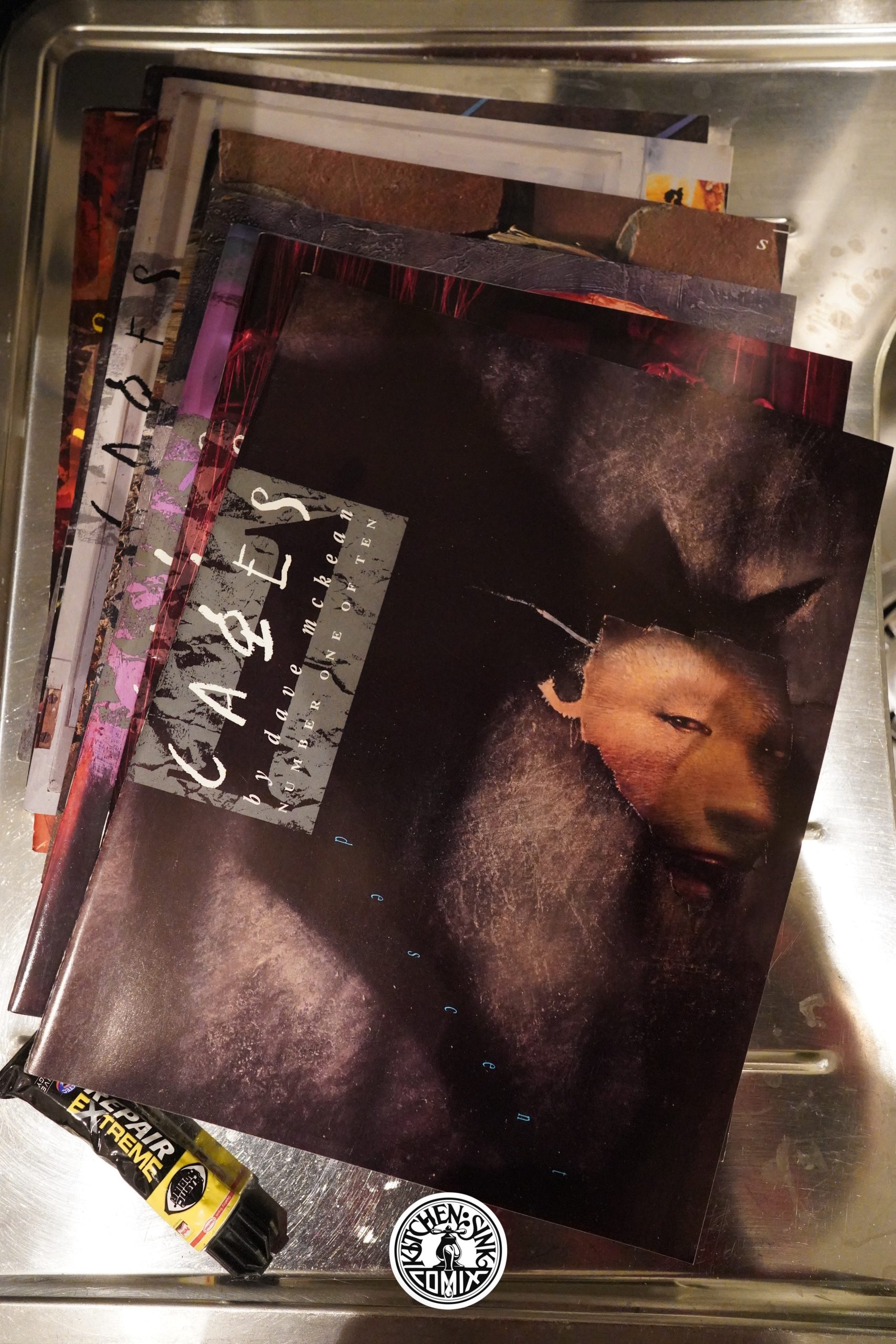

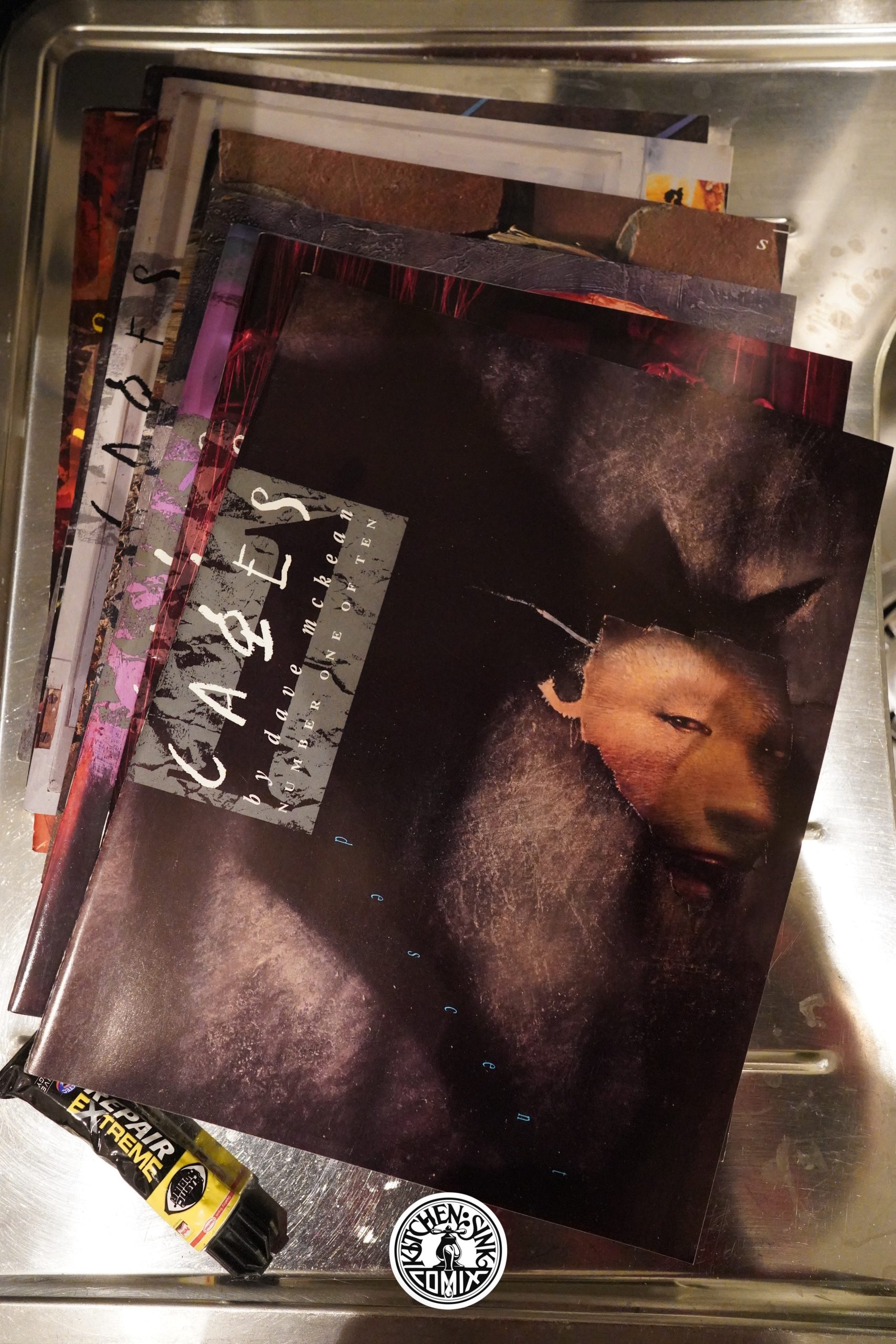

Cages (1993) #1-10 by Dave McKean

While doing research for some of the blog articles in this series, I happened upon somebody talking after the Tundra demise in an interview, and they were saying “so, what comics did they actually publish?” and the other guy went “I can’t even remember — isn’t that strange?”

They published about 50 things, depending on how you count, and indeed: The vast majority of them made no splash in the public consciousness what-so-ever. Reading interviews with Kevin Eastman, who paid for it all (and reportedly lost $14M on the venture), his methodology seemed to be to reach out to artist friends, or artists who were friends of friends, and then go “here’s a huge wad of cash. Go make something awesome.” They took the cash, and some never returned any pages for him to publish, and some lethargically sent stuff back.

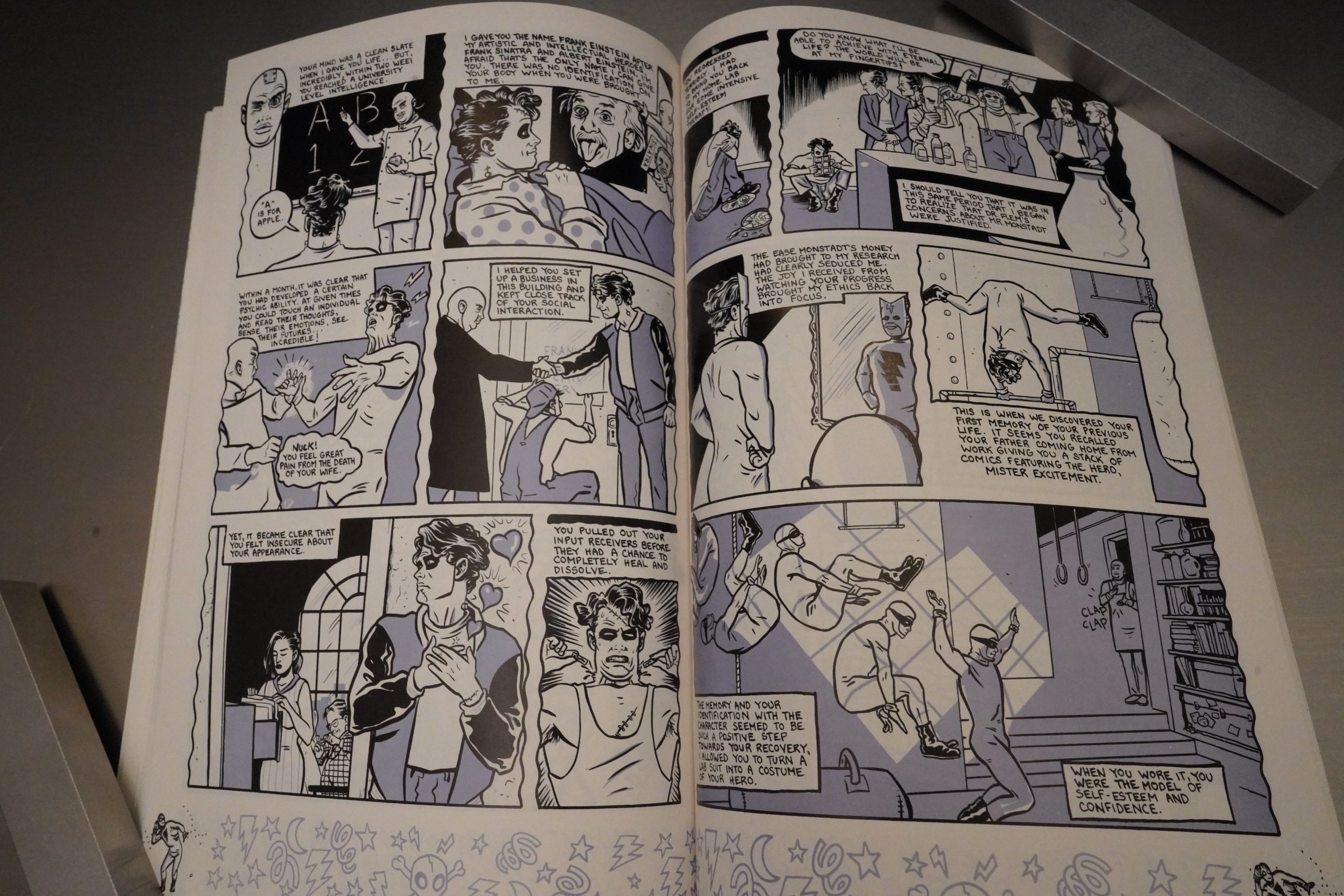

This was supposed to be a bi-monthly publication. Each issue is 48 pages long, and there’s occasional colour, but mostly black and white with a second, grey ink. How on Earth did anybody even vaguely imagine a bi-monthly schedule was feasible? (Except if McKean already had the 500 pages done, which he definitely hadn’t.) In a later interview, Eastman expressed disappointment in artists that just couldn’t stick to a schedule — any schedule, it didn’t matter whether it was monthly or yearly, but at least say what it’s going to be.

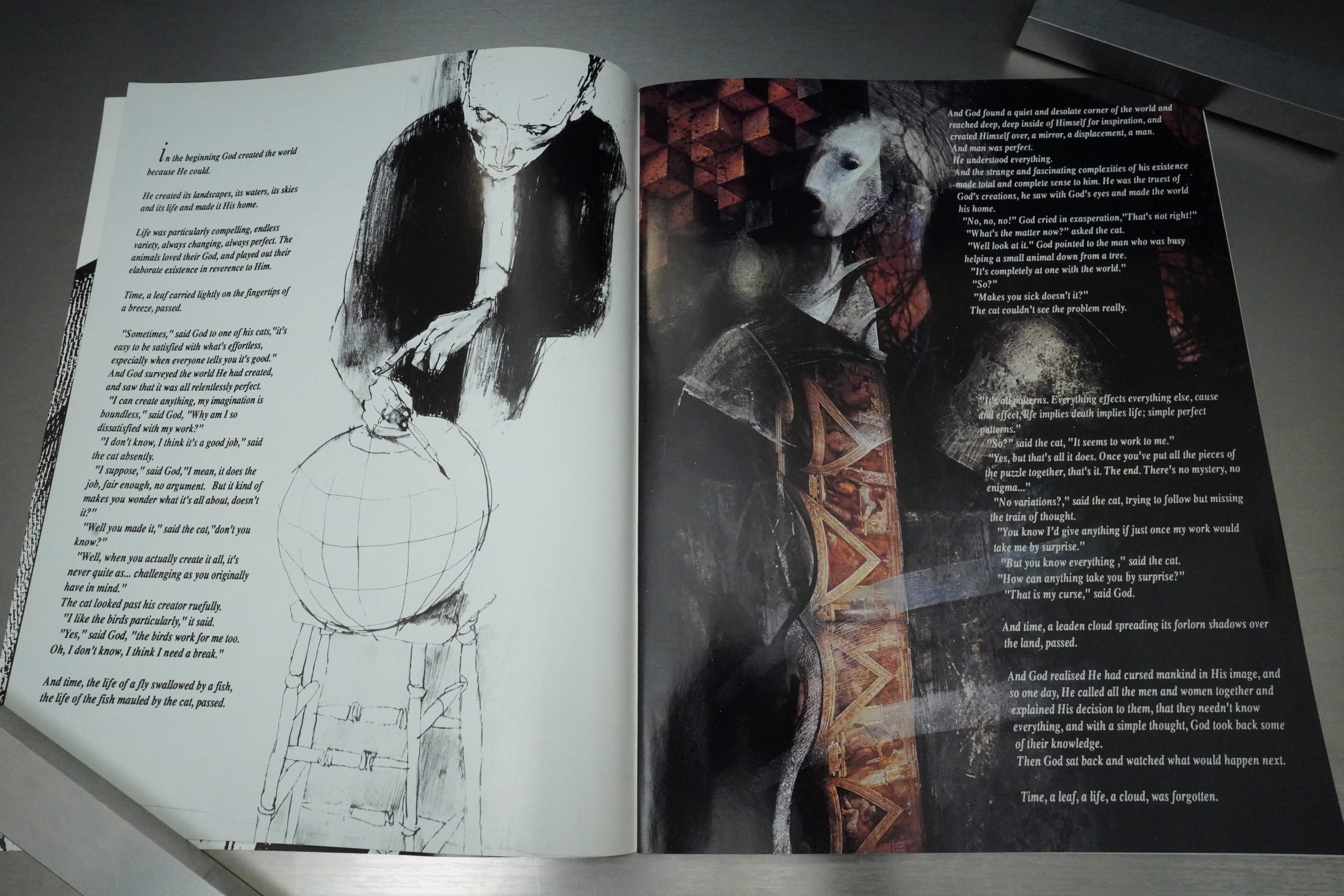

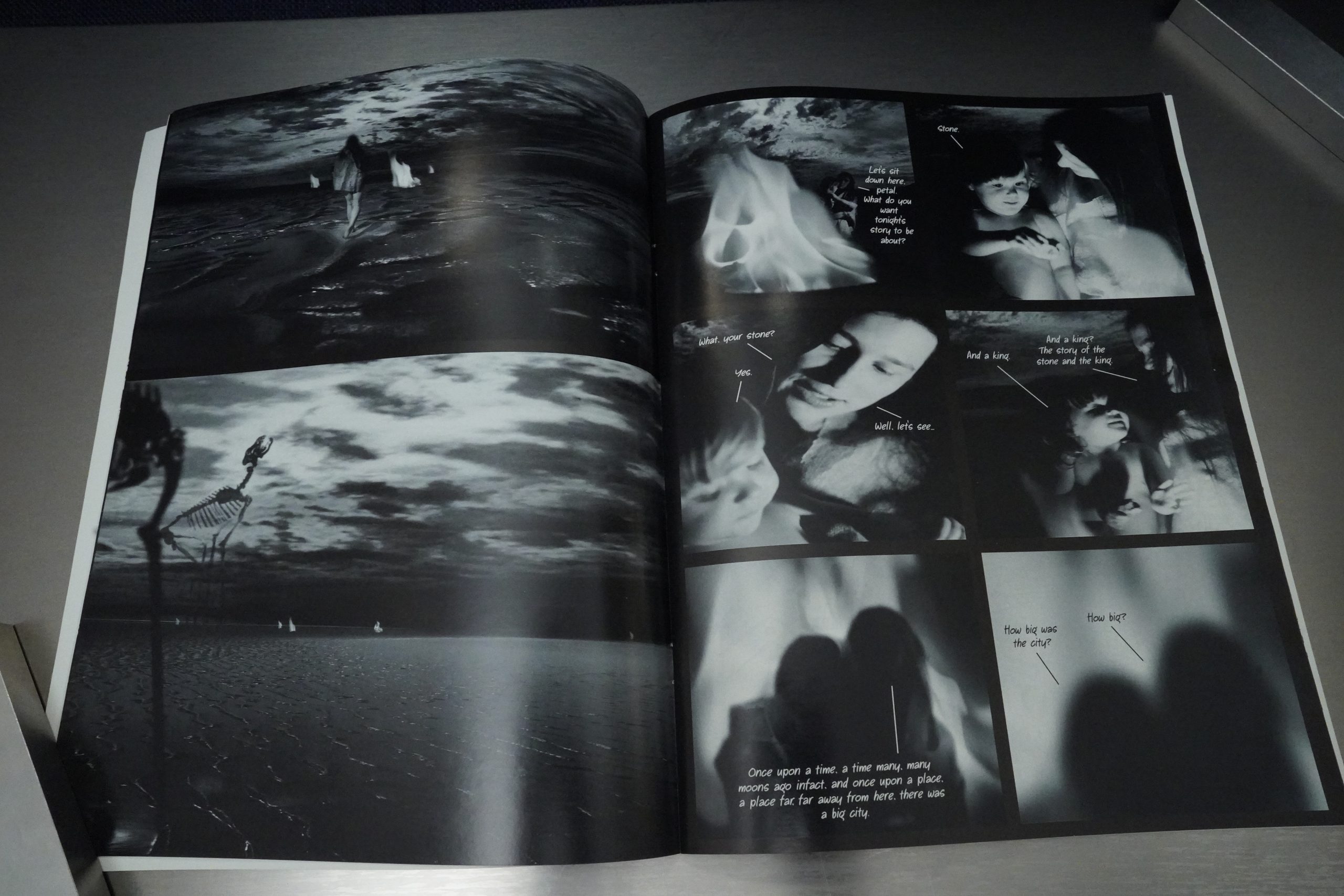

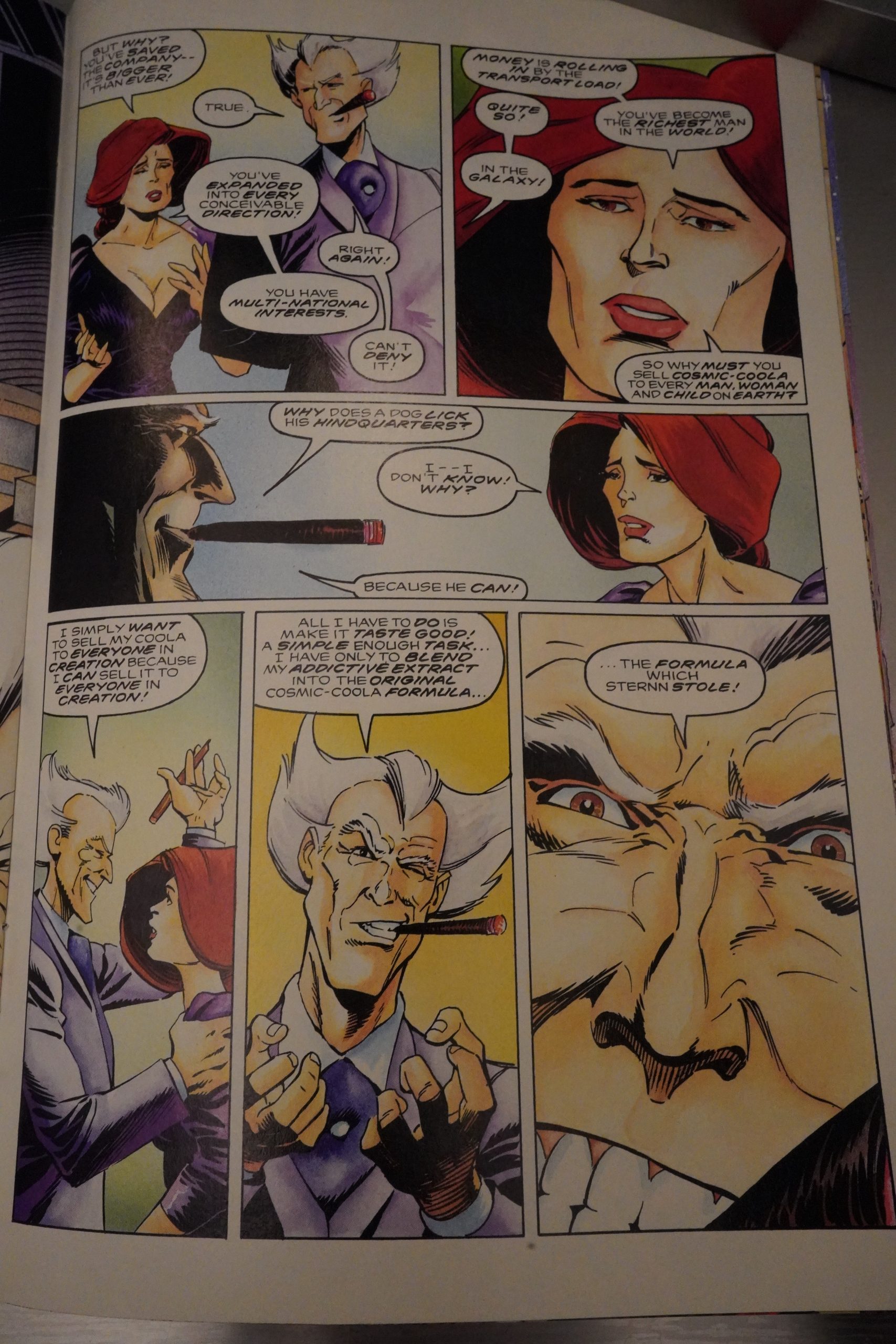

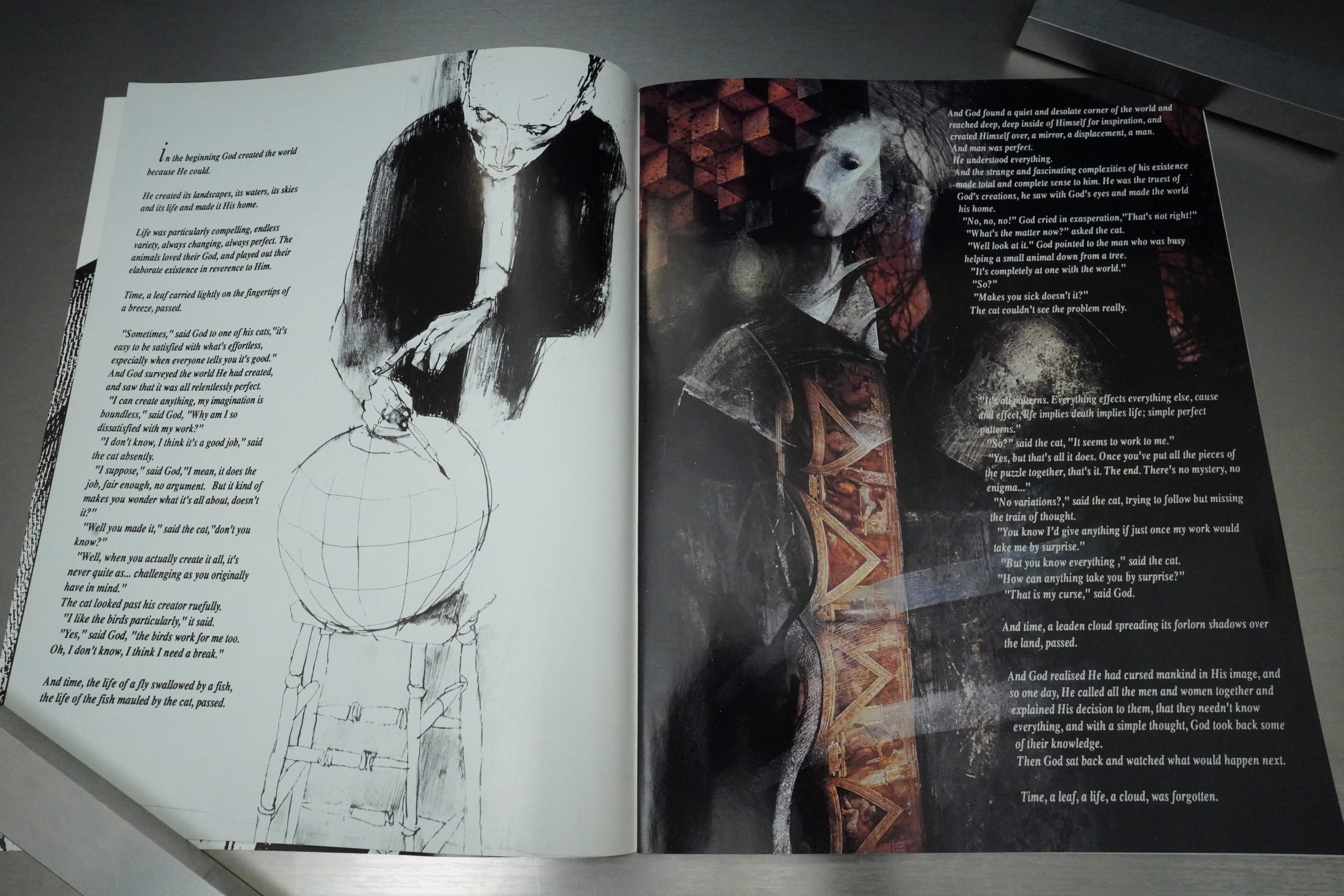

Now, of everything Tundra published, Cages is probably the most well-known comic. (Well, after Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics.) McKean was famous at the time, mostly from the Neil Gaiman association, and (like many of the artists Eastman threw money at) hadn’t written anything before. And this is one of the few Tundra books I bought at the time, and I remember being quite impressed, but not by the start of the book, which is all christianey and gives a whole bunch of tweaks on the christian creation myth.

