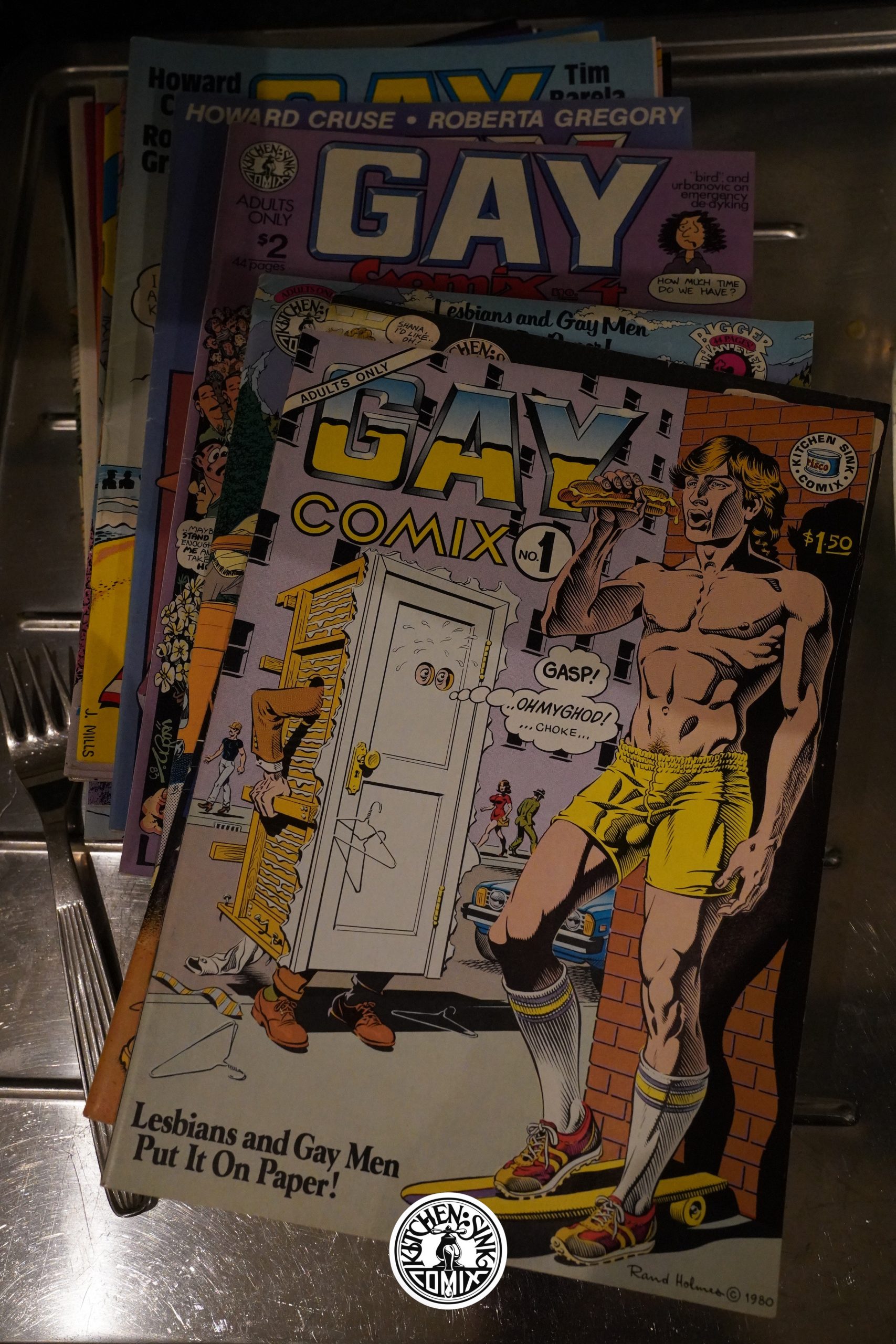

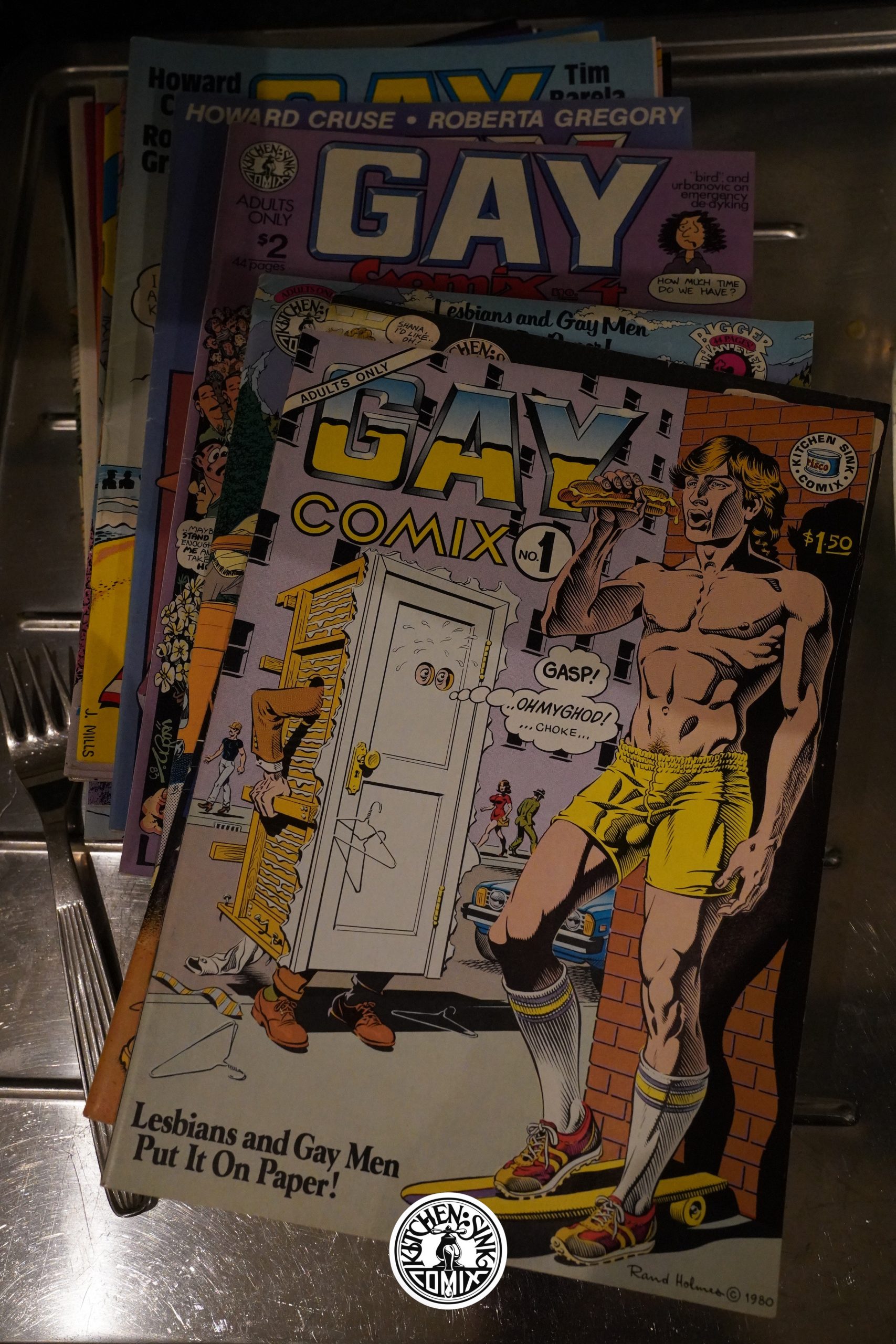

Gay Comix (1980) #1-5, #6-14, #15-25, Special edited by Howard Cruse, Robert Triptow and then Andy Mangels

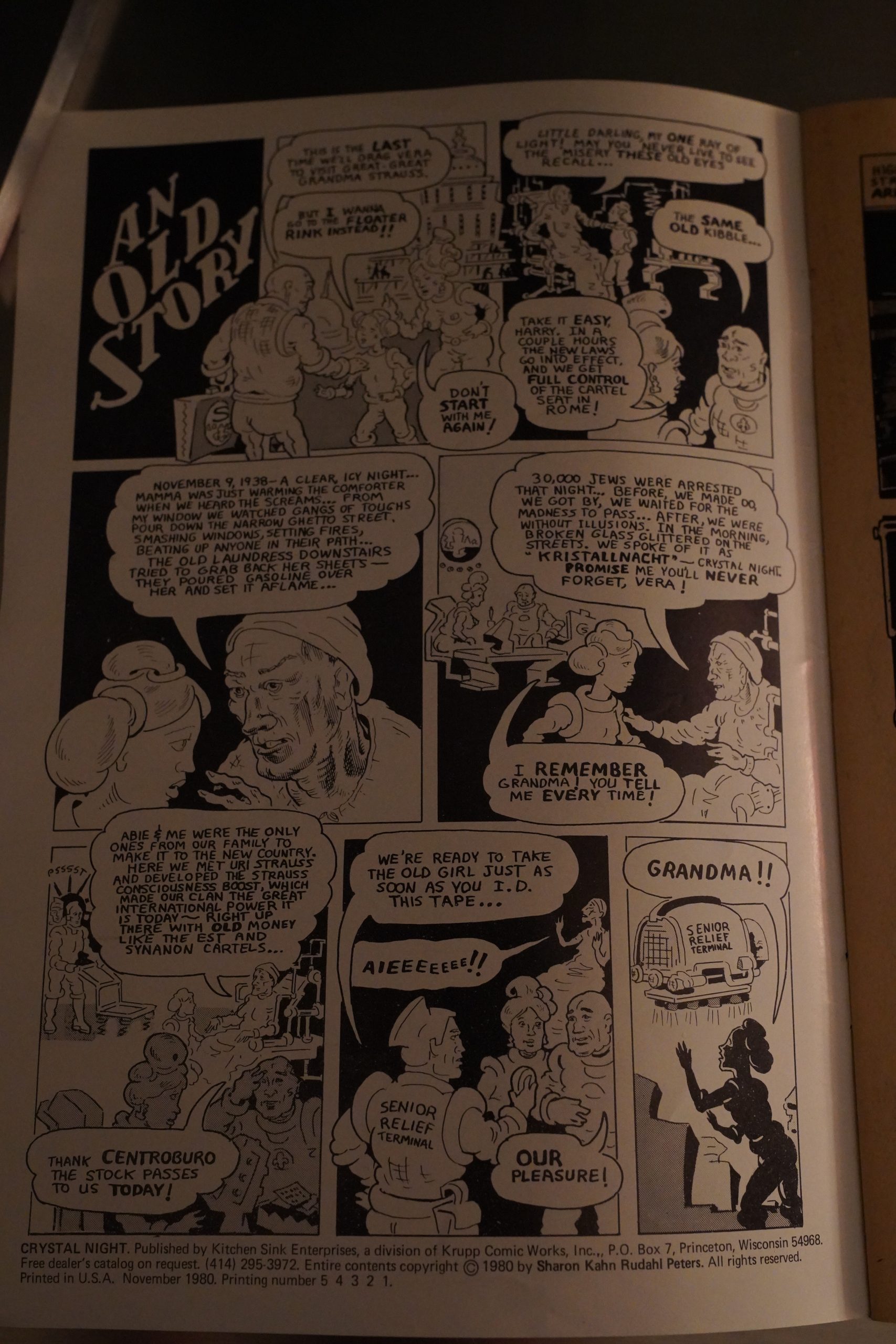

Gay Comix is a significant anthology in many ways, of course, but in the Kitchen Sink story, it’s also significant because it’s the final underground anthology Kitchen Sink would publish.

Now, one can argue about what an “underground” comic is, but Kitchen Sink’s publishing output was definitely mostly underground comics in the beginning, and then they started segueing into being an alternative comics publisher (distributed via comics speciality stores instead of head shops and mail order). This wasn’t just a change in distribution, but also a change in aesthetics.

Gay Comix started off solidly as an underground anthology, featuring well-known underground cartoonists, and that stopped being a thing Kitchen did in the early 80s, and Kitchen dropped Gay Comix after publishing five issues — but by that time, Gay Comix didn’t really fit into Kitchen’s publishing slate much.

I had planned to only cover the five Kitchen issues in this blog — but rooting through my boxes of comics, I was flabbergasted to find that there’s 25 issues of this thing (and one special). I mean, I’ve apparently been buying these things over the years, but if you’d asked me how many of them I thought there were, I’d have said… ten?

So now I’m kind of intrigued, and I’m gonna read them all and natter on about them, I guess. I’m writing this before I started on the first issue, so perhaps I’ll chicken out or something, but if not: Get ready to scroll. A lot.

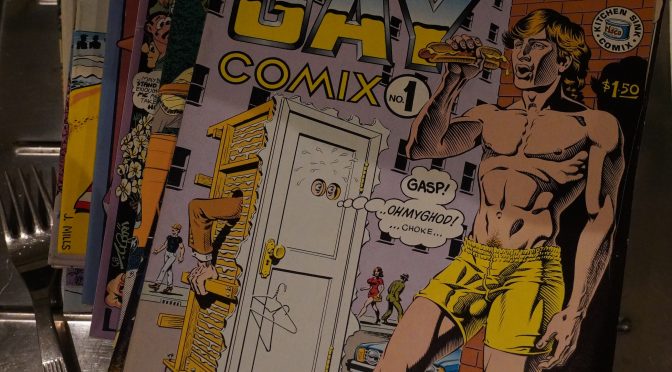

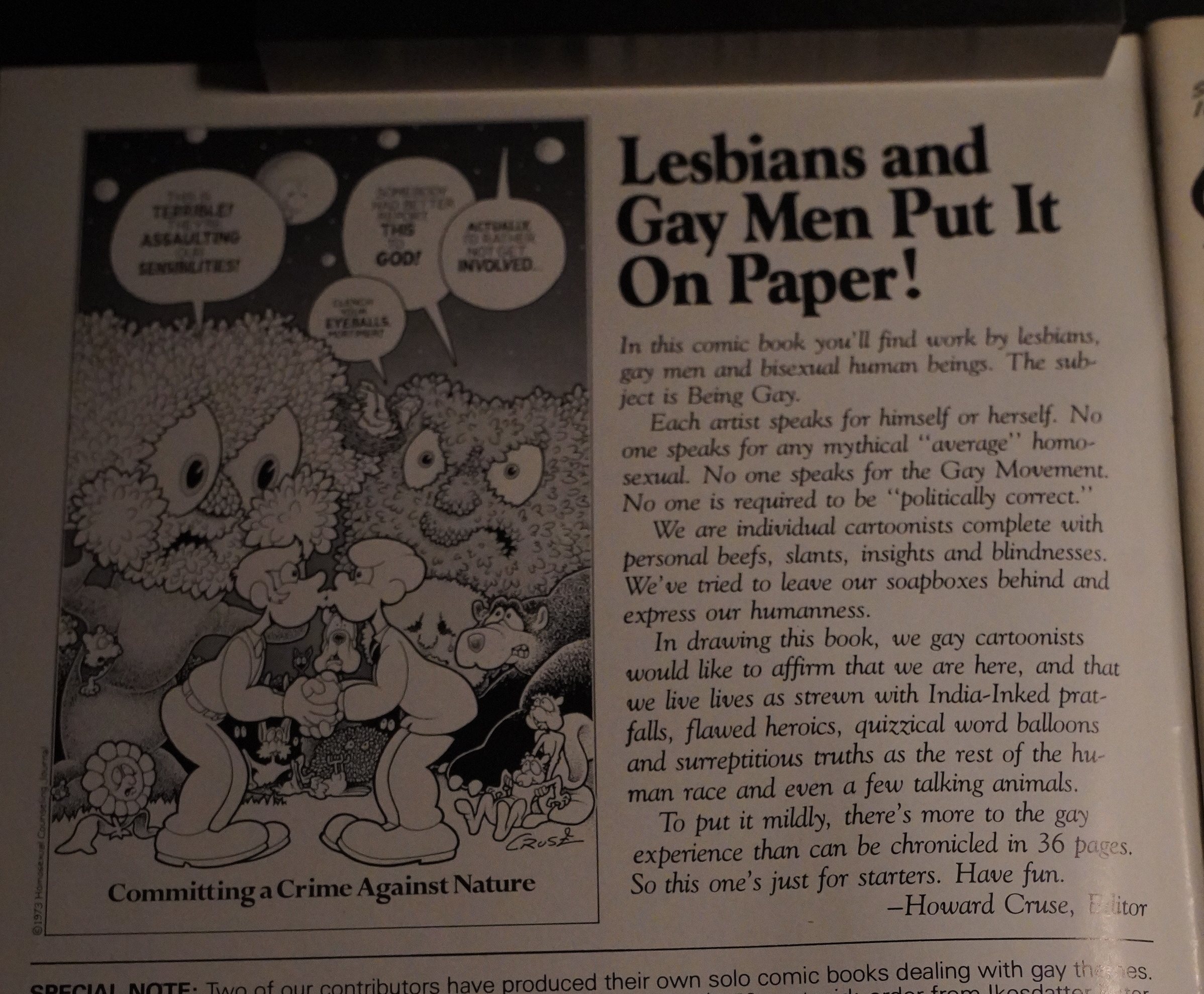

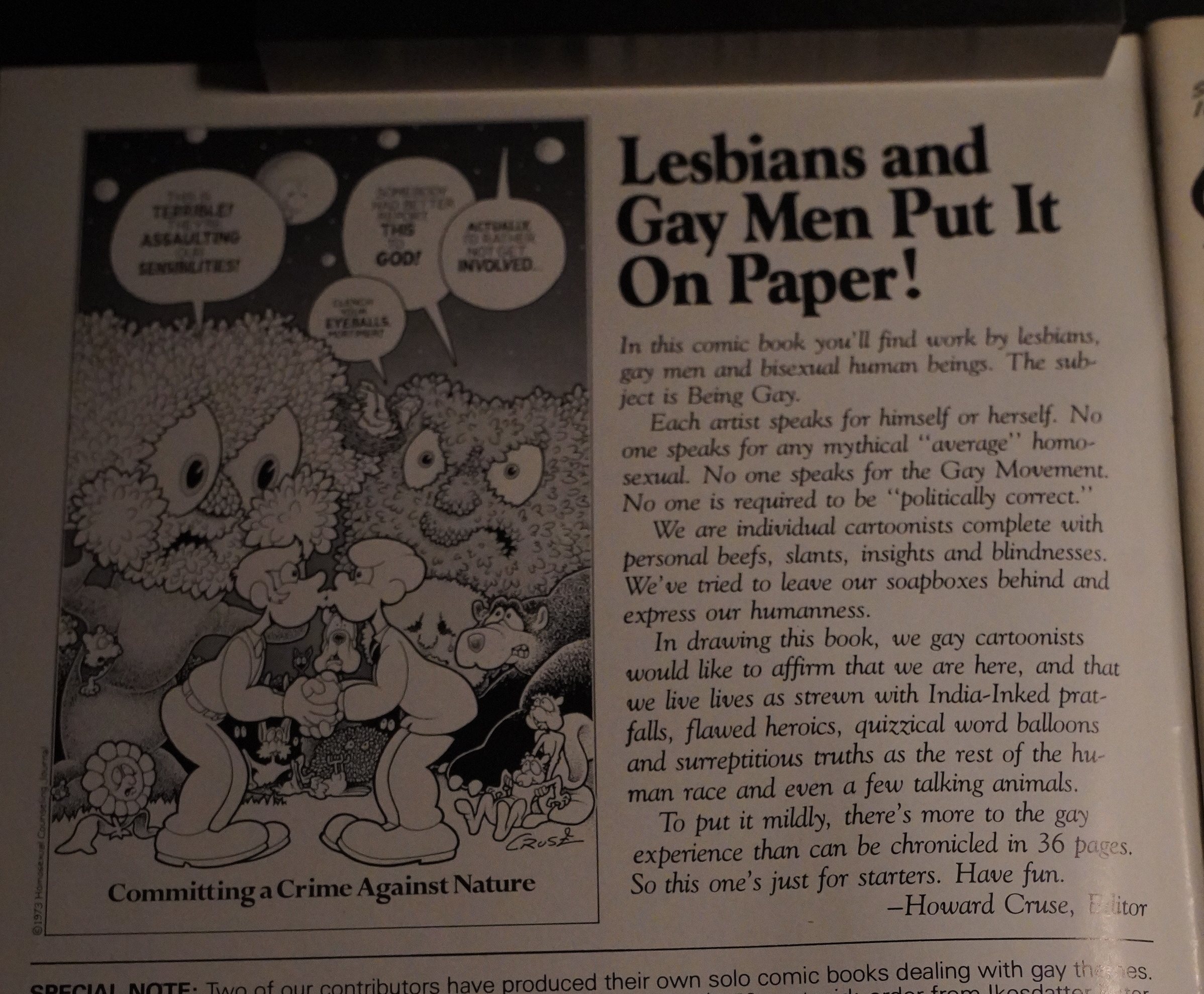

Editor Howard Cruse sets out the parameters for the series: It’s work by lesbians, gay men and bisexuals, and the subject is “Being Gay”.

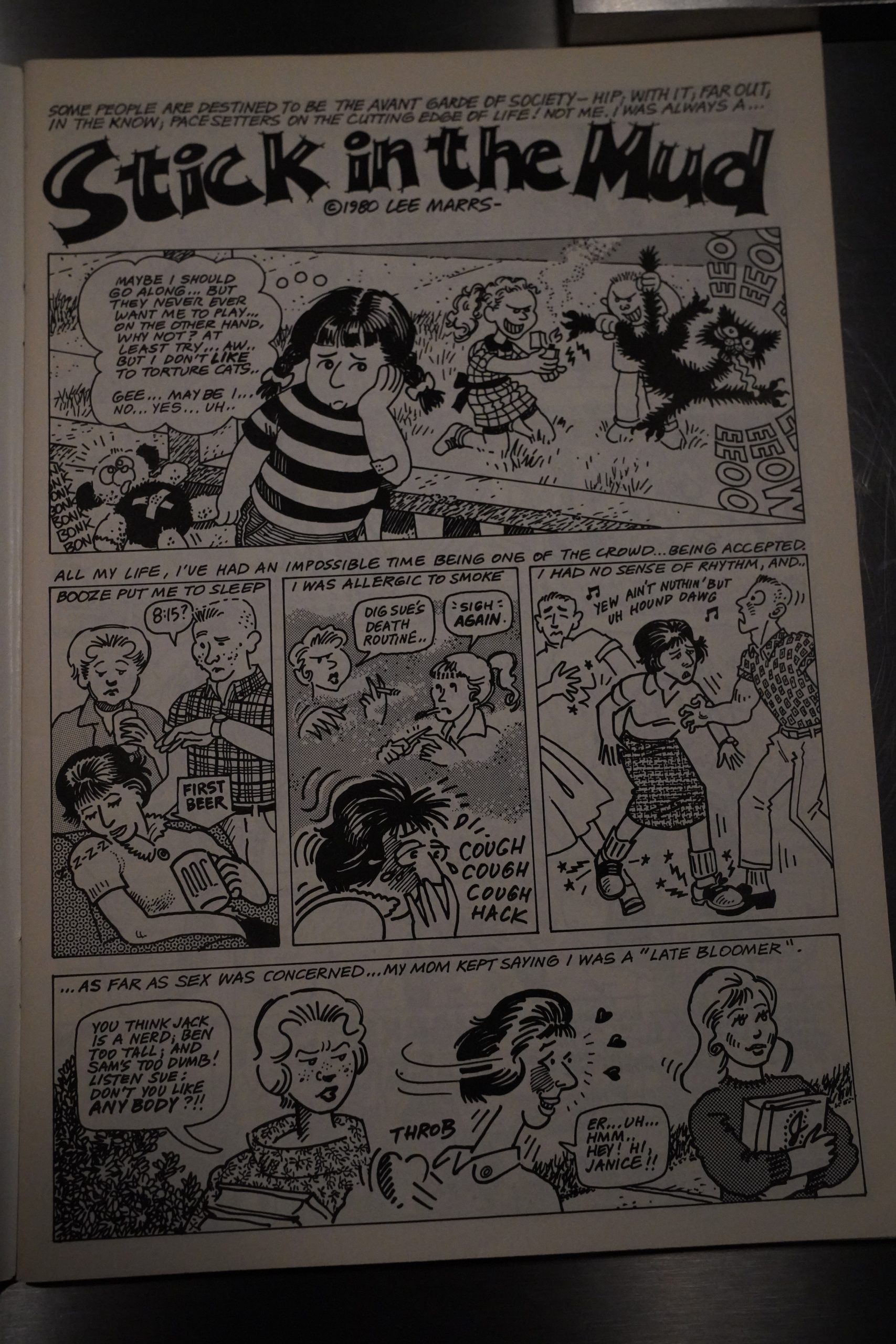

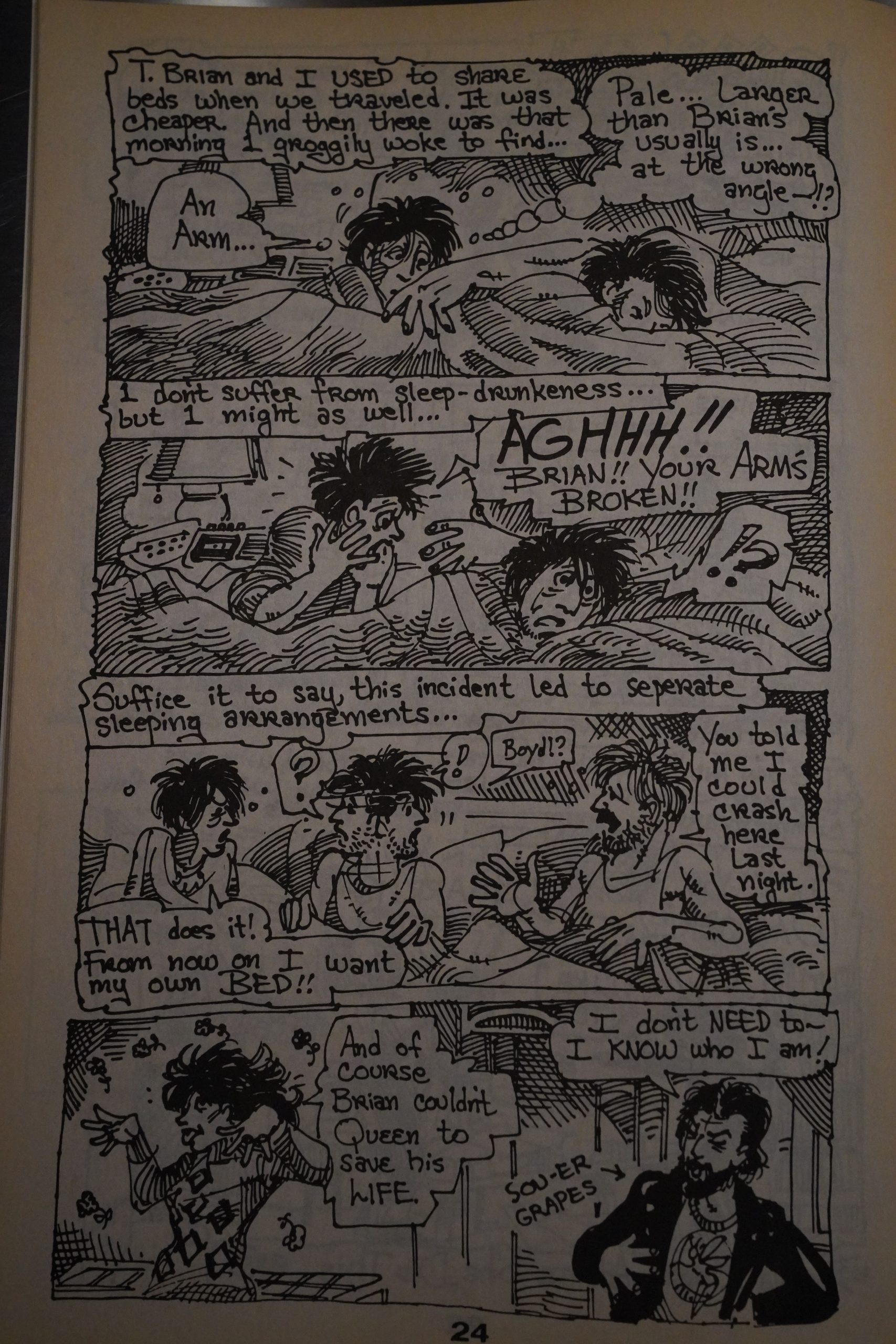

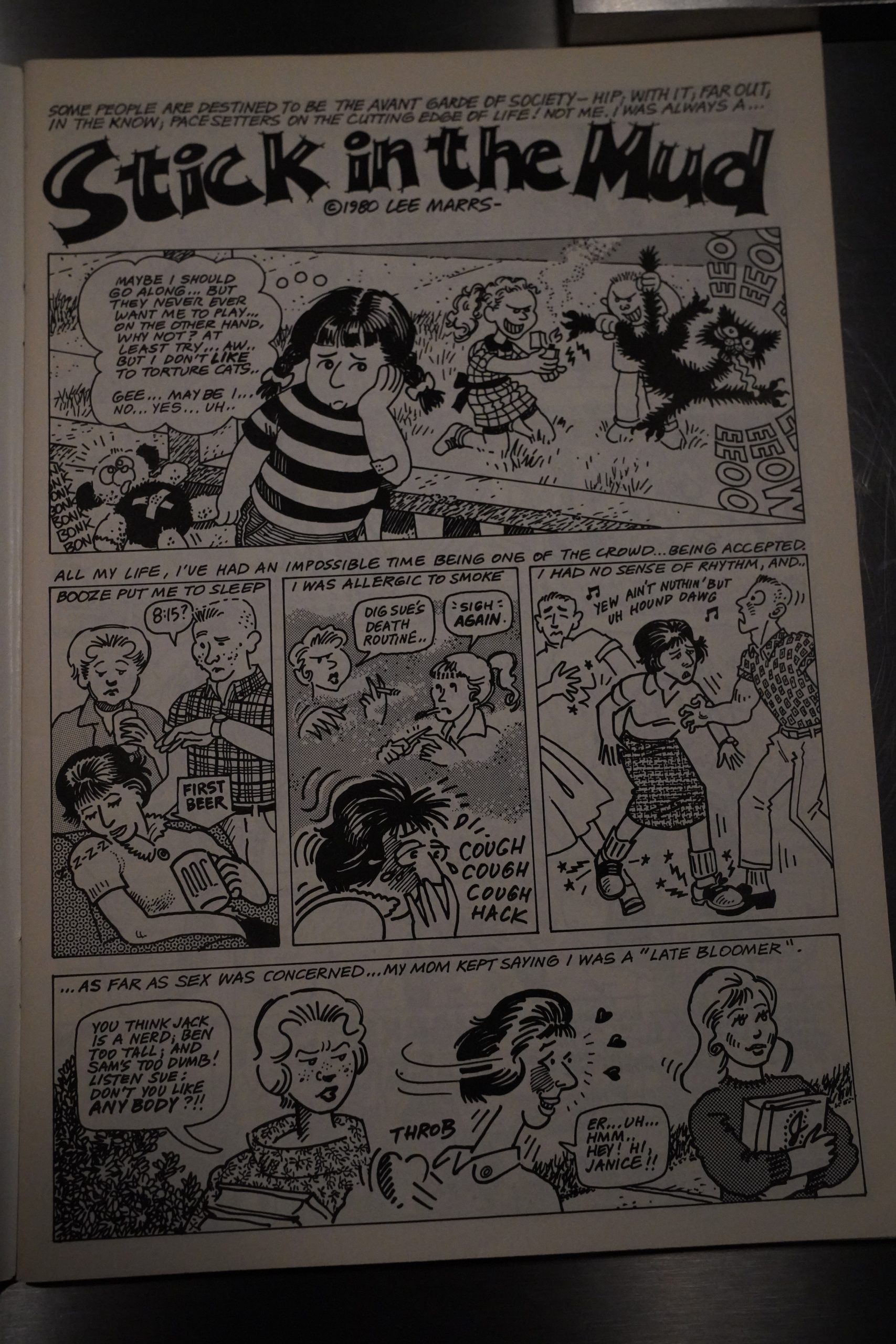

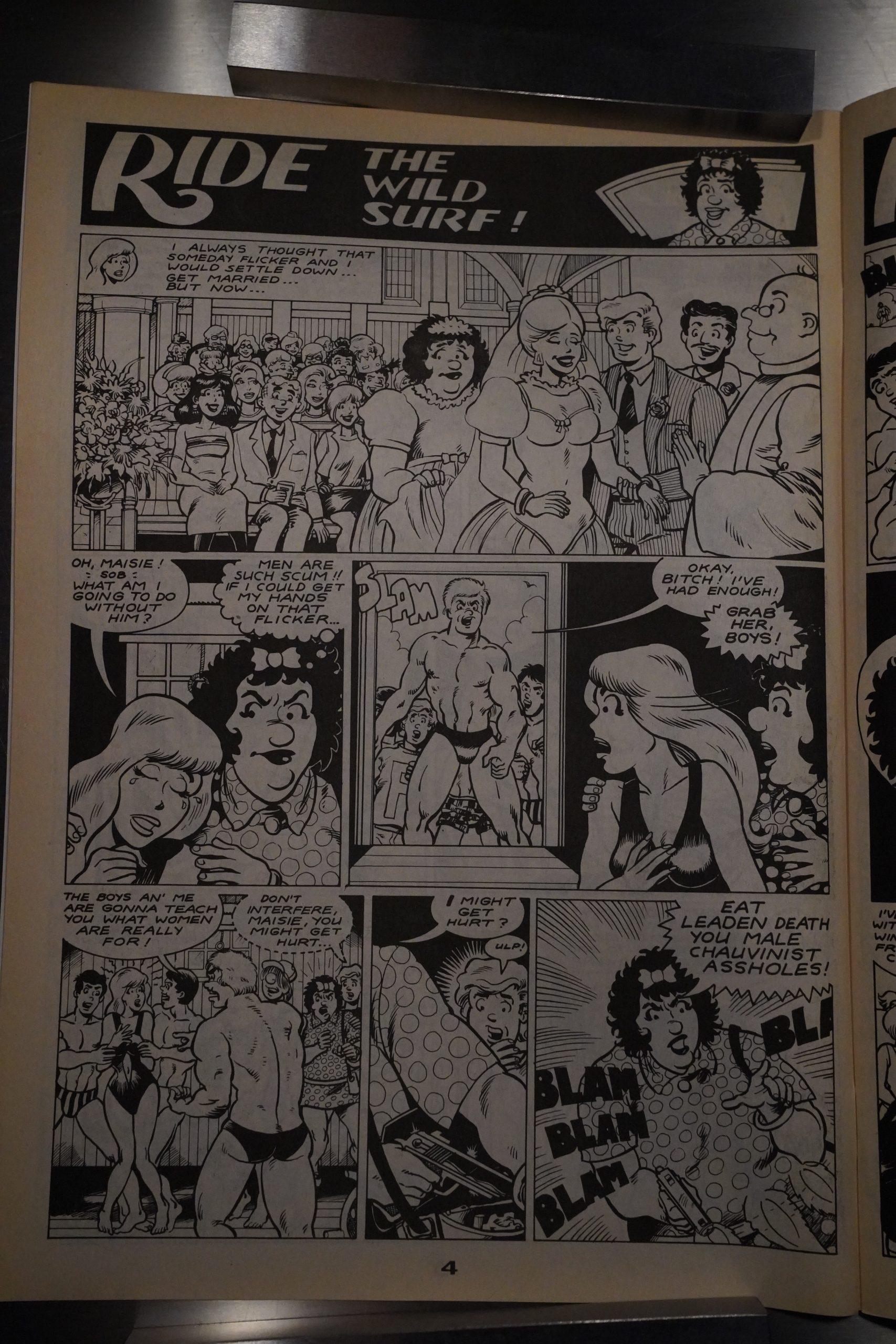

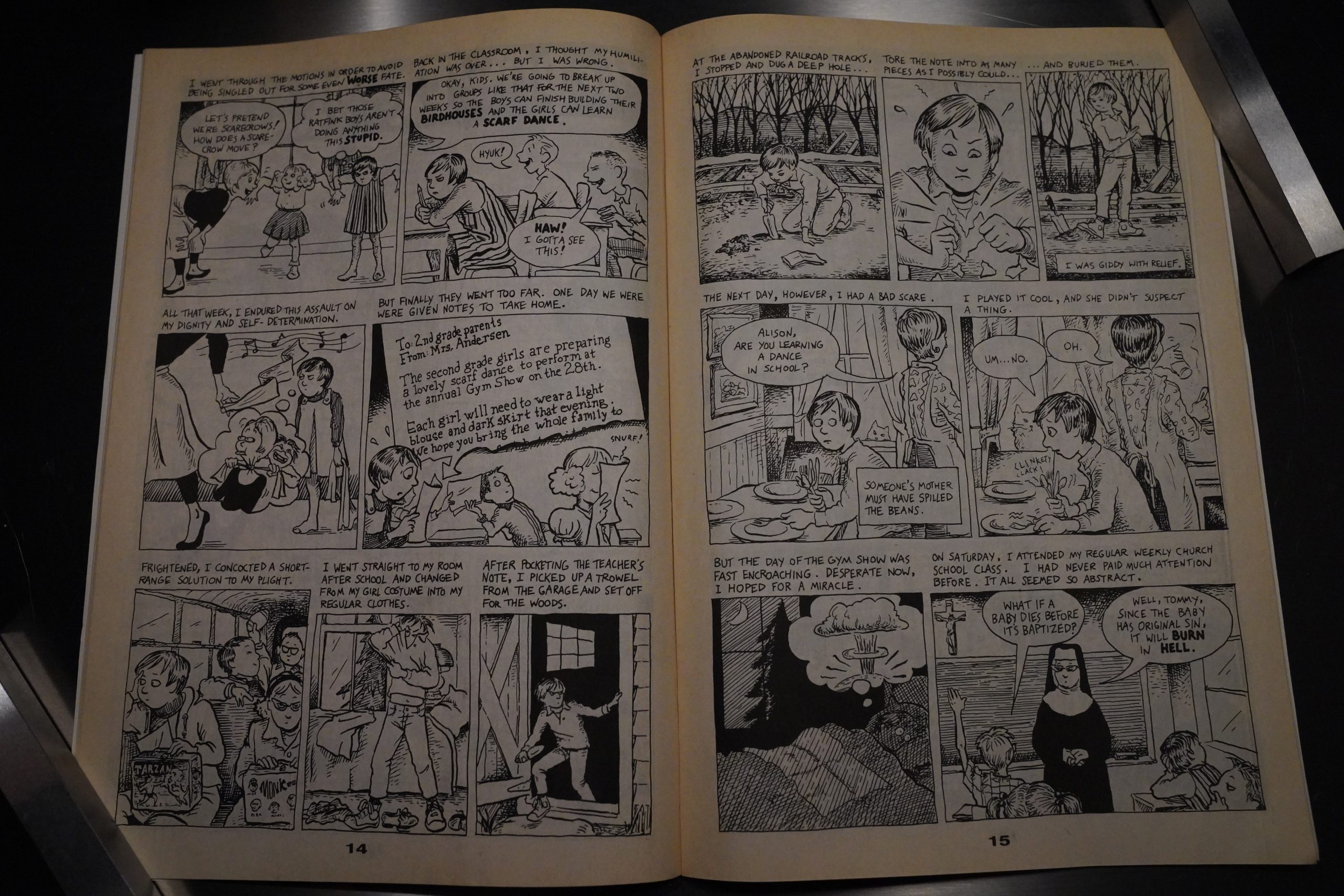

The first issue is dominated by people that had (mostly) all appeared in Kitchen publications before. So here’s Lee Marrs doing a funny (apparent) auto-bio about growing up lesbian and awkward.

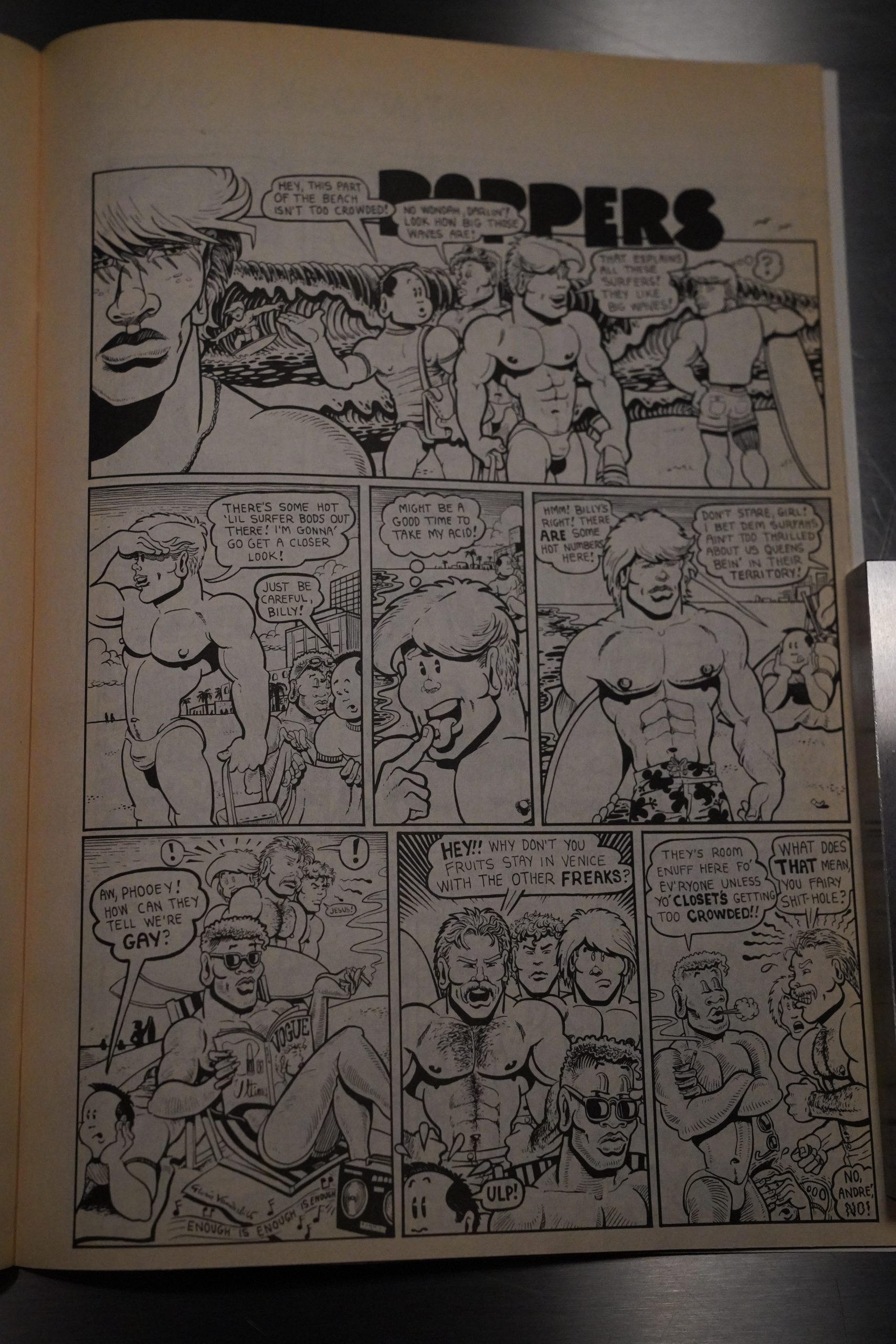

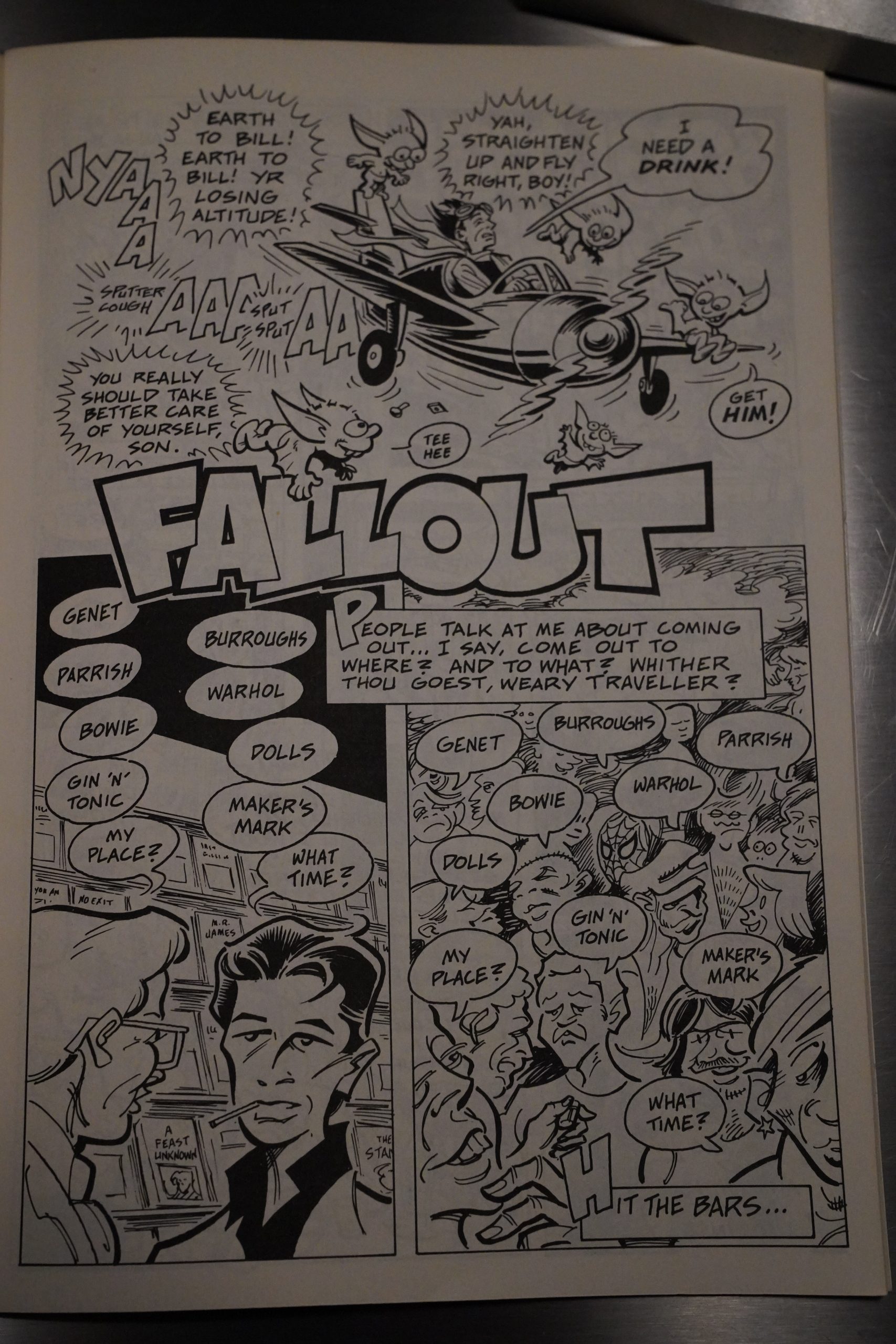

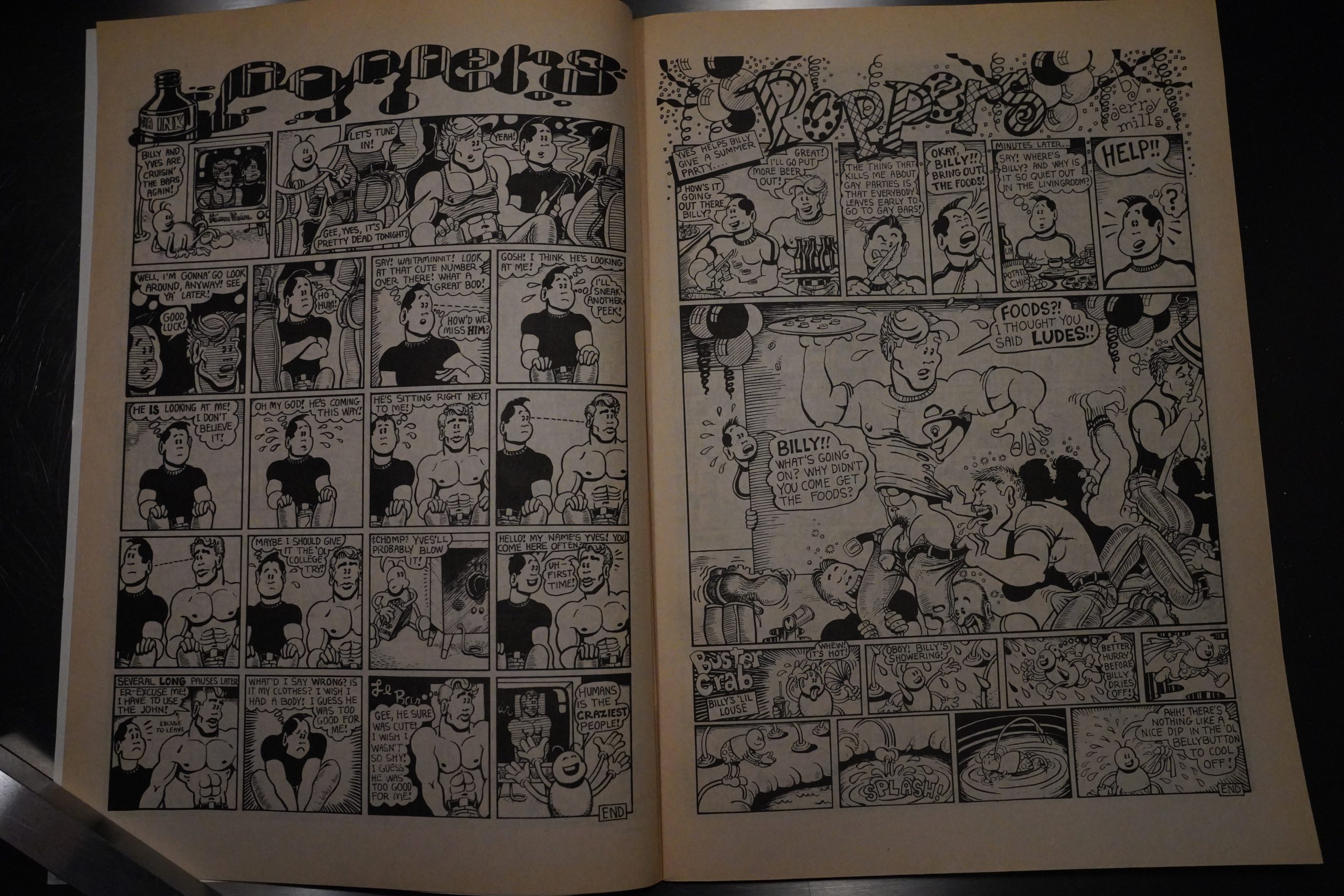

Billy Fugate is a newcomer, though. (I think.)

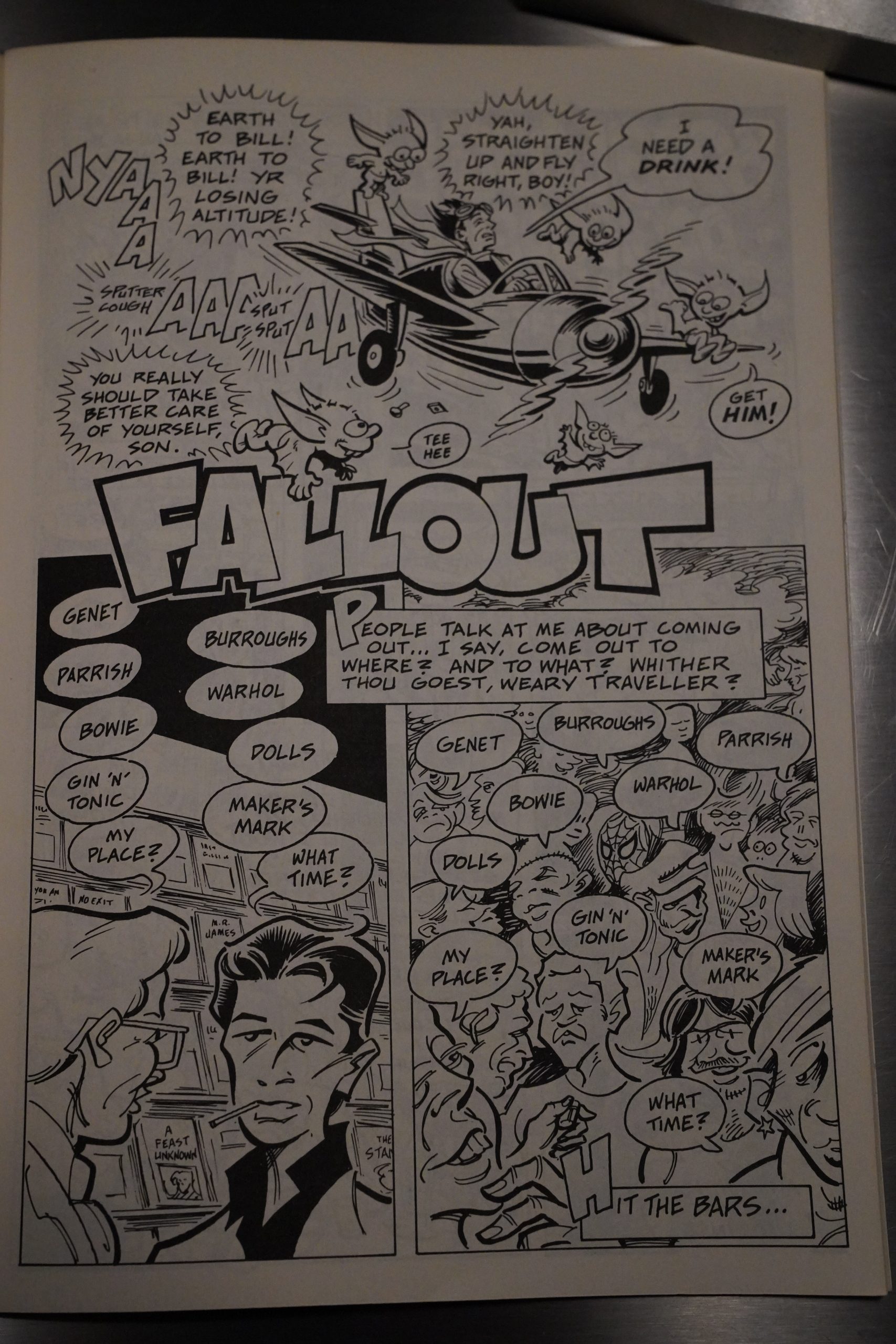

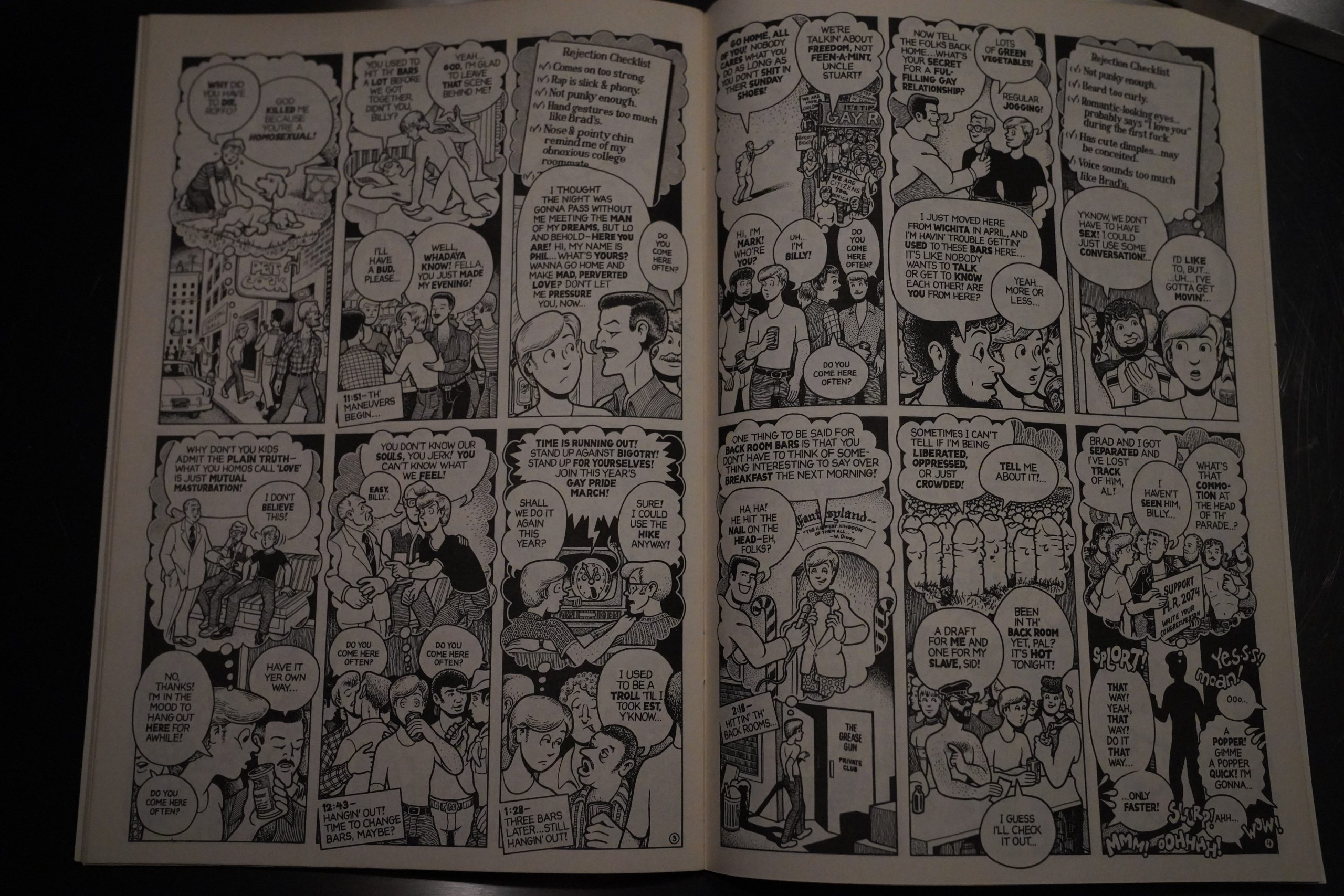

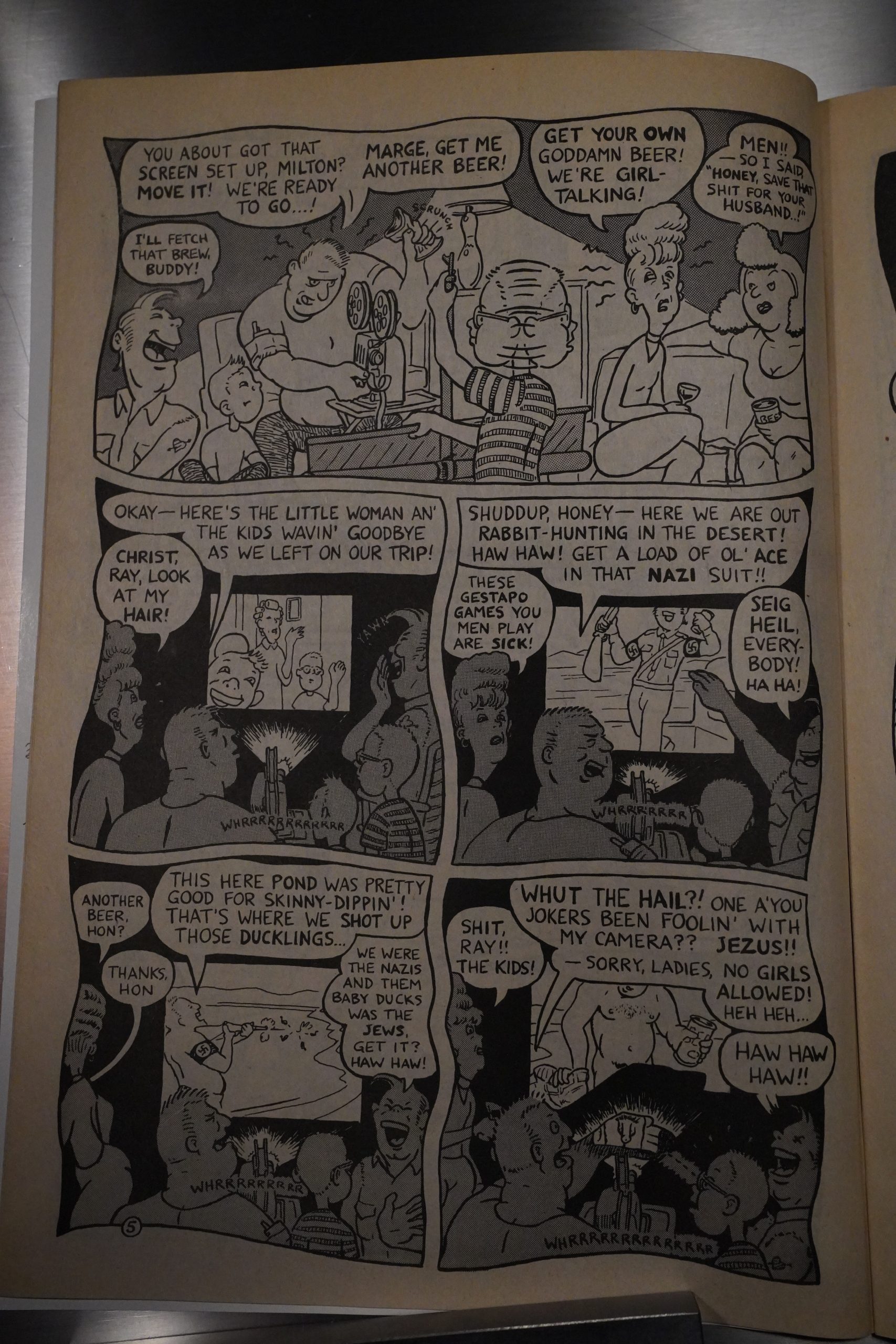

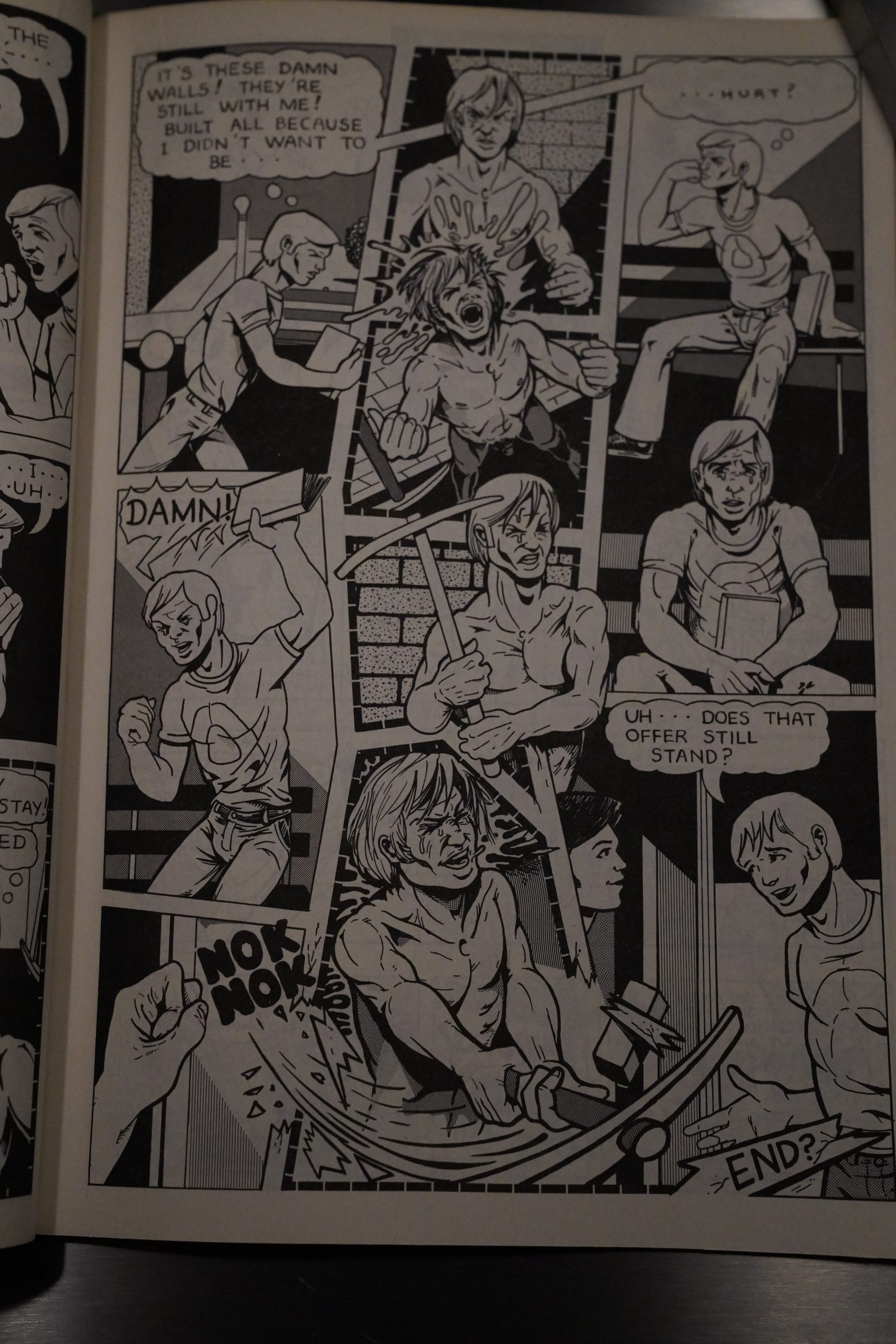

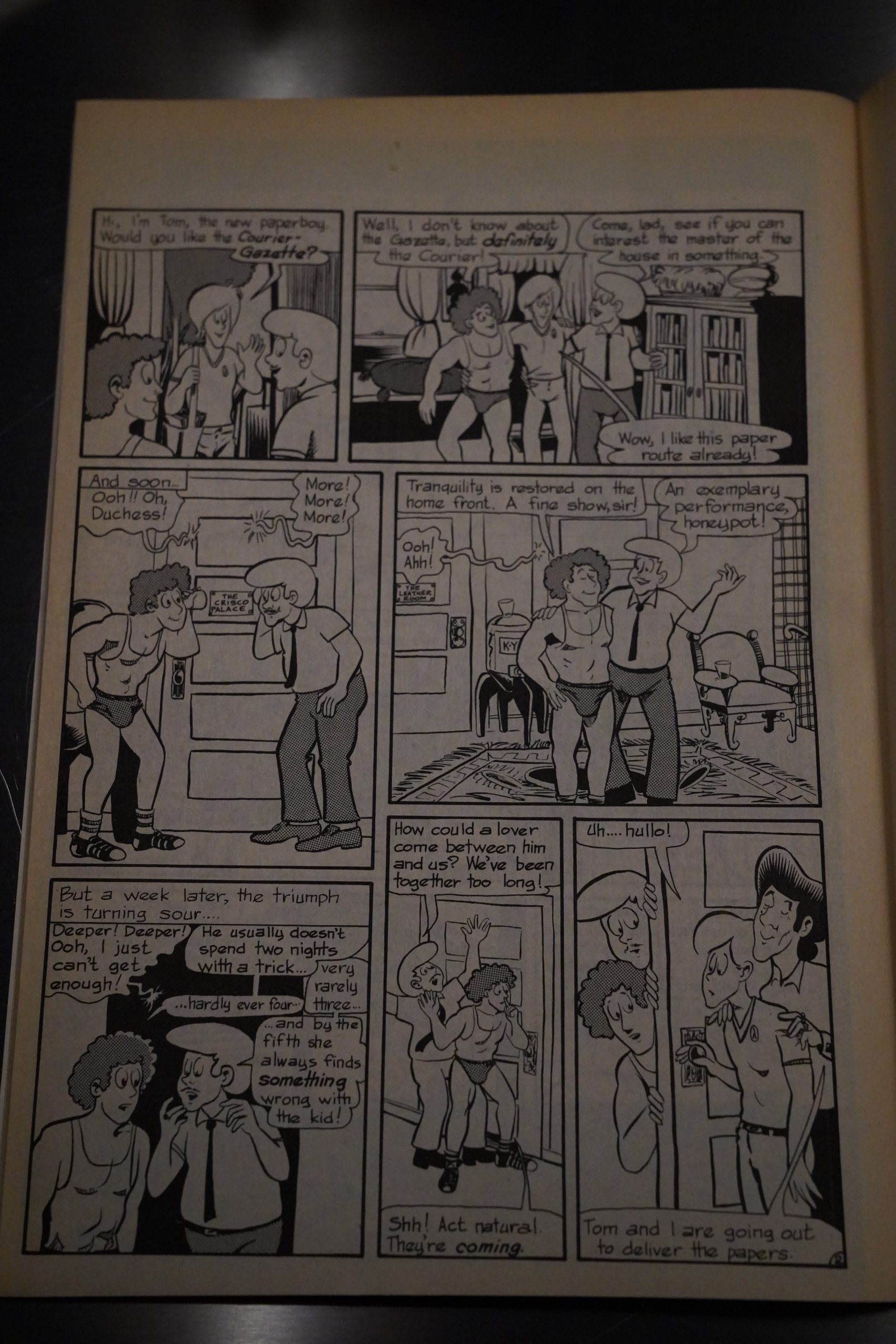

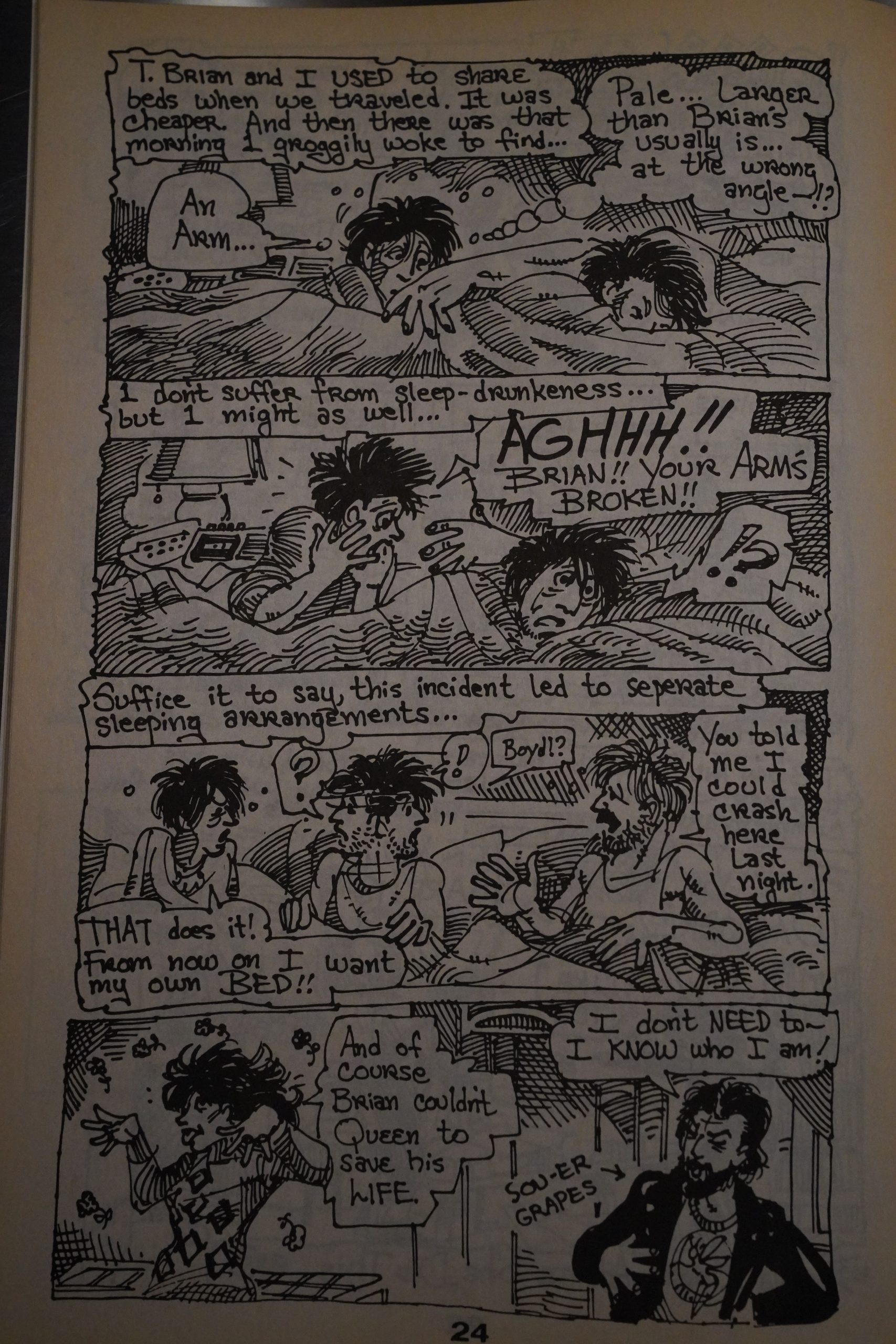

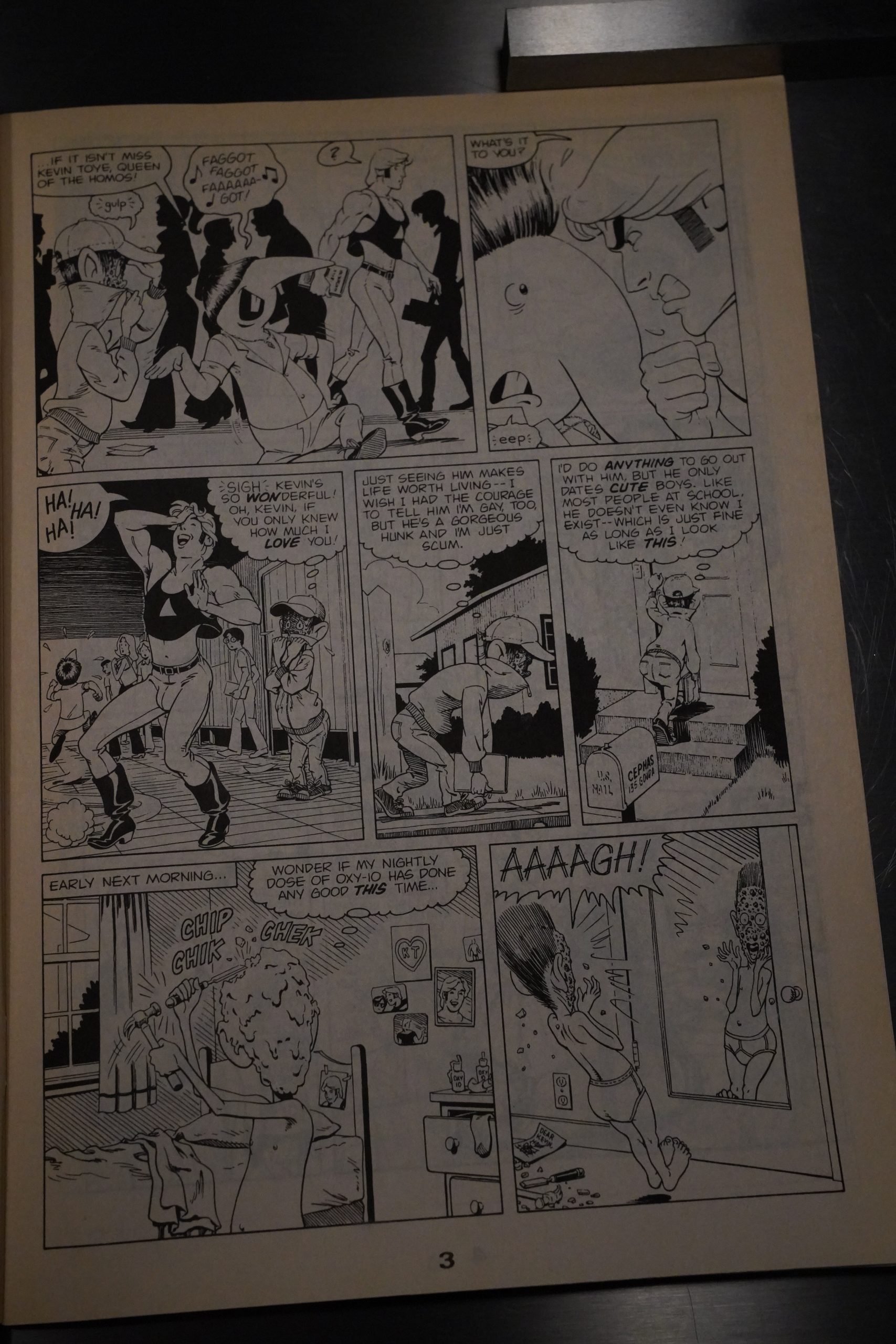

The first couple of issues of Gay Comix are dominated by two themes: Coming out and going out to bars. (Fugate covers the latter theme.)

