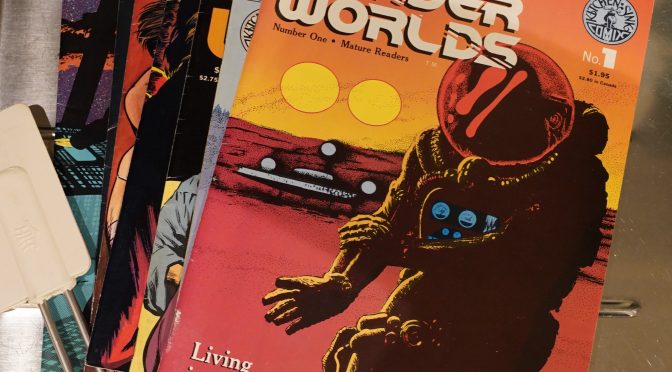

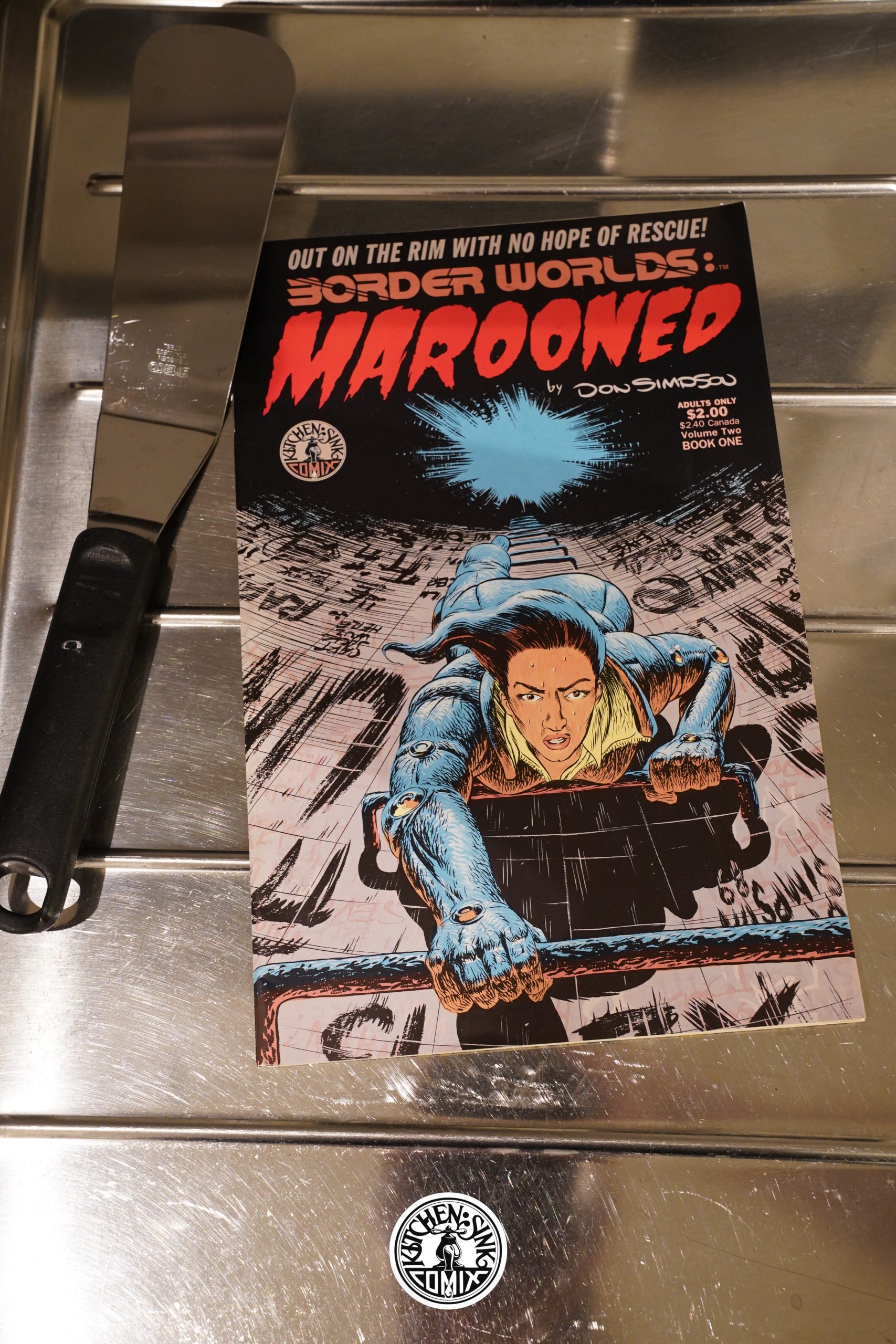

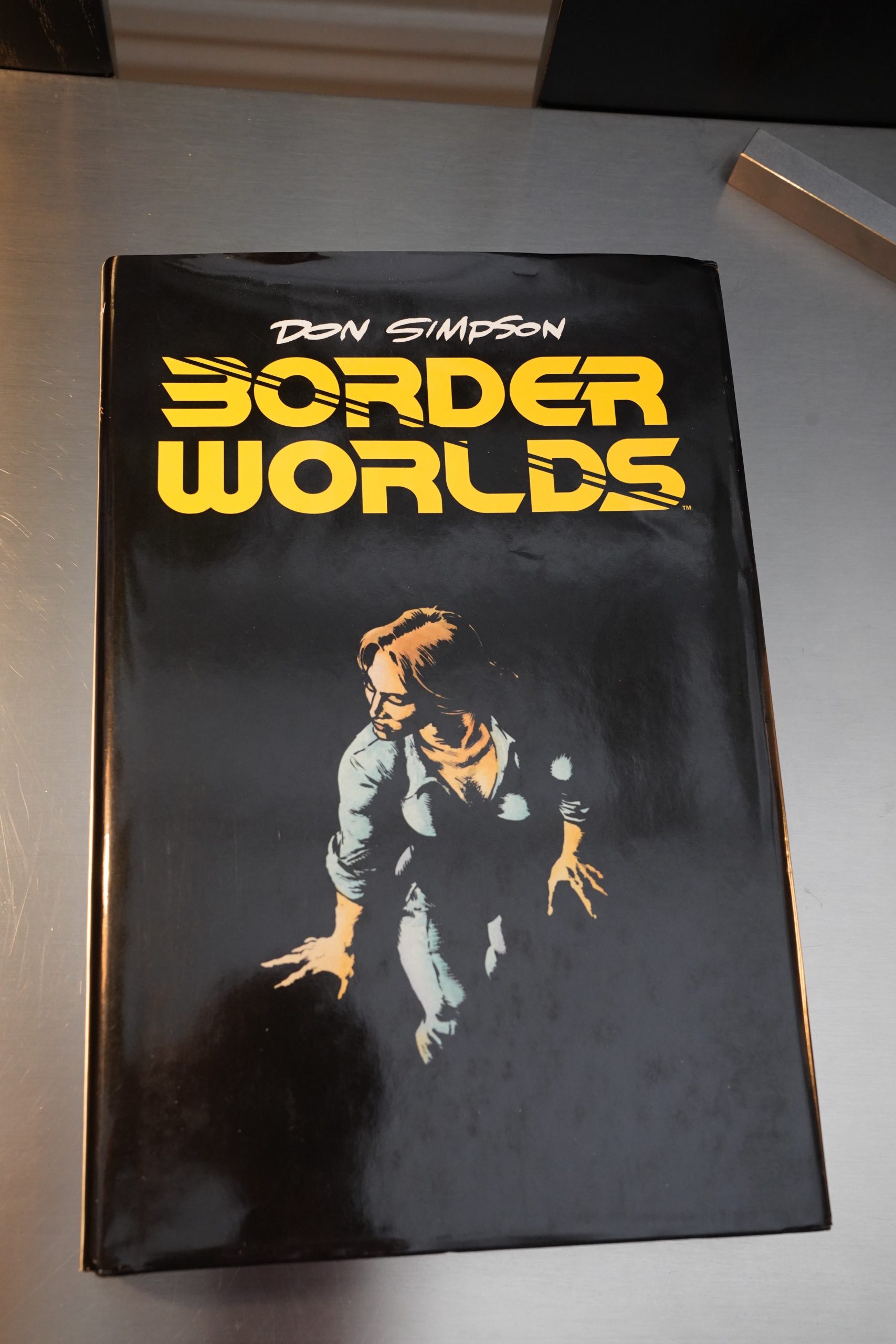

Border Worlds (1986) #1-7,

Border Worlds: Marooned (1990) #1 by Don Simpson

I had these comics as a teenager, and I remember them being really good? But I don’t really remember any specifics. Then again, I was totally into anything that was science fiction, so who knows. Anyway, I’m excited to read this again.

