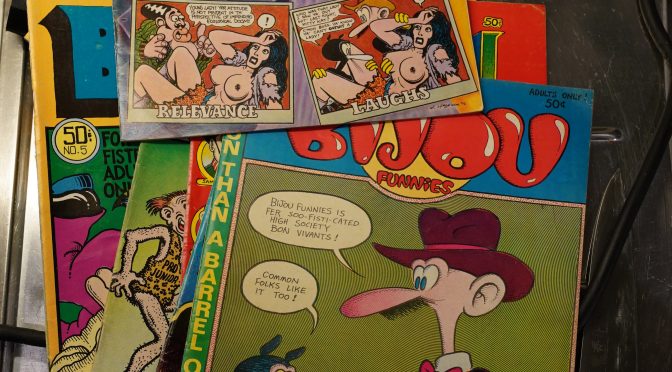

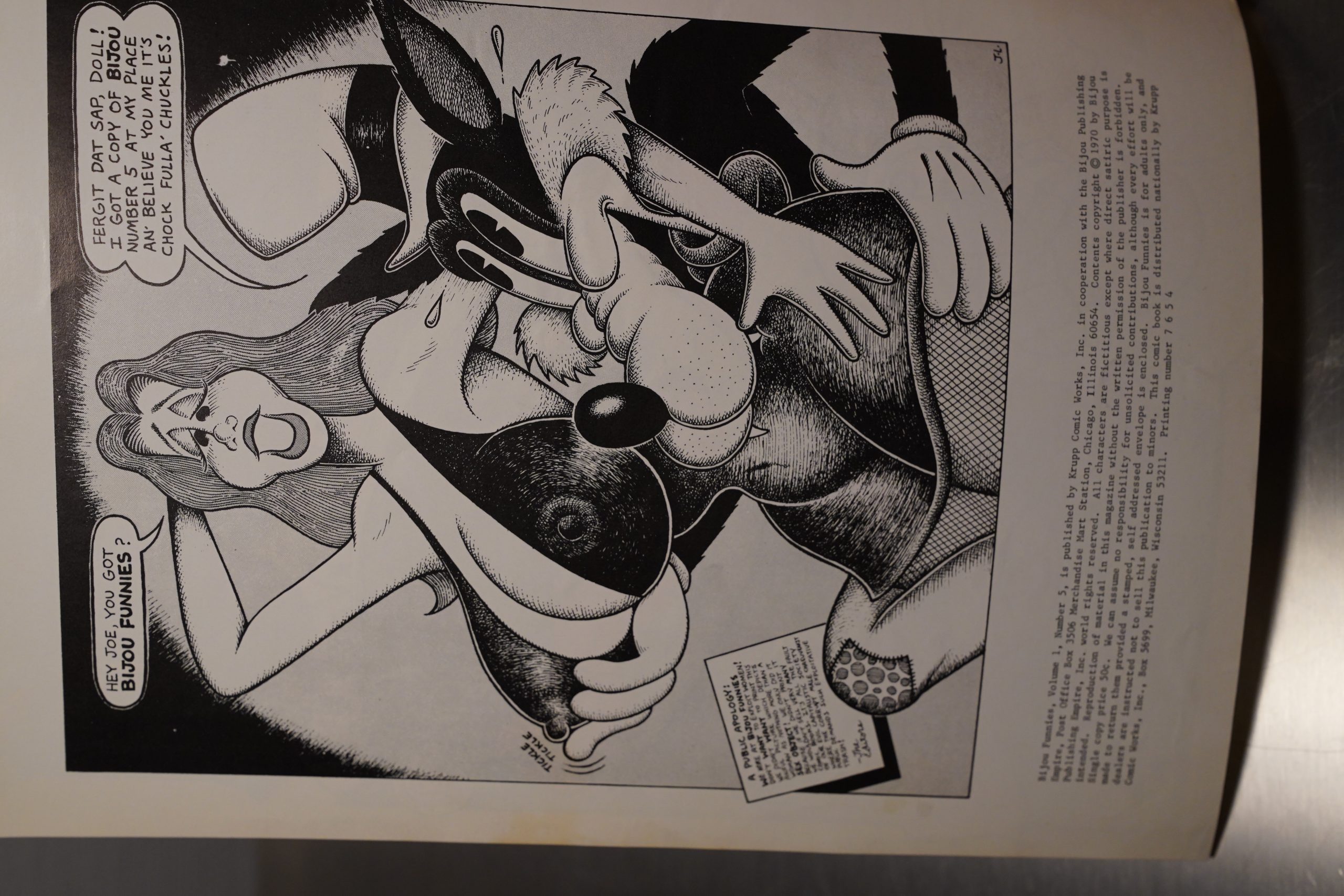

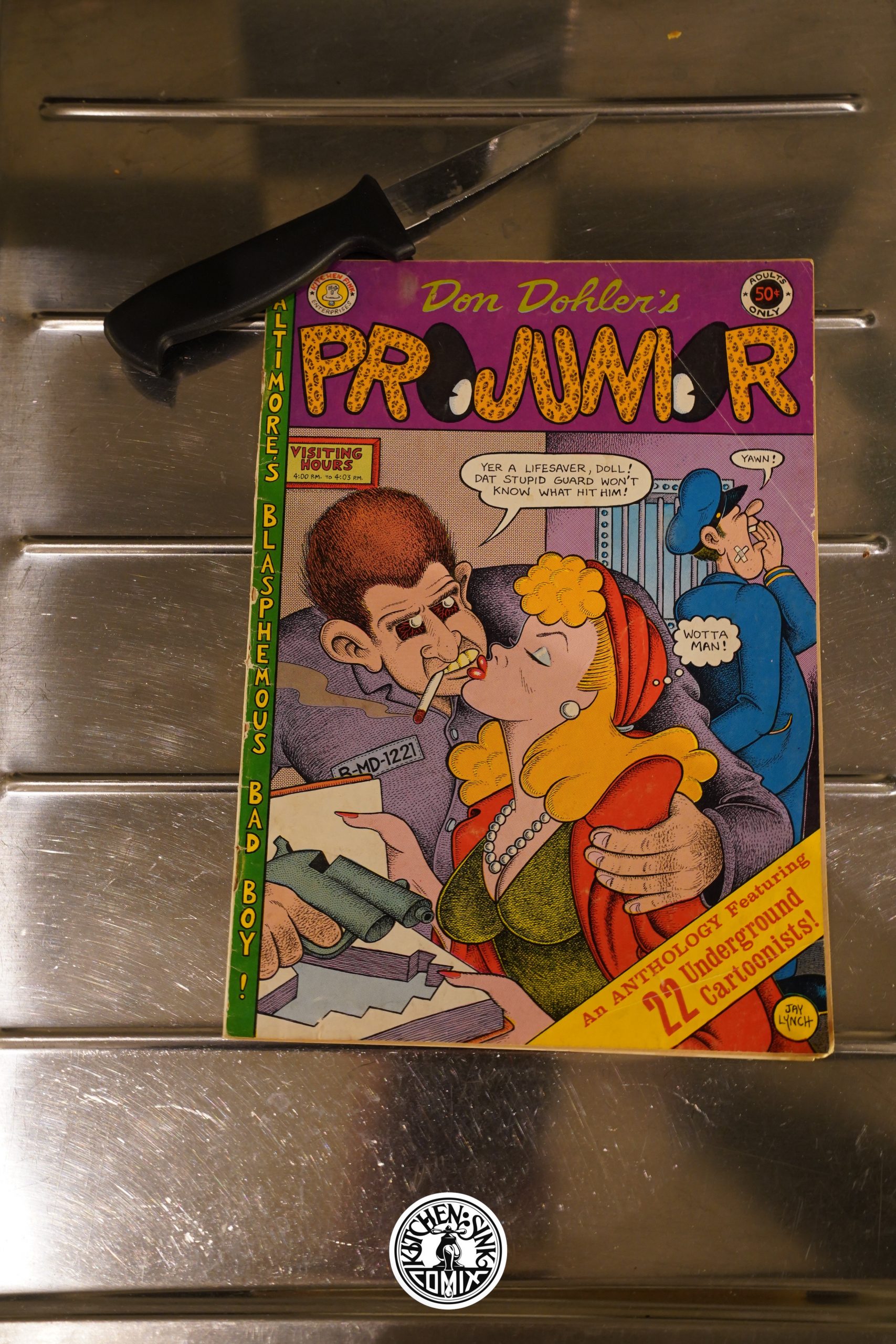

Bijou Funnies (1972) #1-8 edited by Jay Lynch (I think)

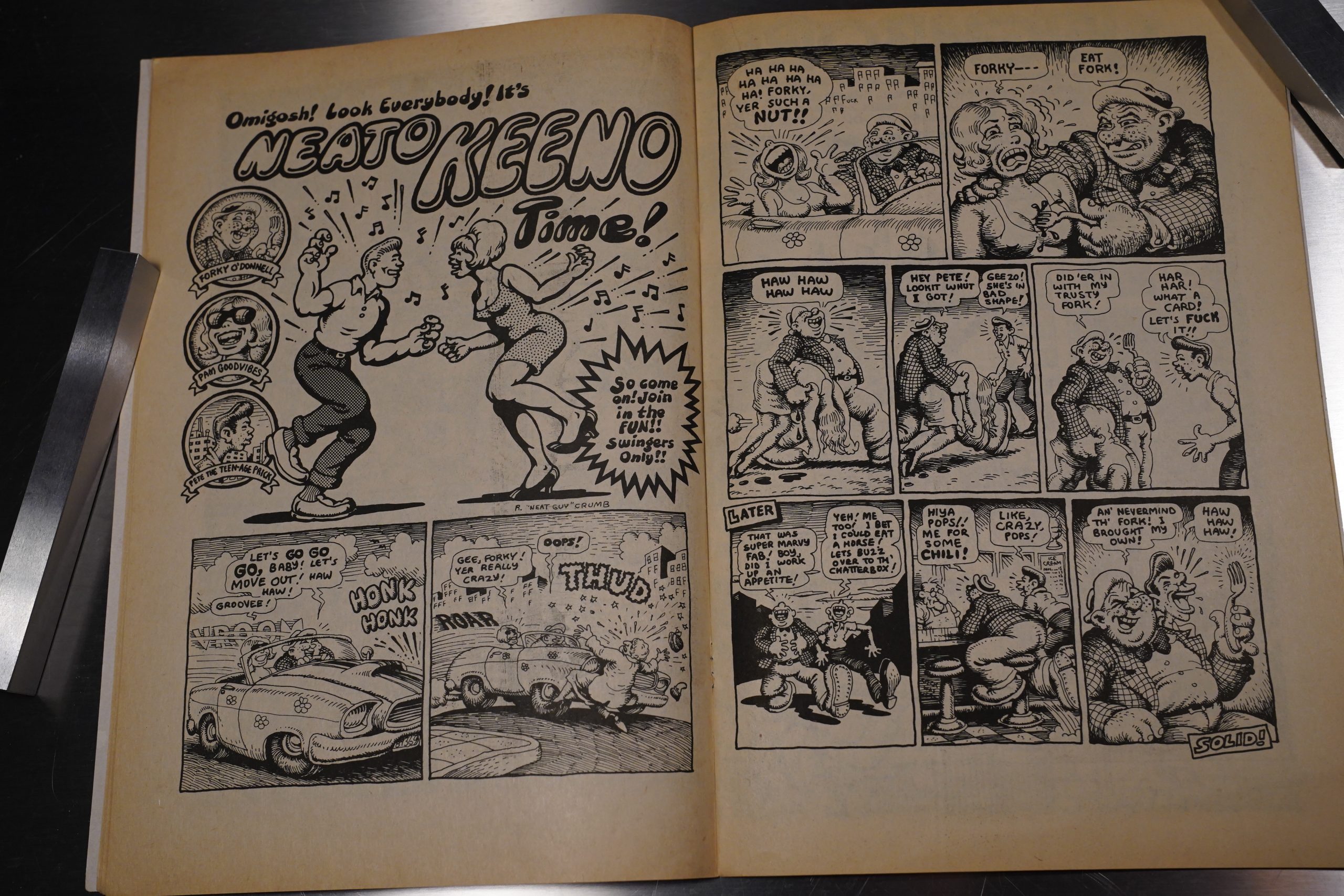

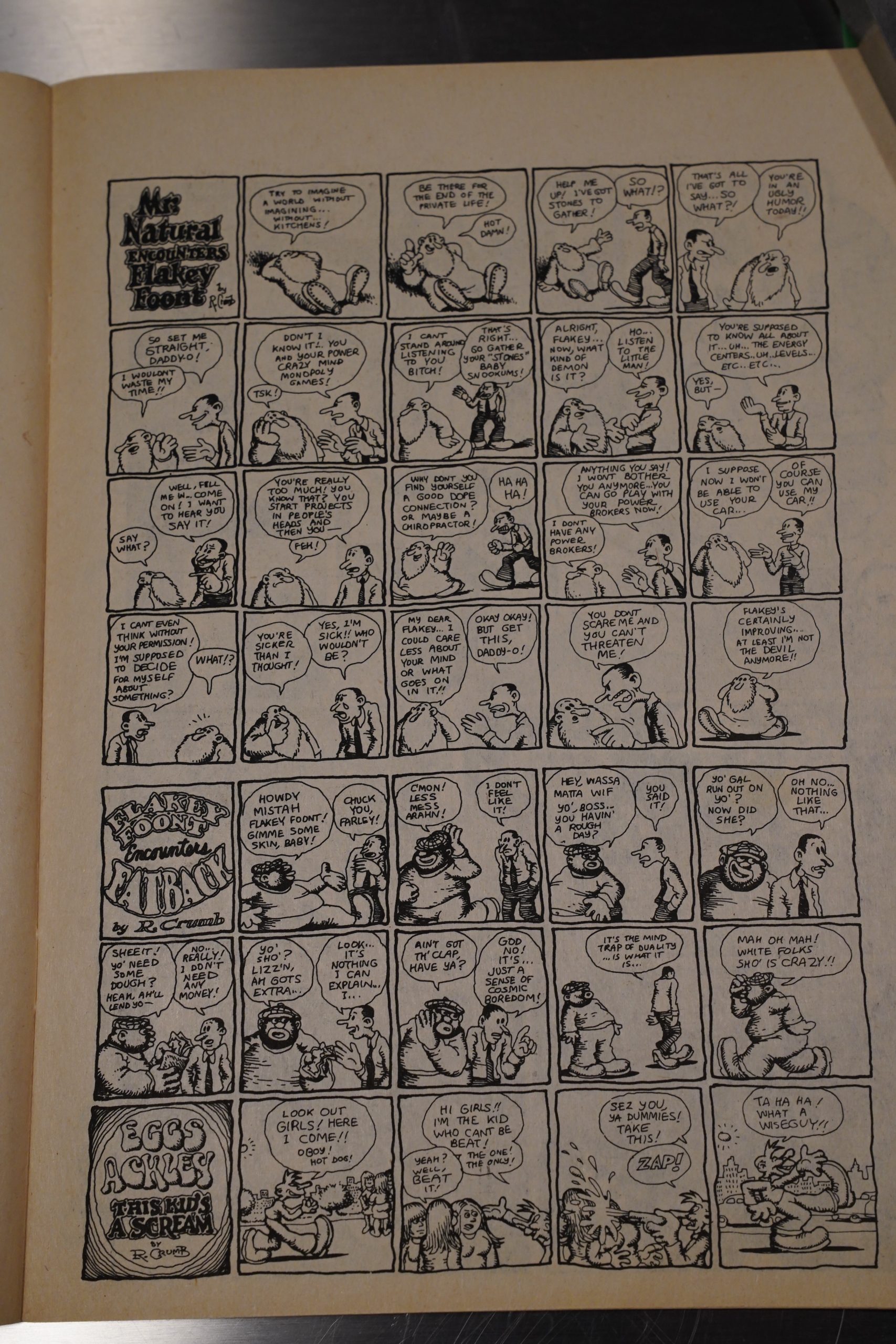

Bijou Funnies was one of the very first underground anthologies, arriving hot on the heels of Zap (which wasn’t an anthology yet, I think?), and also featured R. Crumb.

But it’s not really one of the more notable books? I mean, I’ve heard it mentioned a bunch of times, but mostly as a kind of fore-runner to Arcade, i.e., as the template for a non-California underground anthology… featuring Art Spiegelman.

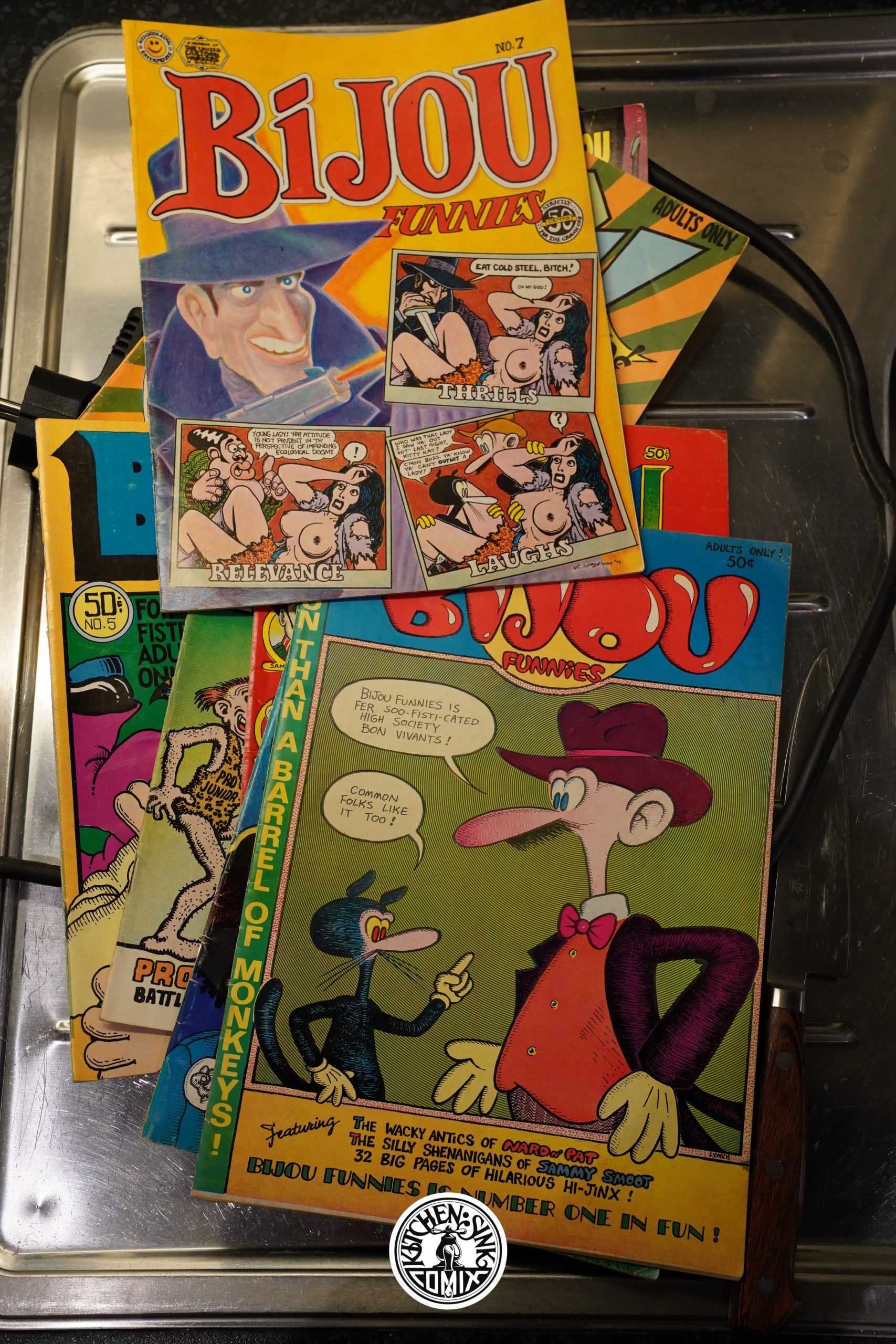

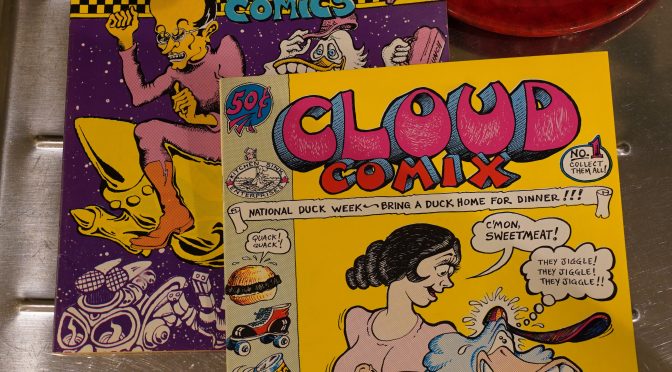

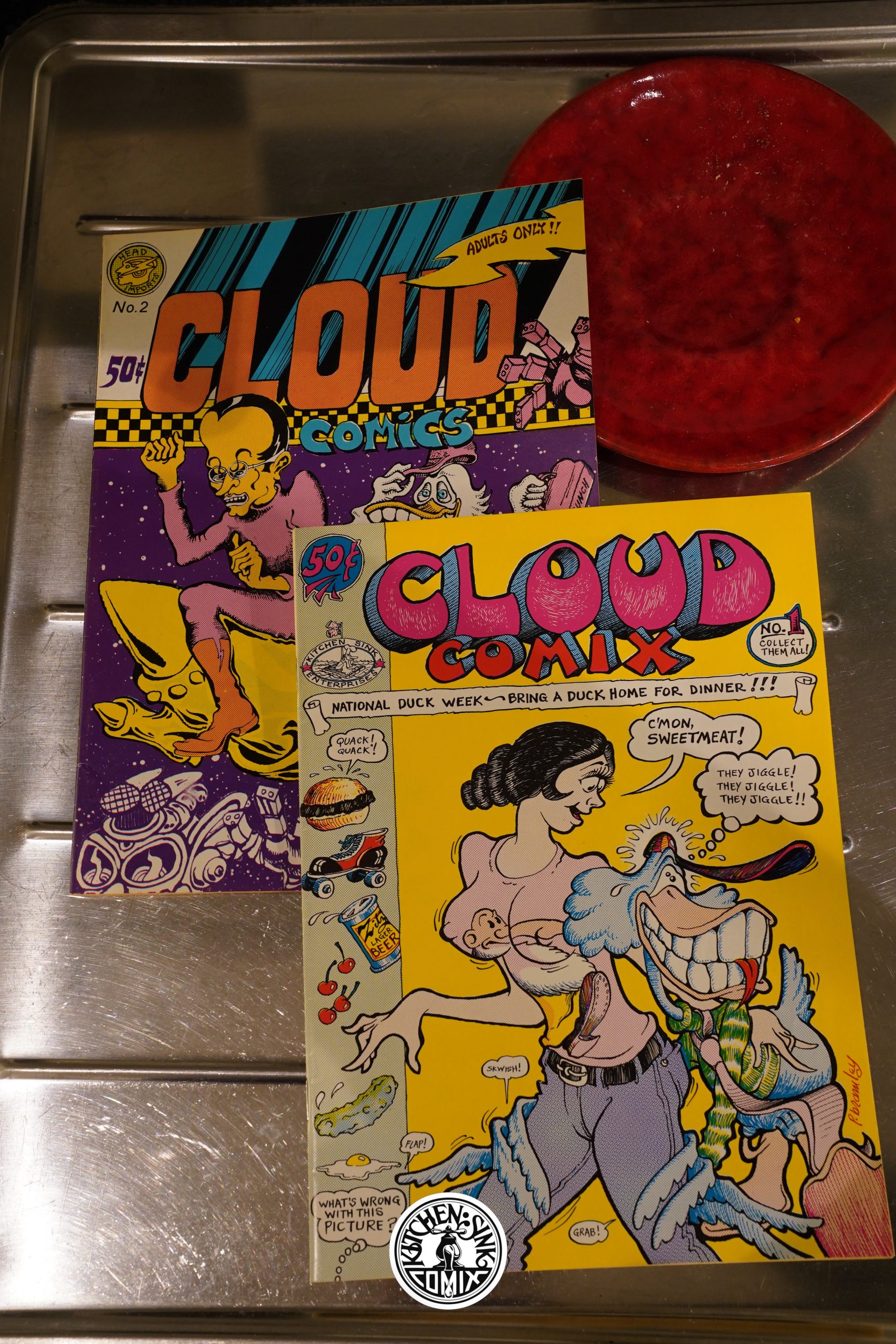

But that’s later! The first four issues of this book weren’t published by Kitchen Sink — the first KSP issue arrived in… 1972?, but here we’re back in 1968, and the book was kinda-sorta self-published (but distributed/really published by Print Mint).