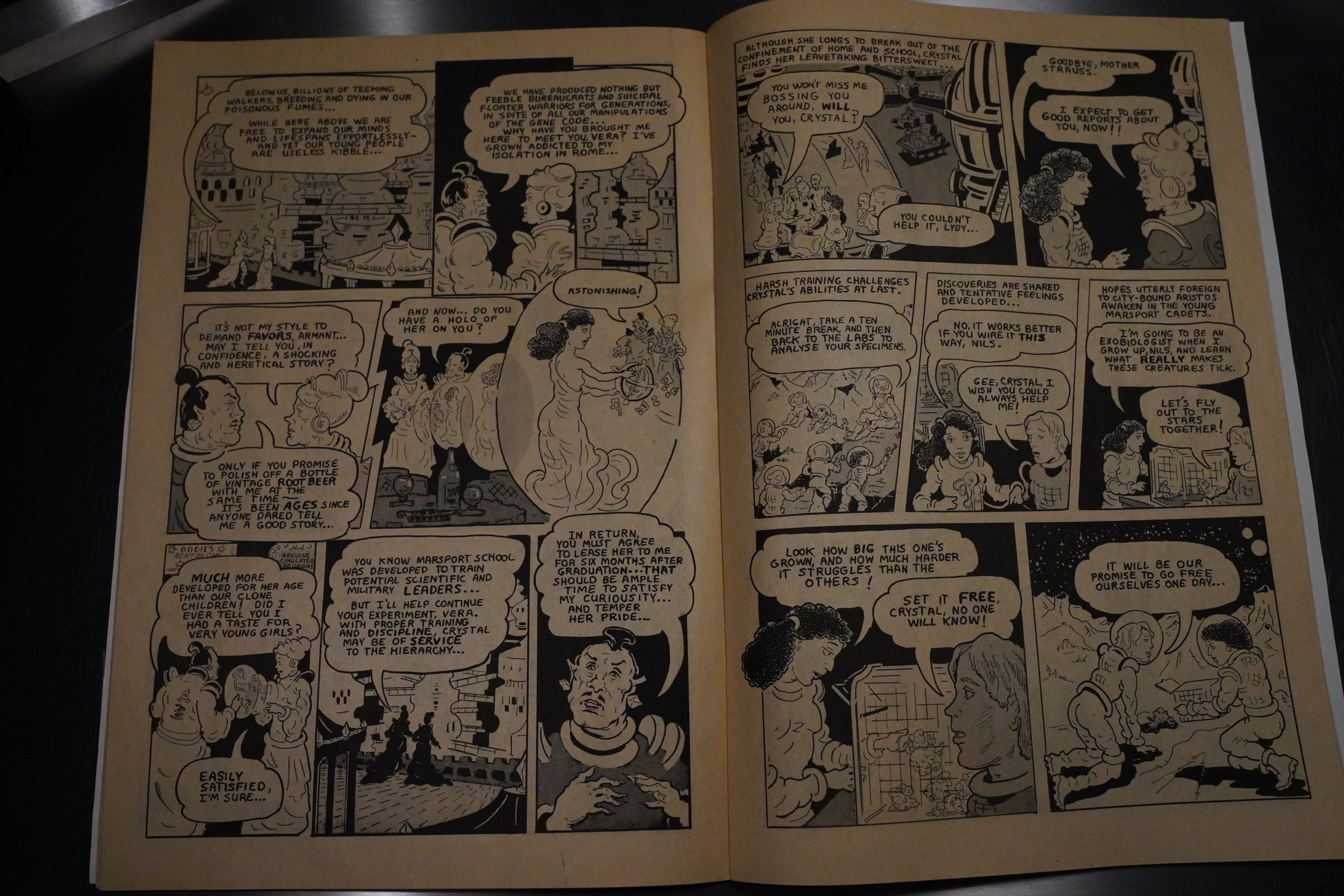

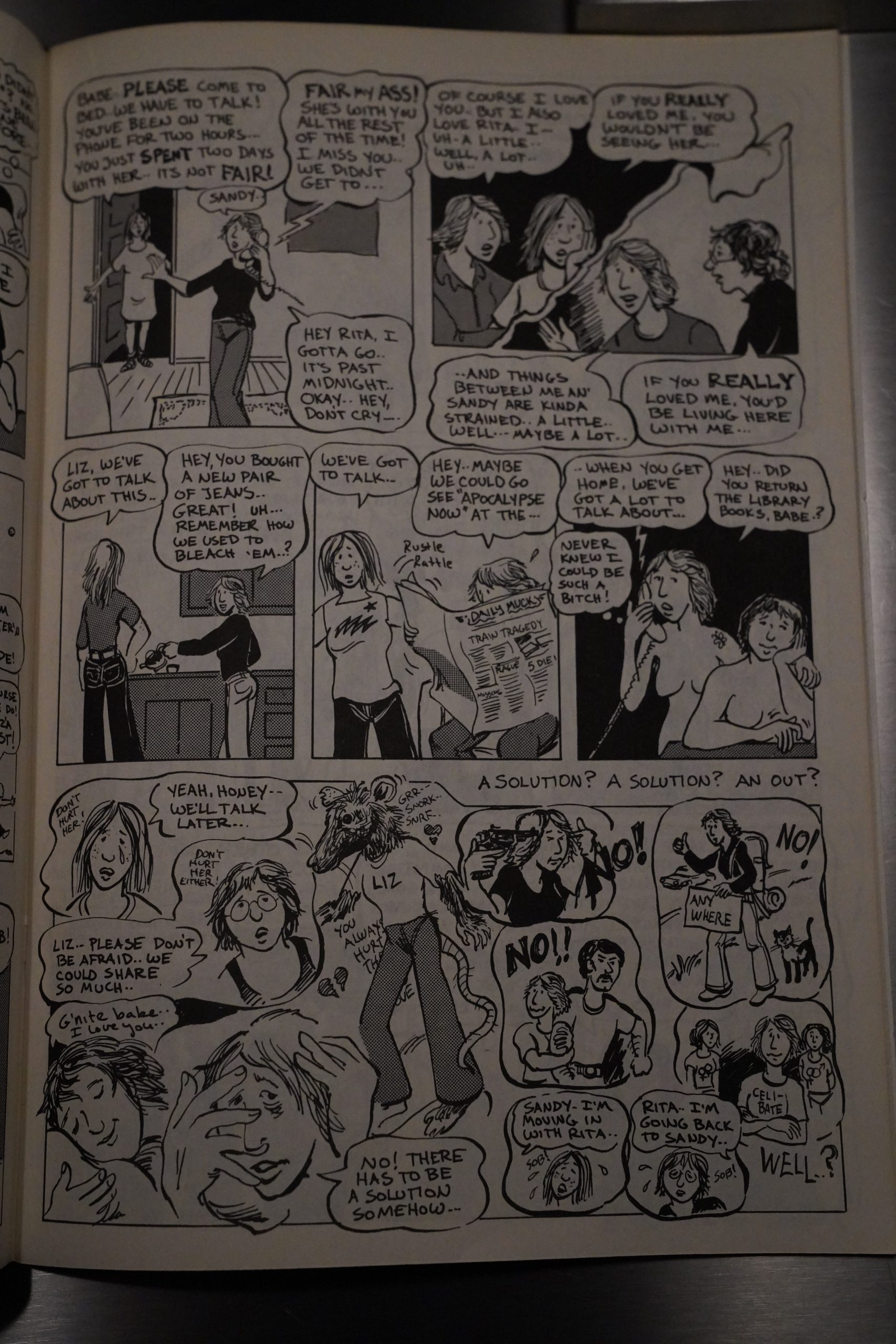

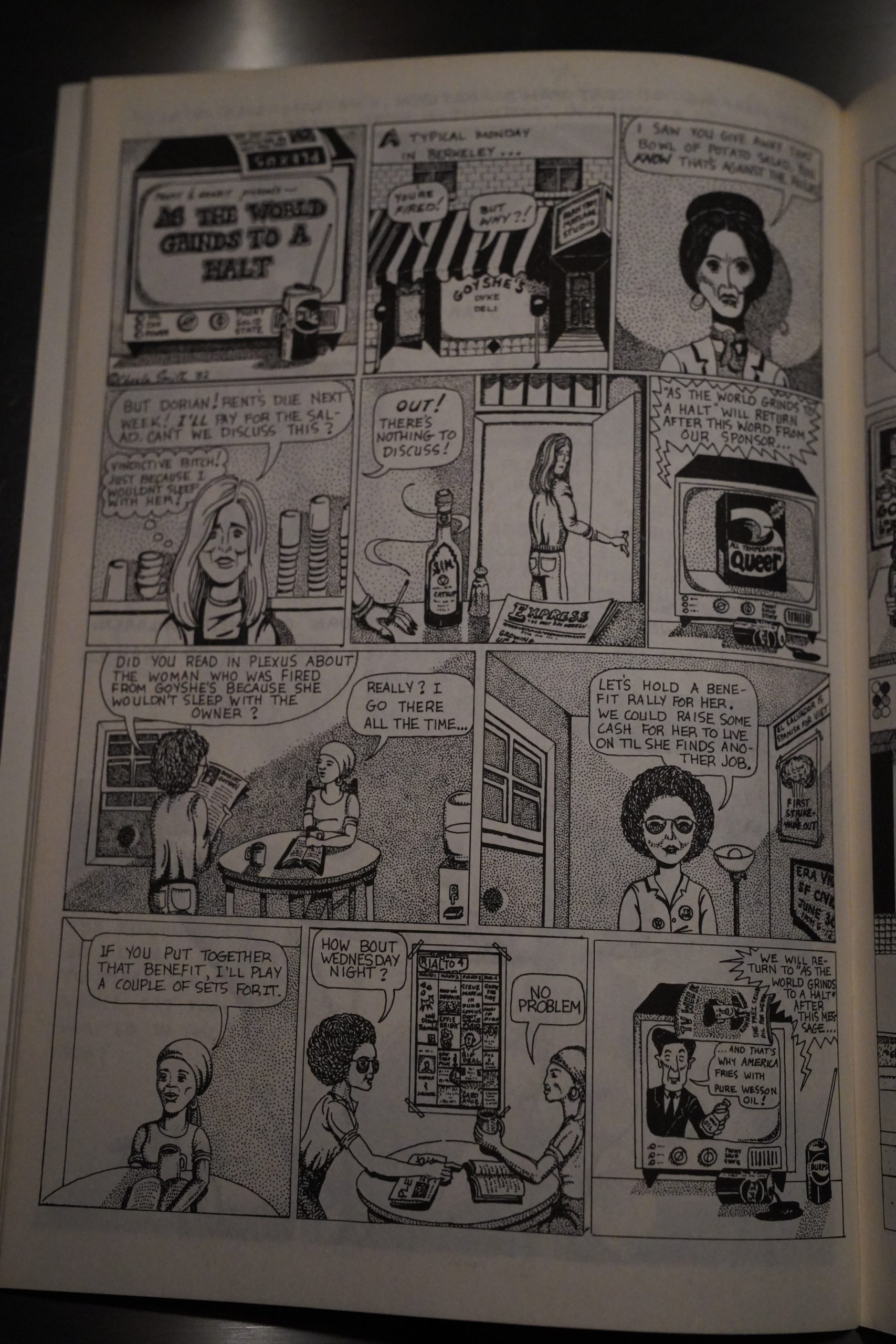

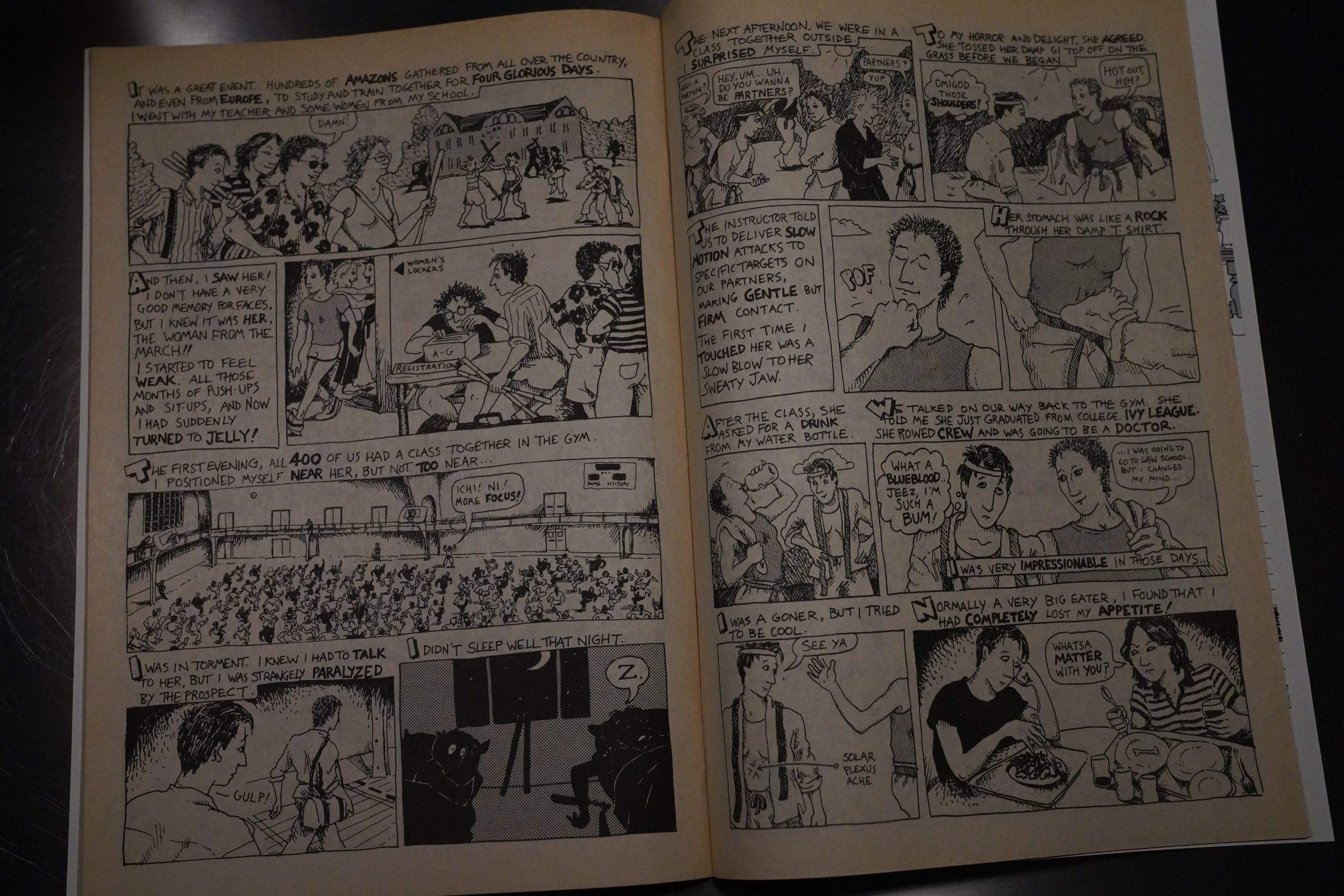

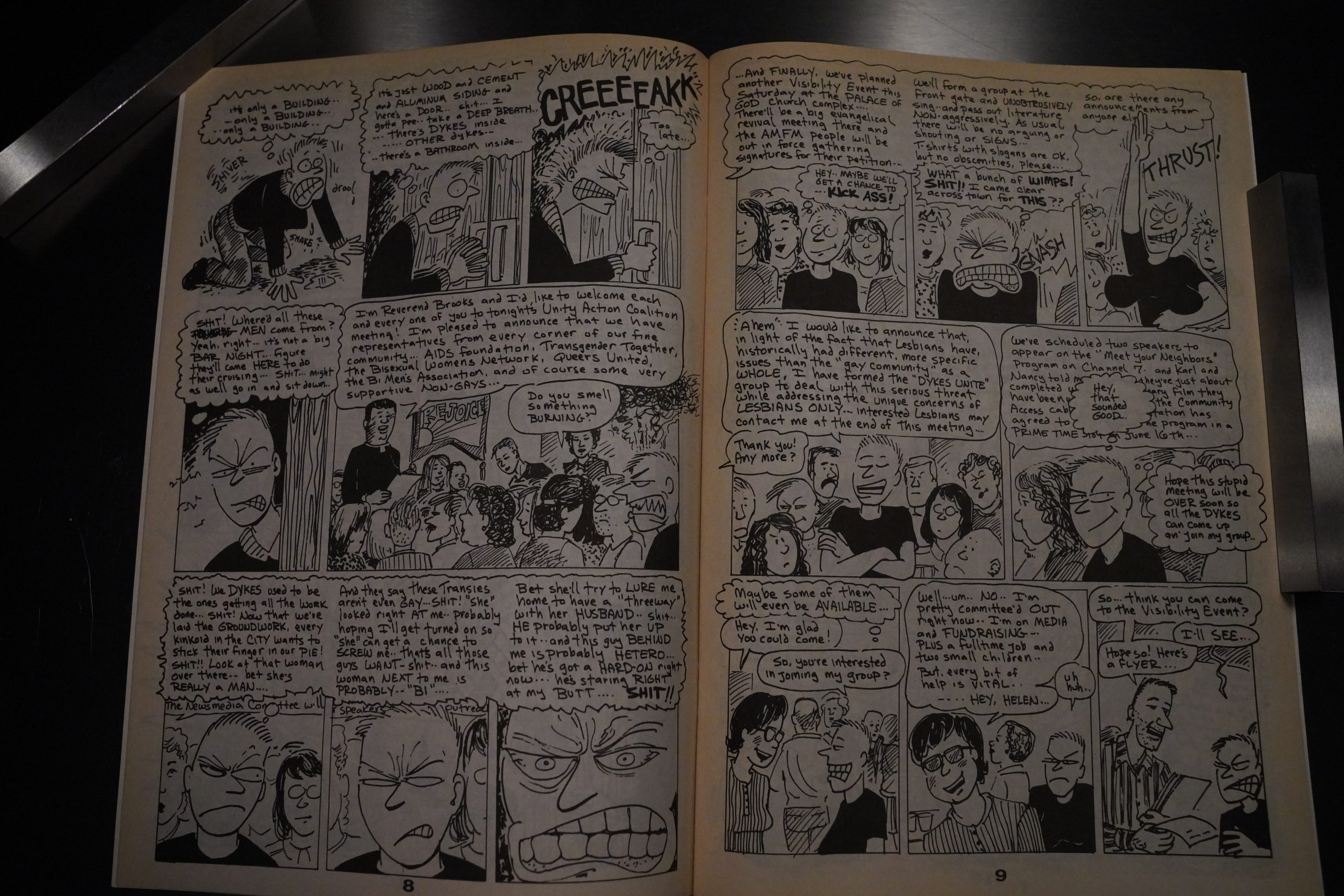

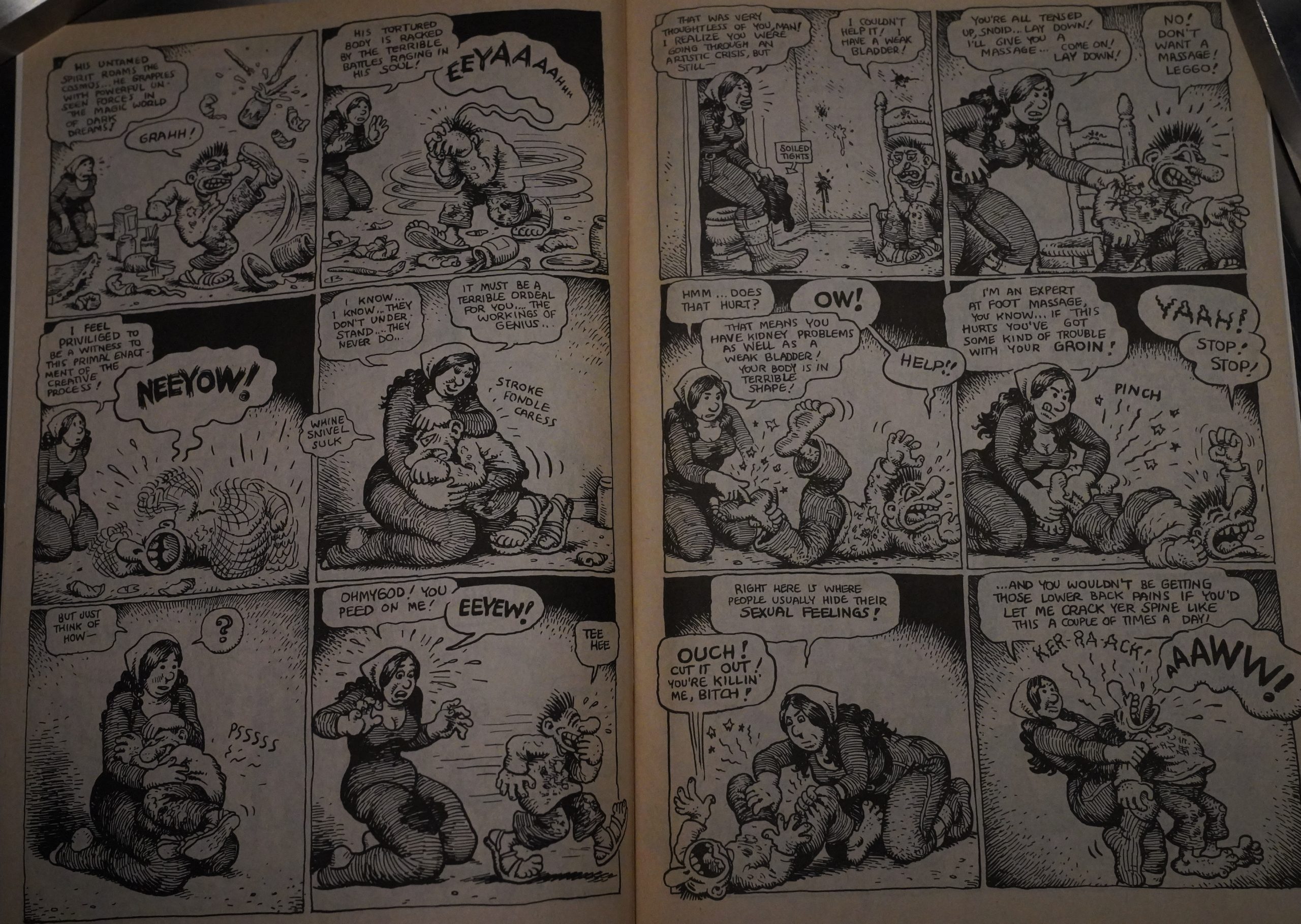

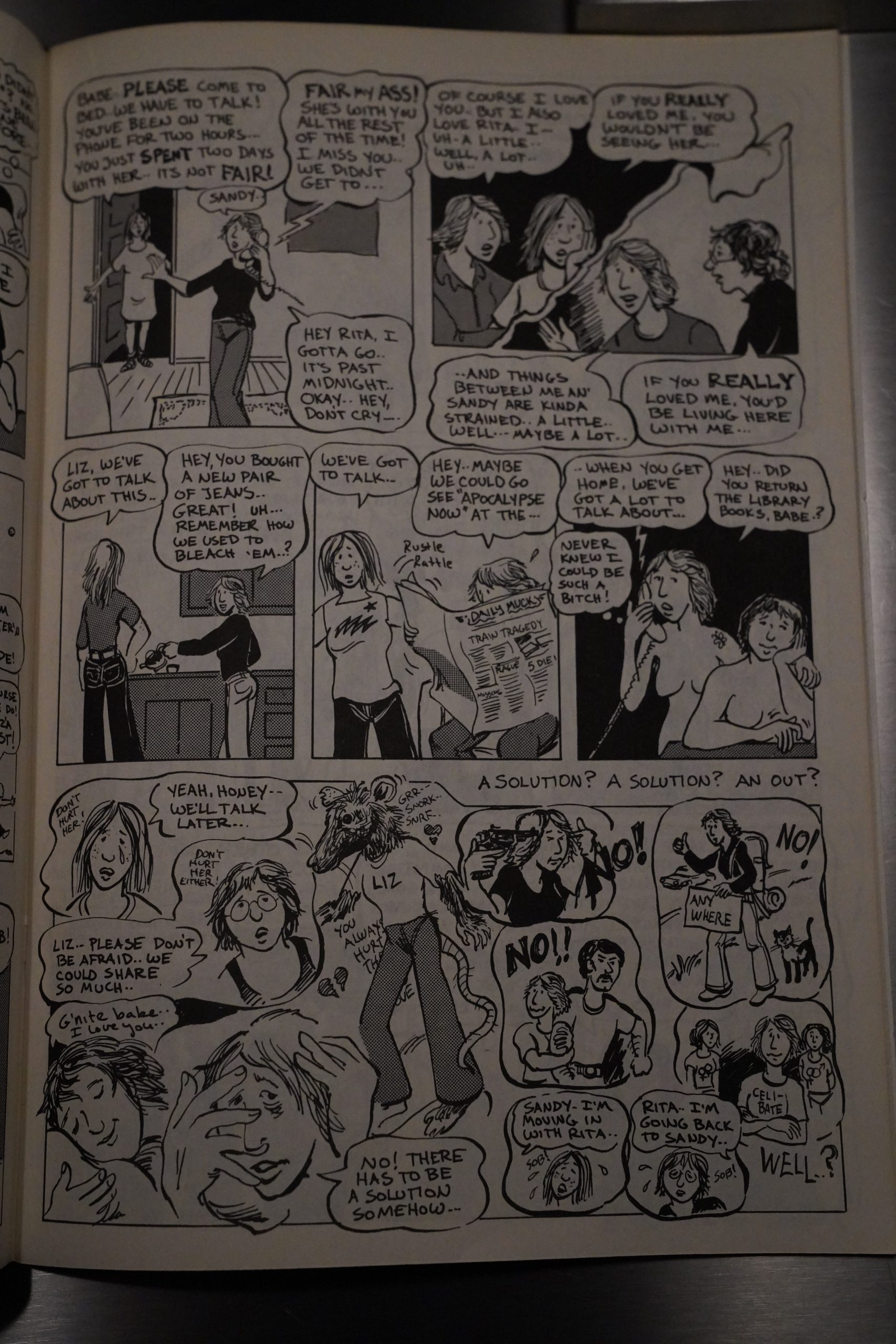

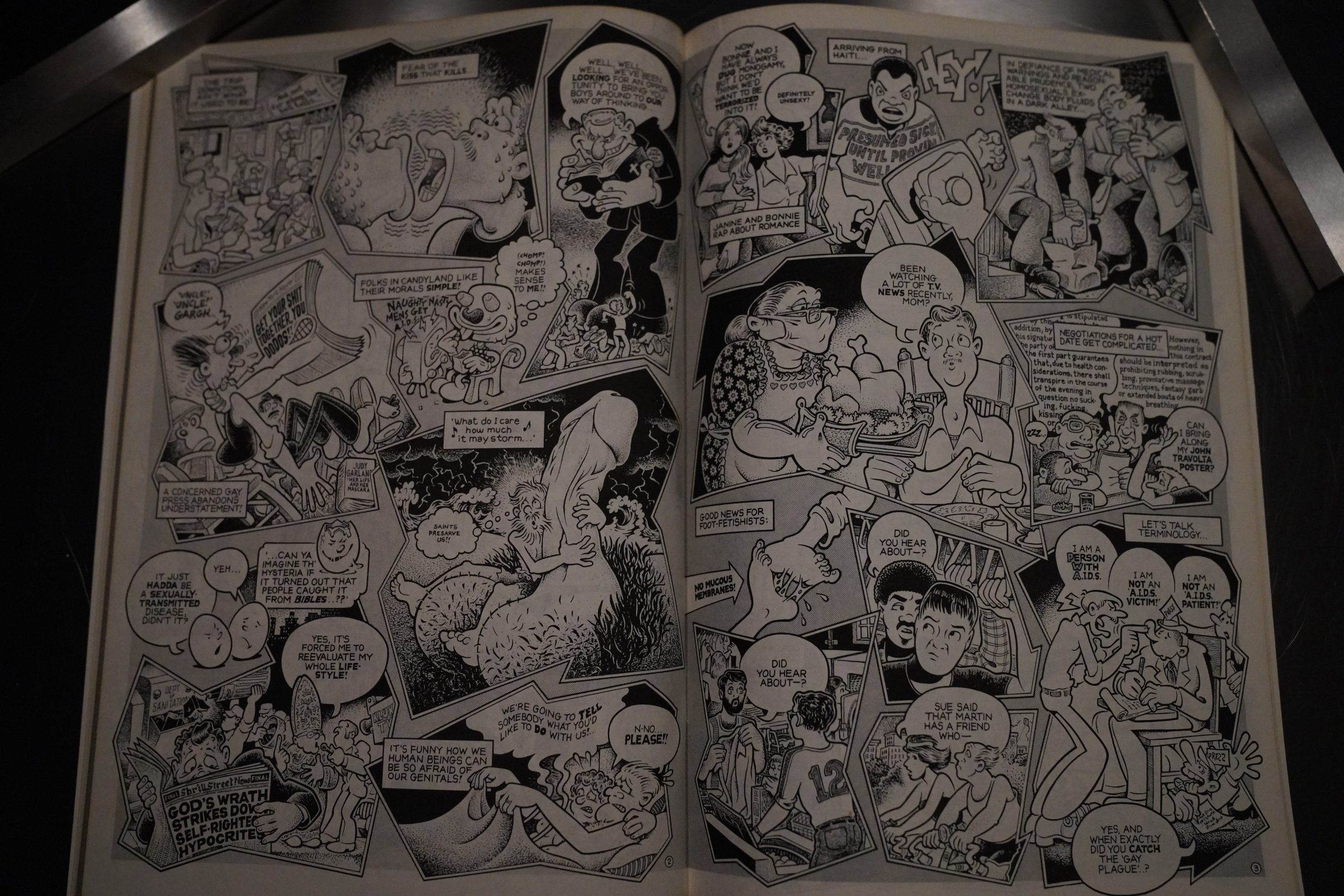

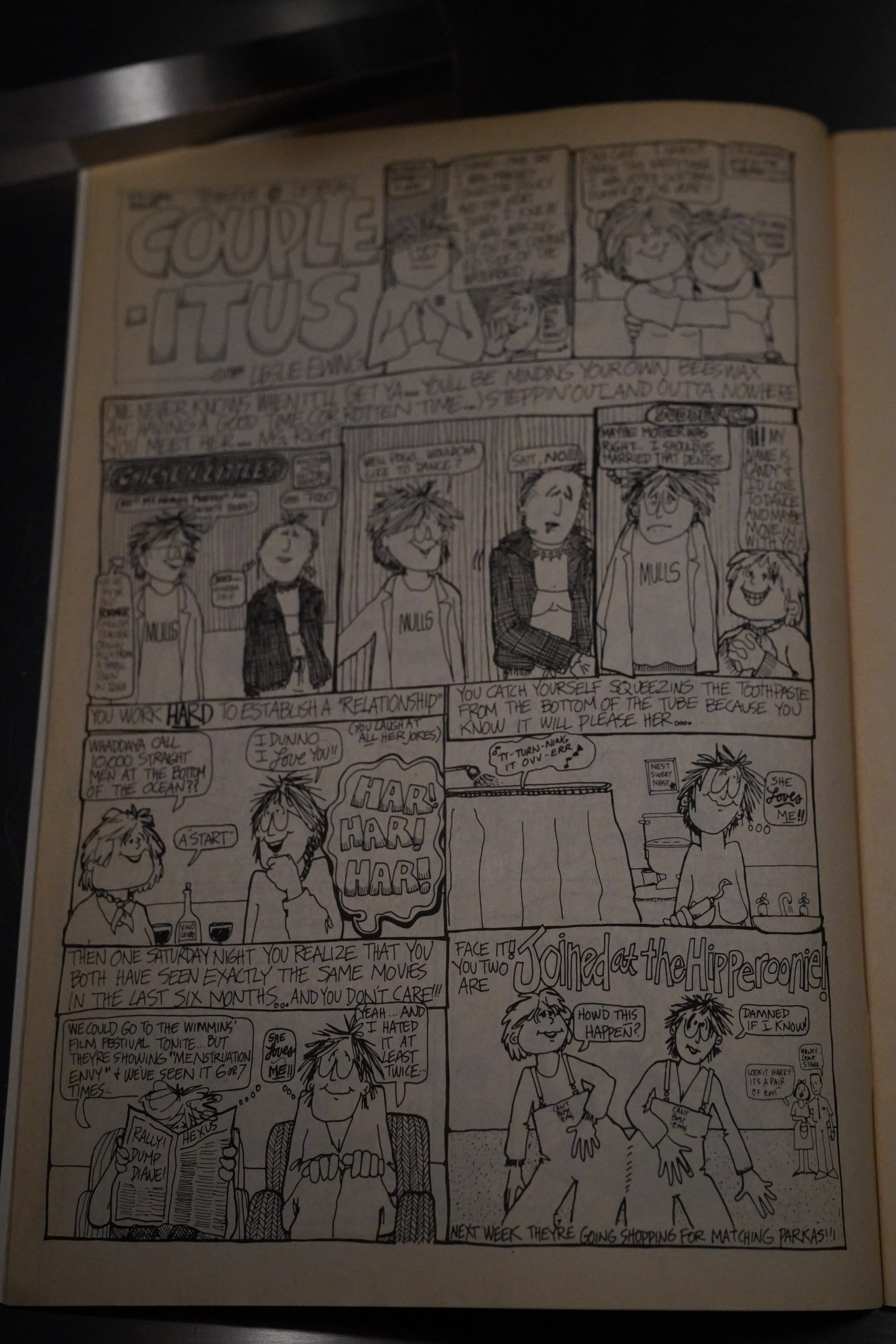

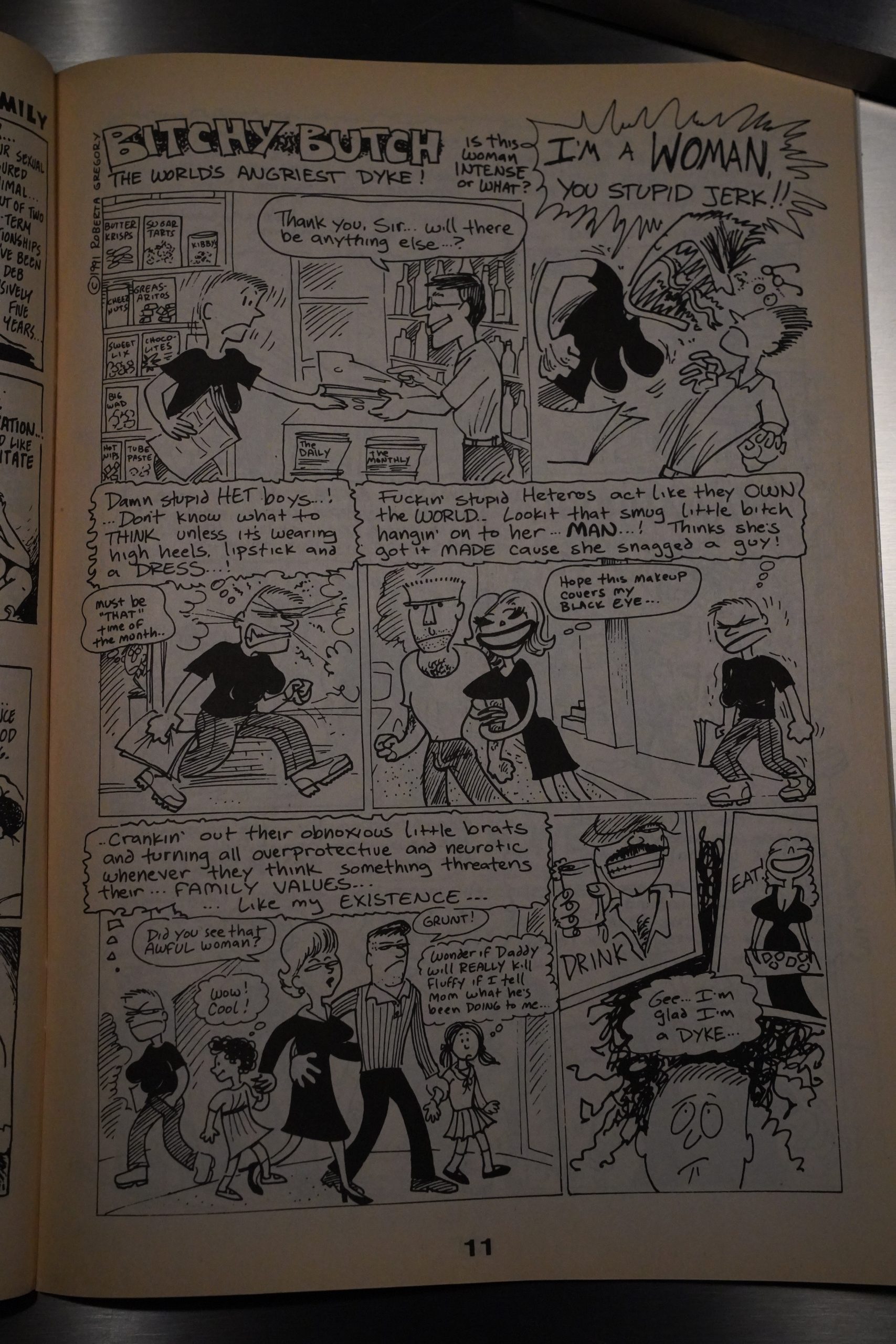

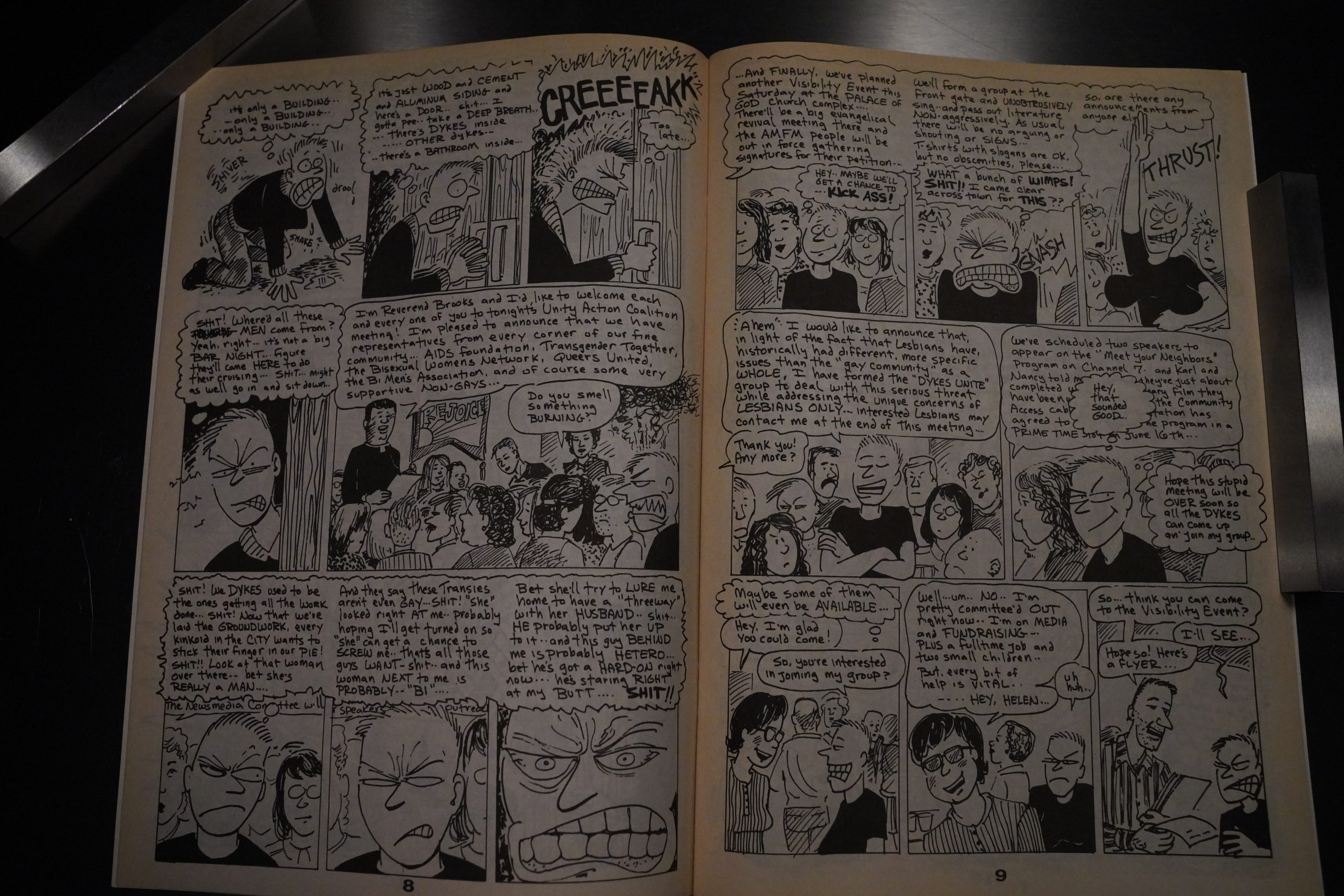

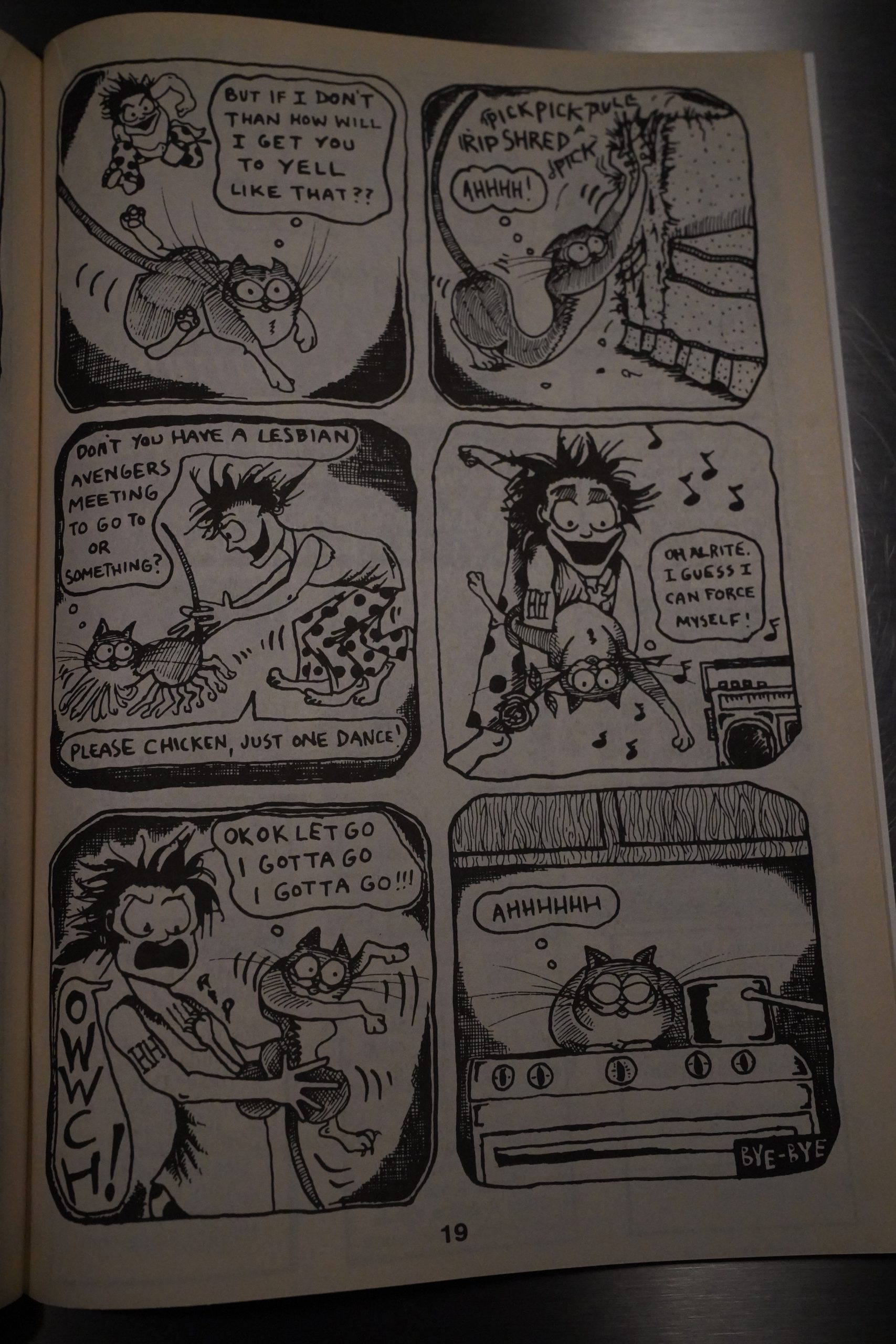

Roberta Gregory does longer pieces in most of the issues, and the first few are told in her inimitable everything-happens-at-the-same-time storytelling mode. It’s fun to read, but it’s also exhausting.

All the early issues have stories that are very, very dense. I guess that makes sense — the artists here seem to want to cram as much as possible into their allotted pages, perhaps because it wasn’t clear whether this was going to be an ongoing thing or a one-off, and they want their pieces to count.

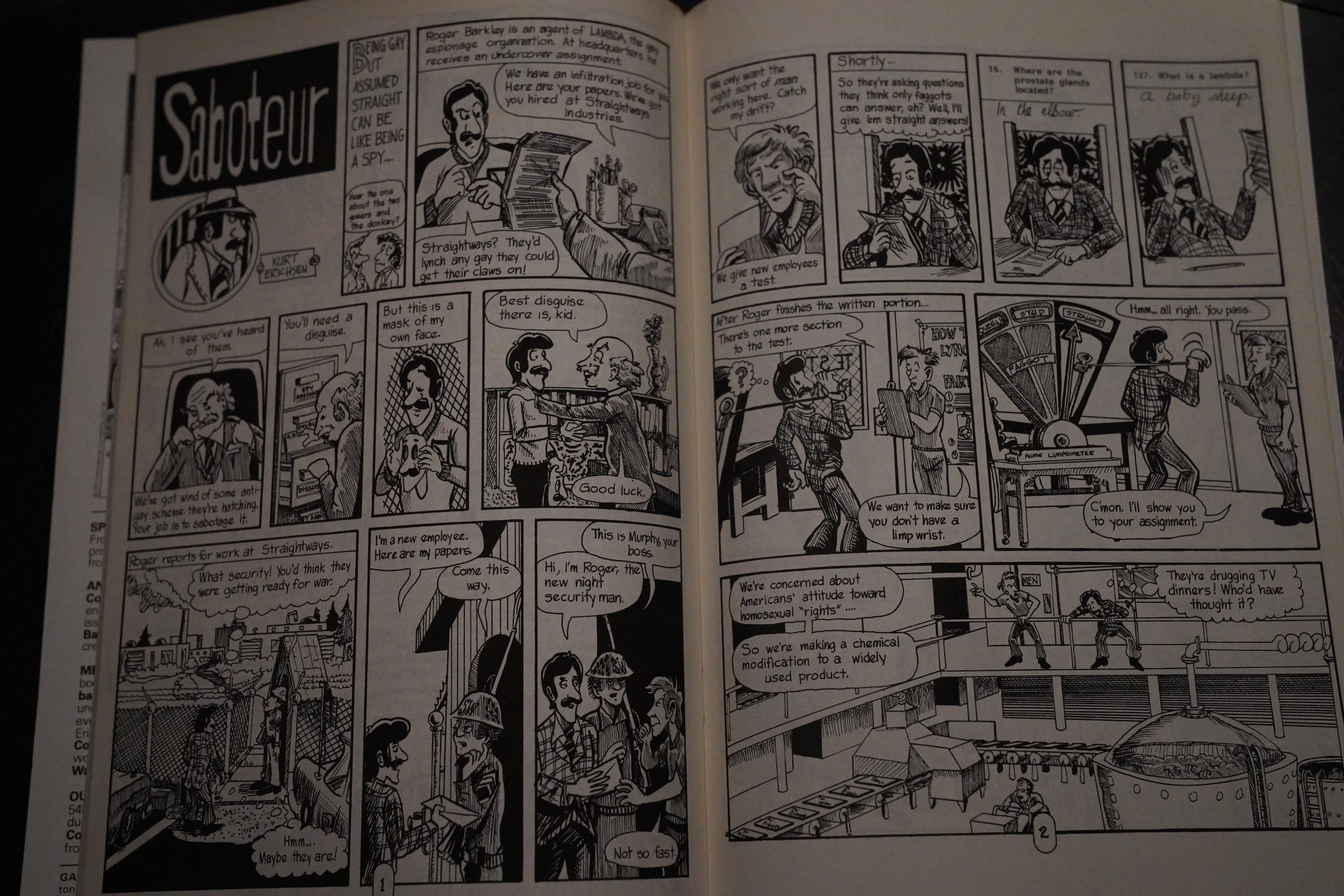

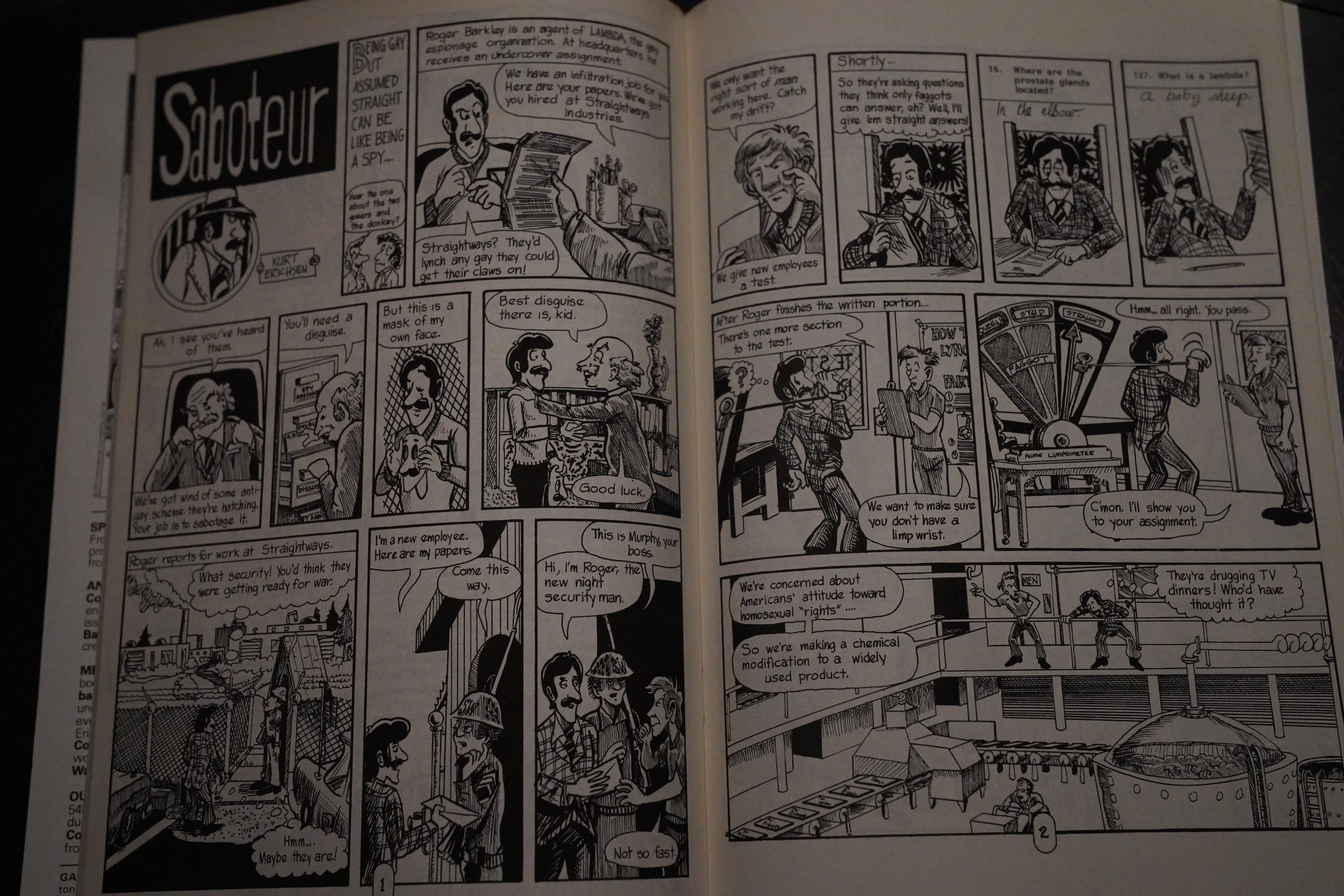

I think you could say that most of the pieces in the first issue are kinda serious in one way or another (even when doing gags). Kurt Erichsen is the only one that goes totally frivolous. And I don’t know whether that’s because of editorial direction, or, again, because they thought that this was the only shot they had here.

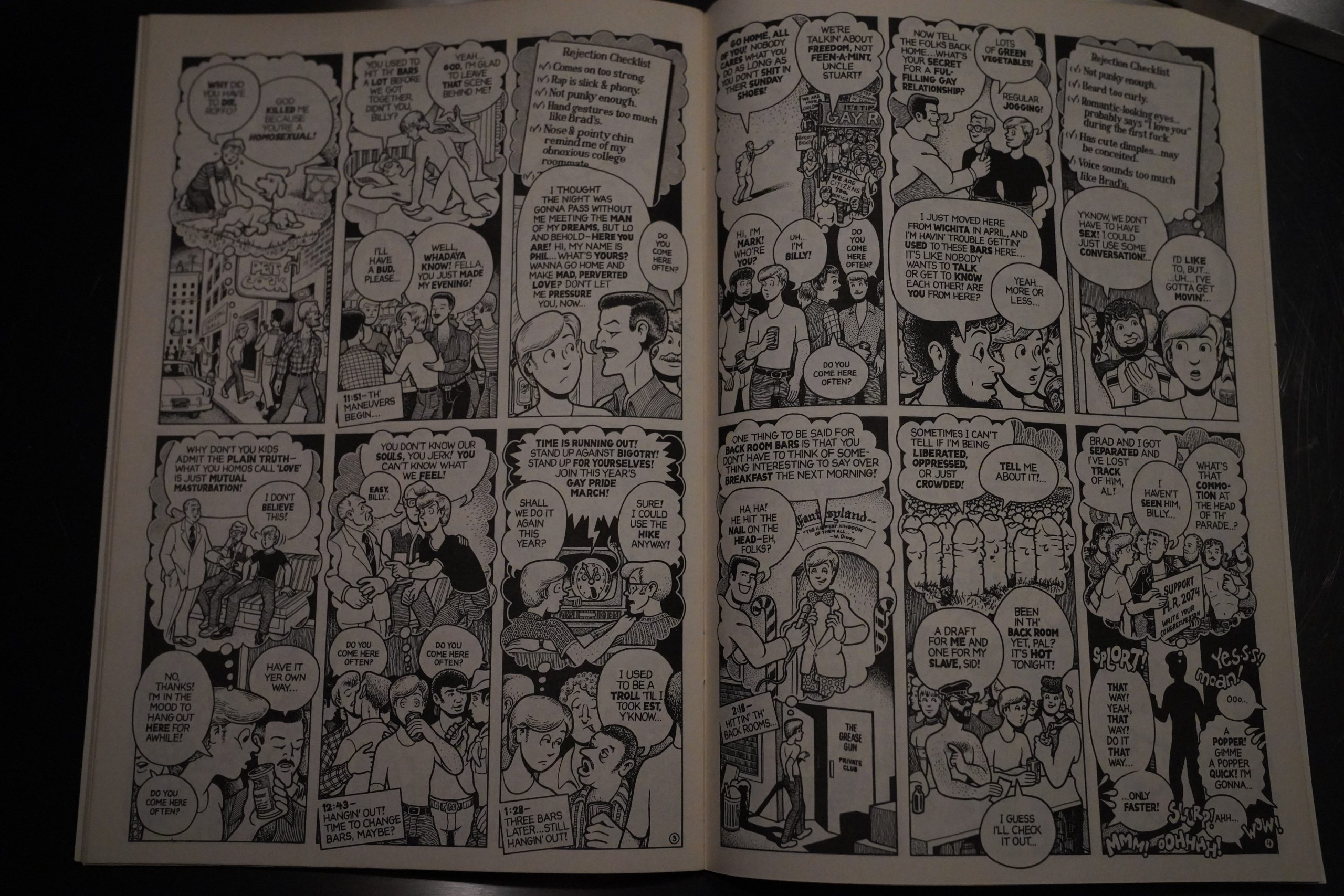

The piece that has the greatest impact in the first issue is definitely Cruse’s own amazing Billy Goes Out, which (again) is super dense — it packs so much into these seven pages that you feel you’ve read an epic — but it also packs a huge emotional wallop. It’s funny and it’s heartbreaking.

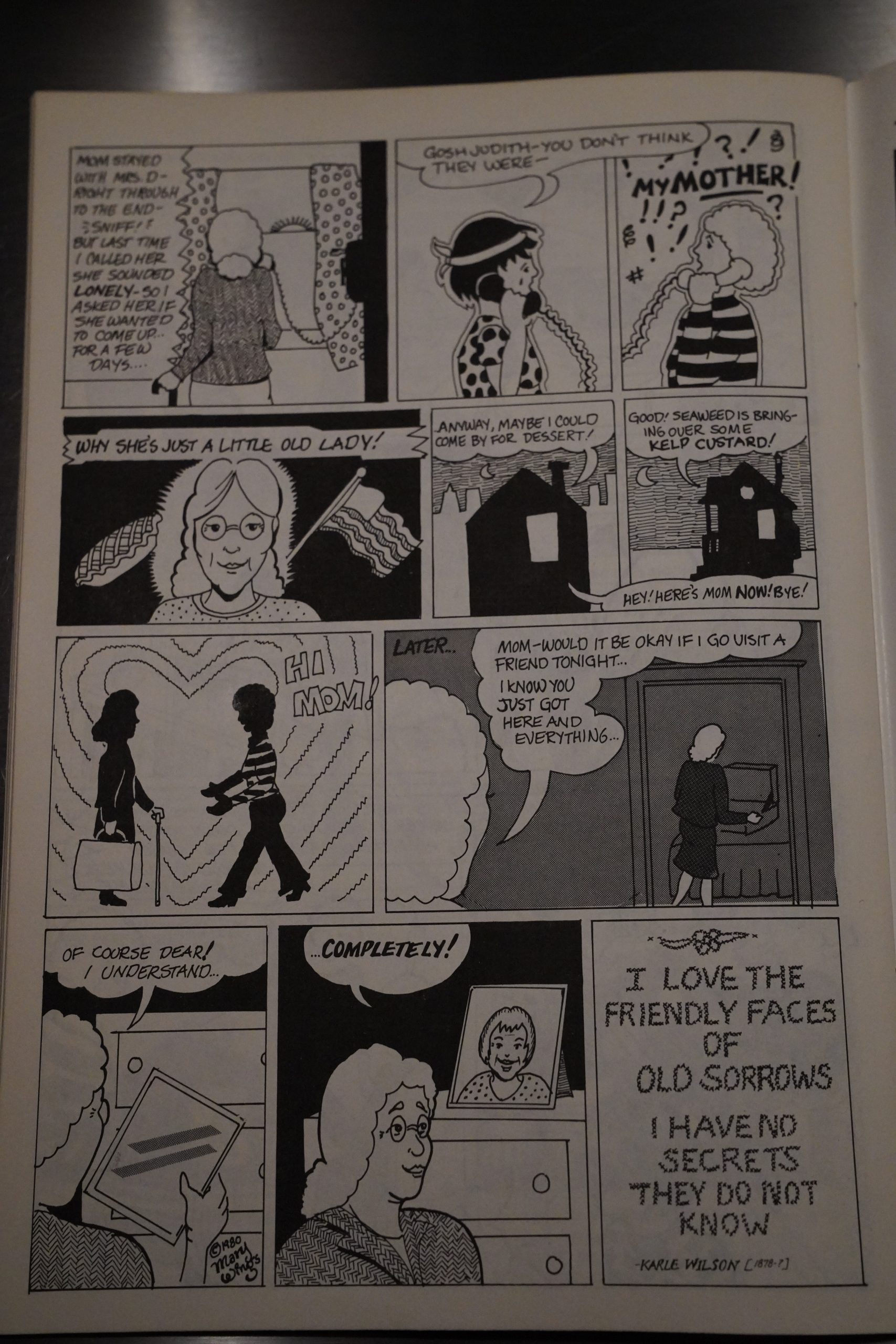

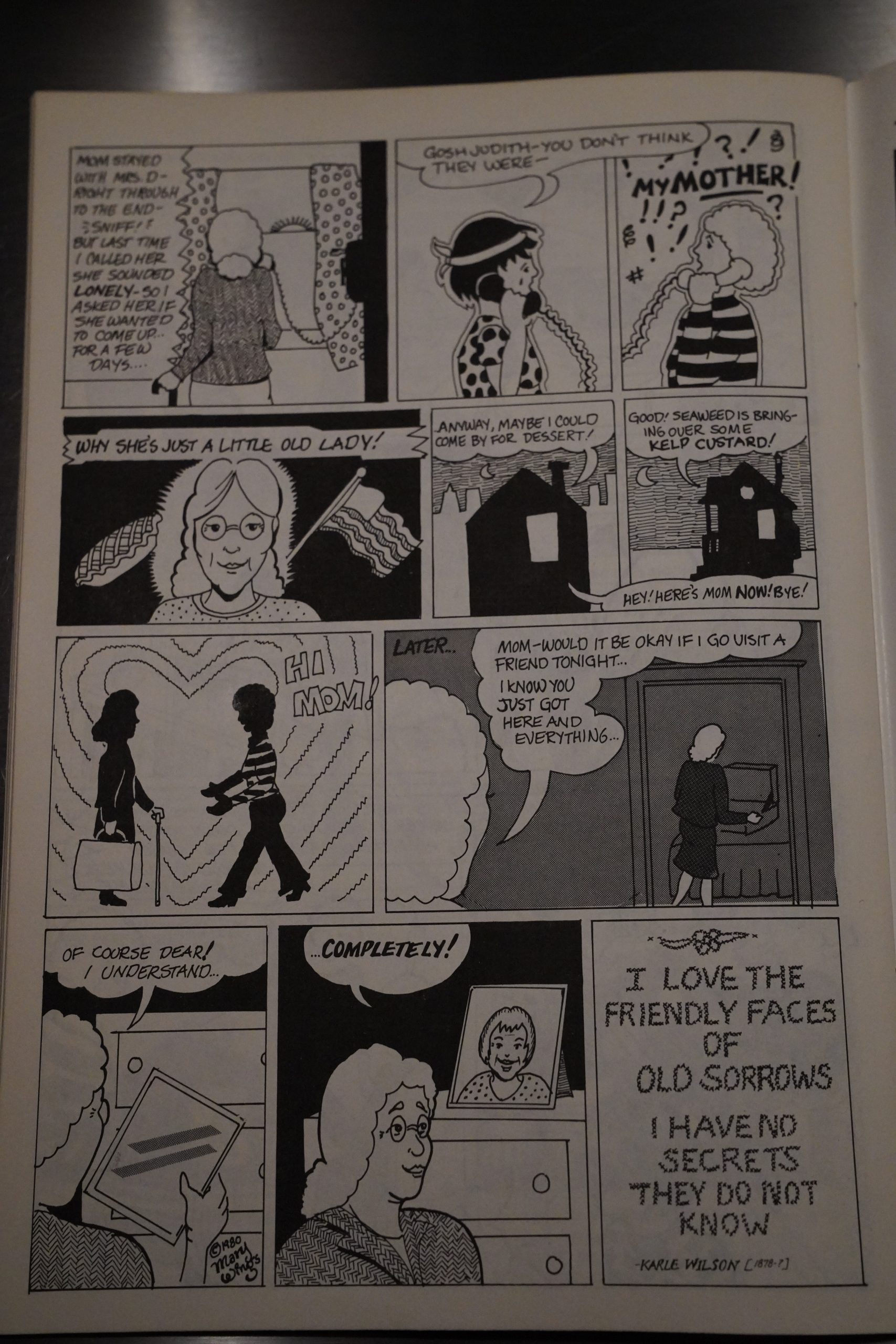

Mary Wings rounds out the issue with a very sweet little piece. (Wings produced the first lesbian comic book with Come Out Comix in 1973, so it’s fun to see her in this first issue of Gay Comix.)

