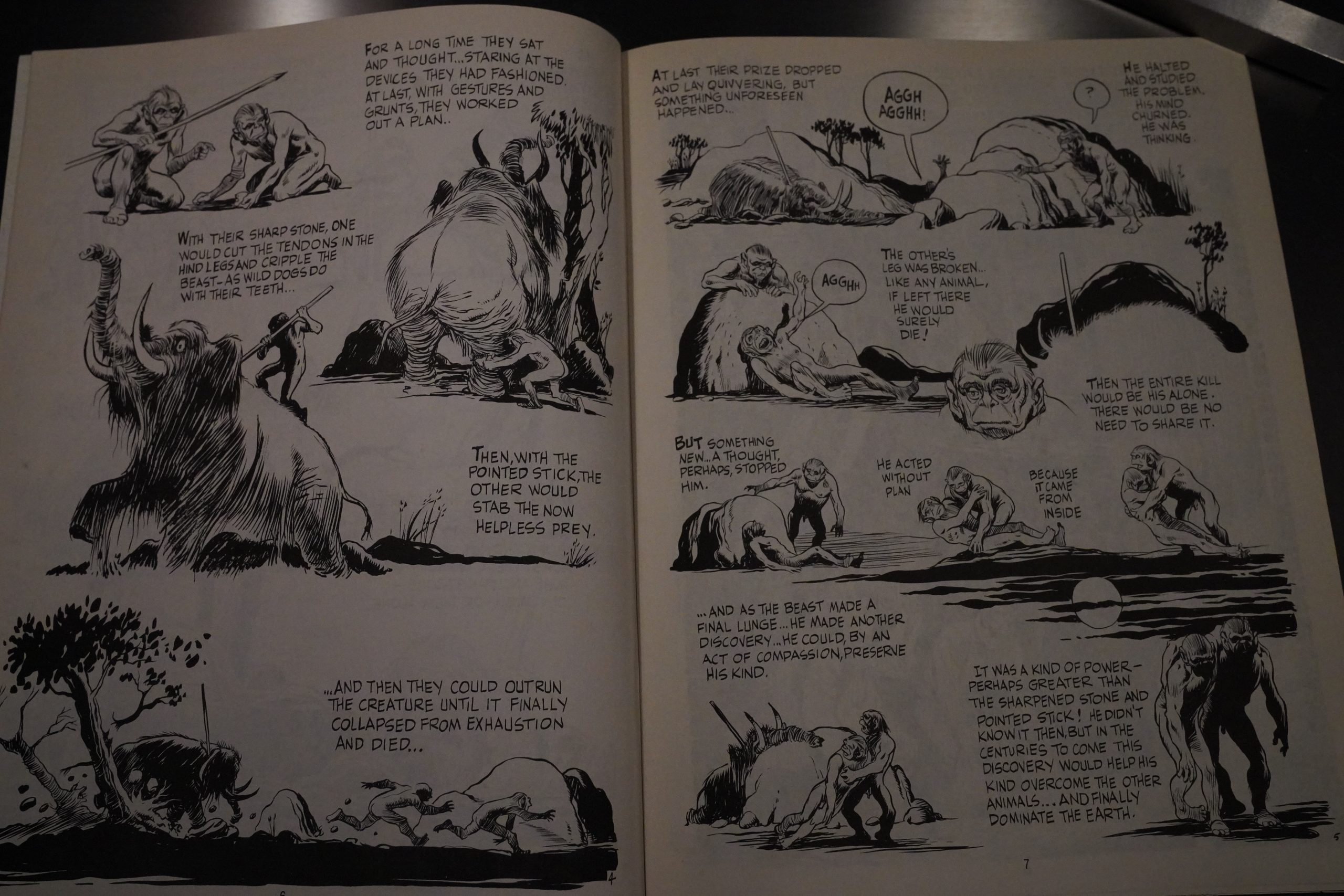

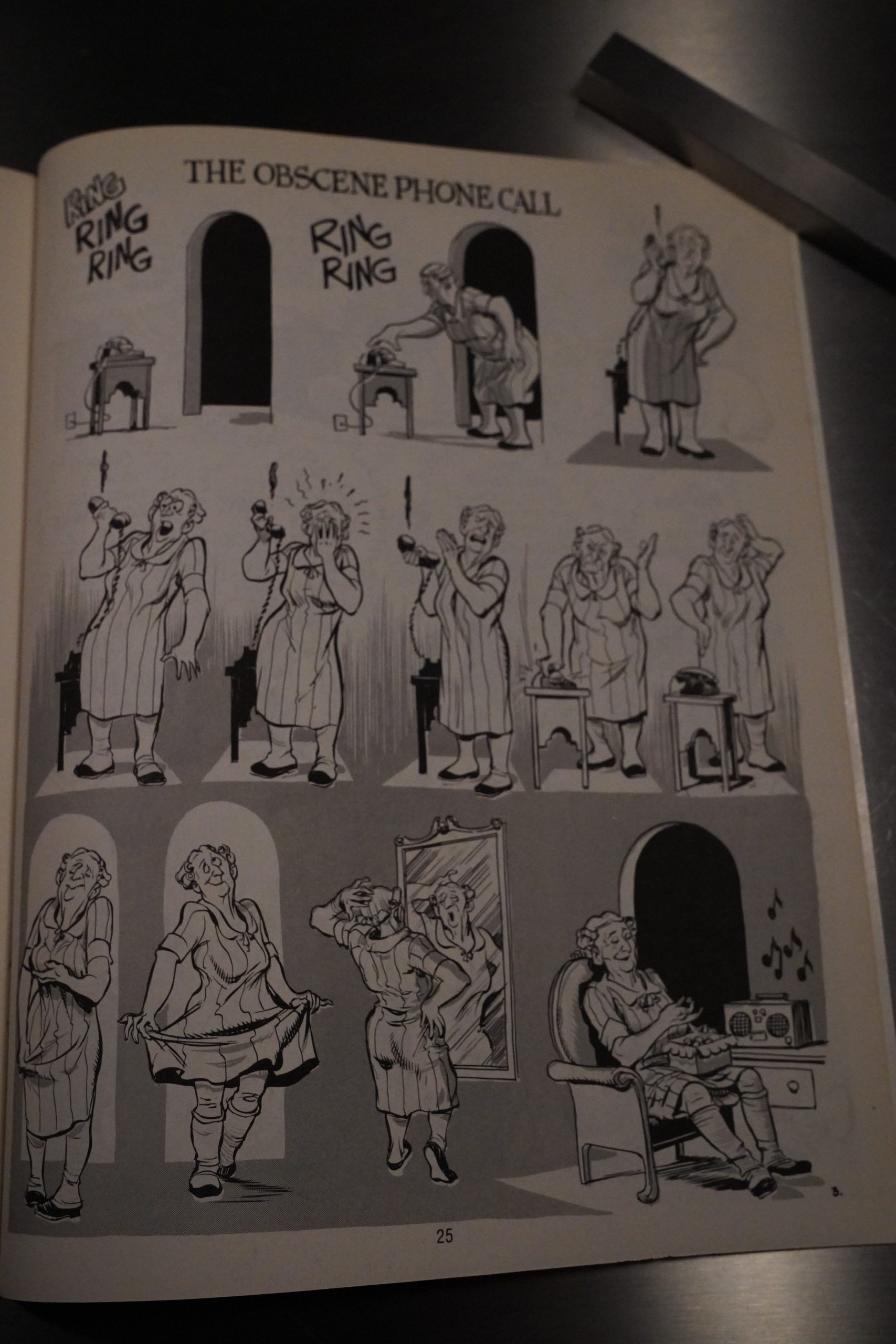

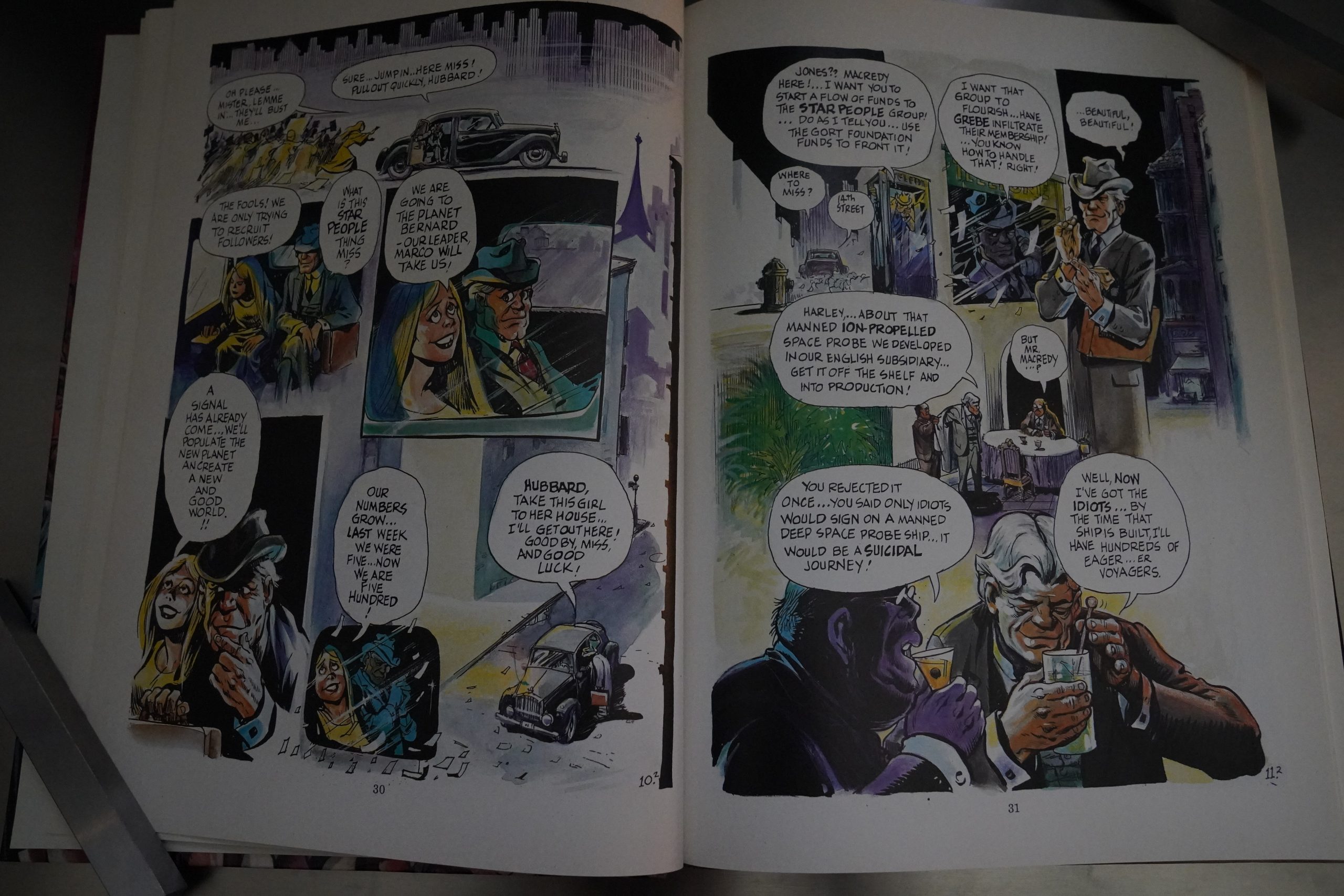

So we get a number of shorter, self-contained stories in the two remaining issues.

Most of them are surprisingly entertaining.

But they can’t all be winners.

No, even dropping the price to $2 wasn’t enough. From now on, Eisner’s work is going to be dropped as graphic novels only, without serialisation.

