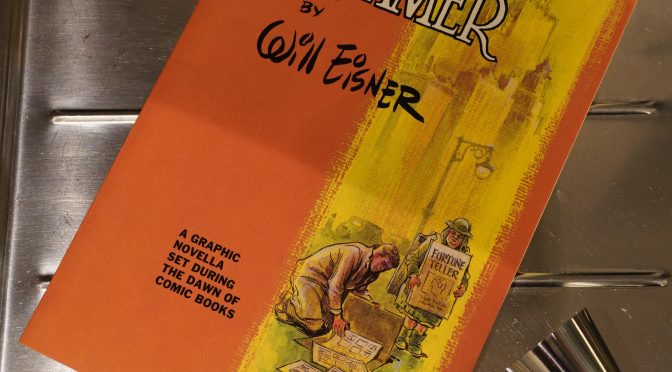

The Dreamer (1986) by Will Eisner

I get that back in 1986, nobody knew how to sell comics to a literate audience — but this book is obviously trying to appeal to people who quite liked A Contract With God (which had, finally, been quite a commercial success). So they go with a thinner format… on very white paper instead of a solid book paper stock… indifferent typography… and instead of a brown, serious cover, they go with… orange an pee yellow.

I mean, c’mon.

C’mon.

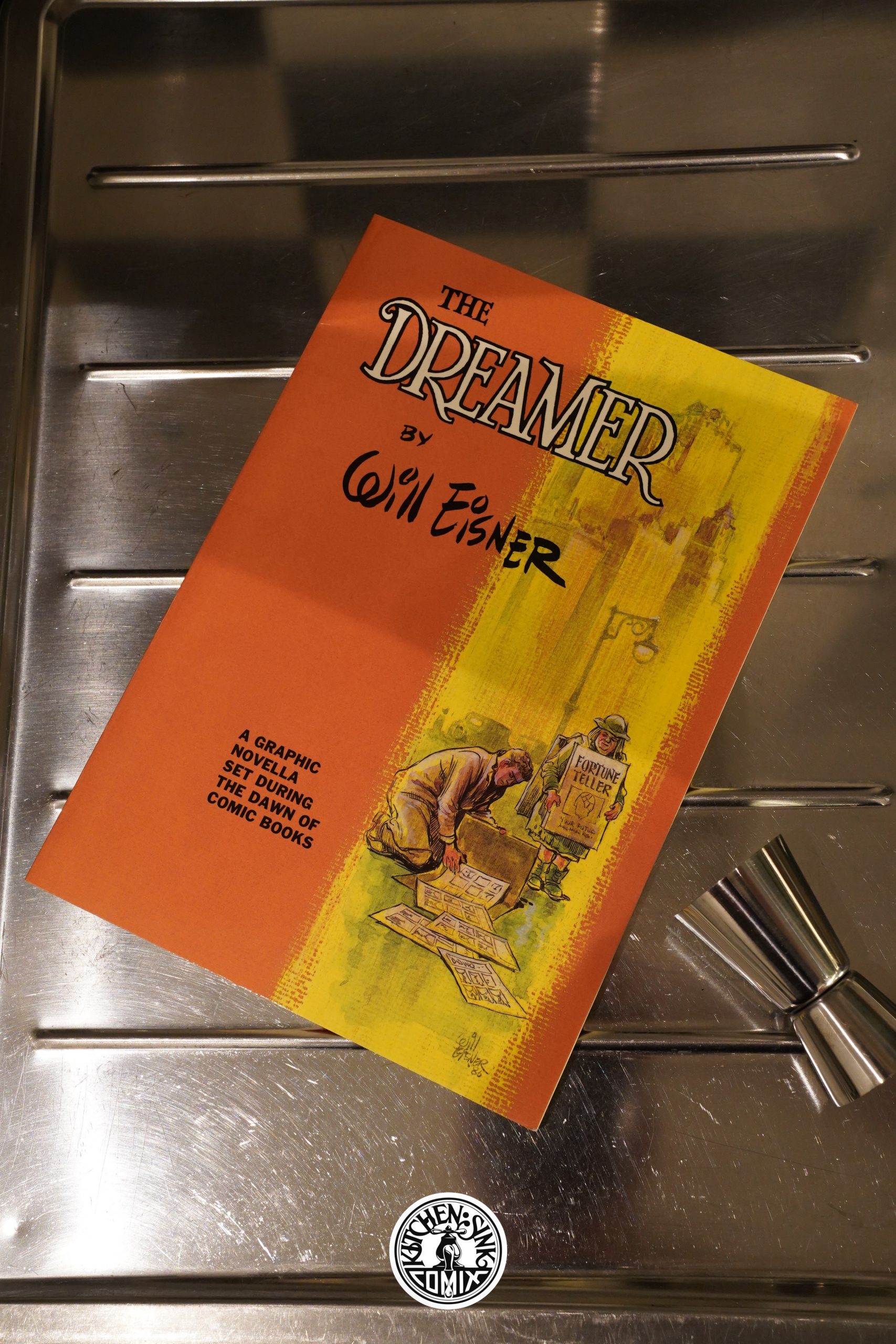

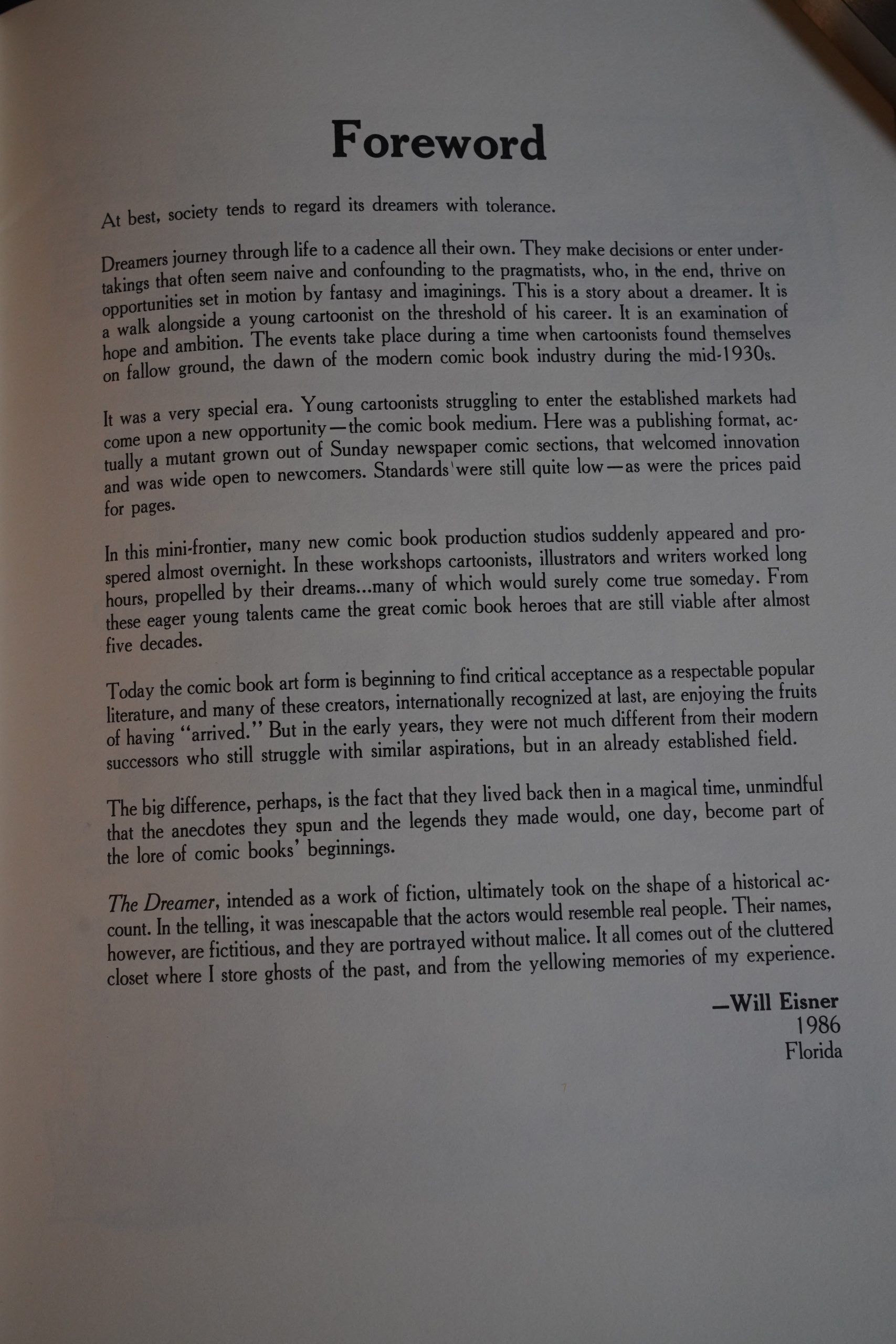

Eisner explains that he set out to do fiction, but it ended up being anecdotes from the start of his professional career instead (I’m paraphrasing slightly).

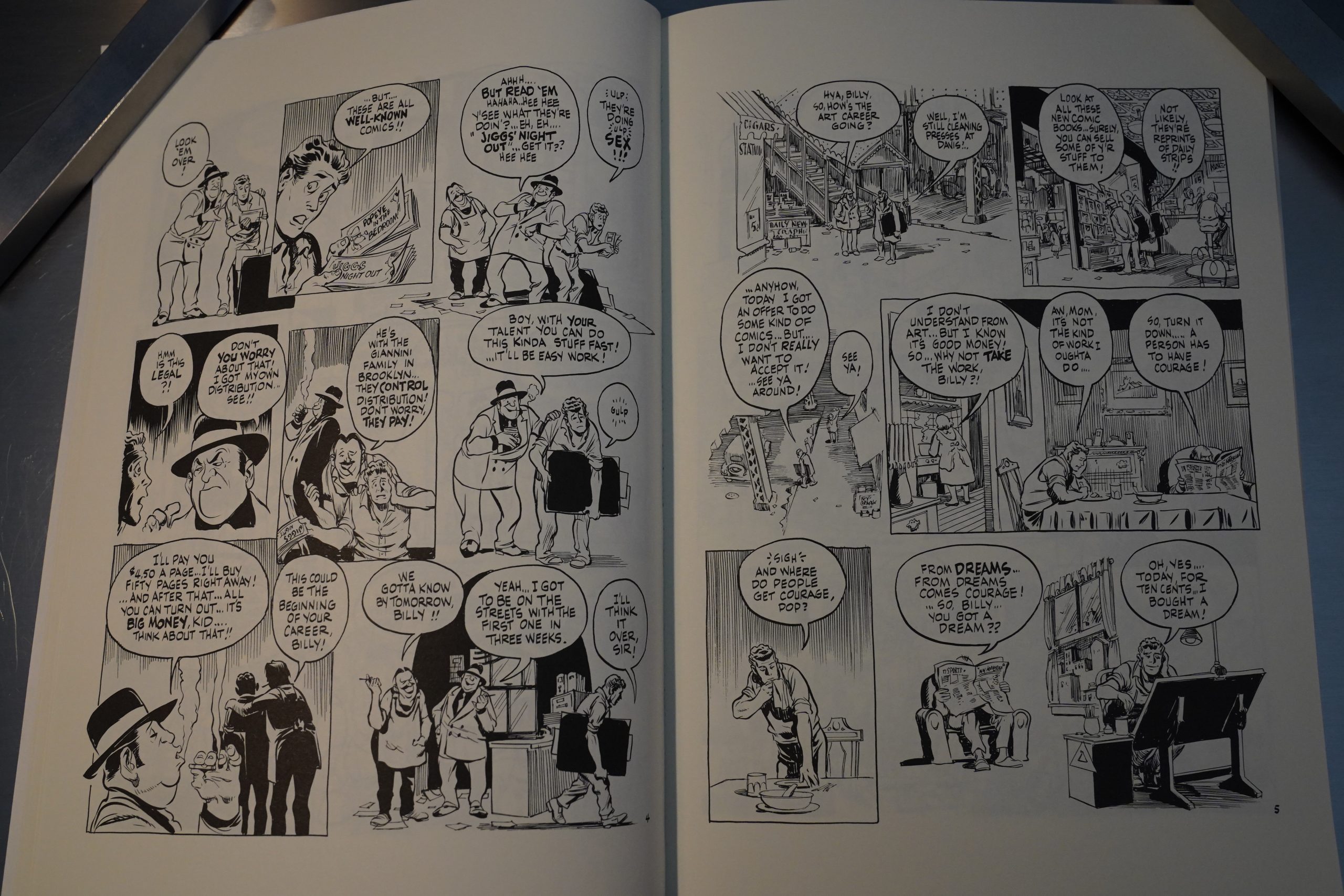

And some of these anecdotes are kinda interesting — like when the mobster wanted him to do porn comics. He turned them down, because… he’s such a dreamer.

Yes, that’s the leitmotif here, and he sticks it in so many times that it’s wince inducing.

