Tin Signs

This blog is about the comics Kitchen Sink published, so I’m not going to cover all the merchandise that Kitchen Sink was pushing. But I thought it might be interesting to have a look at a couple of tin signs (because that’s a pretty odd thing to be selling), and at the same time, natter on a bit about… just what on Earth is going on at Kitchen Sink at this time?

Kitchen Sink had always, it seemed to me, been quite… canny about what they were publishing, and as a result, had a pretty distinct publishing profile. But over this period (1992-93), they seemed (to me) to be publishing lots of eclectic stuff that’s all over the place… so how come?

For most of Kitchen’s history, the firm had been cash-strapped. You’d think that they were swimming in money during the first Underground comix era, but nope — they were giving the artists so much royalties that they were basically just breaking even. By the time they brought in a business guy to figure things out (he brilliantly made the decision to lower the royalty rates — what would we do without business guys!), the Underground era was almost over, and Kitchen sink almost went under anyway.

The climb back up into being a real business was a long slog (from 1975 to, say, 1980) when they started getting some regular cash flow going, first with the Spirit magazine, and then with some somewhat successful alternative comics.

They hit on an unexpected hit with Megaton Man, but that petered out pretty soon as the artist ran out of steam, and then there were several meltdowns in the 80s direct sales market.

But by 1992, Kitchen Sink were flush with money — for the first time in their history. They were employing about 15 people, full time, and this was based on basically three things:

1) Omaha the Cat Dancer. This series, mixing soap opera and sex, was a hit, and sold steadily, and importantly — it came out pretty regularly, so there’s a steady cash flow. The first collection was the highest grossing item Kitchen Sink ever sold.