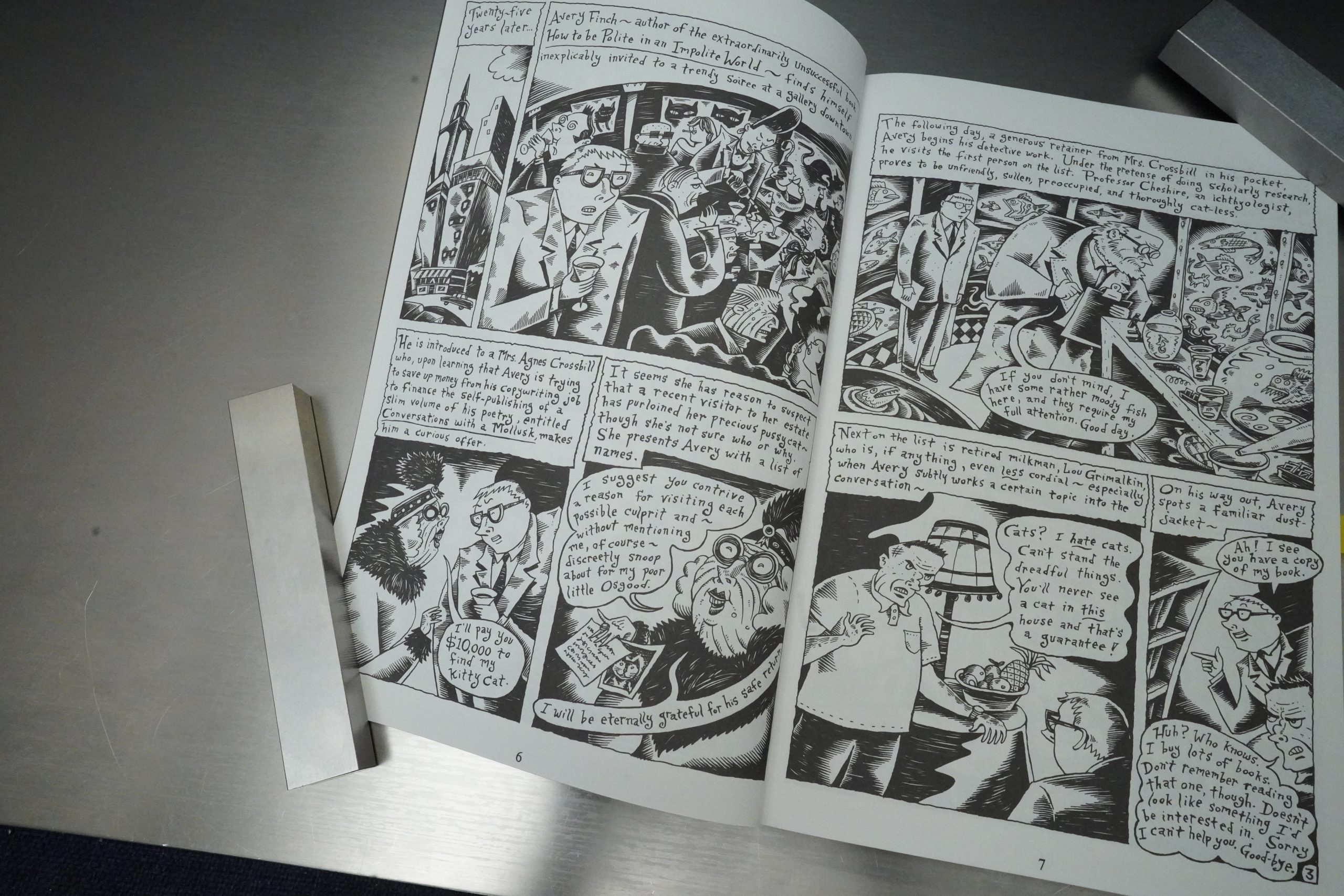

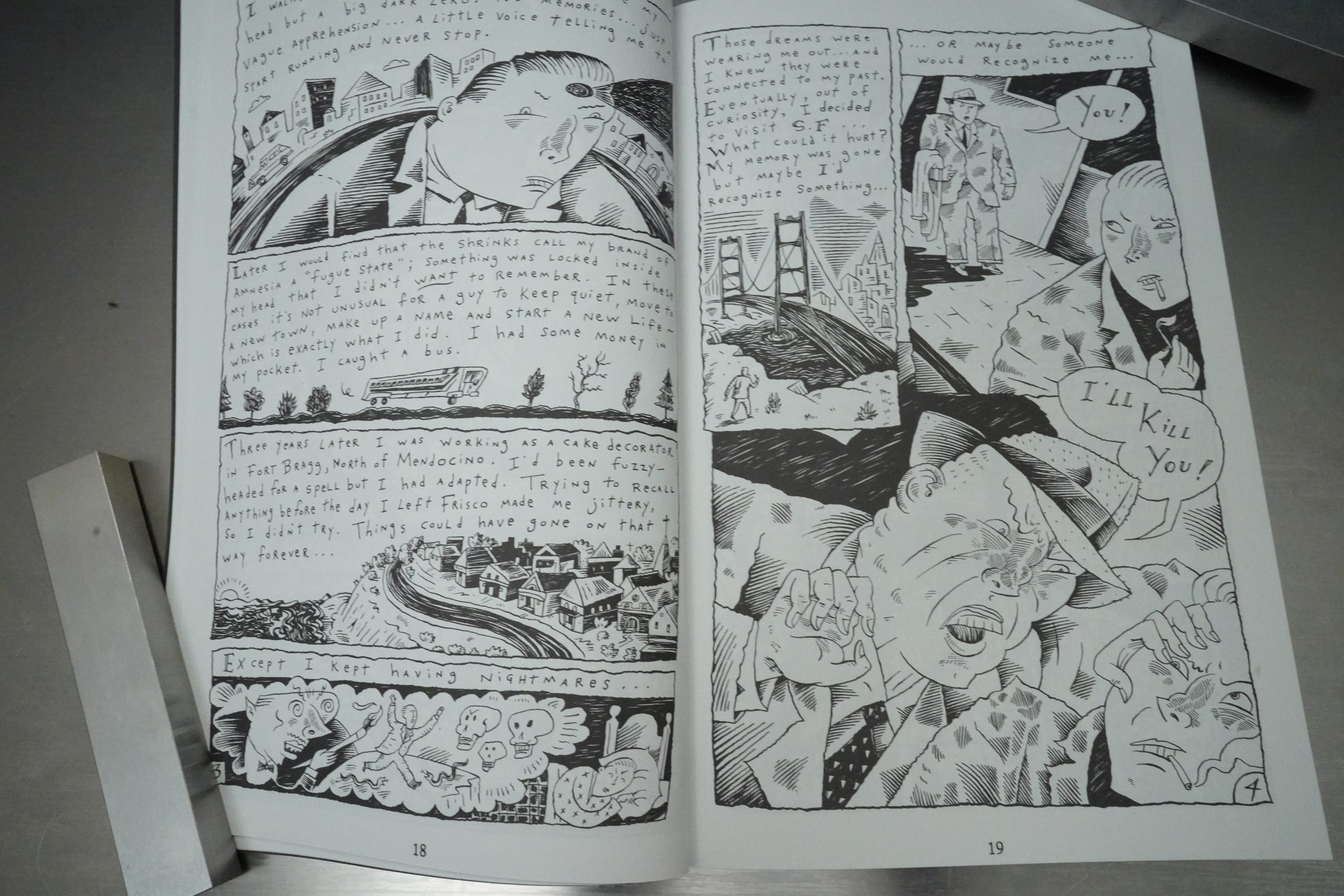

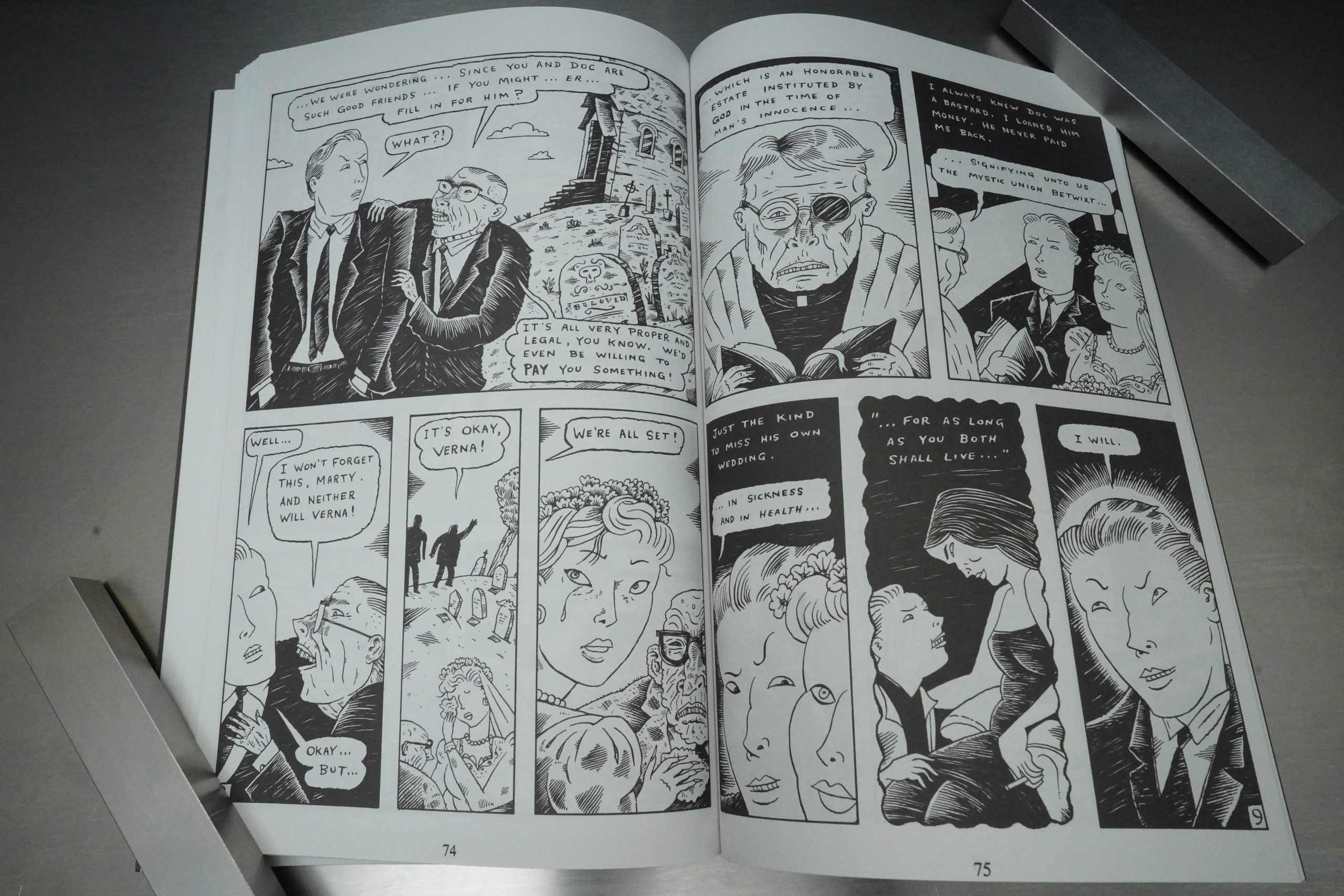

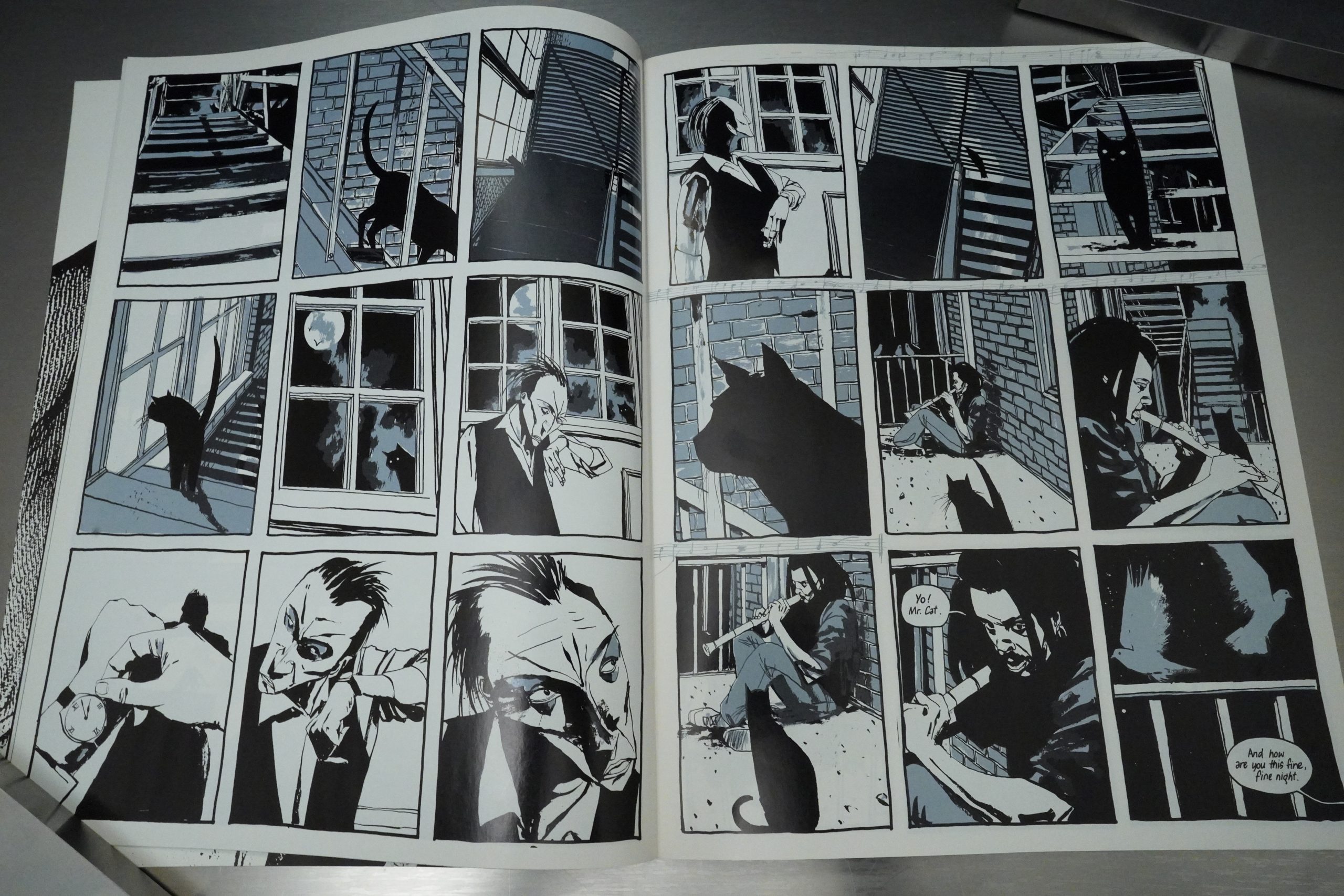

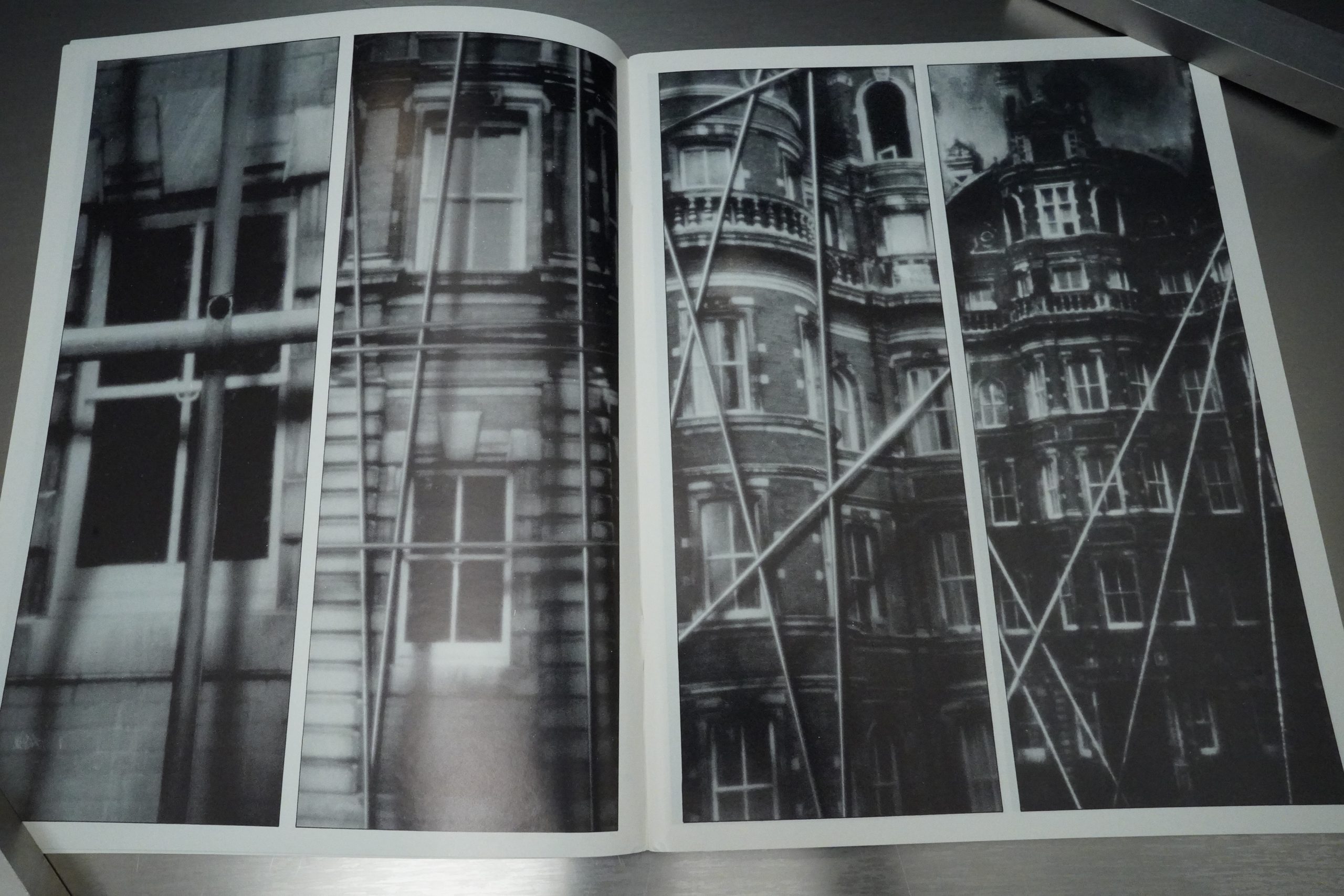

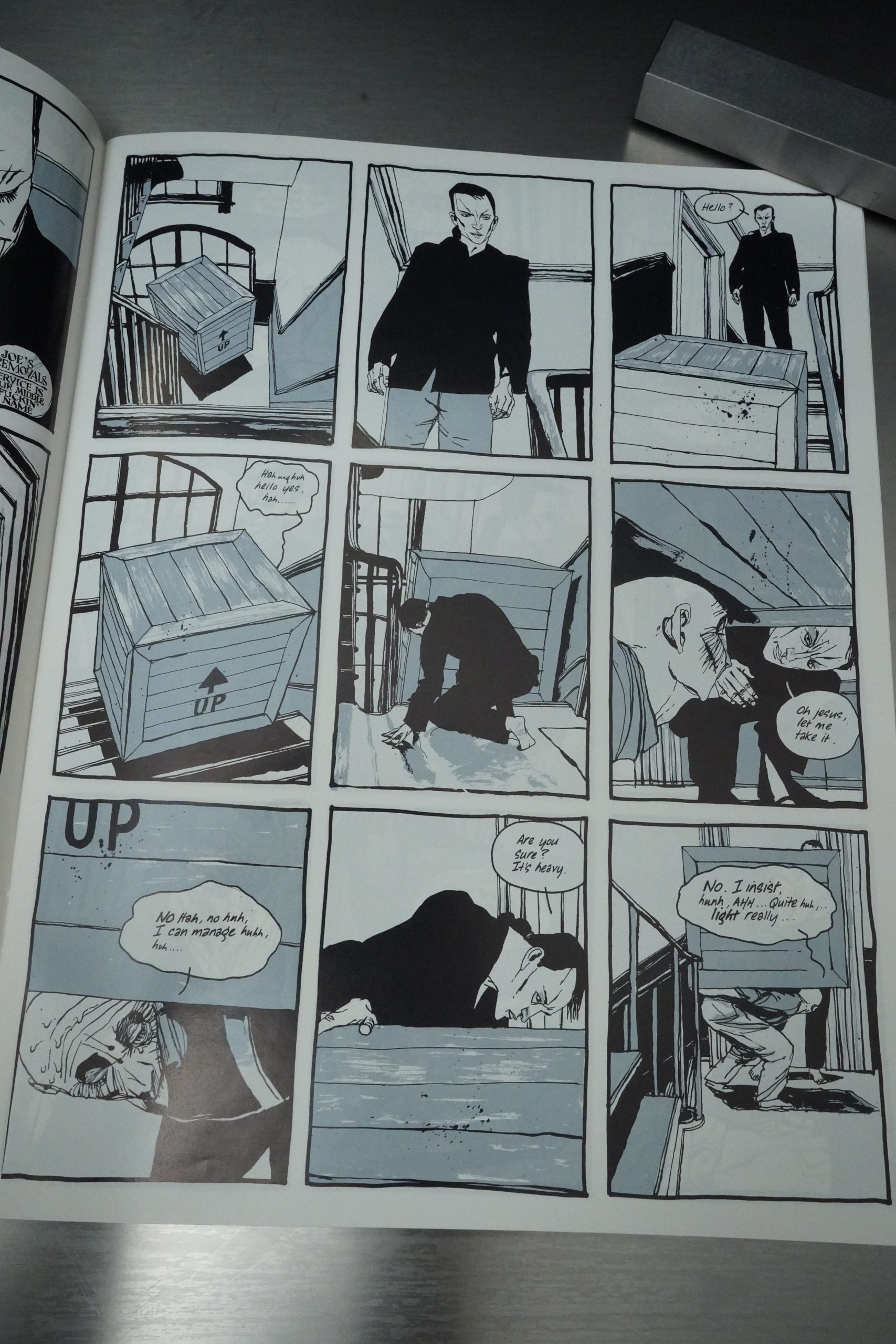

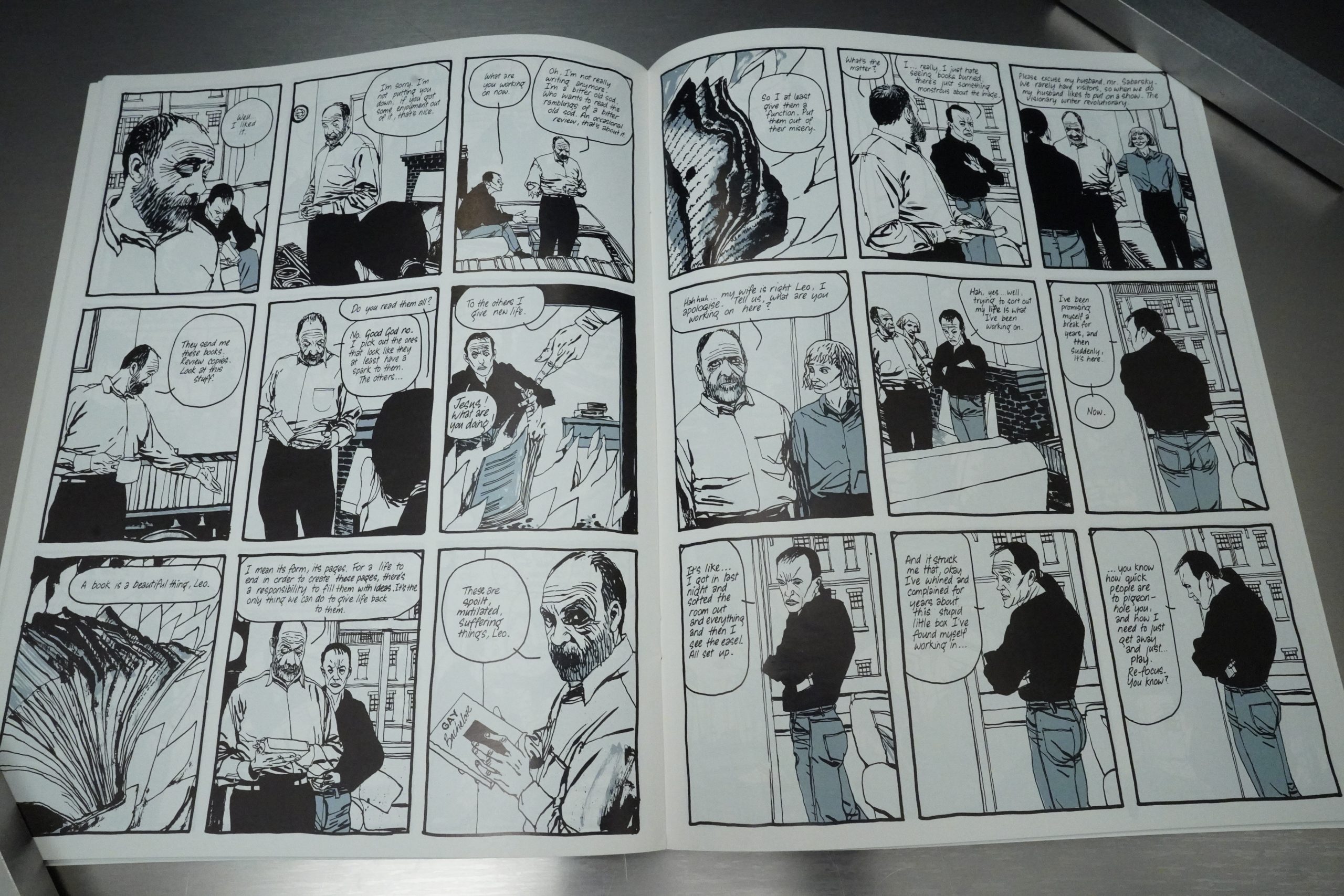

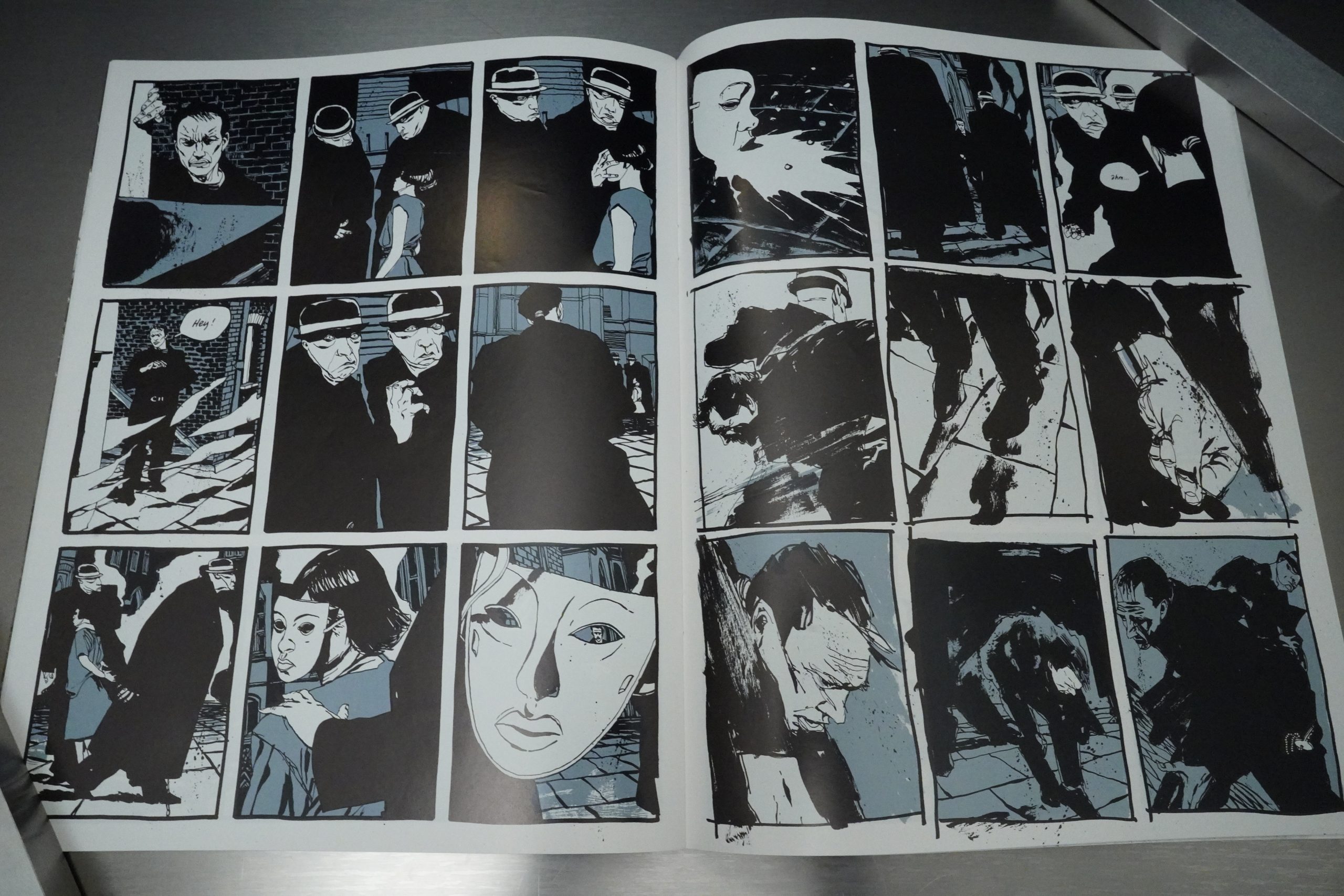

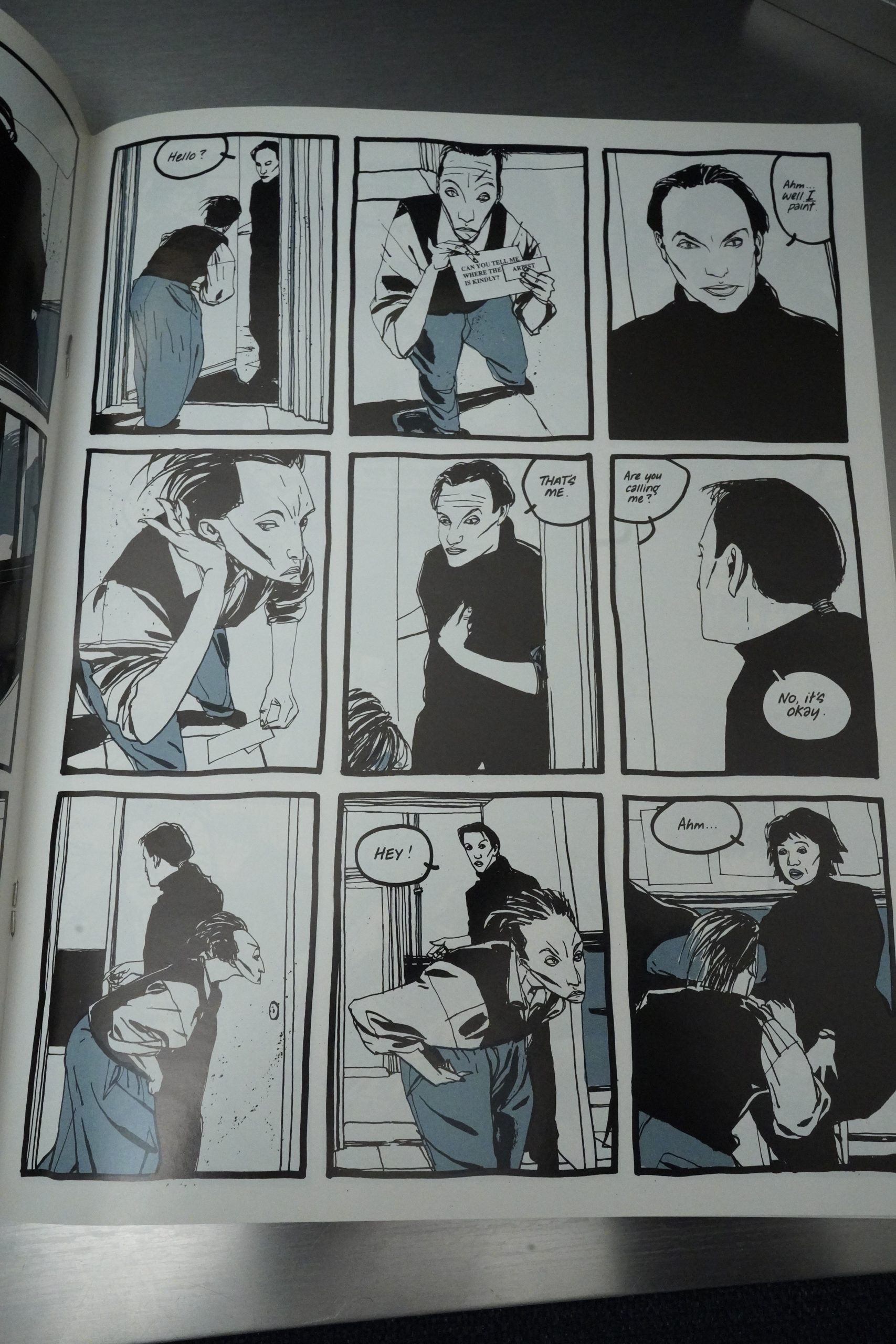

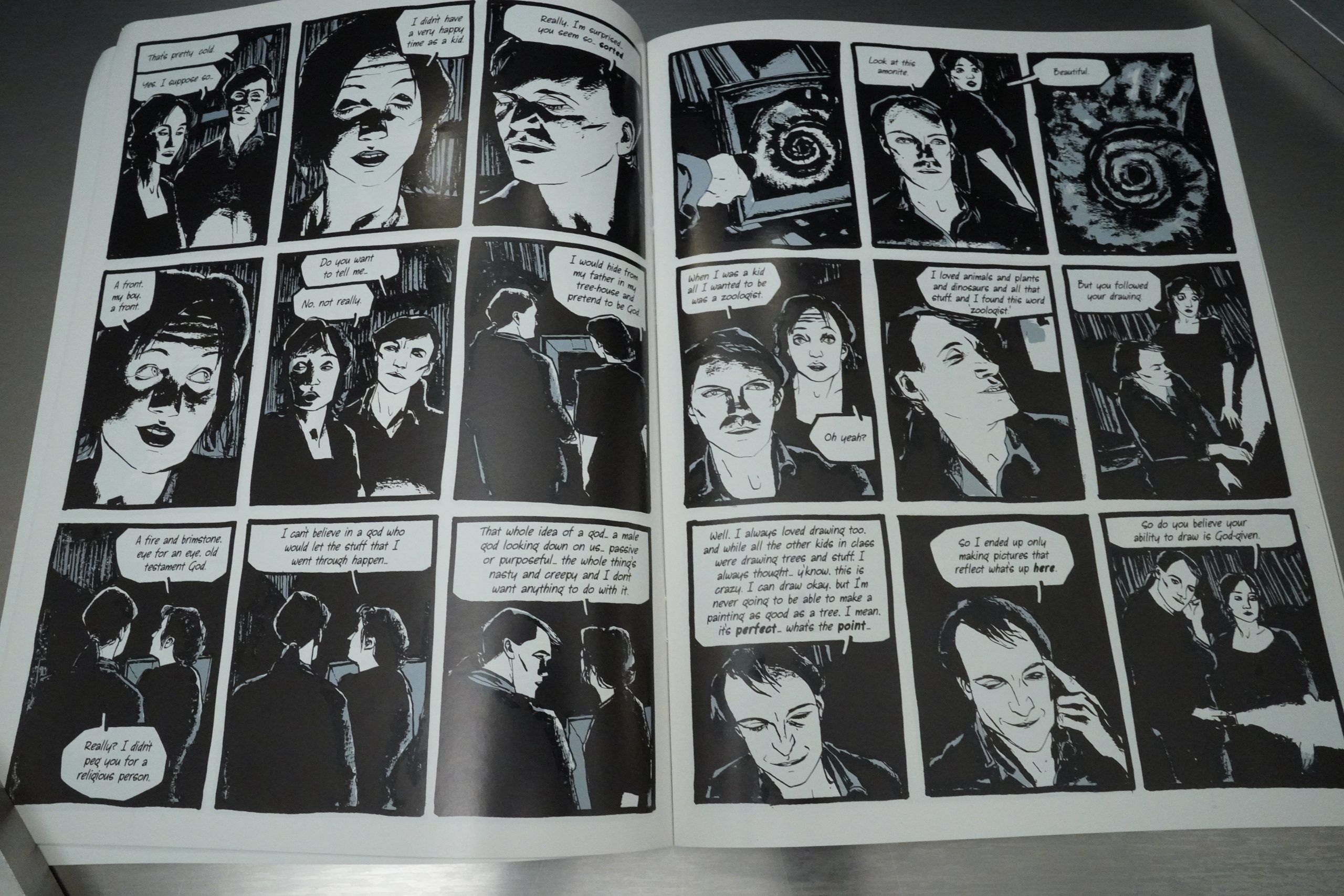

