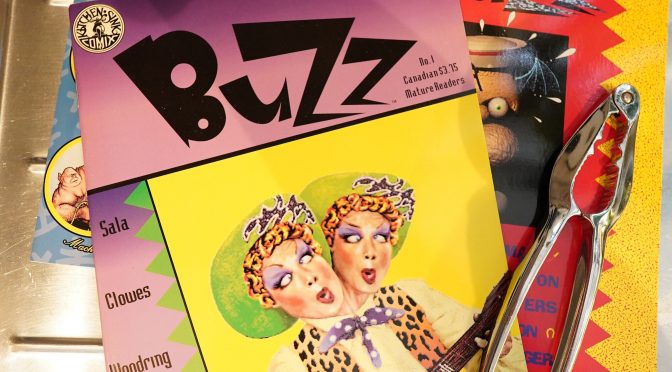

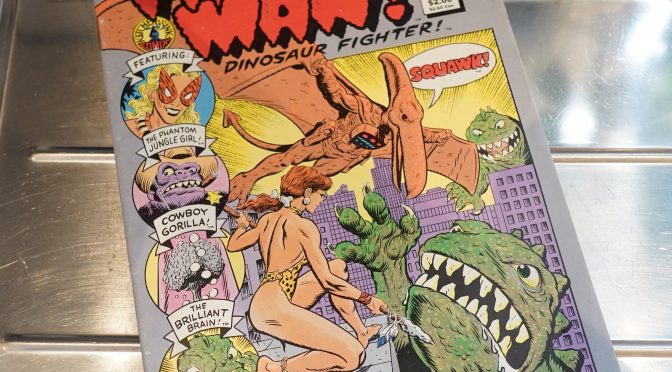

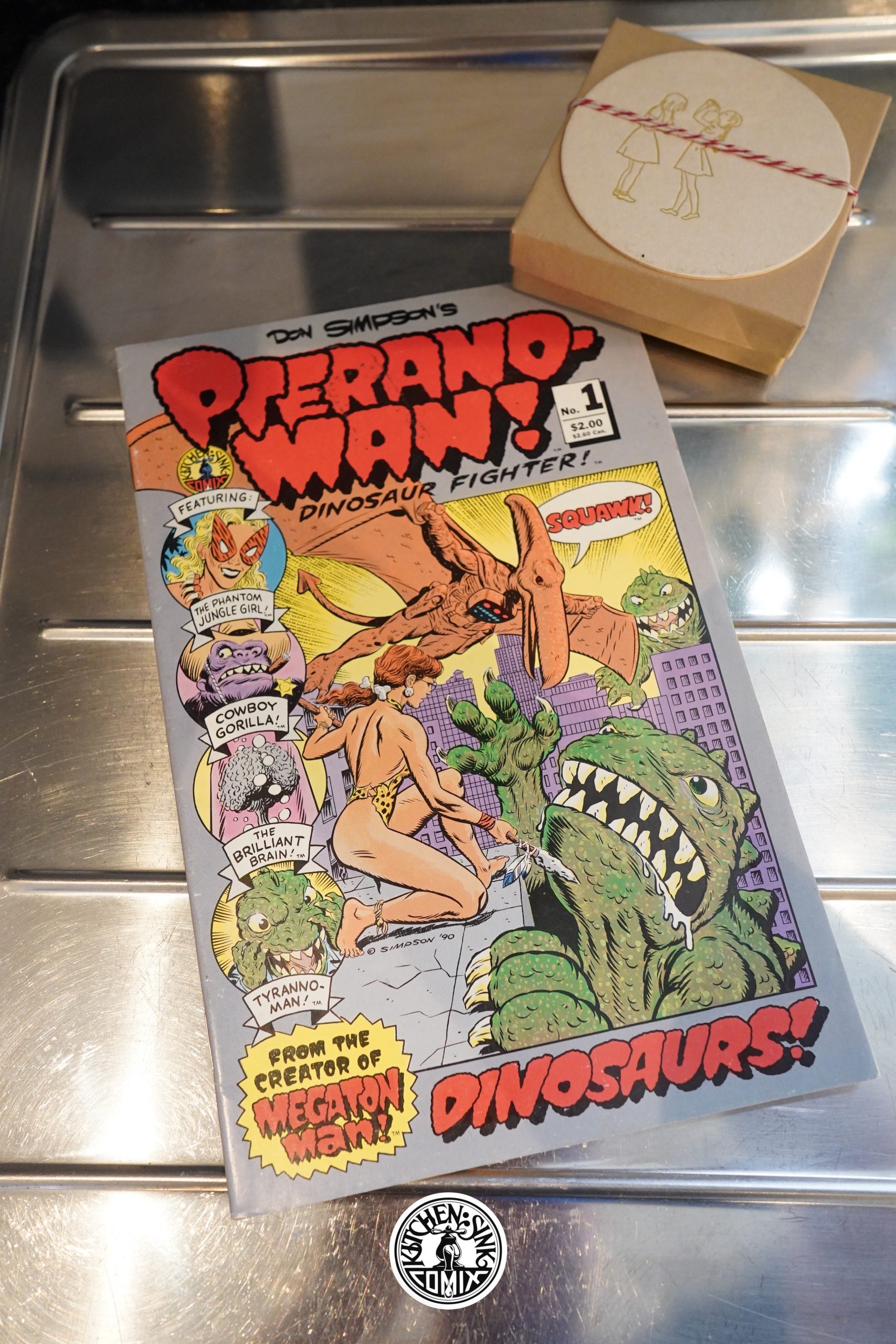

Buzz (1990) #1-3 edited by Mark Landman

I wonder whether anybody’s done any research into the phenomenon of artists starting anthologies just because there’s nowhere to be published otherwise? It’s a quite common phenomenon in music circles: You have musicians that don’t get booked all that much, and then they decide to throw a festival or two to have places to play. (And then again, there are musicians that are in huge demand that do the same.)

Editor Landman (who also did all the covers) places the book explicitly in the Weirdo tradition.

