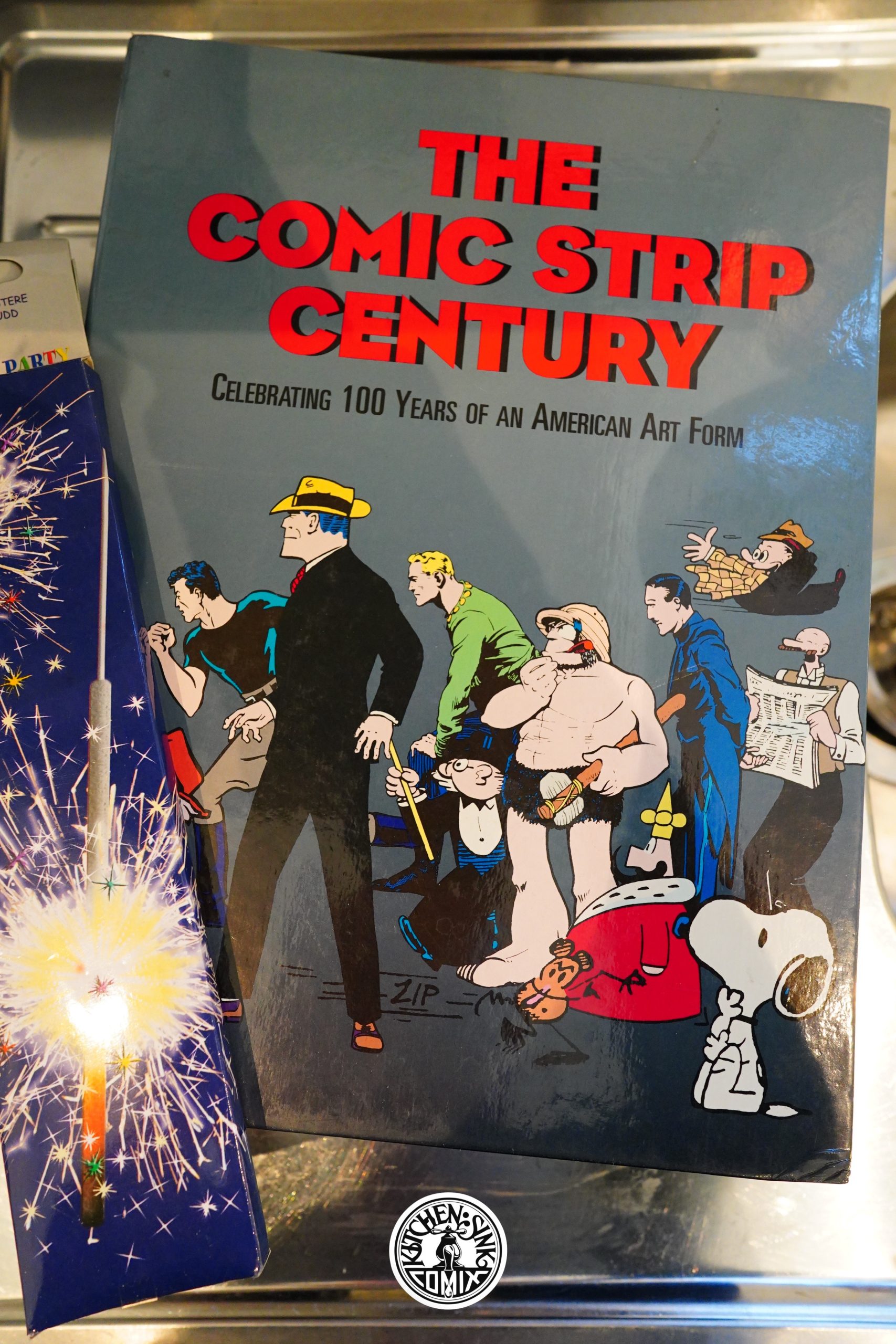

The Comic Strip Century: Celebrating 100 Years of An American Art Form (1995) edited by Bill Blackbeard and Dale Crain

I’ve read more than more share of histories about comic strips, so I was less than enthused by the prospect of reading this box set. It’s two hardcover books in one box, which is a good choice, because each individual book is pretty heavy, and having it all in one book would have been unwieldy.

But I wonder whether that was the original plan? The numbering across the two volumes are continuous (i.e., the first page in the second volume is page 231), and there design on both volumes are the same (which seems like a missed opportunity).

And while I’m kvetching about the physical format — this isn’t cloth-bound: The signatures are just glued together, and you really have to crack the spine open to read it, so I guess it’ll fall apart after reading a few times. (The copy I got from ebay was previously unread.)