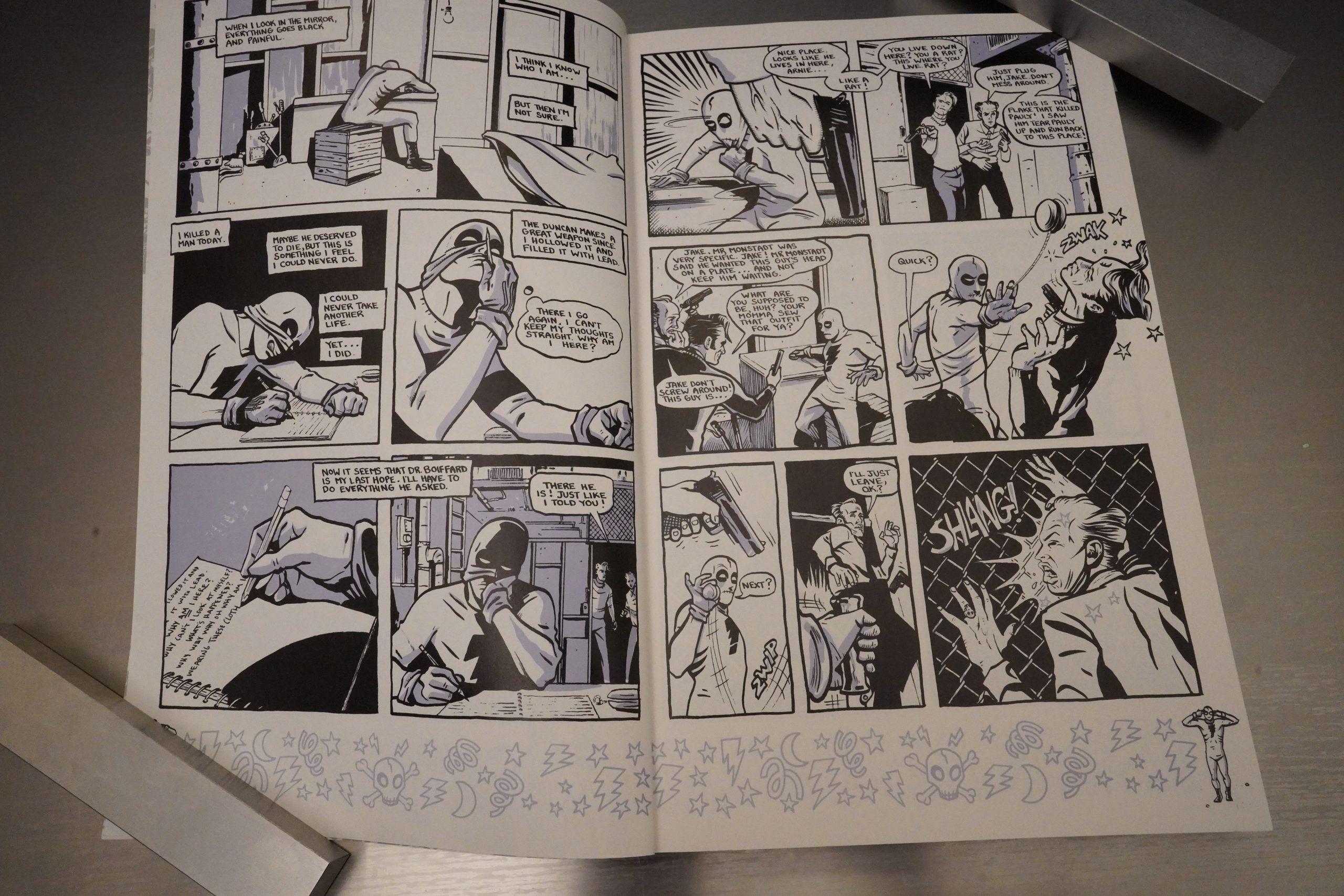

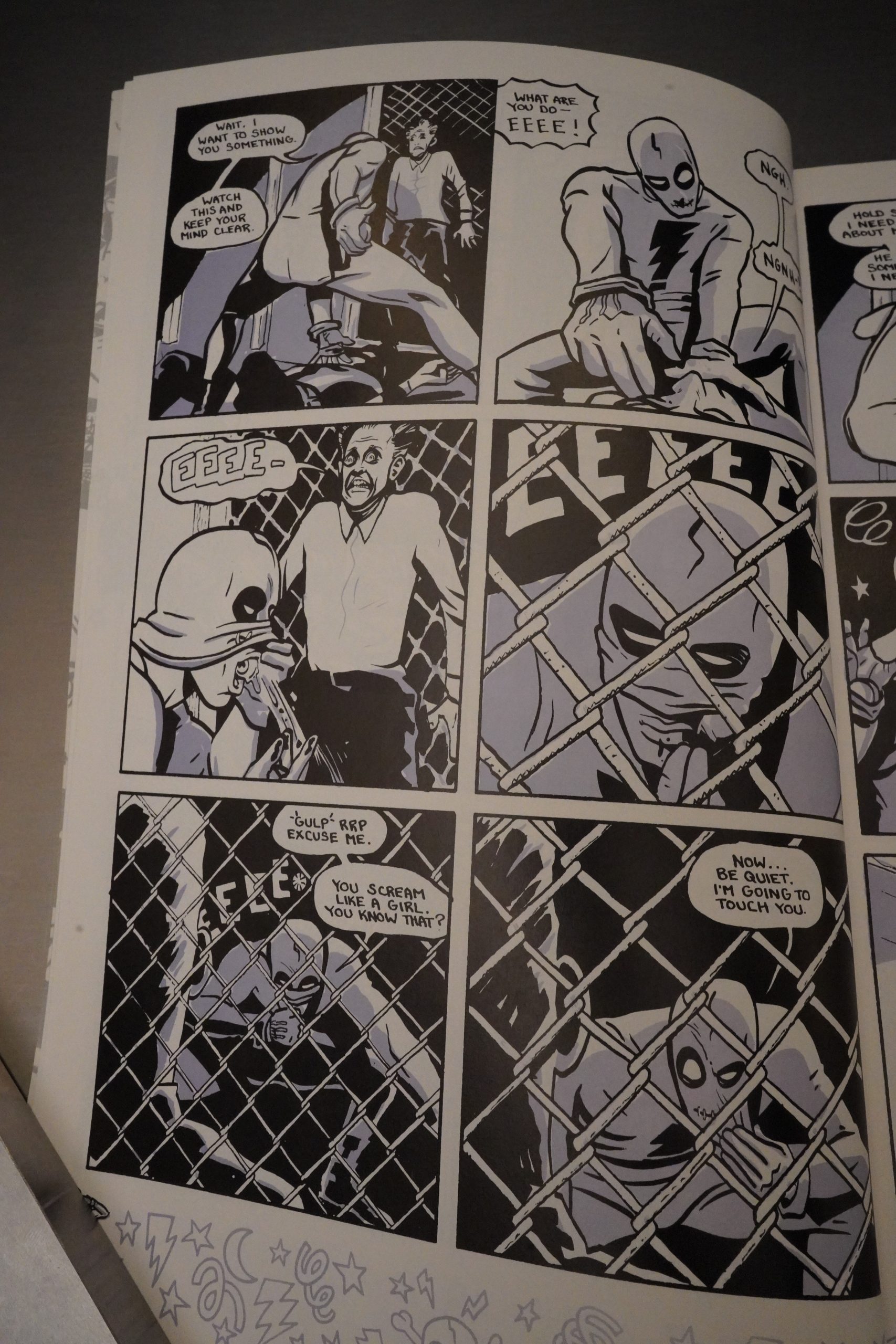

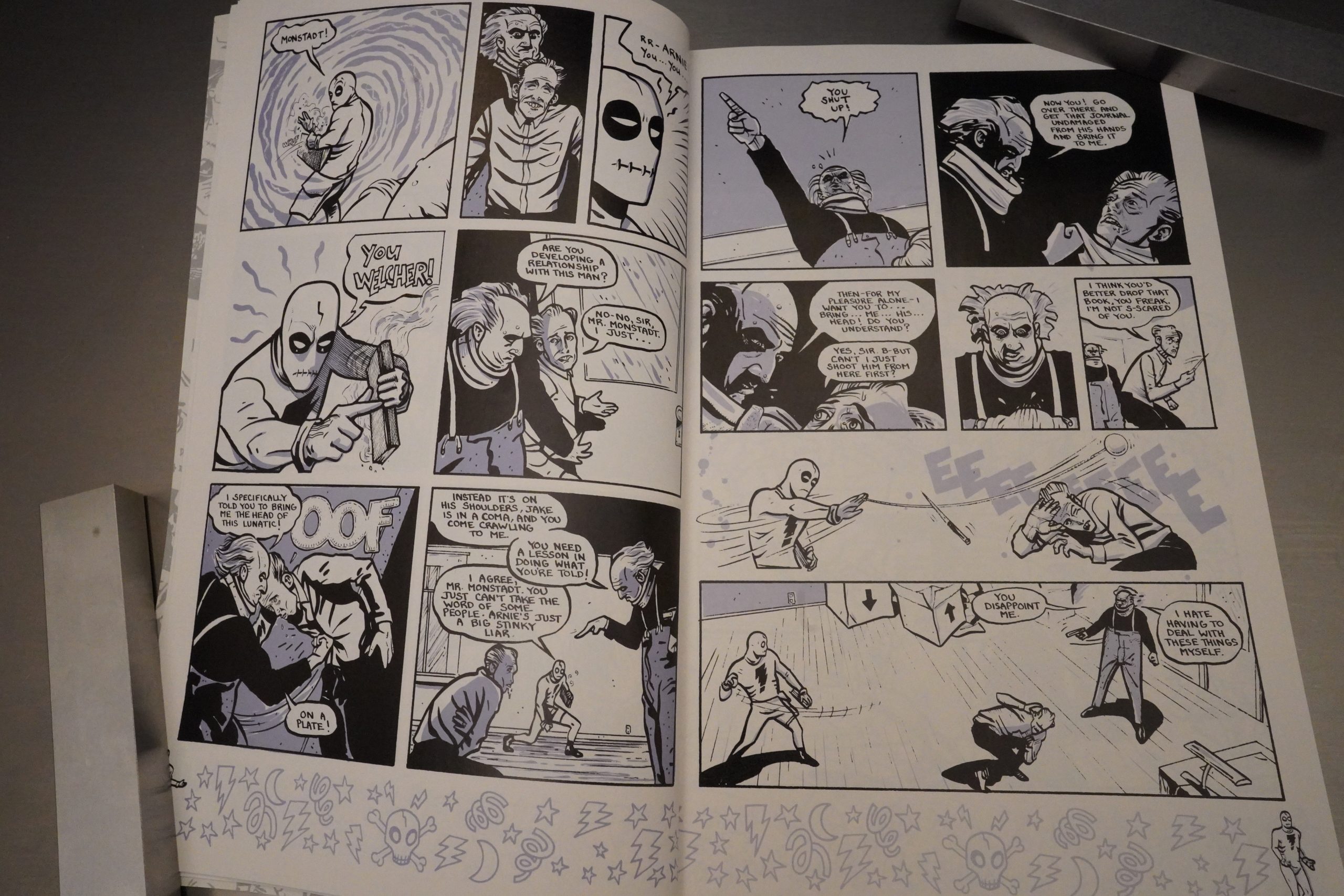

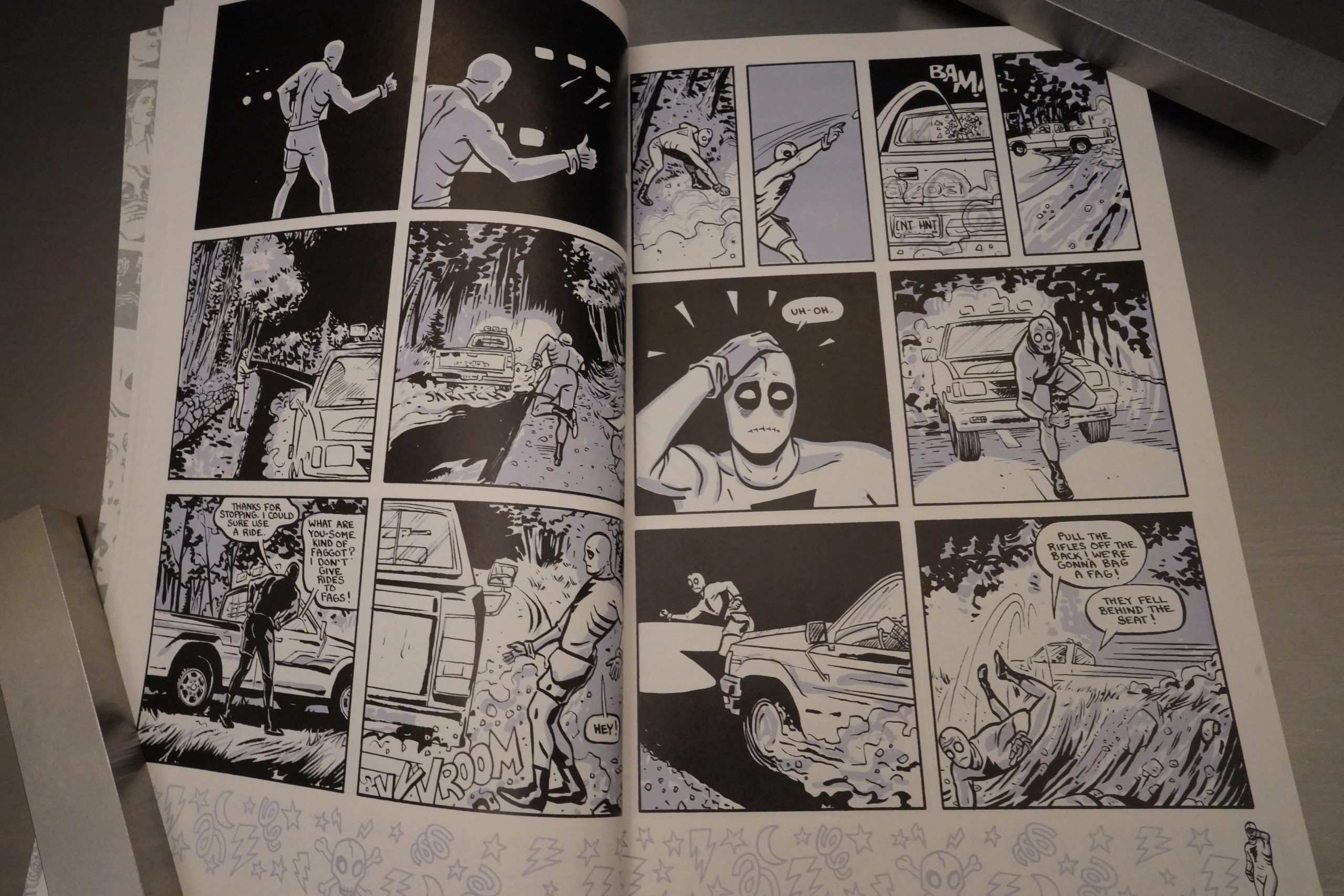

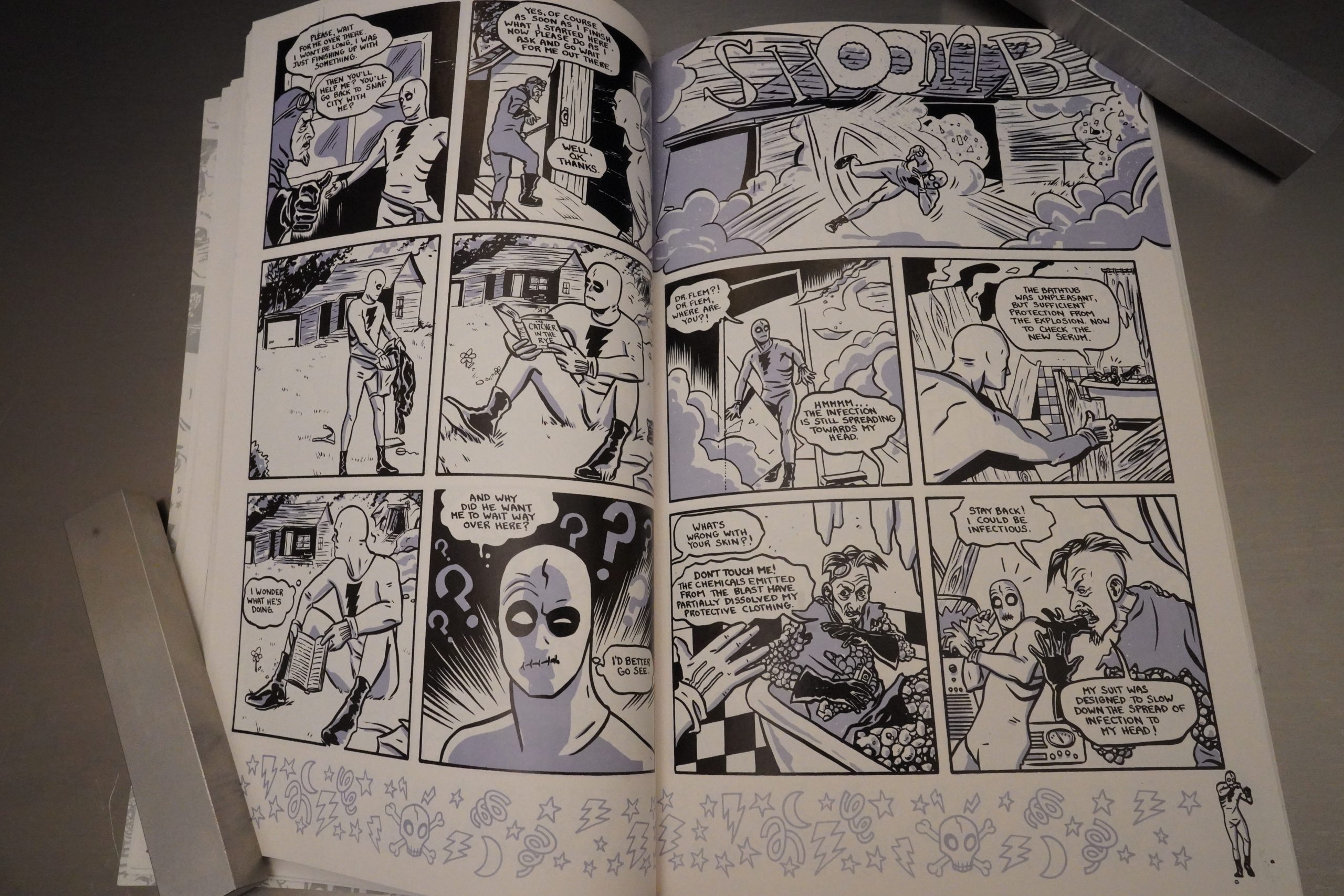

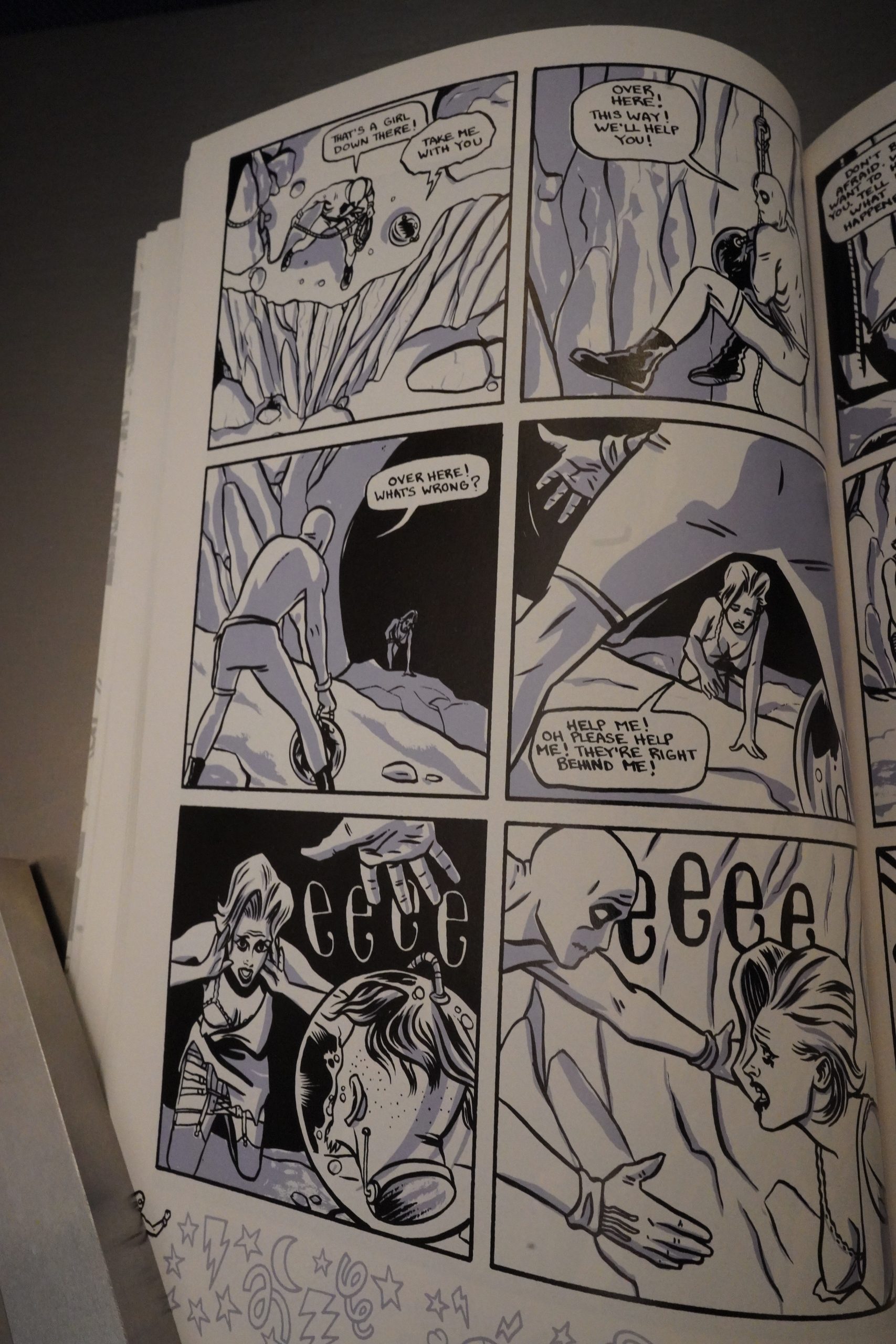

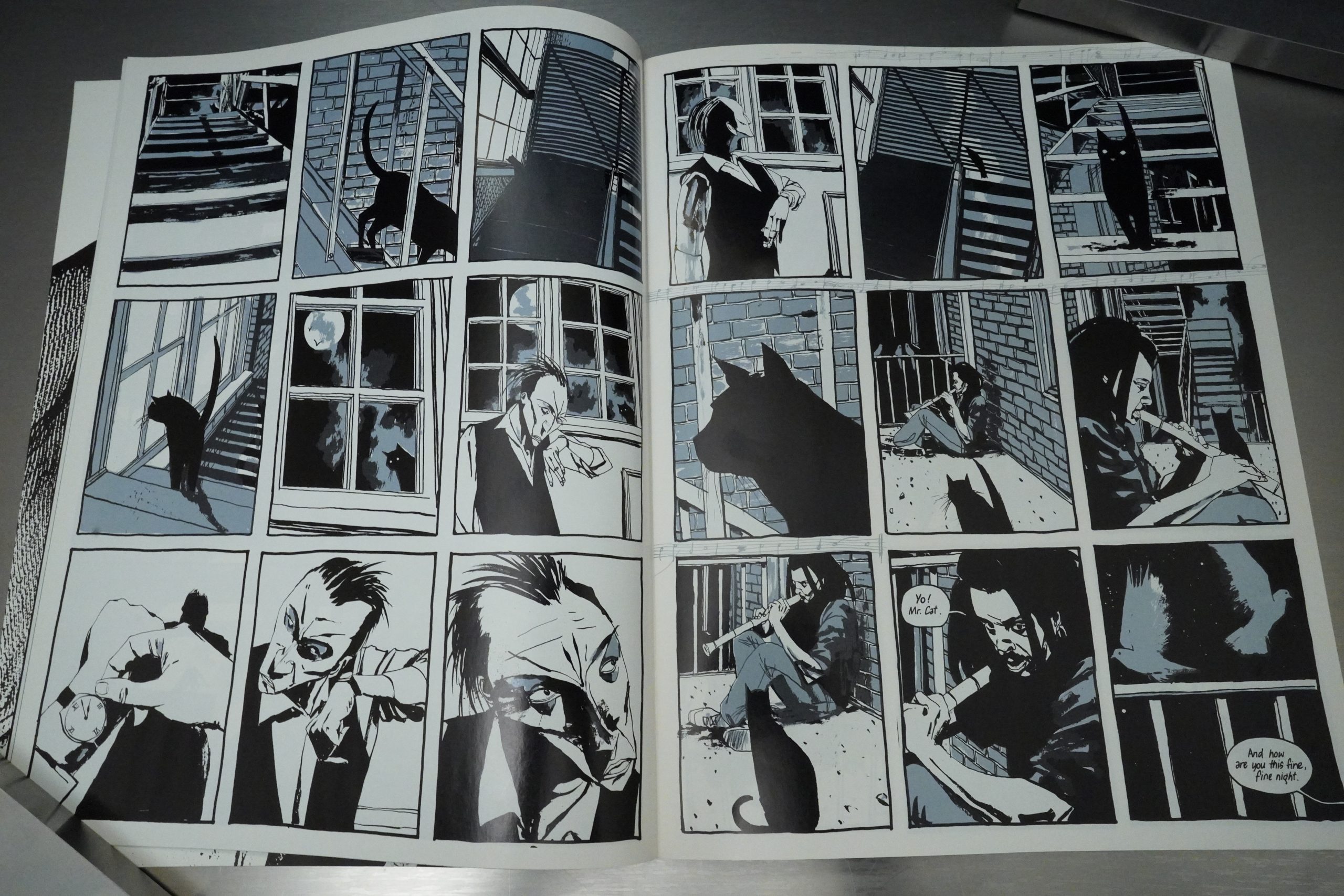

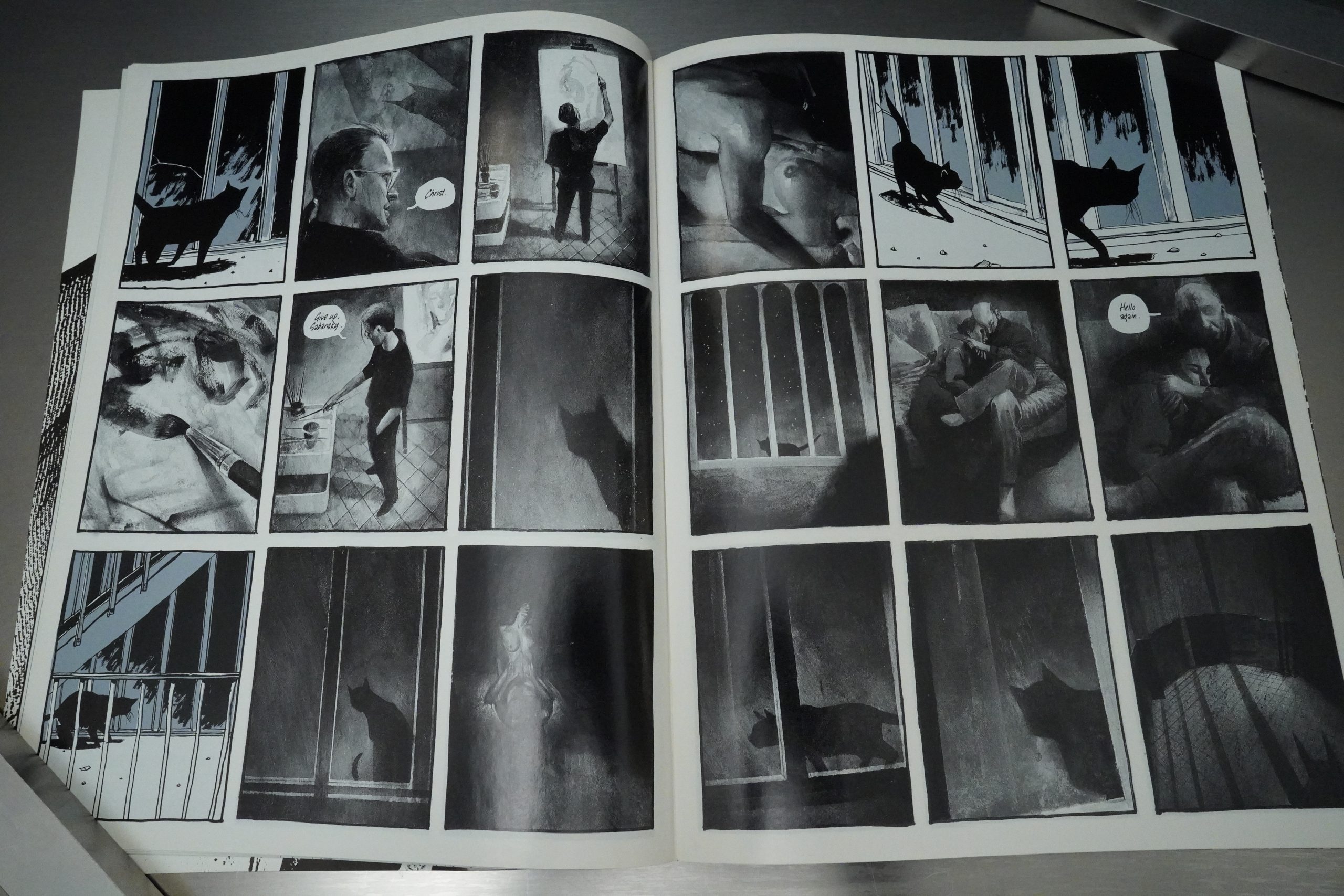

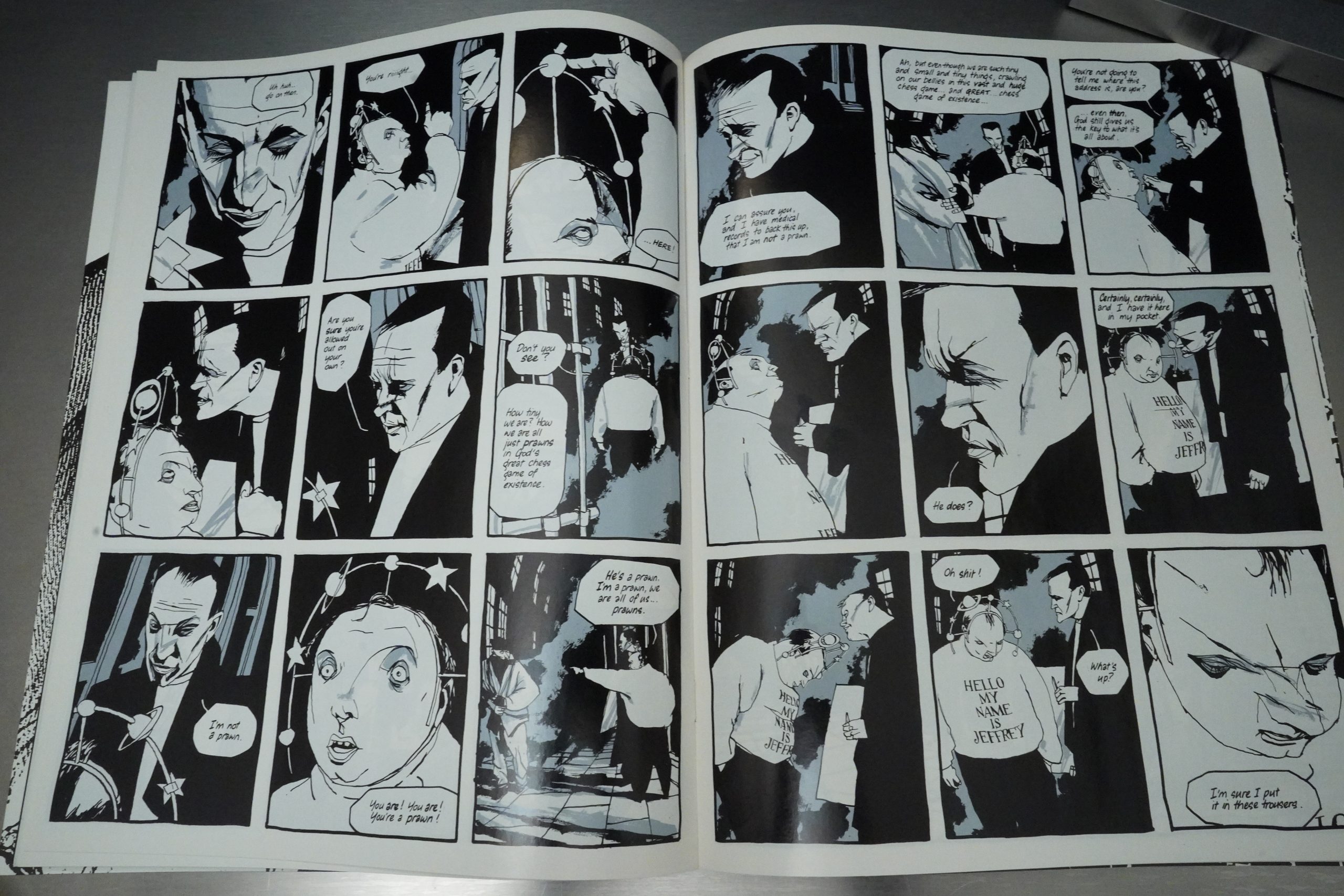

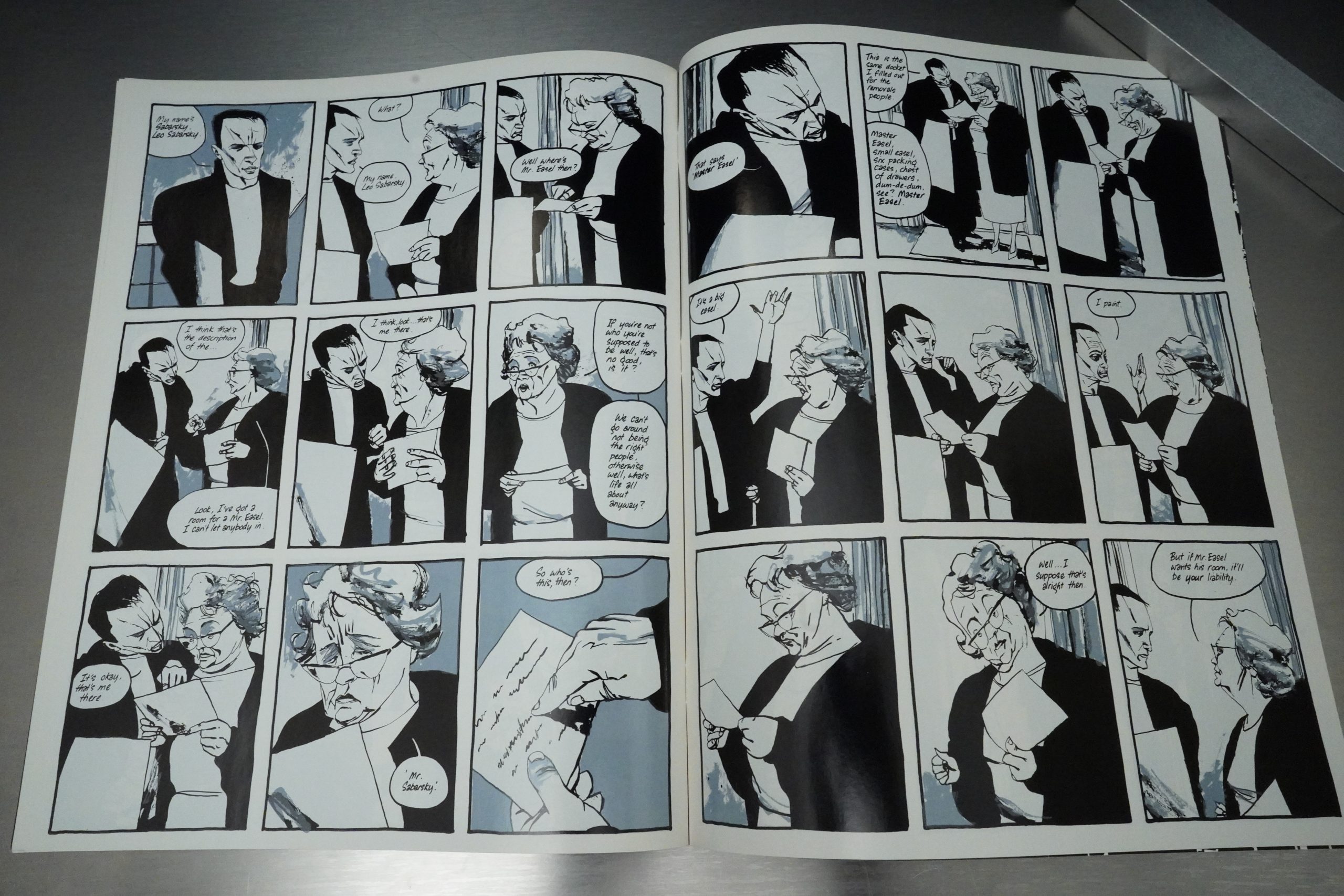