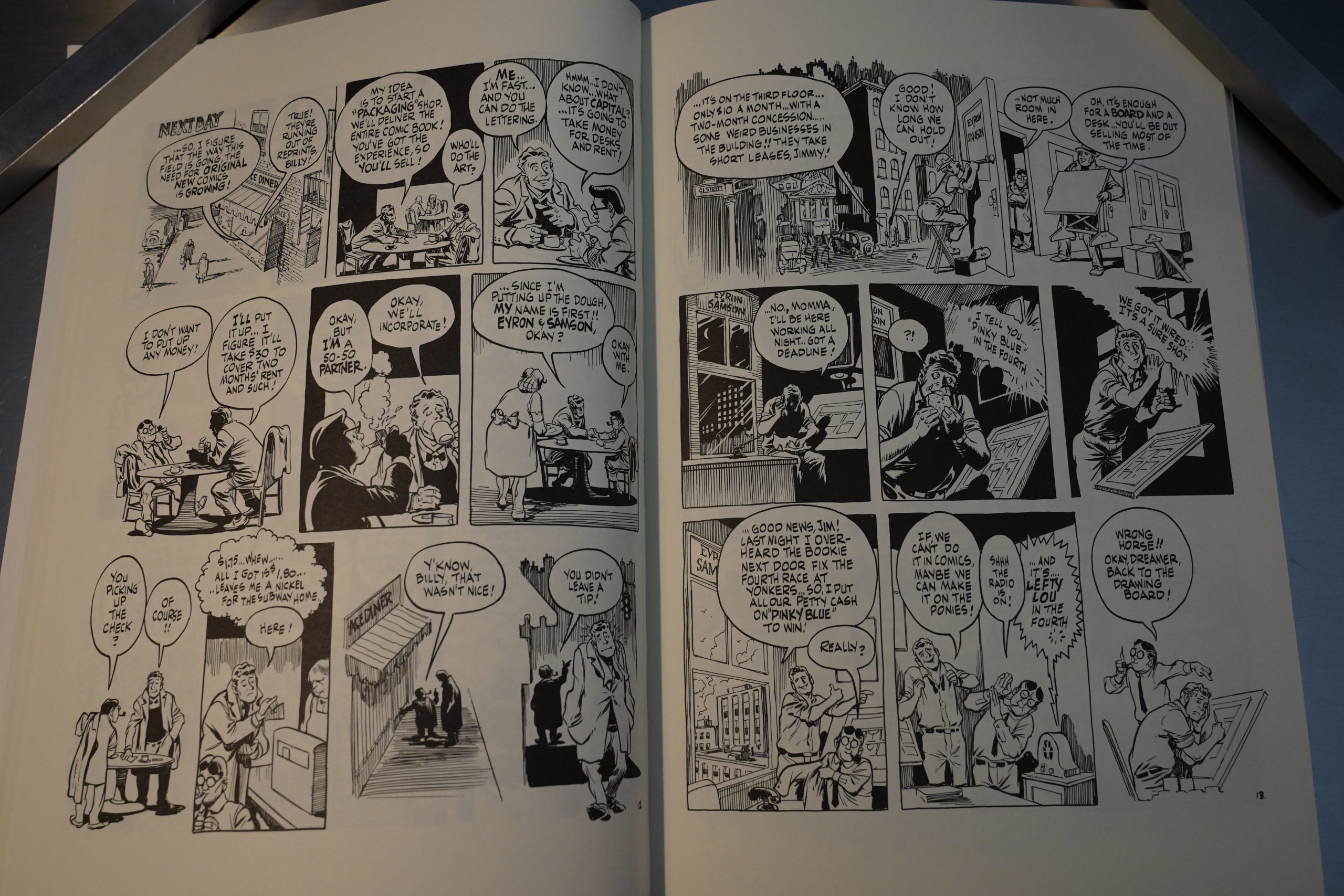

(Ibid.) I also don’t understand why he’s insisting on not using people’s real names — Eyron & Samson instead of Eisner & Iger. It surely can’t be because he thought anybody’d be offended, because he treats all of his close associates with loving care. Nothing untoward is revealed or even hinted at.

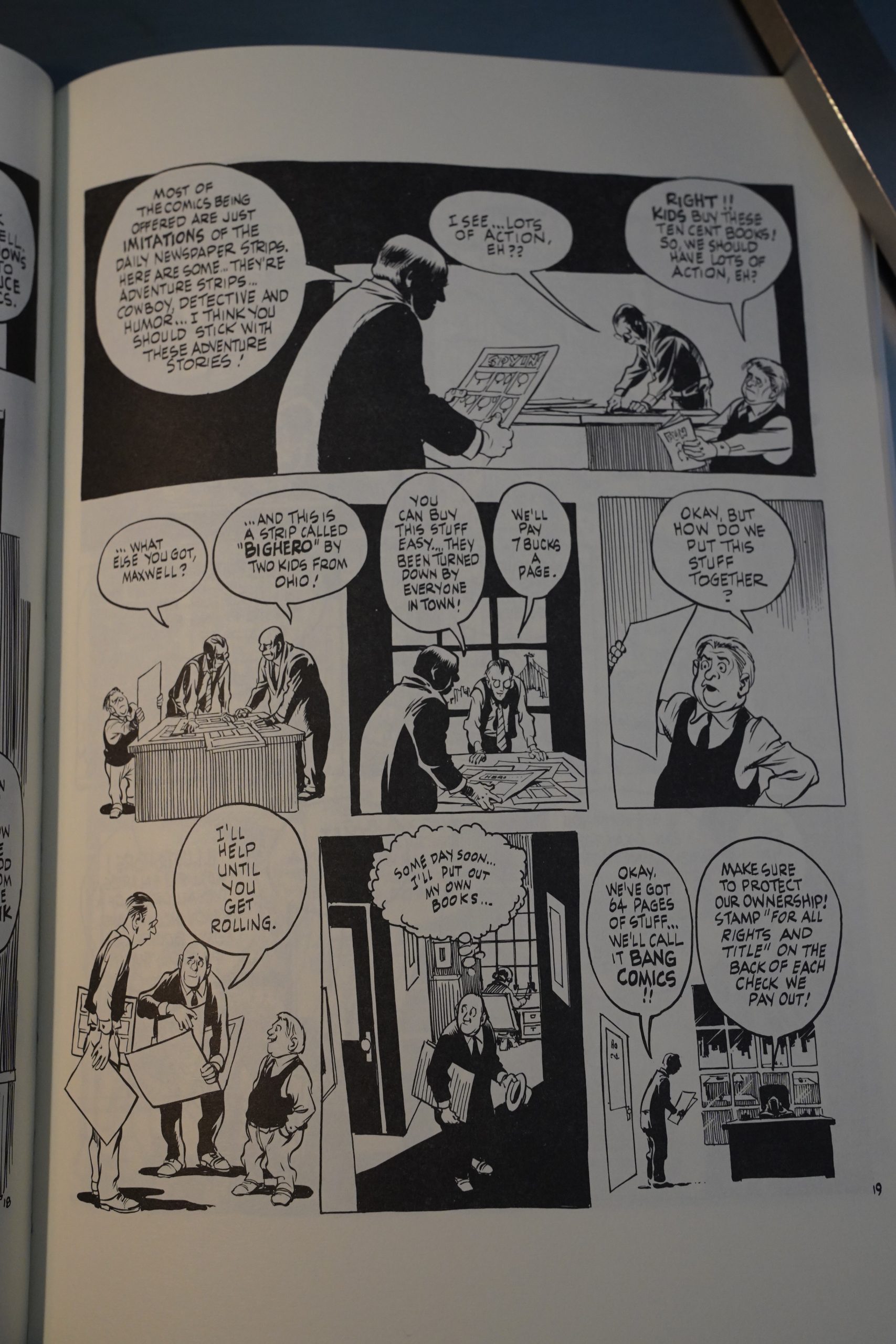

The least successful parts of the book are when he diverges from telling his own story: Here’s when DC buys Superman off of Siegel & Shuster. (I’ve got a decoder ring.)

