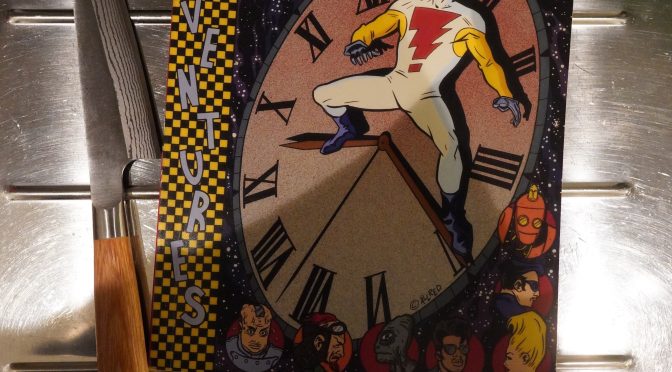

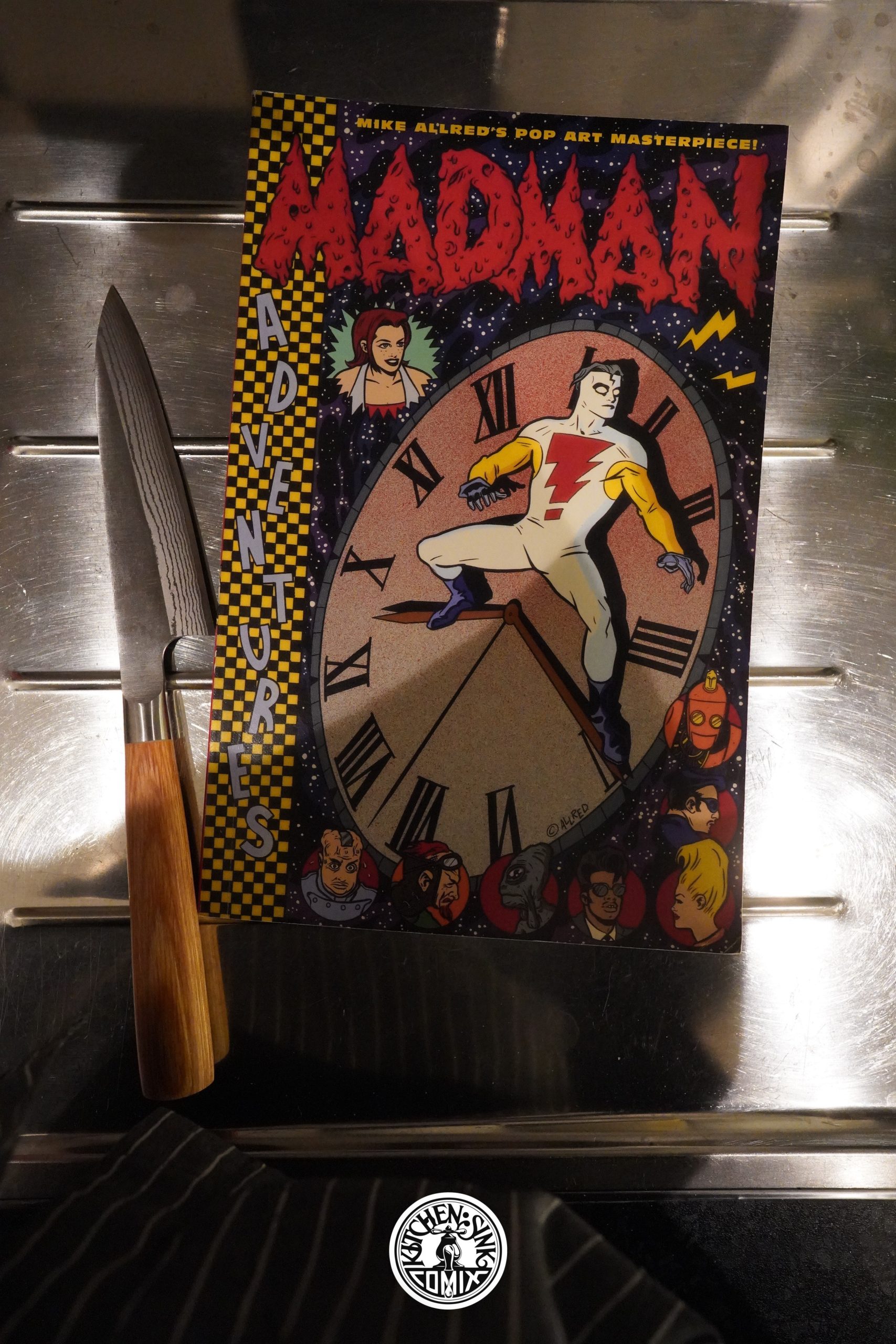

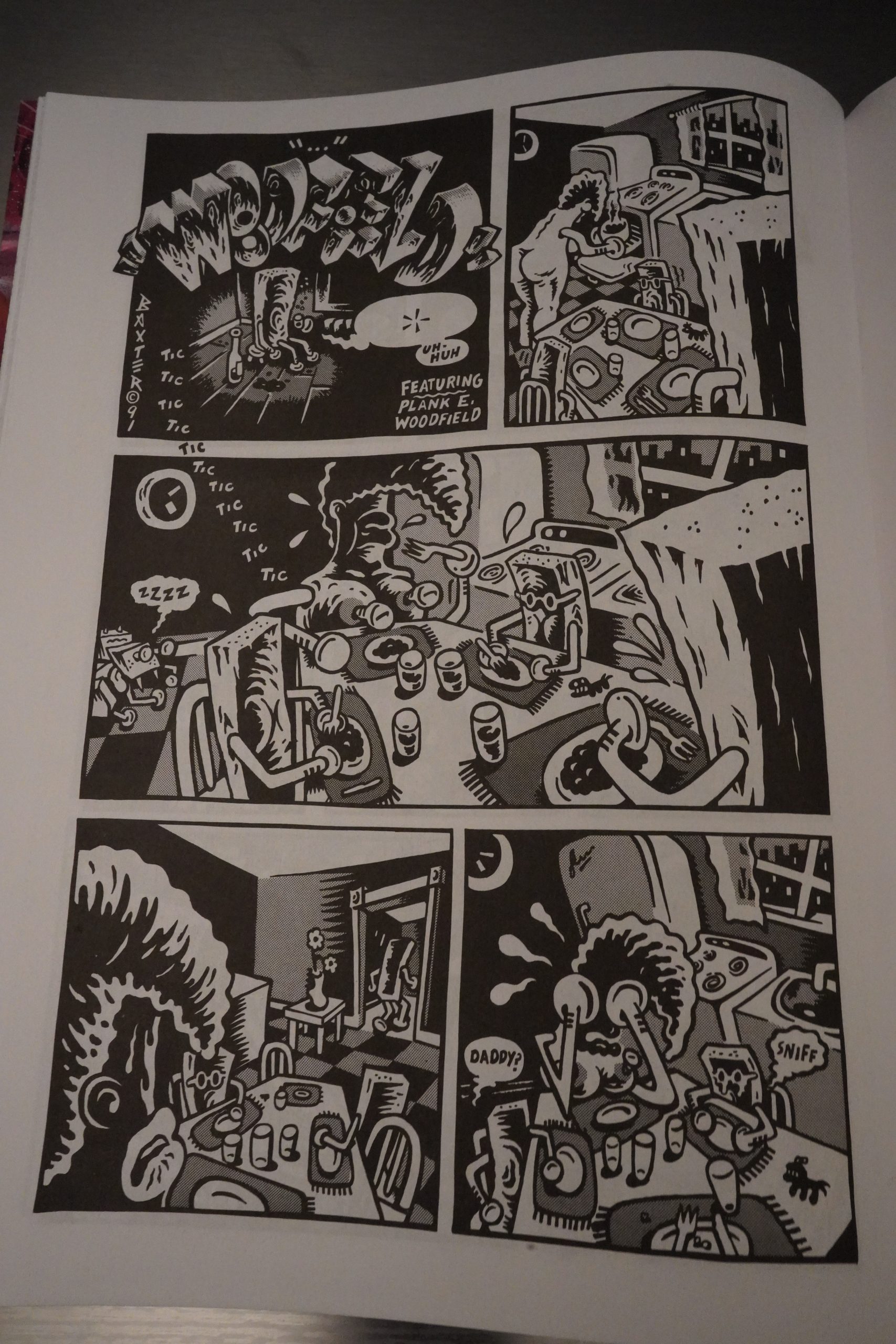

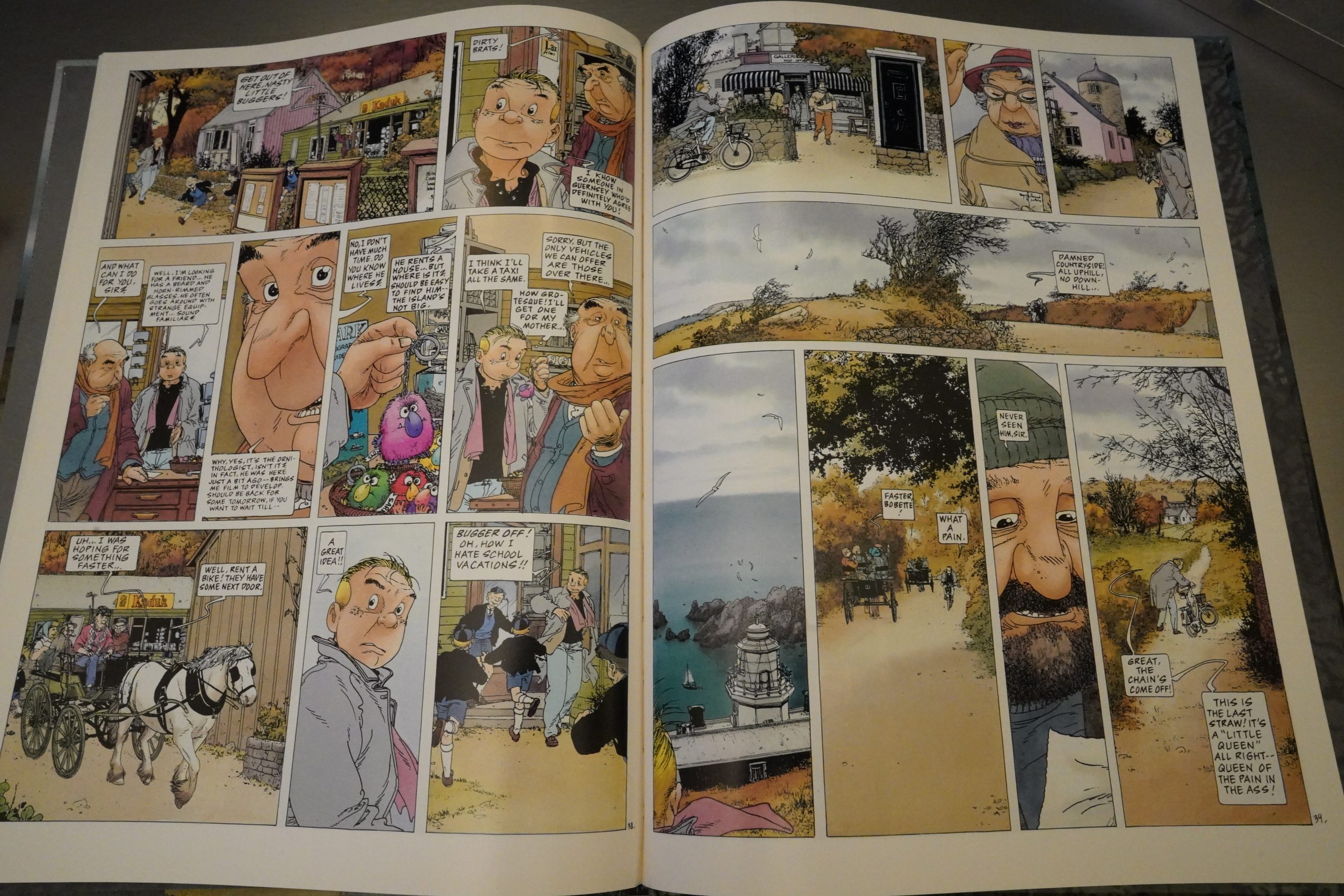

Madman Adventures (1993) by Mike Allred and Laura Allred

I was a huge Allred fan back in the Graphique Musique/Graphic Music days, but I lost track of him soon after, and never read his Madman stuff, for some reason or other.

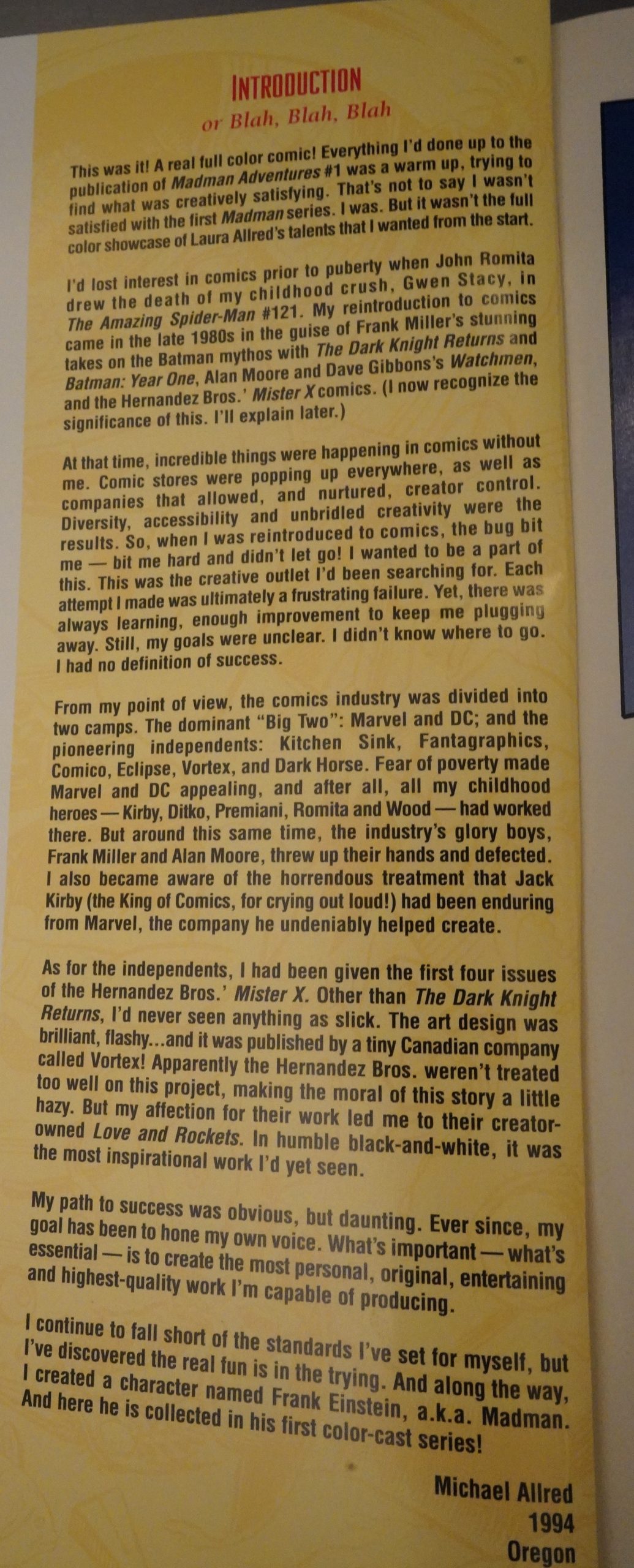

He explains in the introduction that for the first time, his comics look like he wants to.