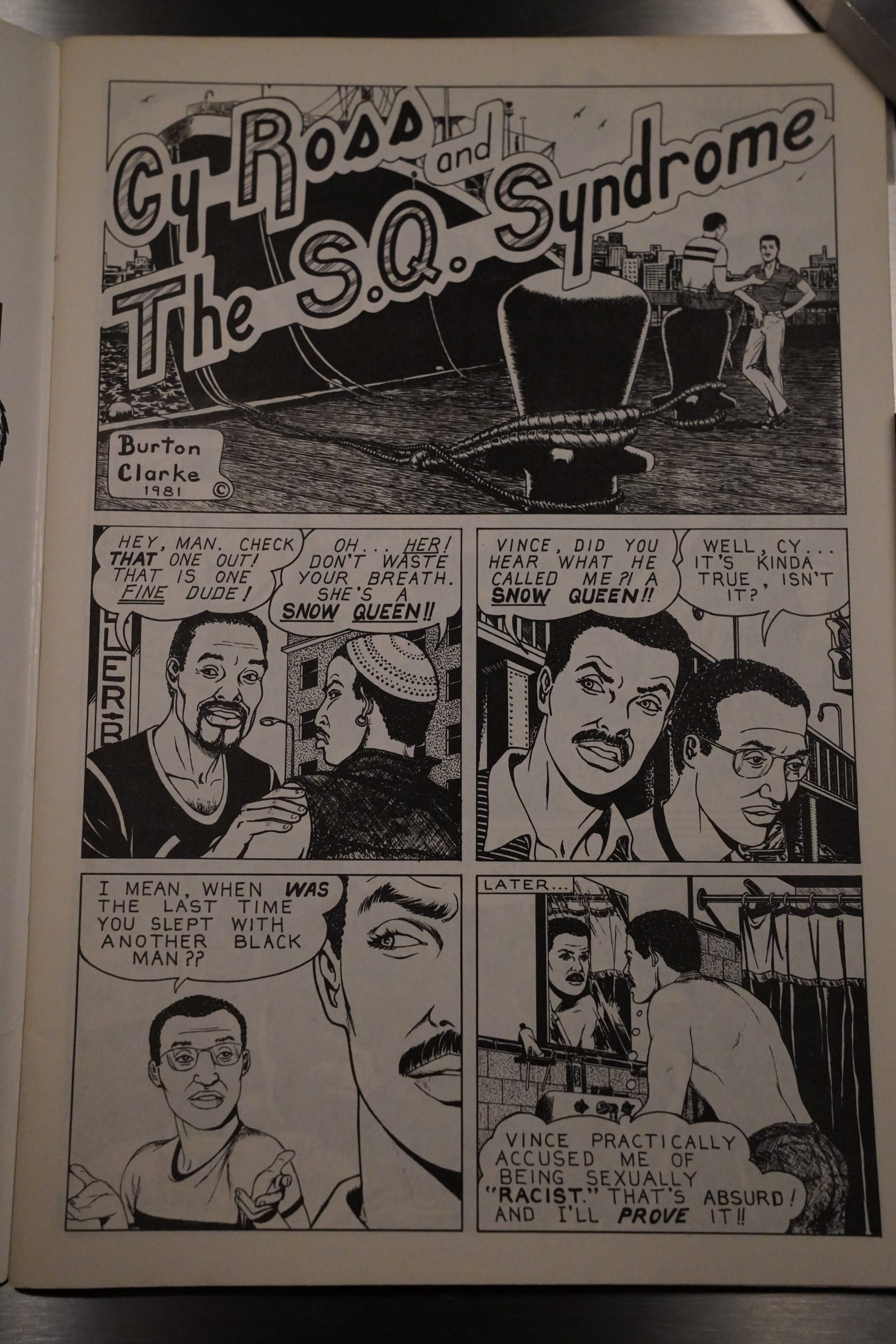

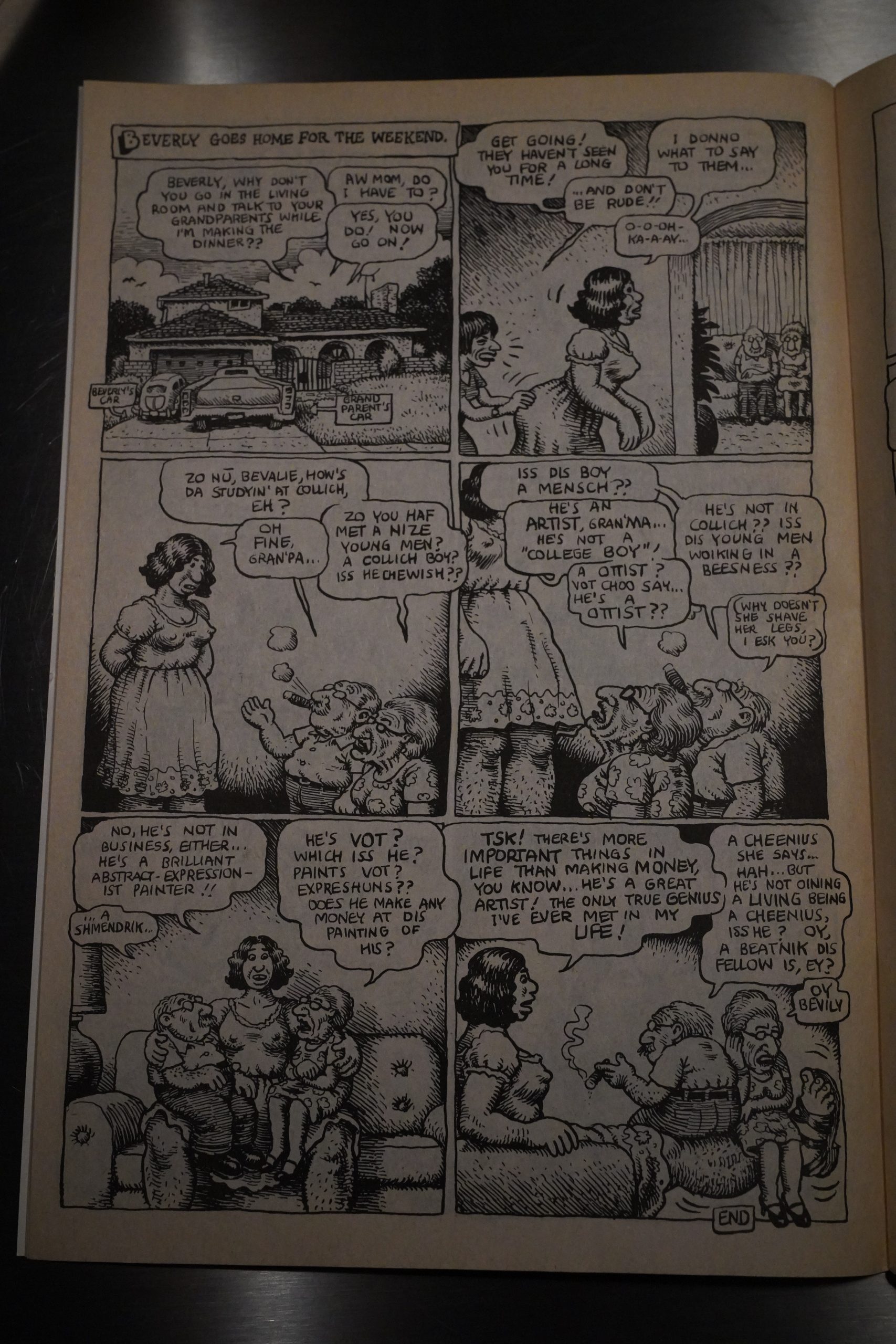

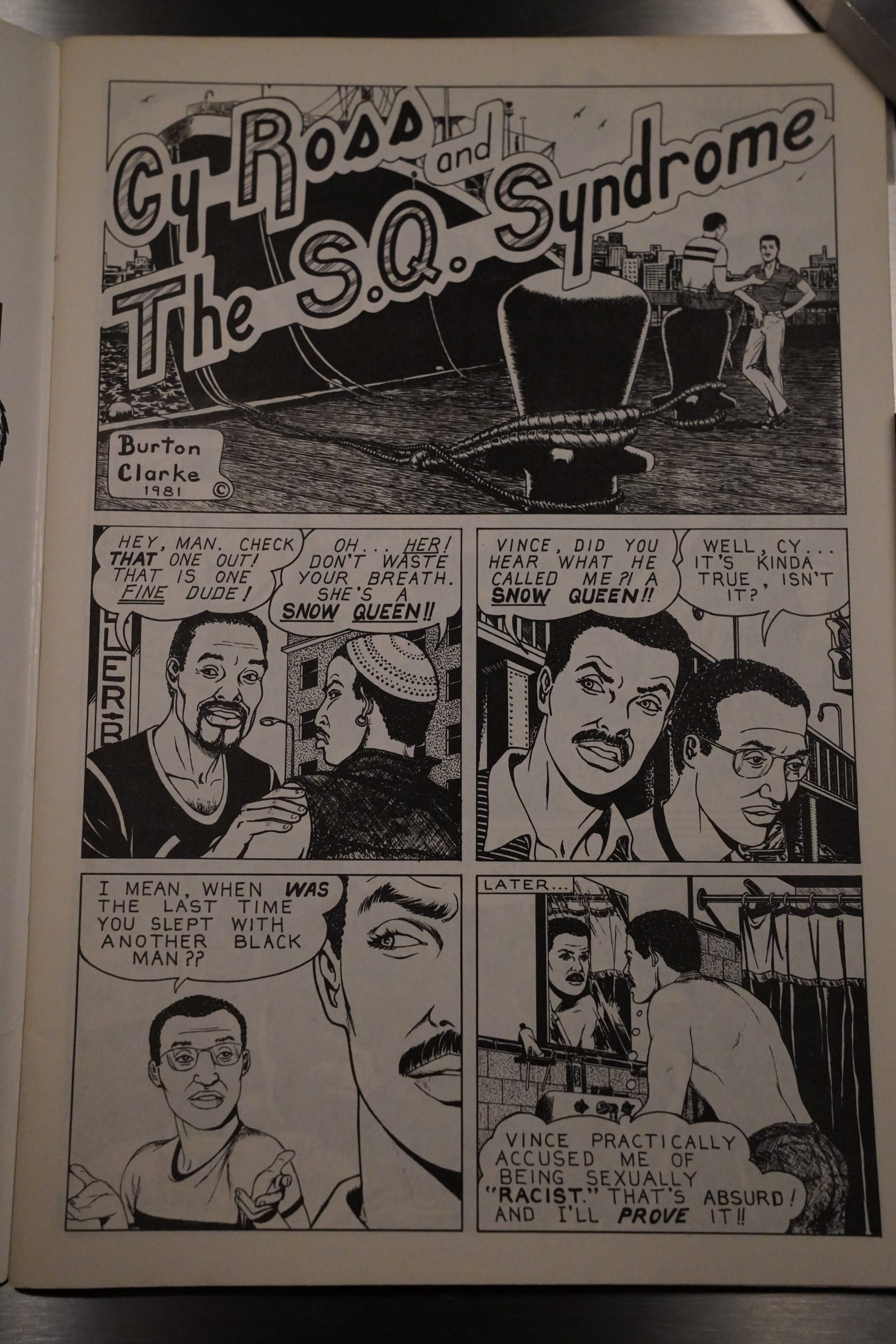

In the second issue, the book up beyond the pool of underground staples. Burton Clarke writes a hilarious piece about a guy being accused of being a Snow Queen.

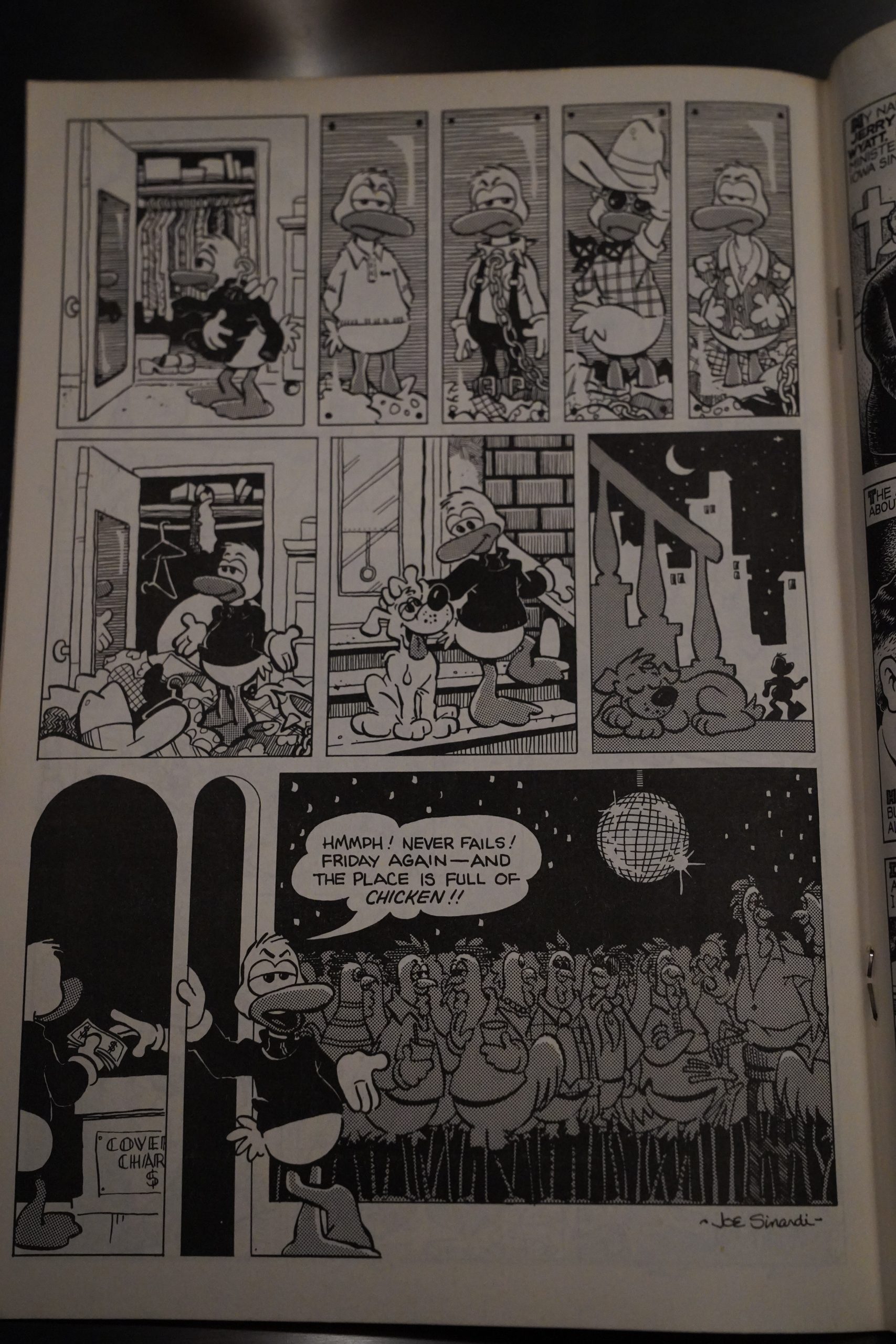

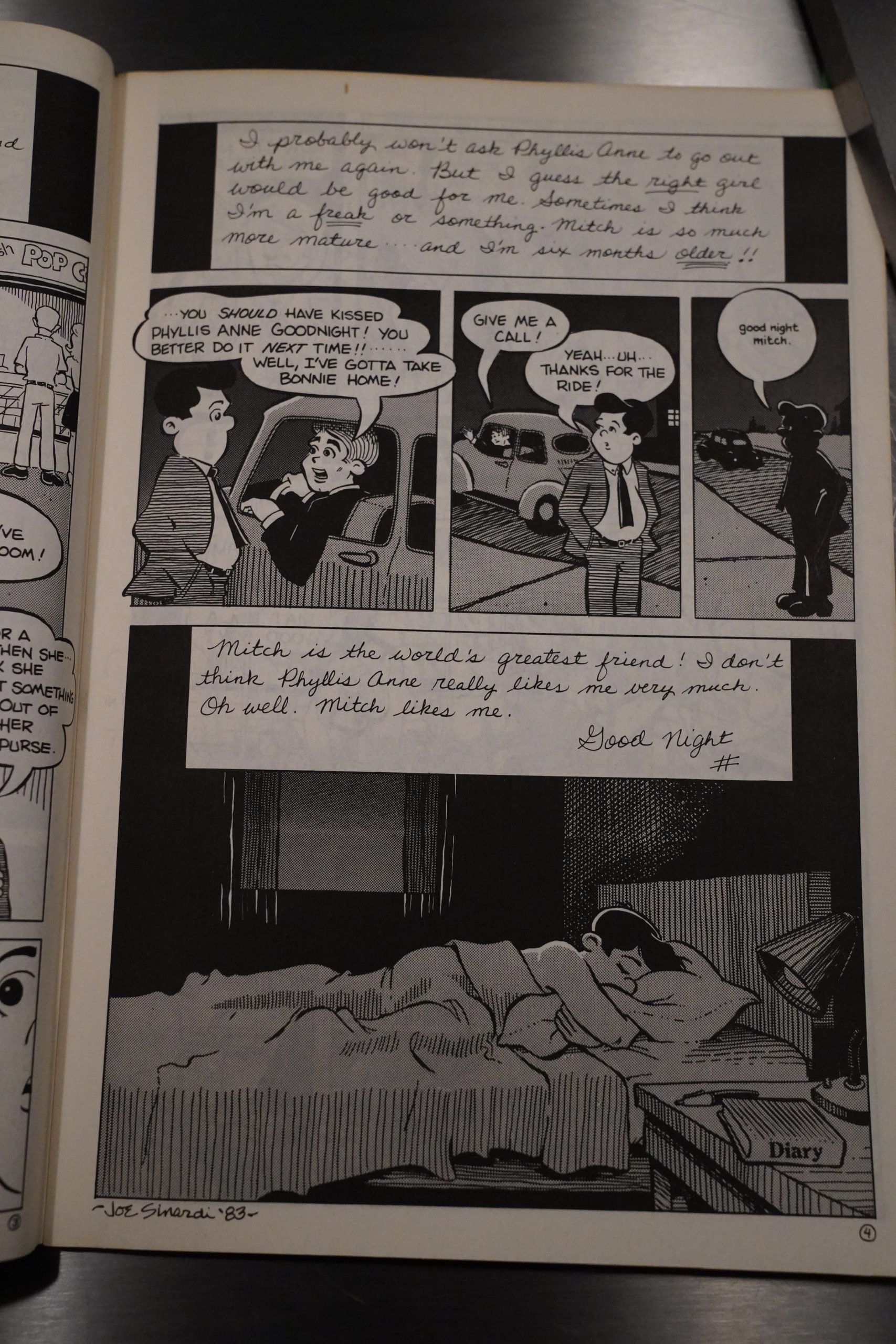

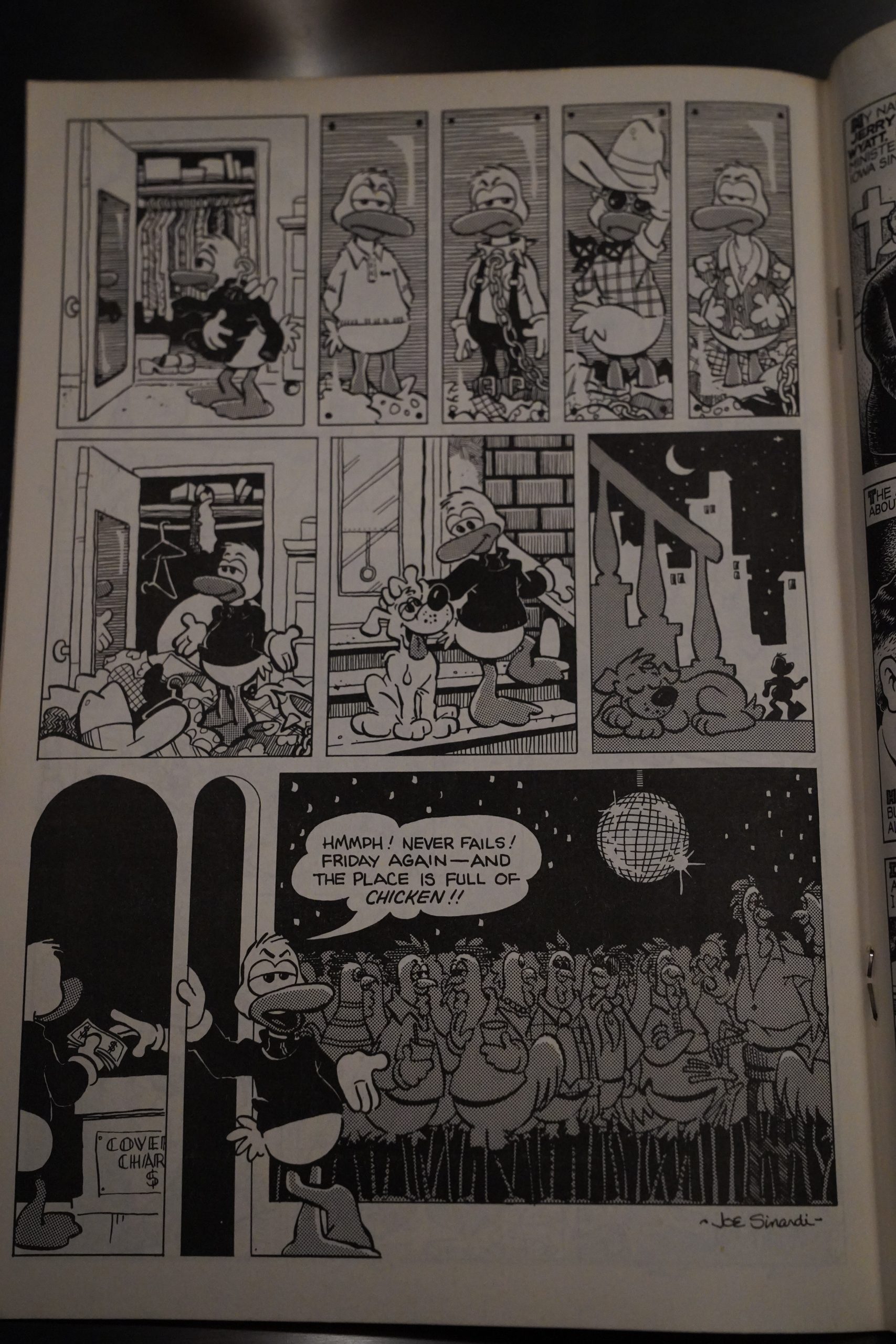

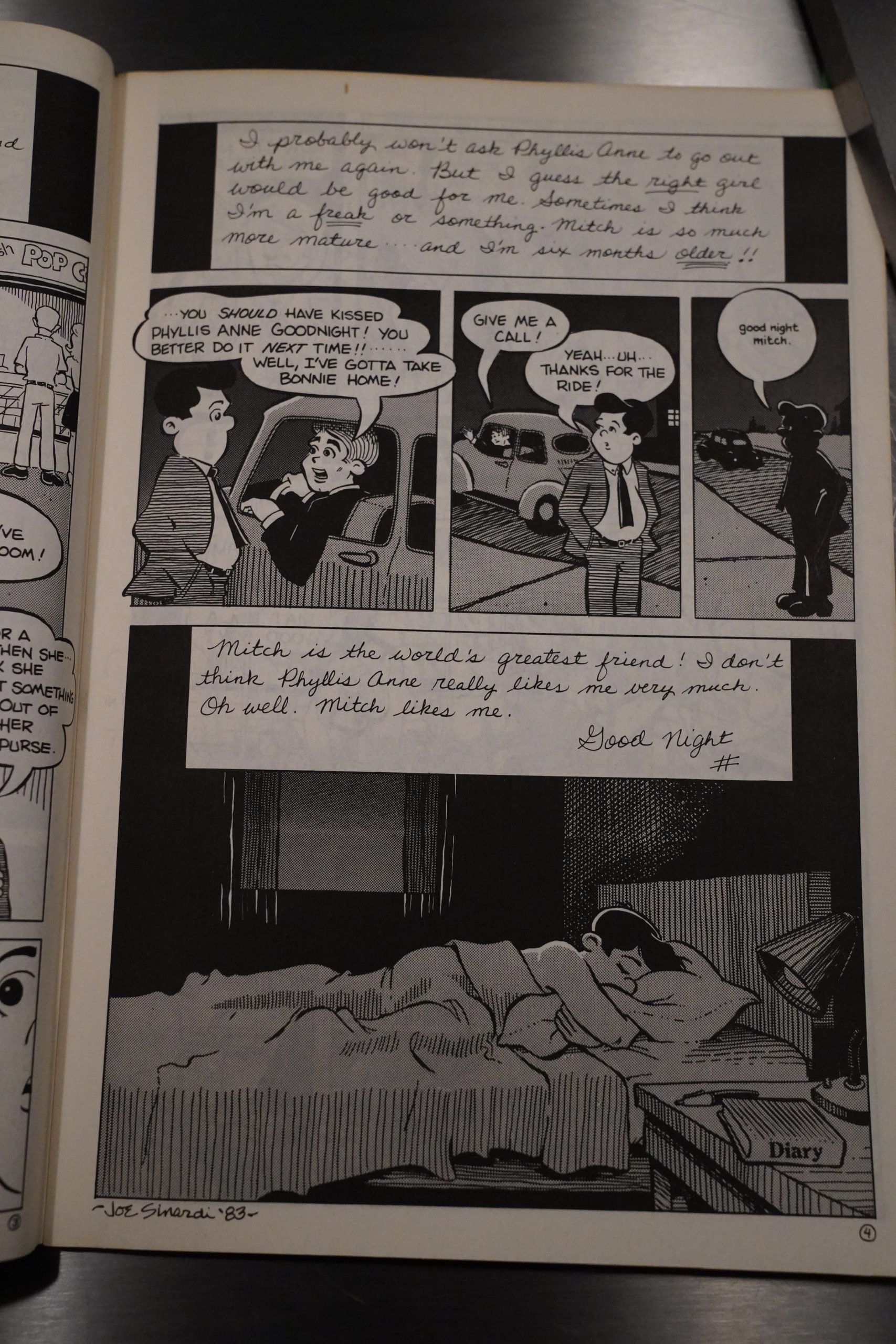

Joe Sinardi (who would later do Maxwell Mouse Funnies with Renegade Press) does a gag about hitting the bars.

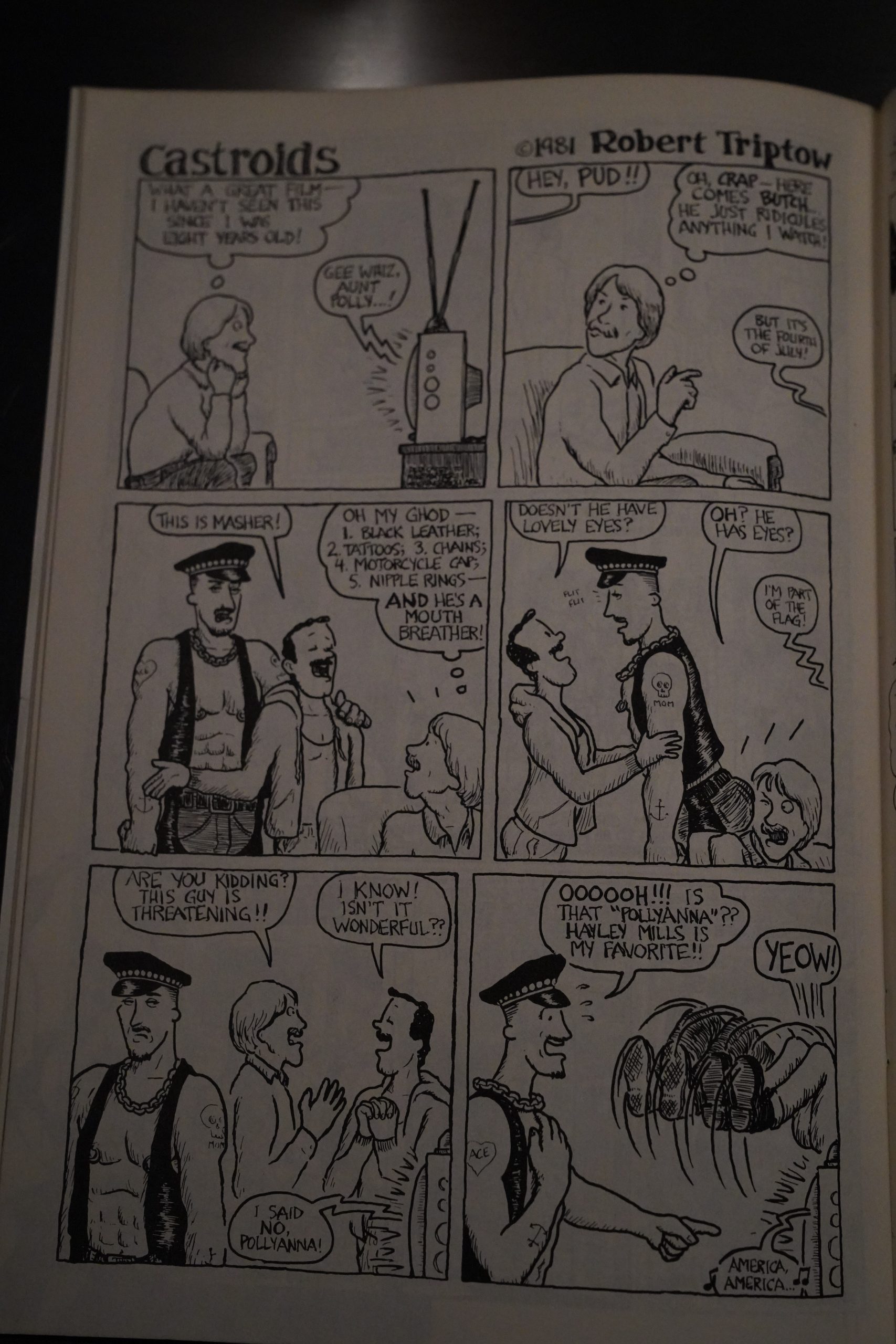

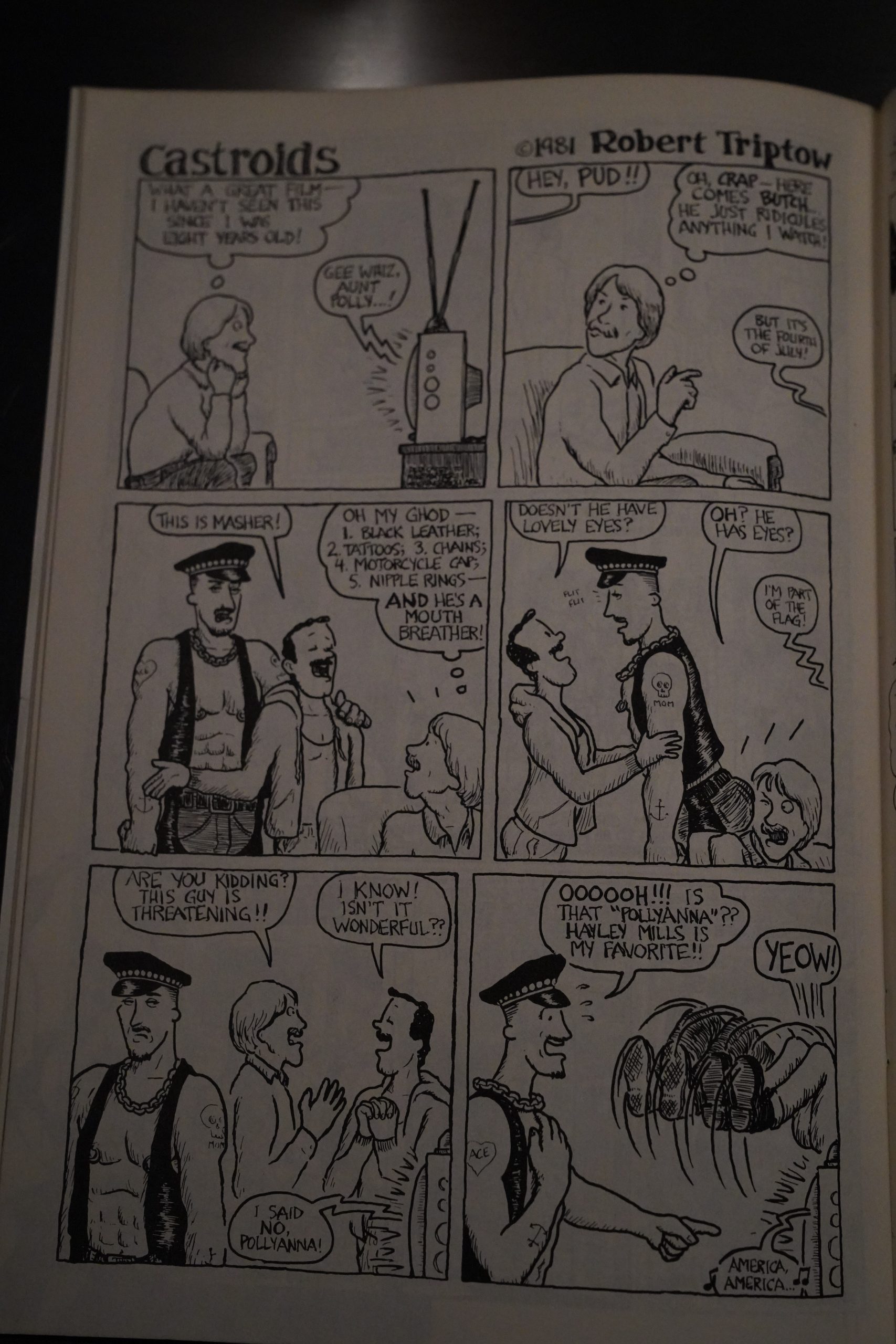

Heh heh. “Castroids”. Robert Triptow would take over editing with the fifth issue, but was featured starting in the second.

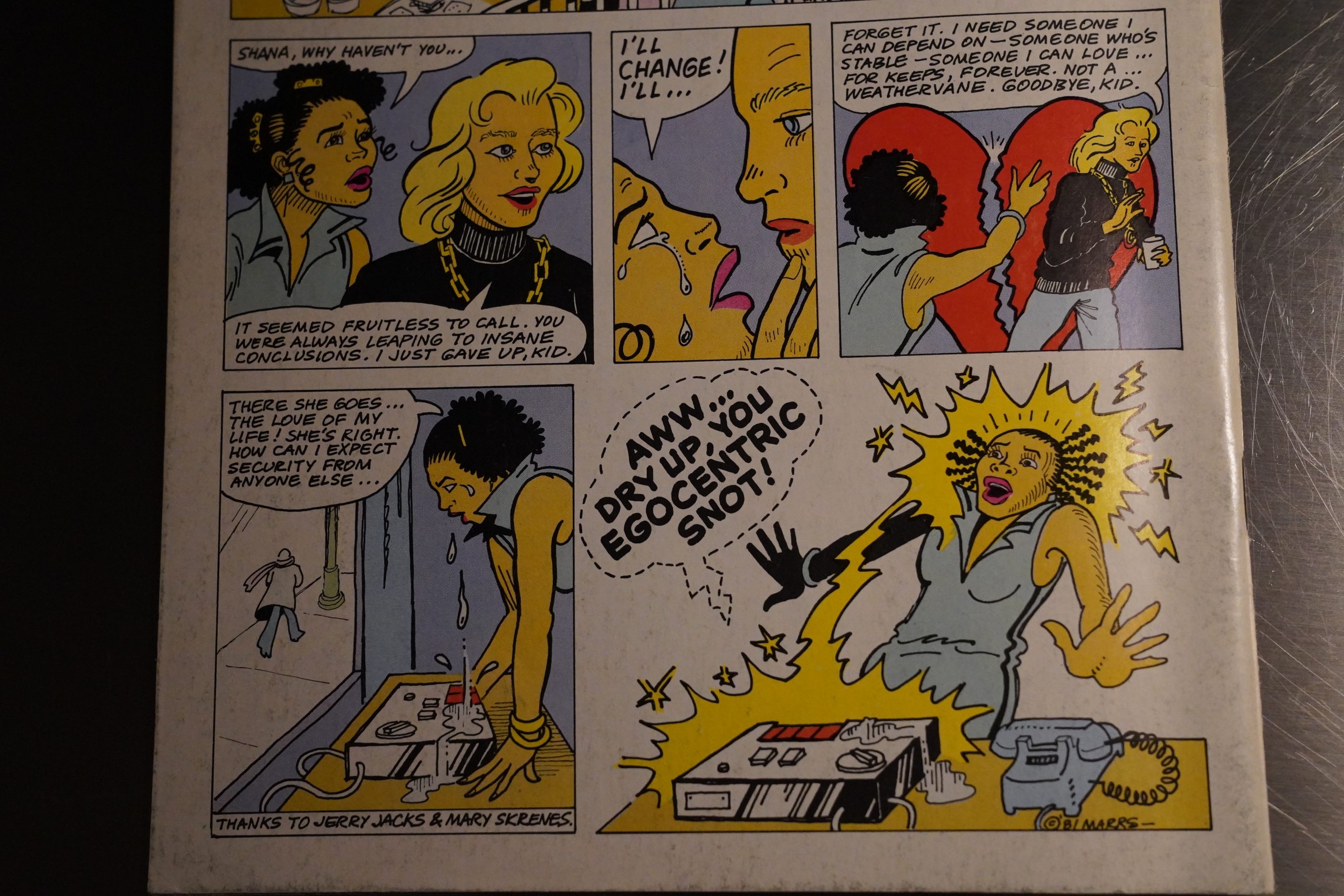

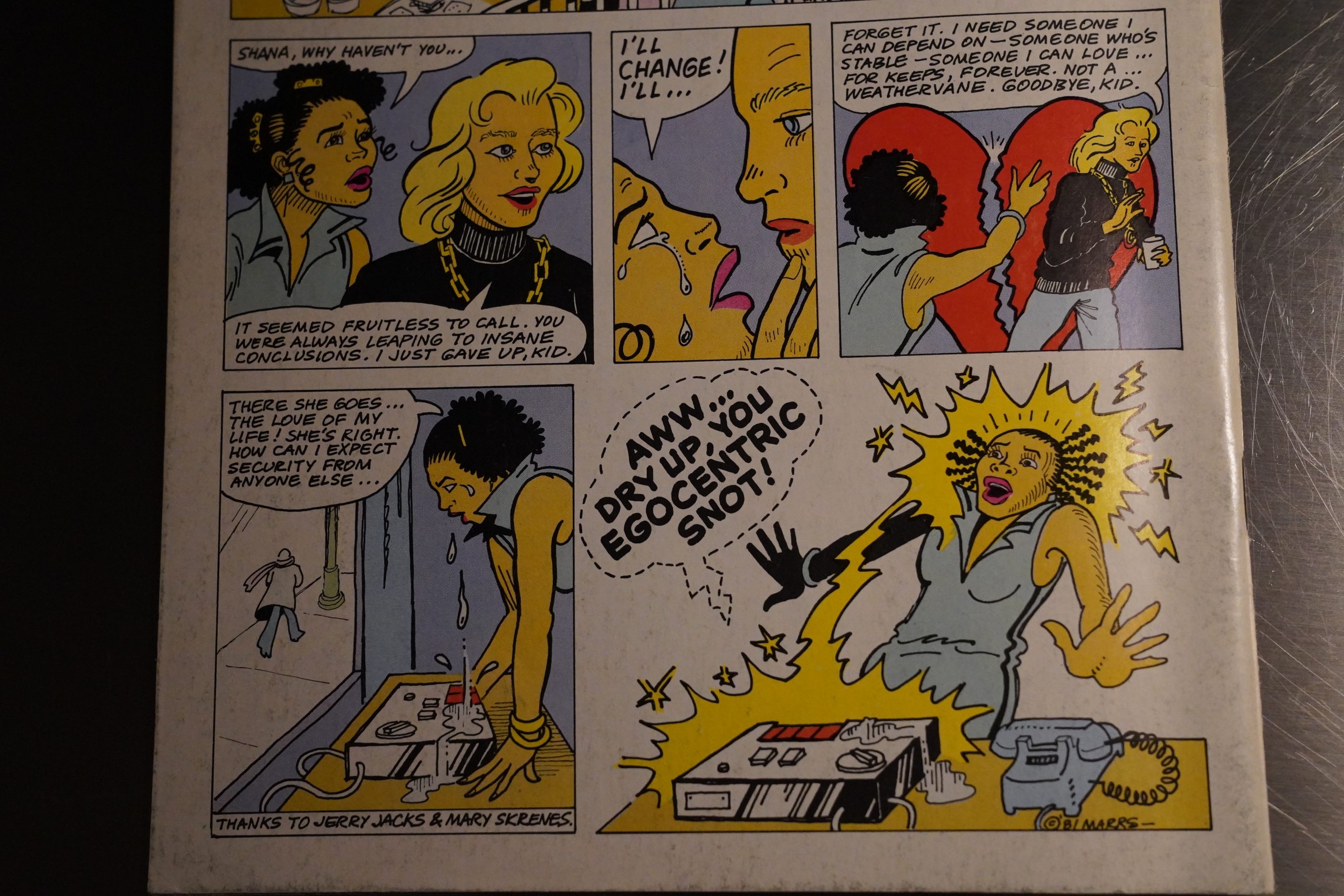

The range of stories and approaches is huge. Lee Marrs does this kinda deranged thing about obsessive love, which… doesn’t end the way these things usually do? And I guess you can’t really say that it’s a very cohesive anthology, but it does hang together somehow. That is, it sometimes feels like it’s just a random collection of things, but it’s readable nevertheless.

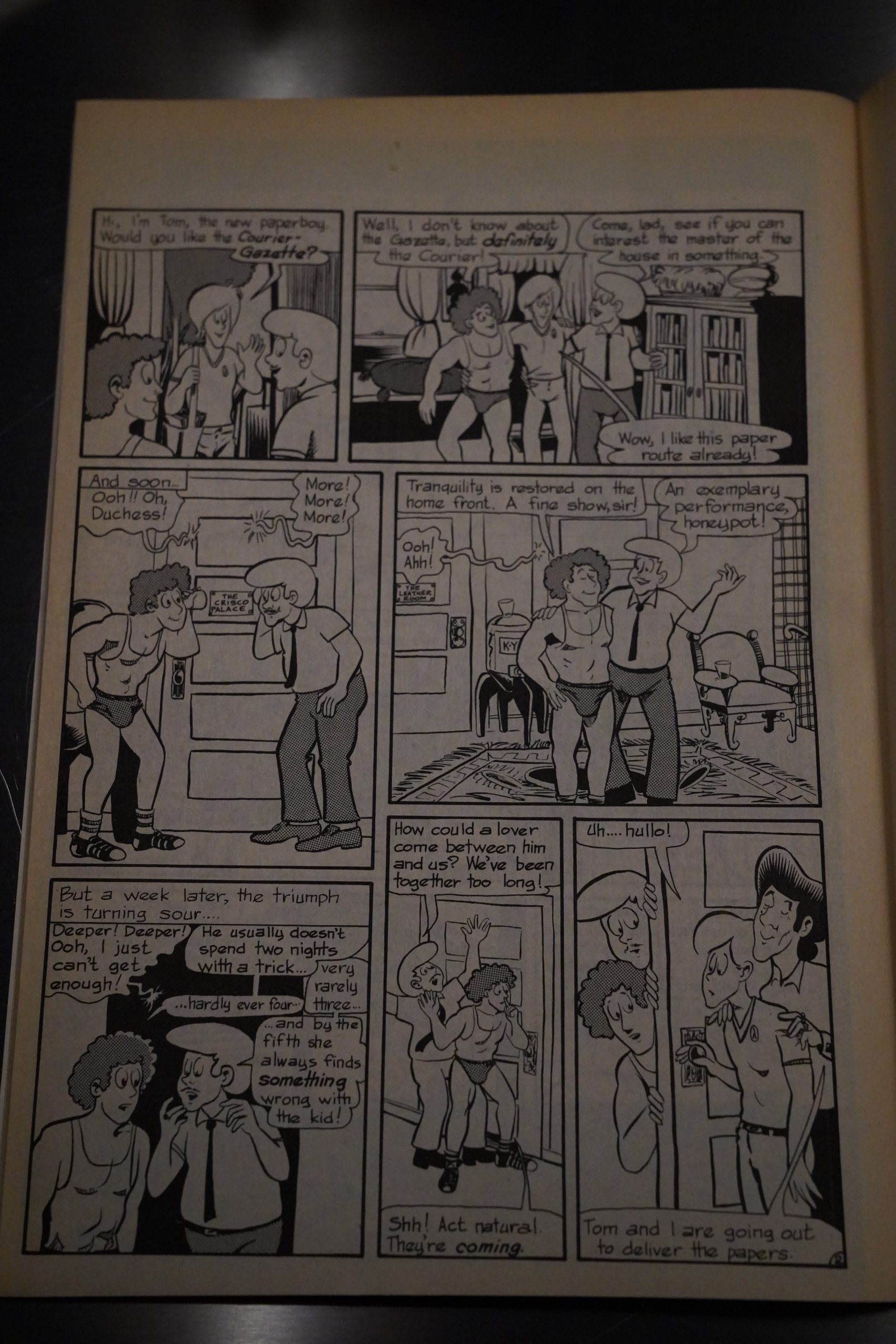

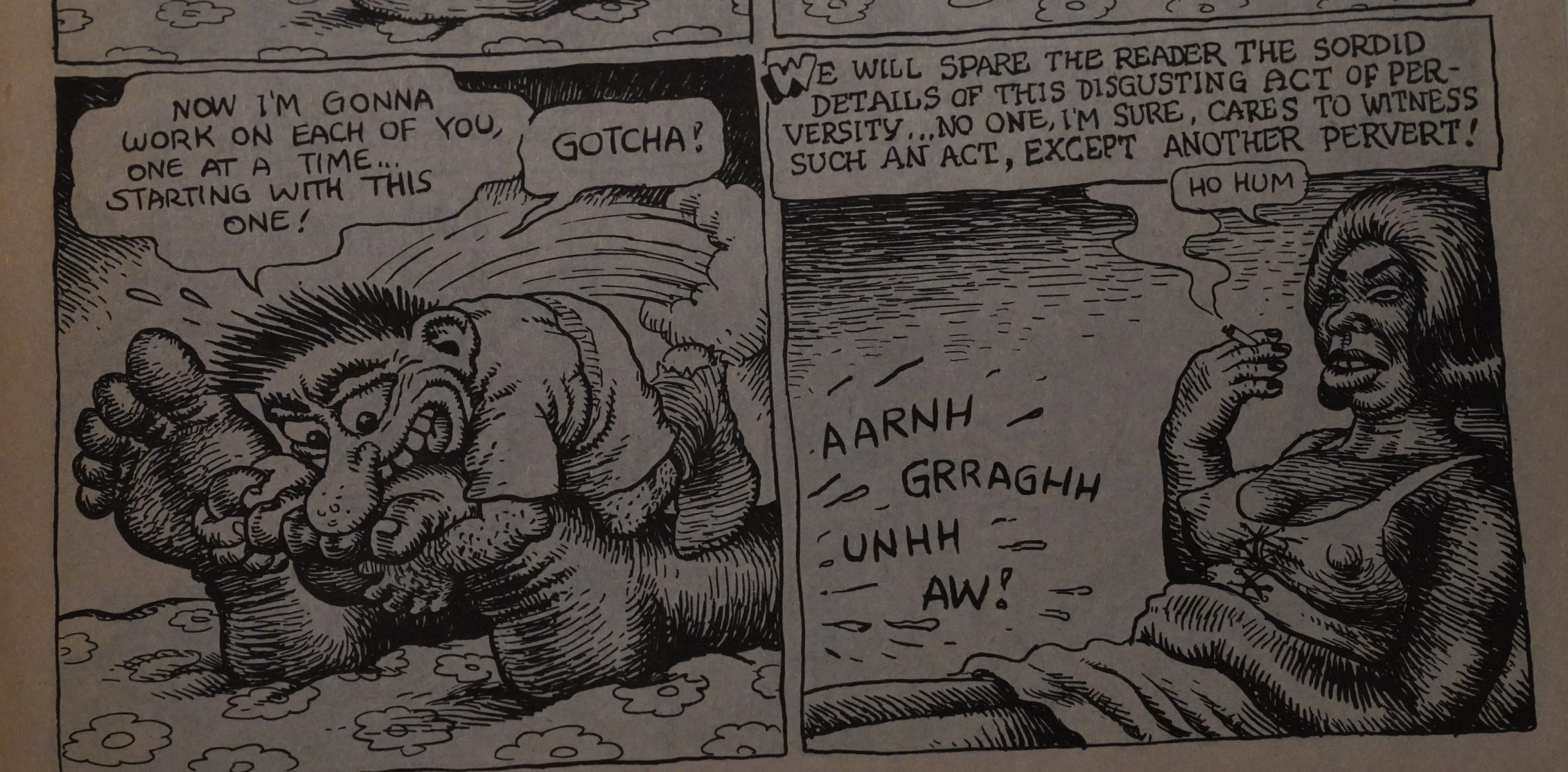

There is some nudity in this book, and some sex, but very few of the pieces are centred on sex. There’s two pieces by Theo Bogart (one page each) that I’m definitely not snapshotting here, because they’re probably illegal in many jurisdictions, and they stand out like sore, er, thumbs? I wonder what Cruse’s rationale for including those two pages were — if accused of obscenity, you could make a pretty good argument for why any of the other pieces aren’t obscene (under LAW IN YOUR AREA), but it’d be pretty hard (er) with these two… It seems oddly like baiting the prudes or something…

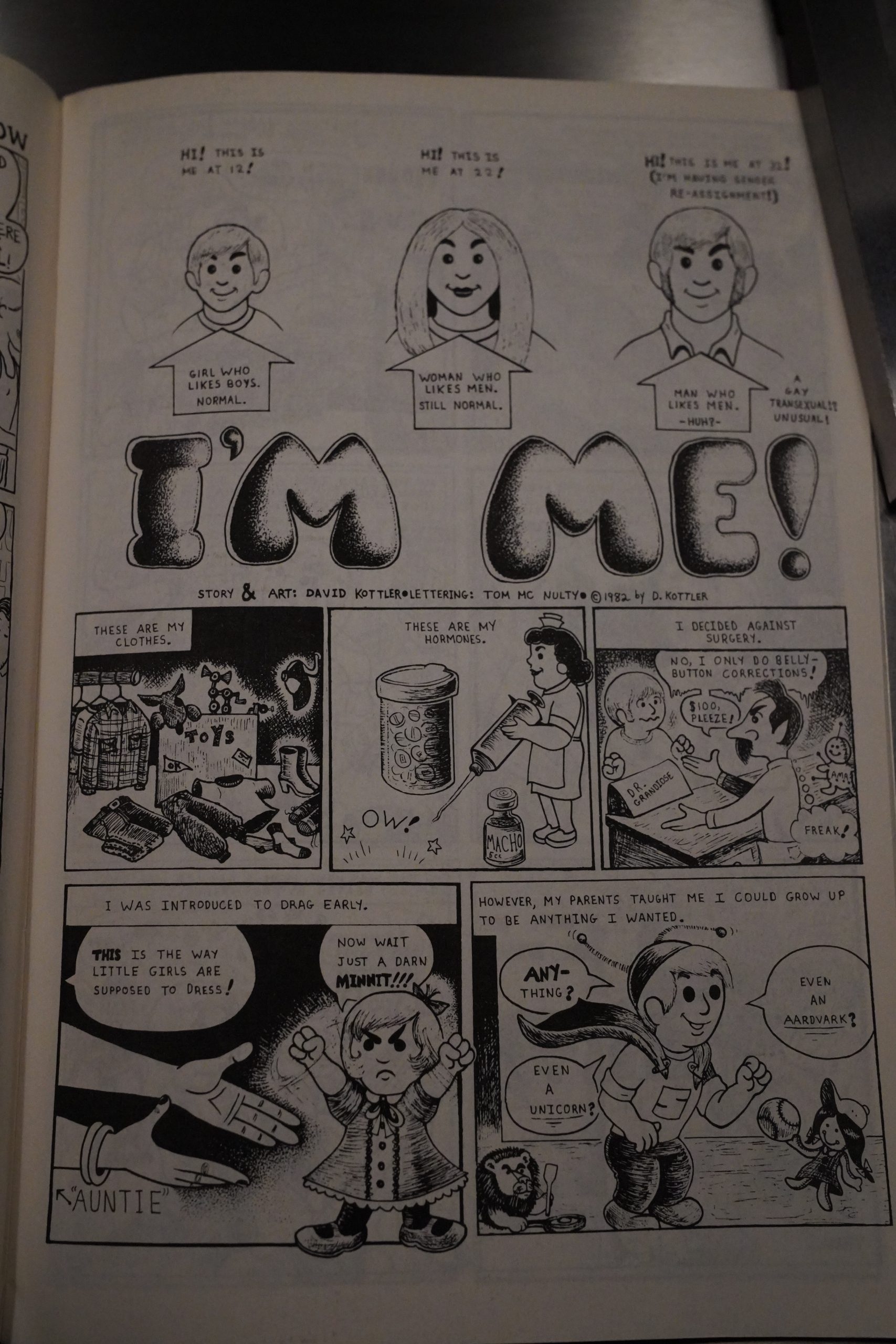

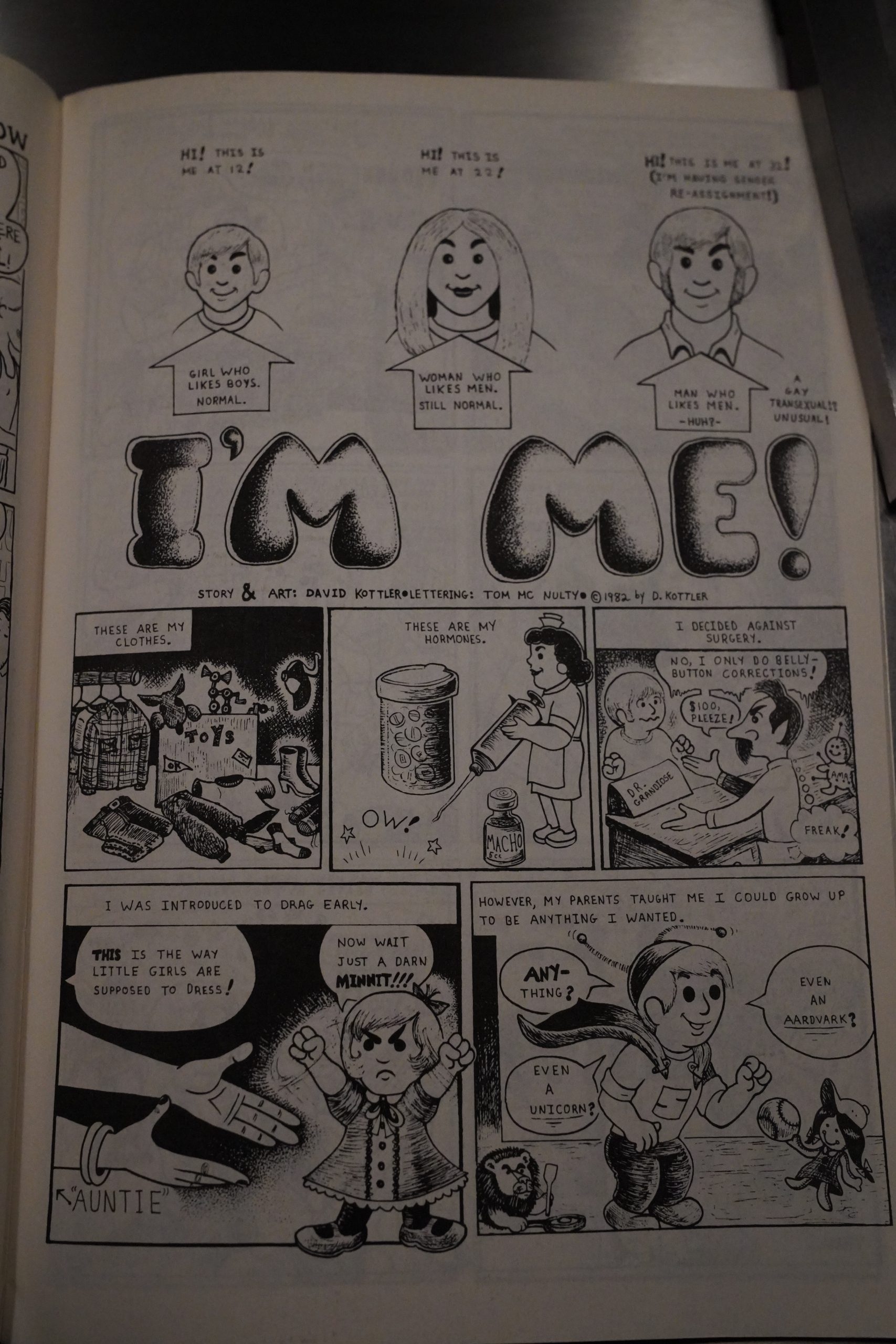

In the third issue, we have the first trans appearance, with this piece by David Kottler.

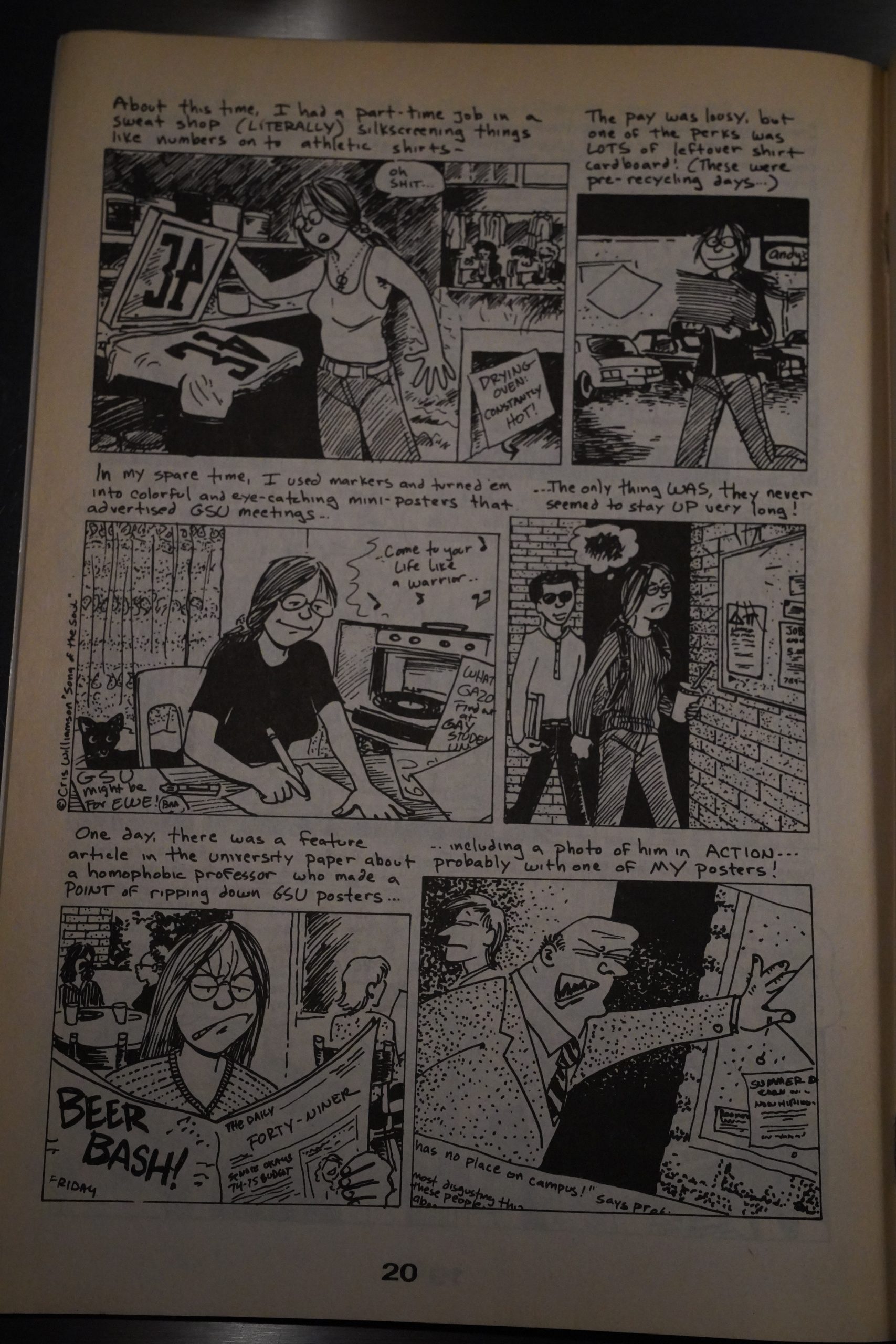

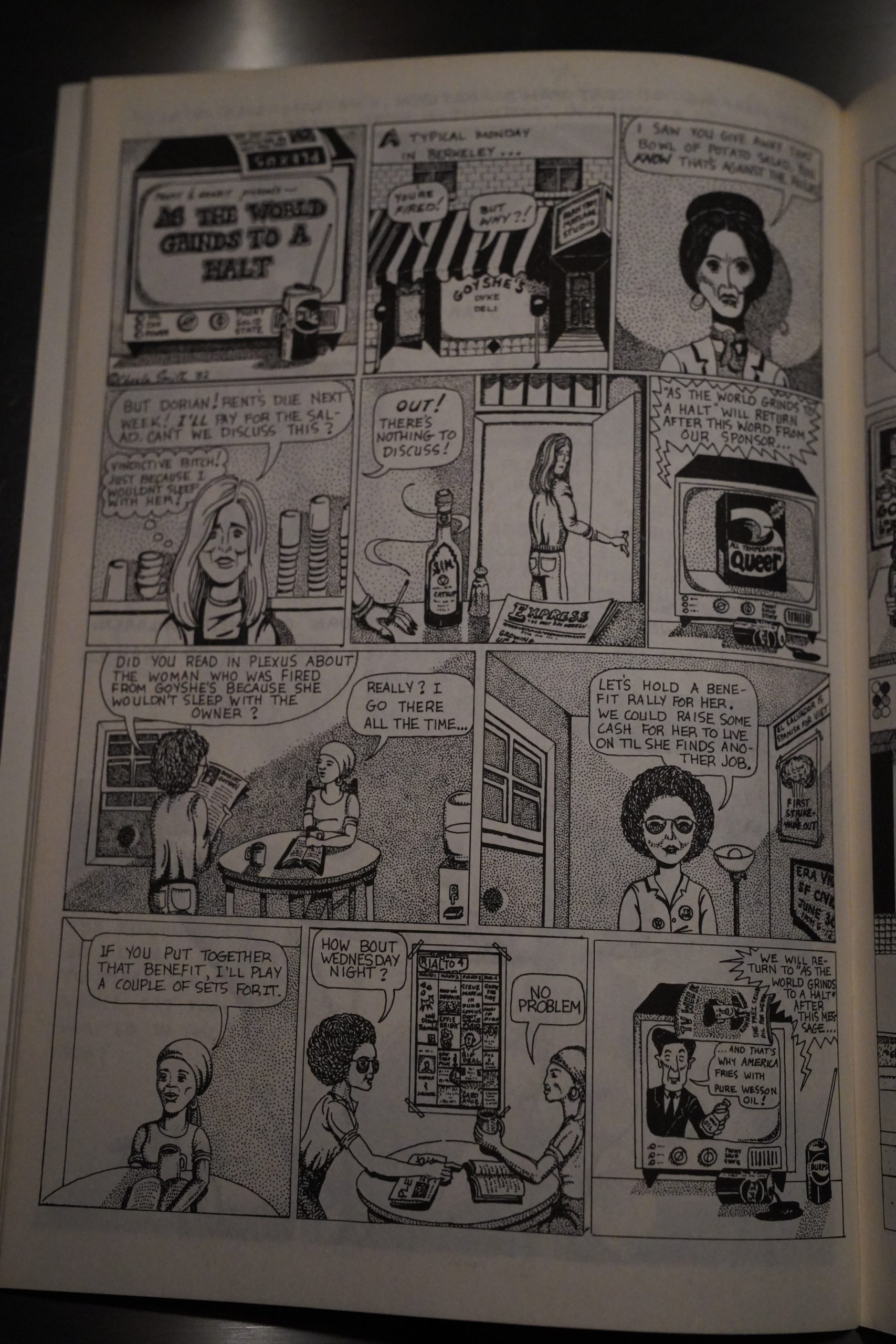

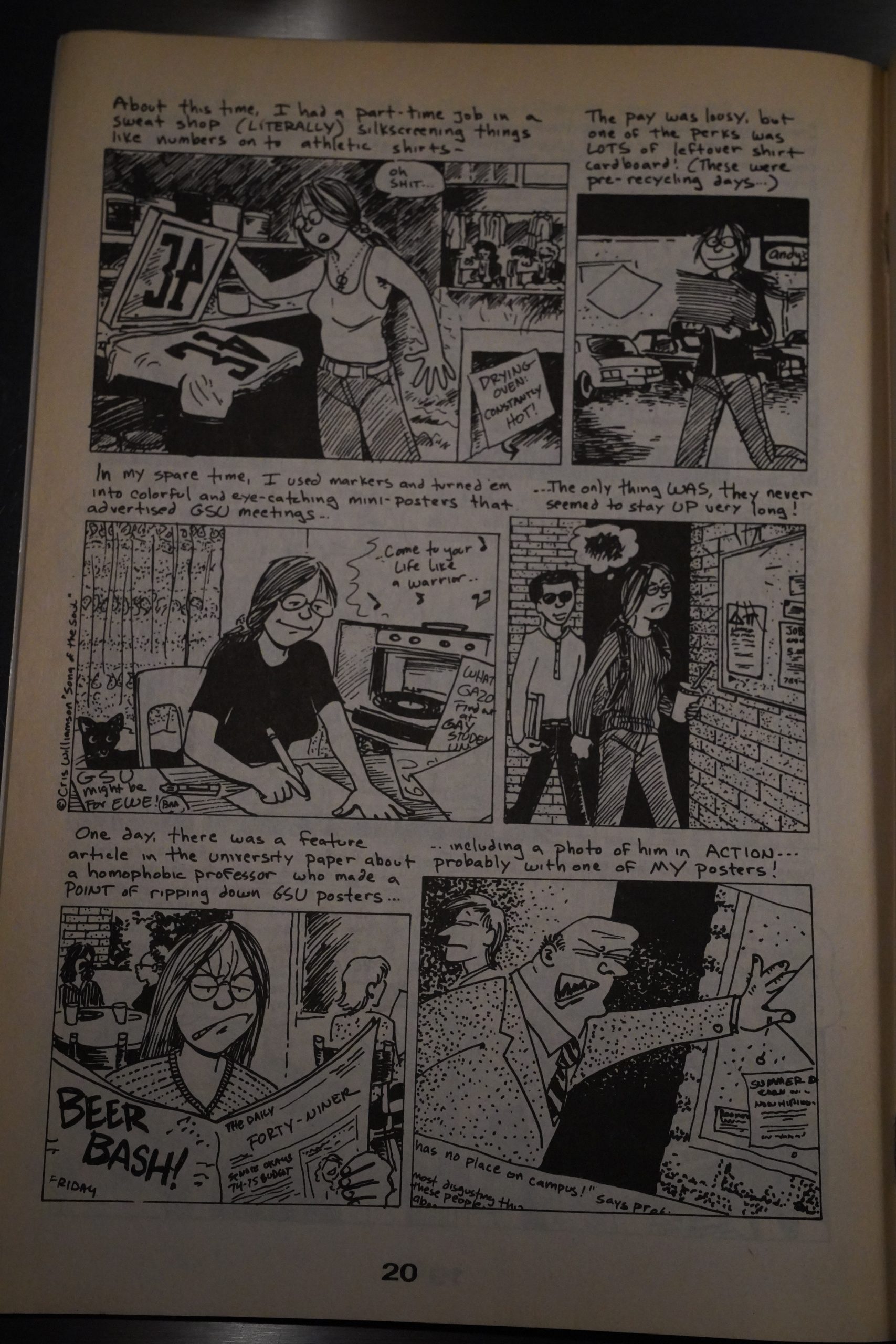

Cruse had focused mostly on professionals for the first couple of issues, but you start seeing less traditional pieces in the third. Cheela Smith here.

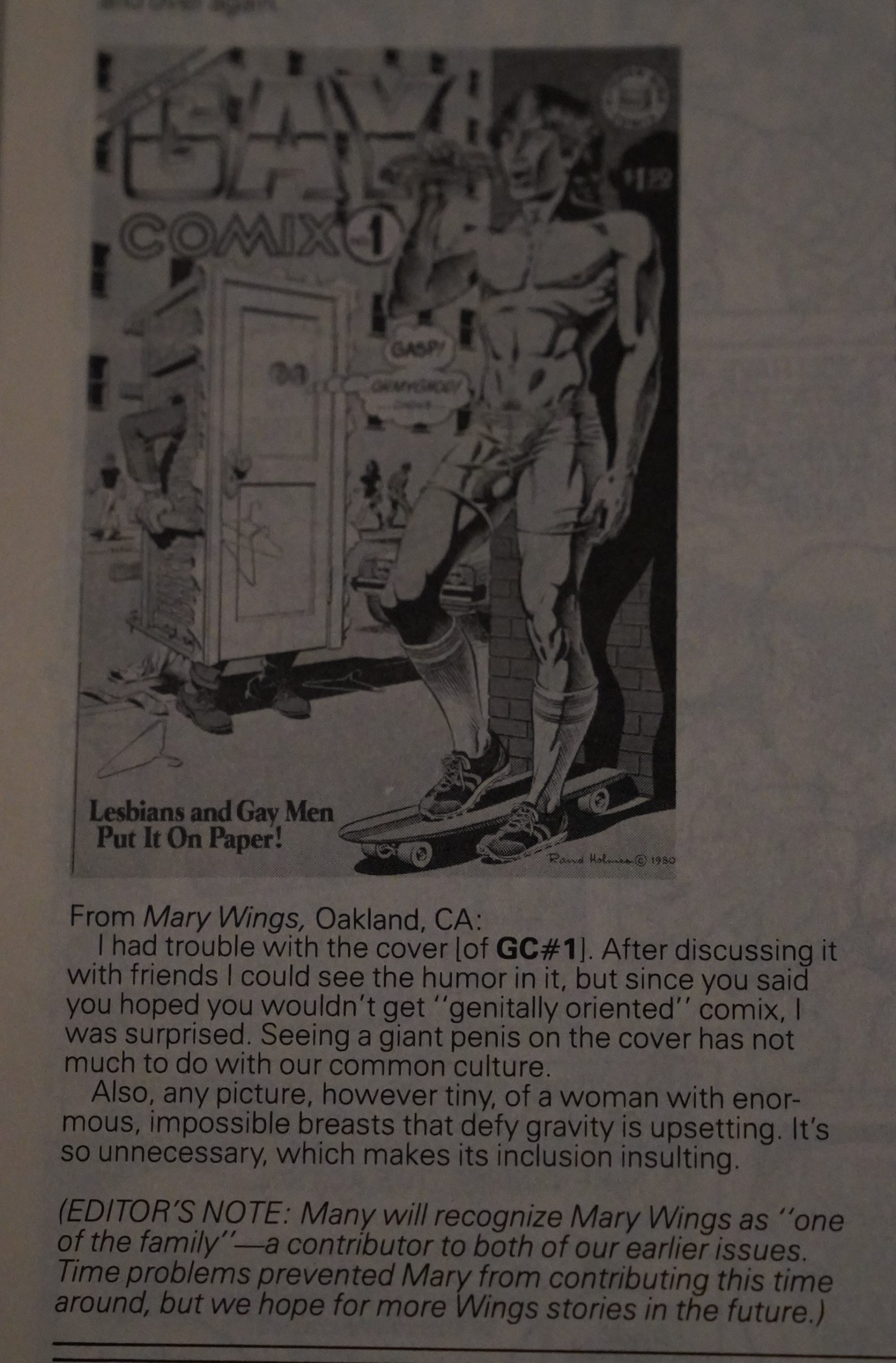

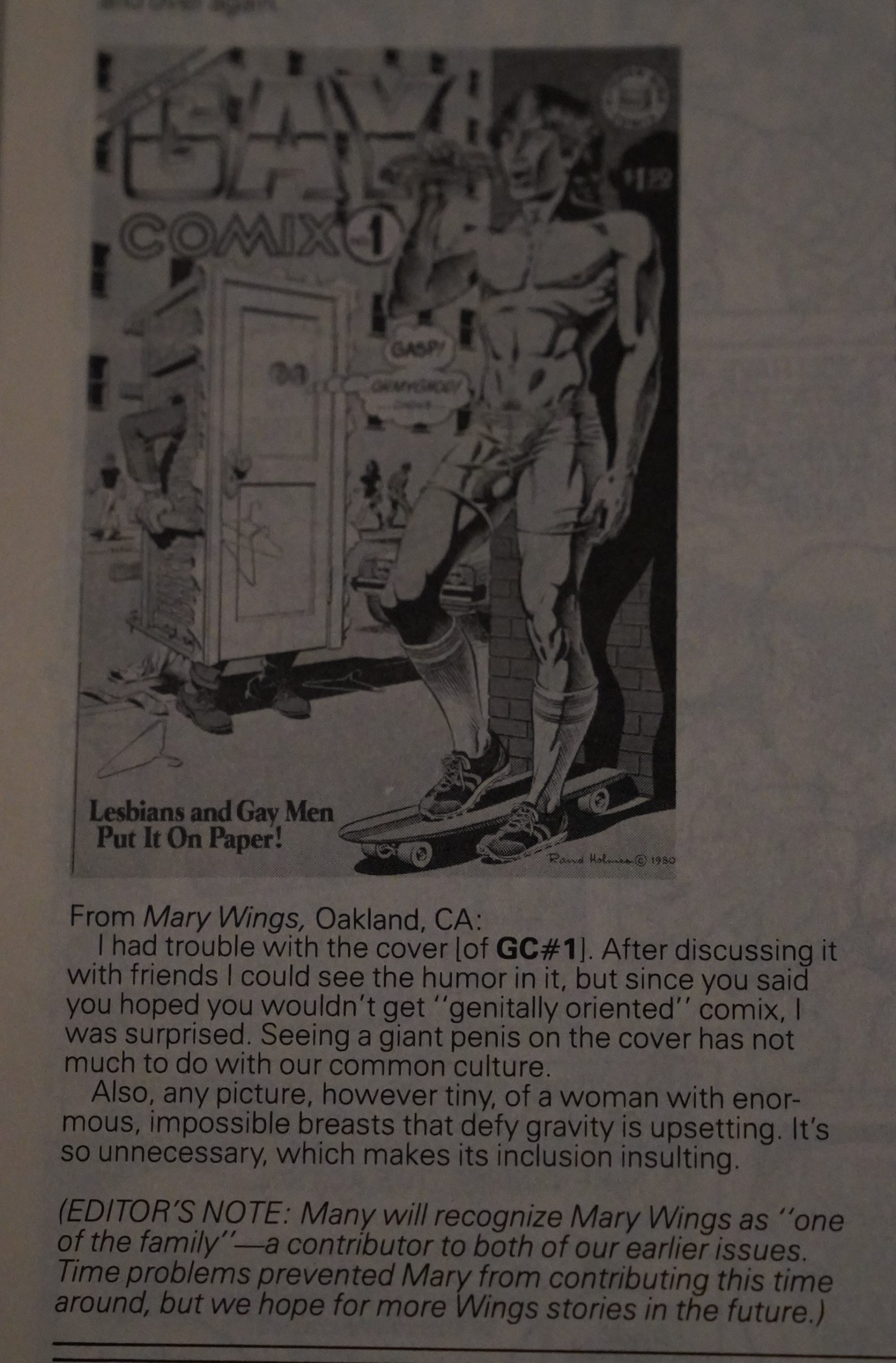

Aha. Cruse had asked for comics that weren’t “genitally oriented”? Mary Wings didn’t appreciate Rand Holmes’ iconic cover for the first issue.

