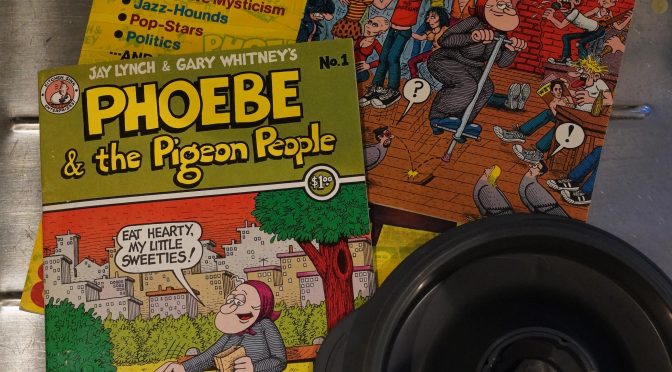

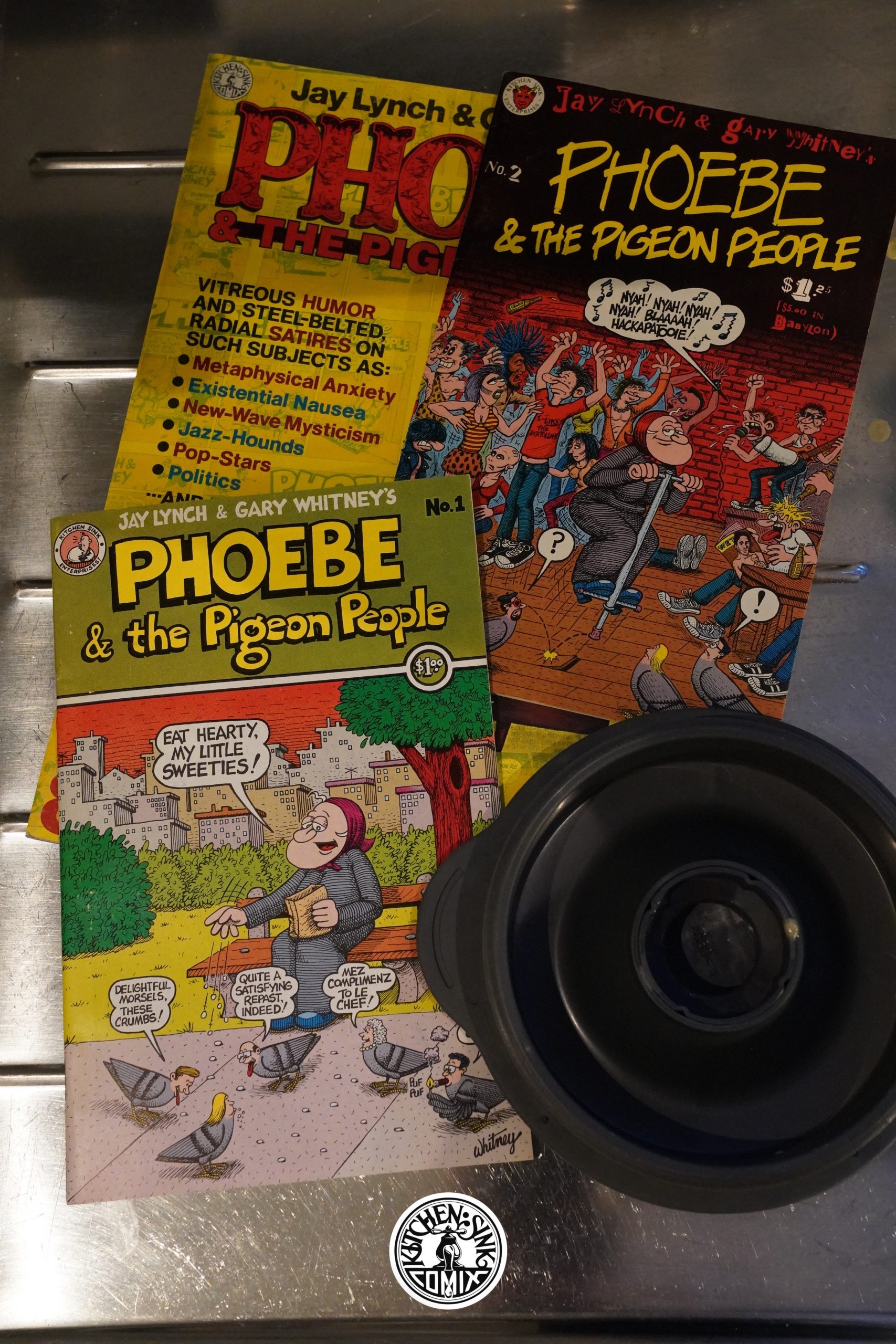

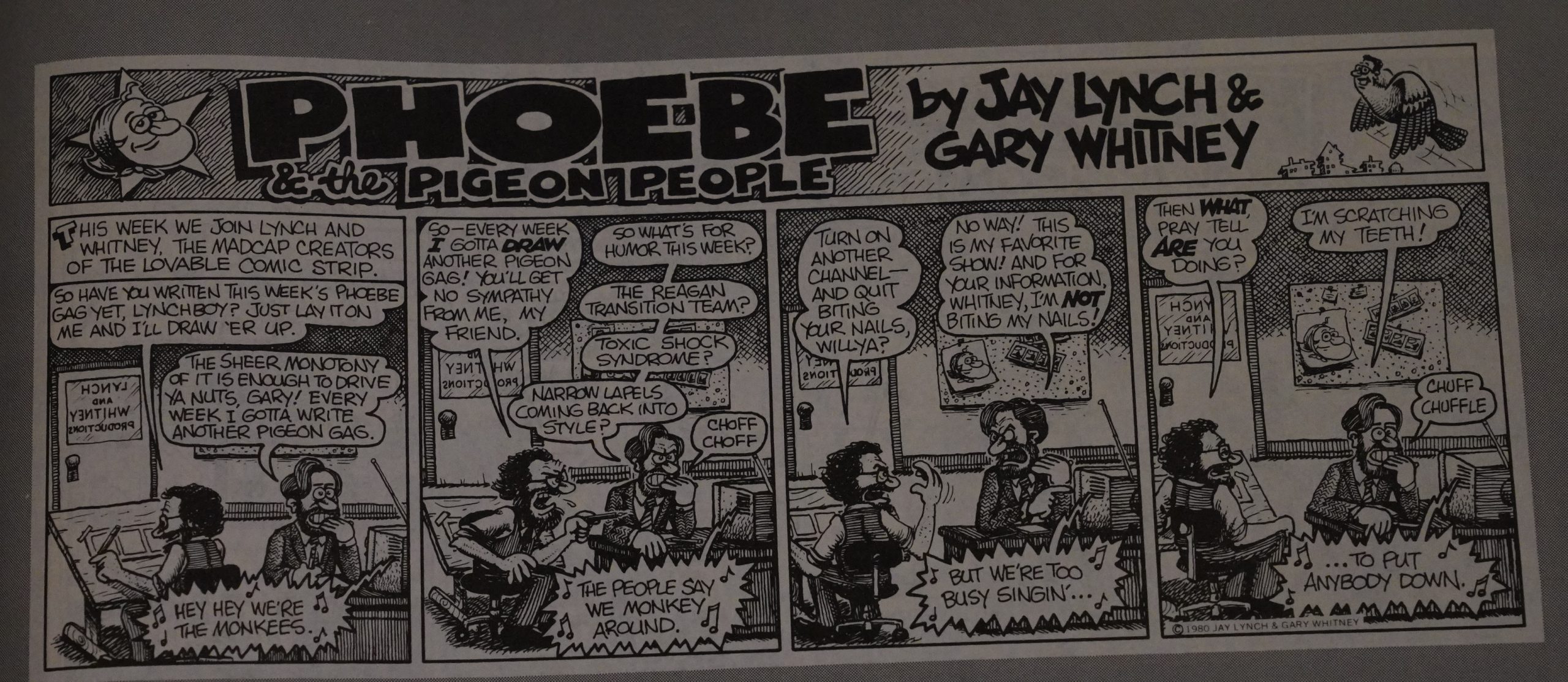

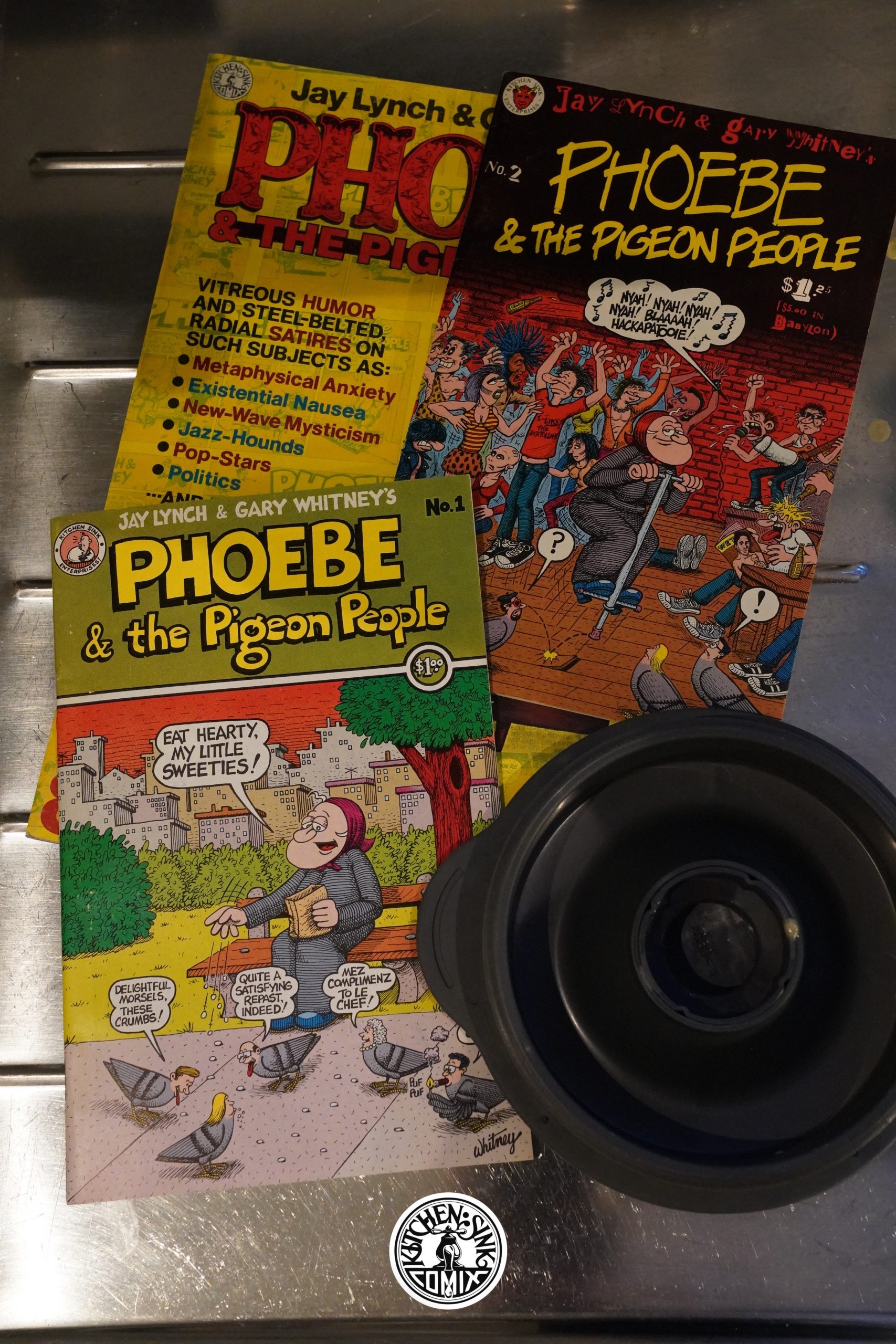

Phoebe & the Pigeon People (1979) #1-3 by Jay Lynch and Gary Whitney