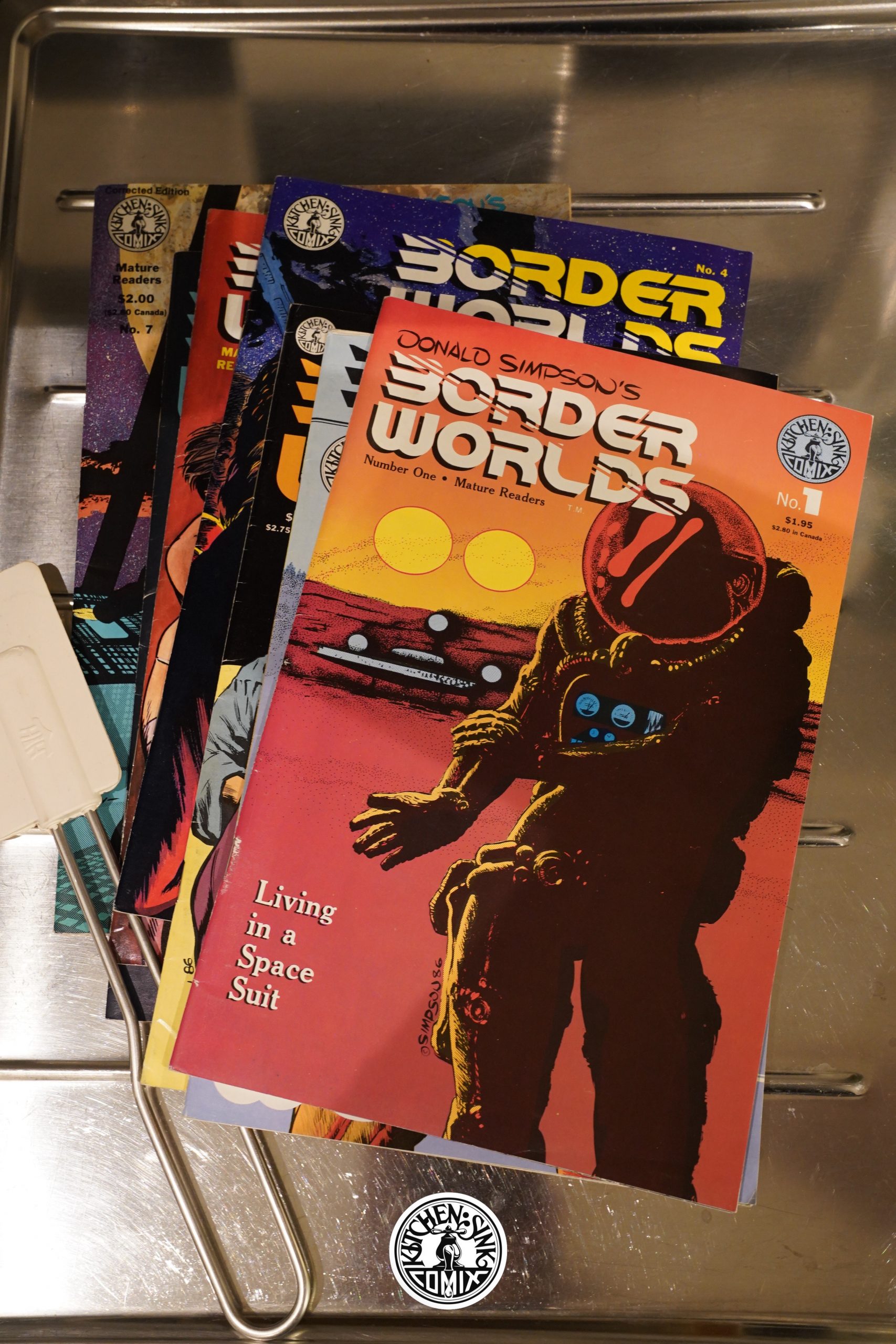

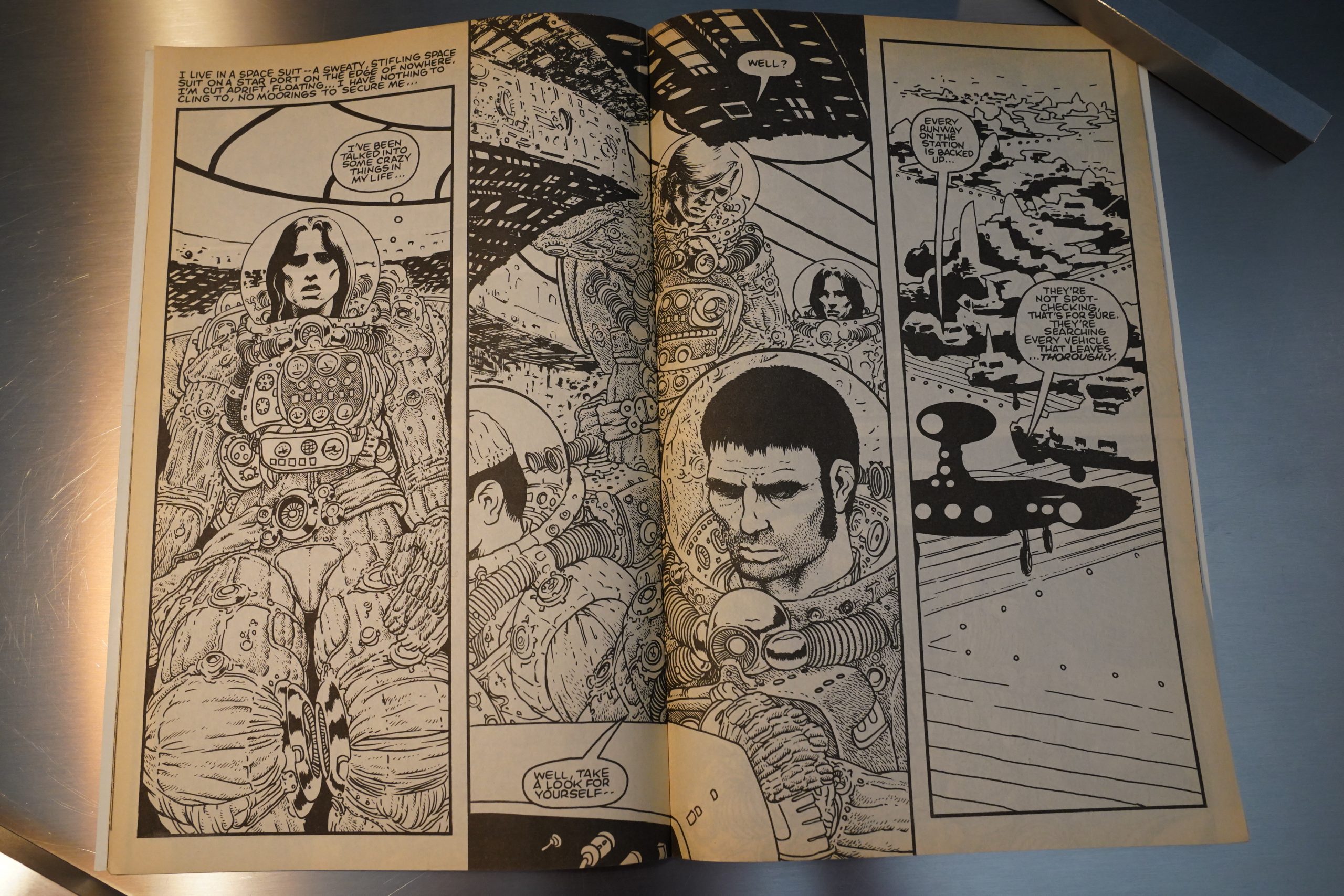

The book starts with a strong hook: “I live in a space suit.”

Which is a bit of a tonal shift from the first five chapters, which ran as backup features in Megaton Man. Those chapters were pretty light-hearted misadventures on a space station, but this seems to be setting a vastly different tone from the first page on.

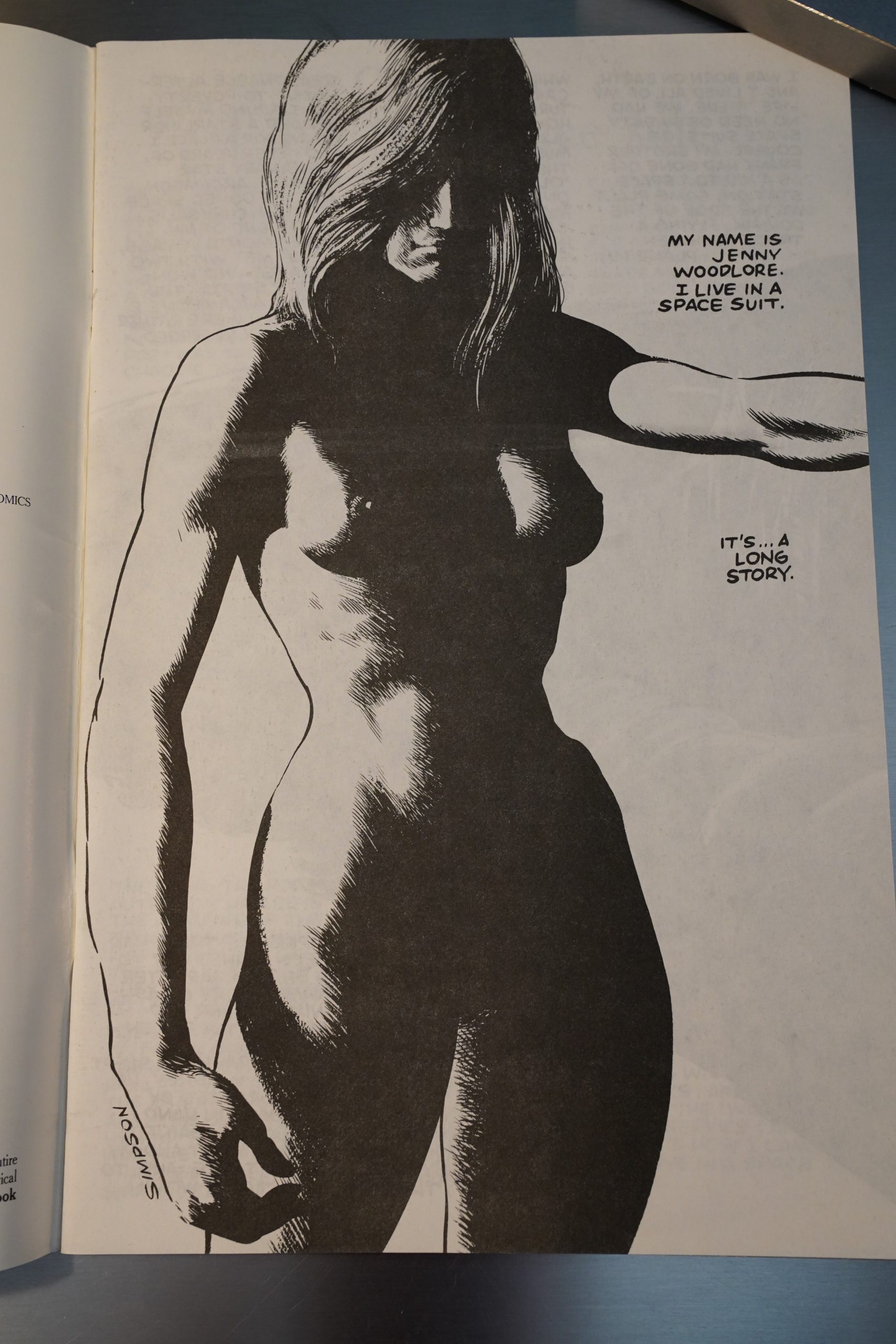

But then… we get a whole chapter of recaps. It’s not that anything that happened the first five chapters really need explaining — you could just have started them doing some stuff, and then brought in some “Bob, as you know” bits as needed — but not much is needed, really! They have a spaceship! That goes fast! And they need money!

That’s all you need to know.

So if course it goes on and on and on.