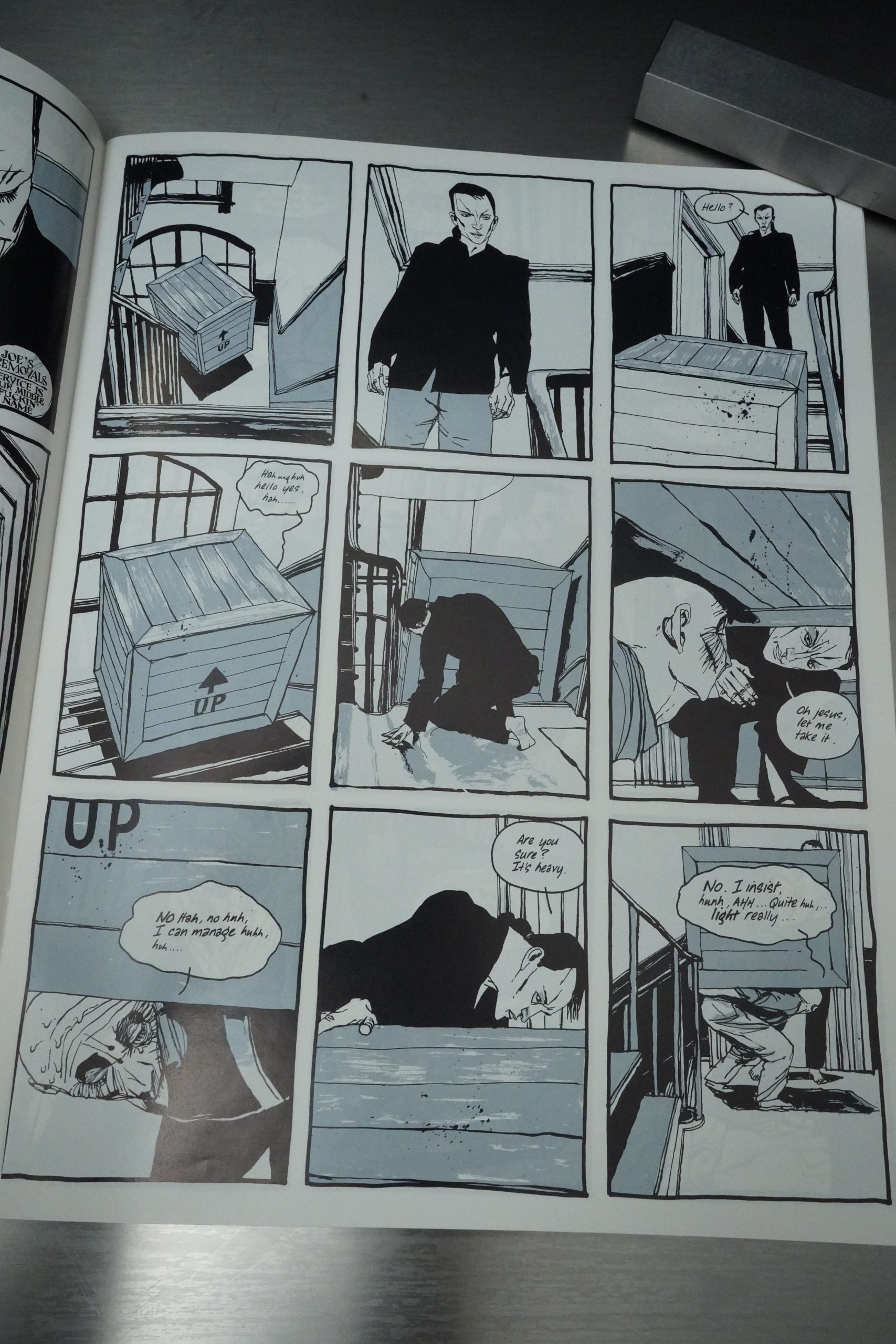

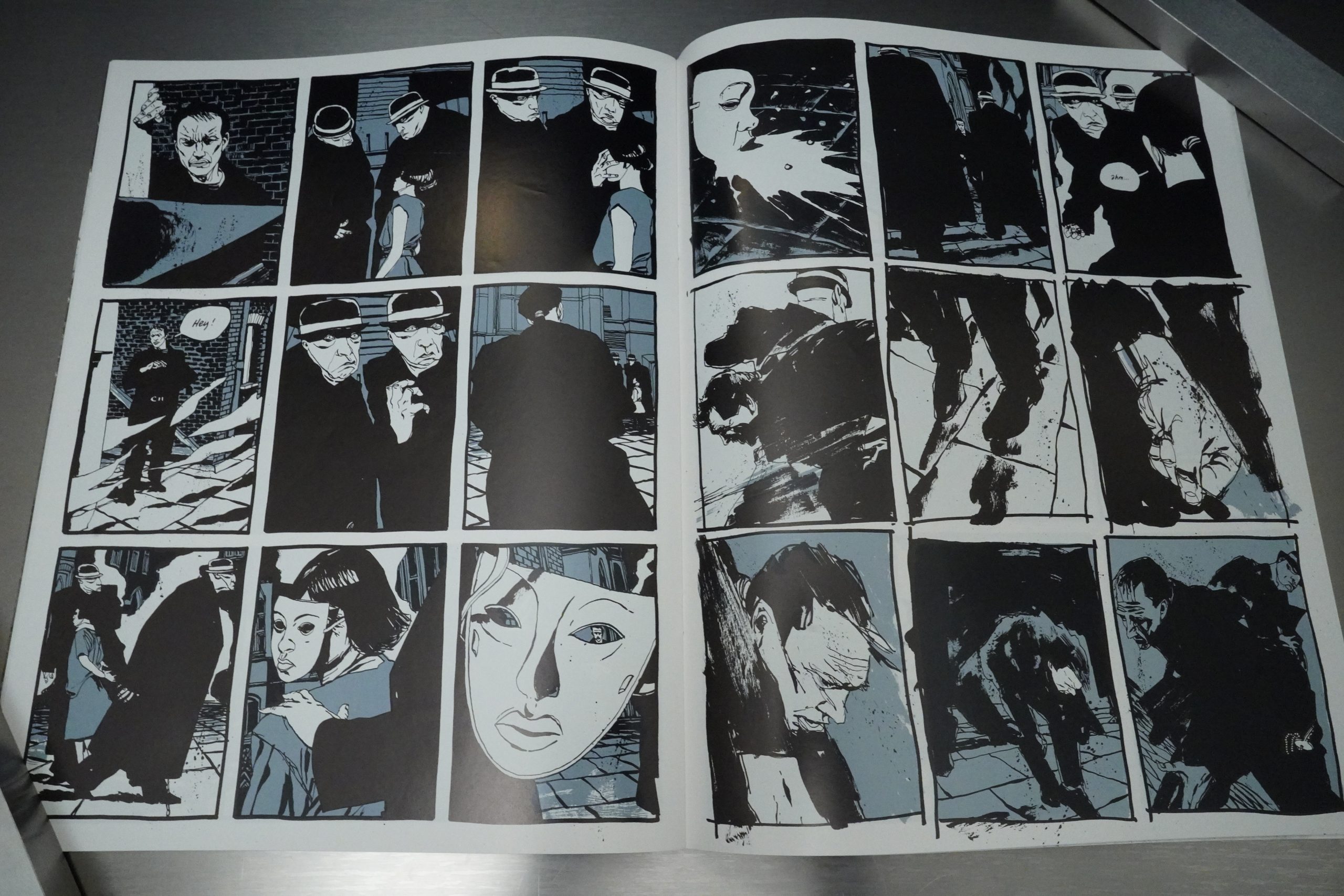

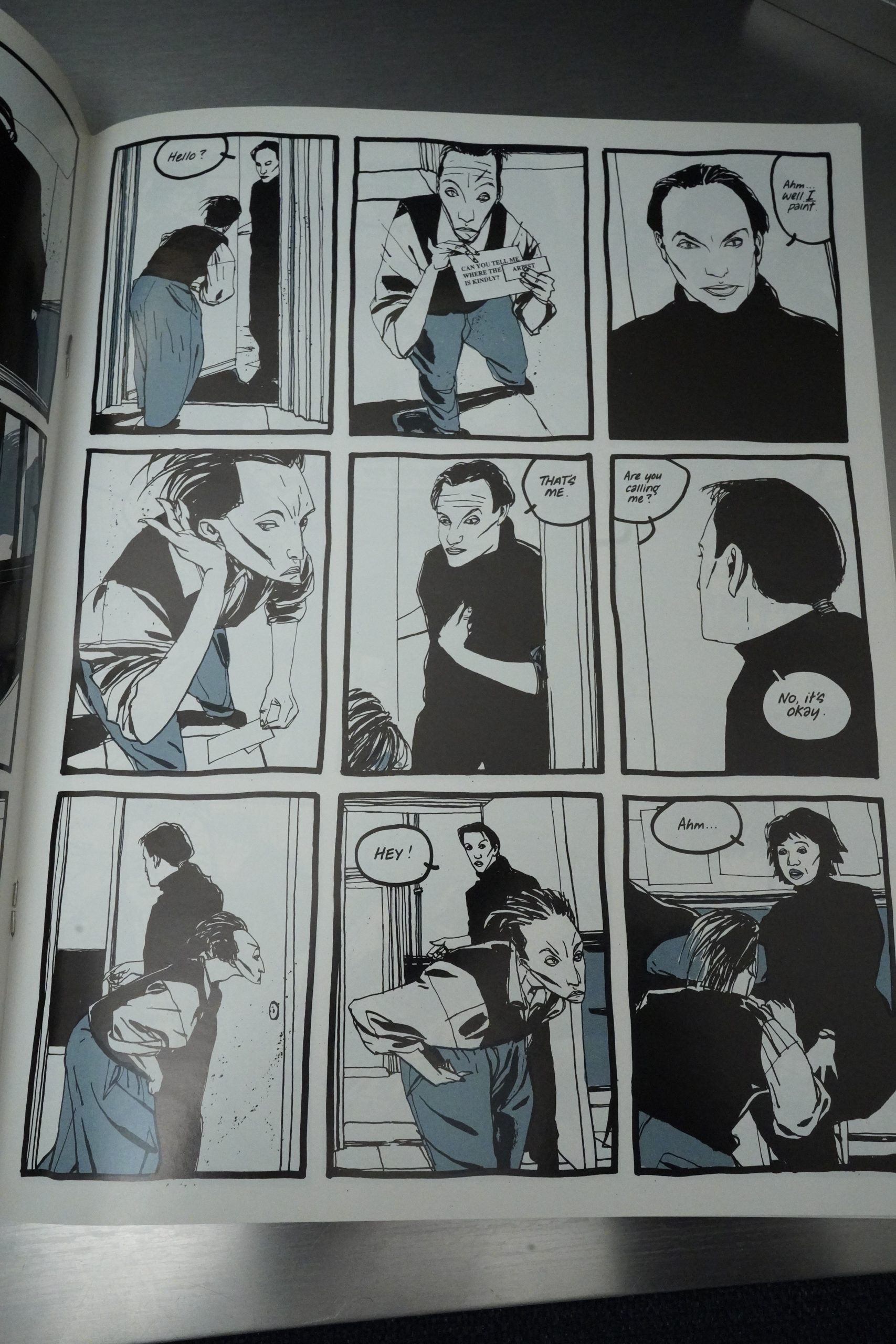

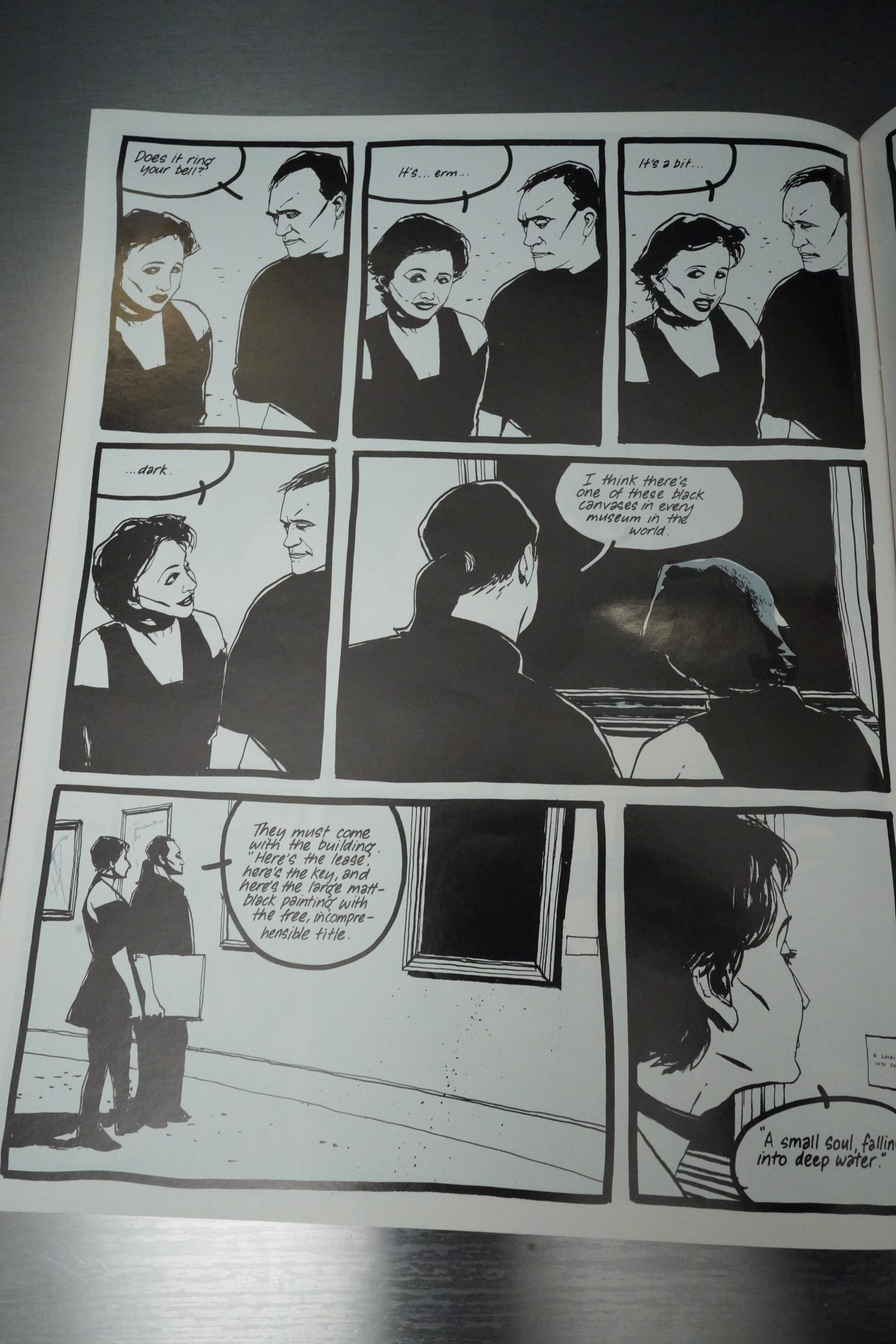

But when the book finally starts, it’s super sharp and intriguing. It’s got the then-fashionable nine panel grid going, and it’s printed with an extra ink — a grey that’s ever-so-slightly metallic? It looks really good.