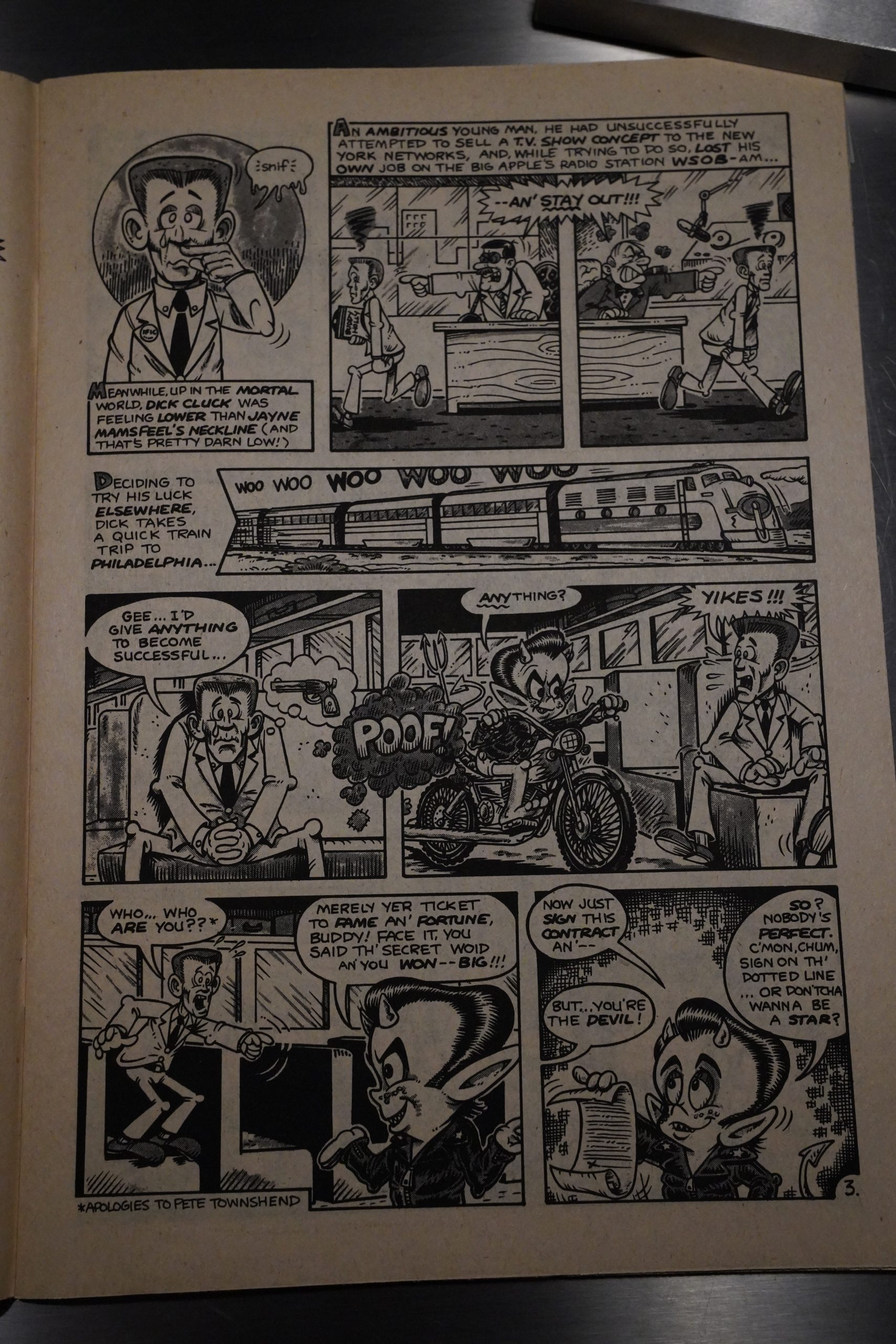

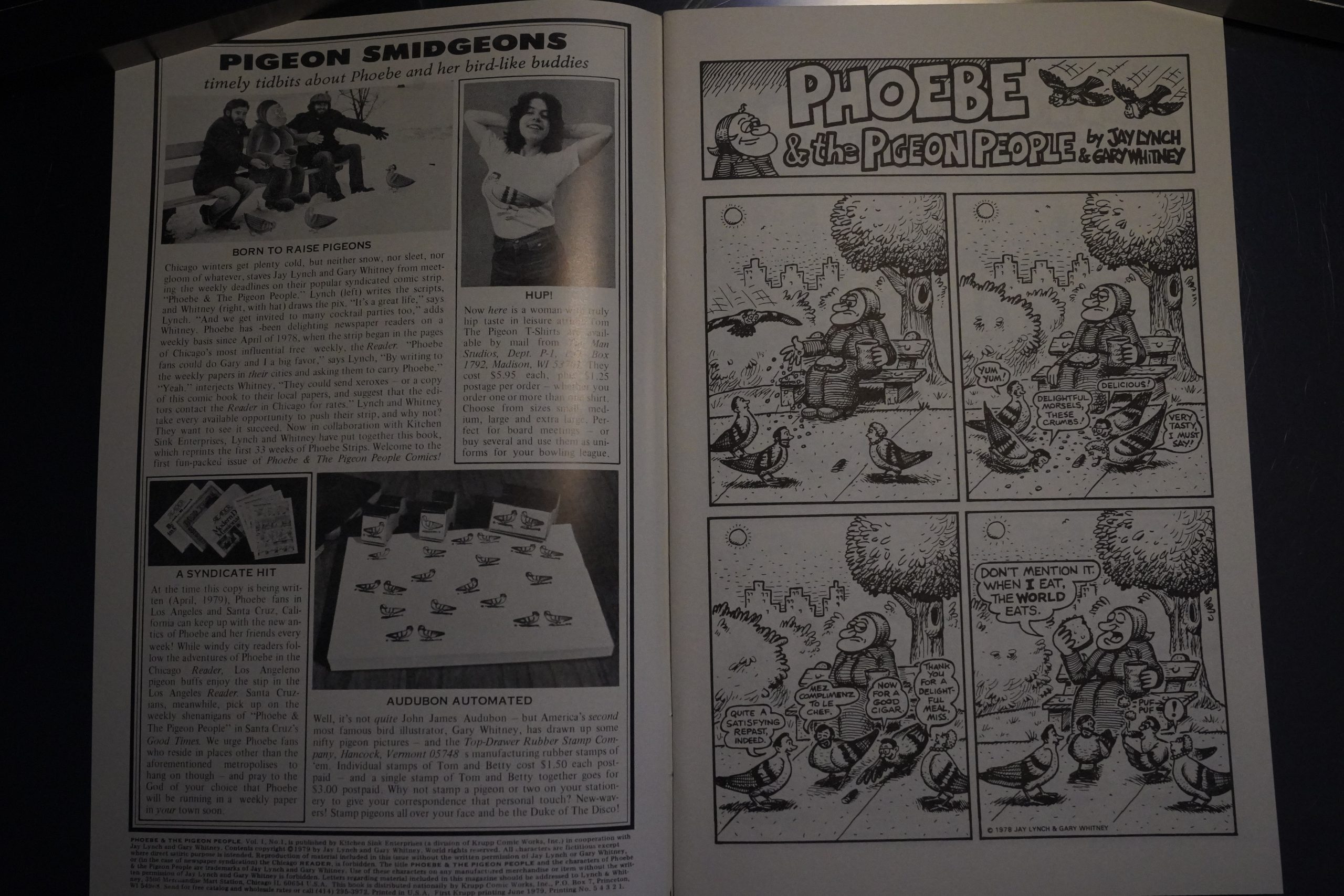

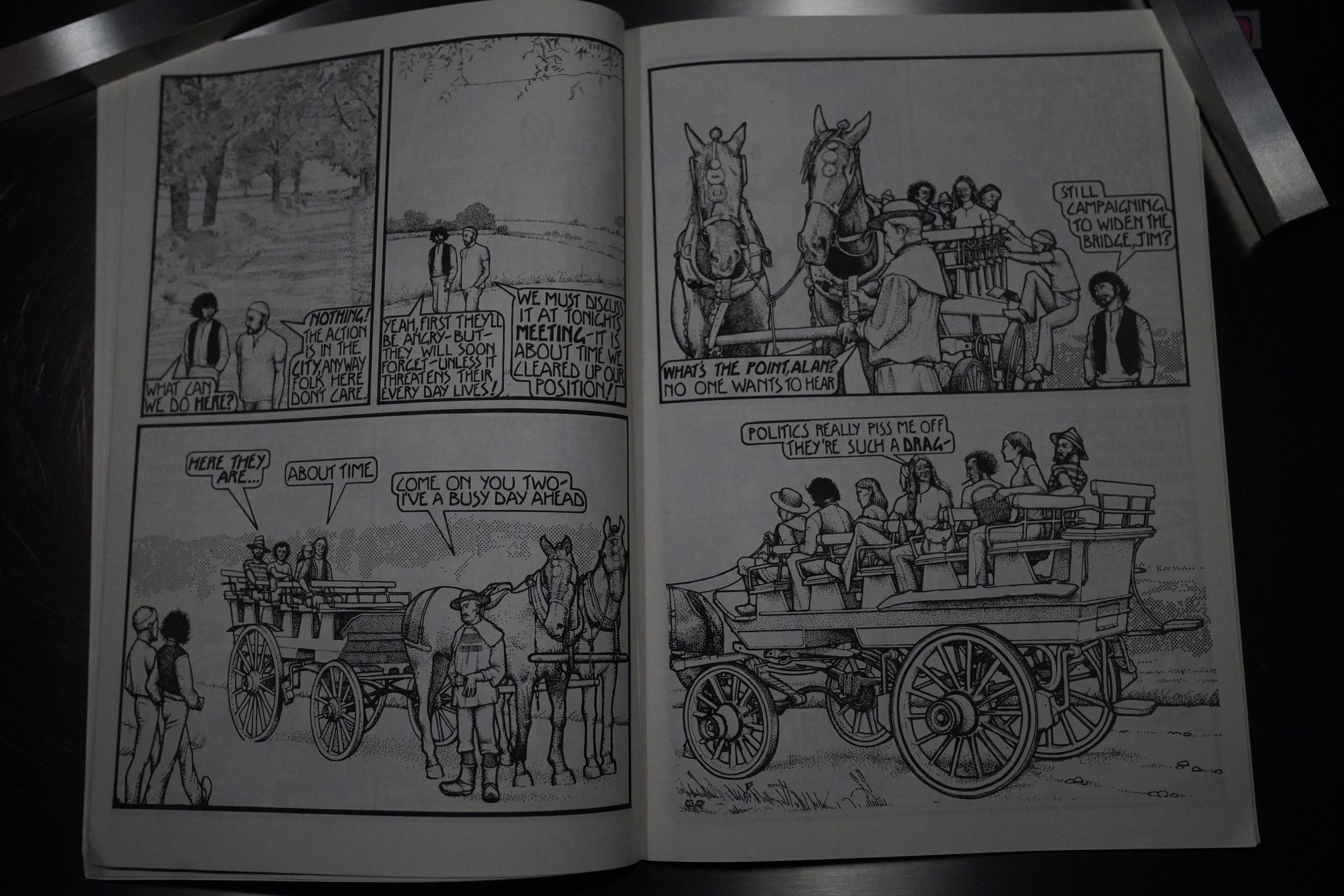

This is a collection of strips that were running in a handful of weekly newspapers across the US.

