Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy (1989) #1-5 by Ernie Bushmiller

There’s been several books written about Nancy, and I think pretty much everything that needs to be said has been said about the subject, so this’ll be a very quick blog post.

Each volume has an introduction from an artist that talks about the ineffable quality of Nancy, and Bill Griffith does the first one.

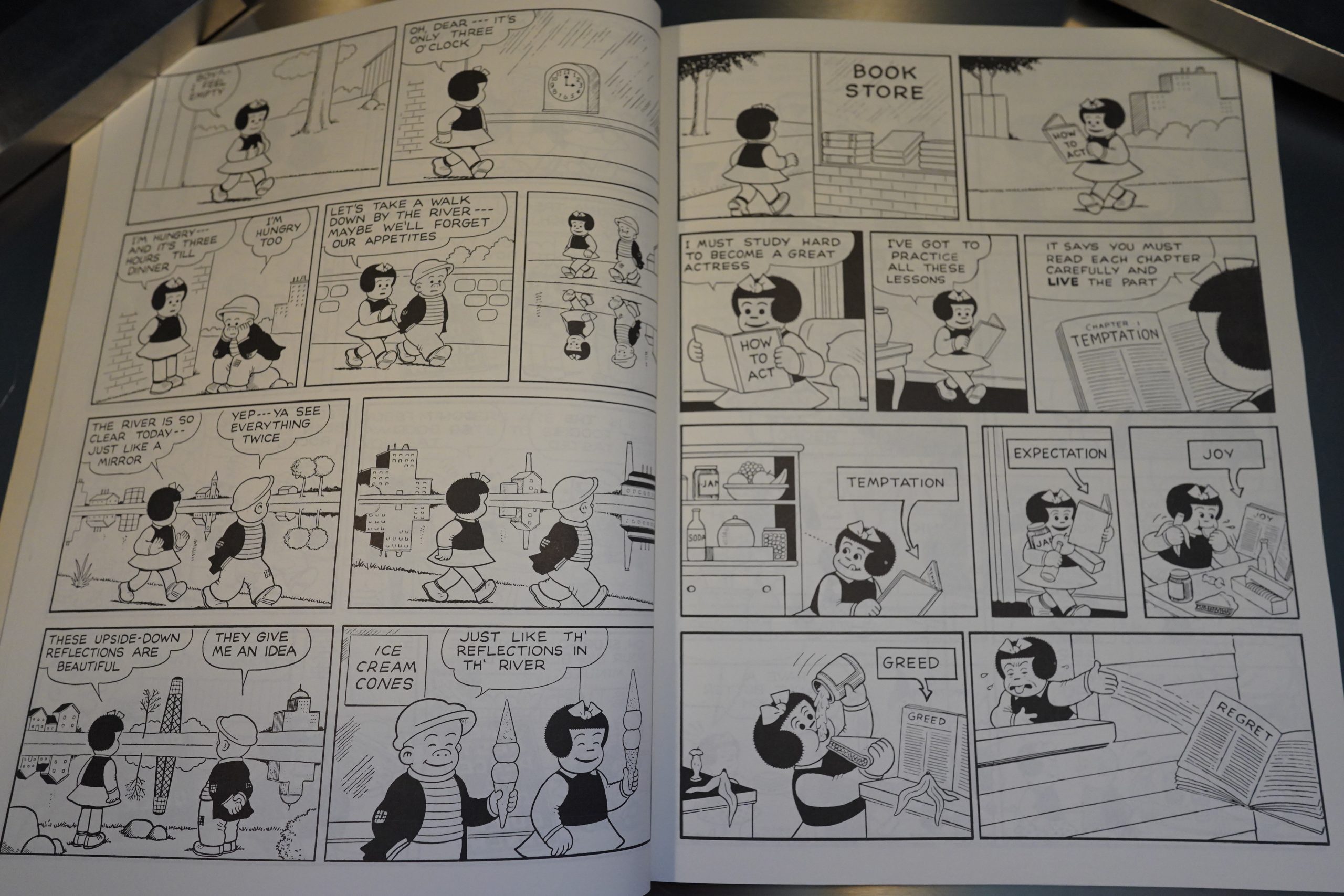

These volumes are arranged by theme. With most strips, that would have resulted in a rather stilted reading experience, but each Nancy strip stands very well on its own, and there’s a timeless quality to the strips, so it’s not too jarring to mix strips that were created decades apart.