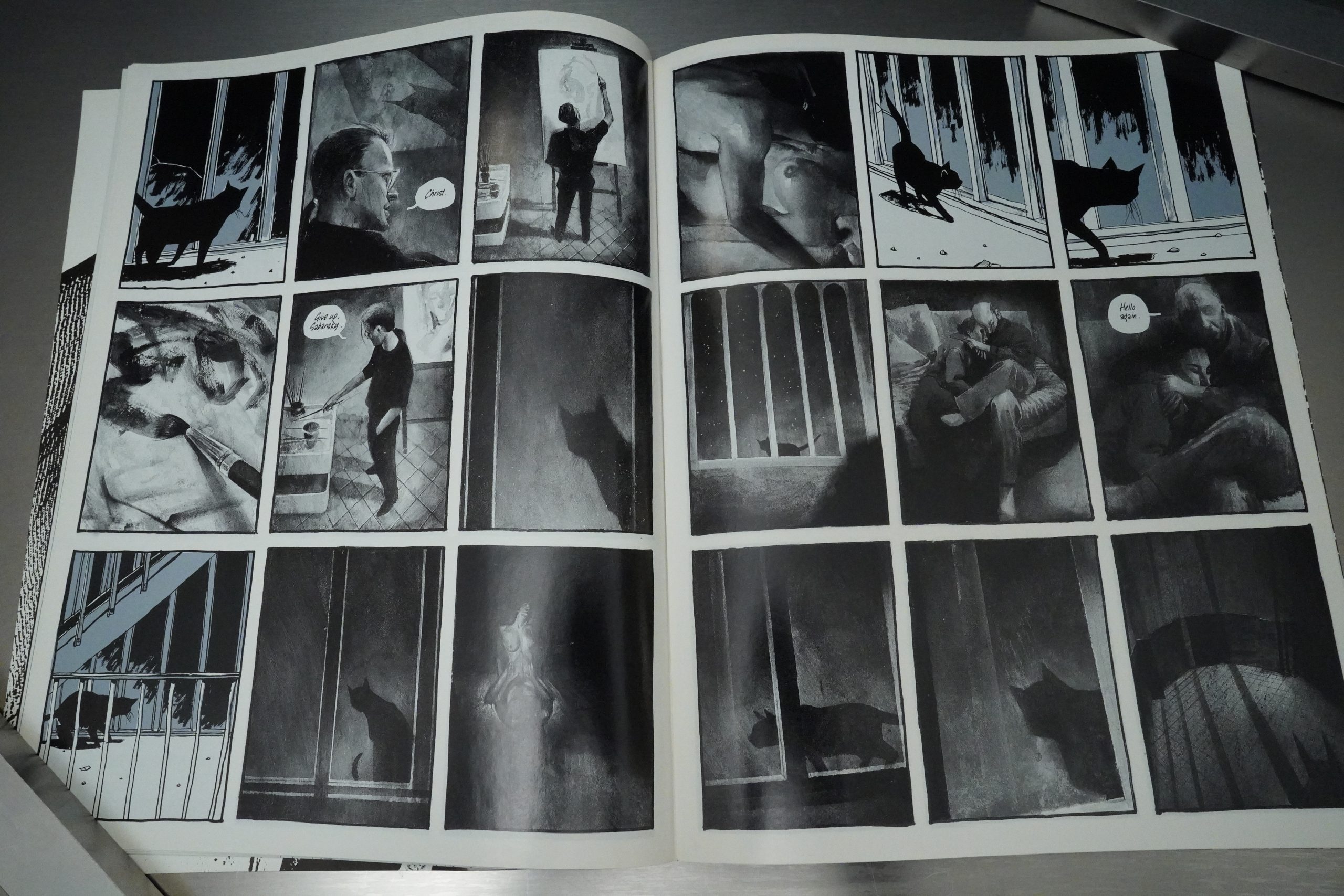

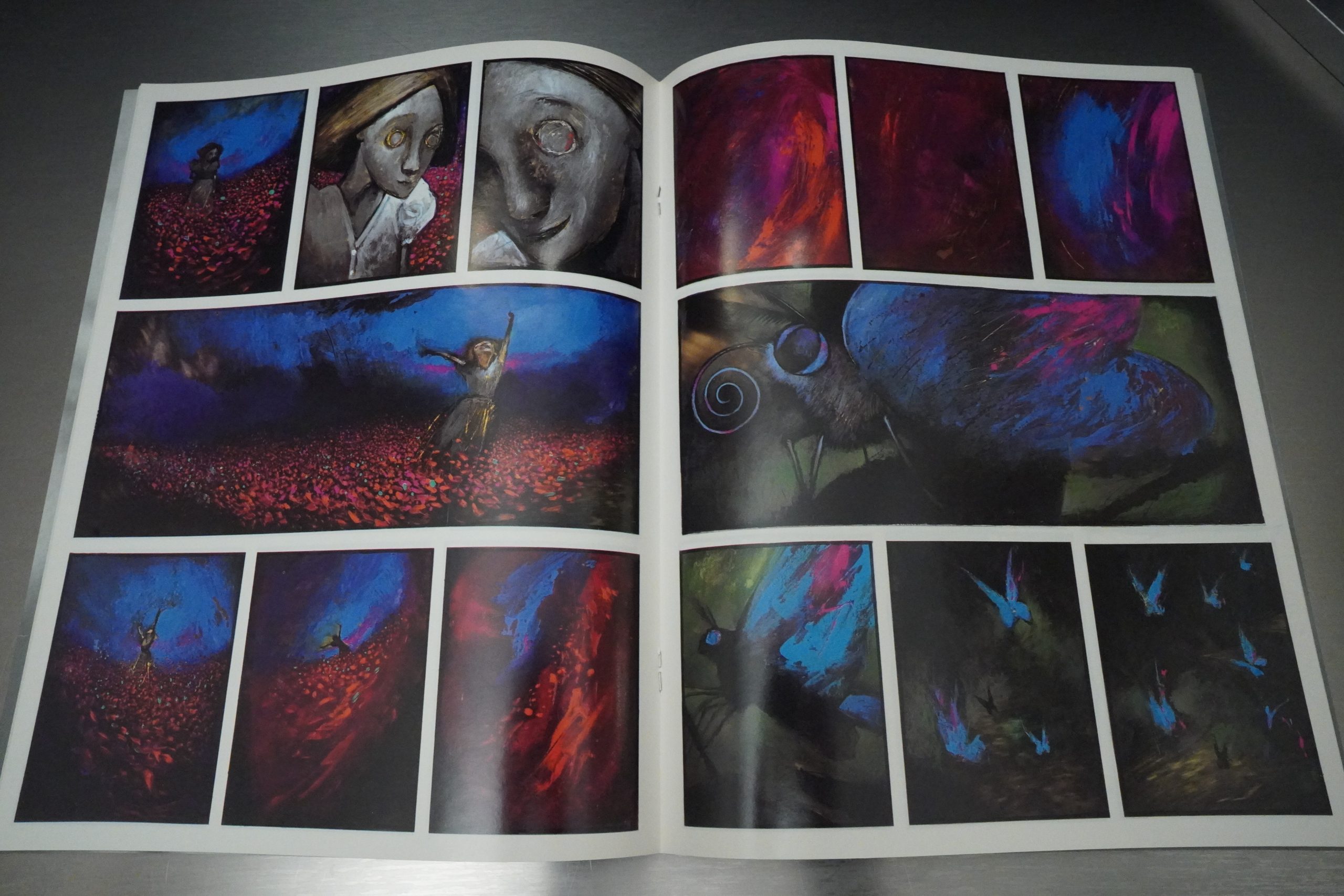

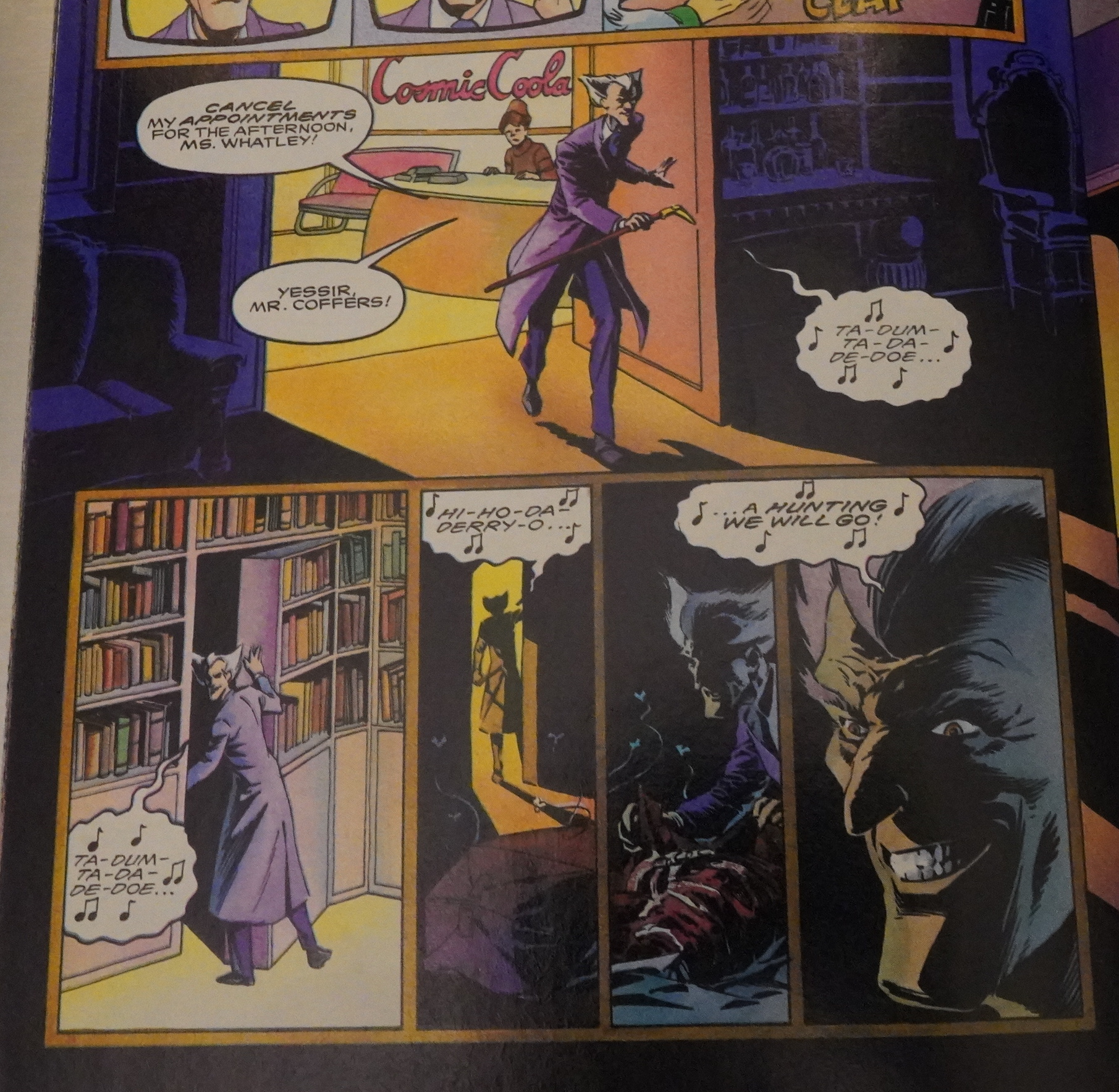

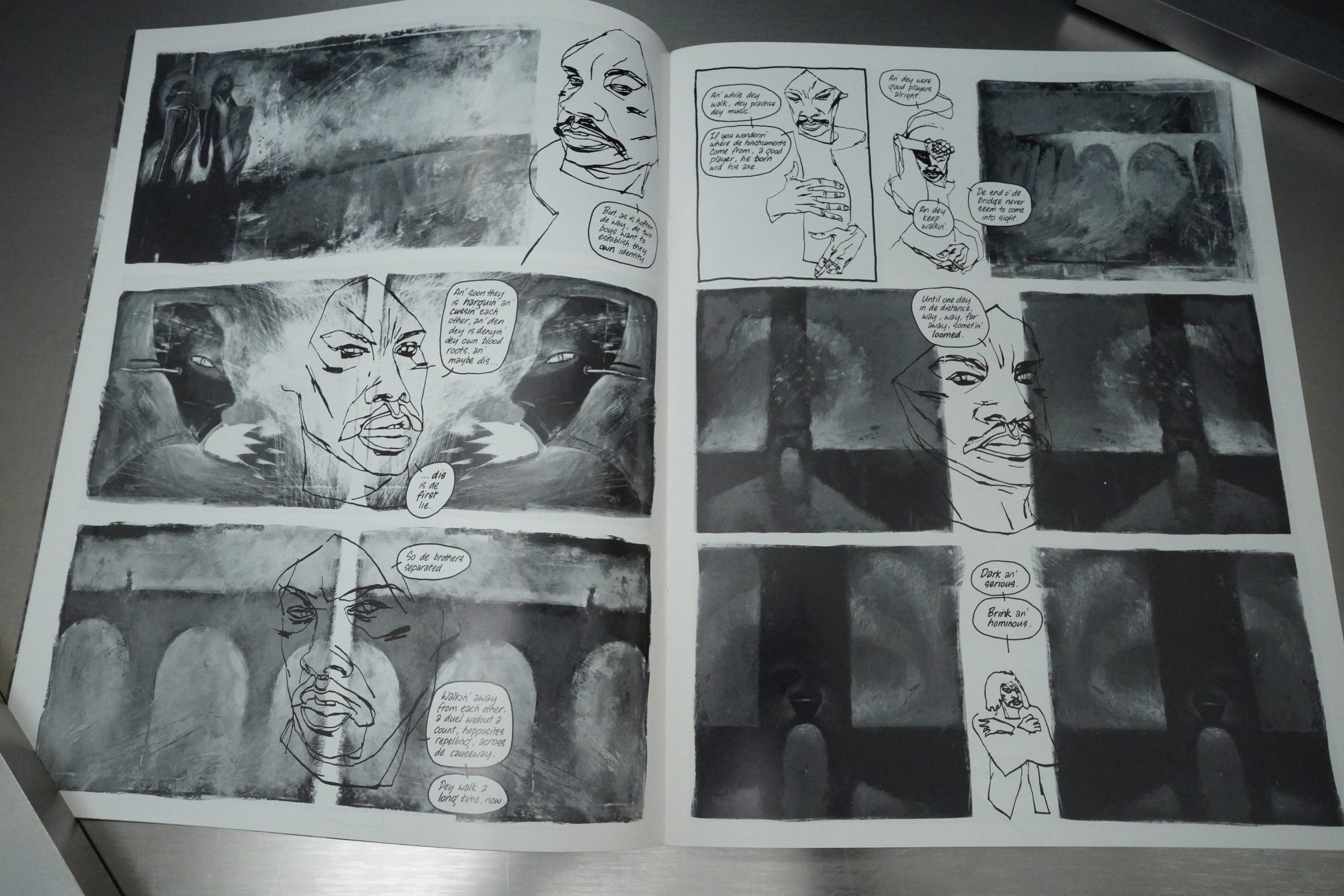

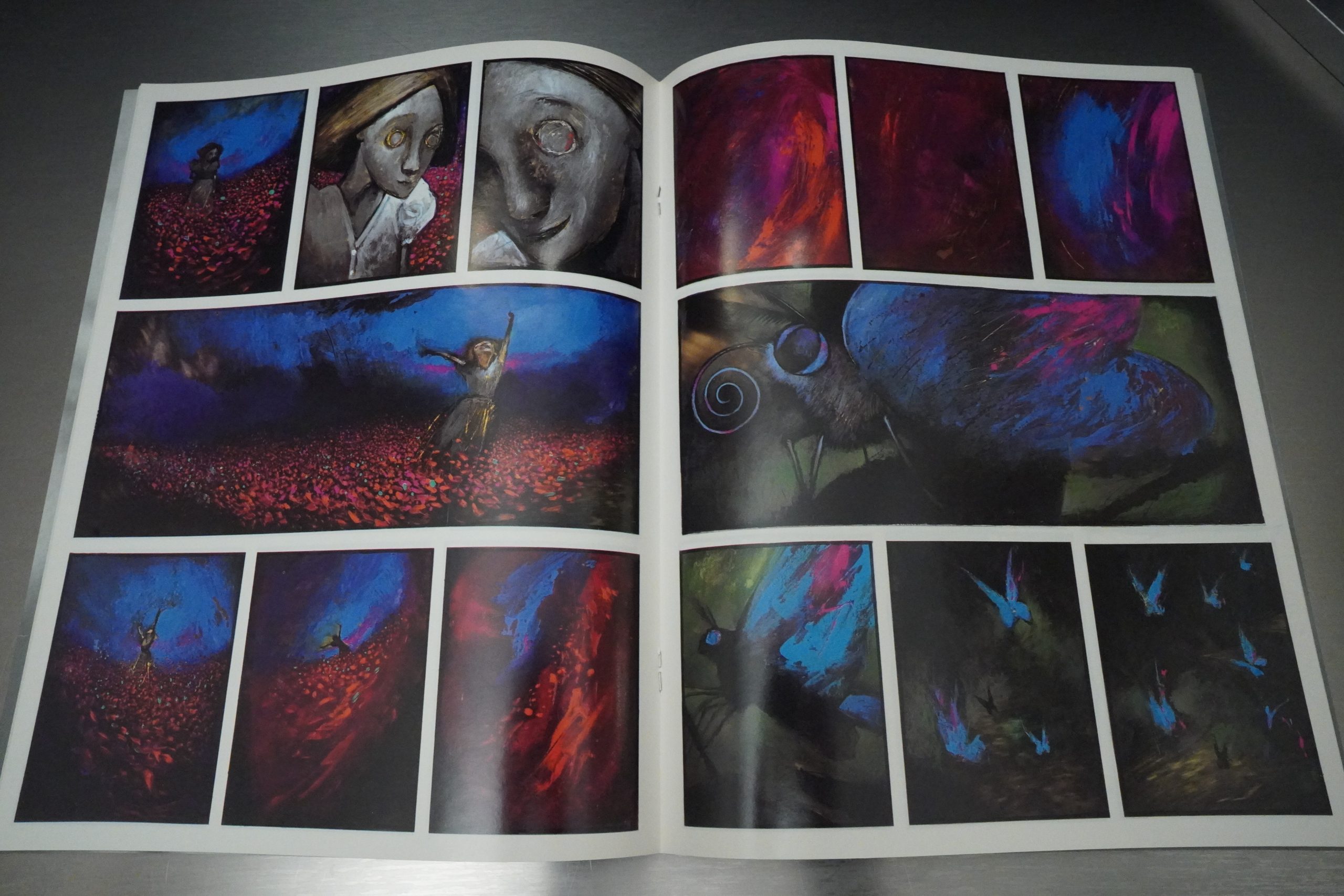

And it’s mysterious as hell, and has a cat that can apparently look into the past (that’s not immediately clear, but becomes obvious by the end of the first issue), and in the future, things are done in grey washes, because sure.

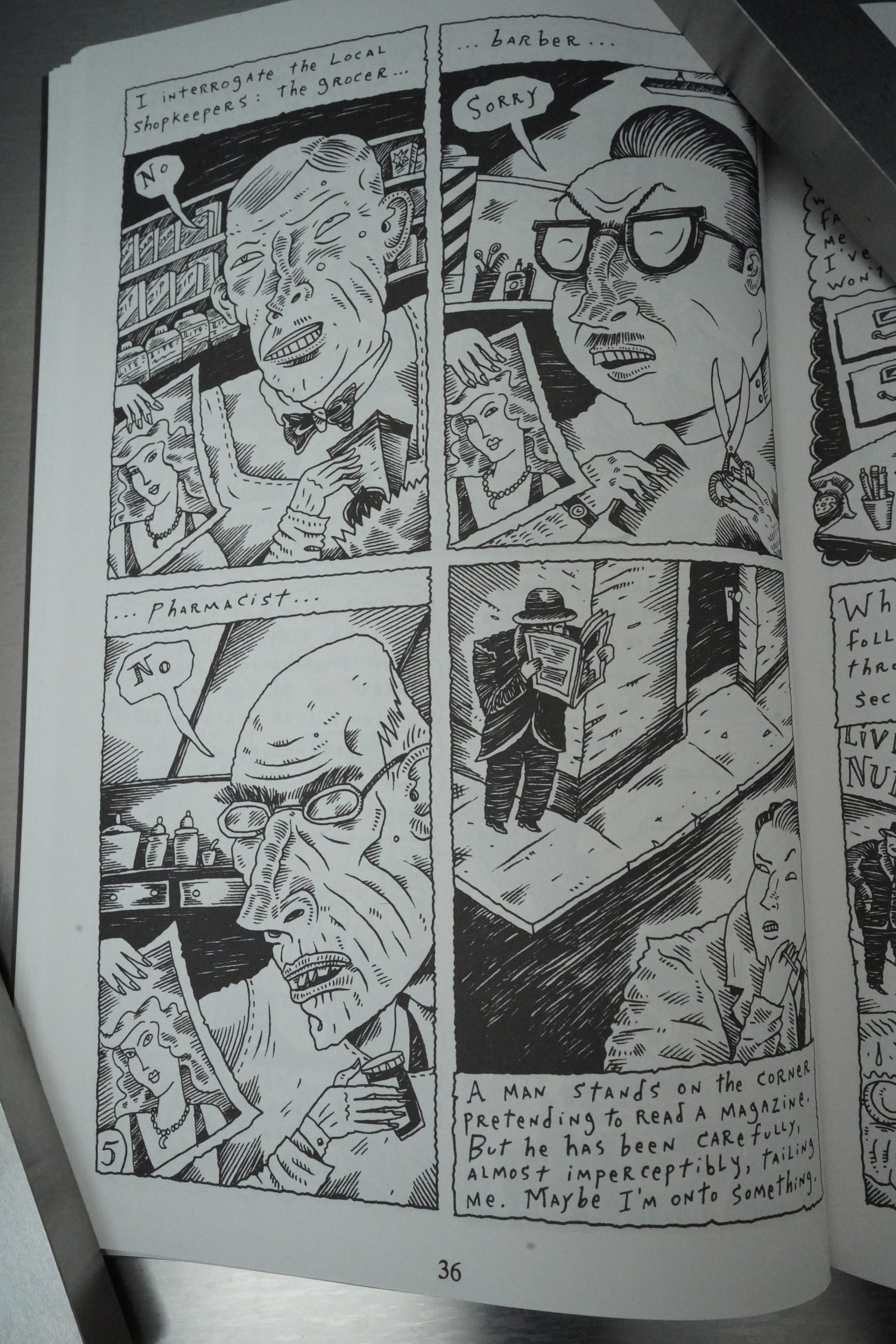

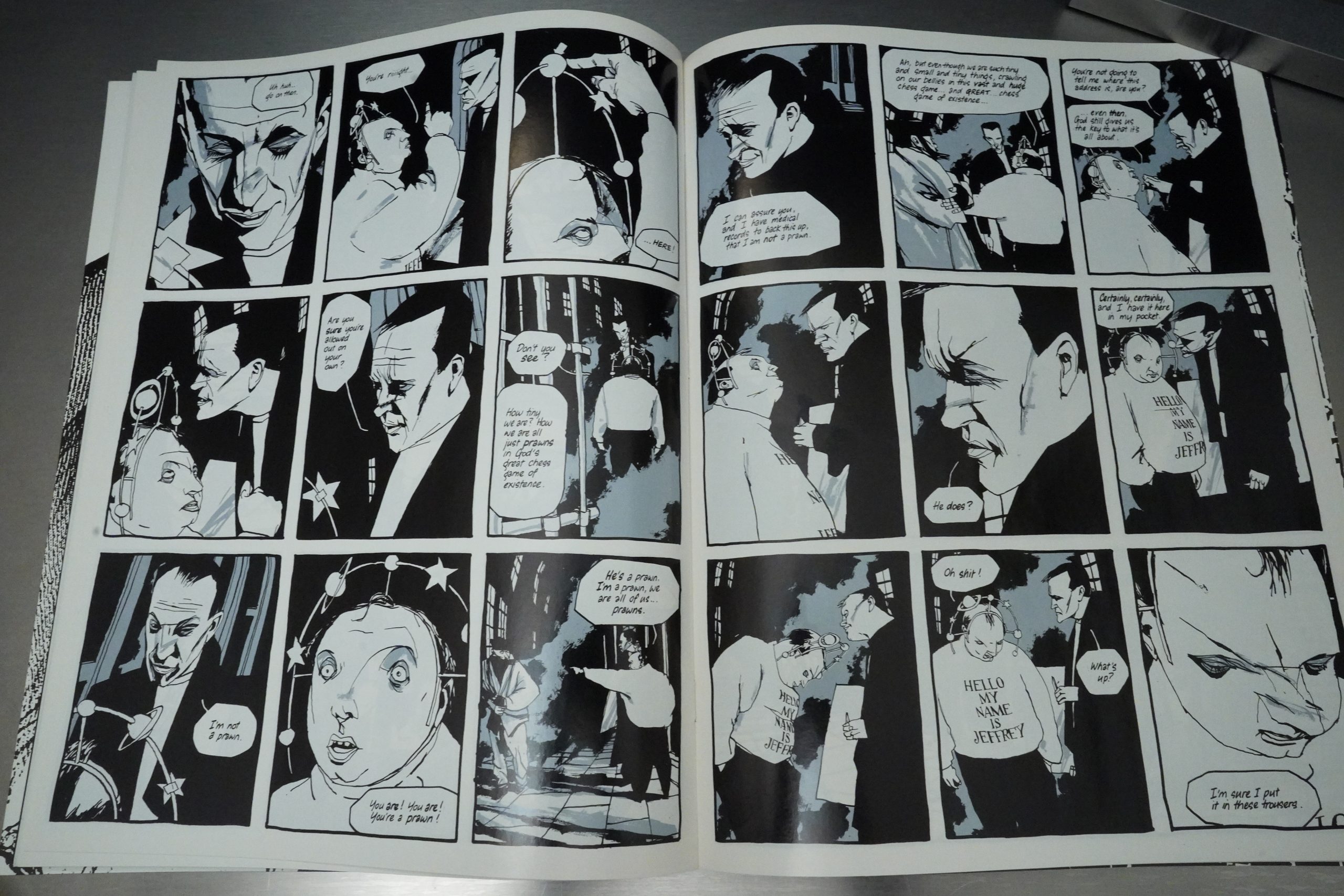

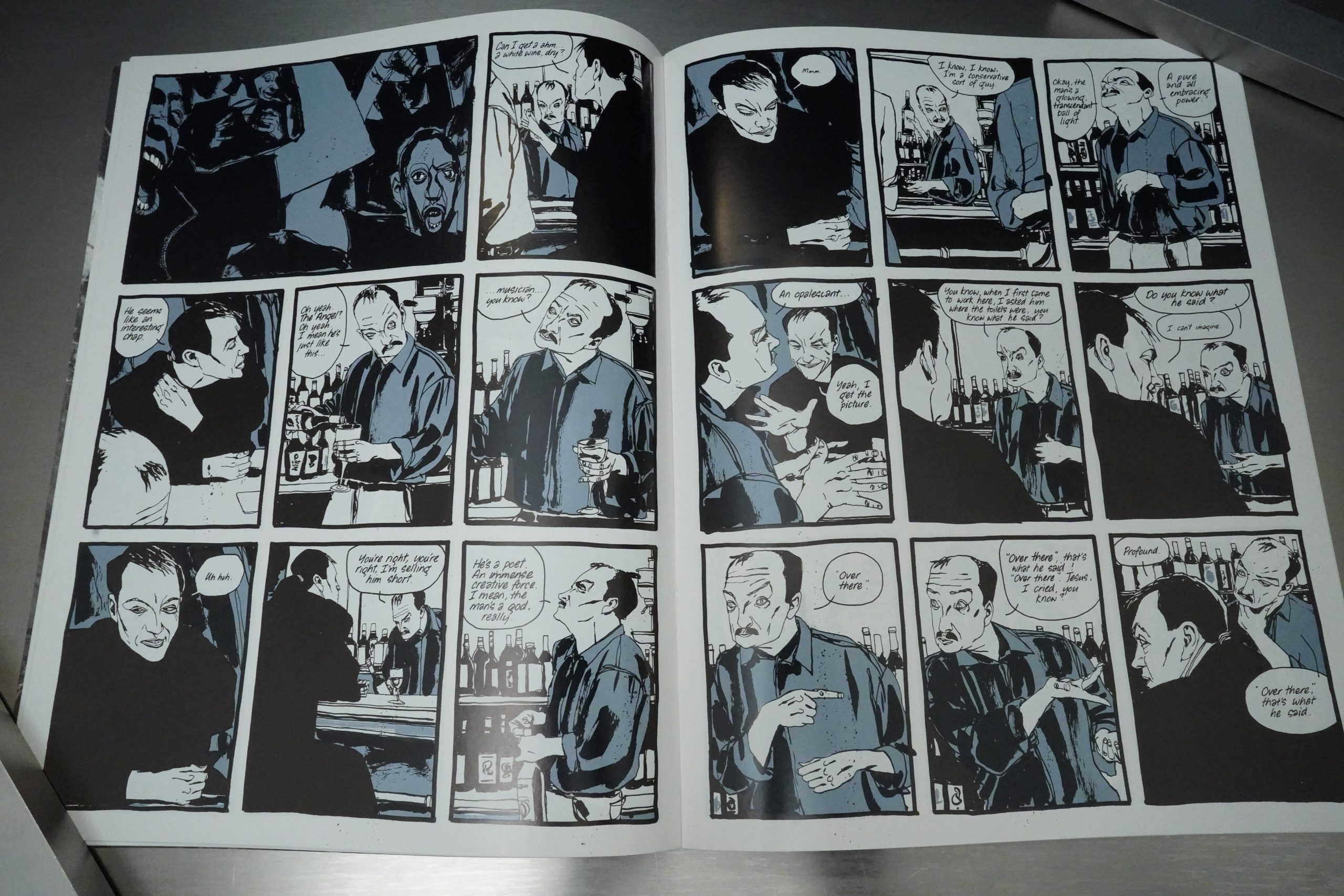

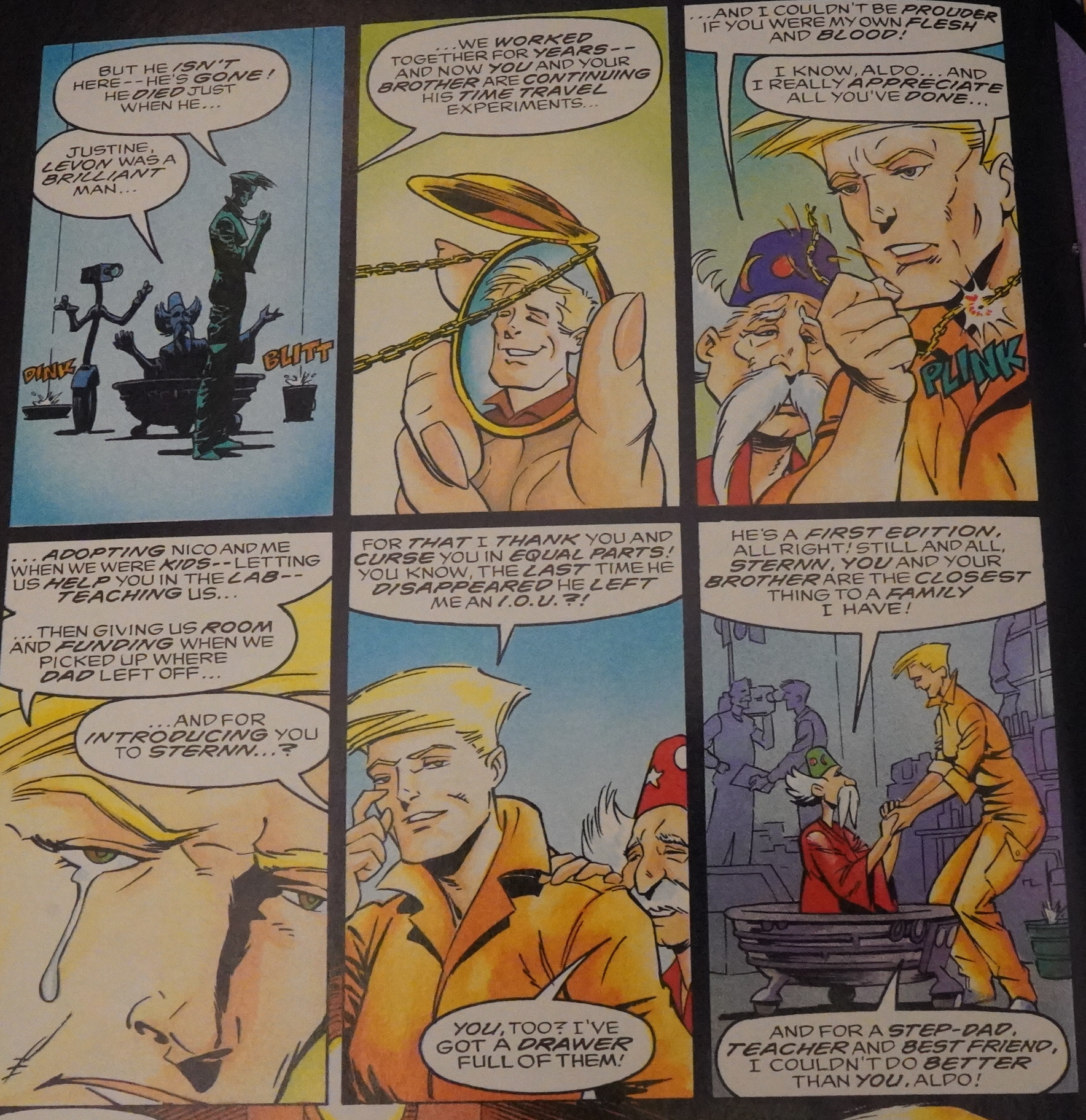

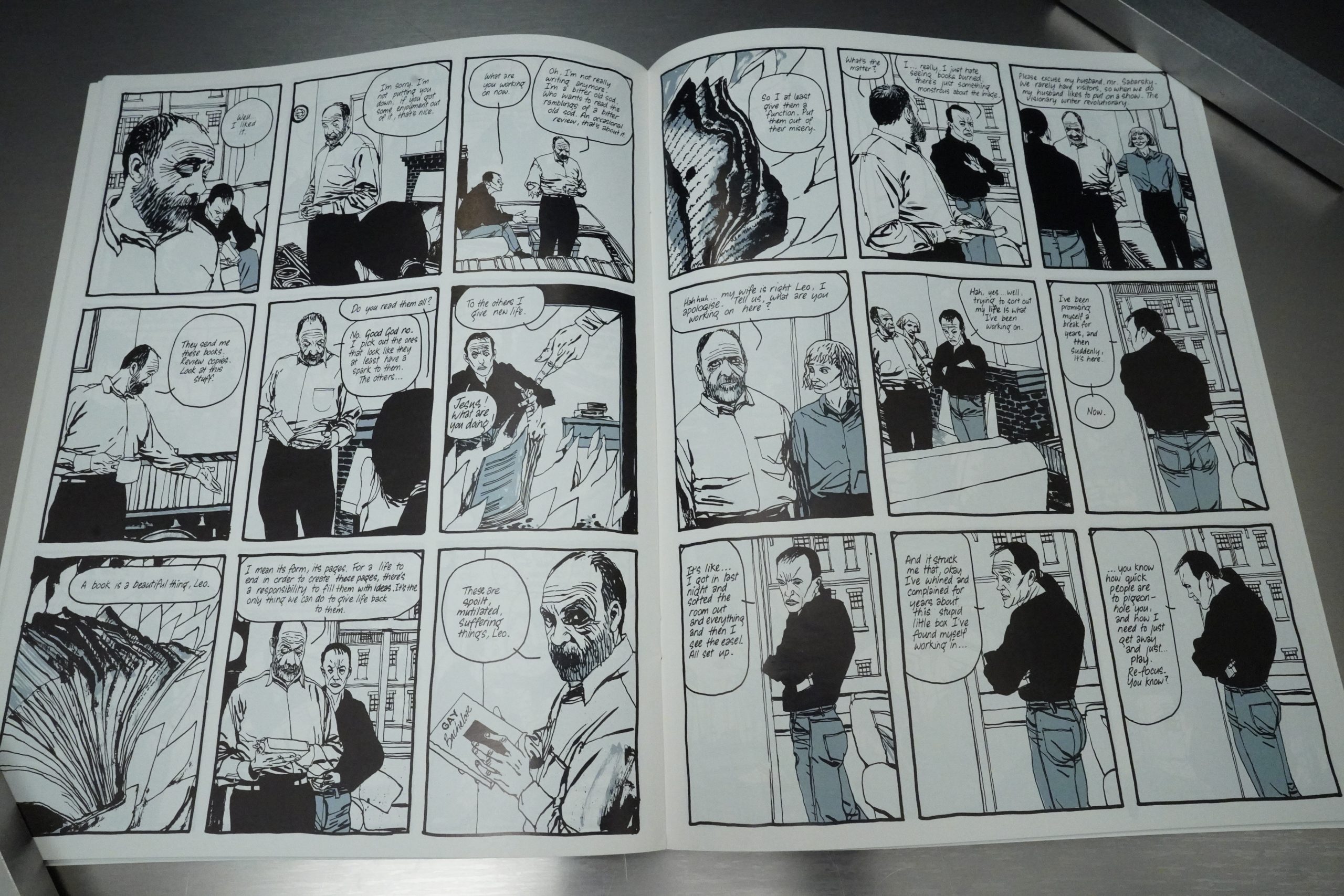

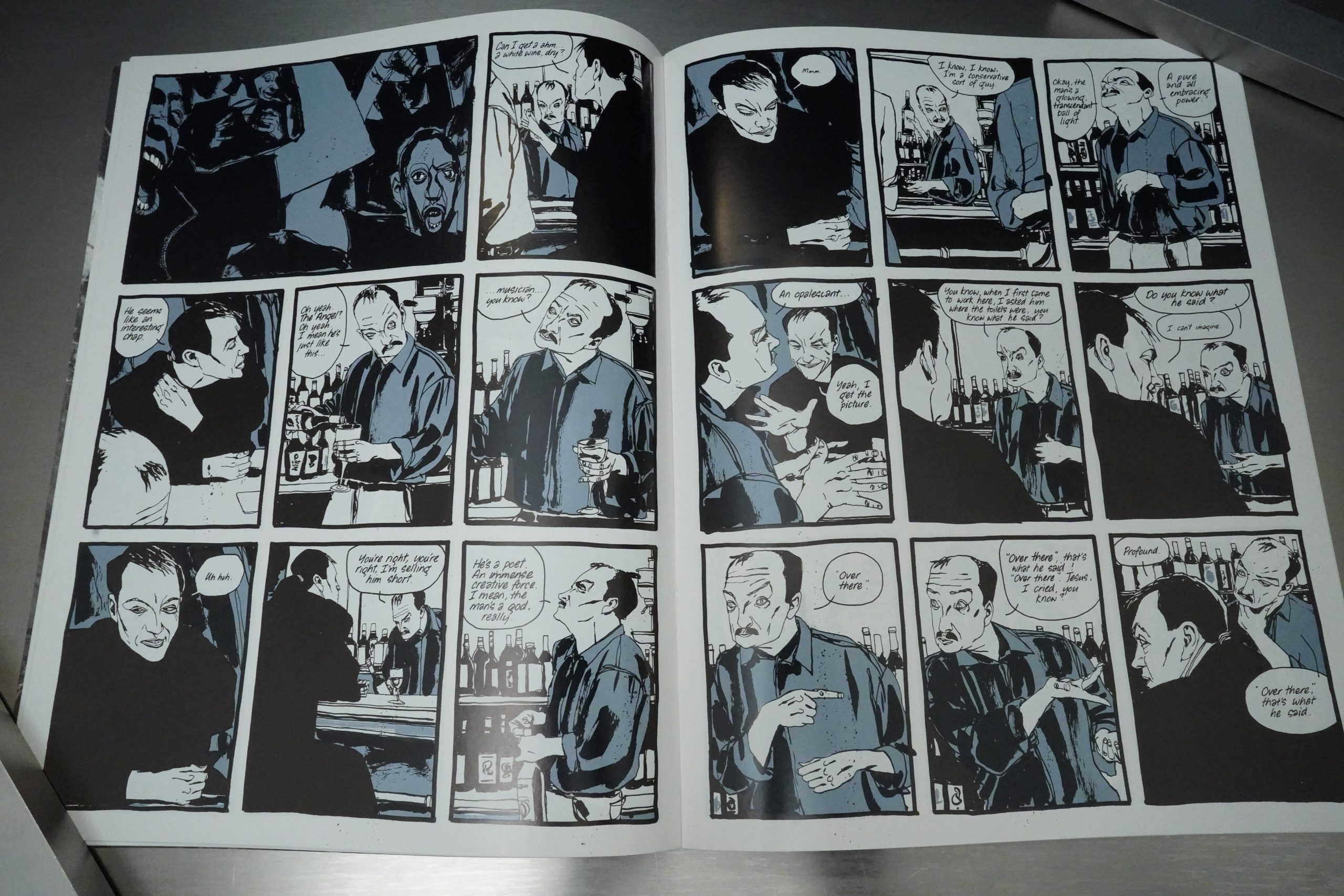

McKean ladles up one quirky character after another.