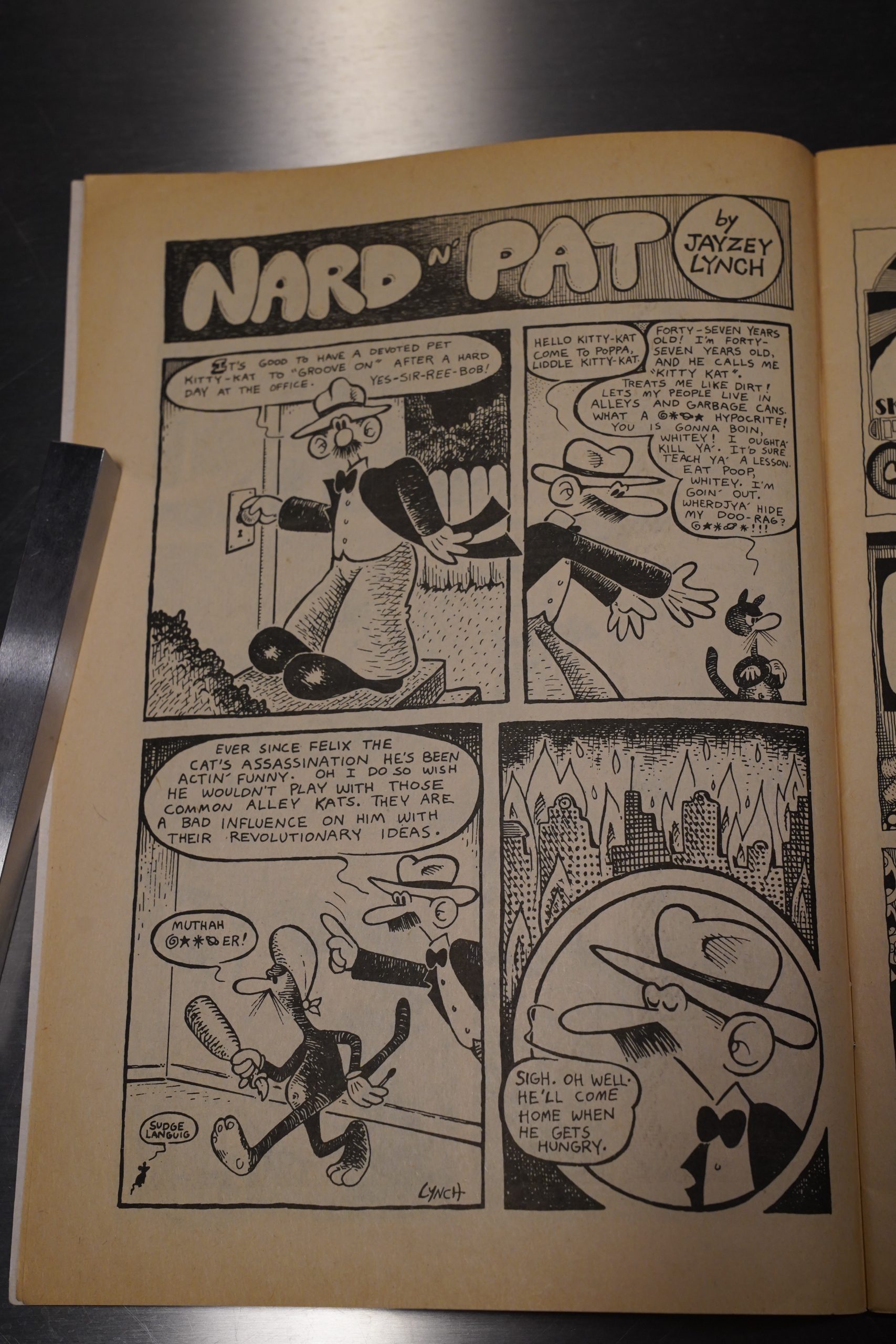

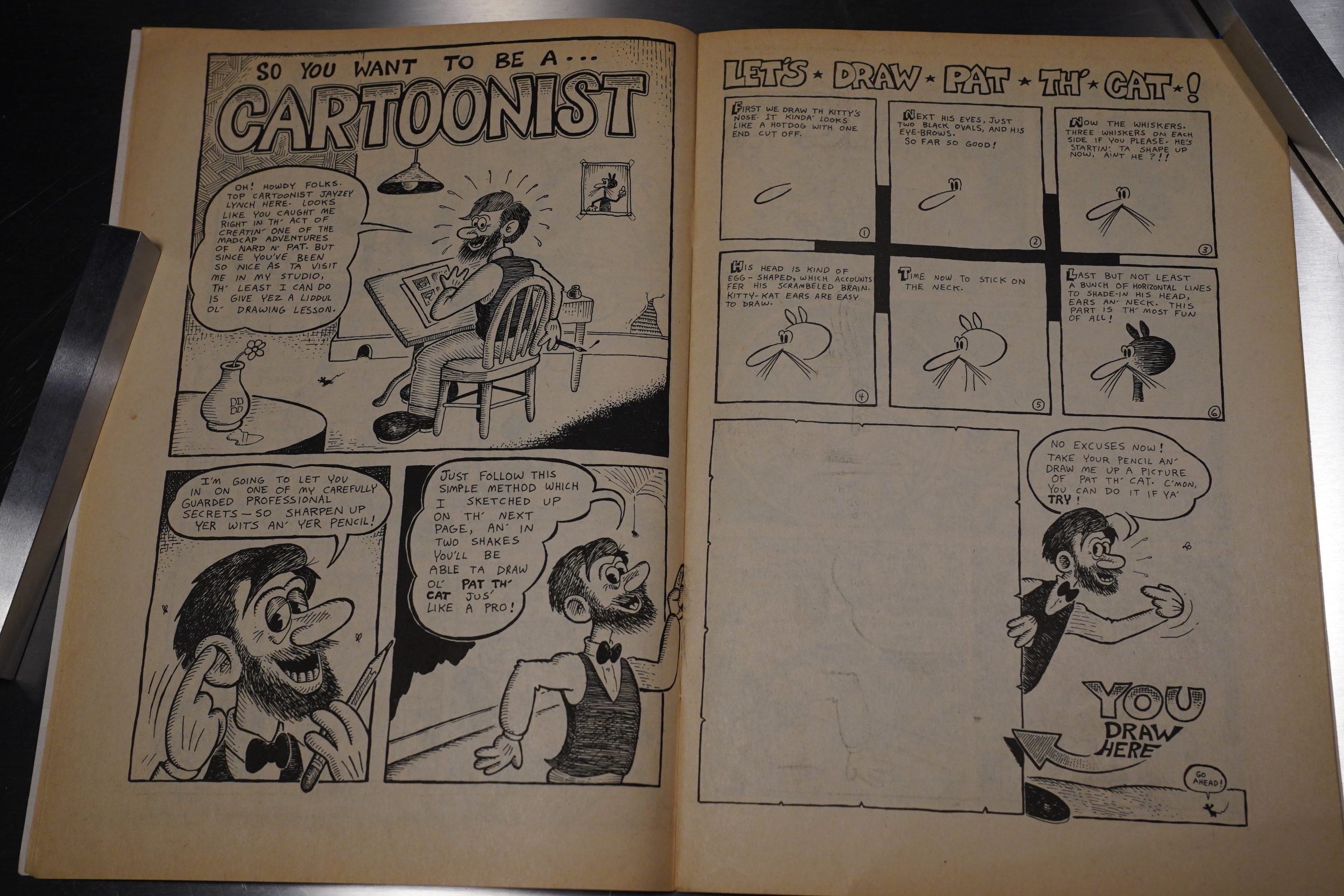

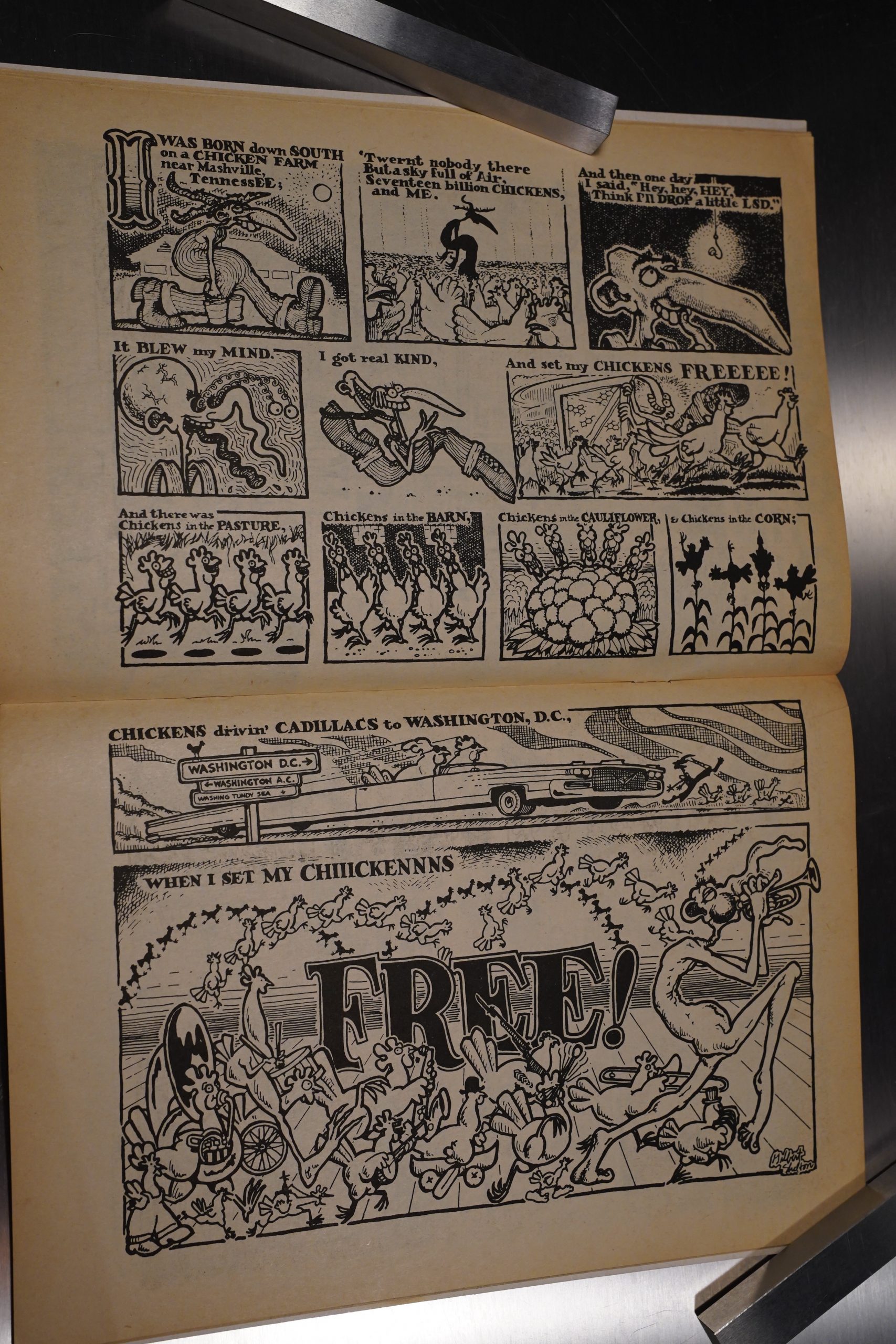

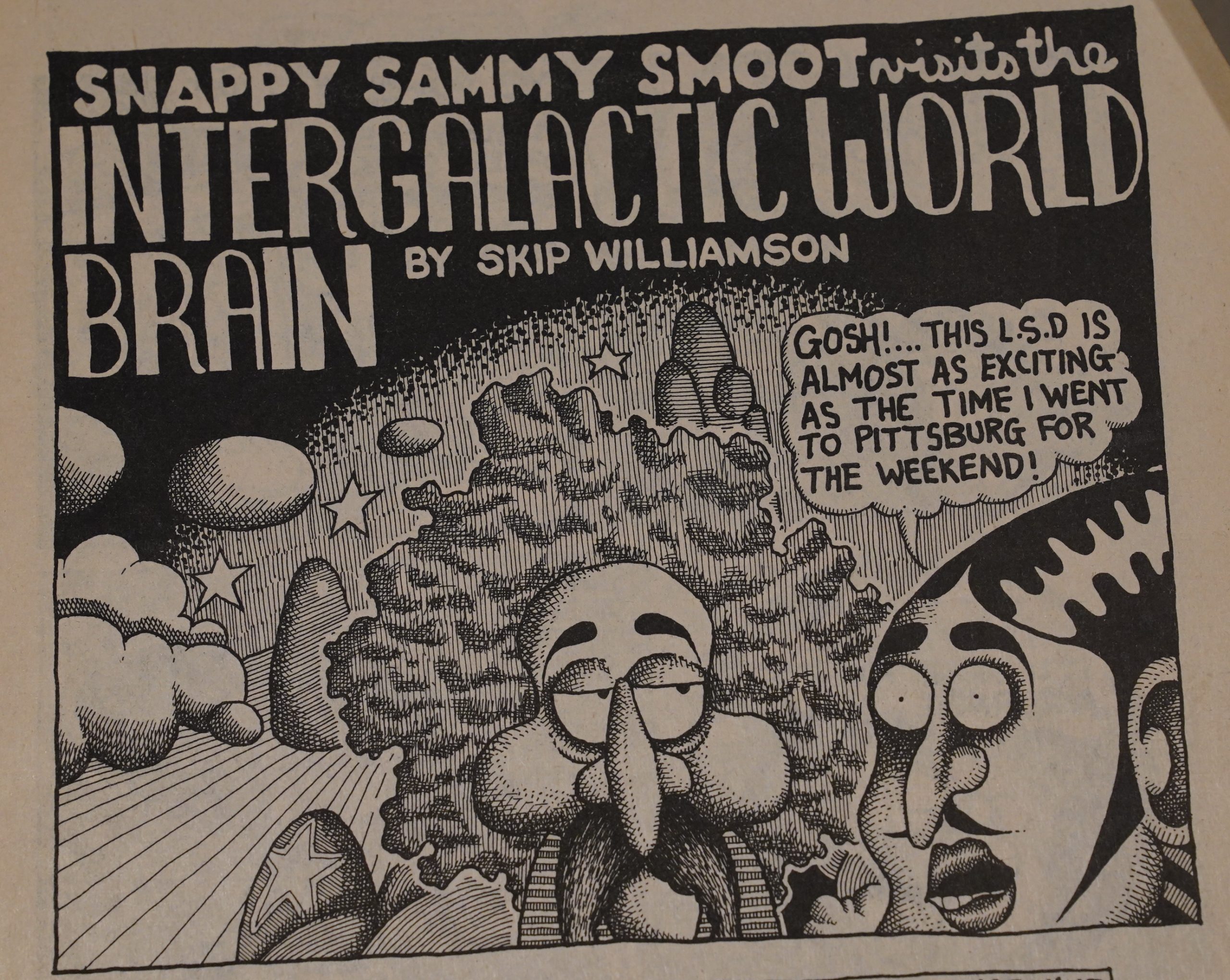

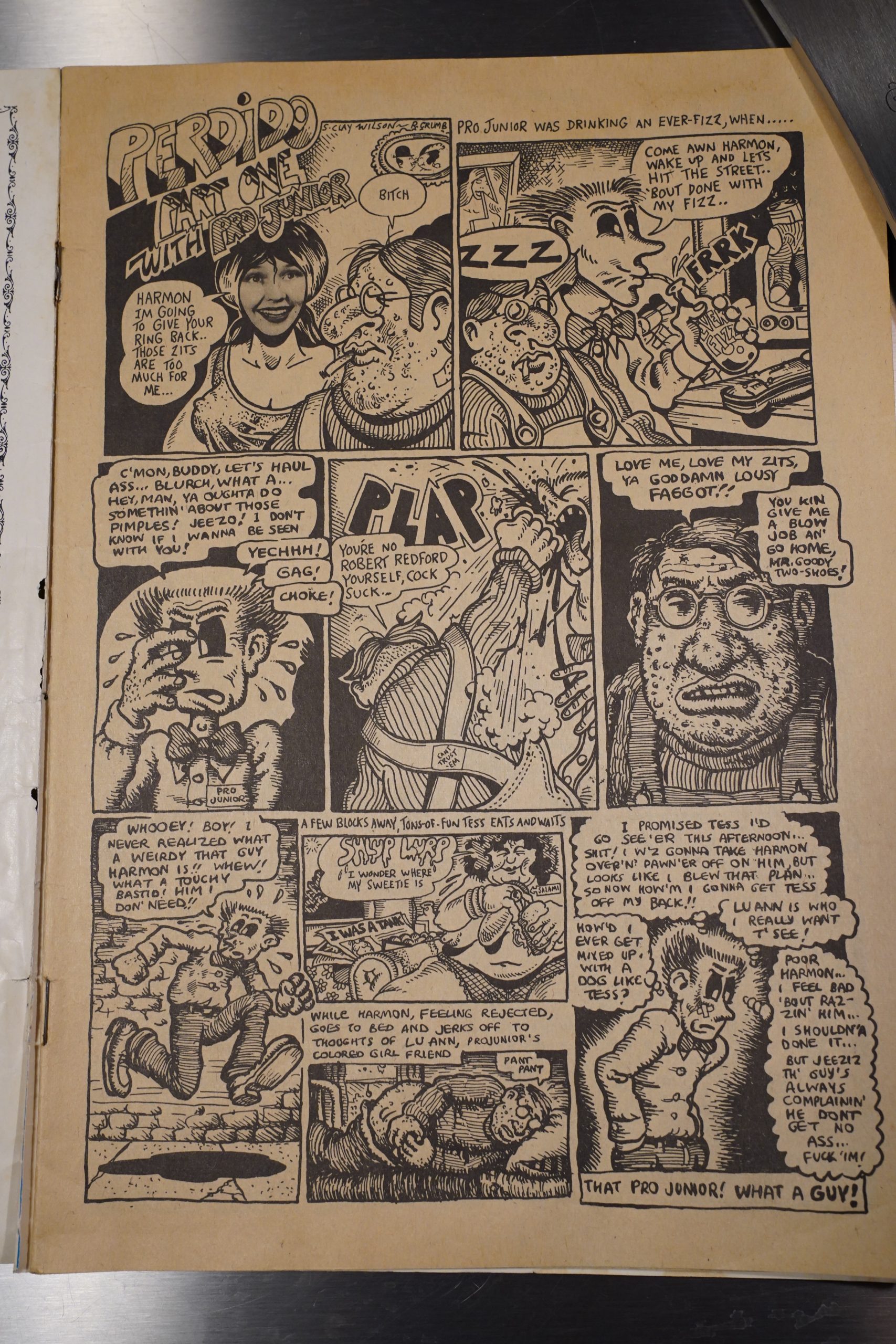

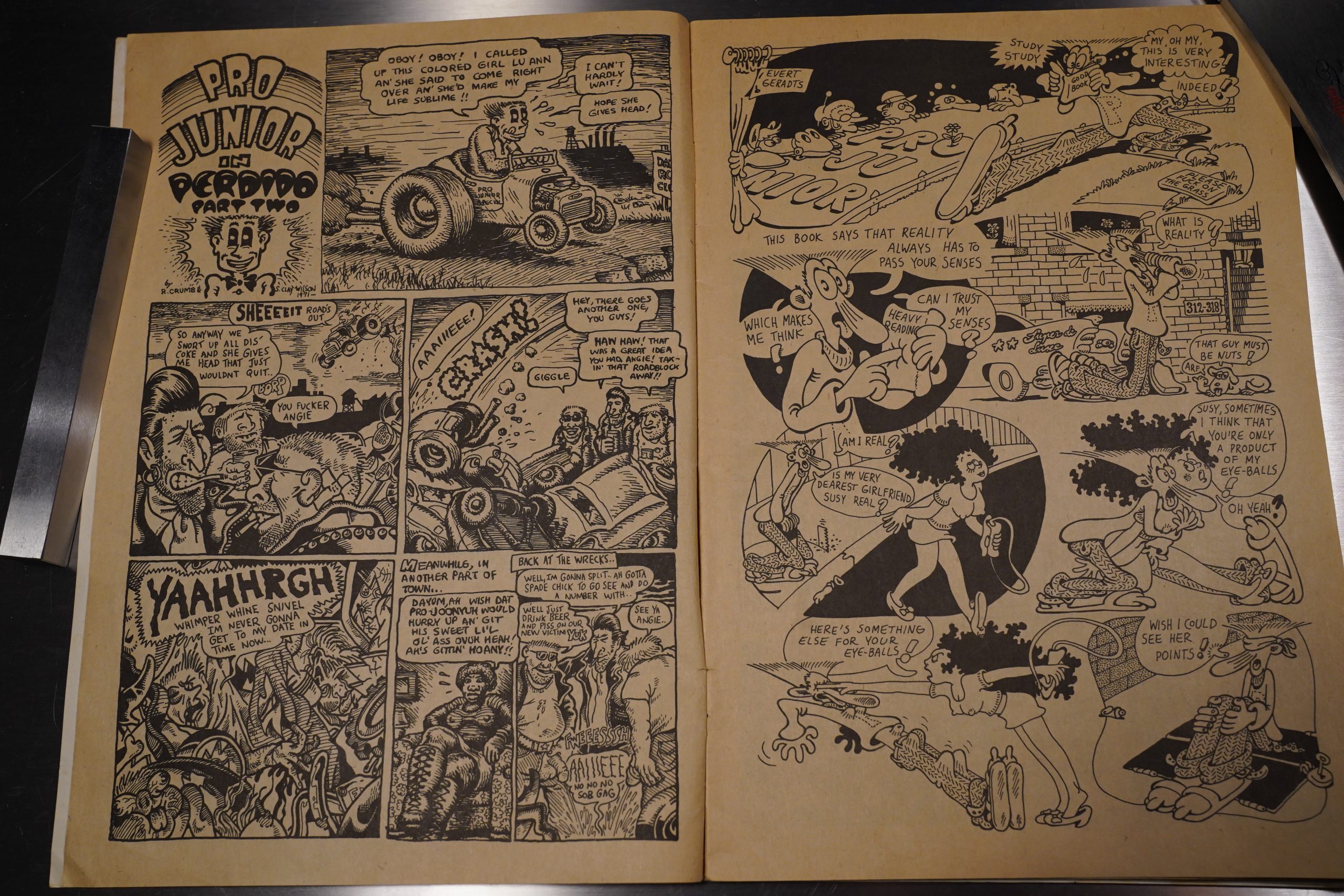

Jay Lynch and Skip Williamson are definitely the most prolific contributors to Bijou.