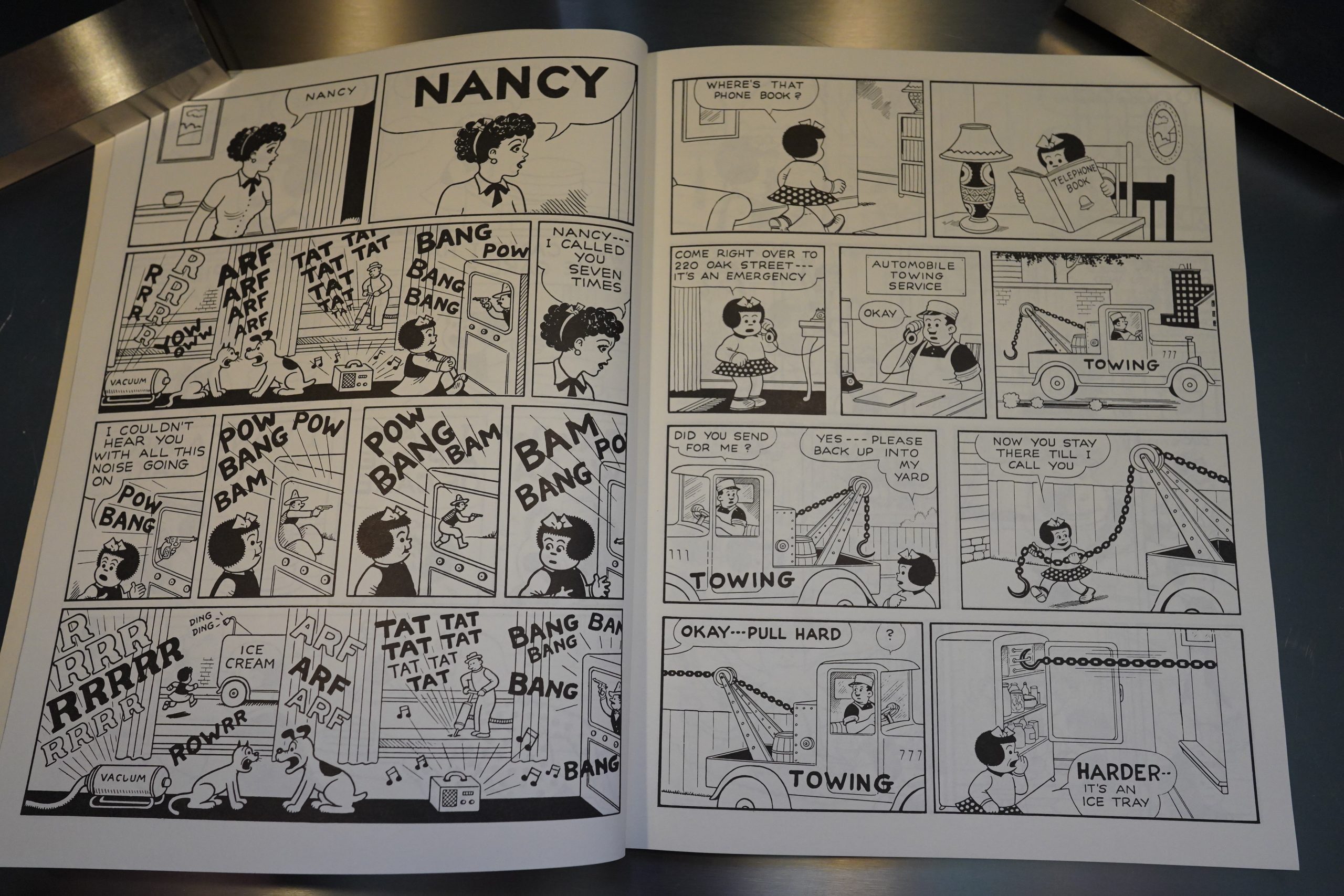

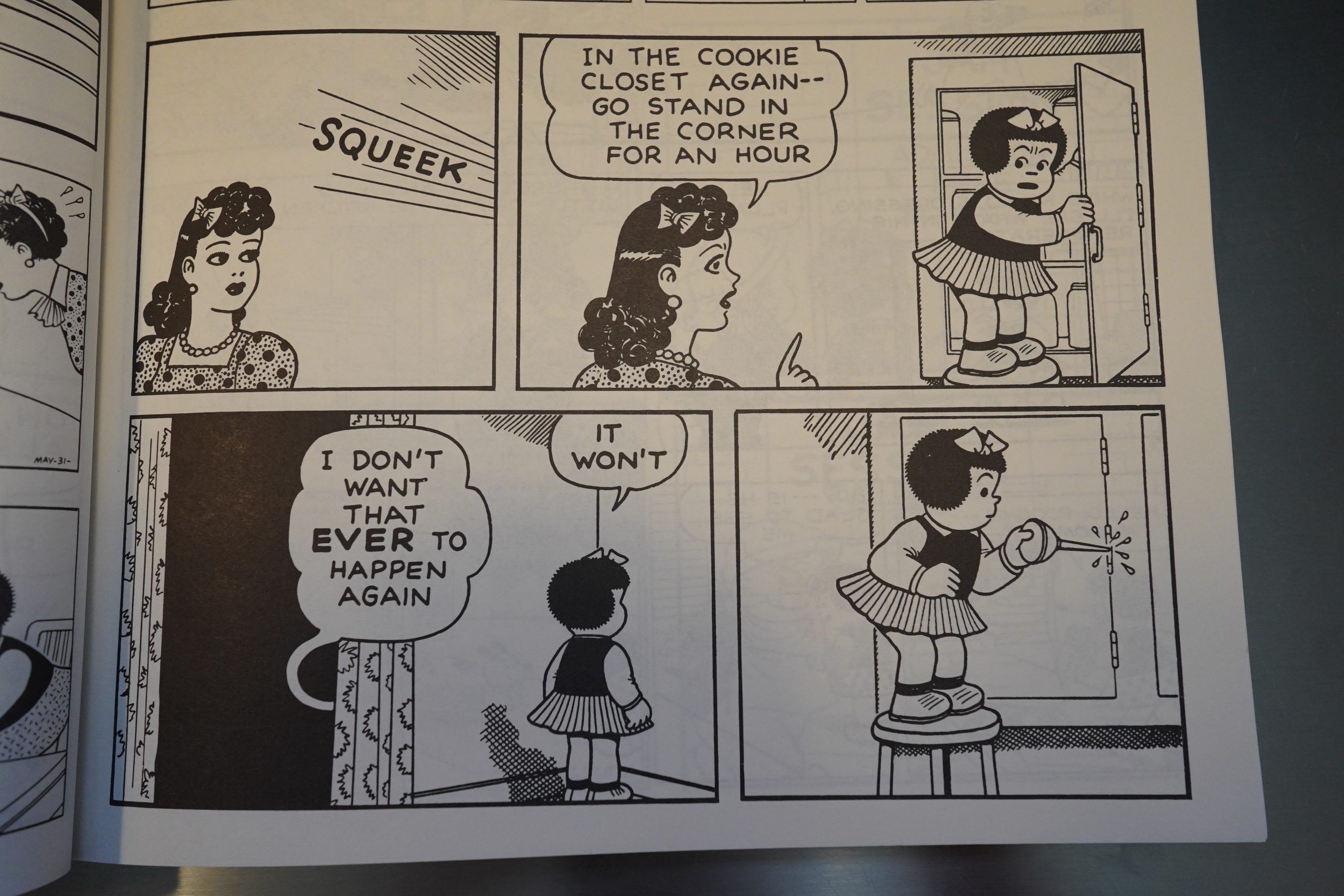

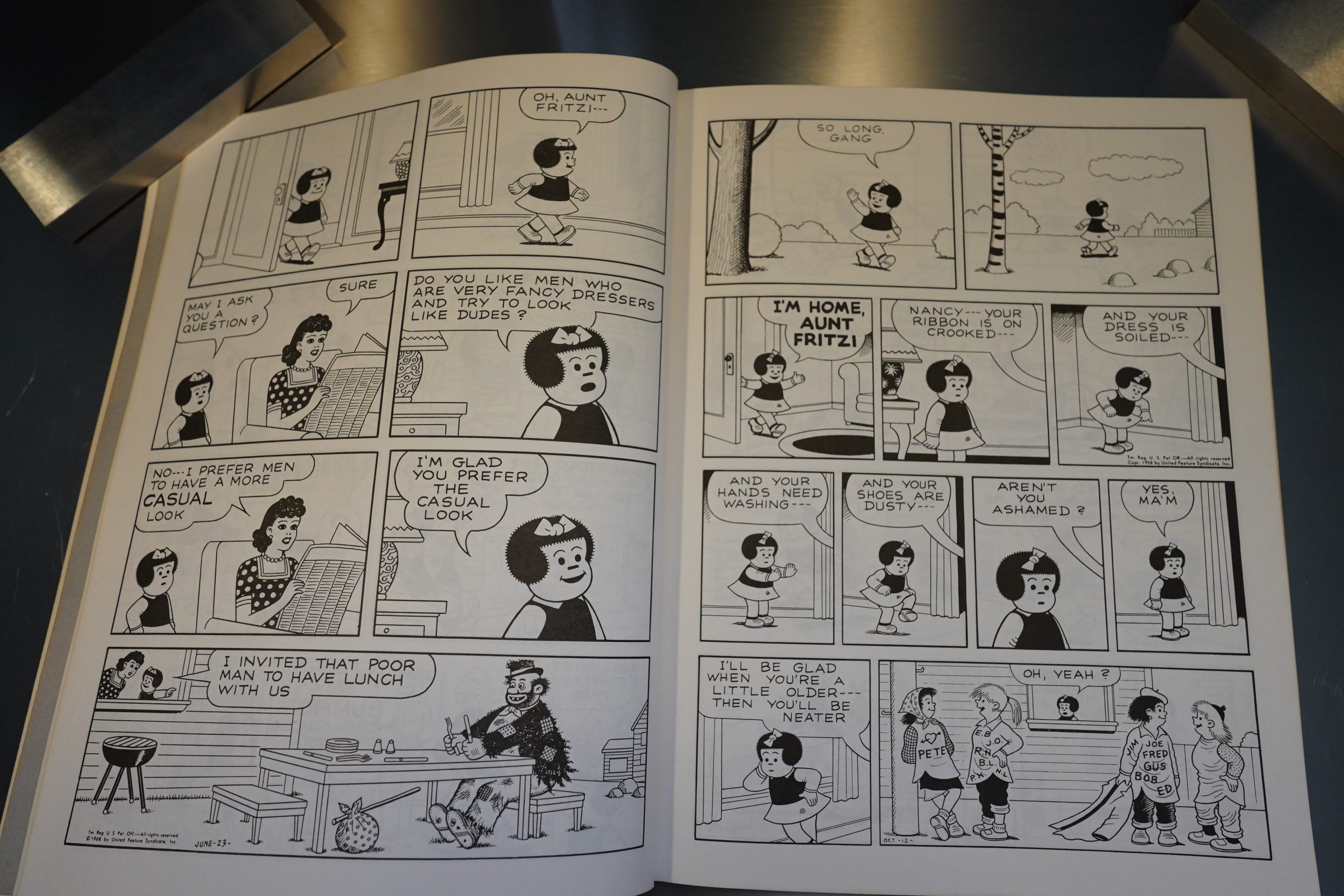

These books have both Sunday strips (like above)…

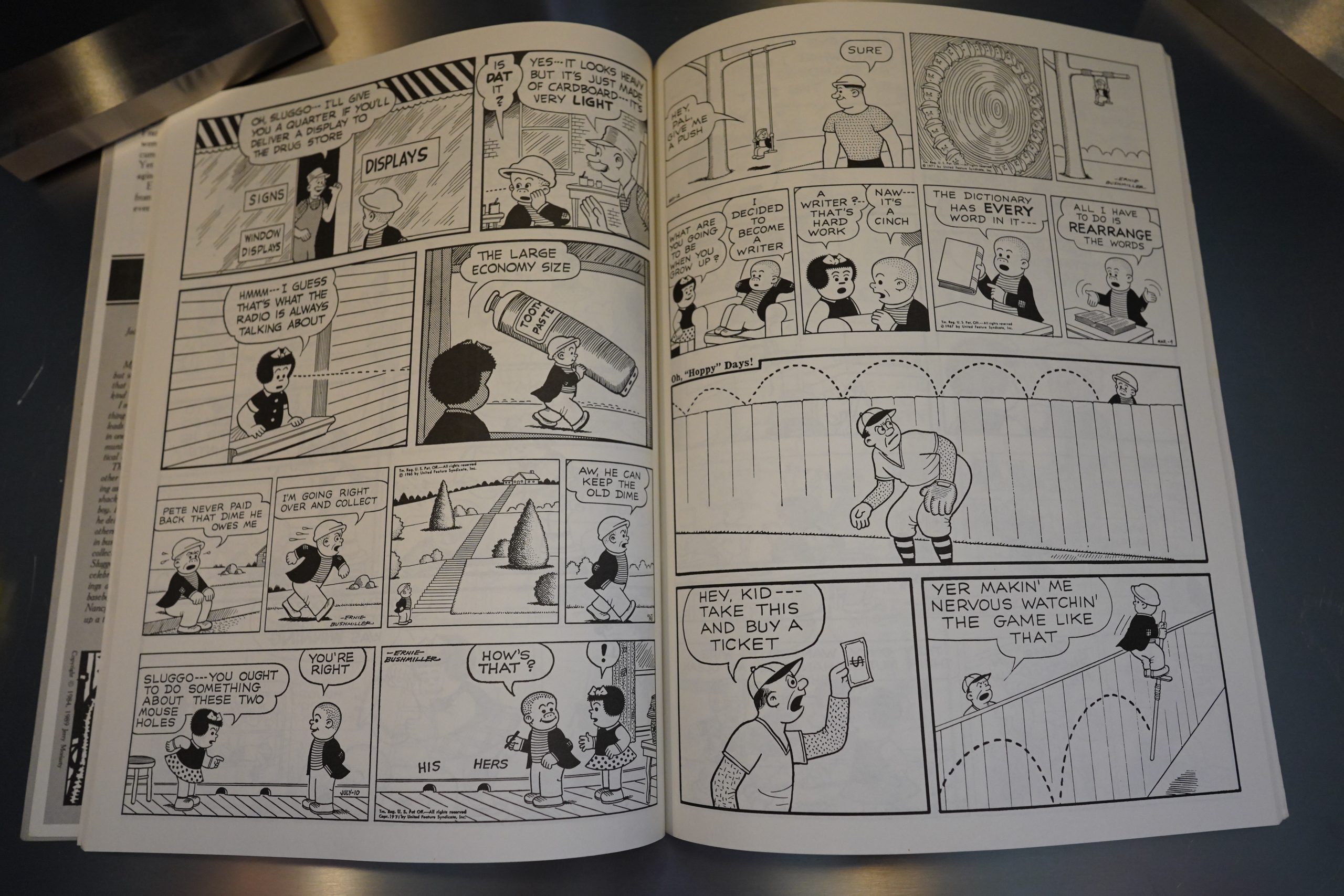

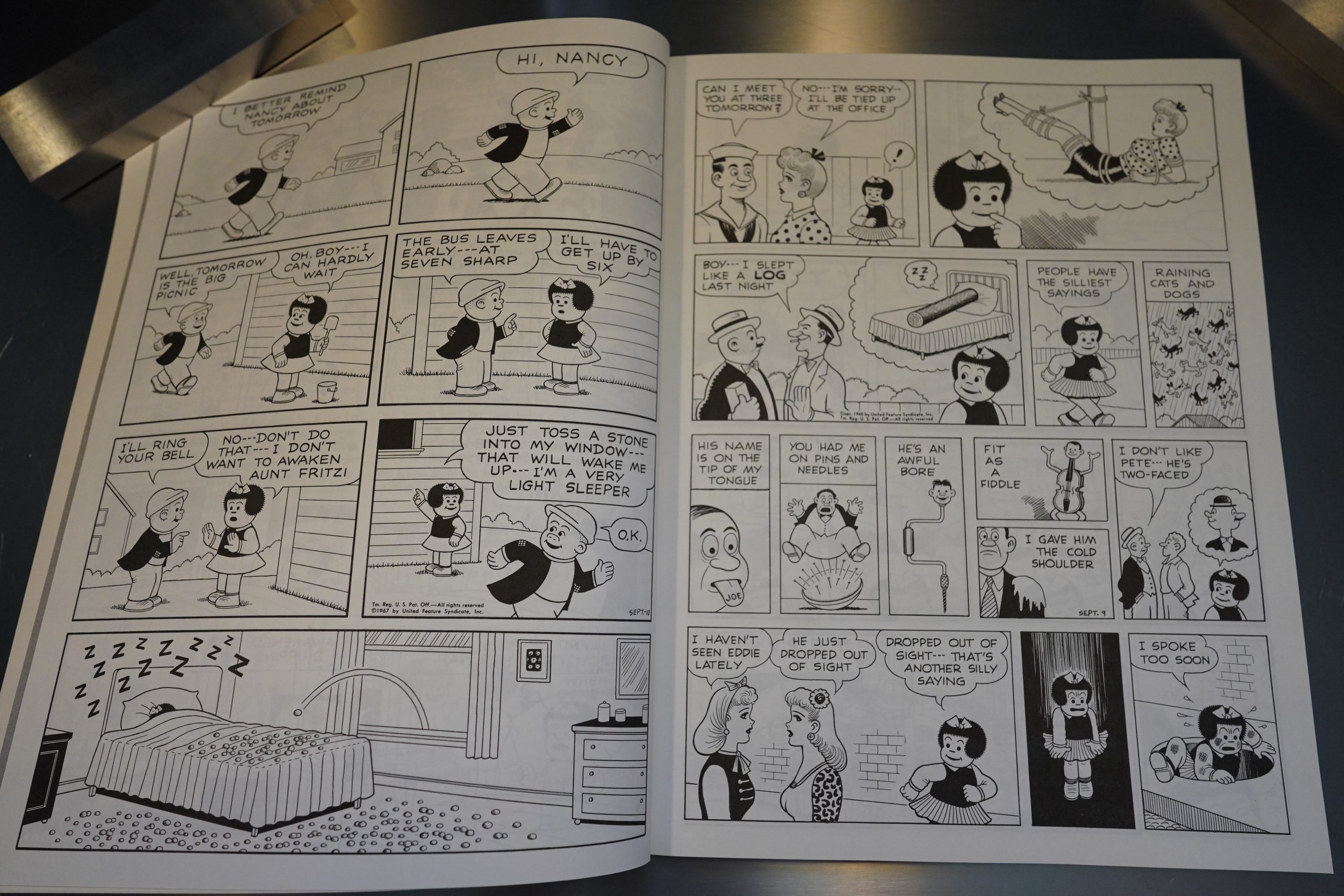