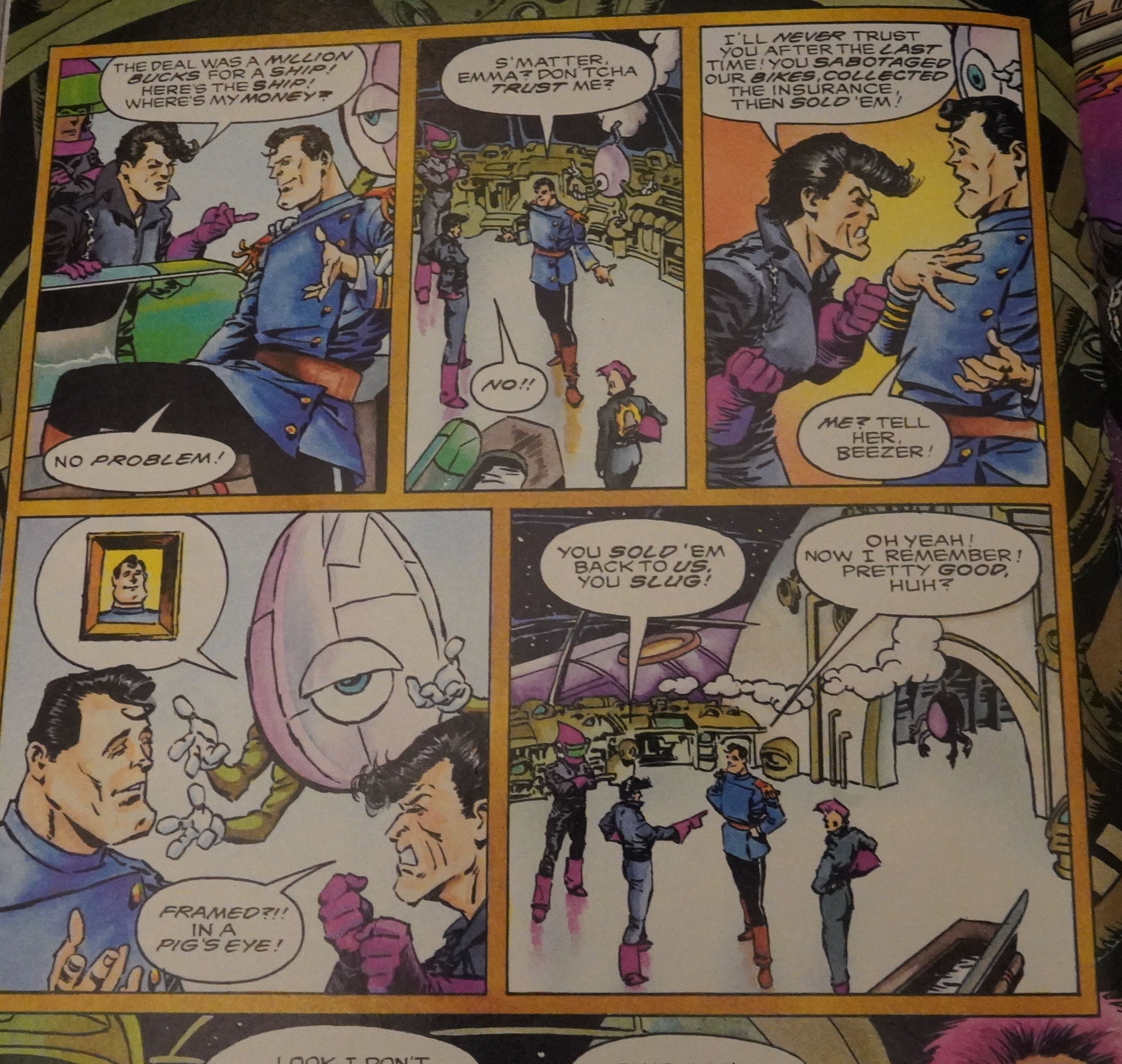

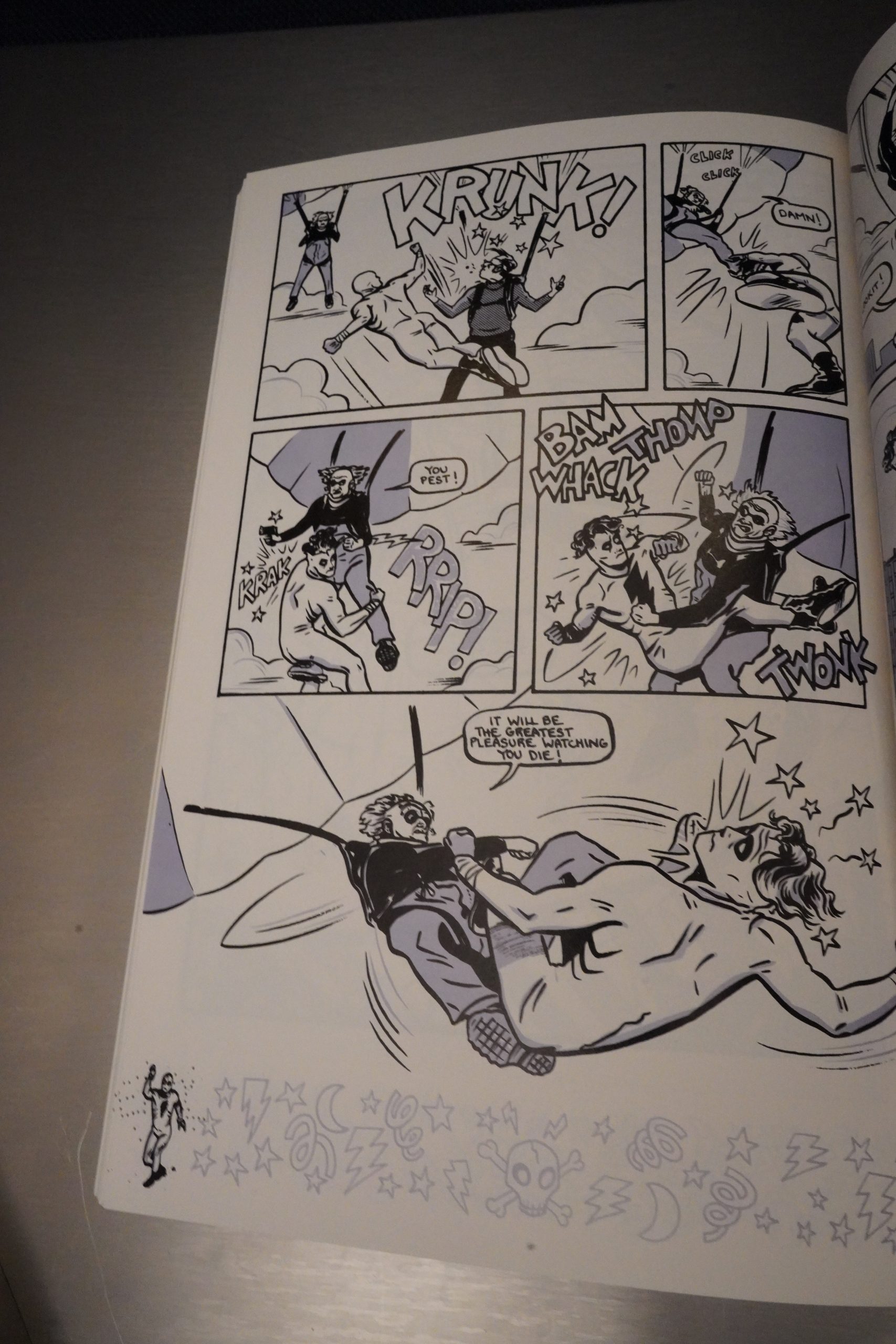

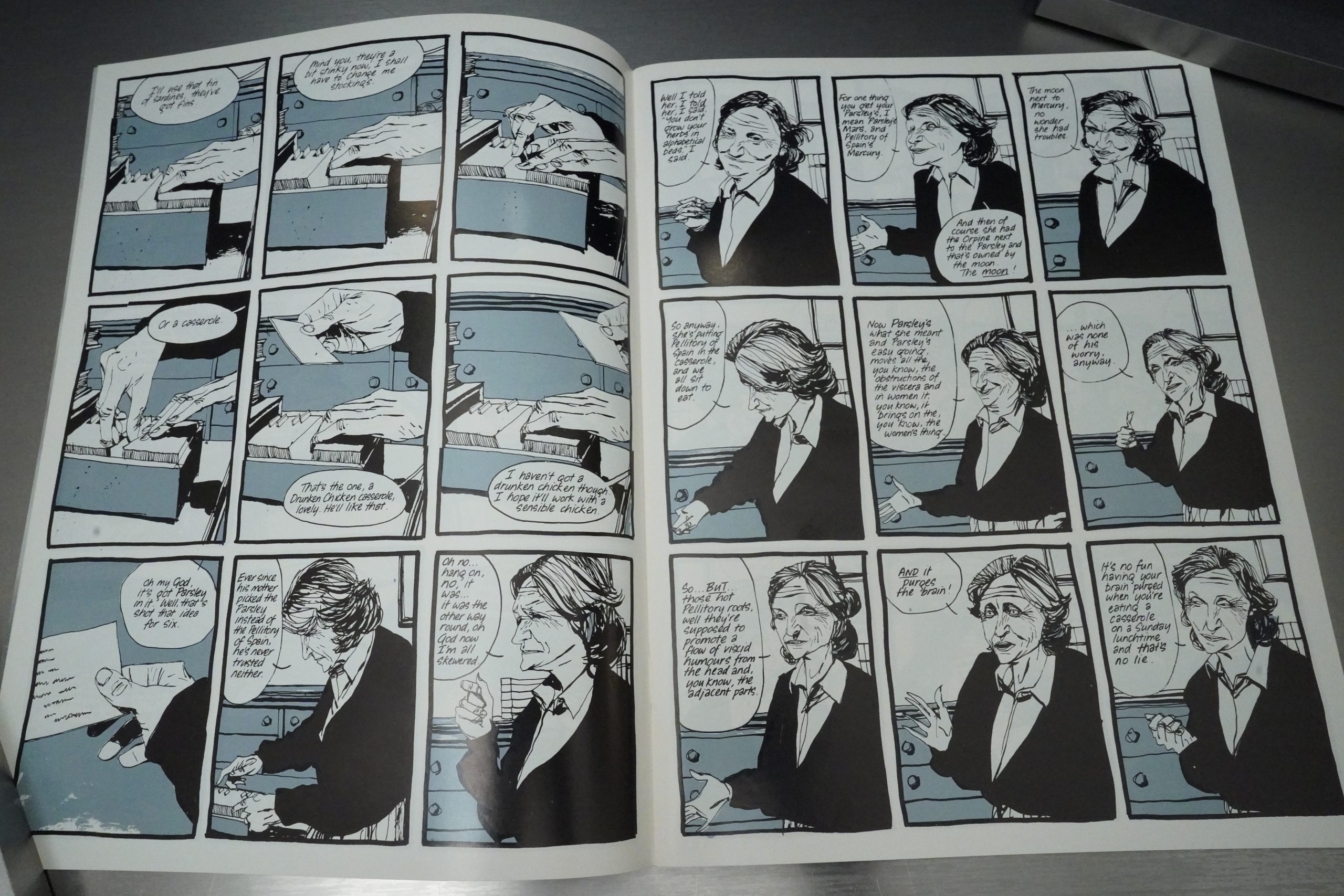

And he does several scenes of vaudeville schtick, and we never find out who’s on third.

It’s a really strong first issue — amazing artwork, many mysteries hinted at, and comedy routines at the drop of a hat.

So the second issue didn’t happen until six months later. But the next handful of issues did arrive quite promptly — three or four months in between, which I think is pretty impressive for a book of this kind.

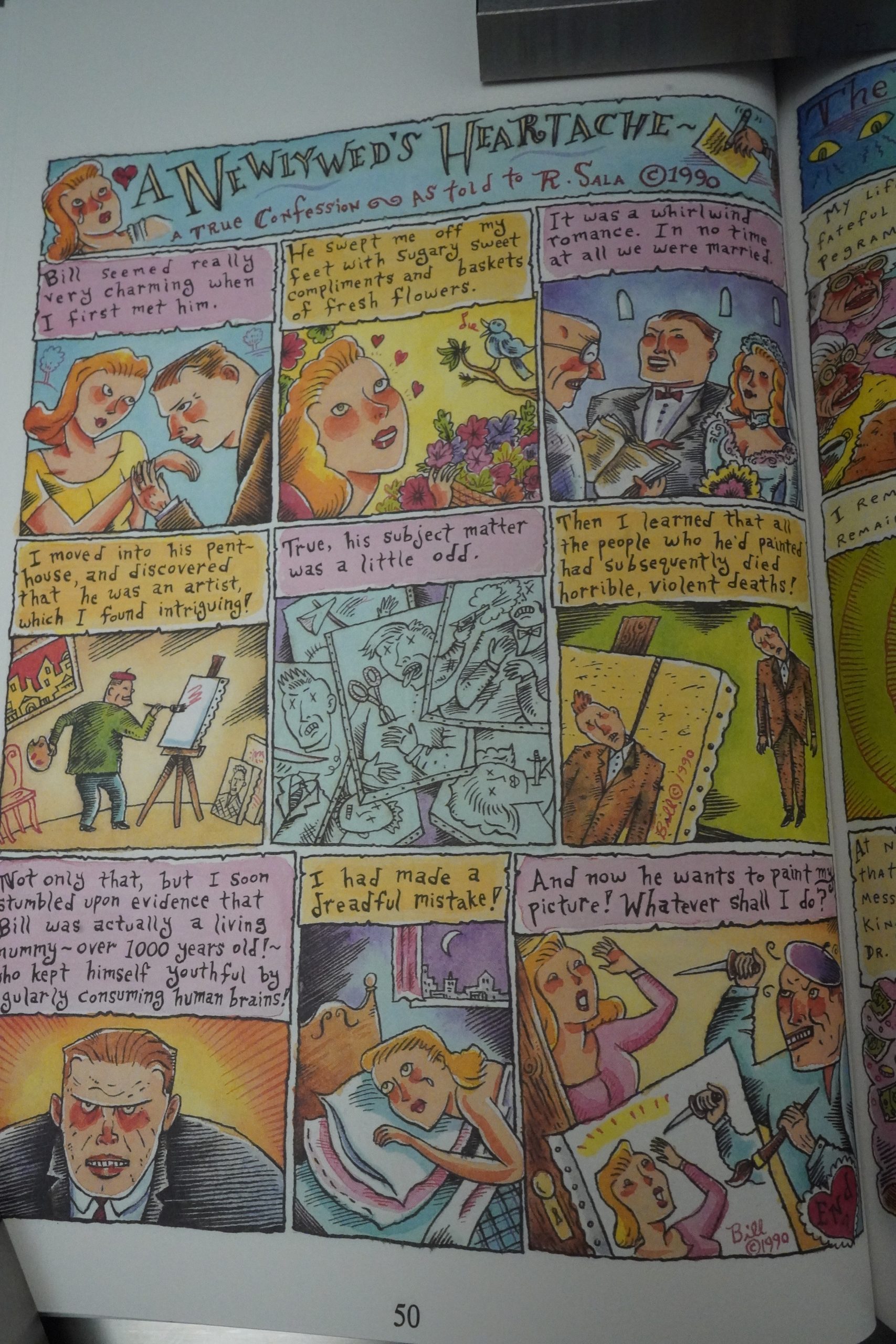

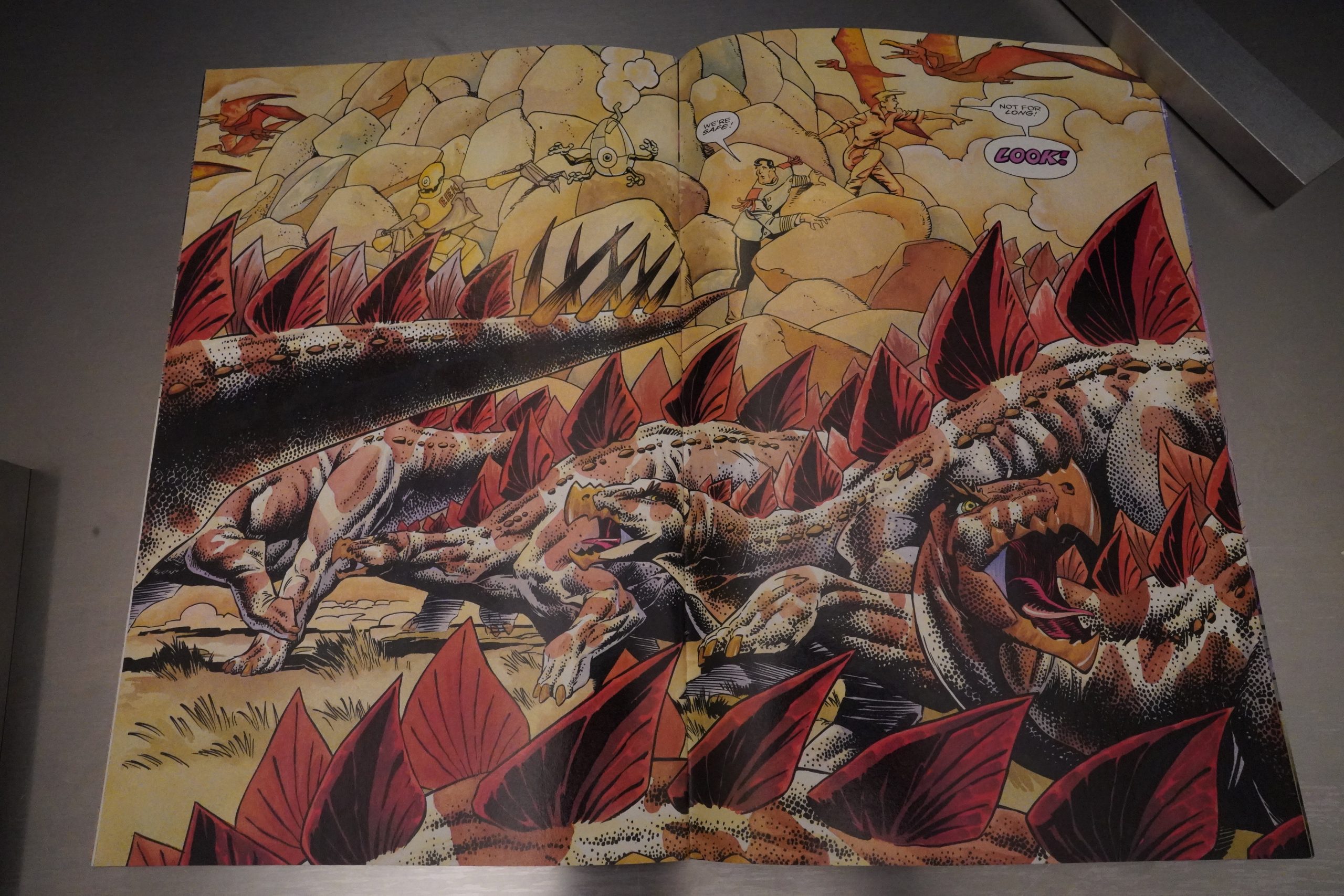

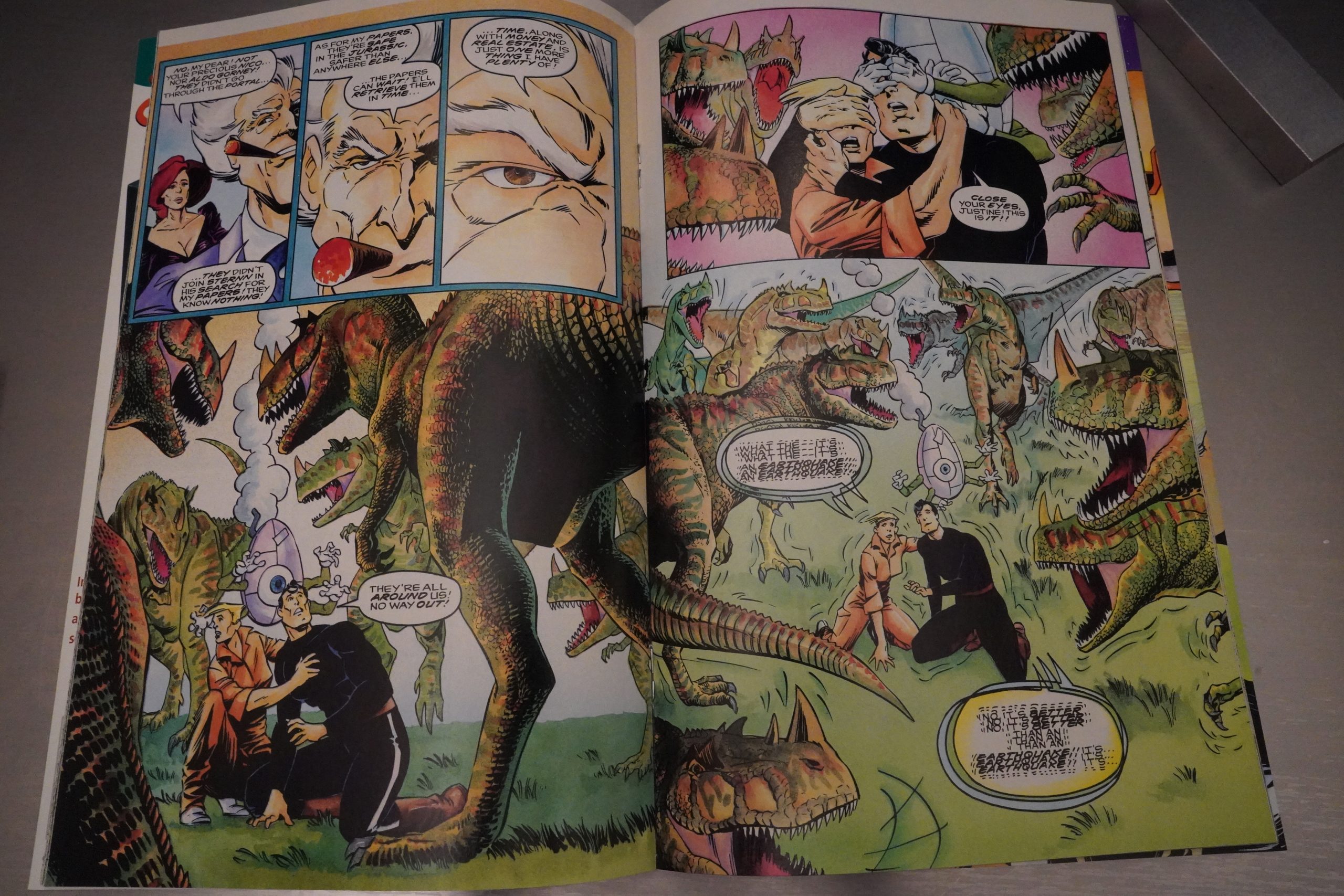

It’s also fun to see McKean just keep experimenting, and keeping things fresh.

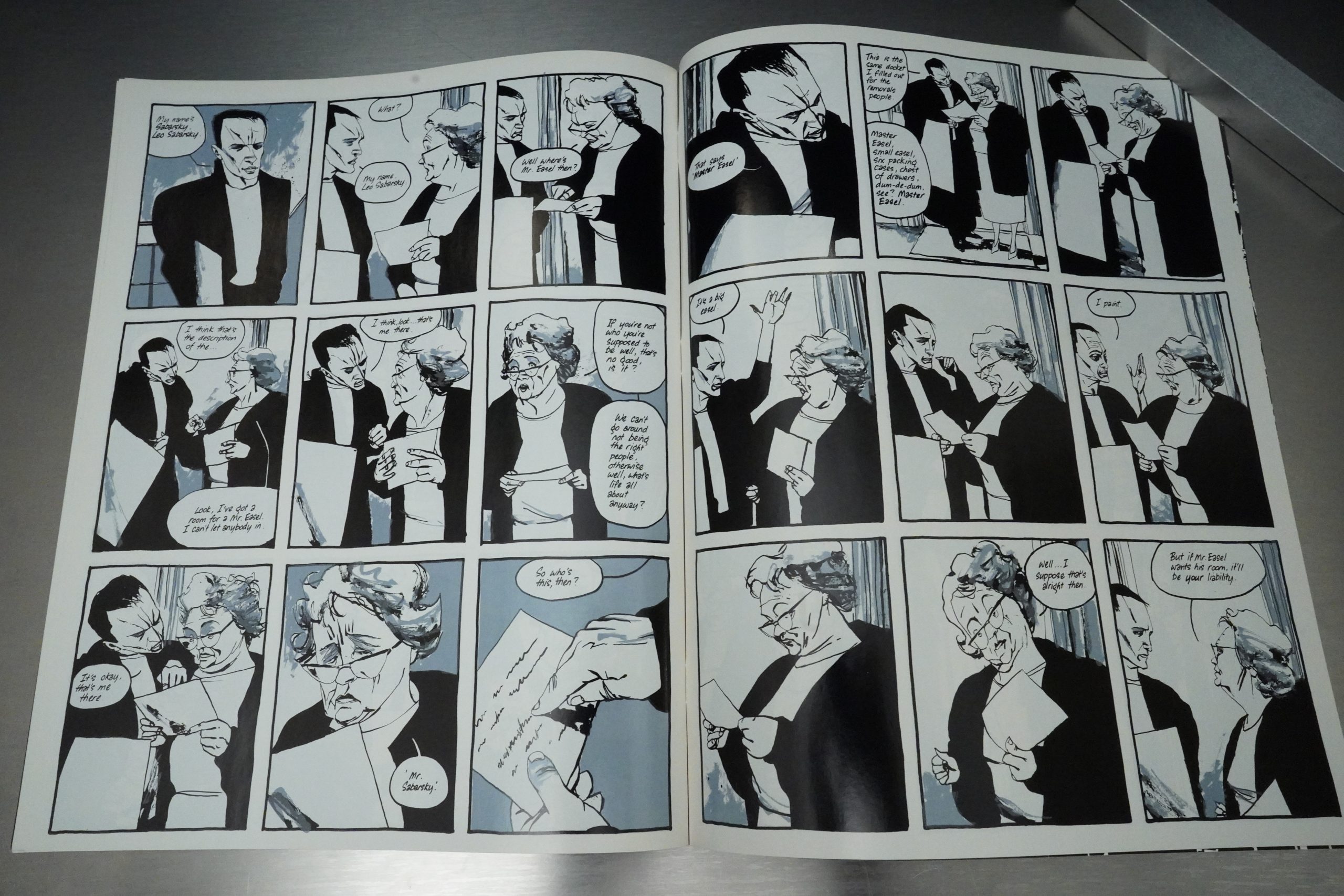

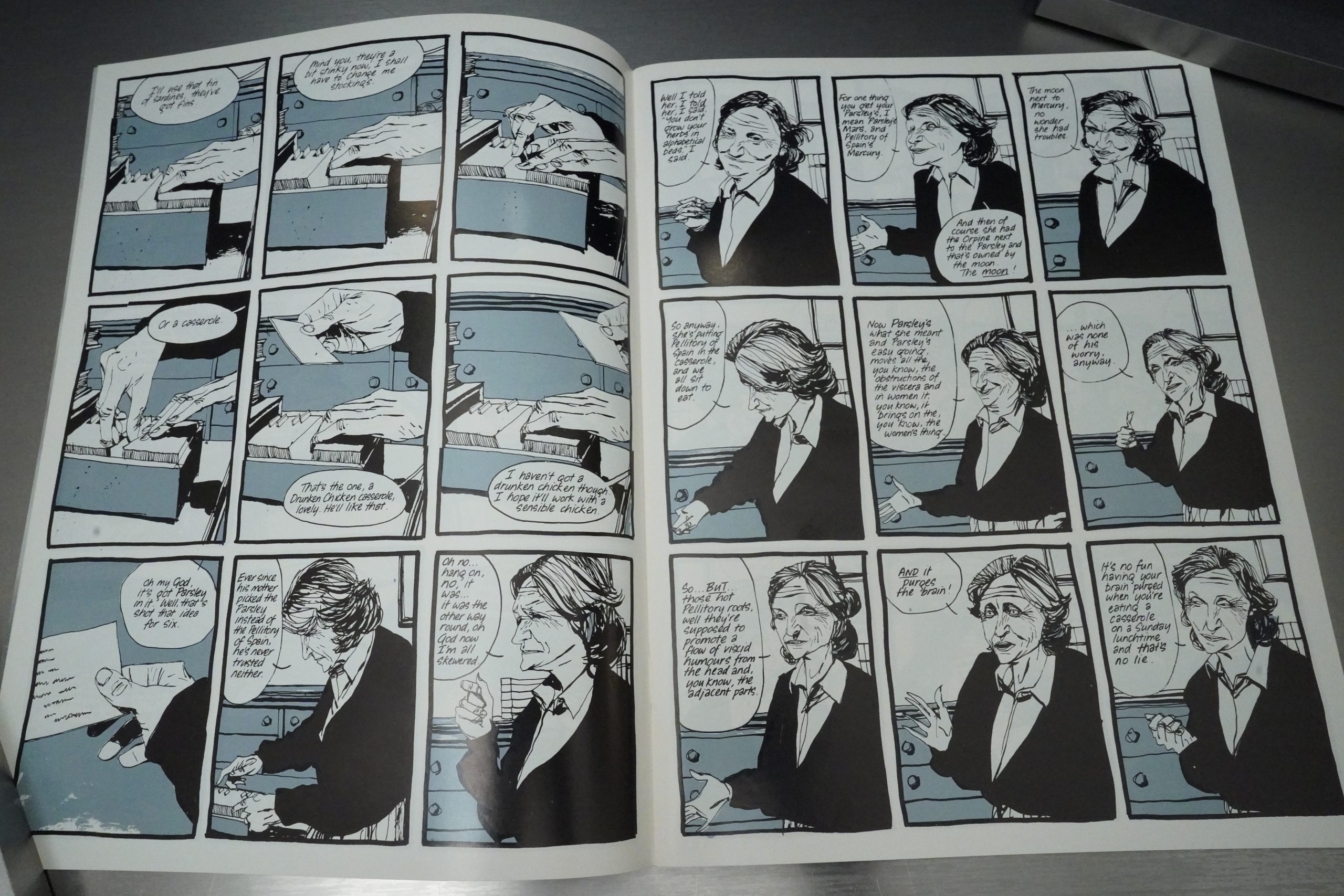

There’s a lot of bits that seems taken from real life, like being uncomfortable with having movers do stuff for you — but it’s taken one step further on, into either slapstick (above) or mysterious allegory (see many pages below). Some of it works, and some of it sticks out like “well, that’s an anecdote, but what does that have to do with anything” (above).

And while McKean has a real talent for 60s British social realist humour, I can’t really claim the same for when he’s seemingly trying for more naturalistic dialogue. It often seems stilted and unconvincing. But worse is when he tries to do prose, like in the excerpts from the genius writer — and it turns out to be pretty awful dreck. (But I don’t think it’s meant to be. It’s meant to be all deep and stuff. I think.)

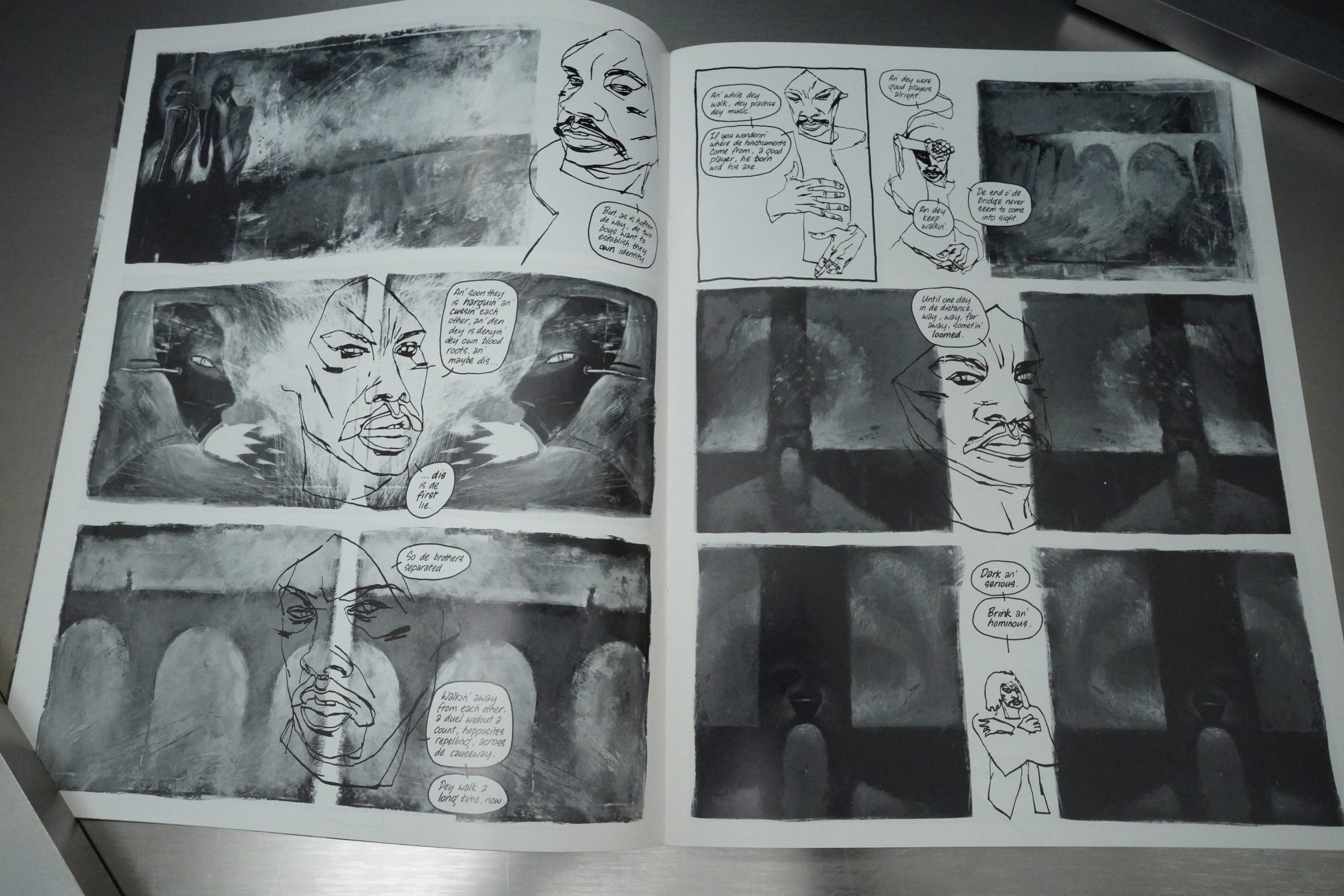

Worse is when he’s doing Caribbean dialects — “harguin'” and “lickle” etc sounds less like actual people speaking than awkward stereotype. Coupled with having this guy saying lots of Wise Stuff, it feels rather unfortunate.

McKean is on safer grounds making fun of grouchy pub owners — these bits feel genuine.