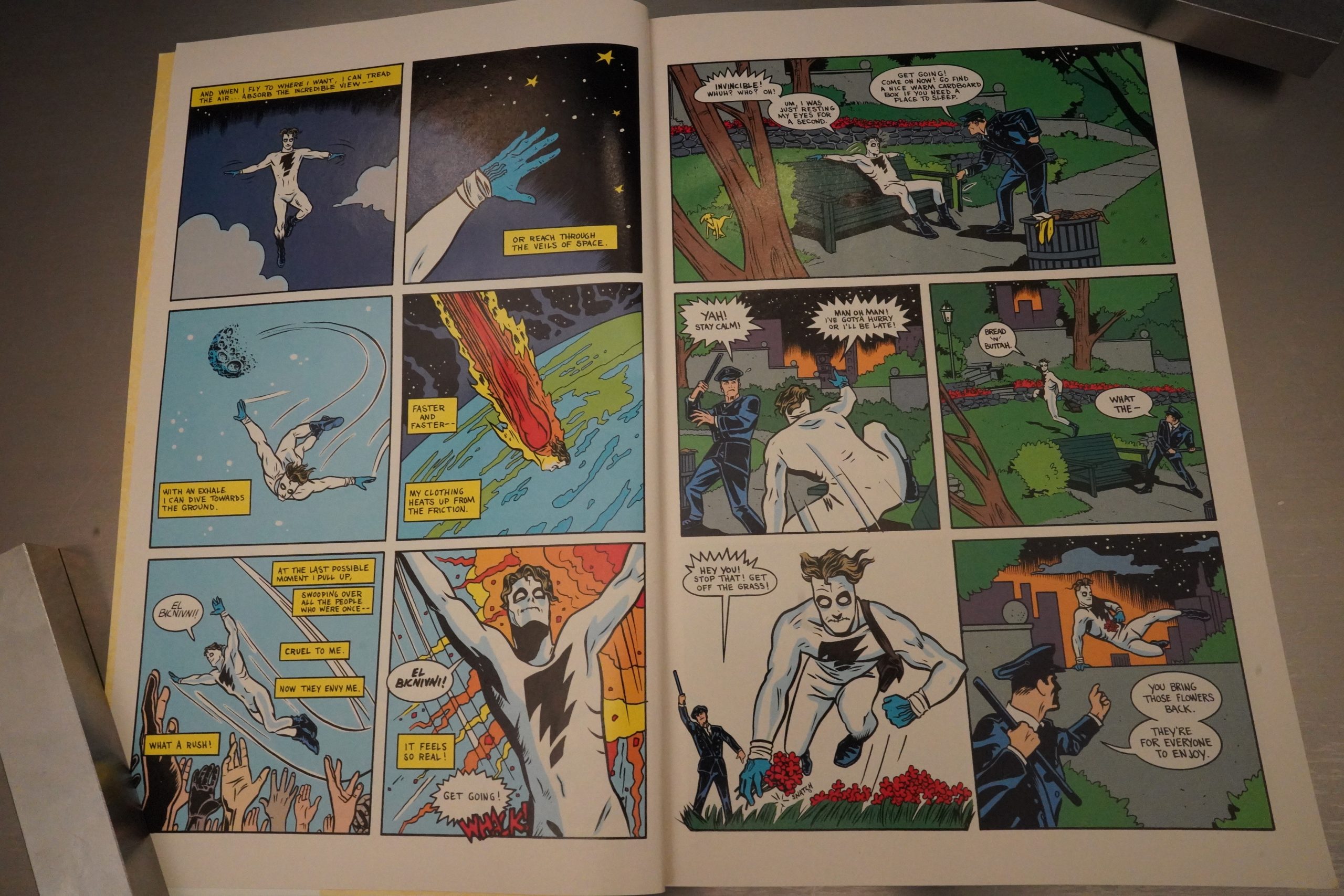

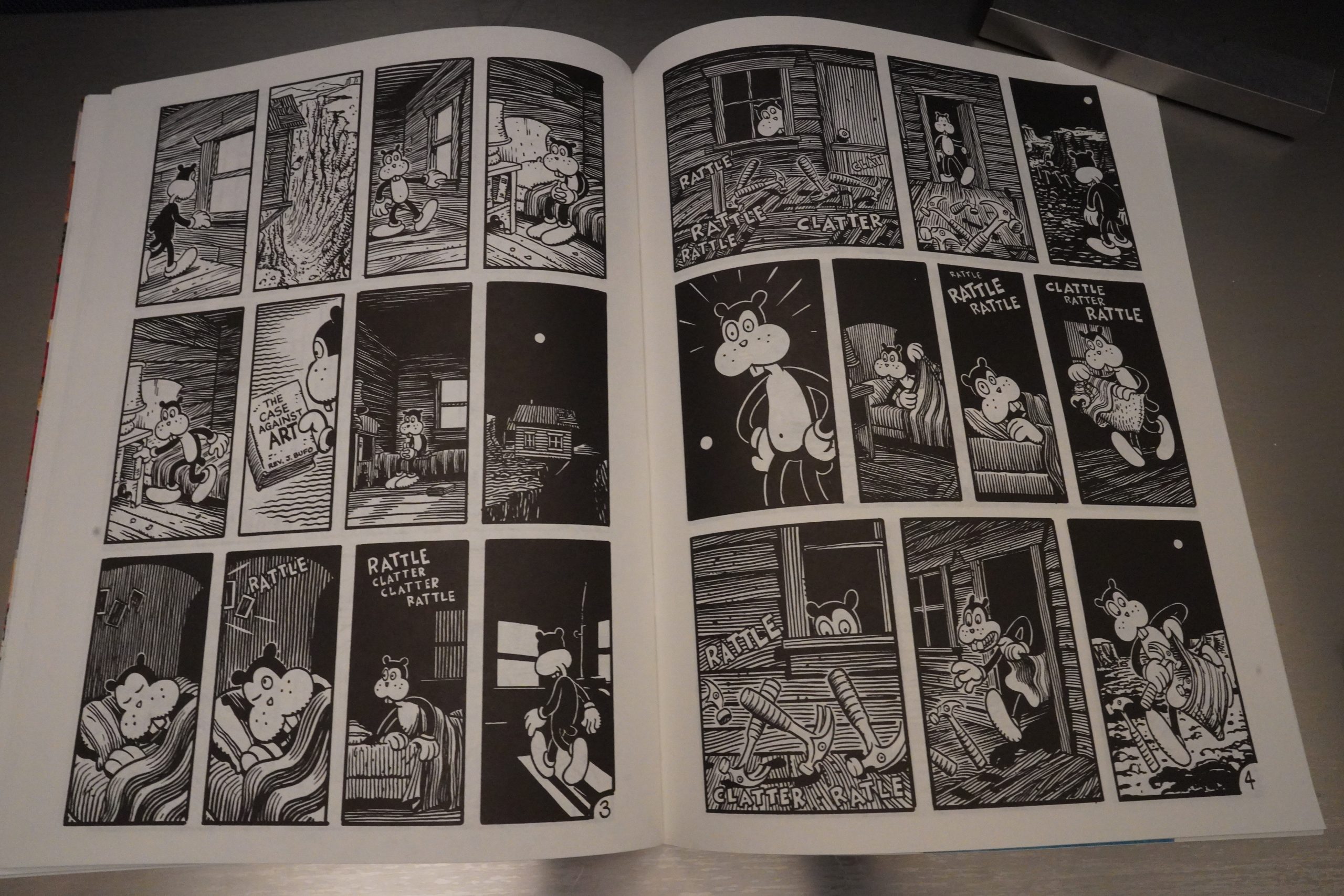

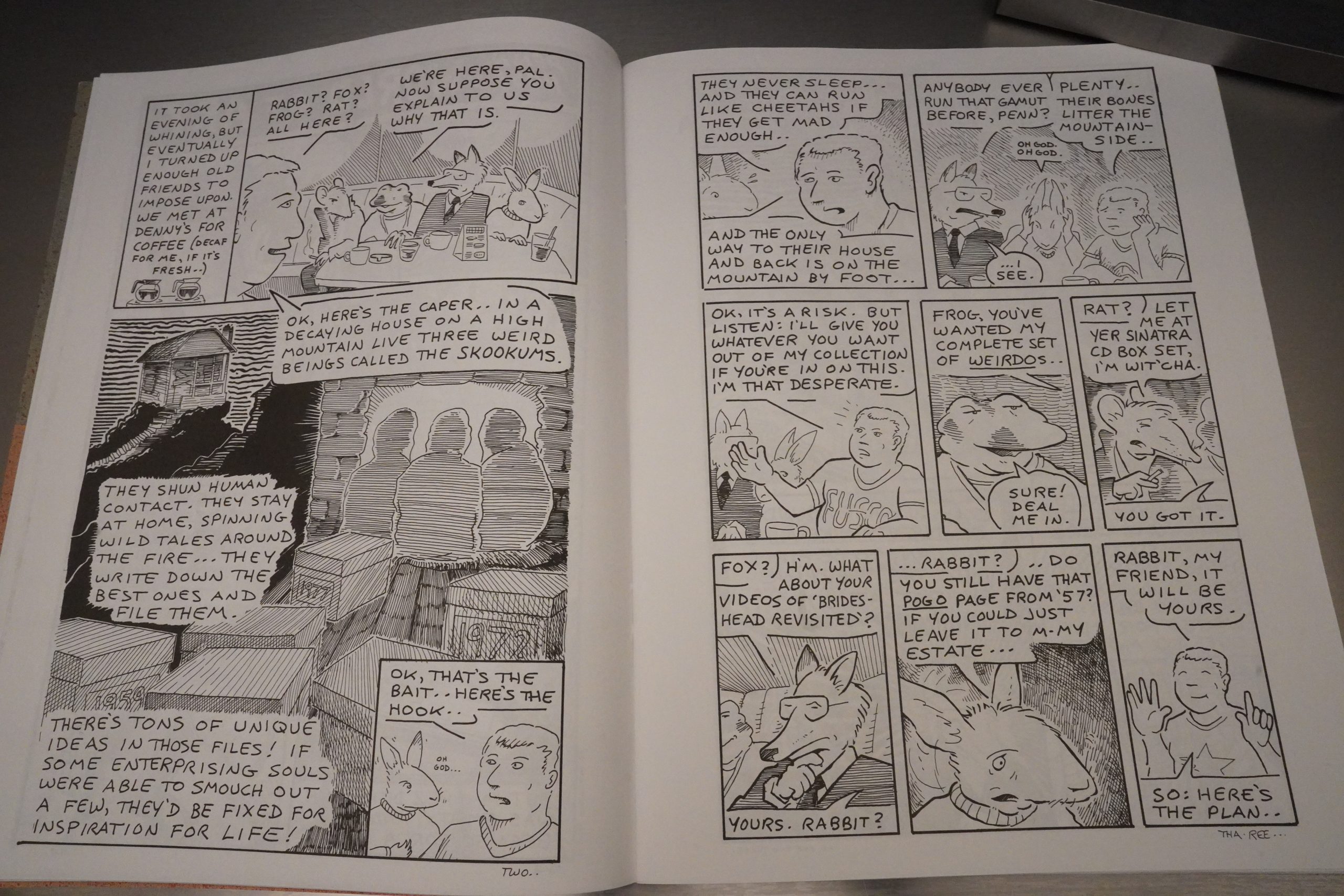

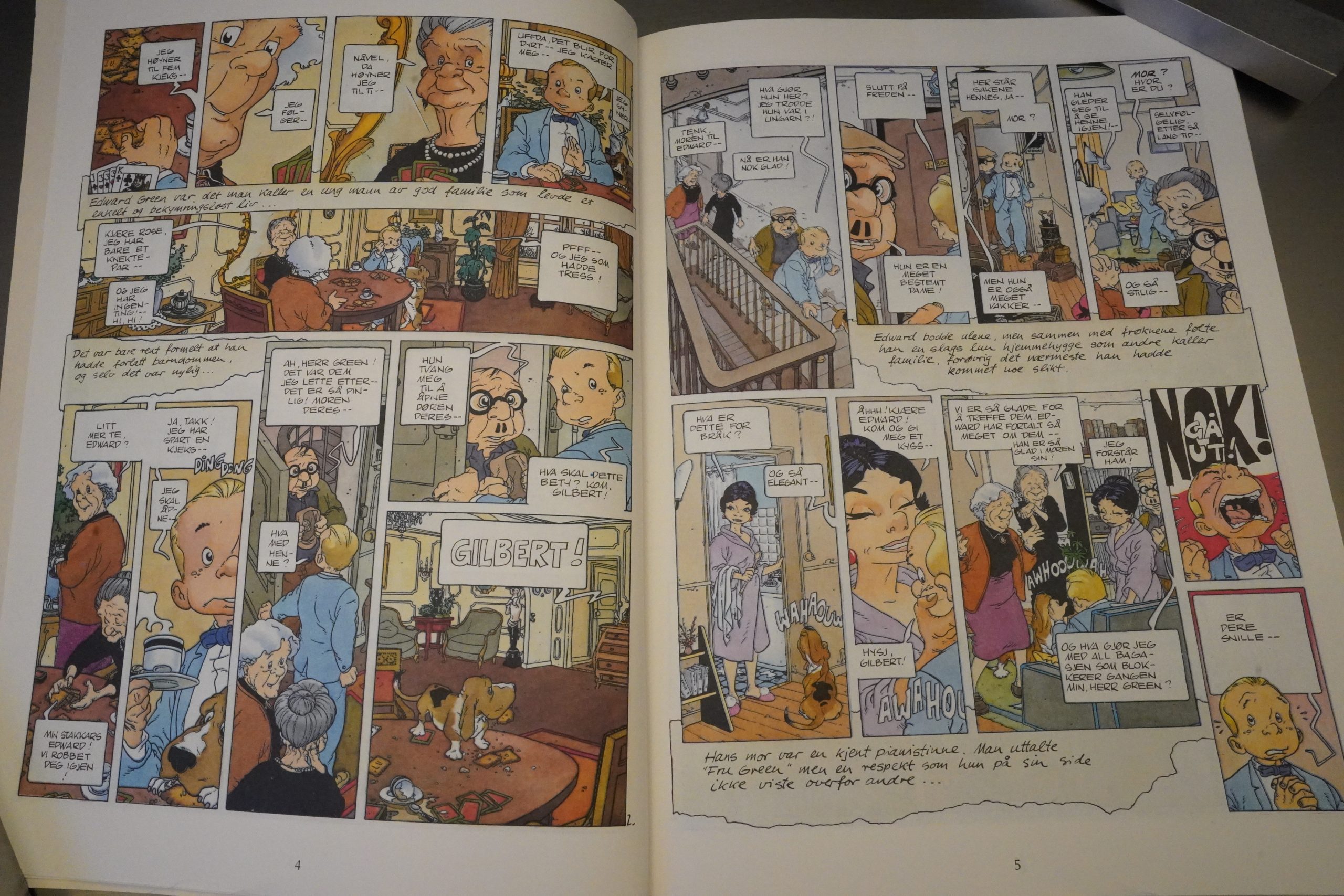

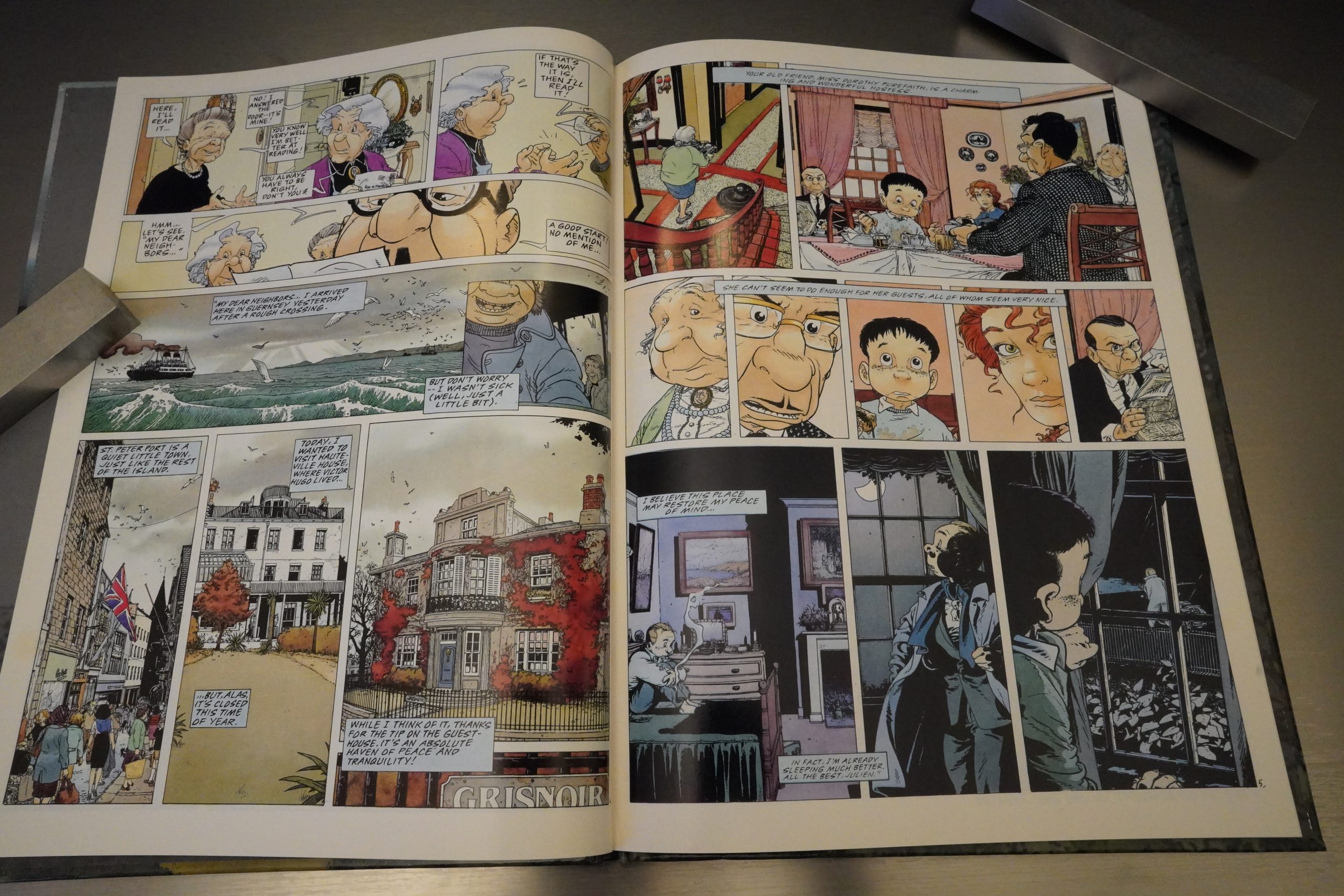

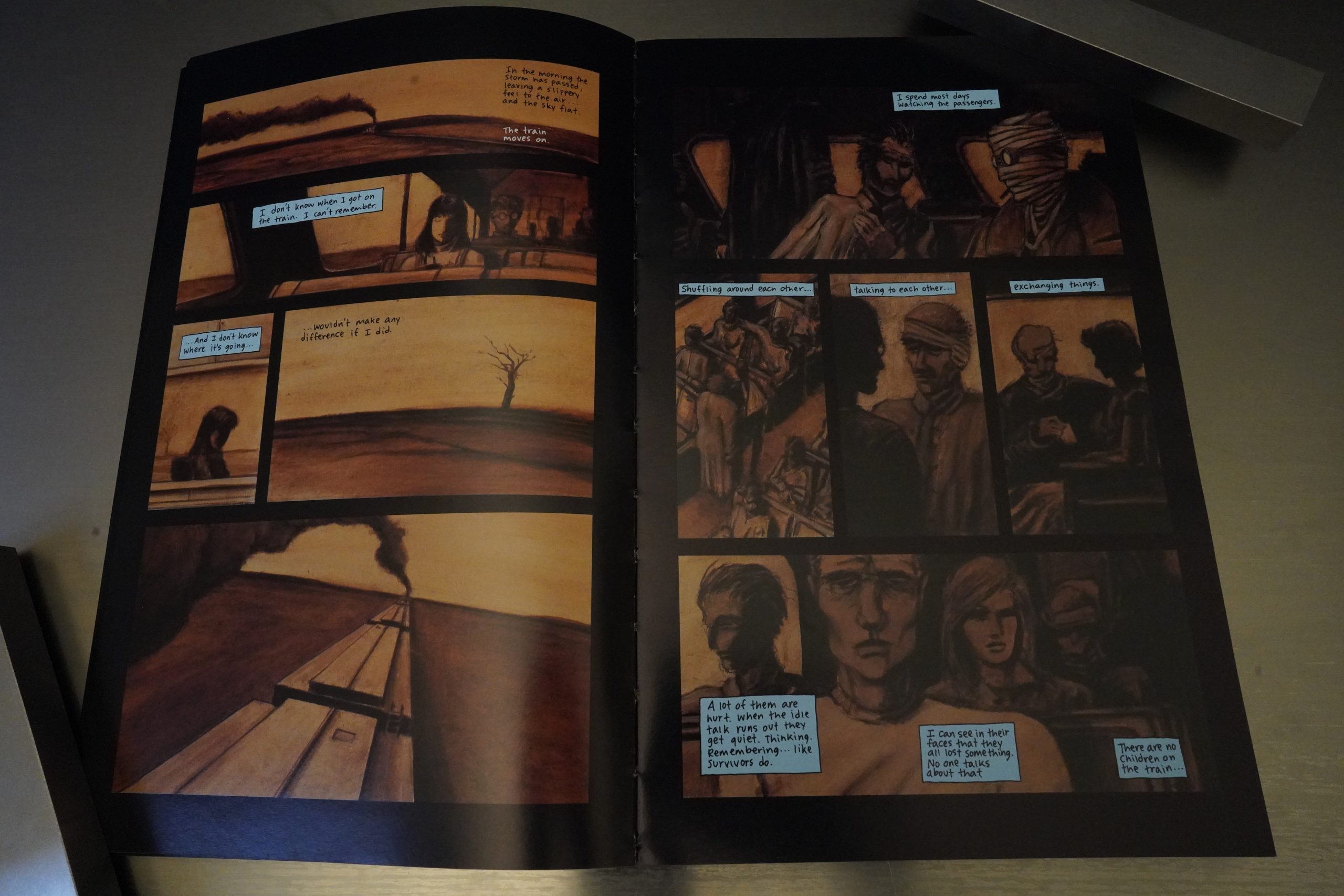

So I assumed that this was some sort of new