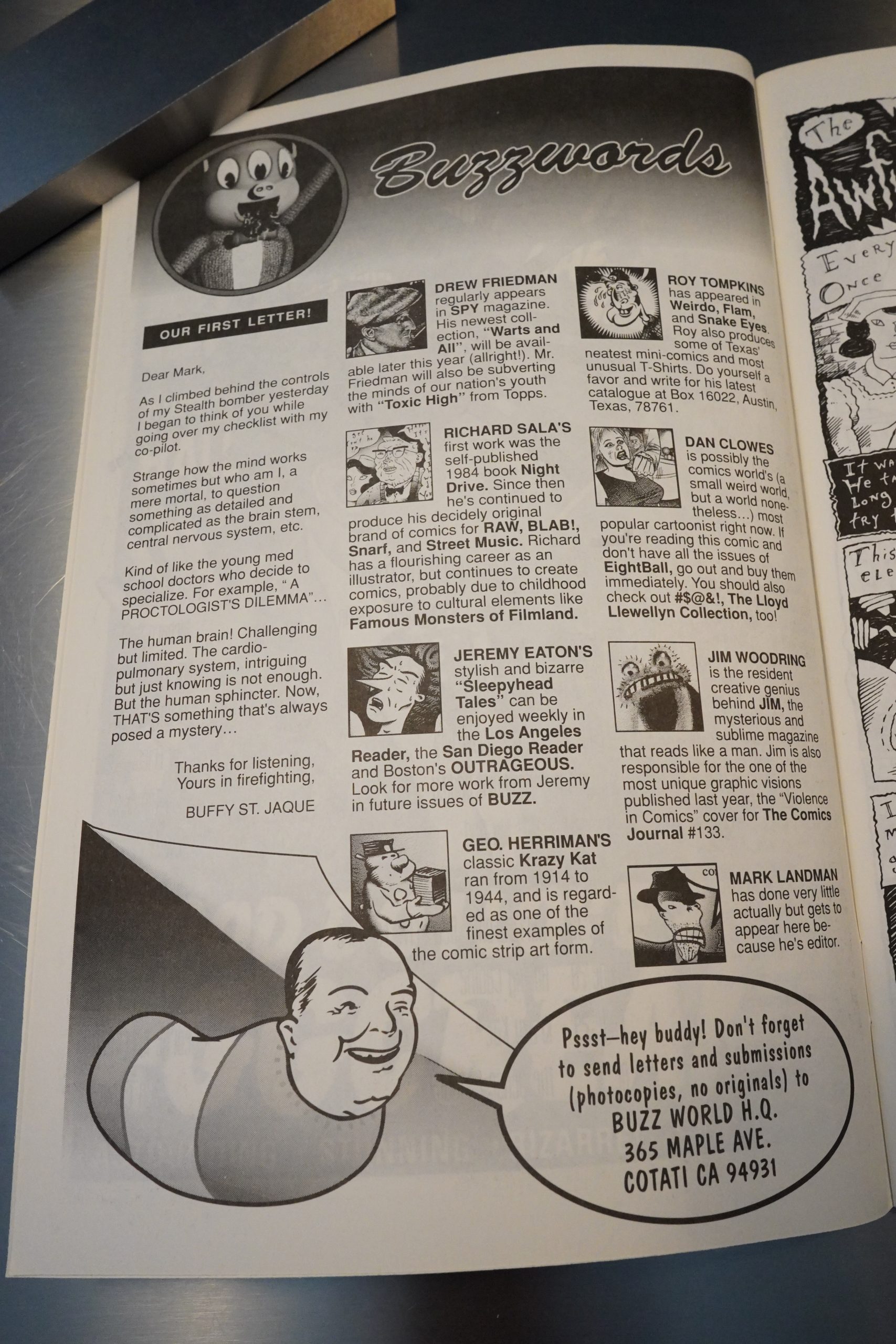

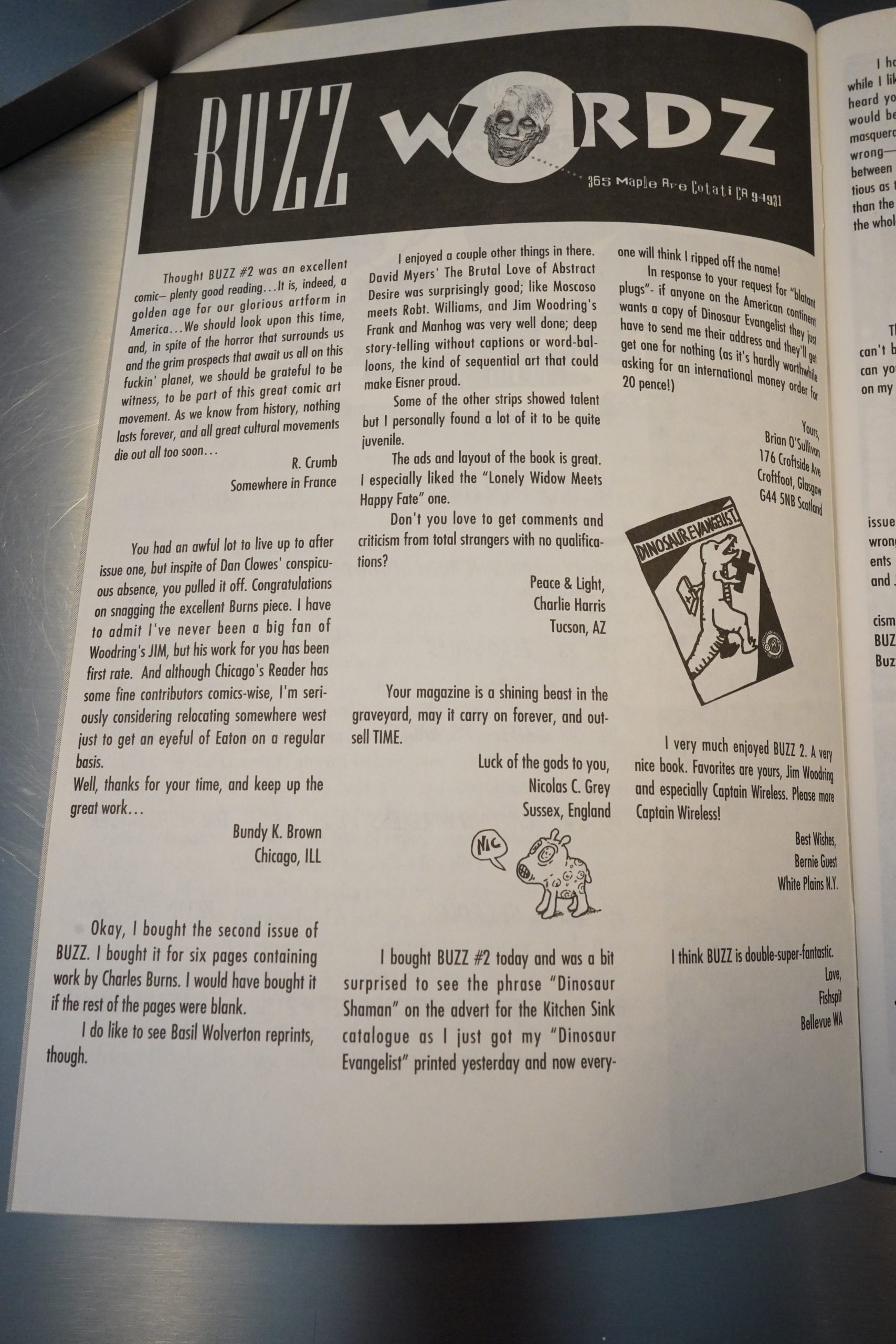

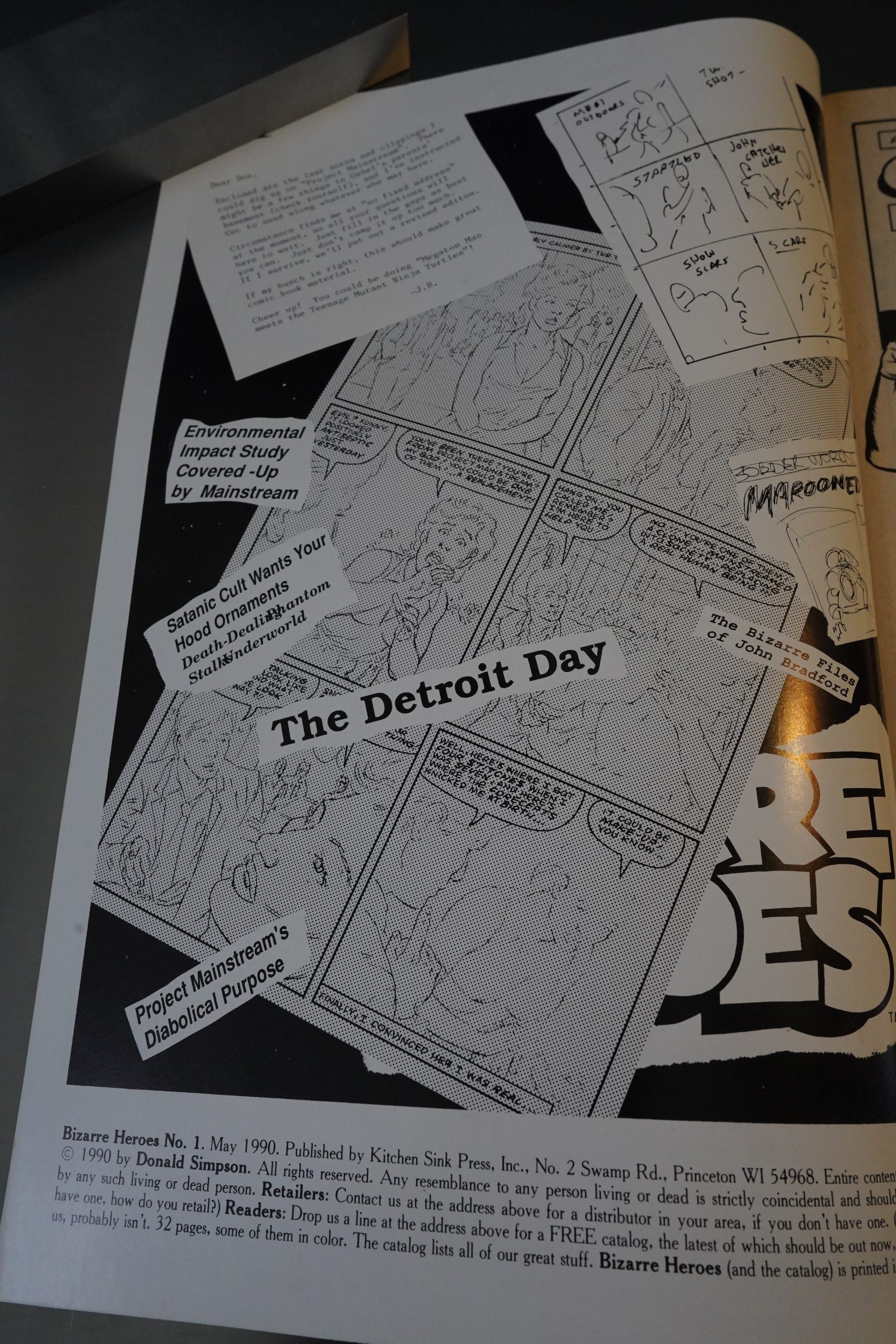

Landman is famous for being a comics artists that pioneered working with computers, and that leaks out to the design of editorial pages, too. Everything looks very desktop publishing 1990. Not that there’s anything wrong with that — it’s an aesthetic I find quite appealing.

(And also note that the book is a total sausage fest.)

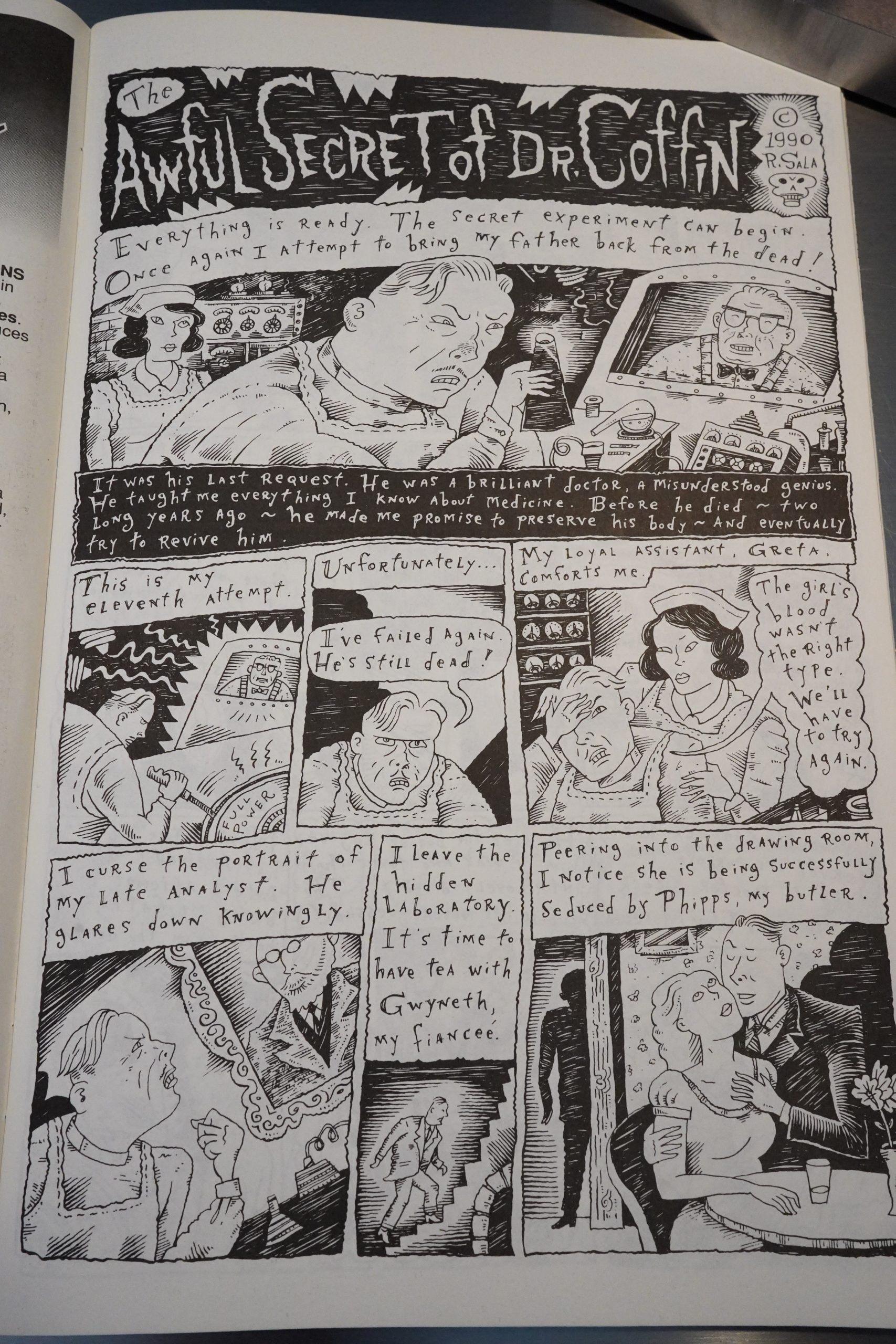

I’m happy to see that Landman adheres to The Richard Sala Act of 1989, where Congress voted unanimously to require that all anthologies have at least one piece from Richard Sala. And I love this period — the artwork is just so deliciously unhinged, with panels that definitely aren’t drawn using a ruler, and that perfect lettering.

It’s just so gorgeous to look at.

And this is a pretty good story, too. It has that improvised feeling, but also resolves itself nicely.