Some of the other people contributing letters note that they think the contents are a bit heavy and negative, overall. Which I think is a fair critique…

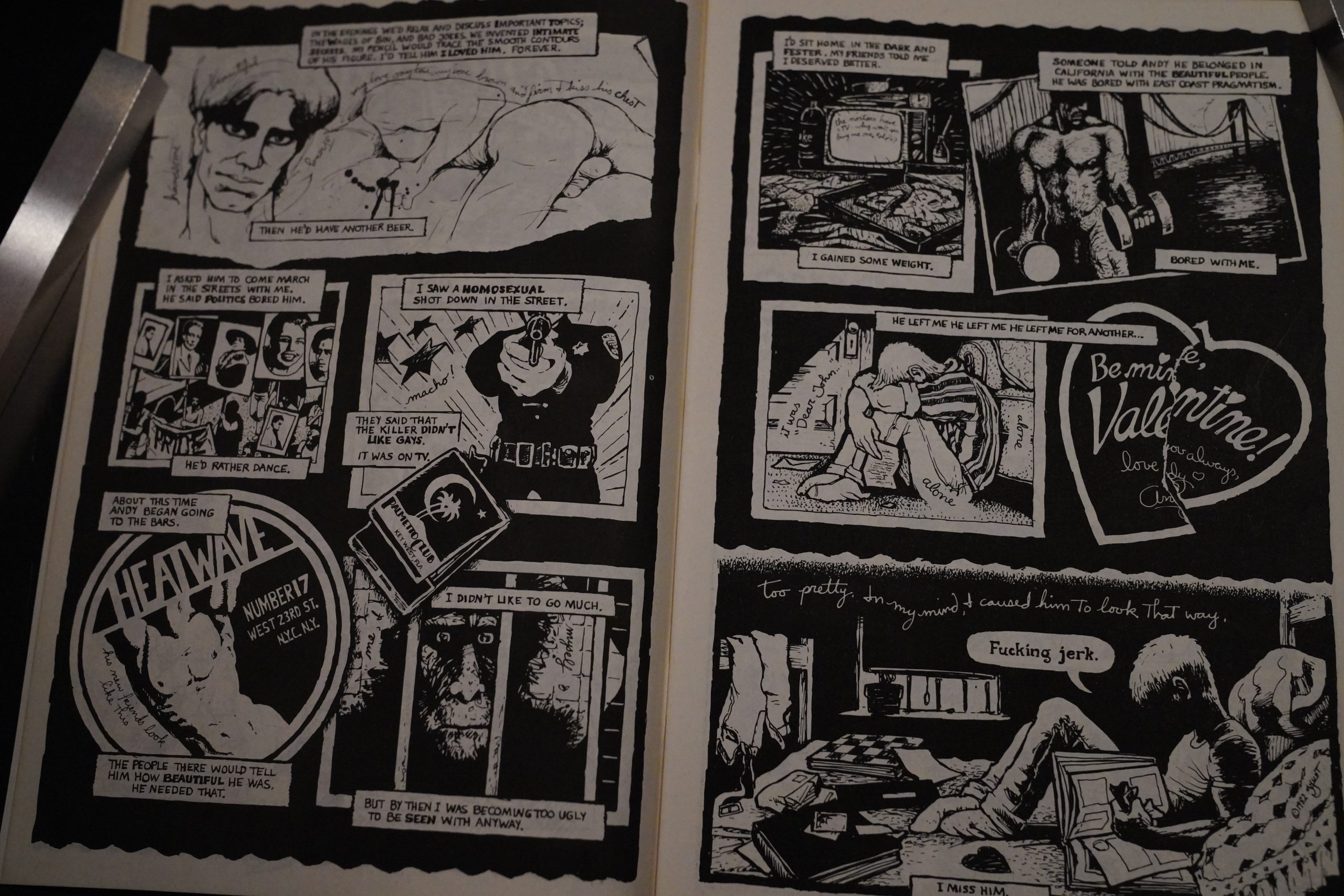

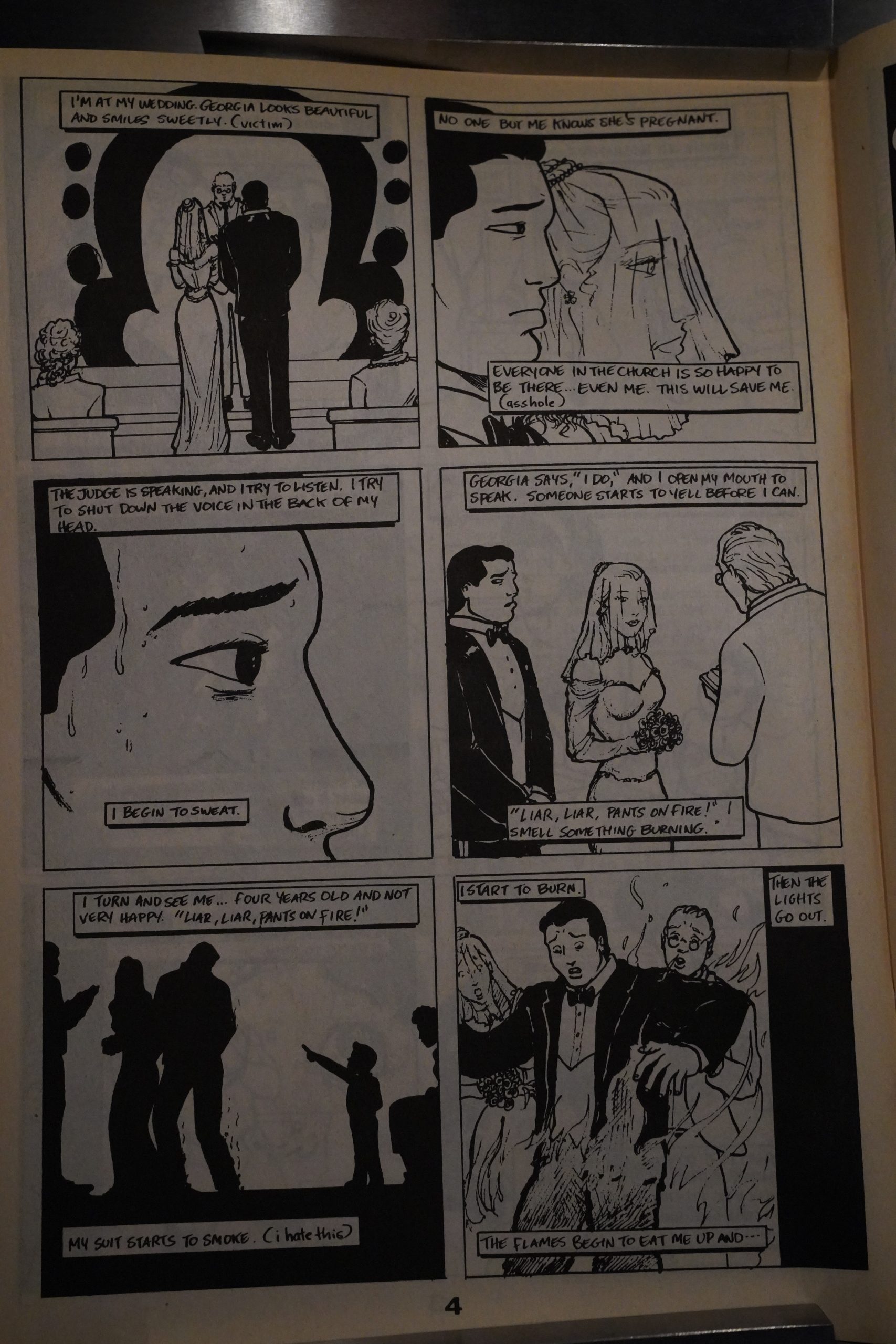

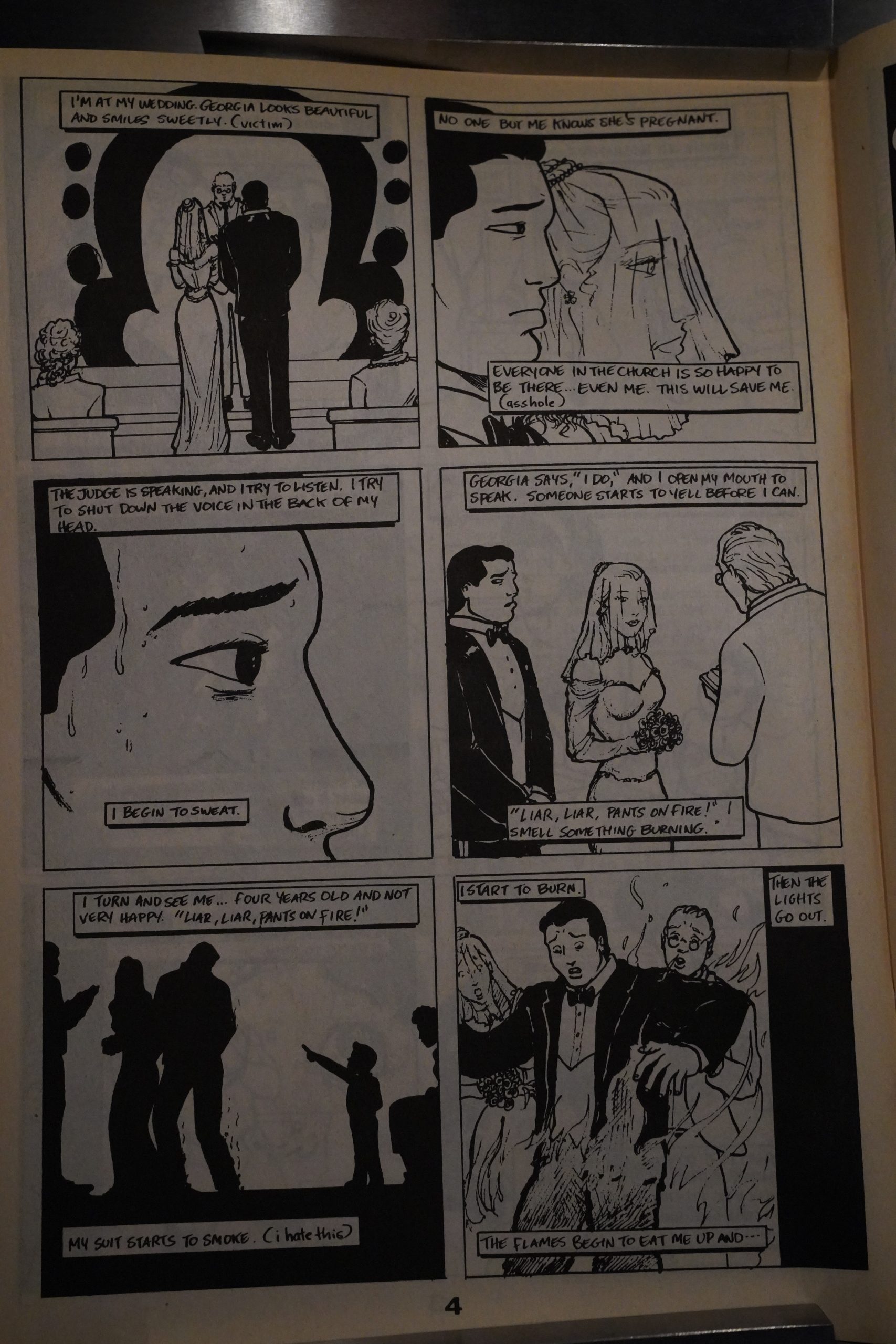

So the fourth issue starts with a really depressing little thing. Perhaps Cruse was just being contrarian. (And I don’t know who made this — it doesn’t seem to be signed, and as usual with Kitchen anthologies, there’s no list of contributors anywhere.)

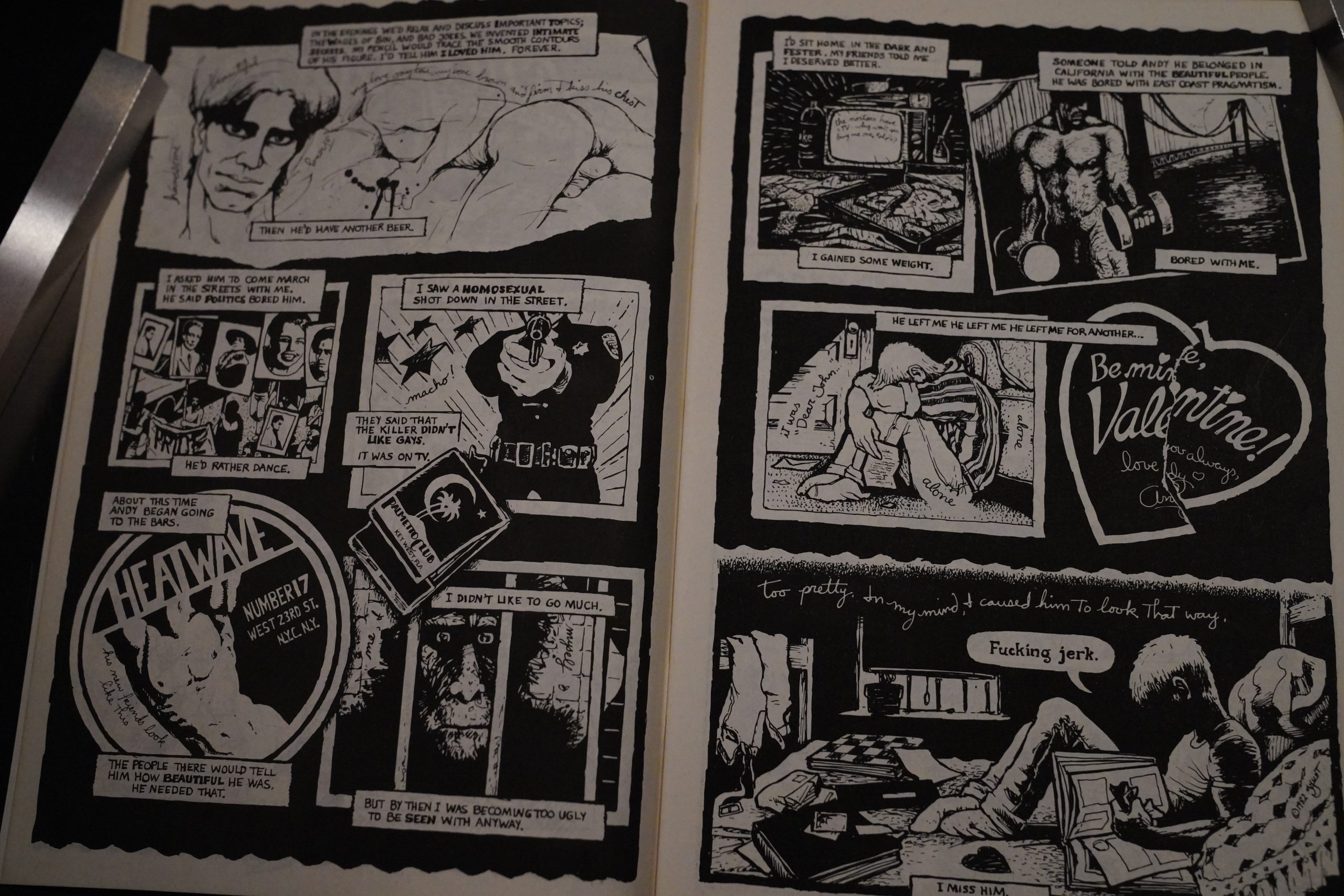

Joe Sinardi gets depressing.

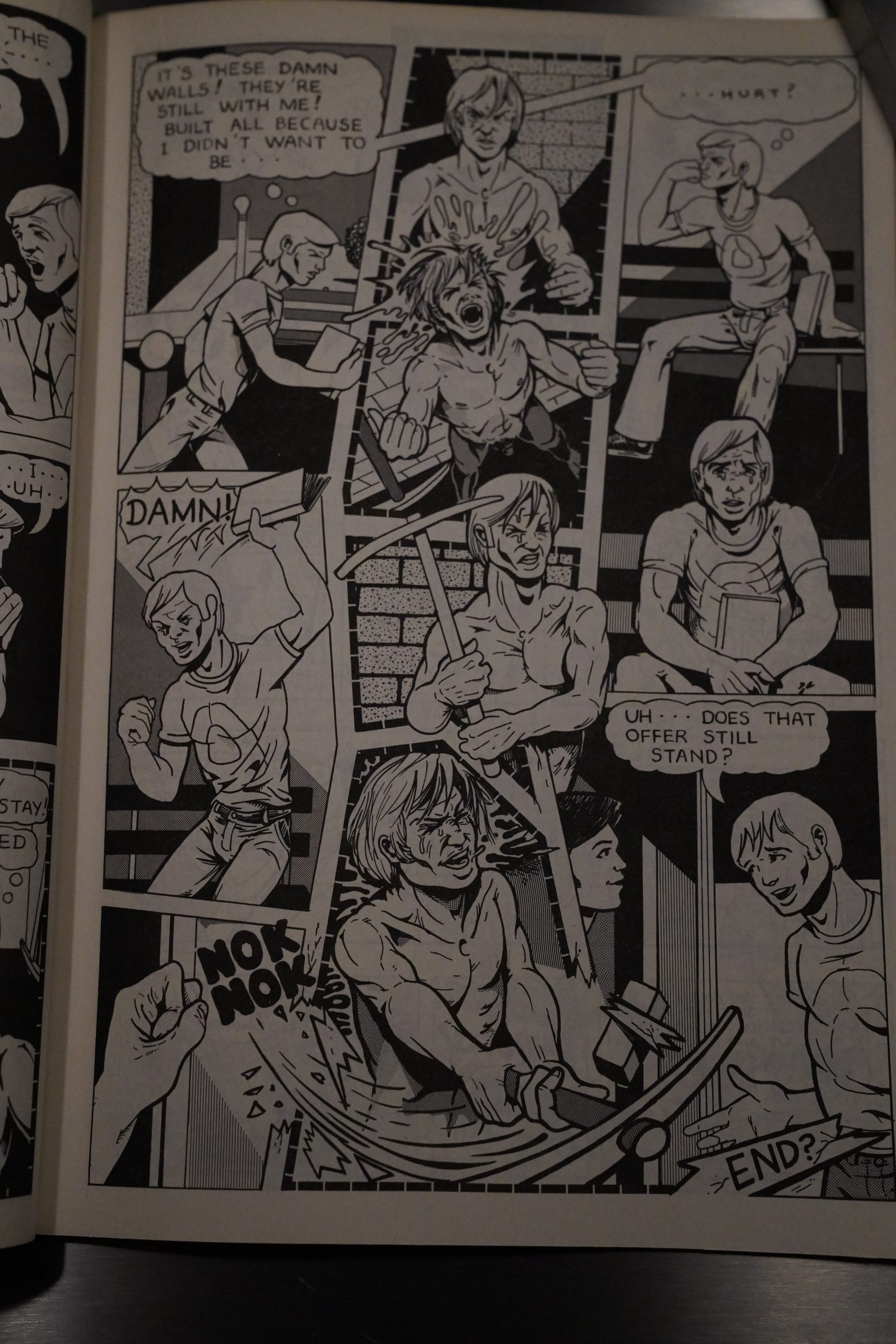

And again, I don’t know who did this? The art style looks familiar, but… It’s another strip of anguish and self doubt.

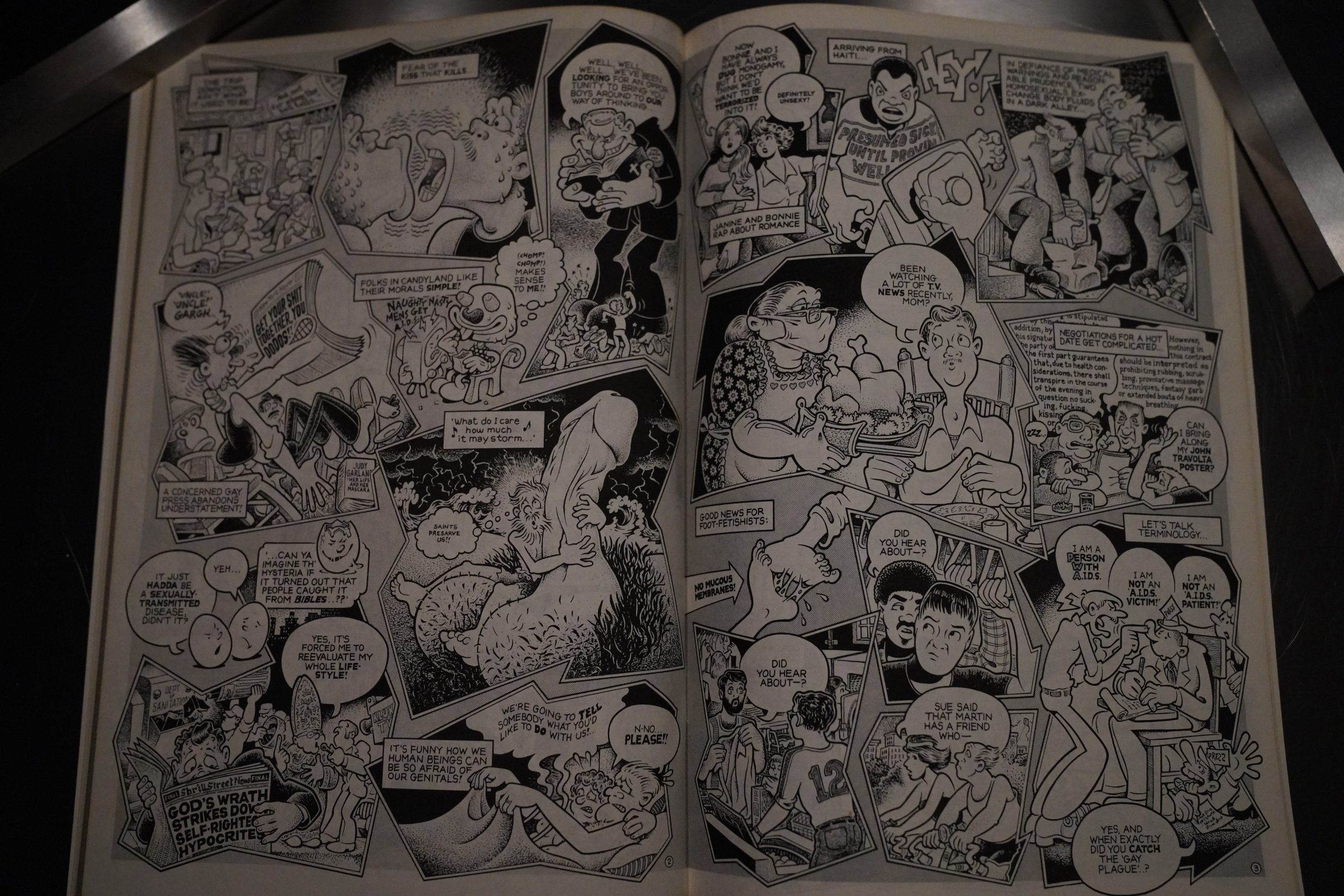

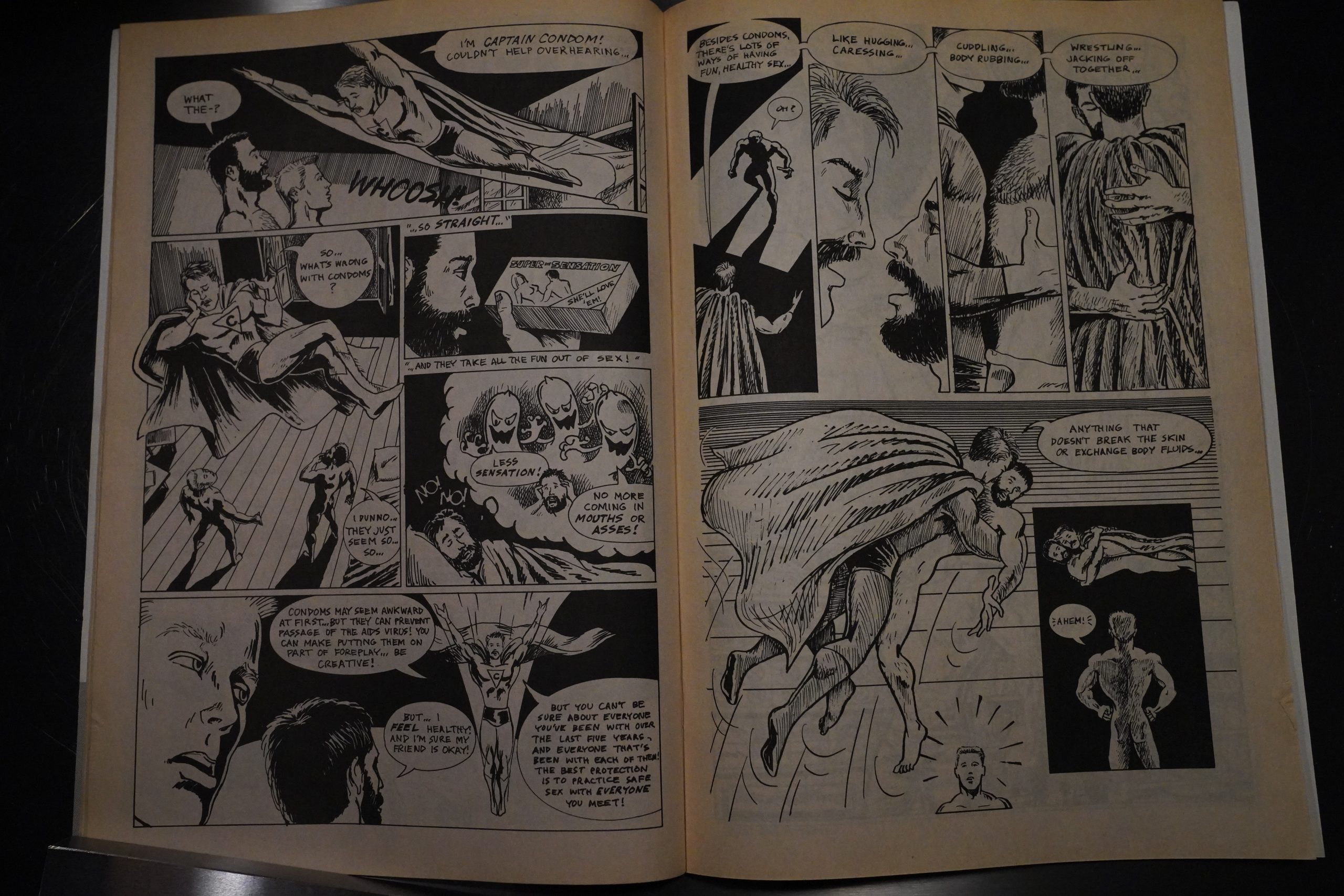

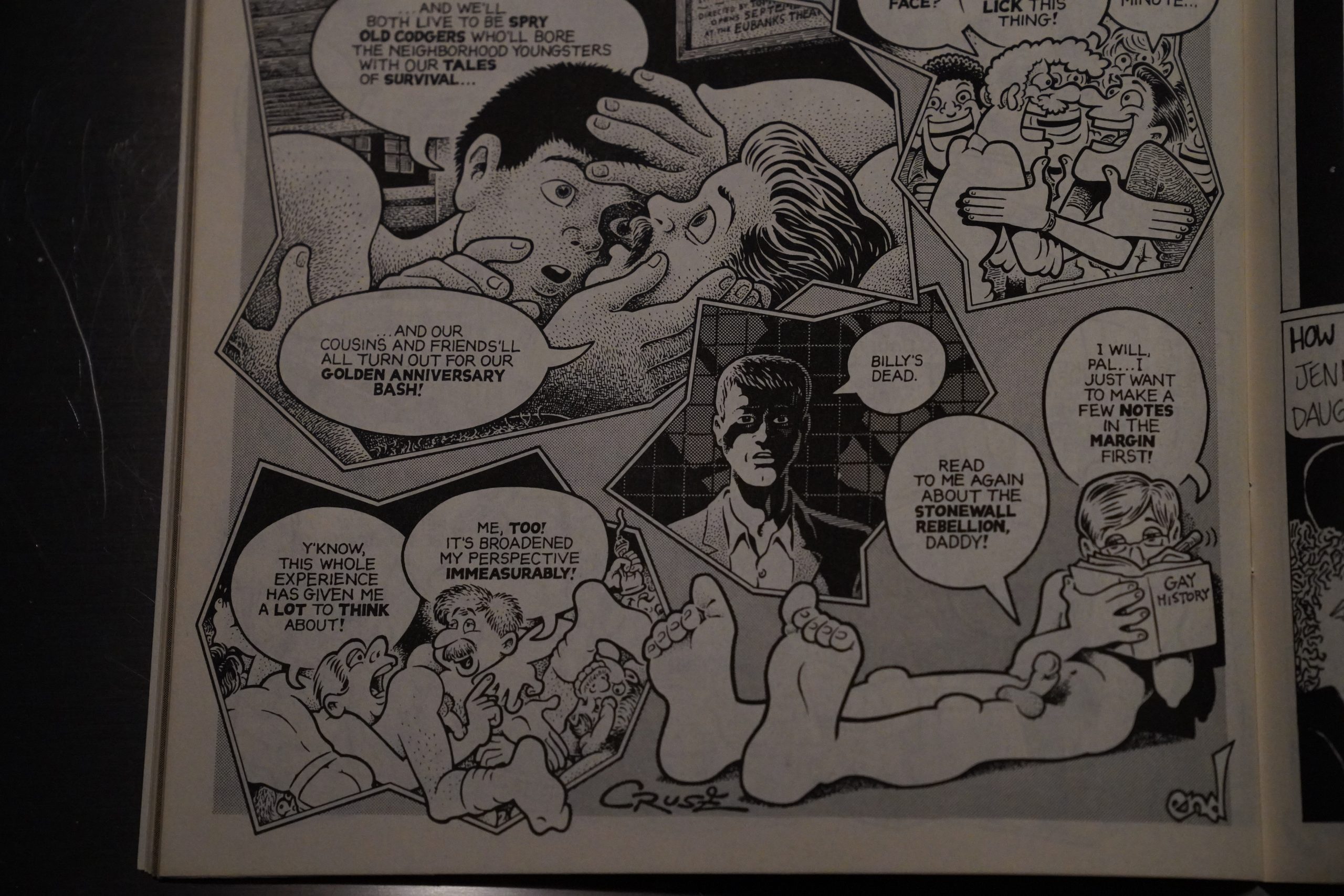

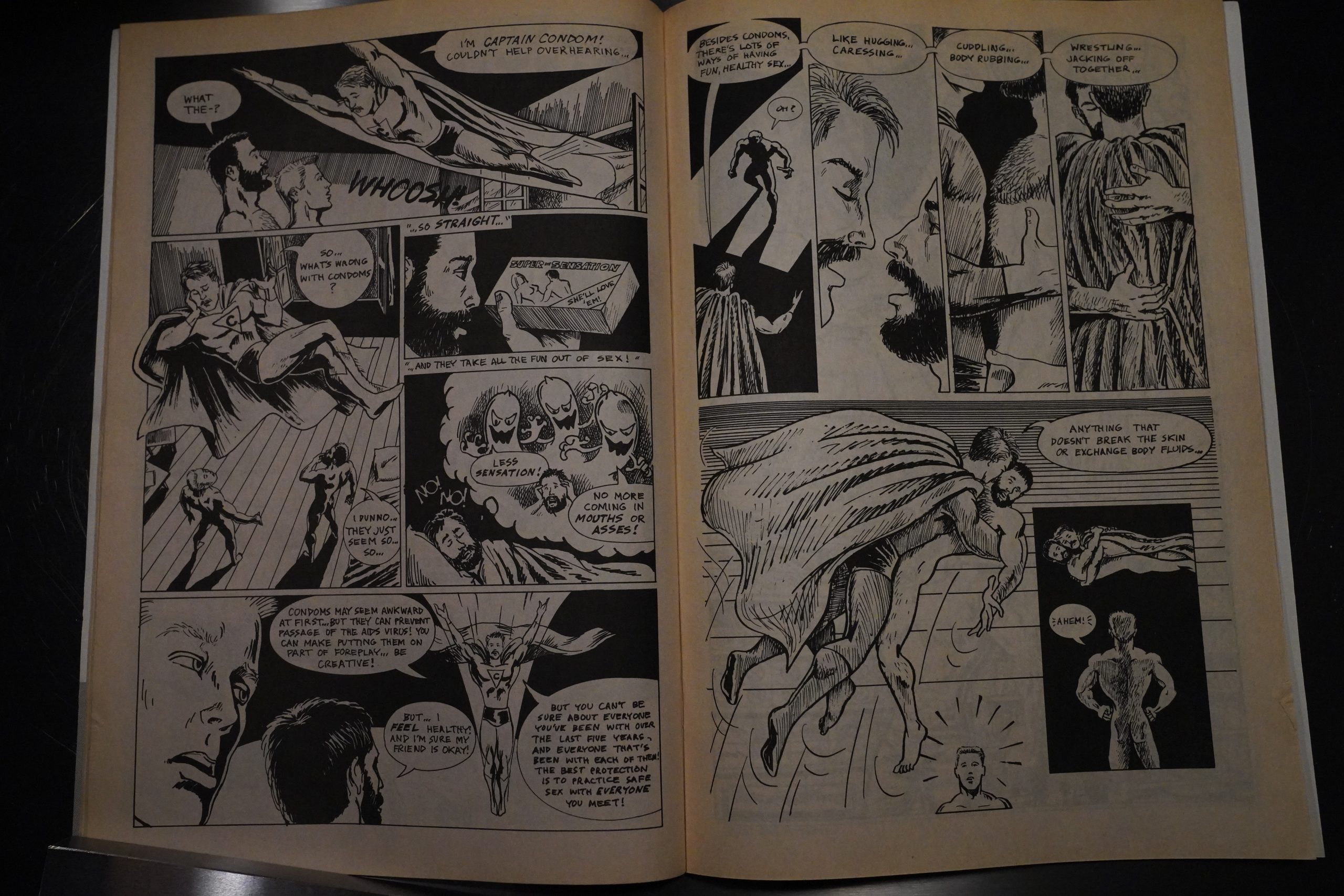

Finally, we have the Safe Sex story by Cruse, which is fantastic, and…

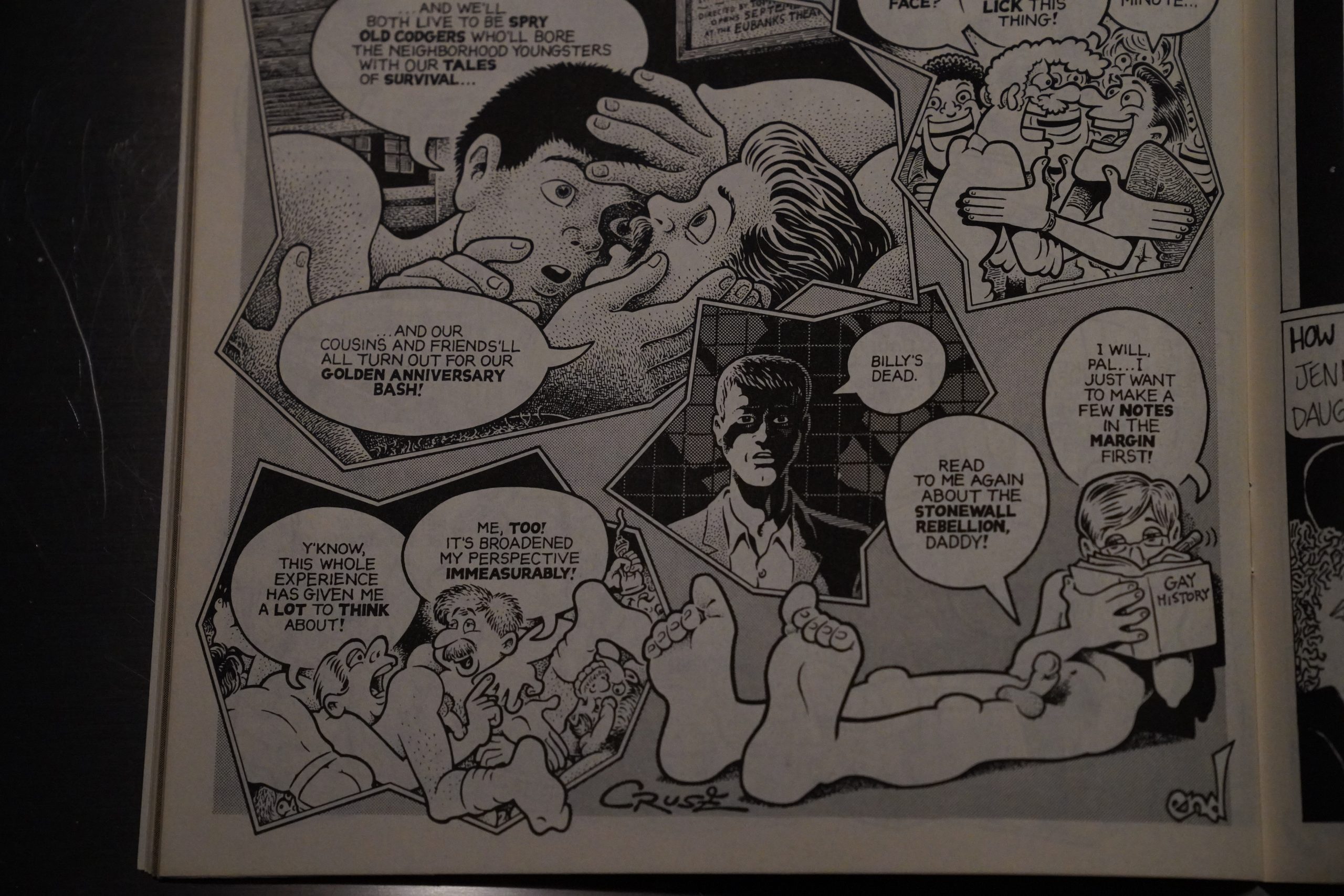

… in the next-to-last-ish “panel”, we’re told that Billy (from Billy Goes Out, published four years earlier) is dead.

*whew*

It’s a really depressing issue, but then again, AIDS had arrived.

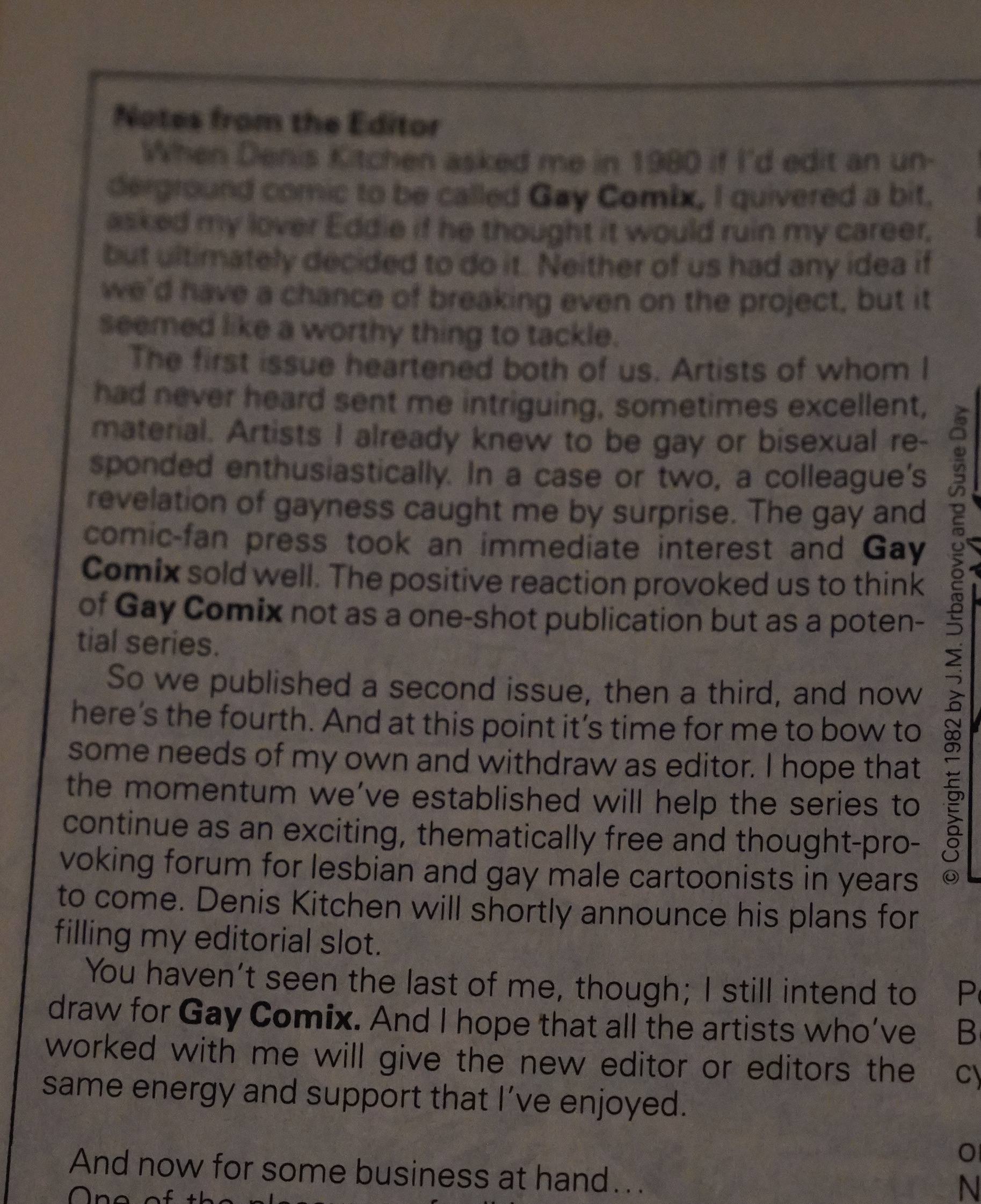

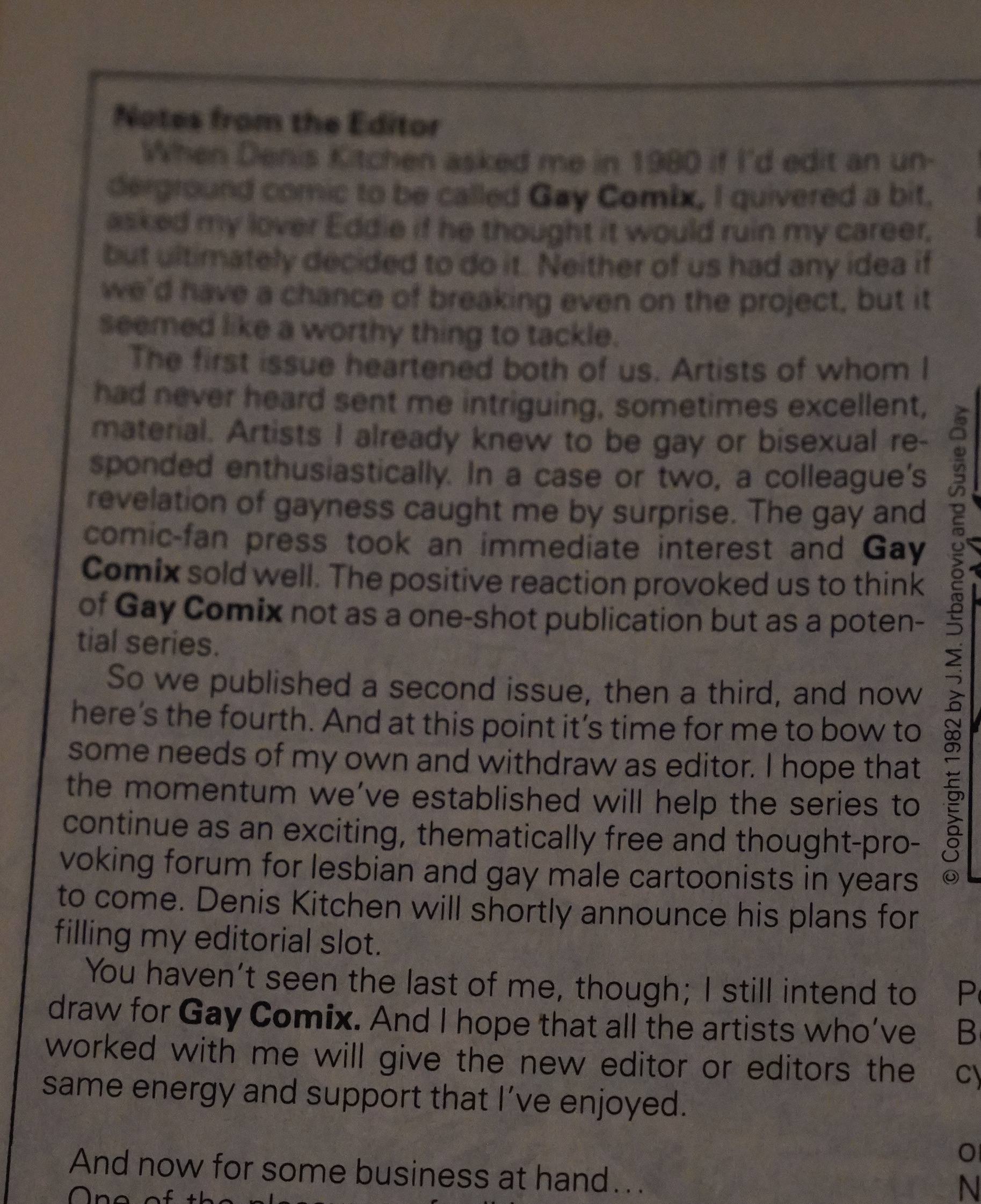

And Cruse announces that he’s relinquishing the editorial position, and also drops a few interesting titbits about the comics history: First of all, Denis Kitchen had the idea for the book, and asked Cruse to edit it. Which is kinda unusual for this sort of thing; it’s usually the editor that wants to publish something and then approaches a publisher. And secondly, it wasn’t originally intended as a continuing series, but sold so well that it became a series.

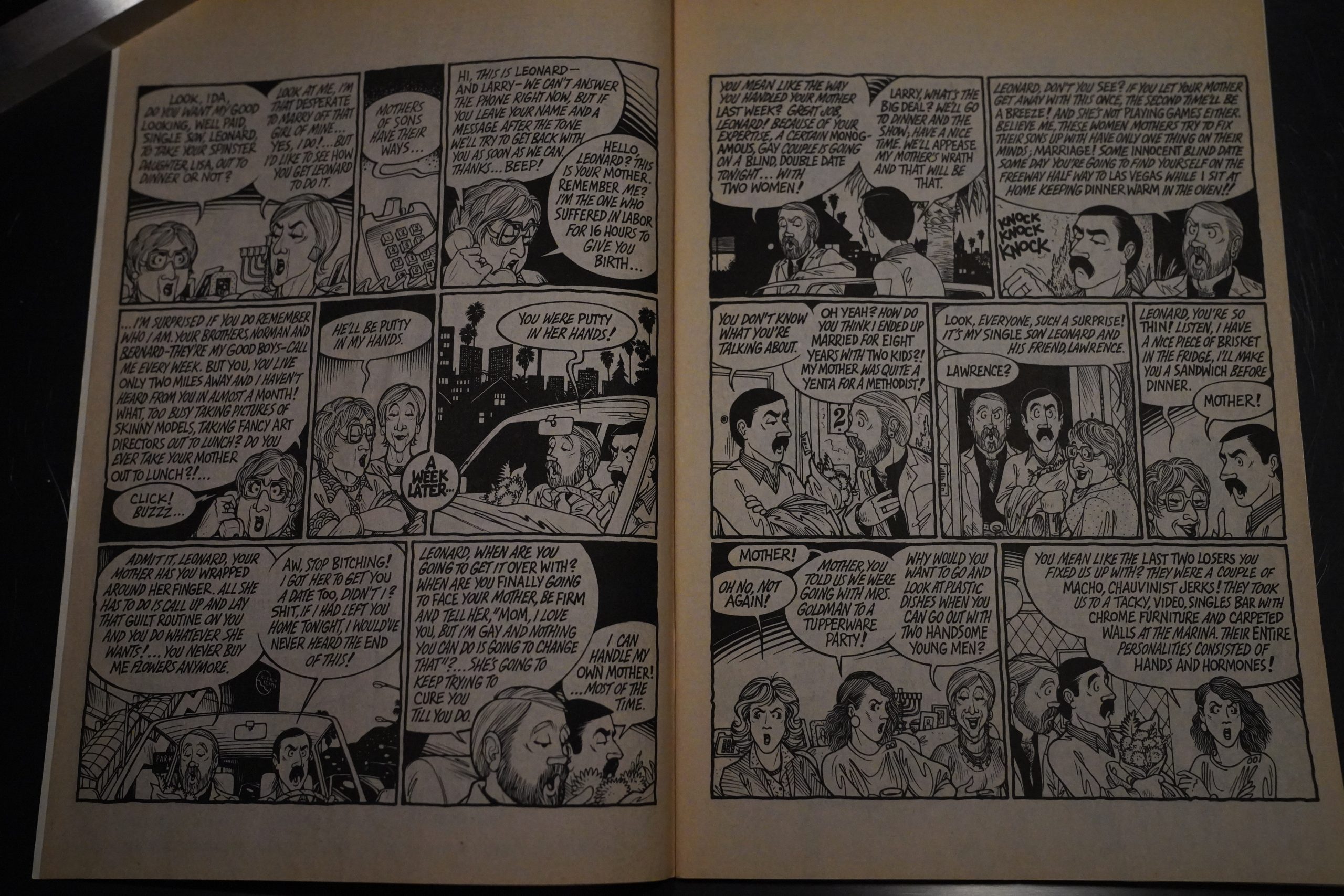

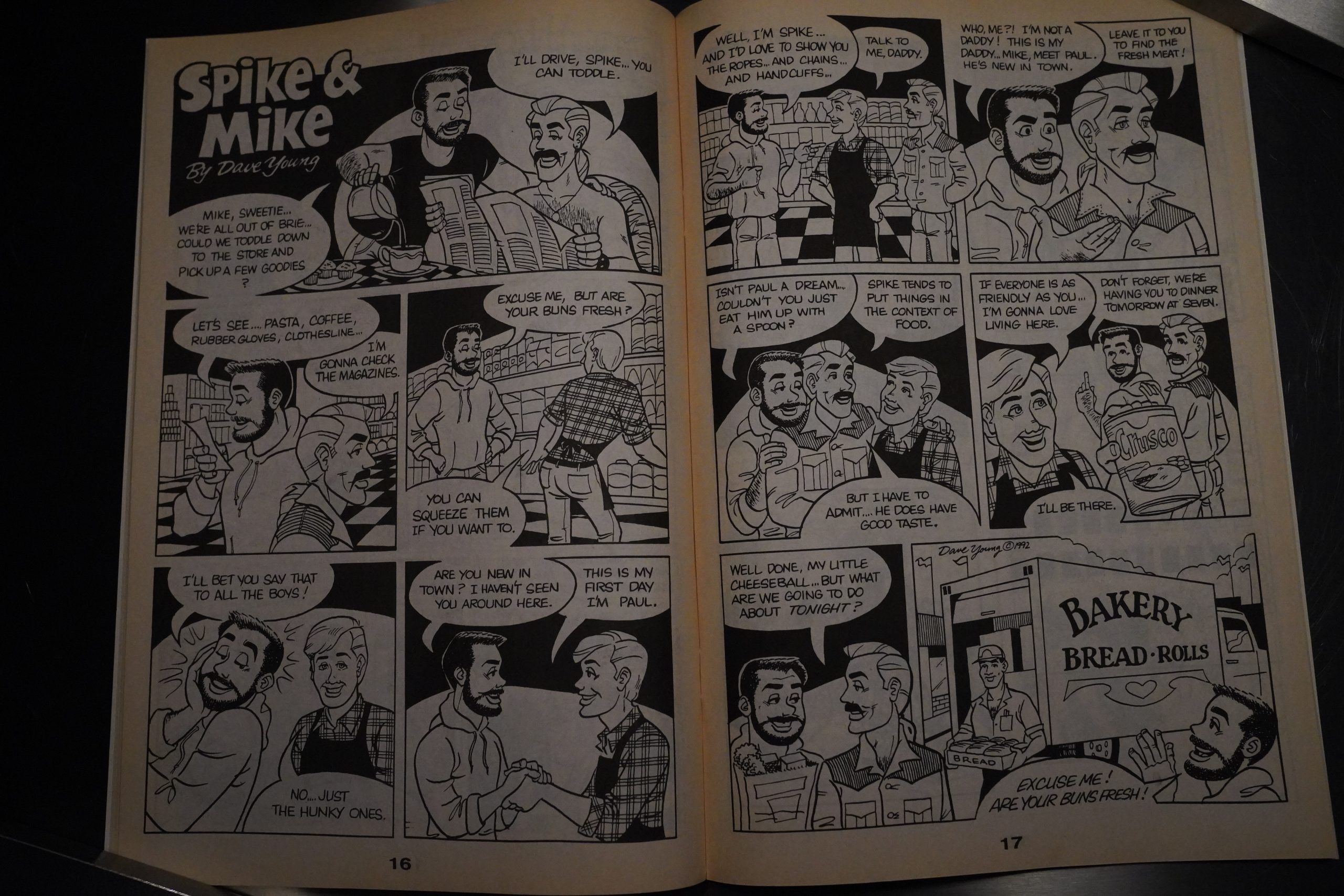

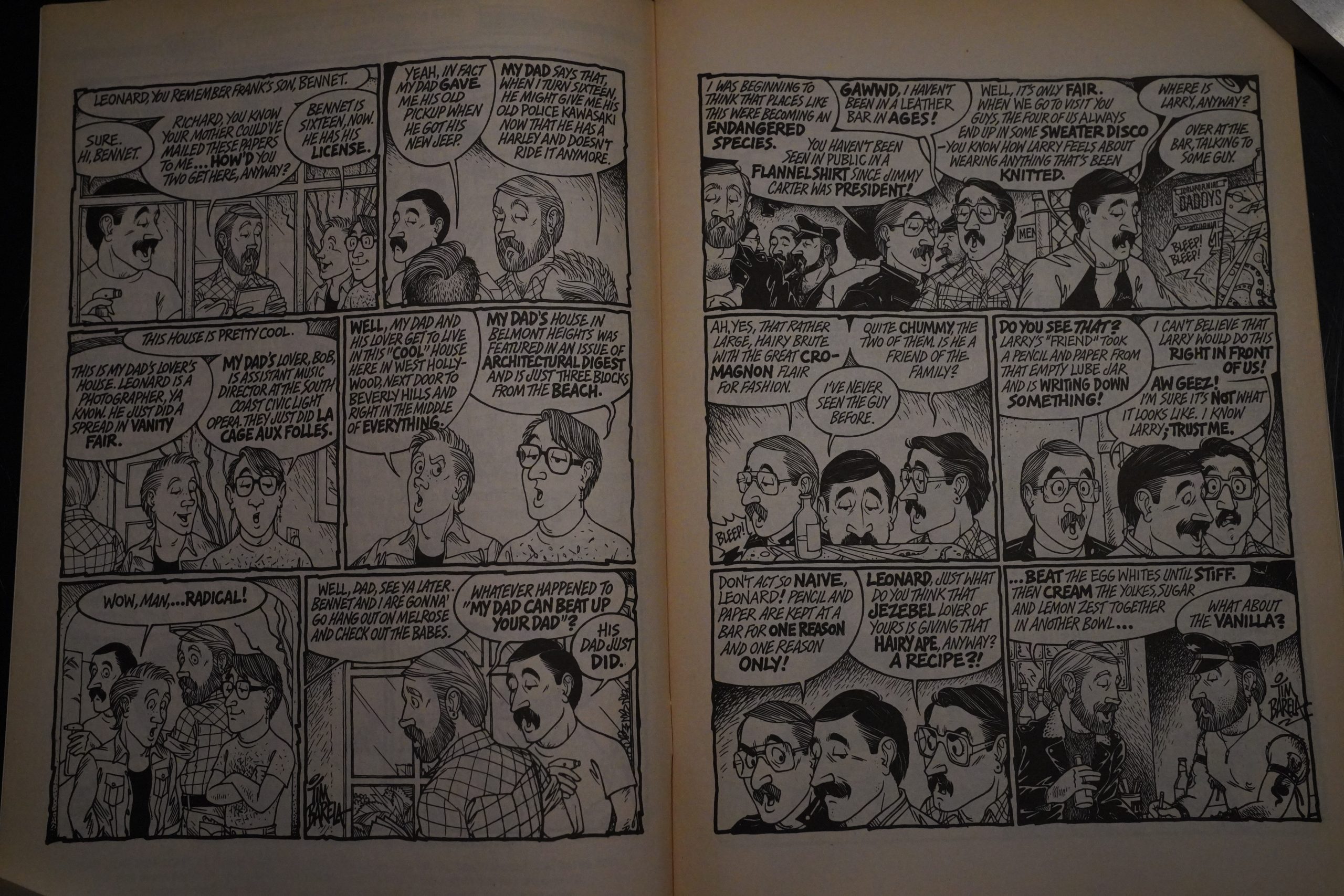

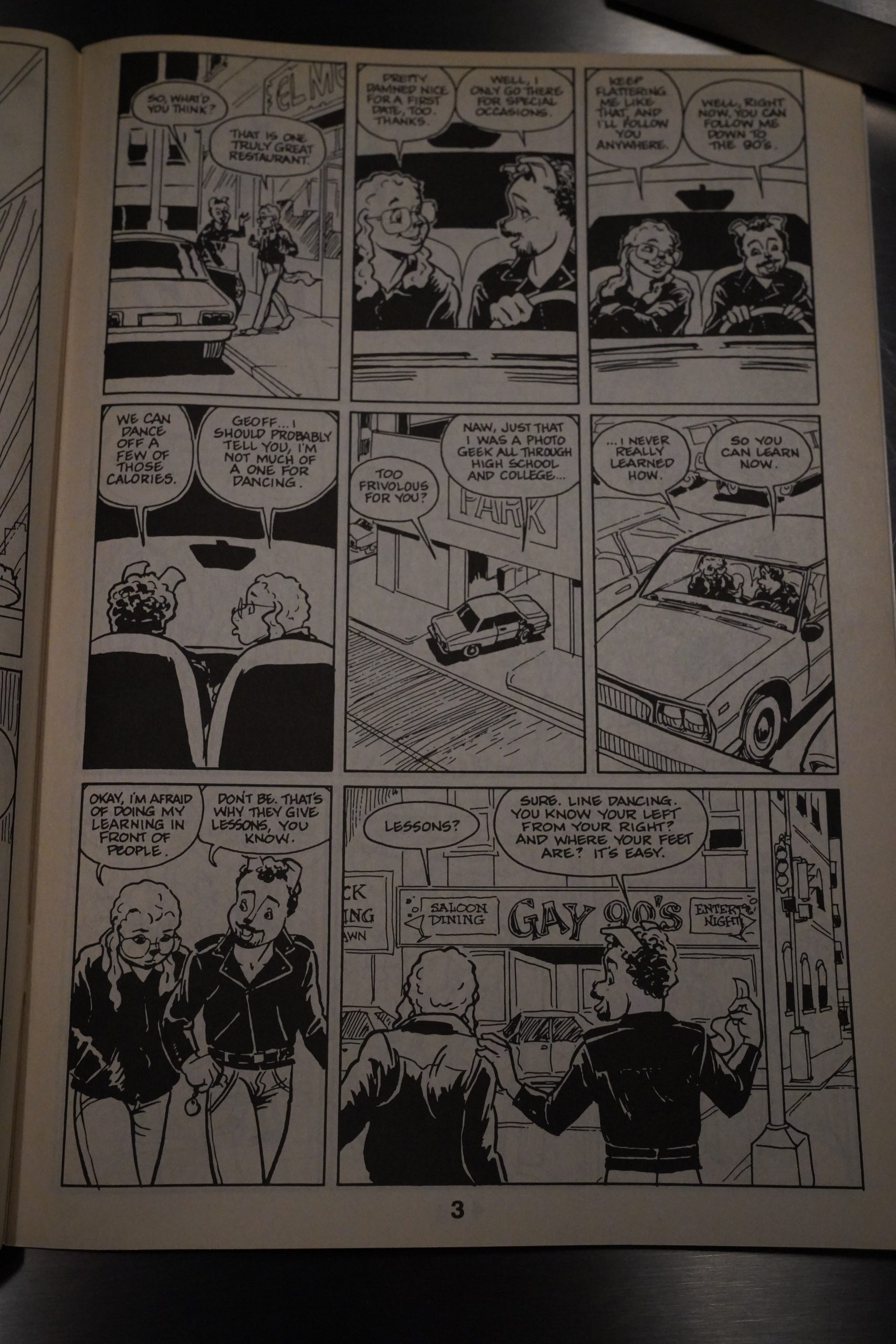

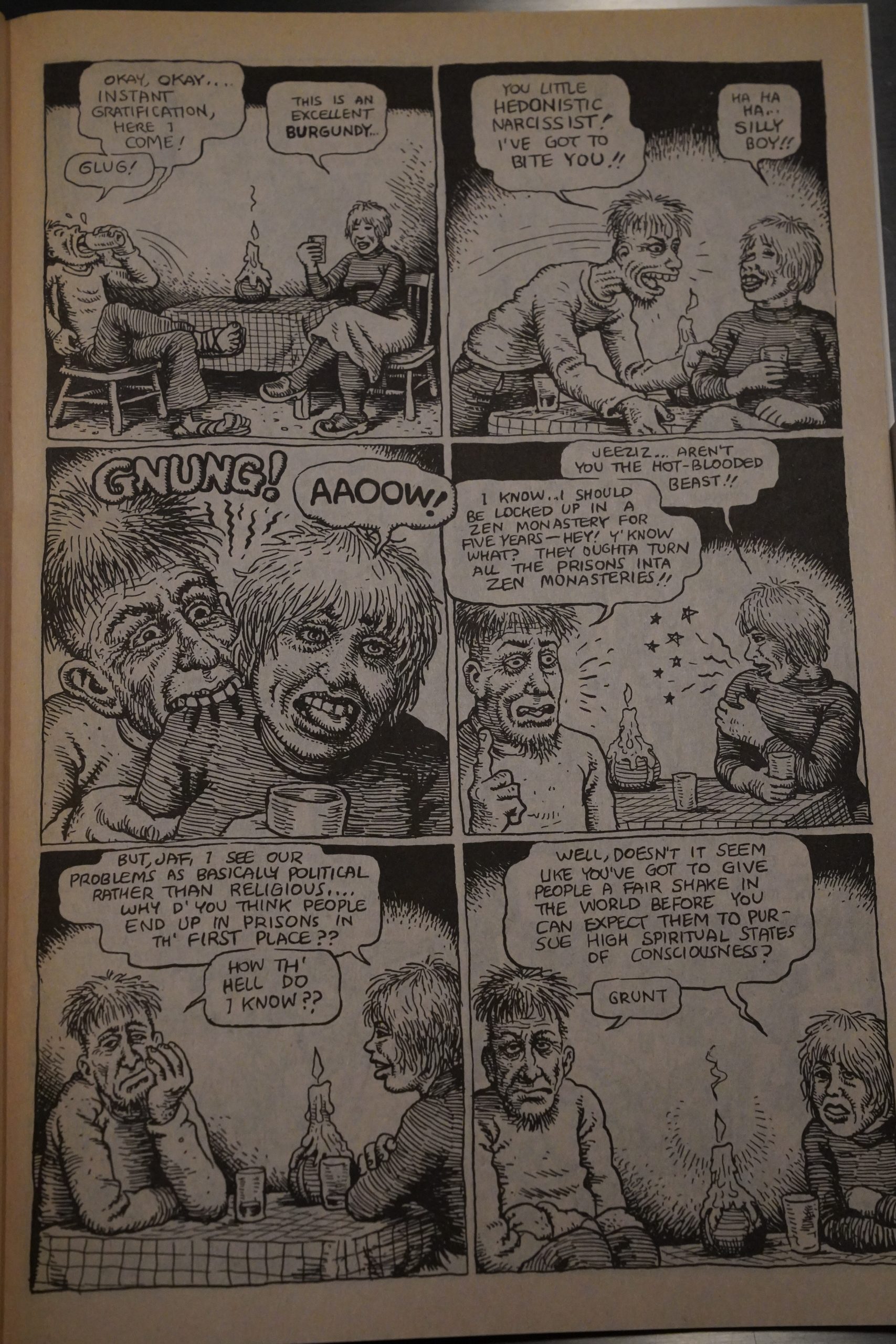

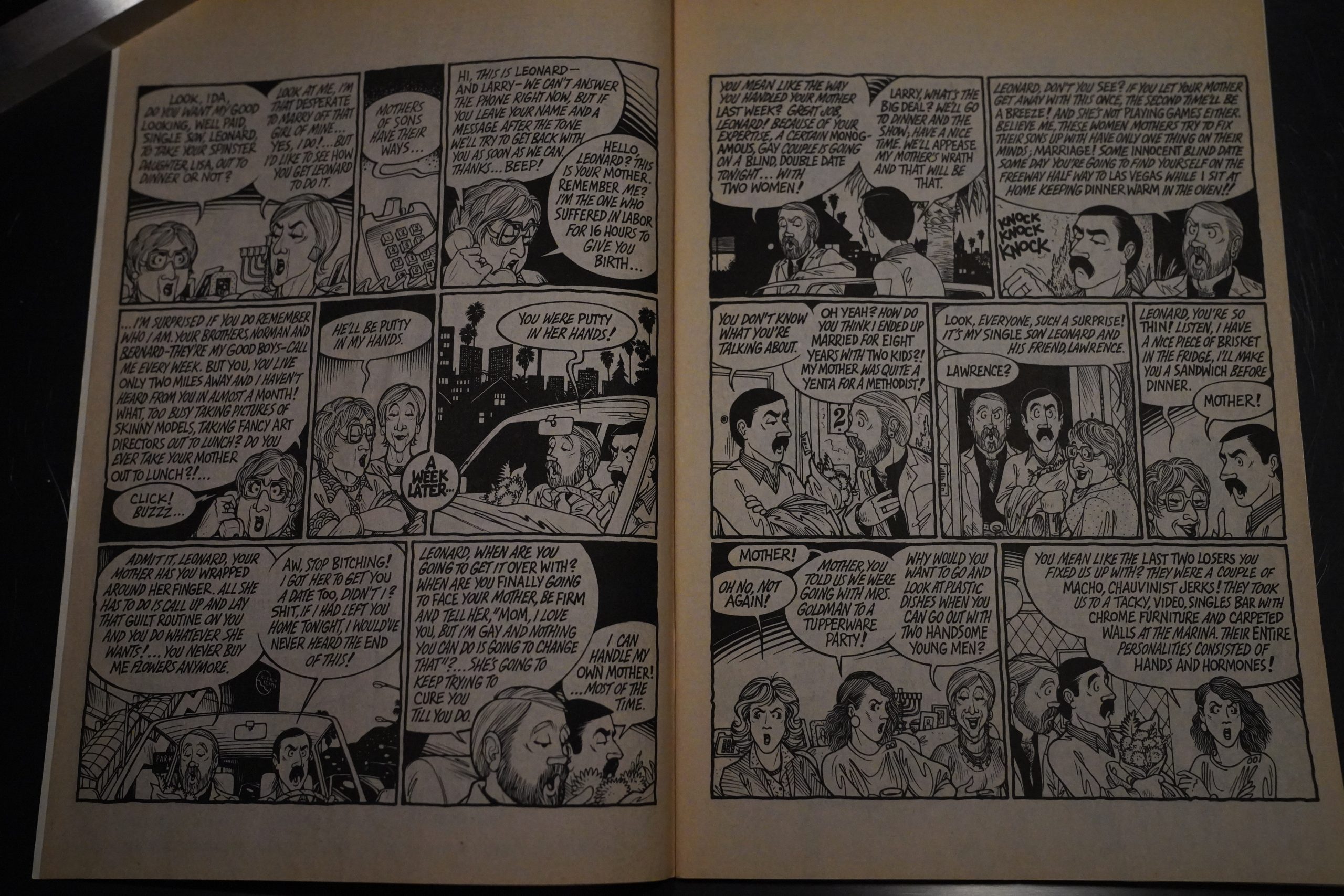

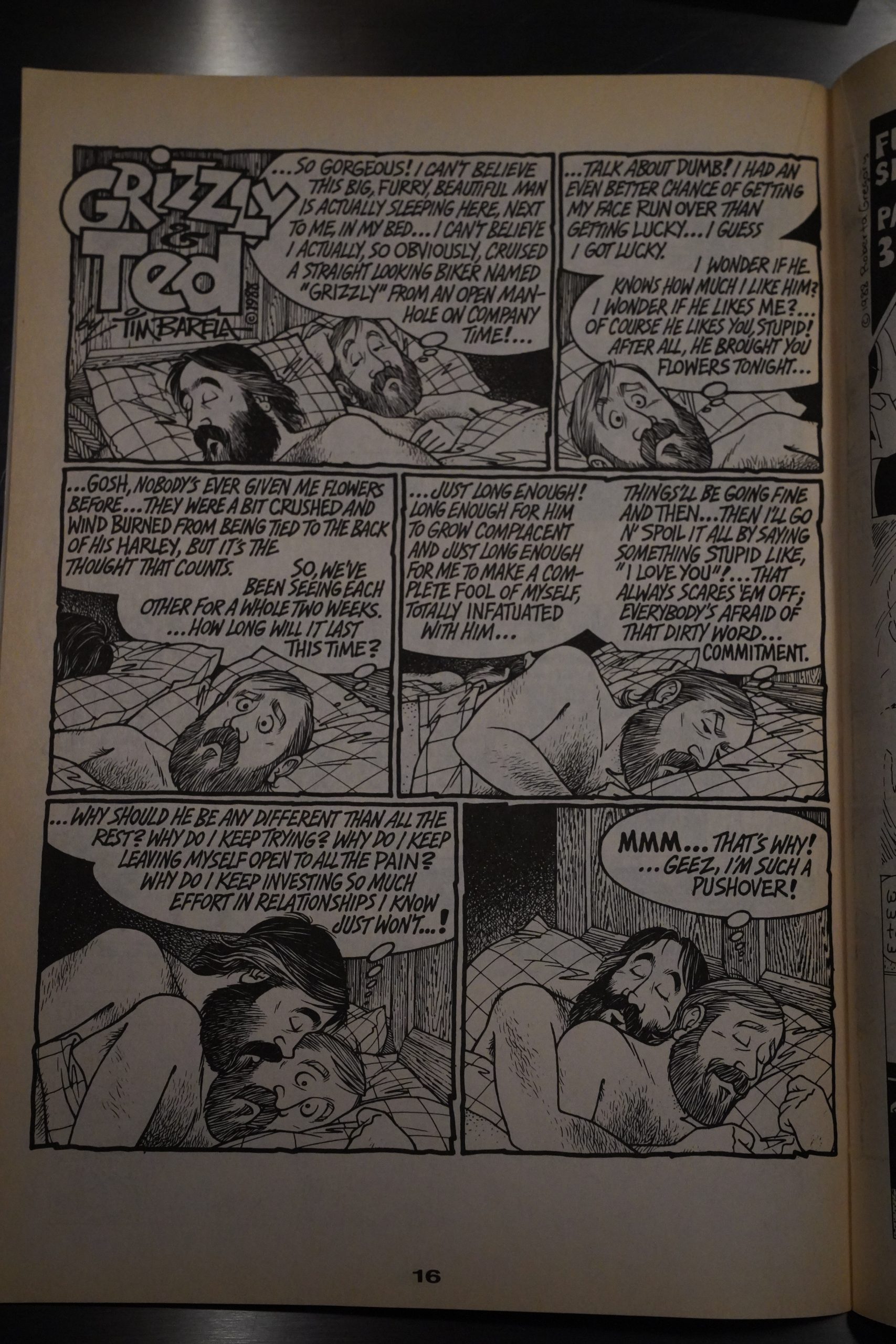

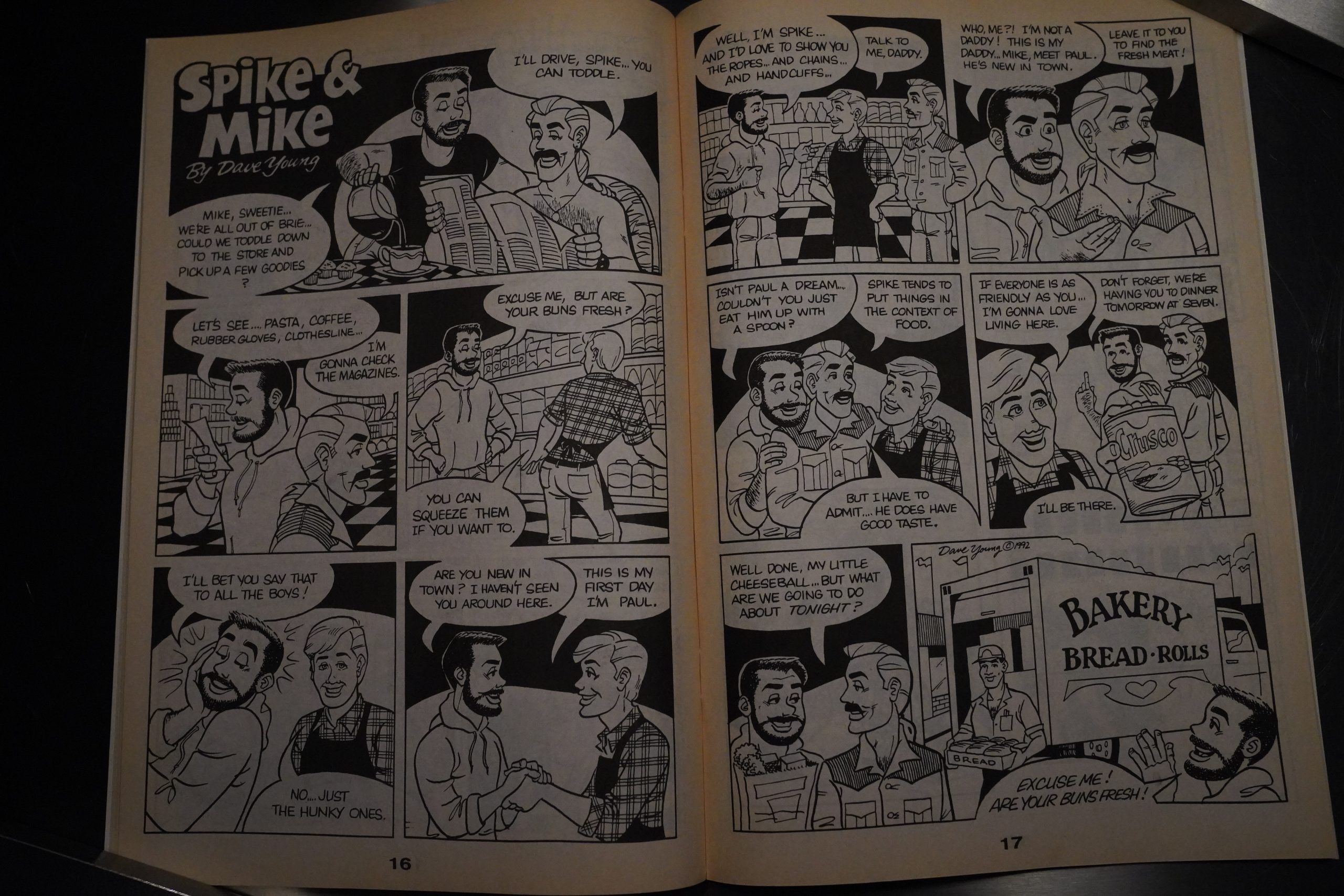

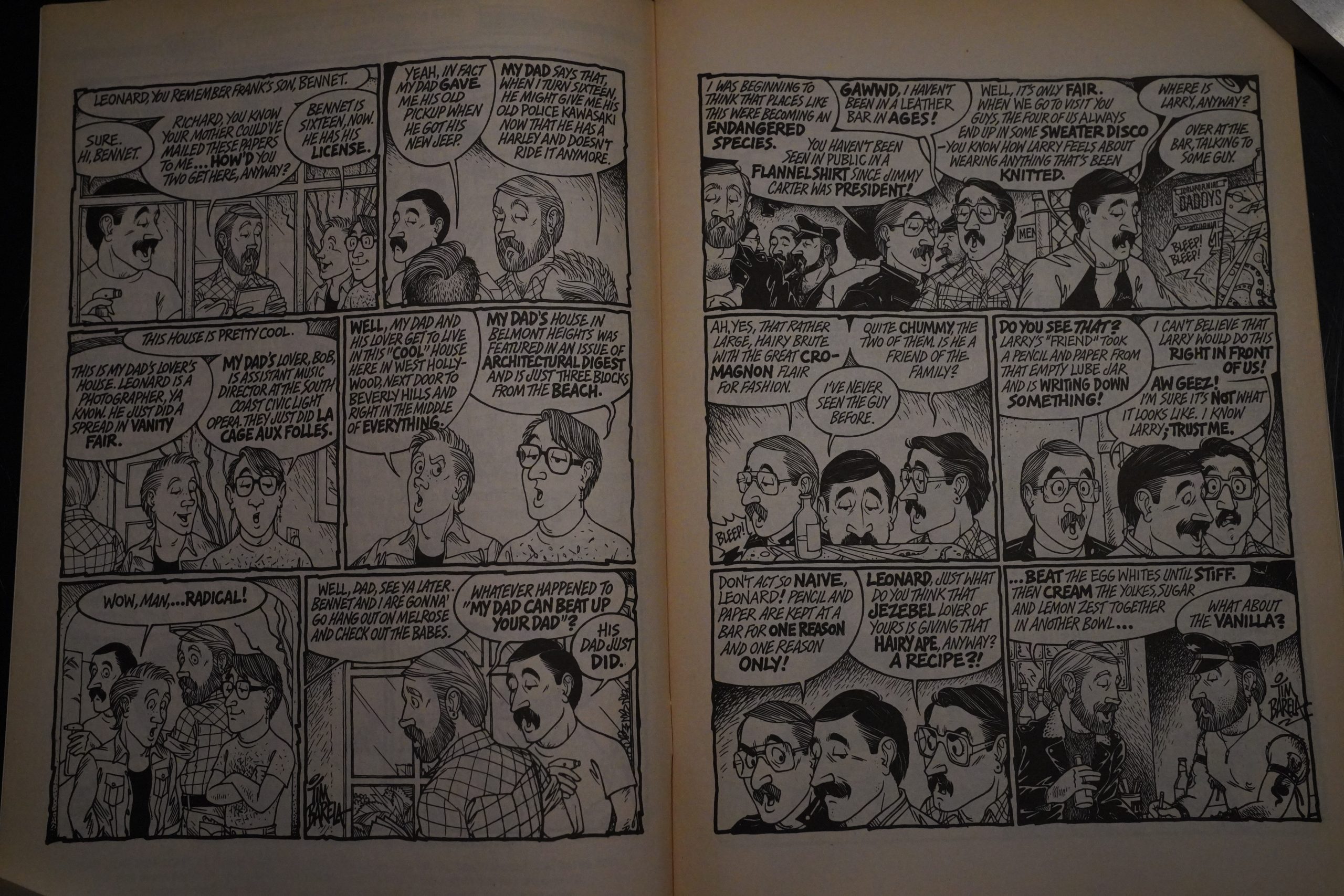

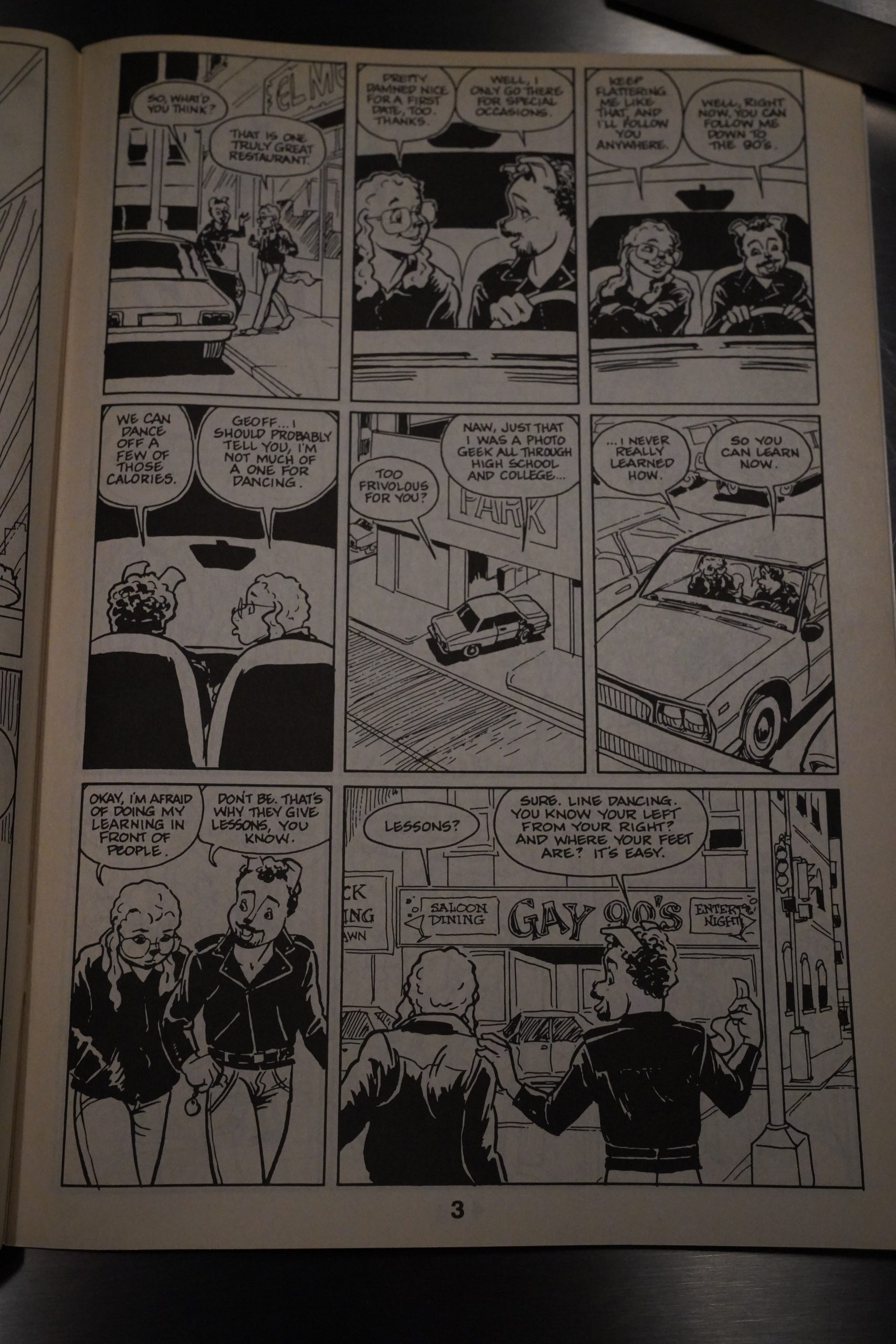

So with the fifth issue, Robert Triptow takes over as the editor, and the tenor of the book changes somewhat. We get stuff like Leonard & Larry by Tim Barella, which is basically a sitcom on paper. I like it, but dear lord the verbiage.