… and also daily strips, which are arranged like this, for the most part. Now, I’ve grown up with newspaper strip reprints that are hacked up any which way, but this does look a bit odd. Perhaps mostly because Bushmiller’s line is so consistent that it looks weird then some of the strips are printed much bigger than the rest, resulting in heavier lines.

Nancy’s such an anarchist.

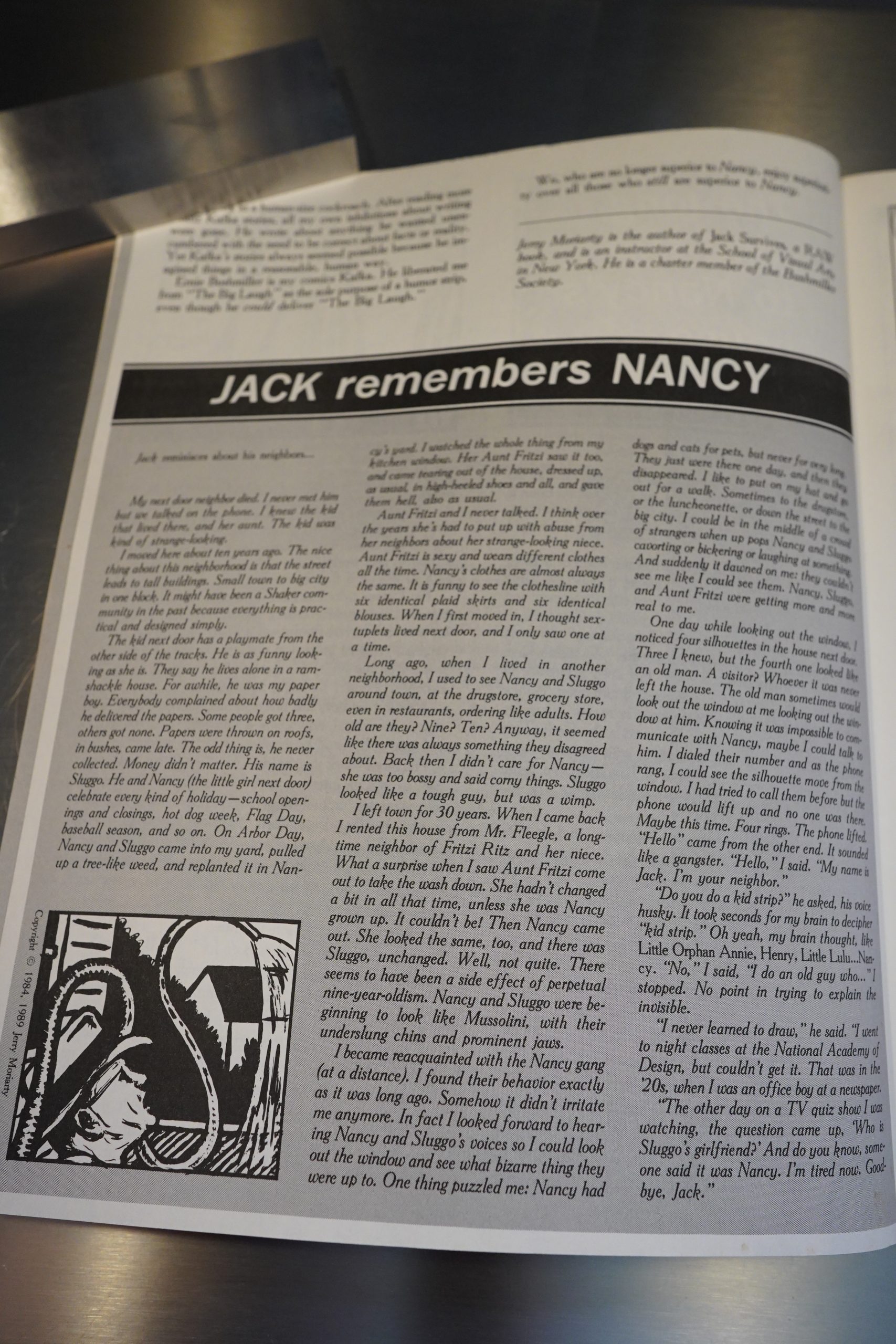

The second volume is called How Sluggo Survives, and they get Jack Survives author Jerry Moriarty to do the introduction. And then he writes a little story, imagining his “Jack” character (based on his father) living next door to Nancy. It’s cool.

So the first book is about food, while the second one is about Sluggo.