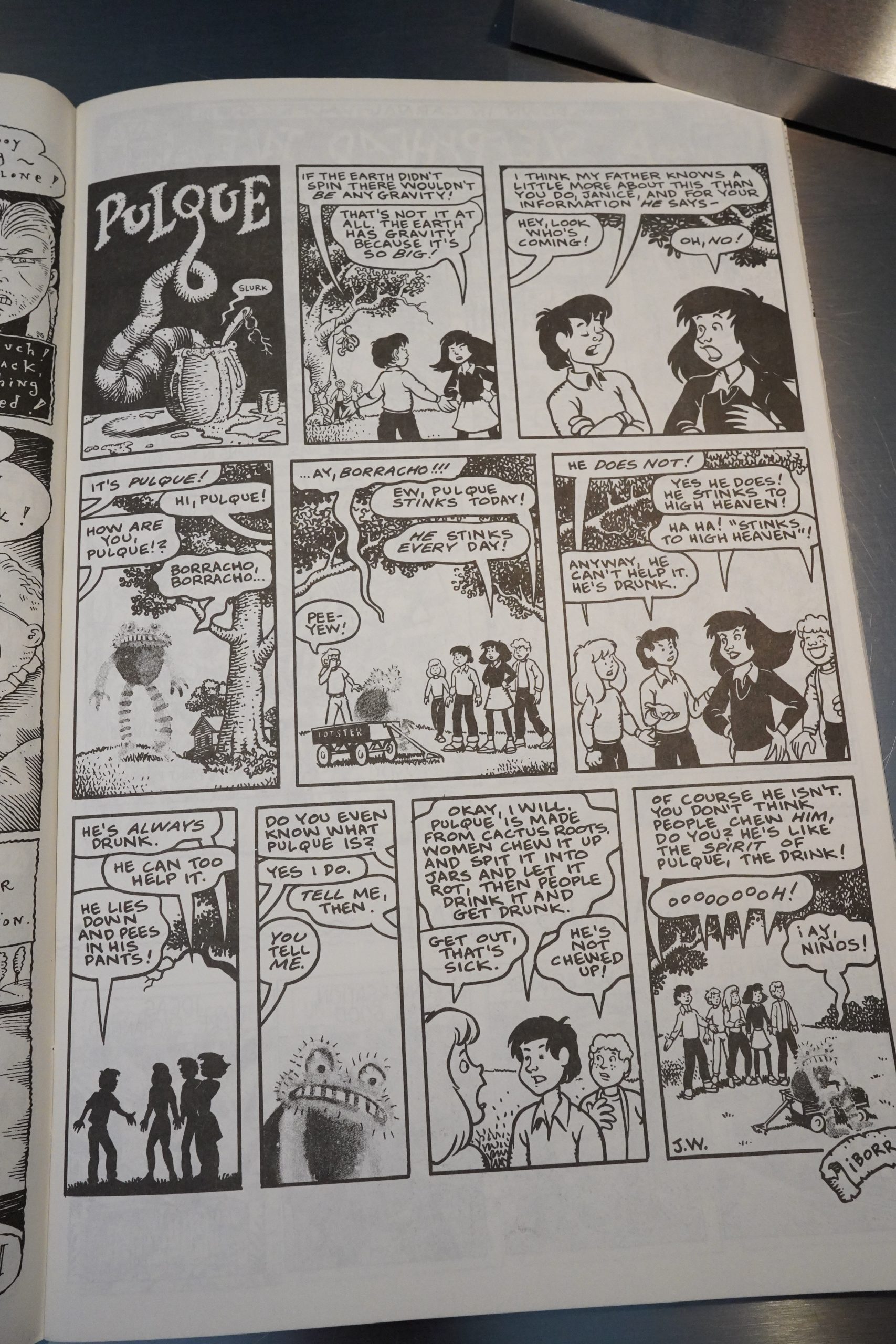

Jim Woodring!!! Just perfect.

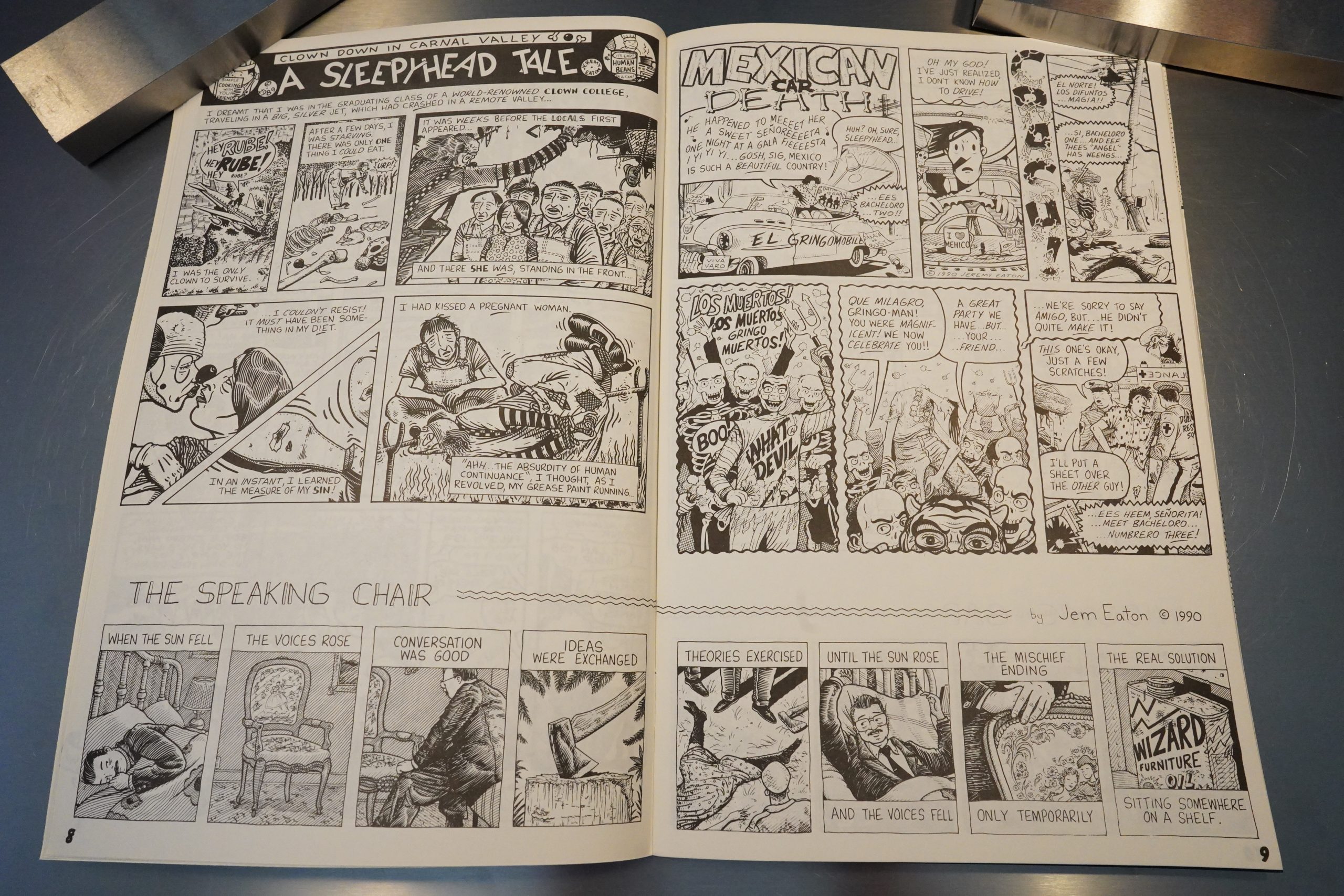

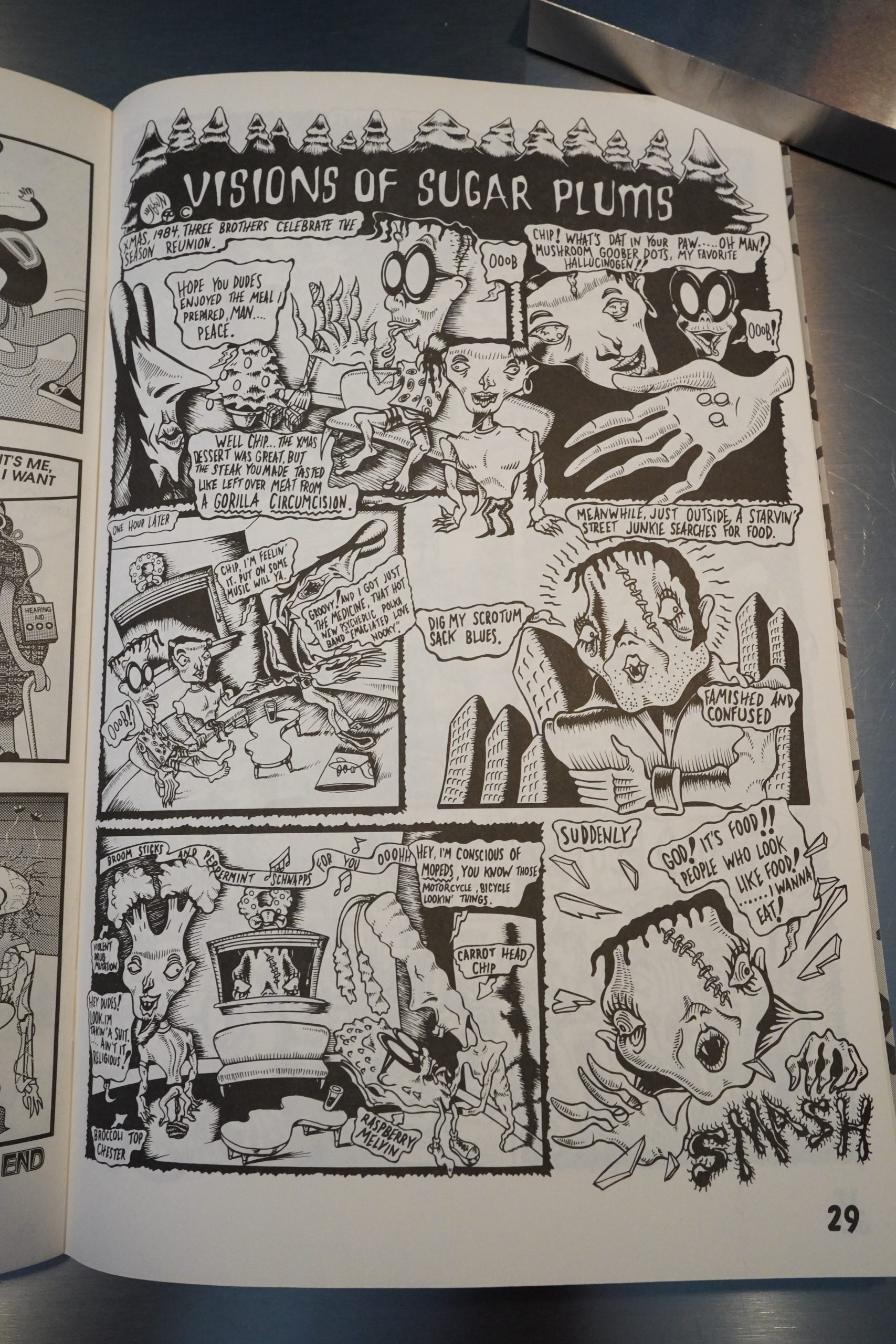

Early work from Jeremy Eaton — I think he’s going for a dream-like logic, but it’s a bit strained.