beginning or something, but nope: We’re just dropped into a dream sequence at random, and then…

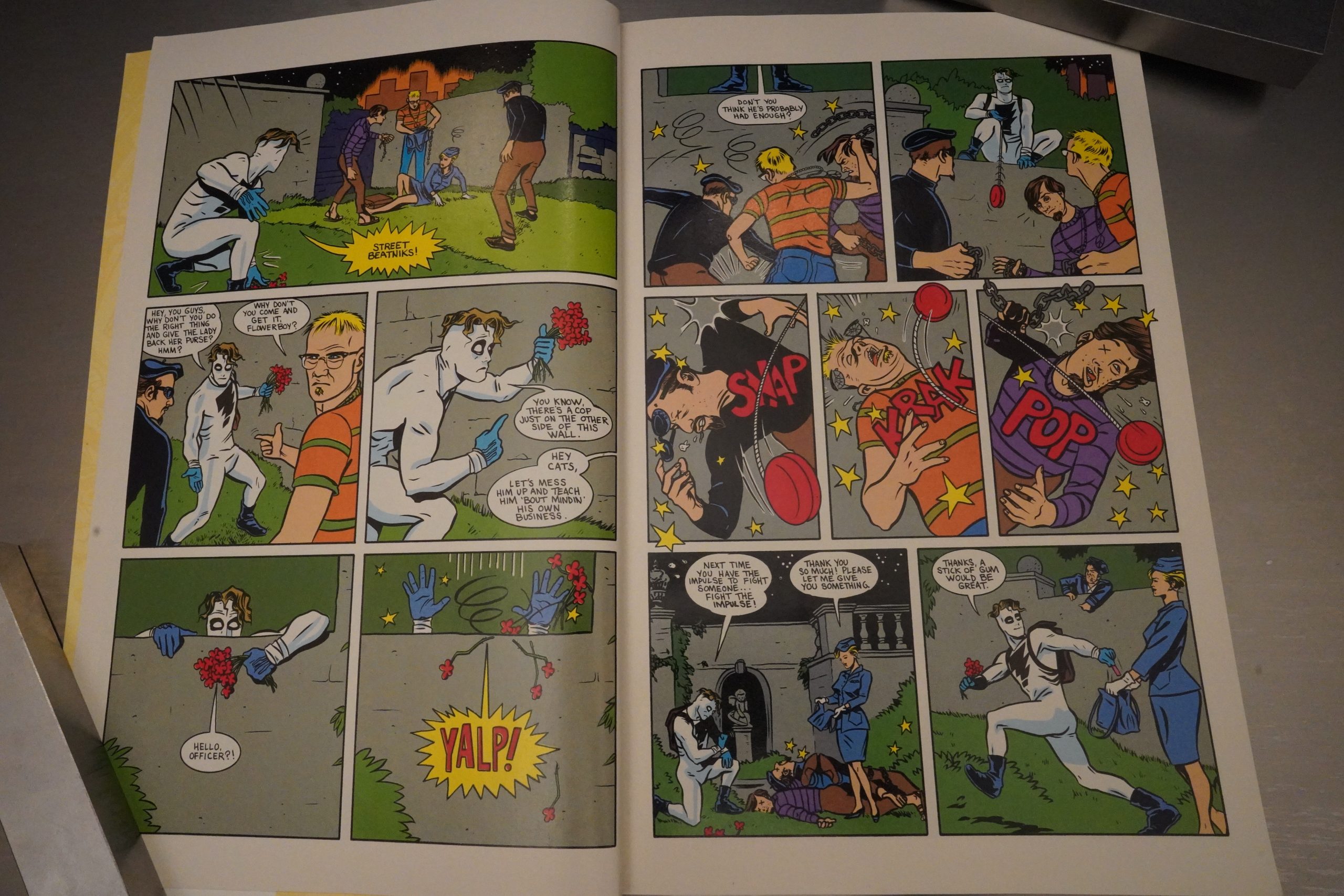

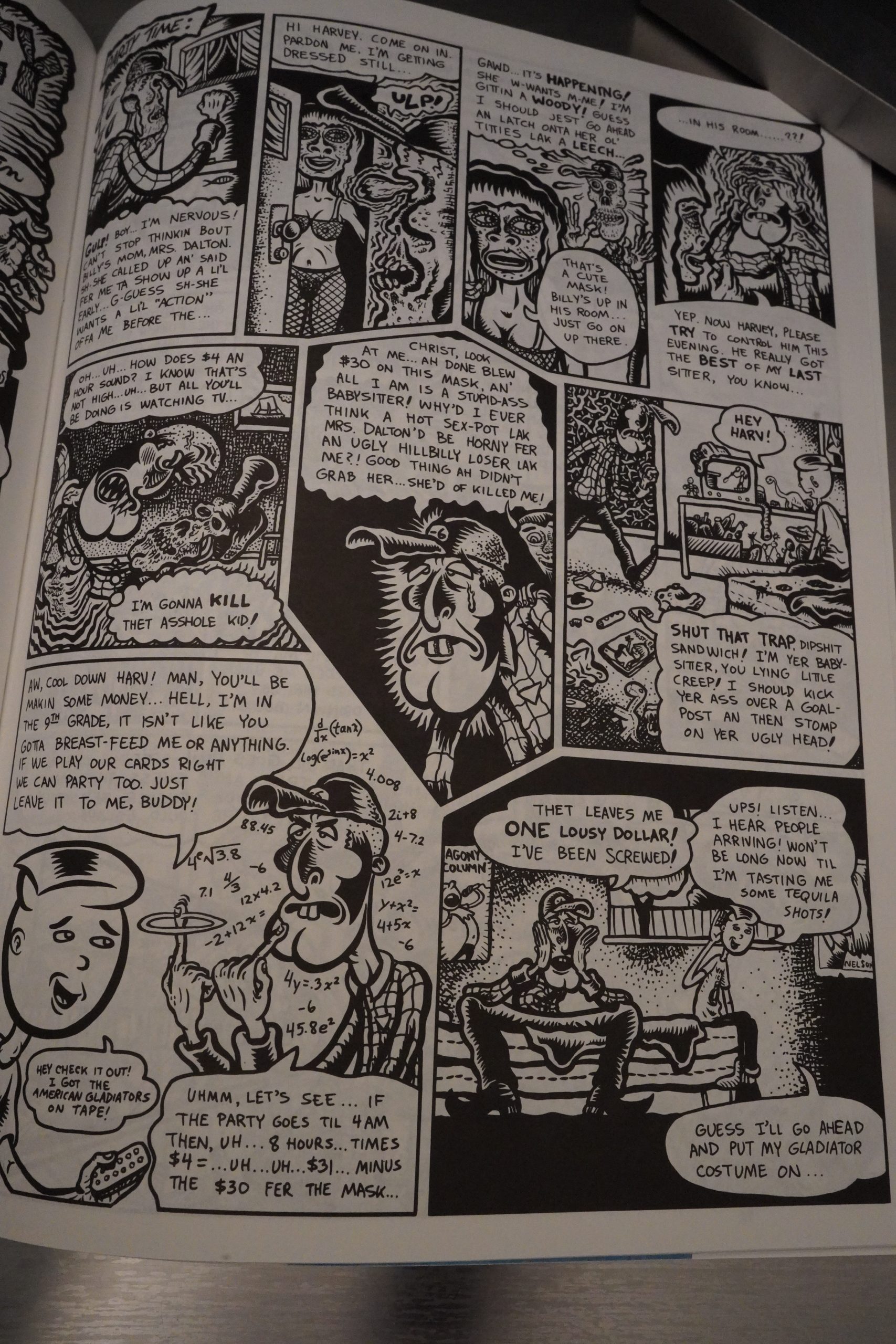

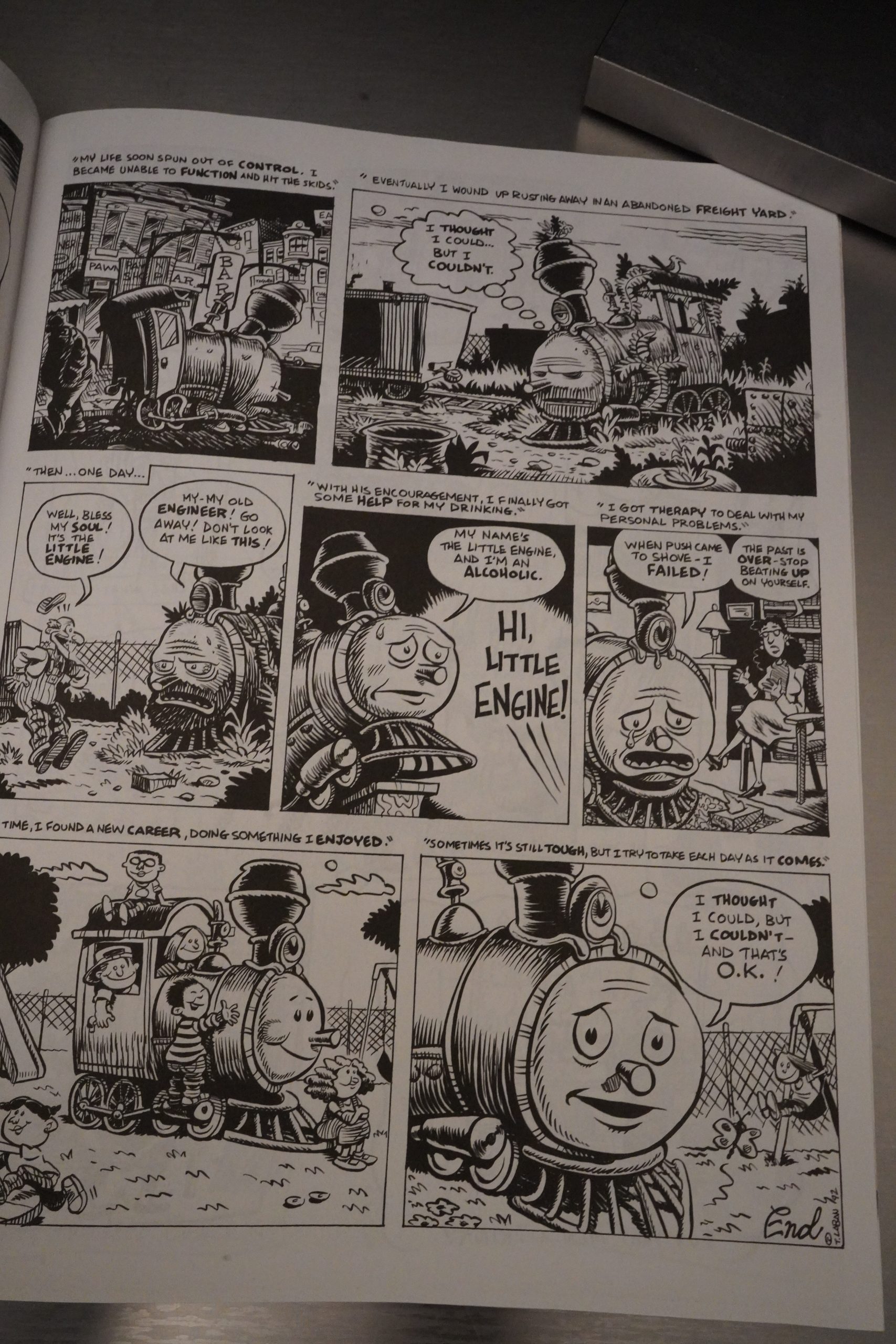

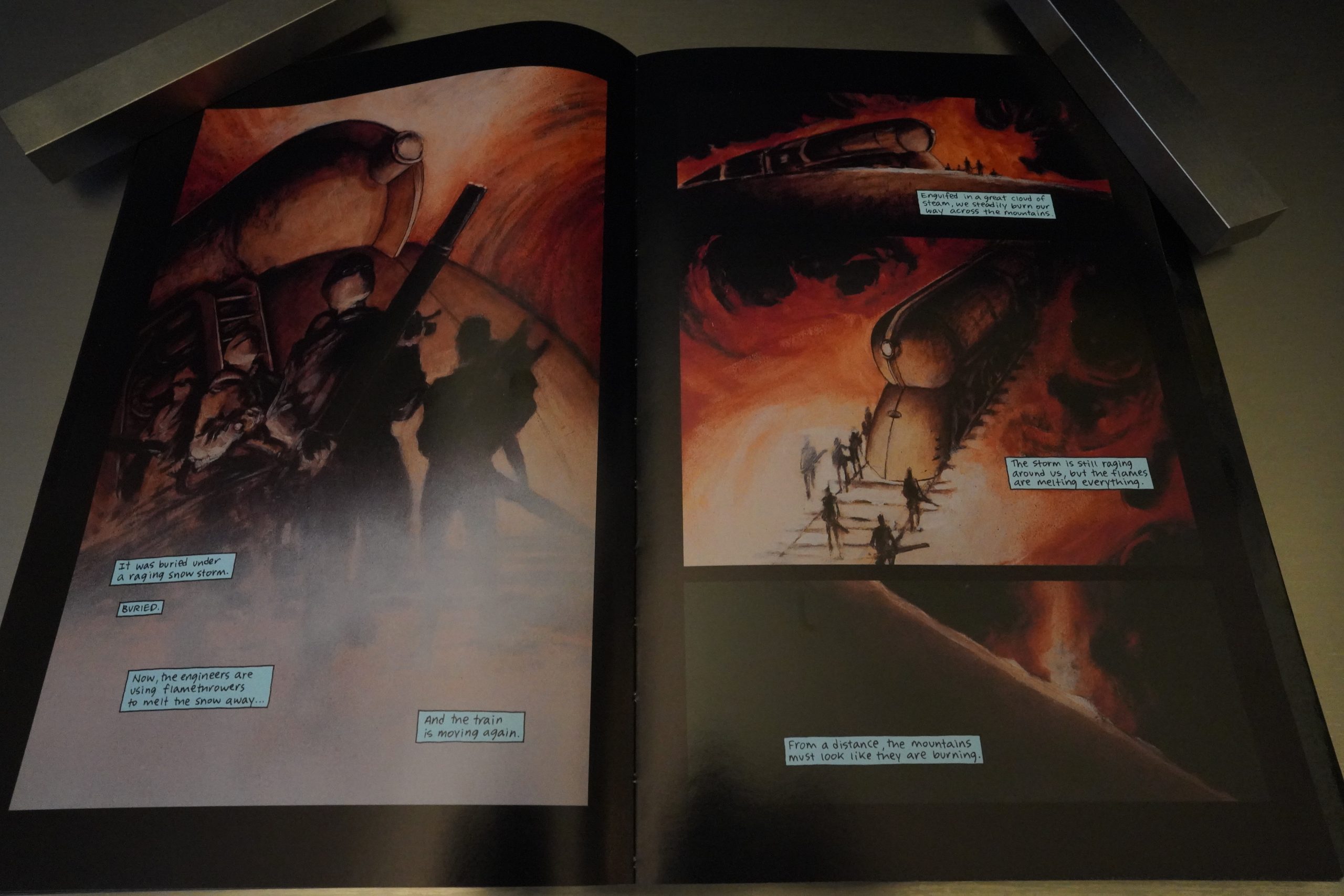

… we get the best action sequence ever.

