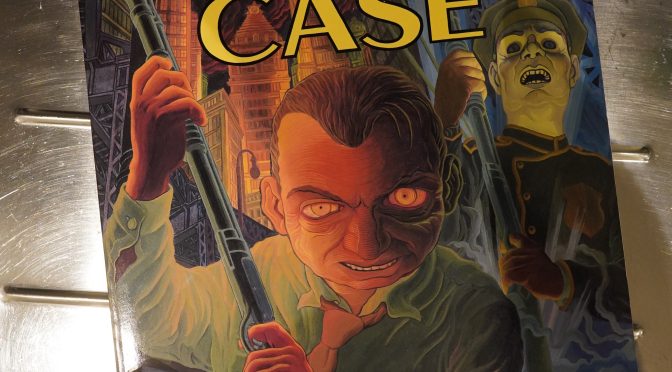

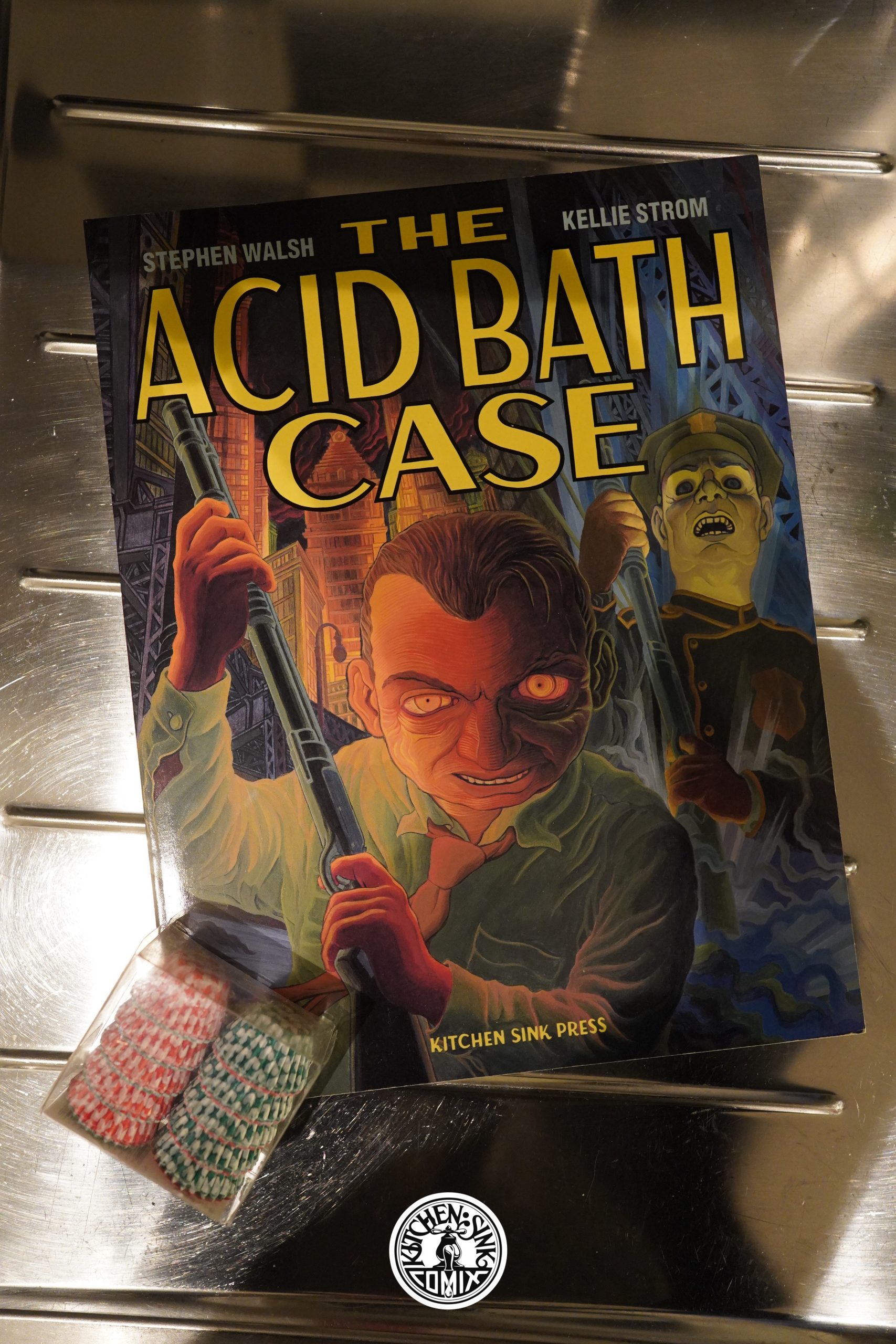

The Acid Bath Case (1992) by Stephen Walsh and Kellie Strom

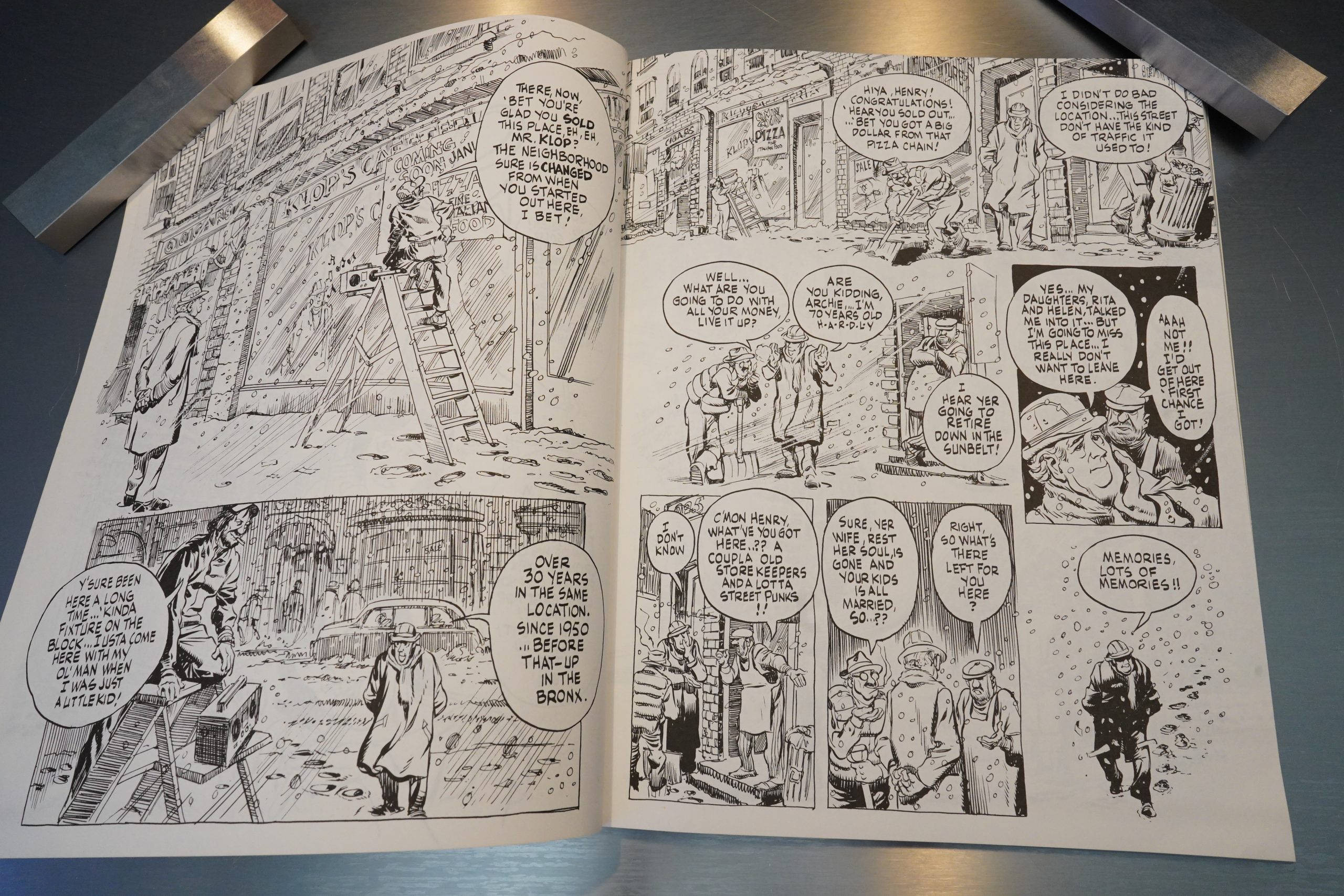

Kitchen Sink had a pretty strong identity as a publisher, even if it shifted over time. They started out as an Underground comix publisher, but a pretty mild one, and then segued into being a publisher that did quality reprints of superior genre material, while publishing books in the horror/fantasy/science fiction area.