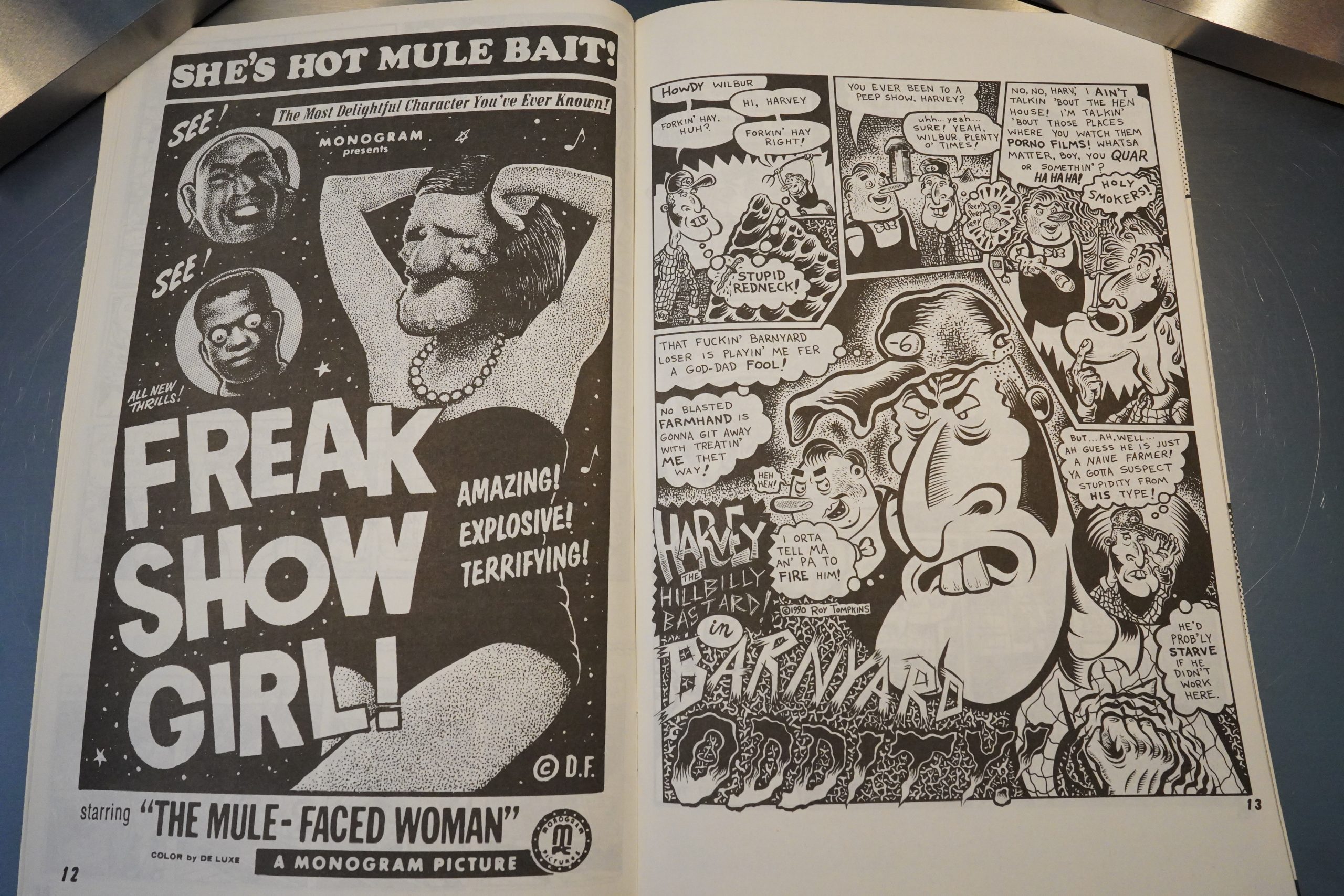

There’s a couple of artists that are more aligned with the Raw crowd, like Drew Feldman to the left here, but I’d say that most of the artists are third wave underground artists, like Roy Tomkins to the right here. Fantagraphics would take over publishing all these people later, I think?