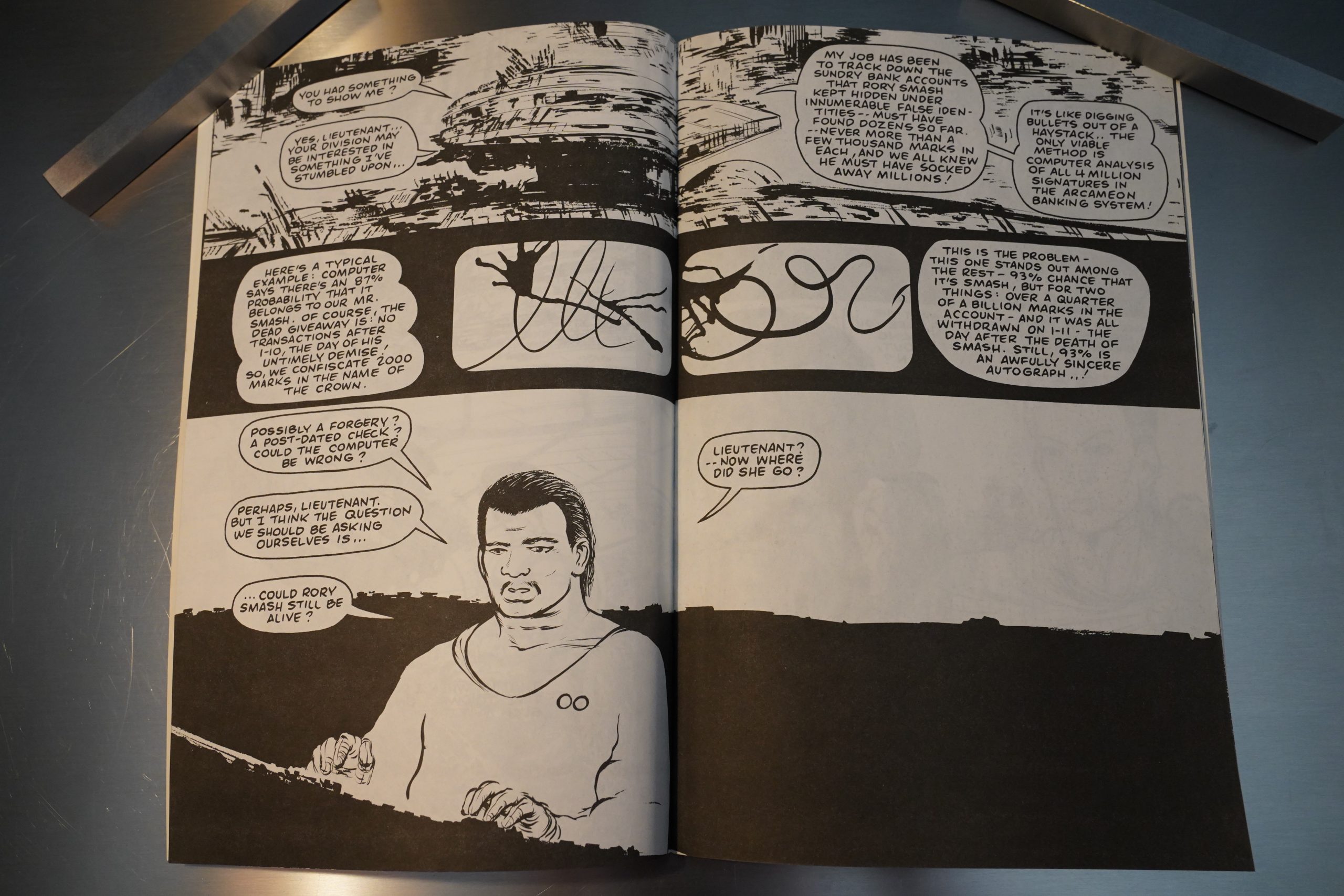

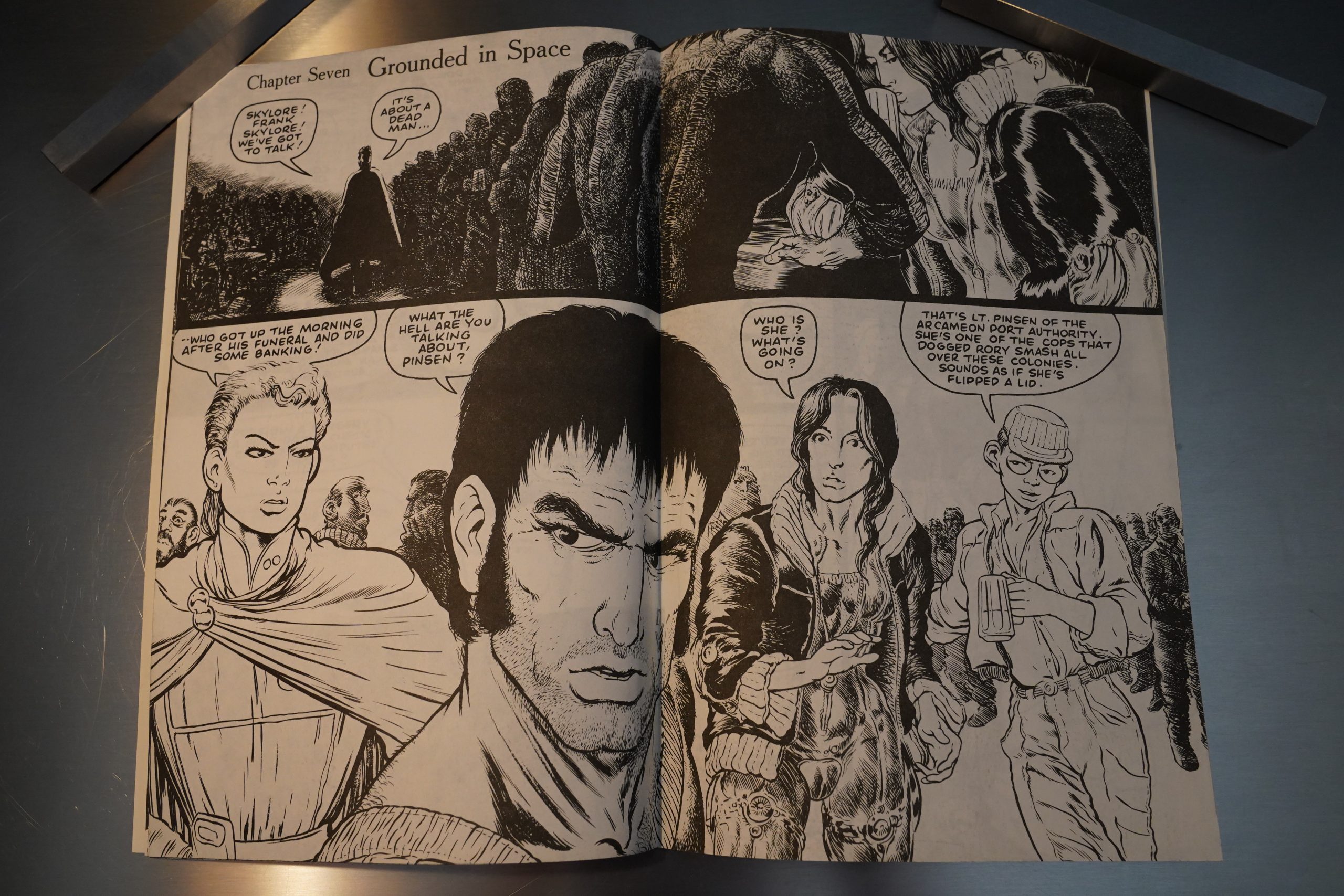

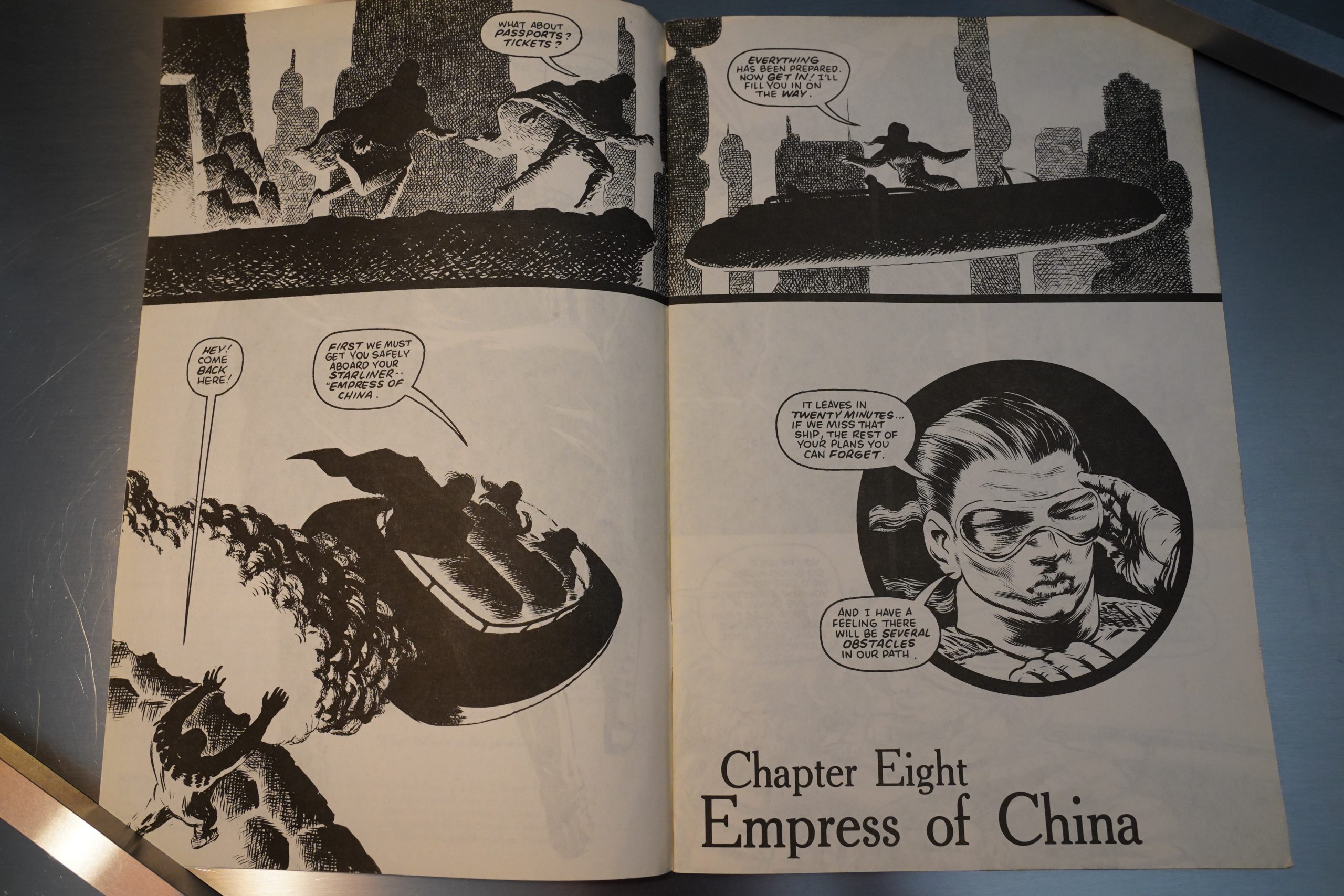

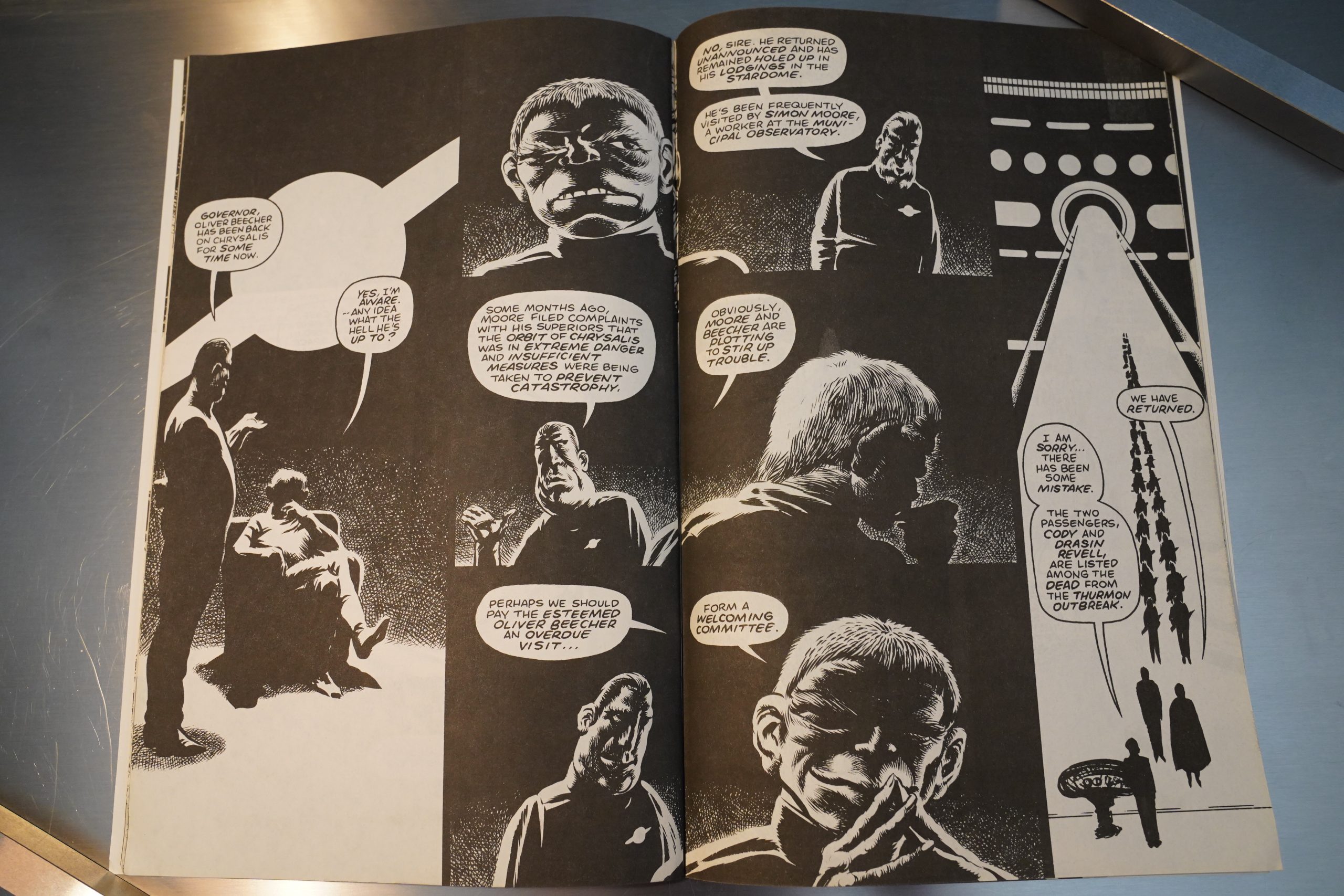

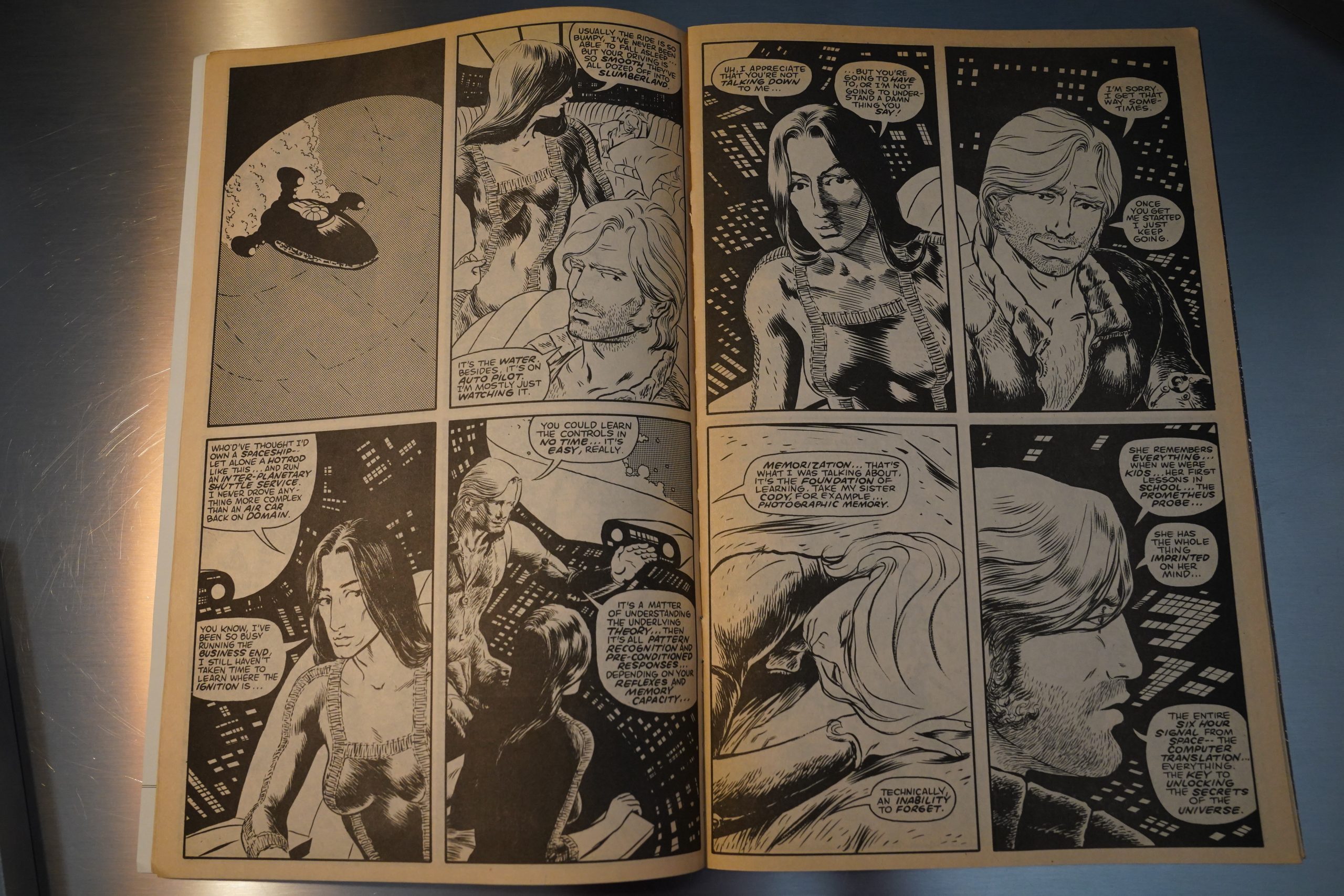

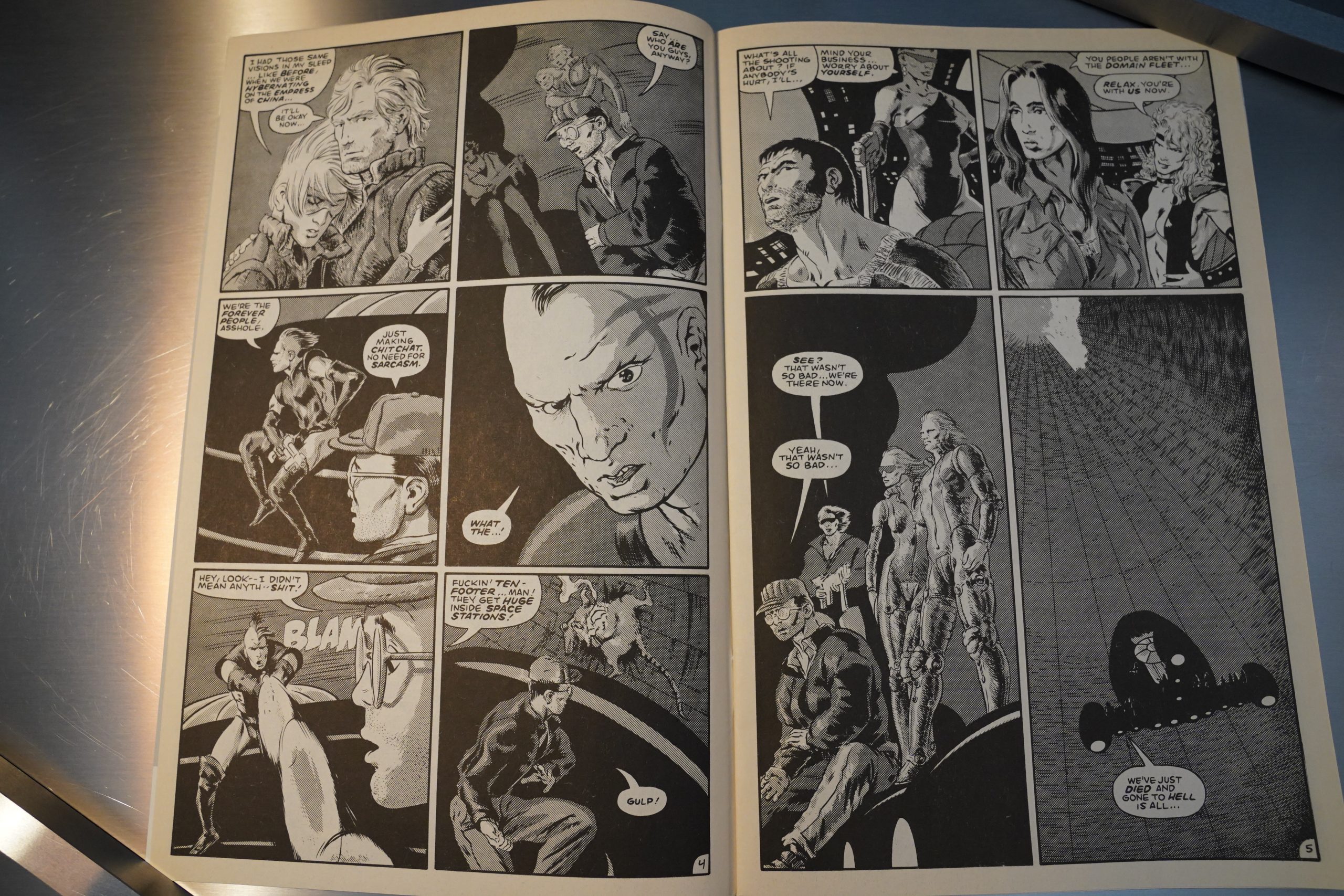

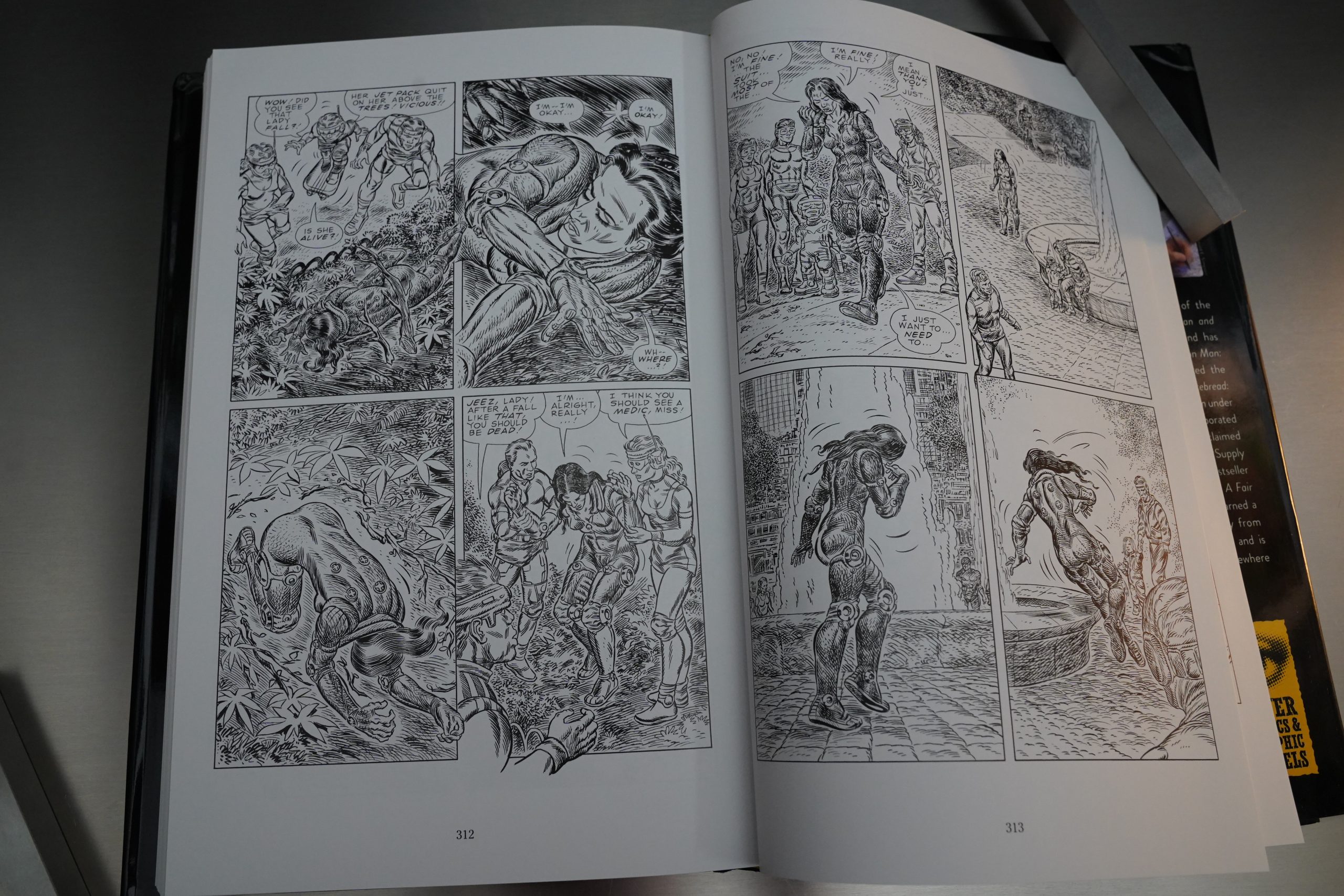

But then, the recap chapter is over, and Simpson can start continue the story, and… it’s a very striking shift from the first chapters. The layouts look totally like a Japanese comics, with full bleed printing, and double page spread panels, and things being generally decompressed.

And that’s how the issue ends.