But by 1992, you’d be hard-pressed to pinpoint a Kitchen Sink book any more.

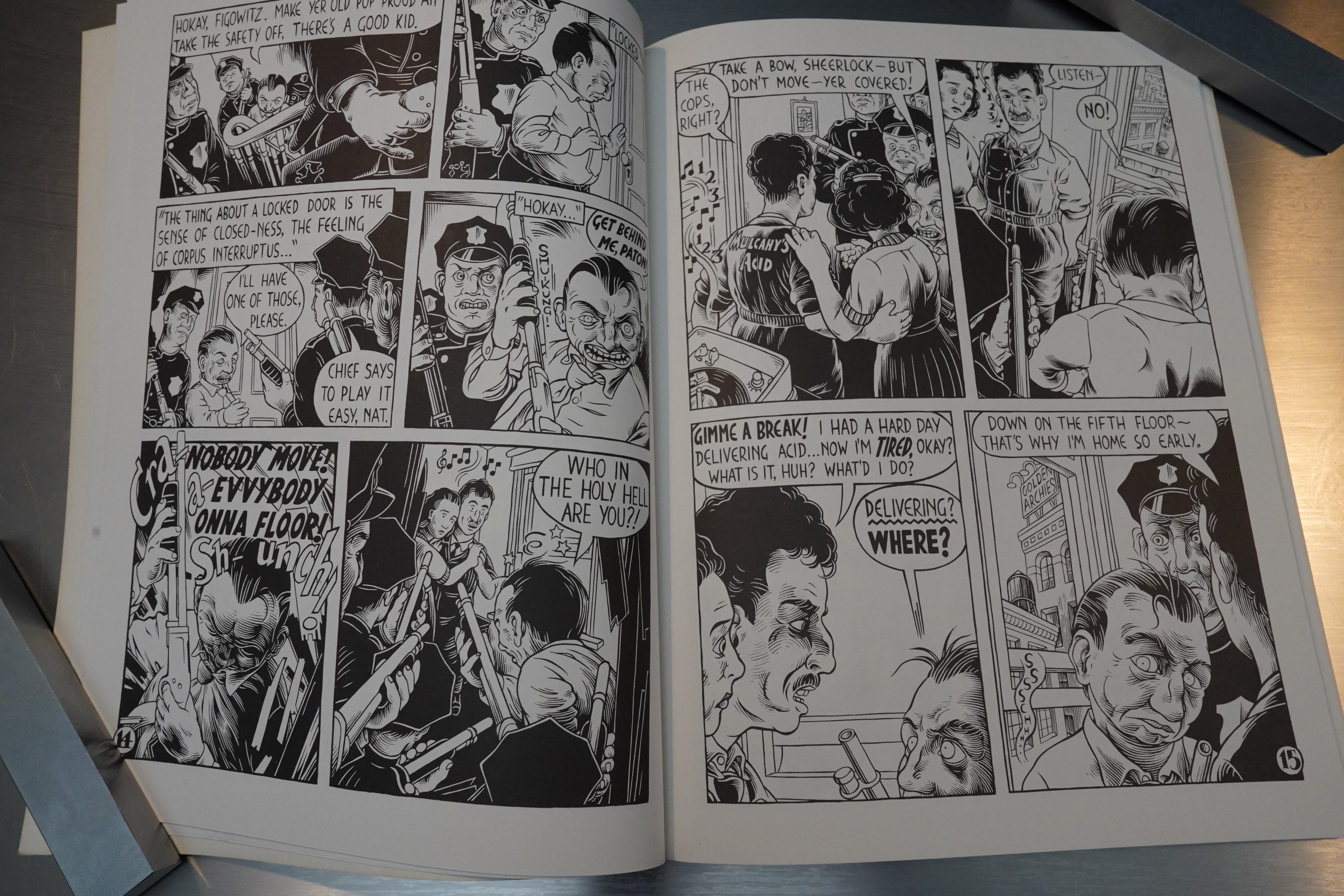