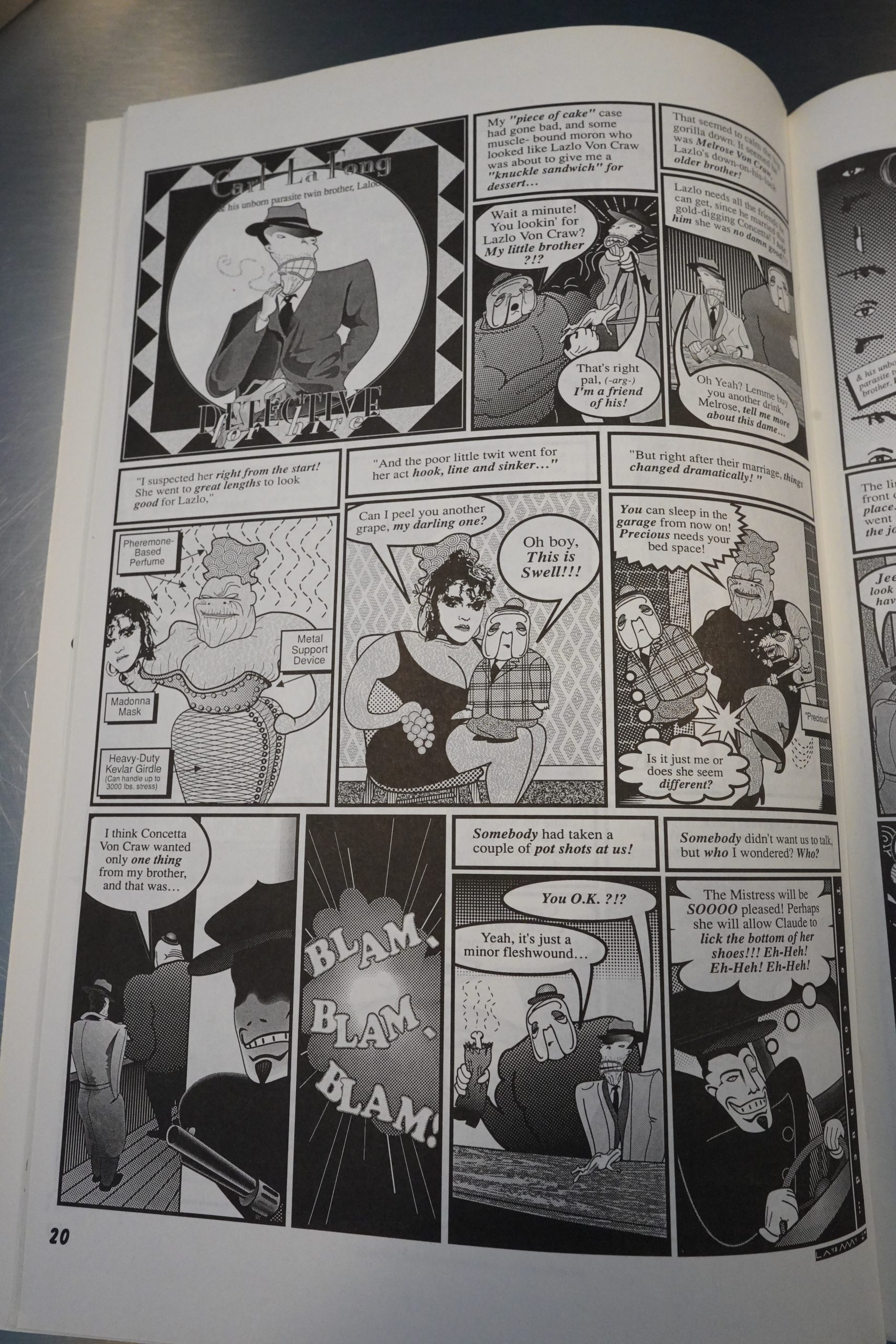

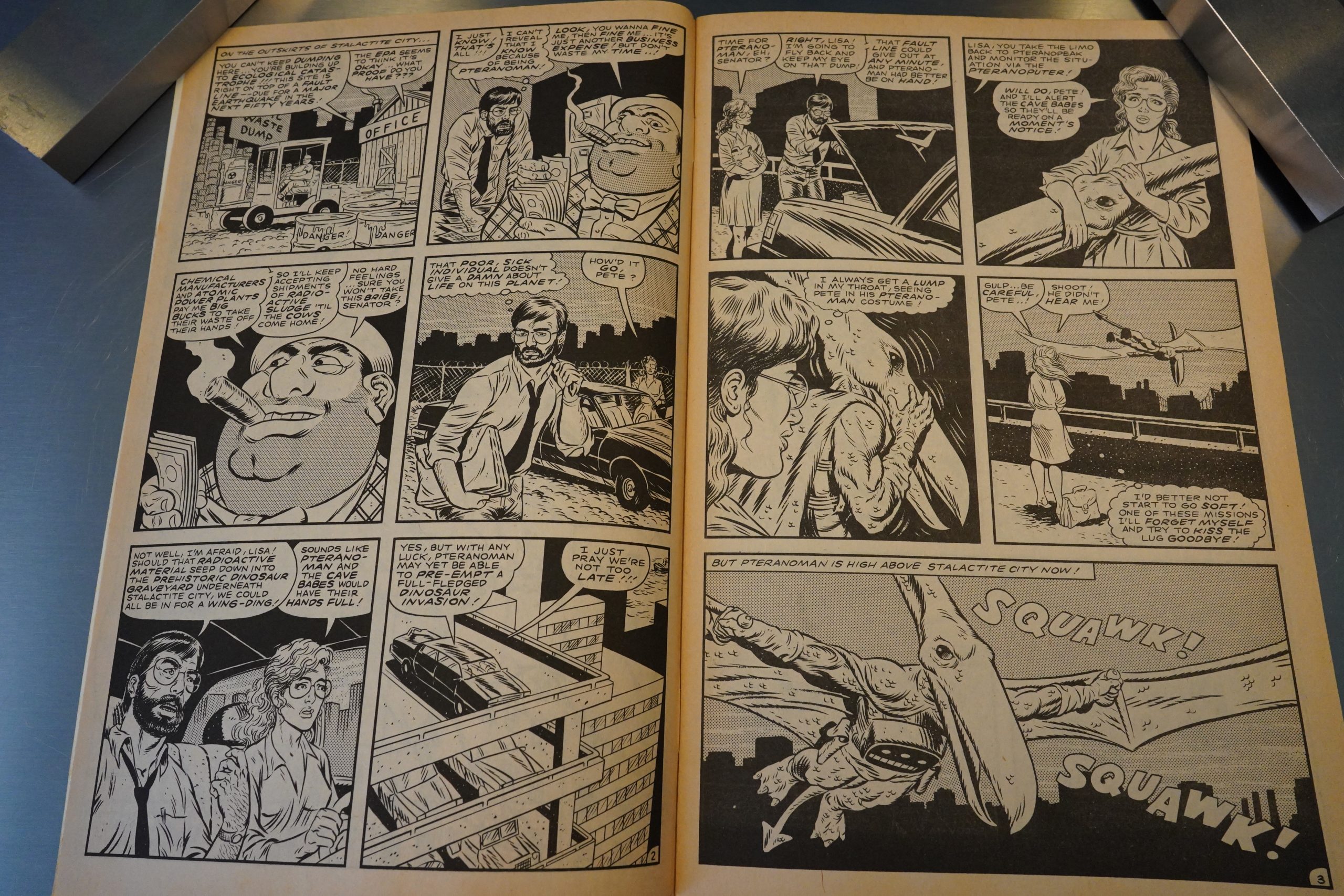

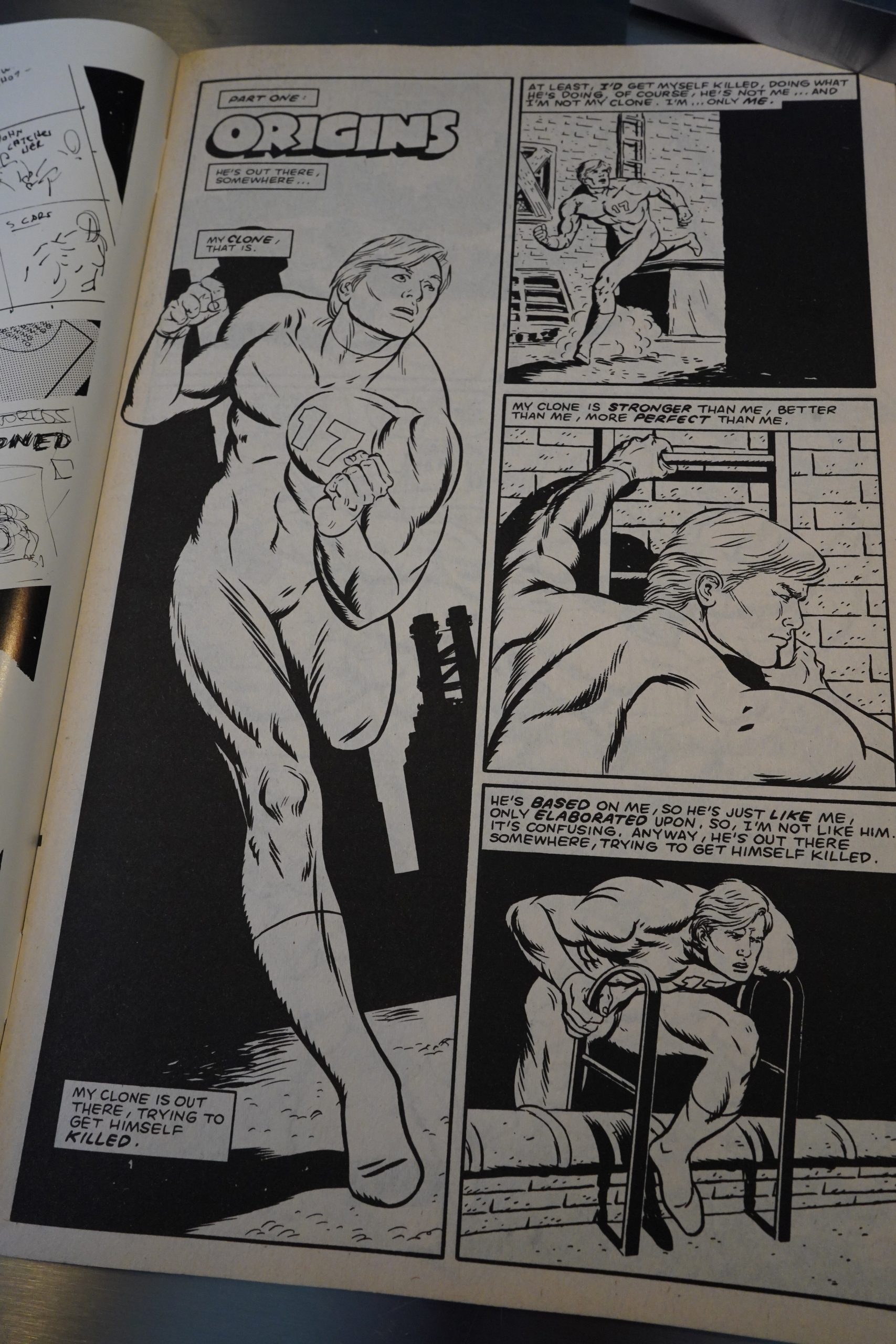

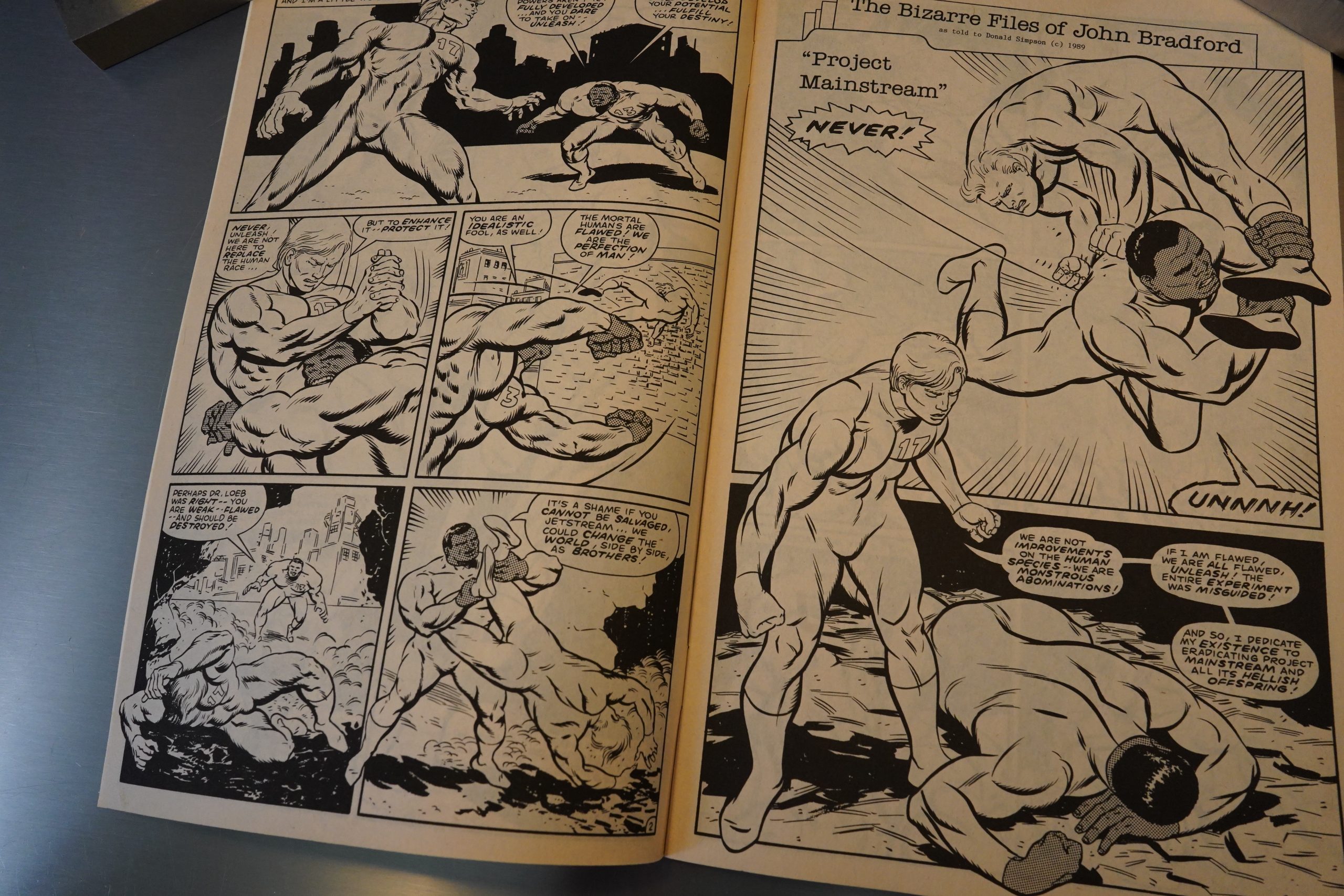

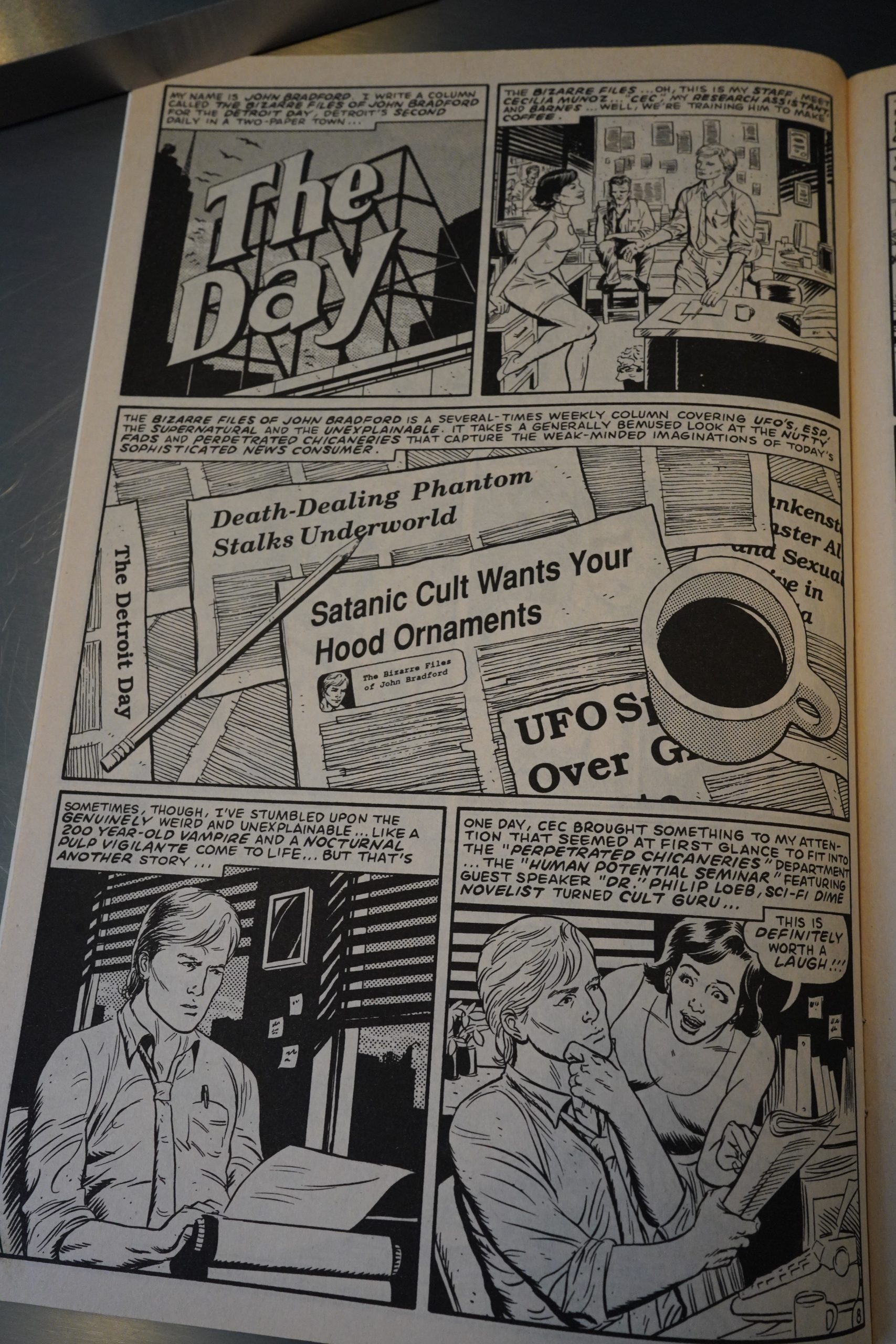

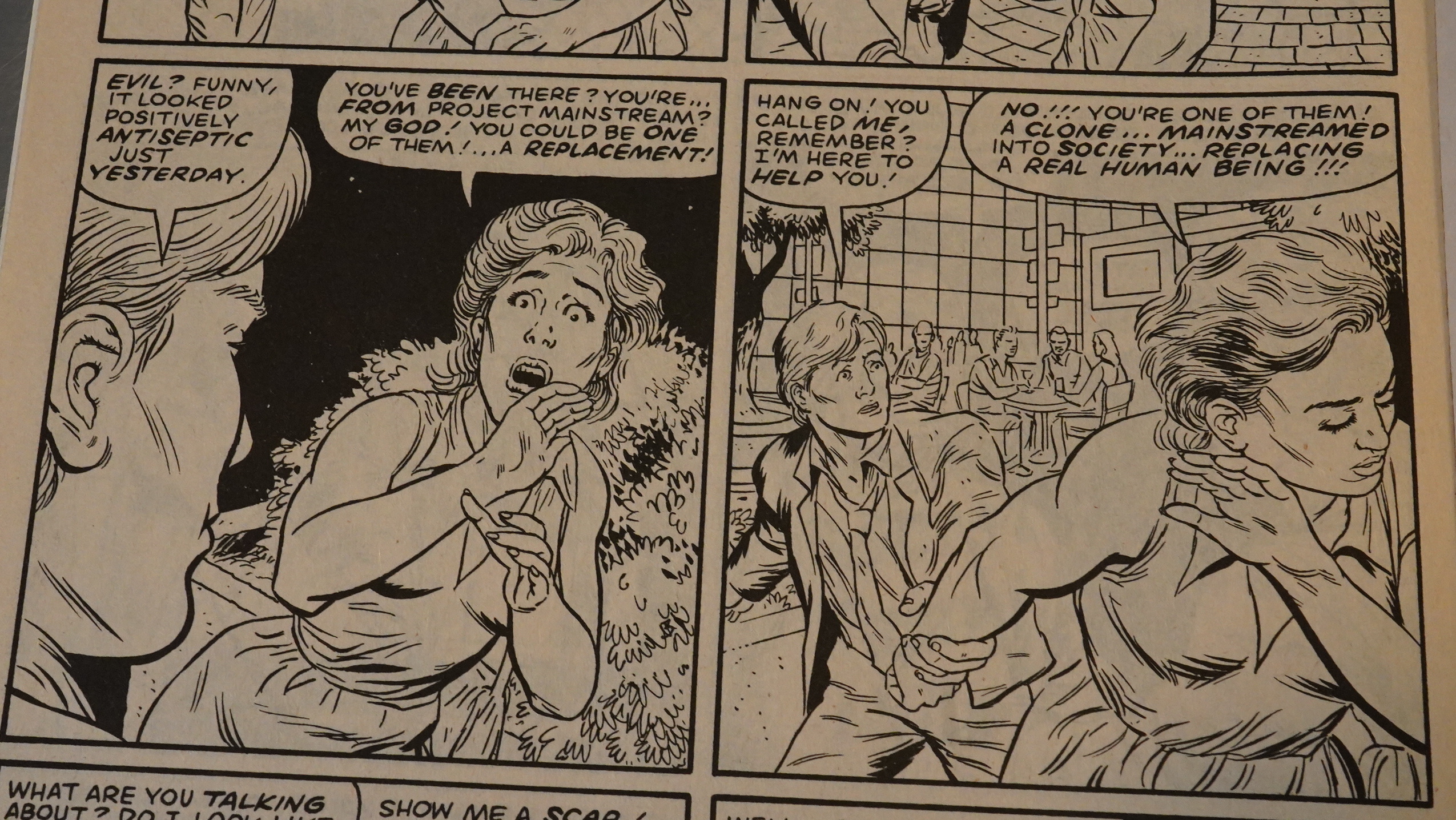

The longest story (almost a third of the first issue) is by Landman himself. It’s an amusing neo noir parody/homage, and