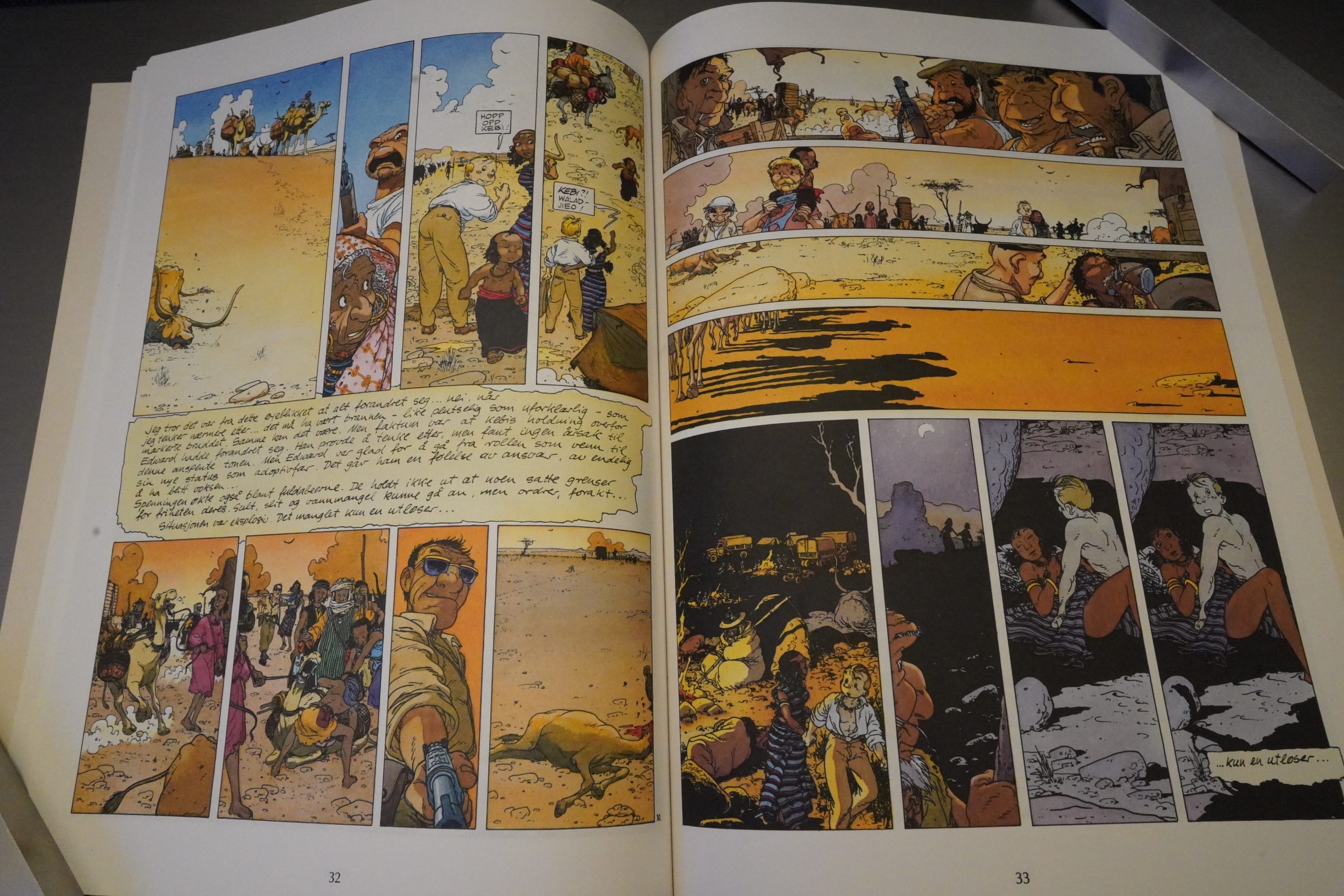

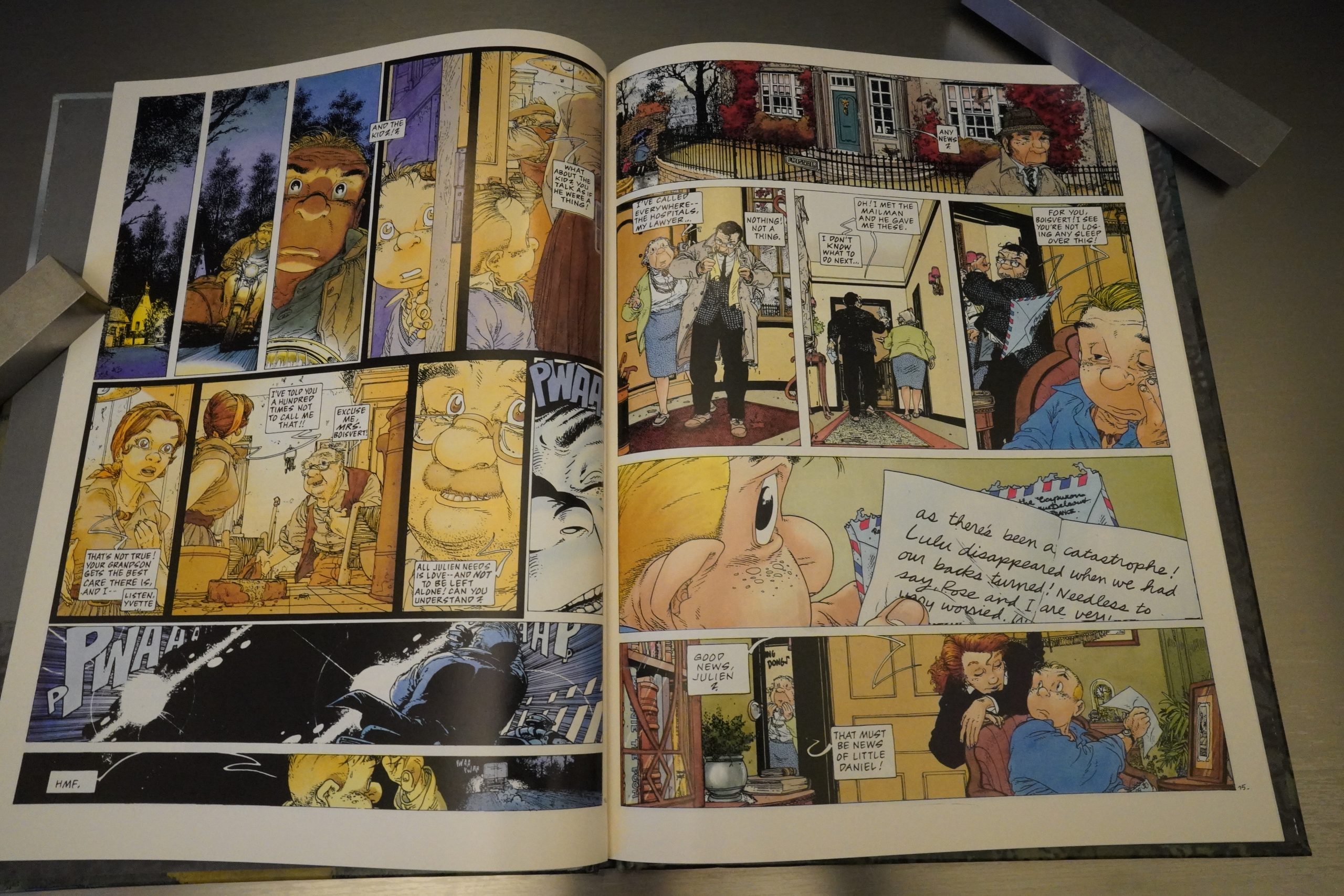

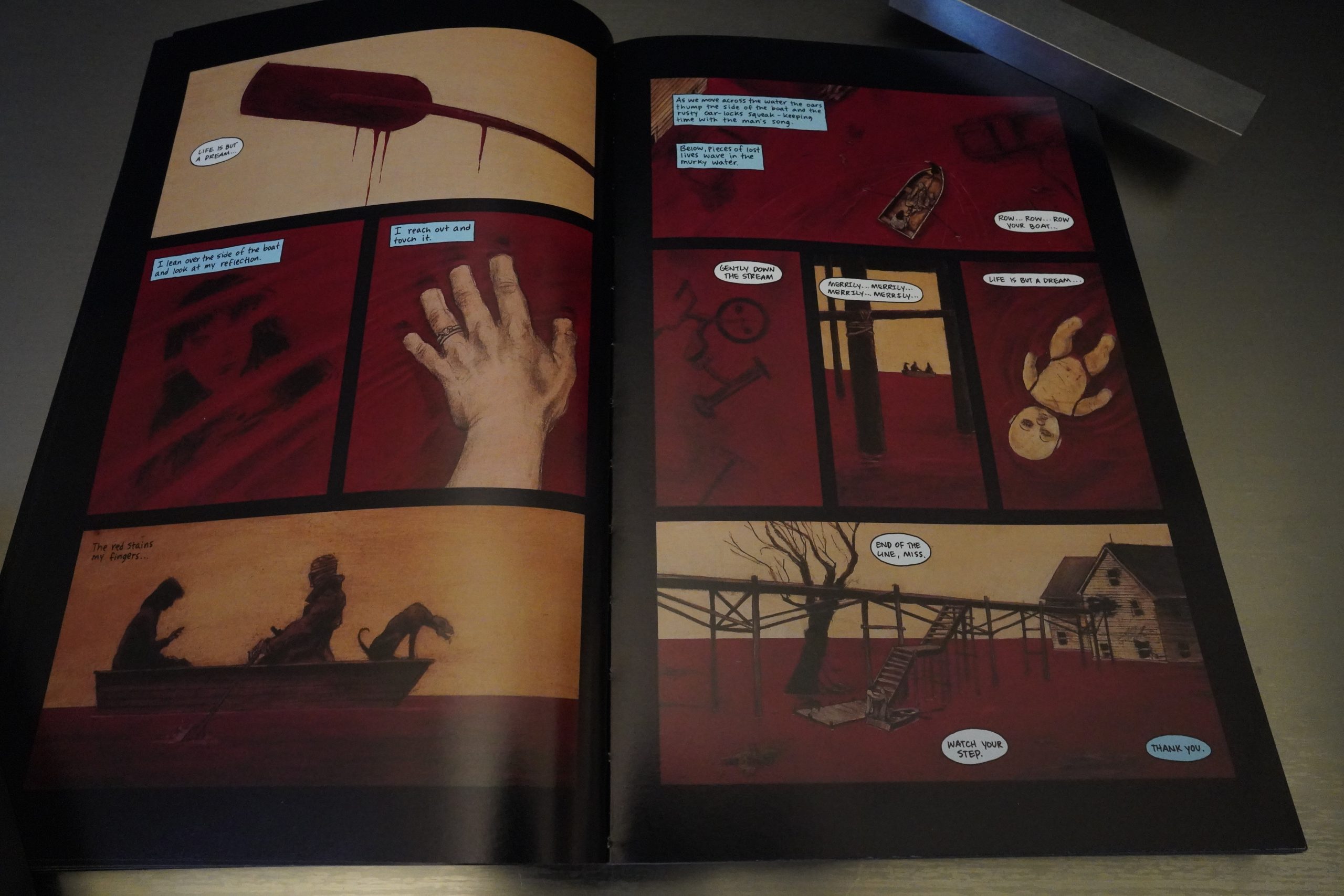

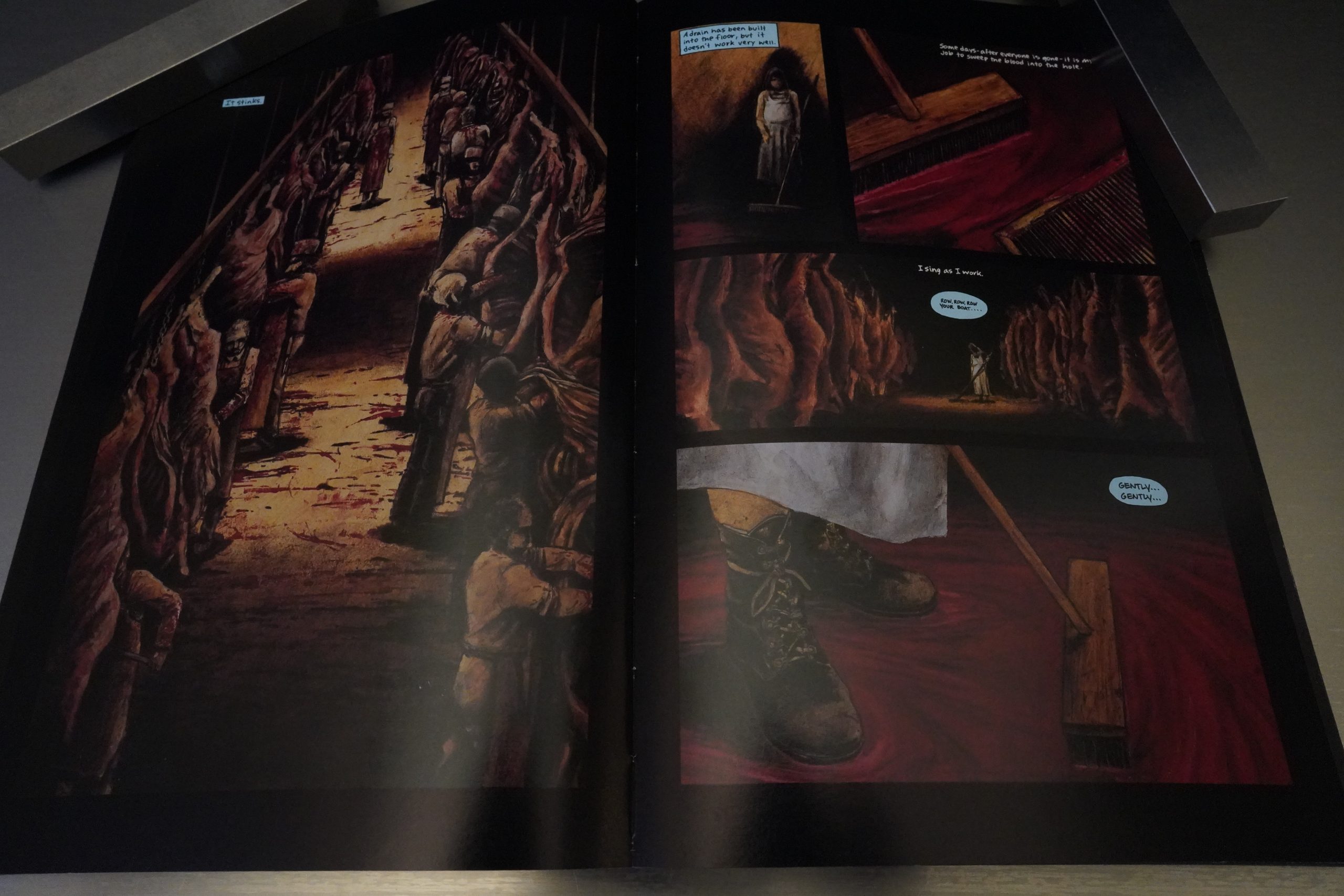

Man, the artwork here is so fresh and good looking. Allred’s artwork can sometimes be a bit stiff, but here it’s so lively and attractive. Lovely colours from Laura Allred, too, of course. So I can understand what he meant in that introduction: If I’d made something like this, I’d be pretty proud, too.