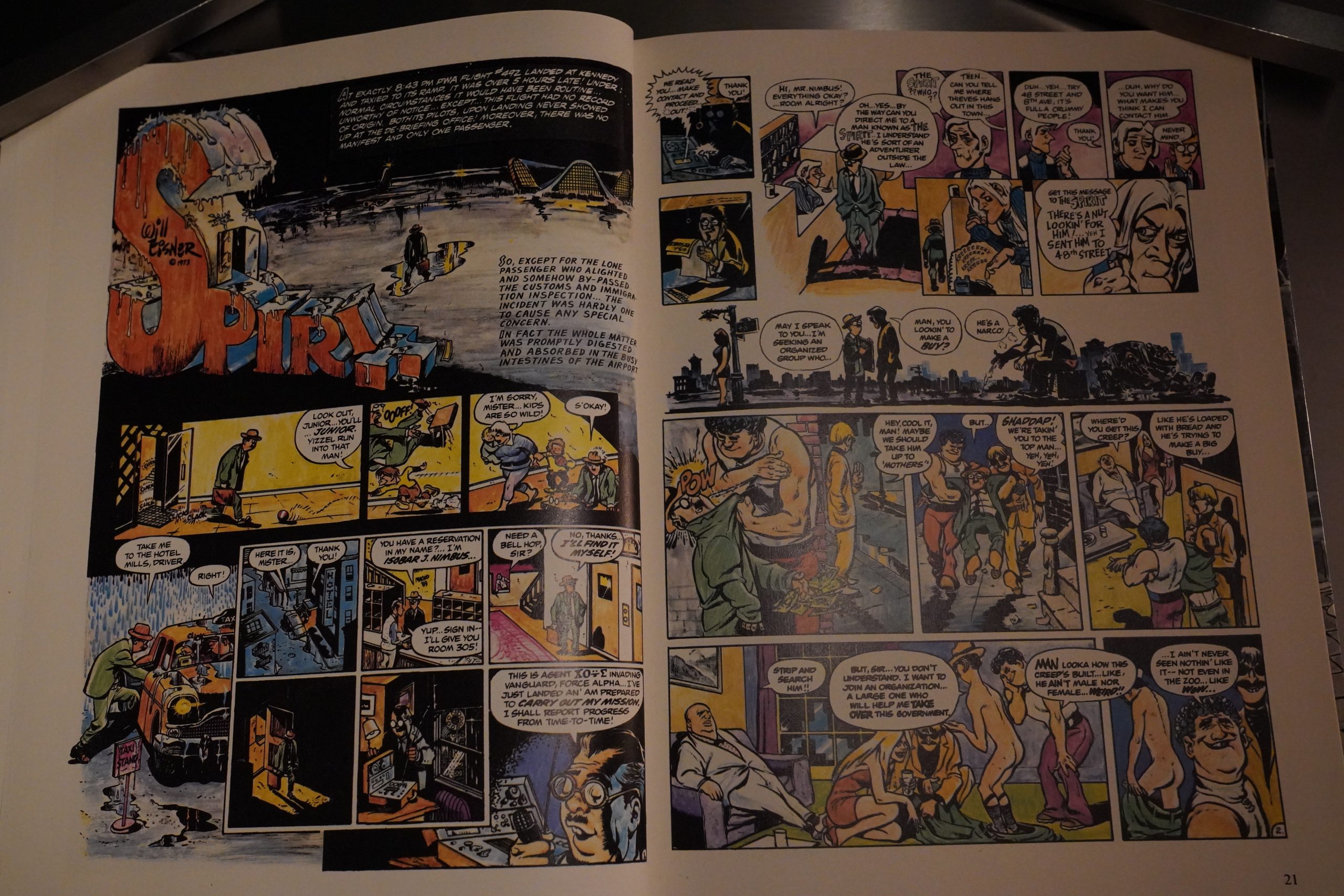

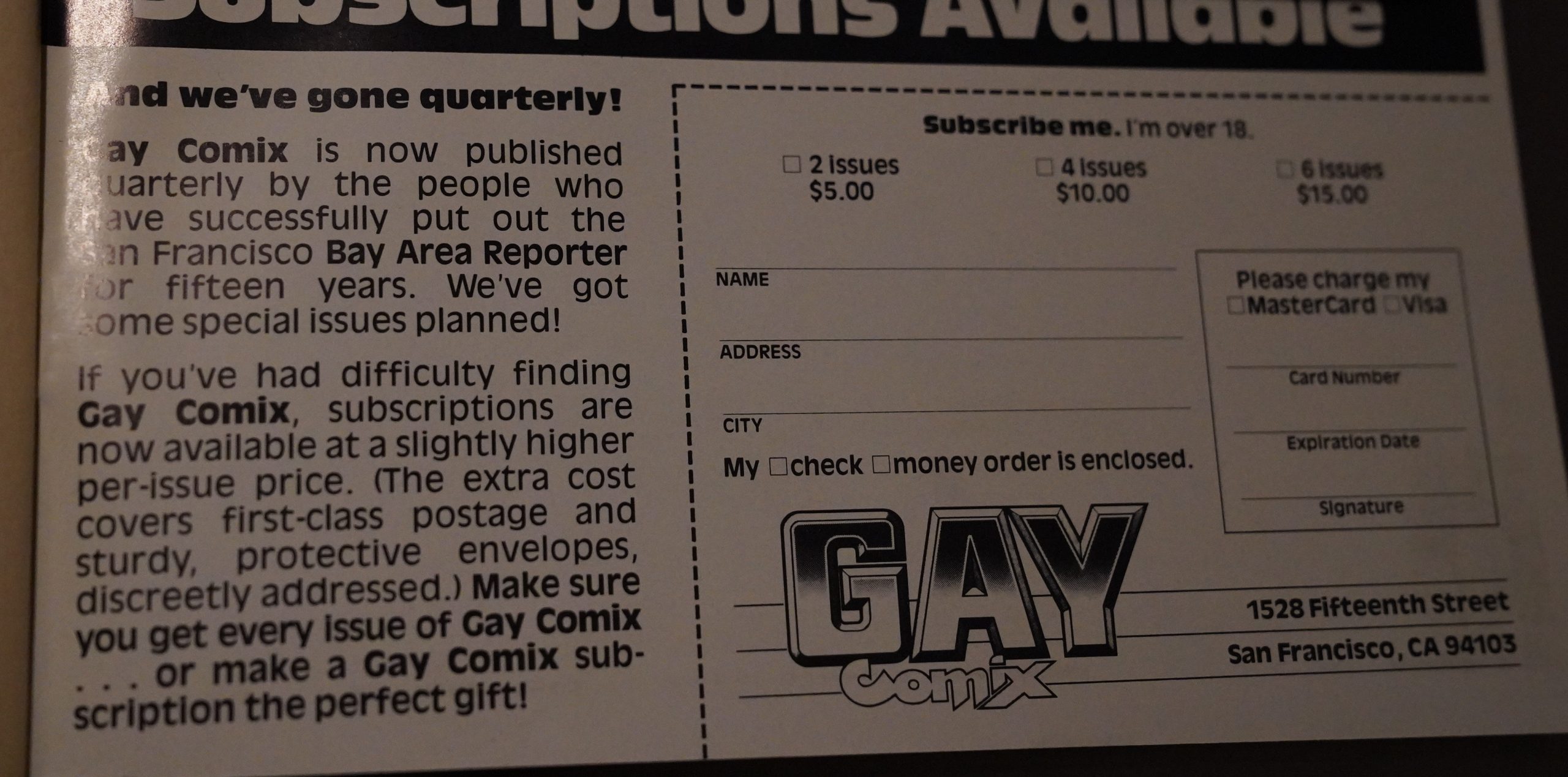

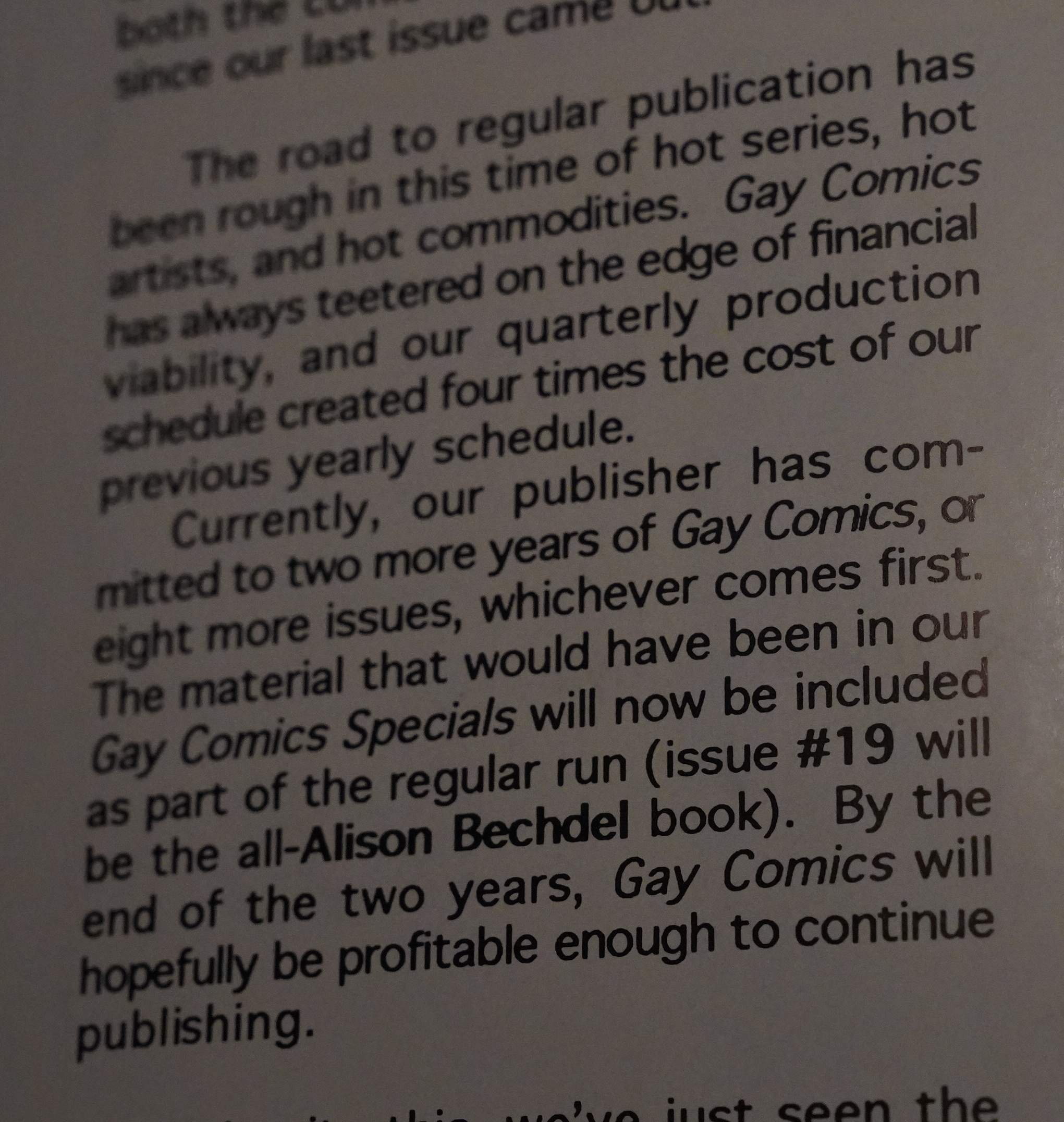

This would be the final issue Kitchen would publish, but we’re not given an explanation why. Kitchen had published the book at a rate of one per year, but with the fifth issue, it’s now a quarterly, and it’s published by Bob Ross.

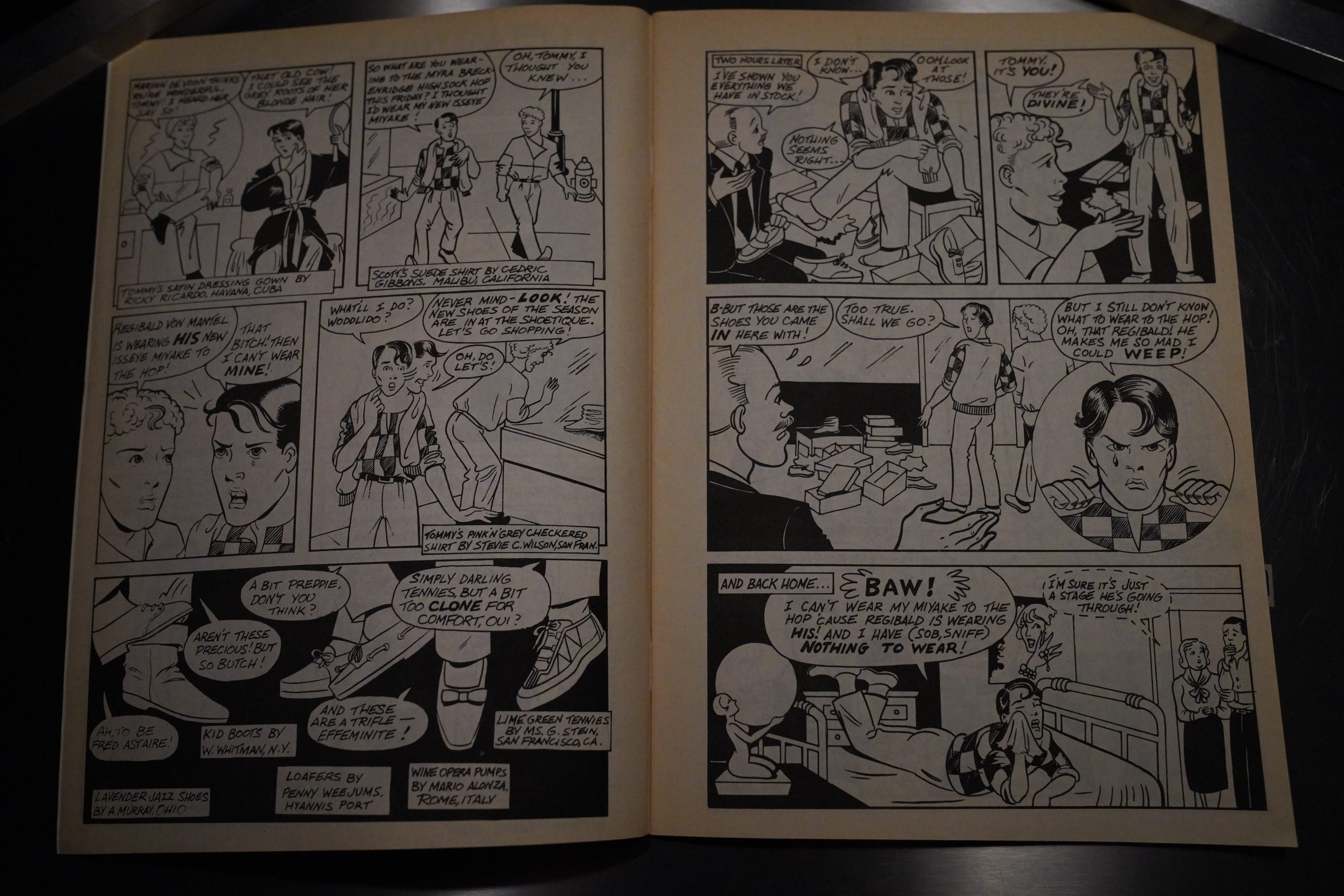

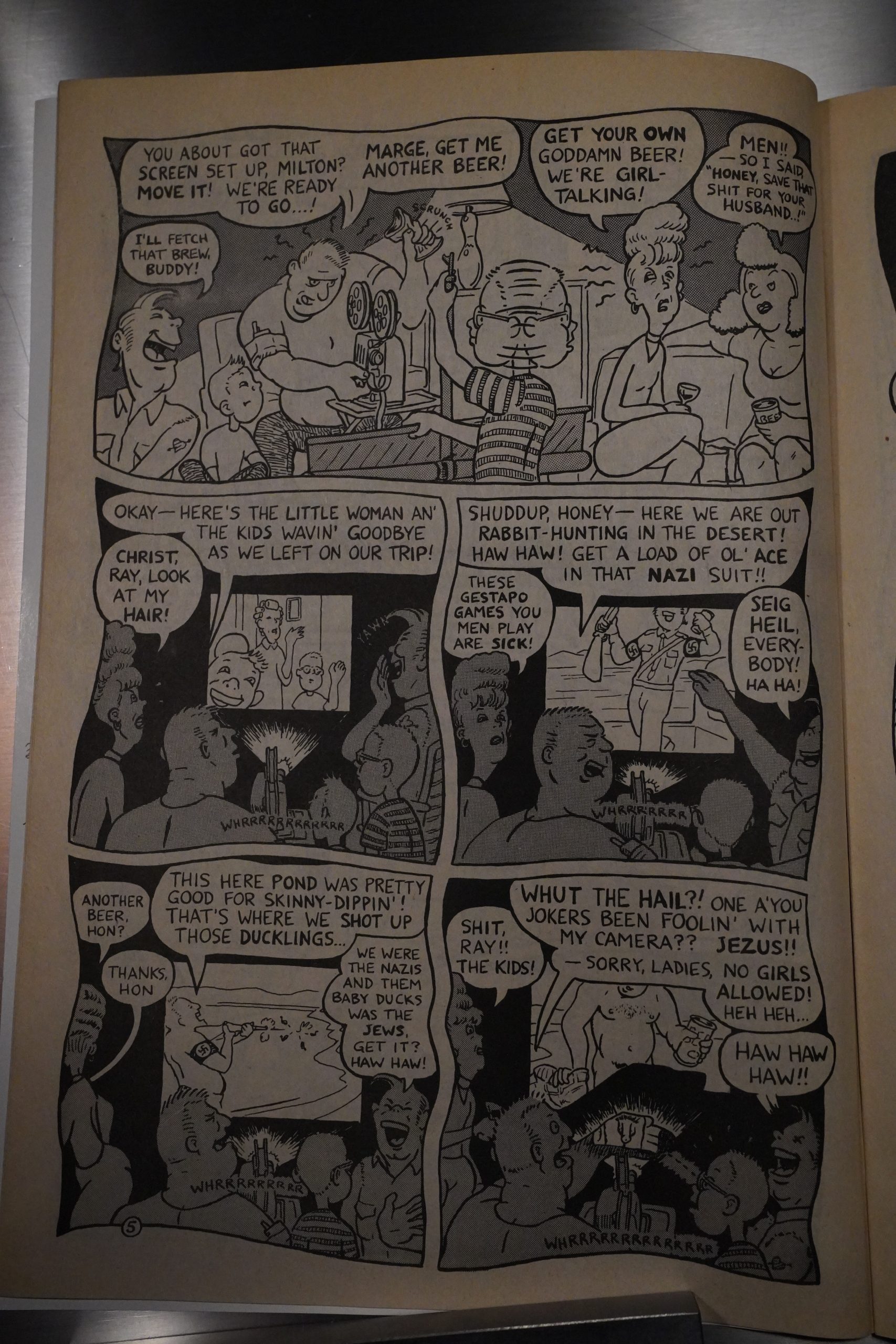

And with the sixth issue, the change in editorial direction is complete: It’s just funny stuff; nothing depressing or very personal. (And not just LGBT either — here’s Trina Robbins.)

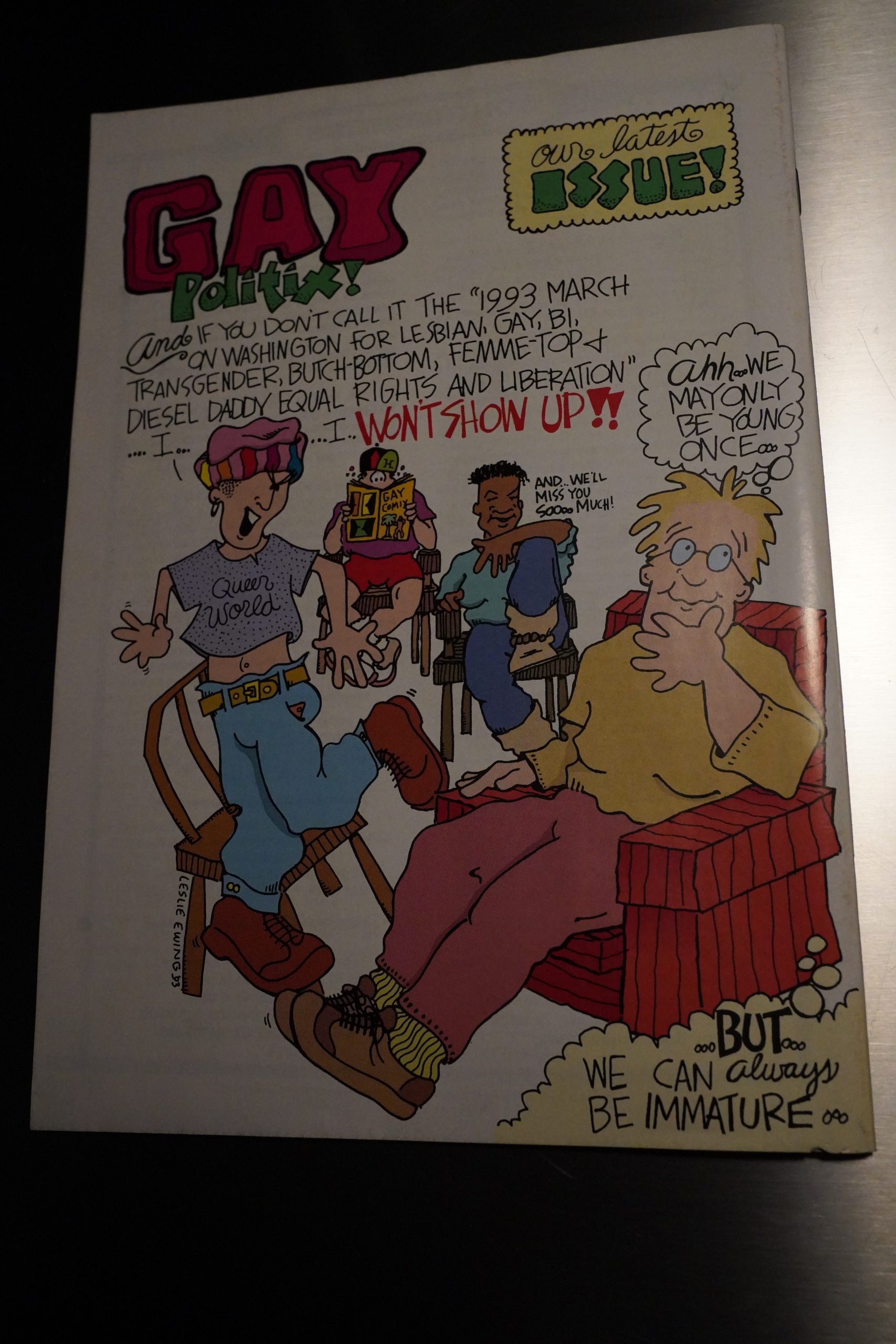

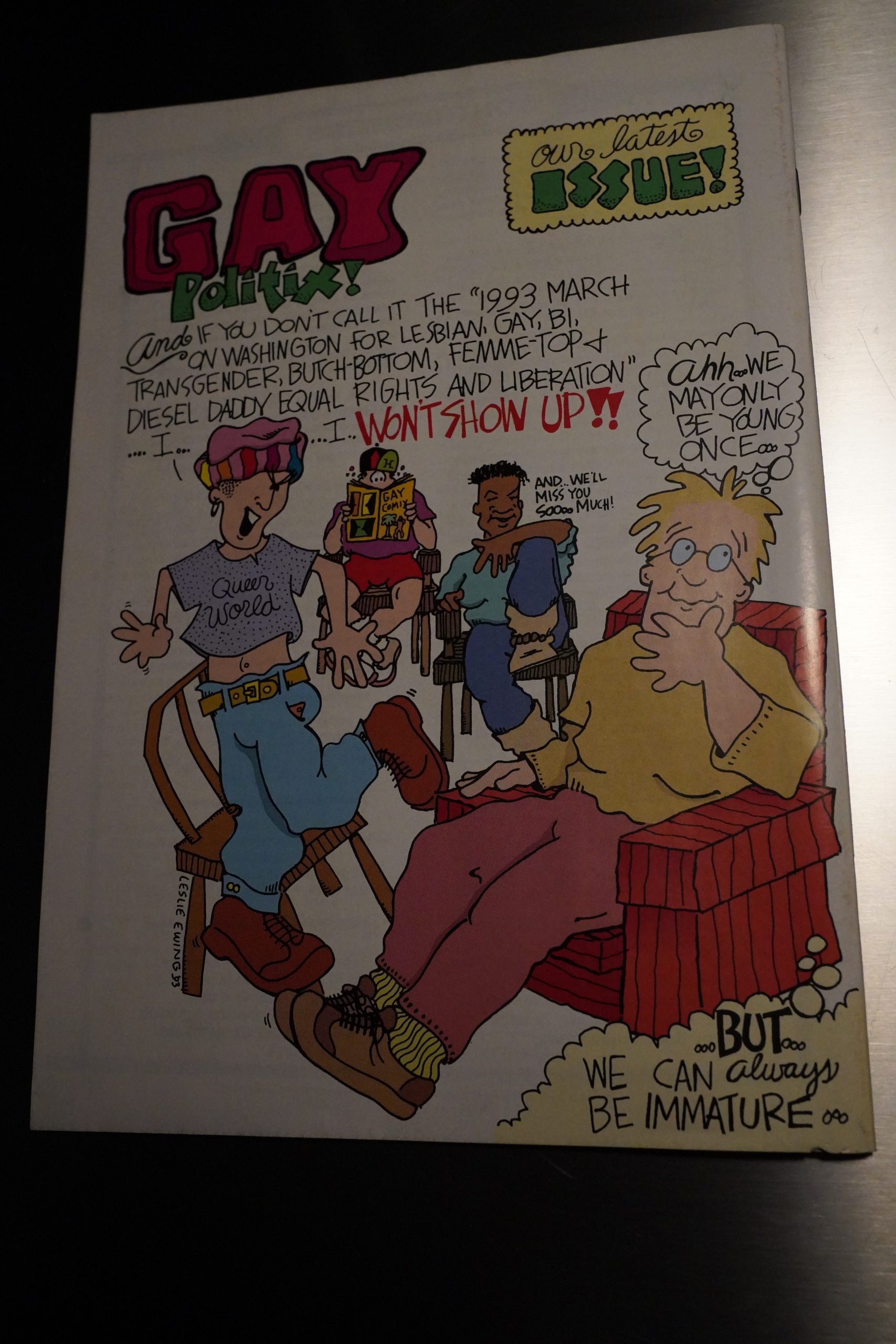

The new names keep coming, and some of them are really good, like Leslie Ewing. It’s so… cute.

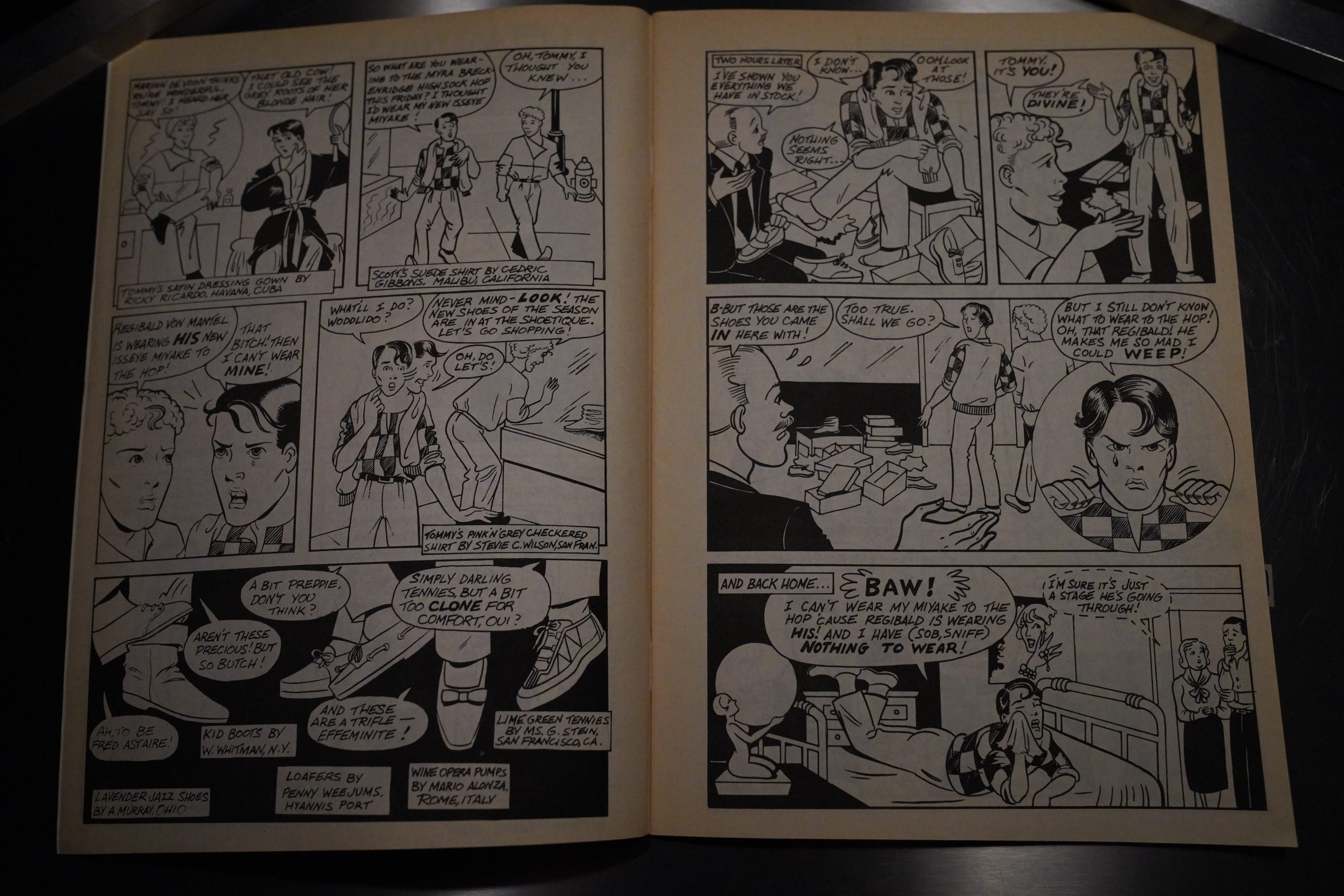

Kurt Erichsen has settled on a troupe of characters, and goes full sitcom mode with them, too. (Not that there’s anything wrong with that.)

And another mainstay has also gone for a more consistent cast of characters, and while not completely sitcom-ish, it’s certainly getting there.

So I think we pretty much have the new aesthetic, fresh for 1985: Sitcoms, but on paper.

So it’s published by the same people who put out the Bay Area Reporter? Ah, that’s the aforementioned Bob Ross.

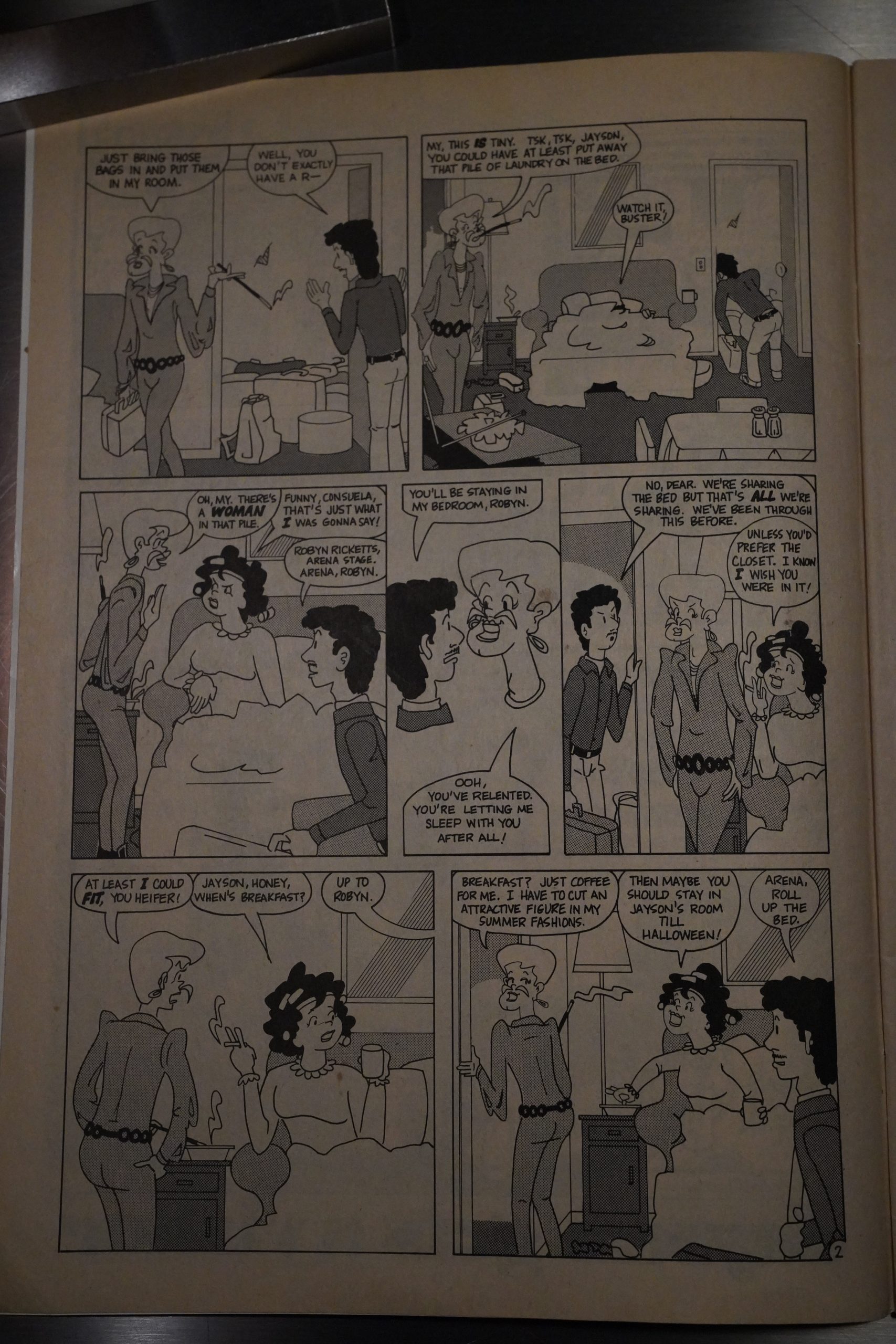

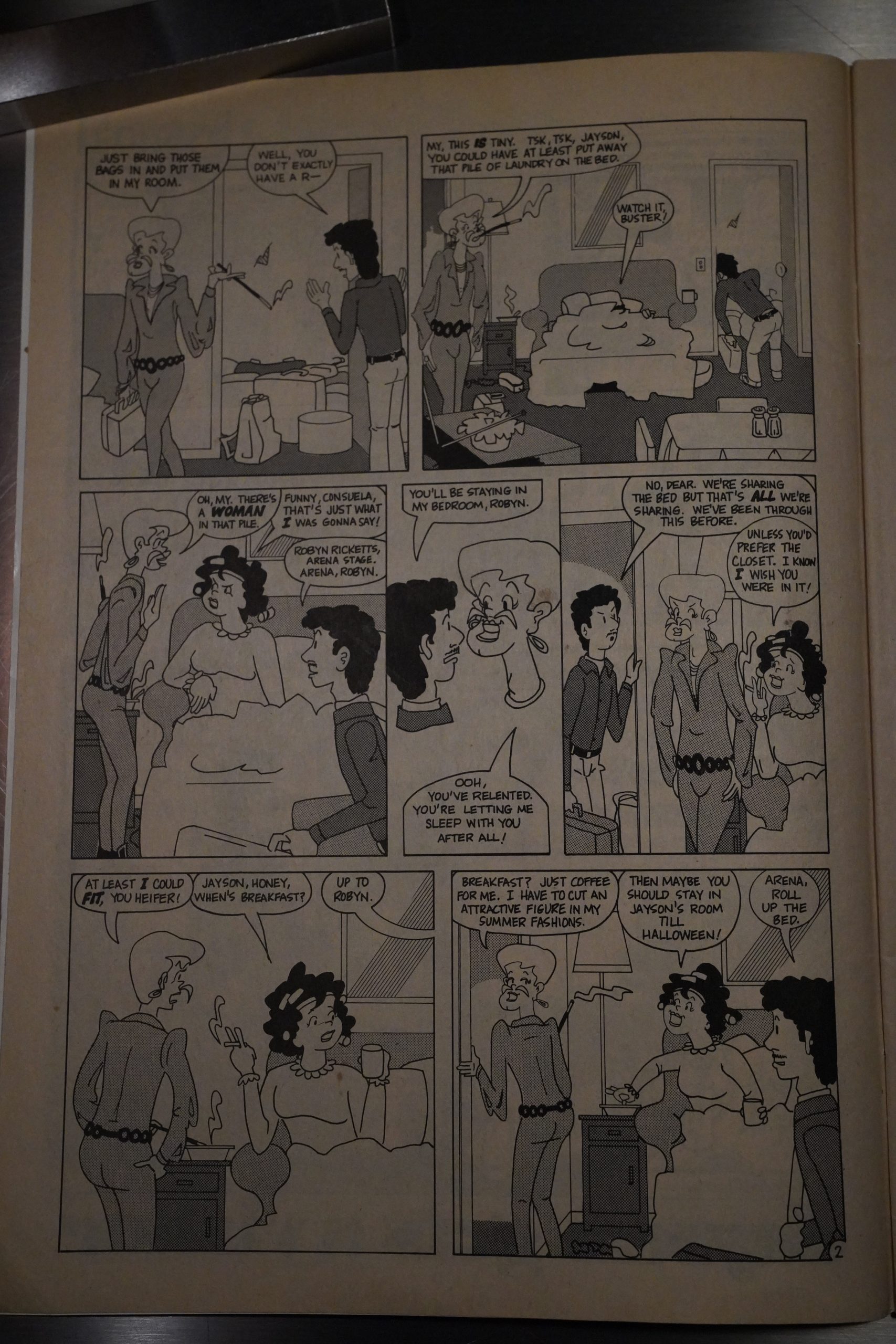

One of the staples from this phase of Gay Comix is Jayson by J. A. Krell, and again, it’s a sitcom, and one of the most annoying varieties of that genre — the one where they don’t write jokes, but just have people insulting each other incessantly. And the artwork here is all like that — just barely serviceable.

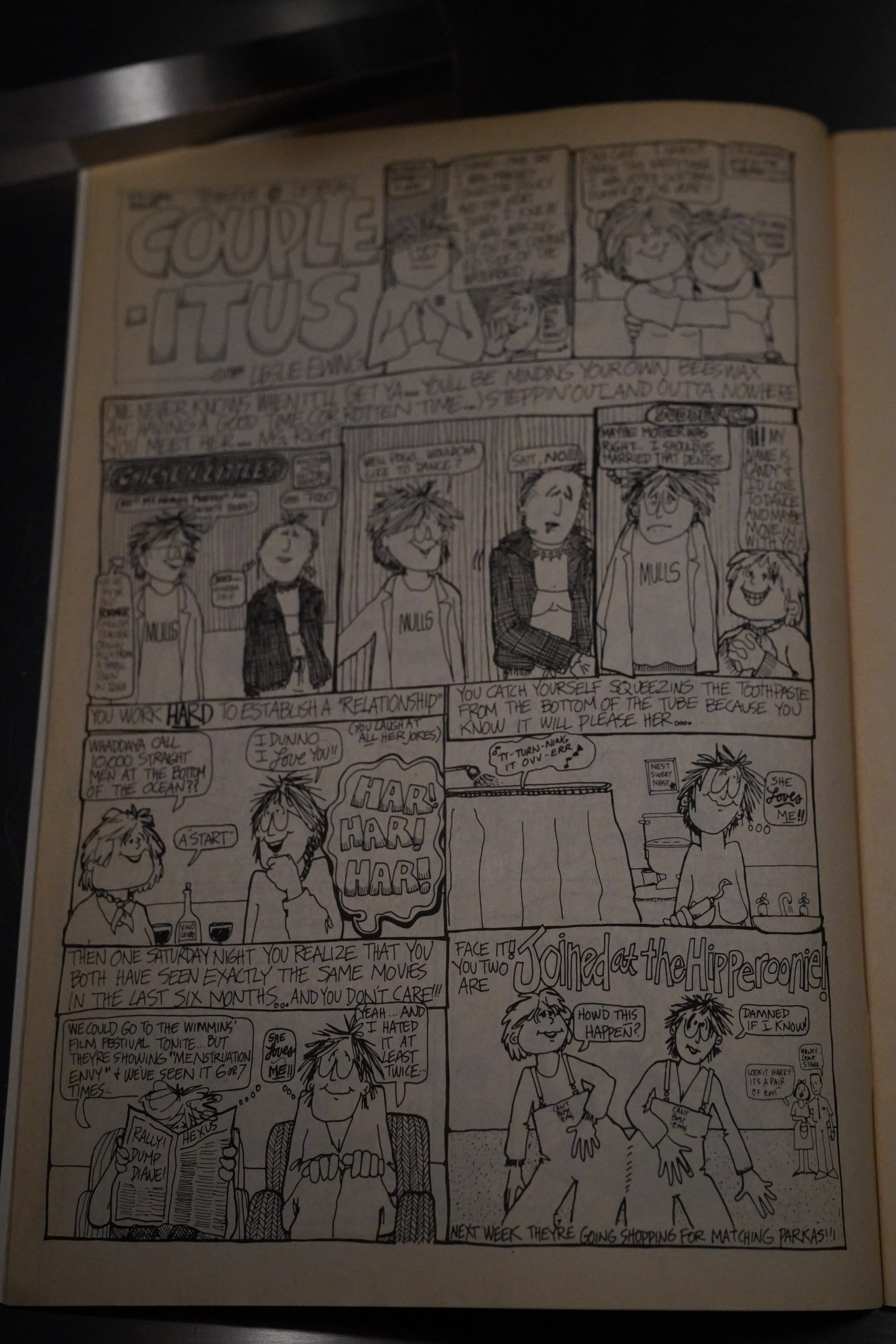

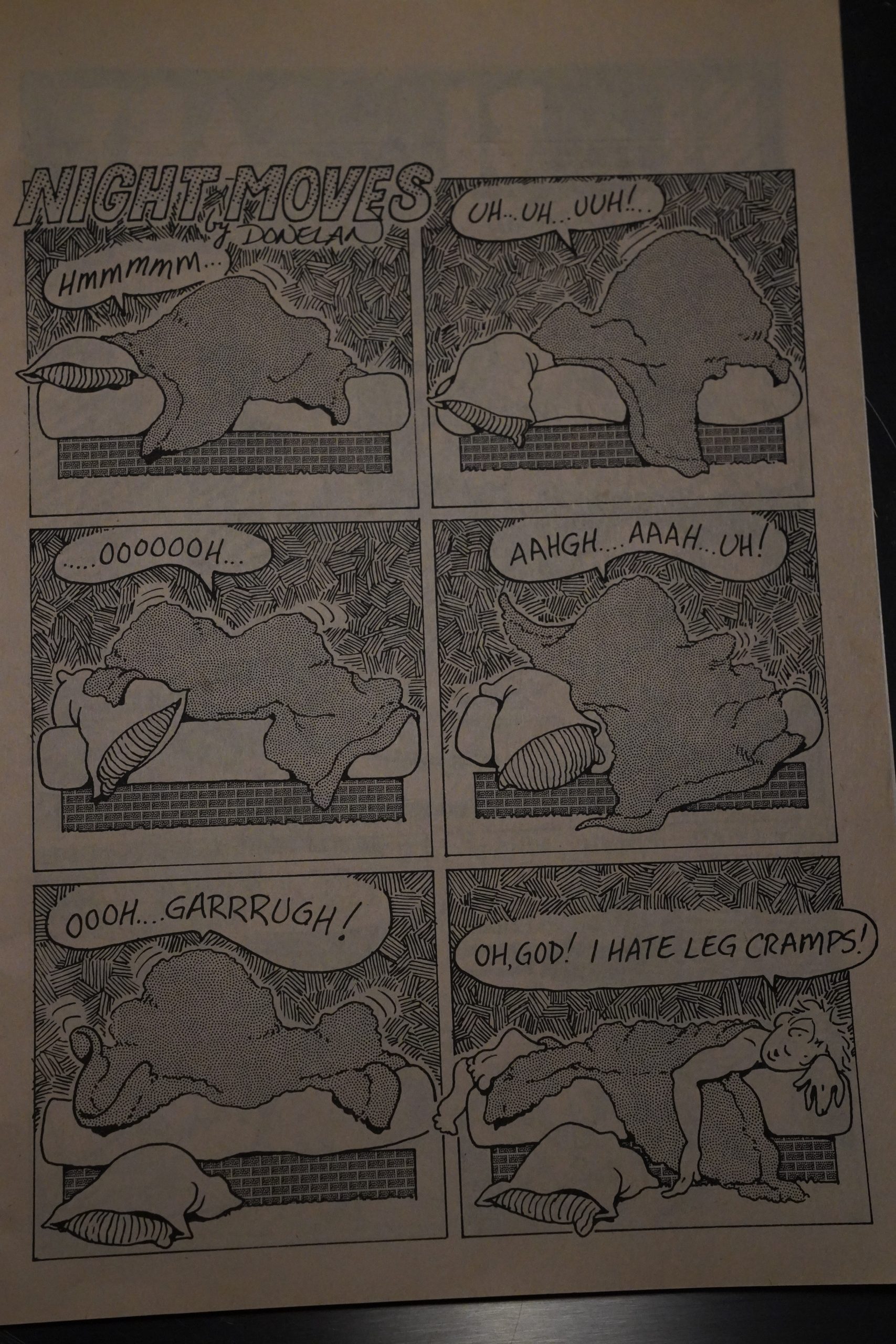

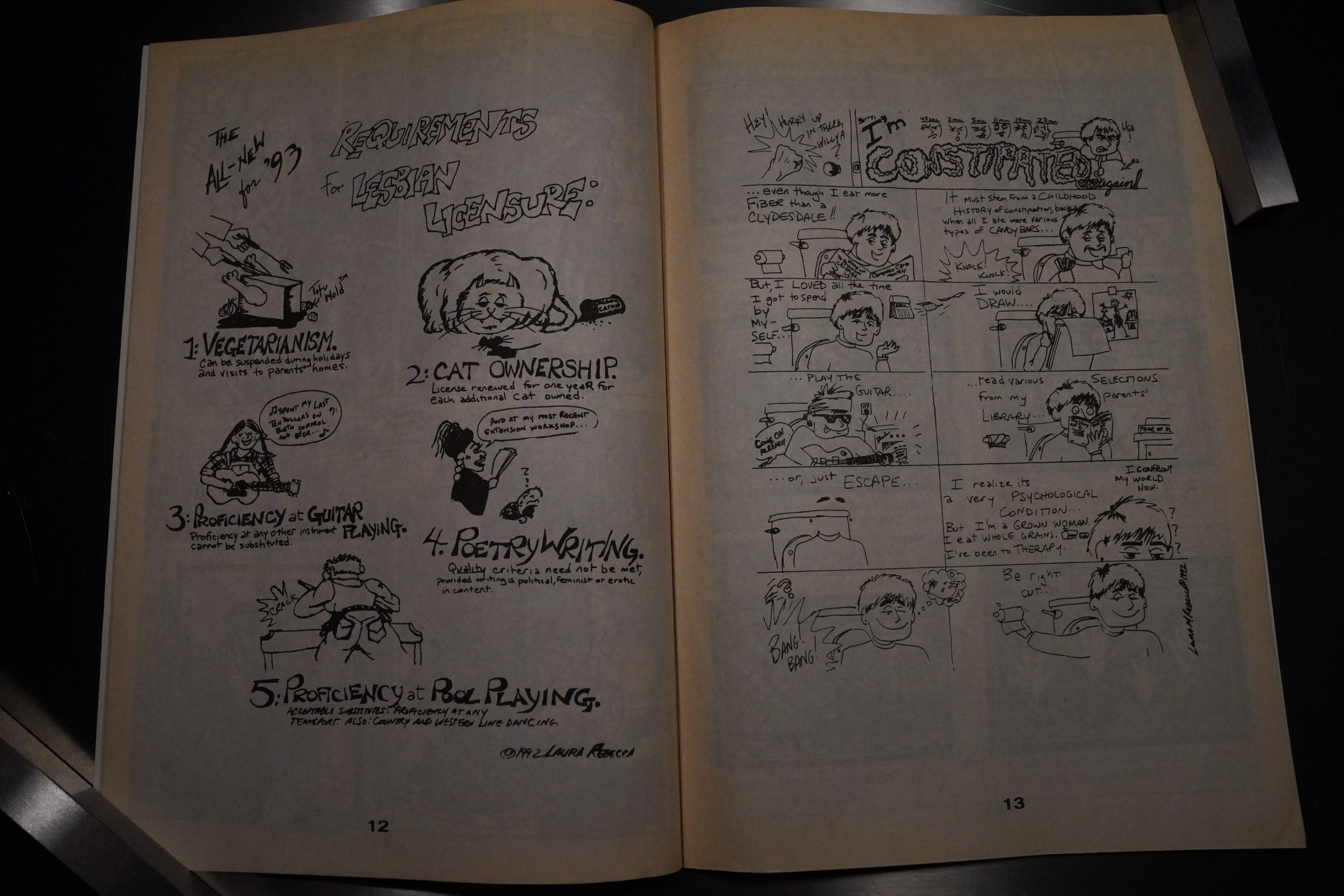

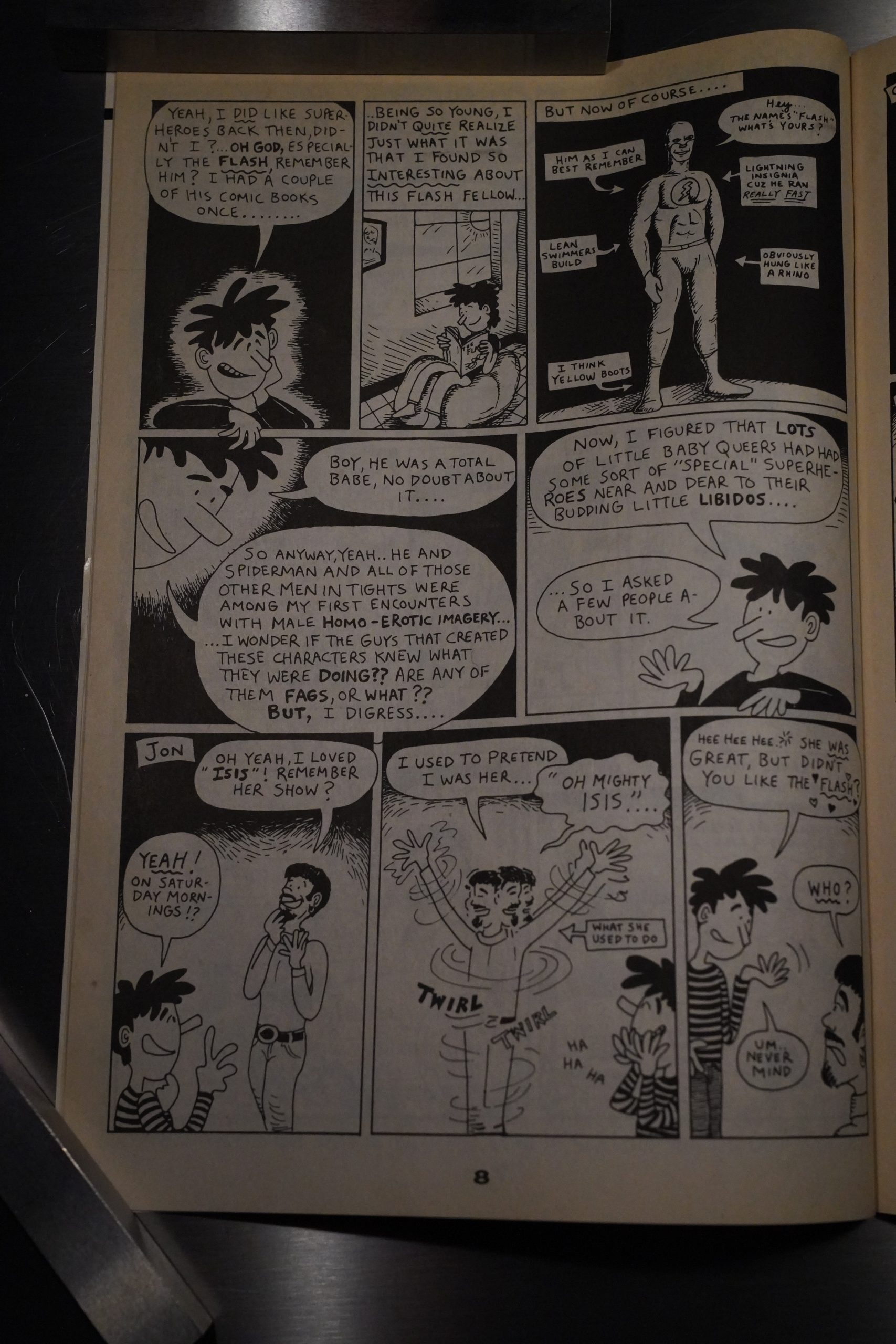

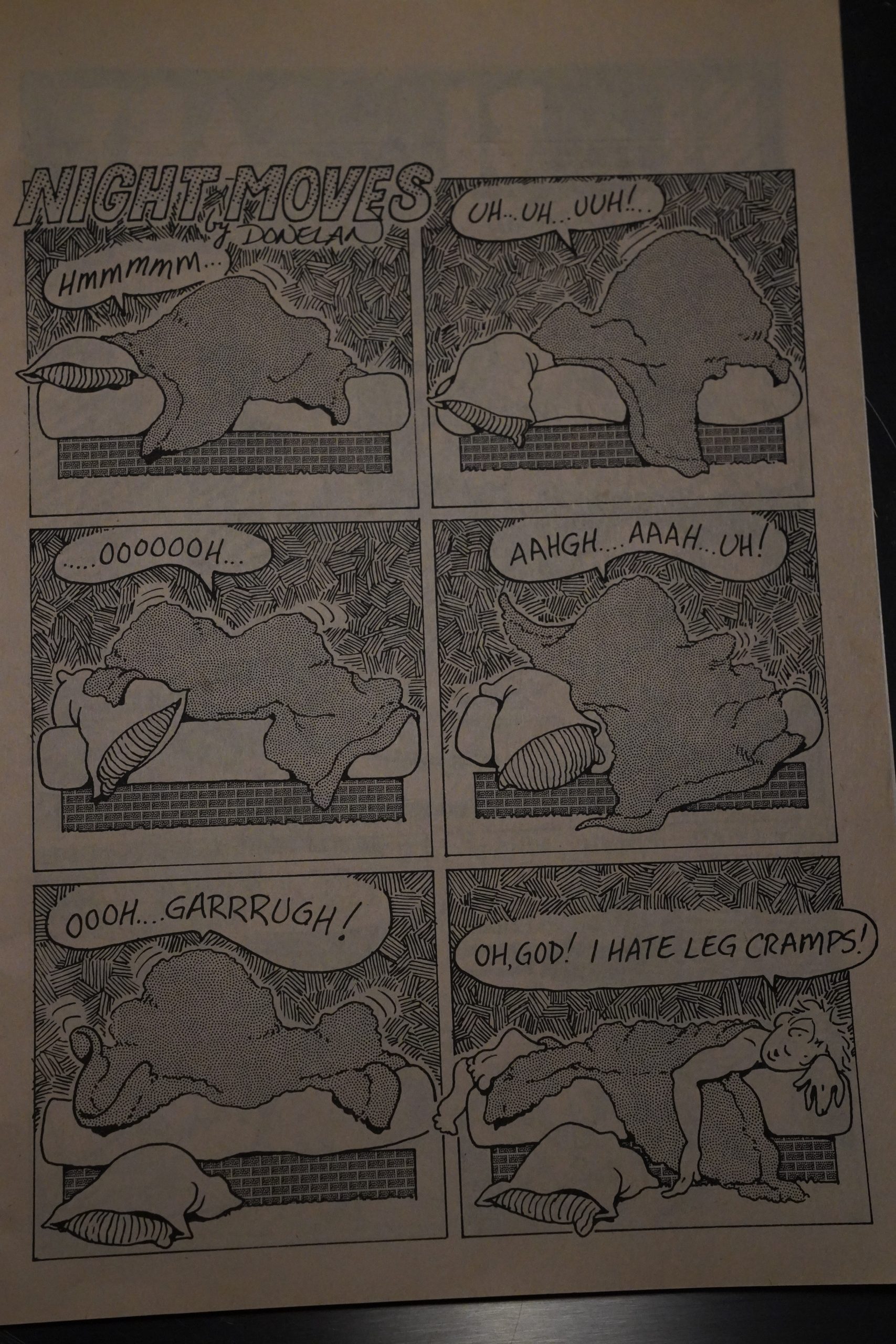

And then we get… observational humour from Donelan. It’s funny because it’s true, I guess.

What I’m saying is is that these issues are pretty dire. Each issue is 40 pages, so I’m wondering whether Triptow was having major problems getting people to contribute. Probably not a high page rate, either?