That seventh chapter was very promising — it had a real mood going on, and a feeling that there’s whole world there, and that the characters were going to be interesting. It’s, like, good? Yeah. It’s good.

With the second issue, it becomes clear that Simpson’s approach to the artwork isn’t quite… settled. The first issue had this ultra sharp rendering, and then here we get a few spreads that look quite influenced by Frank Miller’s Ronin.

And some of the characters look way, way more cartooney than the rest.

And then suddenly we’re get a few pages with organic Moebius lines?

But it’s all good! The storytelling is smooth, the mood’s still there, we’re into the characters, and there’s several plot strands that seem likely to be connected in subsequent issues.

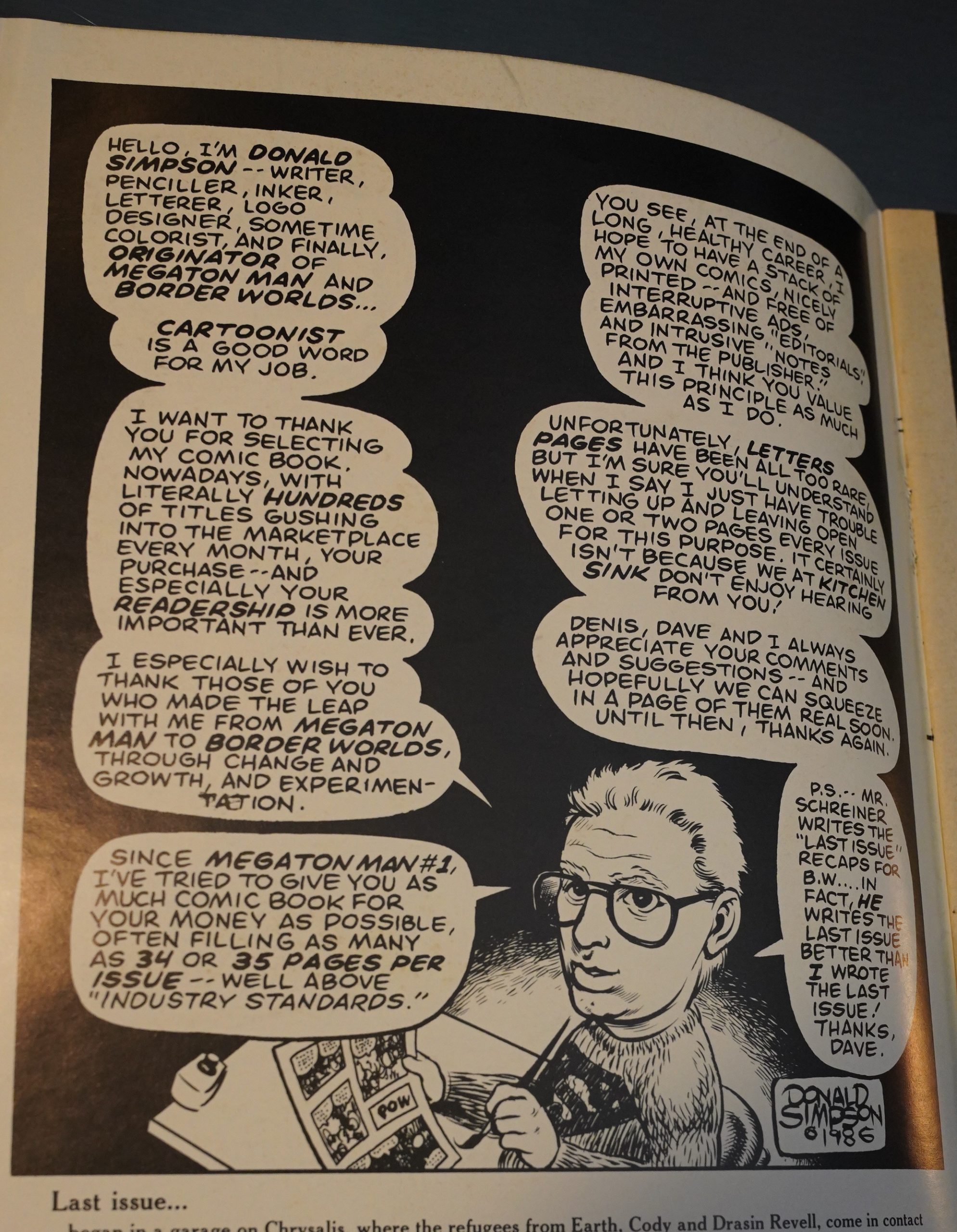

These issues are brisk reads, though, even if there’s 32 or 33 story pages per issue.

So Simpson was probably being bombarded with mail saying “I PAID TWO BUCKS FOR THIS AND IT TOOK ME THREE MINUTES TO READ I”M ANGREE”, so he’s saying “but I’m drawing so much shut up” (I’m paraphrasing). Which is fair.

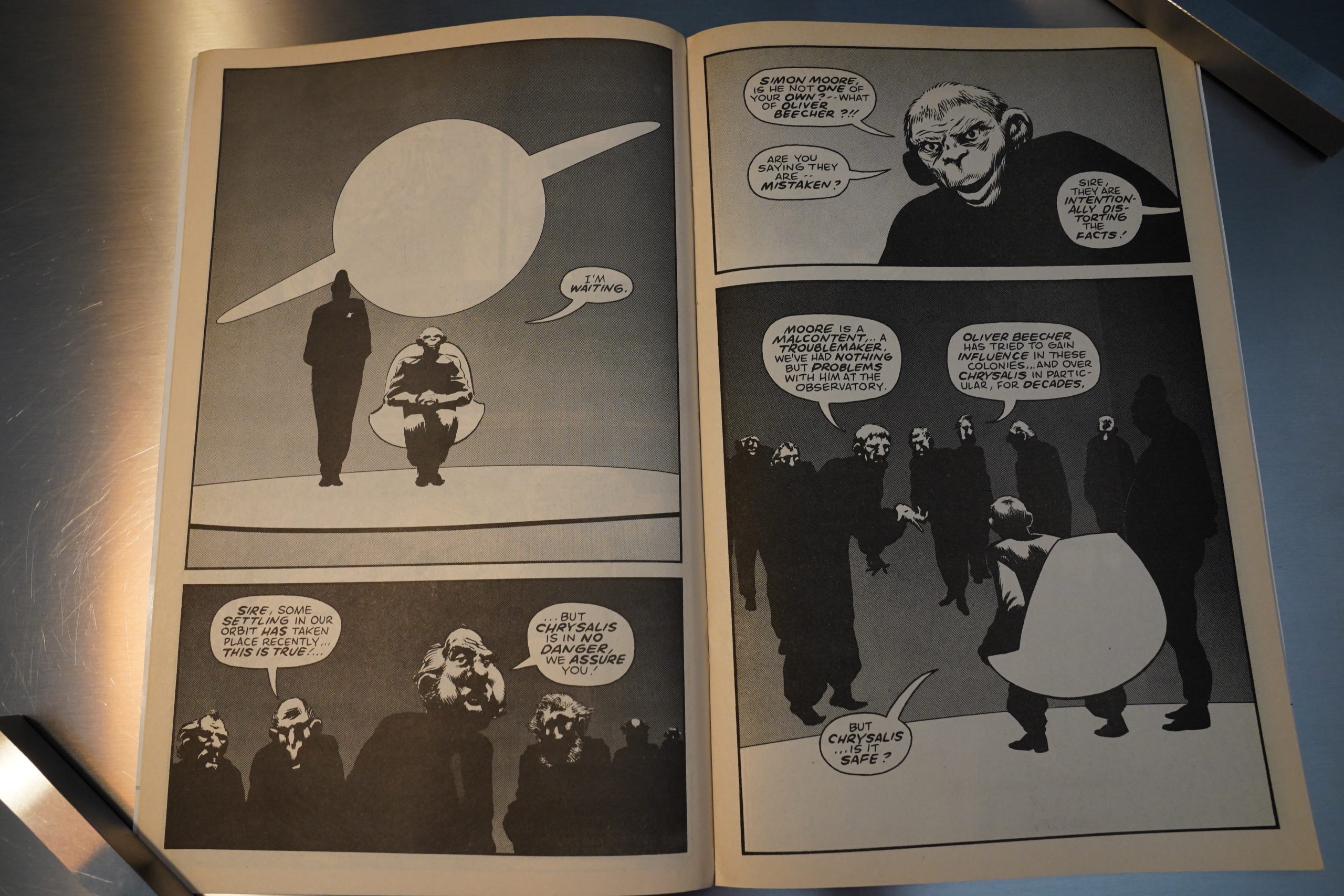

But he seems to capitulate, anyway. Gone are the Japanese-inspired layouts — from here on out, there’s barely a single spread with horizontal panels. But it’s weird — as he’s doing this, and putting in more talking, the story grinds to a halt. We get a lot of talking heads, but no real development of the plotlines.