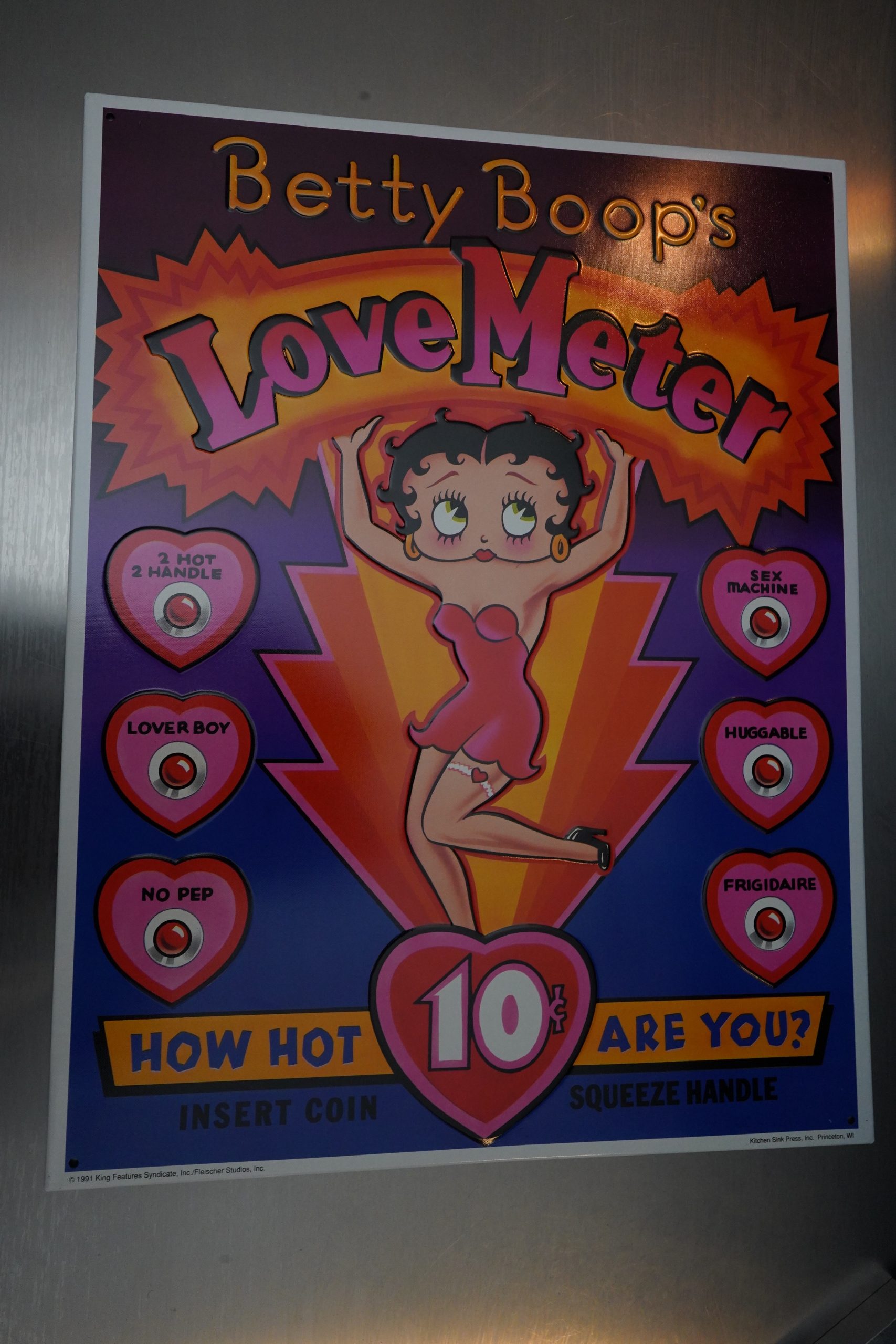

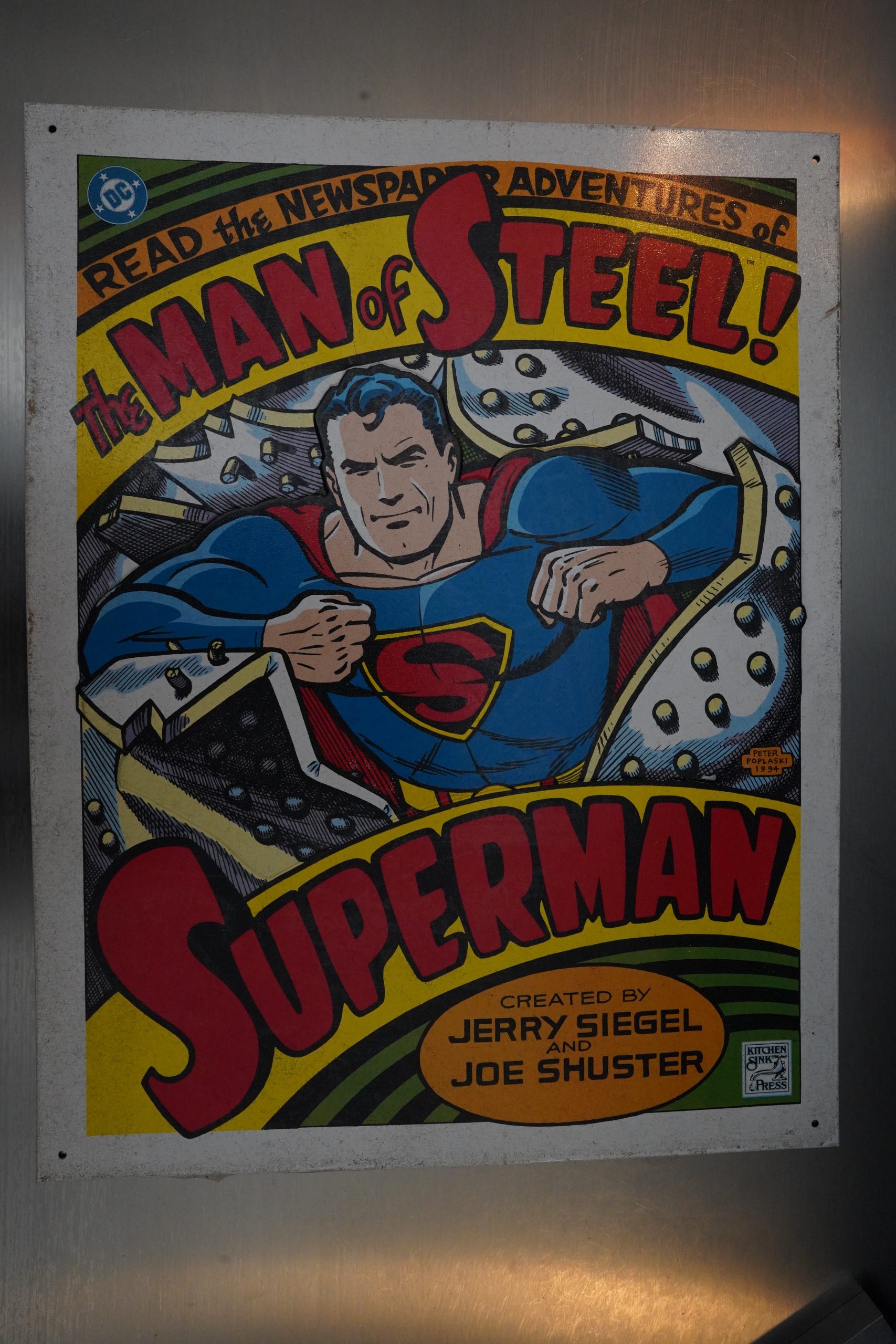

2) Kitchen Sink and novelties and hits: Both the first Nancy and Lil Abner collections got a lot of mainstream press, and sold a lot of copies in the bookstore market. (Unfortunately, Berkeley, the distributor, were slow in getting reports back on the sales of anything, and the rest of the books sold poorly — but they didn’t know that until a year later when they got all the books returned.) Kitchen Sink also got heavily into the novelties market, of which these tin signs are examples. They did non-sports trading cards, and they did so many pins, and t-shirts, and even chocolate bars. (I’m guessing quite a few of those people working for Kitchen were generating these novelties… You hire more people, who generate more stuff, so you hire more people…) But the chocolate bars brings me to:

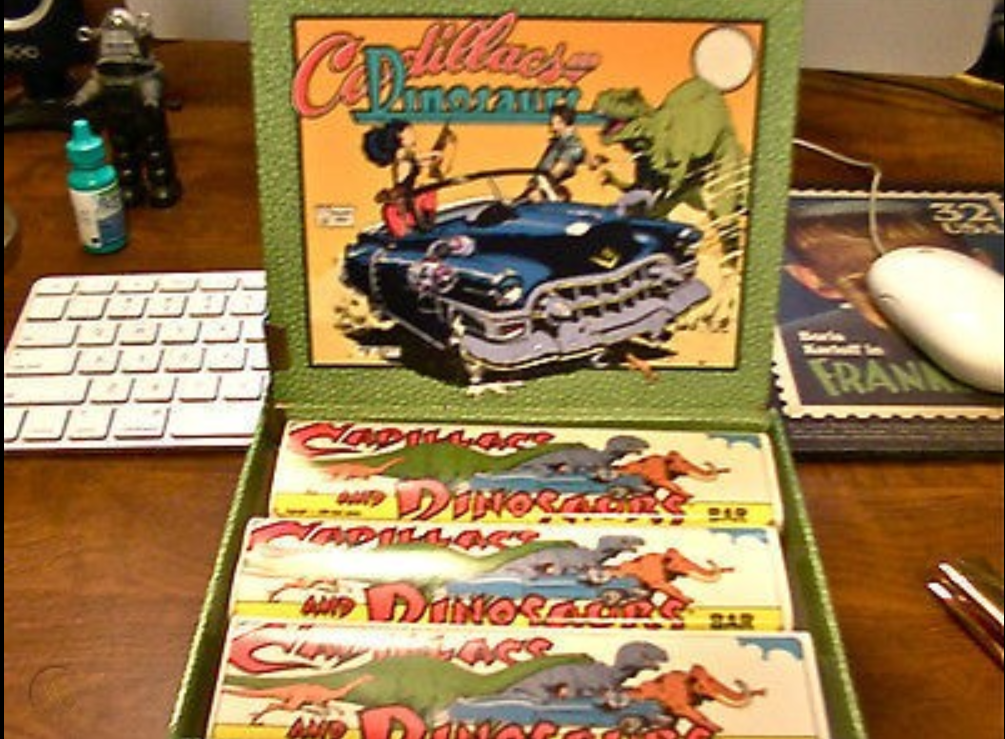

3) Xenozoic Tales. From the start, everybody loved Mark Schulz series, and it sold like hot cakes. But more importantly, everybody wanted to make an adaptation of it, and I guess during a pitch meeting some really wise person said something like “but what’s the essence of this thing… it’s about… Cadillacs… and dinosaurs! That’s it! Let’s call it Cadillacs and Dinosaurs!” And so they did, and then they sold candy bars, and licensing money flowed freely. It was too bad that the animated series failed to impress and sank after one season, but in 1992 at least, money was flowing.

And Kitchen Sink used that money to push out a number of pretty oddball, not very commercially successful books, which we’ll be covering over the next few weeks.

But what about these tin signs? Well… they’re signs… made of tin. And they’re embossed. They’re quite nice? Quite nice.

This is the one hundred and fourtieth post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.

Where can one see all of the cards in the saucer people deck, I just saw a documentary on Prime and I’d like to see the rest of the cards is that possible?