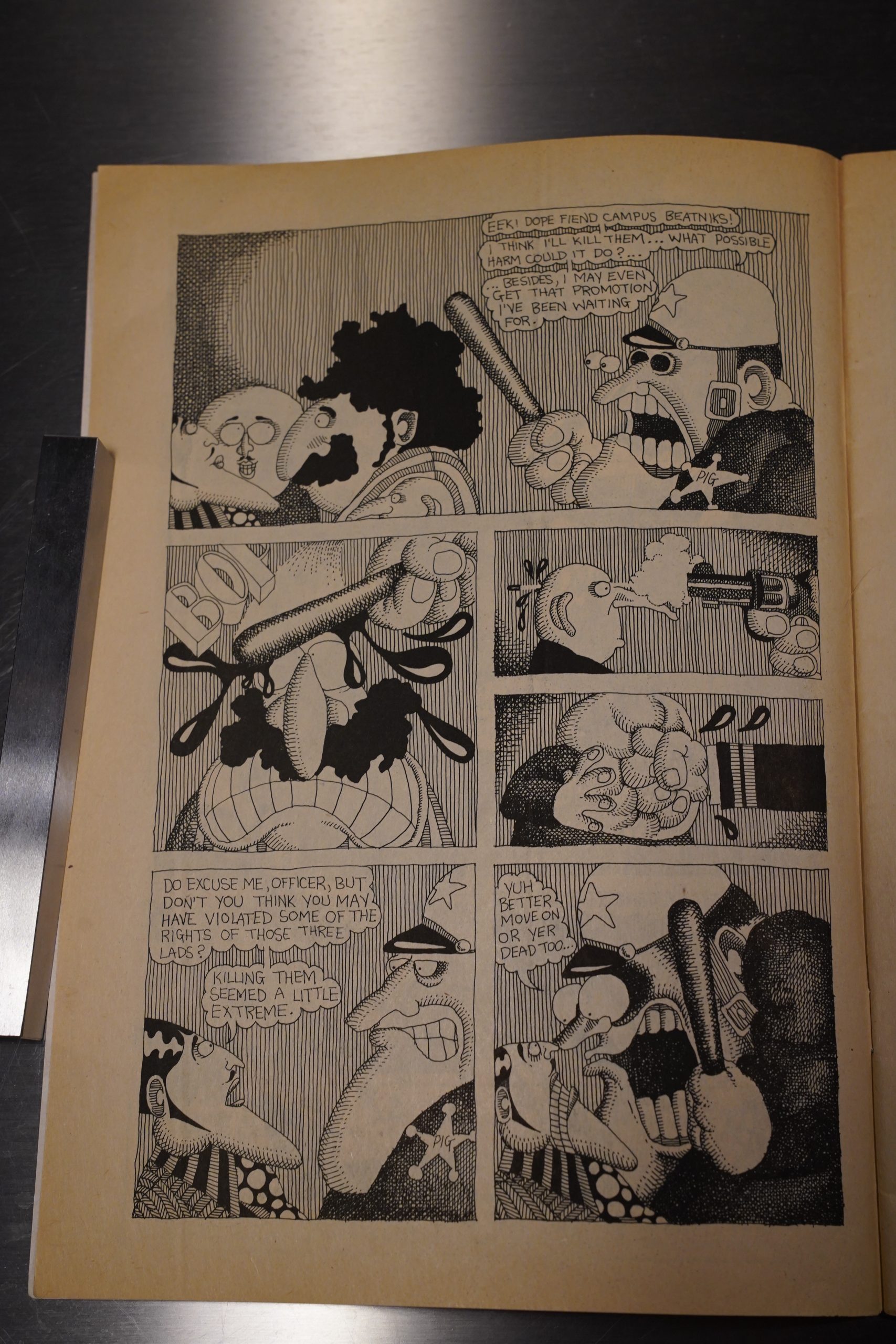

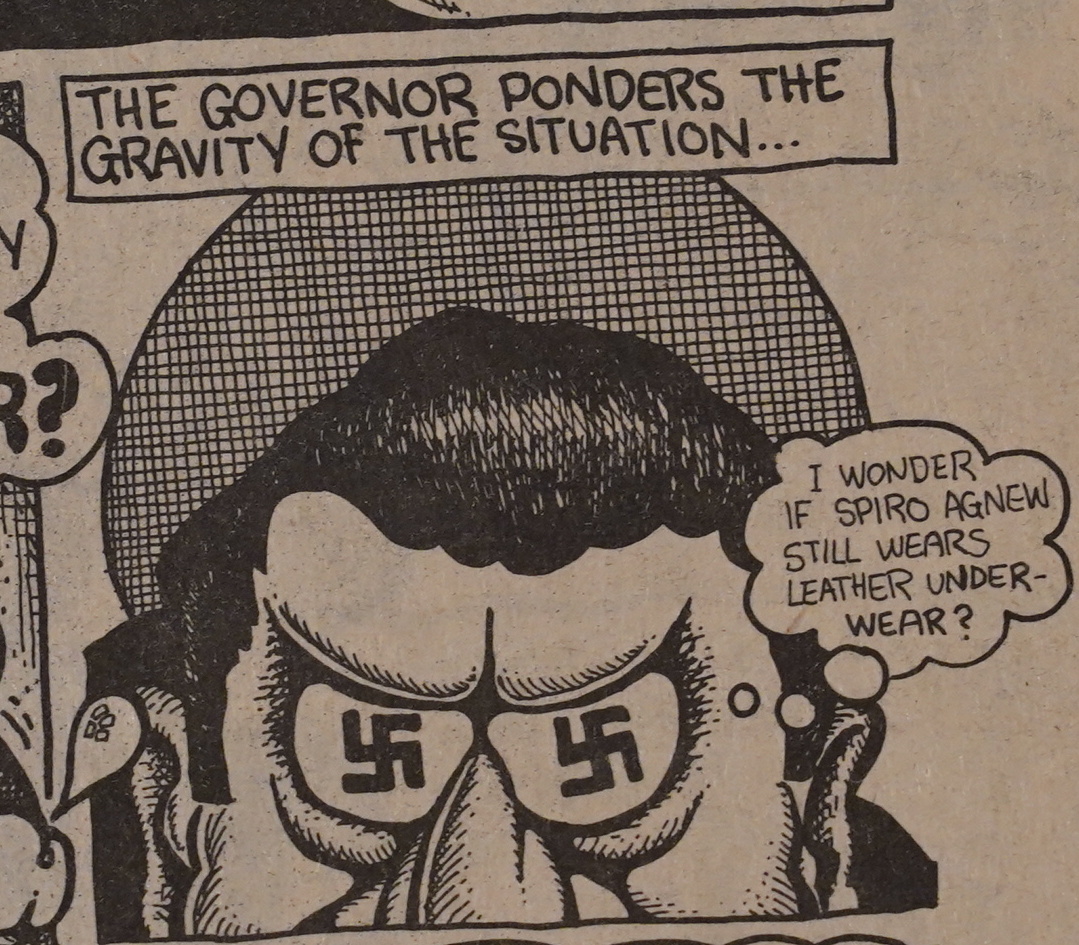

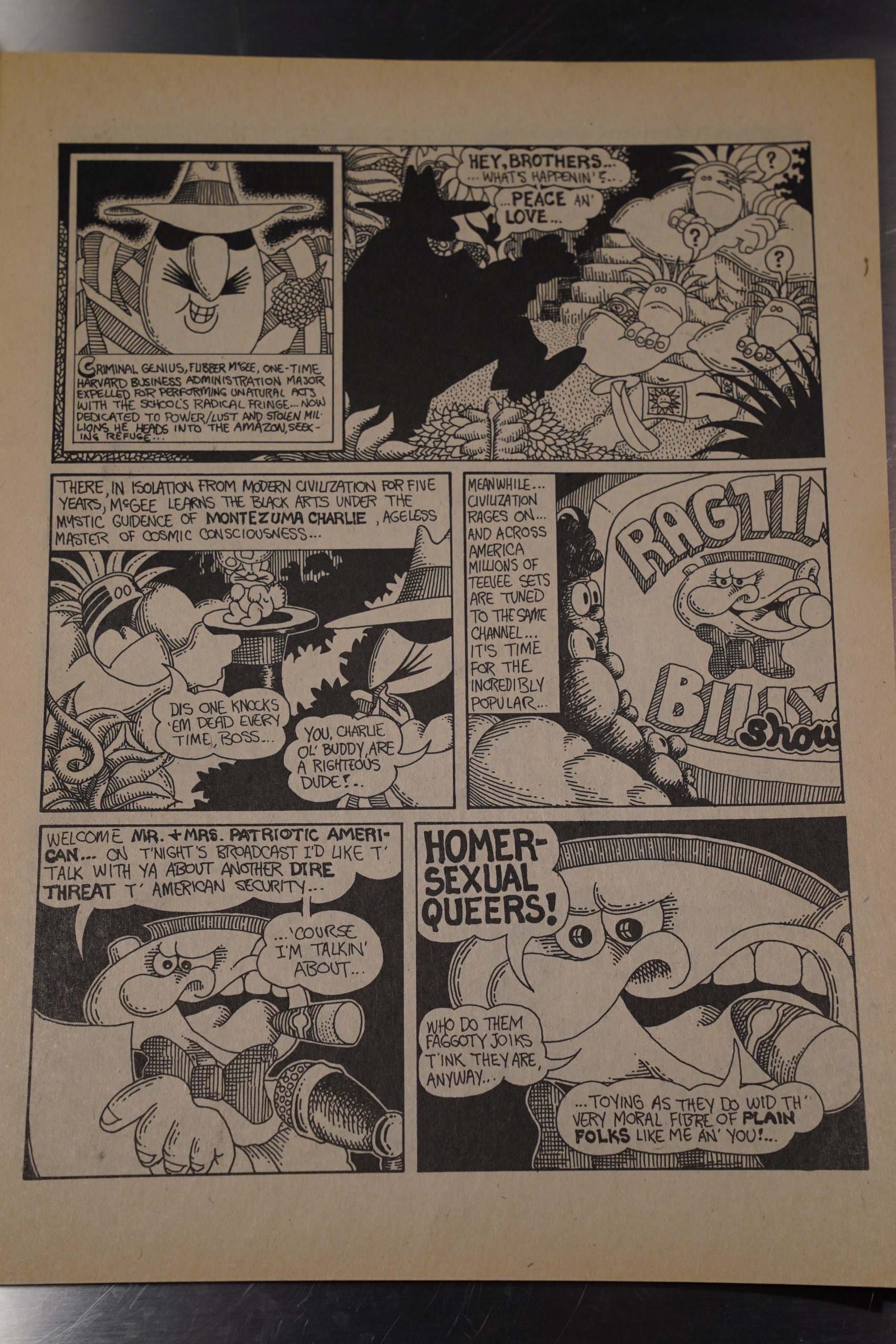

Williamson’s main schtick is that he’s making fun of both the hippies and the cops, I guess.

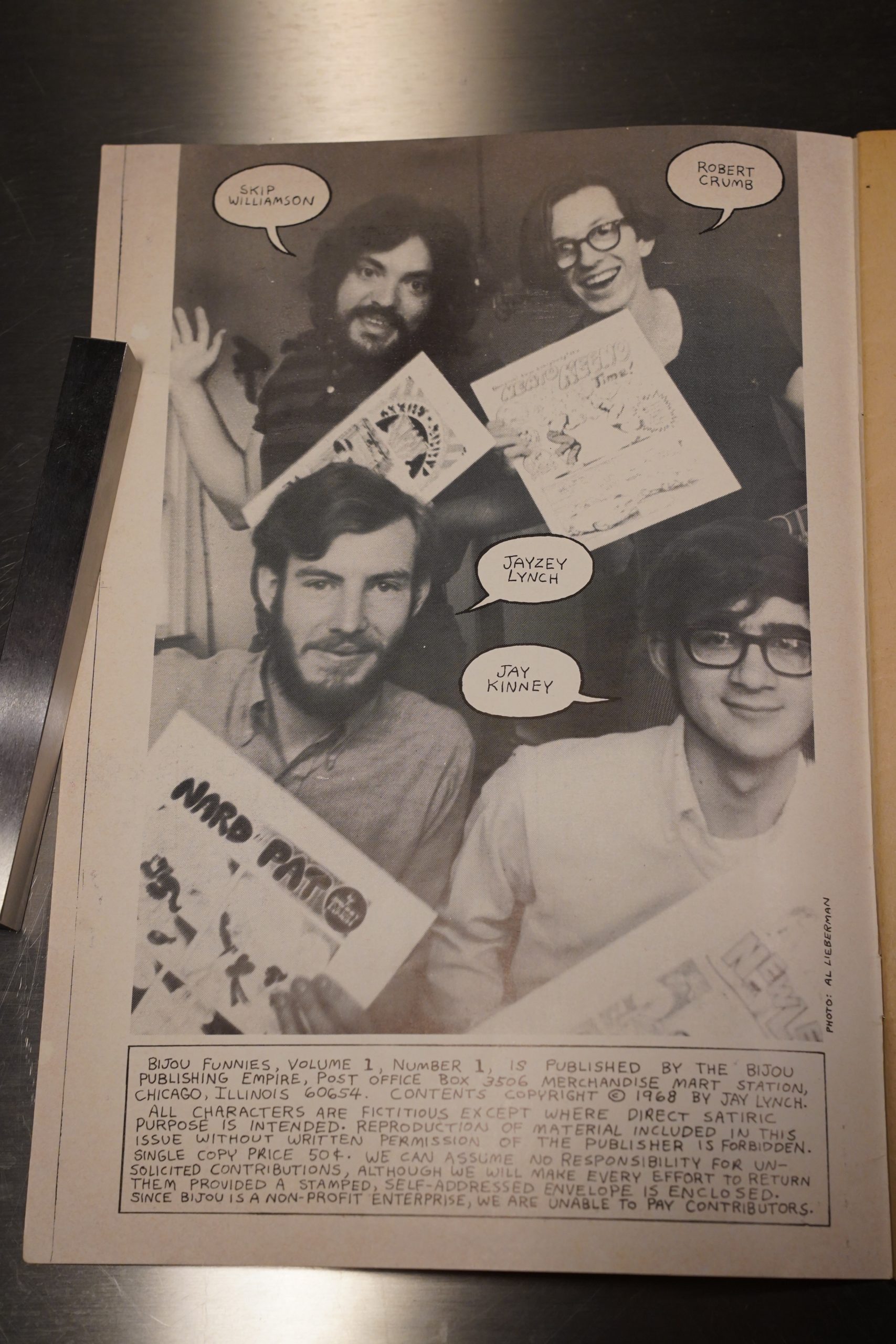

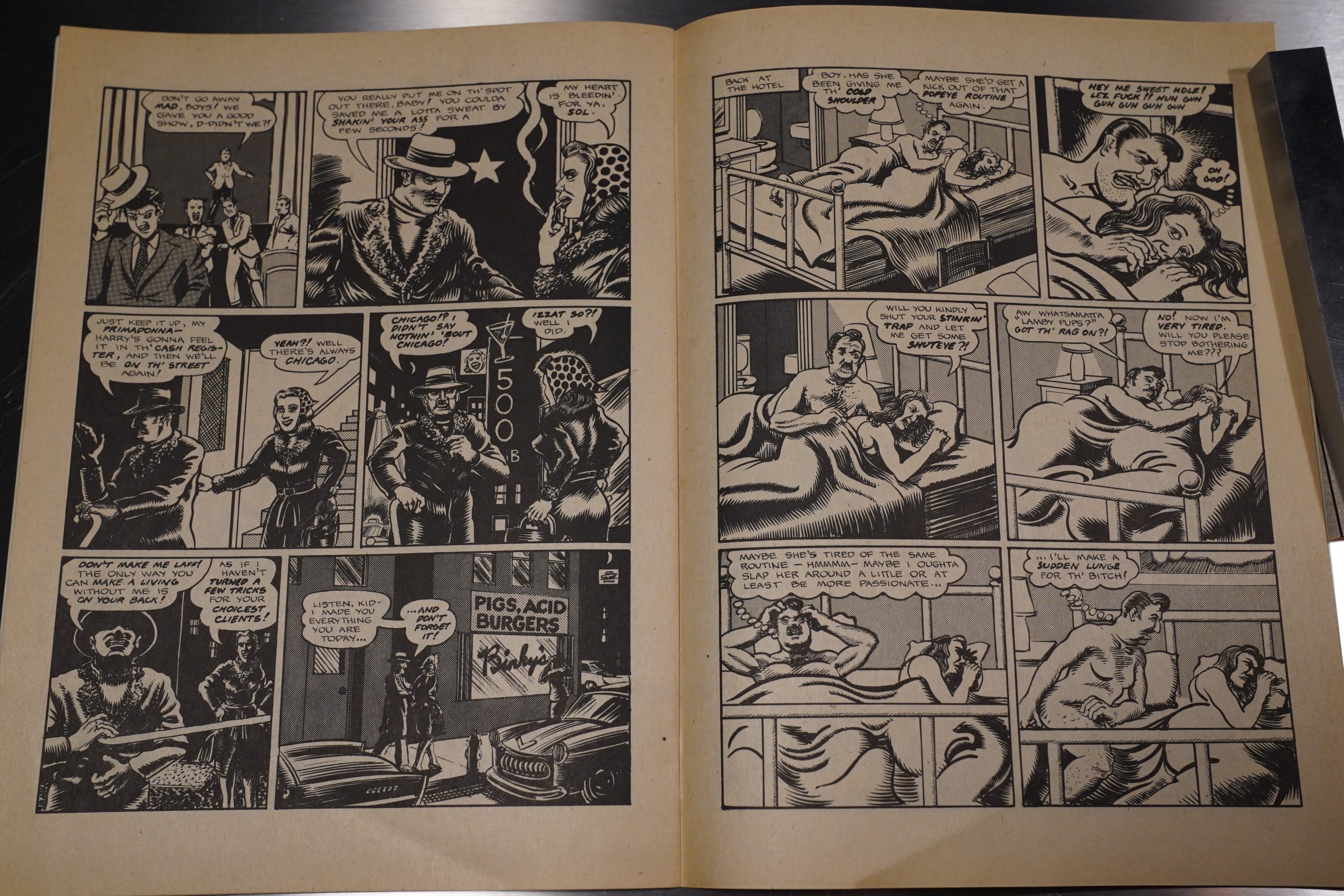

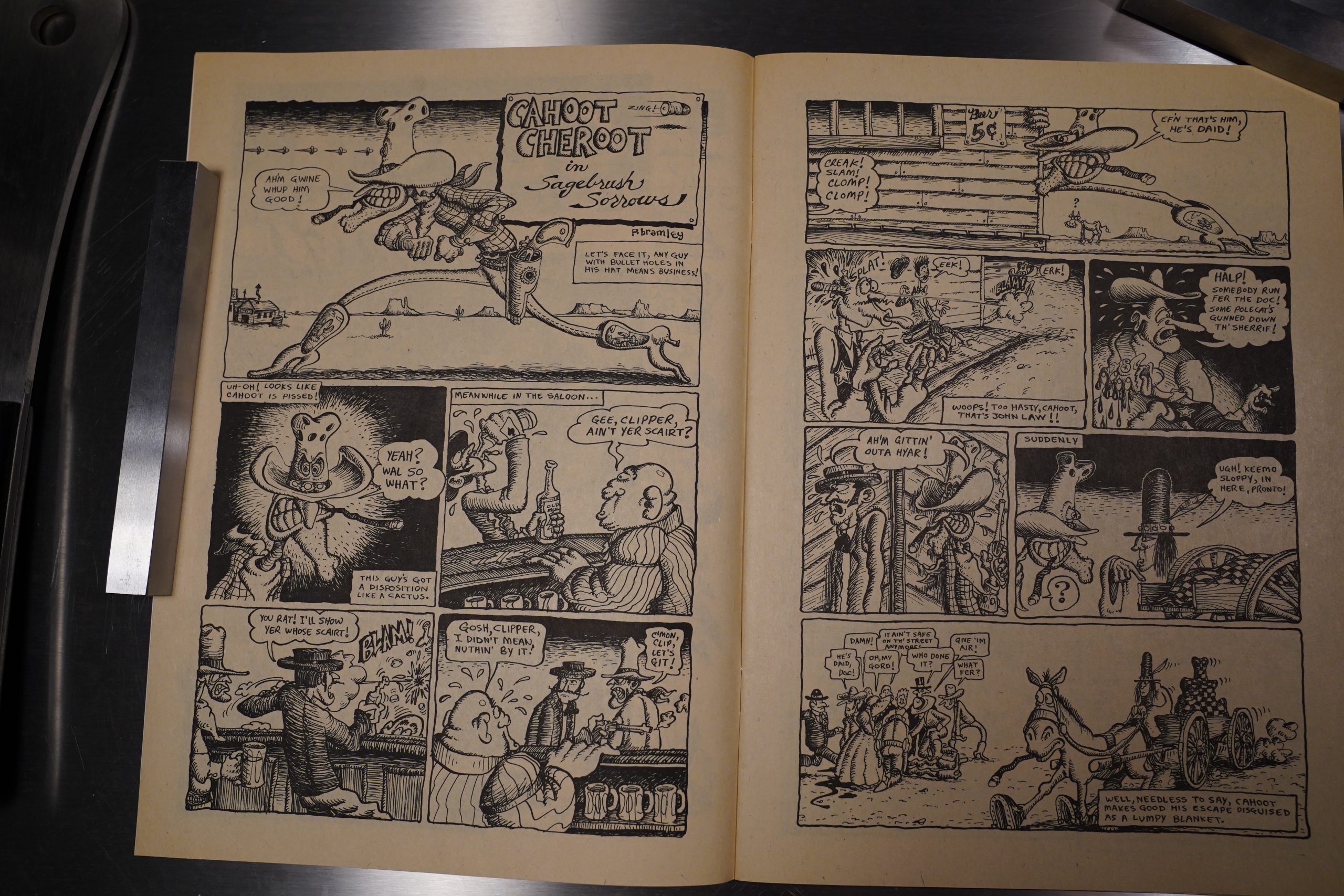

Jay Lynch’s earliest stuff is a lot less dense than it would become just a bit later. I guess what you could say ties all of the main contributors to Bijou together is an interest in cartooning as craft: The artwork’s polished and kinda influenced by old animation (Lynch and Crumb) or pop art design (Williamson)…