And the artwork doesn’t feel as exuberant all over, really — it’s more about approaches to filling pages while drawing as little as possible, so there’s entire scenes that are mainly heads floating in oceans of zip-a-tone.

And the layouts get even more traditional.

(Oh, and the bit about living in a space suit? I don’t think we see her in a space suit more than three panels in the entire series.)

Oh, yeah — Kitchen Sink was getting a sort of identity around science fiction/fantasy with artwork in an… Al Williamson? … tradition. These series seemed to be in conversation with each other, somehow — all of them kinda sorta elegiac in tone.

“Corrected Edition”? What’s that about?

Ah:

Pages 4 and 5 are reversed. A corrected edition was subsequently released.

Well, that’s quite extravagant…

The seventh issue sees another dramatic shift in the artwork. Is this Craftint? (It’s paper with two different types of tone present in the paper, and you can use a brush with two different chemicals to bring it out.) It almost always looks like a total mess when printed, and this is certainly isn’t… pretty.

If it’s not Craftint, Simpson’s spent a lot of time cutting zip-a-tone.

Anyway, the seventh and final issue doesn’t resolve anything, but that’s because they didn’t know that that was the final issue at the time. But I think you can tell by the waffling in the storyline and the phoned-in artwork that Simpson had lost interest. Or, if not lost interest, then perhaps he just had to take up other work because circulation had fallen? This was, after all, during the Black and White Bust.

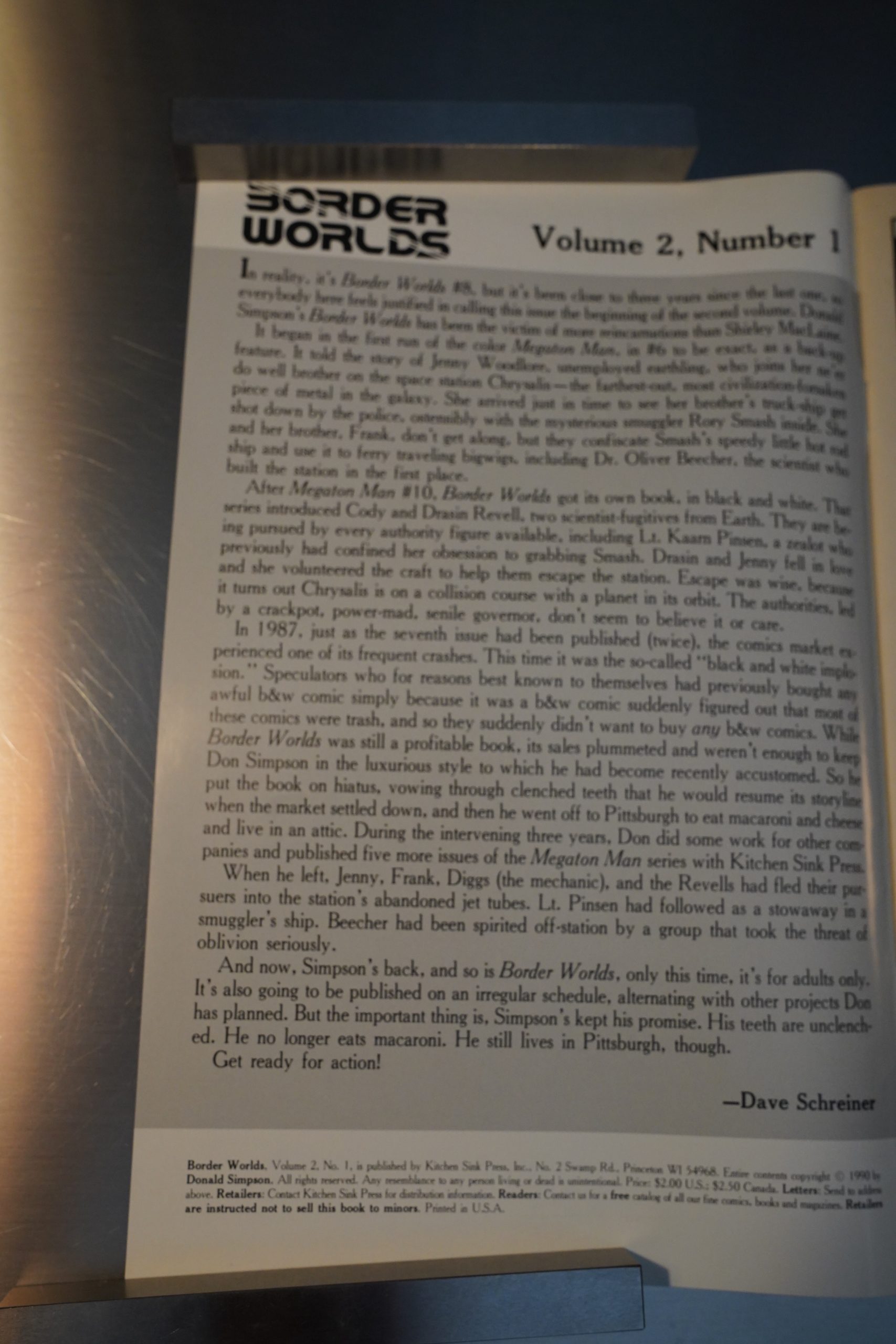

So three years later…

… we get the issue that was going to be Border Worlds #8, apparently. But they’ve restarted the numbering at #1.

And as with Border Worlds #1, it’s not a very good #1 if you want to draw in new readers.

And the layouts have now gone completely traditional, and there’s not much of interest in the artwork.

Oh, yeah, Simpson would start doing porn comics for Fantagraphics shortly afterwards, I think?

In any case, this issue doesn’t wrap up anything, because the series was supposed to continue. But I’m assuming that sales sucked, once again, and Simpson had to abandon the project again.

So that was the state of affairs for a few decades — one of the many “lost” comics of the 80s: Without an ending, you can’t really collect it.

Dover Books to the rescue! Over a very weird couple of years, they got in touch with creators of these “lost” 80s comics series and had them whip up some endings for the things, and they published them as (cheap) hardcover collections. This didn’t last very long, so either they ran out of these sort of books, or they didn’t sell all that well.

Hm… They did more books than I remembered in the 2009-2016 era.

Simpson manages to tie up a number of the plot lines in the additional pages — certainly much better than the new ending to Puma Blues (which really sucked).

It’s an almost kinda satisfying ending?

But as a book, it’s a mess. It shifts between all these different tones and rendering styles, and it doesn’t really cohere. The chapters that work (approx 7 to 10) are kinda special.

Comics Scene Volume #2, page 41:

At the time, though, Simpson

thought Border Worlds could follow

Megaton Man’s sales history, giving

him a second shot at stardom. “It

seemed like a real safe bet,”

says

Simpson, “The black-and-white boom

was just starting. Border Worlds #1

sold about 20,000. After that, it

dropped like a rock.”

Simpson blames a plummeting in-

dependent market for the death of his

darling. “In the early ’80s, everyone

was clamoring for diversity of mate-

rial and more mature stories,” he ex-

plains. “We were just coming off

Elfquest and Star *Reach [two pio-

neering independents]. But DC and

Marvel co-opted all that energy, espe-

cially with The Dark Knight Returnsu

Suddenly, everyone wanted to be like

Frank Miller, and do the definitive

Spider-Man or something.”

Kitchen, in turn, says Simpson’s

180-degree turn from satire to straight

science fiction alienated fans, a mis-

take he says has repeatedly hobbled

Simpson’s series-hopping career (five

Kitchen Sink first issues in 1989 and

1990). “Don has always been very

mercurial,” Kitchen says.

“In my

view, he has lost fans each time he

changed books. He’s more concerned

about his own artistic impulses than

about satisfying readers who are

interested in him. I expected that Don

would have been a superstar by now.

“He also did something that was

market poison: He took Border

Worlds, which was an all-ages book,

and made it X-rated midstream.” The

book lived up to its Mature Readers

tag with nudity in its last two issues,

#6 and #7.

There is yet another possible rea-

son for Border Worlds’ failure: It was

just plain slow going, perhaps the

talkiest SF comic ever. Simpson even

had to scrap an action-promising

cover for #1 as too misleading.

AH: So why have you returned to

Megaton Man ?

SIMPSON: This mini-series started

in January of ’87. I was still working

on Border Worlds then and I wasn’t

sure what format it would take. I was

thinking ofa long story, or a double-

issue, or something like that and

I had no deadline. I was doing it just

as a relief from doing Border Worlds.

The two things are so different that

going from one to the other was a

good break. The only problem of

course is that Border Worlds kept

dropping in sales to the point where

I had to take on freelance work—I did

an issue of the Justice Machine and

inked a Mr. Monster. Then I got roped

into Wastelands at DC. All These

things just tended to take its toll on

Border Worlds in terms of my atten-

tion to it and by the time of issue #7

I just felt that I was being distracted

to the point that I was worried I was

going to hurt the quality of the book.

Actually I think steadily the series

kept getting better. If anything I think

it was getting much stronger and I was

getting deeper into it. That was the

problem: I wanted to be fully

absorbed with it, but out of necessity

I had to juggle different things which

doesn’t make for peace of mind. So

by the time I suspended Border

Worlds everyone told me that by

suspending it I was in effect cancell-

ing it. Of course I had every intention

of returning to it as soon as possible.

I was treating the freelance stuff as

stop-gap measures—stuff to do to get

back on track and,wait for the market

to return.

