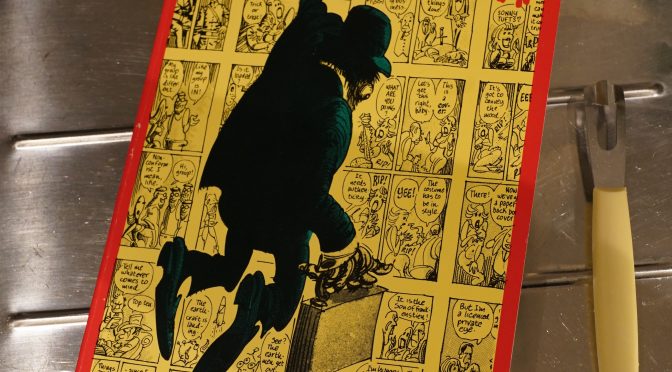

Harvey Kurtzman’s Jungle Book (1986) by Harvey Kurtzman

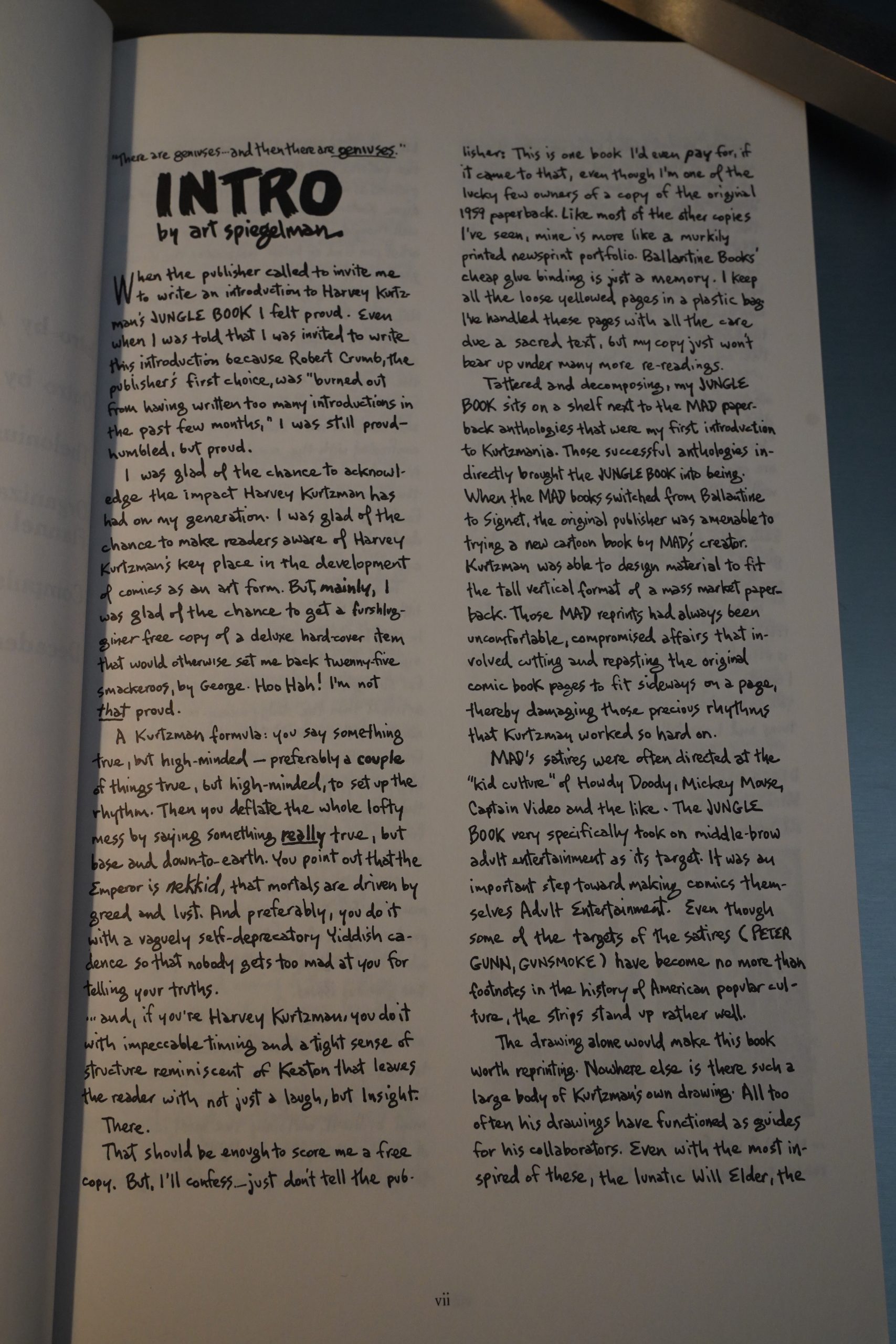

As Art Spiegelman explains in the introduction, this book was originally published in 1959 by Ballantines as a pocket book — so about half the size of this book and on normal paperback stock.