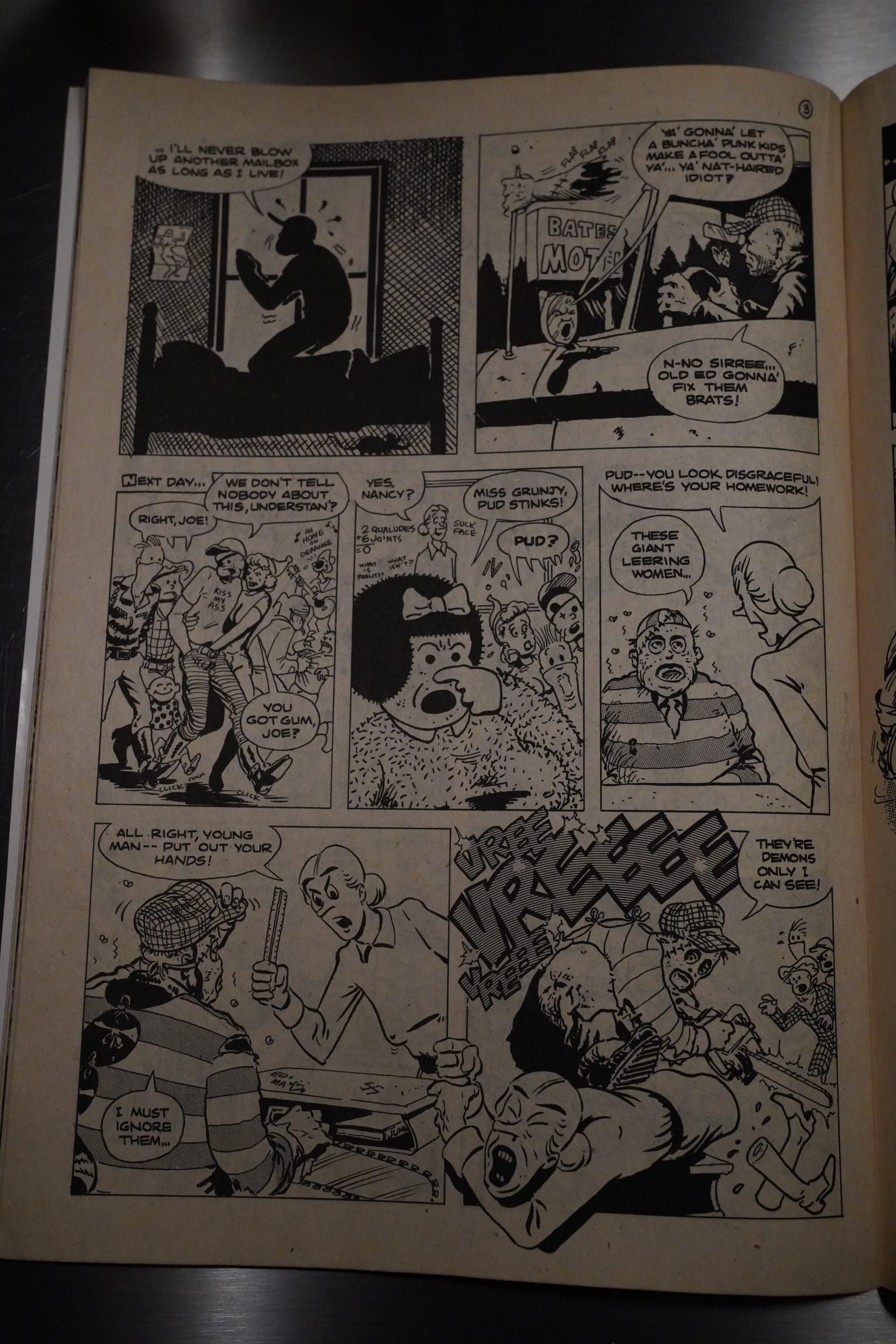

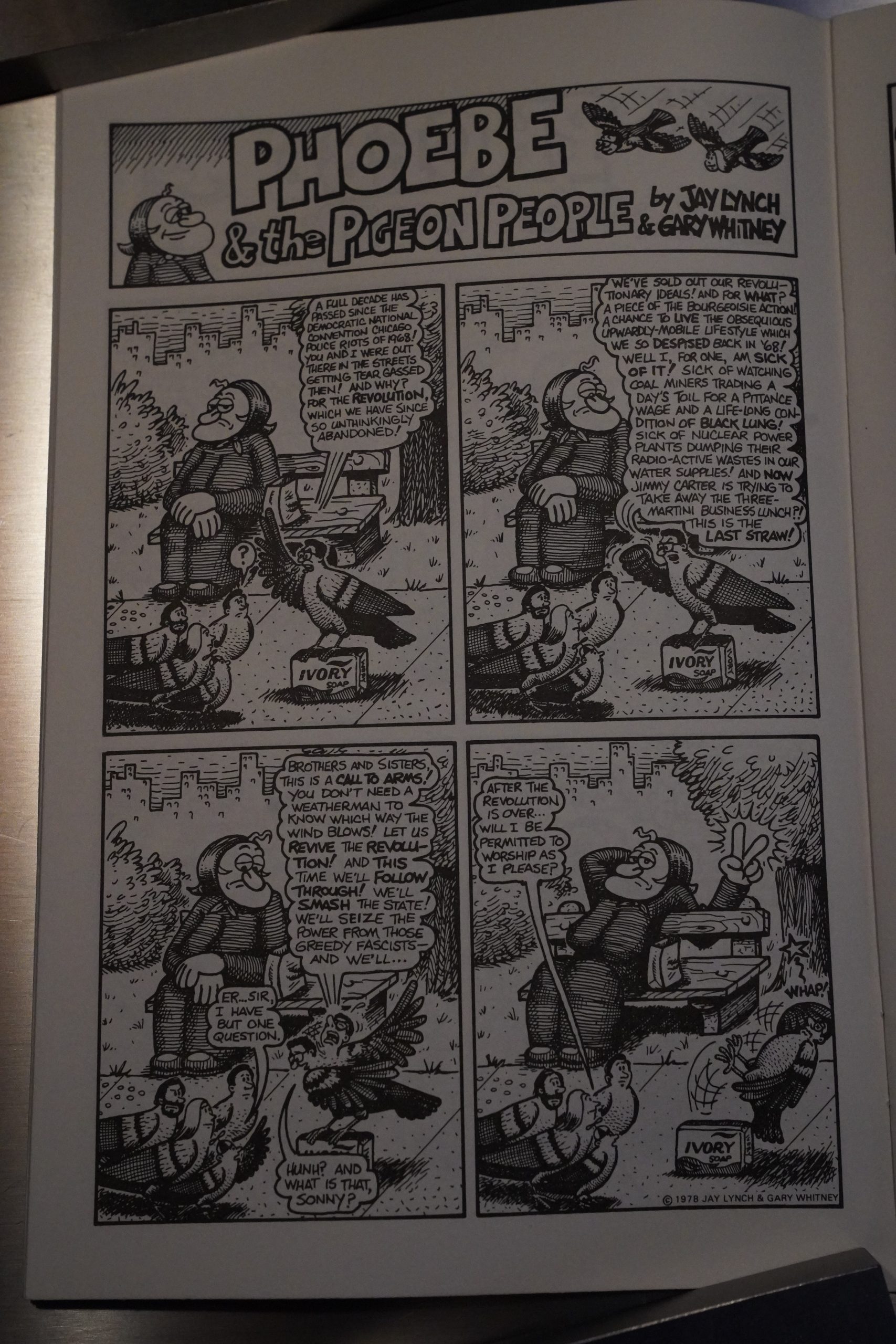

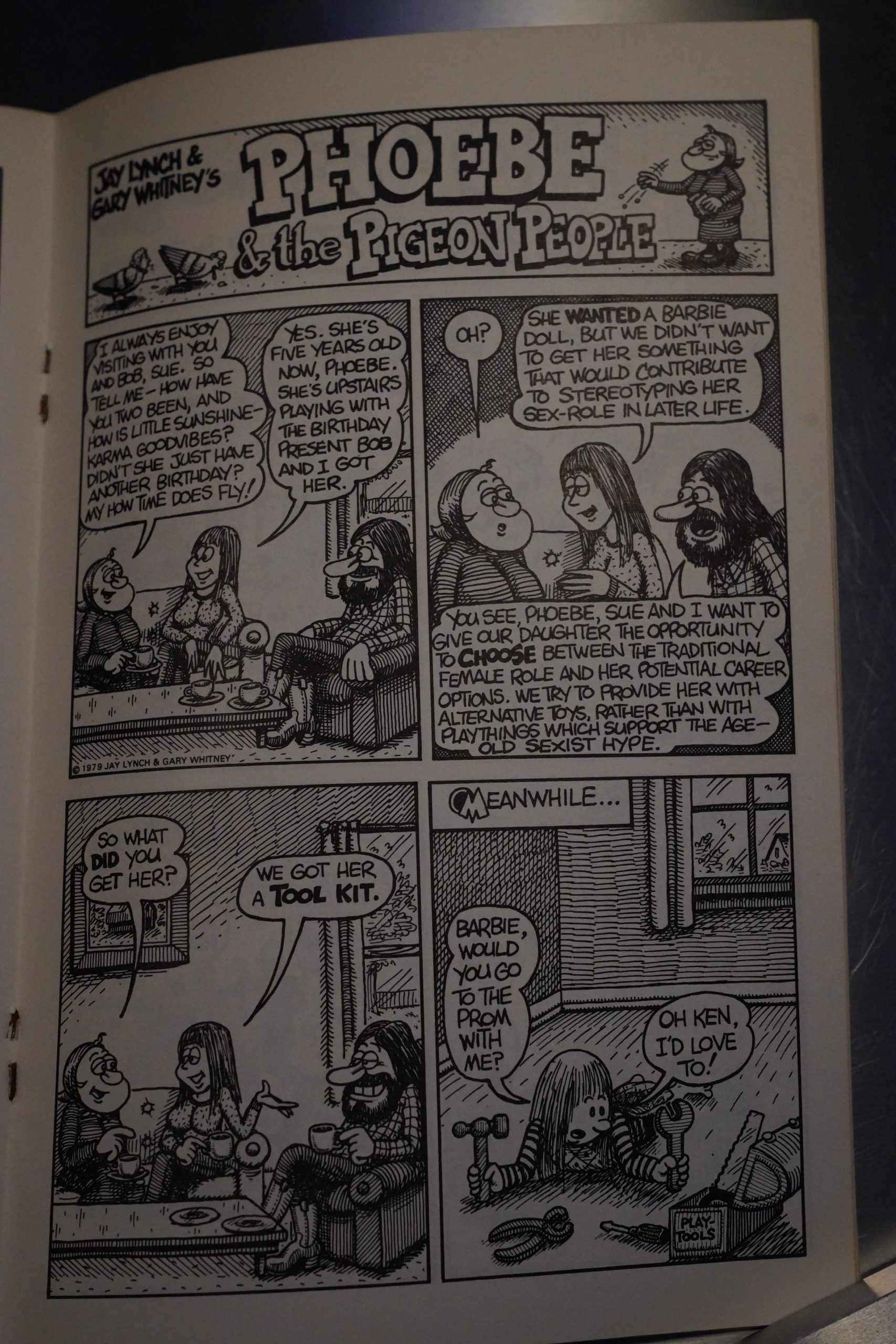

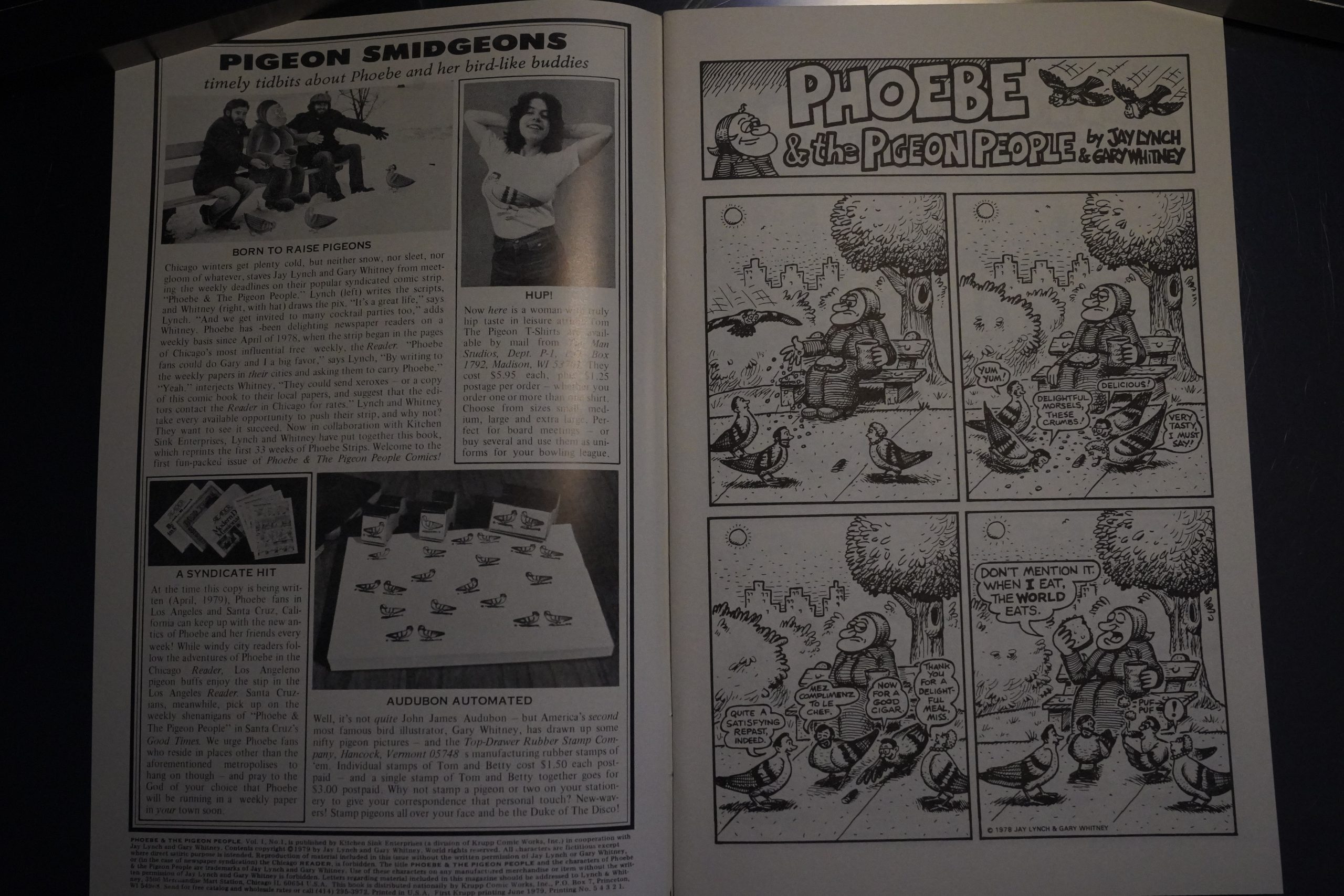

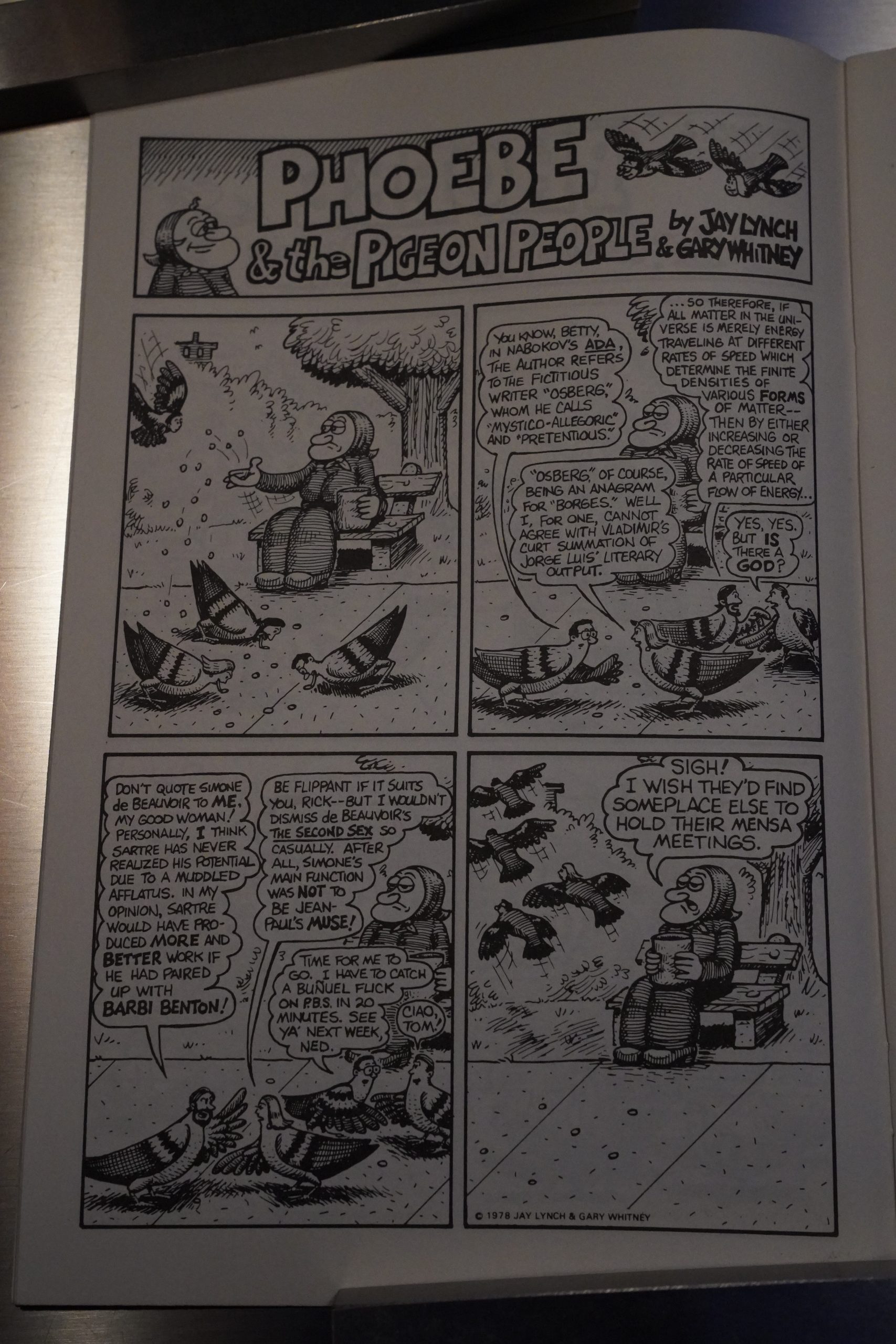

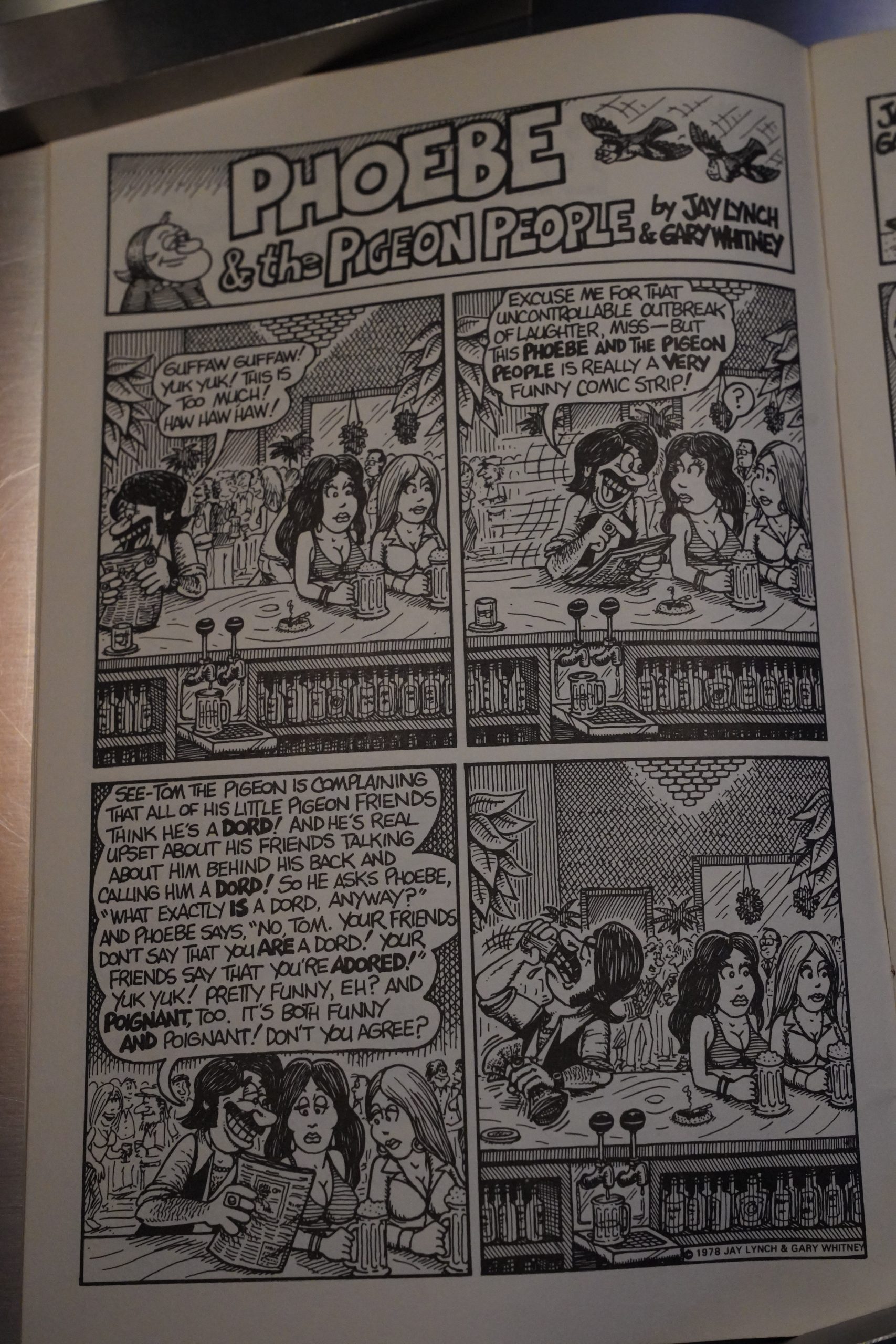

The concept is basically that there’s these pigeons with heads, and the Phoebe (the older woman) who feeds them. As concepts for strips go, that’s not too bad?