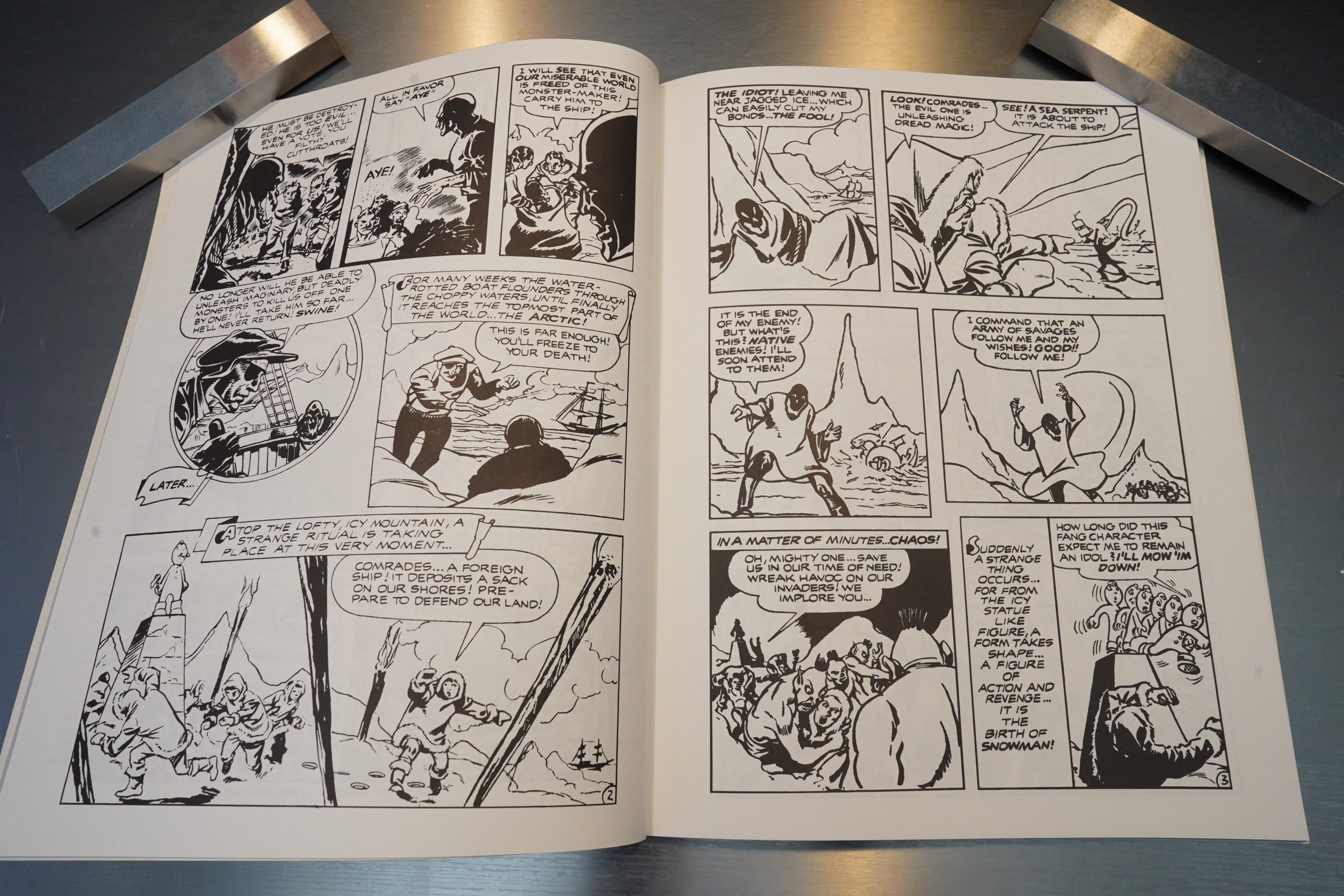

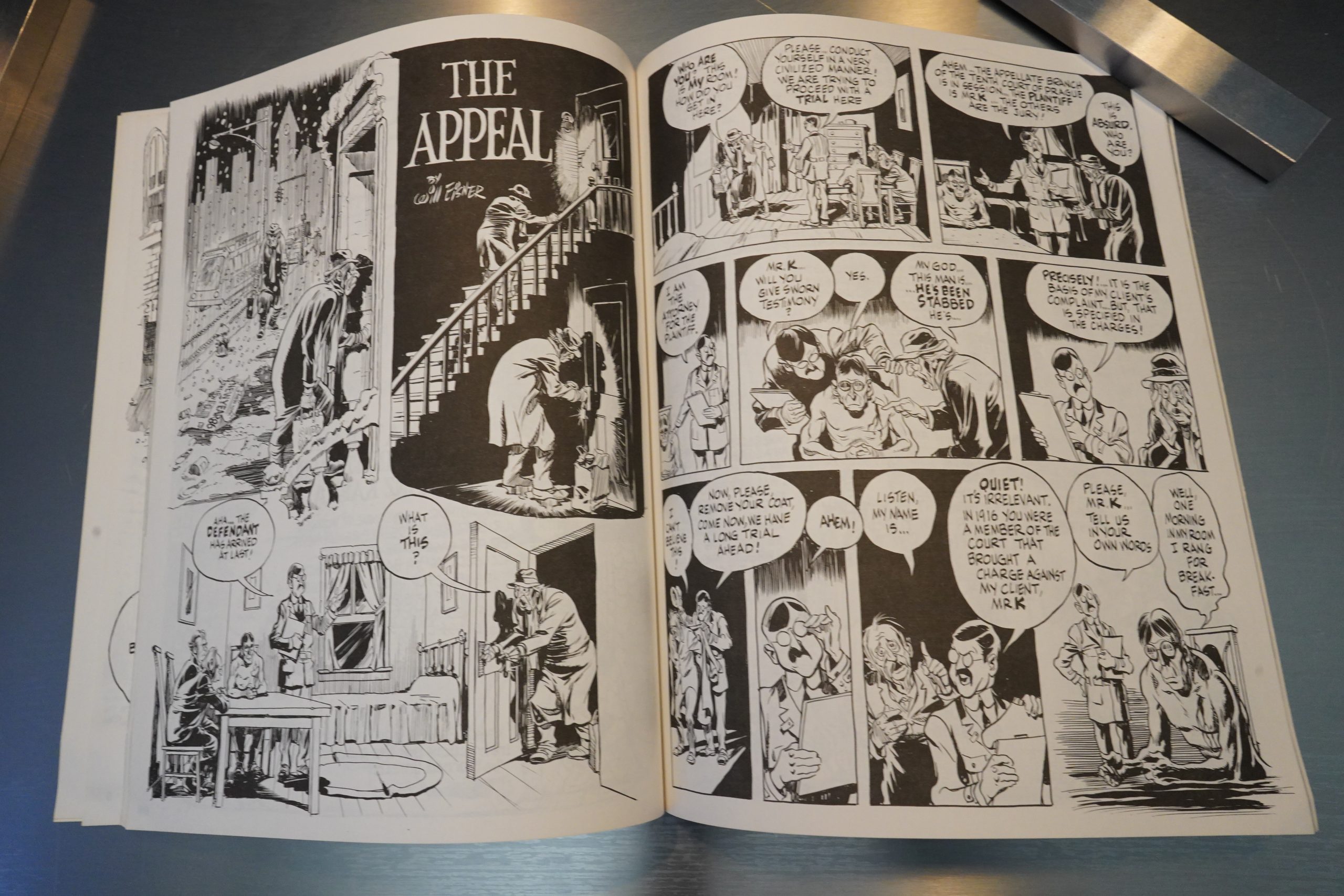

So what is this? I guess you can see the connection to, say, Blab — this is a hard-boiled noir 50s thing, but with an art style that’s totally unlike what the Blab people are going for.

