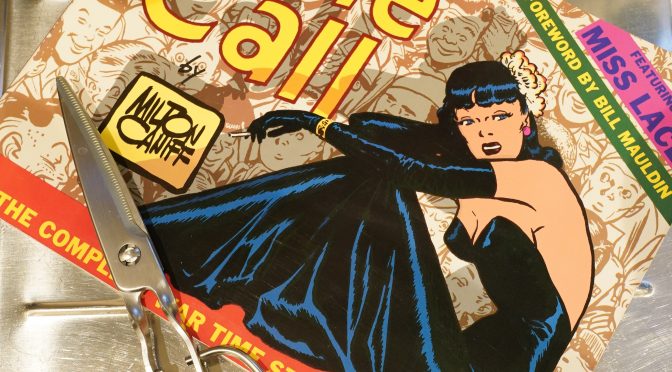

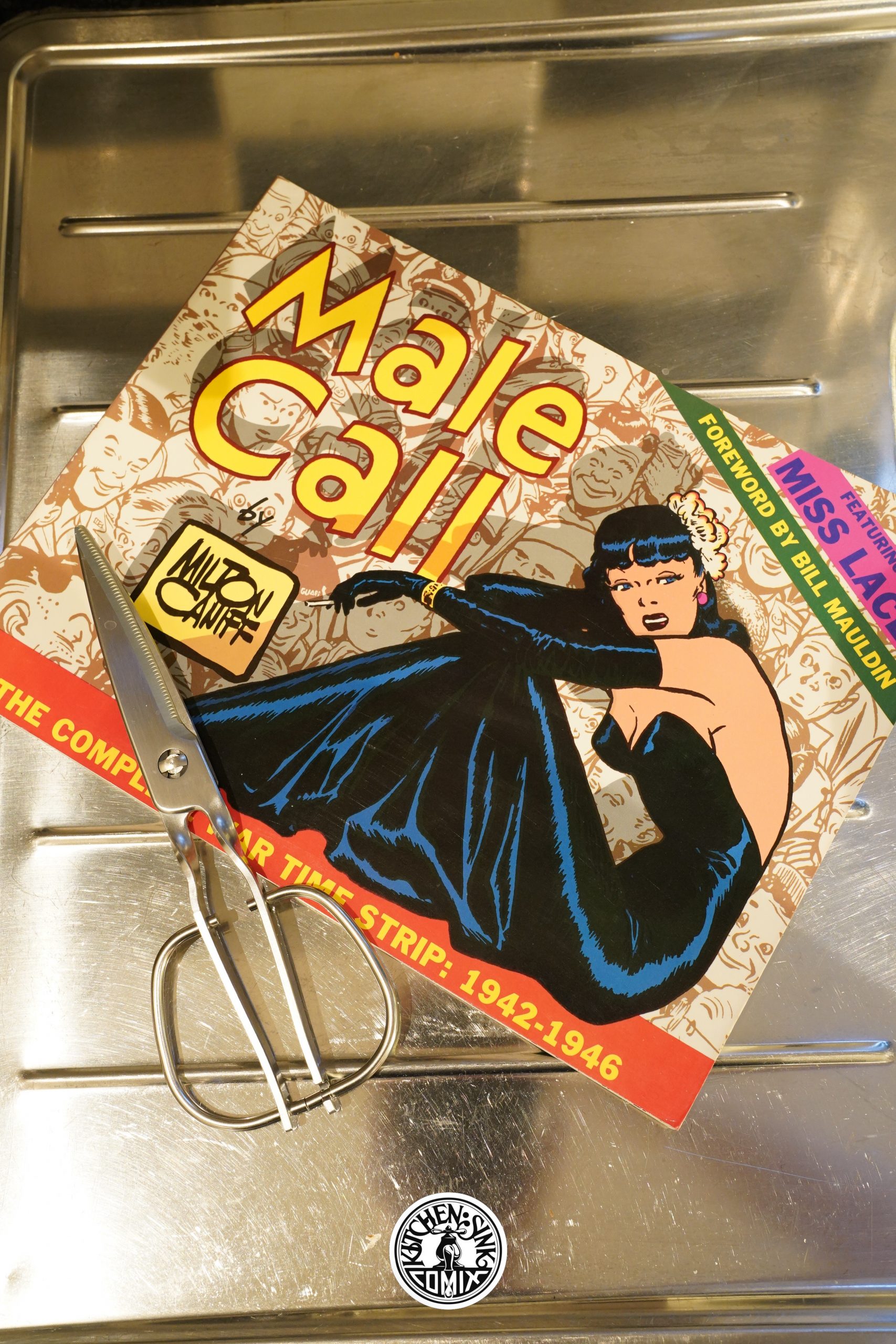