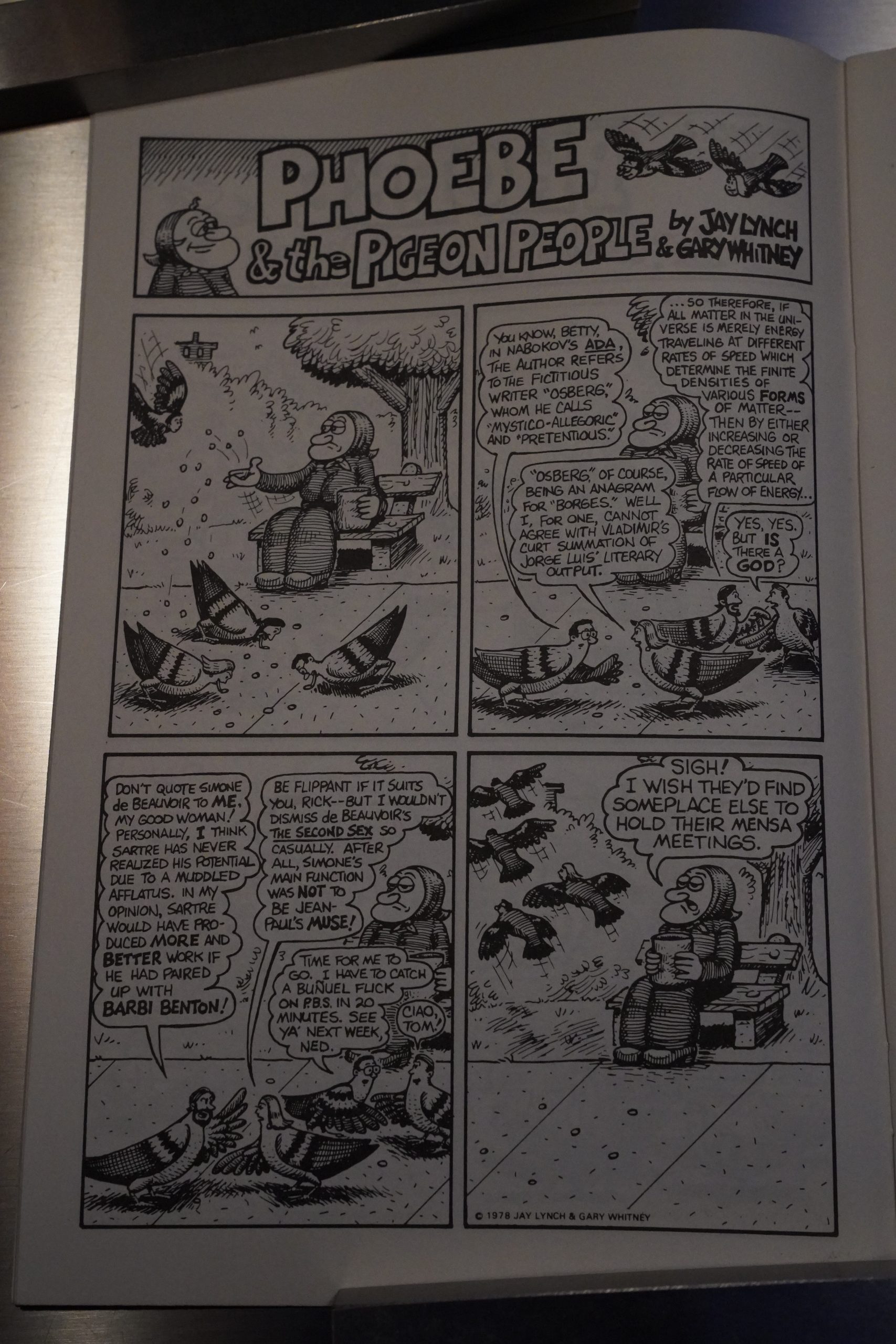

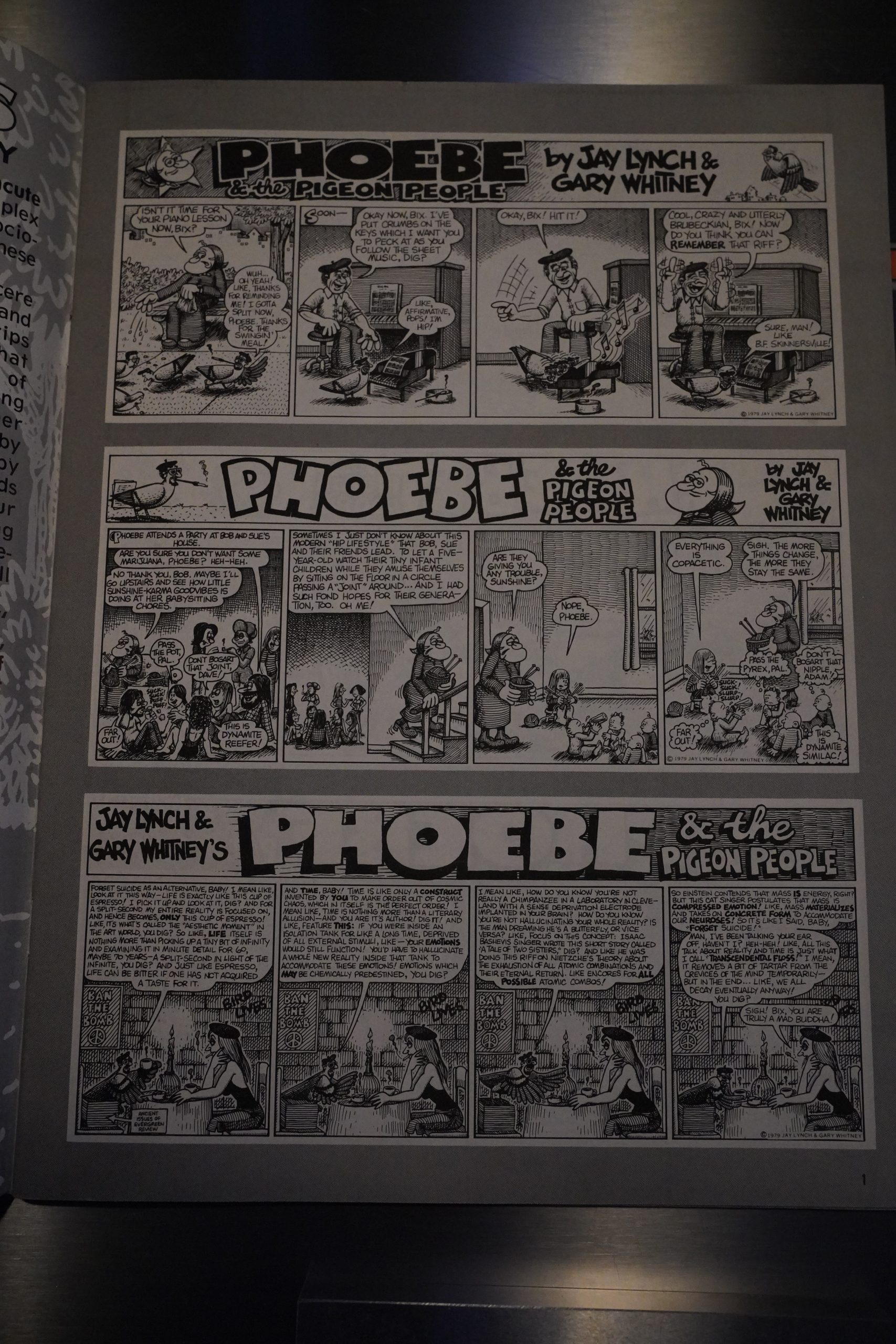

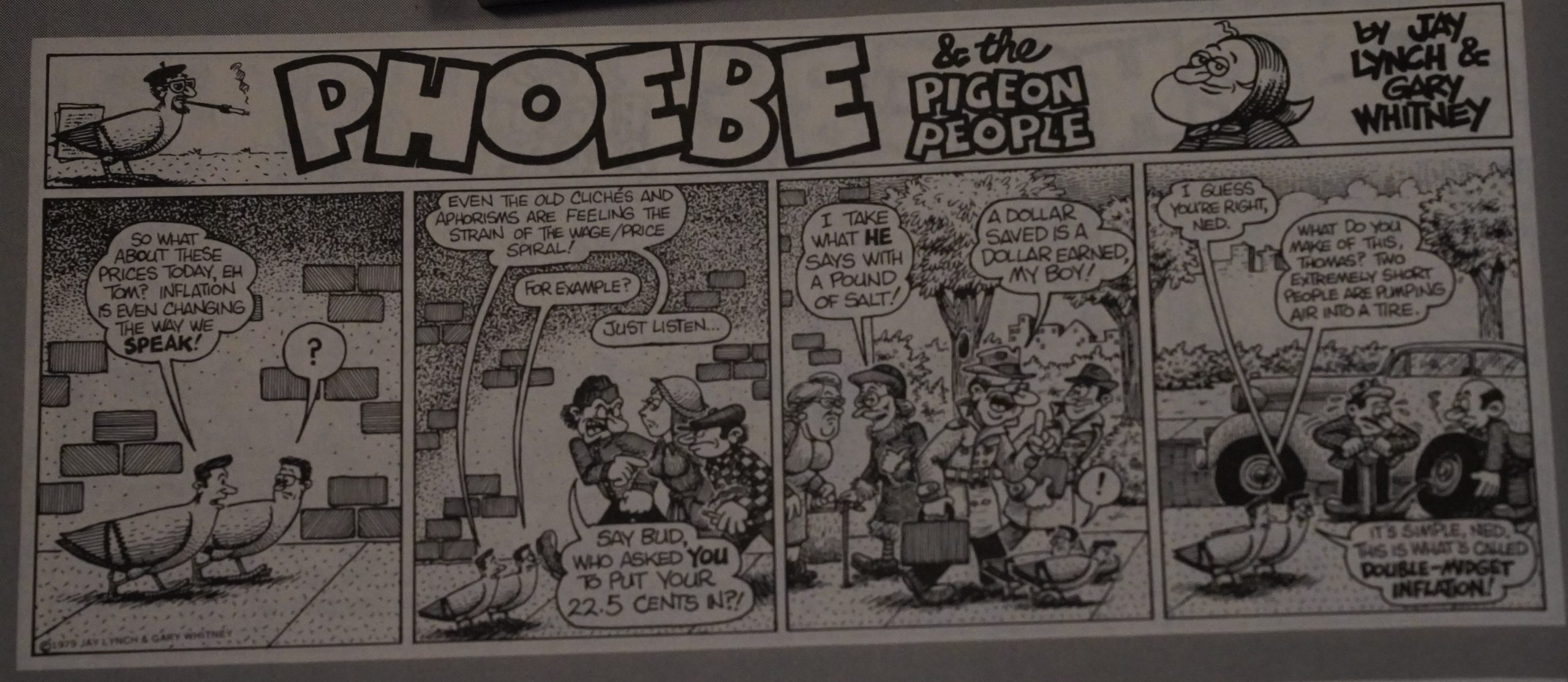

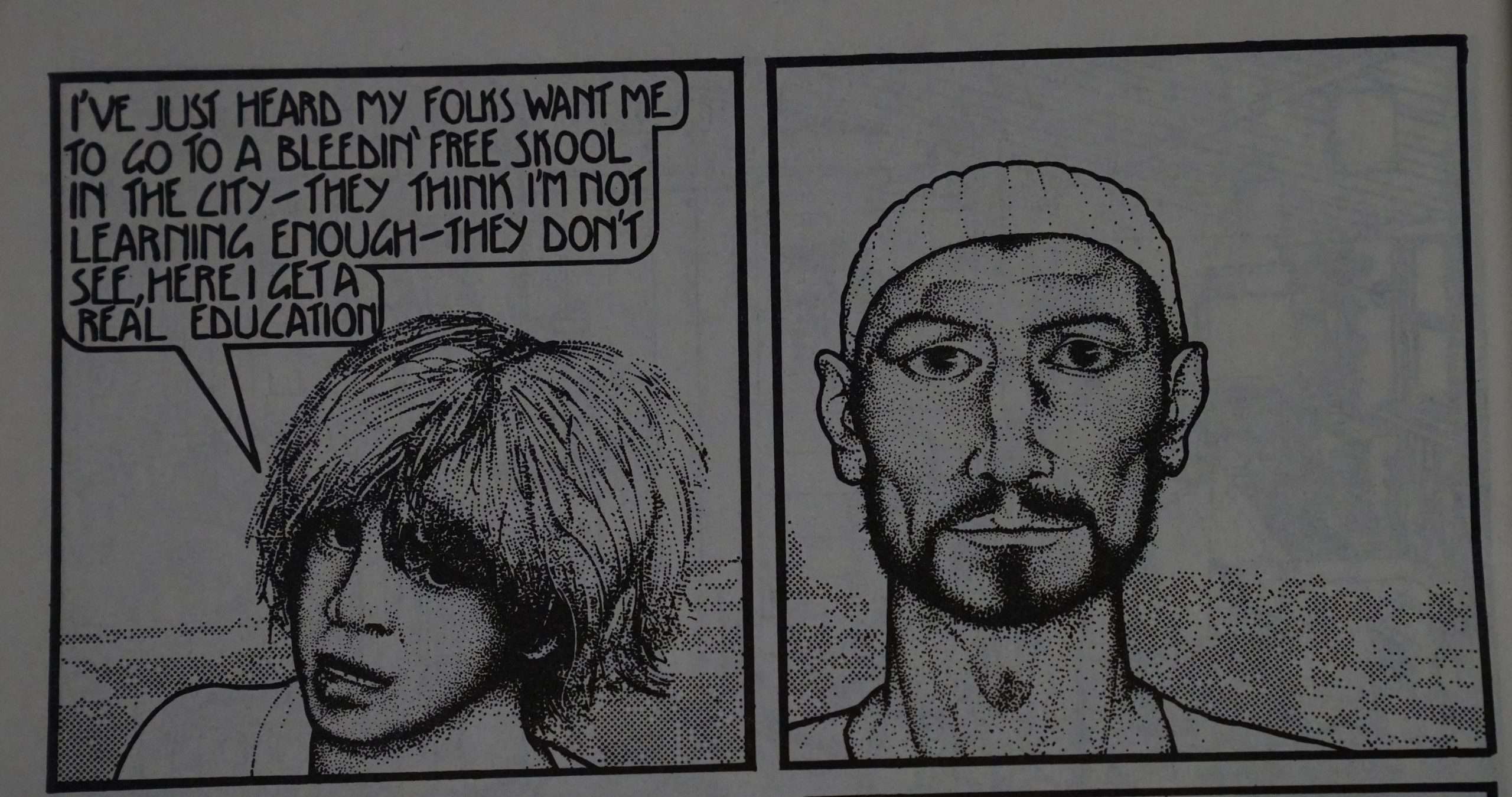

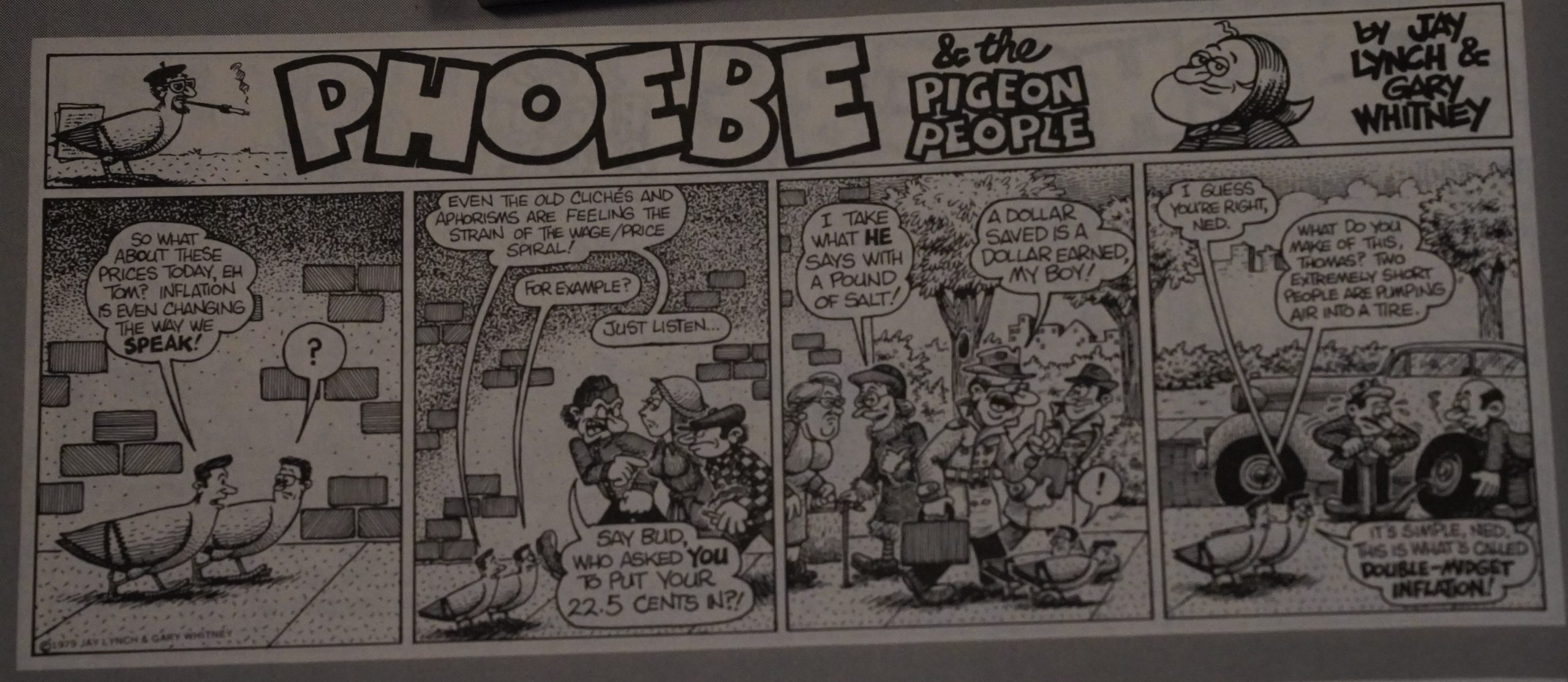

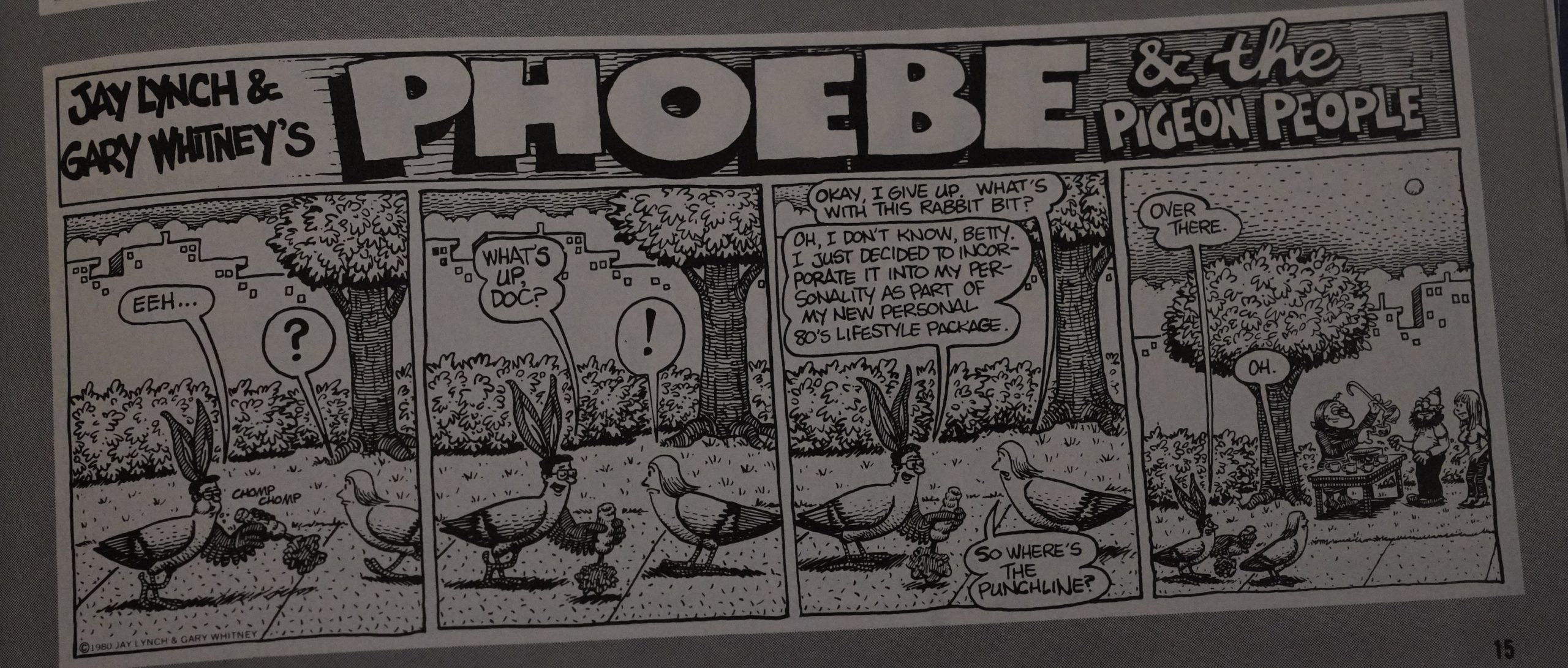

And it’s not that the gags aren’t amusing — but they certainly take their sweet time getting there. That is, the setups