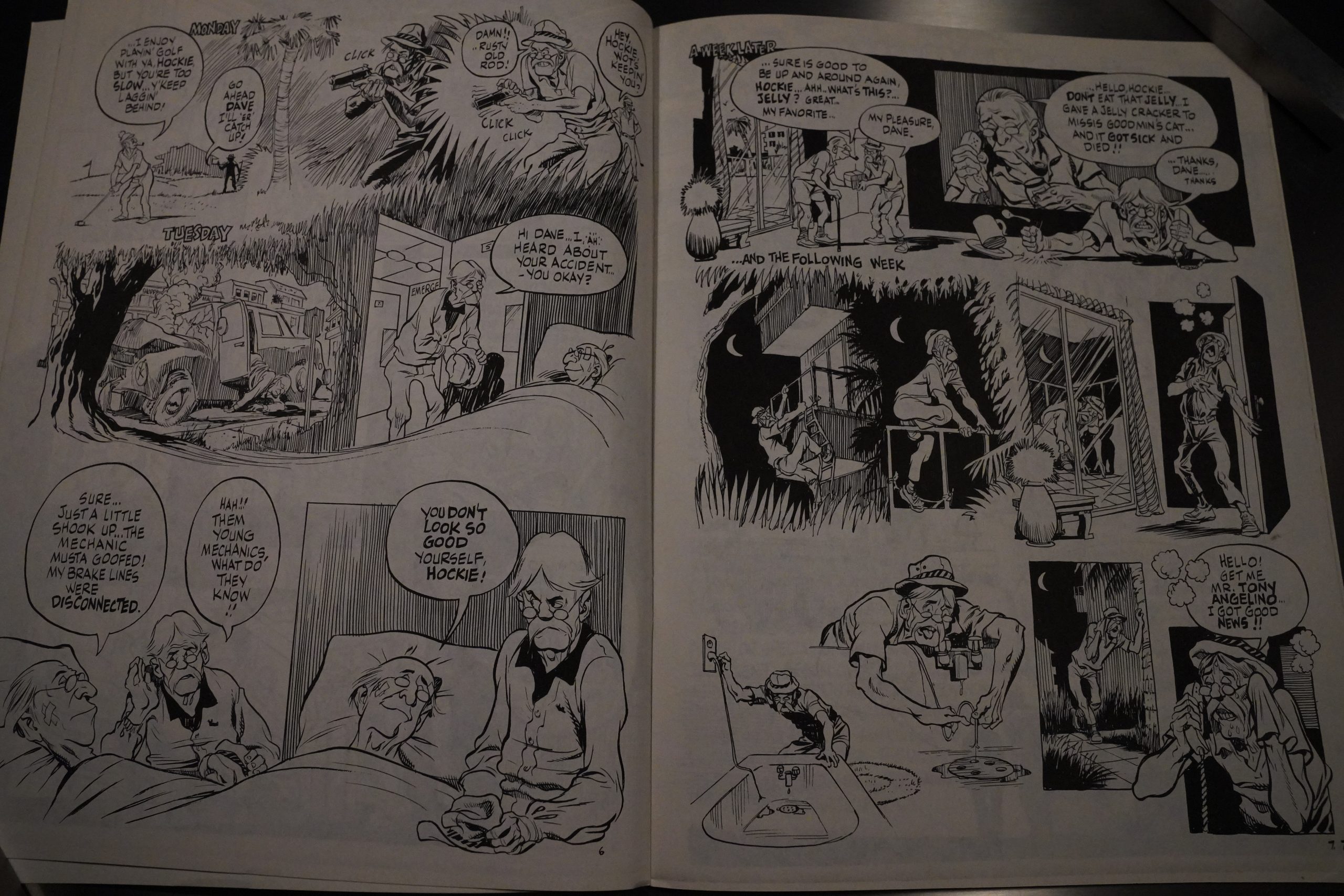

Rounding out the series, we get an amusing thing about a geriatric hit man…

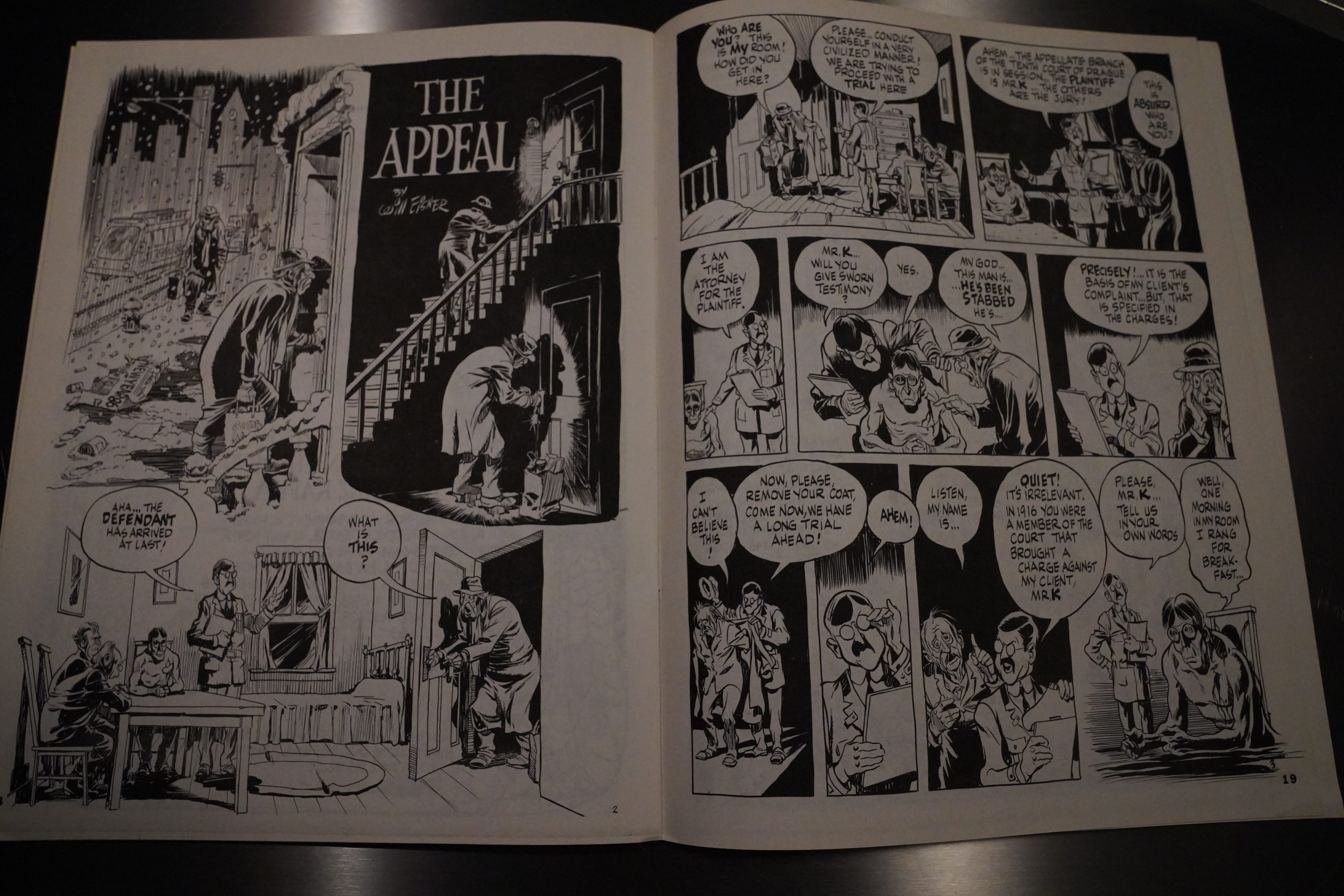

… and a sequel to Kafka’s The Trial that’s… not as successful.

Bill Sherman writes in The Comics Journal #92, page 66:

I write this, however, with a profound

sense of depression about Quarterly’s

chances of finding and keeping a large

enough audience willing to follow the art-

ist. Childishness definitely outsells

everything else; witness mainstream com-

ics’ -biggest titles, Quarterly may hope to

hook part of that audience with its token

color section (one Spirit and one Mr. Mystic

but it hopes to hold them with the

work of an unashamedly maturer artist. Is

there a comics • shop audience capable of

supporting sequels to the rapidly remain.

dered A Contract With God? The prospect

looks grim.

I hope I’m being needlessly pessimistic

here because, on the basis of Quarterly’s

premiere, Eisner appears to have finally

found a means of tempering both the melo-

dramatic strain that marred Contract’s

tempts at ’30s naturalism and the free-

floating pretentiousness of his short city

pieces in Spirit Magazthe. With “A Life

Force,” Eisner gives us a seriesof fine-tuned

interlocking character studies set in Con-

tract’s Depression milieu, pieces that com-

bine Eisner’s Characteristic comic book art

style with a range of physical and verbal

expressiveness that humanizes his subjects

beyond the traditional caricature.

Dale Luciano writes in The Comics Journal #89, page 43:

[…]

The material often appears banal—a key

scene in this regard is the carpenter’s

philosophical dialogue with a cockroach in

an alleyway—but then, the banality of

these people’s lives is both Eisner’s subject

and the quality he values most about them.

It’s worth noting that the carpenter, in the

fashion of an inarticulate man musing over

the cruel vagaries of fate, reaches no cone