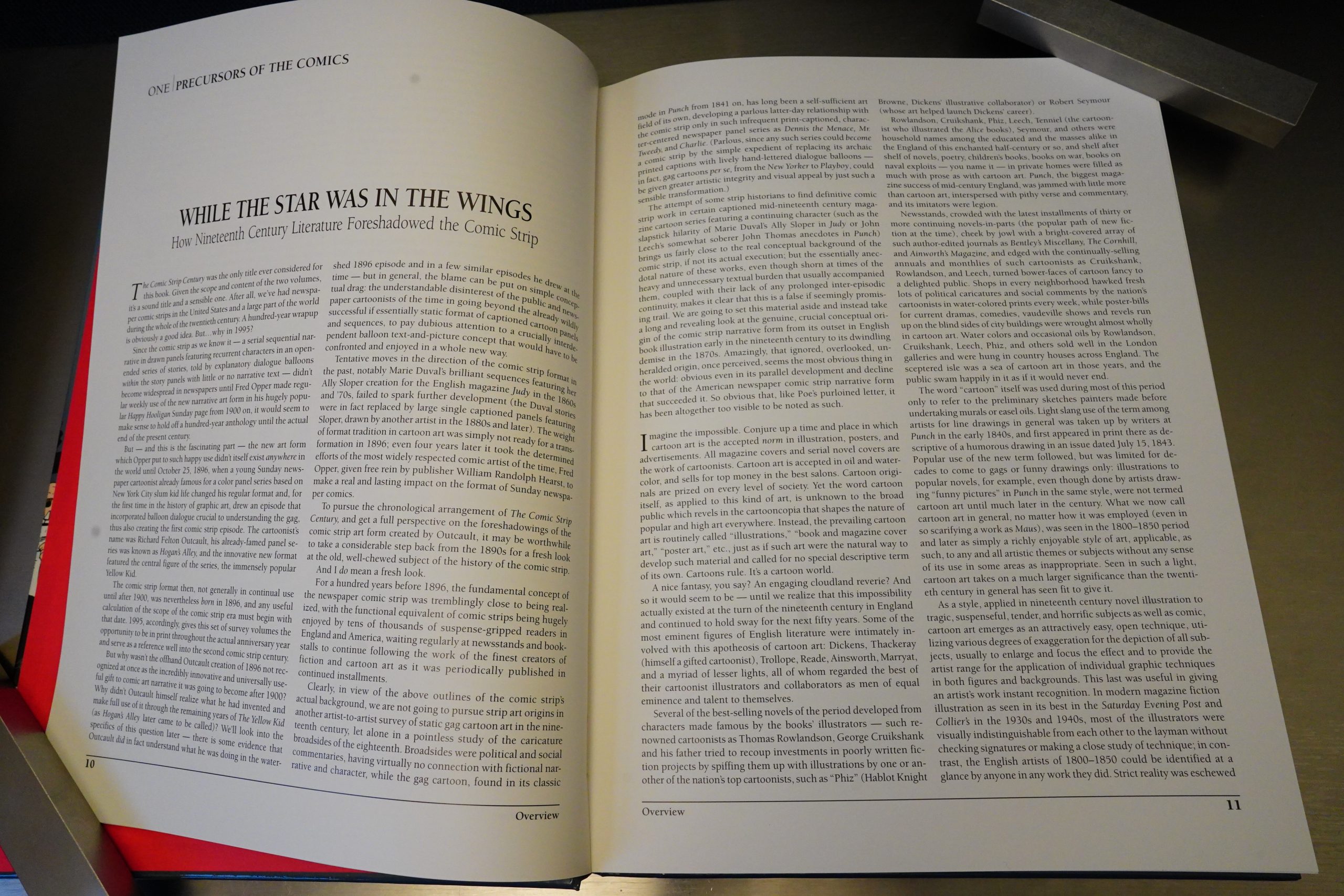

We start off with a thirty page historical overview (which I skipped; sorree)…

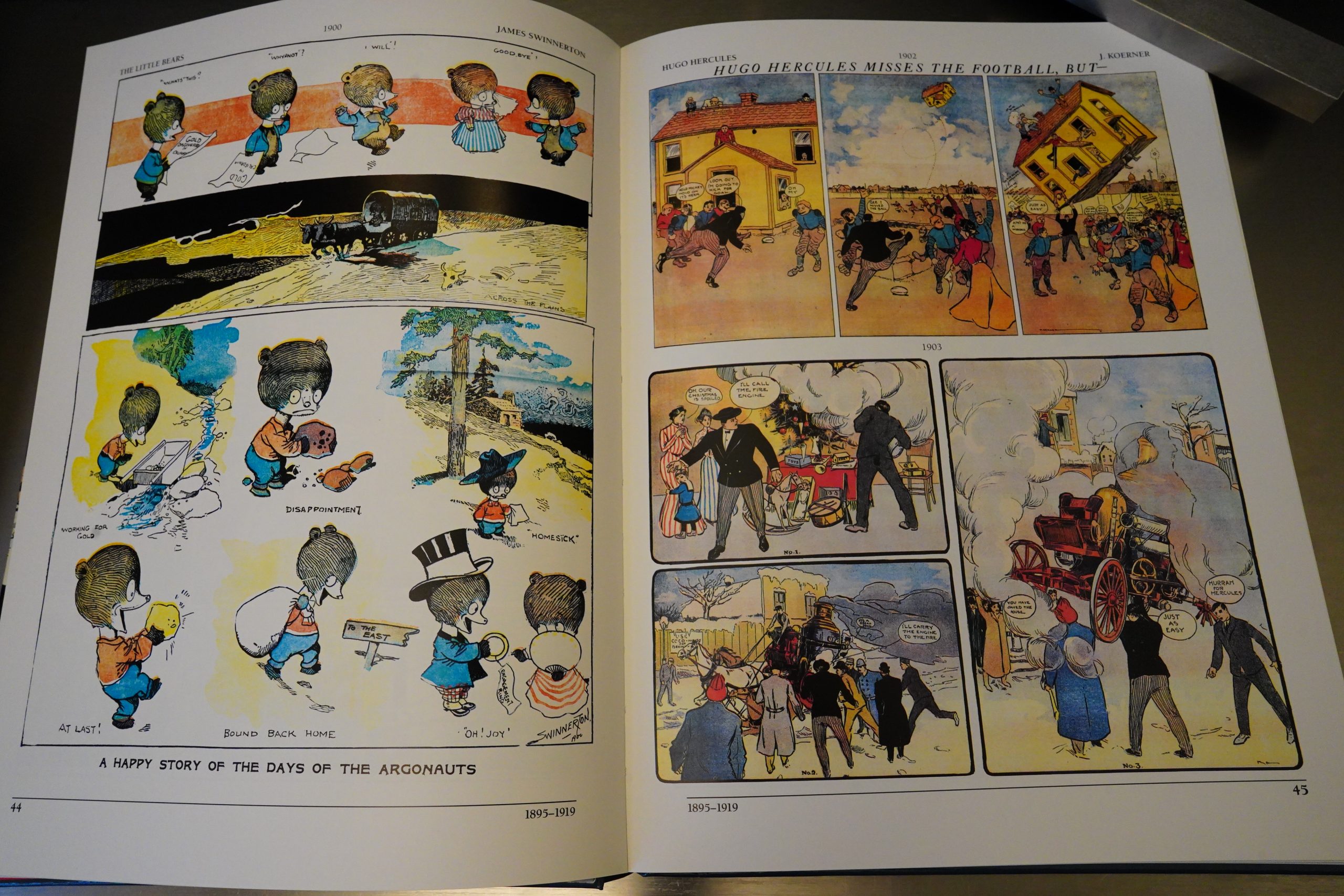

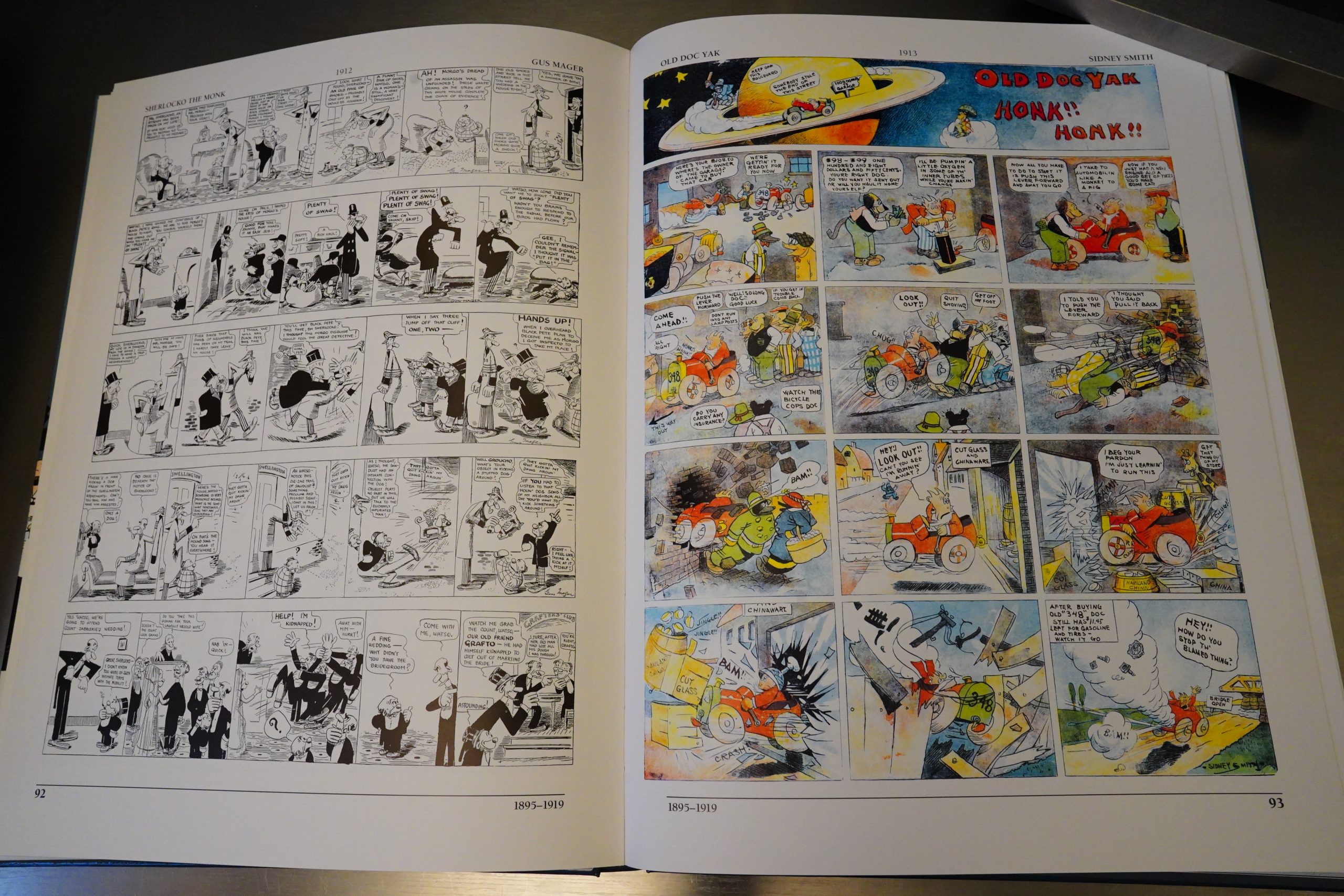

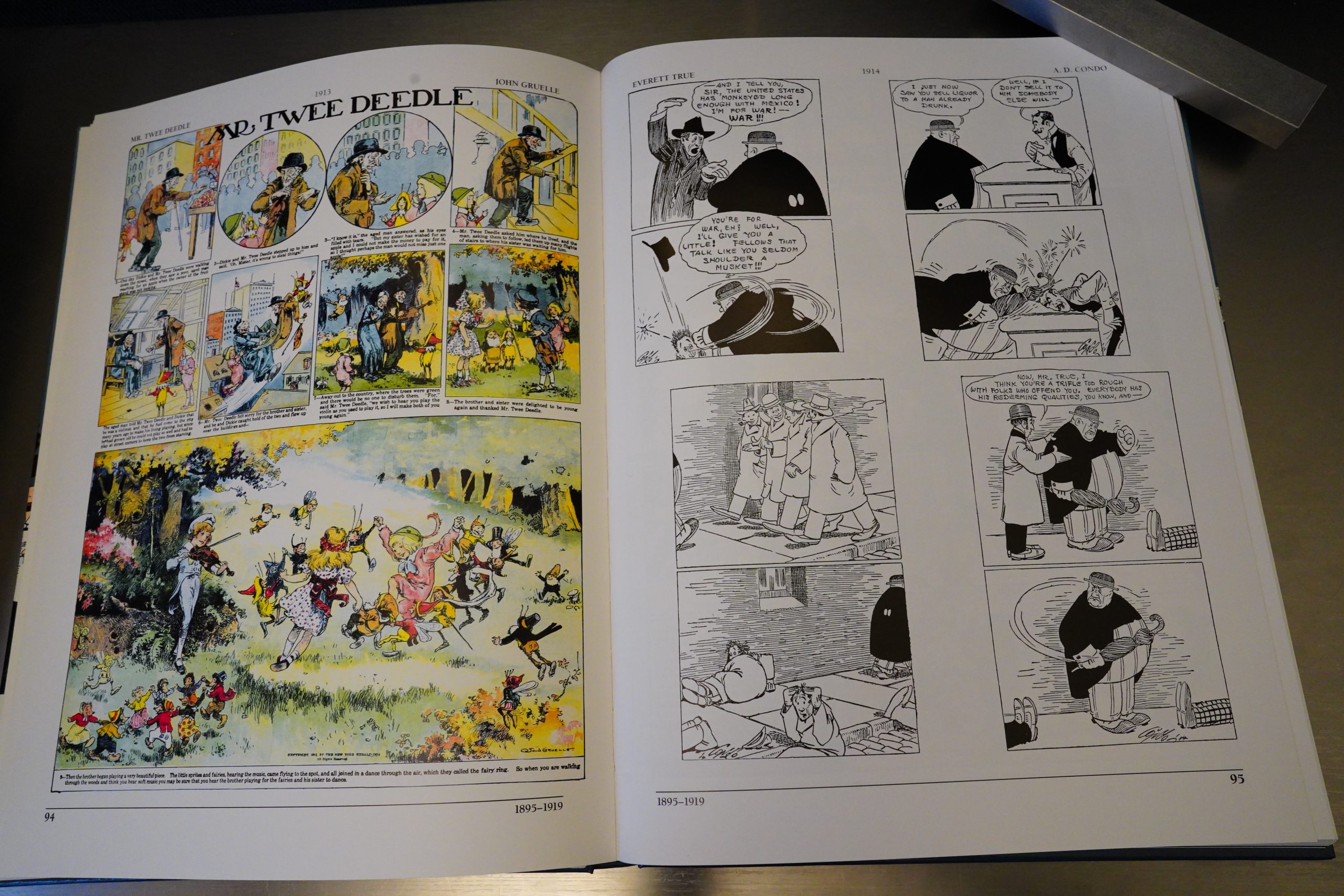

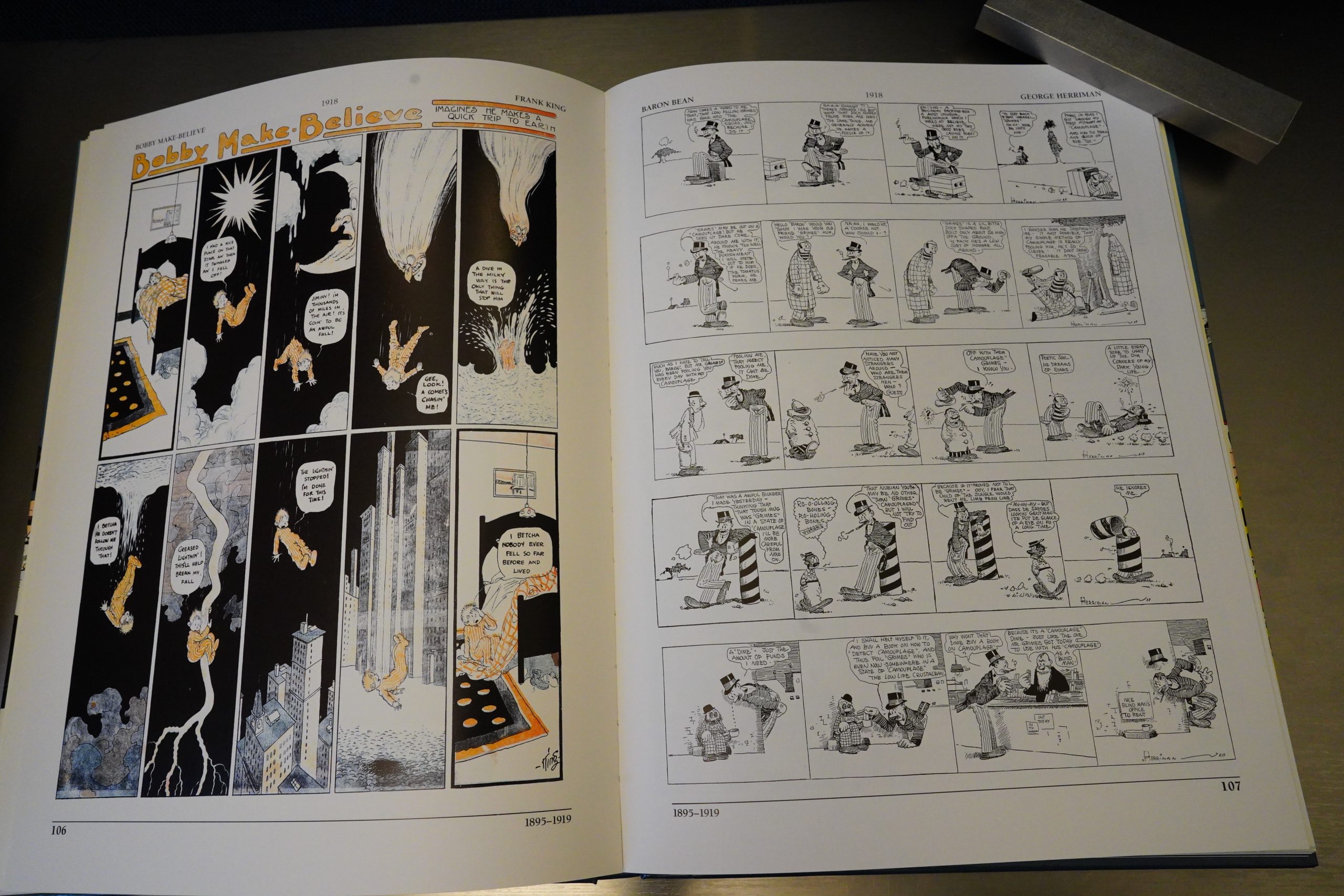

