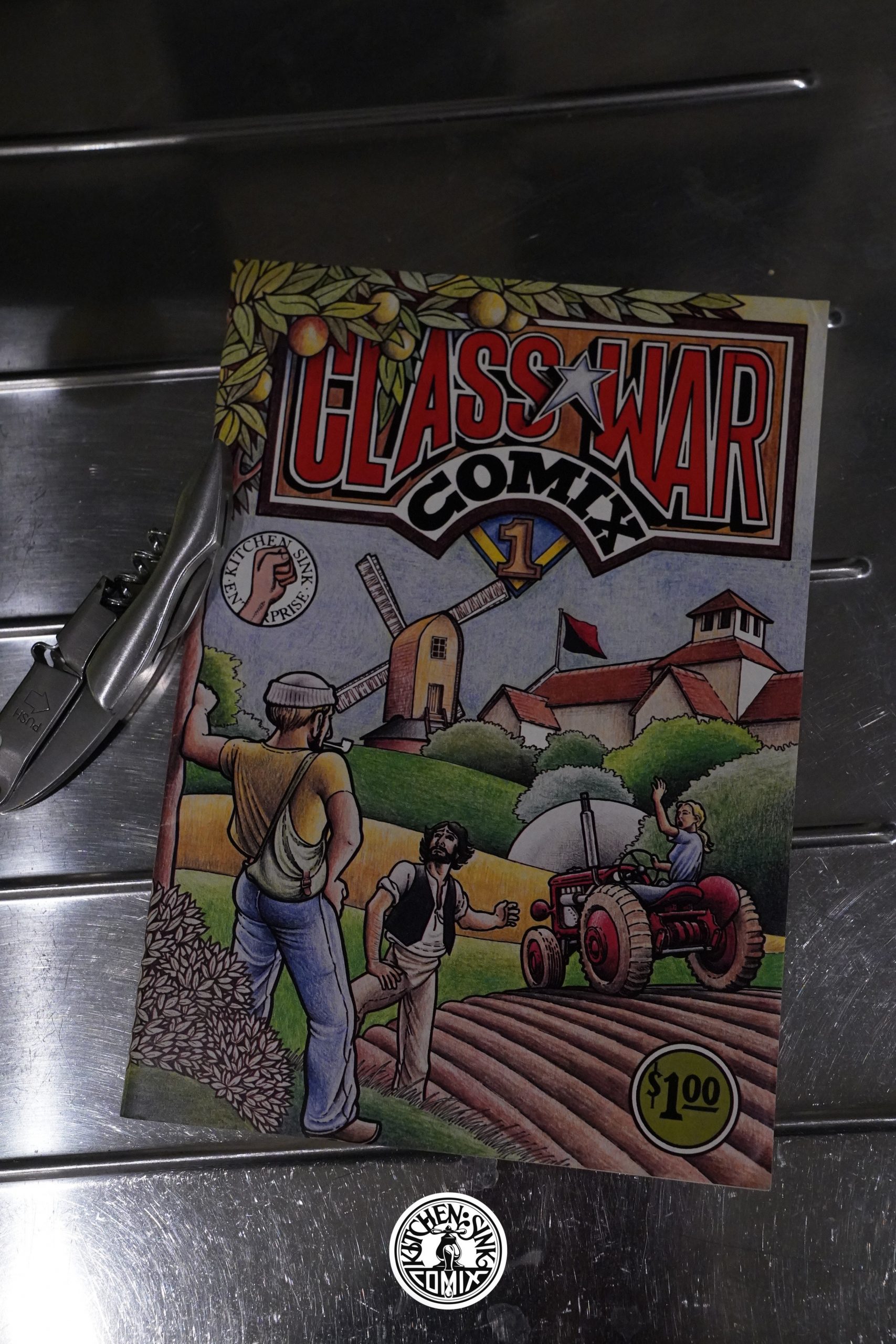

Class War Comix (1979) #1 by Clifford Harper

As with many of the books Kitchen was publishing at the time, this is a reprint of book published earlier by somebody else — but this time around, it’s a British underground comic (that was abandoned, Jay Kinney explains, because of the lack of reaction).

The artist explain in the afterword that the artwork was done before having a story (or script) in mind, but it seems clearly narrative, so I suspect that he meant that he hadn’t written the words.