take quite a lot of effort for the reader to get through, and then the jokes are… there, but aren’t actually hilarious, so it feels like a let-down.

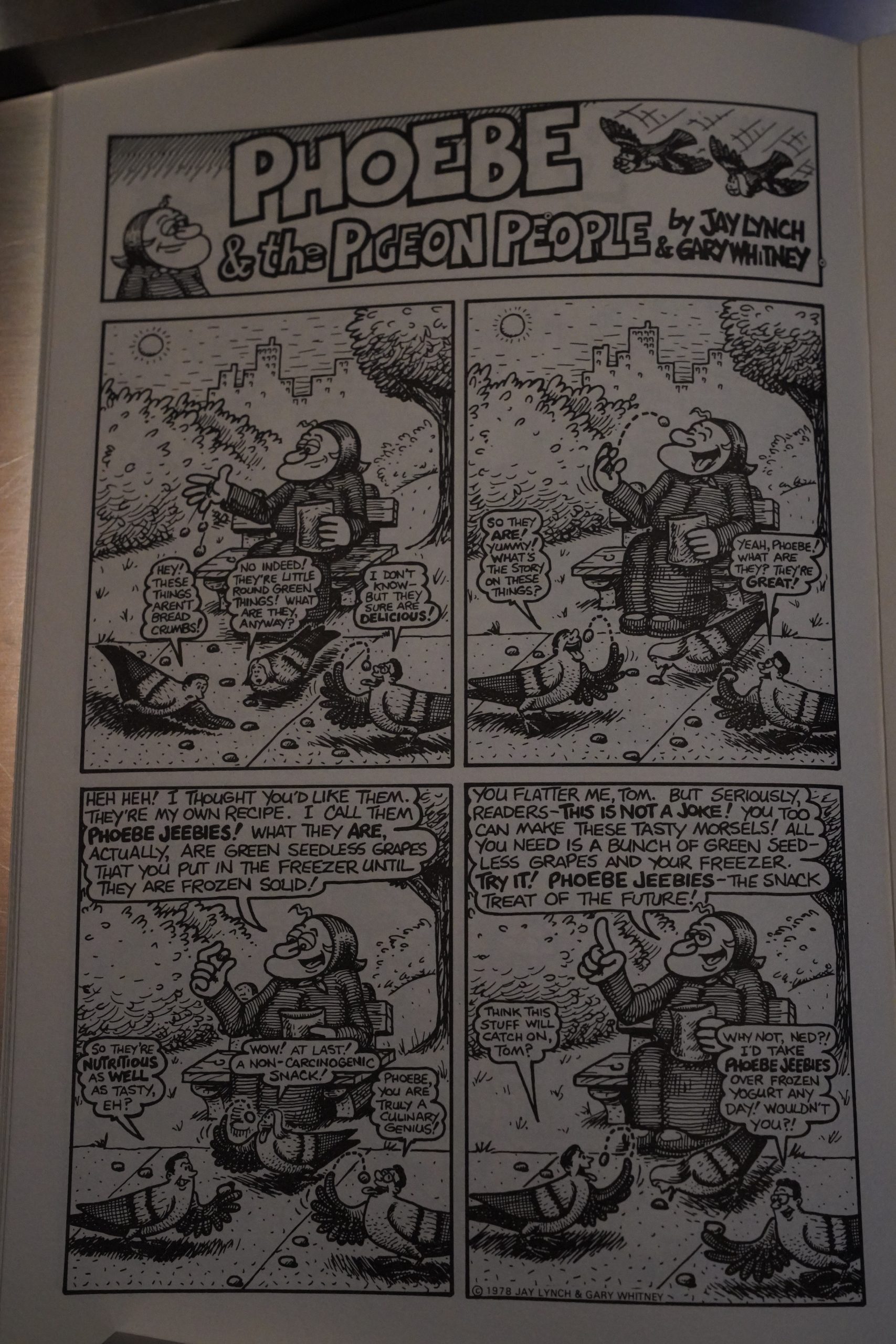

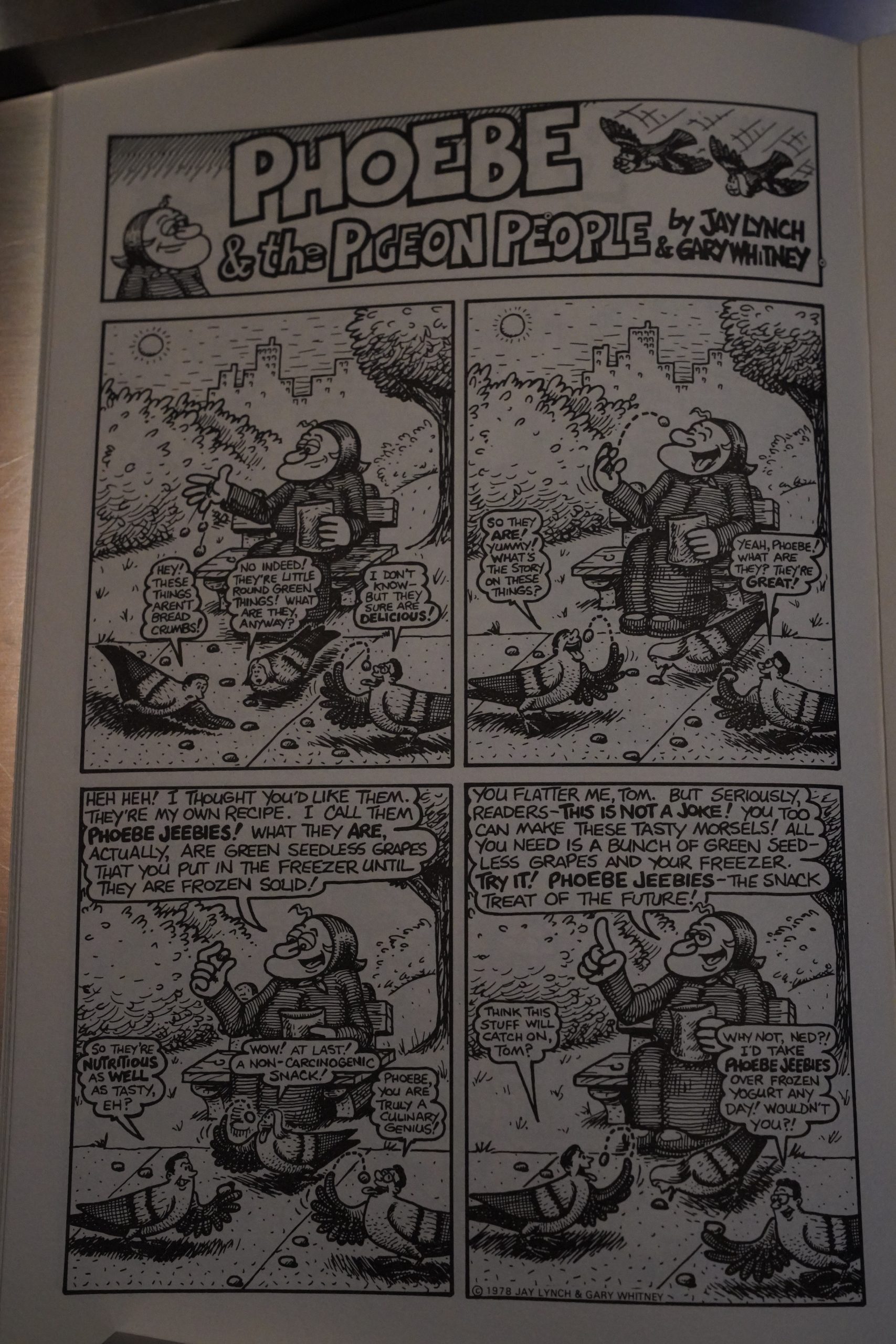

Hey! I remember doing that as a child. They got a kind of mushy, not totally stone hard texture? I have to try that again sometime.