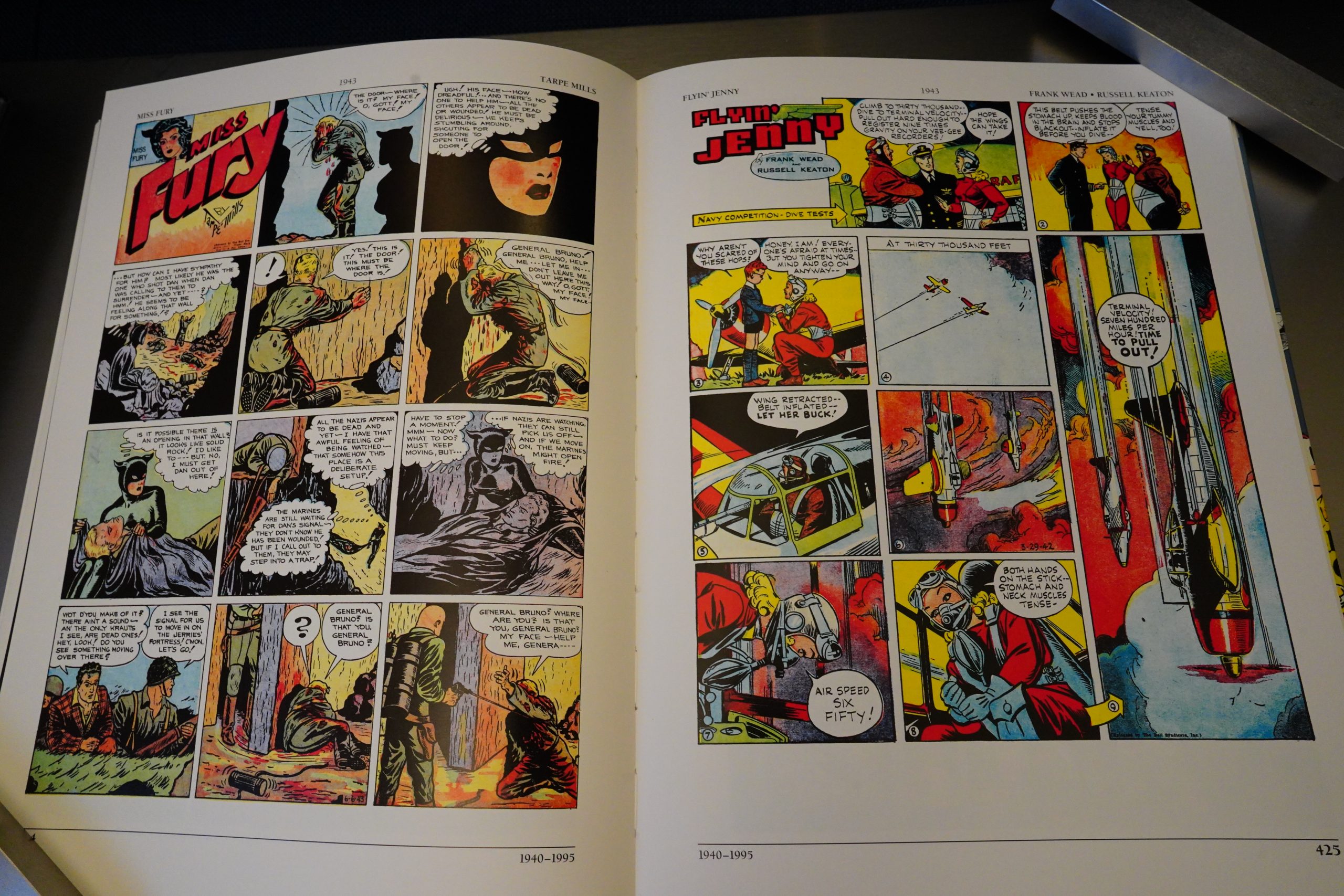

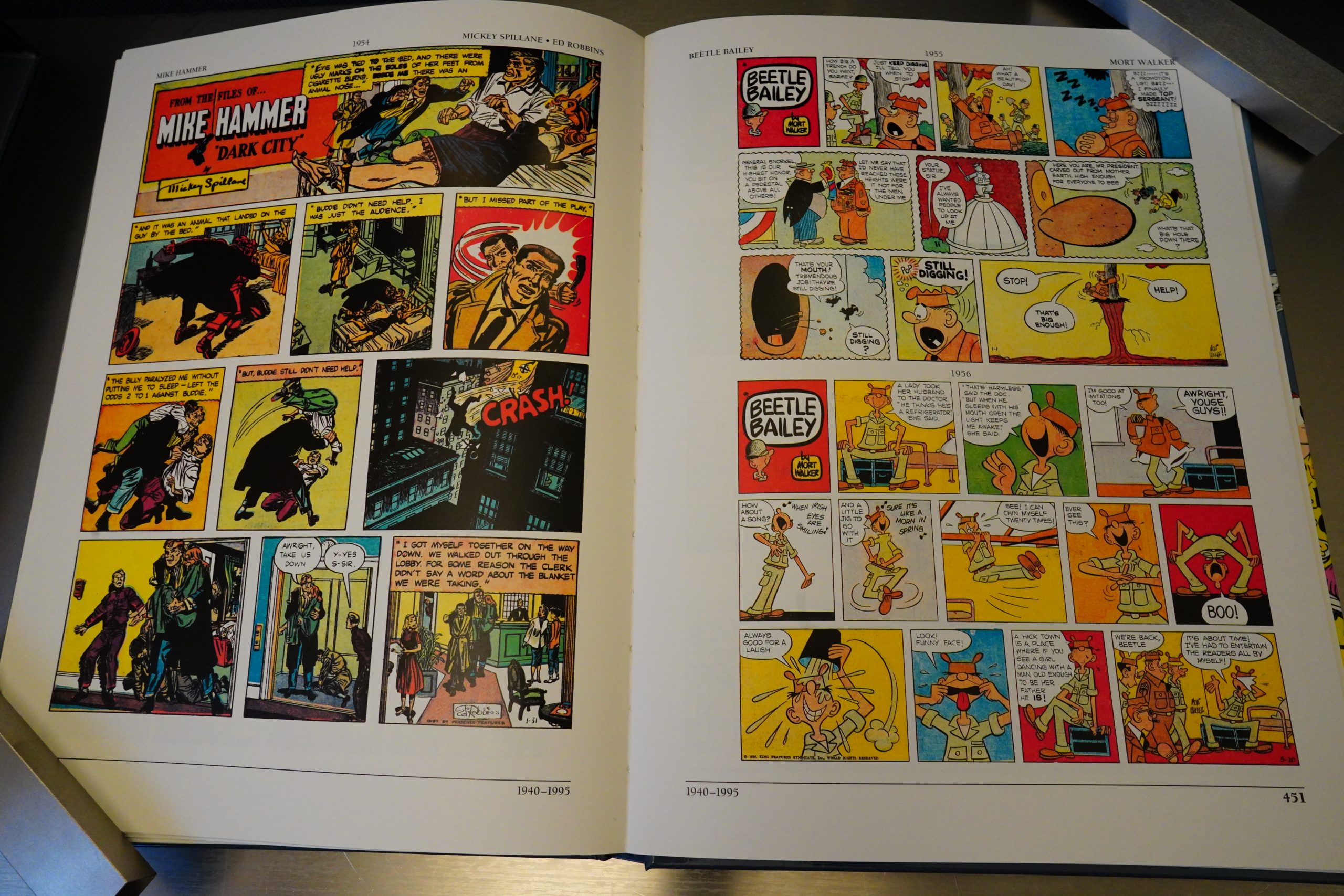

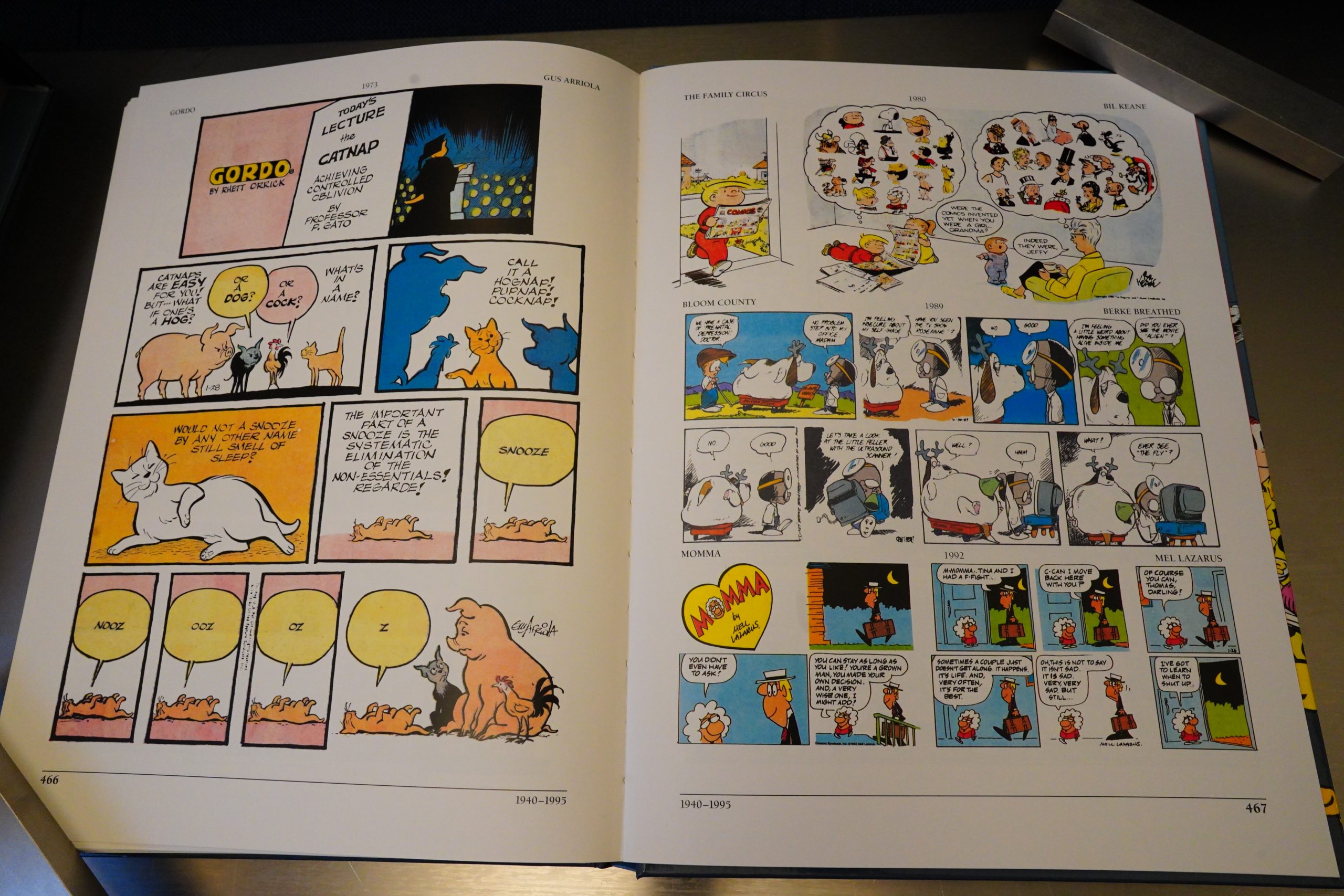

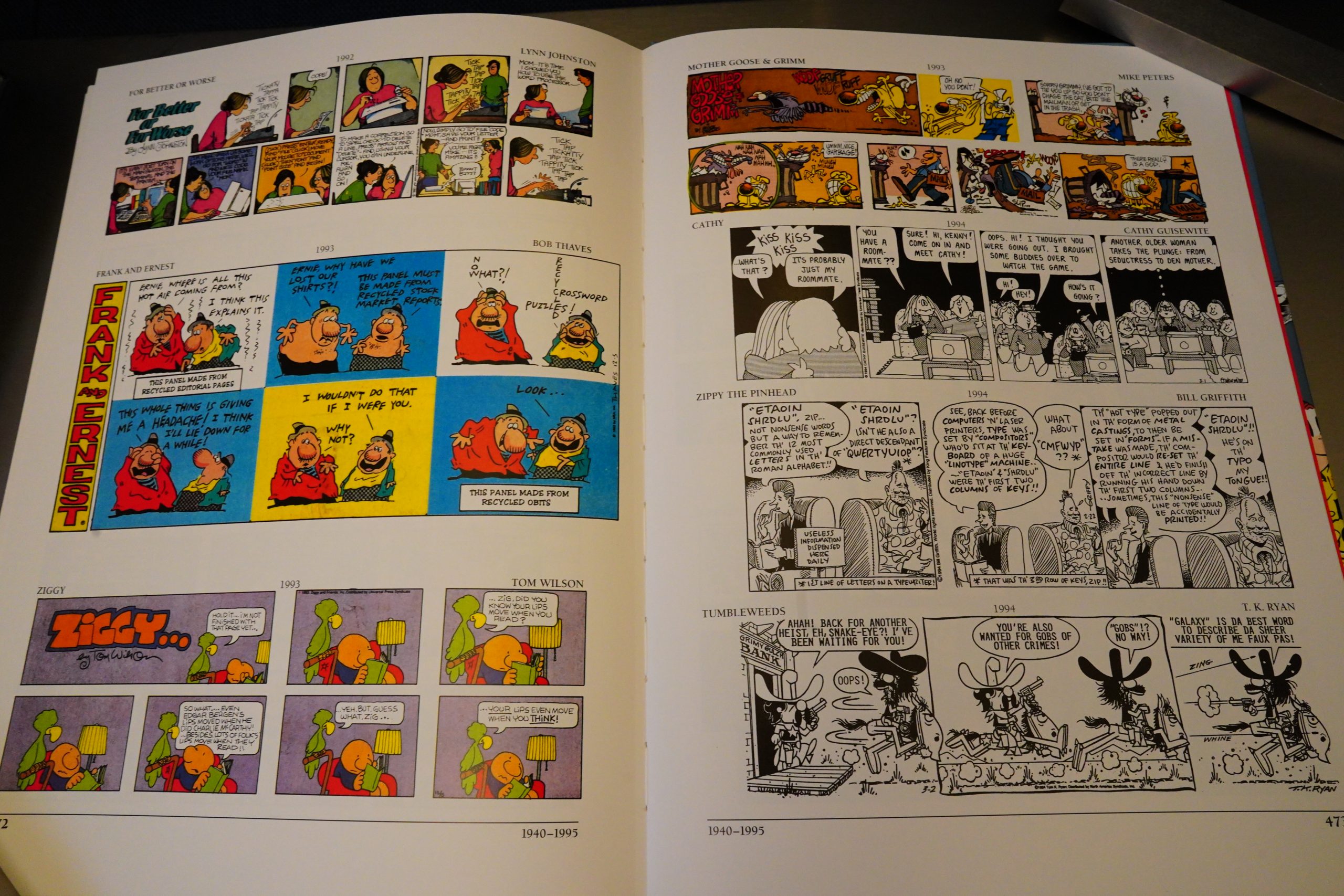

… and then the rest of these five hundred pages are just reproductions of strips, with no accompanying text.