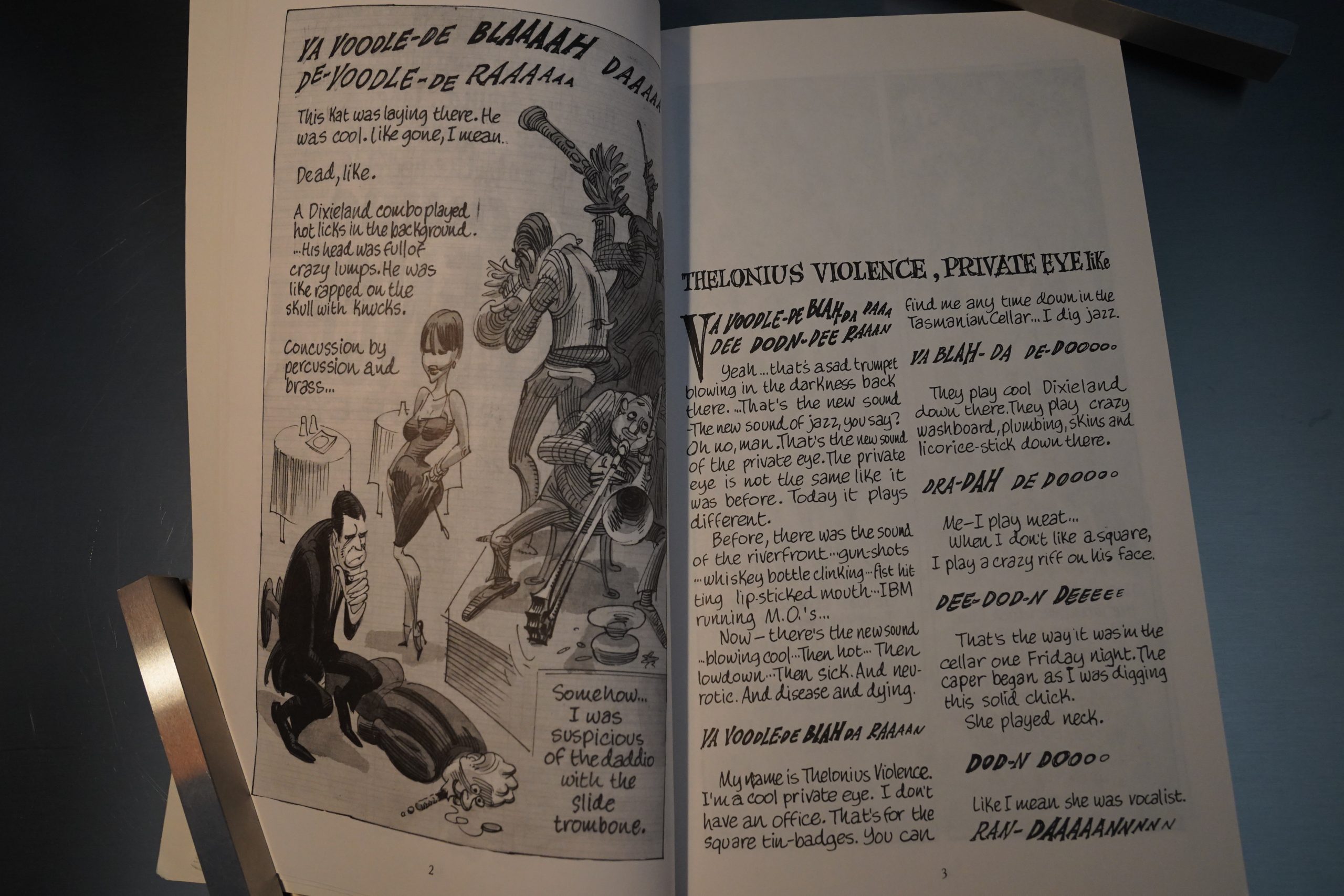

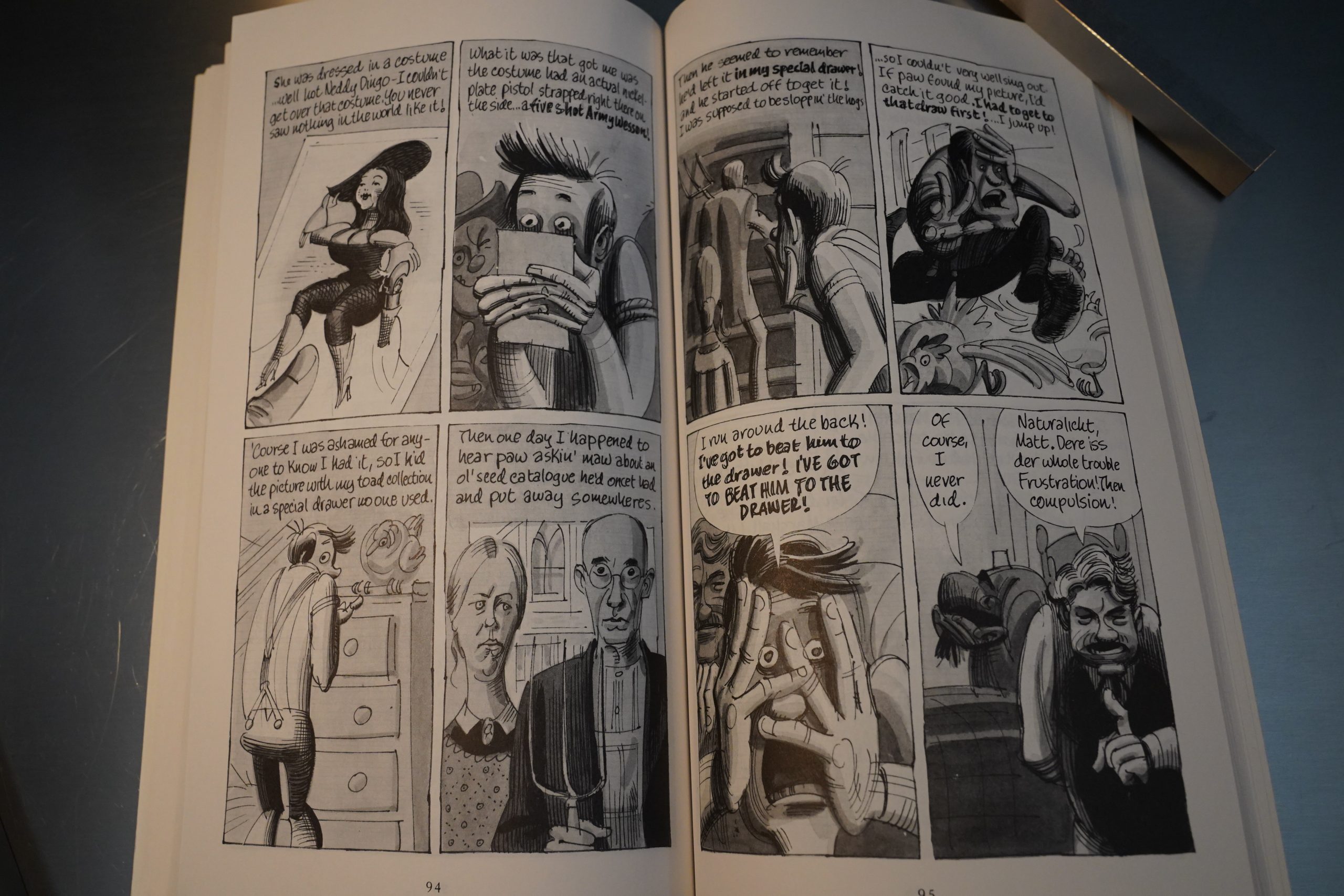

And Kurtzman drew the thing on blue-lined paper that was supposed to not be picked up by the repro camera… but it was, giving the entire thing a rather messy look.