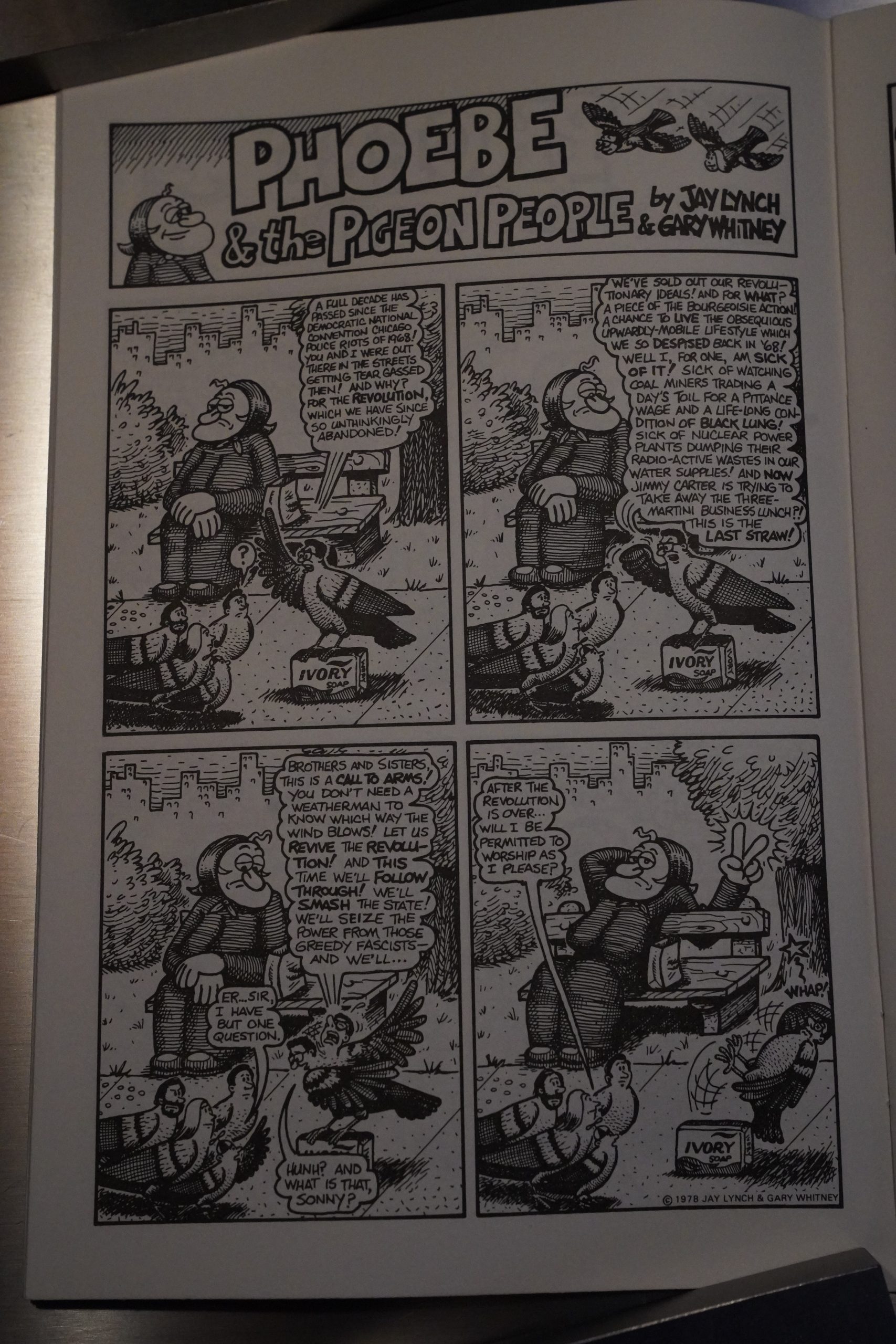

So topical.

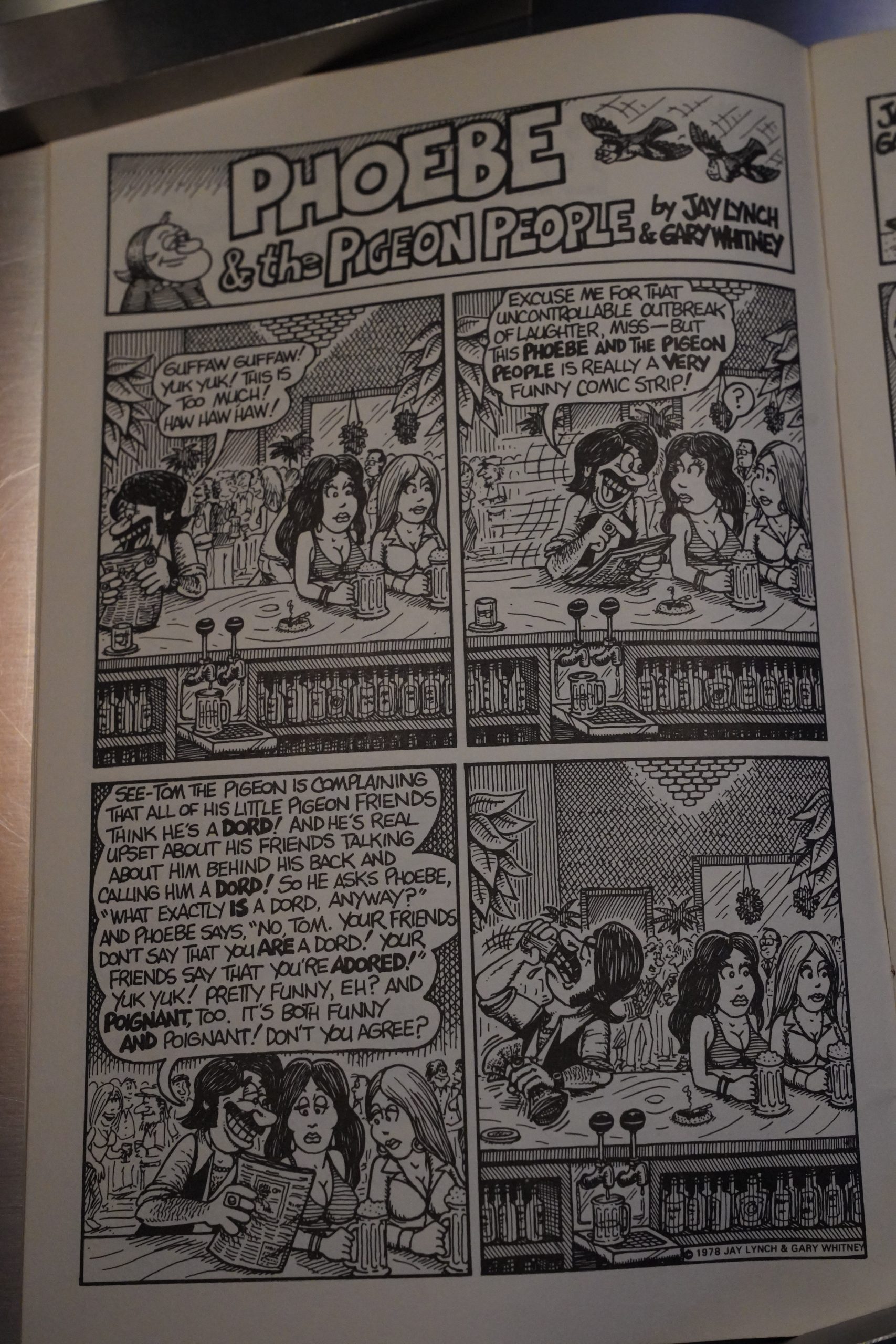

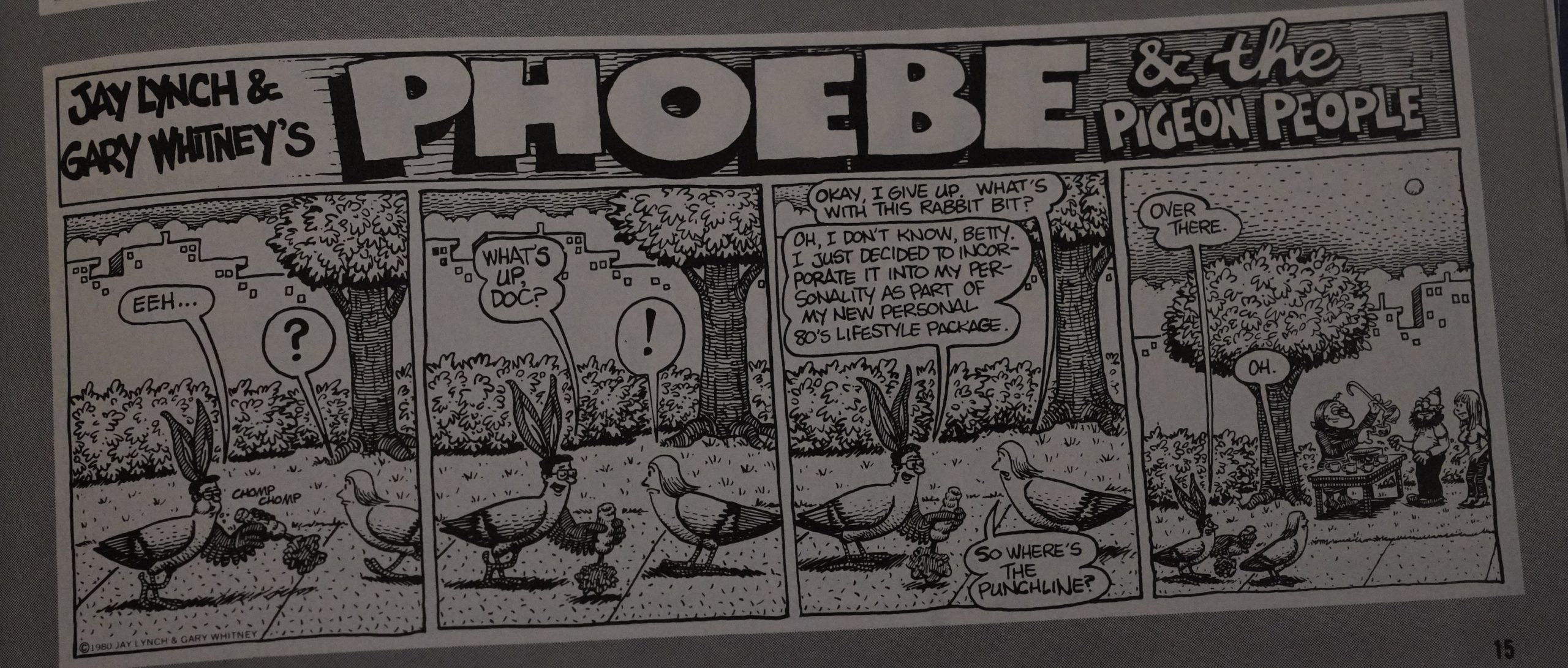

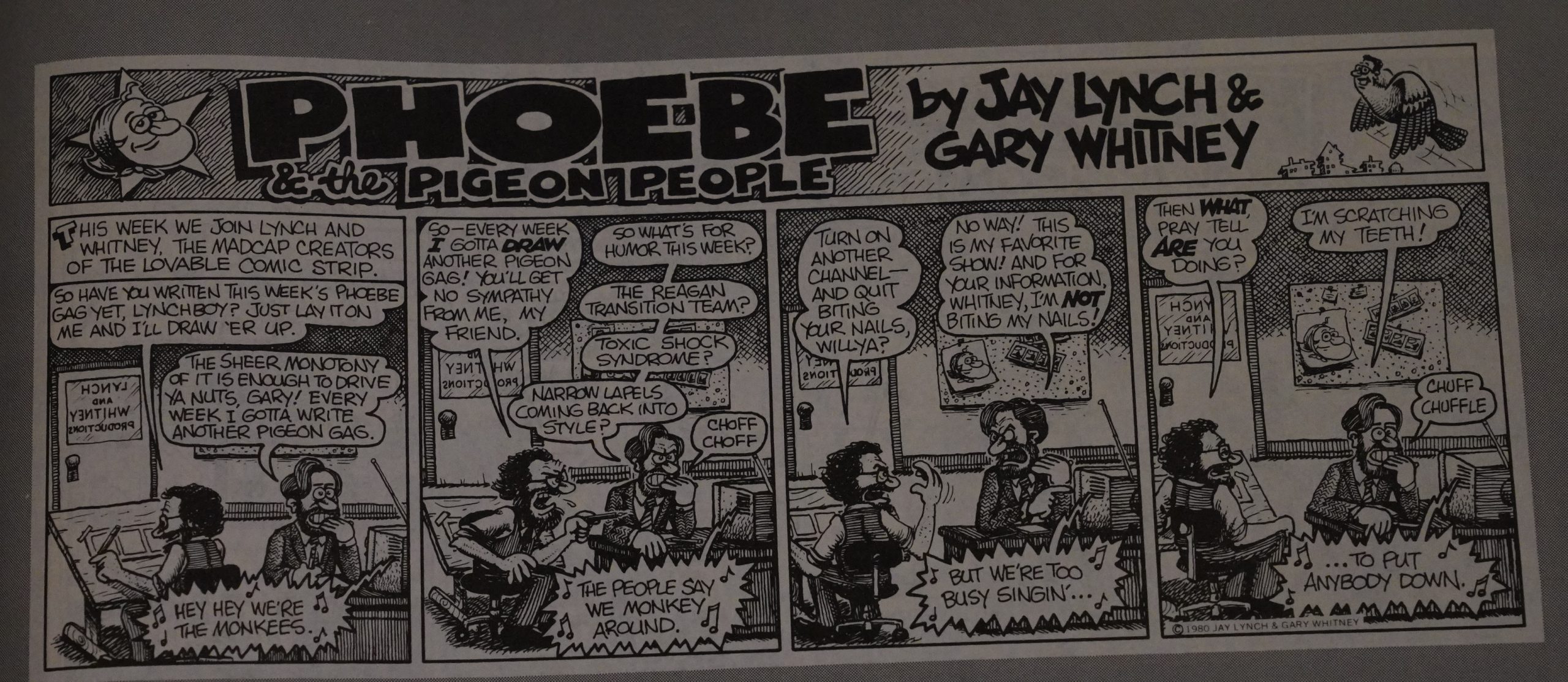

It doesn’t take many weeks for the artists to run out of possible jokes in the original setup, so we get a lot of strips about them not having any jokes this week, and things get kinda meta.