Which is such a relief! If I had a dime for every time I’d read a strip reprint project where the editor just can’t shut up, and seems to feel the necessity for carrying on the hard sale throughout the book, I’d probably have a dollar by now. Perhaps two!

The common trope is that the editor can’t stop gushing about how great whatever artist is, and what a genius he is (always “he”), and how fantastic the page we’re looking at is… and that just makes me go all contrary and I’m like “no! this sucks!”

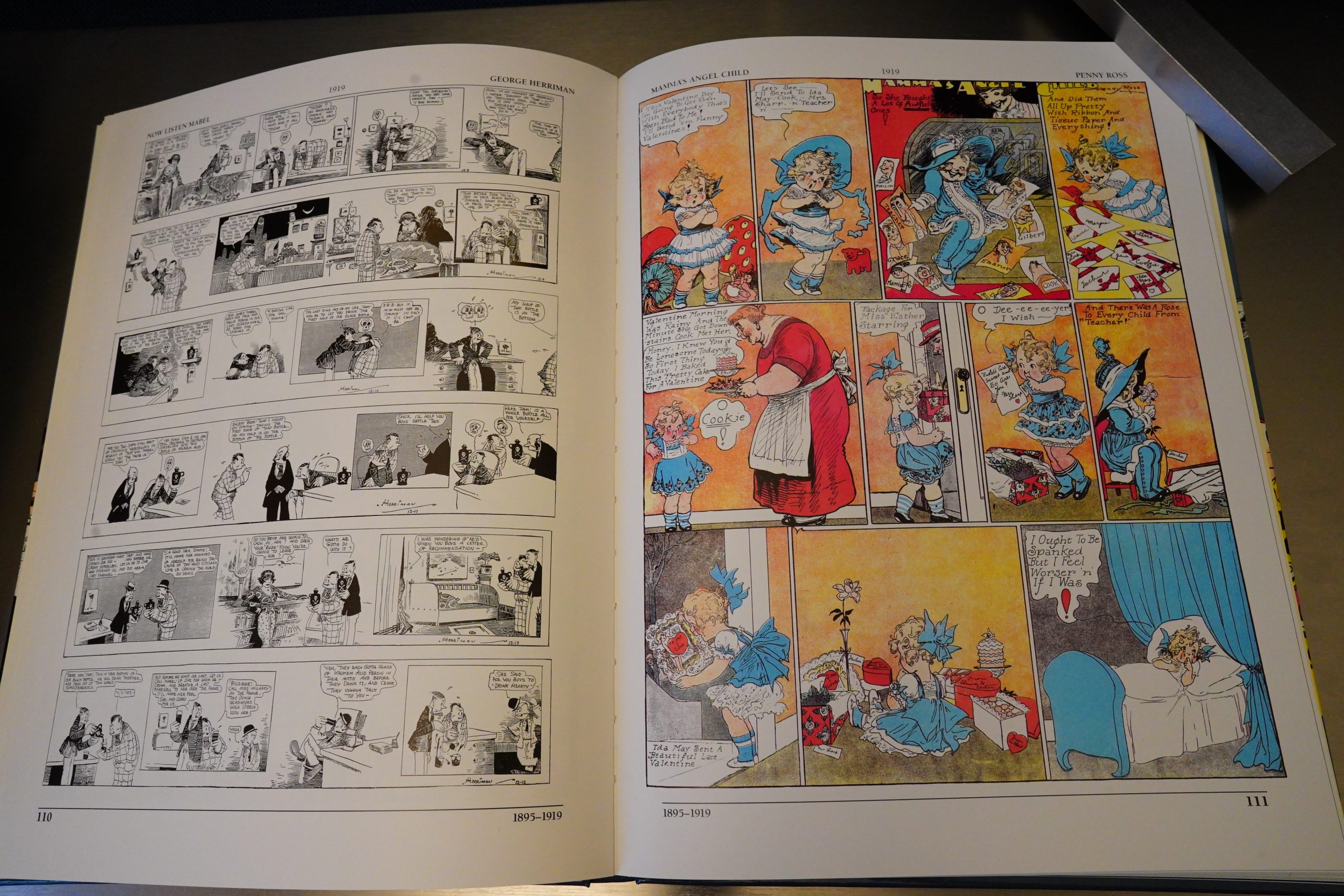

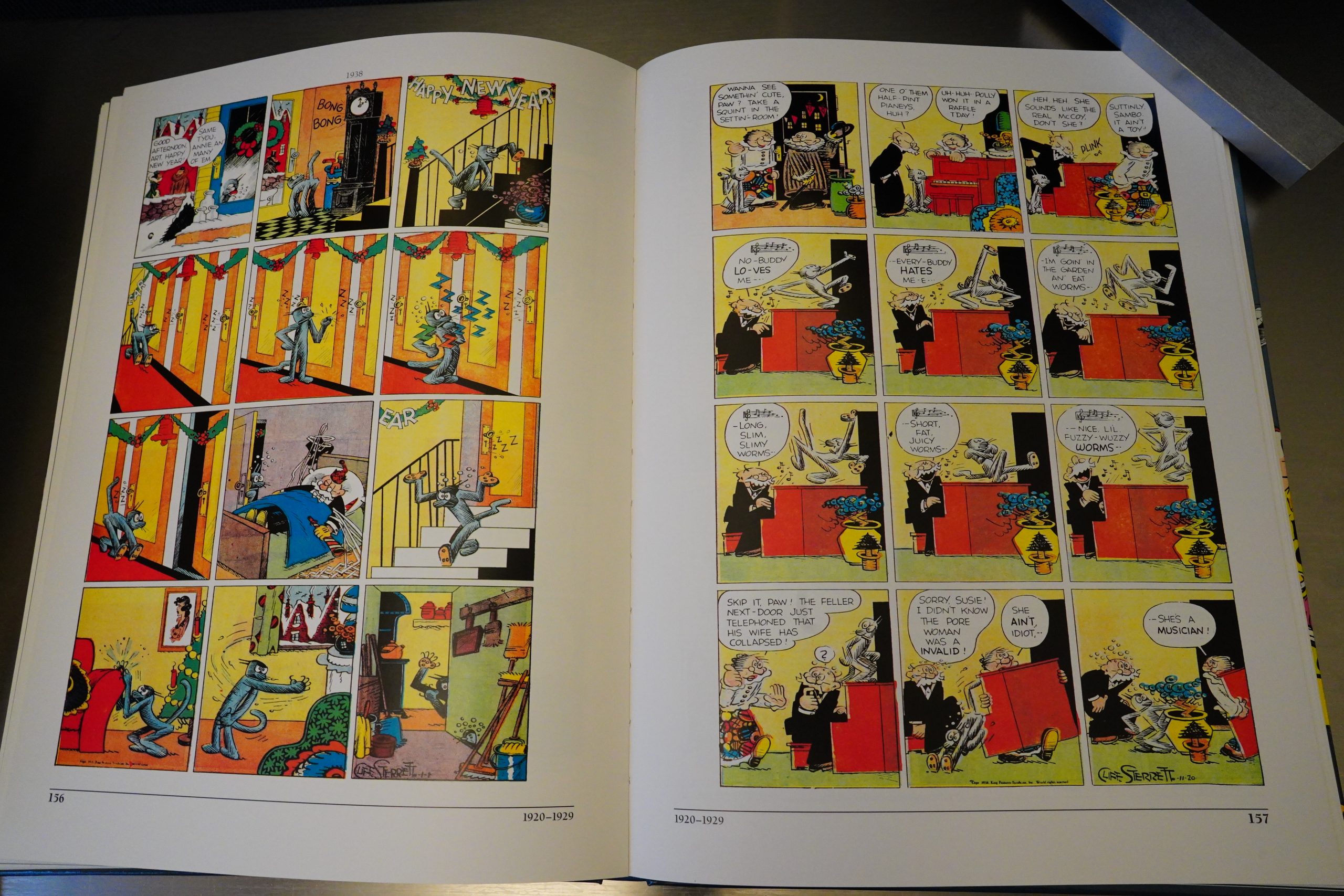

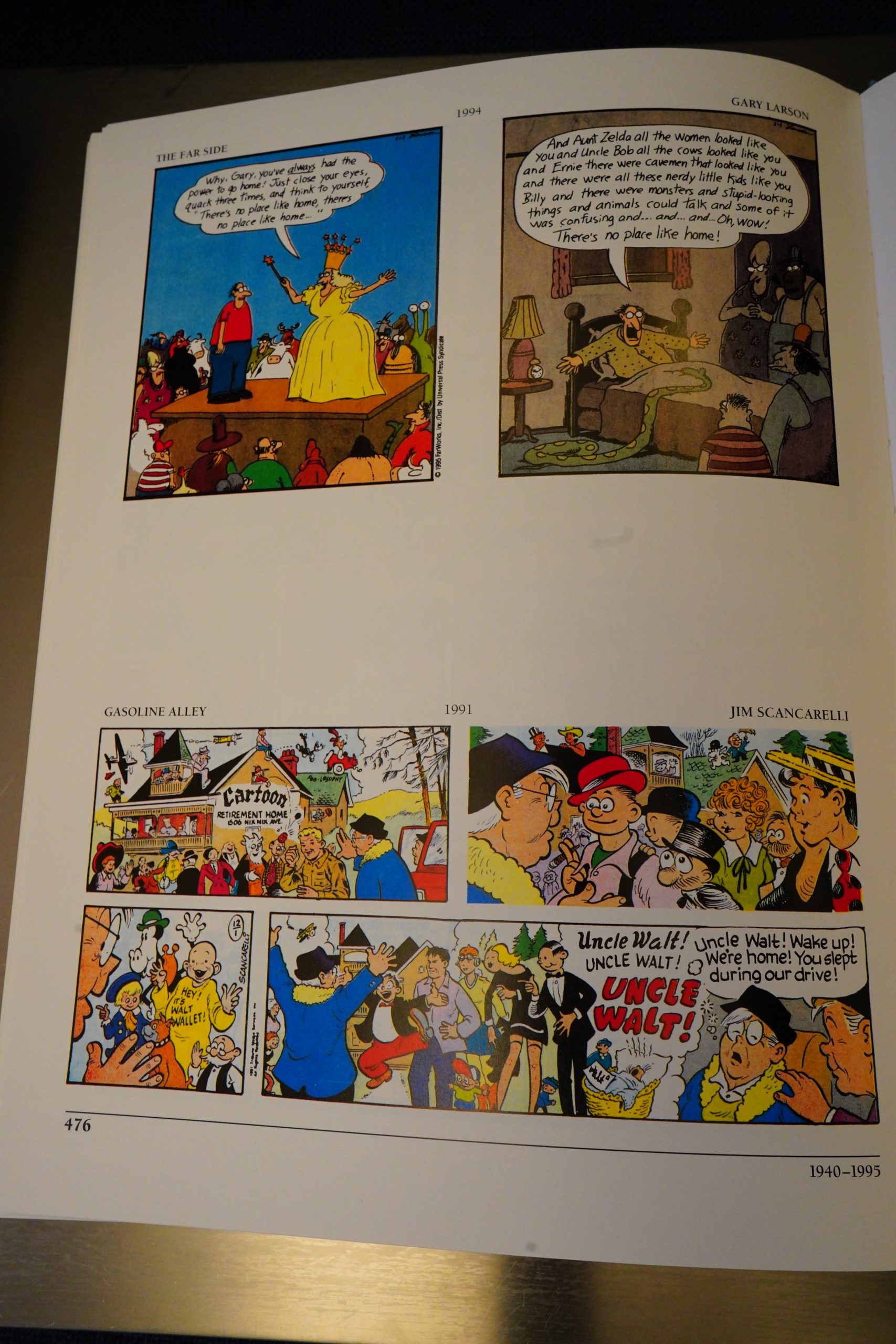

But this book is silent: You get the name of the artist, the name of the strip, and the year. It’s wonderful! Reading this book is the perfect experience of these old strips — every time you turn a page, there’s some new delight, reproduced wonderfully, instead of having somebody explain every minute reference, pointing out what the joke was, and draining every ounce of joy out of reading and making the book into homework.