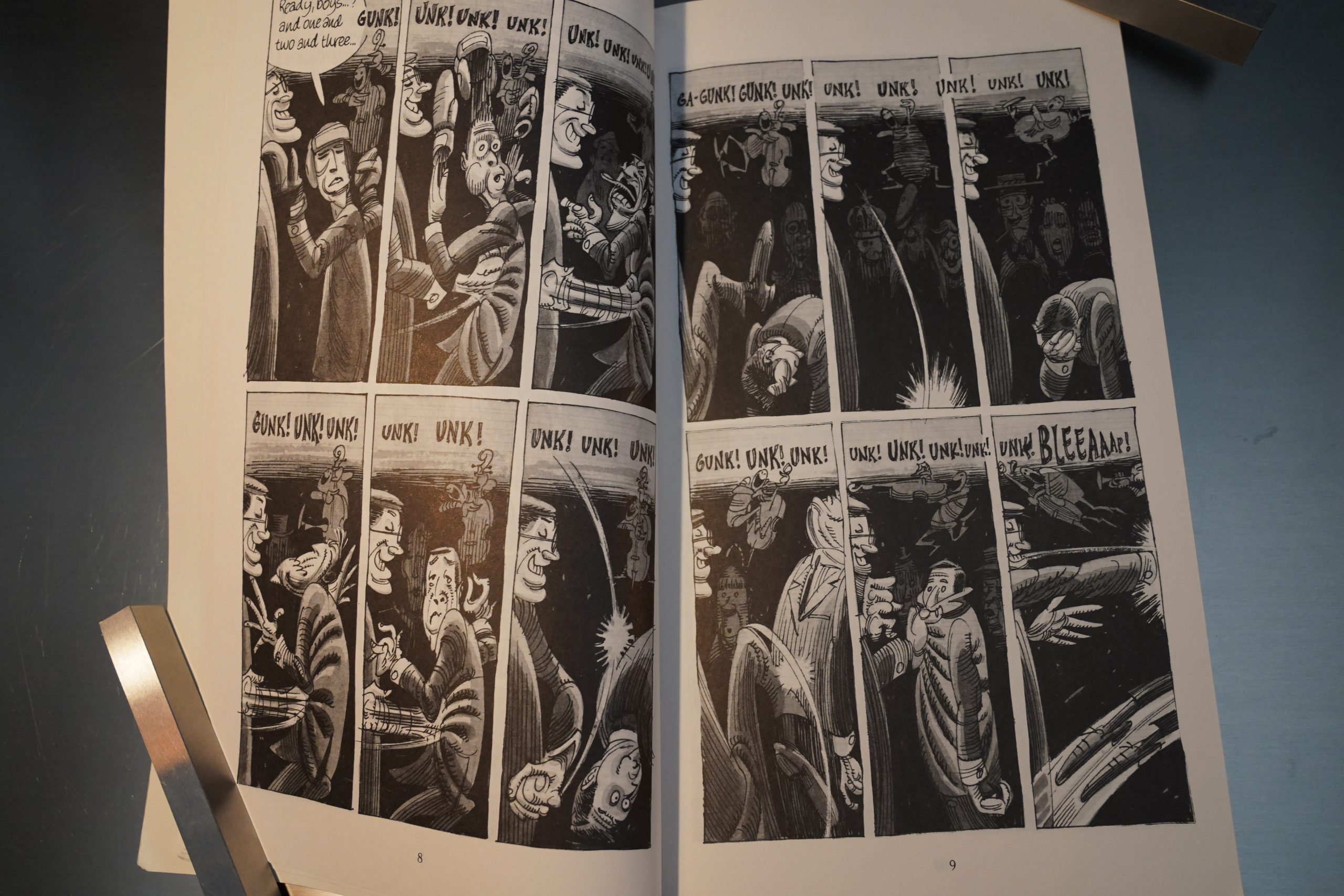

This is, of course, another book of Kurtzman-style parodies (and satires). The first story is a parody of the Peter Gunn TV series, which I’ve never seen, so I have absolutely no idea whether this is on point or not. I’m pretty sure it’s not actually that funny, though.

However, the artwork sure is nice.