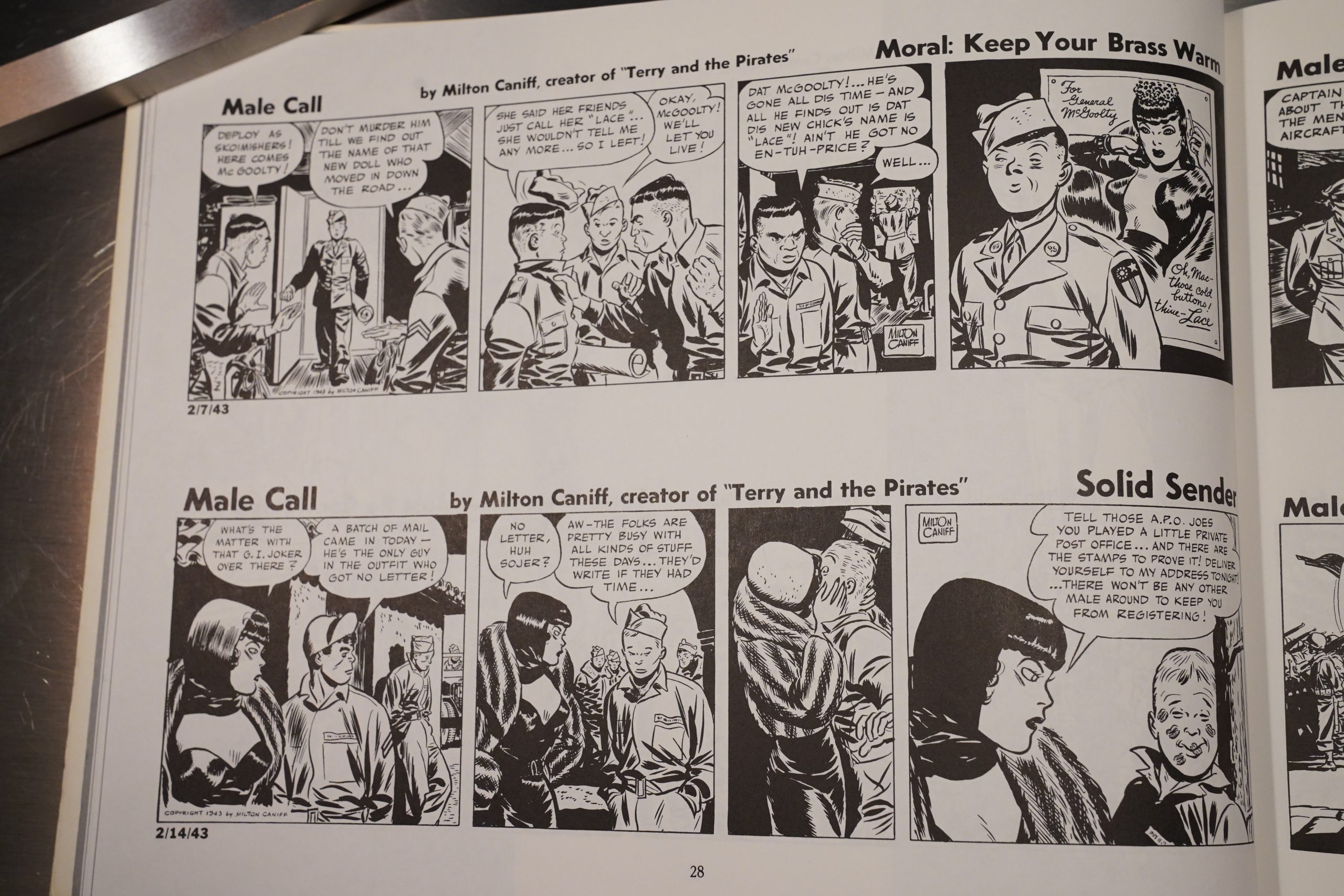

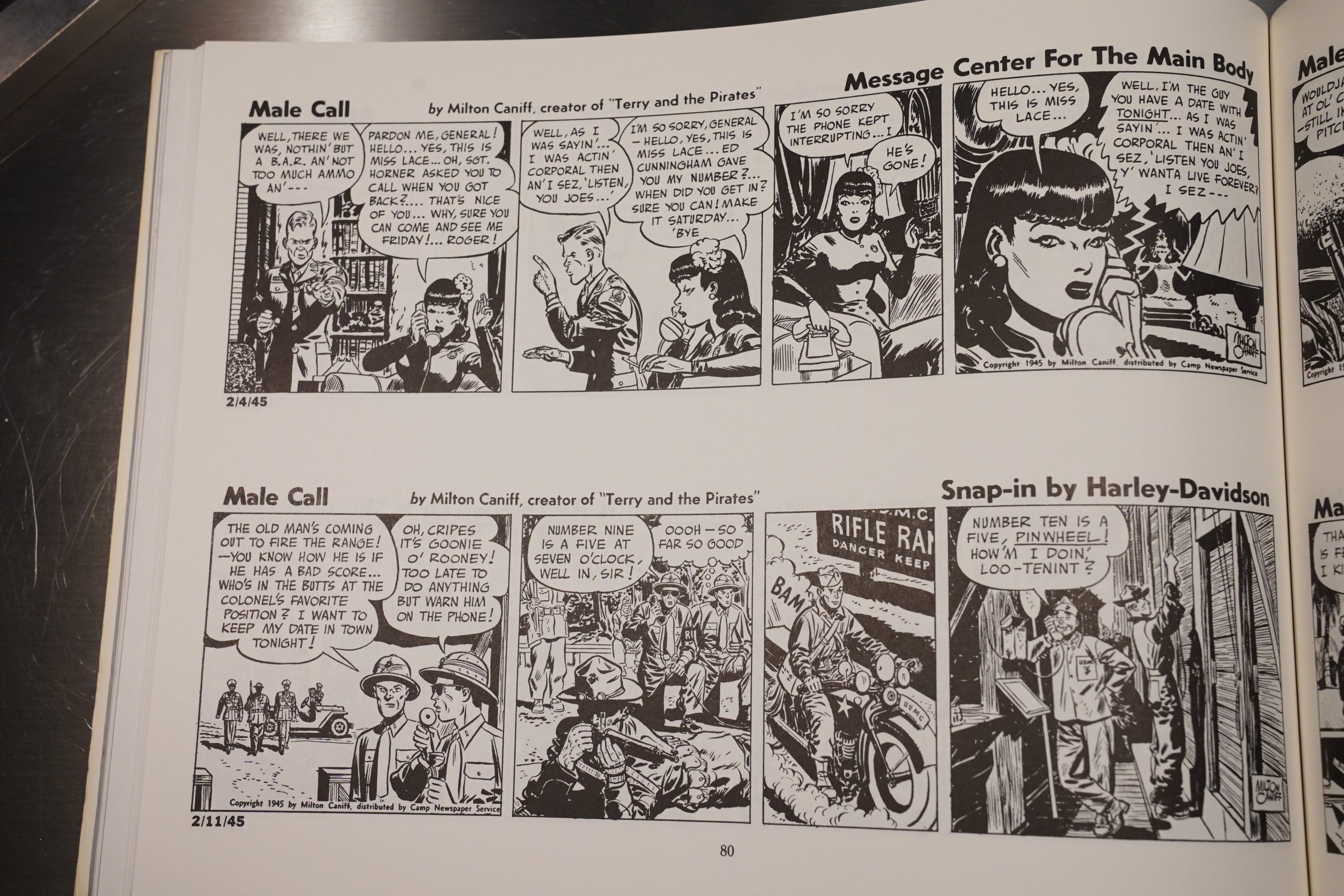