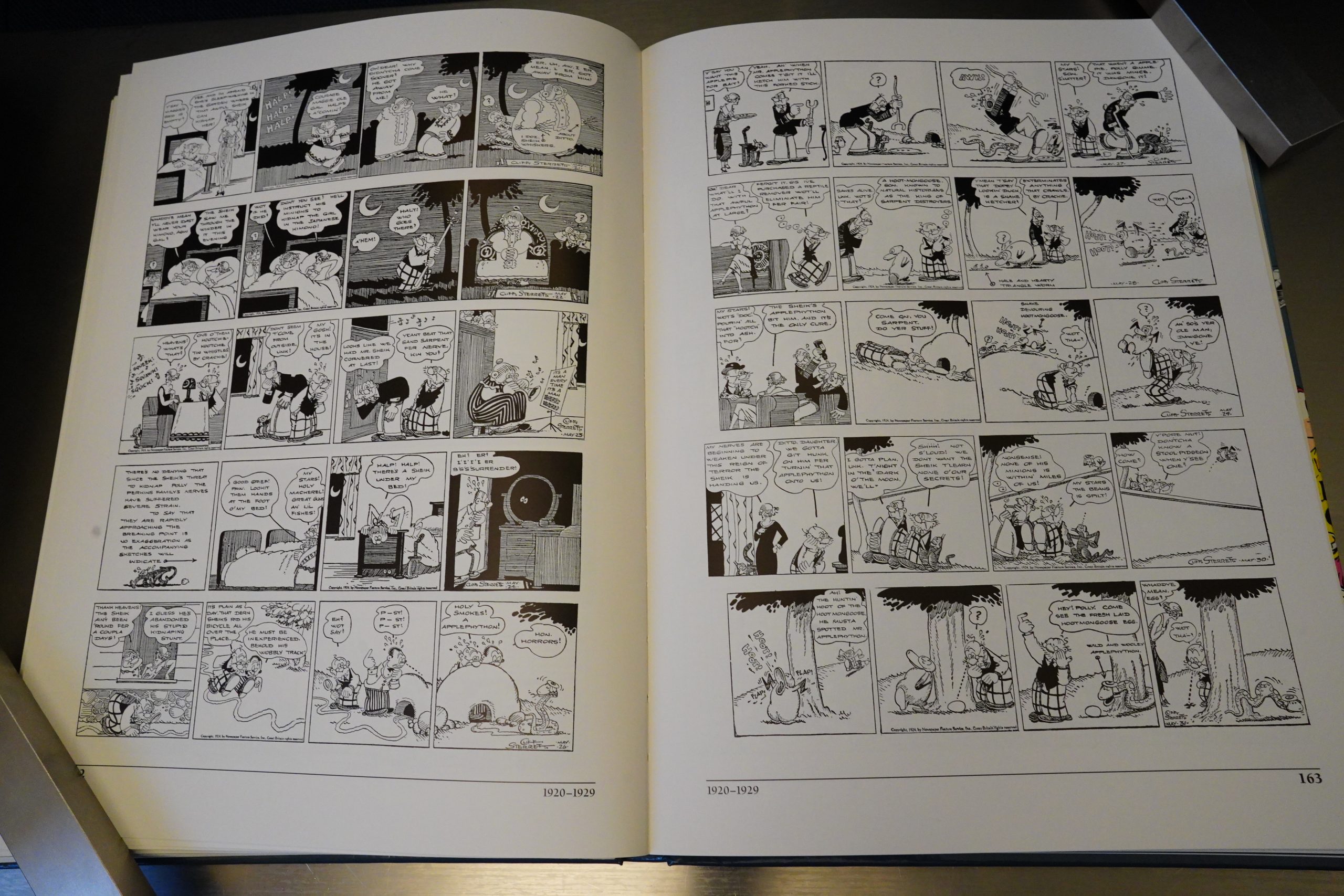

And it’s not just Sunday pages, either — we get quite a few dailies, too.

So many people I’ve never heard about before.

And, of course, all the famous ones, too.

There’s only a handful of women cartoonists included.

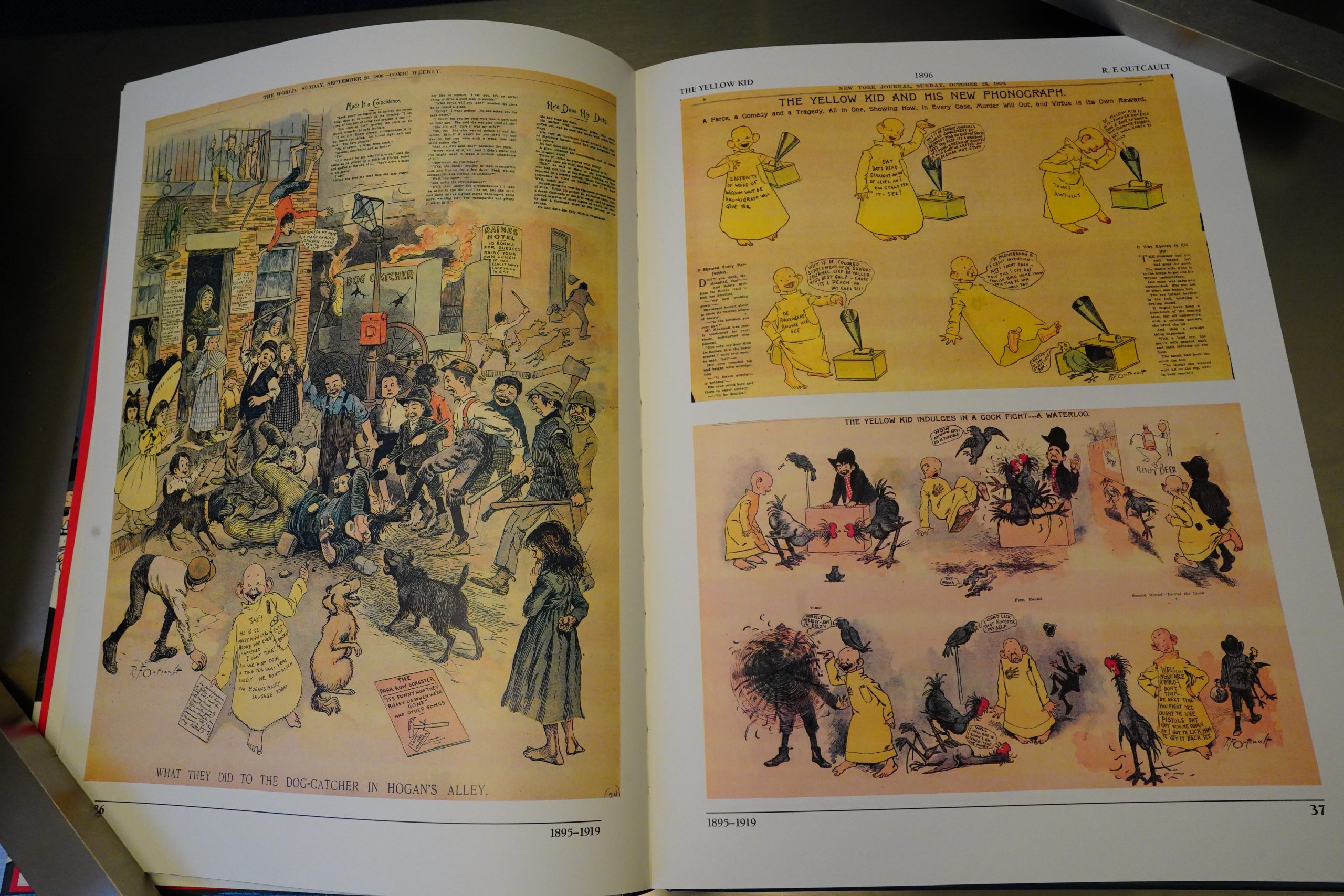

Did I mention that the reproduction on this is great? The colours really pop, but not to an unnatural degree. The linework is unbelievably well reproduced on most of these things — reproduced from proofs, perhaps? The paper is white and shiny, which helps with the colours and the linework, but it’s not of that super-shiny variety, either.

My one complaint is that it’s sometimes a strain to read the lettering because of the size. It’s basically slightly larger than standard album size, and it would have helped a lot to just have it, like, 5cm wider. But that would probably have been prohibitively expensive — as it is, I’m guessing Kitchen Sink lost a lot of money on publishing this. (But then again, it’s Kevin Eastman/Ocean Group money to squander at this point, so…)

Like I mentioned, there’s also dailies included, and the book is not divided into a colour and a black-and-white section — everything just flows naturally. And with the dailies, we don’t just get a random sampling, but we get longer narratives, like this ten page Polly and Her Pals story.

The selection feels really thoughtful — the book does not feel like a random collection of whatever the editors could get their hands on, or to cram as many artists as possible in to these pages. Instead they make selections that include awesome art, funny bits and thrilling sequences to read.

This is, simply put, the best book of its kind I’ve ever encountered. (But I haven’t read the Smithsonian collection of strips from the 70s that was supposed to have been very influential.)