In the meantime, I was still doing

bits and pieces of the Megaton Man

mini-series and it was growing closer

to being finished.

AH: On Border •Worlds, which you

said you thought was getting better

with every issue, what elements did

you think were improving?

SIMPSON: well, 1 was learning

more about characterization, about

form and pacing … There was a lot

of experimenting with Border Worlds

from the back-up feature in the last

few issues of Megaton Man to the

black-and-white book. I was learning

to draw in black-and-white which is

a lot different from relying on color.

So, I was experimenting with silhouet-

tes, a lot of black… by the 7th issue

Iwas using duoshade/craft-tint which

is probably associated with the

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles more

than anything else. Overall I think I

was getting Border Worlds down.

In the 6th and 7th issues there were

more panels to a page. One of the

complaints I heard a lot was—

especially on the early issues which

had a lot of double-page splashes—it

seemed like when you read an issue,

not a lot had been accomplished. I

think by the later issues things were

beginning to move and pay off.

6. Border Worlds

This stark, dramatic series

seemed almost to have wormed its

way into my consciousness quite

unexpectedly. I had never read a

single installment of the five open-

ing chapters that appeared in the

back of Megaton Man last year.

Donald Simpson’s striking illustra-

tions compelled me to purchase the

first issue when the strip was given

its own book–three issues of which

have appeared to date. Three—but

after only one I was convinced this

‘would be an outstanding series. I

think time has confirmed the validity

of this particular bit of intuition.[…]

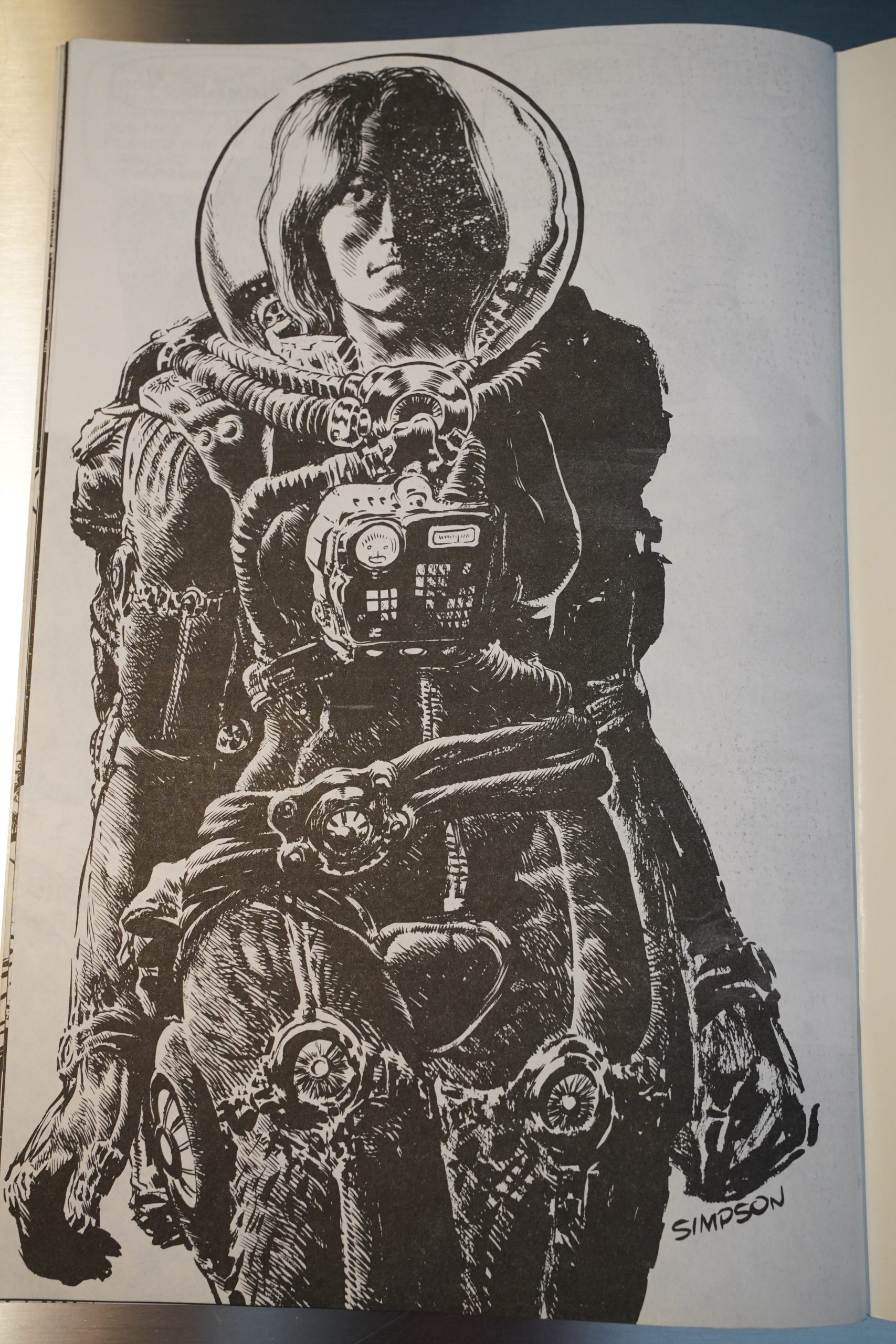

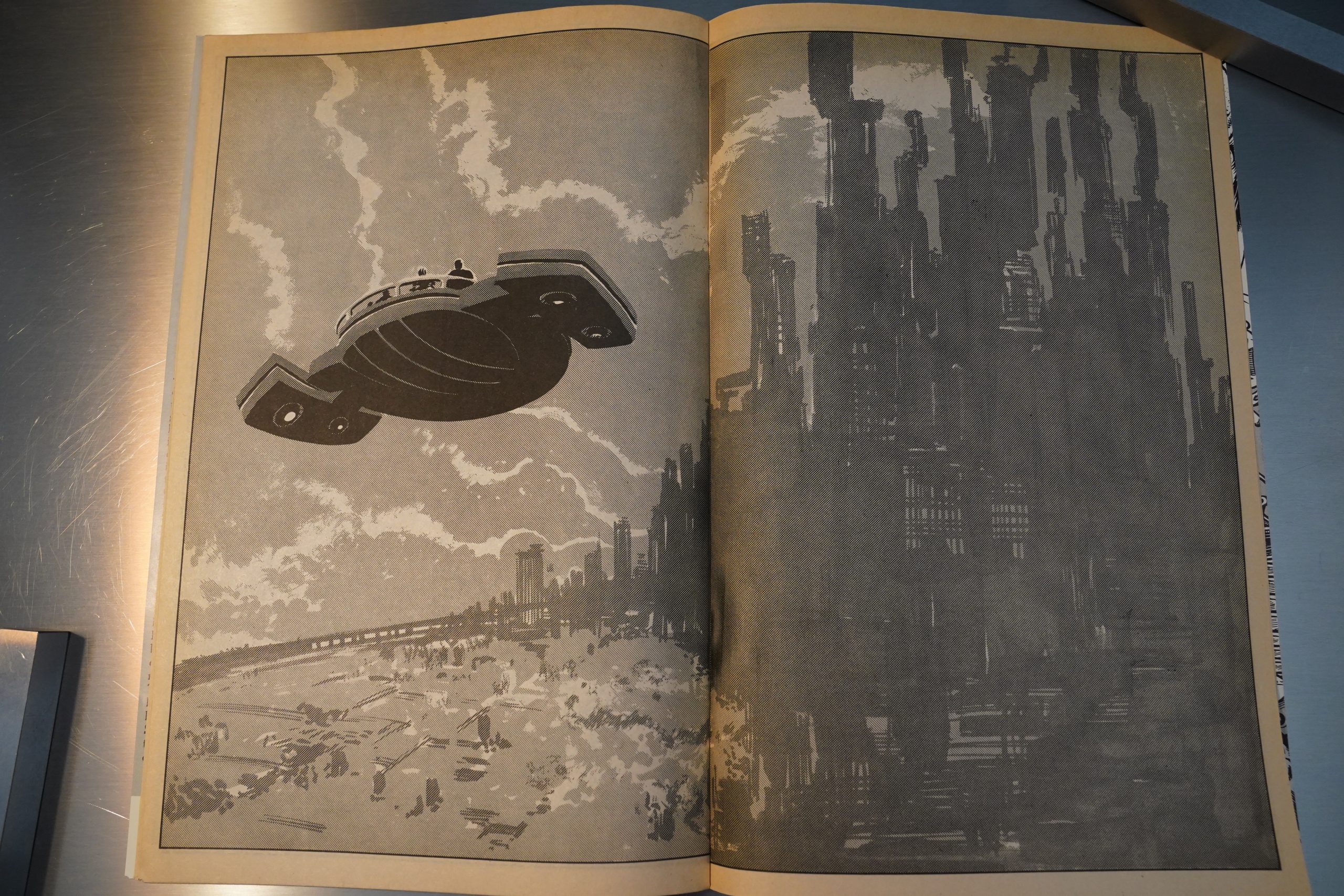

But, perhaps more than any other

book in my Top Ten, it is the sheer

power of the illustrations that car-

ries this title awe,y from the common

herd.

Most often, comic book science

fiction seems wedded to Star

Wtzrs–all gloss and glitter. The only

glitter found here is the occasional

ray of light reflecting from the sur-

face of a besmudged helmet. Simp-

son’s space ships don’t look like

special effects—but like blocks of

fully functional machinery. Space

suits are born of practicality. not

designed by Dior. This is a world

of juxtapx)sed light and shadow–

with the shadow seeming always to

hold the advantage. It is a tough

world, beaten down by the harshness

of reality.