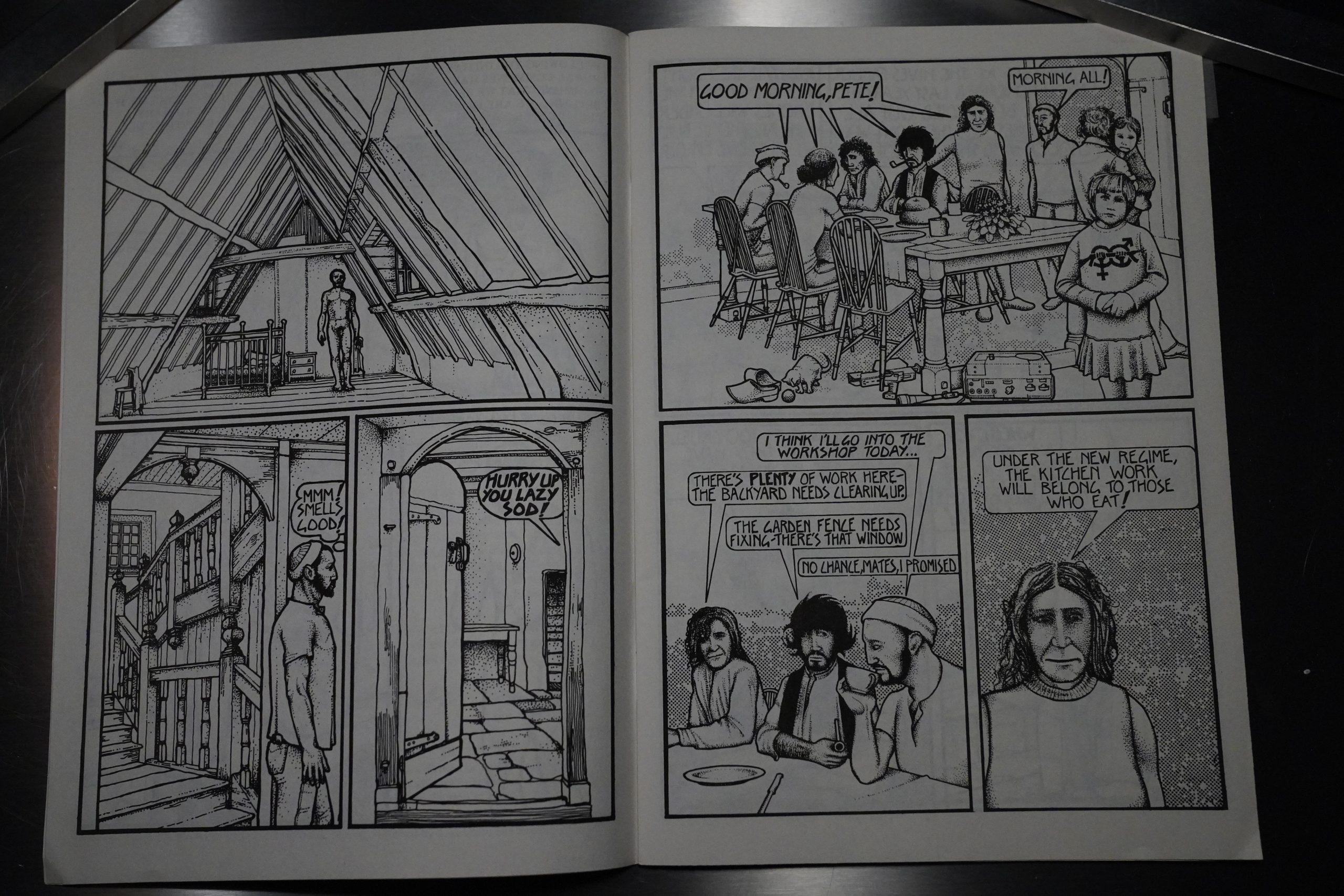

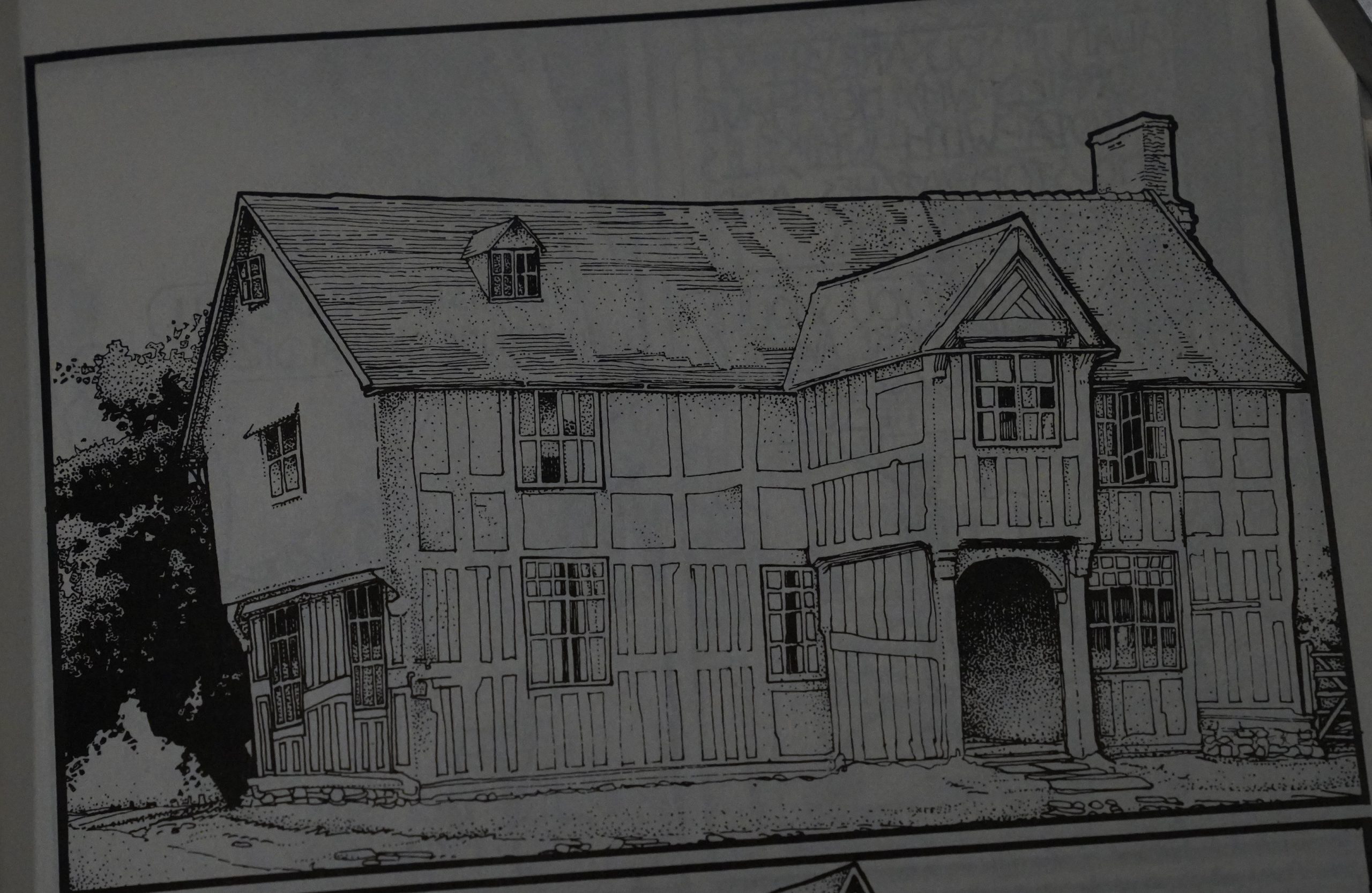

The artwork looks like it’s referencing photos a lot. Or rather — that he’s tracing photos. But that’s a very nice house.

Whenever he’s not drawing people, it looks pretty good?