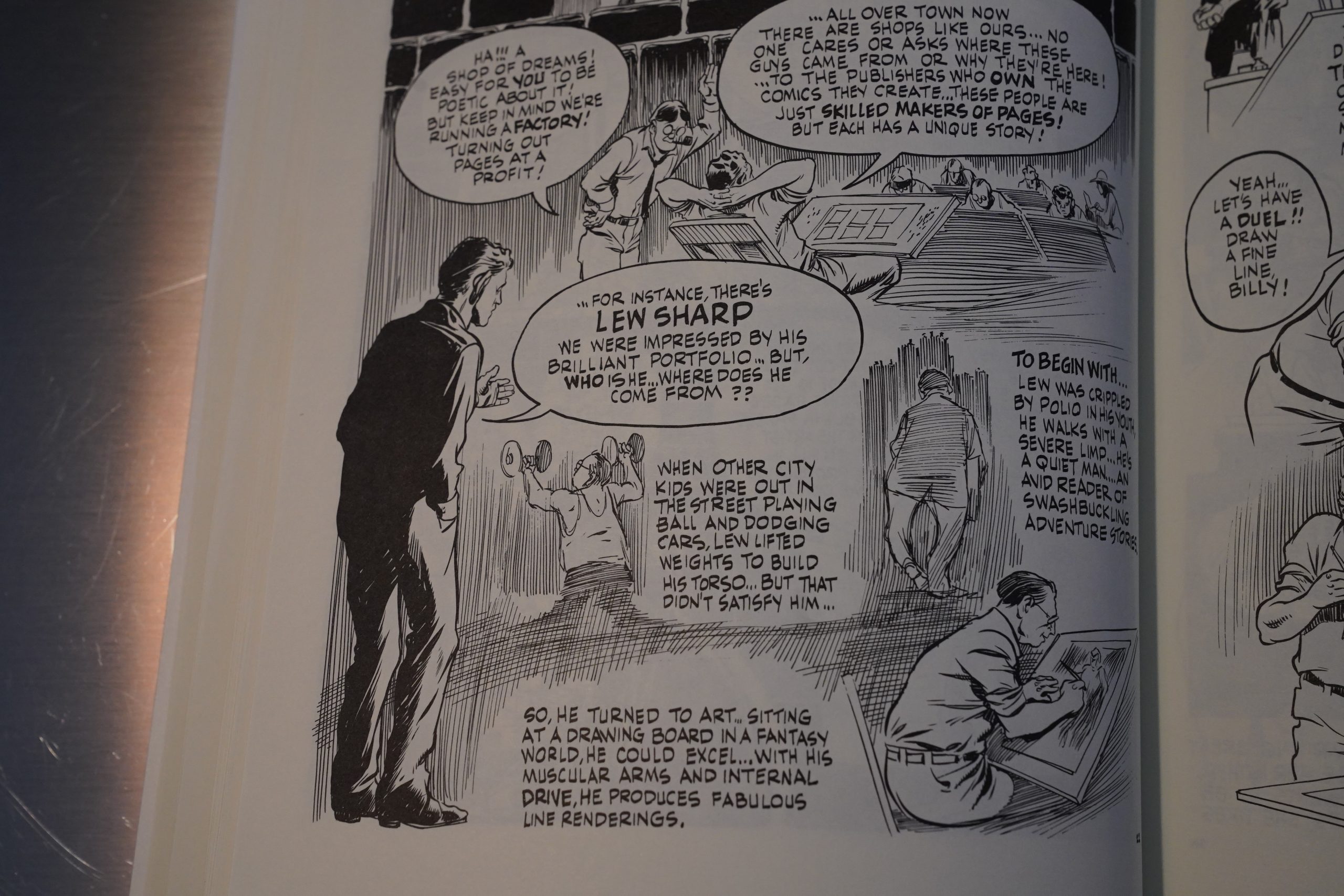

The book doesn’t really have that much of a flow — it’s just a bunch of anecdotes, and the storytelling is really, really clear.

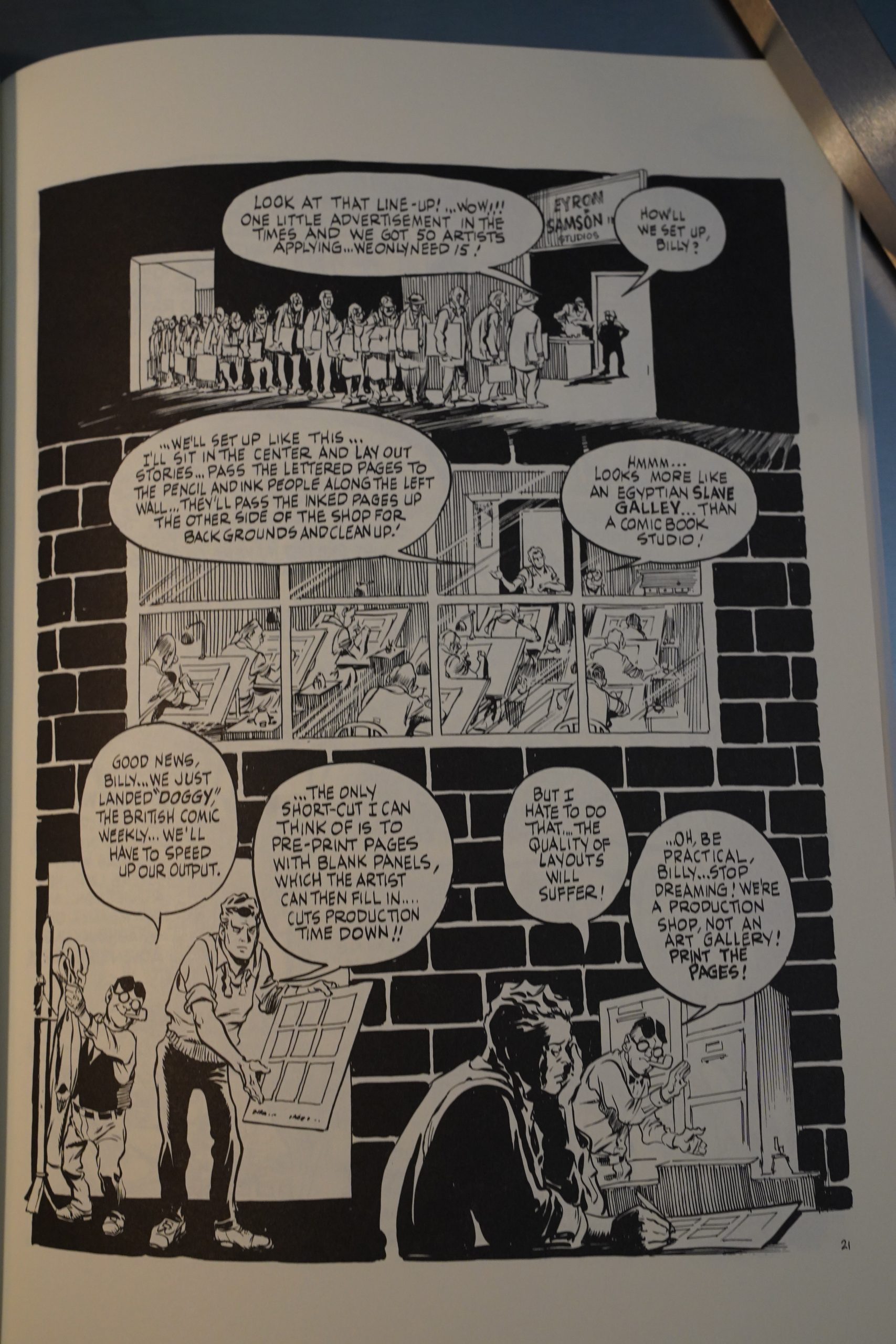

Eisner & Iger set up a production line for pumping out comics in the 30s — and despite calling it a slave galley, he portrays himself as a softie, while Iger cracks the whip (but gently). I think people who worked for Eisner at the time disputes this slightly.