the computer-assisted graphics are pretty interesting.

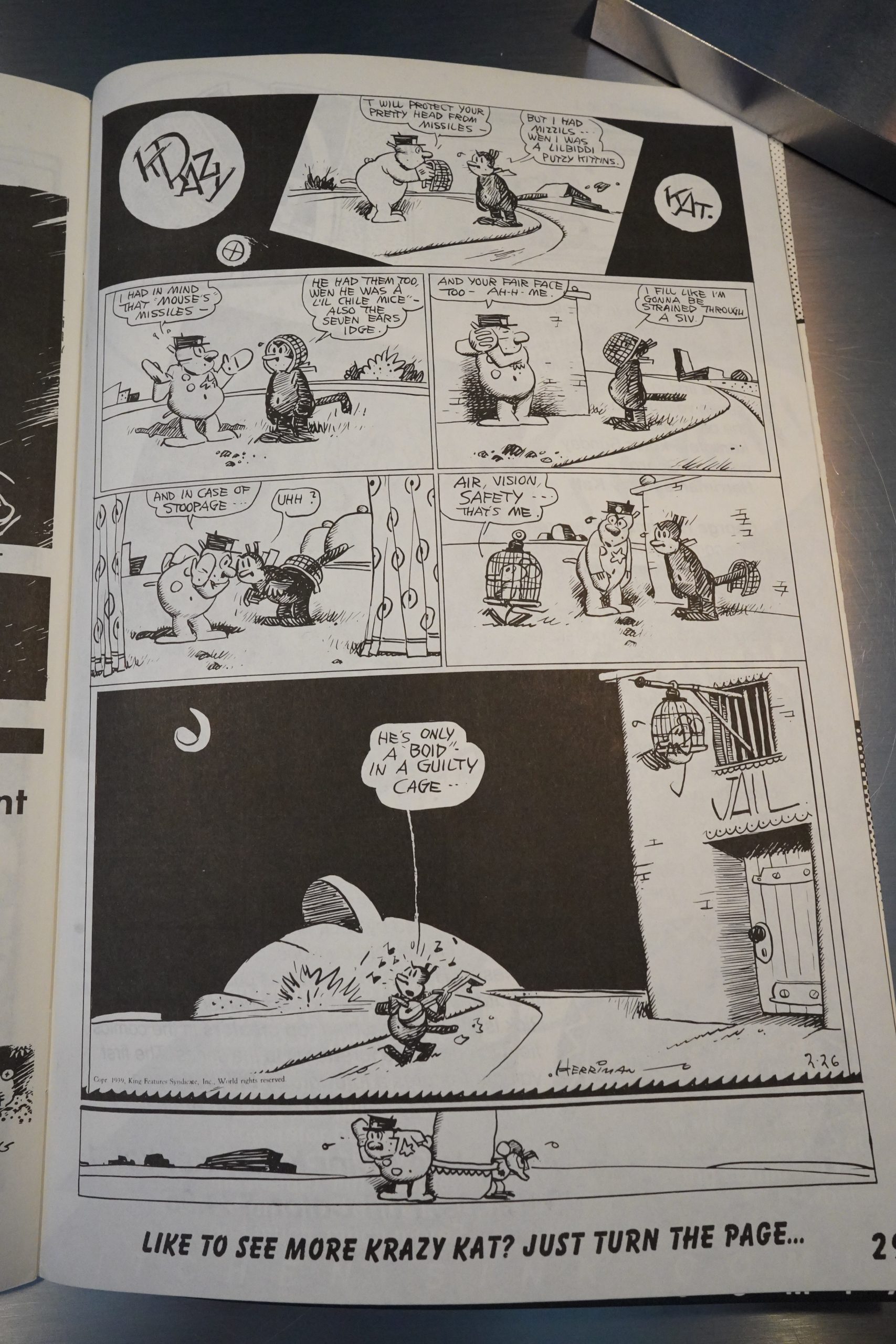

And you can’t do an anthology like this without Krazy Kat.

So — first issue is a really strong start. There are no duds here, and it just has great flow for an anthology — a mix of shorter and longer pieces, and different approaches without being incoherent.