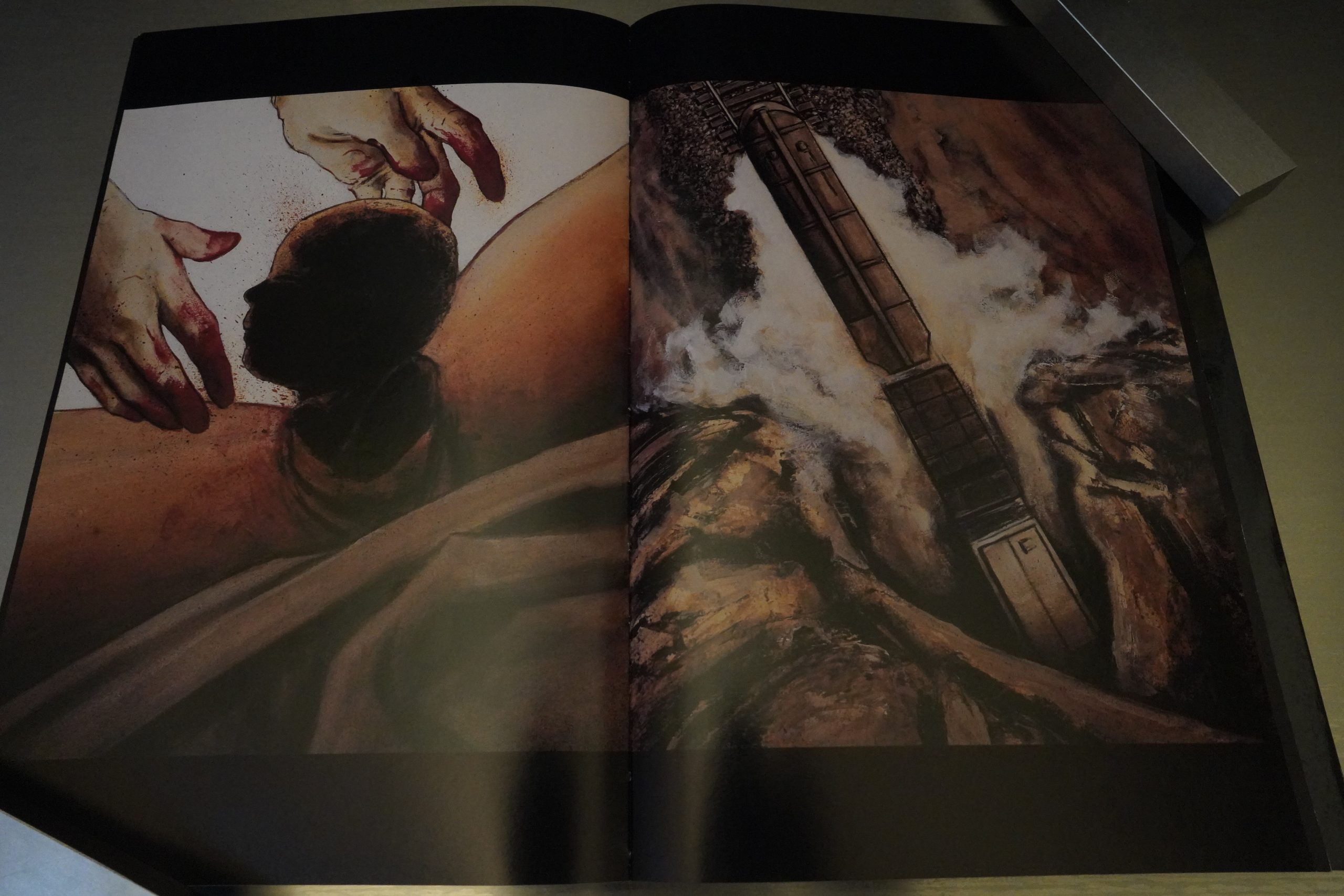

Best love scene ever.

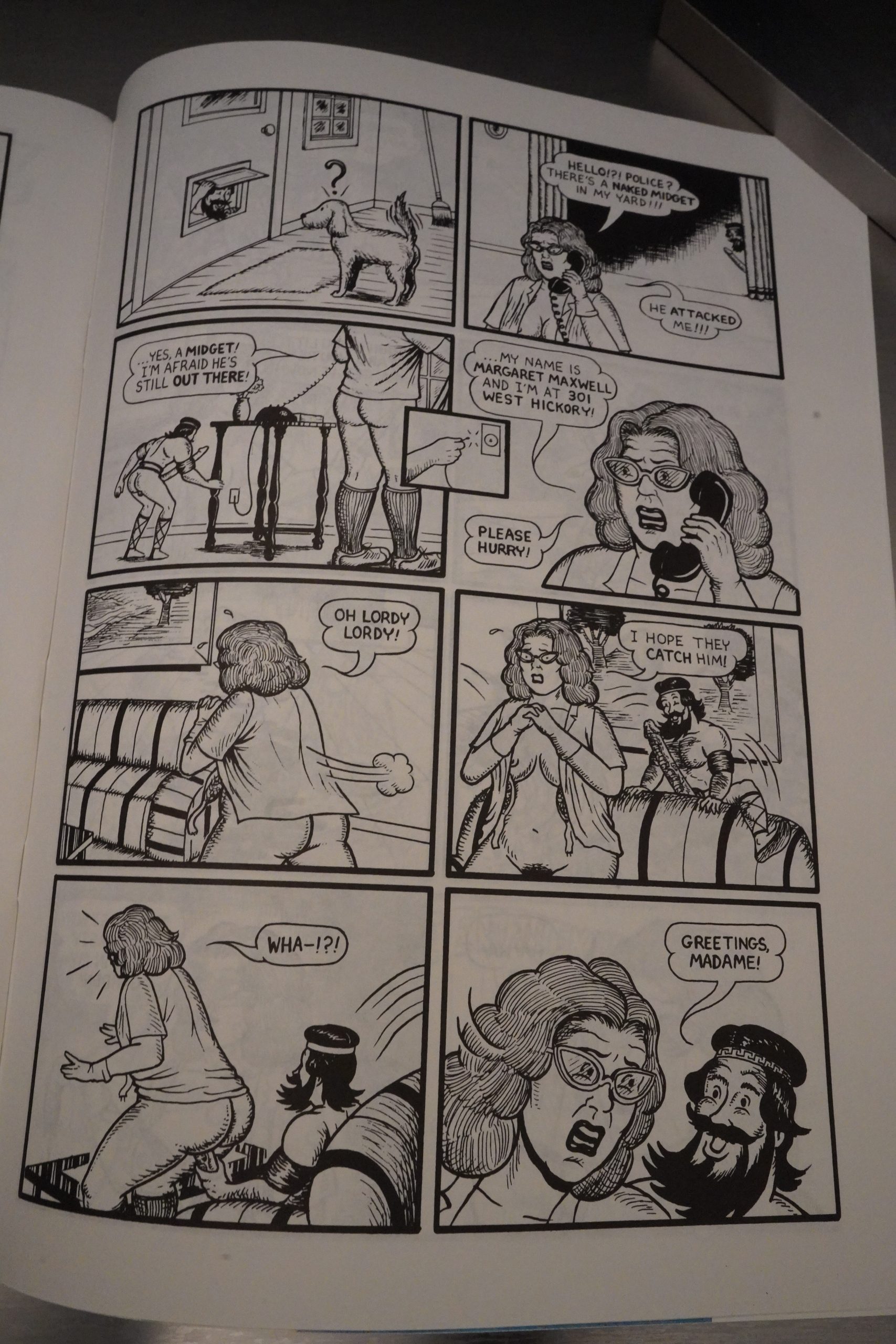

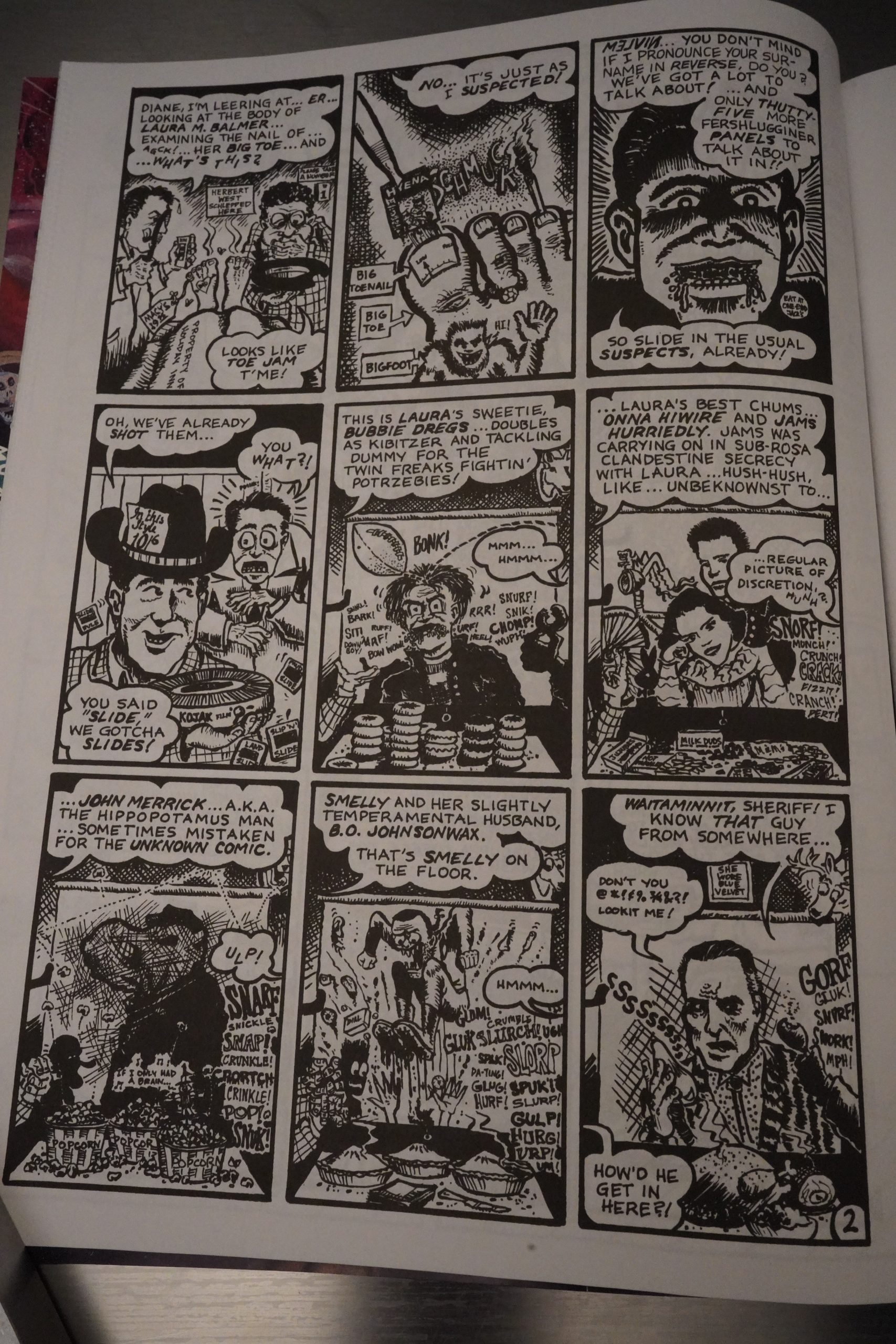

But… as much as I enjoy being dropped into the action without any explanation, Allred gives new readers little chance to catch up with what’s been going on. We probably don’t need it, but if I’d never read any Madman stuff before, I’d be pretty puzzled. (I’ve read some of the later stuff, here and there.) Like: Who are all these people, anyway?