clusion and says nothing profound. And

the gesture of the man’s saving the roach’s

life, while a bit florid, has a psychological

truth to it. He has after all, established an

odd, momentary union with the insect and

quite naturally—in terms of his attention

and frame of mind—doesn’t want to see the

creature pointlessly destroyed. An instant

later, the union is broken, and he walks

away, utterly unconcerned with its subse-

quent fate. (Eisner, however, stays with the

roach for a few panels, making a point

simply and well, before similarly abandon-

ing his own interest in the roach.)

You either respond to ‘ ‘A Life Force” or

you don’t: it is what it is. I found it full of

intricately wrought moments that gave me

pleasure.

The “Shop Talk”- in Will Eisner’s

Quarterly # I is with the artist Neal Adams.

It’s a good one. Eisner’s interviewing

method is an appealingly informal give-

and-take with his subject. And while

Adams has granted extensive interviews

elsewhere, Eisner isn’t terribly familiar

with his career. (Hearing mention of

Adams and Denny O’Neil’s Green

Lantern/Green Arrow series, Eisner, with

disarming innocence, says, “l, uh, never

read any of those, so… Adams is thus

placed in the position of being asked to

account for his own involvement with and

impact on comics, a task he manages with

clarity and a measure of humility. Eisner’s

Shop Talks never get too philosophical

and try to avoid controversy; the aim is to

have artists talk about the nuts-and-bolts

of their craft. The occasional problem with

this approach is accurately suggested by

Adams who, when asked to talk about his

working methods, responds with “‘Don’t

you find that sort of stuff… boring

(laughs)?” The Eisner-Adams meeting pr0-

duces an informative exchange, however,

and some genuinely illuminating samples

from Adams’s portfolio accompany the

text.

This is the sixty-seventh post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.