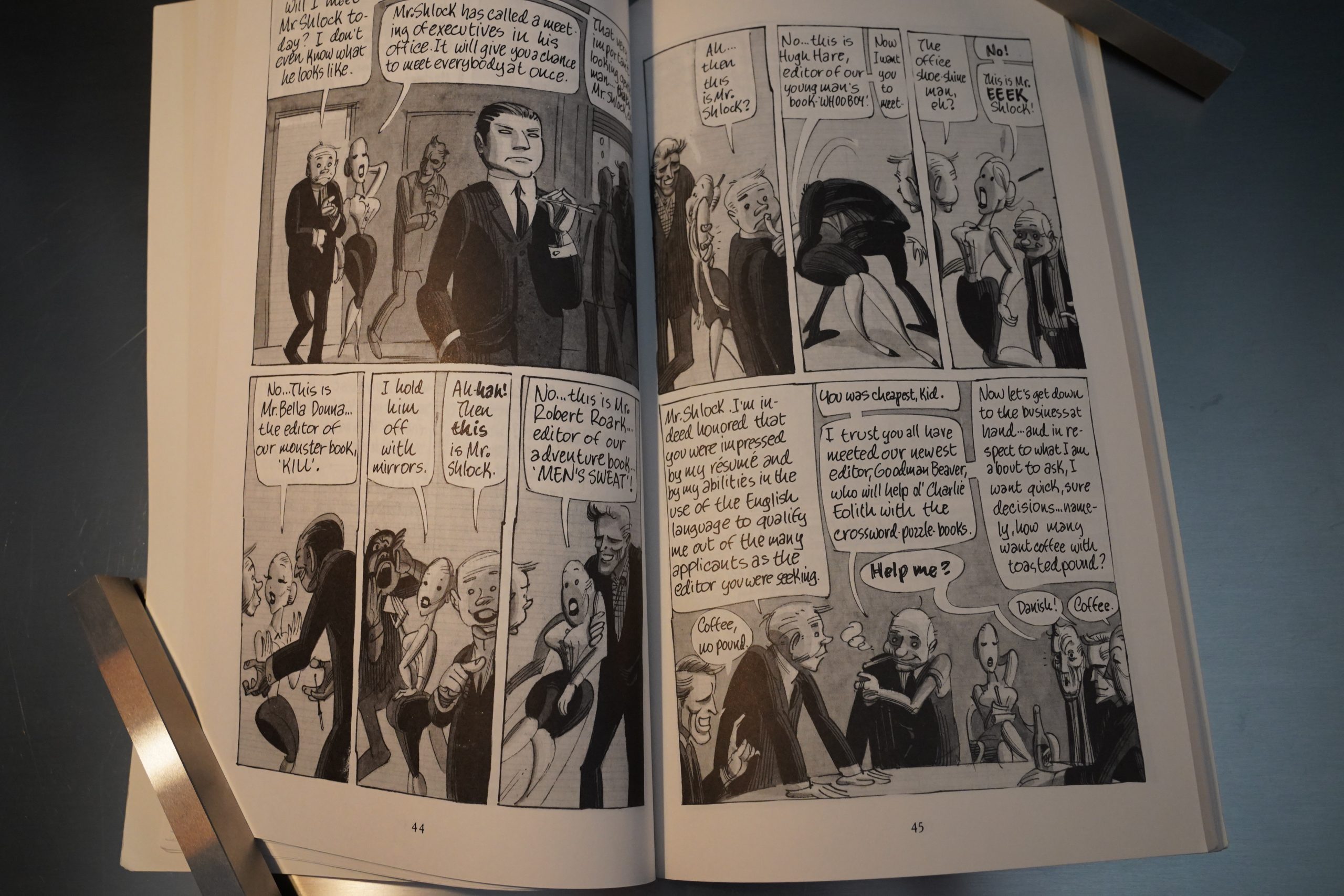

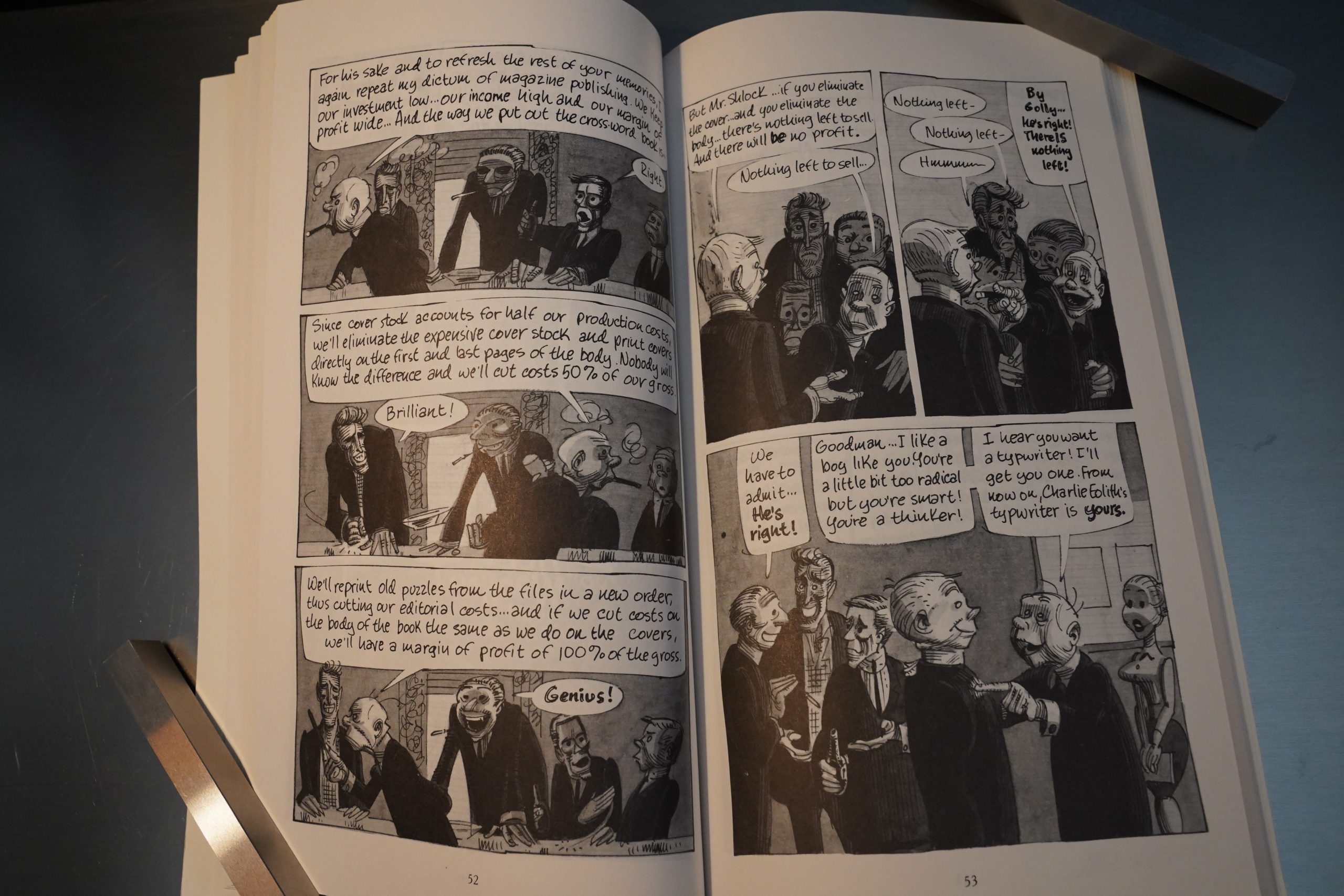

The second story is much more successful — it’s a poisonous look at the magazine publishing history, so here Kurtzman gets to vent on his own behalf.

It turns out that publishers are venal, petty creatures. Who knew?

The cowboy parody has more gags, and this thing, where