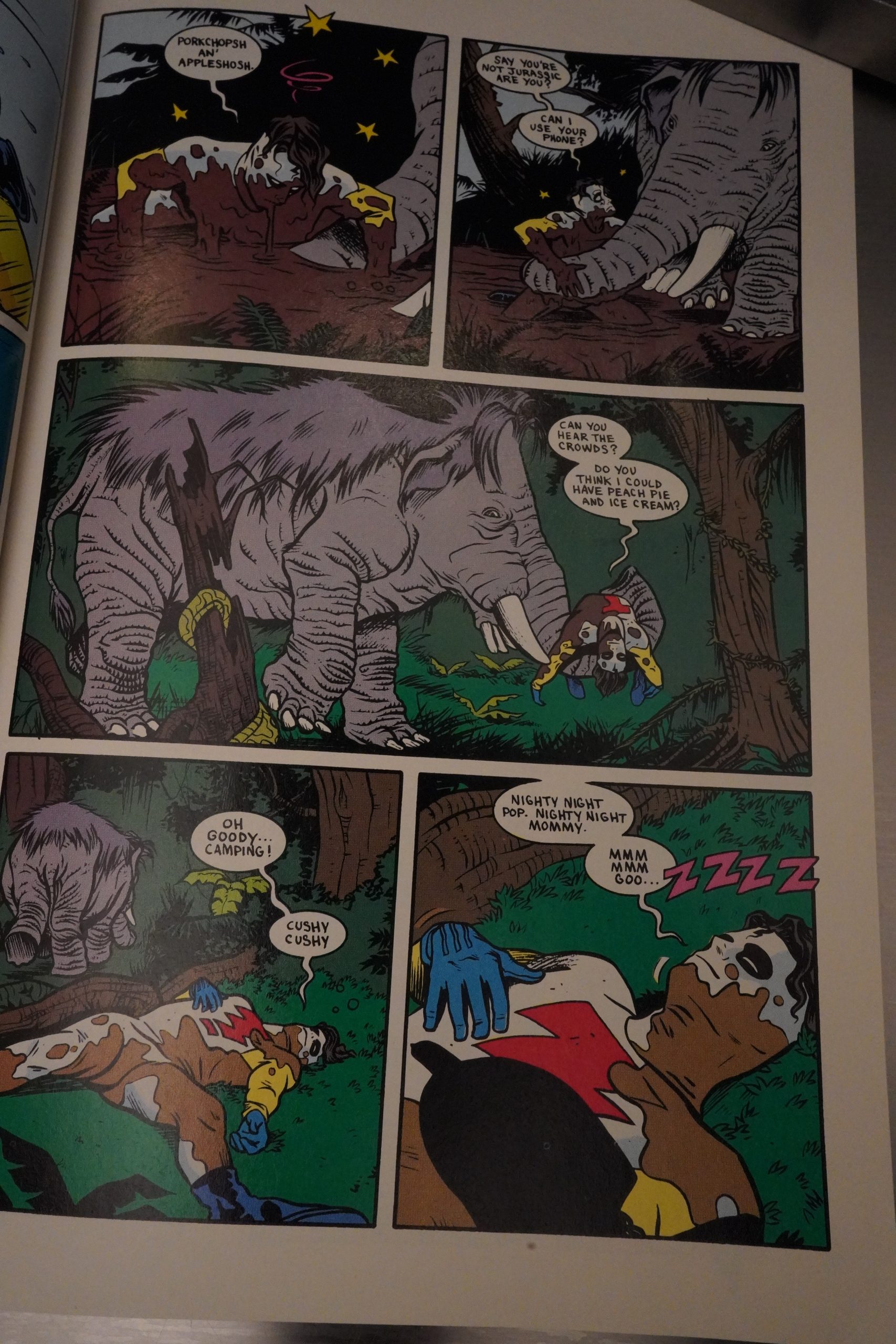

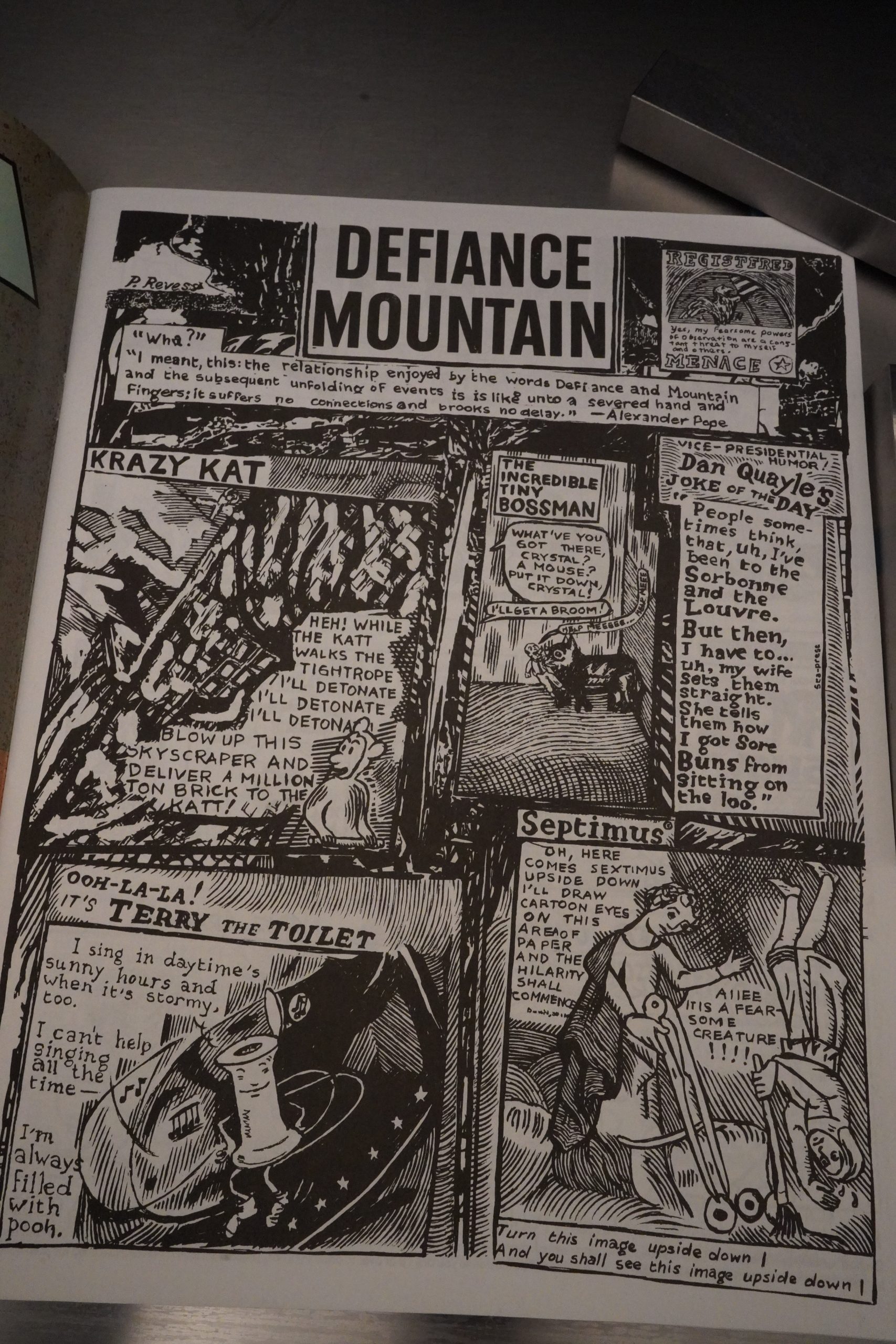

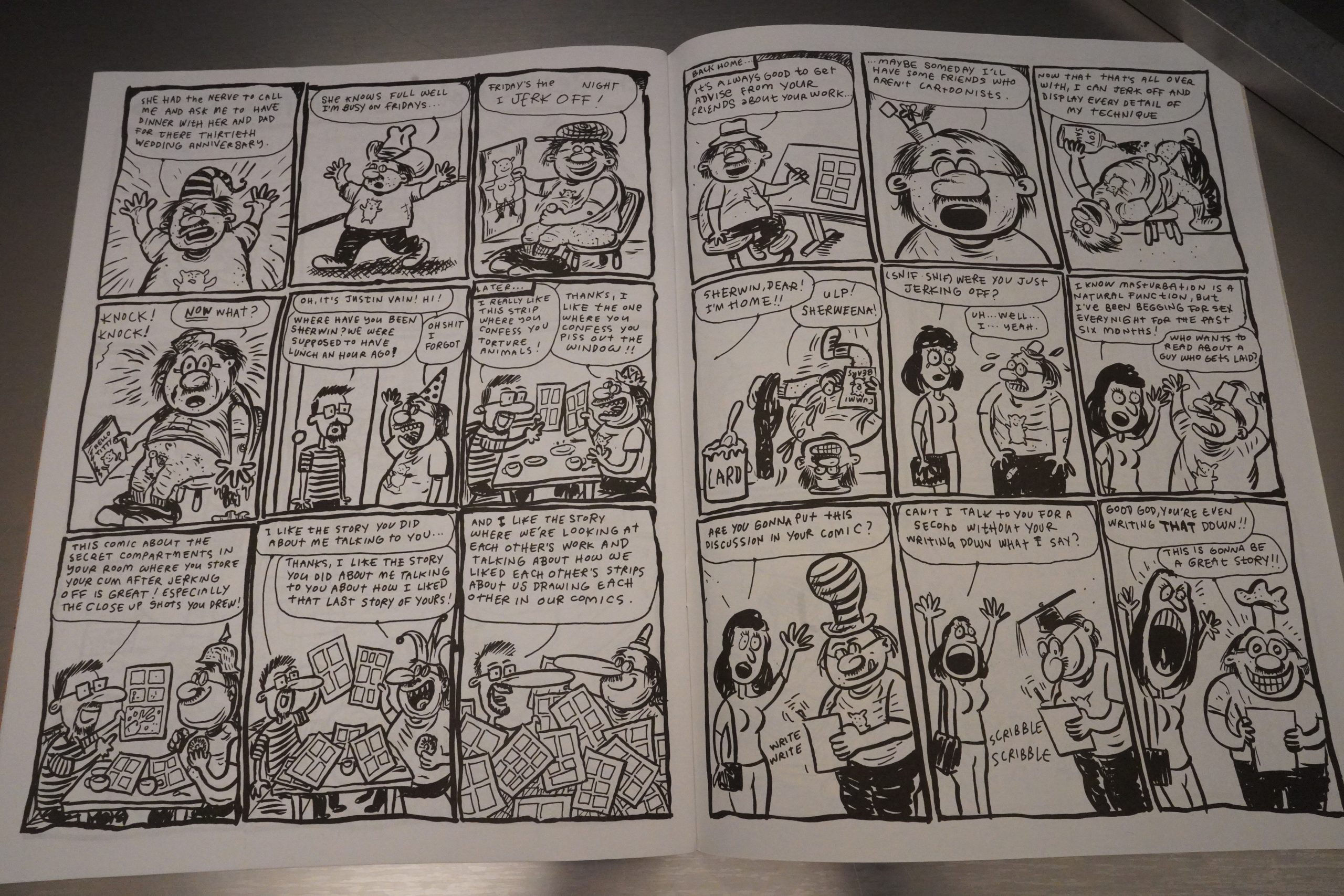

Is Madman channelling Zippy?

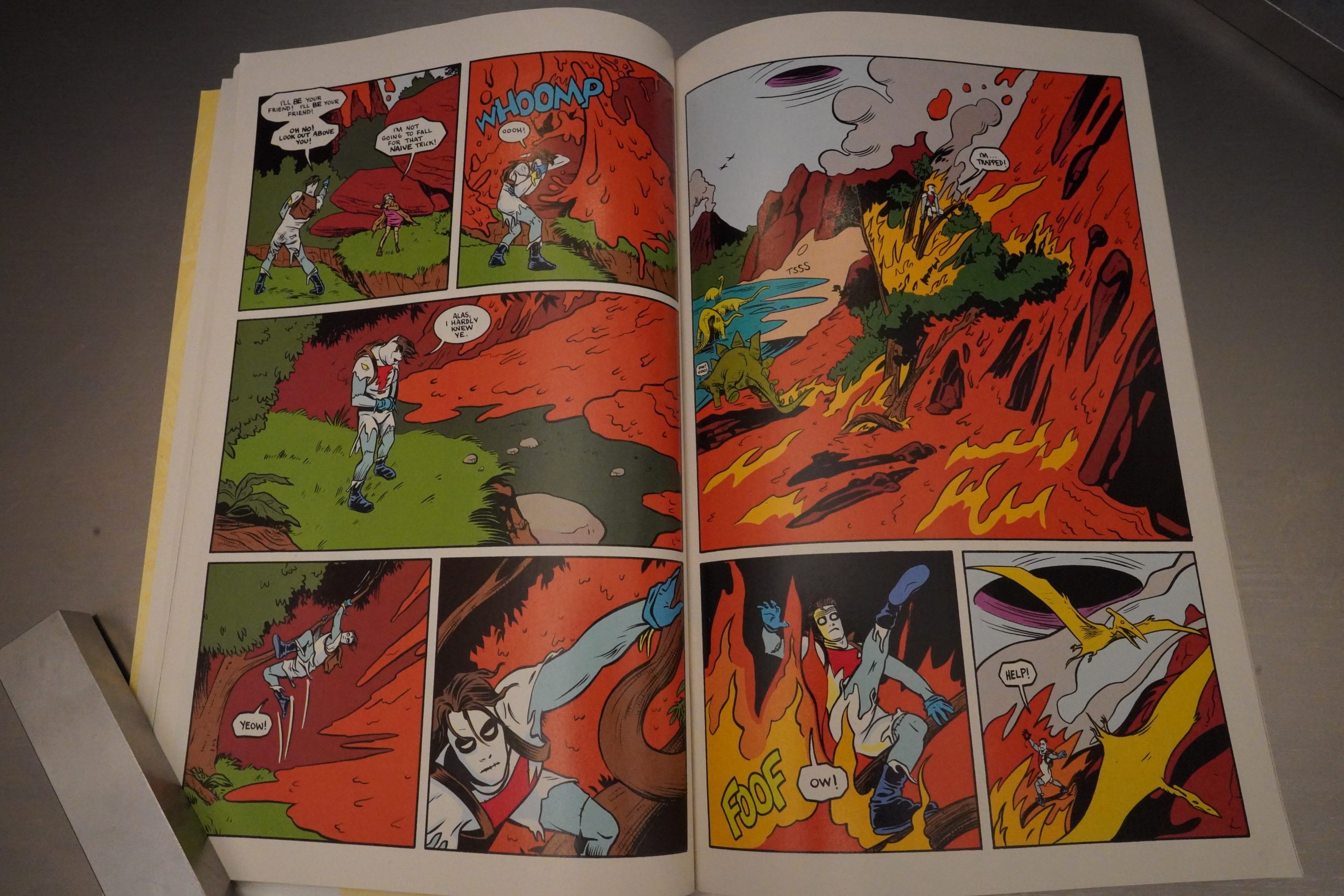

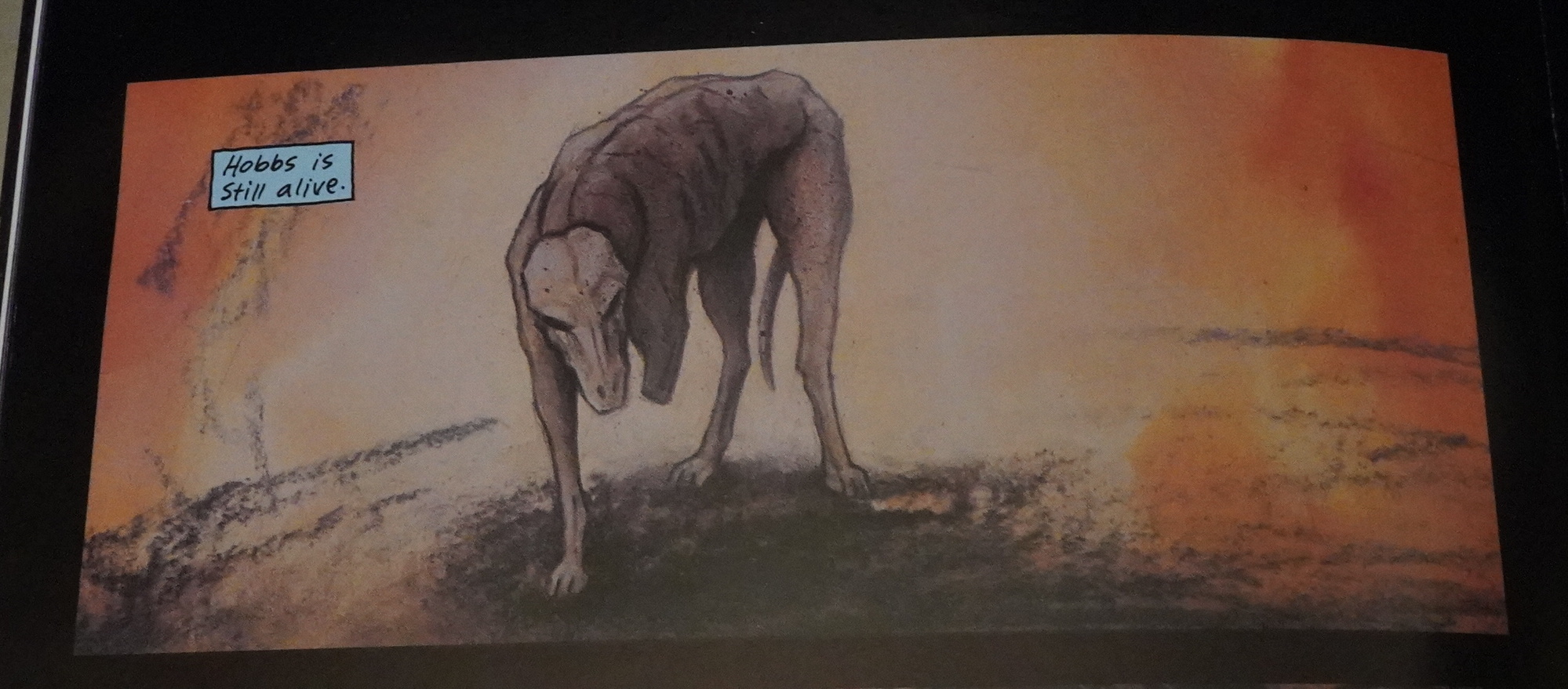

We get a small handful of different adventures in this collection, and they’re all fun, told in a way that zips along, with gorgeous artwork. But there’s something slightly off sometimes, like when in this goofy story, the villain (an old scientist woman) disappears under some lava. It’s… “well, OK”?

It just seems off for something that’s this whimsical. Or perhaps it’s not whimsical enough, so her being killed off like this feels like more of a real thing that should have an impact, somehow?

I don’t know. It’s a fun book, anyway.

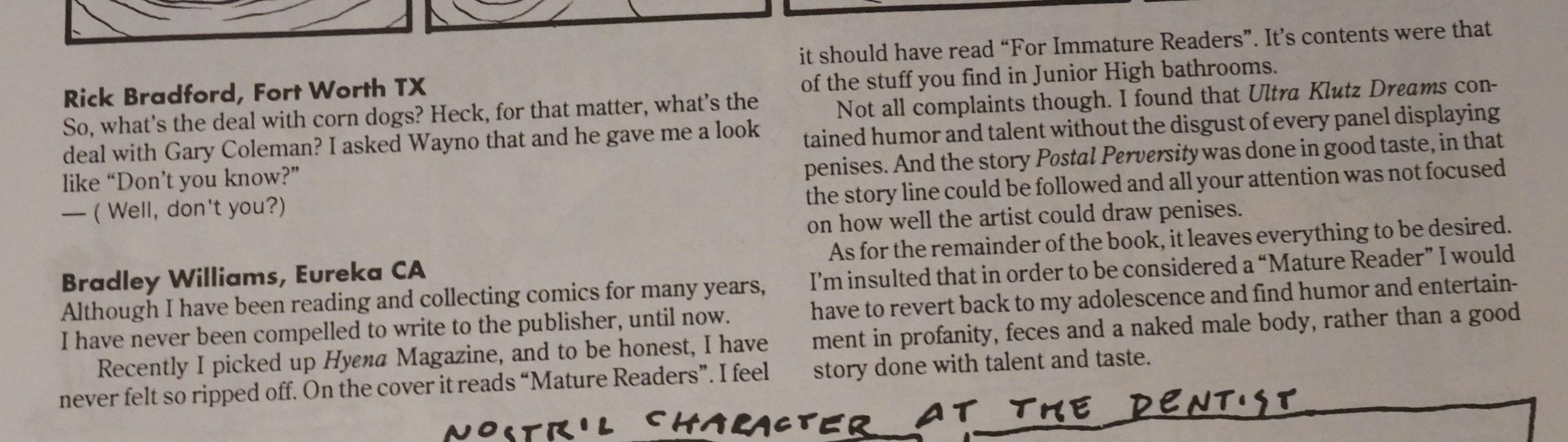

Comics Scene Volume #2, page 27:

Madman himself isn’t the psycho-

pathic kinkoid his name might suggest,

and the 1990s superhero code might

demand. He’s a sweet-tempered amne-

siac named Frank Einsteini who has a

face full of scars (mad scientists resur-

rected him after a car crash), a heart

full of wonder (he confronts new men-

aces with “Gosh'”) and a closet full of

costumes (he rarely wears the same

one twice). Playful would best describe

his exploits.

The all-ages sensibility comes easily

for Allred, a father of three whose ear-

lier comics were altogether darker. “I

was doing fairly esoteric, semi-under-

ground work before,”

says Allred,

referring to books like Grafique

Musique, Dead Air, Creatures of the Id

and The Everyman. “When my eldest

son wanted to take some of my work to

school for show-and-tell, I said, ‘Uh,

I’m not sure if they would like it.’

“I realized I wasn’t really enjoying it

that much either. I thought about the

comics I loved, like Jack Cole’s Plastic

Man, The Fox, Matt Wagner’s Grendel,

Bernie Mireault’s The Jam, the old

Fantastic Four…l wanted to do some-

thing in that spirit.”