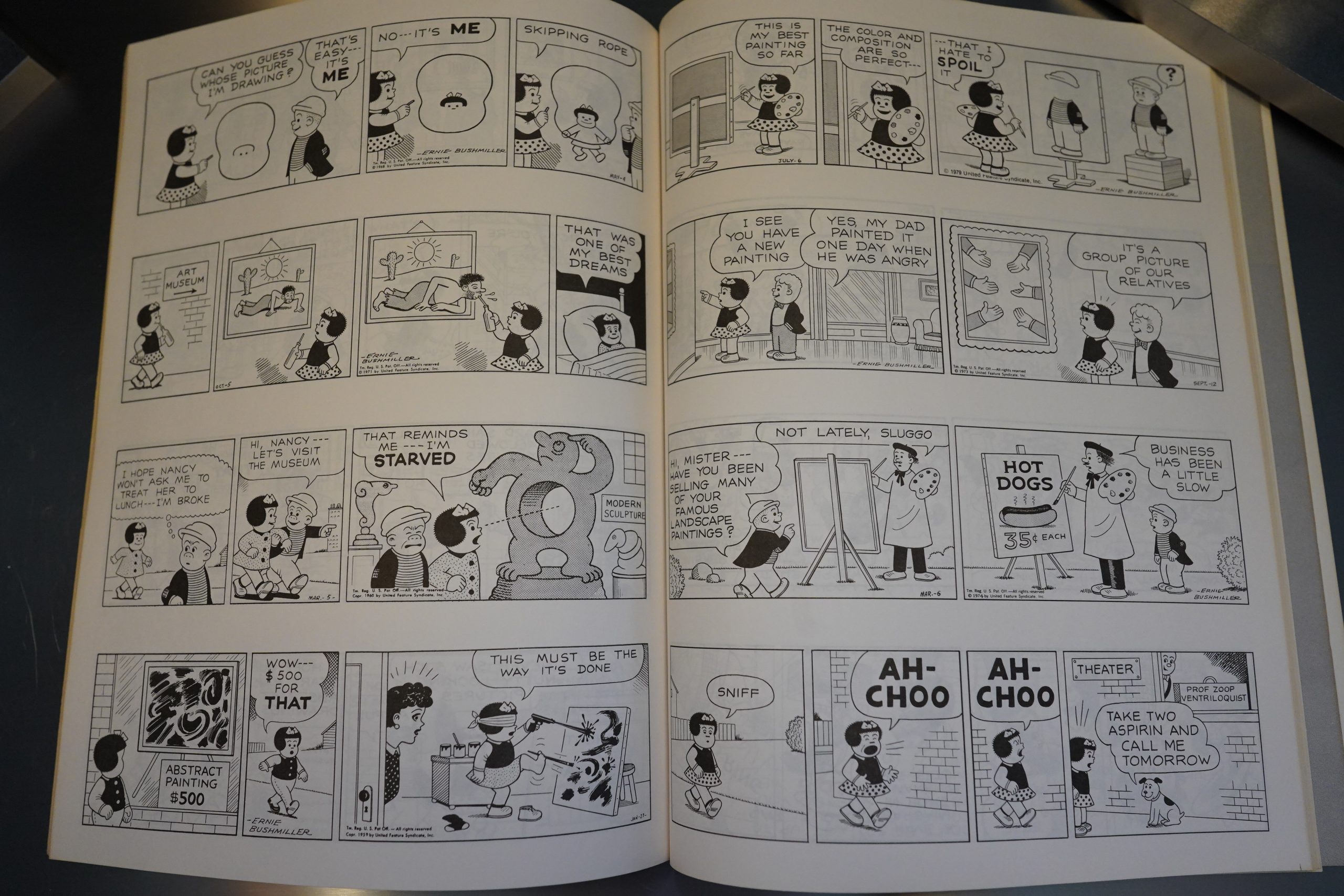

Third one is about dreams and schemes…

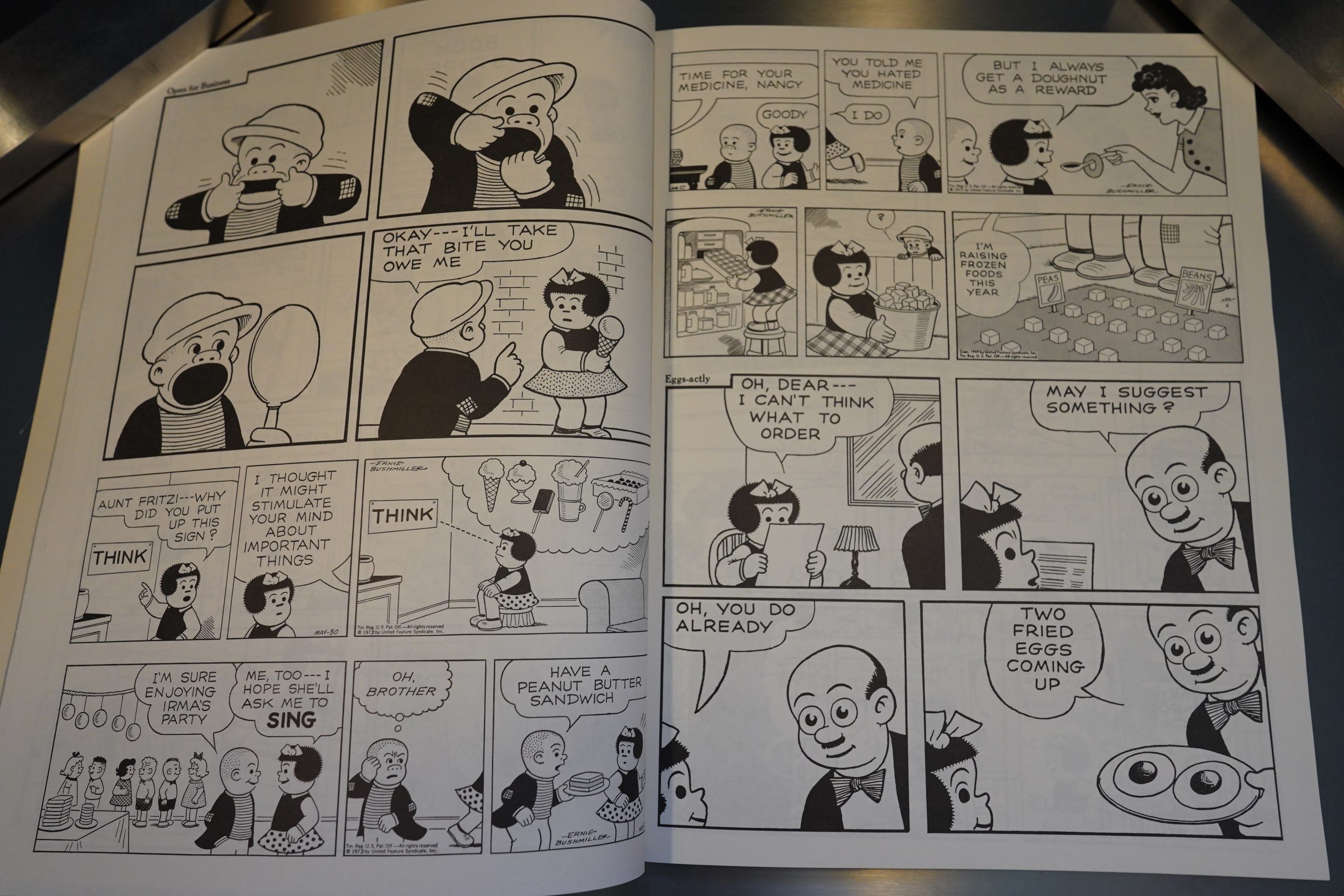

The fourth one has two themes: Hoboes and beatniks…