a psychologist teases out why the sheriff feels the need to have shootouts where he can see whether he can draw the gun faster than anybody else… it’s pretty ingenious.

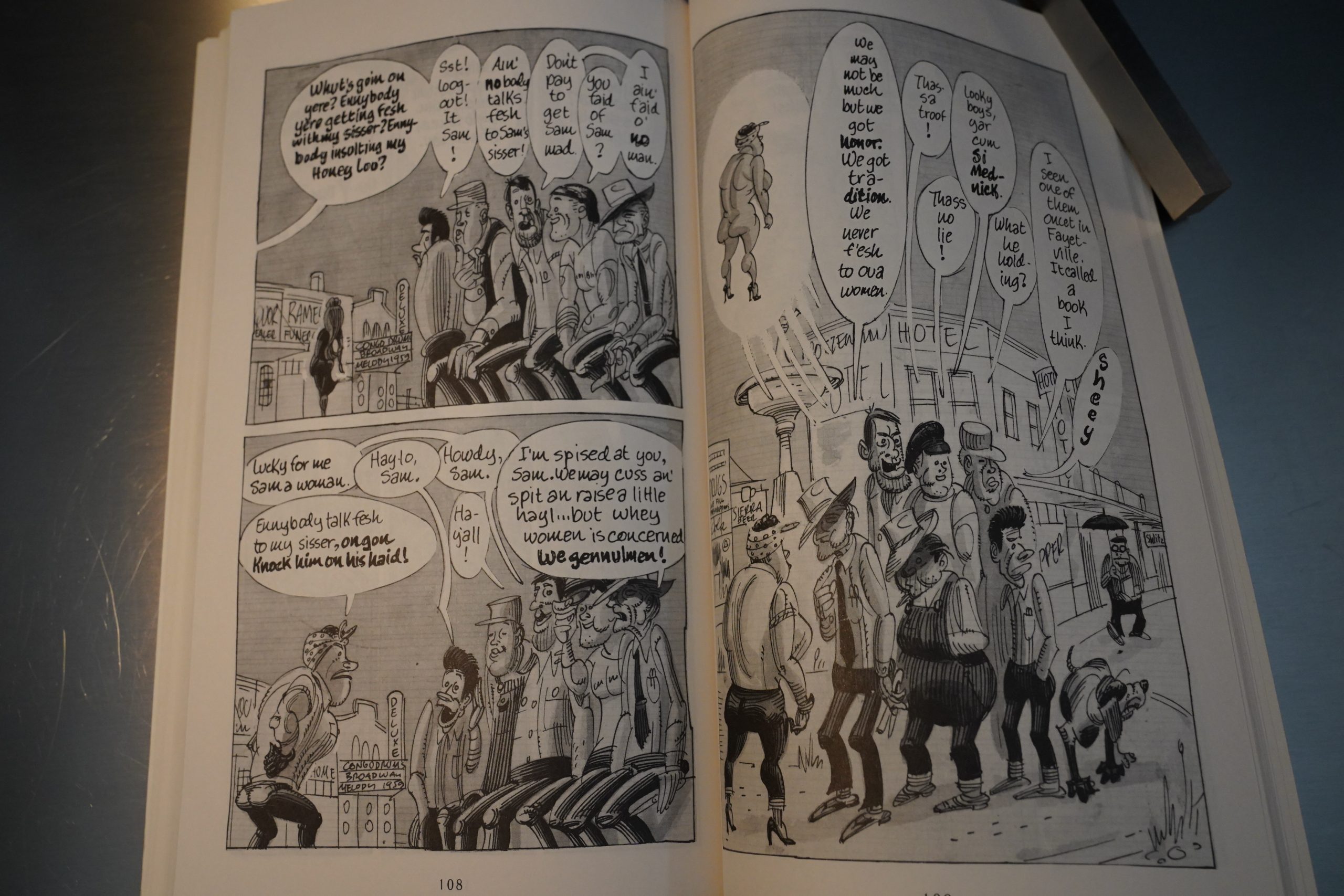

Finally, Kurtzman takes a look at Texas, and determines that Texans are all morons. It seems pretty accurate and is drawn from his time there.