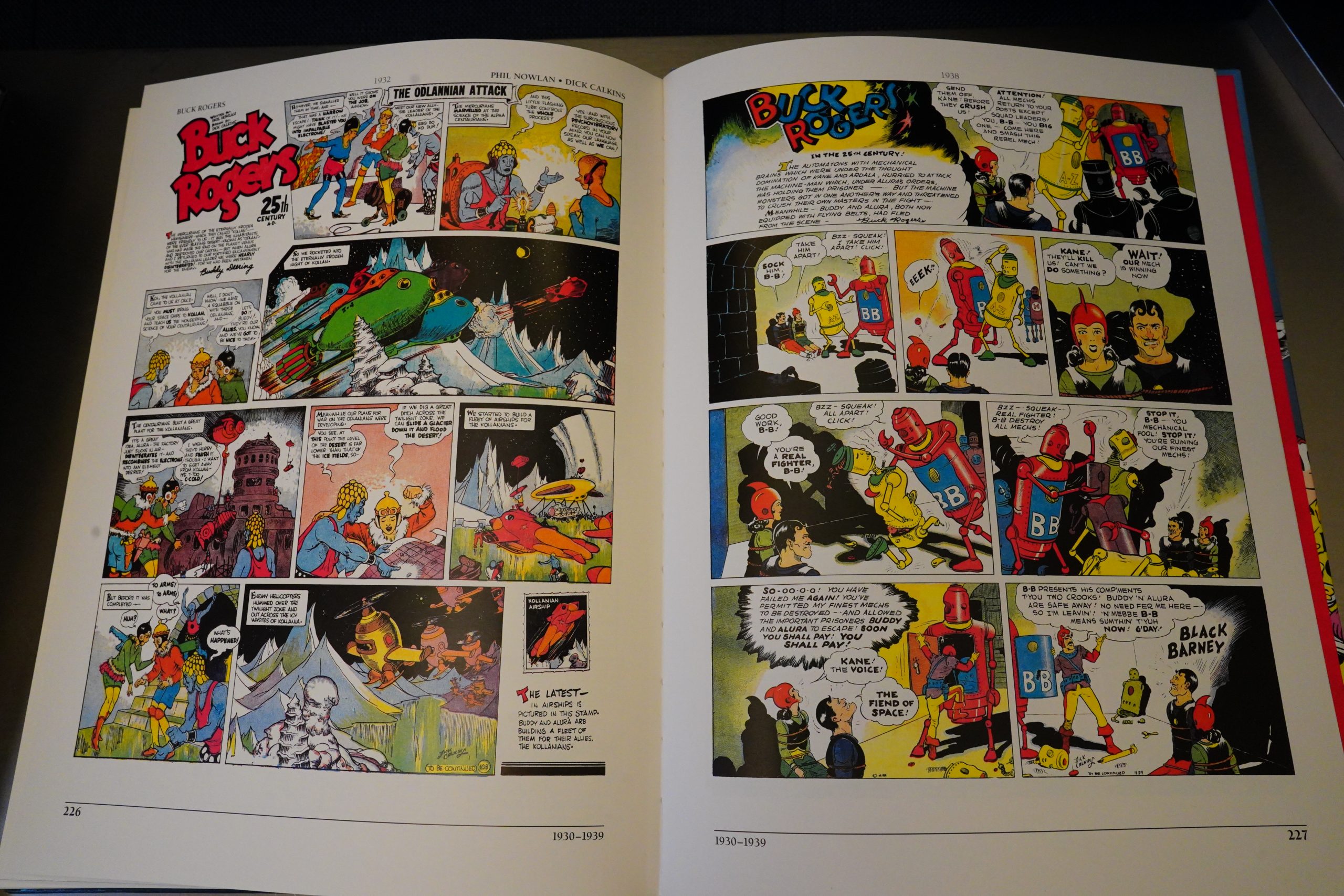

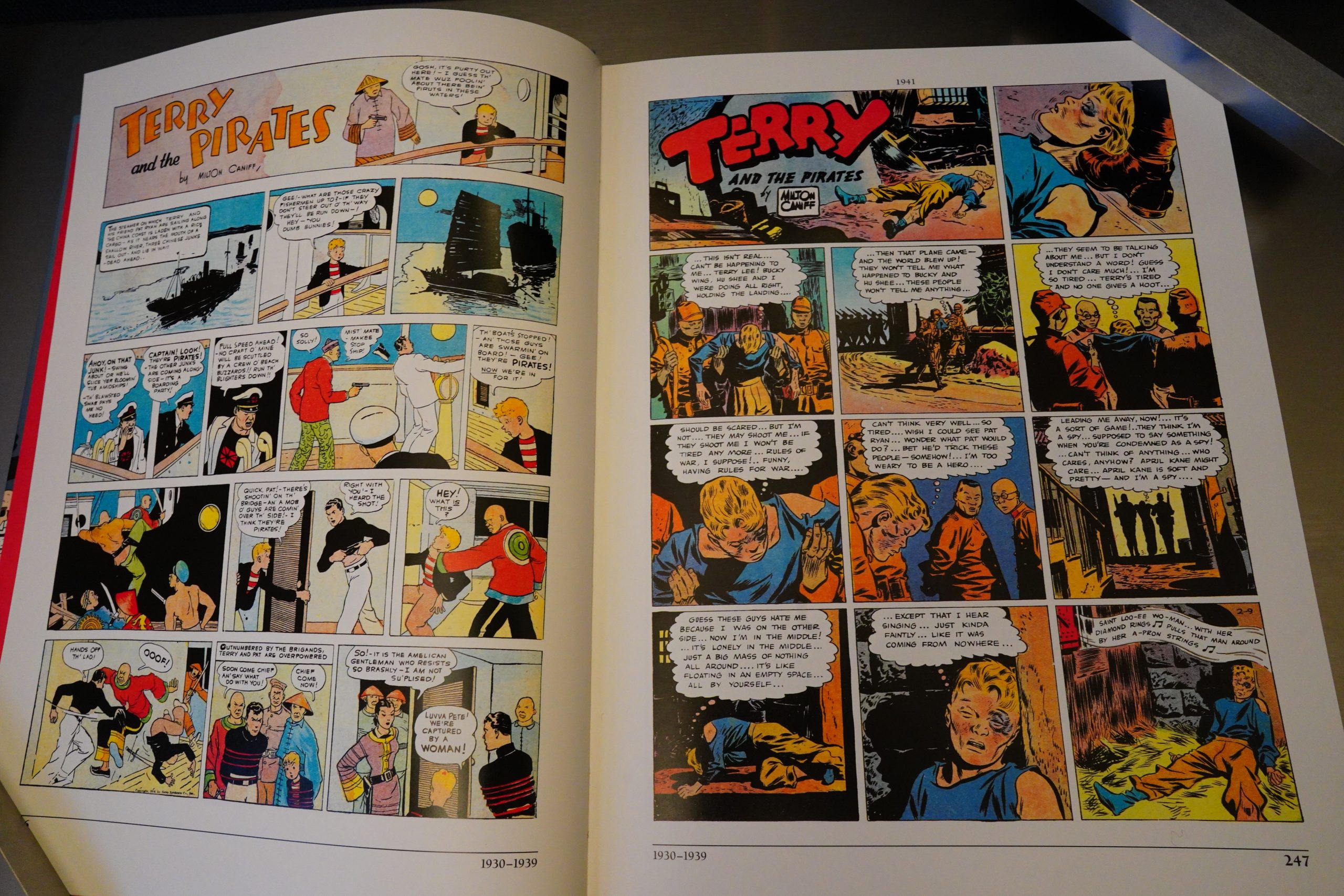

When we get to the 30s, we get more adventure serials, and the editors seem to struggle a bit more with selecting stuff. These two Buck Rogers Sunday pages look very impressive, but rather random.

Same with these two pages — it seems like the editors going more with “well, we have to include this, but… what…”, so it gets more of a “sampler” vibe. But it’s fine — they’re still picking good pages.

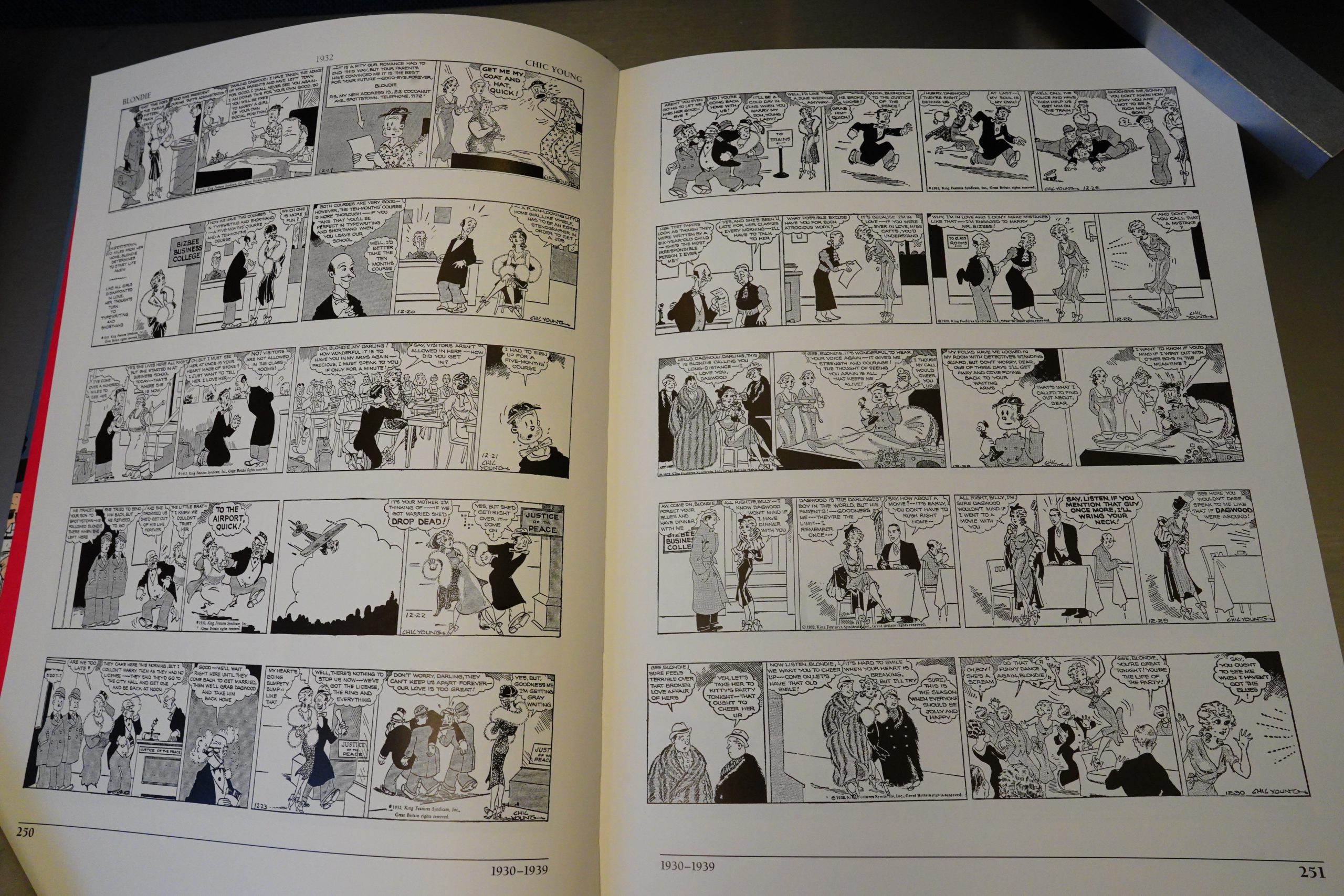

The longest section in the book is this Blondie sequence — we get 25 pages of this, which seems, on the face of it, an absurd way to spend 5% of the book. But no! I’ve only seen later Blondie strips, and they’re kinda dull, but this has a lot of zip, and a bunch of funny gags. Over the 25 pages, we get one long sequence about Blondie marrying Dagwood, and how much his millionaire parents opposed the marriage, and then into their married life, and it’s great. And it makes perfect sense to include it, to give a respite between all the adventure strips.

Which are mostly represented by pages like this — which makes for choppy reading, and are perhaps more to gaze at than to read when you only get a single page.