The Comics Journal #117, page 61:

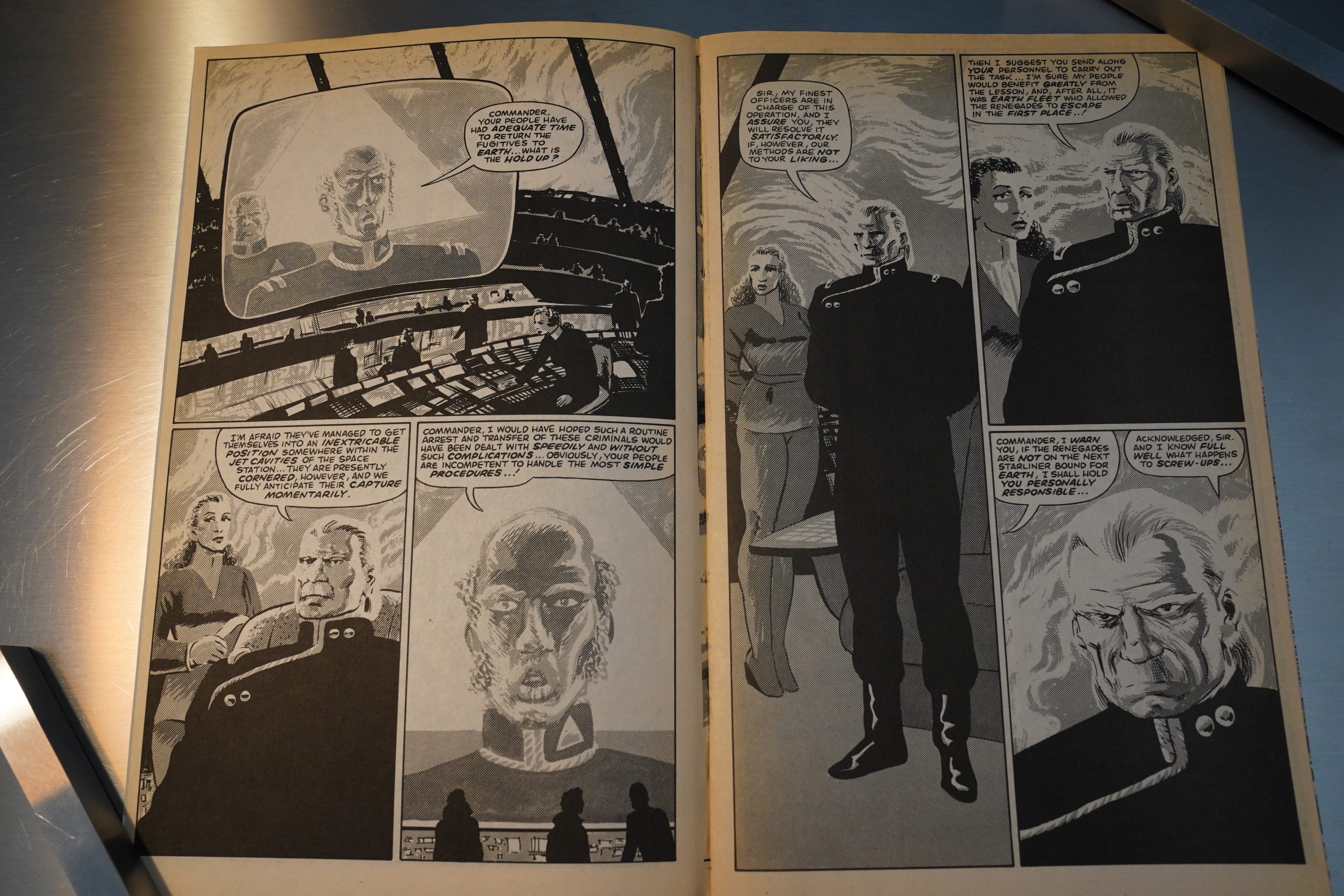

A chief virture of Donald Simpson’s

Border Worlds is that it focuses on the

thoughts and feeliws of Jenny Woodlore,

a novice from Earth who begins a space

shuttle operation on Chrysalis, a magnifi-

cent domed space station in the Arcameon

star system. Throughout the series, Simp•

son anchors his epic tale in human sensi-

bility by intermittently pulling us back to

Jenny’s point of view. For example, the

first issue commences with a monologue

in which Jenny laments the relentless

routine and monotony Of her work. The

drab. banal way Jenny talks about her life

may seem off-putting at first (and Simp-

son uses uninvitingly dense blocks of text

to get things off to a slow start), but Simp-

son wins you over. The first issue sets the

right tone of vaguely disillusioned melan-

choly that permeates Jenny’s life, and

when Jenny relates an instance of sexual

fantasy, that led to “a fleeting moment

of satisfaction,” Simpson has successfully

captured the sense of a human being’s

private longings and disappointments.

Like Alien Fire, Border Worlds aspires

to the texture and complexity of serious

science fiction in comic book form. In this

effort, Simpson is generally successful,

and the series should appeal to fans of

seriously-intended genre work. The ingre-

dients are perhaps too familiar—one plot

line has to do with efforts to prevent the

imminent destruction of Chrysalis as it

drifts out Of orbit, another involves a

fuÉtive brother and sister who are sought

by authorities because they possess the

knowledge necessary to create a “black

hole bomb” —and you sometimes wish

Simpson would get on with it. The

emphasis on mood and atmosphere feels

like dawdling, but the storytelling is never

less than intelligent.

Simpson has settled on an unusual

visual approach for Border Worlds. He

rarely draws more than three panels ner

page, and he occasionally dedicates an

entire page to a single panel. As part of

this scheme, the art has been reproduced

on a scale that is larger than we’re accus-

tomed to seeing in comics—that is, we

see panels that in most mainstream comics

would be reproduced at half the scale

Simpson employs. Though I admire

Simpson’s aspirations, I was put off by

the self-conscious, arty expansiveness of

the first two issues—Simpson’s renderings

of the human face and form has a cer-

tain caricatural quality that is less appeal-

ing than it might be, and a bit more

aesthetic distance seems called for—but

I also appreciate that Simpson wants you

to see these image with absolute clarity.

(Simpson appears to have been influenced

by the freedom of Japanese comics.)

Bruce Canwell writes in Amazing Heroes #181, page 86:

BORDER WORLDS:

MAROONED #1Around here, Sunspot Comics is the

“hot” place to shop, thanks to its

manager, Bing Baxterbook. Bing may

talk like a dockwalloper, but he knows

his comics: three years before DC’s

Crisis he was predicting that Wally

West would take (wer as the Flash, and

he pushed for Hawkeye to lead an

Avengers lineup that was remarkably

similar to what became the original

West Coast team. I don’t agree with

all of Bing’s opinions, but when he

talks, I listen.

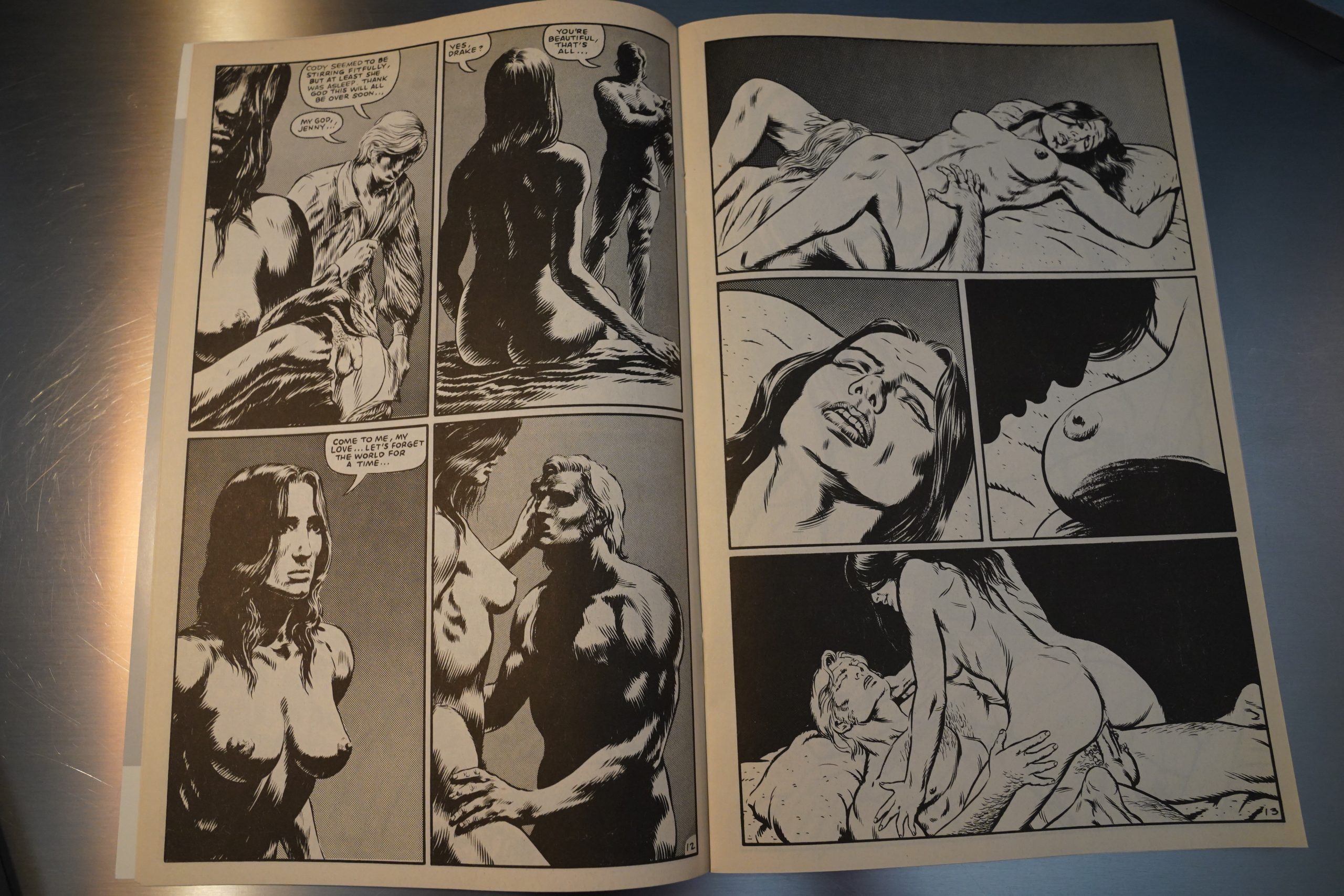

Case in point: Bing looked at my

copy of Border Worlds: Marooned #1

and grunted, “Wotta disappointment!”

I was flabbergasted, “Wait a minute.

This comic’s by Don Simpson, right?

The guy you practically lionized for

his work on Megaton Man, Waste-

land, and Alan Moore’s “Pictopia?”

How can it be a bomb?”

“I’ll level with ya,” Bing said.

Making sure no minors were about,

he opened the comic to page 12. “It’s

this sex scene that bothers me.”

I examined the pages in question

and shrugged. “Looks like an honest,

natural depiction of lwemaking to me.

86

It’s explicit, yeah, but it’s tastefully

executed.”

“It’s tasteful, awright—is it neces-

sary, though? I don’t need to see

penetration t’ figger out that two

people are makin’ it, not if the creator

is doing his job. It’s like Simpson

tossed this scene in just because he

wanted to, not because it was the best

way to convey what was happening.

To my eye, that’s gratuitous, that’s

what it is.”

“But it says ‘Adults Only’ right on

the cover.”

“Well, when I say, ‘This comics for

adults,’ I like it to be ’cause the plot,

characterizations, and themes are

more subtle than the usual super-doop

punch-’em-ups, not ’cause there’s a

buncha writhing, sweaty bodies

inside.”

I understand Bing’s point, but my

problems with Border Worlds is less

with its sexual content than with its

cold, claustrophobic feel and perva-

Sive sense of hopelessness. It’s all

sophisticated and well-clone—which is

a tribute to Simpson’s skills as a

cartoonist—but it’s not exactly an

uplifting reading experience.

The bottom line is Border Worlds

is an ambitious but flawed experiment

from an extremely talented writer-

This is the eighty-fourth post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.

Pingback: facebook.com