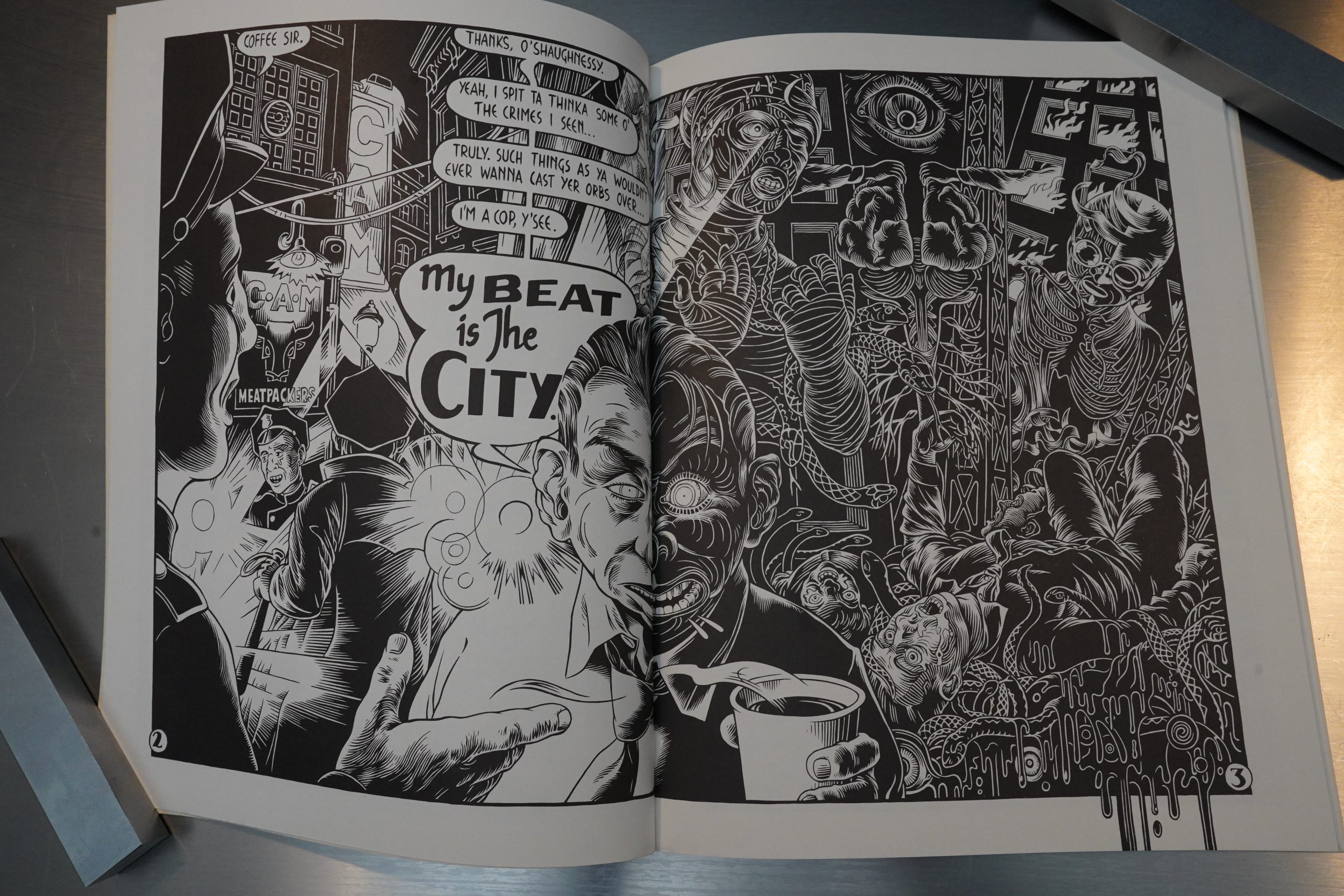

It’s also just… a befuddling reading experience. My guess is that the creators here have no comics experience, so it’s hard to interpret what we’re even supposed to glean from a sequence like the one above. Why is he grabbing the steering wheel?

I like reading comics that don’t explain too much, but this book was just incomprehensible.

I think… the plot is that Eisenhower is going around killing people and then dissolving them in acid? I’m probably wrong. 🤷🏾♂️