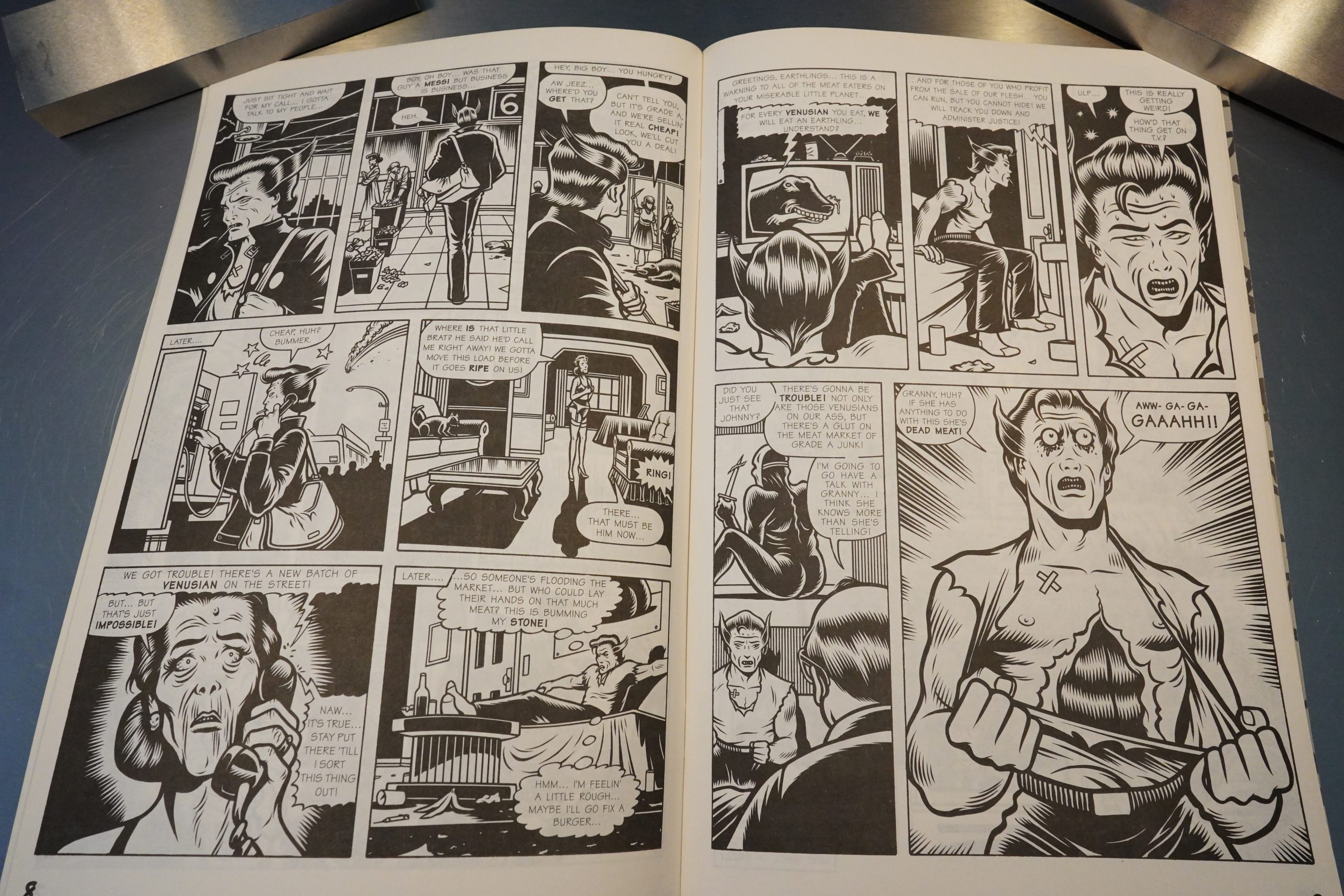

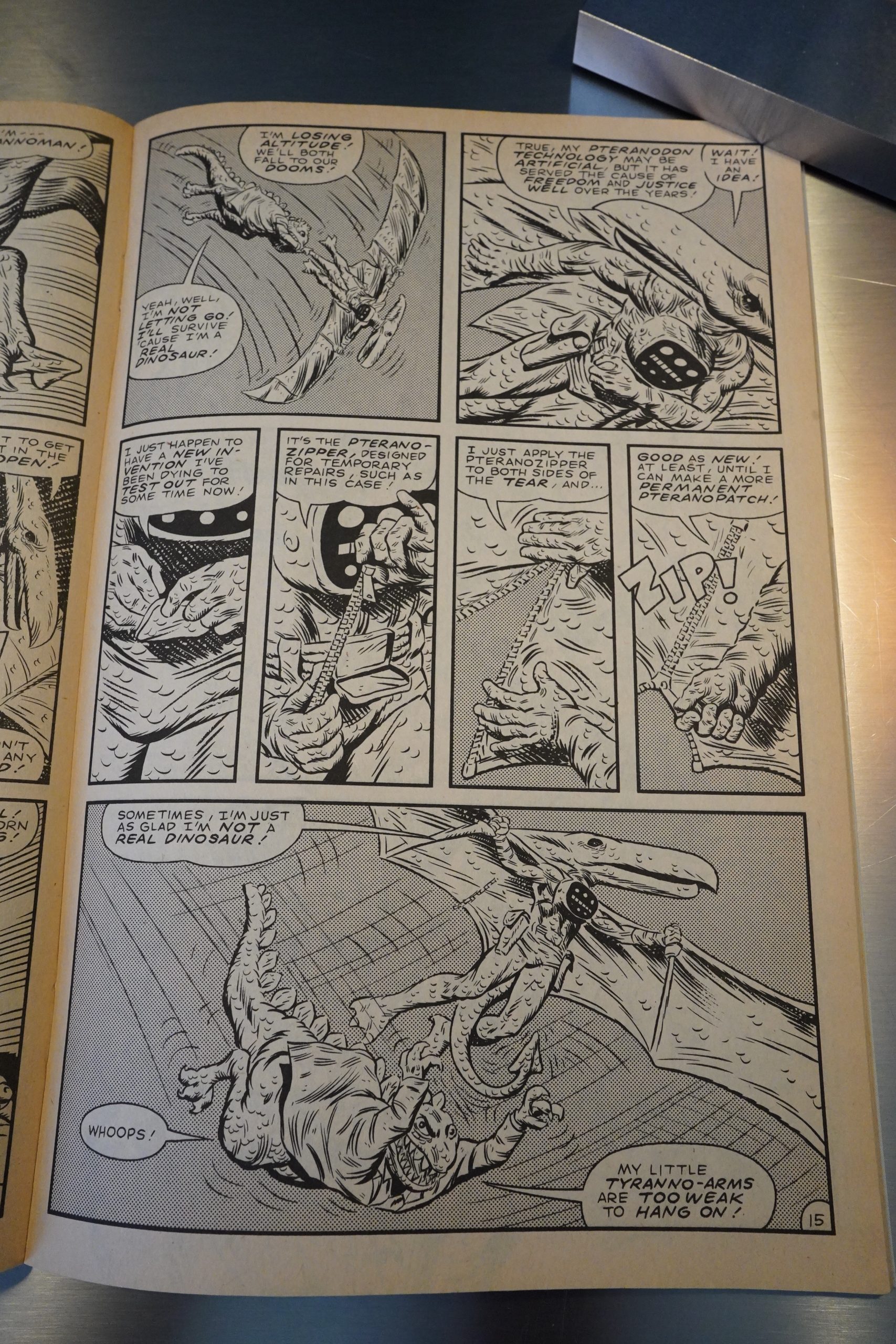

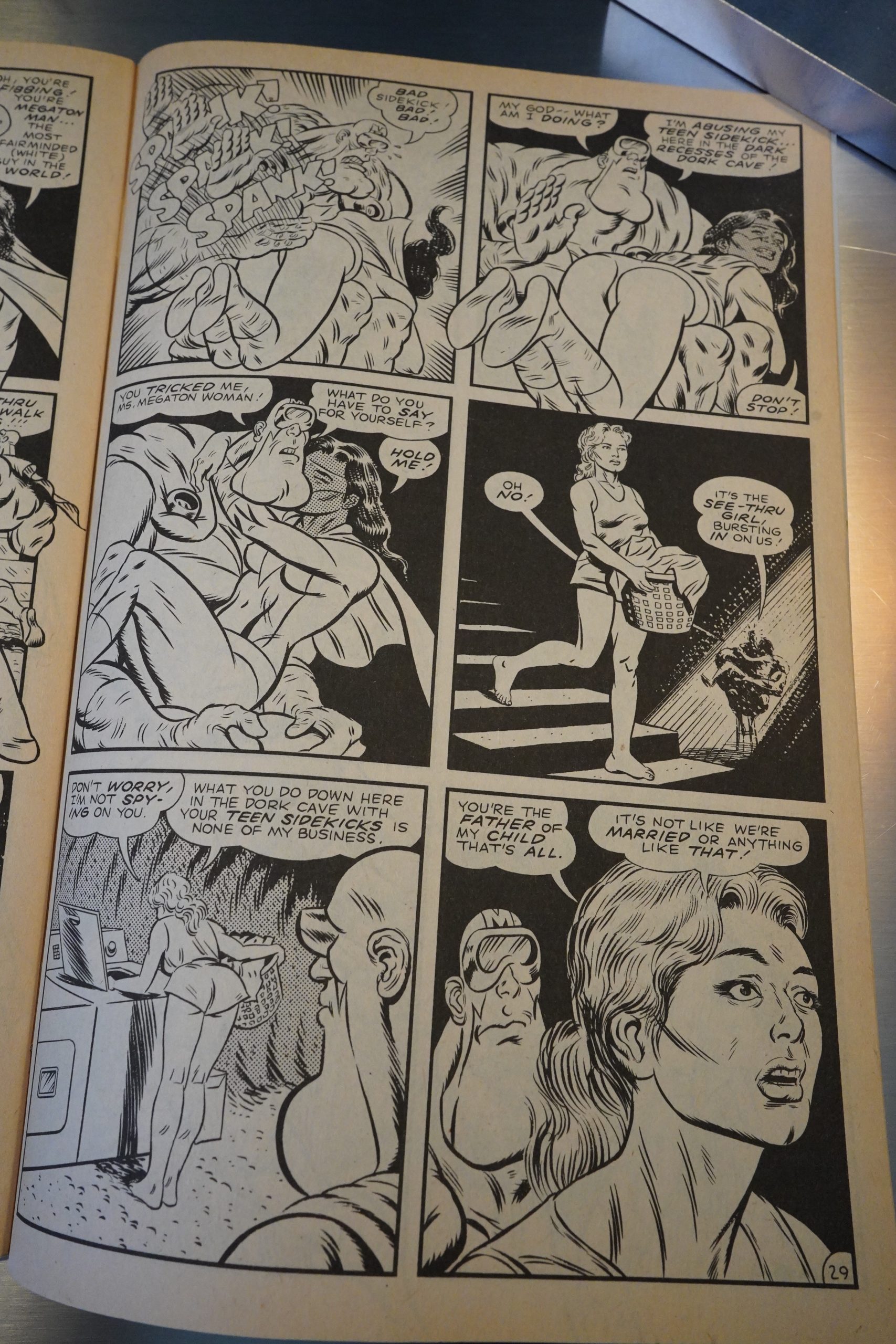

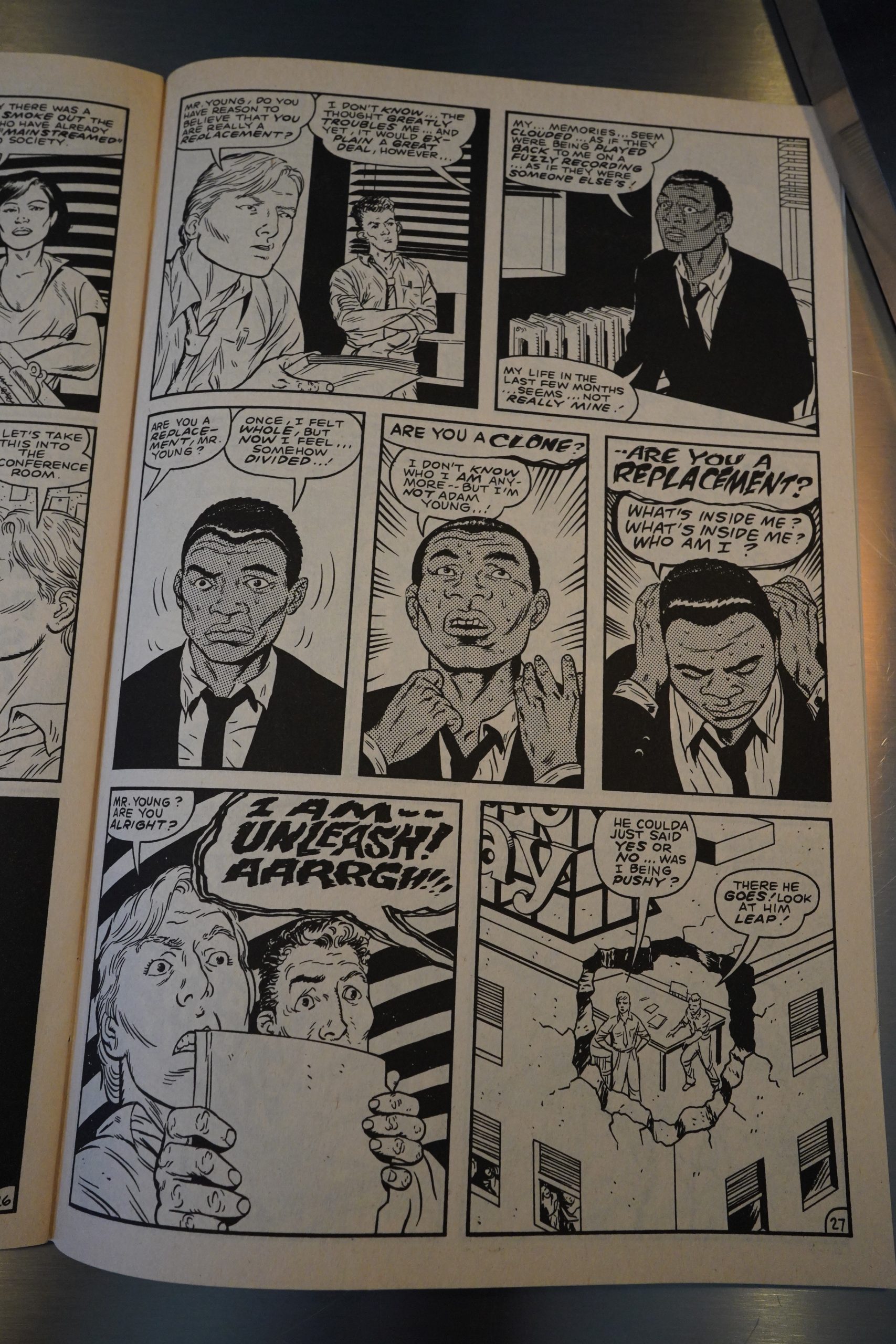

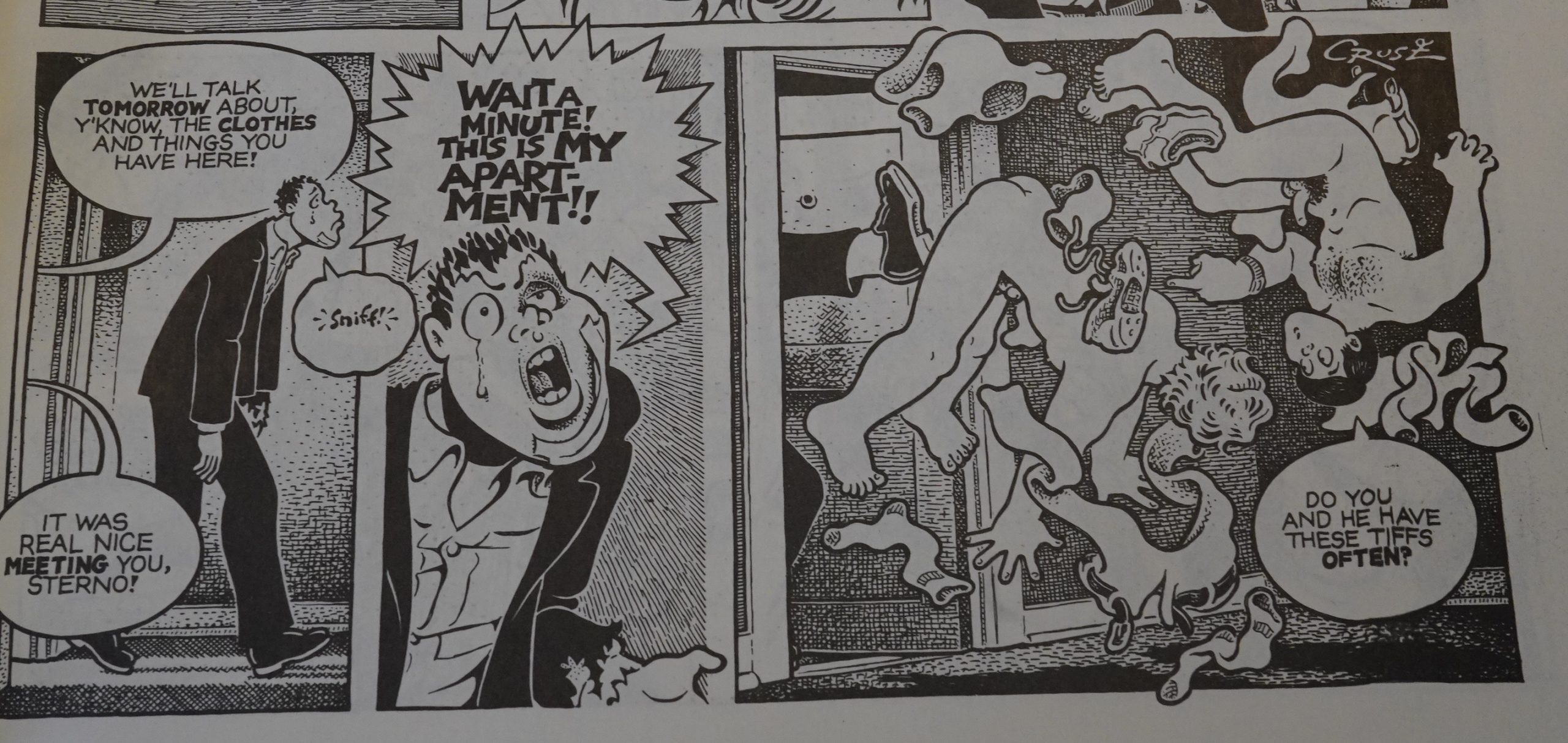

A Charles Burns story, Naked Snack, is serialised over the next two issues. The artwork is insanely awesome, and the story is just… insane? But rather unpleasant. And not in the usual Charles Burns way.

It’s apparently put together from Official Marvel Comics Try-Out Book — this is Peter Parker, really, and explains how unhinged it is.