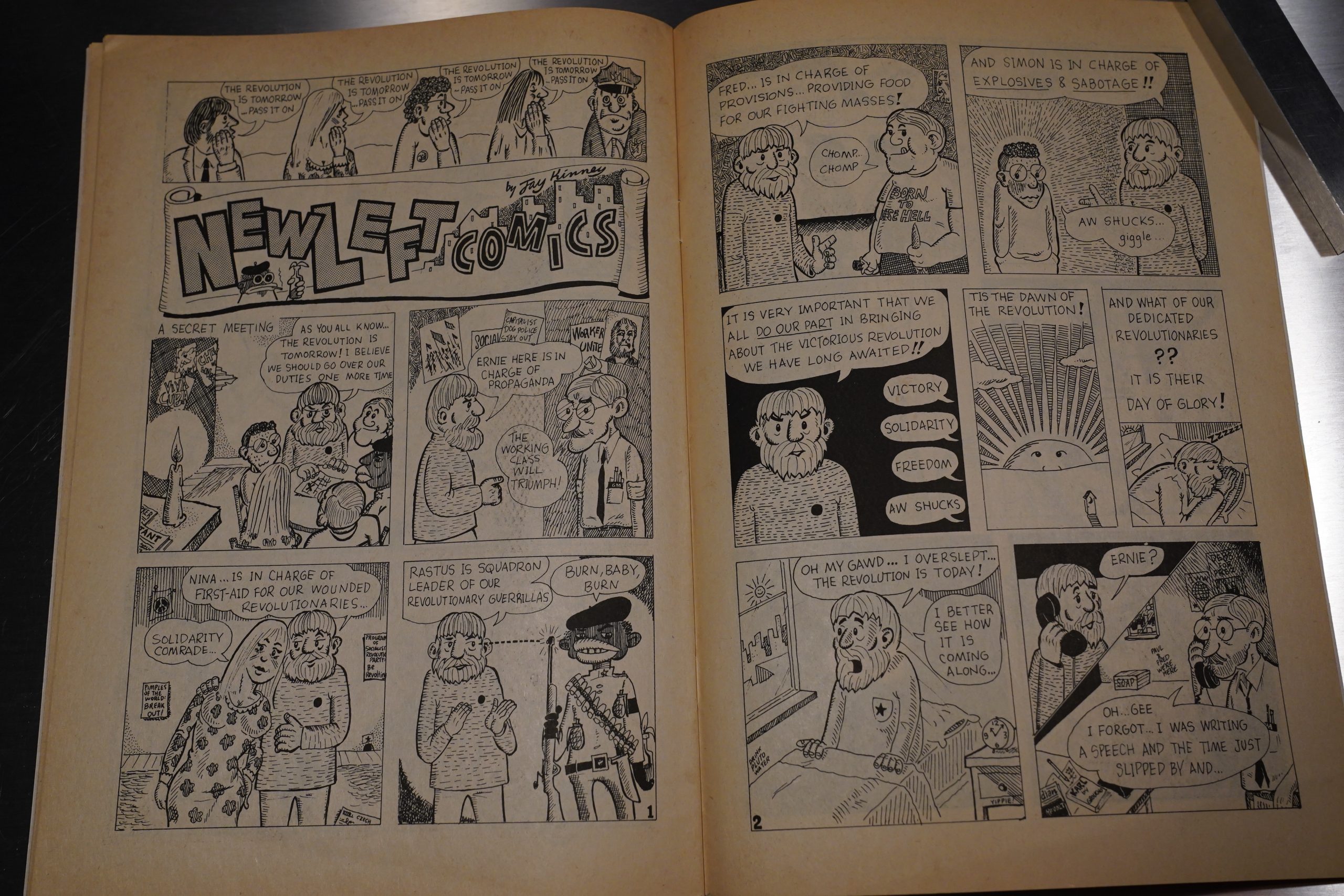

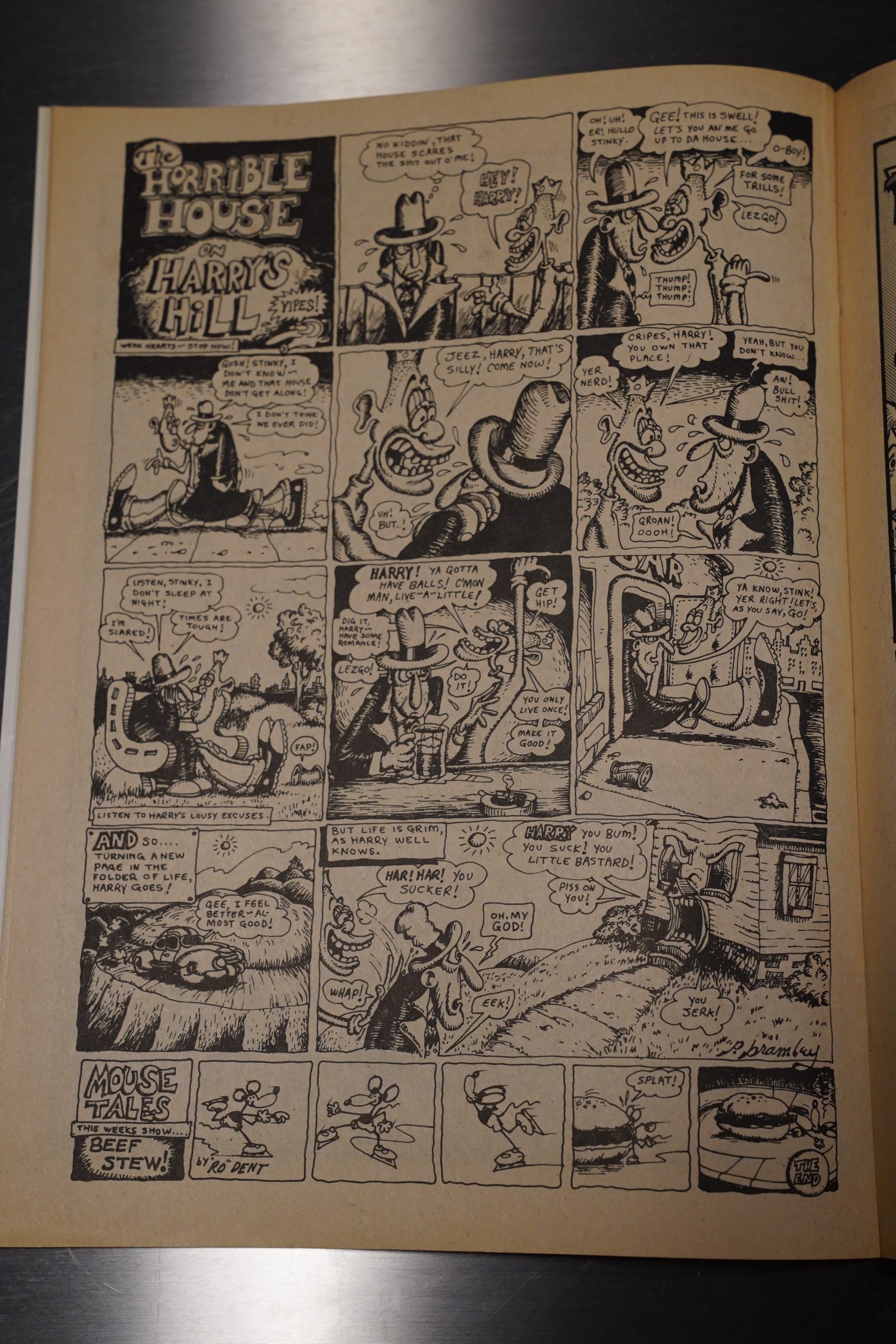

The first couple of issues are all over the place. Most of the bits are amusing, but it’s all so random that it feels a bit like a fanzine? I.e., not edited.

And this was during Crumb’s more unhinged period.

Gilbert Sheldon’s doing a rare non-Freak Brothers thing… or perhaps he hadn’t come up with them yet?

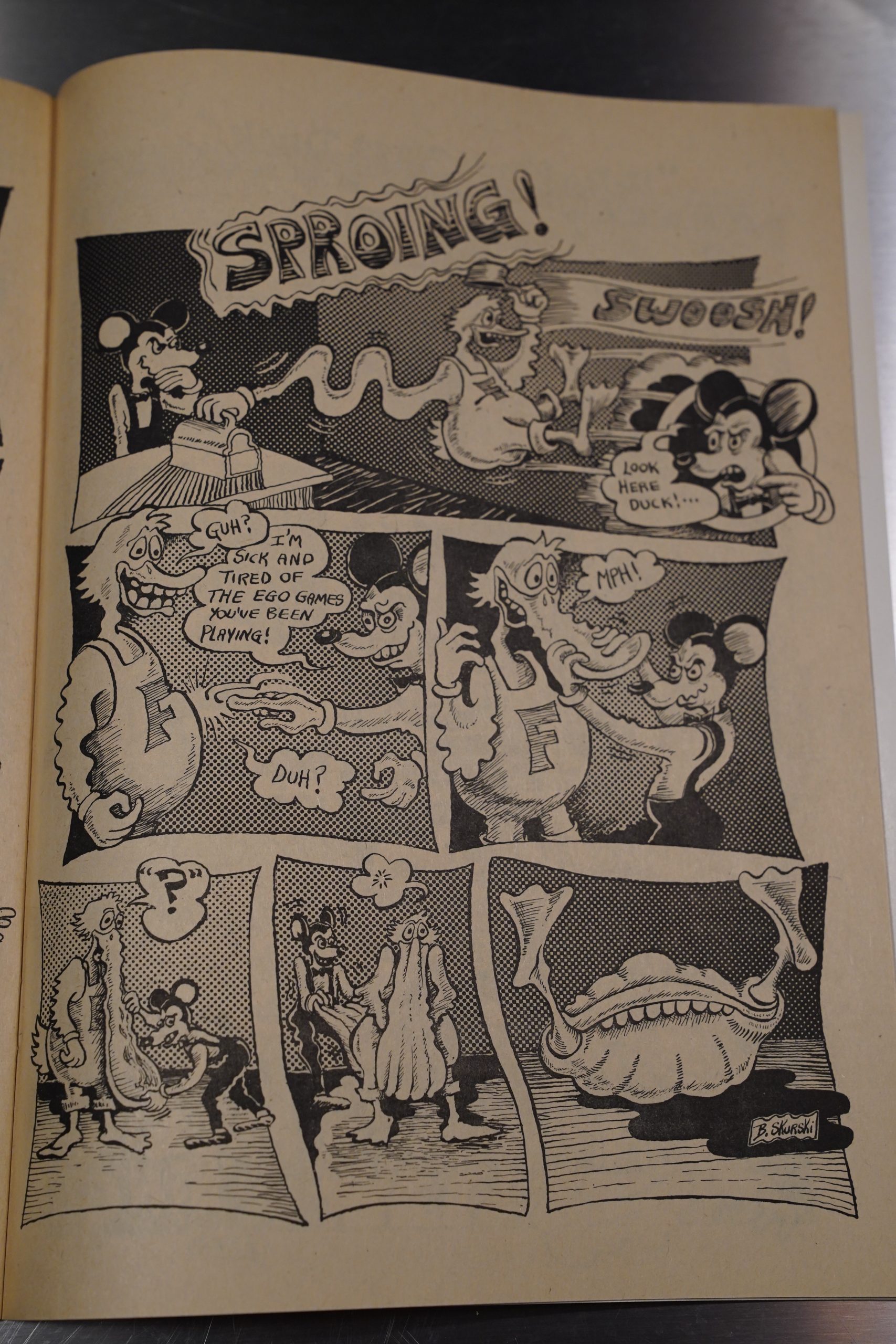

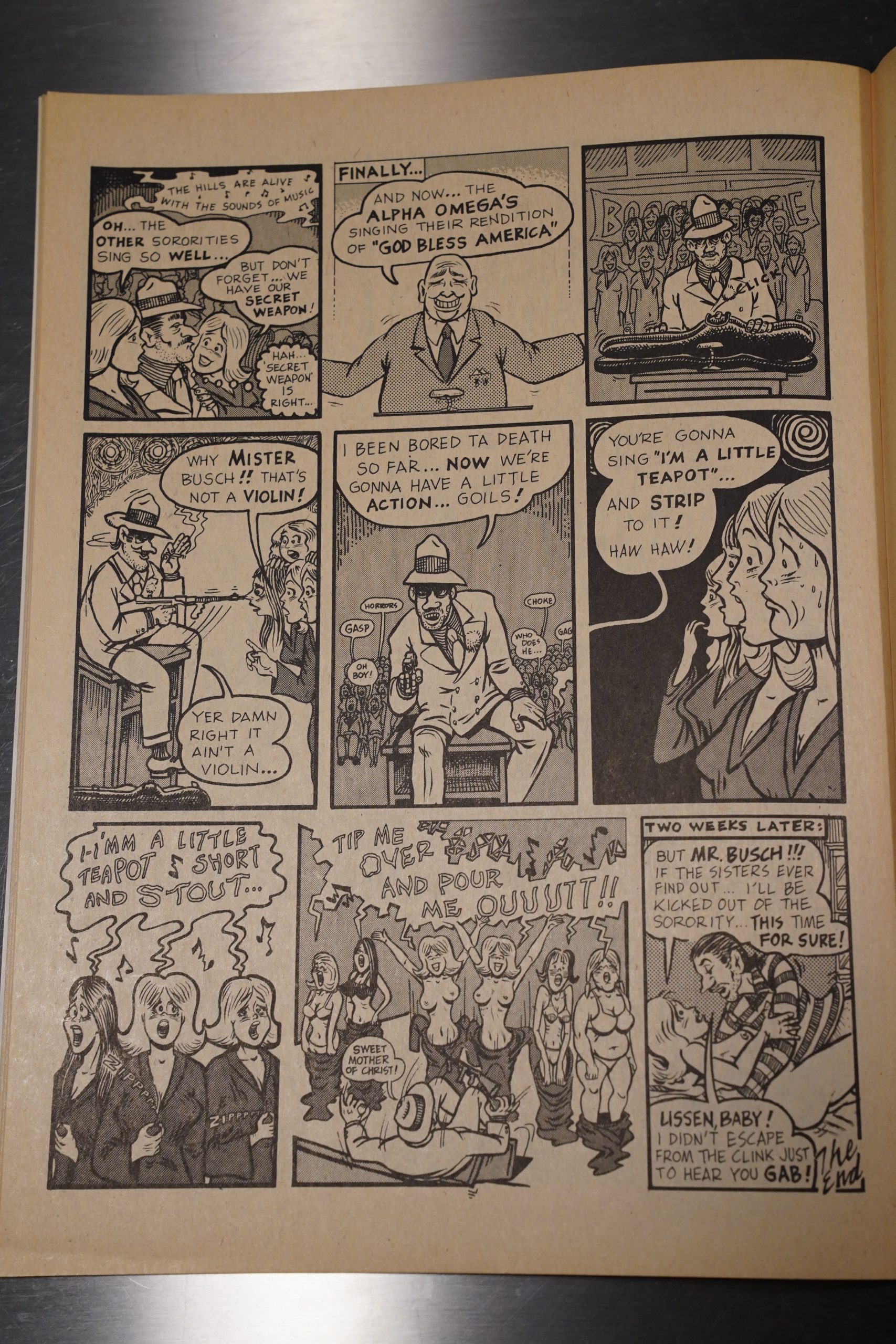

Jay Kinney’s contributions stick out like a sore thumb. It’s charmless and amateurish.

Wow! That’s exciting!

The format of the book is quite unusual. It’s smaller than standard US comics size — slightly narrower and more than slightly shorter. It’s a very cute format.

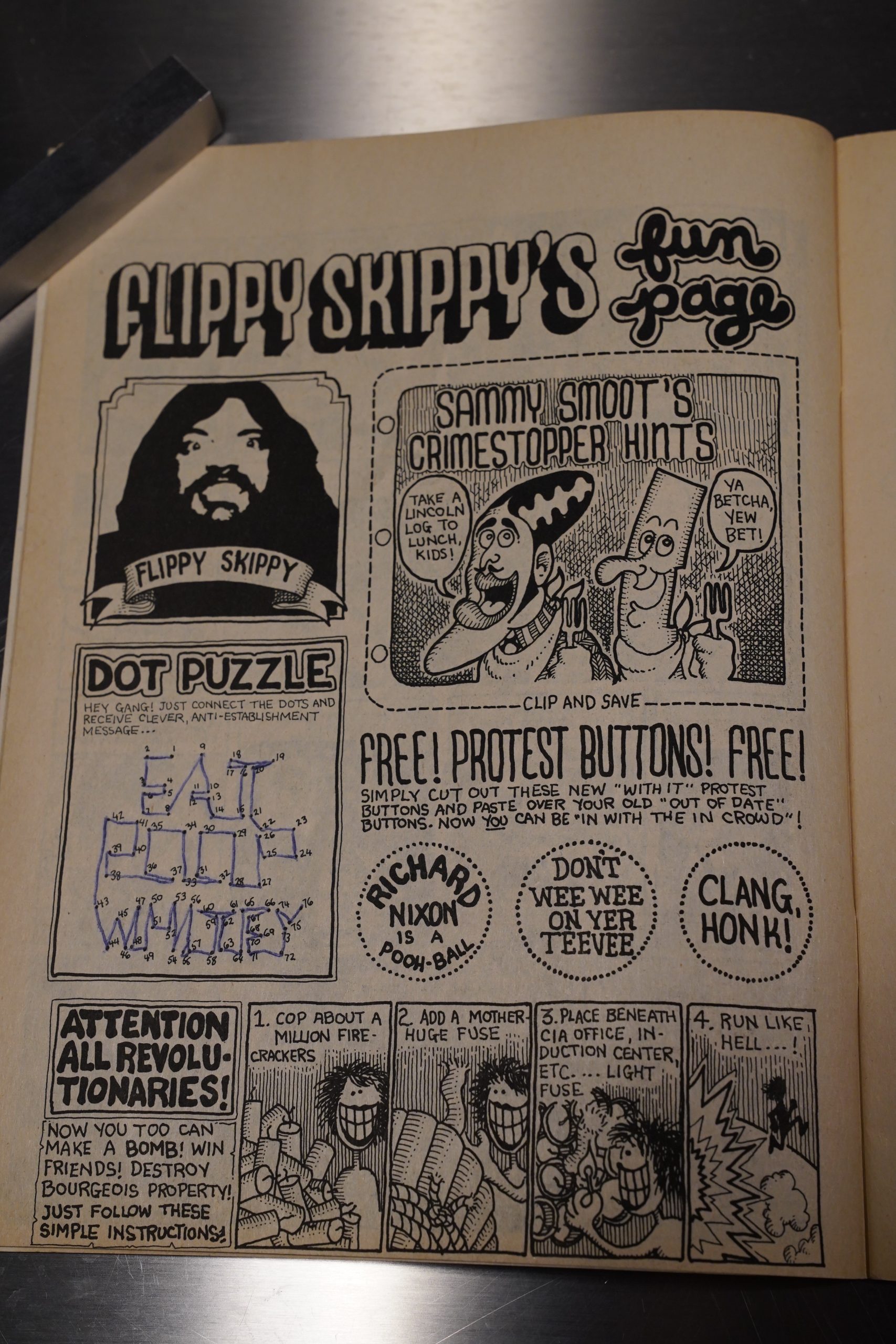

(Heh. Somebody’s filled out that puzzle… “Eat Poop Whitey”?)

The printing on the second issue is a bit off — that is, it seems to be mis-cut or mis-printed; the printed area is too far down.