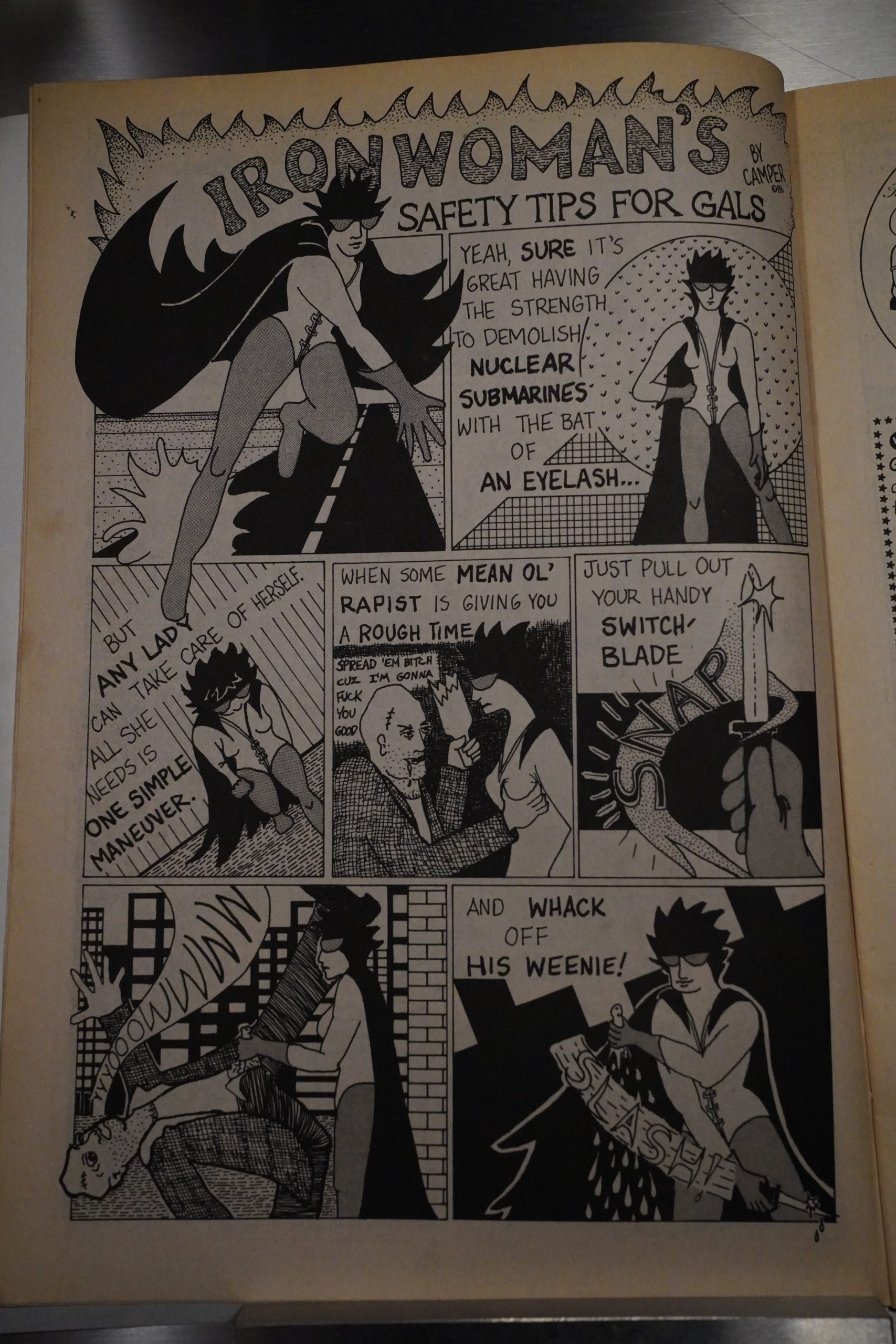

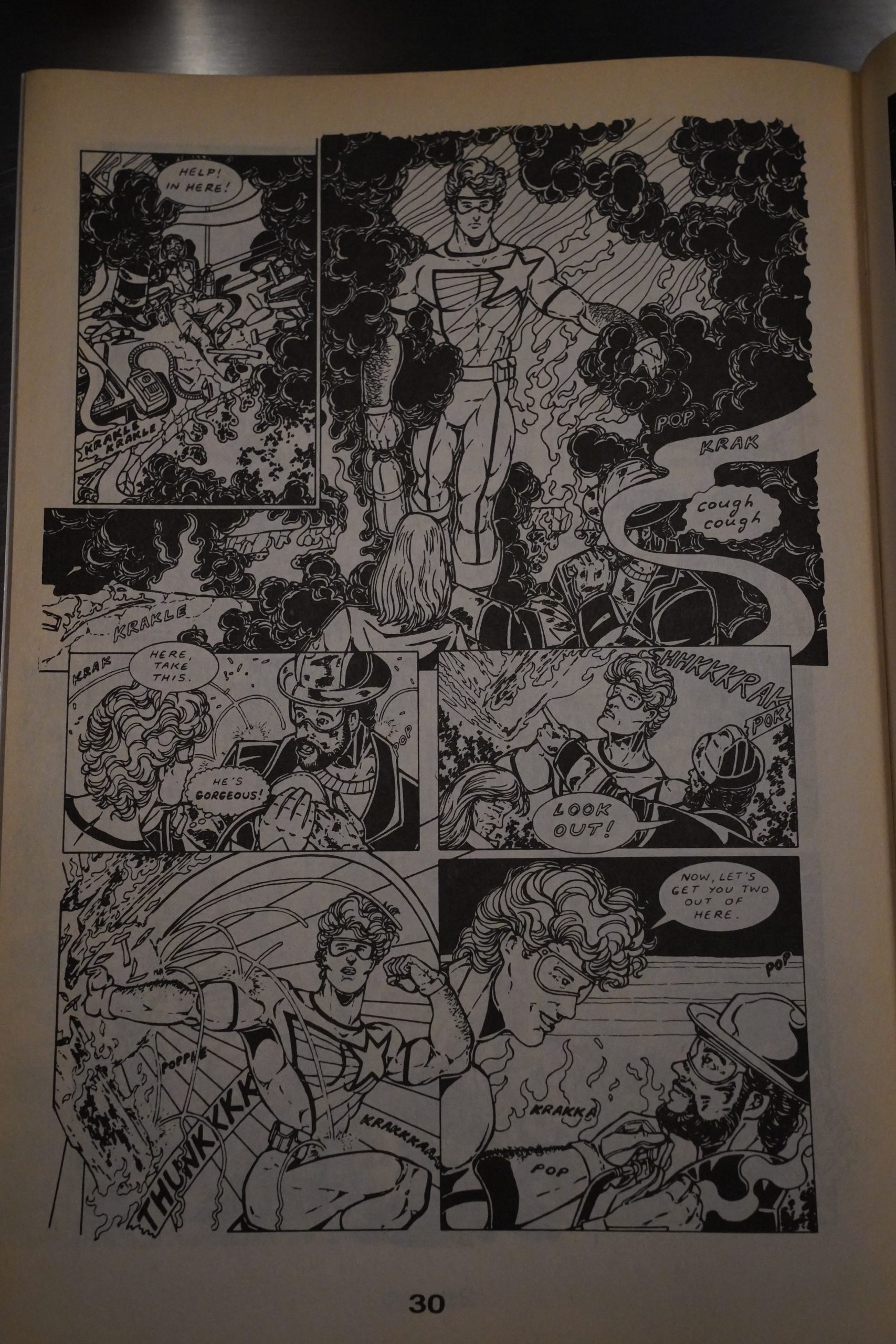

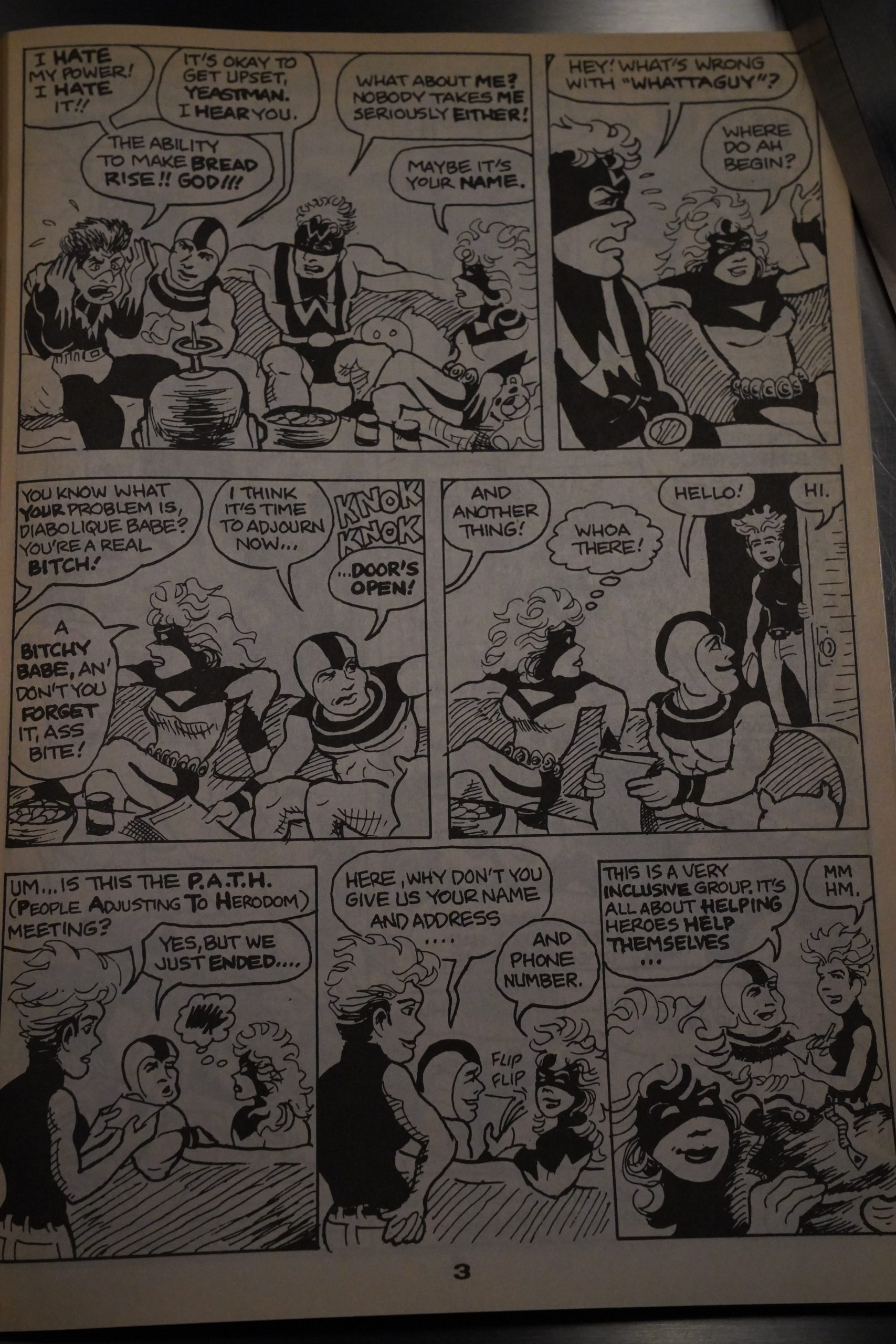

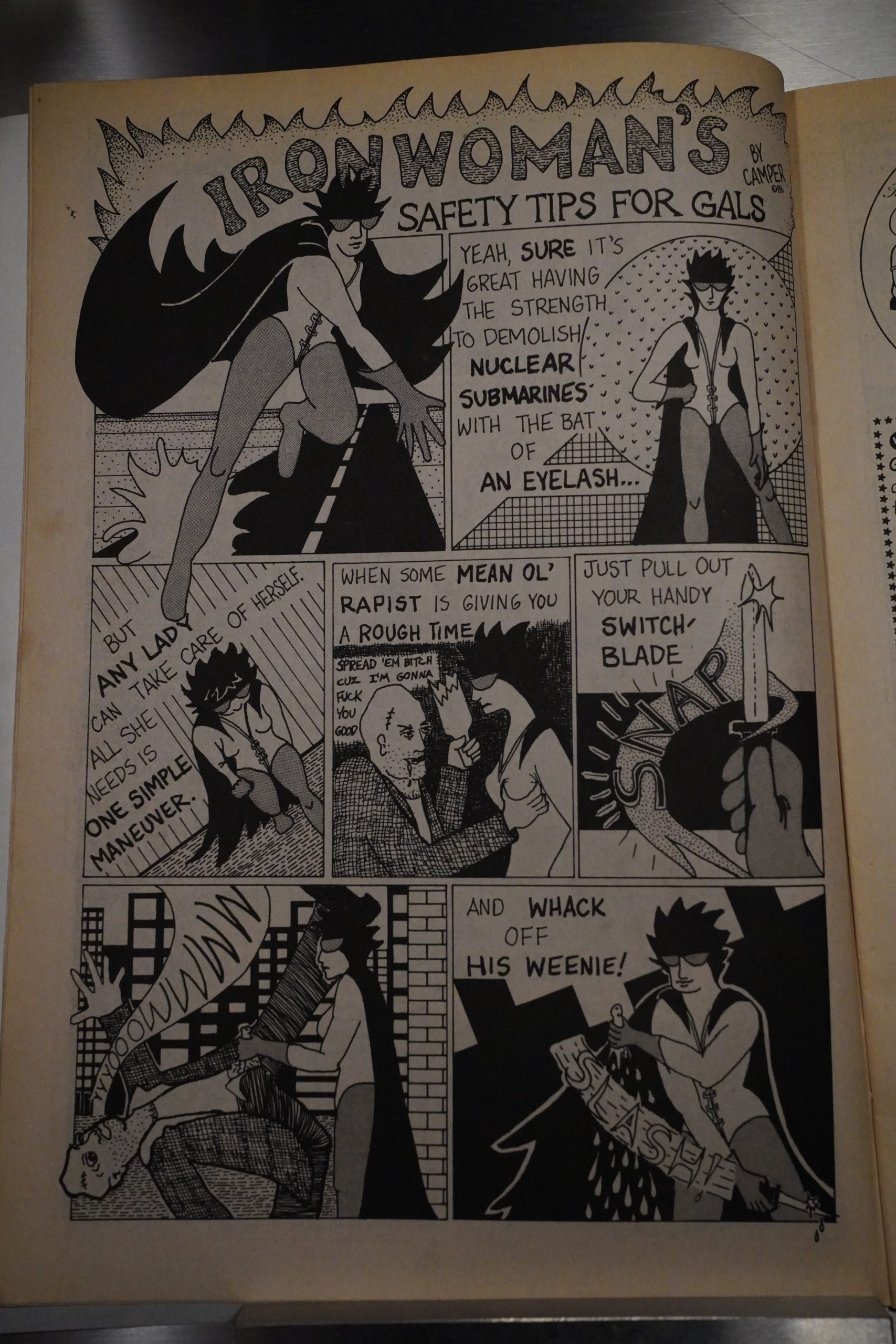

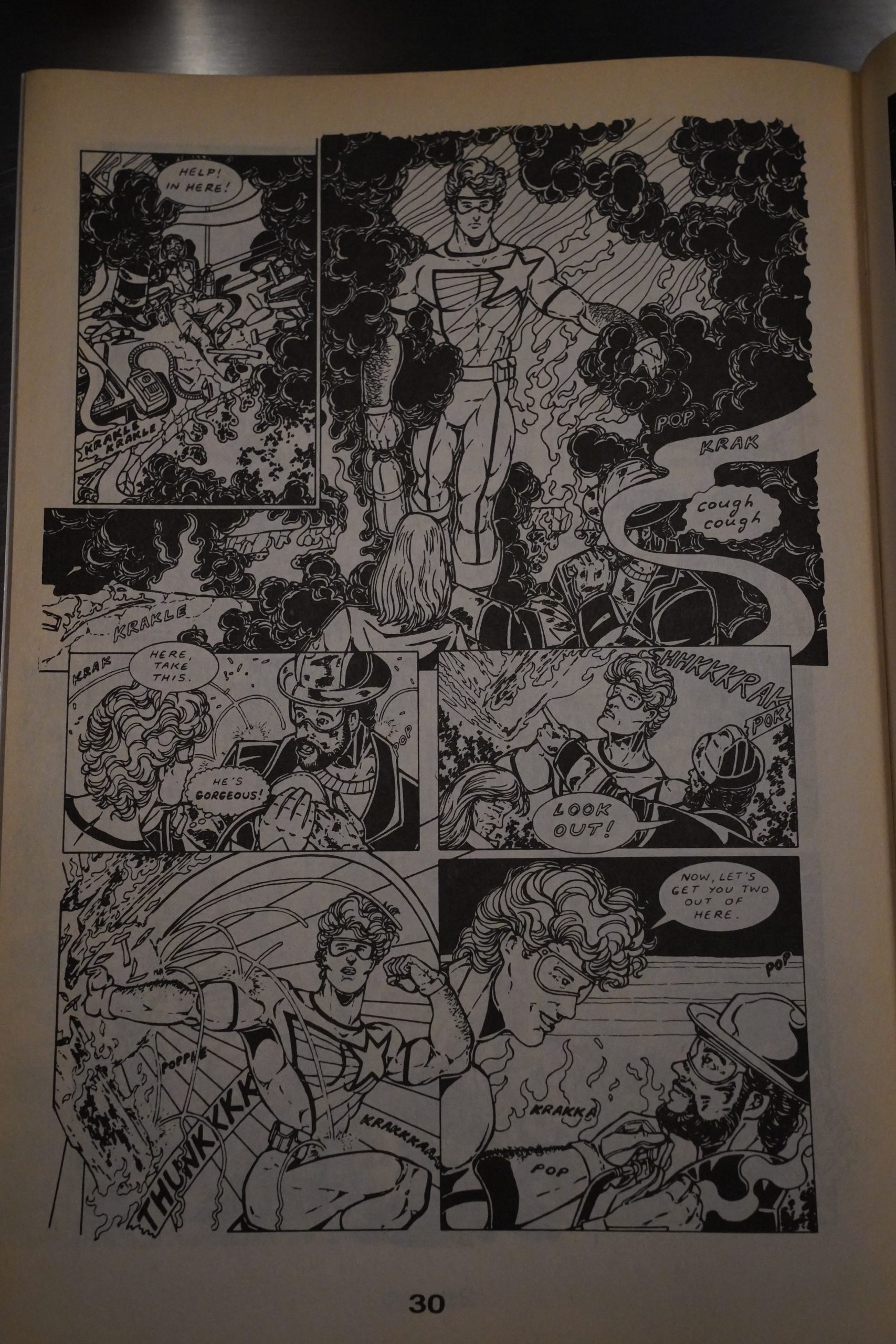

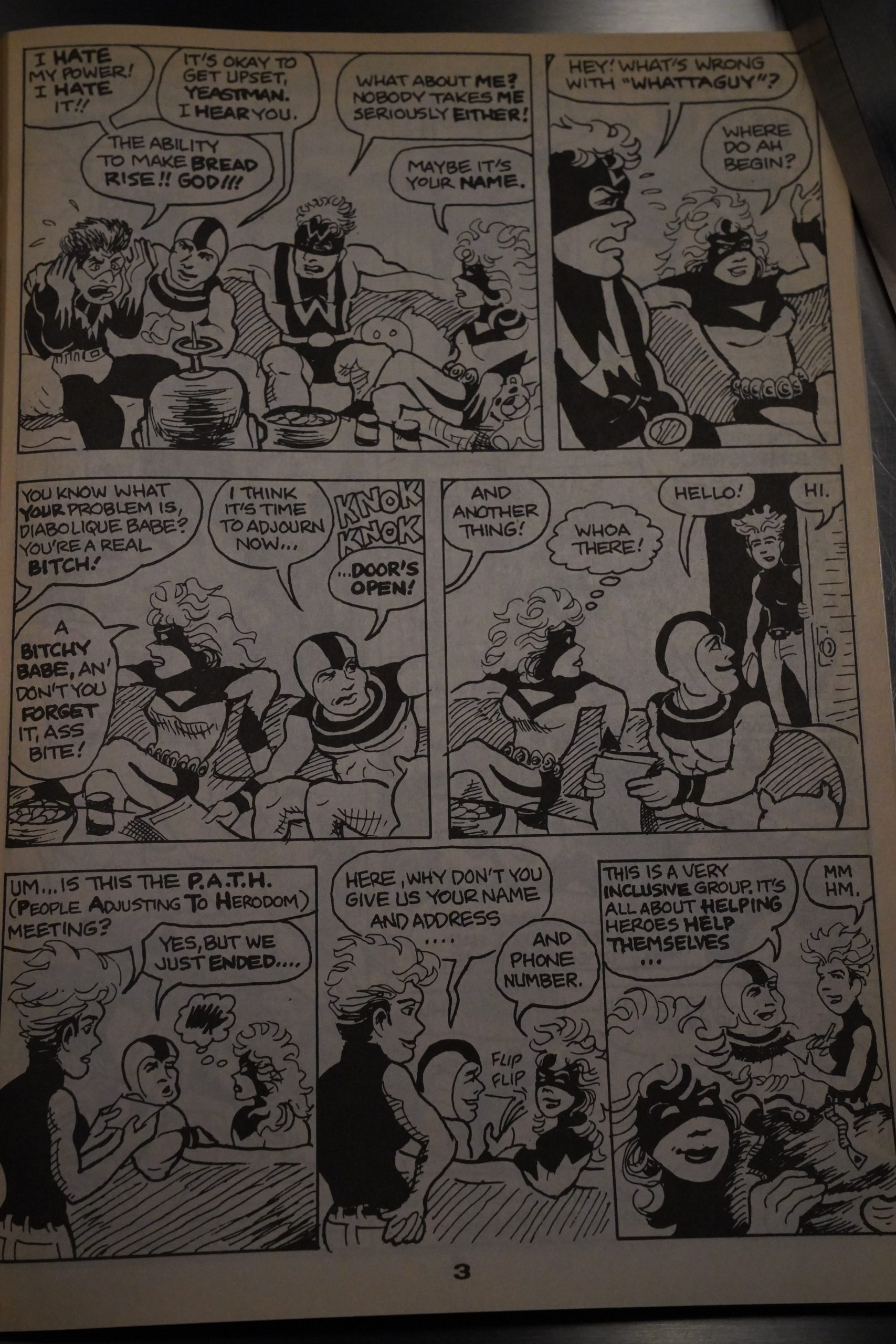

Then we get a superhero special, and… things grow even more tedious. But at least there’s Jennifer Camper.

But it’s mostly like this thing — Captain Condom — by Jeff Jacklin (if I’m interpreting the signature correctly; there’s still no list of contributors to be found).

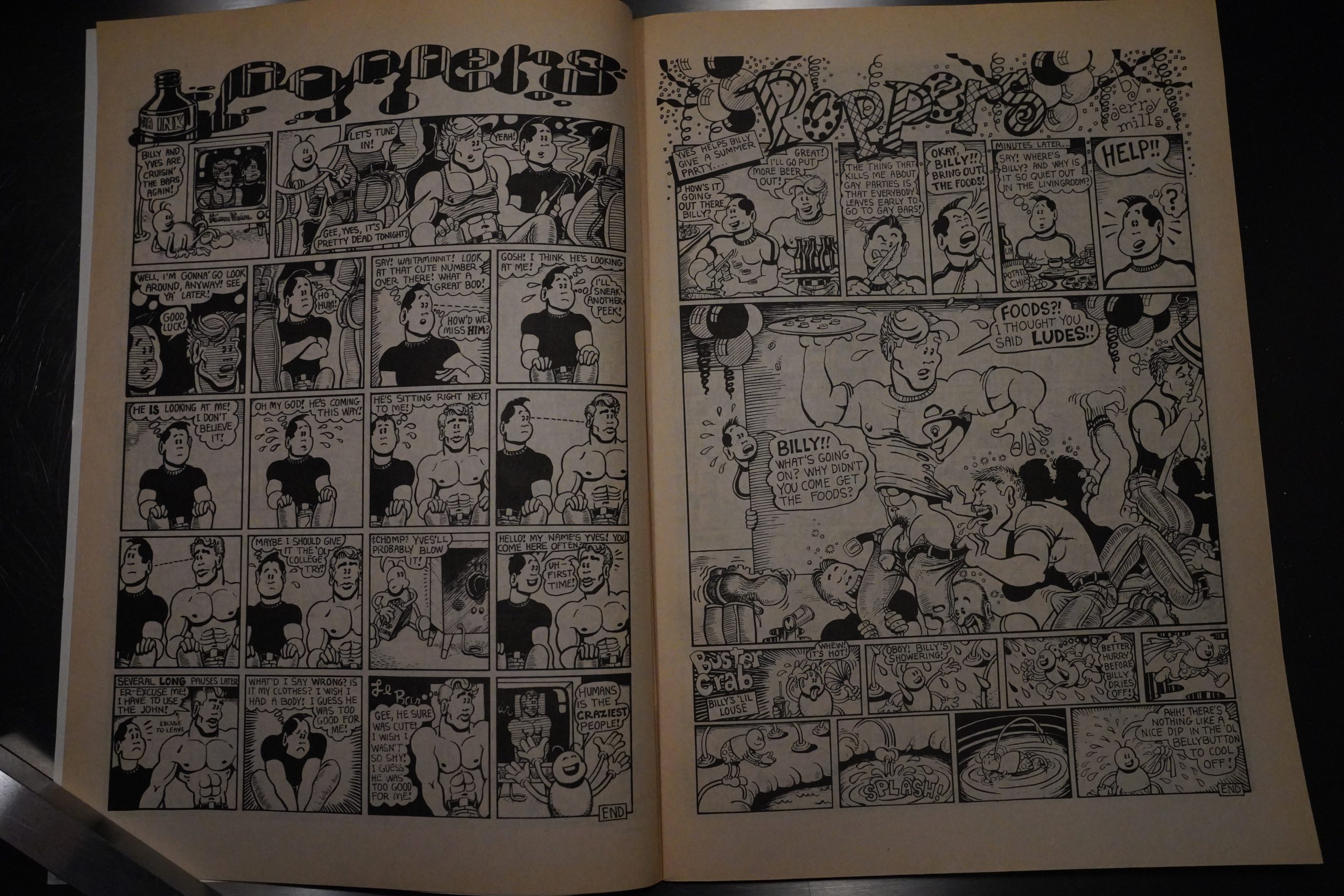

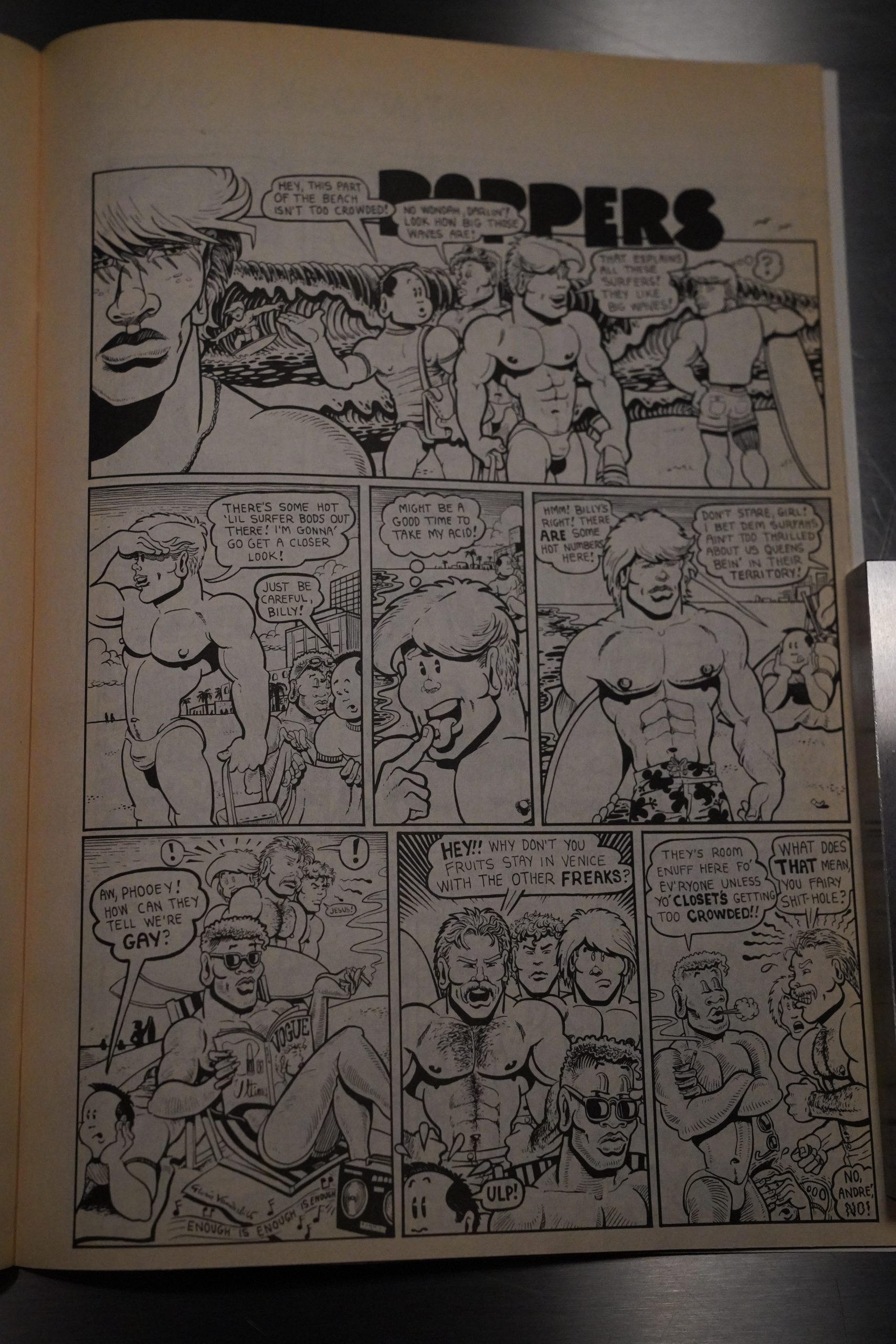

Then we get an issue that’s all Poppers (by Jerry Mills), and those are drawn nicely, at least. (Even if basically all the people who are supposed to be attractive are drawn totally identically.) It entertaining.

Of the regulars, Triptow himself is the only one that seems to grow as an artist. Triptow’s pieces are entertaining and interestingly told.

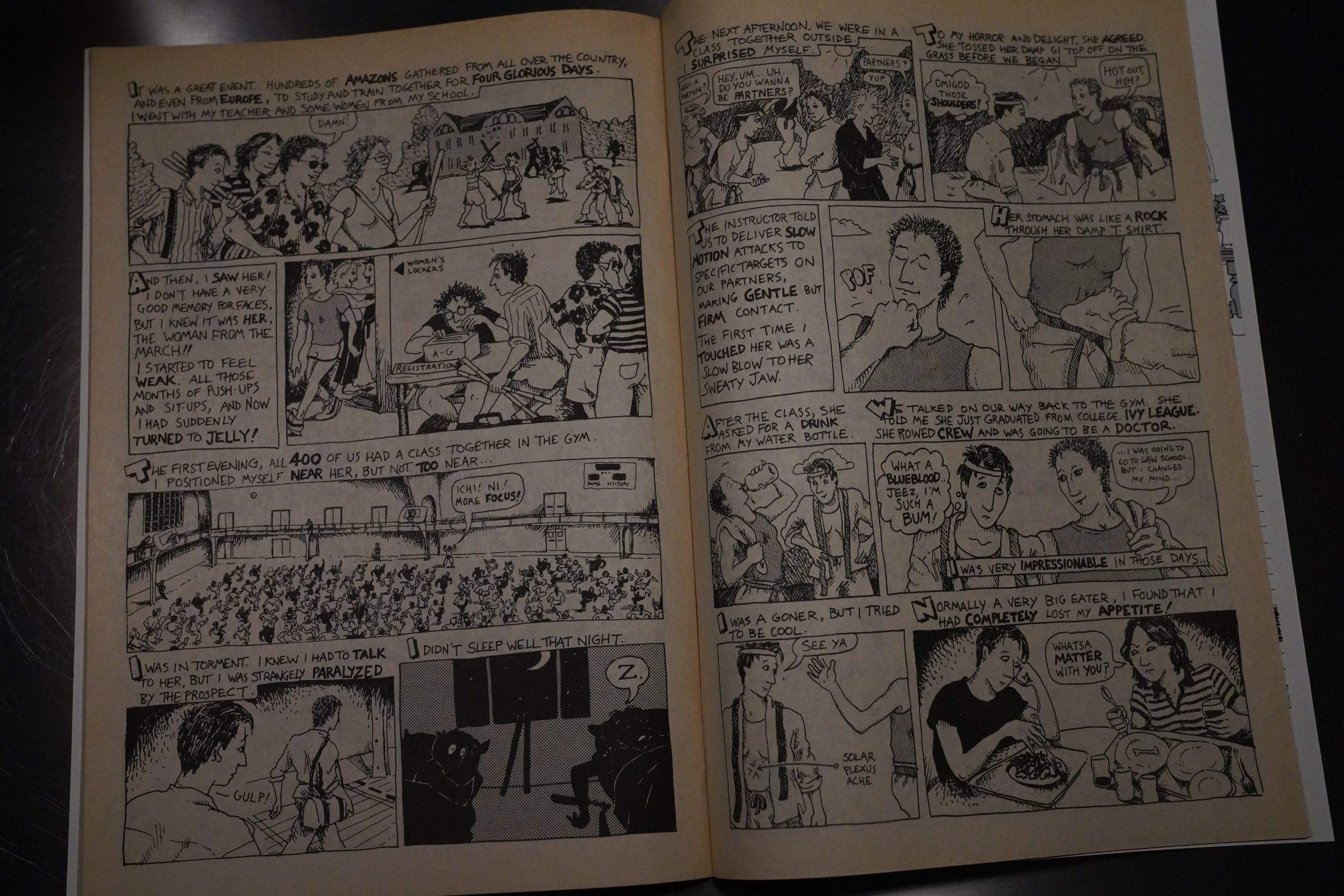

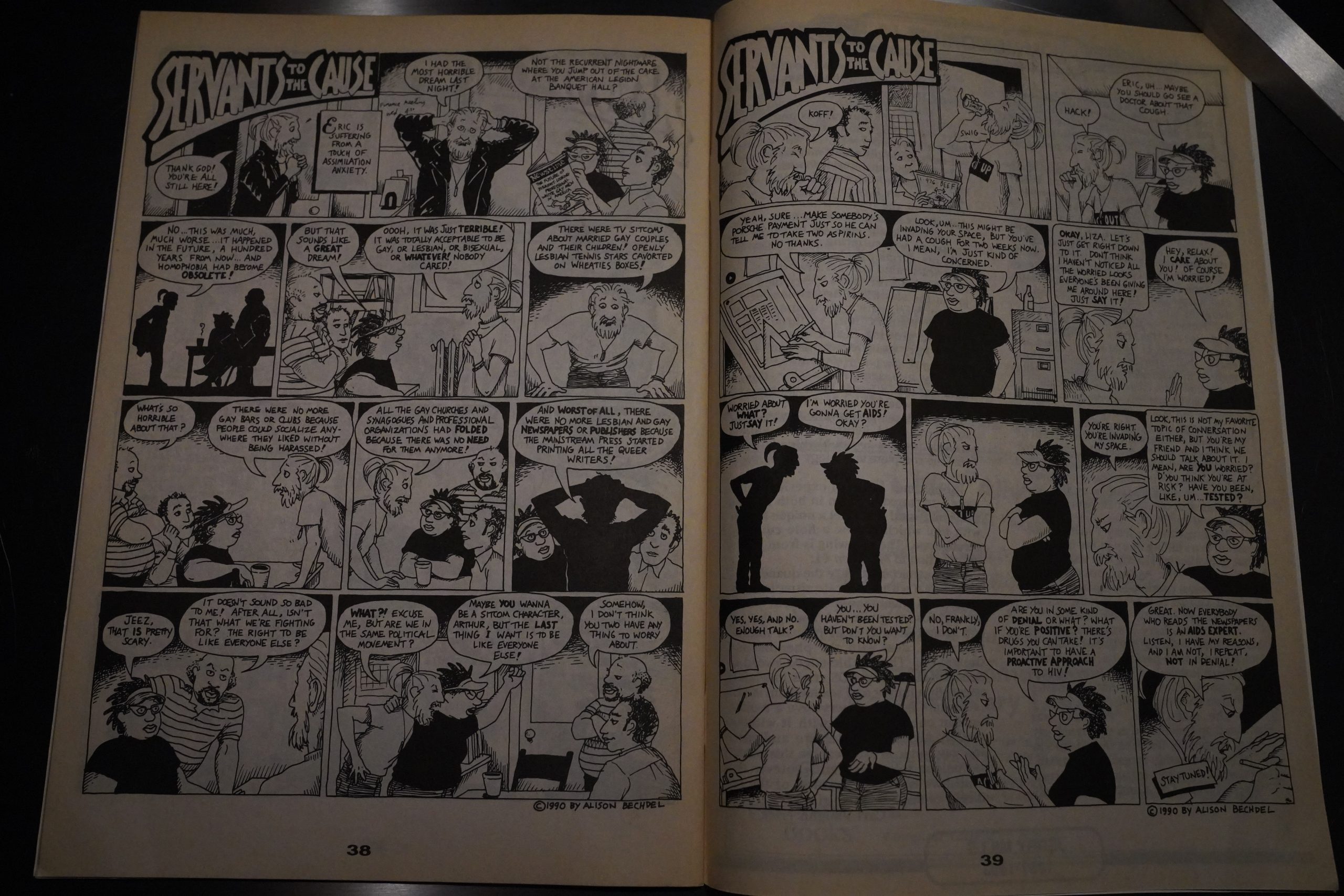

*gasp* Alison Bechdel! Finally some talent. And it’s a pretty nice story, and best of all — it’s not a sitcom.

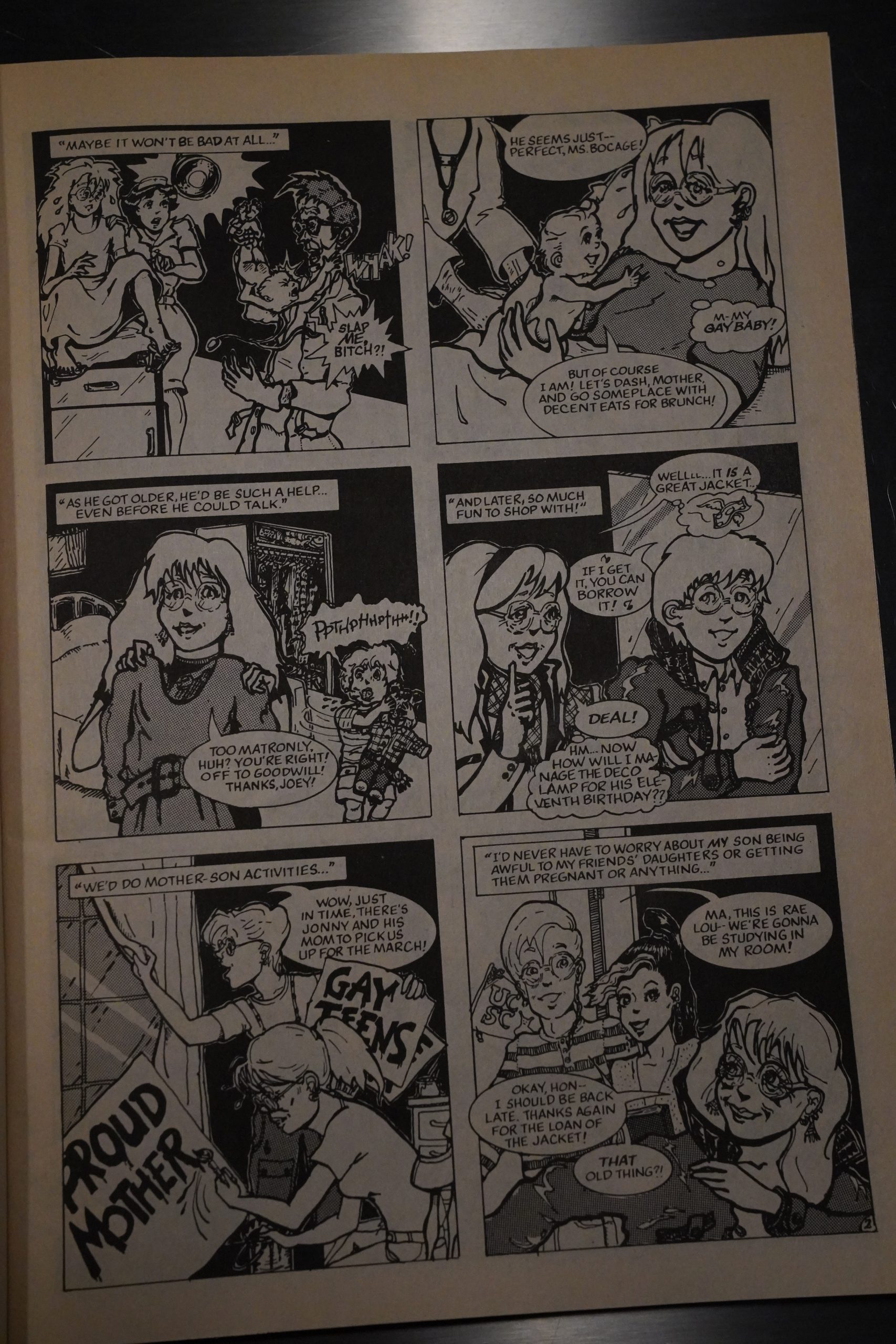

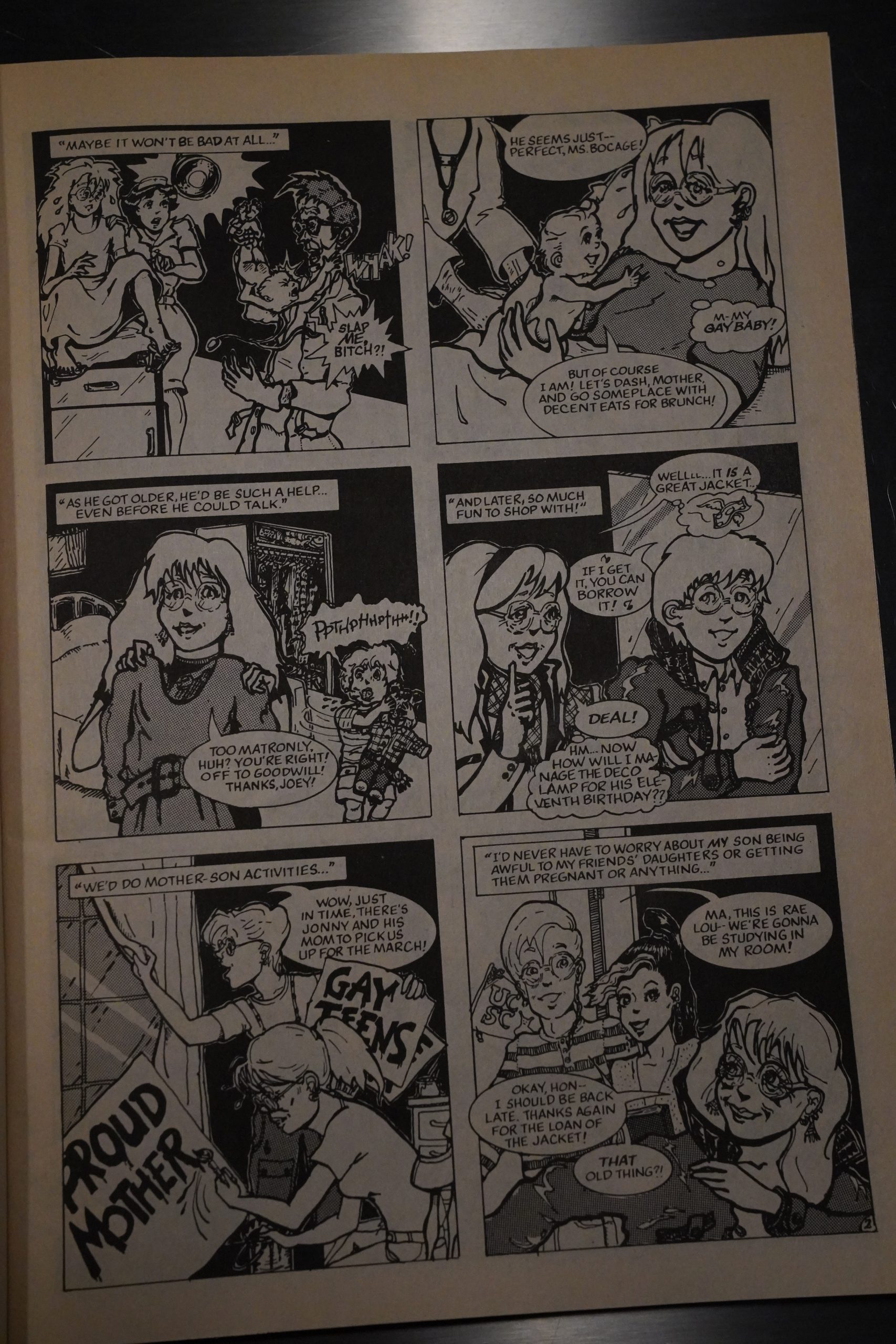

OK, typing this I feel I’m more critical than I was than when I was actually reading it — my narrative here seems to be taking off on its own. So let me retrench: I found reading these issues to be mostly fine. Now that it’s mostly sitcom stuff, the issues do have a sort of cohesion, and we do get the occasional fab stuff, like this short Angela Bocage story.

It’s still an OK book, even if there’s little that’s memorable from these years.

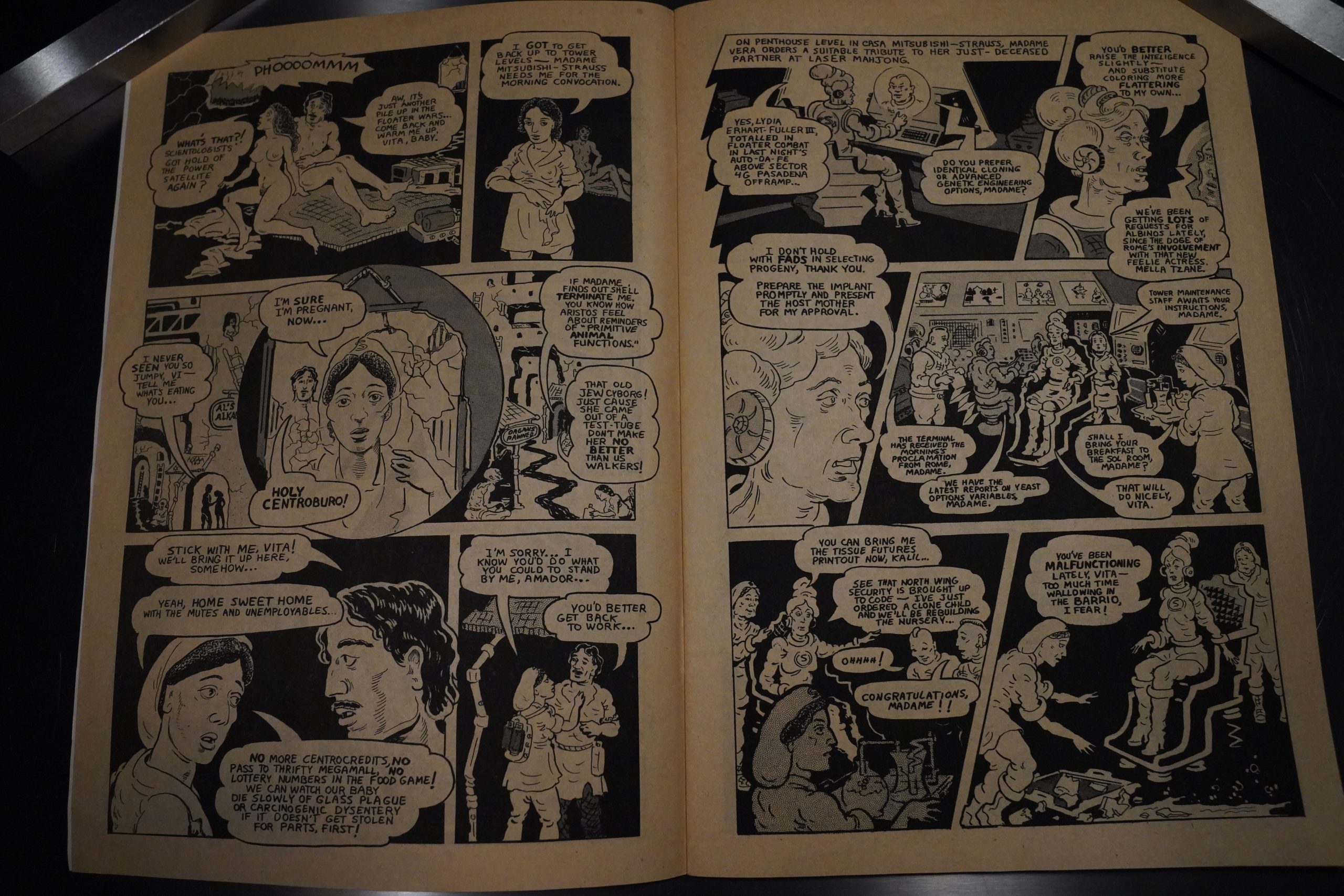

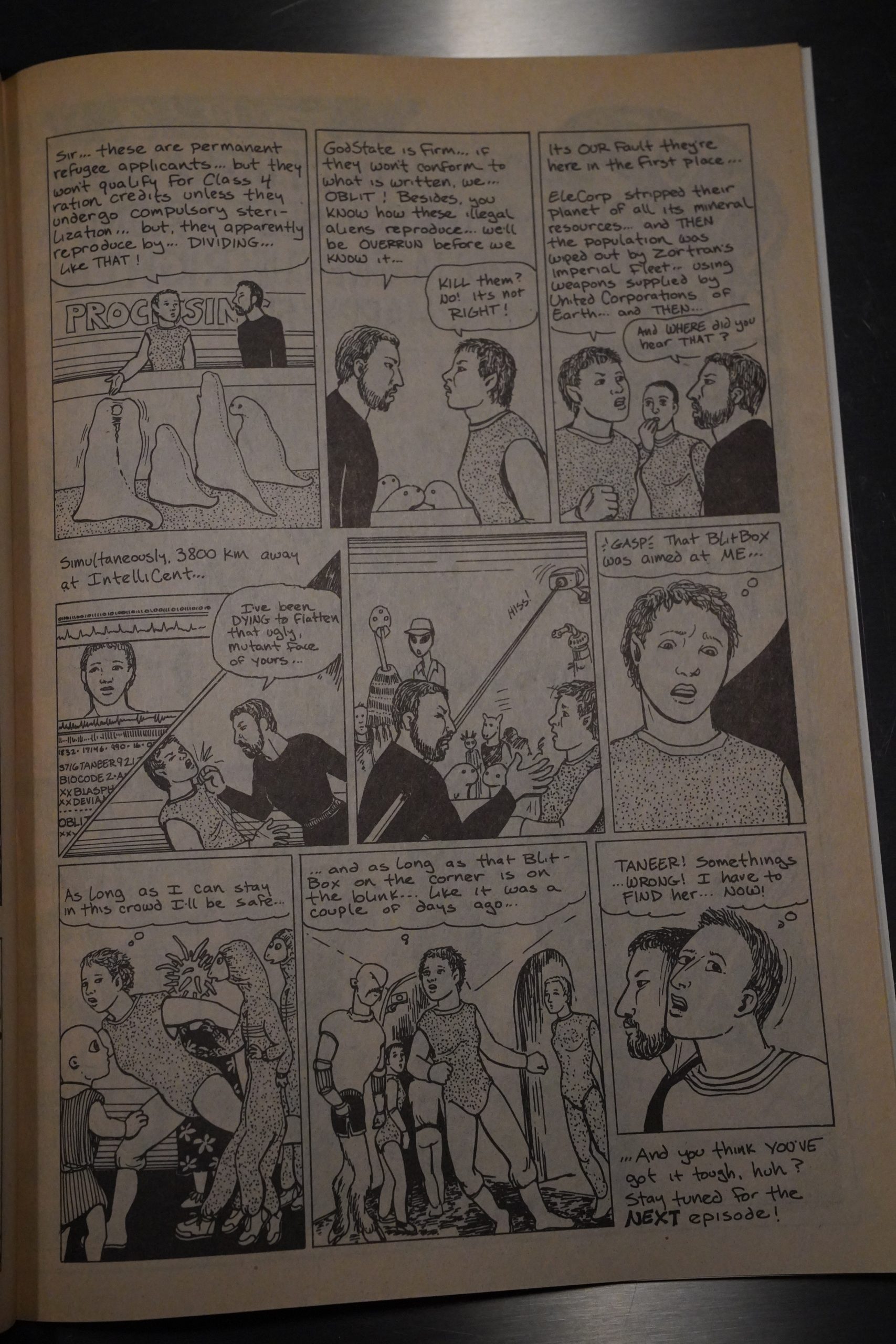

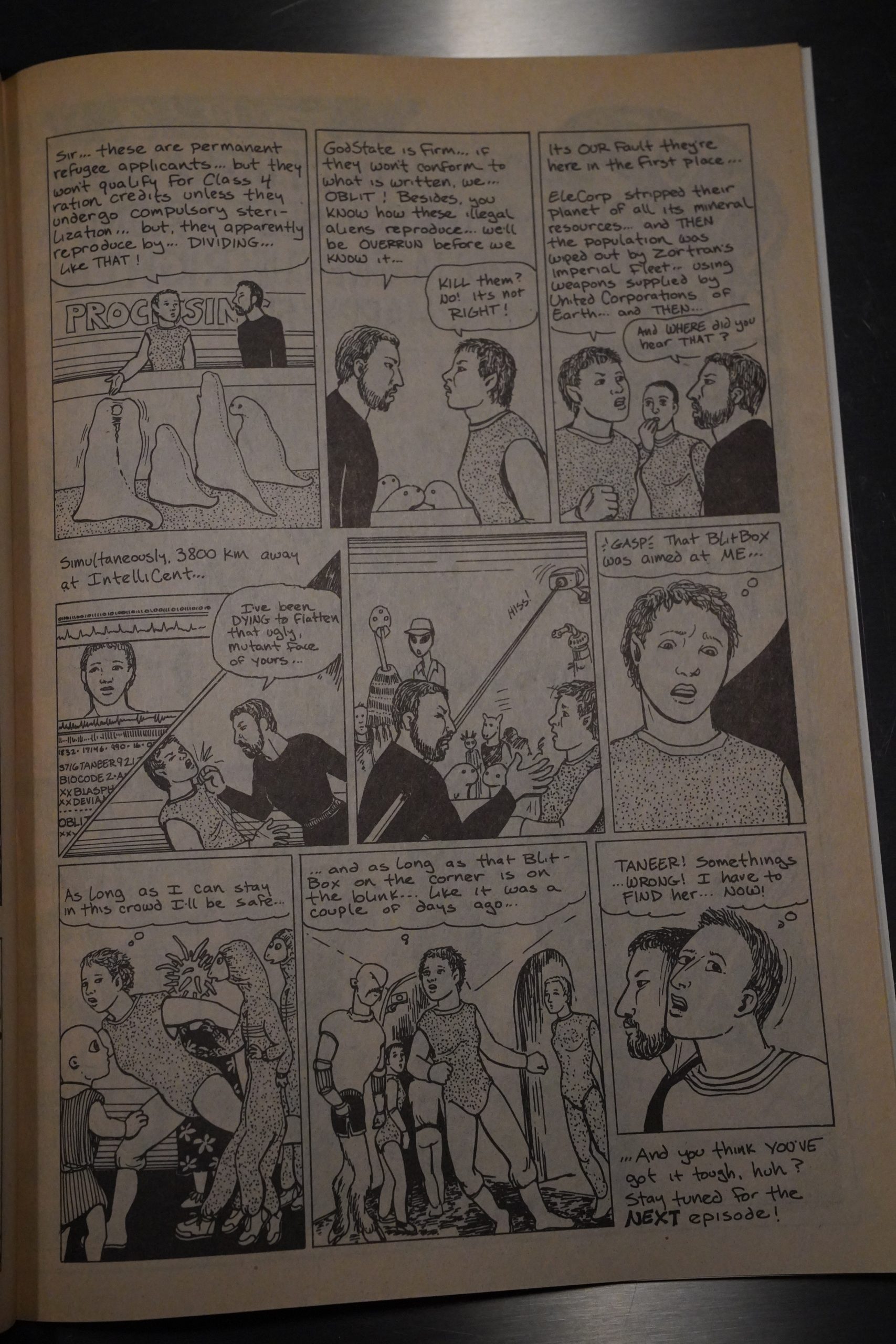

Roberta Gregory, for instance, shows up regularly, and… doing some sort of science fiction serial, and it’s fine.

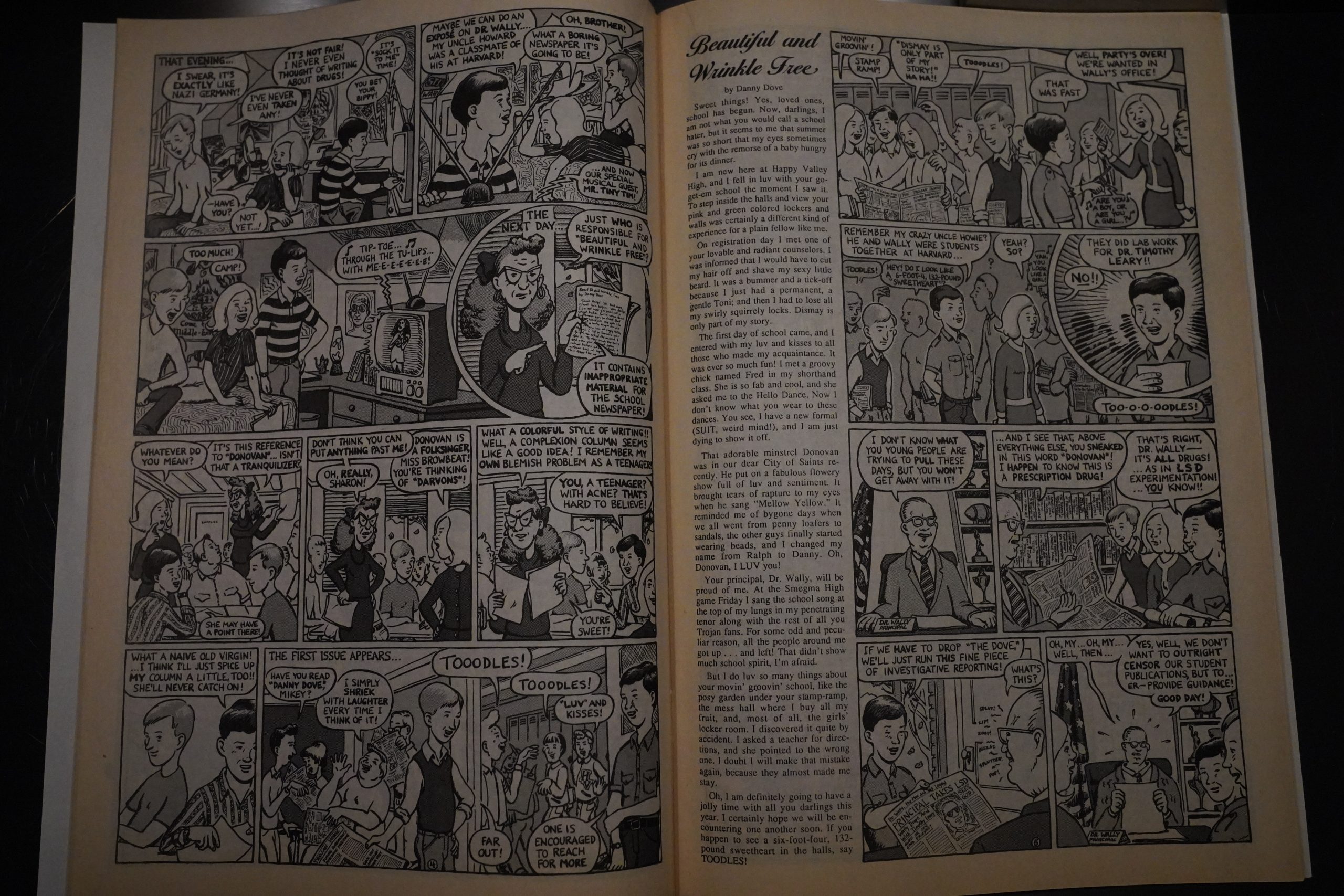

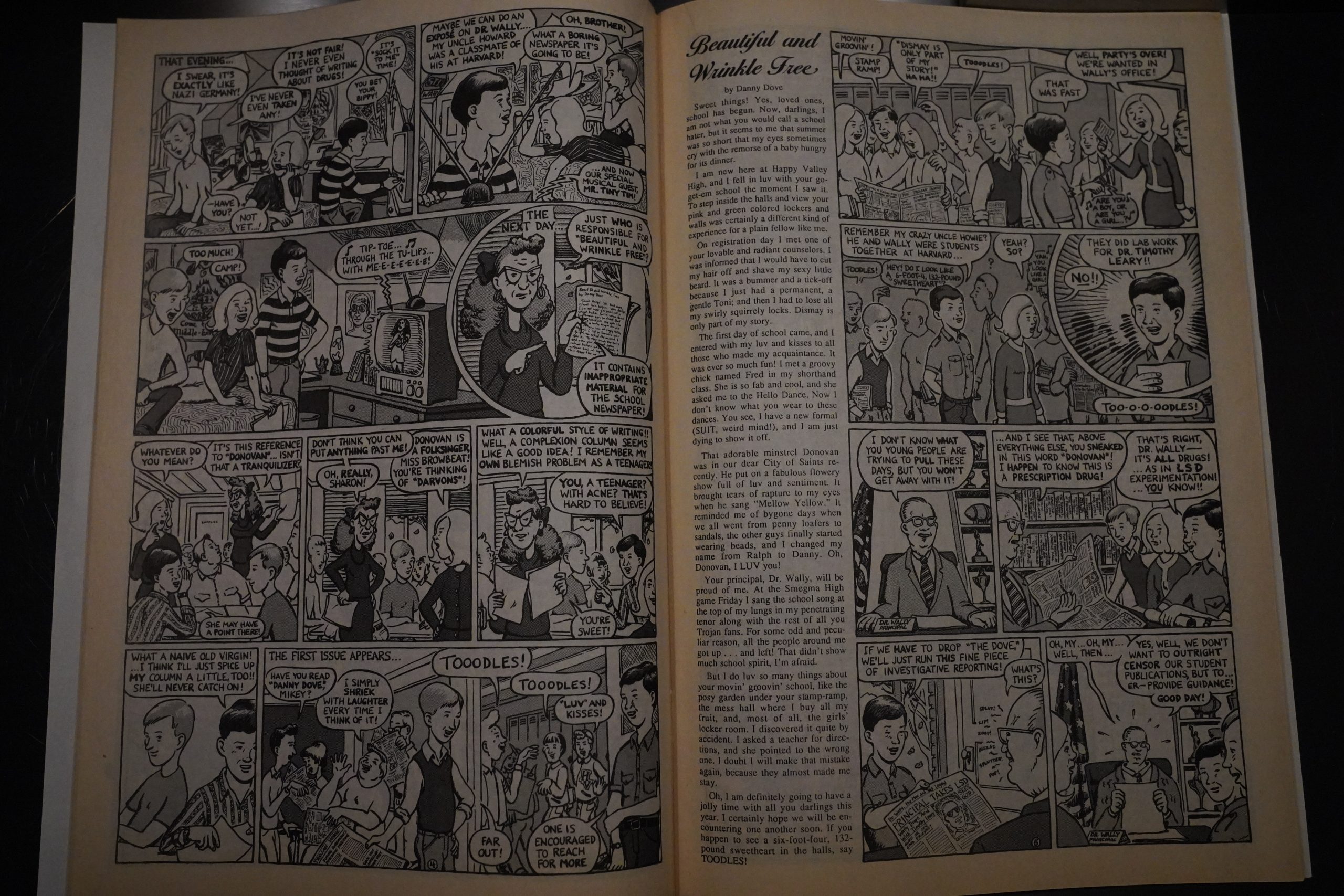

Triptow excerpts a bunch of columns he wrote in high school, and does an amusing semi-autobiographical story around how they came to be.

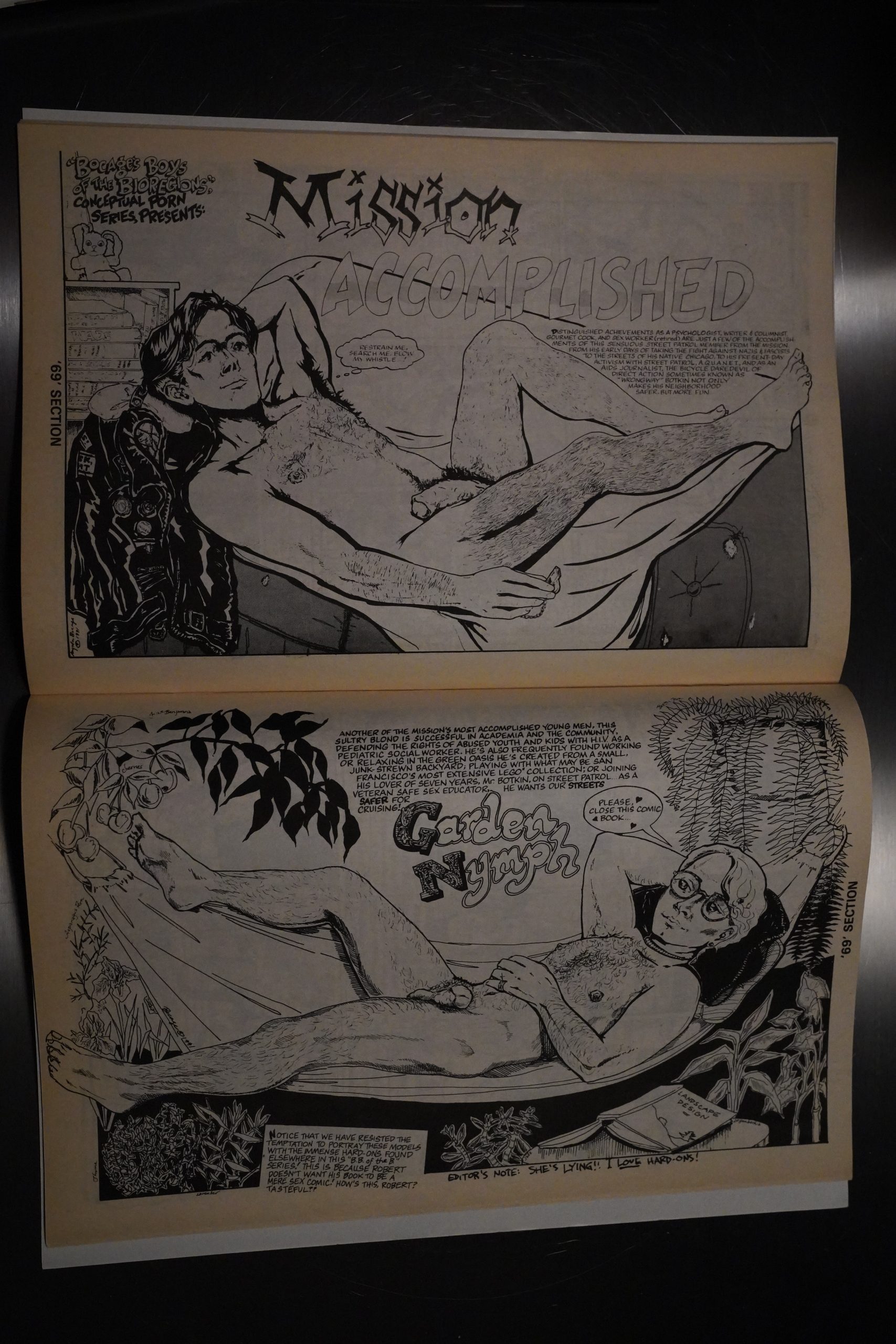

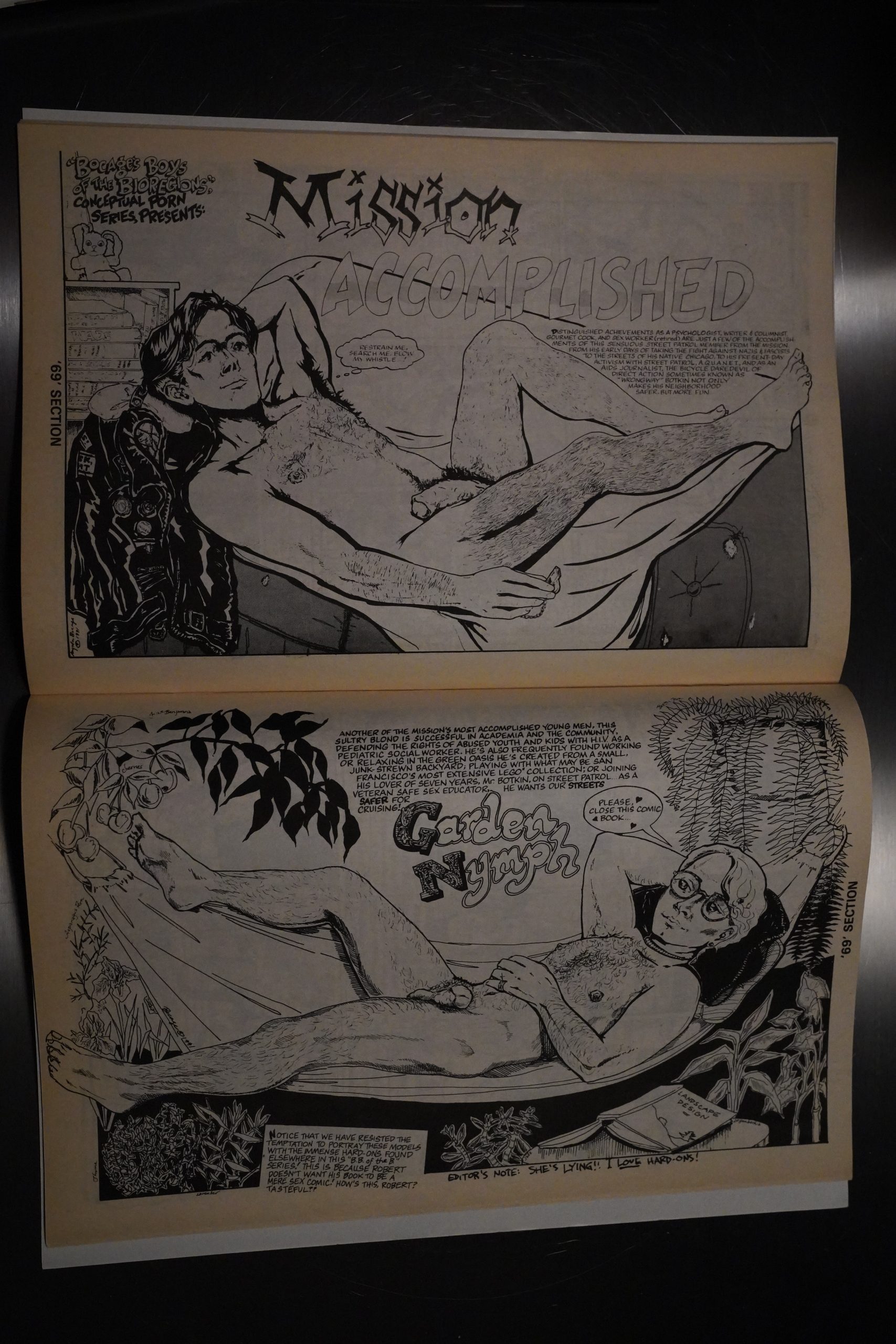

Heh. Angela Bocage’s conceptual porn series. And she says that Triptow has apparently mandated no erect penises, and indeed, I there has perhaps not been any since the book moved from Kitchen? I haven’t been keeping track.

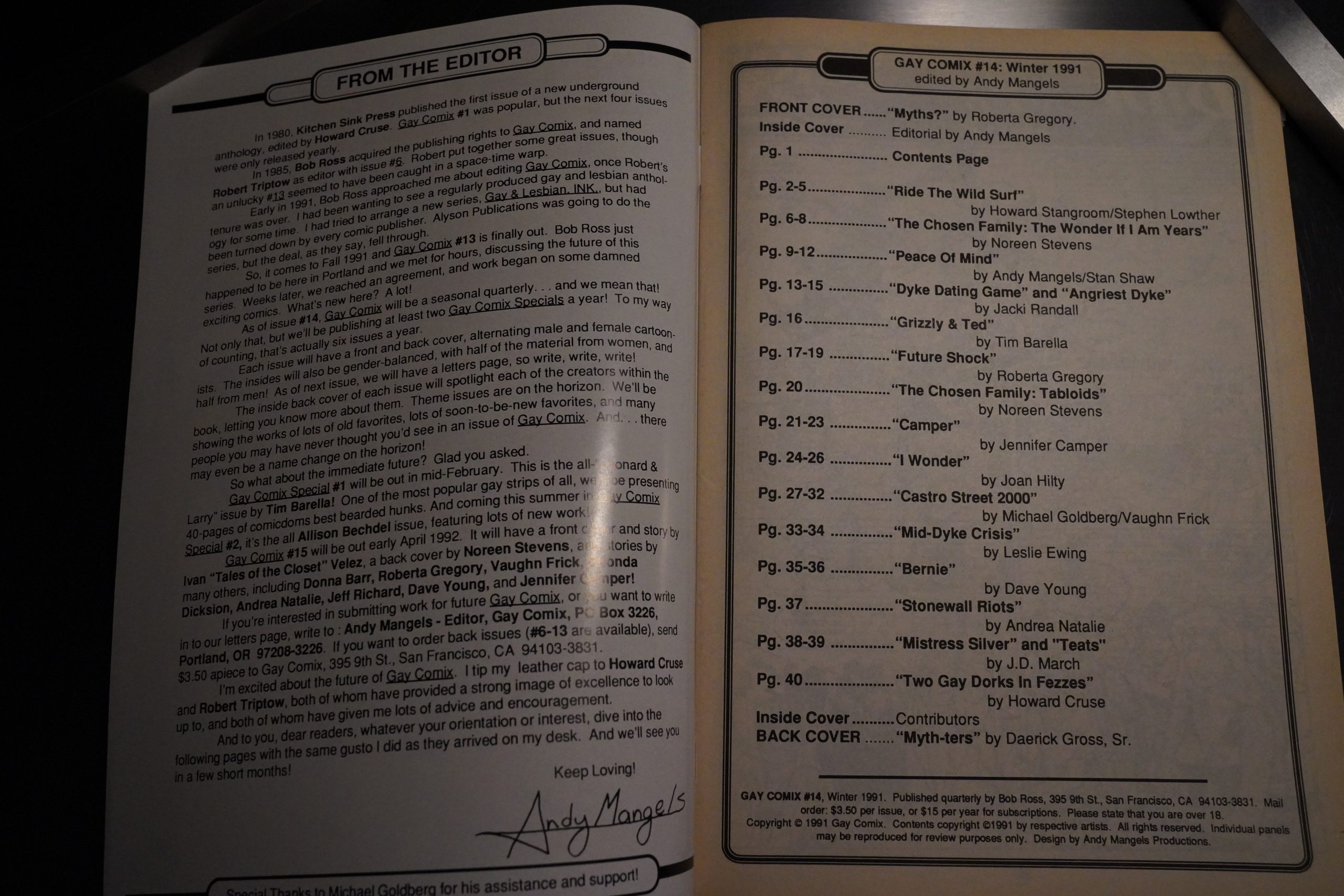

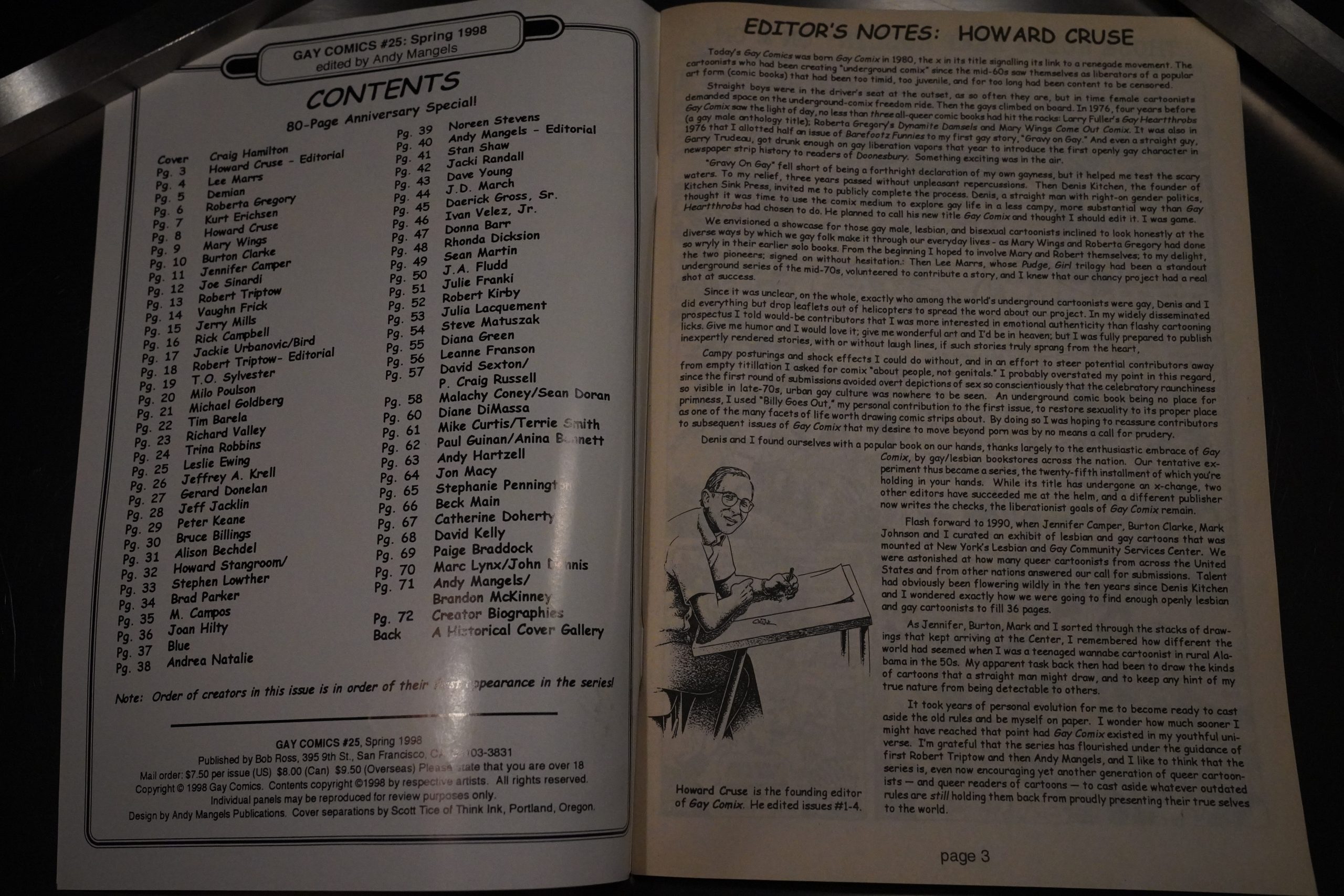

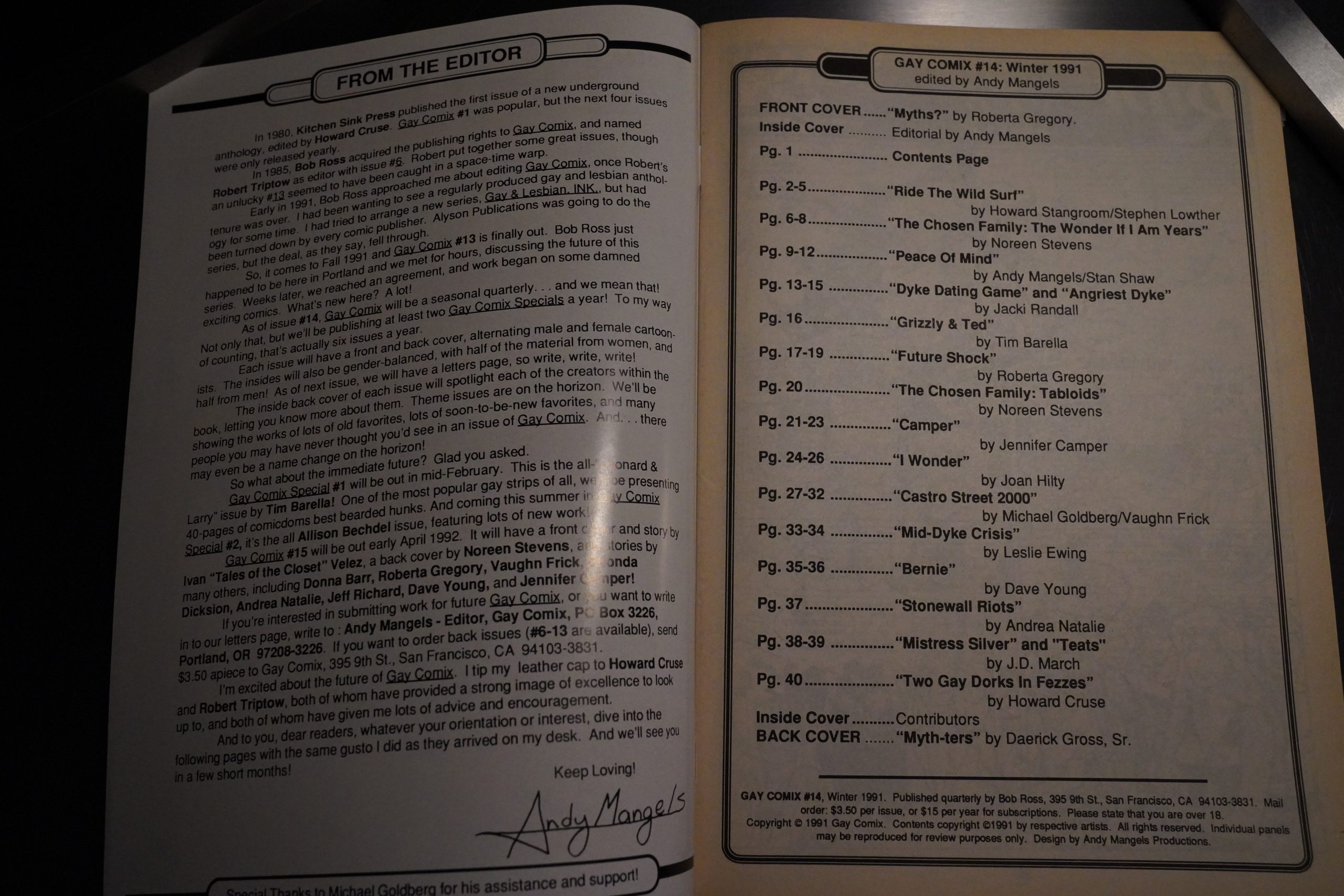

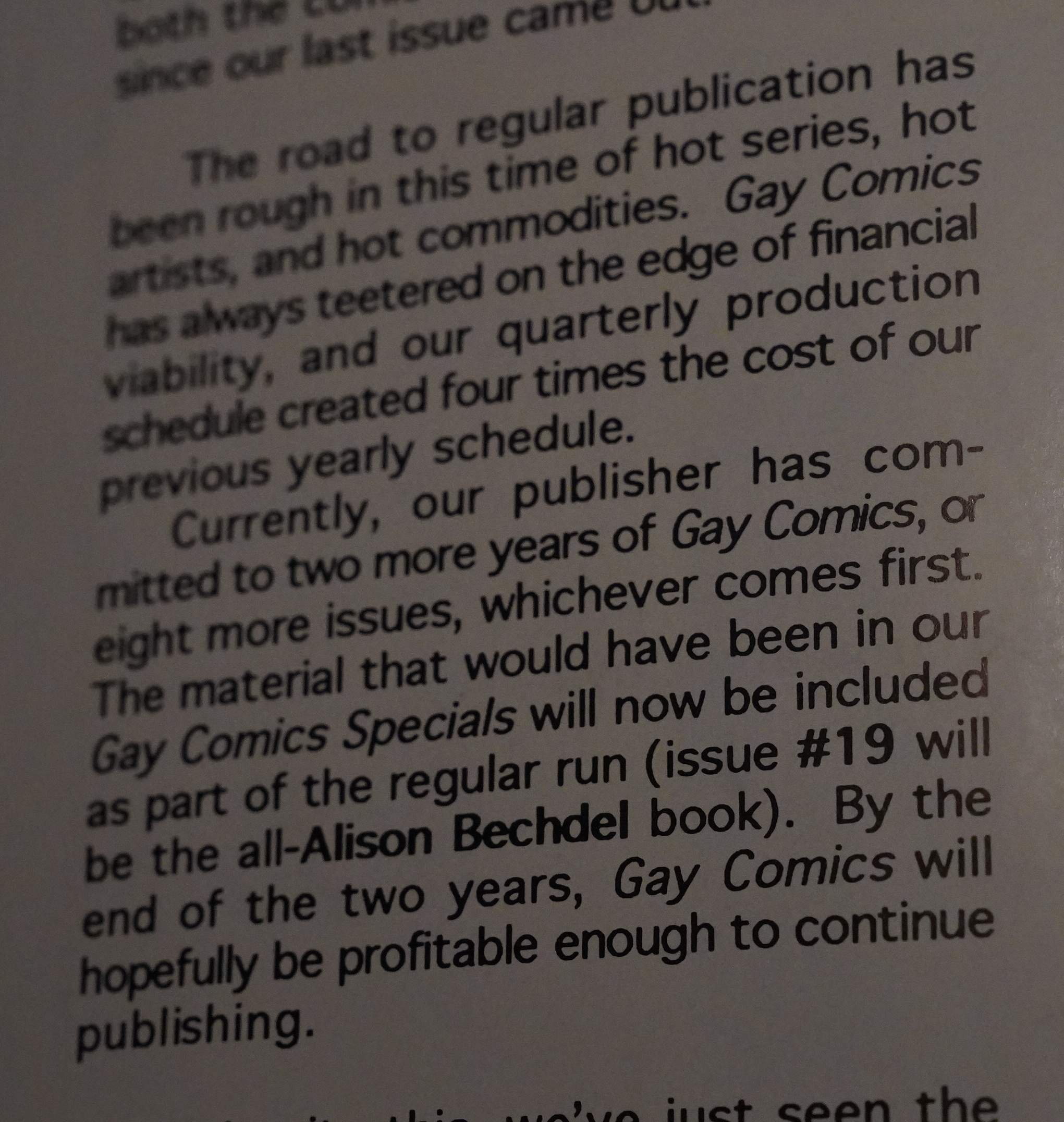

#13 was published in 1988, and then there was a three year hiatus before #14. And with a new editor — Andy Mangels, who brings a fresh enthusiasm (and an actual contents page: Shocker!) And… er… not much of a sense of design, I guess.