The book reads well, overall — it’s fun to look at Kurtzman’s characters and line work. However, most of the gags are pretty weak, but I can see myself thinking it was pretty clever when I was, like 14.

Dale Luciano writes in The Comics Journal #117, page 51:

Three remarkable new publications, each

preserving significant work from an

acknowledged comics master for posterity,

have appeared from Kitchen Sink Press

during the past six months. Each is a

cultural treasure, and Kitchen Sink merits

praise for investing the time, effort, and

expense to make available what are, I sus-

pect, only marginally profitable projects.

The first is a hardcover reprint edition

Of Harvey Kurtzman’s Jungle Book.

Jungle Book has historical significance as

the fißt mass-market paperback to consist

of entirely original comic material. (Bal•

lantine Books commissioned the book in

1959 as competition for the popular line

of MAD paperback reprints.) Mostly, it

is the stunning show of a gifted satirist—

perhaps the most subservise talent ever

to have worked in comics—performing at

the peak of his skills.[…]

The book’s second piece, “The Organ-

ization Man,” is a genuine classic, repre-

senting a certain mode of satire that

Kurtzman pioneered during the 1950s. It

is a venomously funny black satire on the

corrupting effects of greed in the New

York publishing world. (The title derives

from three influential books written about

the business world during the 1950s, so

the story has its origins in parody as well;

Man in the Grey Flannel Suit and Exec-

ulive Suite were hugely popular film

adaptations of best-selling novels.) Kurtz-

man kicks off the story by having Good-

man Beaver arrive for his first day on the

job at “Shlock Publications.” During the

corpus, Kurtzman traces the perversion

Of Beaver’s innocence. Not only is the

story ruthlessly funny, it is a kind of

autobiographical document attesting to

the surreal excesses Of the publishing

industry as Kurtzman experienced them.

(Early in his career, Kurtzman edited

paperback crossword puzzle editions, as

Goodman Beaver does in the story.) Al-

though this kind of satire has been wide-

ly imitated since the ’50s, “The Organi-

zation Man” holds up beautifully. It has

real bite as an indictment of the exploi-

tative mentality Of those who produce our

mass culture[…]

And, as Art Spiegelman correctly

points out in his introduction, the words

also have a wonderful comic rhythm

unique to Kurtzman. They form an in-

tegral part Of the visual progression.

The second distinctive Kurtzman qual-

ity is the wonderfully loose, fluid sketch-

iness that imparts such an immediate

sence of the artist’s absolute immersion

in the act of cartooning.

It was #26 on the Journals Best 100 Comics of all time in The Comics Journal #210, page 75:

At 140 brilliant pages, theJungle

Book is certainly Kurtzman’s most

substantial graphic achievement.

The vigor and immediacy of the

brushwork, the bold use of tones,

the hypnotic pattern Of sustained

and broken visual rhythms from

panel to panel and page to page,

make it one of the most formally

inventive comic books ever pub-

lished. And Kurtzman’s mordant

wit, freed from the constraint of

shorter magazine pieces, would

never again display as pitiless a bite.

That last Frontline Combat story,

a meditation on fate, Was called

“The Big ‘If.” Harvey Kurtzman’s

Jungle Book provides the biggest “if’

the romantic travails ofits namesake

lead. The strip later became a kind of

adventure-comedy, as Tubbs, and

soon enough, too-similar pal Gozy

Gallup, practiced hijinks and farcical

comedy in a number Of locations

across the world. Things finally fell

into place with the arrival ofsoldier

Of fortune (in typical Crane

fashion, he made his debut by break-

ing down a door). With Easy

providing the muscle and a sense Of

in comics’ history: What if it had

been a success? What if Kurtzman,

instead of being forced to leapfrog

from more failed anthologies to the

compromised Little Annie Fanny to

teaching and illustration jobs, had

been able to recreate himself as a

one-man satirical storyteller — writ-

ing and drawing for magazines and

books? What ifhe had succeeded in

carving a niche in the mainstream

publishing world, into which the

whole next generation of cartoon-

isb could have poured — short

Story writers, essayisß, and novelists

who just happened to work in the

comics form?

Harvey Kurtzman’s Jungle

Book remains one Of the artform’s

most stunning successes, and one

of the field’s most heartbreaking

failures.

I think that’s Kim Thompson writing…

Kurtzman also had the #64 and #63 spots in the list (with Goodman Beaver and Hey! Look, and probably more). That’s a … list of its time, eh?

