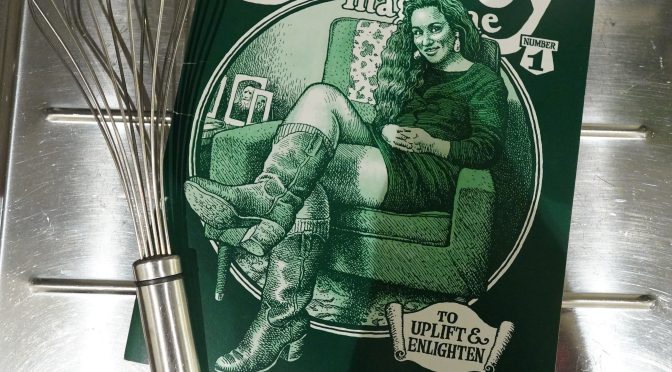

Art & Beauty Magazine (1996) #1 by Robert Crumb

I’ve got the Fantagraphics edition of this here, but I assume the Kitchen Sink one was just the same.

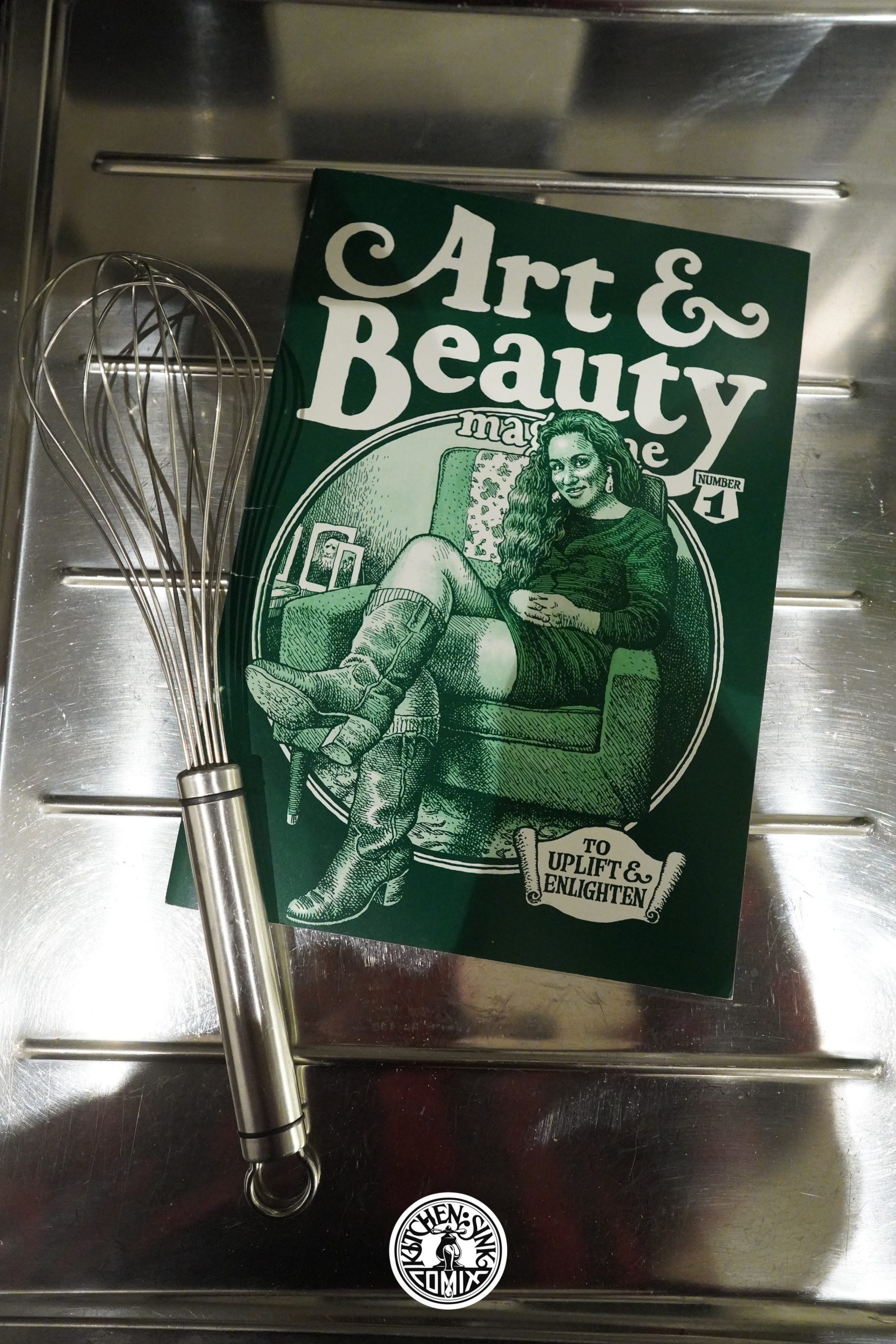

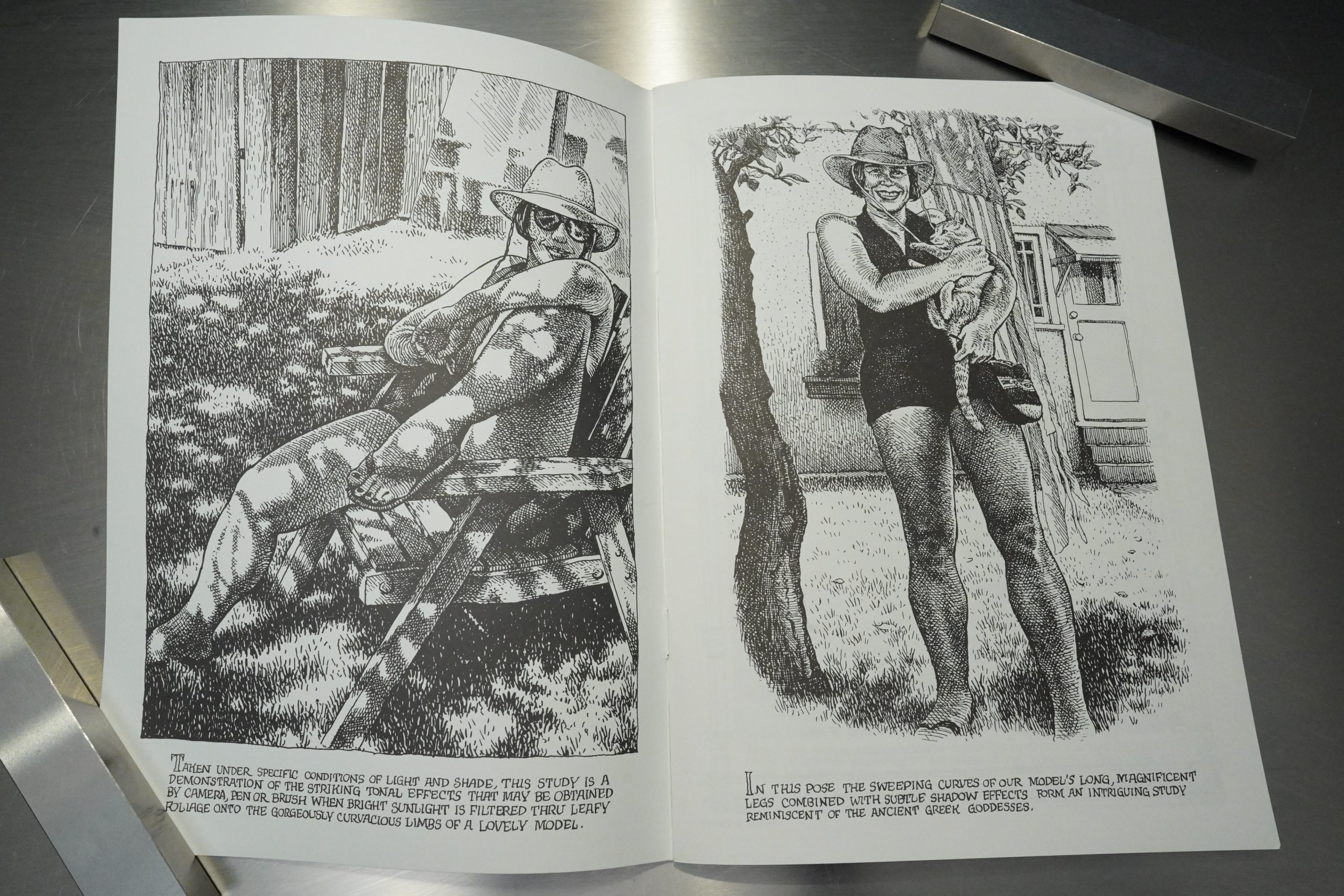

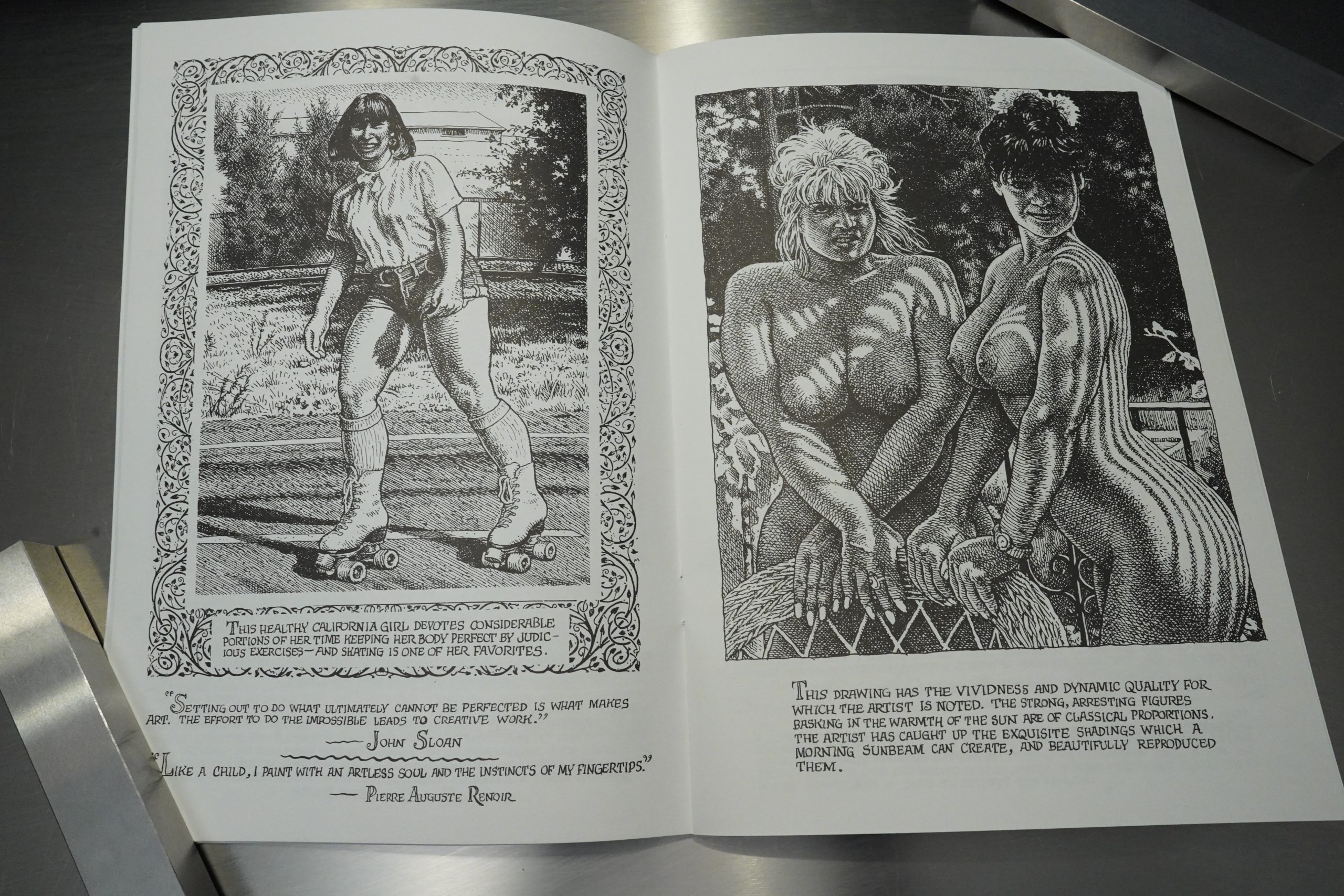

So it’s a bunch of (really good) drawings by R. Crumb, along with a buttload of quotations from various artists and other people. Crumb is trying to express something of what he finds valuable in art, and it’s basically beauty, I think he’s saying? (Oh, and that he hates abstract art.)

The patter from the “curator” about the artwork is very… flattering, and I assume that Crumb wrote it himself. So he thinks he draws good, and he should, because he does.

Oh, I forgot I already covered this over in the Fantagraphics blog series… *reads the article* Oh, I was so much more erudite back in 2016! I agree with everything I said. So there.

Eric Reynolds writes in The Comics Journal #193, page 129:

Do really need to say

anything mcye than “R.

Crumb?” This is the first

all-new Crumb book

since Self-Loathinq

Comics almost two

years ago, and white it

isn’t really a comic, it is one cf Crumb’s most interesting

and fascinating projects ever. The book featwes 35 brand

neu character studys. d’most all of which are Of so-Caled

“Crumb women, ” each with annotations from the artist

and accompanying quotes on art from vanous sources,

a/ hand-lettered and crafted by Crumb.

In a way, this be considered Crumb’s manifesto.

As pointed out, this self-titled magazine about “Art &

Beauty” •s preoccupied with the very figures that have

for so iong been at the root Of Crunws most

;d-reßecttve an, yet here these women

are intellectualized in a way that

seems at odds with the more

instinctive and sexualy-base

presentations of similarly-

formed women in

Crumb’s comics (and

for which he is best

known).

Crumb defends

h’s obsession with

the iema’e physique

very tenderiy and

passionately in Art &

Beauty, revealing a man

is as clearly motivated

by the didactic nature cf great

art well as the more personal

desire to satisfy the id. Of course these are

still coectifications. but Crumb would be a lesser artist

if he tried to deny his obsession with the female form

than if he tried to understand it.

70 extend the obvious Freudian interpretation, these

lavish character studys offer the most tempered filtration

of the artist’s id and ego ever seen. Crumb states that

his own “imagination is stimulated by such pictures,

våich give(s) him the high level of motivation required

for his meticulously detailed pen-and-ink rendering

technique,” but what gives him the motivation and ability

to so articulately express with words his ffvvn artistic 0b-

sessions? ‘t might be the desire to d greater

artist, Or ‘t m”‘ not either way, that has been the

resu•t of it end has characterized Crumb’s preeminence

not on’y’ ds an underground cartoonist, but as one Of

the 20th Century’s most important artists.

Not everybody is equally impressed:

And for many, this, along with Crumb’s countercultural kudos, will be enough for them to find great joy in this exhibition. But I cannot shake the sensation that surveying women who have been drawn on the basis of the sexual gratification they provide for the artist, gives me. Not only do I see the misogyny seething through every pencil stroke, I feel like I see the attempts to obscure it, with humour and academisation, just long enough so that patrons can get out their chequebooks.

[…]

I don’t know if this is the fault of Crumb or the paratextual art-world machinery, to be fair. Unfortunately Lucas Zwirner, son of David and head of the Zwirner’s publishing arm, makes me retch at the opening by encouraging the crowd to think of Crumb in the context of ‘the grotesque’ and Breugel.

Heh heh.

This is the one hundred and ninety-fourth post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.