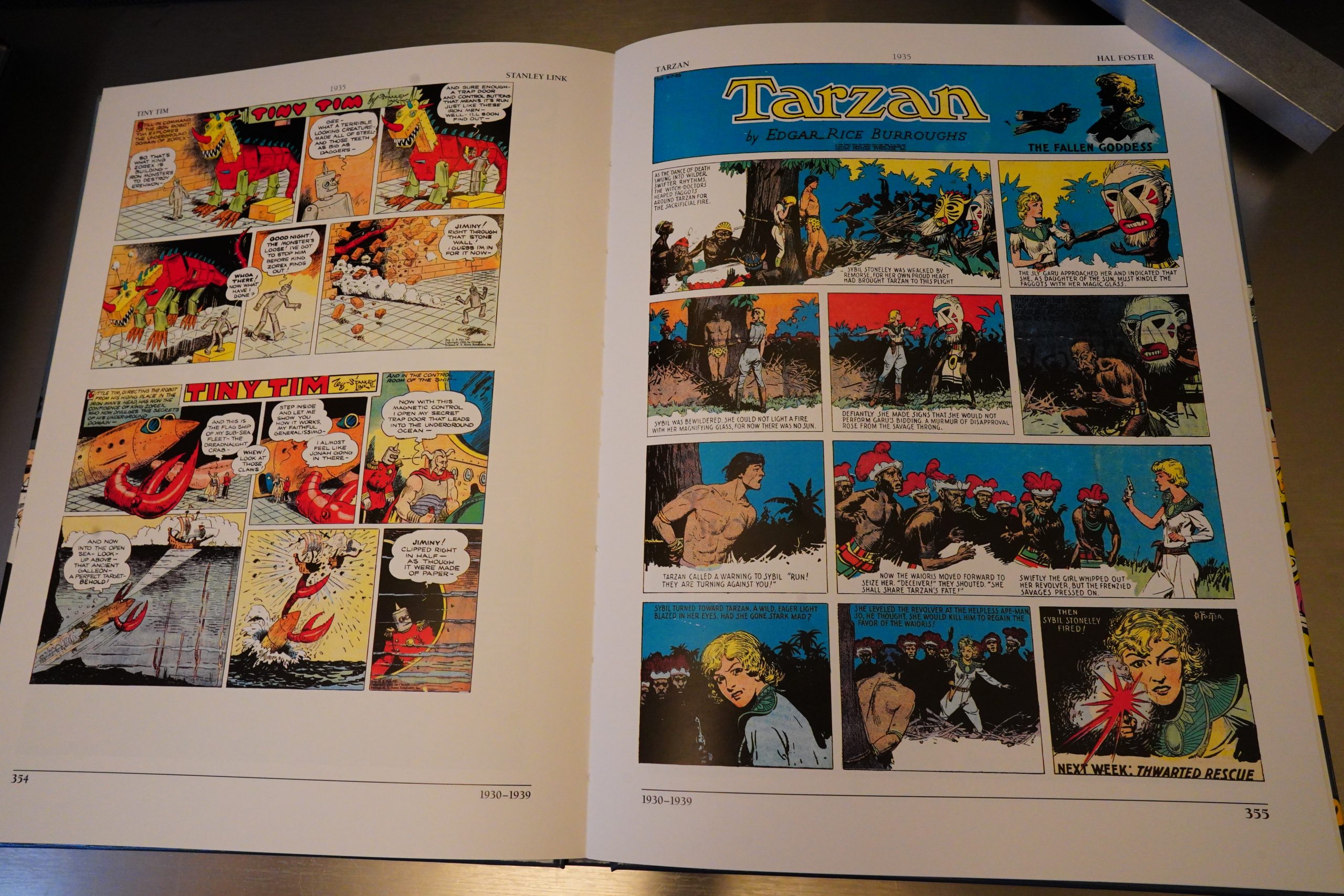

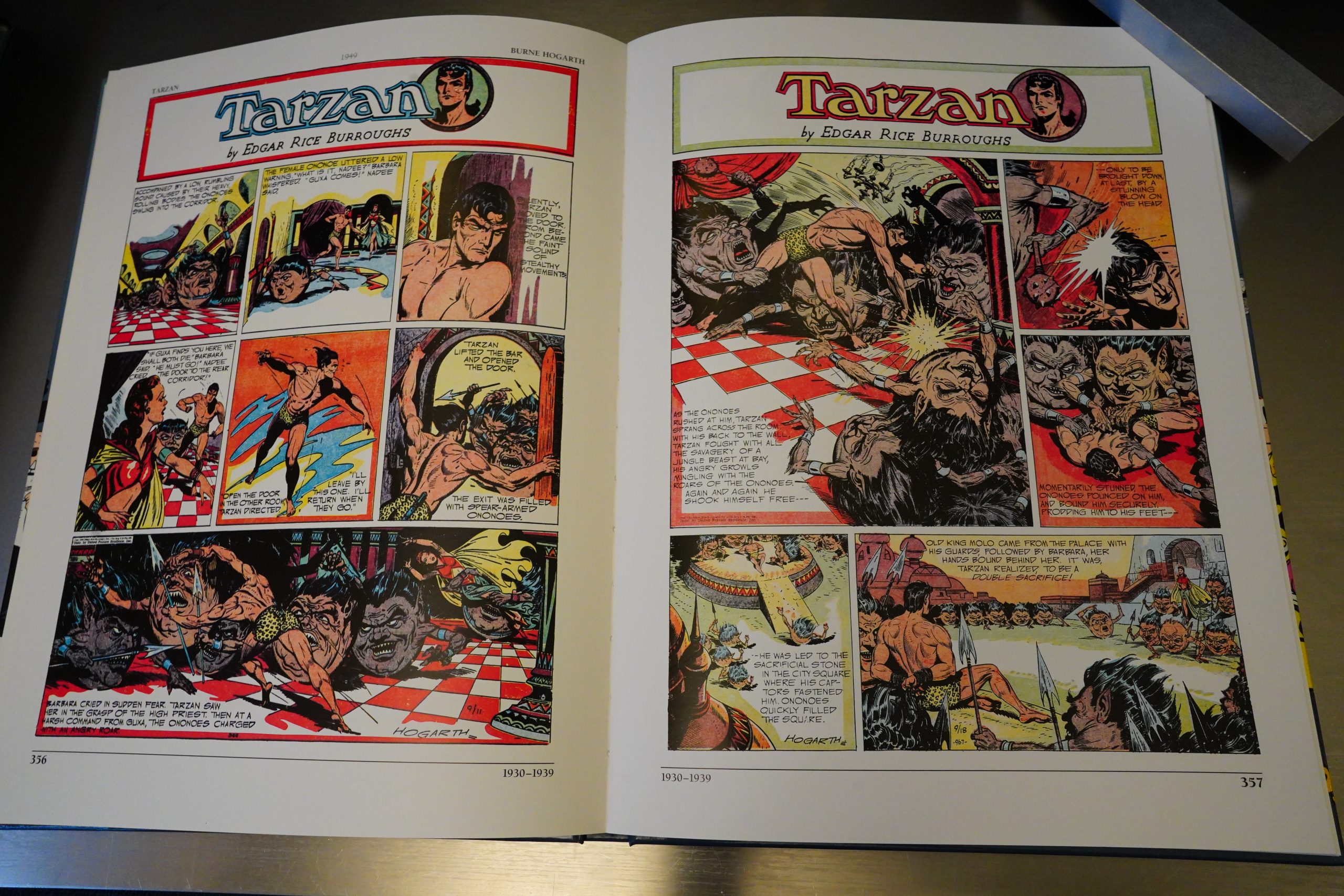

*gasp* I REMEMBER THESE PAGES!!! As a child, I had a huge (tabloid-sized) thick book that reprinted Tarzan strips, and this was one of the adventures included. Those creepy round creatures… I remember that the book seemed to come from not just a different era, but from a different world than our own. I was fascinated, and I was repelled, but I haven’t seen this for, like, four decades, and I still remember it viscerally.

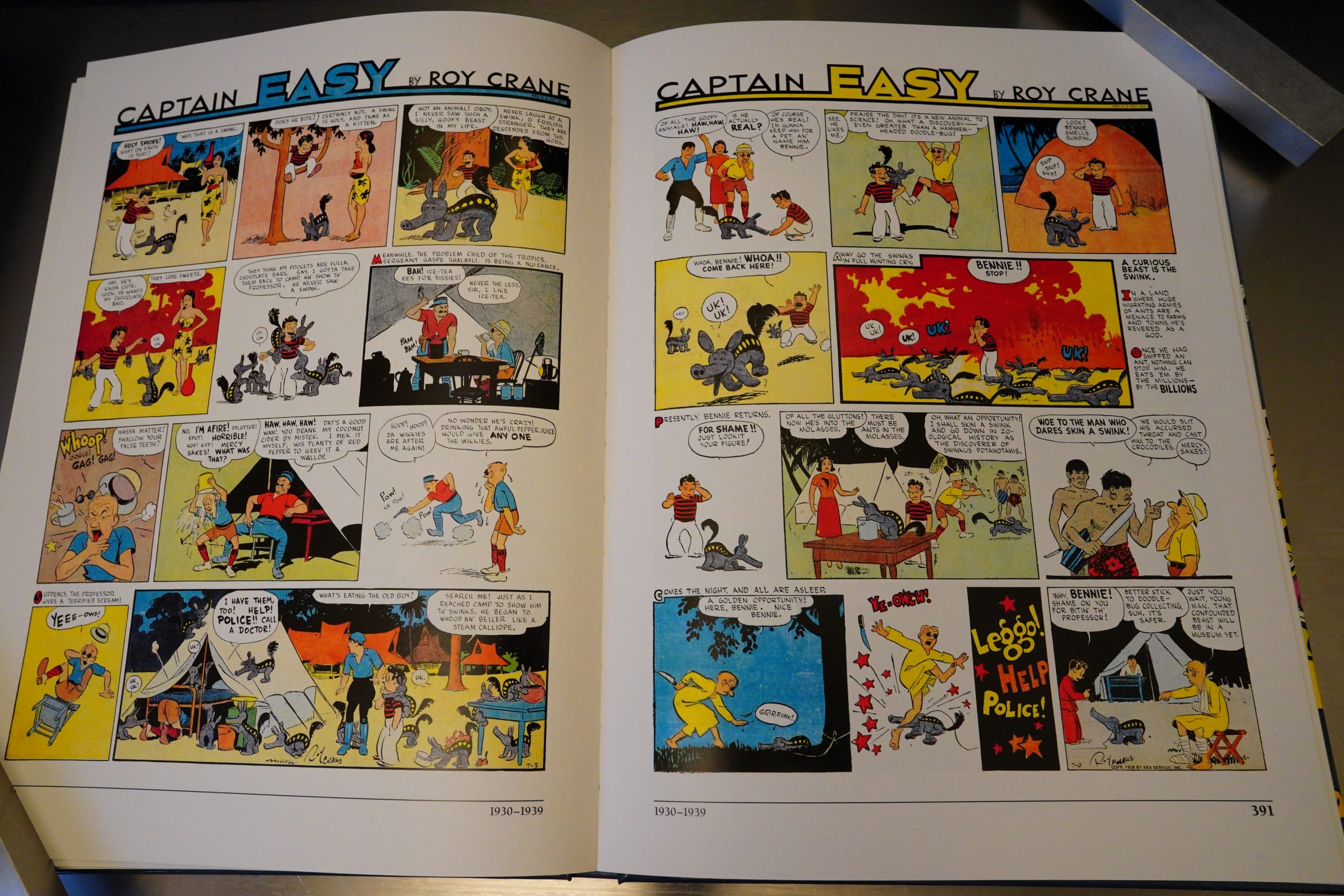

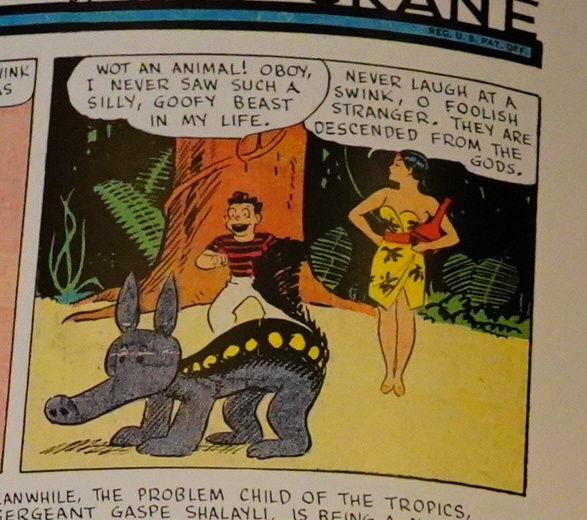

We do get one longer sequence of adventure-ish Sunday serials — Captain Easy by Roy Crane. It’s fun, but perhaps the reason they included it at such length was because it’s one series that hadn’t gotten a comprehensive reprinting?

And… does that Swink look suspiciously like Dave Sim’s early Cerebus design? It sure does.

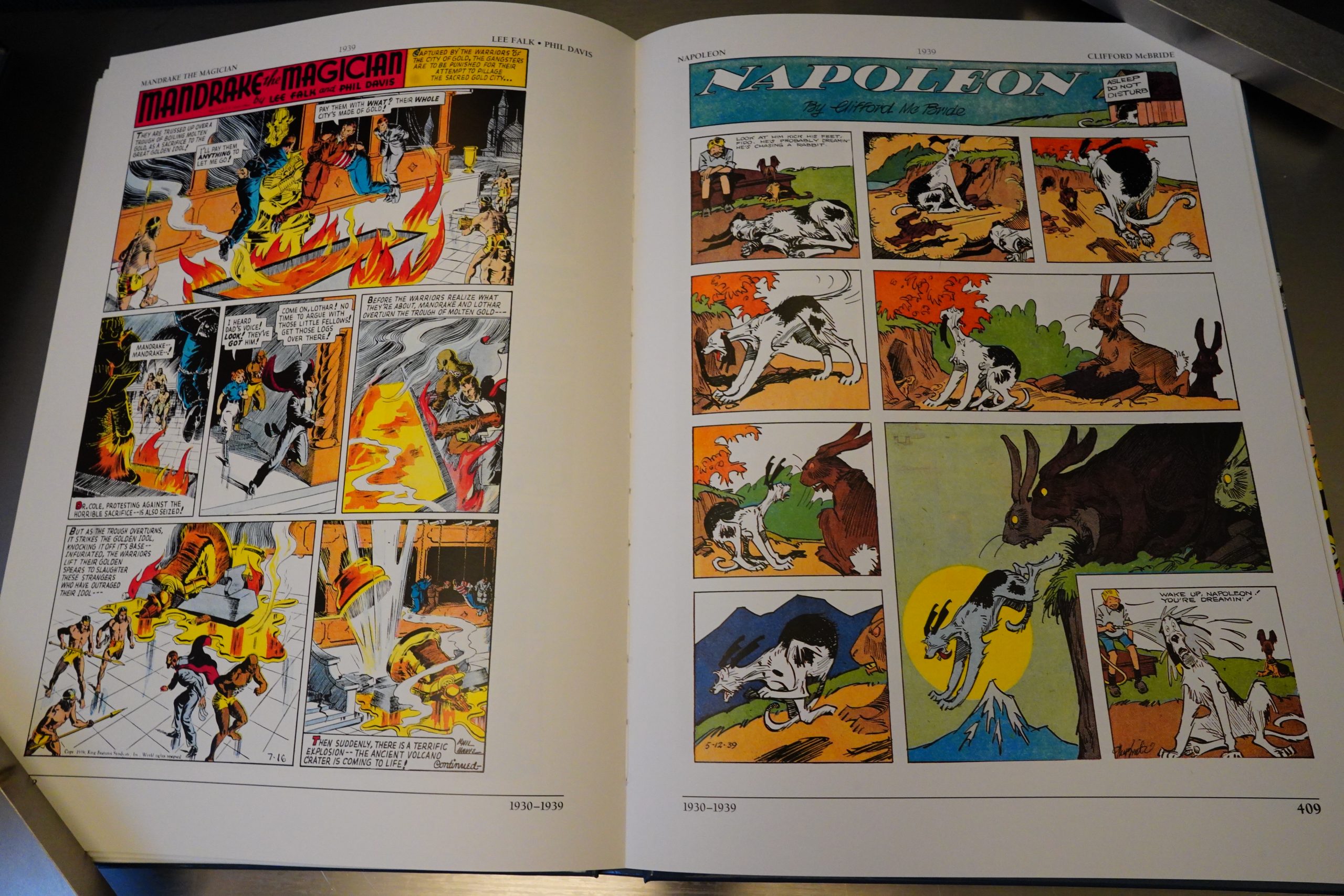

Again, reading this book is just one delight after another. So much stuff I didn’t know existed… not that I’d necessarily want to read these things in length, but it’s exciting happening upon these things here.