The book has been reprinted by Dark Horse:

I’d read this in the Ballantine paperback, muddy art and all, but the material looks much better here and the introductory material helps put it in the context of Kurtzman’s career. Unfortunately, I’m inclined to agree with Crumb’s assessment in the the afterward/interview that closes the volume. Kurtzman isn’t very funny here and the material feels considerably less sharp than his work for Mad and Trump. There is an air of weary desperation about some of it and time has rendered even the edgy bits a little pale.

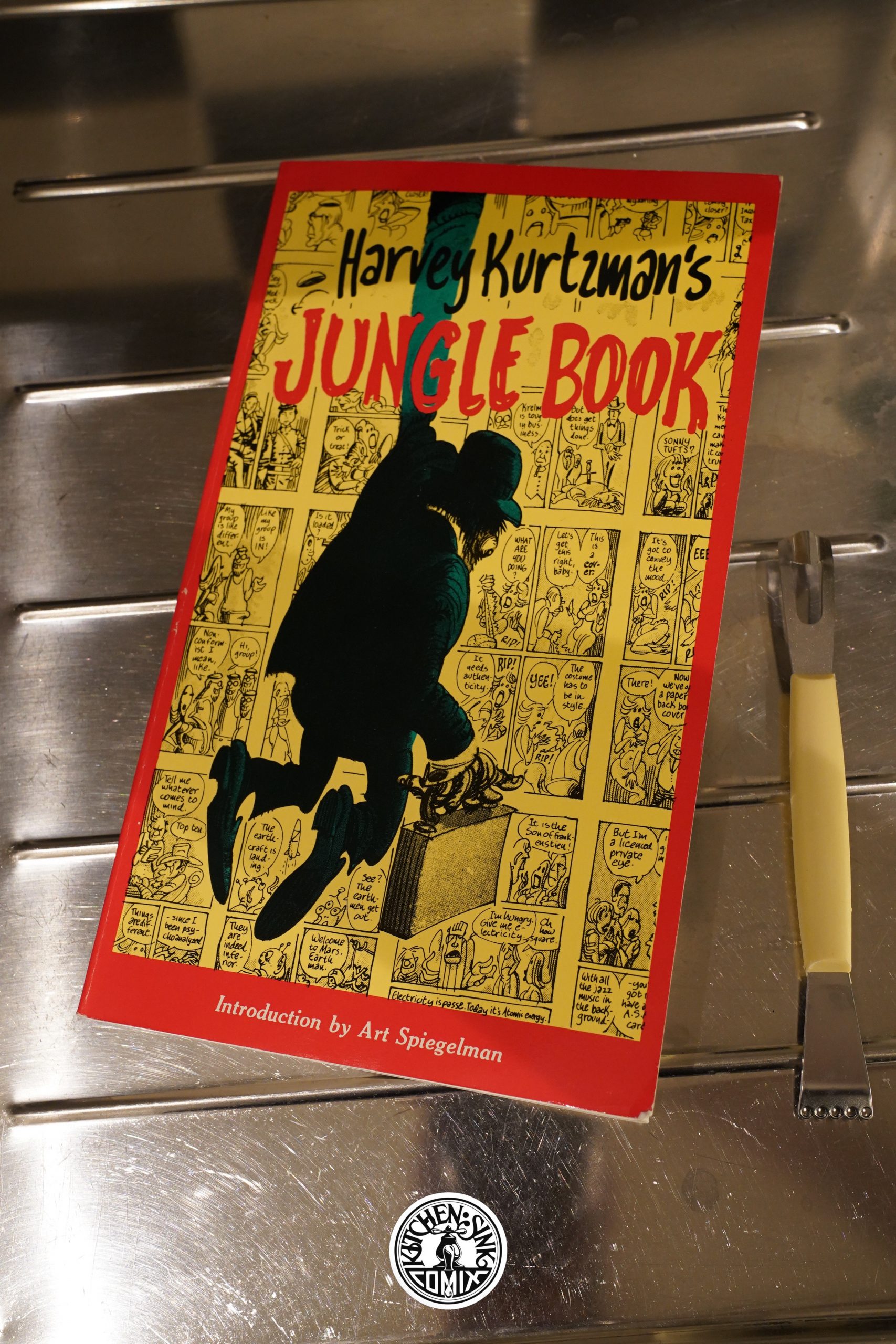

Spiegelman says in his introduction to this edition that he was only offered the job because Crumb turned it down. But they got Crumb to do the introduction to a later edition. Heh heh.

Most people seem kinda unimpressed but don’t want to say so:

And in the end I’ll say, you should read it. Or something by Kurtzman. He was an important figure in American comic, and has influenced countless creators. Many of whom have gone on to call him a genius. He was a visionary and something quite rare: a truly funny cartoonist.

Kurtzman has a very readable visual style, combined with an excellent ear for dialogue. But these strips feel a little throwaway, and, indeed, were originally published as a small pulpy paperback – the posh hardback edition feels like it’s trying too hard. Still, it’s a fun and clever read.

This is the eighty-sixth post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.