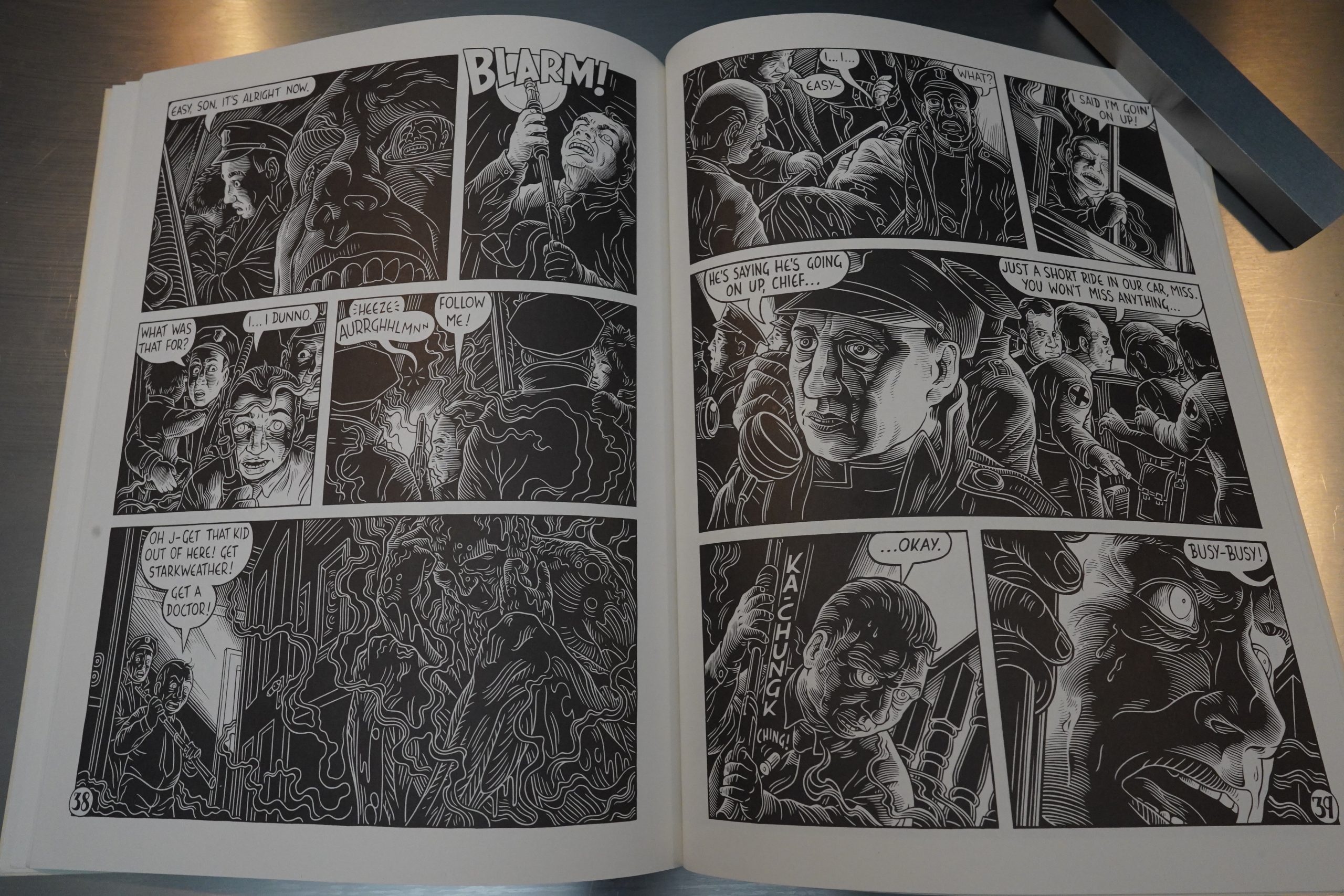

The artwork is sometimes pretty stunning, though, so it’s worth reading for that alone.

The Comics Journal #157, page 123:

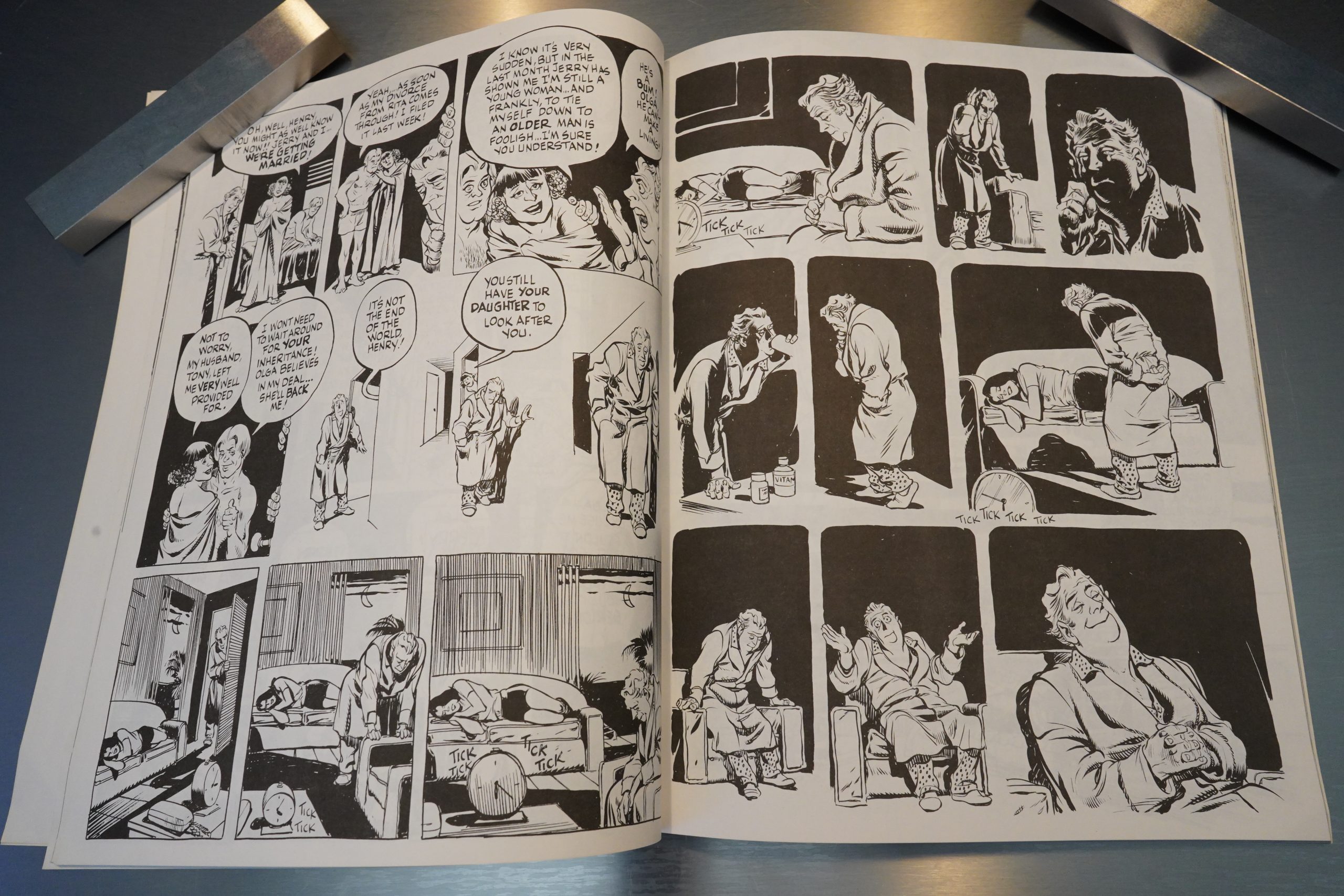

This 46-page trade palxrback is a mystery/hard-t»iled

detective story involving an upper echelon police

detective in pursuit of an urban serial killer whose

modus operendi is death by industrial acid. The vivid

imagery of coiled skin corpses, skulls with protruding

eyeballs. and ribbons Of sinister fumes arising from

victims are Strong enough to turn even the steeliest

of stornachs. The artuork is painfully effective in

the horror am! obscenity of the murder scenes.

The visual composition is complex and engaging, as

is the actual drawing style. This could compared

to a film noiron paper. It is lurid and macabre, with

a sharp. urban look to it. The portrayal of the main

character, Nat Slimmer, doesn’t come across as be-

ing very likeable mostly due to the fact that the writer

leans too heavily on genre cliches, i.e., Nat’s self in-

tru: “l spit thinka some o’ the crimes I seen.. .Truly

such things as yu uouldn’t ever wanna cast yer orbs

Over. I’m a cop, y%ee. My beat is the city.” This

writing style may be a bit of a hurdle to those who

donh favor the hard-boiled school ofdialogue, but the

odd and intricate plot combined with the lush and

ferocious illustration make this tx»k uell worth a

This is the one hundred and thirty-fifth post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.