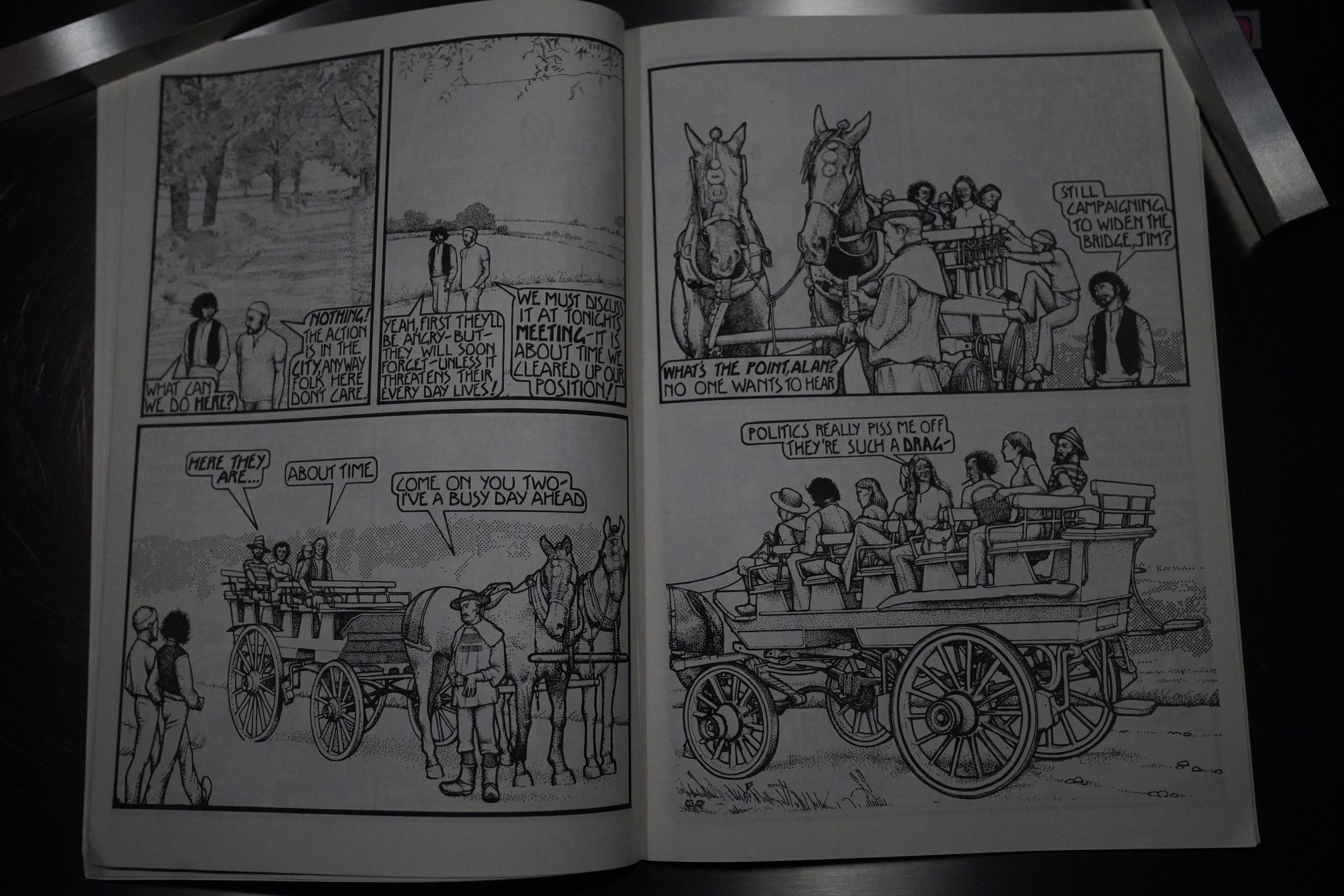

The storyline is about living on a commune in the near future (there’s been some kind of societal breakdown), and it’s pretty interesting.