We’re promised a quarterly schedule (for real this time around), and two specials per year. The publisher is still the same: Bob Ross.

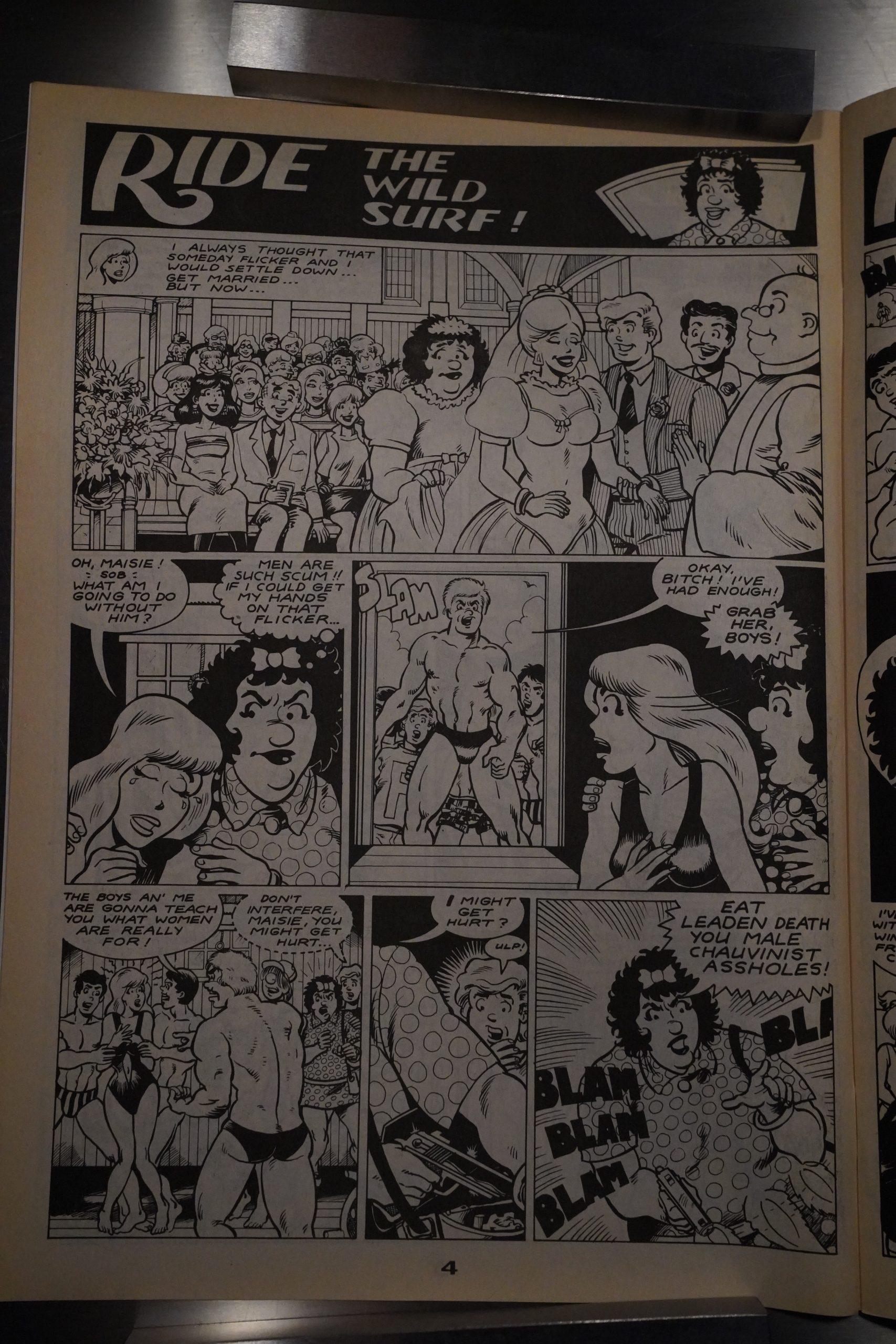

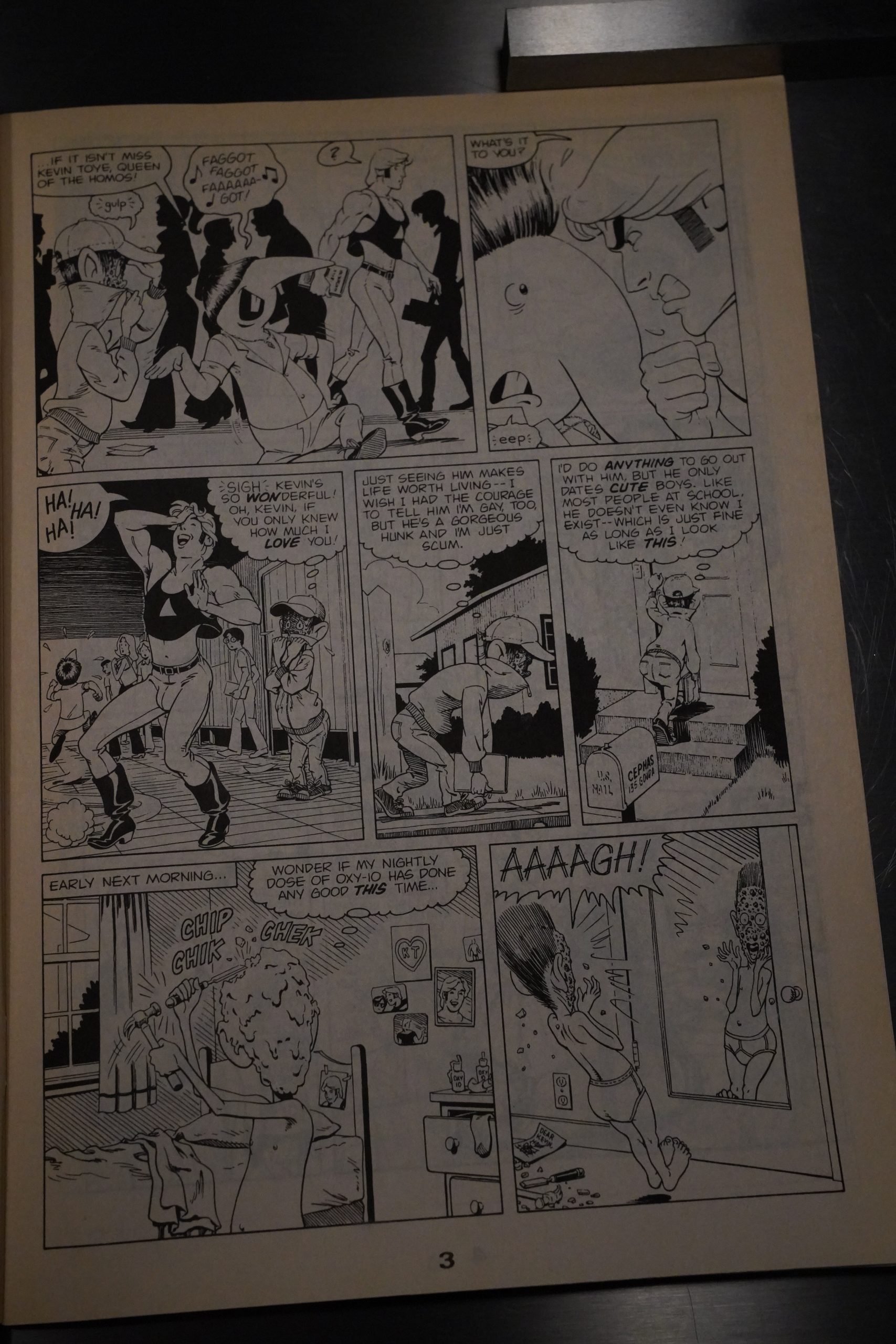

How would the contents change under the new management (and a new decade)? The first new issue is pretty similar to previous issues: It’s mostly comedy stuff, like this Archie parody by Howard Stangroom and Stephen Lowther. It’s pretty spot on, eh?

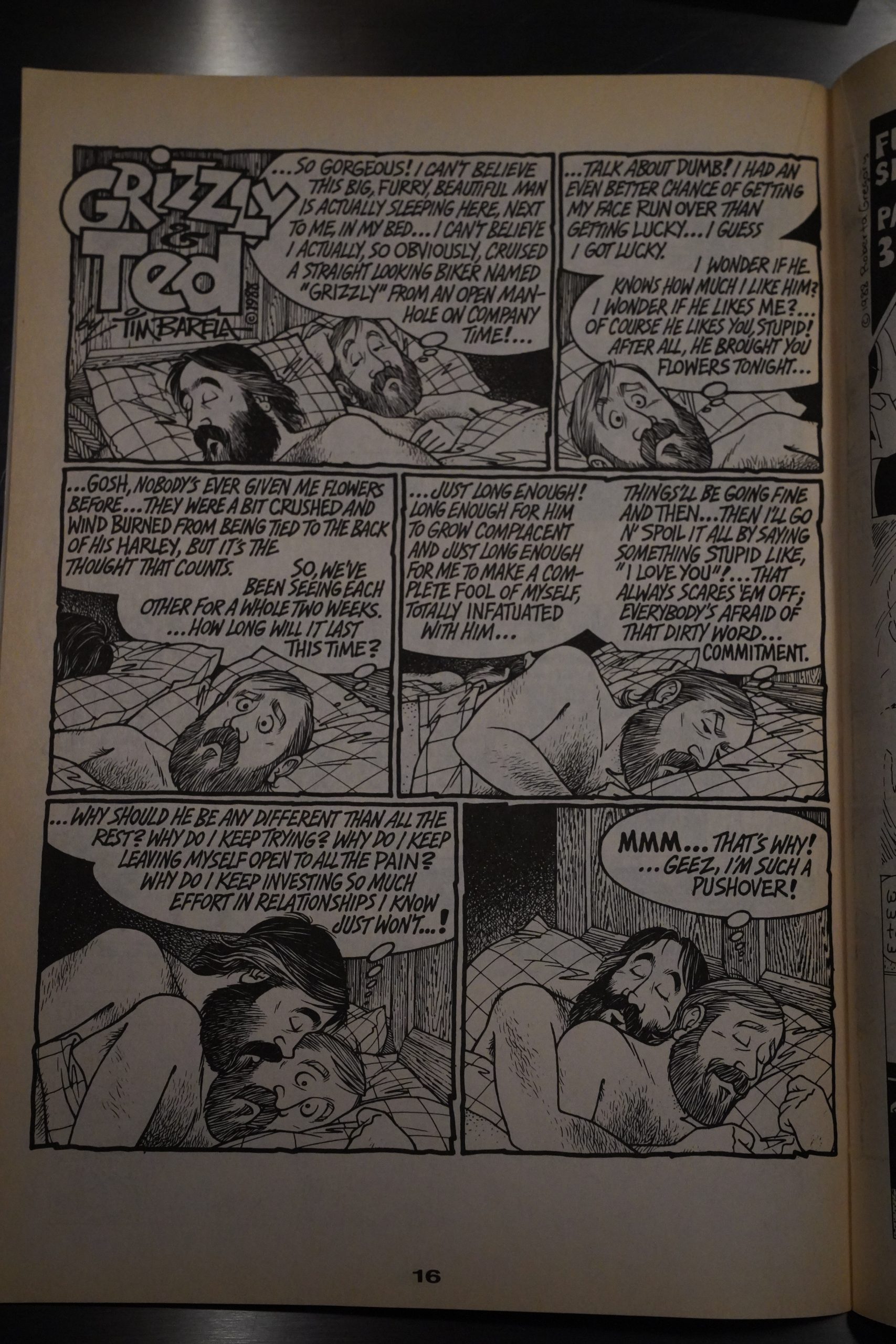

Did Leonard grow a beard and both change their names? No, it’s Tim Barela’s penchant for drawing only a single face (but alternately bearded or not).

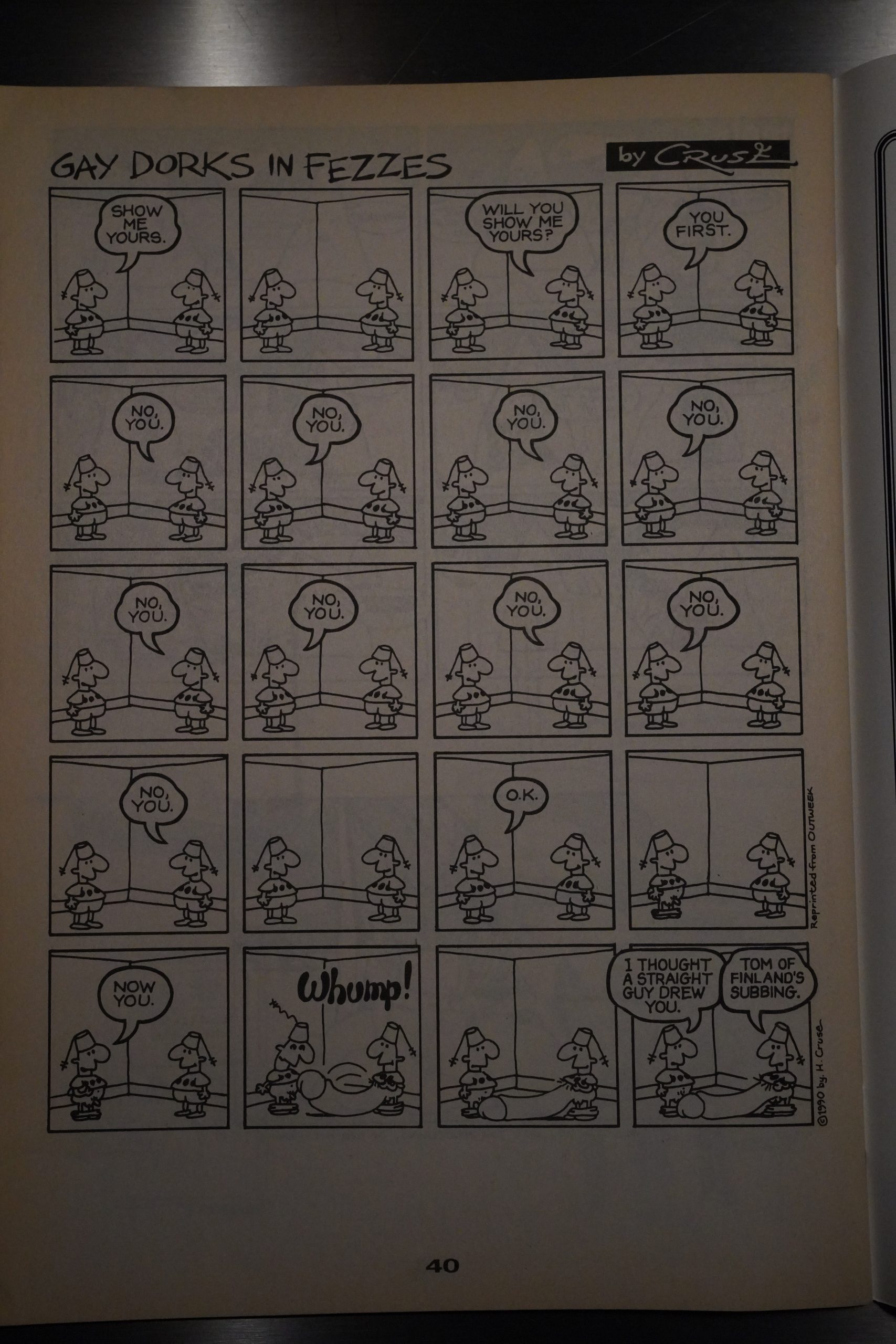

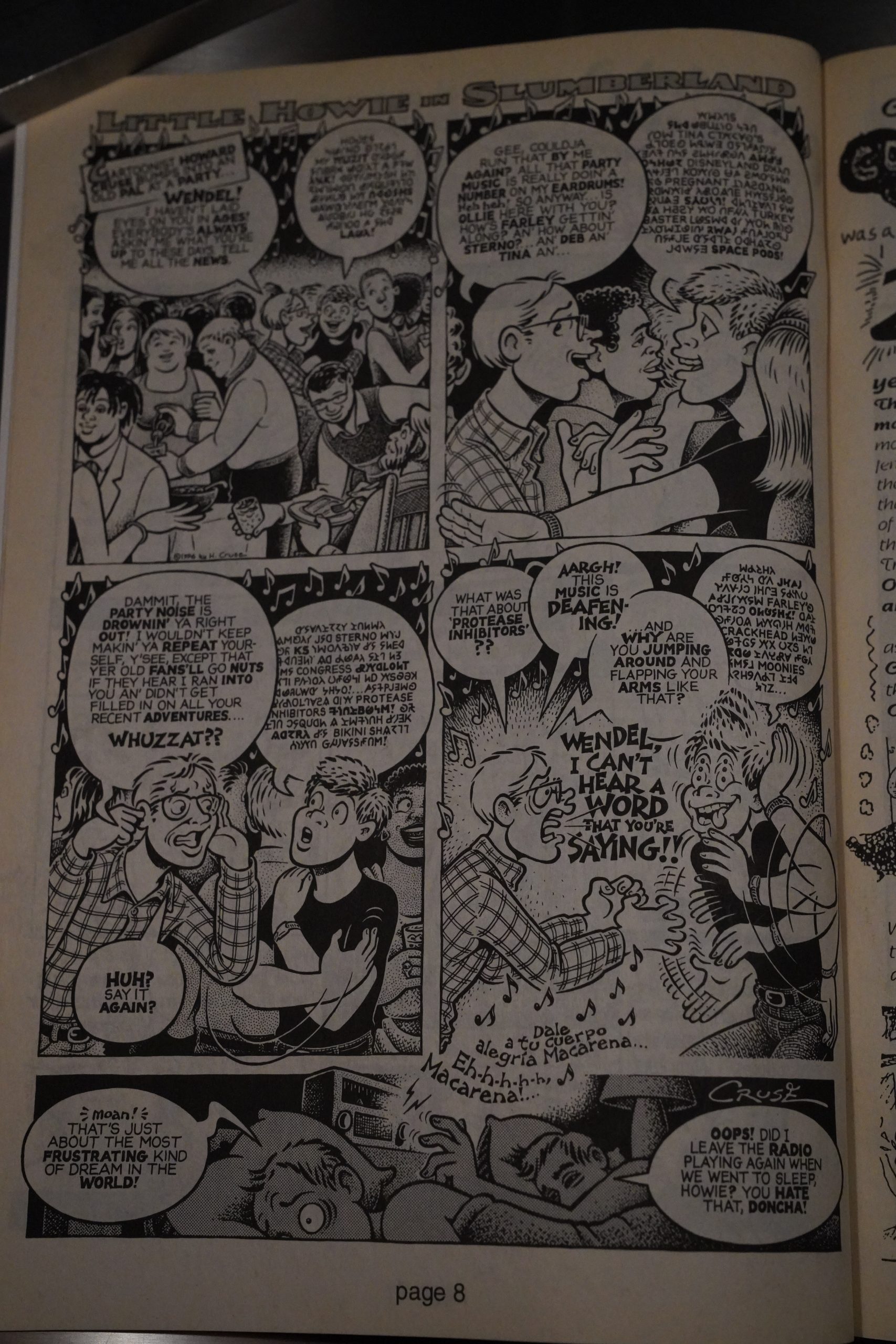

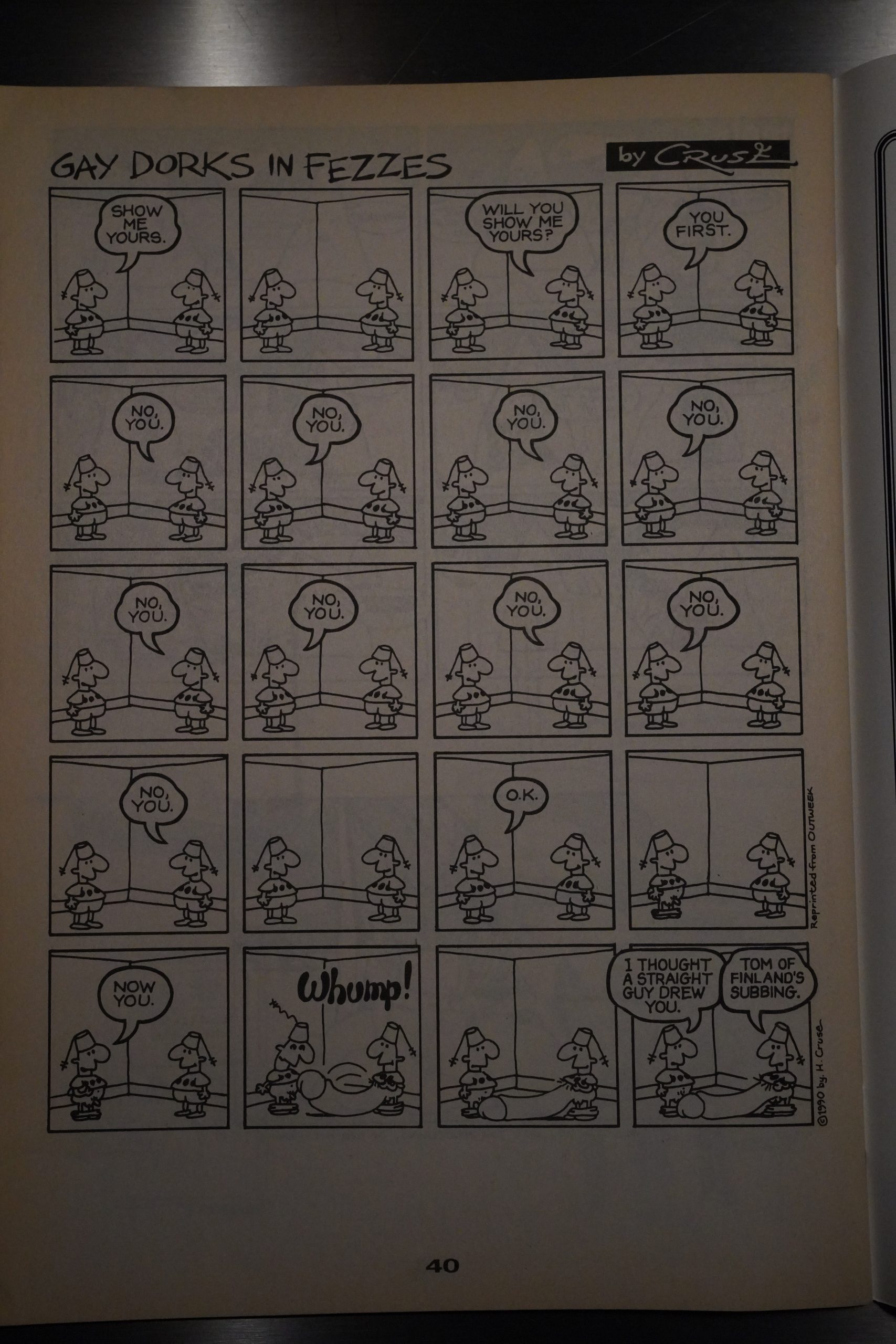

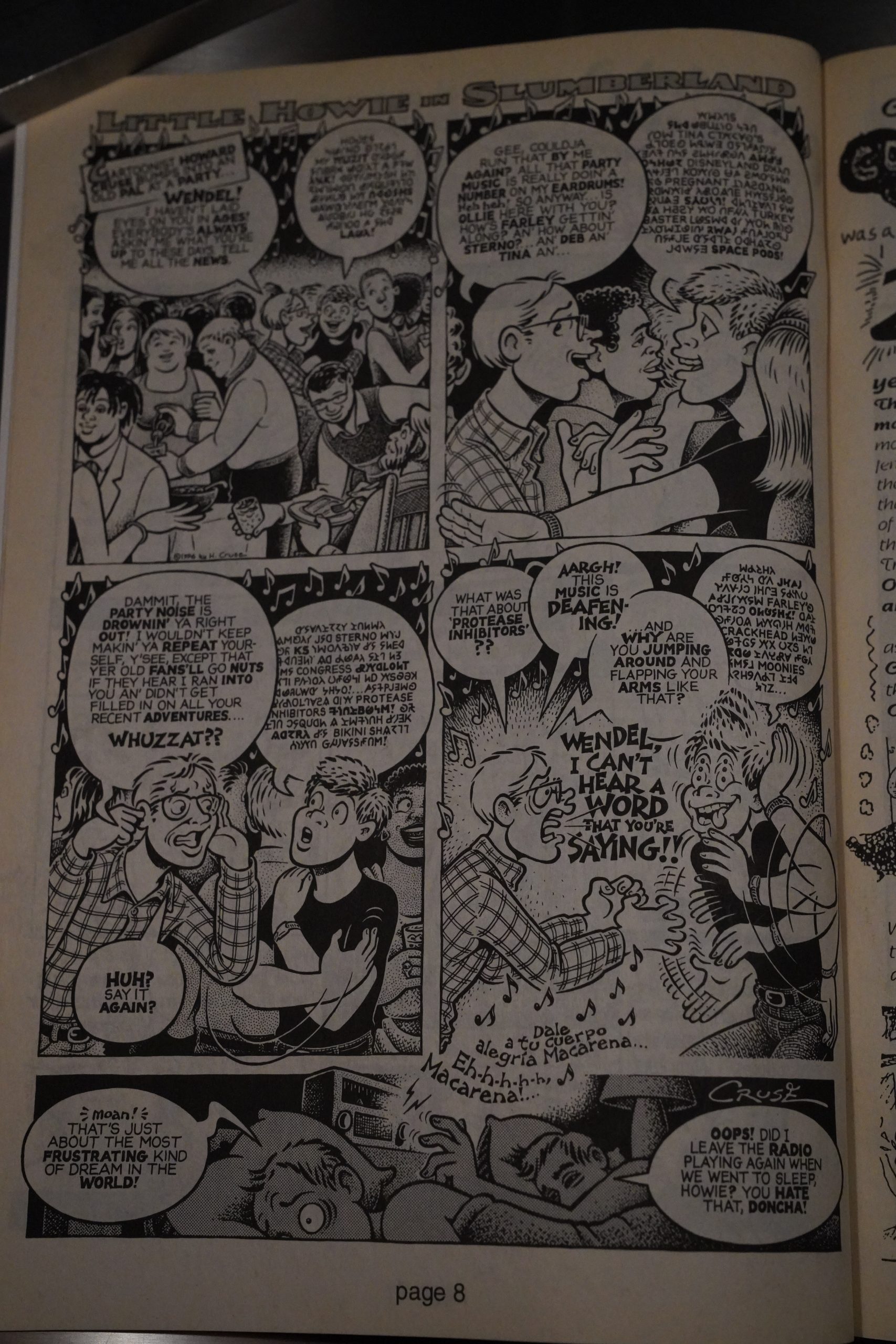

Wow! I didn’t remember this Howard Cruse parody of Matt Groening’s Akbar & Jeff.

By the second Mangels book, it’s clear that he has a pretty different editorial direction than Triptow. Gone are basically all the sitcom-like series, and instead we get a mixture of humorous bits and more angsty stuff like Ivan Velez.

(And the series changed name from Gay Comix to Gay Comics.)

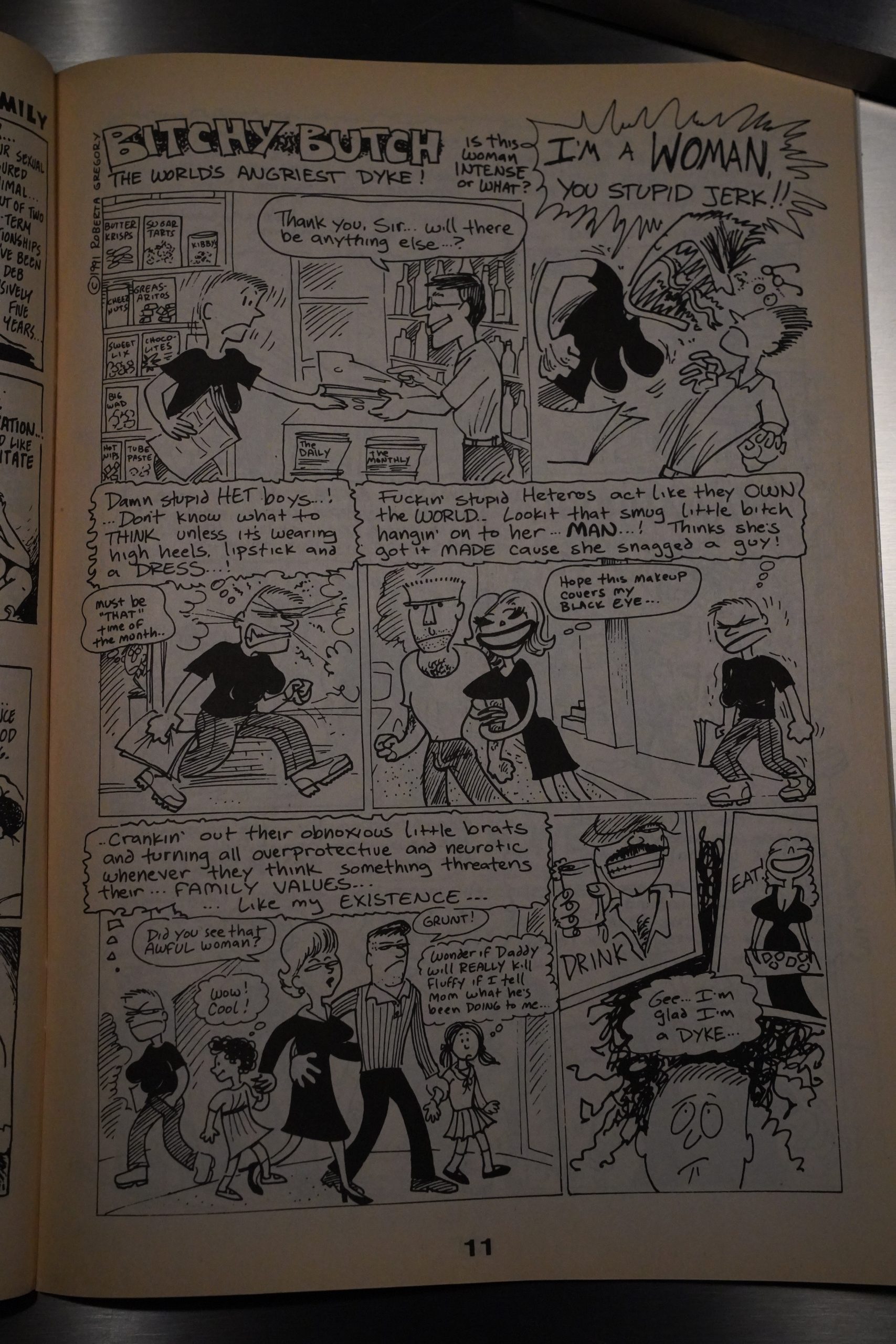

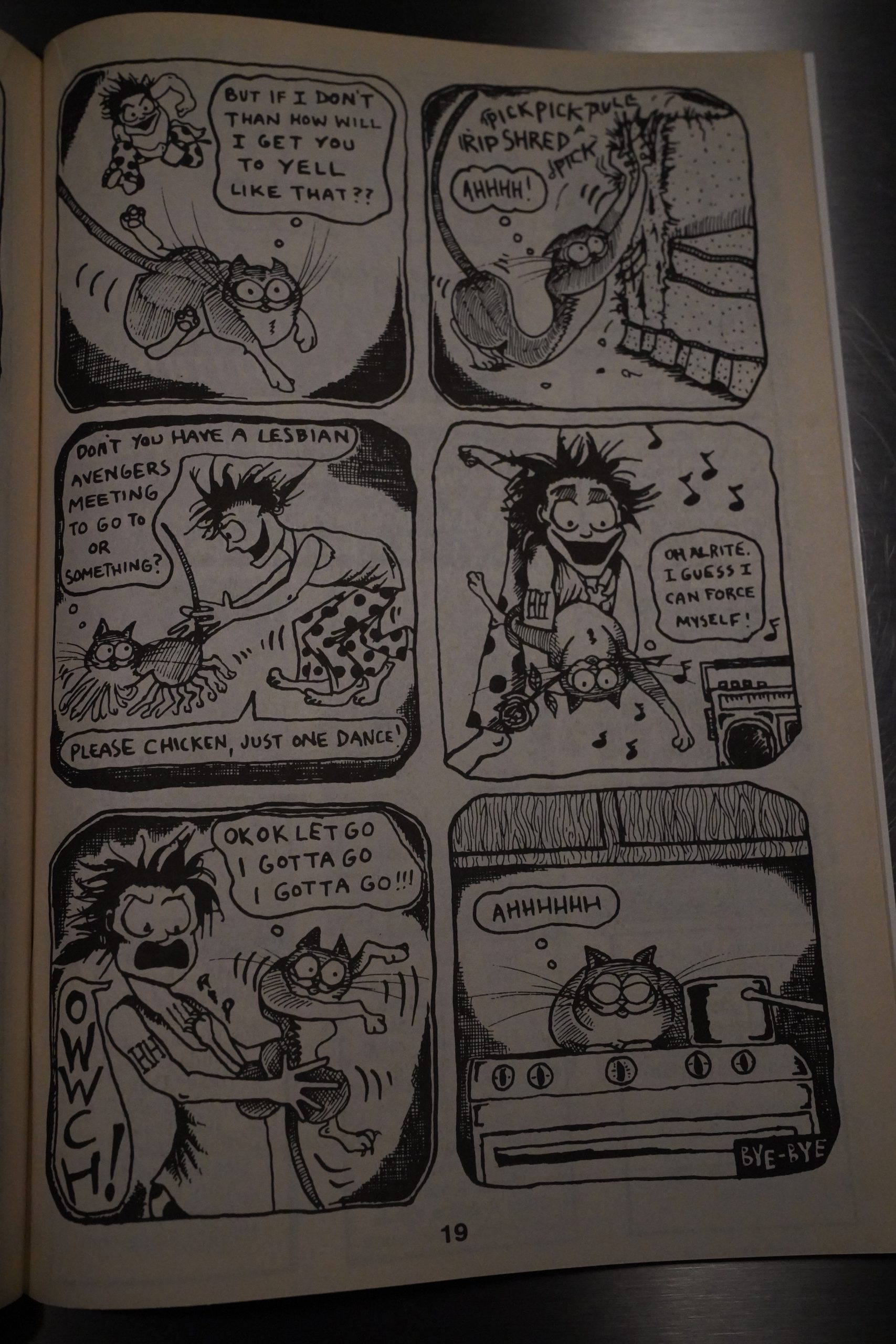

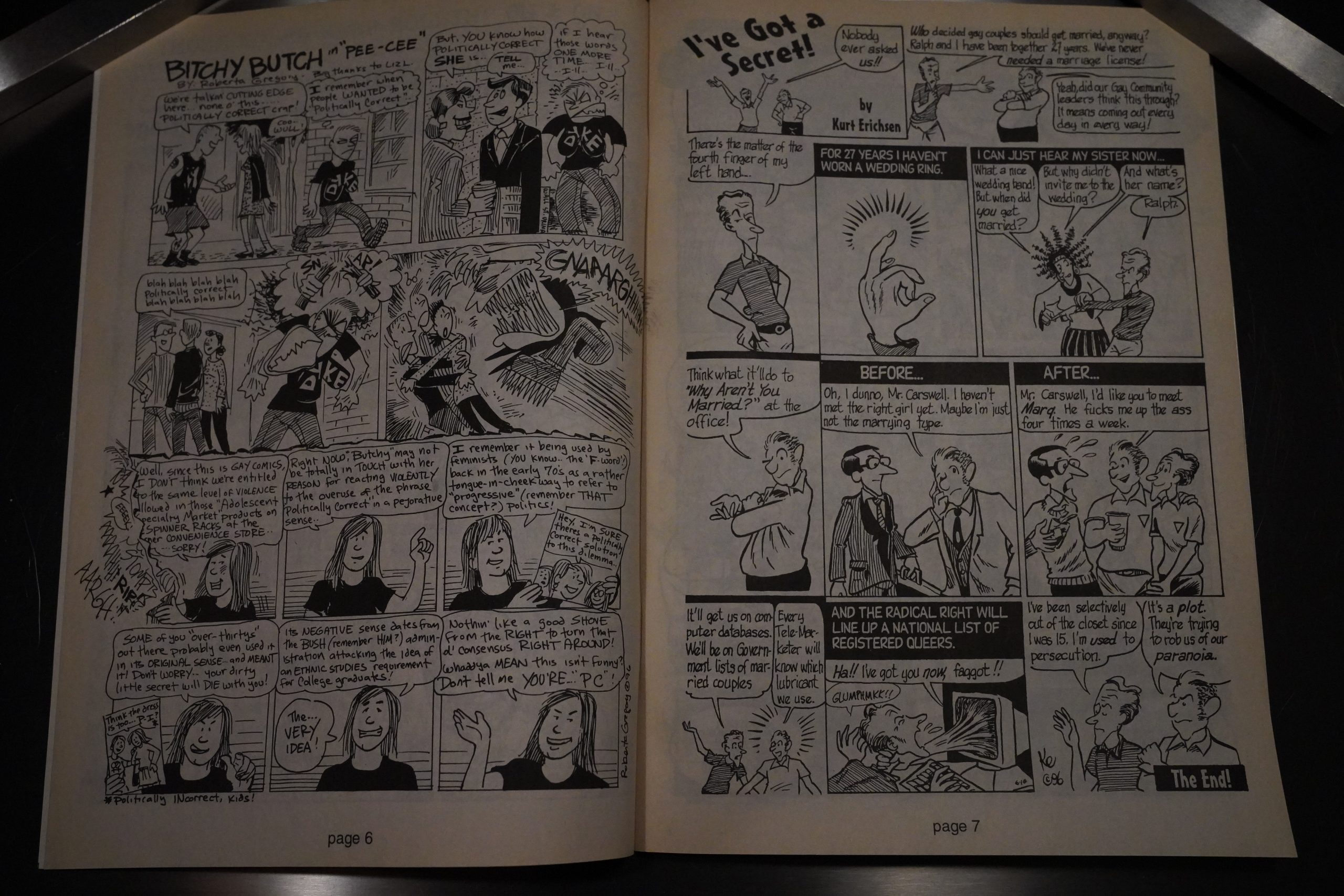

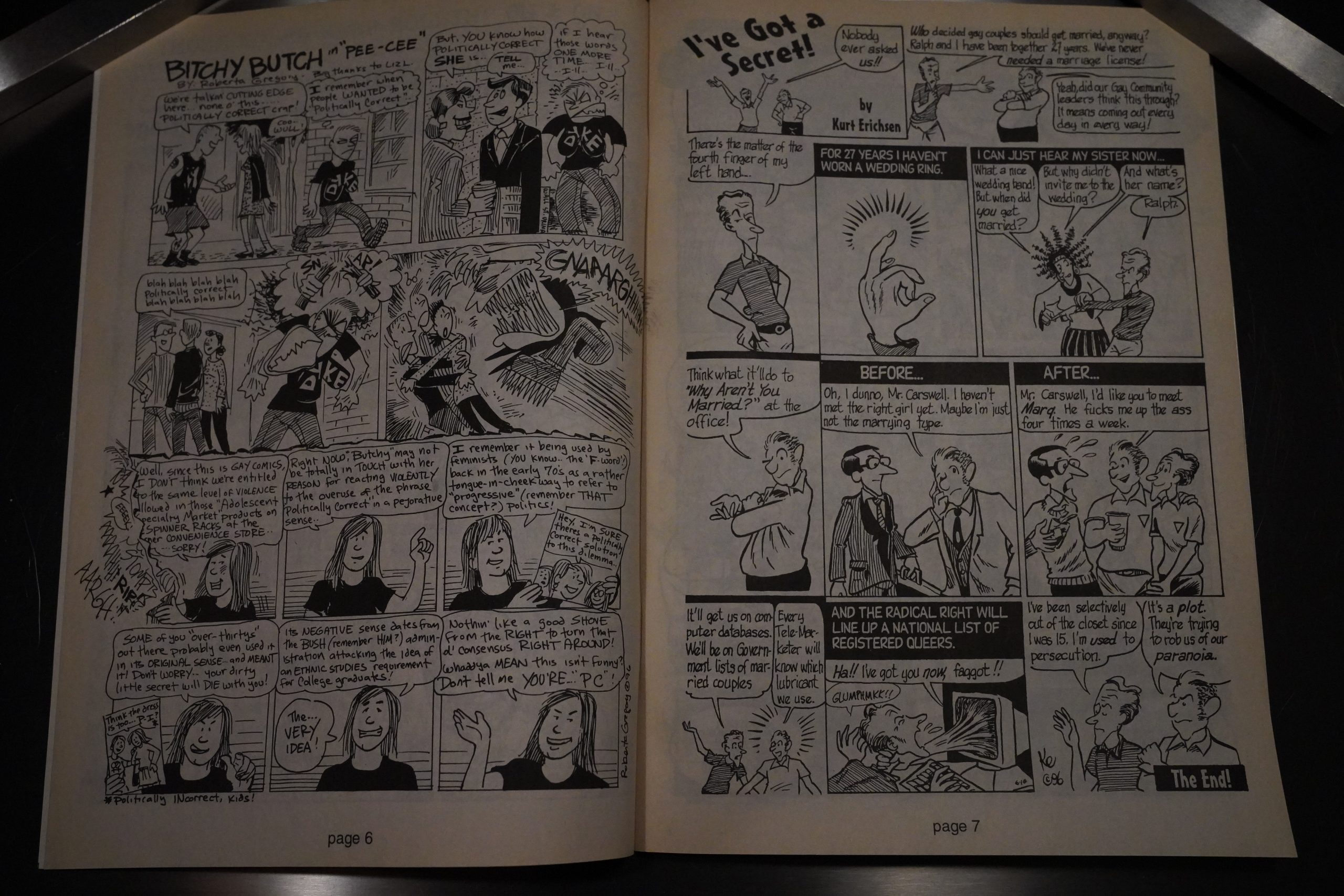

And Roberta Gregory drops by with a prime Bitchy Butch piece. Gay Comics is getting back to its roots, basically.

That’s not to say that it’s all fantastic — at least a third of each issue is pretty… er… er… How to put it… OK, just read the above yourselves.

Donna Barr drops by with a little thing about some of her gay friends… it’s cute.

The first of the specials we’re threatened with, I mean, promised, is a Leonard & Larry collection of strips that had run elsewhere, apparently.

I remember quite liking these strips when I read them back in the day? But I find them a slog to get through now. The verbiage just isn’t that amusing, and there’s usually no payoff that outweighs spending this much time on a page (as a reader).

And Barela does have a pretty attractive line. It’s just so aggressively samey. All the characters have bobble heads (but then again, we usually don’t see anything but their heads because of the verbiage), and all the men look identical. OK, he has two types — one with a beard and one with a stache, but it’s unrelenting. I mean, just look at those three guys with the staches? What the fuck? It’s not like it’s a commentary on Castro Clones, either. And what’s with all those open mouths? Sure, everybody’s talking All The Time, but do they have to do O face all the time, too?

OK, back to the regular series… I really enjoyed this autobio strip from Roberta Gregory. It’s very calm.

Editor Mangels writes this very confused superhero thing (illustrated by J. A. Fludd), and it’s like a headache on paper.

It sounds like the publisher is way more supportive than most comics publishers are — they guarantee they’ll be publishing the book for a couple more years, which is pretty unusual. (But the specials will be folded into the series, so we’re getting the Bechdel book after all.)

Eric Shanower! The people contributing to the book at is point are mostly definitely not mainstream names, but Shanower is pretty major.

That’s so accurate. I’ve tried to stay true to that principle my entire life.

But as I was saying, about half the contents of each issue seems to be from people (I guess) that have little experience doing comics. I’m guessing the editor didn’t really do much editing, but it’s also probably down to having things to choose between. Four forty page issues a year is a lot.

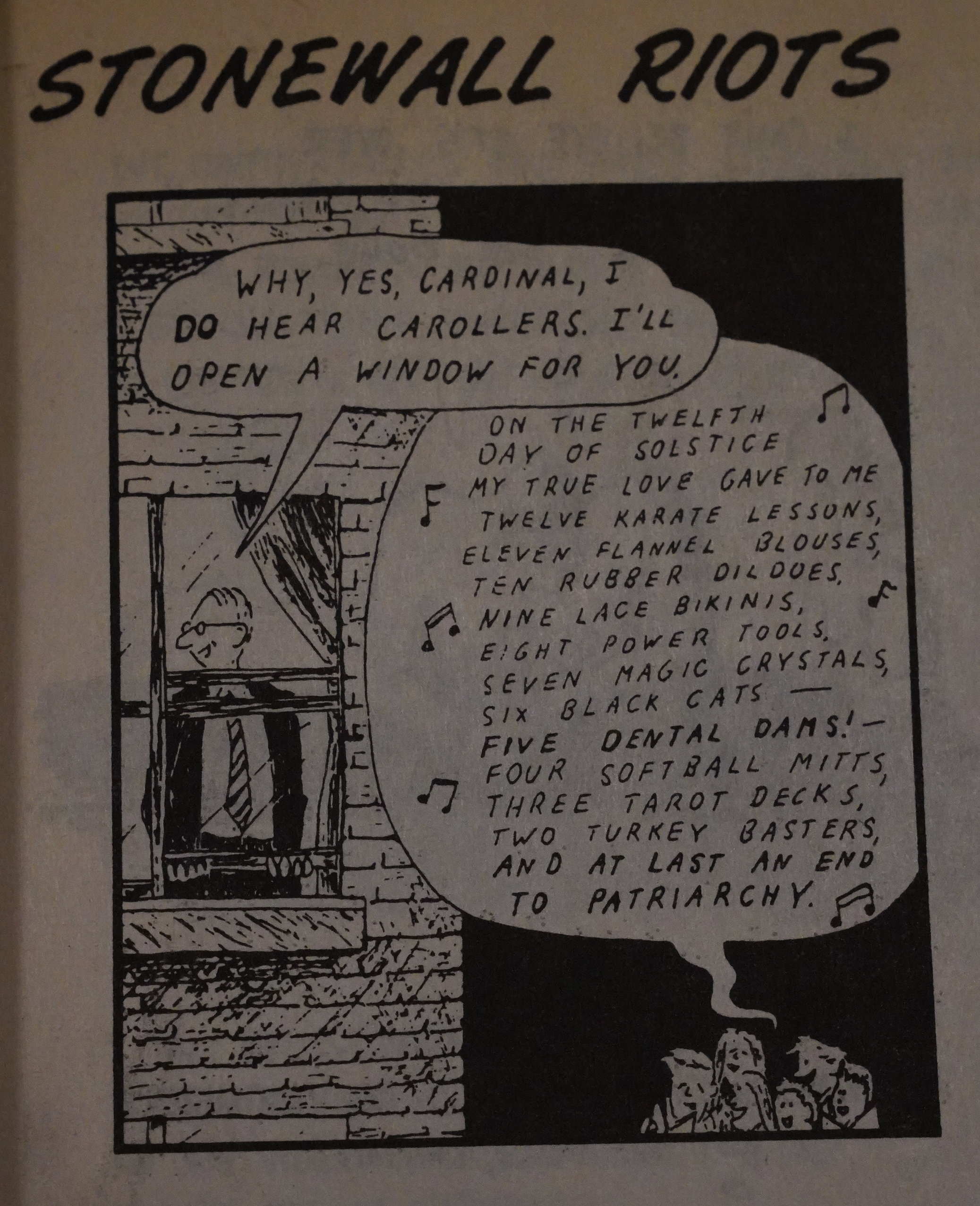

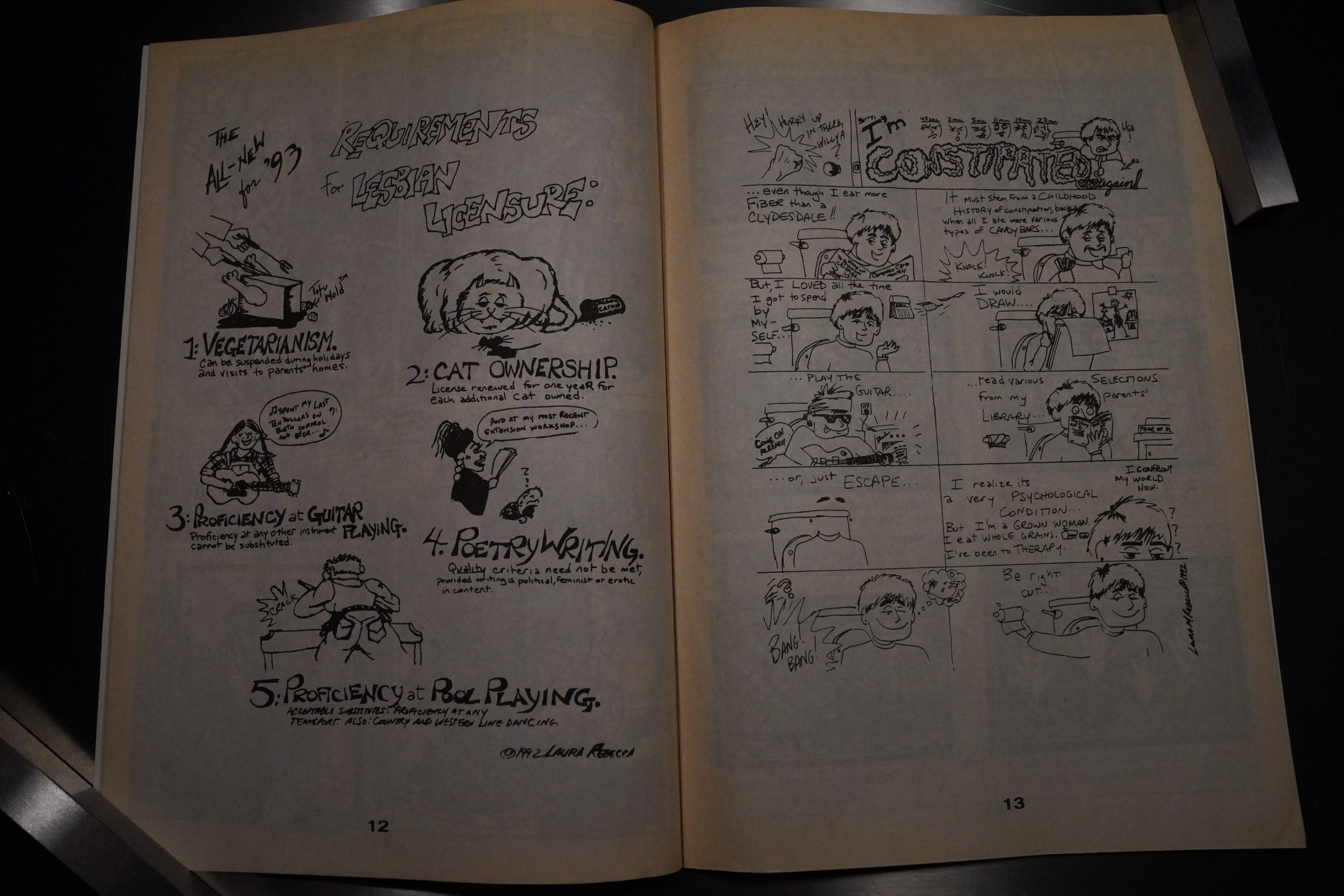

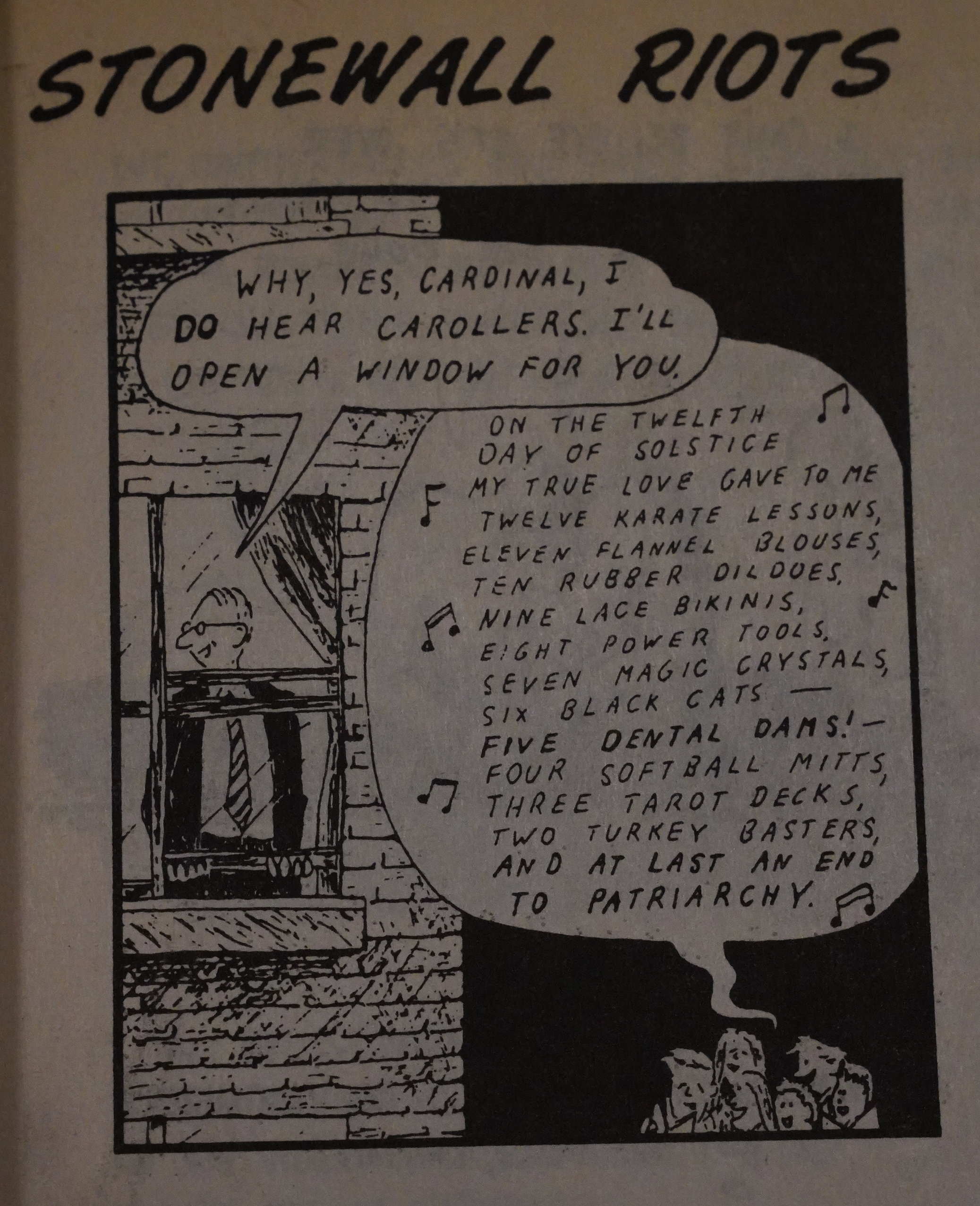

Hey, that scans pretty well. (Andrea Natalie.)

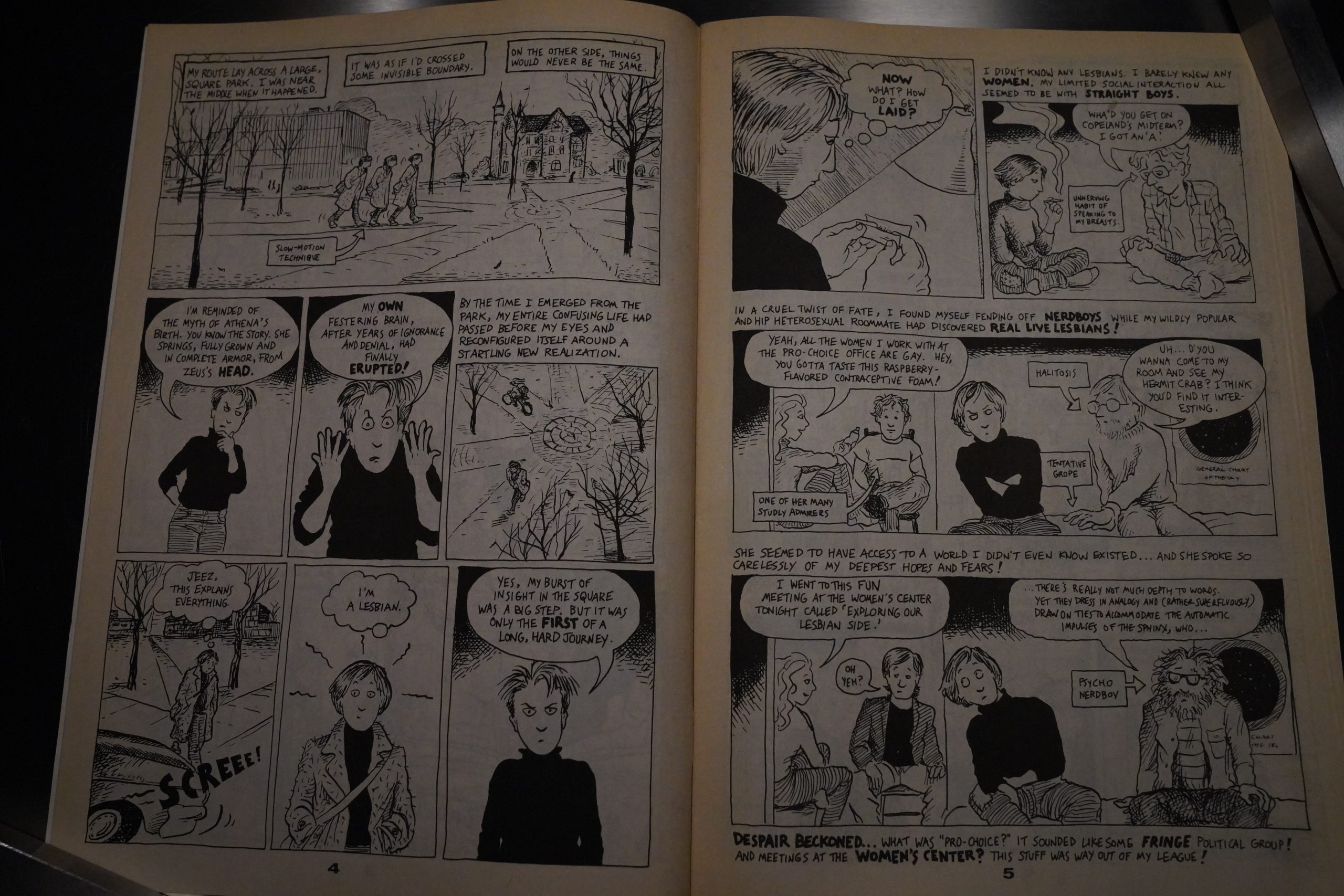

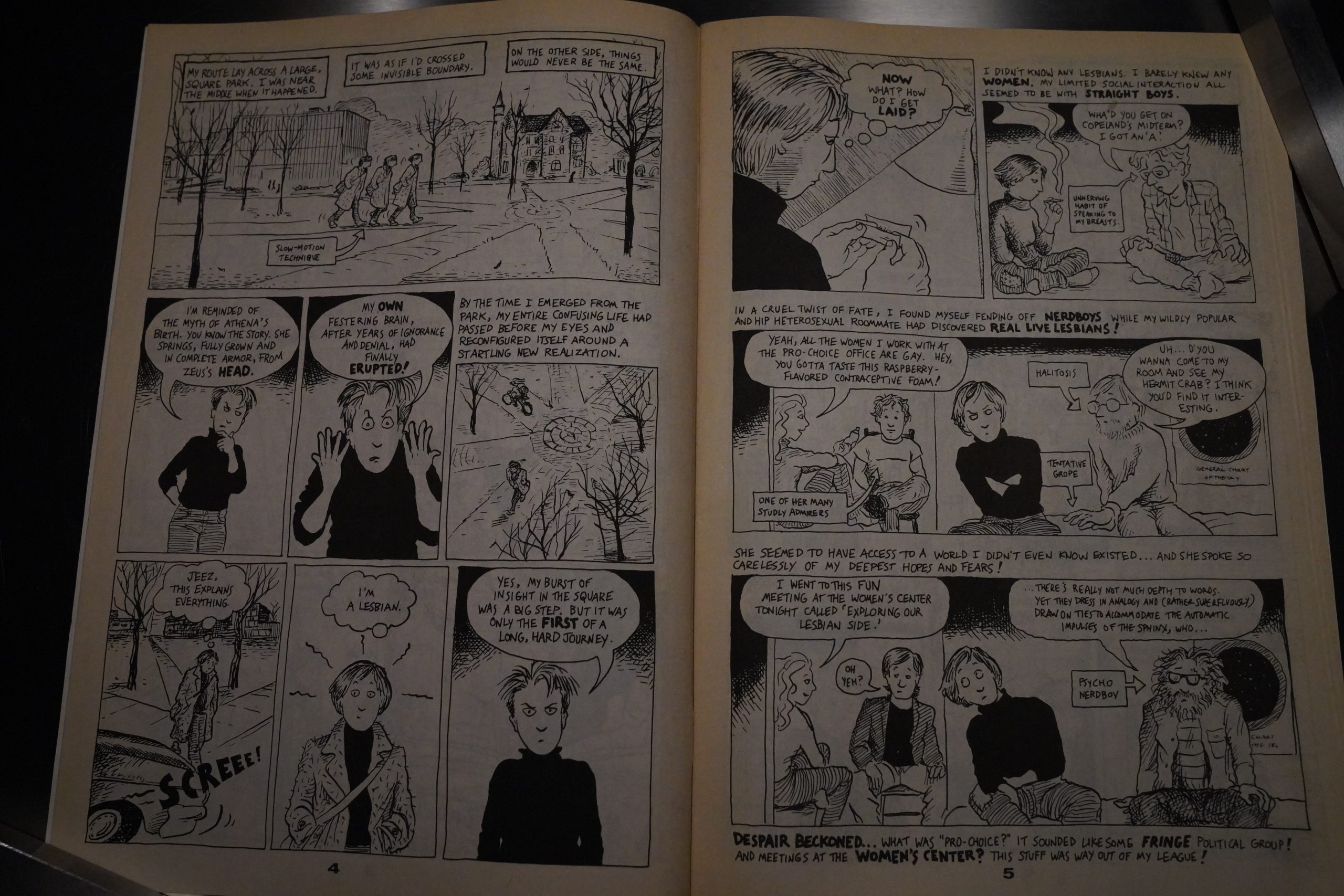

Finally we get the long-promised Alison Bechdel issue, and it’s fantastic. We get more than 20 brand new autibio pages, where the first one is about coming out…

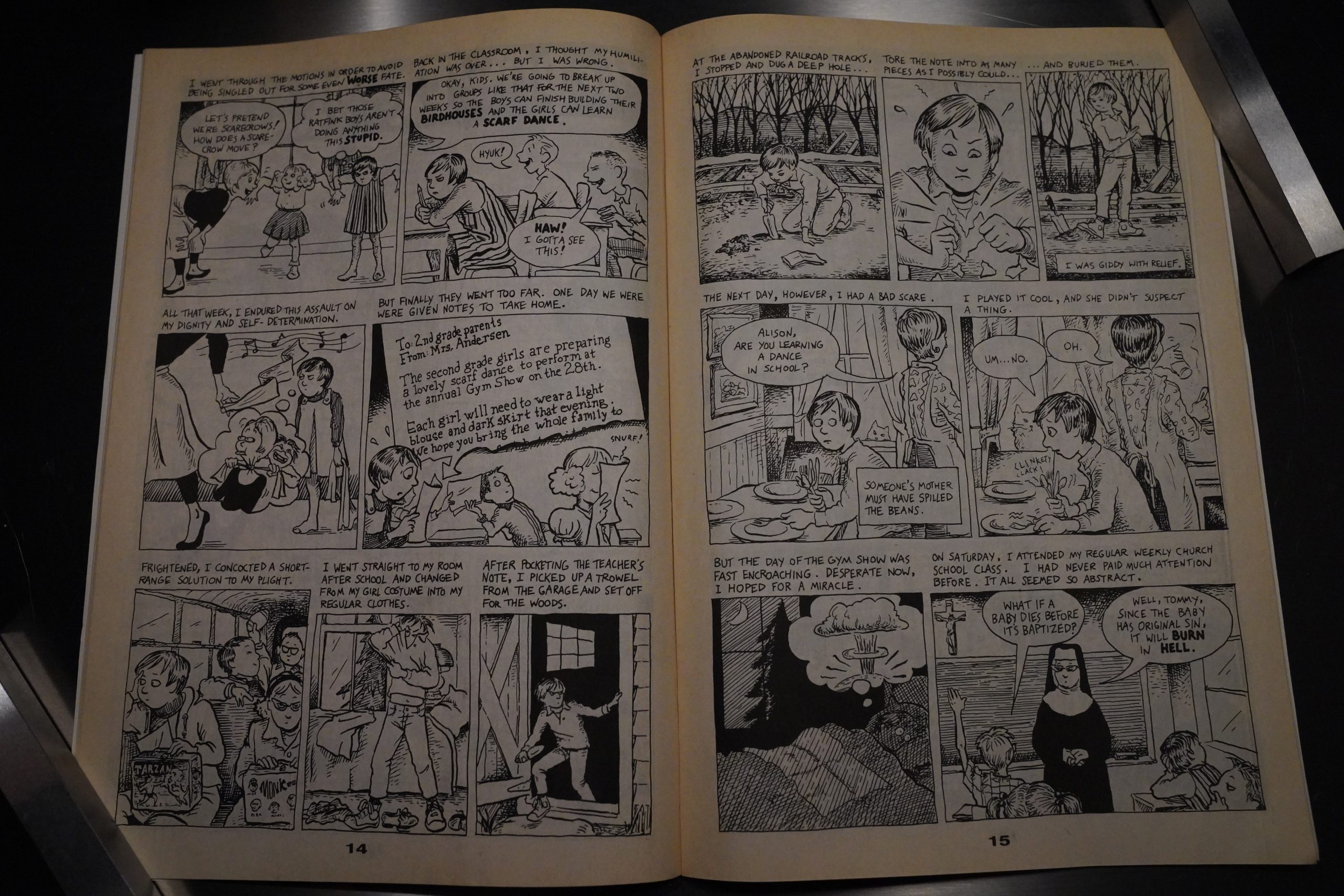

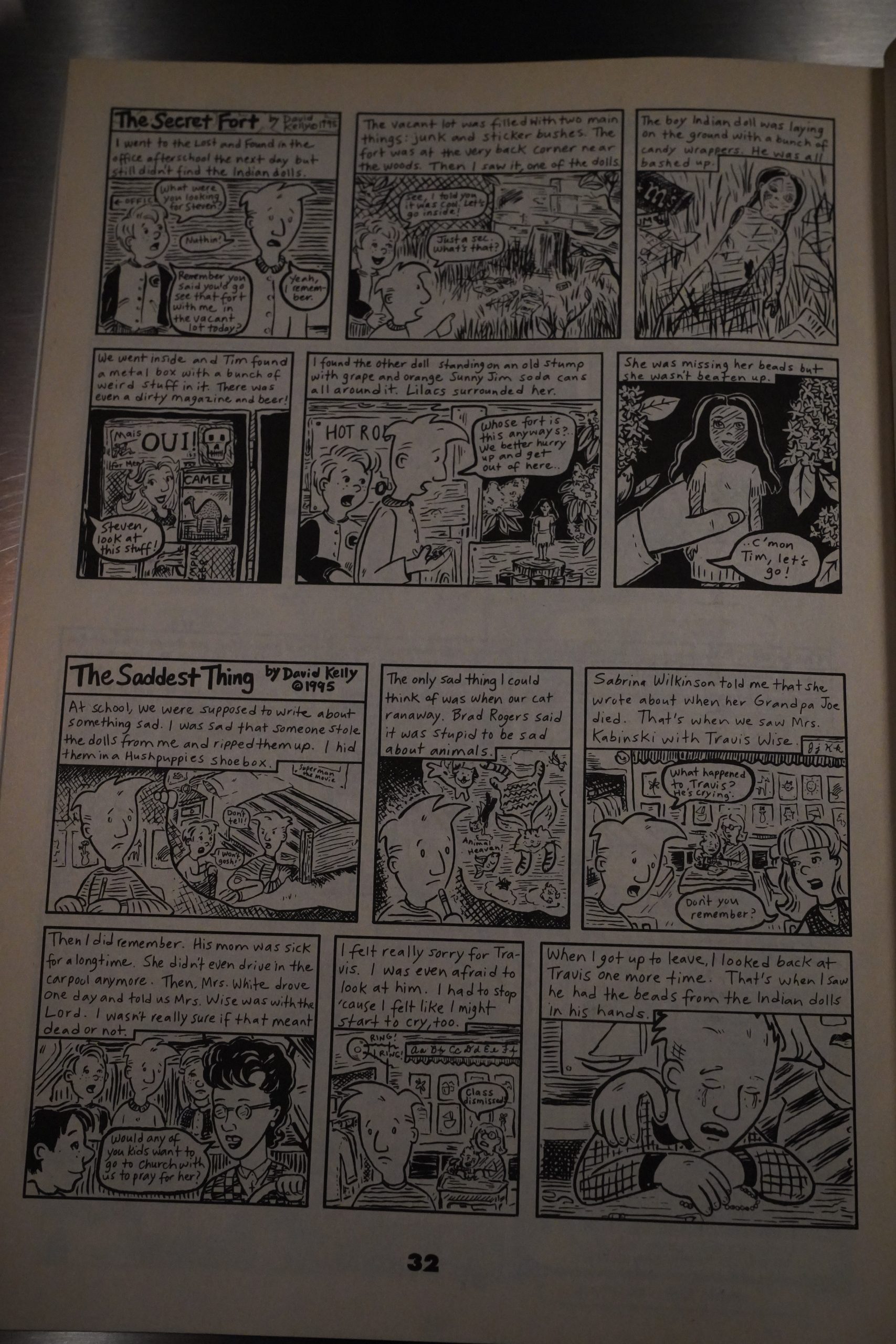

… and the second is a pretty amusing anecdote from her childhood. It’s great!