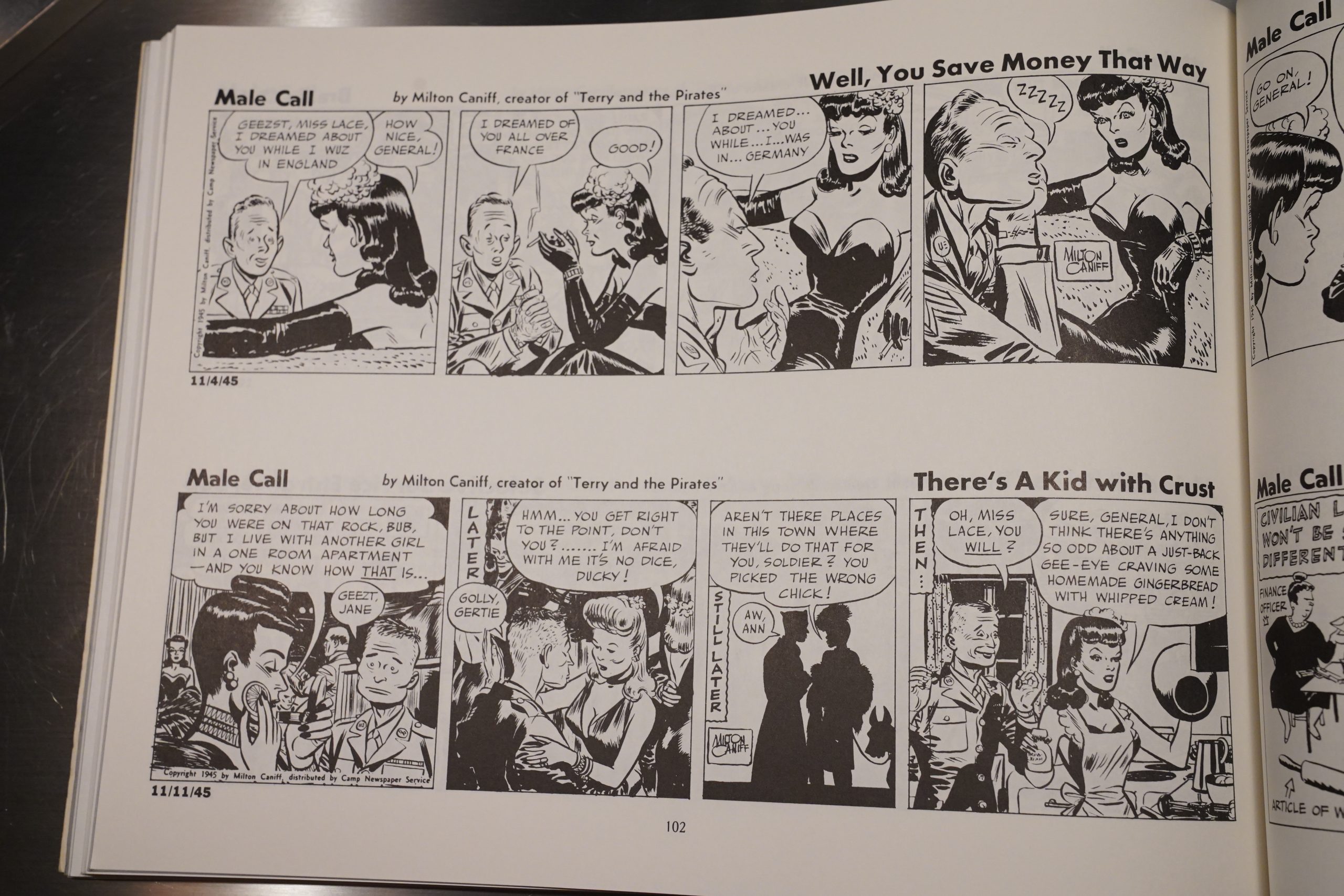

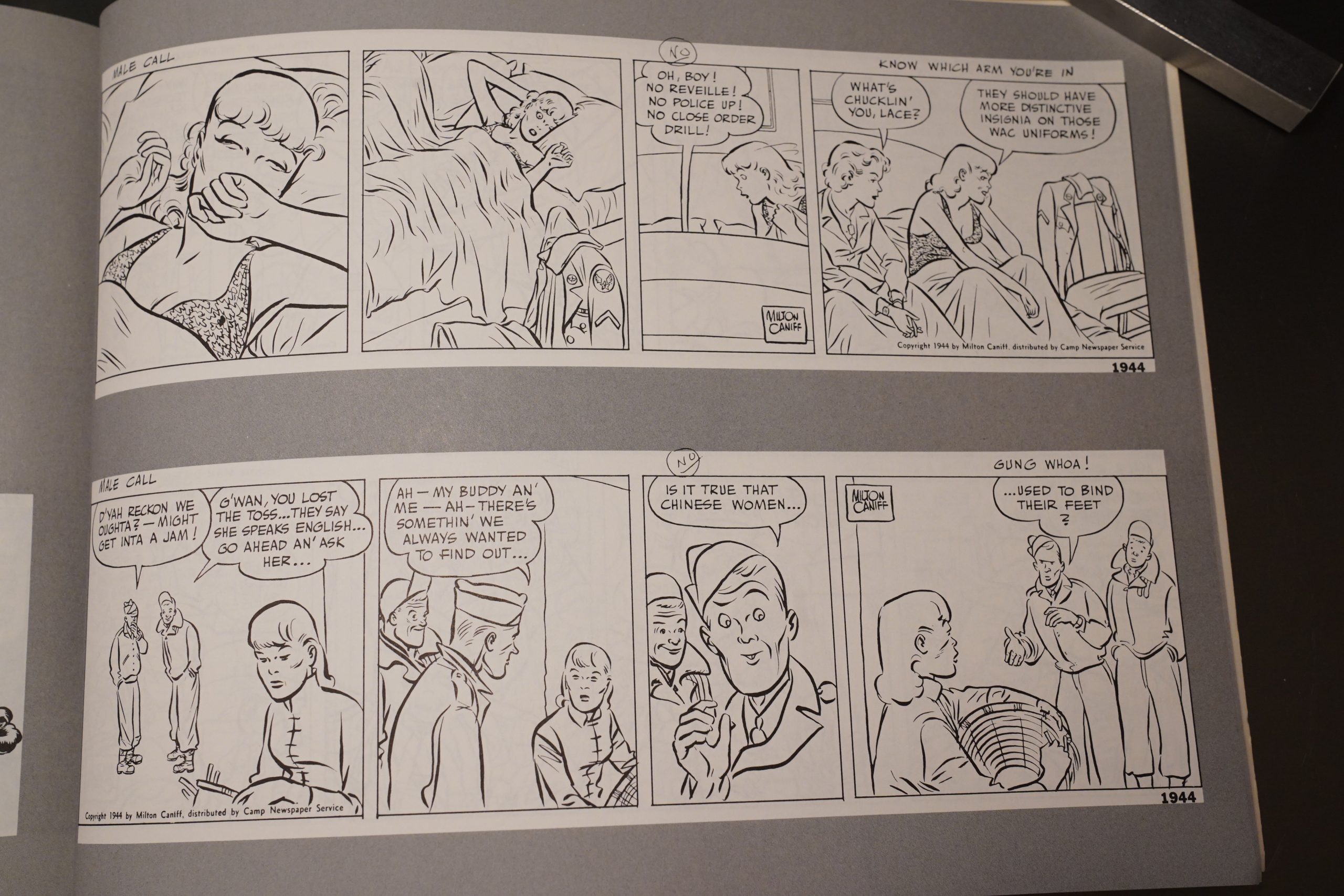