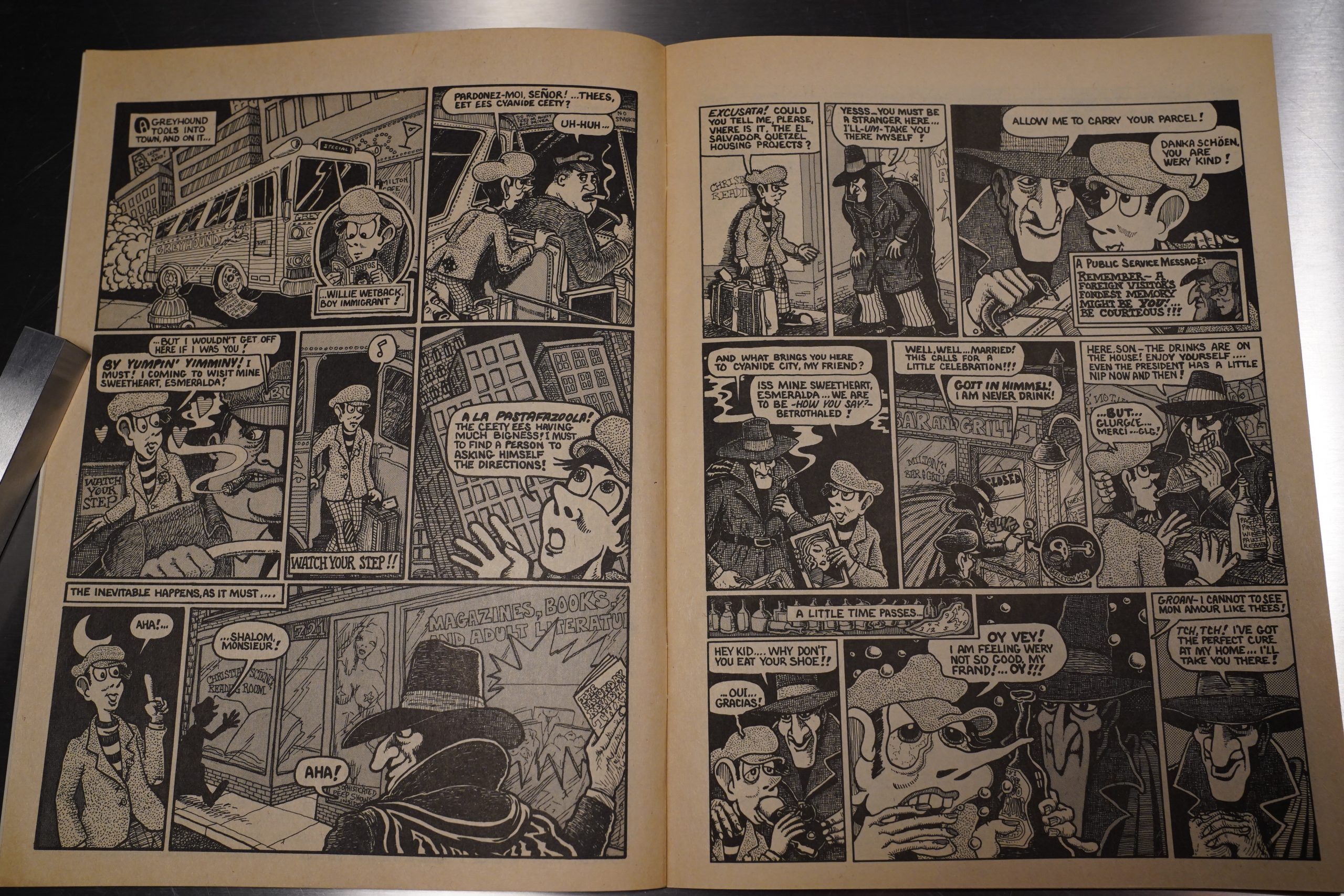

As I was saying about the format — these are very small pages, but they cram a lot of stuff into them, making some of the pages very dense indeed. But that kinda also gives these books a certain charm? They don’t feel like precious objects, but seem special anyway…

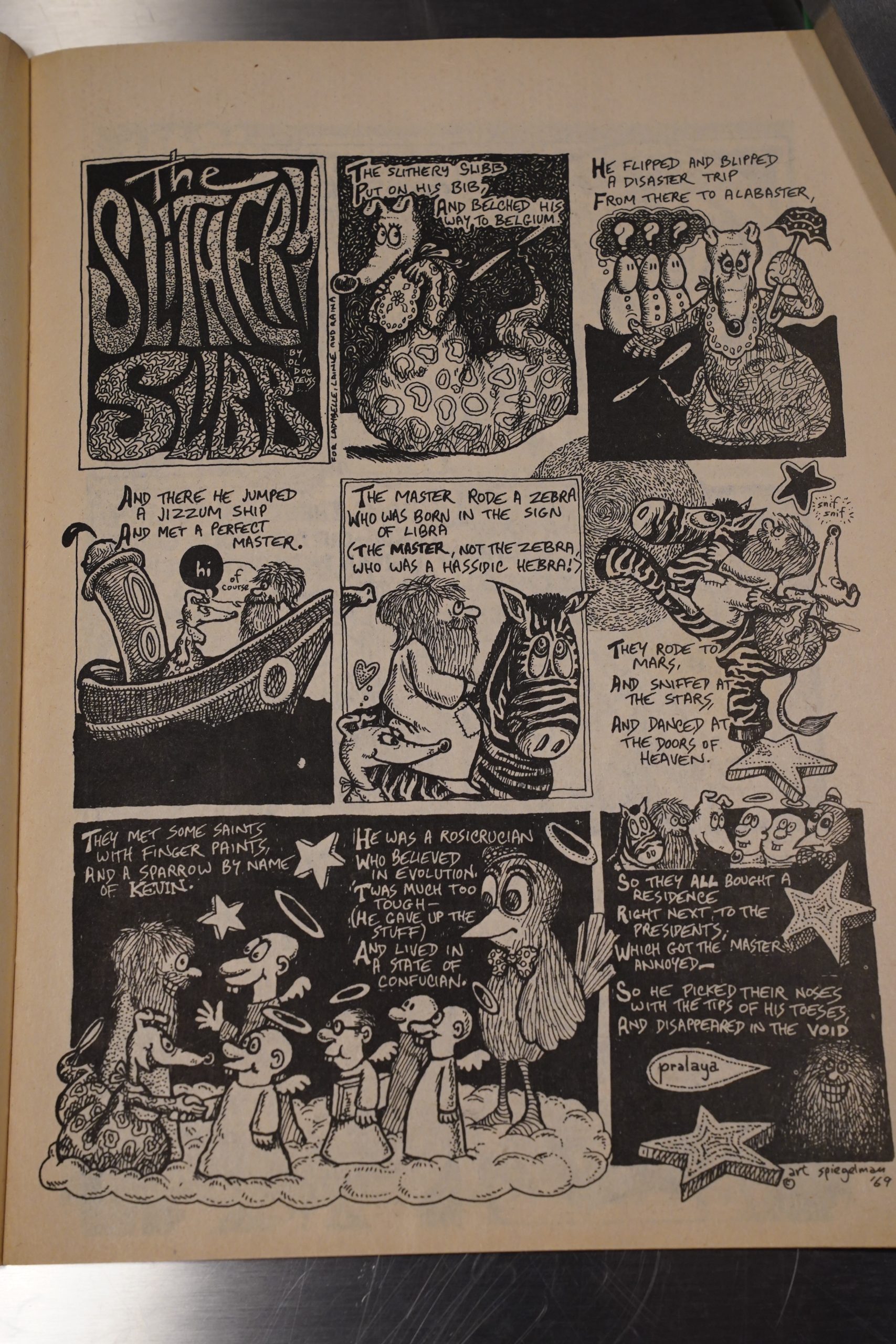

What the… That’s Art Spiegelman!? I wouldn’t have guessed without the signature there. I had no idea that he was dabbling in this style for a while.

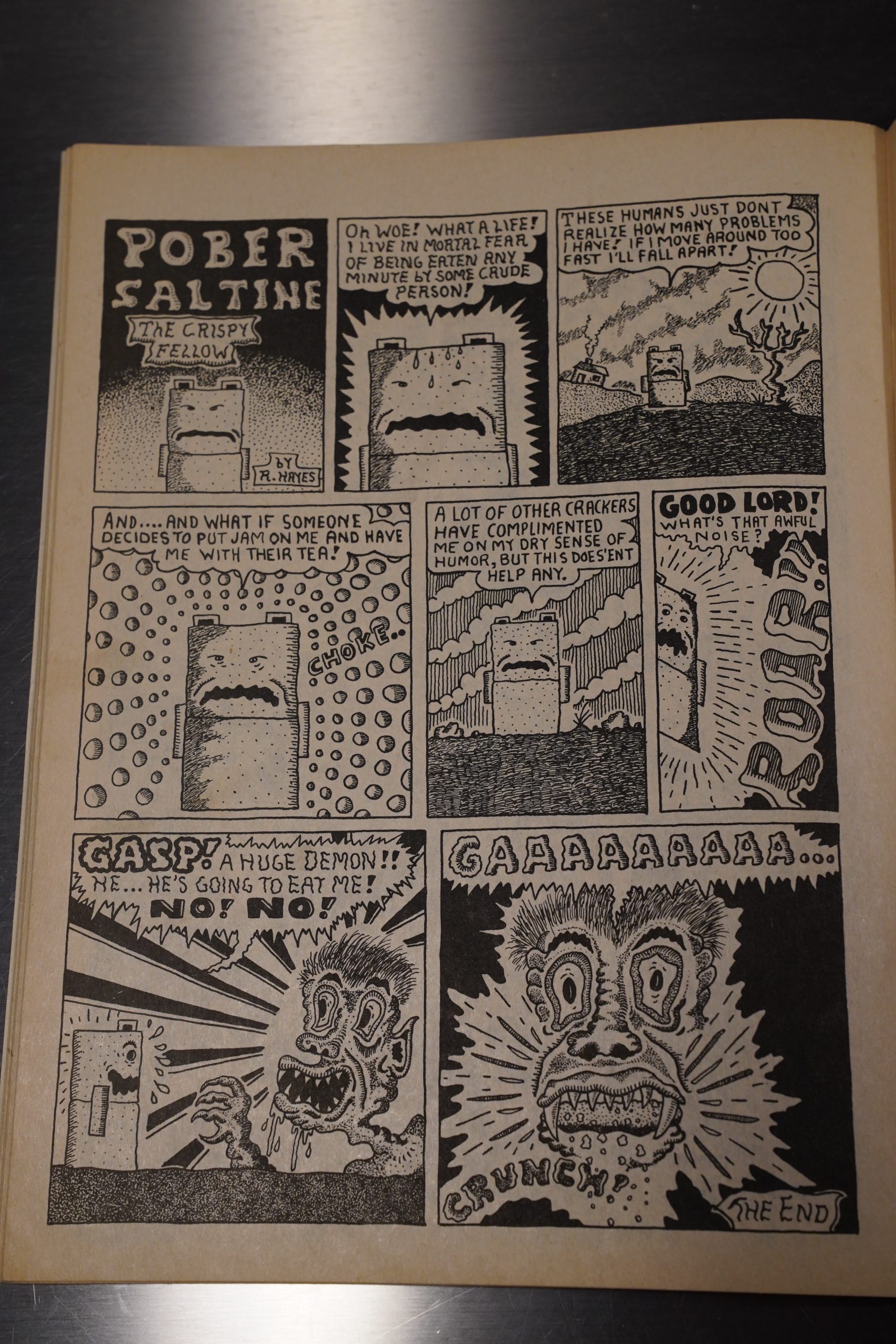

What the… Sudden Rory Hayes page! It seems totally out of place here, but still so right…

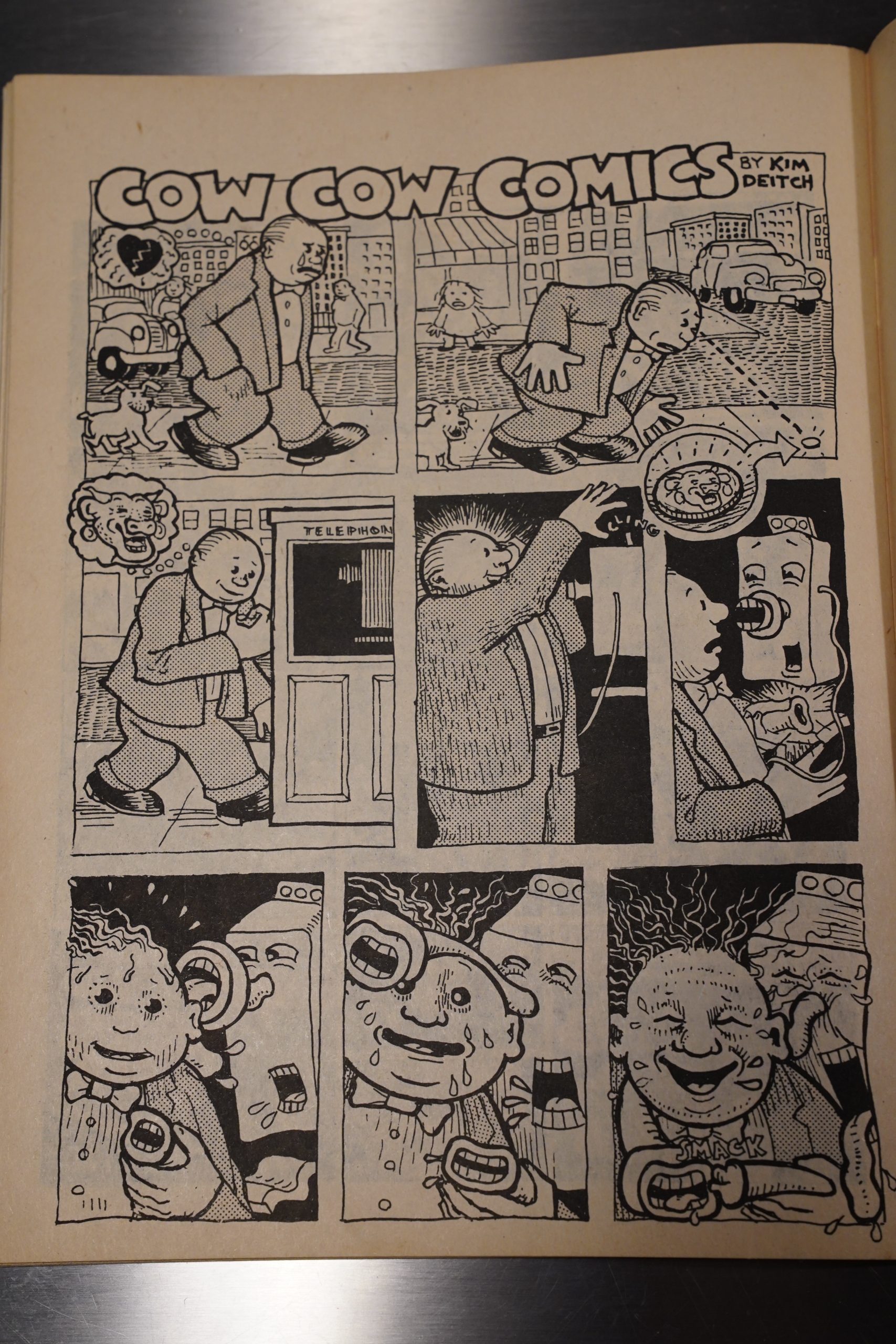

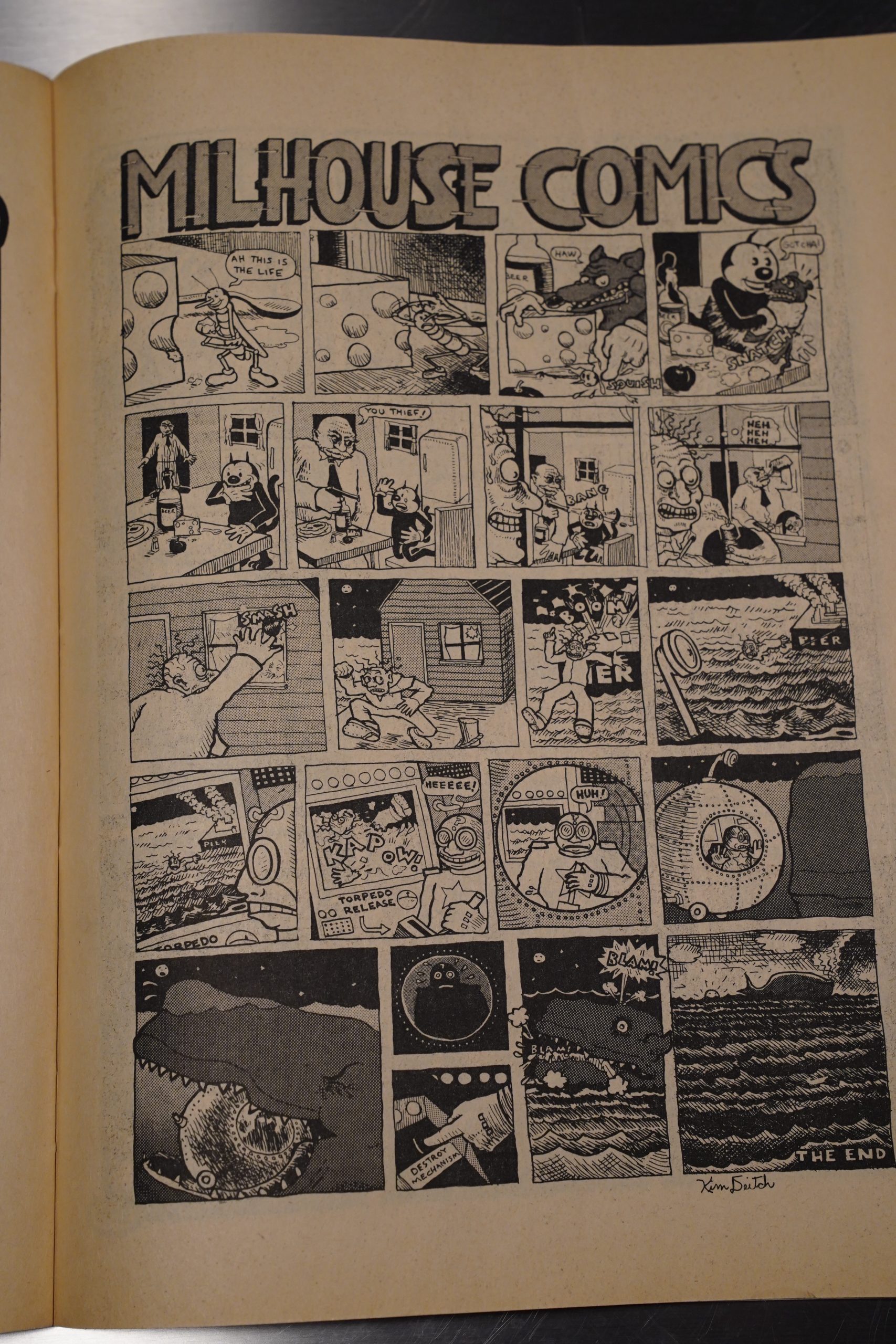

Wow. It’s so much fun seeing these early pieces by people who became well known later. Here’s Kim Deitch, looking nothing like he usually does. And so cosmic.

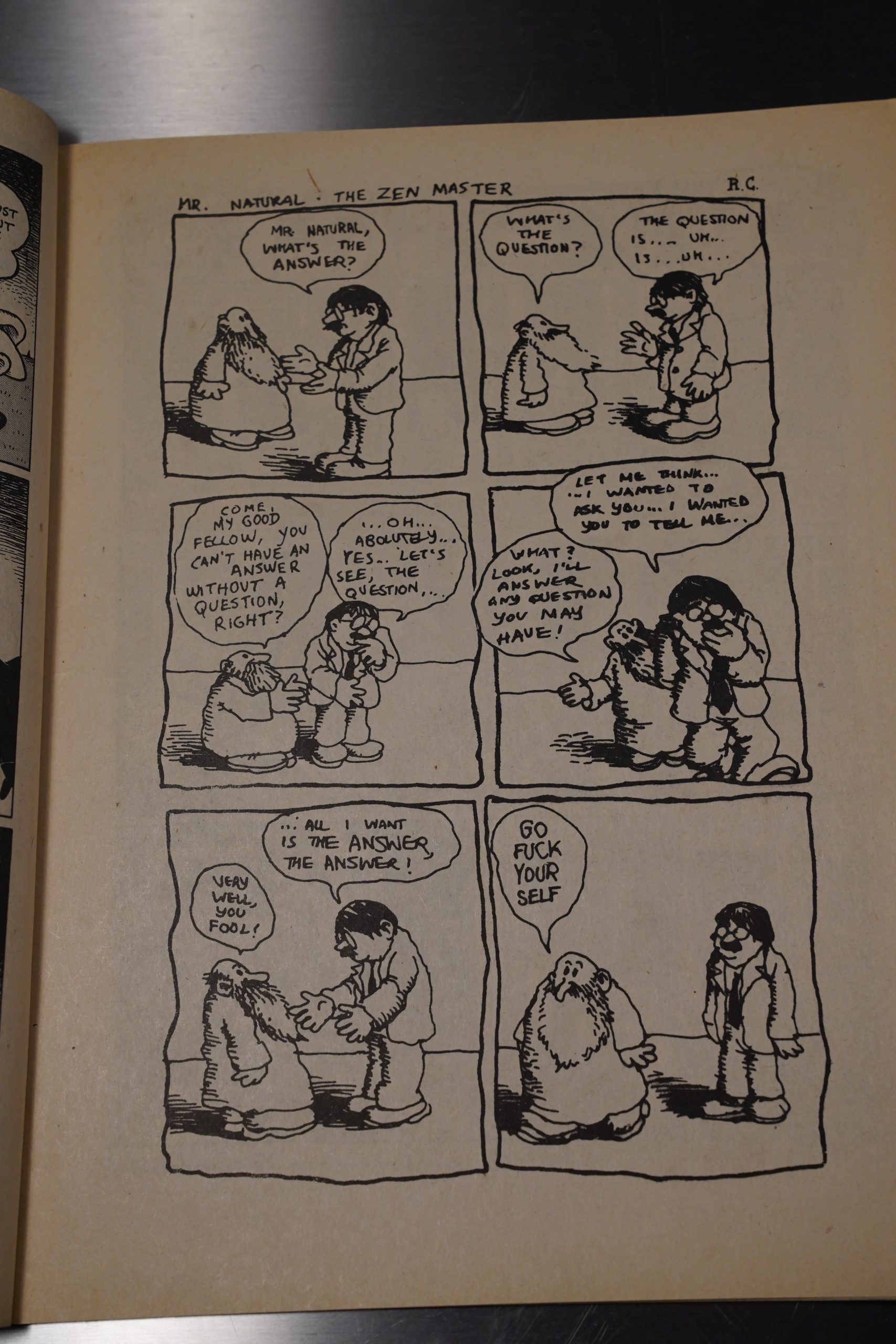

Life’s eternal questions.