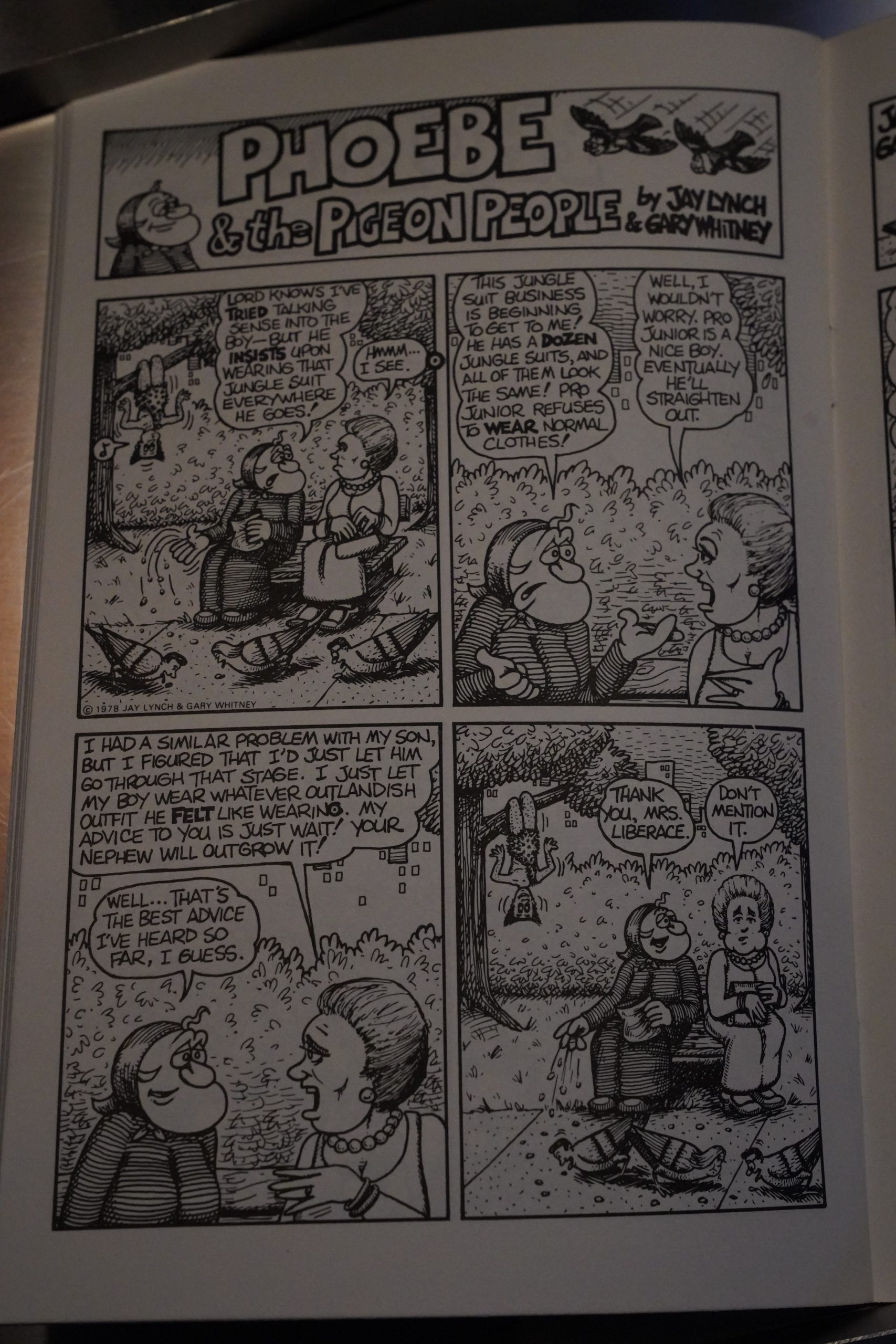

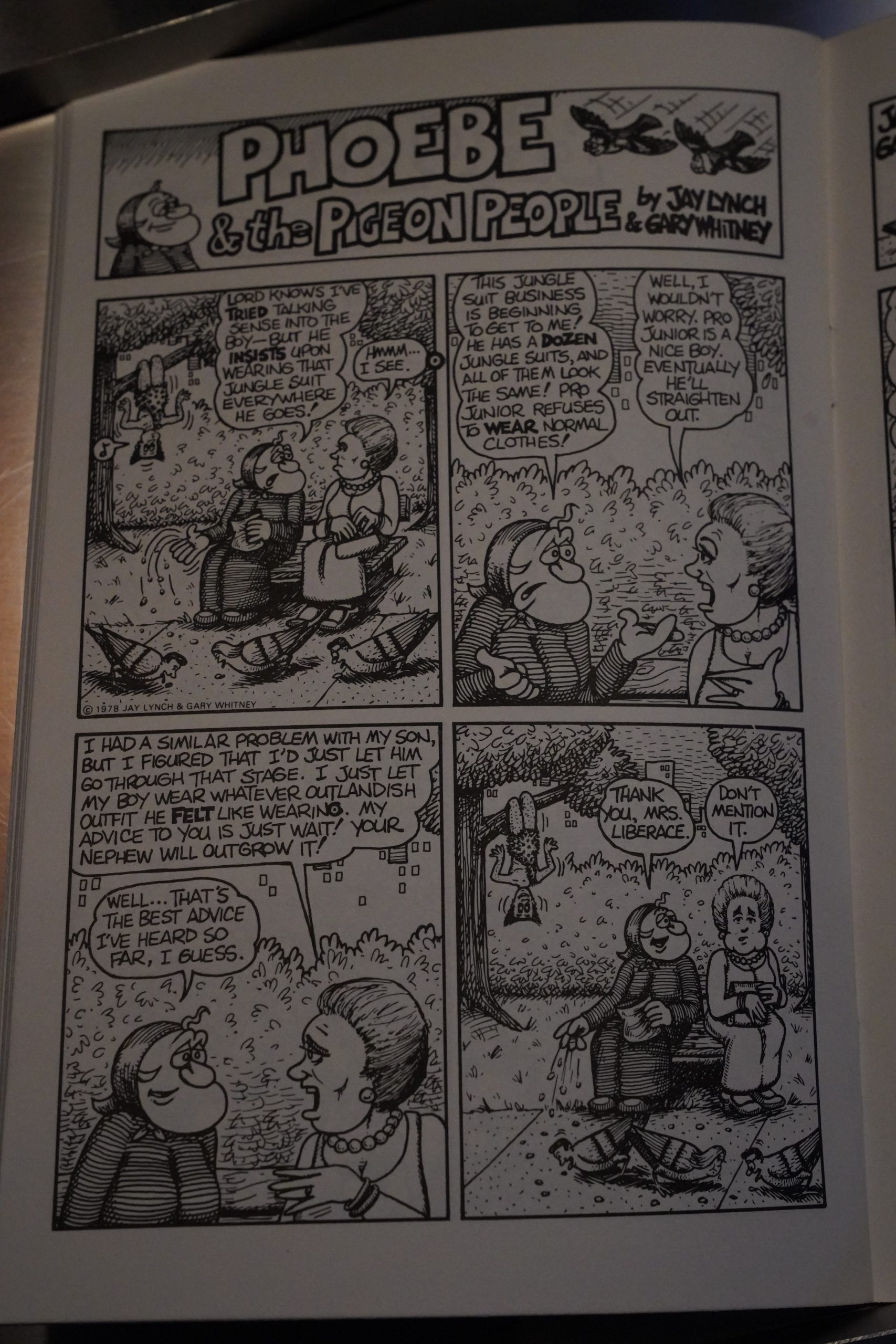

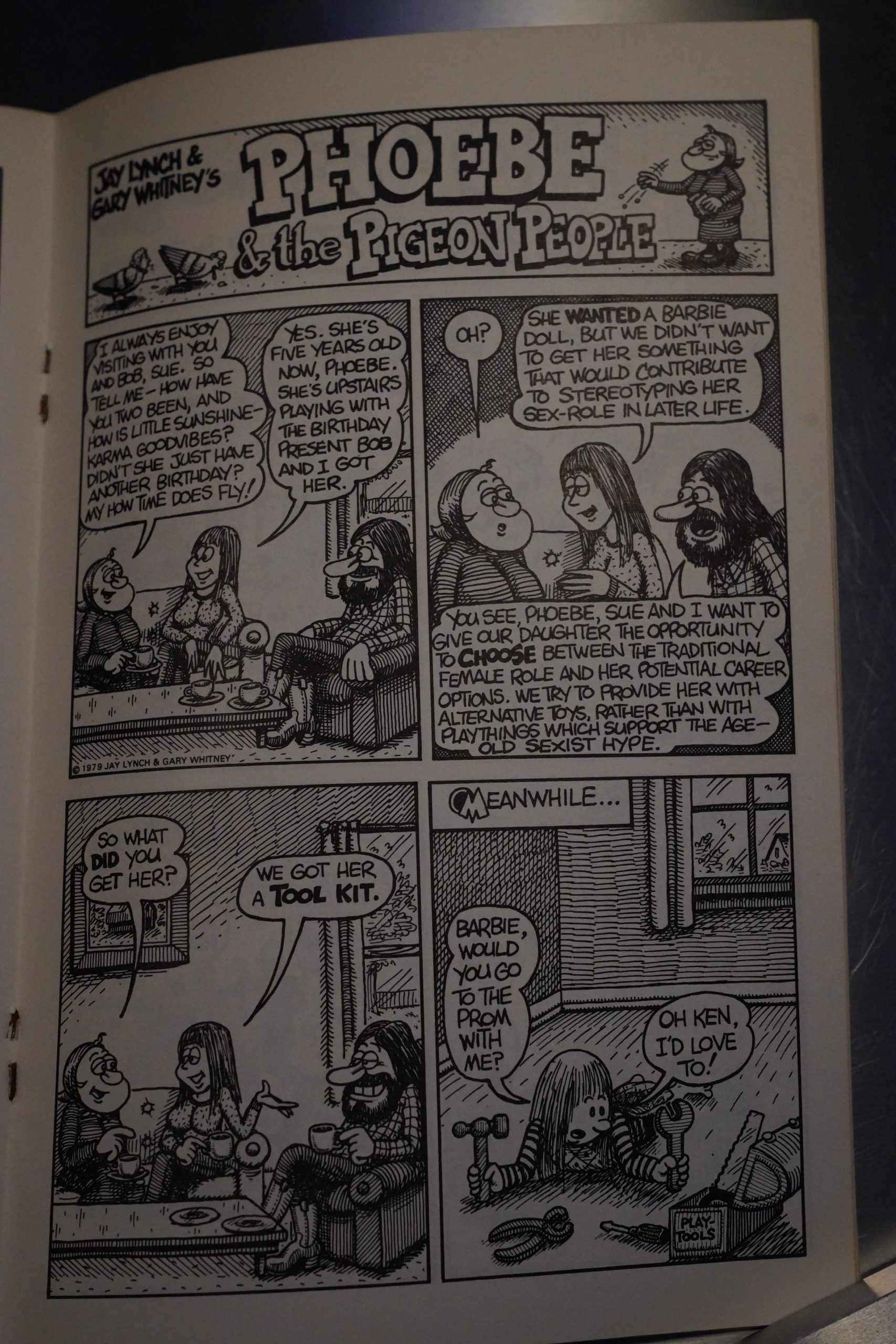

So incisive! I’m sure I haven’t seen that gag a million times before.