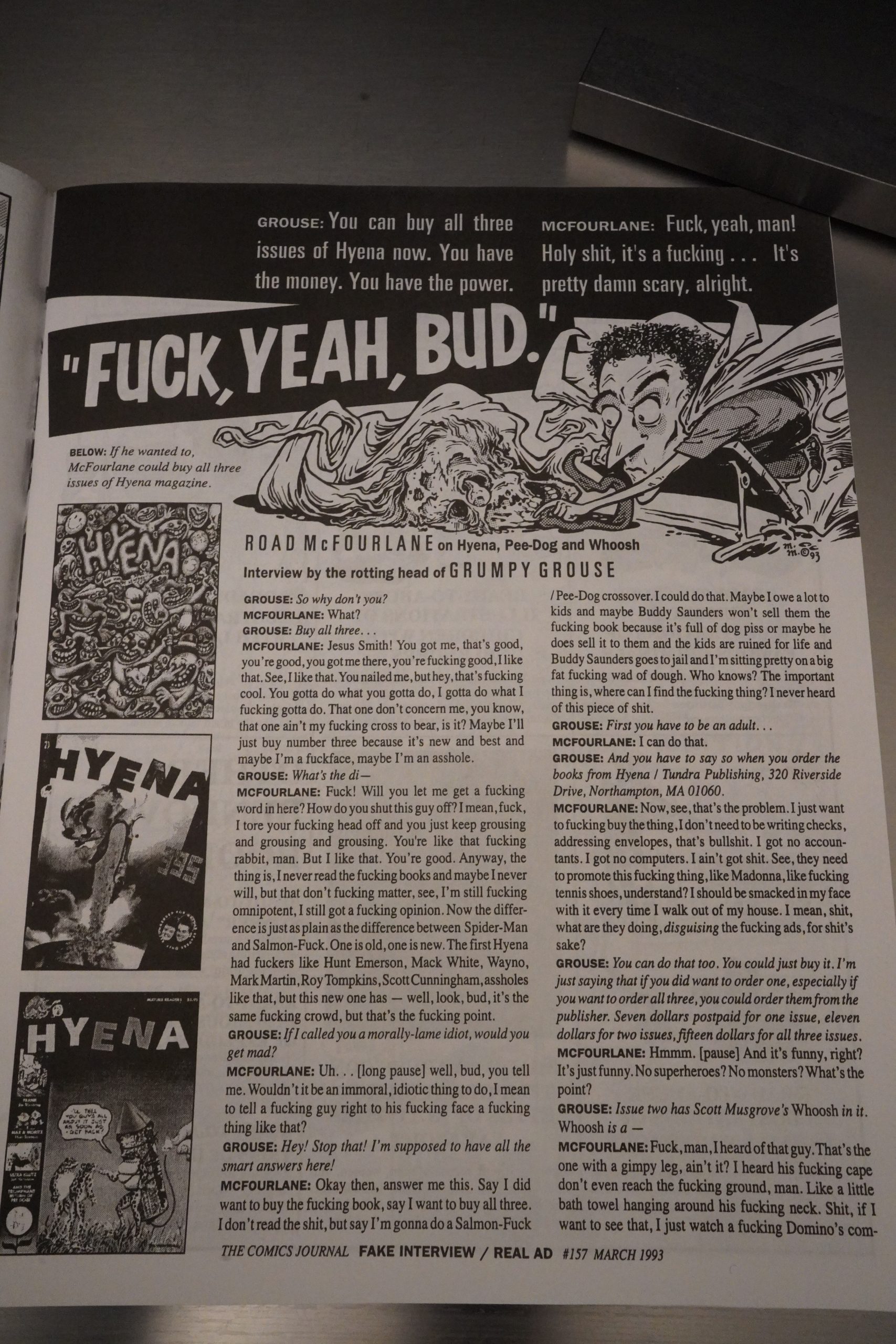

When Tundra published Madman

#1 in 1992, though, its hero wasn’t

quite his modern happy-go-lucky self.

He sometimes behaved like, well, like

a madman, at one point yanking out

someone’s eyeball and popping it in

his mouth. Still, the three-issue,

two-color series had its wacky side.

Madman bopped the naughty with a

yo-yo, and danced the Batusi, the

swim and the jerk in the flip-action

corners.

The second three-issue series,

Madman Adventures, had day-glo

color from Laura Allred, Michael’s

wife, a former art major and lifelong

painter who manages a jewelry shop

full-time. Allred calls the series “a

burst of enlightenment—I was doing

exactly what I wanted to do.” No more

eyeball munchies—Frank Einstein

mellowed into a gentle goof, swooning

after his girl friend, the freckly Joe,

while tussling with robots, dinosaurs,

secret agents and ghost tribes.

Unlike Madman, Madman Adven-

tures wasn’t intended as a trilogy; the

back of #3 plugged the next issue’s

story, “Horror on the High Seas.” But

then-publisher Kevin Eastman sold

Tundra, his money-losing “alternative”

imprint, to Kitchen Sink, a bastion of

independent comics. Allred says other

companies courted him while he

waited for Kitchen Sink’s offer, and

there was even talk of a special Image

imprint to publish the book.

The best offer came from Dark

Horse; Allred says he consulted with

Eastman before accepting, “because he

really did right by me. Kevin said to do

what was best for me and the book.”

Once Allred signed, Dark Horse blitzed

the market with Madman promo piec-

es, retailer contests and such hoopla.

“Retailers looked at Kitchen

Sink/ Tundra as artsy, and appealing to

a little more selective crowd,” says

Allred (for “more selective,”

read

“smaller”). “On the other hand, work-

ing with Kitchen Sink/ Tundra proba-

bly gave Madman an extra push of

respectability. ”

Rich Kreiner writes in The Comics Journal #164, page 53:

Madman Adventures represents a distinct

improvement. It’ s shorter, better crafted, better

balanced, and more constrained. Allred plainly

has a clearer idea Of what he wants to do, and

here enthusiasm does carry the day. The plot is

a relatively steady escalation through to an

endi ng that makes your normal deus ex machina

resolution seem j ohnny-come-lately. More con-

fidence is shown in dialogue and art. A surer

sense Of direction allows a more natural flow Of

focused, throwaway jests. Allred avoids facile,

movie-grade embodiments Of foul eee-vil. The

character of Madman is more at peace in his

made-up world; he is happier in this series, and

so are we. Where the uneven deli very in the first

series stiffened our allegiance to reality, here it

is weakened. (Though I still wish Allred would

get a certain body of this world’s information

and knowledge straight: in the Adam and Even

myth, it’s applefirst, fig leaves second.) As has

been the case before, the addition Of color adds

clarity and a visual decisiveness to the art,

Allred’s most polished and conventional to

date.

While the second issue is consumed with a

quirky time-travel story, the first, with its more

mundane focus, shows Allred at his most irre-

pressibly representative — that is, careening

back and forth between the stoopid and the

inspired, the clichéd and the delightful. Take

the early sequence involving a meeting with

street beatnicks (funny!), a fight (dumb! con-

fusingly choreo-

graphed!), andhis

reward (funny!).

Since the reader

has already met

most Of Allred’s

Legion Of Un-

usual Characters,

the wild action

and ridiculousex-

planatory dia-

logue can unfurl

without fresh

weirdos continu-

ally popping up.

Theinquisitionof

Madman at the

handsofhis lady-

love’s father is a

fine sequence

where idiotic op-

timism meets a

true-to-life terror.

In Madman’ s

escapades so far,

the twin drives of

his personality,

lunacy and be-

nevolence, have

yet to approach

the frontiers

scouted by, re-

spectively, Bob

Burden’s Flam-

ing Carrot and

Mireault’s The

Jam. Still, in

stooping to a

straightforward

superhero mock-

ery, at least Mad-

man represents

Allred’s self-con-

trolled power

dive into a hell of

his own making.

And, to be fair, it

is not without its

moments… just

not so many as

one might wish.

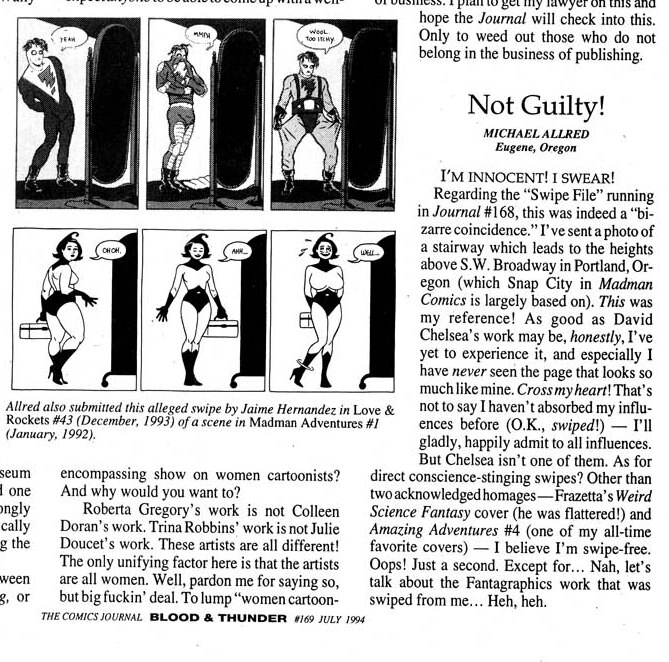

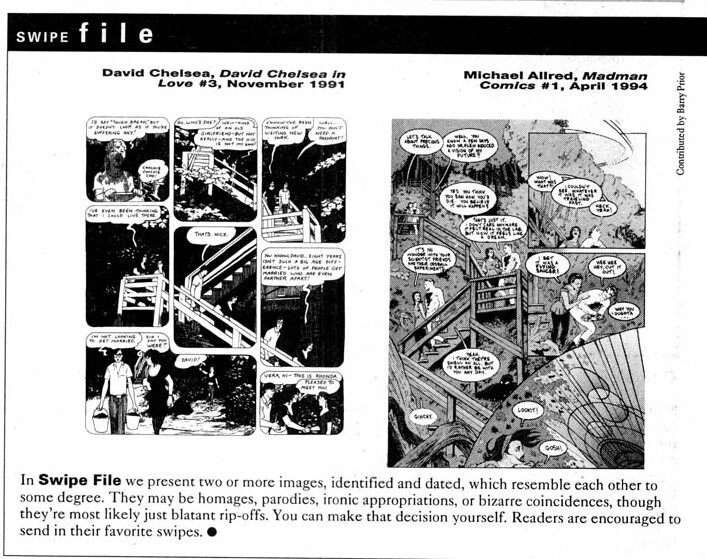

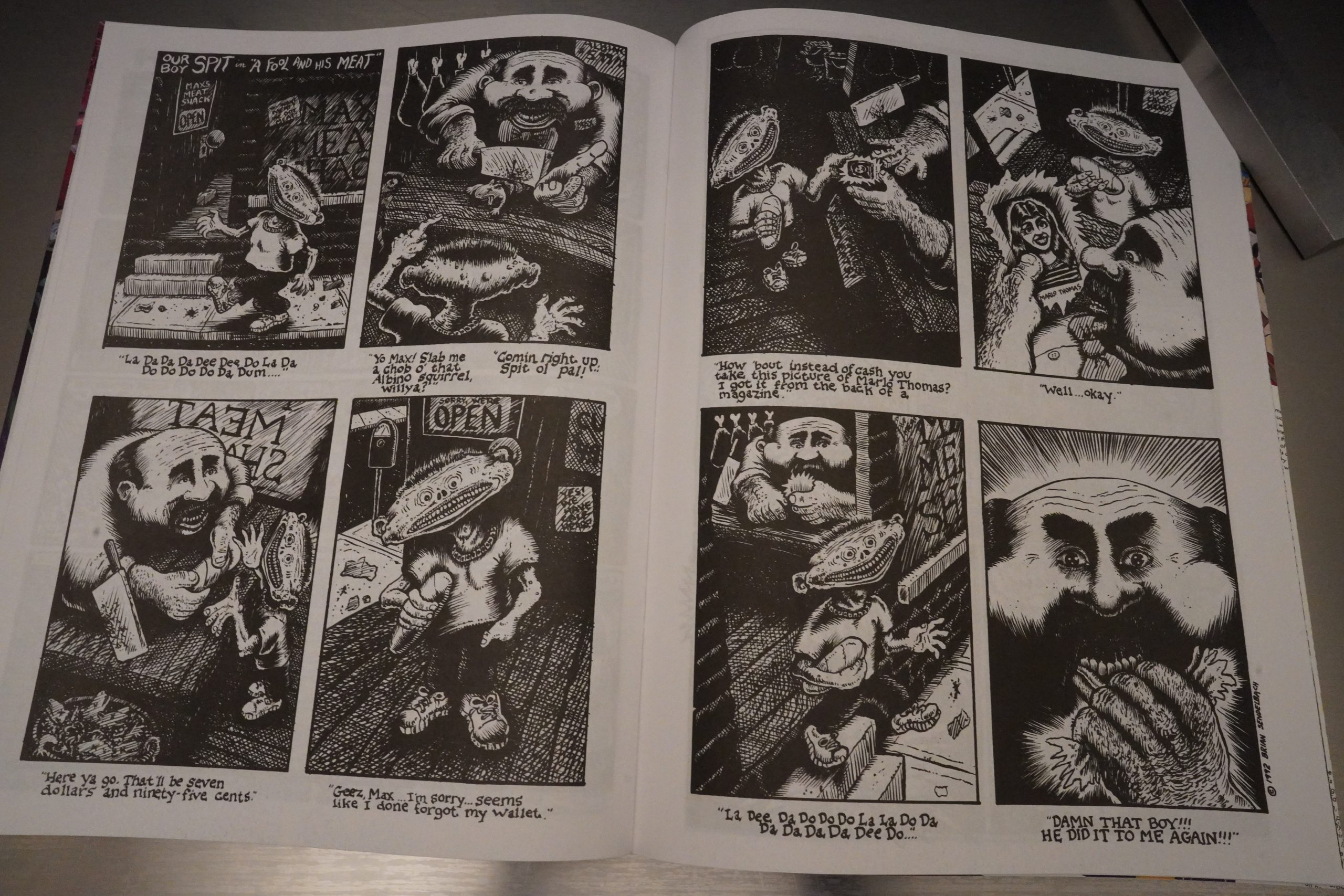

Oh, Allred landed in the Swipe Files, but denies swiping?

Here’s the entry… doesn’t look extremely swiped to me.