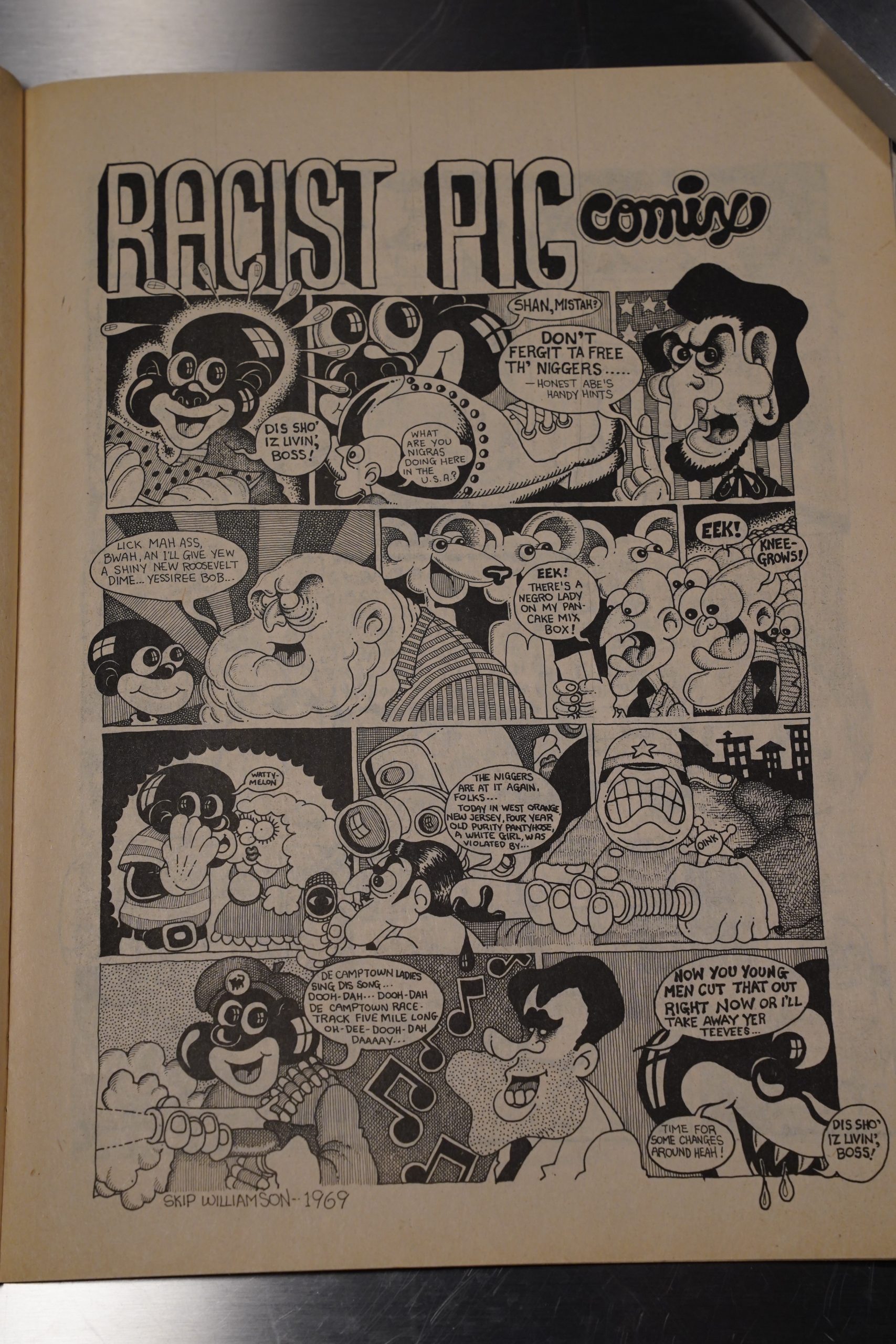

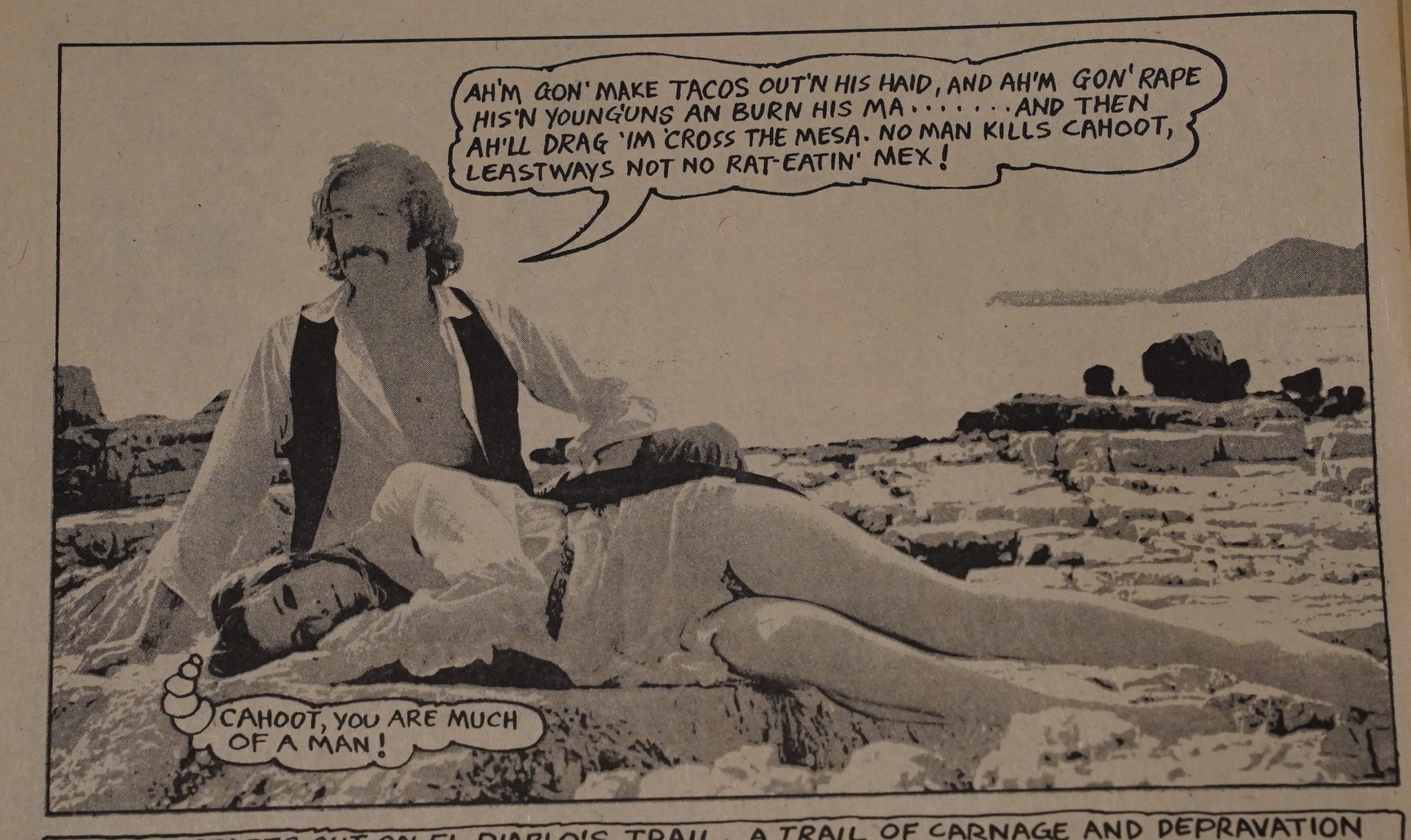

These books aren’t very political, but for one issue, a couple of pieces seemed to deal more explicitly with racism. But it’s a bit on the incoherent side. On the other hand, these are undergrounds, so…

What the… that Kim Deitch strip looks like a Chris Ware strip three decades later.

So these books are interesting, and they’re… they’re fine? But it’s hard to work up much enthusiasm, because the books seem so unambitious, even if some of the individual pieces are.

They don’t seem to build up to anything that coheres for the reader. Well, for this reader, at least.

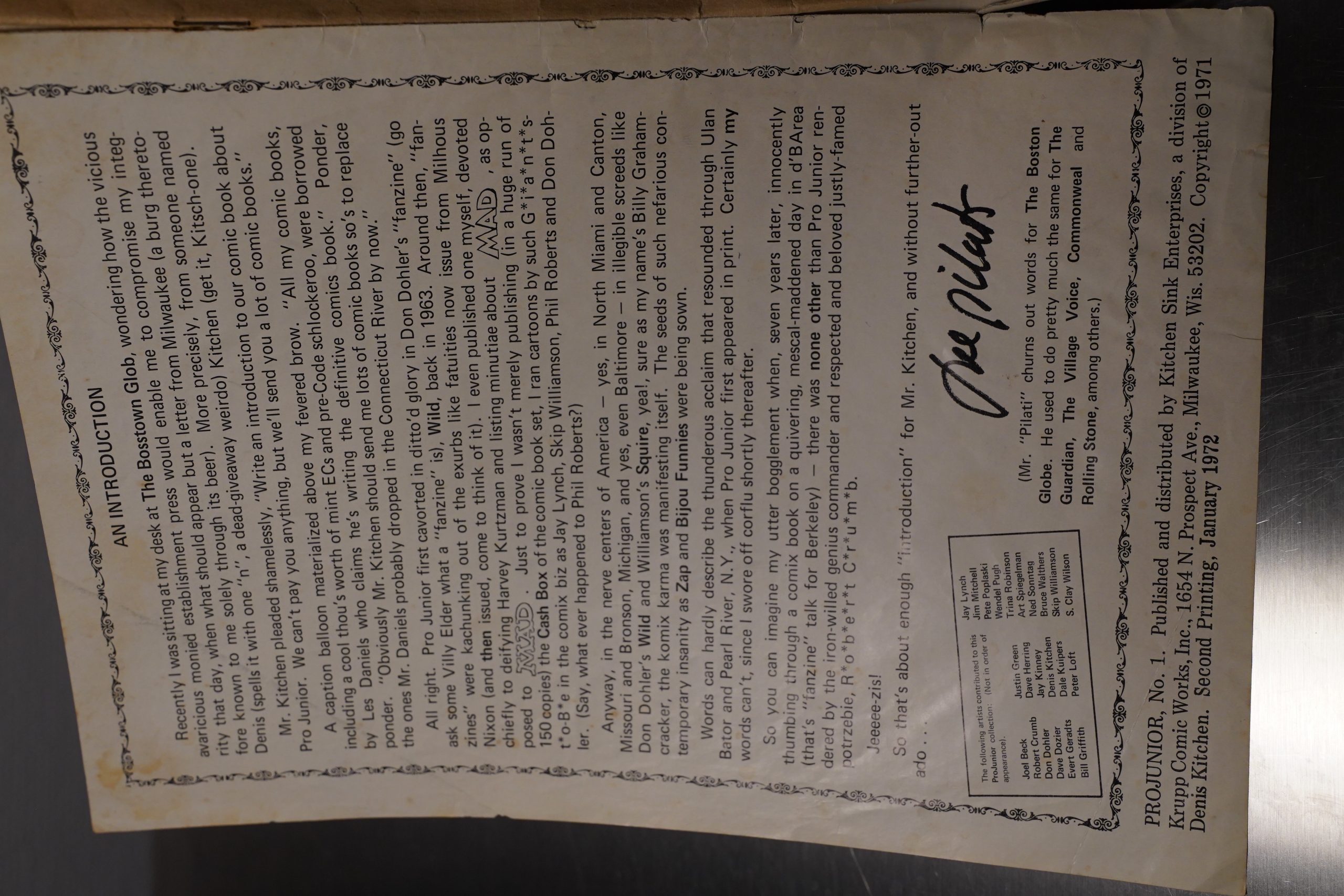

Kitchen apparently took over publication with the fourth issue, in… 1970? I think my chronology is a bit off here, because the comics.org site says that this is from 1972, but the indicia clearly says 1970. Or did he take over publication of subsequent printings?

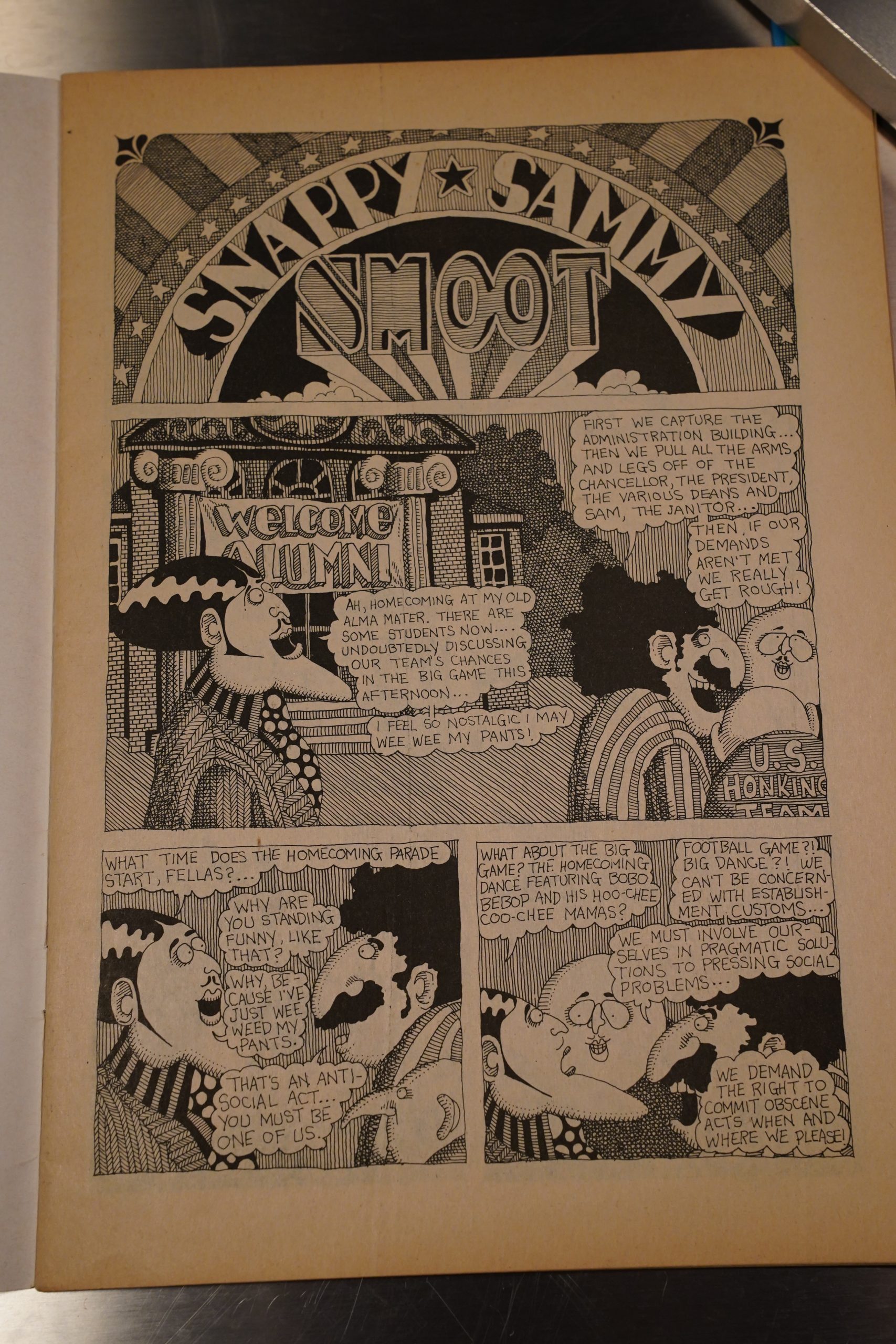

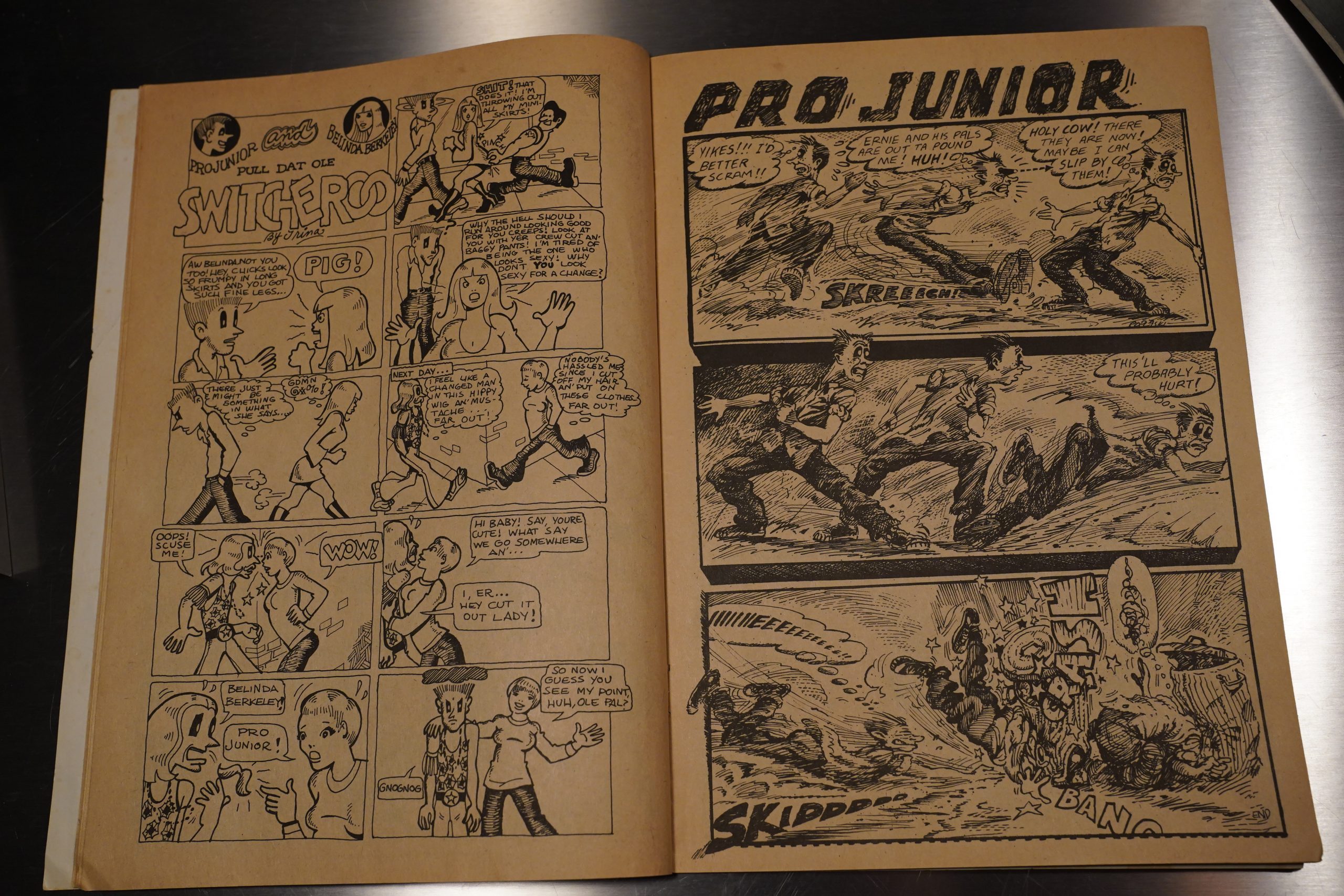

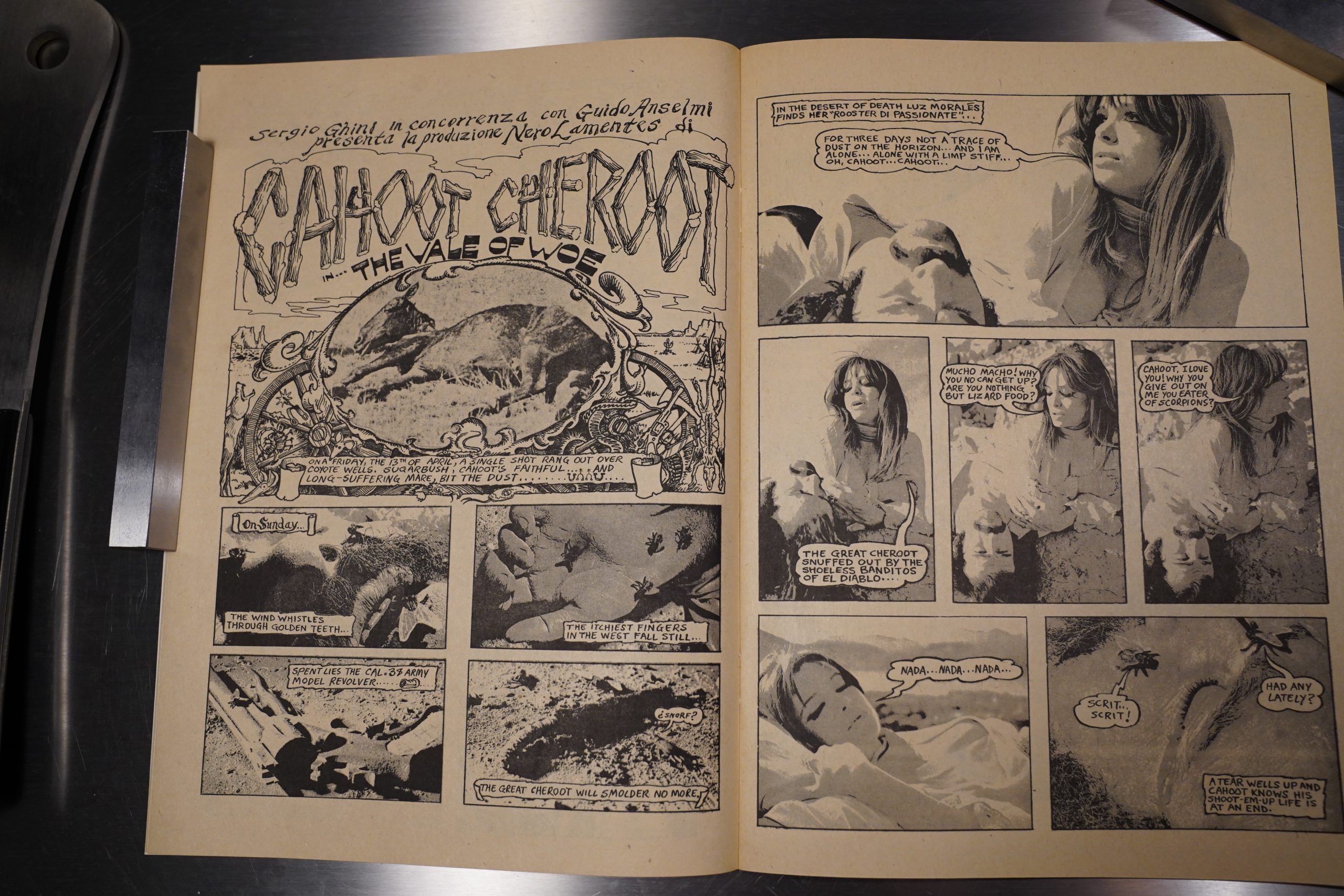

The last half of the run is a lot more ambitious than the first half. The pieces get longer, and there’s less random stuff. The regulars take up almost all the pages.