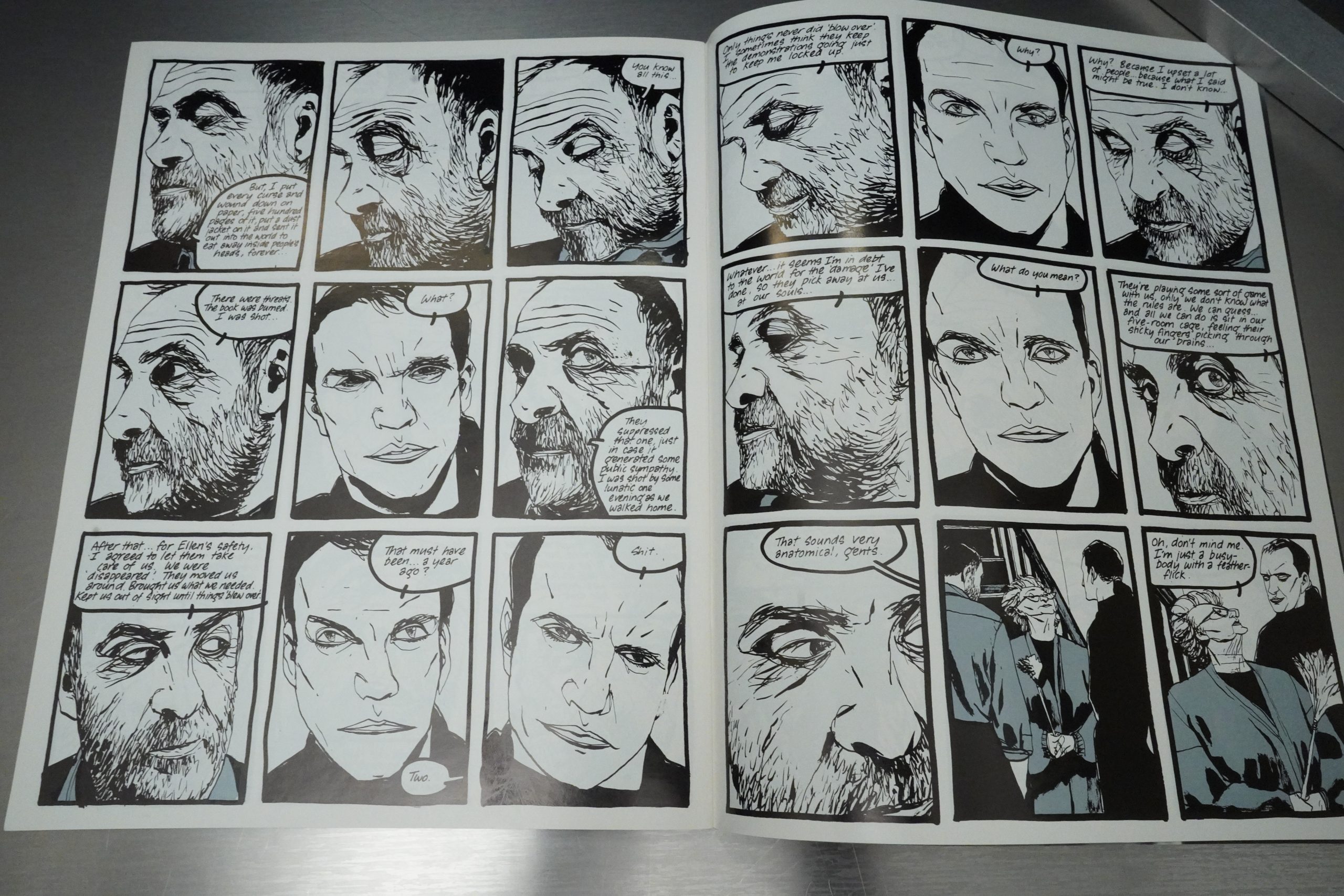

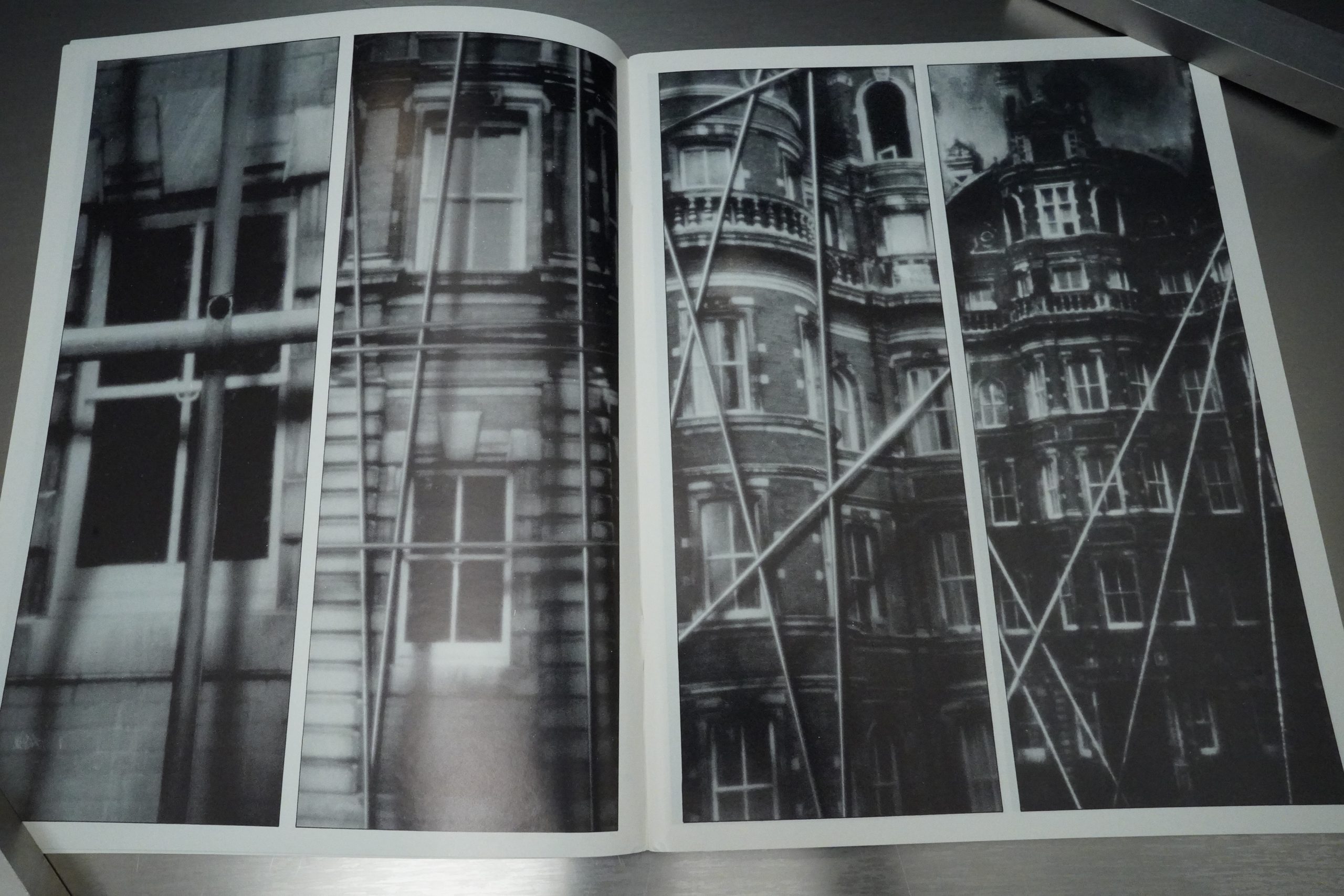

Halfway through this series, I started losing a bit faith in it. McKean introduces a bunch of mysteries, but as time passes, it becomes less and less obvious that he’s going to be able to tie much of this together. (I don’t think the scaffolding/alien creature was ever explained, but perhaps that was symbolic.)

McKean spends an entire issue on trying to write a new episode in the Talking Heads series, but that’s no Patricia Routledge, and McKean is no Alan Bennett. Instead McKean adds a “twist ending” that you’d have to be brain damaged not to see coming, and that’s annoying. Especially since there is, indeed, a few bits in here that are moving and convincing.

(I watched all of Talking Heads (and all of Bennett’s earlier stuff) a couple years ago, which is perhaps this attempt at the genre was grating for me.)

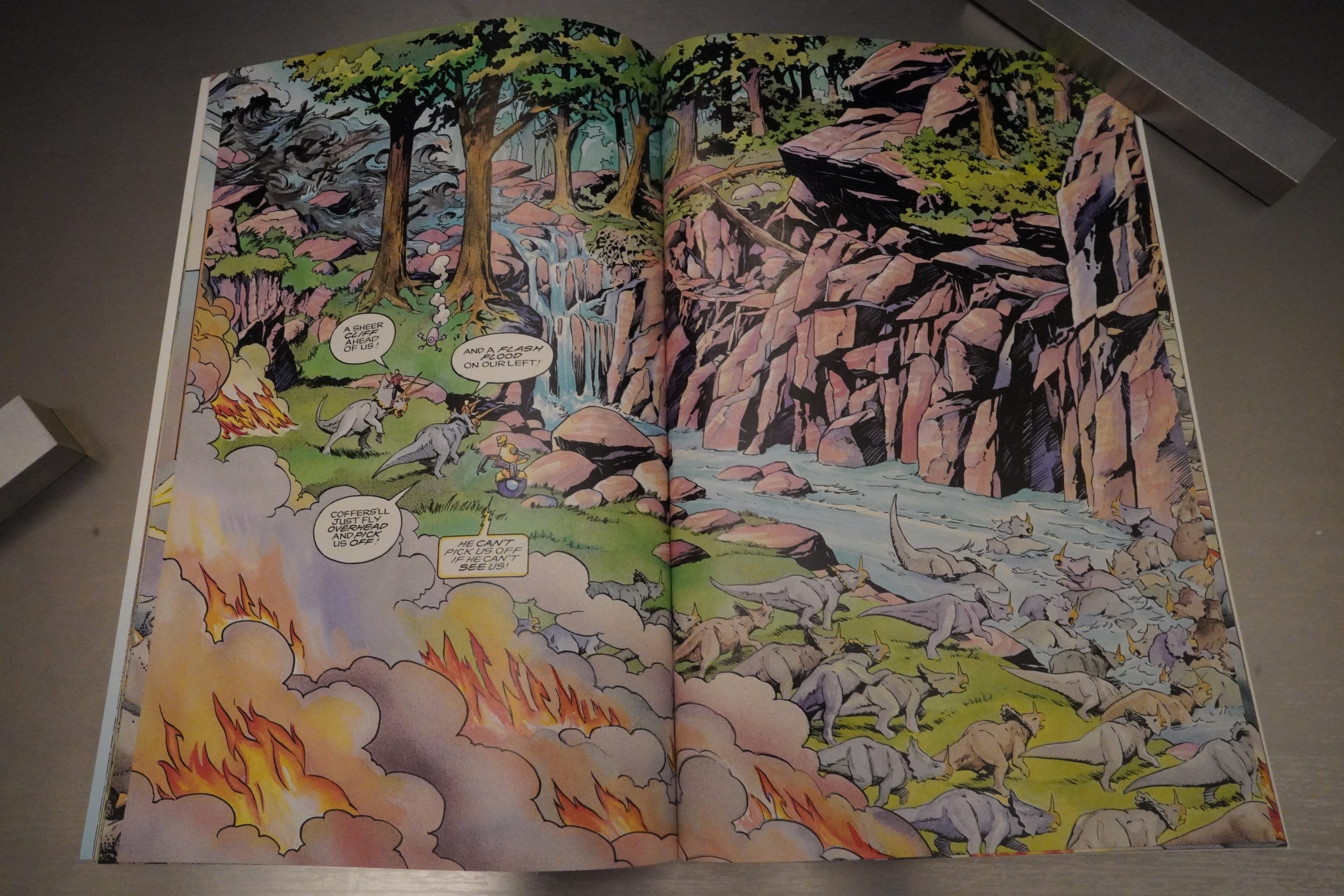

Tundra was not famous for being frugal, which is why it came as a surprise that the full colour bits here were restricted to the central sheet — so they could presumably print most of the sheets in two colour, and not add too much expense.

I feel like I’ve perhaps come off a bit too negative here — Cases is a good read, even if it’s not perfect. For instance, McKean going into this mode when the protagonist meets this woman and they start falling in love (while talking at a jazz cafe). It’s cool.

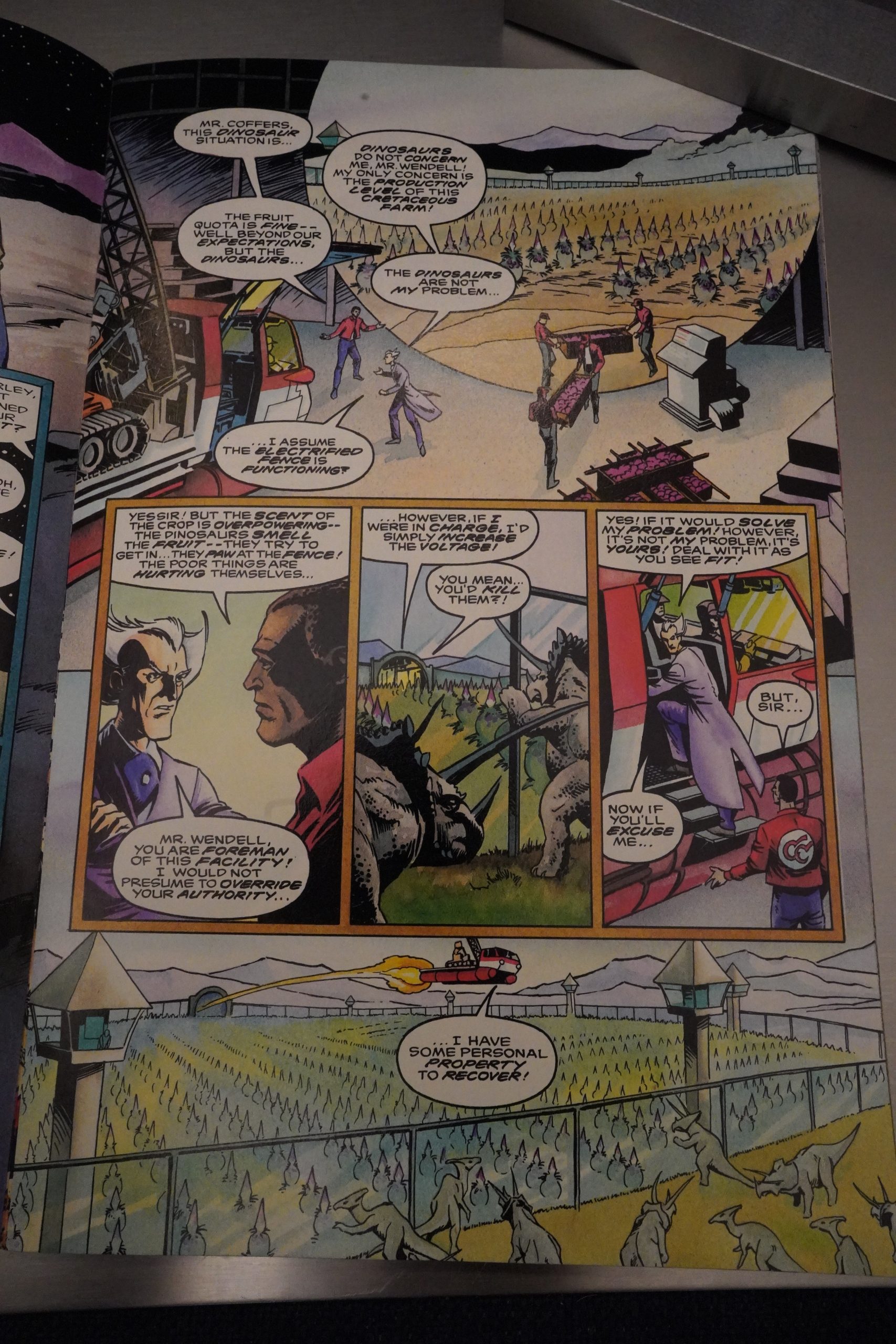

But again, McKean can’t resist piling on oddities even when he’s got too many already than he knows how to deal with.

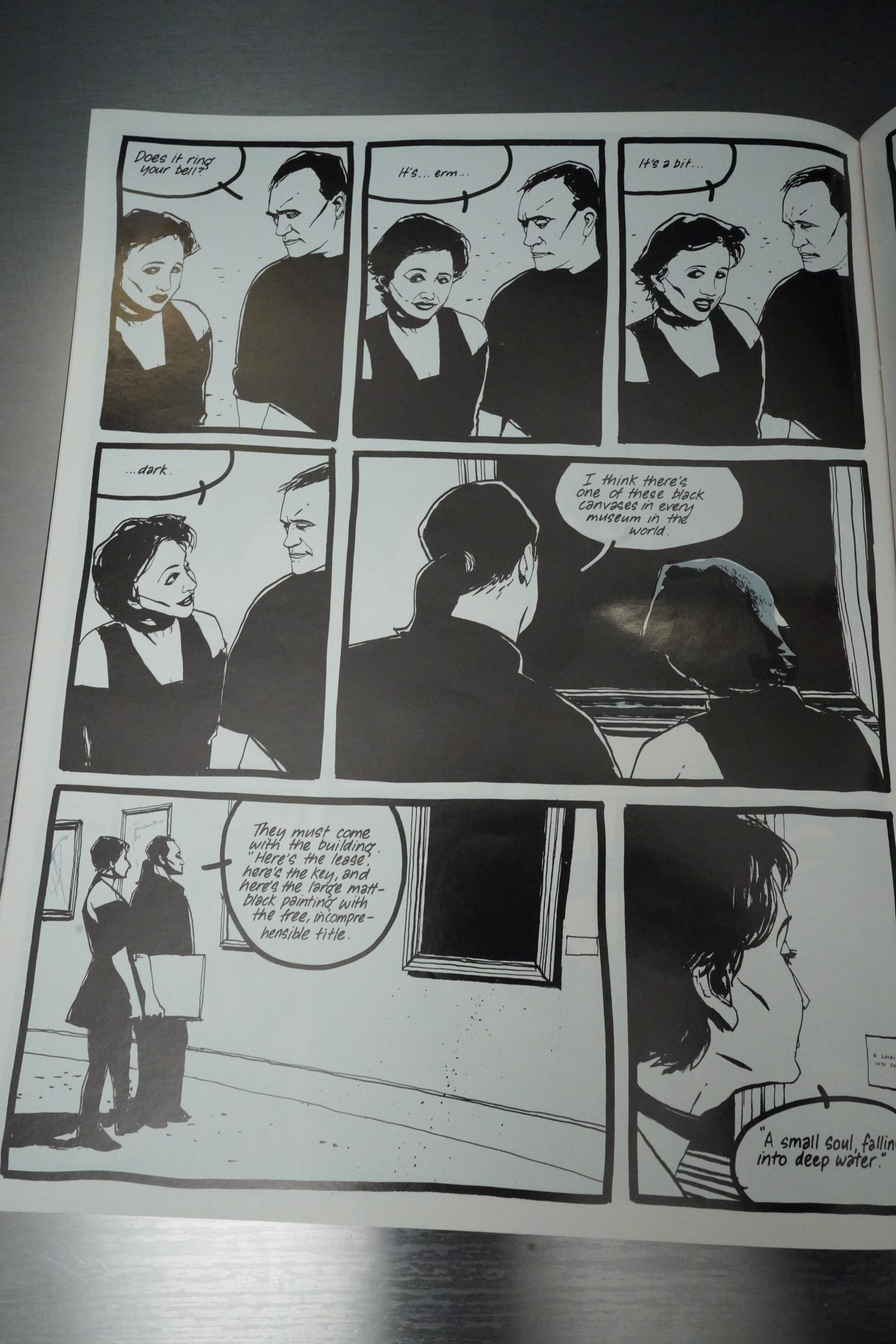

And, of course — all proper Comics Artistes (who know how to draw a hand) have to get a crack in at That Awful Modern Art These Days.

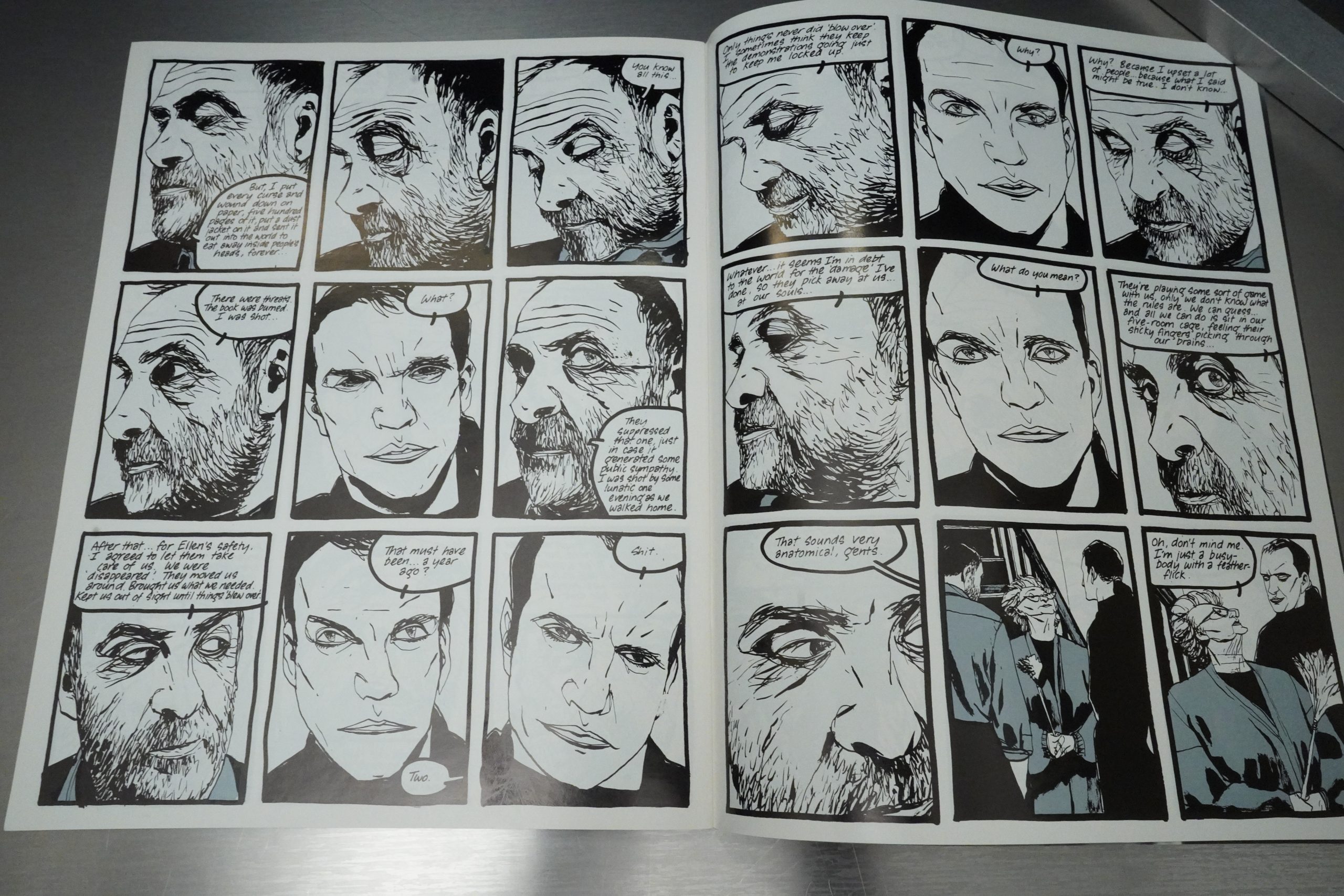

It turns out that one of the characters is a Salman Rushdie type of author, but instead of just being hunted by religious extremists, somehow he’s also being persecuted by the government? It’s just weird, and the resolution to this bit is that The Protagonist (oh, did I mention that he’s an artist?) offers to let him live in his girlfriend’s apartment instead. Case Solved.

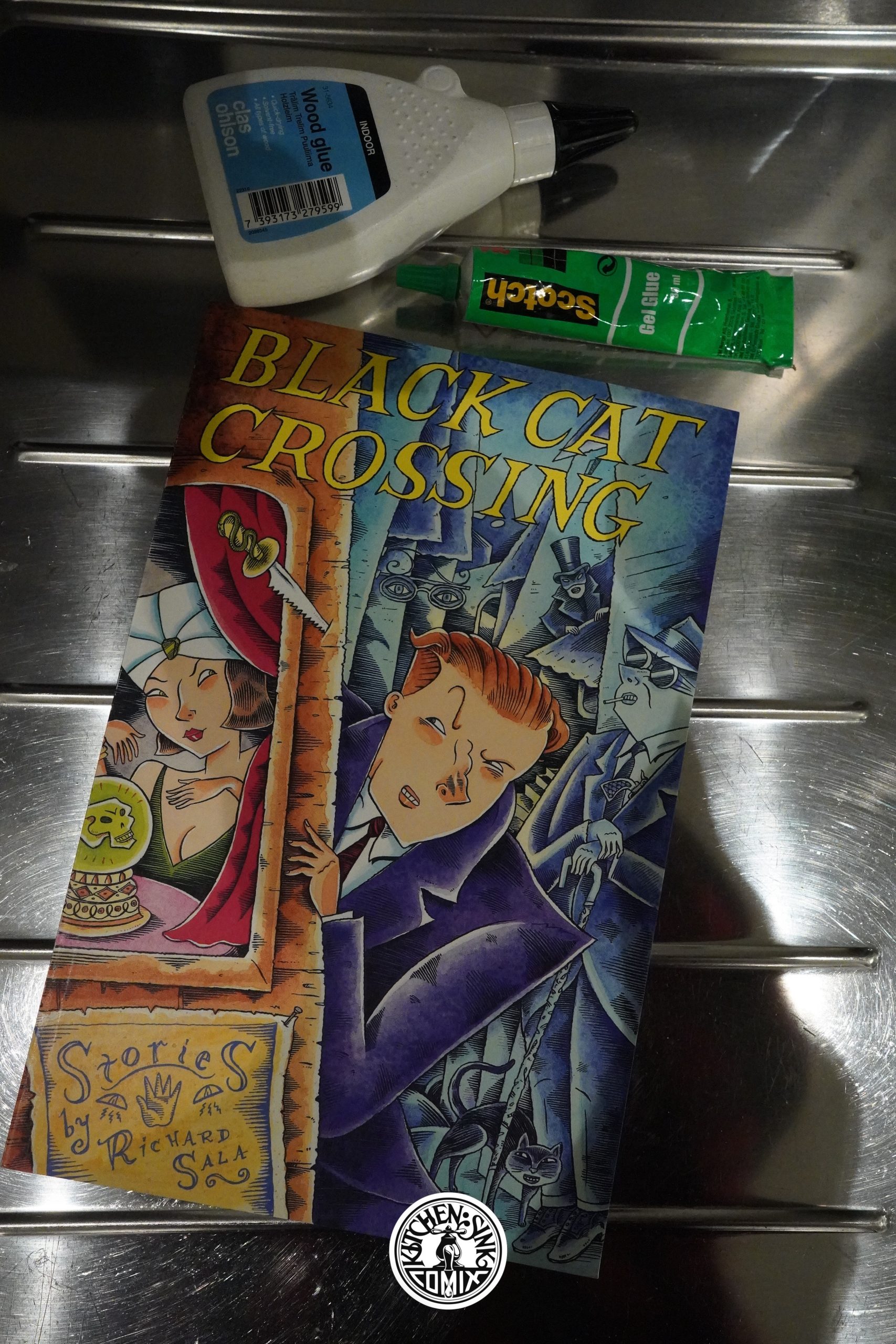

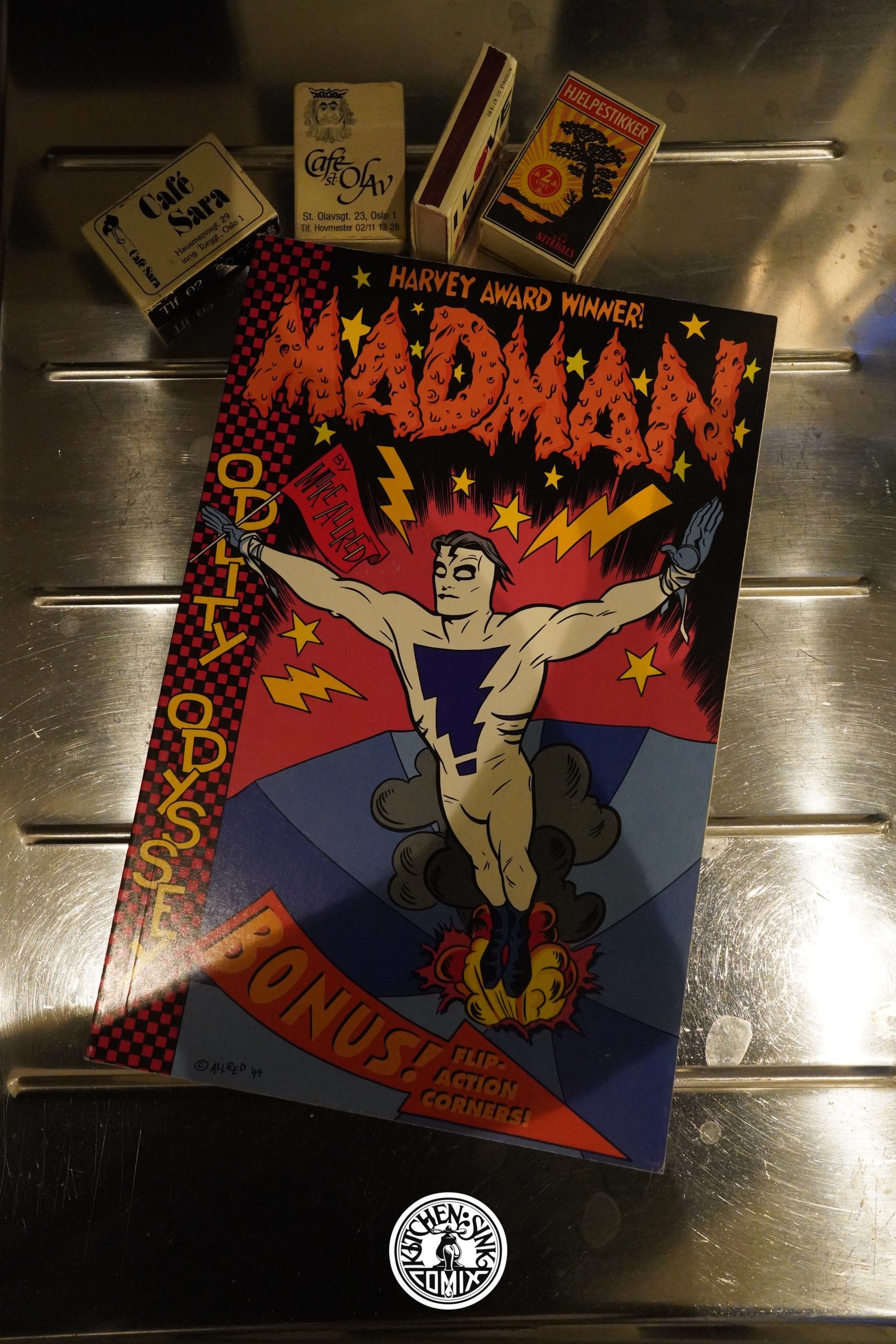

Three years pass between the eight and the ninth issues. By 1996, Kitchen Sink was in deep doo-doo, and had been sold at least once, so I guess we should be grateful that they even published the final two issues. But I wonder what happened in those three years — did McKean have to find a paying gig because the Eastman checks dried up?

And the final two issues seem a lot less work intensive than the previous ones.

McKean still seems to be experimenting, but more with a focus on not actually having to work that much.

And his drawing style (when he actually draws) seems to have changed enormously, too.

Does he stick the ending? Well… he resolves a couple of things nicely (like the cat/Bill/the Talking Heads woman turns out to be connected), but as expected, most things are skipped over. Perhaps that’s planned (to not make the ending too pat, with every thread resolved), but…

So is it a good book? Yes. It’s interesting. It’s got great art, and it’s got several really funny bits. And it’s got some mysteries that were hinted at efficiently, but not really resolved very well.

Eastman is interviewed in The Comics Journal #202, page 85:

GROTH: Here’s something that again I can’t quitefathom

this happen or be to happen. In the

minutes Of a May 21, 1991 meeting, you record the

following. Cages ispresentlysellingat $3.50. It has been

determined that Tundra loses five cents an every copy

Cages that it sells. Greg willspeak with Dave andlet him

knou that Tundra wants to increase the cover price to

$3.95 starting uith issue And then a little later, •It

has been brought to the attentiøn of the team, that out of

eight books that •uere printed in 1990, only three Of them

couldpssibly make money, and that only fall the copies

were sold. It ü.ws discovered that in certain cases, Tundra’s

actually losing money on eath book we sell.

[…]

GROTH: Well, there are some projects that you actually

spent more moneypromoting than What they grossed

EASTMAN: Yeah, we were desperate, as in “we’re here,

we’re here, we’re here!”

GROT-H: A really blatant example is thatyou

EASTMAN: Mm-hm.

GROTH: And according toyour ownfigures, whith I think

are conservative, you have to sell copies to

break even. But you only printed 13, 0m.

EASTMAN: Because thaés what we had orders for —

GROTY: 6500.

EASTMAN: Right.

GROTH: Soyou couldn’tpossibly bøve broken even on that.

EASTMAN: NO. In our evaluations, we tried to estimate

what we thought the industry standard for this kind of

more mainstream book might be, how many we’d have

to print, and how many we’d have to break even. We

felt that the book would easily go beyond 20,000

copies and it didn’t.