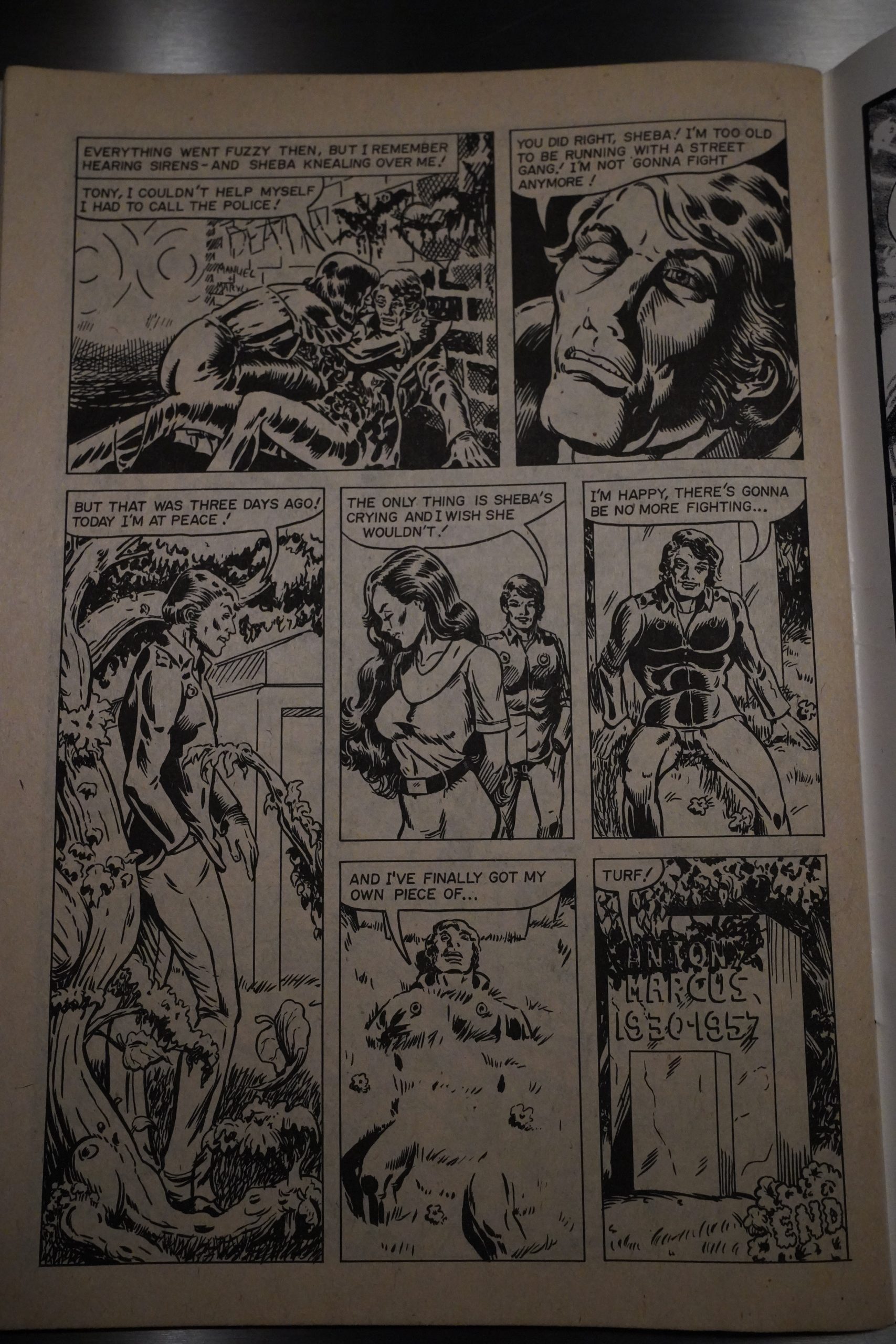

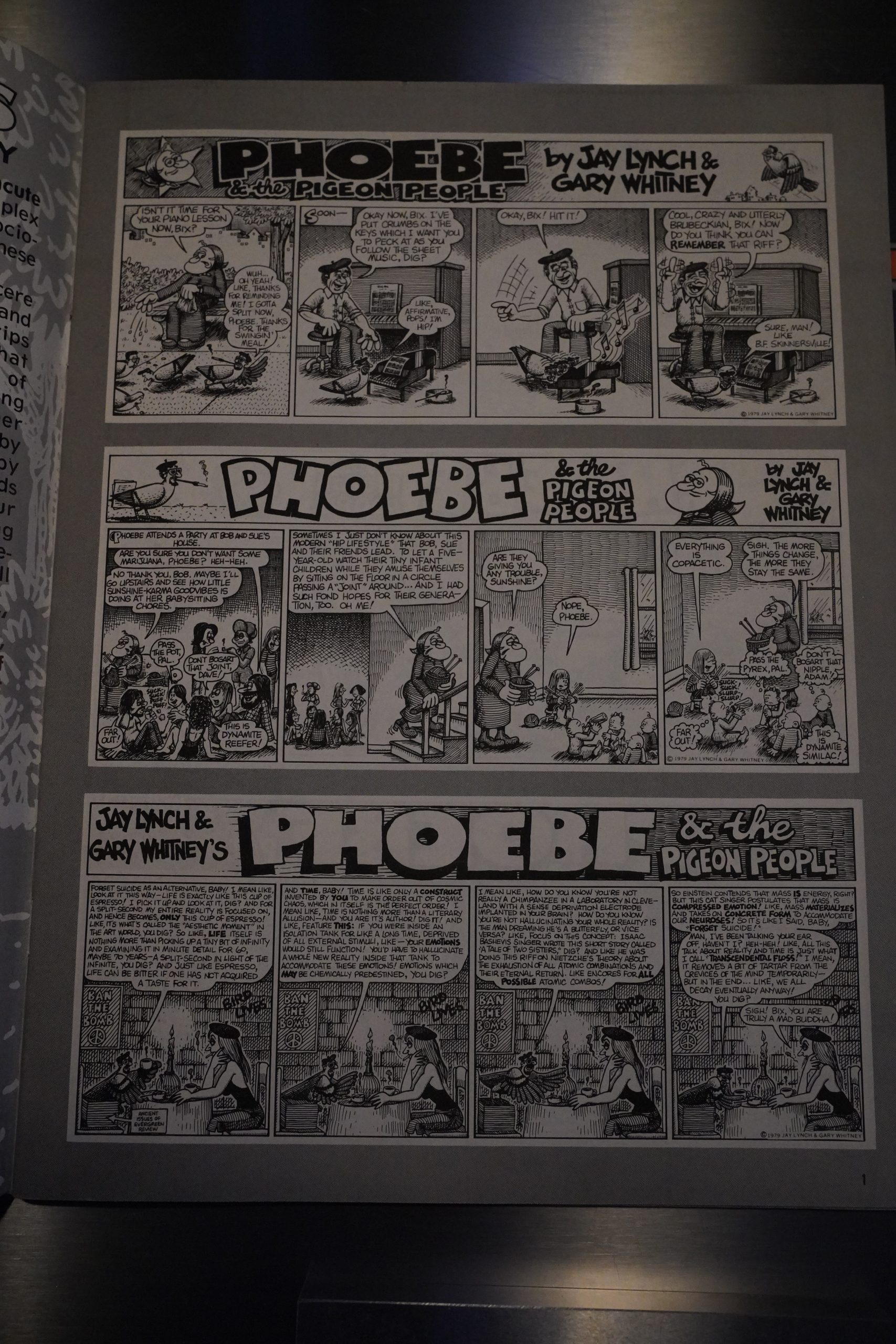

The first two issues were printed in a very attractive digest-like size. Cute and displayed the strips to their advantage. The third issue is magazine sized, and the strips are arranged horizontally instead. (All the panels are the same size to allow rearranging, presumably? Just like Peanuts.)

The problem is that the strips are printed in a smaller size here, so the strips with the most verbiage just become a sort of grey haze.

*groan*

*double groan*

There’s a lot of strips like these. I think the problem is that the creators didn’t really manage to come up with character for their characters. I mean, they try to differentiate them by giving them sort of individual schticks that can pass for personality if you squint, but they aren’t personalities that naturally give rise to gags; that generate storylines and fun in themselves. So they have to come up with some random word play and try to shoe horn it into this format.

Which explains all the strips about not being able to come up with any gags.

Peanuts this ain’t.

Lynch is interviewed in The Comics Journal #114, page 87:

GREEN: In the underground comix you Wrote

and drew the adventures of the characteß

Phoebe The Pigeon people, which appeals

weekly in The Chicago Reader newspaper.

How does the writing of a weekly strip differ

from the writing of comic book stories?

LYNCH: Well, Phoebe has to be a joke a

week. It’s a different thing than Nard ‘N Pat

in that Nard ‘N Pat was long stories with

a lot of dialogue, and those stories didn’t

necessarily have to have punchlines. Phoebe

pretty much has to have a punchline every

week. Even if we get involved in a continui.

ty situation in Phoebe, there still has to be

a gag a week in addition to the continuity.

Gary Whitney draws Phoebe. I just write it.

With Nard ‘N Pat, I drew many hundreds

of panels of a man, a cat, and a chair. When

I had the idea for Phoebe about nine years

ago, I didn’t want the tedious task of draw-

ing it because originally—for the first year

or so—it was just a woman, a bench and

some pigeons. Then I met Gary, and we

combined forces. After the first year, Phoebe

got up off the bench, and now the strip has

evolved, and there are dozens of regular

characters in it. It’s a whole little universe

unto itself.

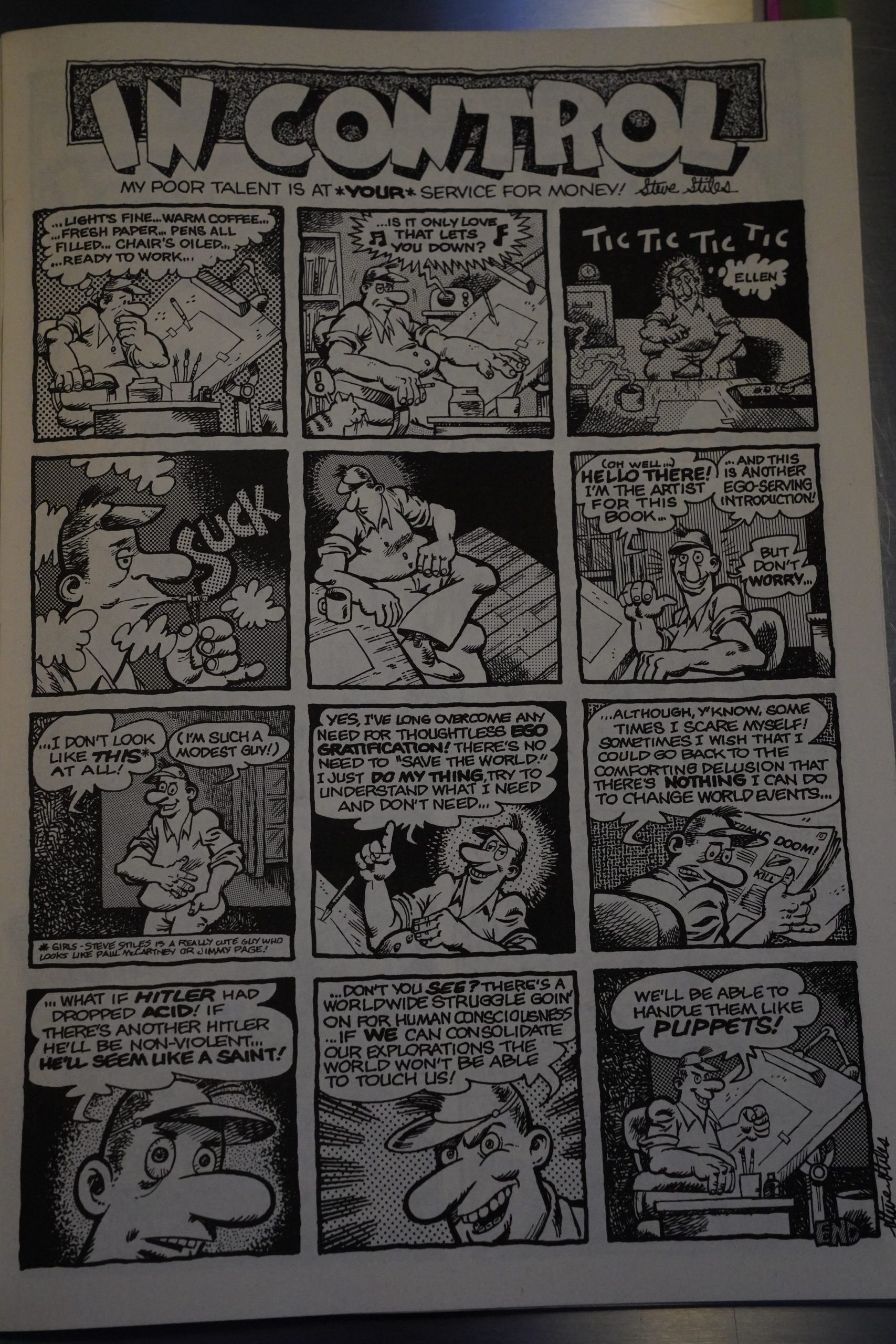

YOE: What is this ‘ ‘You get what you draw”

philosophy of

LYNCH: Well, lately I ‘ve been into this idea

that drawing a comic strip is a form of vi-

sualization, and.. .Why don’t we just reprint

this thing from the Chicago Reader’s letter

column here. One of the readers corn.

plained that Gary and I drew ourselves in.

to the strip wearing tuxedos and appearing

too wealthy-looking, and we answered him

by articulating our “You get what you draw”

theory.

YOE; So have there been any positive benefits

to this ‘ ‘You get what you draw” thing?

LYNCH: I don’t know if we can use our

Oowers for our own personal gain, but.. –

Well, in the ’60s we advocated that the war

in Viet Nam should end—and it did.

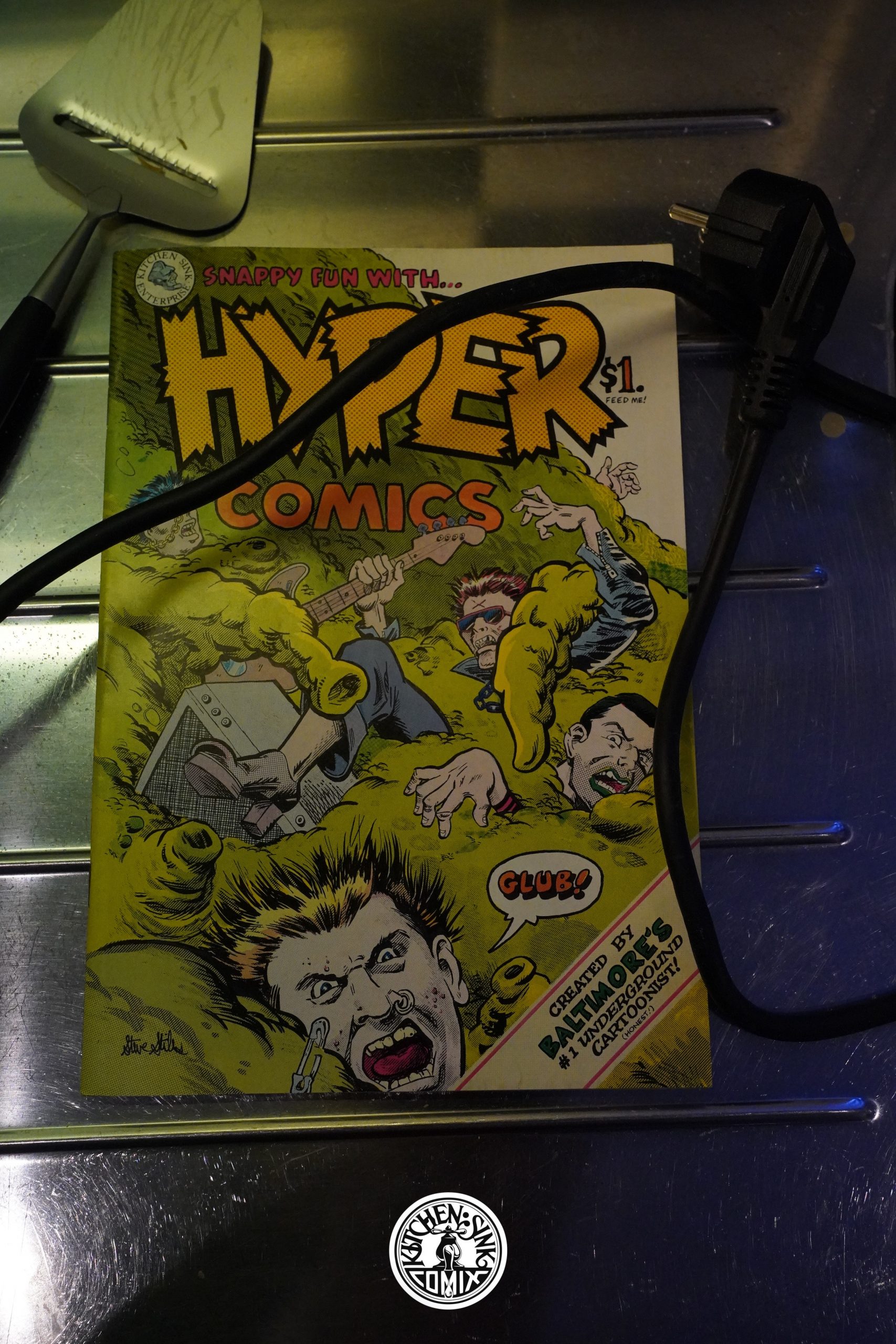

A complete collection was published in 2017 by Alternative Comics.

This is the fifty-fourth post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.