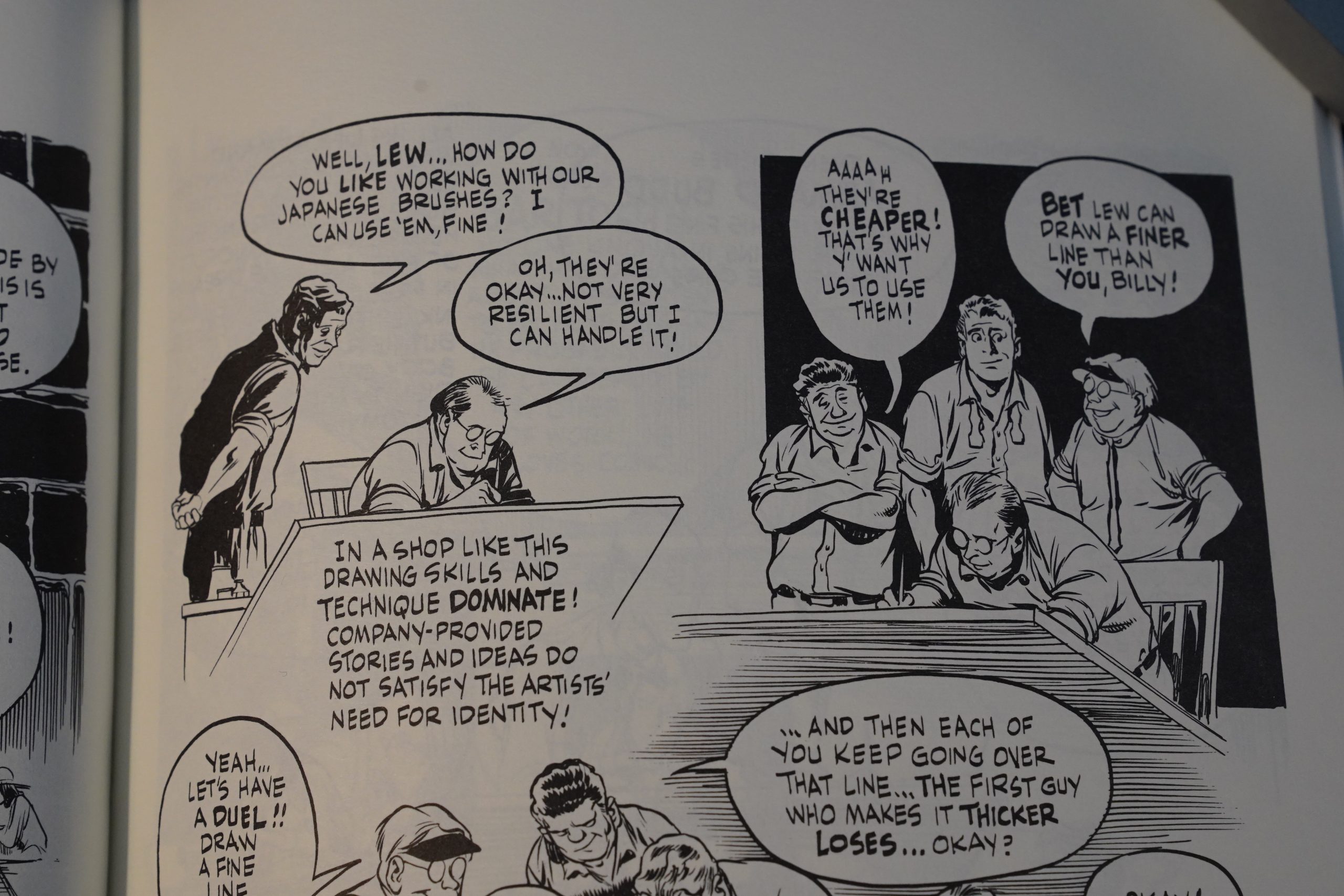

There’s a whole section where he summarises a few of the people who used to work for him in a very sentimental way. Here’s “Lew Sharp”. Let’s see if you can guess who that is:

“I can use ’em, fine!” “Bet Lew can draw a finer line than you”.

Yes. Yes, you guessed it. Lew Sharp is : Lou Fine:

Either at about age two or in his early teens, Fine’s left leg became crippled by polio.

This is about Eisner creating a knock-off of Superman as Fox Feature Syndicate’s Wonder Man:

DC sued and they lost money on that project.

And then Eisner’s offered the Spirit newspaper insert, and the book is over.

It’s not that this is a bad book — but it’s so unstructured, and much of it just feels… dishonest? He’s all that portraying himself, a (by all counts) shrewd businessman, as a hapless dreamer, and that makes for a raised-eyebrow reading session.

But I mean, it’s fine? But there’s a reason it didn’t make a splash like A Contract With God did, and it’s not all about the design choices for the cover.

Gary Groth writes in The Comics Journal #119, page 7:

The elements of Eisner’s Spirit that were

acceptable in that context have become an

Obstacle to the serious aims in Eisner’s more

“mature” work. The sentimentality that

• •humanized” the Spirit stories was offset by the

humor: in Eisner’s new work there is no room

for humor. only sentimentality. When all this

Hollywood schmaltziness is placed in a serious,

indeed stridently “literary” endeavor, it mere-

ly becomes obnoxious.

Eisner’s previous “graphic novella,” ne

Dreamer. is less stilted and mechanistic and

more engaging than The Building, but its failure

is on a grander scale given its potential historical

significance. lhe Dreamer is Eisner’s recollec-

tions of the early years of the comics industry

and his participation in it, told in narrative form;

it is an act of memory and, perhaps more im-

portantly, an opportunity to reconcile, with

historical reality. It is a failure in my view

because one of the essential prerequisites of a

memoir, even one told in fictional form as The

Dreamer is, is a ruthless self-examination of the

author’s own role, and whenever such self-

examination becomes crucial to the truthful

realizÆtion of the work, Eisner fudges or evades

or coyly deflects the reader’s attention through

clever narrative sleights of hand. Graham Greene

once wrote that there is a chip of ice in every

writer’s heart, by which he meant not that a good

writer must be without compassion, but that he

must be merciless in his pursuit of the truth.

Eisner is not.

Let’s get the predominantly literary quibbles

out of the way first. The theme of the book is

the role of the dreamer in the cultural milieu

of the comics industry circa approximately 1938

or ’39. This is the first problem. Why does an

autobiographical work have to have a Theme at

all, and why as tendentious a theme as this, one

that is shoved in the reader’s face as often as

possible? In case the title itself isn’t heavyhanded

enough, characters refer to dreams or dreamers

40 times in this 46-page story. Theme is one of

those facets of literature the young student learns

in a freshman literature course, which helps to

simplify the complexities of good writing by the

use of categorization. (This undoubtedly makes

multiple choice tests easier for teachers to put

together). I have a feeling that someone once told

Eisner that every book must have a theme,

because Eisner cannot do without a theme

however supererogatory it may be.

This brings up another difficulty; the title of

the book is The Dreamer, singular, but the story

is clearly about dreamers, plural. We may infer

that the title refers to the Eisner character since

he is centerstage and the character most often

referred to (and most often referring to himself)

as a dreamer. but the story stresses the univer-

sality of dreamers, which makes the choice of

a singular rather a plural an odd, even egoistic

one. This could be dismissed as a sloppy over-

sight, but for the fact that the sloppiness extends

to the inconsistent and confused use of the theme

throughout the book. As I’ve pointed out, the

words dream or dreamer are used 40 times in

the book. They are usually applied to artists and

usually as terms of approbation even when they

are used sneeringly by a more pragmatic,

“realistic,” disgusted, or frustrated character

(usually a businessman) to describe an artist

(usually Eisner) whose motivations aren’t wholly

economic or materialistic. 0K. , this uould be

trite and cliched, but at least it would be consis-

tent. But, the terms are also used to describe

rapacious publishers, therefore universalizing the

term to refer not merely to aspiration or idealism,

but to naked greed and wanton ambition as well.

This robs an already precariously sentimental and

romanticized title of what meager moral

resonance it might have.

In one panel a printer who has previously been

portrayed as an avaricious opportunist screams,

“Publishing! I’ll be a publisher! .. .Yeah, now that

is a dream I’ve always had.. (This is Donald

Harrifield who represents Harry Donenfeld, who

bought out a small comics publisher and started

National Periodical Publications (DC) in 1937).

The comics publisher who has been squeezed out

of business by Harrifield casually shrugs,

“Publishing was just a dream.” Previously, the

dreamer is consistently portrayed as a noble out-

sider, alienated by the vulgarities of commerce.

Earlier in the story there is this exchange:

Eisner’s father: “A person has to have

courage!”

Eisner: “(sigh) And where do people get

courage, pop?”

Eisner’s father: “From dreams.. .from

dreams comes courage!”