Marc Weidenbaum writes in The Comics Journal #142, page 58:

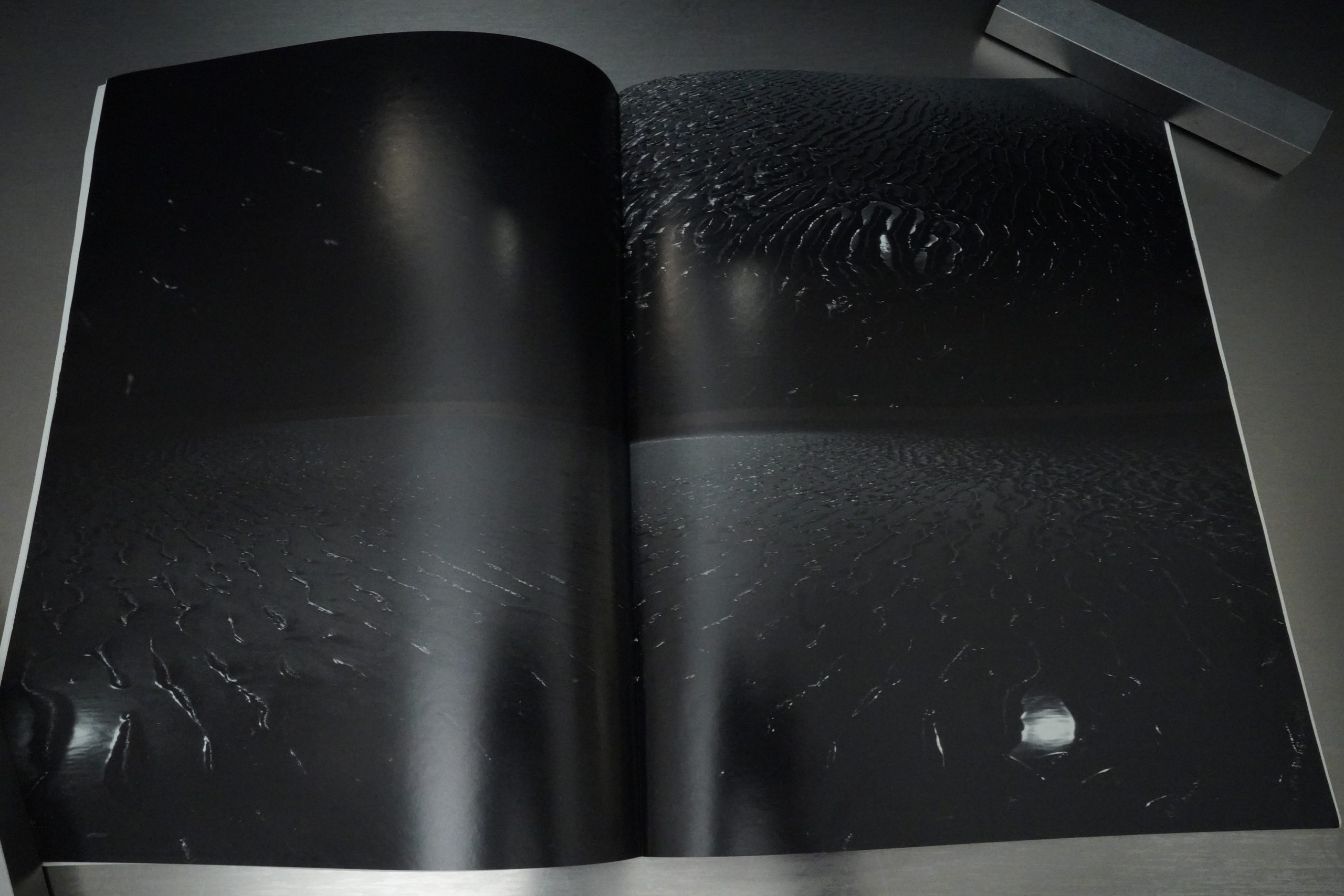

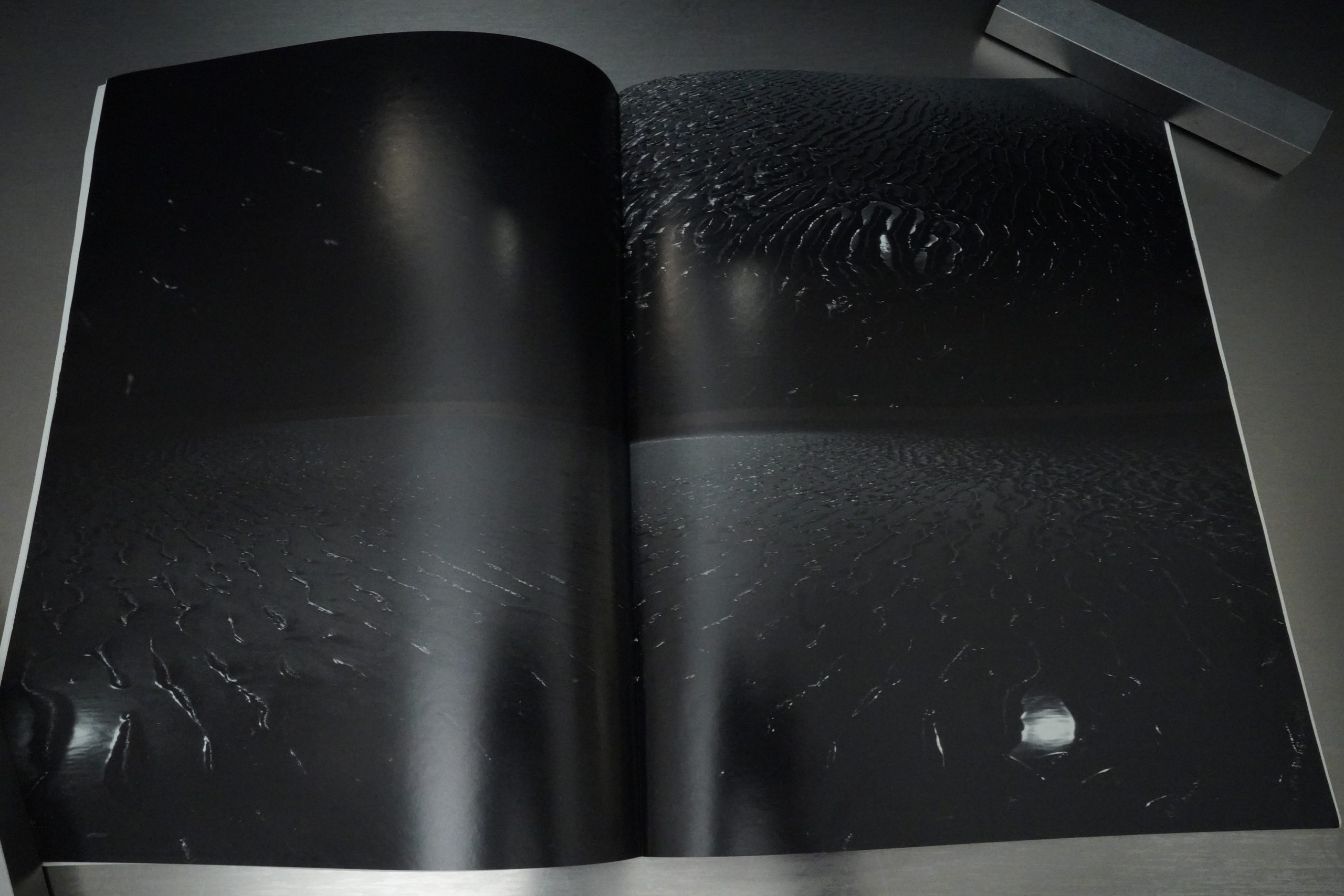

Unlike Arkham Asylum, whose title page ex-

hits more creative tension than its entire

storyline, Cages’ remarkable initial issue (nine

to follow) has no title page. The series opens

with a black page. Not a stylized, four-color

black page decorated with sharp, elegant type,

but a shitty black background covered with text

that looks as if it was set on a home computer.

McKean may have sublimated the urge to

splurge graphically, but for his first effort as

writer/illustrator, he has certainly opted for big

topics: the origin of the universe, God, stuff like

that. He paints a highly memorable, insular

portrait of reality in which a lone apartment

building appears not simply as the focal point

of the universe, but as the summation of

existence.

The series’ first issue starts with a lengthy

prologue consisting of four brief, bittersweet

creation myths, appropriately titled “Scaffold-

ing.” That’s exactly what it is: a bare-bones col-

lection of stories essential to Cages’ mythology;

a secret history of creation’s “false starts” which

is both the frame on which McKean’s fictional

universe was shaped, and the frame on which

he will fashion a modern-day story. With these

myths, McKean builds up a lexicon of shared

knowledge with his readers, so when the seem-

ingly mundane events of Cages’ first two

chapters transpire, the simple images resonate

with history and possibility.

Eventually, Cages makes a drastic shift from

a painterly prehistory mode to a present-tense,

formal comic-book mode. Except for the open-

ing and closing spreads, each page is laid out

in a three-by-three grid, in black and white, with

a second color (bluish grey) added for effect.

It’s exceptionally elegant —

imagine Bill

Sienkiewicz’s back-to-roots approach to Big

Numbers taken to an even greater extreme.

There are only two main characters of sorts

in this initial issue (a cat and a ponytailed man),

though trade ads give the impression that, as

in Big Numbers, each member of the support-

ing cast will eventually have his or her story to

tell (supposedly 10 coming-to-grip-with-the-

universe stories over the 10-issue run).

When the cat character appears, large as the

moon, atop an apartment building, it’s only been

two pages since McKean’s creation myth

wherein God took back all animals’ but man’s

power to speak, though an eon has passed. As

the cat makes its way past a flutist, and down

along the building’s scaffolding and windowsills,

peering in at unsuspecting tenants, there’s no

estimating its actual intelligence. (At times, the

frames switch to a straight black-and-white

photorealistic style, to distinguish between the

world outside the building and inside it.)

Toward the end of the first chapter, the nar-

ration turns its focus from the cat to a tall, thin,

ponytailed man in a black overcoat. He’s try-

ing to find the apartment building, and asks the

cat for directions; it’s unclear whether he’s be-

ing playful, or if he actually knows of a time

when animals could converse with people.

Most of the basic moments in Cages echo

with similar significance; pin-point stars shine

with heavenly light; pigeons double as angels;

the apartment building’s spires assume church-

like stature. Such well-honed subtlety has its

down side. Every so Often, when McKean’s

references become too literal, the humor over-

shadows the storyline and distracts from the

book’s otherwise efficacious virtures.

There’s little telling where the story will

lead, and whether McKean can expand on the

self-referential gambits which make Cages’ in-

itial issue so entertaining and provoking. Much

is left unexplained. Why, for example, does the

ponytailed man give the same name as the one

used by a painter already inhabiting the

building? Who are the “art police” terrorizing

tenants? Why do so many of the characters have

ponytails?

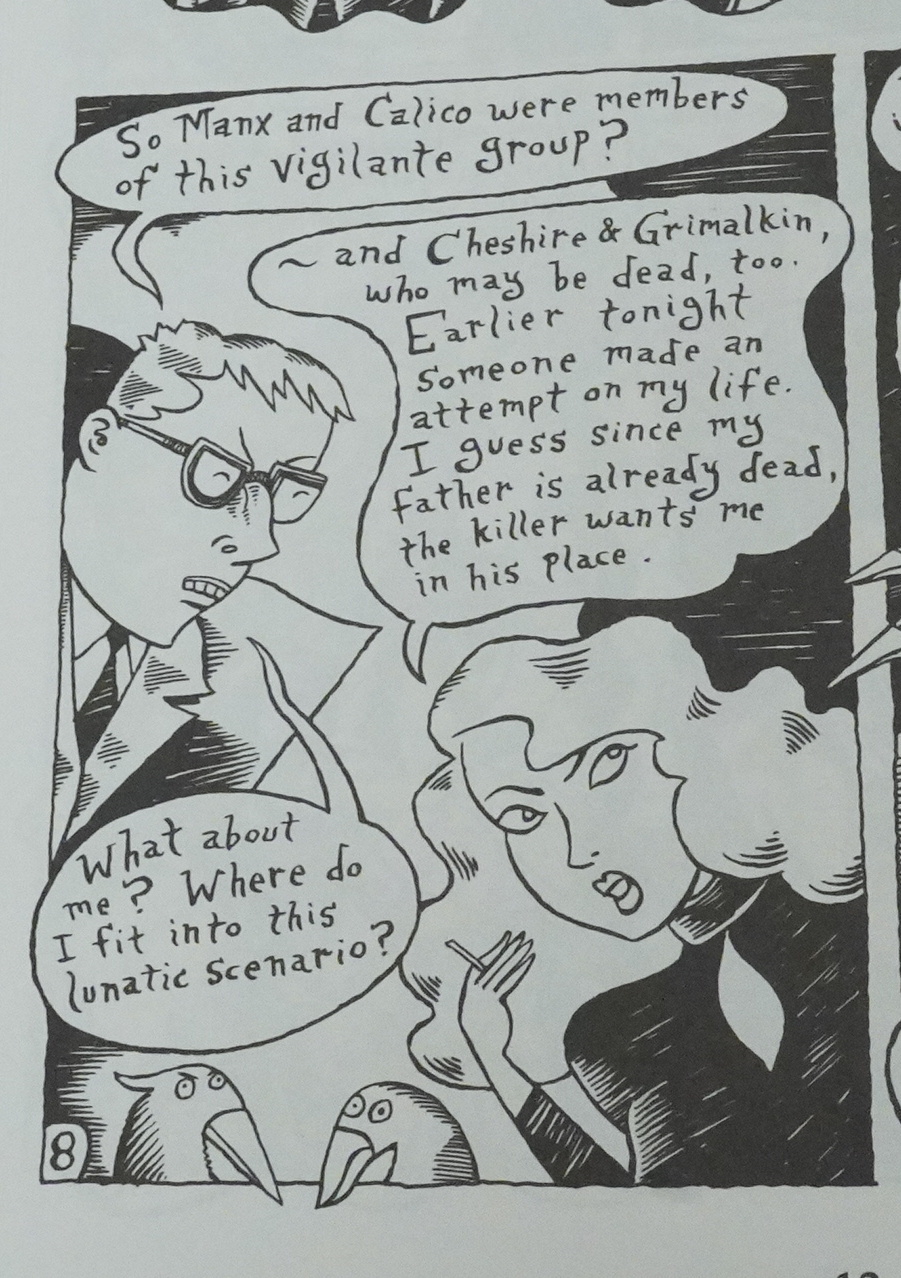

Heh heh. That guy didn’t get that there’s only one guy with a ponytail, but that the cat saw into the future through the window. Geez. Some people. It was spelled out pretty clearly…

Ng Suat Tong writes in The Comics Journal #191, page 41:

I sometimes think the transformation of corn-

ics into a mature, viable artform will take at

least another 20 years. It certainly isn’t one at

the moment. The marketplace, at present, is

populated by short form works of considerable

energy but little ambition and concerted

thought. It is a situation we fully deserve, for

we consistently fail to support the truly diffi-

cult ventures. Dave McKean has been putting

out issues of Cages since 1990. It is, by far, his

finest work in the comics to date. Yet the

echoes from Arkham Asylum and Sandman

have persistently drowned out any praises it

has garnered. All in all, a truly shameful mess.

Cages opens with II pages of text and

illustration which lay bare McKean’s thoughts

and purposes. Titled “Scaffolding,” this pro-

logue ponders the perennial questions of ori-

gins and beginnings. Our lives and those of the

characters of the book are seen as extensions of

McKean’s myths of creation. Our follies, tres-

passes, failures and creative urges are reflected

in the lives of primordial men, women and

animals.

[…]

Chapter One (“Descent”). McKean claims

that Cages has a strong cinematic element and

this is certainly true of this opening chapter

involving a cat. His agile black animal leaps

from ledge to ledge, pads around, yawns and

occasionally lies on its back to get its belly

rubbed. It also turns its head periodically toget

a scratch just in the right place (behind the

ears, that is).

The cat is an important animal in McKean’s

fourth myth. It is privy to God’s thoughts and

motivations and it is also concerned about the

welfare of man. At the beginning of the chapter.

we follow this heavenly visitor down through

the various levels of Meru House, the earthly

embodiment Of the •golden mountain that

stands in the center of the universe” (Encyclo•

pedia Britannica) in Hindu mythology. J. G.

Davies (in the Encyclopedia of Religion) states

that the temple plans of certain Hindu temples

function as mandalas — •a sacred geometrical

diagram of the essential structure of the cos-

mos.- The axis mundi is •a place sacred above

all others providing access to the supreme

being • (Lawrence E. Sullivan).

TO denote the heavenly nature of Meru

House, McKean initially restricts his use of

paints to the interiors of this temple. Having

said this, I do not mean to suggest that the rest

Of Cages is a Hindu allegory though McKean

himself may well be interested in various east-

ern religions.

[…]

Cages was never really about the characters

in the book but about McKean’s influences,

experiences, upbringing and friends. Anyreader

of Cages will realize thatl have merely scratched

the surface of this complex work. One thing is

clear to me however. The diversity of styles,

the level of ambition, the richness of thought

and the inspiring execution of Cages makes it

one of the most important works of comic art in

the last decade. O

I think he liked it. But did he major in Religious Studies or something?

McKean is interviewed in The Comics Journal #155, page 56:

DE FREITAS: I’d have rhought you ‘re the last sort of per-

son To hesitate using the word ‘ ‘profound,” really, because

you are a thinking man’s comic artist, and with Cages,

a thinking man ‘s comic writer. So let ‘s go back to Cages

as a personal vision. How did you get into that?

McKEAN: Well, as far as the mechanics of it go, it came

out of a number of writings, short pieces over the years.

As far as realizing that they were all the same thing, that

really came about through this need to create a world I

could relate to, but also to anchor it to the real world.

But my trouble is that I’ve had quite a plain background,

really…

DE FREITAS: You mean uneventful?

MCKEAN: It was pretty uneventful. I didn’t grow up in a

difficult family, or in a war zone or something, where these

tremendous formative times can impact your work for the

rest of your life, almost defining what you are — which,

incidentally, I think can be dangerous. I had a very happy

childhood in very neutral surroundings. But there was one

singular event which was catastrophic for me, and I didn’t

want to get obsessive or morbid about it, but I did keep

returning to it, and that was my dad dying when I was

fourteen. Just at the time when you need to start talking

about things. And ever since then, I’ve felt very aware of

death being around. And it’s not a morbid thing at all —

it’s actually quite motivating.

DE FREITAS: But Cages isn ‘r about death?

MCKEAN: Well, it is in as much as this holistic, full circle

world view is central to Cages. So in its way, it’s trying

to come to terms with that. I don’t want to write auto-

biography.

DE FREITAS: Right. So it’s not autobiographical in a

literal sense.

MCKEAN: No, the emotions are autobiographical. And my

own questions as to whether I could ever make anything

that was important went into the artist’s story, so I tried

to crystallize the hope and despair of doing anything

creative into one man making one painting.

DE FREITAS: The artist is in some ways The central char-

acrer, but you ‘ve created some quite memorable secon-

dary characters —7 the old lady on her own , for example.

I found that, and I mean in a nice way, pathetic — one’s

heart went out To her in a way, and felt you were making

comments on life, and it not dramatic or demonstrative,

but God knows how many people live like that. I heard

on the radio the Other day, they think that by the year 2000,

Of households in Britain will be lonely households.

And I Thought you dealt with that very sympathetically

Theie are observational skills, surely.

MCKEAN: I suppose so. but it’s only in retrospect when

I get people’s reaction to it. I remember when I showed

that issue to you and you read it the first time, you thought

I was the parrot.

DE FREITAS: Right.

McKEAN: And only then I realized, of course, those ob-

servations come from my mum living on her own and she’s

not a lonely person at all. So again, it’s not biographical,

but something of the emotional observation is true.

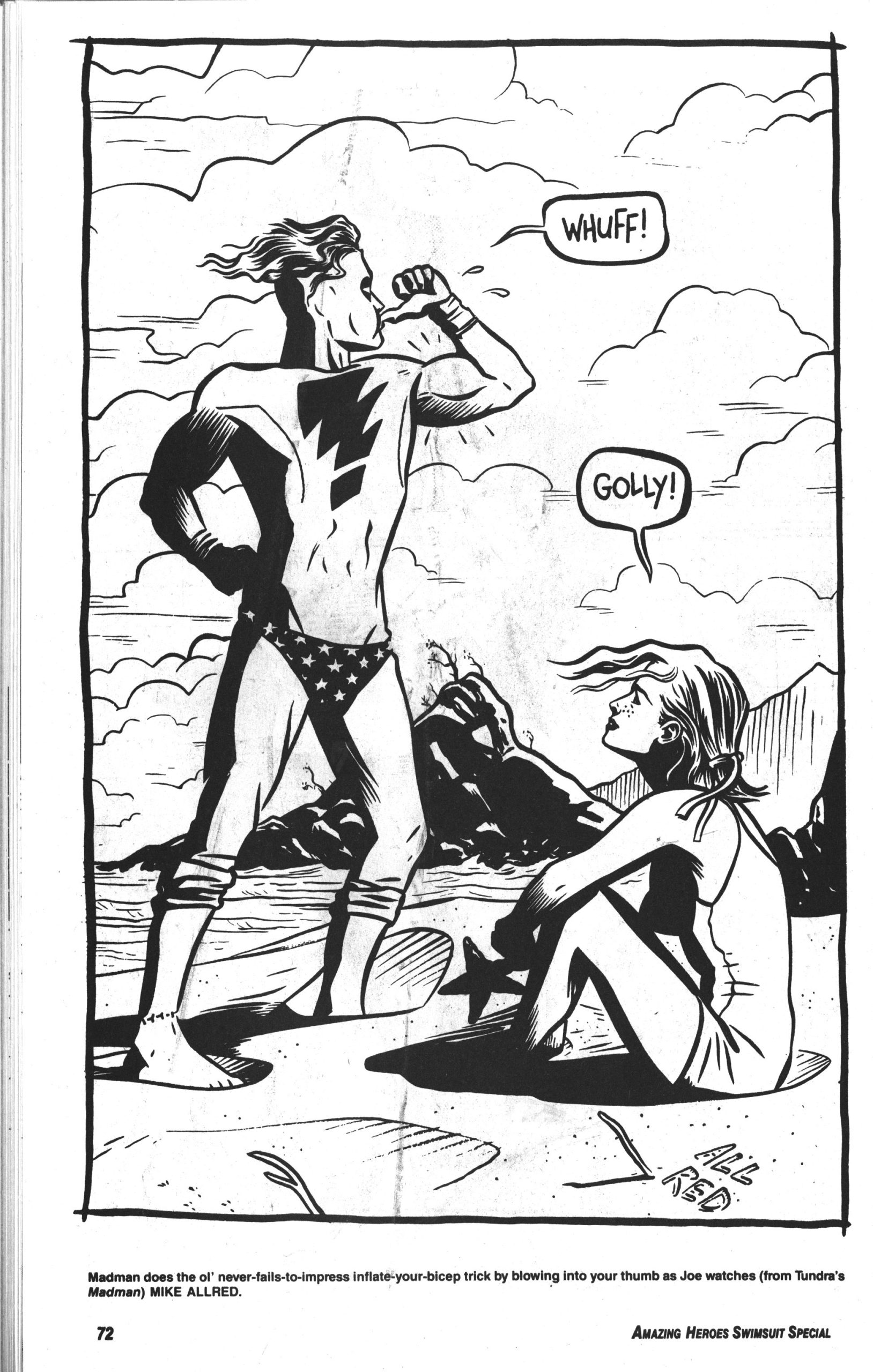

Amazing Heroes #194, page 36:

Eastman began talking with people early last

year about the possibility of opening a publishing

house, and before long, word of mouth opened the

floodgate of submissions.

“All of a sudden, I had projects coming out of

the walls,” Eastman says.

McKean was the first to approach Eastman.

“Kevin asked him, ‘What have you always

wanted to do?’ ” Baisden said, and McKean came

back with Cages.

Described as “10 issues, 10 stories pondering

the price of life and fish,” Cages is McKean’s look

at his own creative nature. And not only is it his

first published comics writing, but artistically its

soft illustration is a visual departure from the lavish

paintings to which McKean’s Black Orchid and

Arkham Asylum fans are accustomed.

“Cages is Dave discovering himself,” Baisden

says, and likewise readers are discovering a new

side of McKean.

The Comics Journal #194, page 7:

MWAH!

FRAN HWANG

It’s obvious, in his review of Gages, that Ng Suat

Tong did his re*arch. TOO bad his review misses the

first, trust basic question of criticism: Is it any good?

Of course it is — this is Dave McKean we’re

talking about, after all— but to coat a review in

a patina Of exhaustive references ignores some

of Cages’ vital strengths and glaring weaknesses.

Cages works best when its scope is intimate;

McKean is a master at capturing the subtleties Of

the everyday, as shown in the strained relation-

ship between Jonathan and Ellen Rush, or in the

flirtation between Leo and Karen. I found itnearly

criminal that Tong mostly ignores McKean’s de-

pictions of the growing relationship between Leo

and Karen, such as the night when they meet,

talking and flirting over coffee as Angel playsjazz

in the background, their bodies flowing and shift-

ing surreally. Or their night of lovemaking, where

McKean depicts the instant after orgasm as a

spiral Of ammonites. It’s nothing short of genius,

really — a series of ethereal, swirling forms to

express the expansive, draining of afterglow

— and one of the most stunning depictions of sex

in all of the visual arts.

And Tong does McKean a disservice by un-

derplaying his skill at characterization. The world

Of Cages is filled with some of the most likeable,

sincere oddballs since Northern Exposure. From

the mute gallery owner who speaks with cards to

the man wearing the solar system on his head,

McKean populates his work with a supporting

cast thaes both disarming and original.

Unfortunately, McKean loses his wit and

perception when he makes his scope broader.

His allegories and neo-fairy tales are precious

and hardly original: Within comics alone, they

areshamelessly cribbed from Sandman and Beau-

-w tiful Stories for ugly Children, and they weren’t

that great the first time around.

Cages’ greatest flaw is that iYs art about art,

apparently executed without much forethought

on the common pitfalls of this kind of story. Art

about art always runs the risk of pretension and

onanism, of becoming nothing more than an ode

to itself. Cages, unfortunately, does little to dis-

tinguish itself from the rest of this fare.

McKean wastes a lot Of paper with vague,

useless generalities about art. Angel’s story of

two musician brothers on an endless bridge

boils down to nothing more than advice to find

the happy medi urn between discipline and spon-

taneity. Uh, thanks. Nobody’s ever thought of

the concept of balance before.

Further, he makes the mistake of depicting

not just the reactions of people to art, but the art

itself. It’s all fine and well if Jonathan Rush has

written a novel that sparked riots and led to an

unusual exile. Unfortunately, McKean includes

part of the novel’s text, actually written by him-

self, and makes it painfully clear that he’s much

better at pictures than prose:

“My God, if your precious messiah fell to

earth tomorrow, the poor fucker would prob-

ably open his wrists before letting you mutilate

his heart or infect his brain or just… bugger the

living juices out of him, like you’ve buggered

your own sister „

I can’t help but wonder how this trite jer-

emiad, which reads like it was written by either

an exceptionally sensitive high school goth or

Garth Ennis, is supposed to stand out enough

from adolescent anti- Christian bitching to war-

rant such an extreme response.

Maybe I’m judging McKean’s effort harsher

than I should because I’m not so disposed to-

wards his aesthetic: I cringe at the way he teases

modern art (“l think there’s one of these black

canvases in every museum in the world”) and

then offers pop-psychology exercises (“Imagine

you’re walking through a forest”) in its place. I

truly do like Cages; the medium is made richer

by its existence. If nothing else, it’s great to see

McKean try his hand at writing, and it’s always

good to see the cover artist applying his com-

mensurate skill to the sequential demands of a

comic’s interior. Still, to act as if Cages is perfect,

and then mask that presumption in heavy

deconstruction, does both the Journal’s readers

and McKean a disservice. The Journal doesn’t

need to kiss McKean’s as; that’s what all the

Other magazines are for.

That’s the most cogent review of Cages I’ve seen, and it was on the letters page.

Comics Scene Volume #2, page 25:

“Cages came out of visual ideas,” he

“I had been drawing a lot, so

adds.

story ideas came very slow. It has

taken three years, while I’ve been

working on other peoples’ books—jot-

tings and little bits of plot ideas that I

had written down, which came to-

gether at a time when I was completely

unhappy with everything that I had

done. I was generally dissatisfied with

everything and wanted to re-create

what I was doing, which led into the

creation myth at the beginning.”

McKean explains that his more

mainstream comics work had begun to

frustrate him. “Midway through Black

Orchid, and mostly with Arkham, I

started feeling that it wasn’t quite right,

I was doing them for the fun of it, not

for any sort of personal satisfaction.

Then, I got to the stage where I realized

I hadn’t done anything for personal

satisfaction!”

Cages was the project McKean de-

cided to do for himself, “It follows the

interweaving lives ofa bunch of people

who live in the same building. There

are fantasy elements that weave

through it, but what I’m trying to set

up in the beginning is a down-to-earth,

simple story about these people.

Running alongside that are mythic folk

tales full of surreal and fantasy images,

but they don ‘t touch. They run parallel

to each other. The story with all the

mundane, everyday goings-on is in

the context of this strange world and

the fantasy images, which is largely

how I think many people go on [about

life]. People run around doing many

day-to-day mundane things: going to

work, coming back, eating, sleeping—

in the context of believing in God or

gods, these fabulous stories of

centuries-gone-by. It’s interesting that

their lives can be seen in that way.

“There are moments in my story

when the mundane and the mythic

come together,” he continues, “but I’m

generally trying to keep them apart,

because that’s mostly what happens fin

real life]. At the day’s end, people

don’t get to talk to God, and there are

no immense, miraculous, fantastical

things that happen. But, at the same

time, there are many small miracles

All the characters’ Cages can be found un-

der the same roof somewhere in the heart

of a large English city.

And so on and so on. I don’t think I’ve seen a work that was talked so much about at the time as Cages — it was a phenomenon, at least amongst people who wrote about comics.

It was no. 46 on the Comics Top 100 in The Comics Journal #210, page 65:

It took several years, two publishers

and 500 pages to complete, but it

was more than worth the waitin the

end. Cages, Dave McKean’s explo—

Sive graphic novel, is one Of those

artistic achievements that you’re

compelled to stand back from and

just marvel at.

Really, it should be a total

mess. What starts routinely enough

as a tale about a small group of

artists (a painter, a musician, a

writer) all living in one London

apartment building explodes into

a vast canvas of dreams, stories,

lies and hallucinations. As reality

shifts and is shifted time and again

McKean similarly unleashes his

prodigious artistic talents, pulling

out all the stops — linework, Oils,

photos, mixed media, full color,

duotone, you name it — in an

effort to find new ways of corn—

municating in the comics form.

Seemingly building as he goes

along McKean presents a densely

structured narrative spiked with

odd angles, baroque visual treat-

and decepti v ely

ments

unmapped extensions. But you

know what? In the end it all

holds together.

More than that, it actually

works. Sure it’s wild and often out

ofcontrol. But at the same time it’s

some of the smartest and most el-

egant cartooning of the decade.

Some oflt seems slapdash and rushed,

while other parts seem coldly calcu-

lated and deliberate. And that’s the

way it should be. This is, after all, a

book about creation and creation

occuß in all sorts of unexpected

ways from the spontaneous to the

controlled.

The success Of Cages rests in

the fact that McKean is one of the

rare cartoonists with such a wide

variety of visual tricks that he could

pull offsuch a display. I can think of

few cartoonists who could have

pulled Offa book as big and bold and

brash as this one. But I’m certainly

glad that I can think ofone.

A new edition was published in 2016:

Cages is largely breathtaking in its use of the form. McKean is equally at home working within a rigid page layout as he is veering into a much more abstract system. His use of the occasional phonetic spelling, largely to differentiate characters’ accents, was a little harder to pull off.

People still like it:

Cages may be the most solid proof to-date that comics can be a literary art form. I would argue that Cages can comfortably go on the same shelf as Ulysses, The Metamorphosis, and 100 Years of Solitude.

See?

The genius of McKean’s artwork in Cages is that the faces of his characters, despite being featured over and over again sometimes hardly changing from panel to panel compositionally, are never illustrated the same way twice.

And so on:

McKean’s gift for characterization and nuance has allowed him to establish a truly living, breathing world in Cages thus far. The Meru House is a home for some very strange and compelling characters, all bursting with mystery and life.

So I guess that Cages really turned out to be the most enduring thing Tundra published.

This is the one hundred and fifty-eighth post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.