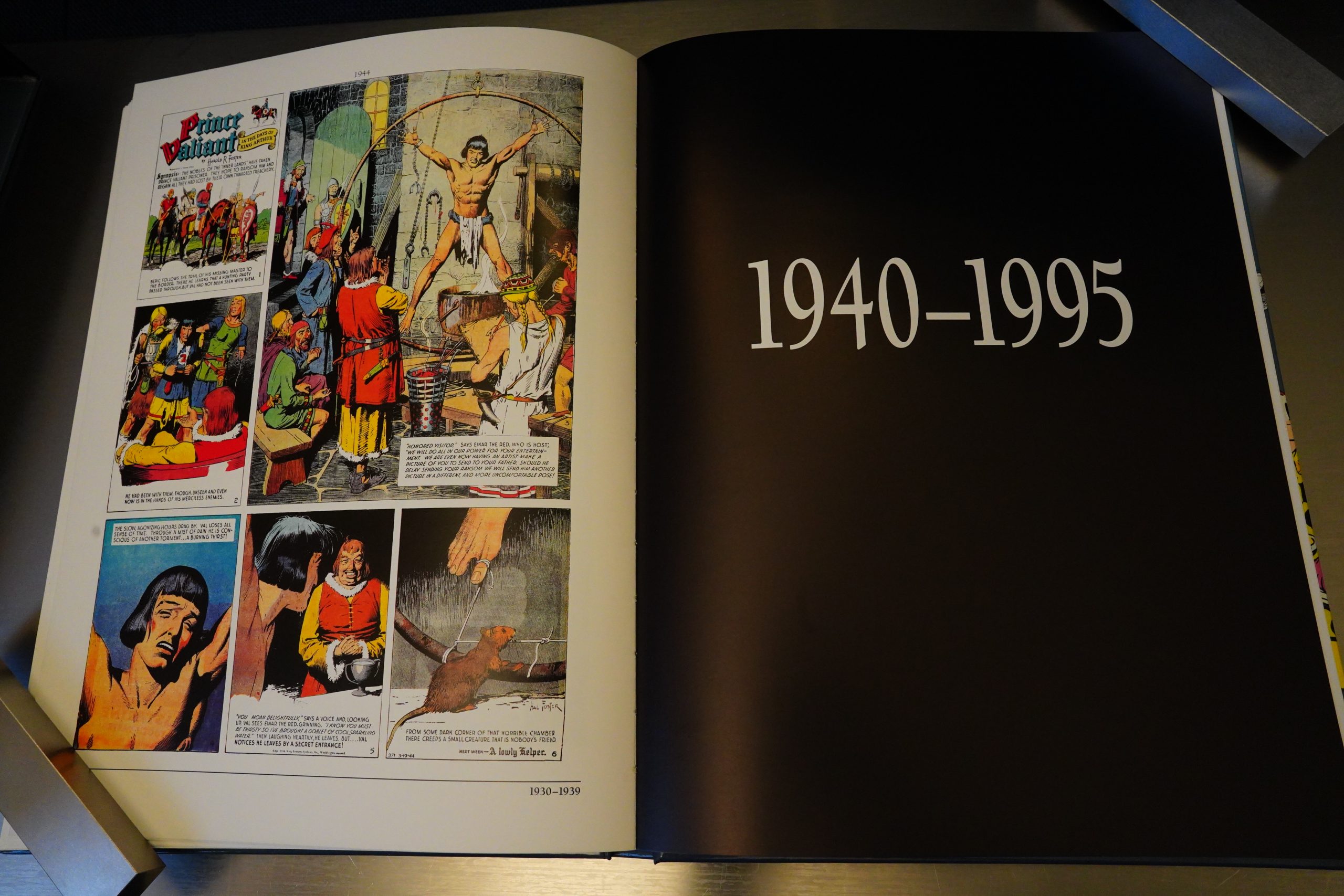

Nitpickers will probably find the book somewhat misnamed: We don’t really celebrate 100 years of comic strips — it’s all about the 1895-1940 period. But the final section takes us up to 1995 in one big gulp (and is the shortest section in the book).

So this section feels less compelling that the previous ones. Strips are represented with a page or less, and that’s not very readable. But I guess they sampled things mostly for graphical impact and/or historical importance.

Beetle Bailey gets four pages, for instance, which is pretty odd. Or was this book financed by Mort Walker’s cartoon museum?

These two pages cover two decades — 1972 to 1992. And weirdly enough, the only badly reproduced strip in the entire book is here — that Bloom County strip.

And in the 90s, we just get itsy bits. It’s understandable, but it feels off when the rest of the book is so meticulous.

And this is the final page.

So what can I say? It’s a wonderful book, and I didn’t expect that at all. It’s well-designed both for flipping idly through, dipping in here and there, and for reading straight through.

R C Harvey writes in The Comics Journal #196, page 37:

In hardback, is the resoundingly titled The

Comic Strip Century, edited by Bill

Blackbeard and Dale Crain. The project

was apparently Crain’s idea. A designer

and art director, Crain began plotting for

the book as long ago as 1990, he tells us;

he turned immedia tely to Blackbeard, who,

as Curator of the San Francisco Academy

of Comic Art (a sort Of crammed albeit

somehow orderly attic of moldering news•

print at the western edge of the city), has

not only great knowledge Of comic strips

but the vast resources of the Academy’s

collection to draw upon for the book’s

content.[…]

The KSP opus is elegance incarnate

in a slipcase, a two-volume extrava-

ganza (S 79.95, the pair), each volume

numbering a matching 240 pages (many

in color) and measuring 9×12 inches.

Slick, brilliant white paper and high

quality printing.[…]

Here’s a Happy Hooligan page in which

a parrot continually croaks “dark and

stormy night,” that line of picayune prose

from Bulwer Lytton that has been given

new life by Snoopy in Peanuts. And here’s

a Sunday Bringing Up Father in which

Maggie falls asleep and dreams of the days

when Jiggs courted her. And a Polly and

Her Pals page in which characters sing

“Barney Google with the goo-goo-googly

eyes,” the 1920s hit song that Billy Rose

wrote about Billy DeBeck’s comic strip

character. And, as a reminder, no doubt,

of the merchandising contagion that very

quickly infected the producers of comic

strips, here’s a Happy Hooligan page in

which the action is performed by toys and

dolls of Barney Google, Happy, Jiggs, and

Maggie. And finally, we have a sequence

from Mort Walker’s Beetle Bailey in which

Beetle goes home on furlough, and we

meet his sister Lois and her husband Hi,

both dark-haired at this time, but Lois

would dye hers when she became the co-

star of the feature that Dik Browne would

produce from Walker’s concept.

I miss, however, that Little Orphan

Annie Sunday page of May 17, 1942, in

which Harold Gray depicts Annie hanging

out the weekly wash as she prattles on

about the war and patriotism and so forth

in her inimitable fashion. In the conclud-

ing panel, Annie surveys the clothing she’s

been hanging up and says, “Hope some Of

the neighbors who’ve been crackin’ that I

have only One dress are rubberin’ now.”

Annie always wears a red dress, as you

may remember, and here Gray takes a

swipe at those of his readers who pitied

Annie because she seems to have only one

such garment. On the clothesline he dis-

plays a dozen dresses, all identical. All

red.

The presence of such in-group mate•

rial in Centuryraises questions about what

the editors of these volumes thought the

audience for this work might be.

While these little in-joke tableux are

undeniably a hoot for someone already

versed in the history of the medium to

discover, the uninitiated must remain come

pletely oblivious to their import because

Blackbeard has supplied no text from which

we might draw the necessary inferences.

The reticence of the editors is understand-

able, but it borders on the perverse.

The editors clearly wanted to give us

the enviable experience of seeing the comic

strip century unfold before us

uninterpreted. The great virtue of these

books is their primacy: they print the

evidence, the very artifacts. Thk is one of

those rare occasions in the scholarship of

the medium when we are the eye wit-

nesses. We can see with our own eyes the

evidence upon which the history of the

medium rests: to assess the quality or

importance of a given work, we need not

rely, for once, solely upon the testimony

of someone else, someone who gargles up

a verdict after staring into a microfilm

reader for hours and hours.

Indispensable as it is to have material

like this available in book form, the use•

fulness of the books could have been

greatly enhanced if the history underpin-

ning the selections as well as the in-jokes

were rehearsed herein.

*gasp* No, can’t have jokes go unexplained. Uninterpreted reading! Well, I never! *clutches pearls*

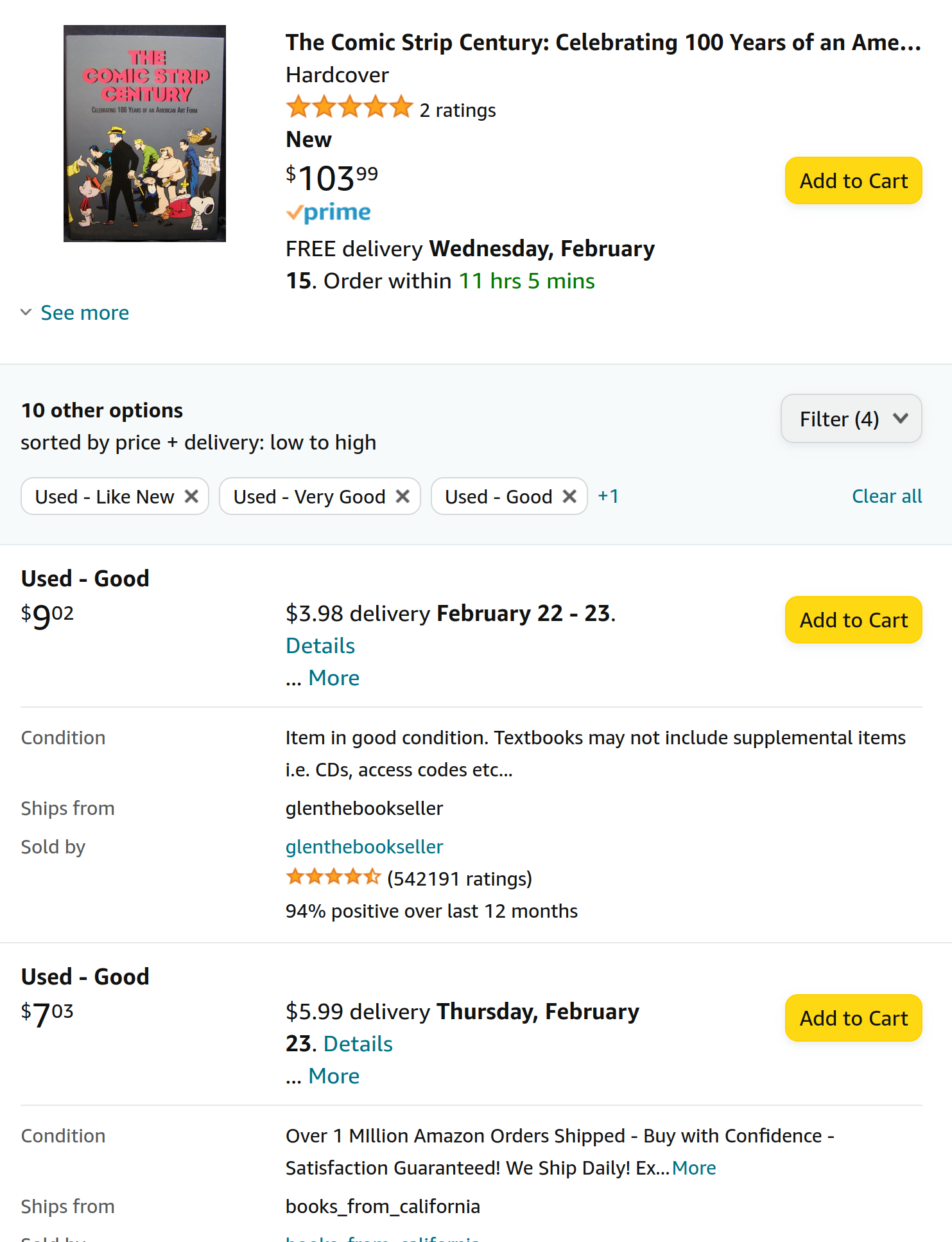

You can apparently pick up this book for next to nothing used, so I guess this means that they printed quite a lot of copies. Pick up a copy and enjoy an unmediated evening with some great comic strips.

This is the one hundred and seventy-eighth post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.