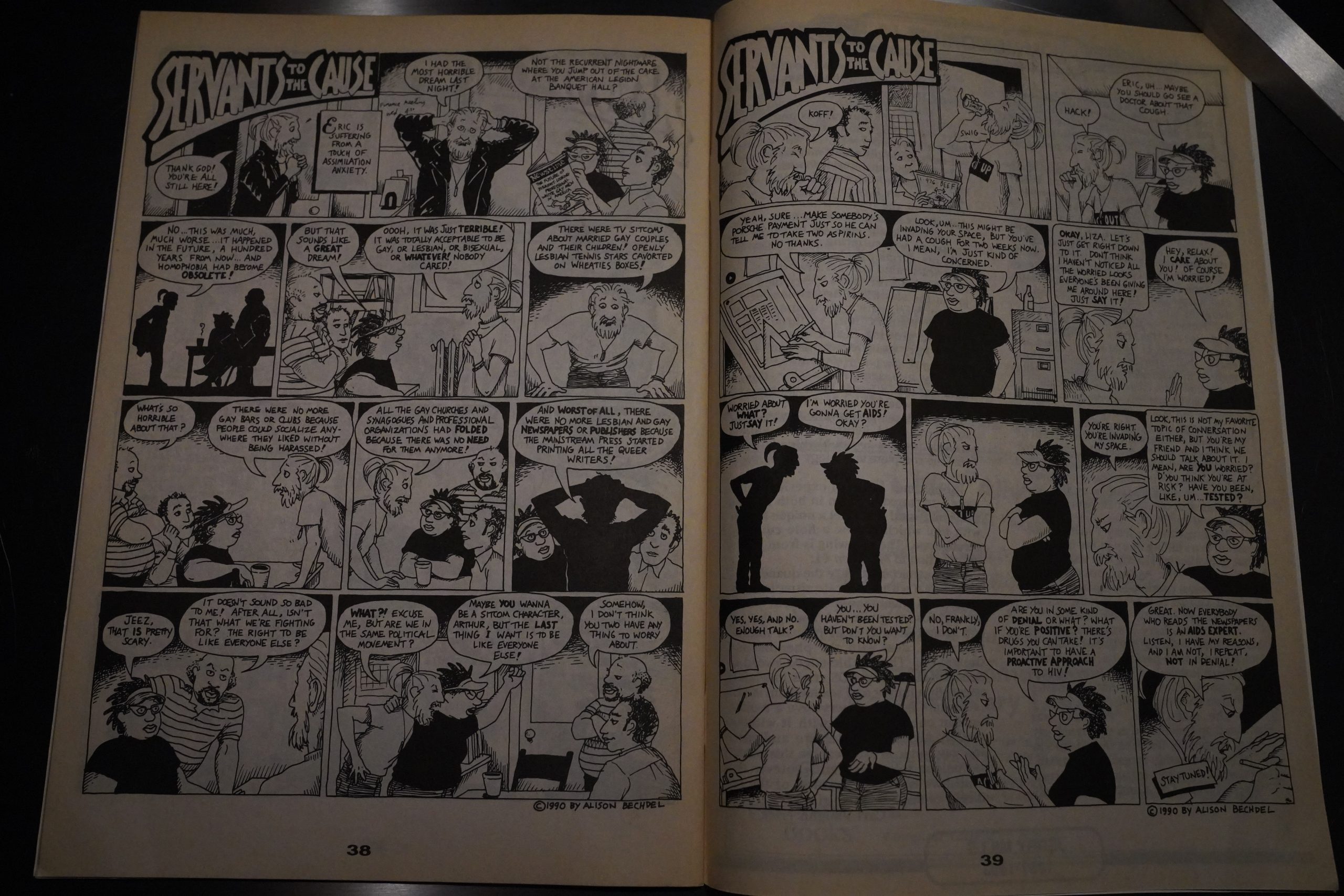

The last half of the issue reprints her Servants of the Cause strips, which ends… on an odd note. But as far as I can tell, this was how the strip (which ran in The Advocate), really ended.

Then we’re back to the regular anthology format again, and get another super-hero themed issue. It goes better than the first one. (Joan Hilty above.)

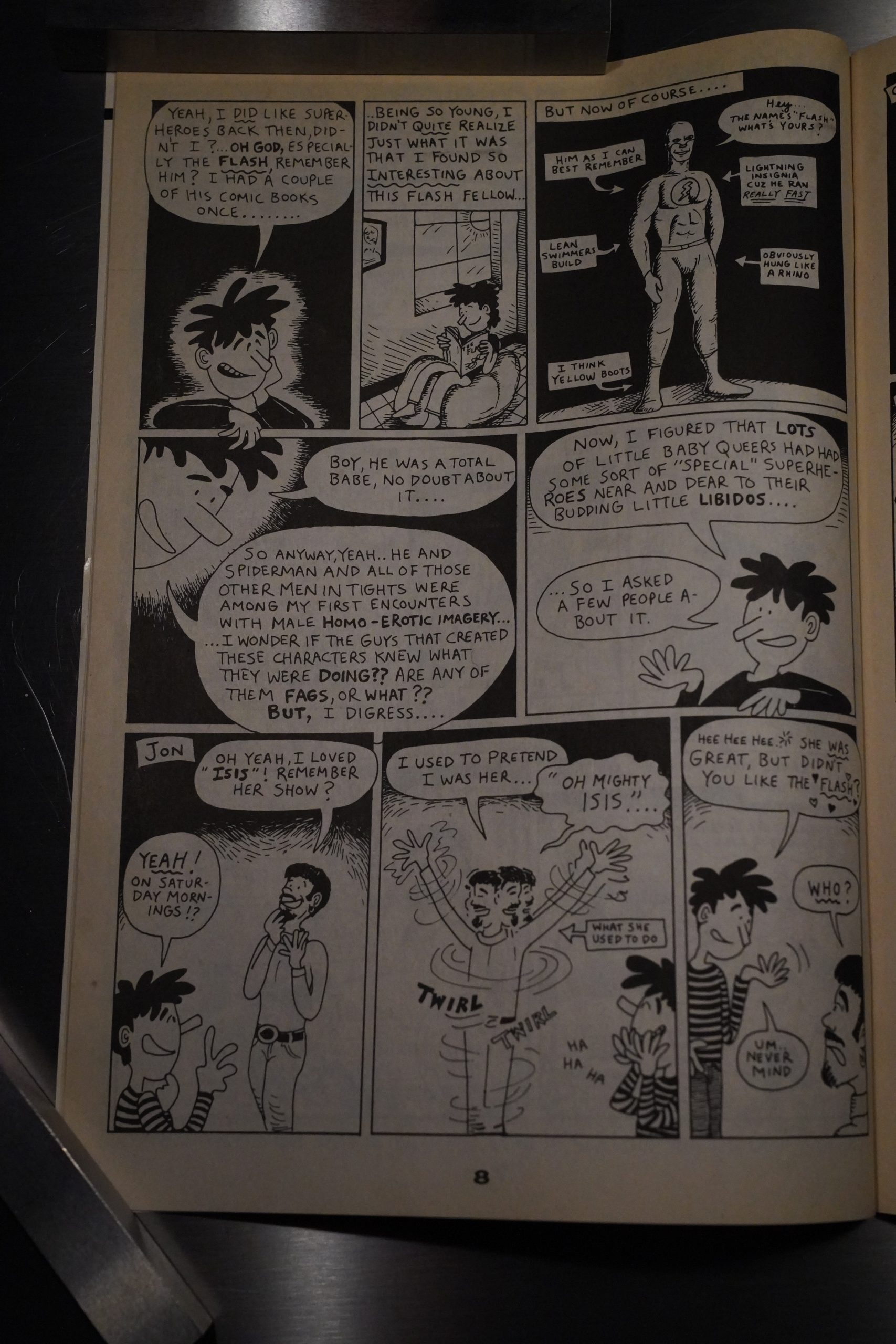

Most of the artists struggle to find something to say about super-heroes, though — I think the editor was more into the concept than the contributors. (Robert Kirby here.)

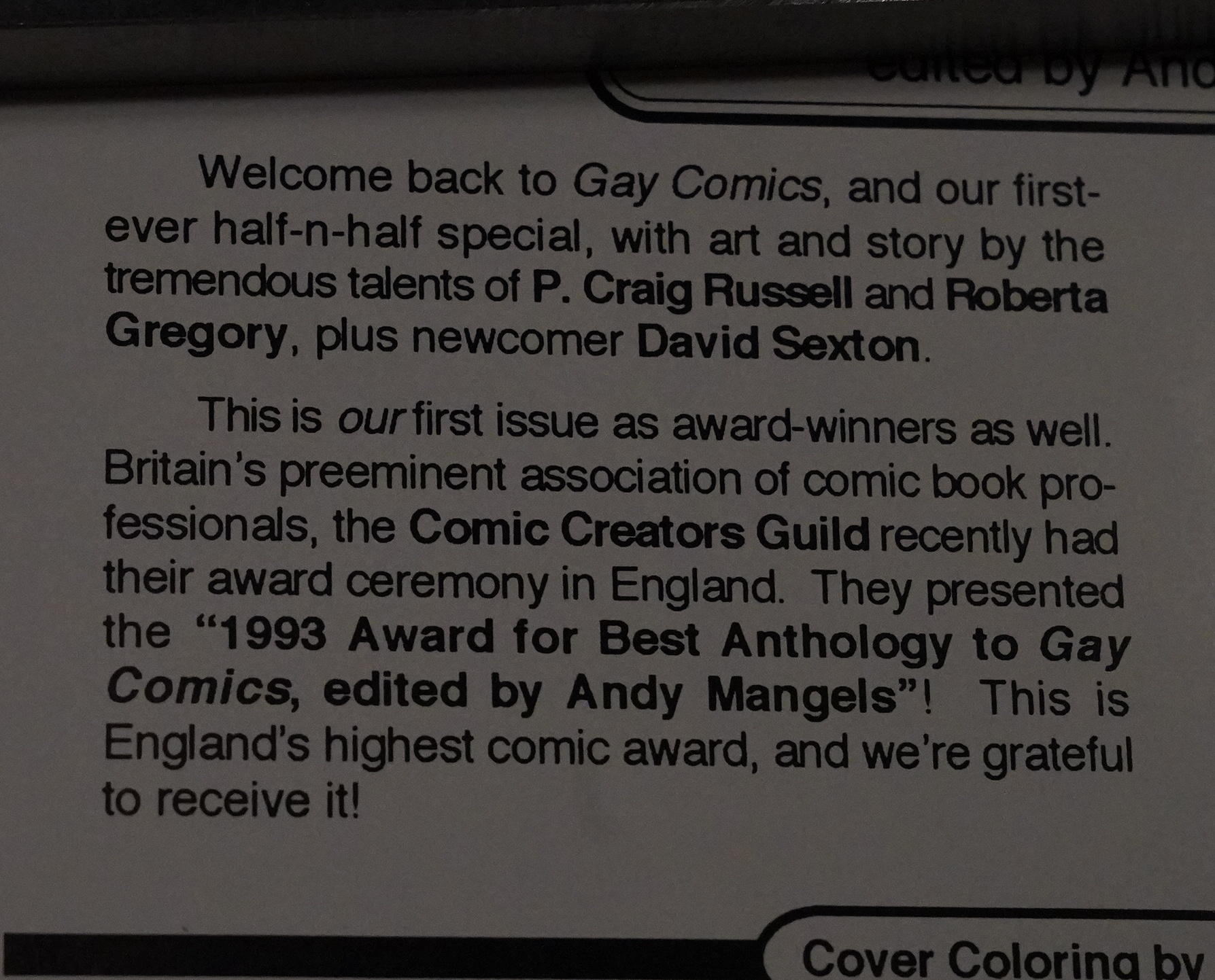

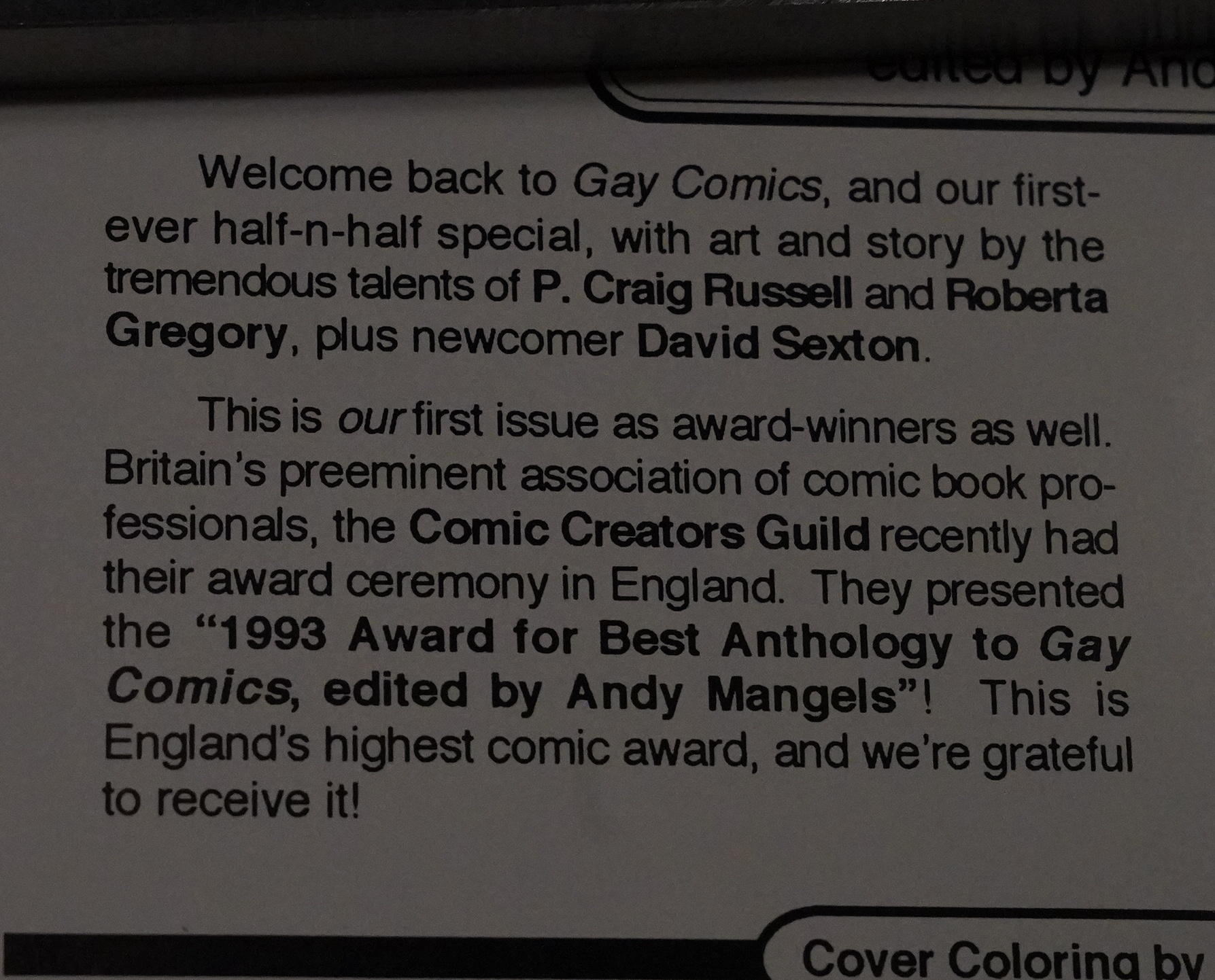

#21 is half Roberta Gregory and half P. Craig Russell (written by David Sexton). And… Gay Comics had won Best Anthology by the Comics Creators Guild in the UK? Wow.

Gregory’s half is a Butchy Butch story, and it’s fun and sweet.

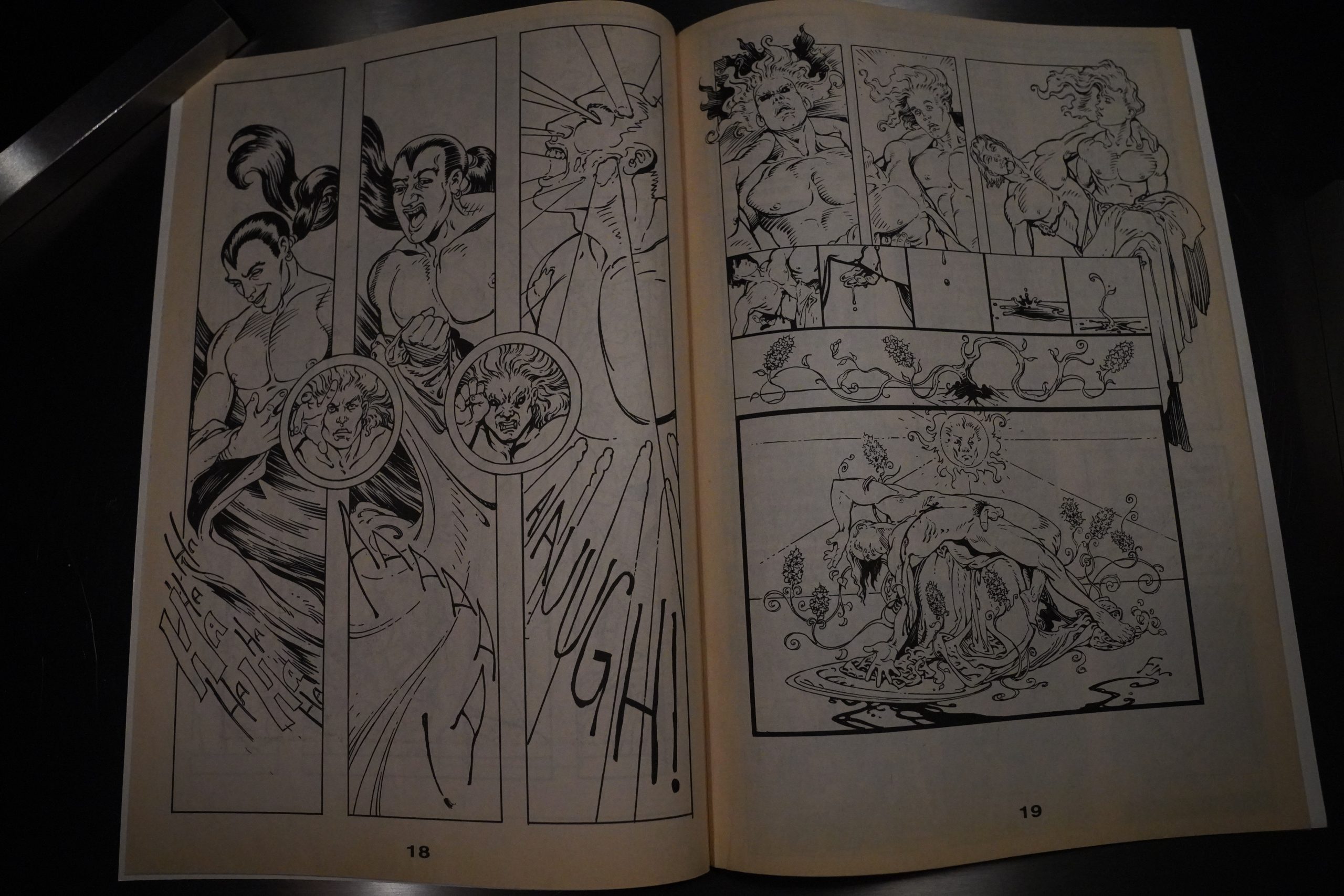

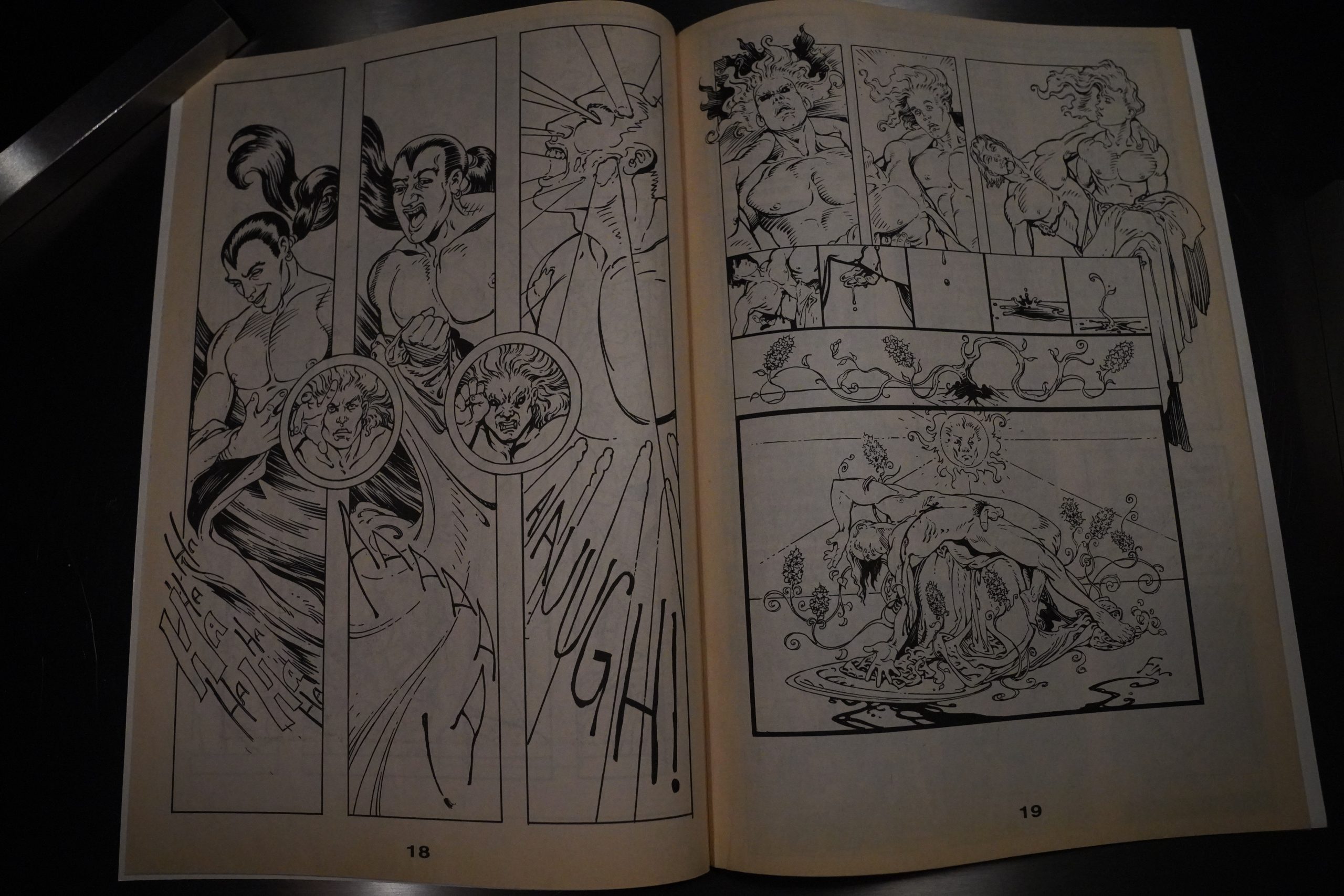

The Sexton/Russell thing is all mythological and stuff. The artwork’s very nice (I mean, it’s P. Craig Fucking Russell), but it seems perhaps not as painstaking as his artwork usually is?

Reed Waller and Kate Worley drop by with an Omaha The Cat Dancer Story, and it’s sweet, too.

Even the Diana DiMassa story is sweet! What’s going on!

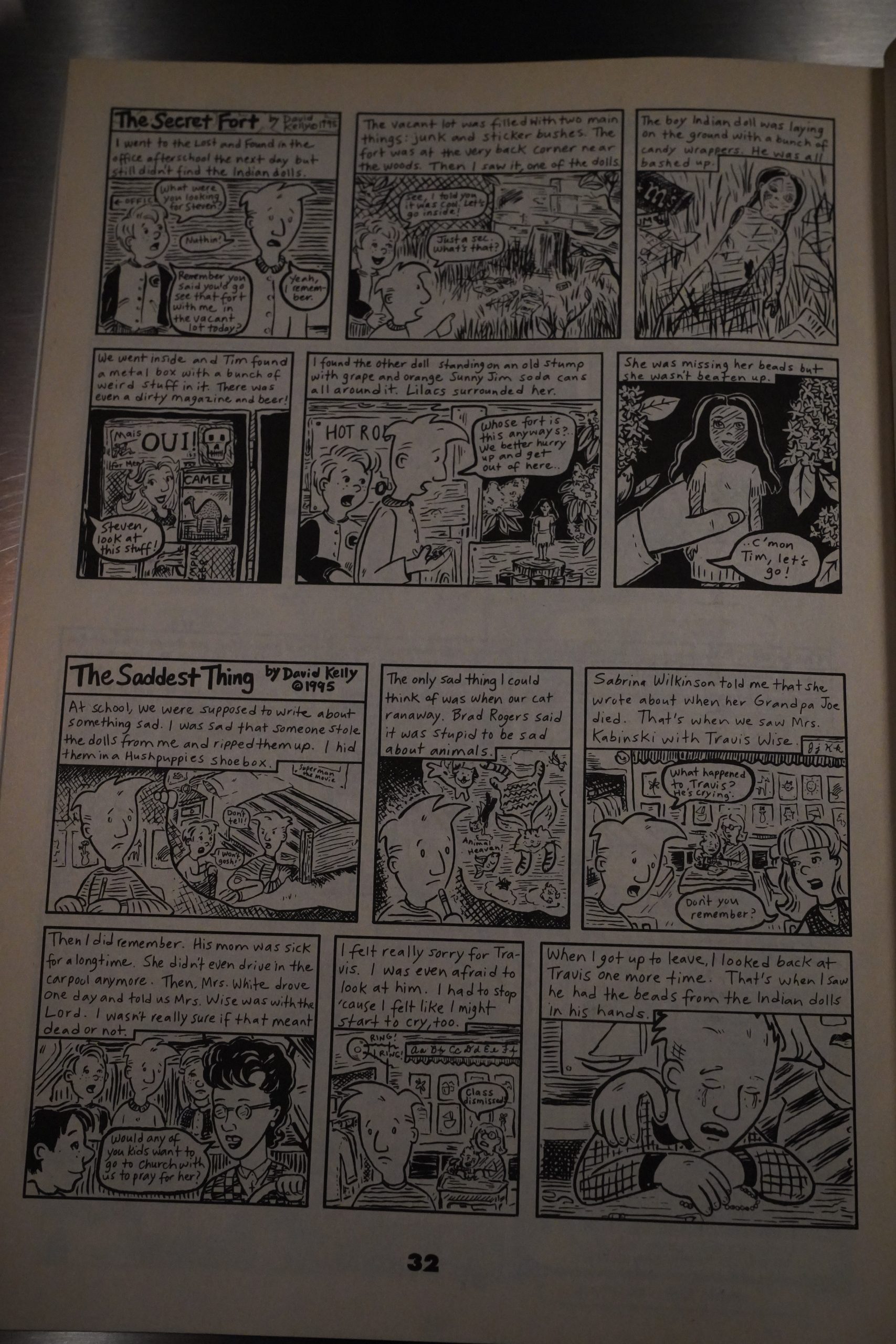

The last few issues are, on the whole, the best issues since the first few issues. There’s fewer outright clunkers, and there’s some really good ones, like this one by David Kelly.

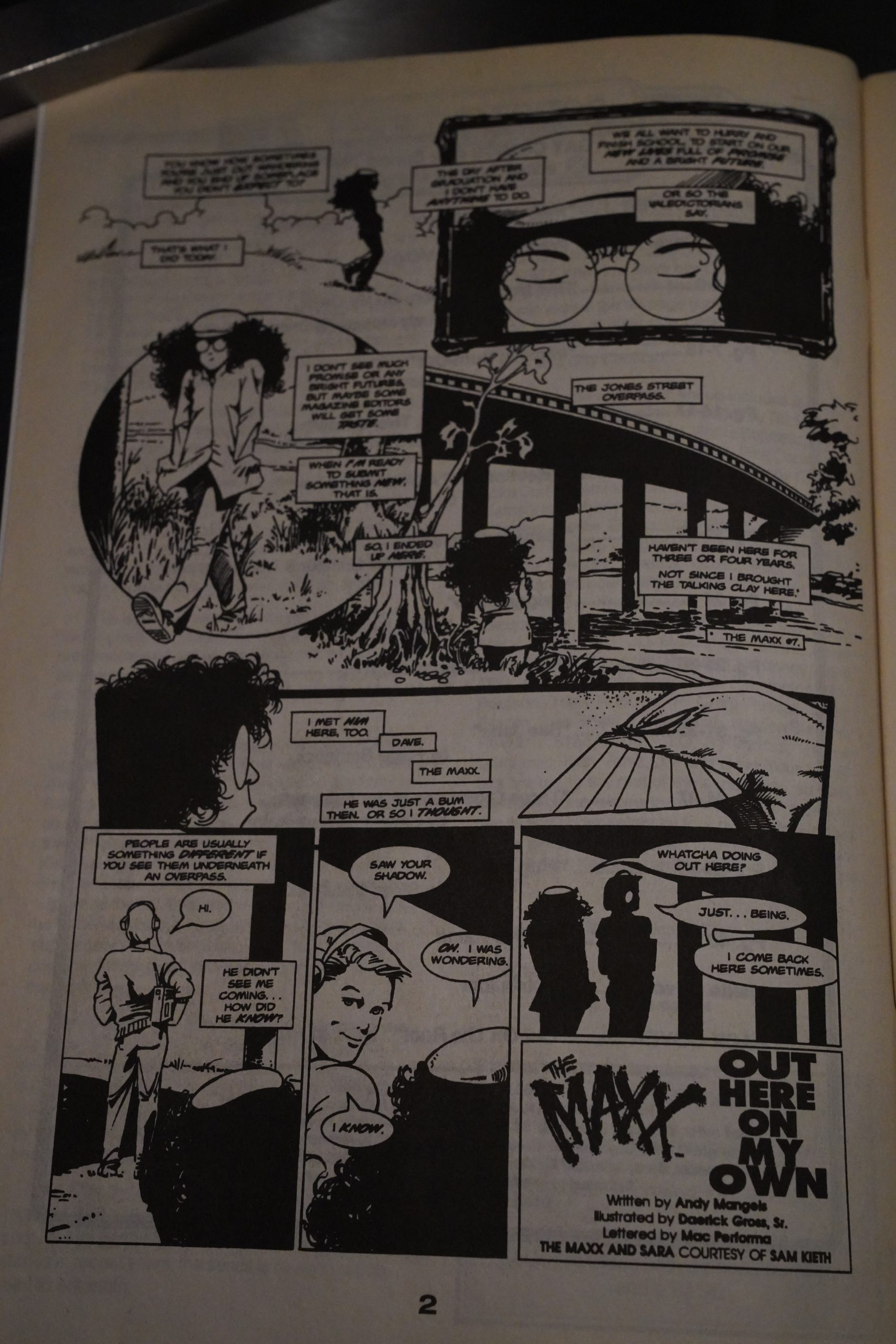

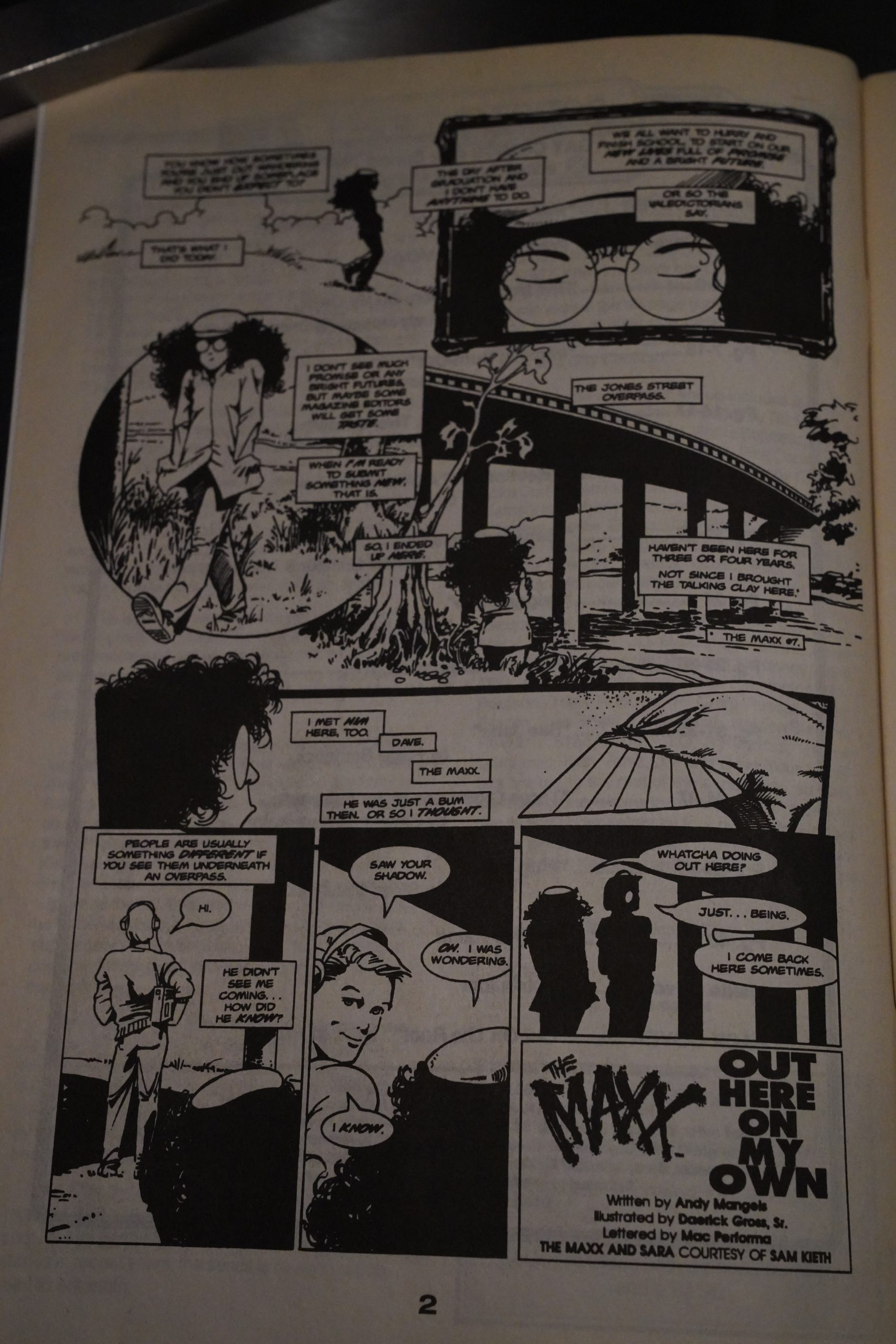

It’s not all winners, though — why on earth is the editor writing a Maxx story all of a sudden?

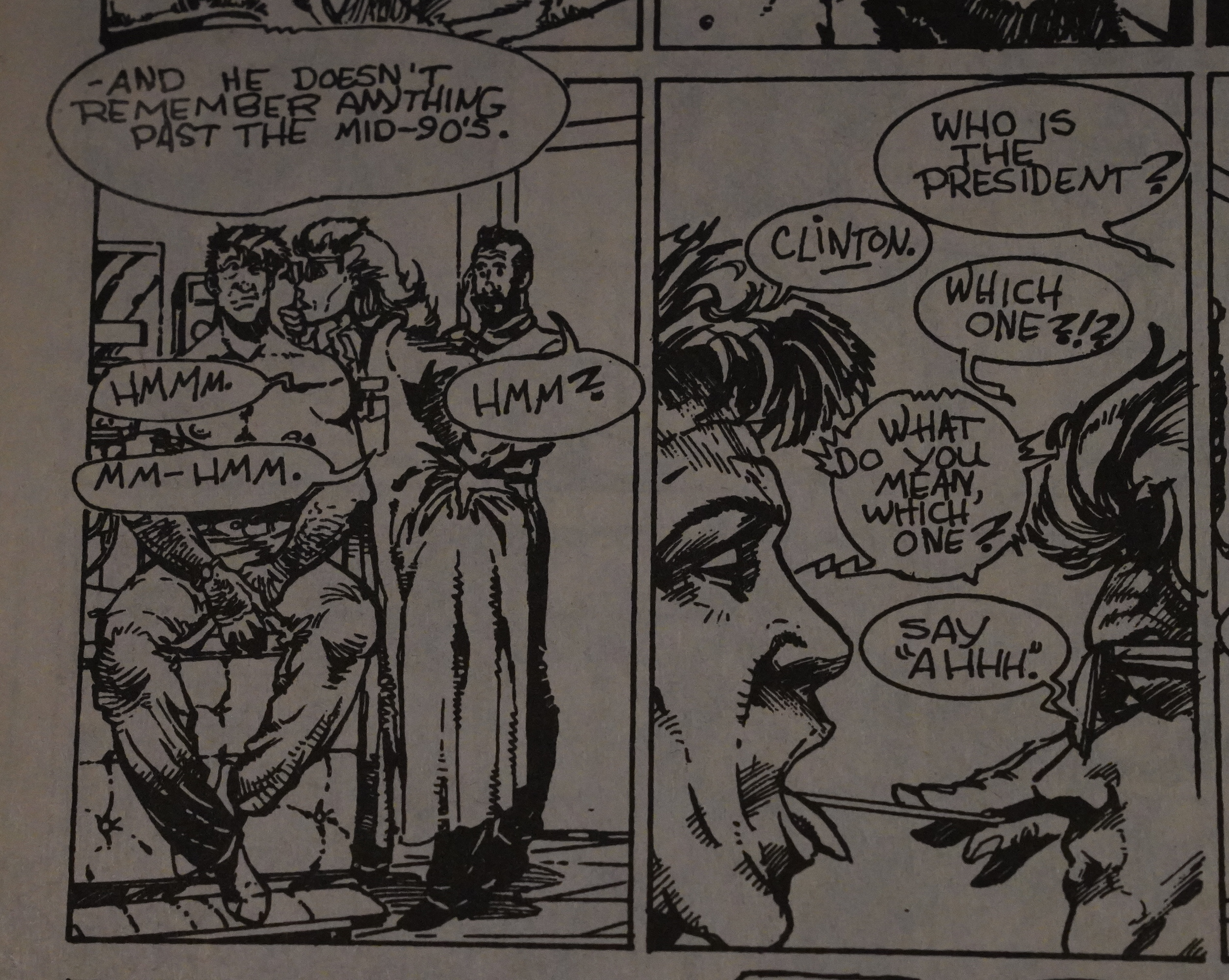

Marc Lynx and John Dennis does a sci-fi-ish serial (well, two parts, almost) that’s so close to being prescient.

*whew* That’s a lot of contributors.

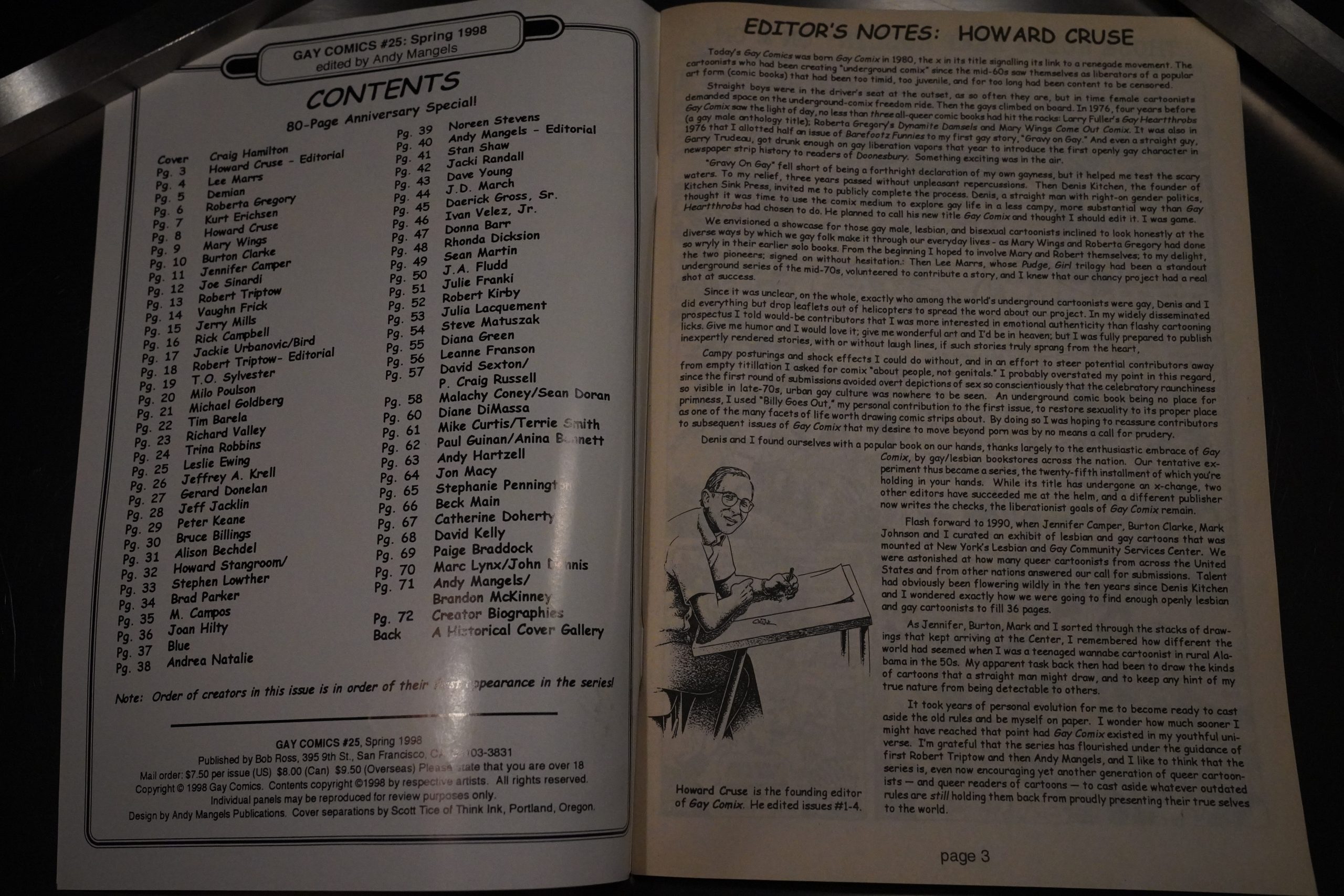

Yes, we’re finally at the final issue, after about 1000 pages of LGBT comics. #25 is 80 pages long, and features 73 different contributors (so they only get one page each).

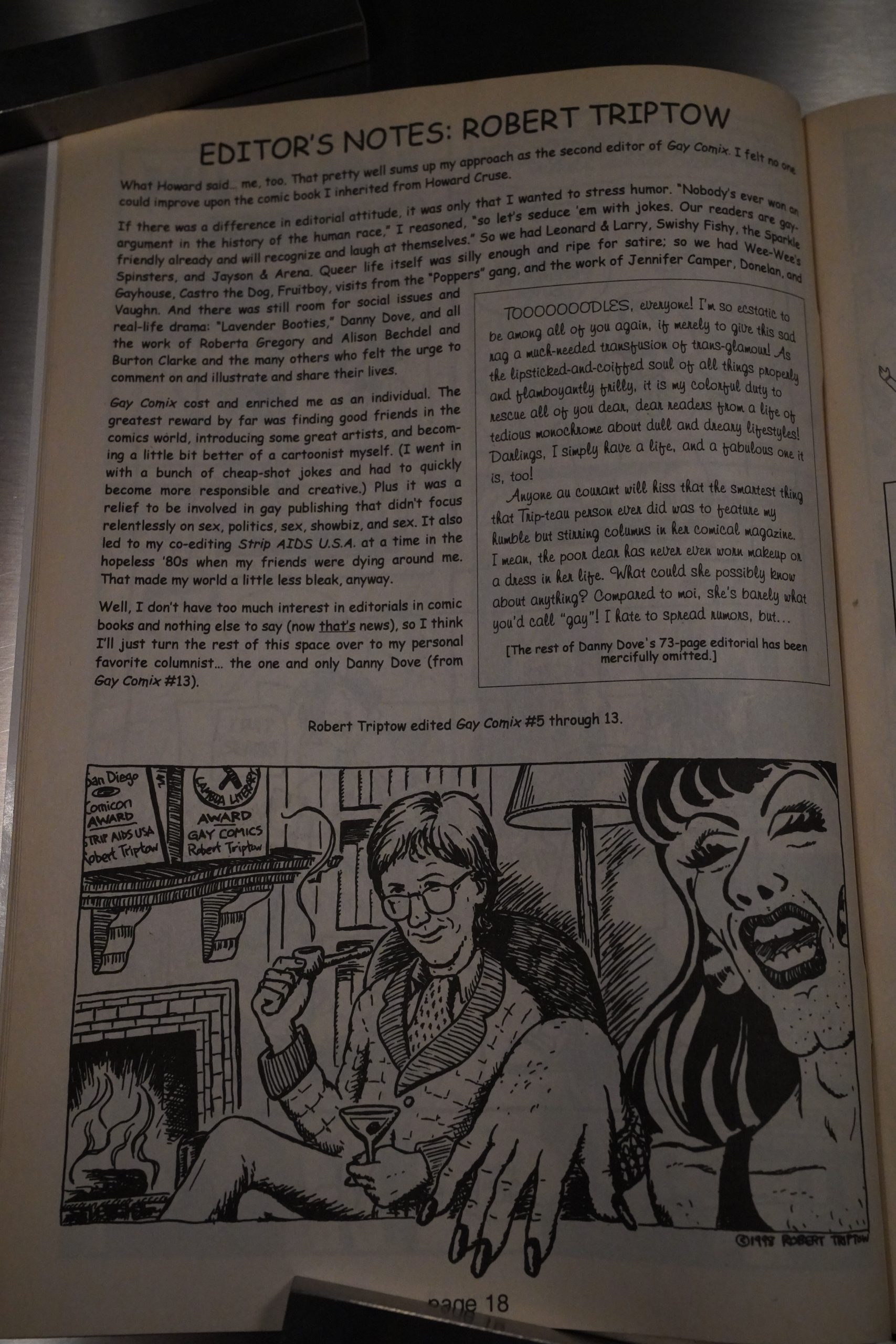

Cruse writes a bit about the backstory to how Gay Comix came to be — it was indeed instigated by Denis Kitchen, which is somewhat unusual for an anthology: They’re usually the passion project of an editor, or a group of artists, while this one was first the project from one publisher (Kitchen) and then another (Bob Ross), who then found editors for the book.

Perhaps this explains some of the… dashed-off feeling many of these issues have. If you compare with, say, Wimmen’s Comix, there’s a lot of wild and weird (and sometimes amateurish) stuff in there, too, but there’s a palpable passion to the material; that it matters. You don’t get that feeling with Gay Comix/cs. Sure, there’s individual pieces that are stunning, but there a lot (mostly?) stuff that’s just there.

In any case, Mangels’ final issue is a brilliant way to end the series: By inviting all the previous contributors (apparently), and then printing their contributions in the order they first appeared in the book, gives it an odd sort of wonky cohesion that makes it really readable. It’s fun to catch up with all these people we’ve been reading stuff from over the years, and seeing what they’re up to now.

Most of them don’t really comment on the anniversary issue, but are just doing their stuff, but… they’re bringing in good stuff.

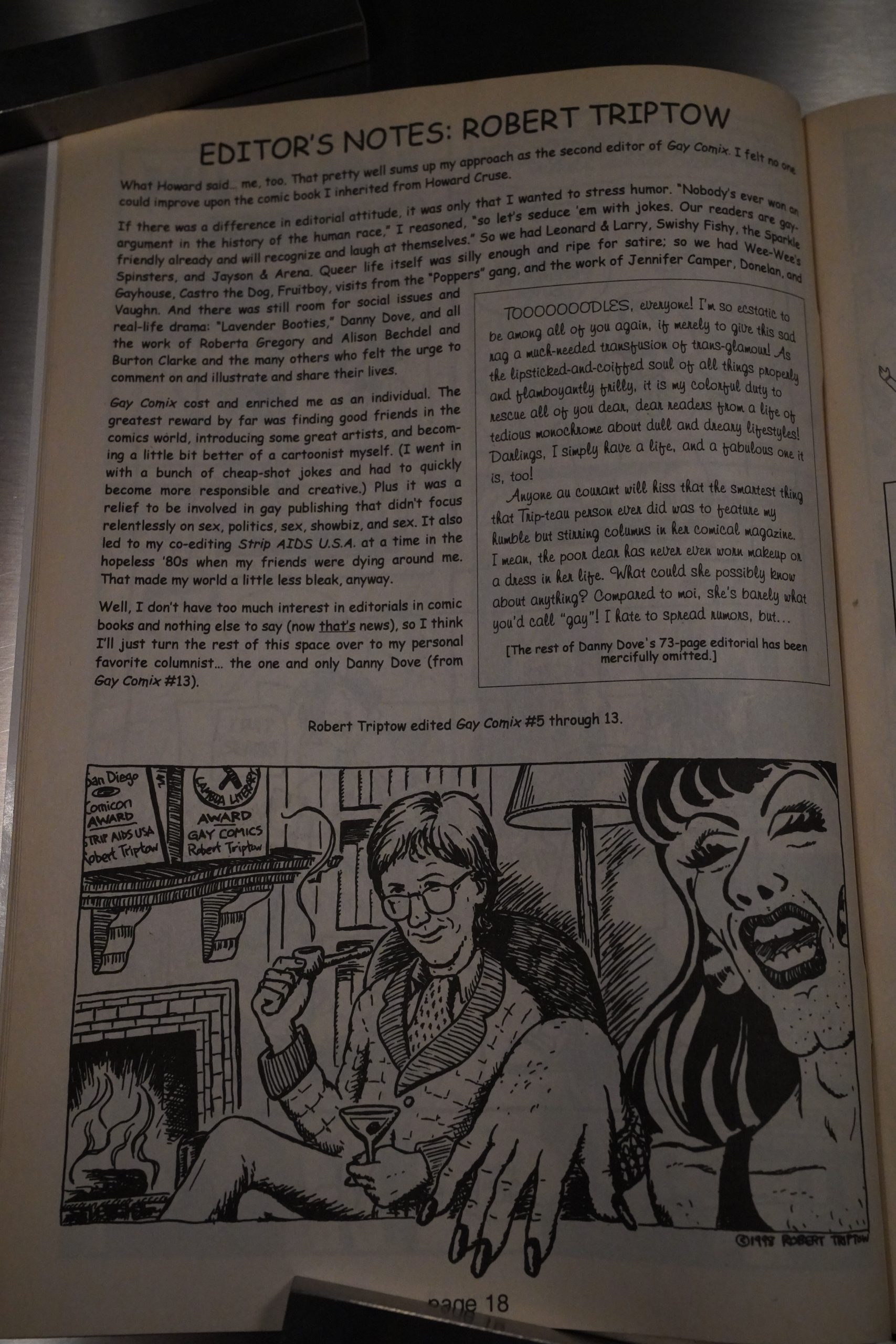

All three editors write an editorial, and Triptow confirms that he was aiming for a lighter approach with his issues.

Well! There you are! I made it to the end! It took me a few days, and I probably repeated myself a lot up there? Did I? I don’t know, because I’m not reading that stuff.

I think you could make an excellent 200 page collection from the best of these pieces.

Somebody writes in The Comics Journal #83, page 44:

Nonetheless Kitchen remains one of the

most committed and true to the original

principles Of “underground” publishing,

and Gay Comix is proof.

Fortunately for Kitchen, Gay Comix has

found its own distribution through gay

bookstores independent Of the usual

“underground” paraphernalia shops

(many Of which are being put out of busi-

ness by new legislation), and has been suc-

cessfpl enough to reach its third issue.

The job Of editing Gay Comix has to be a

real tightrope balancing act. To begin

with, there are two gay constituencies,

each with its own standards and tastes:

female gays and male gays. Although

brought together by political considera-

ti0ns, male and female gays in general

follow very different lifestyles and atti-

tudes, a situation implicit in the basic dif-

ferences between men and women and

sometimes exaggerated almost to the point

ofcaricature by the more extreme members

Of the gay community. The problem in try-

ing to publish a comic that satisfies both

gay men and gay women is exemplified by a

letter in by regular contributor Mary

Wings: had trouble with the cover [Of

#11. After discussing it with friends I could

see the humor in it, but since you said you

hoped you wouldn’t get •genitally oriented’

comix, I was surprised. Seeing a giant penis

on the cover has not much to do with our

common culture.

And that leads us directly to the second

factor to be carefully weighed and bal-

anced: just how sexually explicit can, Or

should, Gay Comix be? Many ‘ ‘under-

ground? artists have been doing sexually

explicit work for years, of course (some of it

grossly explicit), and even a few female

“underground” artists, like Trina, have

done “erotic comix for women” with vul-

vular symbols, although the vast majority

Of those who did sexually explicit comix

were men. An emphasis on genitality is a

major aspect Of certain segments Of the

male gay subculture, while it is a rarity in

the female gay subculture. Despite the ex-

pressed editorial hope that there would be

no “genitally oriented” material in Gay

Comix the erect penis is not absent.

Despite that, I searched the cover Of in

vain, looking for the “giant penis” Mary

Wings complained about. Rand Holmes’s

cover shows a California beachboy-type in

the foreground, clad only in snug-fitting

shorts thAt outline his genitals—which are

normally proportioned—and about to take

the first bite from a mustard-dripping hot-

dog. Behind him is a man in a closet. The

closet was obviously ripped out of the wall

in which it had been built, and clothes and

clotheshangers are falling Out. We can see

only the feet, right arm (sticking out

through a hole and clutching the closet as

if to hold it up), and eyes (staring through

two holes in the closet door) Of the man in

the closet; who is obviously freaking out

with pleasure at the sight of the virile

beachboy. Despite the phallic symbolism

of the hotdog and the graphic outline of

the beachboy’s genitals, there was no

“giant penis” to be found, even hidden inu

background details. I would guess that the

snug-fitting shorts were too graphic for Ms.

Wings although hardly offensive at all •to

most gay men, or possibly even to many

non-gays of eiiher gender.

[…]

But lurking none too deep beneath the

surface Of each these stories is an existen-

tial angst: a sense that nothing, least of all

love, lasts very long, and that the best one

can hope for is to grow old and ridiculous,

a sad and silly fool playing at being still a

kid. In fact, there are gay bars crowded

with testaments to that point of view, but is

this an exclusively male problem?

Not if Cheela Smith or Roberta Gregory

are to be believed. Gregory’s “Another

Coming-Out Story” resolves on a note Of

renewed hope, but only after her heroine

has touched bottom with alcoholism and

despair.

Cruse is interviewed in The Comics Journal #111, page 83:

RINGGENBERG: 1 remember that Gay

Comix cover with the gay guy in the closet

watching the handsome Yung man eating a hot

dog

CRUSE: Yeah. Rand Holmes did that

drawing.

RINGGENBERG: Is he or did he just

do that for you?

CRUSE: I’ve never met Rand Holmes. I’ve

never even corresponded with him. He

made a direct offer to Denis Kitchen to do

that cover when he heard that there was

gonna be a Gay Comics. He had done a gay

Harold Hedd story earlier [in All Canadian

Beaver Comix although Harold Hedd in

other strips behaves quite heterosexually.

We made sure that Rand understood that

contributors to Gay Comix would most like-

ly be perceived as gay or bisexual, and he

didn’t respond with any objections. so

whatever his personal story was, Denis and

I appreciated his offer and were happy to

get someone of Holmes’s quality to do the

cover of the book.

RINGGENBERG: It was a very funny

CRUSE: we felt it started the book off on

a good, solid note. It showed that this wasn’t

going to be a tacky product.

RINGGENBERG: When I was living with

my friend Leslie Stembergh, she had all the

back issues of Gay Comix. I read it and, as

a straight male, I found the material for the most

part to be insightful and well done. Gay or

straight—it didn’t matter. They were talking

about yeal life experiences.

CRUSE: That was the goal—to have gay

men and lesbians talking about real expe-

riences. Even though the stories might be

fictionalized in some ways, we wanted them

to reflect the real feelings that people have.

Gay people have been presented stereotype

ically so much that you’d never know that

we’re perfectly normal people. We’re always

presented in some bizarre way—yet most of

the gays I know fall into the same range of

personalities as nongays. It’s true that some

patterns have evolved in the gay subculture

that are different from the familiar patterns

we’re all raised with in the straight world.

For instance, as I mentioned earlier, in the

gay subculture—or the gay male subculture,

I should say—a common pattern is non-

monogamous relationships, whereas mono-

gamy is given great lip service in the straight

community.

Maggie Bloodstone writes in Amazing Heroes #202, page 78:

Gay Comix #14

New editor Mangels seems to want to

include as much diverse talent as

possible in Gay Comix, but in so

doing, this issue is not nearly as solid

and consistent as the magazine has

been in the past.

Willingness to try out new talent has

been a tradition in GC, though, and

Mangers first issue apparently is in

step with that attitude—though hope-

fully not at the expense of the

consistency Gay Comix has enjoyed

in the past 12 years. Perhaps ‘theme’

issues, such as the “Super-hero” issue

#8 (no, Batman & Robin are nowhere

in sight) might give the book more

cohesion in the future. (Gregory’s

cover for #14 would have been ideal

for a “mythology” issue.)

Mangels contributes his short story

“Peace of Mind,” which traces the

nervous moments of a man awaiting

news of his HIV test. Mangels avoids

turning this into maudlin mush by

providing a backbeat of other human

tragedies on the periphery of his

protagonists’ life. Stan (Billy Nguyen)

Shaw provides the mood for this

effective mini-drama on a major

subject. (There have been suprisingly

few stories on AIDS during Gay

Comix’ run—perhaps this is intention-

al, as if to make the point that there

is more to gay life than a disease.)

“The Wonder (if I am) Years” by

Noreen Stevens is yet another “com-

ing-out” story (a genre in itself in

GC), but one that cuts across gender

lines with its gentle humor and

nonchalant attitude tmvards young gay

love/lust.

Bill Sherman writes in The Comics Journal #62, page 93:

Not au Of Gay Comix’s contributors

avoid these pitfalls. Mary Wings’s

Visit from Mom for instance ,

devotes three pages to the simple

obsenration that Even Your Parents

Can Have a Gay Experience and uses

such ordinary details that even this

elementary observation is blunted.

Wings, who has been drawing cornix

about the lesbian experience since

’77, has been steadily making strides

with her rendering—her premiere

Come Out was as muddy as amateur

art can get—but her own piece in

this volume lacks the specifity of

her early , more openly autobio—

graphical work. As for pitfall two,

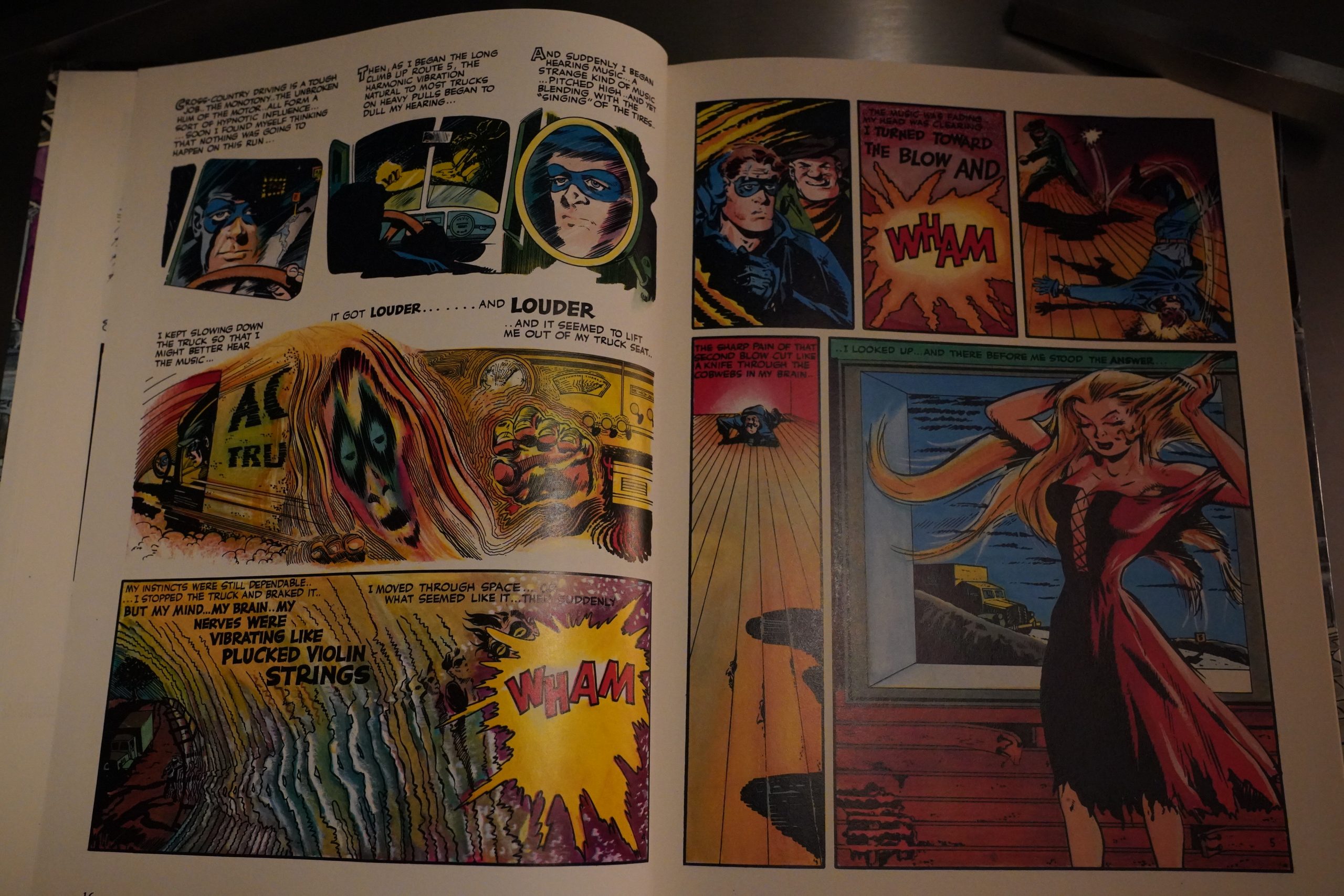

comix newcomer Kurt Erichsen’s

“Saboteur” (“Being gay but presumed

straight can be like being a spy… ‘t)

takes the subject Of maie homophobia

and treats it Like a stock spy fantasy.

The results are mildly amusing but

hardly satisfying (the tale’s red

neck conclusion is especially

, the furthest removed from

Gay’s cover promise.

The book’s two most satisfactory

pieces, however, more than live up

to editor Howard Cruse’s stated

intentions to “affirm that we [gay

cartoonists] are here, and that we

live lives as strewn with India—ink

pratfalls, flawed heroics, quizzical

word balloons and surreptitious

truths as the rest of the human

Lee Marrs’s “Stick in the

race .

Mud” is an eight-page biography

of one woman’s attempts at finding

“true love a subject Marrs has

already shown herself capable of

carrying off with humor and zest .

Marrs’s Sue is one of those eharac—

ters who are too aware of the way

their actions can lead to failure:

she’s a floater , primarily because

it’s easier to float from crisis to

crisis rather than actively precipi-

tate each crisis herself. Stuck in an

incompatible relationship with a

promiscuous blond, for example ,

Marrs’s heroine describes her actions

until the end: did the only thing

a mature, balanced individual

should

hung around doing

nothing until Angel dropped me for

a corporate attorney with a condo in

Mazatlan Even when she’s met a

woman with whom she shares a

genuine affinity Amazing! A person

more wishy-washy than I was! ,

she takes three pages opening up to

her. Marrs’s character is a comic

type—a slightly more adult, sexually

varied Pudge, in fact—but she’s no

stereotype. She’s neither A

confident threat to Hearth and Home

nor a neurotic self—hater , and

editor Cruse’s decision to lead the

first issue off with Sue’s story is

as much a statement about Gay’s

humanizing intents as it is a

commercially sensible decision

(Marrs being one Of the issue’s more

familiar undergrounders) .

But it’s Cruse’s own contribution,

“Billy Goes Out,” that presents the

fullest realization of Gay’s stated

goals. That in itself isn’t so unex-

peeted: underground fans look to a

theme book editor’s work first

because frequently the title itself

has grown out of the editor’s desire

to find a proper place for an idea

that’s excited him (another example

oi this principle at work can be

recently Seen with Jay Kinney’s

situationalist cartoon satires in

Anarchy Comics). What’s most

exciting about Cruse’s contribution

are the levels toward which the

artist is working, both artistically

and thematically. Ever since Bare—

footz when Cruse’s artist

character Headrack first started

getting involved in a series of gay-

oriented confrontations, Cruse has

been working toward a kind of

character comedy far beyond the

simple gag pieces he started out

producing, and still produces for

magazines like Fangoria. With

“Billy Goes Out, Cruse goes even

further , producing a full-fleshed

and convincing character study of

endurance and loneliness

Cruse’s hero, having recently

lost his lover , is obsessed with

images of death and loss and

attempts to take temporary refuge

from these images by cruising the

New York bars. It doesn’t work, Of

course. and the entire strip counter—

points Billy’s thoughts with his

actions, often using Billy’s person—

ally-created metaphors to comment

upon and frequently mock his

behavior. Cruse’s hero indulges in

arguments with an anthropomorphized

‘penis (“Now tell the truth. Who’s

the boss in your life—you or your

penis?” “We try to operate by con-

sensus… We respect the validity Of

each other’s needs! t’), gets

chastized by a dead childhood pet

and a recently deceased uncle ,

ironically comments on his own

detached behavior in the bars, and

keeps returning to the memory of

his dead lover Brad. In the process

he deliberately snubs the one chance

encounter that Cruse makes clear

has potential for growing past more

than transient sex.

“Billy Goes Out” is both the most

graphic and subtle piece in the

issue. Cruse doesn’t stint on show-

ing the details of bar life (including

the aiienated consumerized sex of

the backroom bars) , but he doesn’t

condemn or elevate either. Billy’s

night out of depersonalized sex is

just one way Of dealing with personal

crisis and loneliness: during one

flashback we even see him telling

his lover Brad he’s glad to have

left the bar scene behind him. More

than likely, Billy will be “leaving

the bar scene behind him” again

sometime in the future, but until

then it beats staying home and

watching television. It’s a common

enough situation for both gay and

straight readers; the details may be

different but the desperation remains

the Same (cf. Richard price’s Ladies’

Man for a novelistic depiction of one

dominantly straight man’s life in the

city single bars) .

Ray Mescallado writes in The Comics Journal #151, page 34:

Even with the comic’s limited appeal, “Leo-

nard & Larry” is a potent tool in the struggle

for Queer Normalcy: not only is it done with

skill and intelligence, it’s also pure fun to read,

enjoyable and captivating in its depiction of your

average “gays next door.” Gay Comix Special

#1 could well be the feel-good comic of the year.

That’s not an entirely bad thing, you know. •

Andy Mangels (!!!) writes in Amazing Heroes #156, page 79:

Gay Comix #12

One of the few regularly produced

still going, Gay

“undergrounds”

Comix is published on a quarterly

schedule, more or less. For my

money, that’s not often enough. This

eclectic mixture of stories features

some semitwell-known names in the

comic world and a few more who

should be well known.

Brad Parker (from Robo-Warriors)

contributes a hilarious front cover to

the issue, detailing a “typical”

reaction of a feminine gay man to a

butch dyke. Inside, Bruce Billings

contributes eight single-panel

“Castro” cartoons, each of them the

adventure of a successful gay

cartoonist and his talking dog.

“Castro” is usually mildly amusing,

but sometimes a little t(X) anticlimactic

for my tastes.

[…]

J.A. Krell contributes a “Jayson”

story, another chapter in the contin-

uing life of a gay man and a lesbian

who live together. In this episode they

must pretend to. be engaged to each

other to prevent her Jewish parents

from suspecting their lifestyles. This

series has a generally bitchy feel to it,

and would probably make a good TV

sitcom. Next, Roberta Gregory

(Winging It) contributes the first

.cbapter of a lesbian science-fiction

story set in the far future.

A two-page match-the-dildo-with-

the-professional-lady feature is next,

by; Camper, followed by Leslie

Ewing’s “Romance in the Age of

AIDS,” in which a lesbian couple

discovers how to make safe sex fun.

In the midst of the hilarious ideas here

are several fun ideas which are also

useful for heterosexuals. Editor Robert

Triptow’s “Castoids” strikes out this

time, although he usually pulls

through, and Kurt Erichsen’s “Sparkle

Spinsters” is only mildly amusing and

majorly bitchy, as usual.

Amazing Heroes #144, page 61:

One concrete example of homo-

phobia came when cat yronwode sent

in a “Fit to Print” column to Comics

Buyers Guide, shortly after Alan Light,

had sold it to Krause Enterprises and

Don and Maggie Thompson had taken

over as editors. “I had reviewed Gay

Comix every time an issue came out,

and wrote a review when issue #3

came out. I was told that the review

would be completely excised because

Chester Krause believed homosexual-

ity was ‘an abomination in the sight

of the Lord.’ Don and Maggie were

not the ones who did this. They were

very shocked as well. I kncw now that

they have changed that policy, and they

can mention gays. At that time though,

comics by gays with a gay topic were

not to be reviewed. I want to make it

clear that it was not Don and Maggie’s

fault, and I’m not angry at Krause,

even though it was an insane policy.

They’ve reversed themselves, and in

the spirit of forgiveness and coopera-

tion, let bygones be bygones.”

This is the fifty-seventh post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.