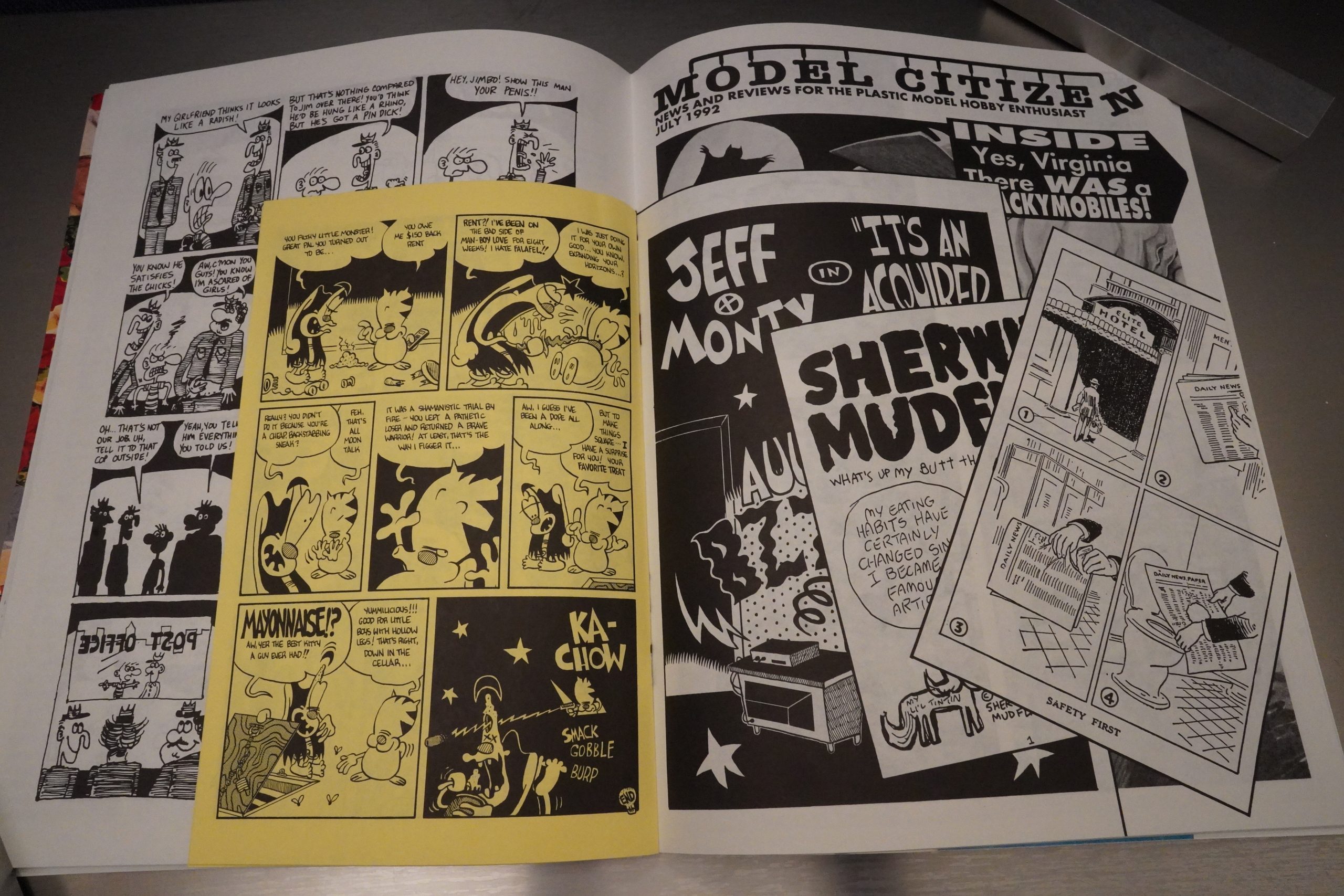

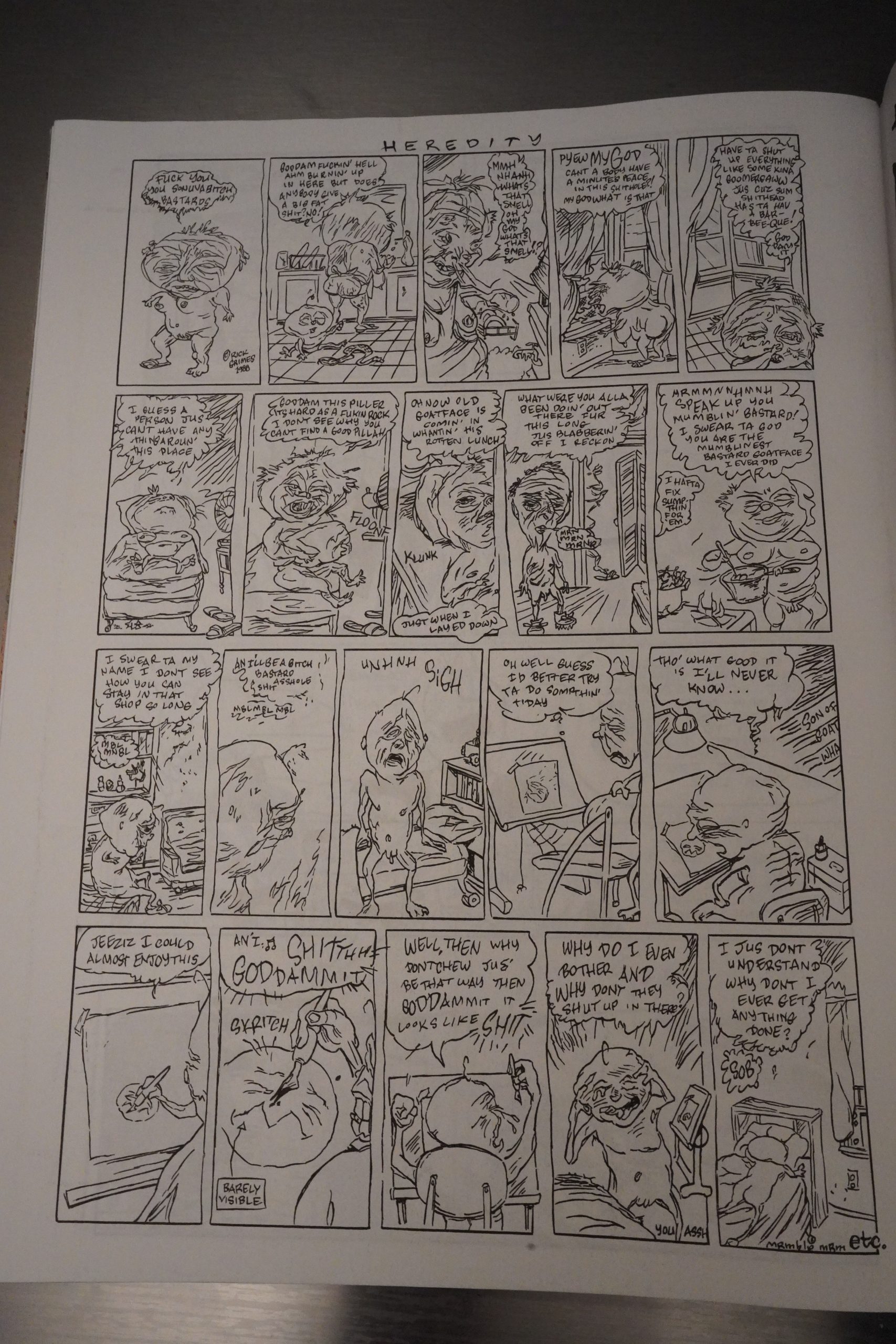

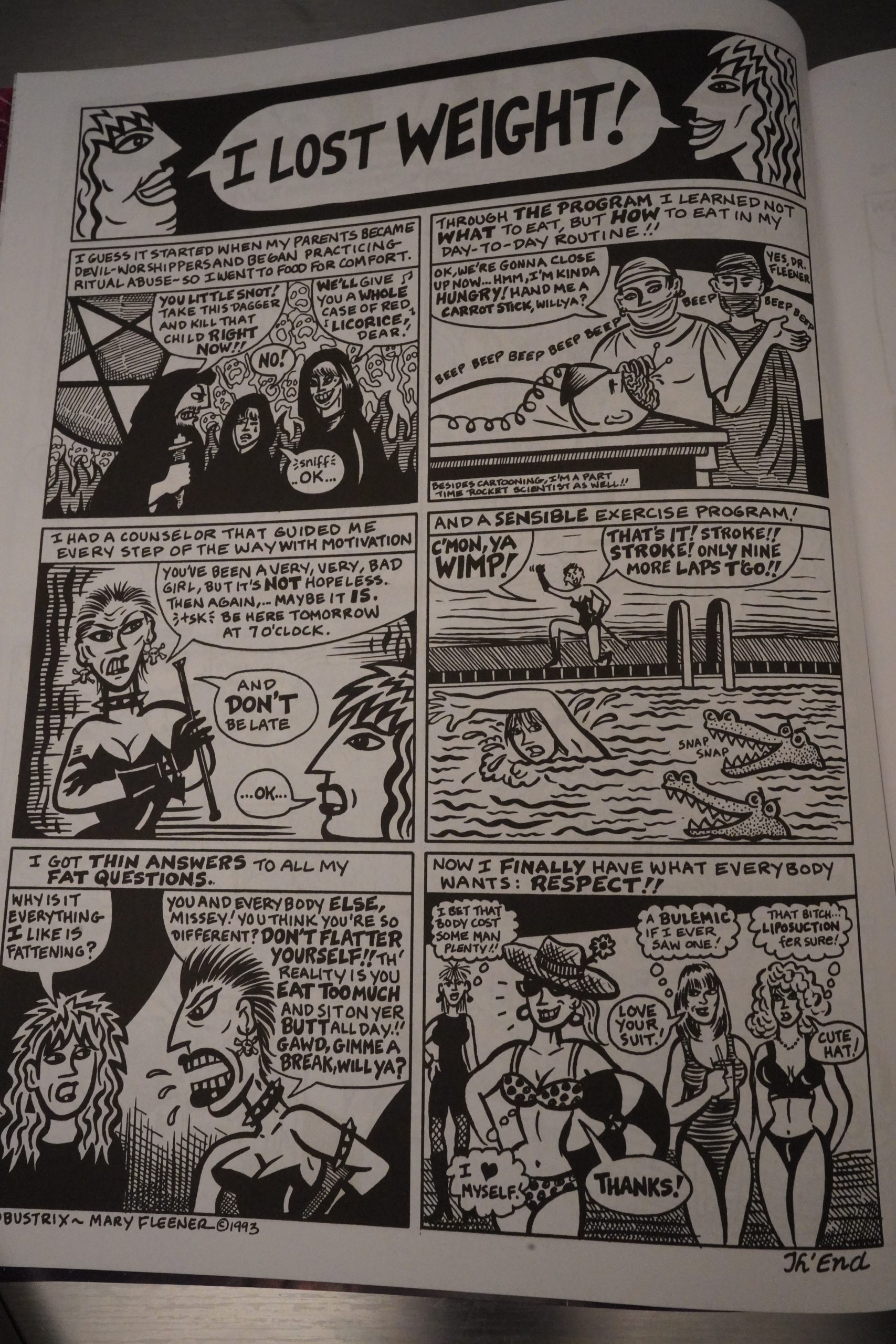

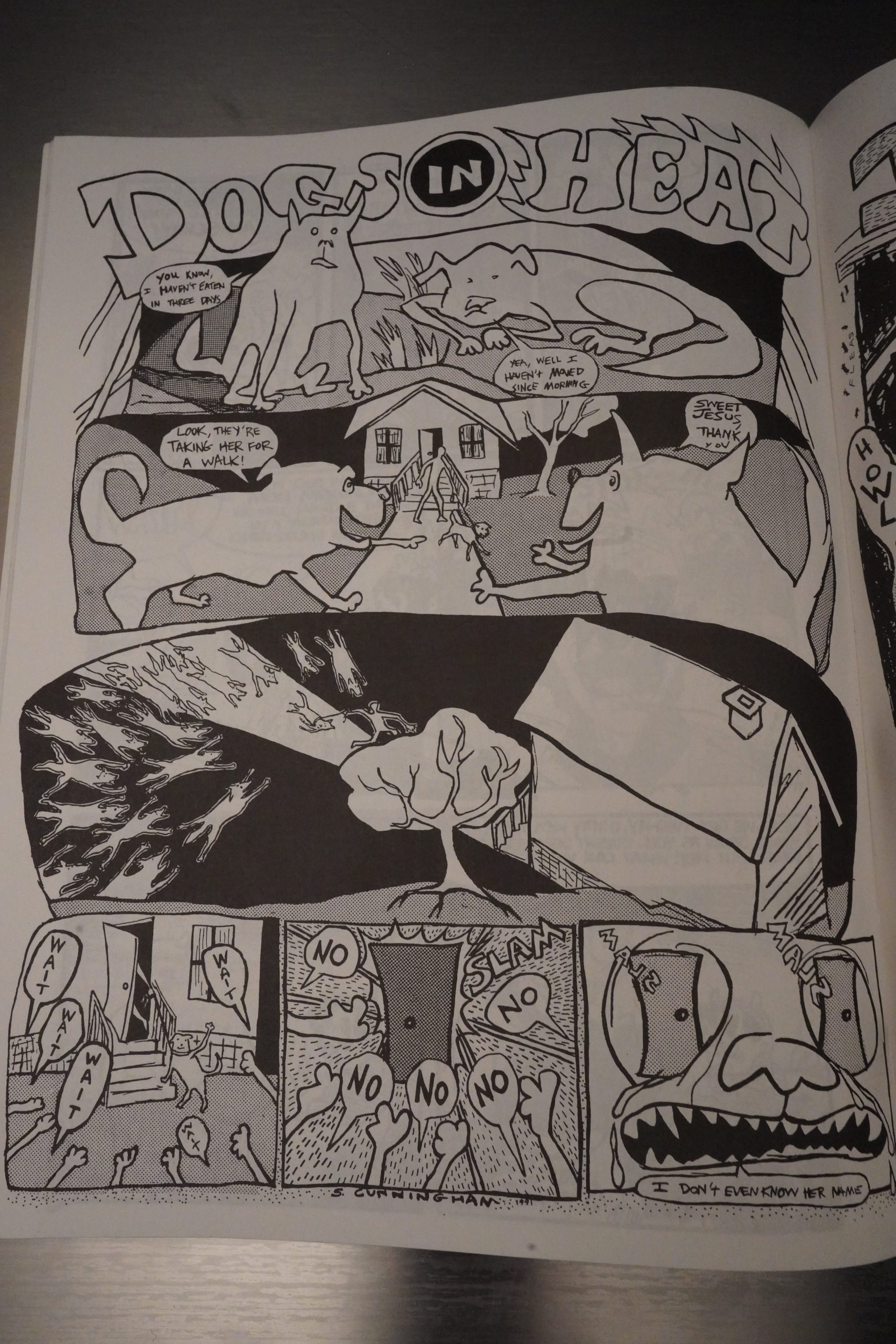

Allred follows that up with mad scientists, an invisible woman, time travel, robots, and dinosaurs. Those first two episodes are fast paced, fun, fun, fun and more fun. Then we have a road trip, but the dream sequences and psychedelic experiences of this final chapter are a more acquired taste. They’re still beautifully drawn, every panel a mind-expanding pop-art masterpiece, but for anyone wanting a little more story with their trippy hallucinations and chase scenes it might leave a little to be desired. In time Allred would learn to parcel out the real weirdness in smaller doses, and the strip would be better for it.

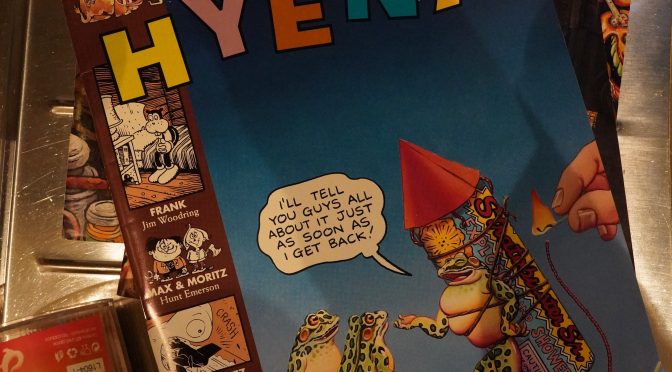

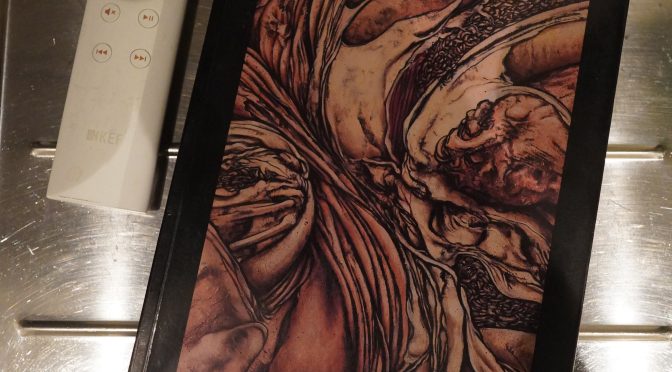

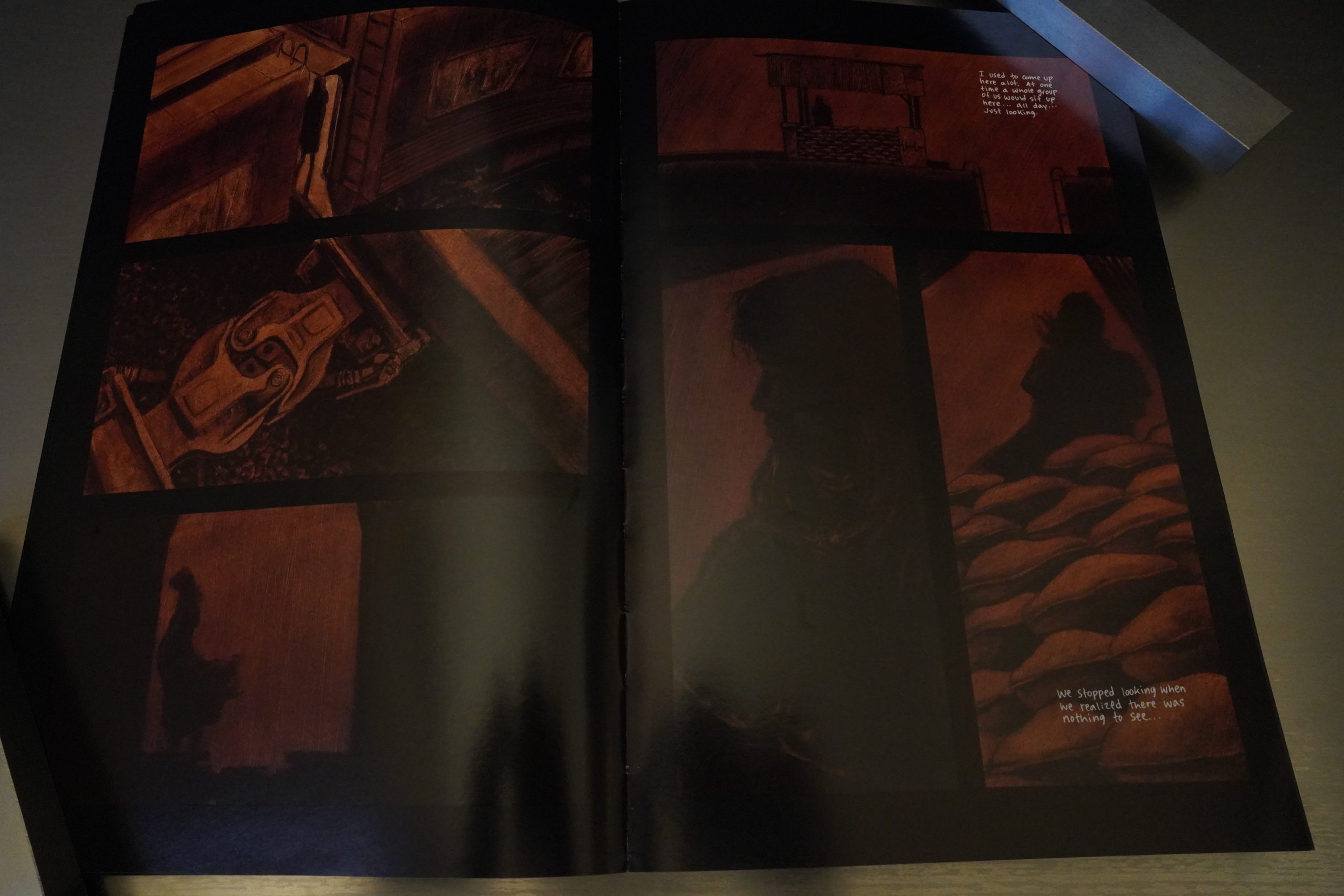

The Madman stuff has been reprinted many times, but as that page above mentions, it can be difficult sorting through all the different editions to find what you’re looking for.

This is the one hundred and fifty-first post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.