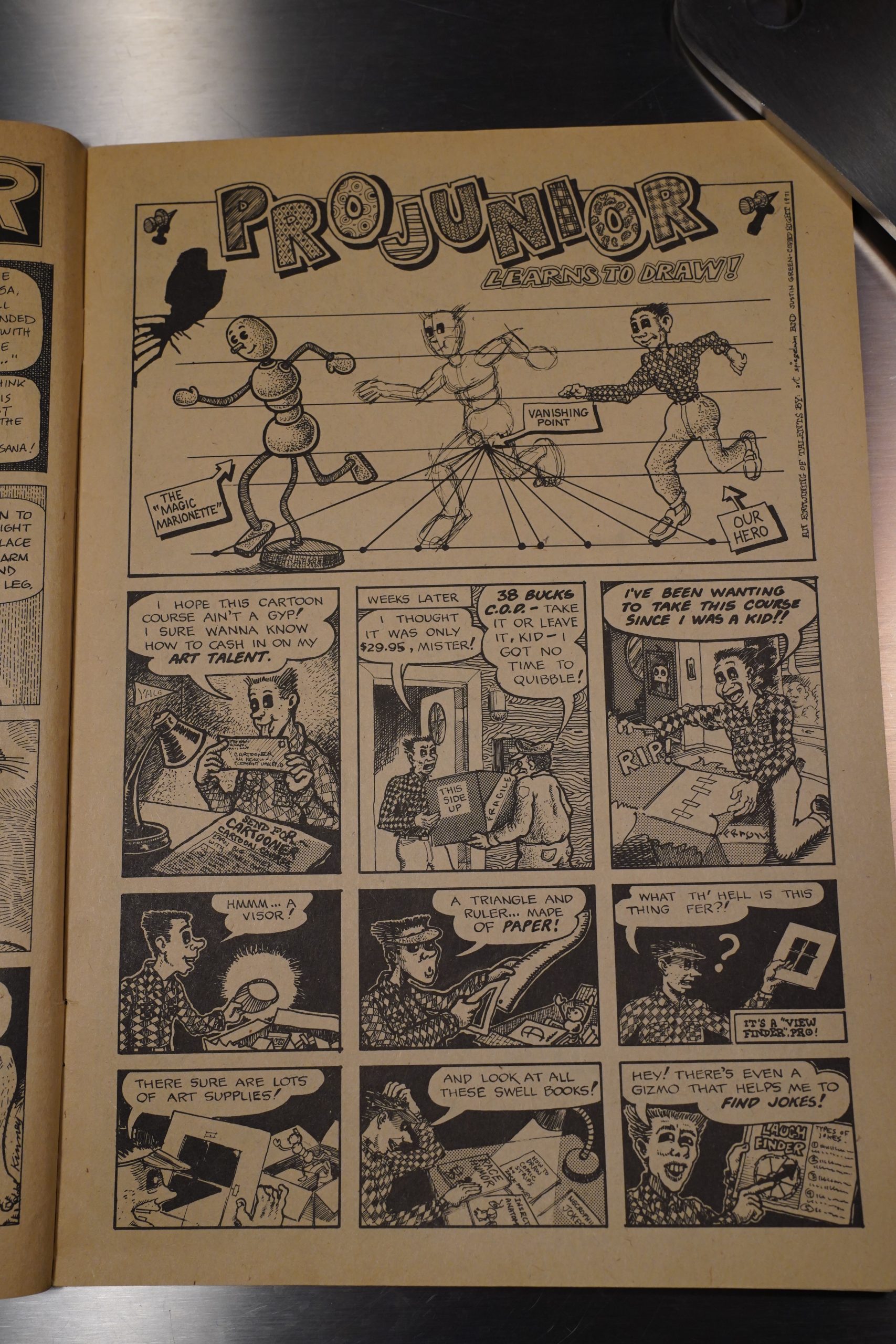

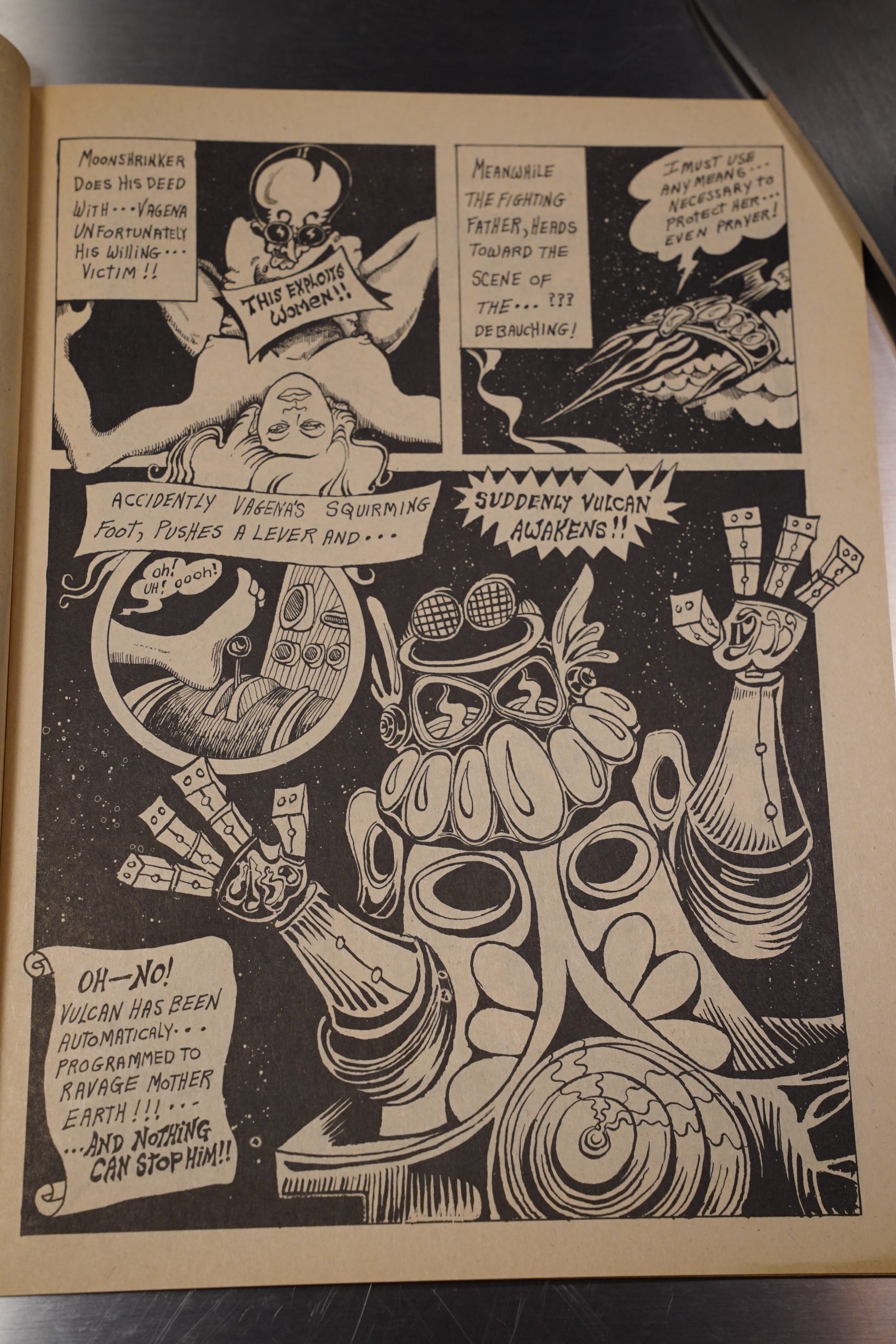

One of the regulars is Justin Green, and he embarks on some longer (well, eight page) drama things, like above. Before this, the book had basically been all yuks.

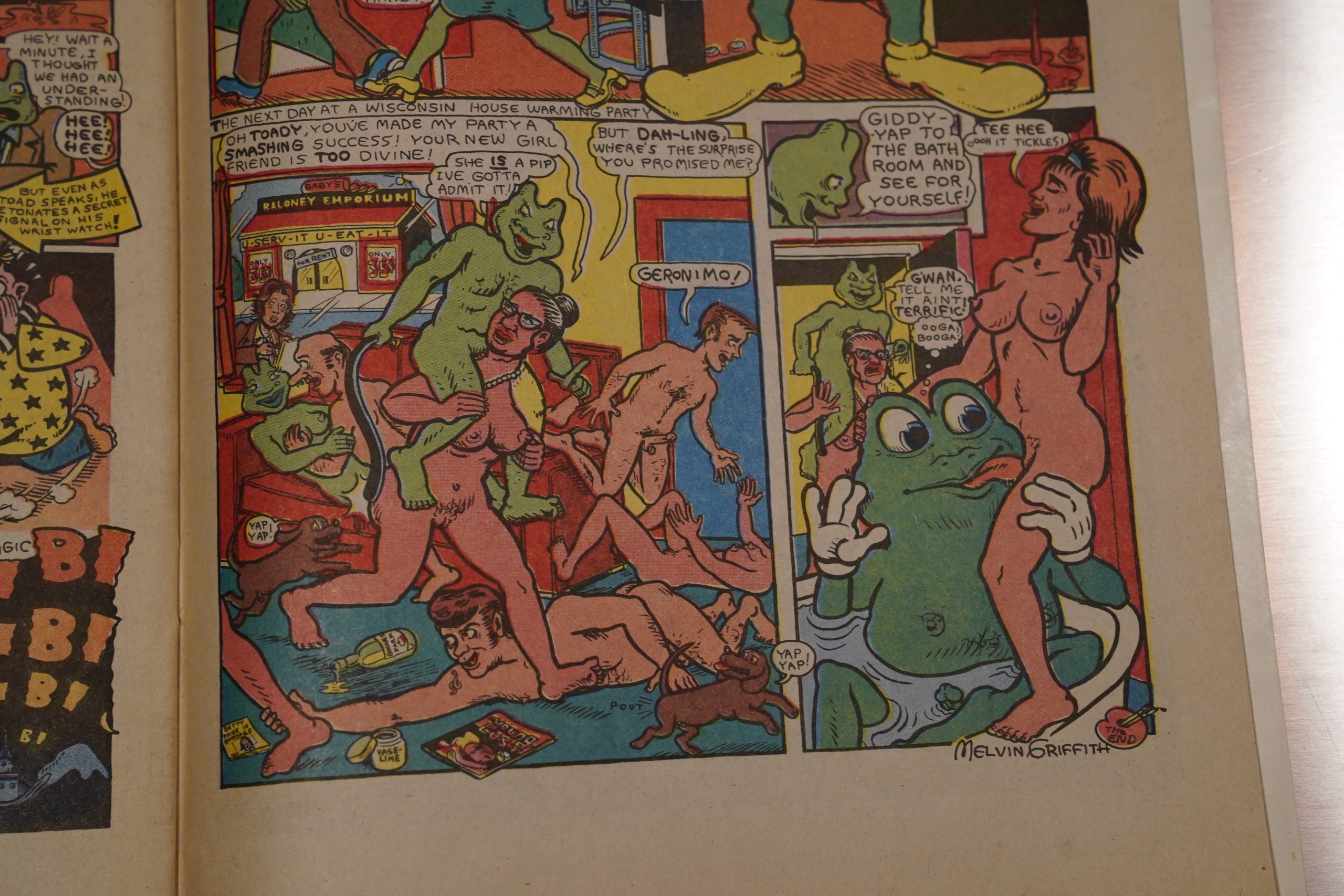

And Spiegelman drops by with an Viper strip, and he goes all out in trying in épatering la bourgeoisie: On the next page, there’s a scene that I’m not including here, because y’all are too squeamish, and…. I don’t want to. But it’s quite reminiscent of many a scene from Mike Diana’s comics from the 90s (which got him banned in Florida).

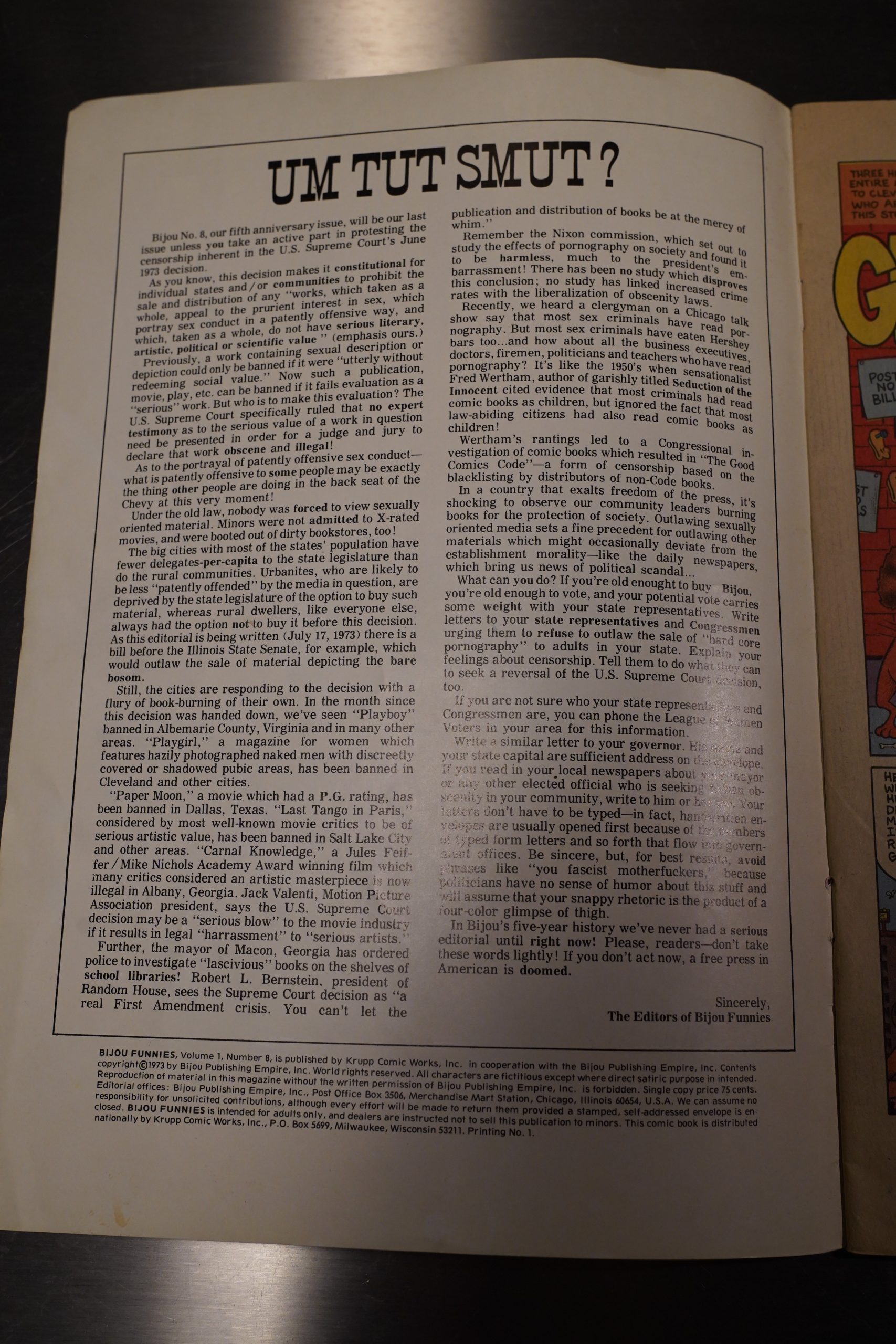

And the very next (and final) issue, there’s an editorial about censorship and stuff, which makes me wonder whether there had been a lot of block-back from the Spiegelman piece. It was, by several orders of magnitude, the most offensive thing in the series, and didn’t really… make any sense in this context at all.

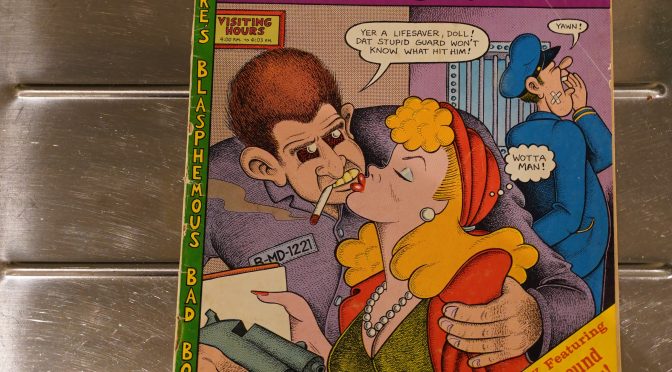

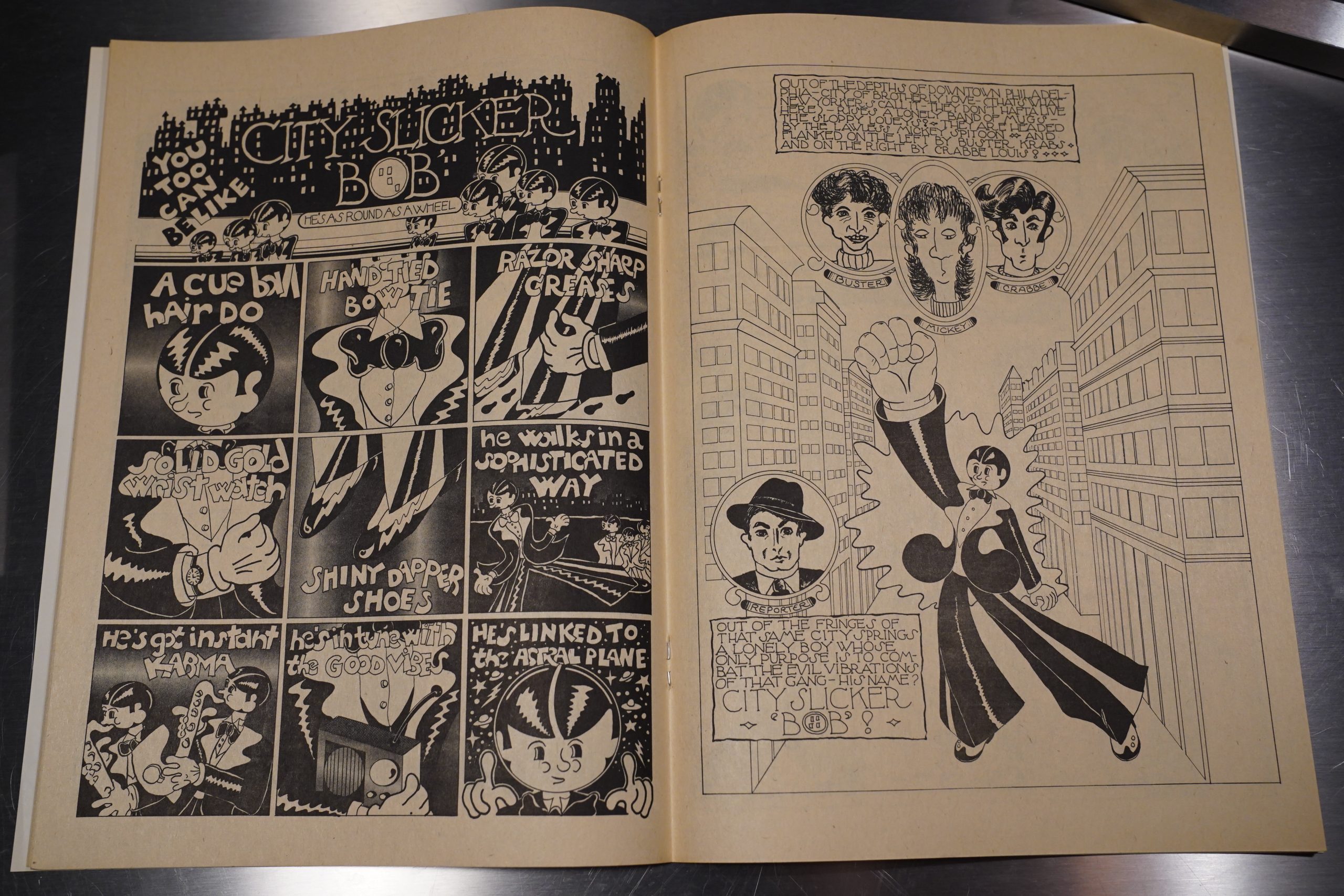

The final issue is normal comics size, and in colour! And it’s a concept thing: It’s basically a riff on what an issue of Mad Magazine might have looked like if it was all about doing parodies of underground comics.