Male Call (1987) by Milton Caniff

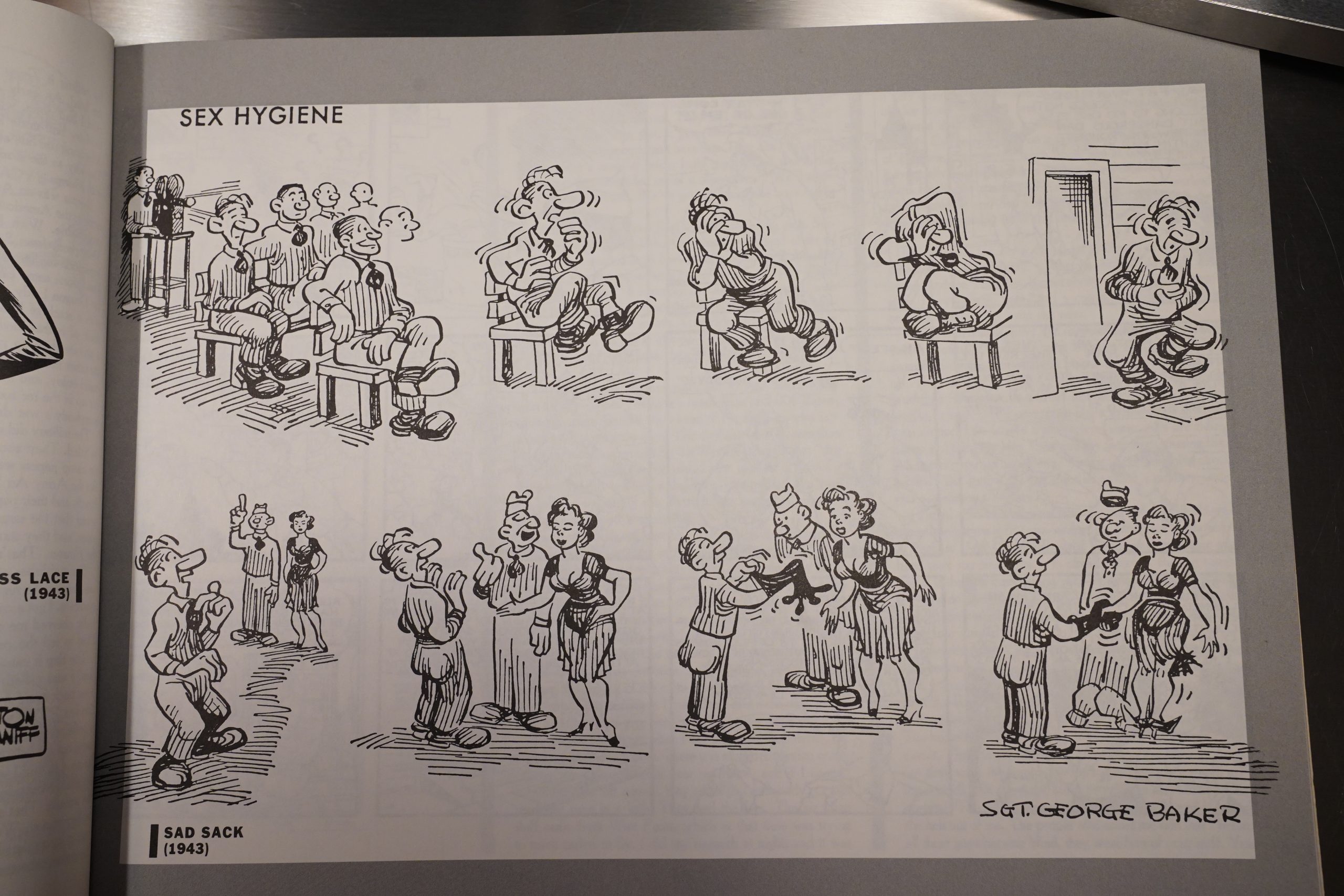

This book reprints Caniff’s weekly strip that he did for the US military during WWII. We get a bunch of background material, and strips by others for the military.