… and also artists. Bushmiller ribs modern art, but surprisingly gently.

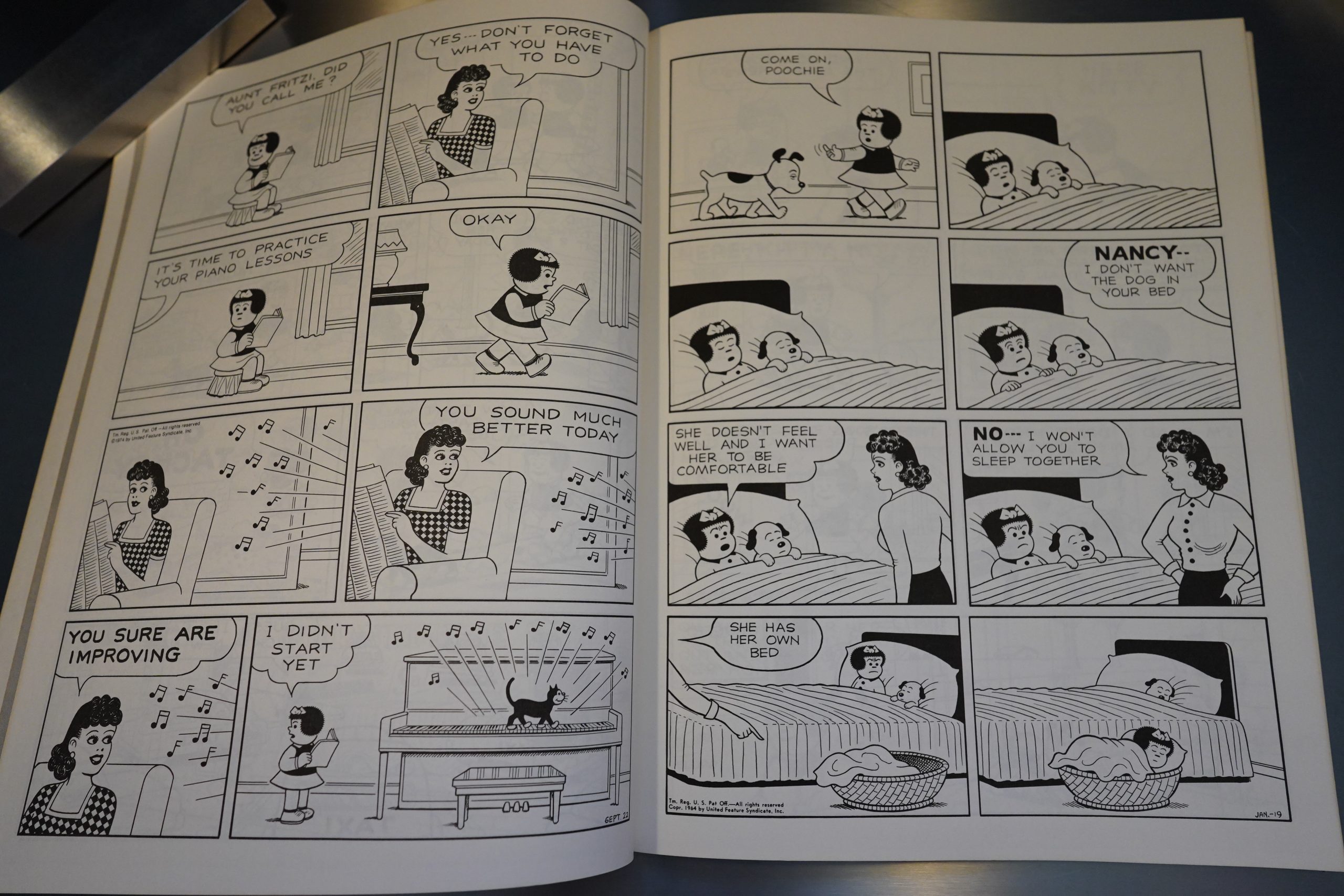

And the fifth and final volume is about pets.