And apparently, from dreams comes inbecility,

vulgarity, and greed, though these polar defini-

tions Of the dreamer are never investigated within

the story. This could have been an opportunity

to explore the differences in motivation between

such dreamers (if Eisner is going to insist that

they’re both dreamers with dreams) and draw-

ing conclusions, or at least asking questions if

drawing conclusions is too much to ask for, as

to the values of the respective dreamers. But, this

isn’t done. The cover and title clearly refer to

Eisner: the cover painting is of a young Eisner

with an art portfolio with a fortune teller in the

background (get it?). The printer-cum-publisher

who refers to himself as having a dream is con-

sistently portrayed as a loveable cartoon rogue,

flailing about humorously and exaggeratedly

whenever seized by a frenzy of greed. This is

as penetrating a portrait as Eisner paints of such

a man. One doesn’t have to see men like this as

harshly as I do, as accomplices in the murder

of an artform, as having surrendered their cons-

ciences to the lure of economic gain, to be of-

fended by this lame, morally vacant portrayal.

Yup.

Stuart Hopen writes in The Comics Journal #116, page 79:

The Dreamer, like Eisner’s other

recent work, does not provoke

dreams. Nor is it mainstream fare

that massages deeply held cultural

values. Here, Eisner joins Harvey

pekar and Art Spiegelman in using

blatantly autobiographical material

as the basis for a graphic story. But

The Dreamer is coated by a thin

veneer—a very thin veneer—of fic-

tion. The protagonist’s name is

Billy EyrOn. He is the co-owner of

a comic sweatshop where we

meet artists such as Jack King, a

short, tough, cigar-smoking street

kid, and Lou Sharp, a superb

draftsman who was crippled by

polio. This renaming Of familiar

people creates an odd distancing

effect, a curious mirror image of

the effect created by Art Spiegel-

man’s metaphorical use of animals.

(Eisner might have portrayed

dreamers as mice, realists as cats.

A character named Vincent Rey-

nard, a publisher, could have been

a fox.)

This renaming also creates an air

of intimacy. Those familiar with

the history of comics will recog-

nize most of these characters and

events. Surely, no one else will.

The intended audience seems to be

the industry itself. For those with

insider’s knowledge, the story

resonates with folklore charm.

Take for example a contest between

Eyron and Sharp in •which they

compete over the tracing Of a

straight line. This is the stuff Of

legends to insiders—a clash

between giants Of the medium. To

the general public, it would seem

trivial. And for those who know

the medium, Eisner takes us back

in time with a g,rave Of his brush,

using a crisp, clean line reminis-

cent of his earlier uork, and a

seven-to-ten panel per page layout

that’s reminiscent of old pulp

comics. There is a sense that

Eisner is sharing intimate family

secrets, like a patriarch sitting

down with his nouveau riche pro-

geny, reminding them of their

The first comics we see in The

Dreamer are pornographic works

that pirate famous syndicated

characters, an obvious reference to

the scandalous eight-pagers of the

time. It is a powerful suggestion

that, at the time of its birth, comics

was a gutter medium, an undeserv-

ing and illegitimate brother to

newspaper strips. The first major

comics company we see, Harri-

field, began with minimal aspira-

tions. A printing company is in

trouble because its pulp producing

customers are going out of busi-

ness. The company reasons that if

they publish comics and make only

enough to cover printing cosß, they

will still have made a bottom line

profit.

Robert Haining writes in The Comics Journal #121, page 25:

One could forgive much of this if The Dreamer

had the accuracy of a work of non-fiction. While

I am no expert, I know Of one instance where

Eisner misrepresents a situation by omitting im-

portant facts. When the Victor Fox character

wants Eisner to do a blatant rip-off of Super-

man and Eisner expresses reservations, his part-

ner, the Jerry lger character, brushes aside his

doubts, stating that he thinks that Fox is a “big

shot.” Eisner describes the debate with lger

much differently in Panels #1, “We discussed

it, and lger said, ‘Well, there’s really not much

we can do about it. It’s his magazine and he’s

asking for this and we’ll do it for him.’ I wor-

ried about it, but lger made a very convincing

argument, which was… that we were very

hungry. We needed the money badly [emphasis

Eisner’s].” Eisner does not bring this up at the

time the Fox character approaches them since

they have to use methods to speed up produc-

tion. By leaving the financial situation out of the

book, Eisner gives us the impression that lger

was blinded by greed when he was trying to be

practical. It is not enough that writers give us

the facts. Facts must also be presented in the pro-

per context. This is what Eisner fails to do in

this case.

Dale Luciano writes in The Comics Journal #117, page 53:

An extremely pleasant surprise was

Kitchen Sink’s second notable release,

Will Eisner’s The Dreamer, which sub-

titles itself ‘ ‘A Graphic Novella Set Dur-

ing The Dawn of Comic Books.” This is

a charming, modest, nostalgic account of

the formation of the comic industry.

As told by an artist of substantial repute

who played a key role in the creation of

this distinctively American industry, it

takes on the significance of a historical

document. It is also transparently

autobiographical, so it has a wonderful

lived through this—can you believe

it?” quality, and we have the privilege of

watching one Of the medium’s masters

look back and reminisce about his own

role in history. I found it enormously

entertaining.

Did I use the word “nostalgic?” The

Dreamer evokes the image Of an industry

founded by quick-buck entrepreneurs furi-

ously intent On exploiting a lucrative fad

which, many of them suspected, might

quickly slide into the same extinction as

the pulps. Among its virtues, : The

Dreamer captures a sense of this indus-

try’s divided soul. Its chief product, fan•

tasy, was cranked out by a stable of

dedicated, eccentric, variously talent art-

ists, all of them conscious of their own

exploitation at the hands Of publishers.

Eisner has no special axe to grind. While

he does not deny the crassness Of the

shysters and opportunists who float in and

Out Of the story, they are depicted, Often

with real comic grace, as archetypal

American hustlers and con artists. And

the artists are depicted, with affection and

respect, as distinctive American types as

well—men and women struggling to hold

on to the dream of “making a living as

an artist” while they sell their skills as

craftspeople.