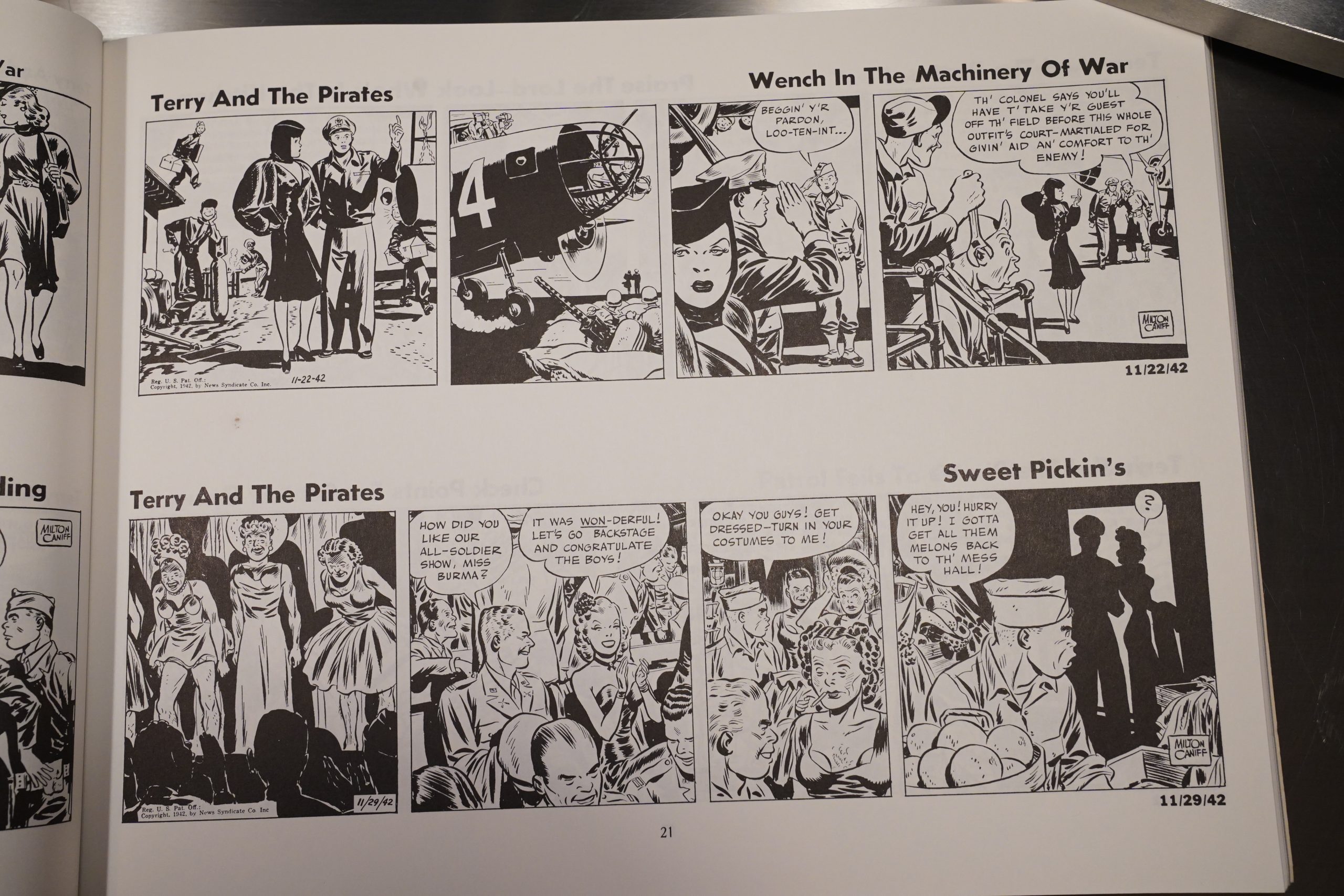

The strip started off as a version of Terry and the Pirates, but as a weekly gag strip with a focus on a character called Burma. The syndicate didn’t like that, so Caniff changed the name to Male Call and carried on.

As gag writers go, Caniff is a good artist.

There’s a consistent theme to the strips, at least. None of them are actually, you know, funny? But they probably did their job.

At least they look good.

We also get strips that were rejected by the editors for being too risque.

R C Harvey writes in The Comics Journal #119, page 115:

Daring for its day, Male Call nevertheless seems

a model of good taste. Still, Caniff had trouble

with censors and would-be censors, chaplains and

the wives of the upper echelon.

[…]But the problem was the pose not the prose.

The explanation: Caniff could do a pin-up Lace

but not if she lay on her back. Reclining was too

suggestive. “I tried every way I could to get her

to sit up in the strim” Caniff laughed, “but I could

never manage it.”

The drawing for the scotched strip, however, he

was able to use in promotions, and the rendering

Of Lace recumbent was eventually so widely circu-

lated that it became the most familiar picture of

his convivial camp follower.

Despite the prominence Of Lace’s figure in Male

Call, only about half the strips deal with sexual

subjects. And lace herself appears in only 95 of

the 160 strips, and only 53 of those appearances

involve sexy innuendo. Some of the unlaced in-

stallments humorously air traditional G.I. peeves

or light-heartedly moraliæ about the soldier’s lot

in the Army or his worries in wartime.

The theme Of G.l. loneliness with Lace as the

antidote pervades the strip, but lace ministers to

all kinds of hurts as well as homesickness, and

she squeezes in occasional lectures on simple good