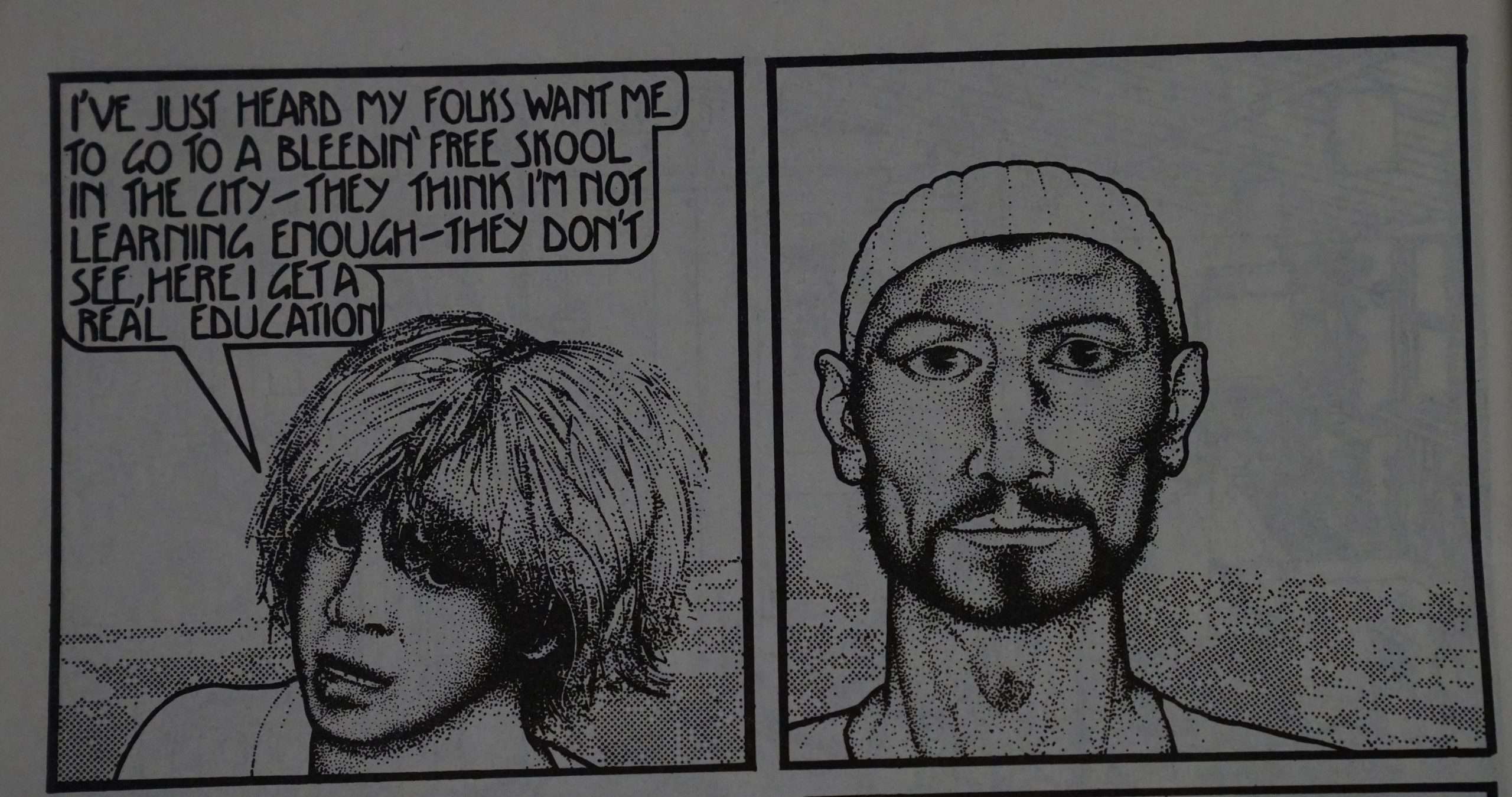

The faces go from very odd indeed to quite nice.

But… how on earth was this done? I guess that’s mechanical tone in the background, and then the linework looks inked as normal, but all that stippling… if this had been made ten years later, I would have thought that this had been (partially) printed out on a dot matrix printer, but surely that’s impossible in 1974. So it’s just obsessively dotted?

He’s spent a lot of time on the rendering, and not that much time in getting the faces quite right to begin with.

David Stallman writes in The Comics Journal #56, page 79:

“A revolution does not march in a

straight line.

‘—Mao Tse—Tung

Class War Comics is the first of

six possible eomix about the

organizing of an embryonic anarchic

society after a successful class

revolution in Britain, and the

personal and political problems that

Would confront the participants and

beneficiaries Of the revolution.

The story takes place in a rural

commune, composed of several

autonomous collectives (carpentry

farming, etc.) , and the characters

are shown going about their activi—

ties, while expressing and debating

the Various organizational, political,

and personal difficulties they face.

The major developing conflict is

that the socialist bureaucracy ,

which replaced the former capitalist

system, is beginning to adopt a

repressive policy against the urban

workers and against the anarchist

elements determined to dismantle

the bureaucracy’s power. The

commune members are reluctant to

become involved in this distant

growing political battle, but they

are aware that they will eventually

have to, as it may threaten their

own autonomy.

Harper’s main statement is that

after a class revolution, the great

expansion Of freedom does not

entail a unanimity of political and

social views, but rather a diversi—

fieation. Unity exists in the desire

to create a better existence, not in

how to accomplish it. It is this

diversity of views that is at once

the wealth and retardant of an

ongoing revolution.

The main political conflict between

the party and the free anarchists

in the book is not new and has been

around since the battles between

Marx and Bakunin in the First

International. The question of

centralized power (the state) vs.

decentraUzed power (the rights Of

local organization and individuals)

has erupted in the past into shooting

Wars between communist and anar—

chist (for example the Russian and

Spanish Revolutions) . It will be

iriteresting to see how the conflict

progresses in the series’ possible

Harper’s beautifully detailed

artwork includes exquisite drawings

of English manors, farmhouses, and

countryside that superbly create

a believable rural atmosphere. His

stippled shadows and interiors Of

forms pr•oduce a light, open air that

is easy and pleasurable to view.

Simply, the book is a visual delight.

In his afterword/ Harper apolo-

gizes for the rhetoric in the book I

feel that the use Of rhetoric is

appropriate considering that it

would be bandied about in such

political situations, but if he wishes

to make it more elegant and eloquent ,

I certainly have no objections as long

as he continues to directly address

the political issues.

Right on, Comrade.

Harper didn’t continue the book, but he’s a successful illustrator.

This is a well-drawn, fascinating tale about real people, communal living and the potential complications of living outside normal society.

This is the fifty-second post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.