These books are well put together, and the reproduction is good.

Adam-Troy Castro writes in Amazing Heroes #166, page 64:

By the end of his career, Ernie Bush-

miller had become a prime example

of a stranoe species peculiar to pop

culture, a species that includes aniong

its mernbers Liberace, Tammy Fae

Bakker, and Tiny Tim: people so peur-

ile and yet so inexplicably successful

that their names become nationwide

punchlines. But most people who join

that species do so by appearing on tel-

evision, were by definition they’re try-

ing to call attention to themselves.

Bushmiller did it by writing and draw-

ing a particularly annoying comic strip

called Nancy—an activity which usu-

ally wouldn’t be expected to make any-

body’s name a household word. But

people knew who Bushmiller was.

Comedians were abe to use him in

routines. Saturday Night Live put him

on a list of people dolphins are defi-

nitely more intelligent than. When, a

few years ago, a small magazine I

wrote for at the time published Iny list

of 52 People American Would Like To

See Taken Hostage By Iranians, the

only way I knew anybody had read the

damn thing was the literally dozens of

people who congratulated me on put-

ting Ernie Bushmiller’s name on the

list,

I don’t know what possessed Kit-

chen Sink to publish an anthology of

Ernie Bushmiller’s cartoons dealing

with food. It might have been sheer

perversity: this is admittedly the sort

of idea that causes gikgling fits at three

o•clock in the morning. ()r it might

have been outright meanness: Nancy

relied on an exceedingly small number

of jokes, most of which were repeated

again and again to dimishing effect,

and deliberately showcasing one par-

ticular kind of joke is an extremely ef-

fective way of bringing the strip’s in-

herent redundancy into sharp relief.

For instance: On one page, Nancy

(who, incidentally, resembles a clerk

at the office where I Susan)

asks permission to eat some choco-

lates, and promises her Aunt Fritzi

that she’ll only eat one. She rearranges

about 3() of them into a big spelled-out

“one”, and eats them all. On another

page, she promises her aunt she’ll eat

salad and soup for dinner, and spells

out the words “salad and soup” with

spaghetti. And on a third page she

complains there’s a hair in her soup.

There is. The word hair in alphabet

letters. The joke wasn’t funny the first

time. The third time it makes us won-

der why Aunt Fritzi didn’t just kill the

little brat; with this anthology as her

defense, no jury in the world would

have convicted her.

Recently, an unbelievable number

of otherwise respectable people have

cited Bushmiller as a major influence

on modern an; one, Zippy the Pinhead

artist Bill Griffith, provides this vol-

ume with an introduction that gushes

eloquent about Bushmiller•s spare but

extremely polished drawing style. I

can kind of see his point there. But

nobody ever said Bushmiller couldn’t

draw—only that his comic strip was

painfully stupid.

In any event, if this anthology

proves nothing else, it’s that Nancy

was a prime candidate for bulimia.

But what does he really think of the strip?

Leonard Wong writes in Amazing Heroes #198, page 72:

Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancv seems to be

one of these things that people either

really like or really hate. I used to

think that it was the stupidest comic

strip ever created. But after Bush-

miller died and Jerry Scott took the

strip over, it quickly became apparent

just how good Ernie really was.

While I’m not ready to proclaim

Bushmiller a creative genius, I have

come to appreciate Nancy’s bizarre

charms. Whether he did it intention-

ally or not, Bushmiller’s characters

occupy a surreal little world, where

everybody and everything is drawn in

a tidy, clean-line style, and the same

dumb jokes and situations keep work-

ing over and over and over.

Nancy’s Pets is the fifth volume in

Kitchen Sink’s reprints from the

series. Each Nancy book is centered

around a theme (food, Sluggo, pets,

etc.), which makes more sense than

a chronological reprinting of the

strips, since the series has no real day-

to-day continuity. 9/hile you’d think

that 90 pages of cartoons on the same

topic would be overkill, grouping the

strips this way gives the books focus,

and helps to showcase the series’

quirkiness.

Each Nancy volume begins with a

short essay on Bushmiller and his

work. The essay here, written by

Bushmiller’s neighbor and friend

James CarlsSon, discusses the Bush-

millers’ pets, and reveals that some of

the animal gags used in the series were

based on actual incidents involving

Ernie and his wife. Illustrating the

piece is a photo of the Bushmillers and

their dog, and a few of the family’s

Christmas cards. It’s a nice “behind

the scenes” sort of thing.

As you would probably expect from

the book’s title, the strips in Nancy’s

Pets involve animals—Nancy’s pets

(which include a dog whose spots

keep changing), Sluggo’s pets, and a

large assortment of birds, mice, and

animals at the zoo.

Series editor James Kitchen has

chosen a nice mix of daily and Sunday

strips that are mostly from the ’60’s

and ’70’s, and presents them one

Sunday or four dailies per page. The

care and quality in the presentation of

this material is consistent with the

high standards set by Kitchen Sink in

their other reprint projects.

Bushmiller•s work employs a gentle,

sincere humor, and his love of animals

is very apparent in this book. Like the

previous four Bushmiller collections,

Nancy’s Pets is full of simple and

timeless gags that you can’t help but

get a smile or a chuckle from.

Seems like sentiment had already begun to shift, and perhaps these reprints were what started Bushmiller’s journey into Acclaimed Genius status?

This is the one hundred and tenth post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.