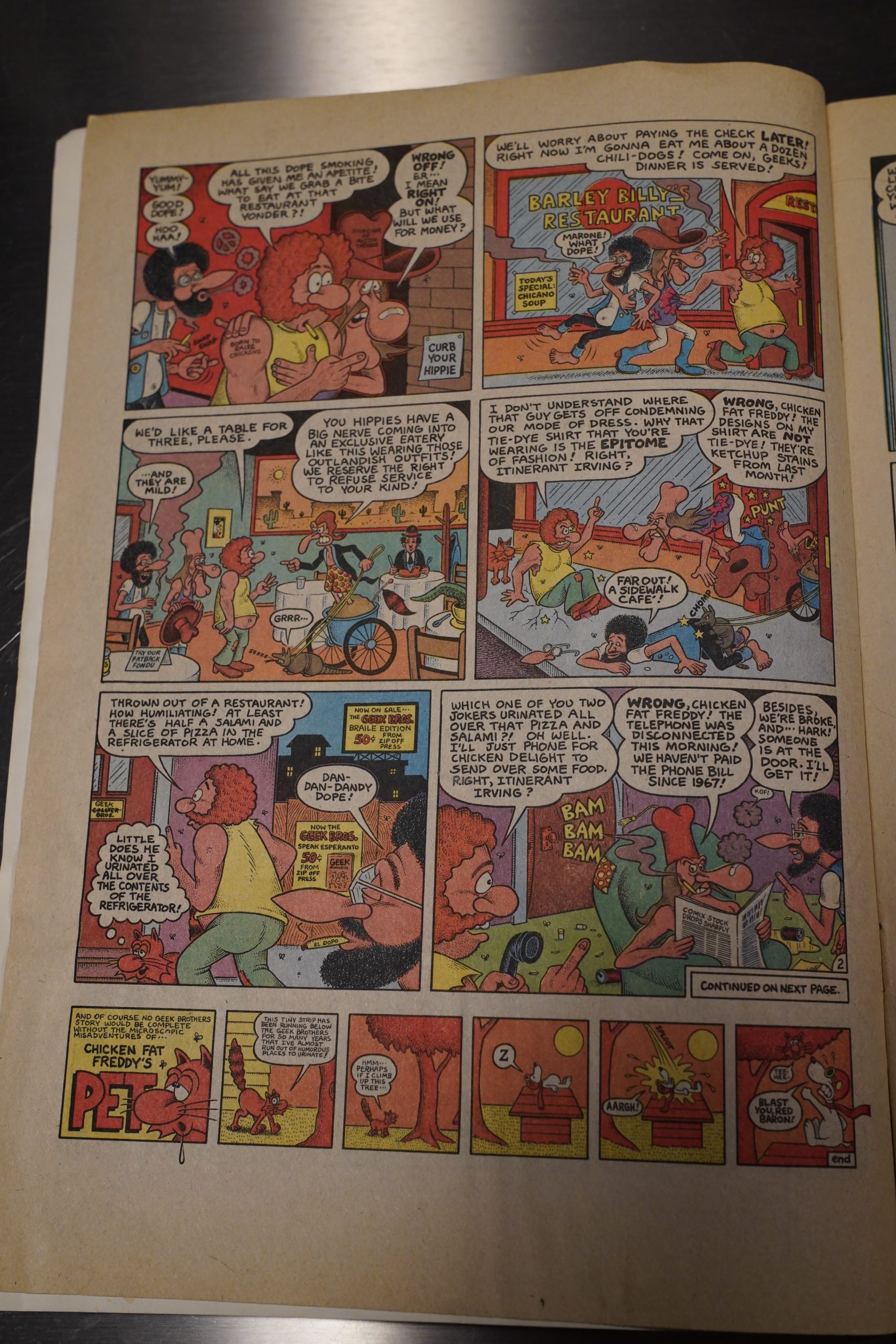

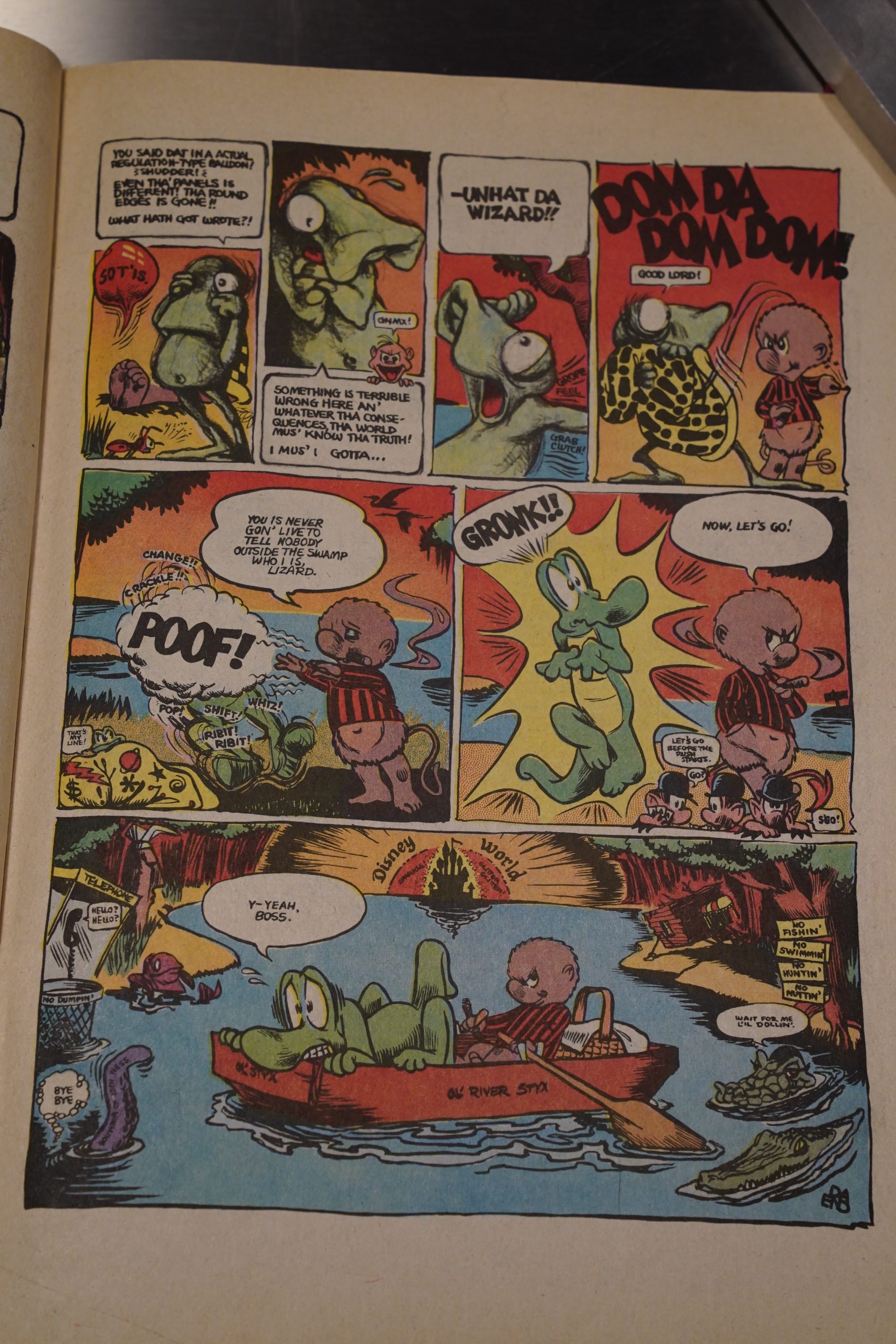

So here we have Jay Lynch doing Gilbert Sheldon…

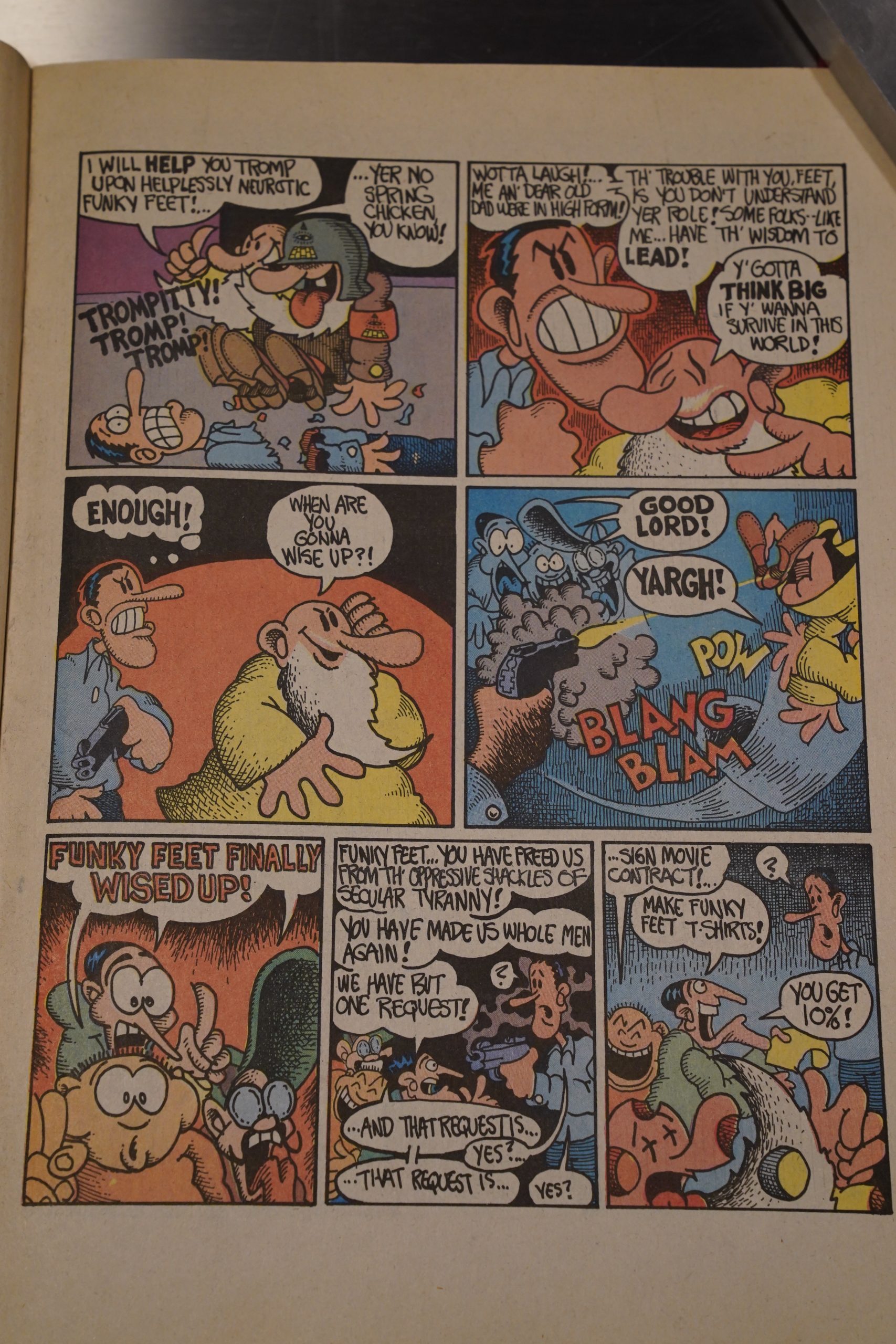

Here’s William Stout doing Skip Williamson…

Here’s Skip Williamson doing Crumb…

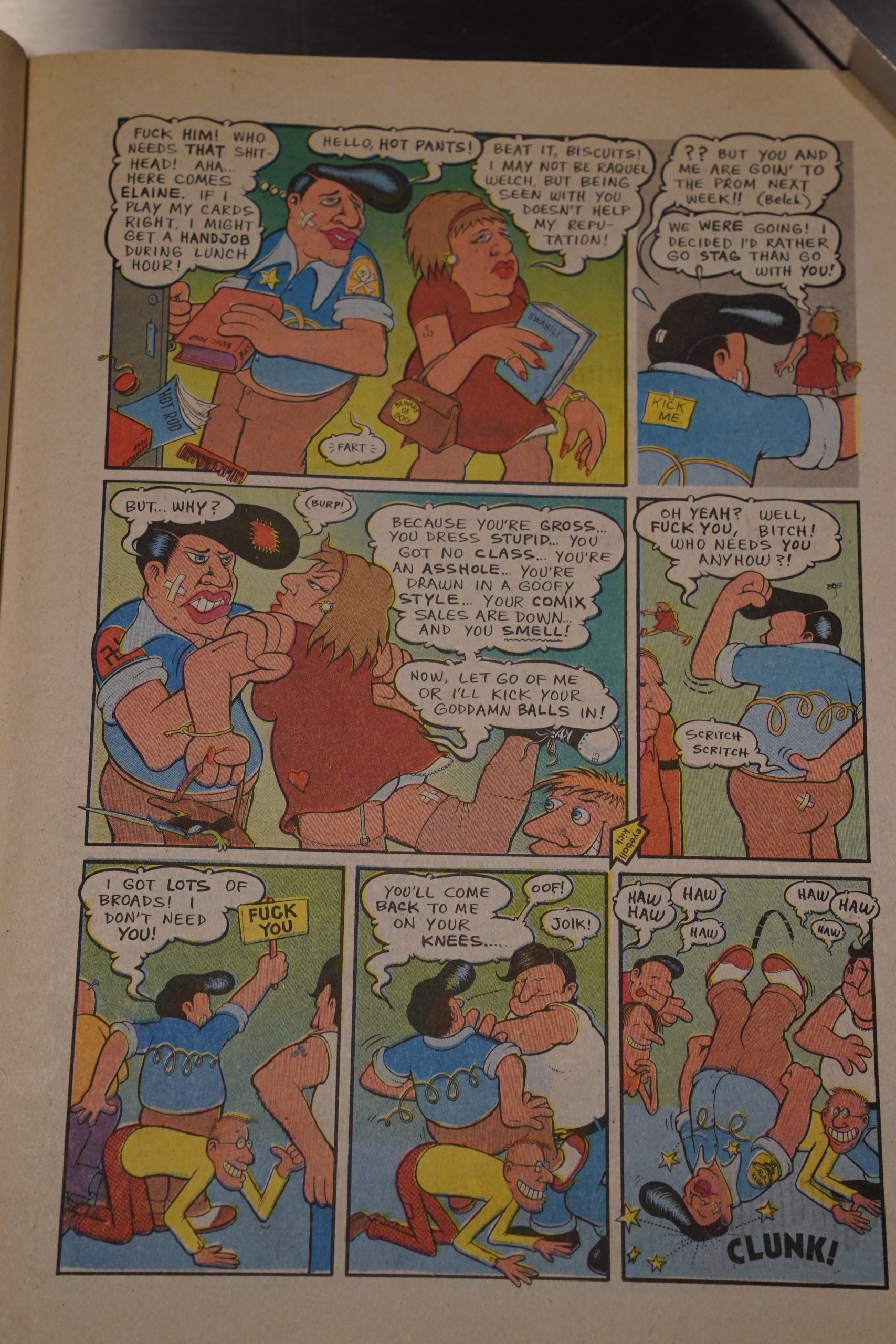

And here’s Kitchen doing Hungry Chuck Biscuits… but as parodies go, it’s a bit weak, because it’s so less far out than the original Hungry Chuck Biscuits comics.

Then! Suddenly! Somebody Dale does a parody of Cheech Wizard/Pogo? It’s not that it’s a bad strip or anything, but all the other ones had been parodies of people that had appeared in or near Bijou Funnies, so it just seems out of place.

We get back on track with R. Crumb doing Jay Lynch…

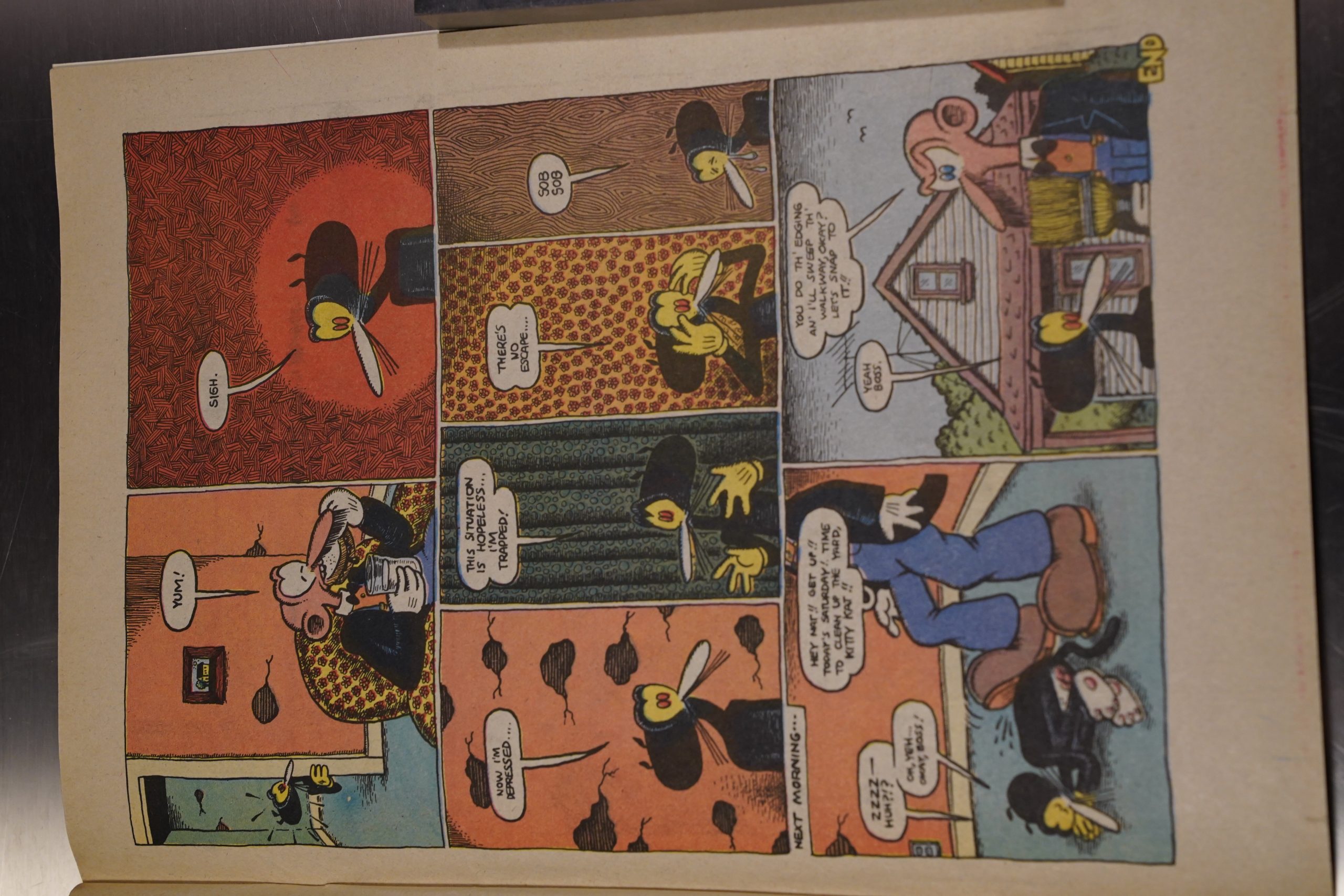

… and Bill Griffith doing Kim Deitch…

… and Kim Deitch doing Bill Griffith!

Yow.

So there you go.

I have to admit being disappointed by Bijou Funnies: It’s the one of the major, original underground anthologies I hadn’t read before, and I just thought… that it would be better? I mean, it’s good, but…

In many ways, despite the fact that it did not originate from the womb of the underground movement in San Francisco, Bijou Funnies parallels the history of underground comics like no other publication.

[…]

The inaugural issue of Bijou was a flawed, amateurish comic book production, like so many undergrounds that served as learning projects for publishing pioneers (Don Donahue, Rip Off Press, etc.). In the late ’60s Bijou introduced new artists and exposed them to a wider audience, just as many underground publishers threw open their doors to print anyone with a counterculture pedigree, no matter how horrible the comics were.

But by the early ’70s, Bijou began to rely on its core stable of creators to provide content for their book, as did the broader underground comics movement, which was financially burned by inferior content and slow-moving titles. Like the best of the underground comics, Bijou hit its peak in the early ’70s with outstanding contributions from a handful of legendary comic creators.

Yup.

And:

There are four printings this comic book, all by Kitchen Sink Enterprises, all producing approximately 10,000 copies

Oops. So I’ve got the wrong date up there — this should have been under 1970, not 1972.

Lynch is interviewed in The Comics Journal #264, page 121:

ROSENKRANZ: How much is your publishing

empire worth today?

JAY LYNCH: The net worth Of the Bijou

Publishing Empire as of today, which is

December 5, 1971, is $38.15 and that’s

not even our money. That’s the compa-

ny’s money. The reason Skip and I

formed Bijou Publishing Empire as a cor-

poration was mainly to have a bank

account to collect money from our dis-

tributors and pay our artists. The corpo-

ration make any money and con-

sequently doesn’t pay any taxes. I guess it

only costs about $200 a year to keep the

corporation alive. The primary function

of Bijou is to split the profits among the

artists. We pay $20 a page for every

copies Of Bijou that are sold and

that represents what we make on Bijou

We make for every that are

sold, and itk split among the artists, each

one gets $20 a page. Actually the compa-

ny comes out in the hole, but the way

thatk worked out is nobody got paid for

the first two issues of Bijou, so these two

issues absorb whatever loss it is. Now

we re working on another comic book

called Rory Funnies. It’s a sister magazine

to Bijou and it will contain material by

the Bijou artists. It will be kind of like

what panic magazine was to Mad maga-

zine. That’s what Roxy will be to Bijou.

I’m doing a Nard N’ Pat book, too, but

that Will take a long time to complete.

Print Mint interviewed in The Comics Journal #264, page 120:

ROSENKRANZ: had the rightsfor Bijou

Funnies fir a while. Why does Krupp have

it now?

SCHENKER: We did Bijou. I had a very

nice working relationship With Jay Lynch,

until Krupp came into the thing. Kitchen

started saying a whole bunch of really

nasty things about the Print Mint. It was

really a bunch of lies. Everybody seemed

to be down on the print Mint for some

reason. We got very uptight. There were

a lot of articles written in underground

newspapers that folded right away before

we could get a chance to get back. A

whole lot of really nasty shit was coming

down about us — about how we were

rip-offs and capitalistic pigs.

ROSENKRANz: Why was that? Because pu

had the most comic books?

SCHENKER: I guess so.

RITA: Because we were the establishment

at the time. We were the establishment

selling underground comic books. We

had distribution that was not there

before. We created the market.

ROSENKRANZ.• That doesn’t seem like a valid

reason for criticism, though.

RITA: Well, What are they going to do?

Blame General Motors? It’s almost logical

that they would do that, because they

were starting up their own companies.

They had no basis from which to work

outside of art. Art is one thing, but sell-

ing and distributing something, that’s

something else.

Drama!

This is the eleventh post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.