On a different and more personal level,

The Dreamer is an autobiographical

excursion into the past, revealing how

Eisner remembers himself living through

the episodes depicted and how he feels

about those years. There are so many

wonderful images in The Dreamer that

beautifully express the trials of the cen-

tral character, “Billy.” In One sequenfe,

we watch him. timid and fearful Of deep-

ened involvement with a young woman

whom he’s too shy to kiss goodnight, walk

forlornly and alone through the rain. In

both the writing and art, Eisner captures

a powerful sense of Billy’s simultaneous

confusion, humiliation, and determina-

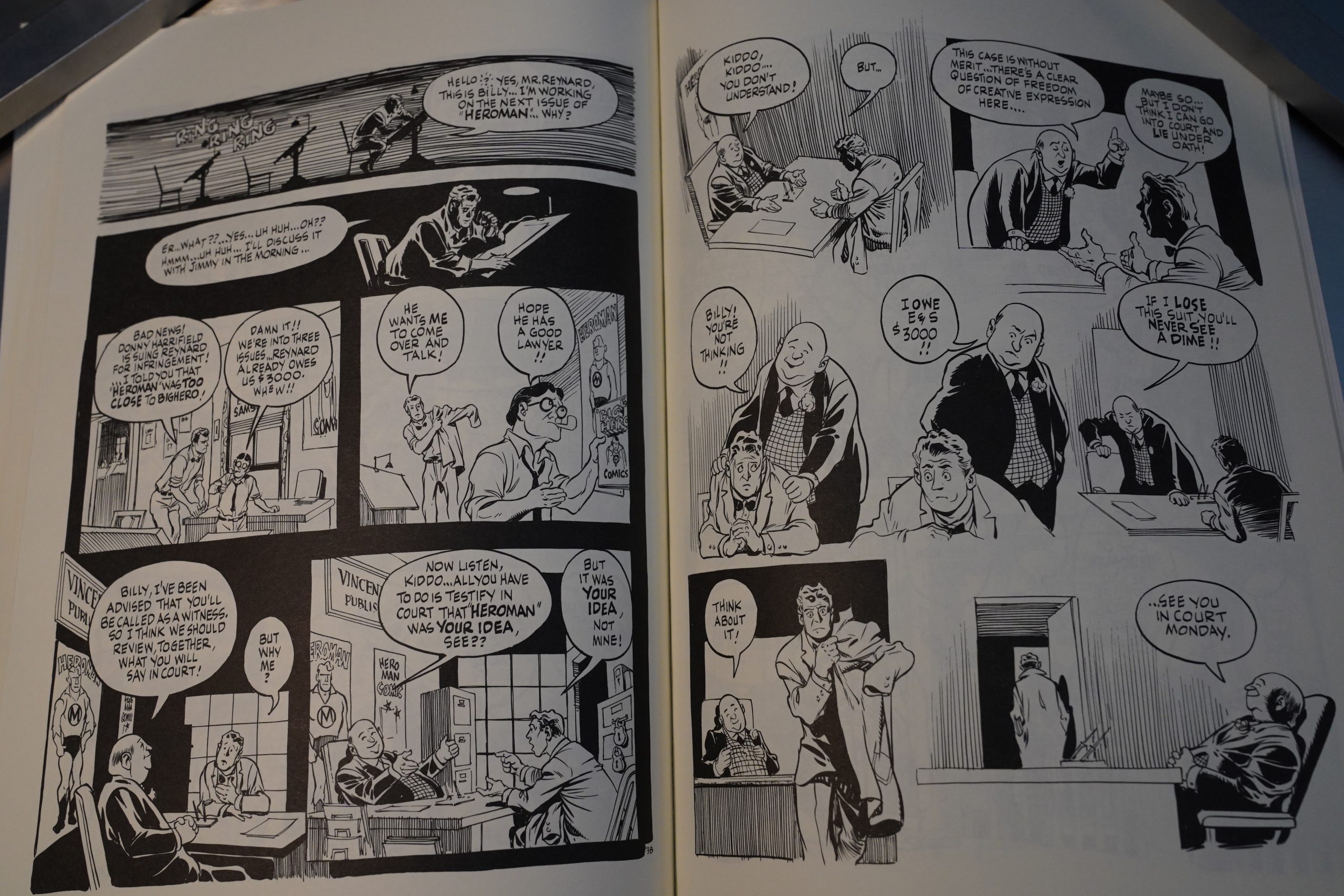

In another—an episode based on the

well-known Captain Manel plagiarism

suit—ue watch Billy struggle with the

dilemma Of whether to maintain his in-

tegrity and tell the truth on the witness

stand and lose $3,000 in the process, or

lie. (Yes. he learns that integrity can be

expensive.)

The Comics Journal #121, page 37:

He pulls this same Stunt with The Dreamer by

claiming that it isn’t an autobiographical work,

but a fable. How does Jones justify this seman-

tic revisionism? ‘It’s a work of wry, affectionate

commentary on the human condition, set in a

particular historical moment and utilizing

caricatures based on real people.” How this

relieves Eisner of an obligation to historical

accuracy and artistic truthfulness is not exactly

explained. Jones’ contempt for historical

accuracy and artistic forthrightness is further

demonstrated by his contention that “Eisner’s

own background is of no consequence. He can

rewrite whatever he wants, so long as it’s fic-

tionally effective.” No “essential prerequisites”

here, not even a respect for history; any writer

can distort an obviously historical work as long

as it’s “fictionally effective.” For Jones, anything

goes.

Jones acts as though The Dreamer were a

thriller or an adventure Story in which I found

a plot hole; even purely fictional work should

be held to some standard of historical accuracy

to the extent that it uses history; an autobiography

by its very nature has to be held to a higher

standard.

The idea that The Dreamer is not an auto-

biographical account is pure nonsense. It is worse

than nonsense, it is sheer deception. Eisner

himself in the introduction to the book writes,

“The Dreamer, intended as a work of fiction,

ultimately took on the shape of a historical ac-

count.” The book, Eisner continues, came out

of his own “experience.” Eisner is quoted on the

back cover as saying that The Dreamer ‘ ‘is in-

tended as a kind Of graphic historical novel set

in the primordial dawn of the comic book

industry,” the operative word being historical.

In Jones’ own cliche-ridden review Of the book

in Amazing Heroes, he wrote: “Beautiful, funny,

bittersweet, and illuminating, this is the sen-

timental gentleman of comics, the master of the

intimate human story, fondly recalling the early

days of the funnybook. Few people experienced

those days like Will Eisner, and nobody could

relate them half as well.”

But, as it turns out, Jones doesn’t care if Eisner

related his experience in those days or not since

Eisner “can rewrite whatever he wants, so long

as it’s fictionally effective.” And since, accord-

ing to Jones, The Dreamer was based upon

Eisner’s experience, how can Jones write that

“Eisner’s background is of no consequence?” My

central disappointment with The Dreamer is

precisely that Eisner has frittered away his

knowledge and understanding Of the seminal

period of comics publishing, not to mention fail-

ing to take advantage of his unique perspective

as both exploiter and exploited.

Huh. I guess The Dreamer was a big think in the columns of The Comics Journal?

Dwight Decker writes in Amazing Heroes #121, page 52:

Meanwhile, out in the great Amer-

ican Heartland, Wisconsin’s Kitchen

Sink Press has published Will

Eisner’s The Dreamer, blurbed as

“A Graphic Novella Set During the

Dawn of Comic Books.” The comic-

book sized squarebound softcwer is

$5.95 for 46 black and white pages

—and it’s it. Eisner, one of the

undisputed grand masters of the

comics form, has written and drawn

a thinly disguised autobiographical

account of what it was like to be

breaking into comic books in the late

’30s. The early history of the comic-

book industry has been written any

number of times in any number of

dull, dry accounts, but in a sense

this is the first time it’s been sent to

music. Through Eisner’s viewpoint

character, “Bill Eyron,” the modern

reader gets a sense of what itfelt like

to be living in that Far-away time and

working in the field.[…]

The

dream motif is unfortunately more

obtrusive than evocative, and seems

almost calculated to make “Eynn”

appear unusually senstive and

gifted, noble even, and meant for

better things than cranking out cheap

thrills in an artists’ sweatshop.

But Eisner did such a splendid job

in evoking a time, a place, and a

feeling, that I’m willing to forgive

him for a certain amount of self-

justification. Quite simply, The

Dreamer belongs on the shelf of

anyone with an interest in the

Golden Age of Comic Books. In

lightly fictionalized form, this is the

story of hoov it all began.

Fred Milton writes in The Comics Journal #122, page 39:

When commenting upon The Dreamer, I feel

Groth is really nasty. Since this fairy tale

obviously has some personal overtones, Groth

demands that it ought to present a critical note

to the position Eisner as a person held in the

whole process described in the story. This is

irrelevant. Whether Eisner was a saint, a victim

or an accomplice in the handling of the comics-

business at the time is totally beside the point

in this story-concept. Eisner is “merely” tell-

ing yet another fairy tale. And he is in his perfect

right to do so! Why shouldn’t he? Is it illegal to

have an opinion about the mechanisms in society

if you are not a saint yourself? On the contrary!