citizenship or patriotism. By careful design, she

attended to more than the serviceman’s libido

during the run of Male Call; she nurtured much

more than erotic daydreams.

When he was Air Force Chief of Staff a decade

after WWII. General Nathan IWining still remem-

bered lace and the special contribution she and

Caniff made to the war effort: “I don’t know

anyone, at any level, in any service, who didn’t

fall in love with Miss Lace in World War II. She

was everything we’d left behind—a pal and a pin-

up and a laugh when we needed One. She was

Milt’s gift to sevice morale.”

With the publication of the Kitchen Sink book,

we can see for the first time the complete dimen-

sions of that gift—all the strips, plus some fill-in

articles CNS ran about Caniff. (And, for the bene-

fit of historians on the matter, all the strips are

dated, too.) Lace’s final bows in Male Call are

also recorded here—the last strip (March 3, 1946)

and the drawing Caniff did for the Editor

Publisher article announcing her retirement. But

Lace has come Out Of retirement Occasionally since

1946 to grace the covers of programs for Air Force

Association events and other such special occa-

sions, and a sampling Of these encore appearances

concludes the volume.

The book is a richly textured vision of an impor-

tant and unique page in comic strip history, a page

that puts the final touches at last on the portrait

Of Milton Caniff as America’s Kipling.

I’m not saying the dialogue is bad, mind you; the style simply takes some getting used to. It is also easy to see why the wisecracking approach that sustained Caniff so well during the 1930s and 1940s turned off so many people during the Vietnam era, when Caniff’s STEVE CANYON began hemorrhaging readership.

This is the ninety-fifth post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.