The person who may have the clearest view of

the weaknesses and imperfections in society may

very well be the person who commited all the

blunders and mistakes himself—or at least

imagines what it would feel like commiting

them… Eisner may very likely have comprom-

ised some Of his ideals concerning the comic

book industry just to get along and make ends

meet. We all do. That does not mean, that you

deprive yourself of having a qualified opinion

about how things ought to have been instead , nor

of having all the rights to express it, even in

retrospect.

I have met Mr. Eisner personally at two

occasions. He has all the ways of a modest and

accepting man, very sympathetic and well-

balanced and not at all a person bursting with

self-assuredness or holy perfection. Most likely

Mr. Eisner has acquired his opinions and visions

through a life filled with problems and personal

misjudgment. That’s how you become a good

author in any medium. The current comics scene

is filled with storytellers who acquire most Of

their inspirations from their colleagues and

predecesors, from TV and films—but not from

real life. Eisner may prefer to use his life learn-

ing to tell miry tales—that’s his privilege. He does

not have to use realistic story structures and an

autobiographical means to express himself. They

will exist somehow anyway when he presents his

creative efforts. Maybe storytellers who use

anthropomorphic figures, myself included, have

it a little easier. No one demanded that Carl

Barks be autobiographical when he wrote his

fairy tales. But the strength of his “themes” were

well-founded in his life experience which he

gathered doing a myriad of things before he

thought up his first duck story. When he did

write, he used all the things he had learned: the

unfair treatment from employers, personal

frustration and aggression from numerous situa-

tions, the negative effects Of things outside the

control of Mr. Middleman. Barks was never

overtly autobiographical and yet in his fairy tales

autobiographical material seeps into his best

stories. A similar judgment may be used upon

Will Eisner even though he preferéd to draw

human characters instead of ducks.

Gary Groth replies:

For what I hope is the last time: The Dreamer

is an autobiography, not a fairy tale. Will Eisner

thinks it ‘s an autobiography, and I think it ‘s an

autobiog raphy.

Garard Jones writes in The Comics Journal #121, page 30:

This becomes painfully clear when Groth

moves from The Building to The Dreamer. His

critique seems based upon two points: First, that

an “essential prerequisite” of any memoir “is a

ruthless self-examination Of the author’s own role

lin the events recounted],” and that Eisner fails

to do this and fails at “pursuing tough value

judgements” concerning the role Of the “ex-

ploiters” who published comics in the late ’30s.

And, second, that Eisner was wrong to attach

a theme (dreaming) to an autobiographical book,

and that he put that theme across very muddily,

to boot.

Here, even more than before, Groth is trying

to hammer Eisner’s work into the pattern Of his

Own aesthetic dogmas, and throwing it out when

it refuses to fit. The Dreamer isn’t intended as

a factual record, as a political statement, or as

a serious literary autobiography; and, frankly,

I don’t see that it has any obligation to be such.

It’s a bittersweet, humorous remembrance of a

time through which the author lived, wrapped

around some amused meditations on the

greatness and the pitfalls of dreaming.

In arguing against the utility Of a theme in

autobiography Groth states, “Theme is one of

those facets of literature the young student learns

in a freshman literature course,” then bestows

his judgement upon Eisner with magnificent con-

descension: “I have a feeling that someone once

told Eisner that every book must have a theme,

because Eisner cannot do without a theme

however supererogatory it may be.”

The presumption Of this comment (even

granted that it’s probably offered with an attempt

at wry humor) is remarkable. It suggests that

Eisner’s themes are not his own, that his desire

to play with ideas and the repeated patterns of

human experience in the course Of his stories

springs not from his own heart but from

something that “someone once told [him].” Thus

it fits in very nicely with (Broth’s earlier implica-

tion that Eisner’s plots and subject matter were

cynically lifted from Hollywood for commercial

reasons. It flows from his basic thesis that Eisner

should have been a socially-committed realist but

sold out. Thus do most Of the points in this criti-

que go back to a starting point which, I main-

tain, is unsupportable.

I’ll agree with Groth that Eisner does pound

on the “dreaming” theme a little too often.

Uh huh.

Gary Groth answers Jeet Heer writes in The Comics Journal #128, page 48:

Notice, first, that my major criticism Of Will

Eisner’s The Dreamer, to the effect that he sugar-

coated the grotesque moral circumstances of the

comics industry, is not challenged by Heer,

though there is much tap-dancing around the no-

tion that there is a standard Of truth to which

works of autobiography should be held.

Apparently, Rousseau can get away with out-

right lying because his autobiography “gives us

a strong sense of [his] inner life” and because

“Lies a man tells about himself can be as reveal-

ing as any number Of facts.” Well, hell, why not?

And Eisner can get away with ignoring the deeper

social and moral issues Of his autobiography be-

cause he “gives us a sense Of how he looks at

the world.” As far as “lenient criteria” go, these

qualify beautifully. However, Malcolm Cowley

does not benefit from such “lenient criteria.” Ap-

parently, even though Cowley certainly “gives

us a sense of how he looks at the world,” this

does not exempt him from adhering to an un-

stated but more exacting standard Of historical

accuracy. Even the Old lies-reveal-as-much-as-

facts criterion can’t seem to get Cowley Off the

hook (no pun intended). It’s all very confusing,

but after reading Heer’s letter carefully, I think

we can divine a rule of thumb: members of the

leftist-commie-pinko-fag axis do not deserve the

benefit of Heer’s capriciously applied “lenient

criteria” of historical accuracy.

I, on the other hand, grant “lenient criteria”

neither to middle-of-the-road liberals (such as,

say, Elia Kazan), nor to Communists and fellow

travelers — nor to anyone else. I believe an un-

yielding truthfulness is practically indispensable

to the form (Kay Boyle and Robert McAlmon’s

Being Geniuses Together is a good example),

though I’ll concede that there can be compen-

sating pleasures that make an inaccurate or im-

precise autobiography worthwhile. Nonetheless,

in Out of Step. a book Heer apparently accepts

as gospel, Sidney Hook writes this about auto-

biography:

..1 have sought to avoid the cardinal sins

of the autobiographer. nese consist in re-

constructing rhe past, denying or covering

up the foolishness and error of previous

years, and casting rhe author in an alto-

gether heroic mold. nis is more often done

by artful omissign and emphasis than by

Wagrant invention. Wish fulfillment often

selectively alters memory.

This is as perfect a description of Eisner’s fail-

ing in The Dreamer as I could possibly hope to

read. Its relevance is positively eerie.

The accusation that I do not apply my strict

criteria for historical accuracy to authors I ap-

prove of (i.e. Cowley) is entirely false because

it rests upon the presumption that the passage

I quoted by Cowley in Joumal #121 was false and

that I knew it to be false at the time I quoted it.

On the contrary, I believe no such thing, and will

draw readers’ attention to the fact that Heer does

not even attempt to disprove the passage I quoted.

Mr. Heer conveniently confuses the particular

with the general. If I understand his point, he

is twing to claim that because I quoted a passage

by Cowley to support my description Of Ameri-

can intellectual life in the late ’30s, I am therefore

endorsing every jot and titter Cowley wrote, and

am therefore guilty Of not applying the same high

standard to Cowley that I imposed on Eisner. My

only claim is that the specific passage I quoted

is historically accurate. Cowley may very well

have revised the extent of his commitment to Stal-

inism, but this allegation is irrelevant. I would

be just as happy to quote a passage I felt was

historically accurate by Eisner despite my mis-

givings about the historical and artistic truthful-

ness Of The Dreamer.

OK, I think I’ll just stop there, because it just goes on and on. Groth’s article, mildly criticising Eisner, turned out to be The Most Controversial Article In Comics Journal History, apparently. But he was right, of course.

This is the eighty-second post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.