I don’t think this is something that has been included in Burns’ collections? I can see why — it’s a fun exercise, but perhaps something that Burns wouldn’t necessarily want to have seen in a wider audience? (It ends with Peter Parker killing and eating his aunt, but not in that order.)

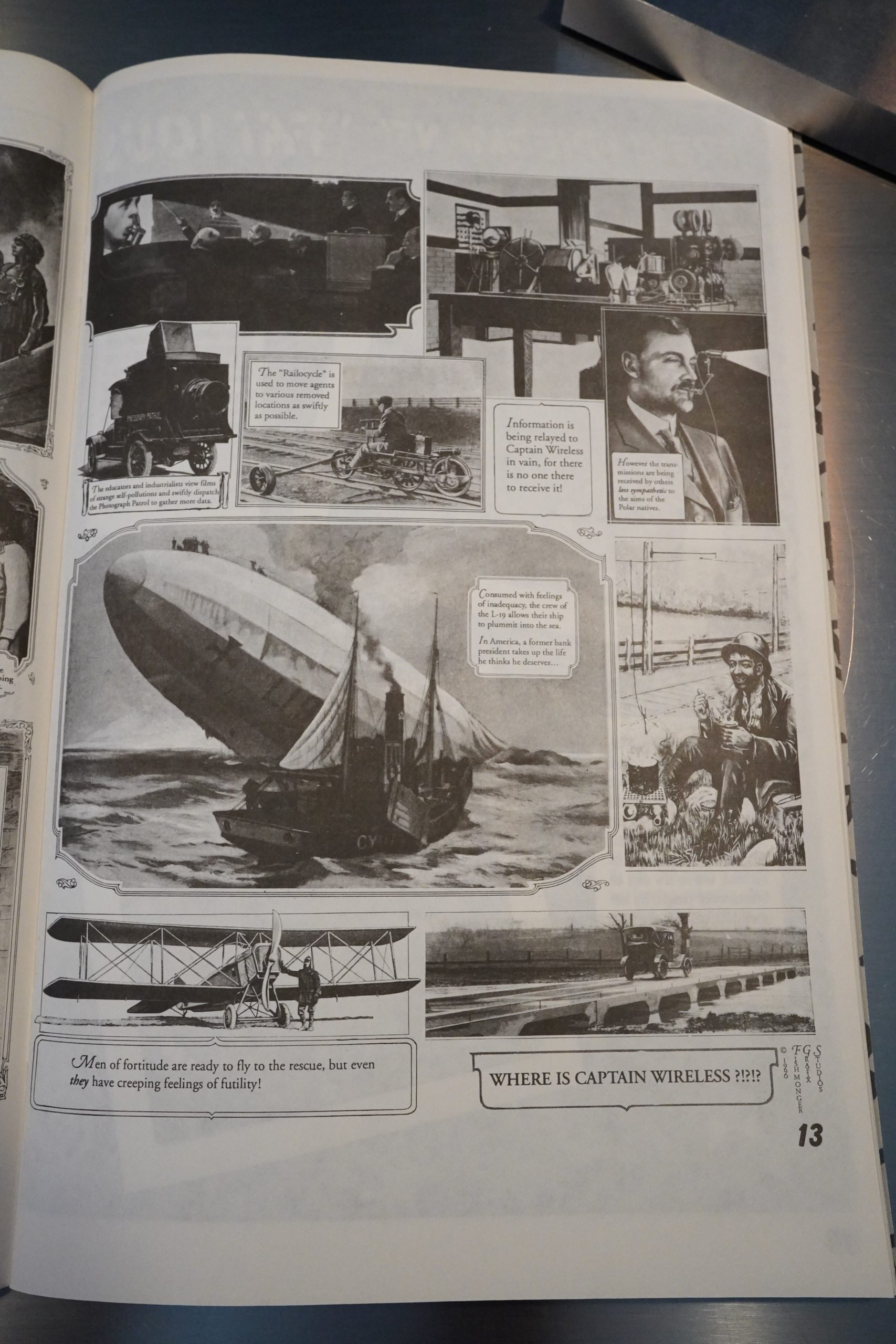

Dr. Ahmed Fishmonger does the most arty thing here.

And it’s a nice mixture of veterans and newer talents, like Jason Huerta.

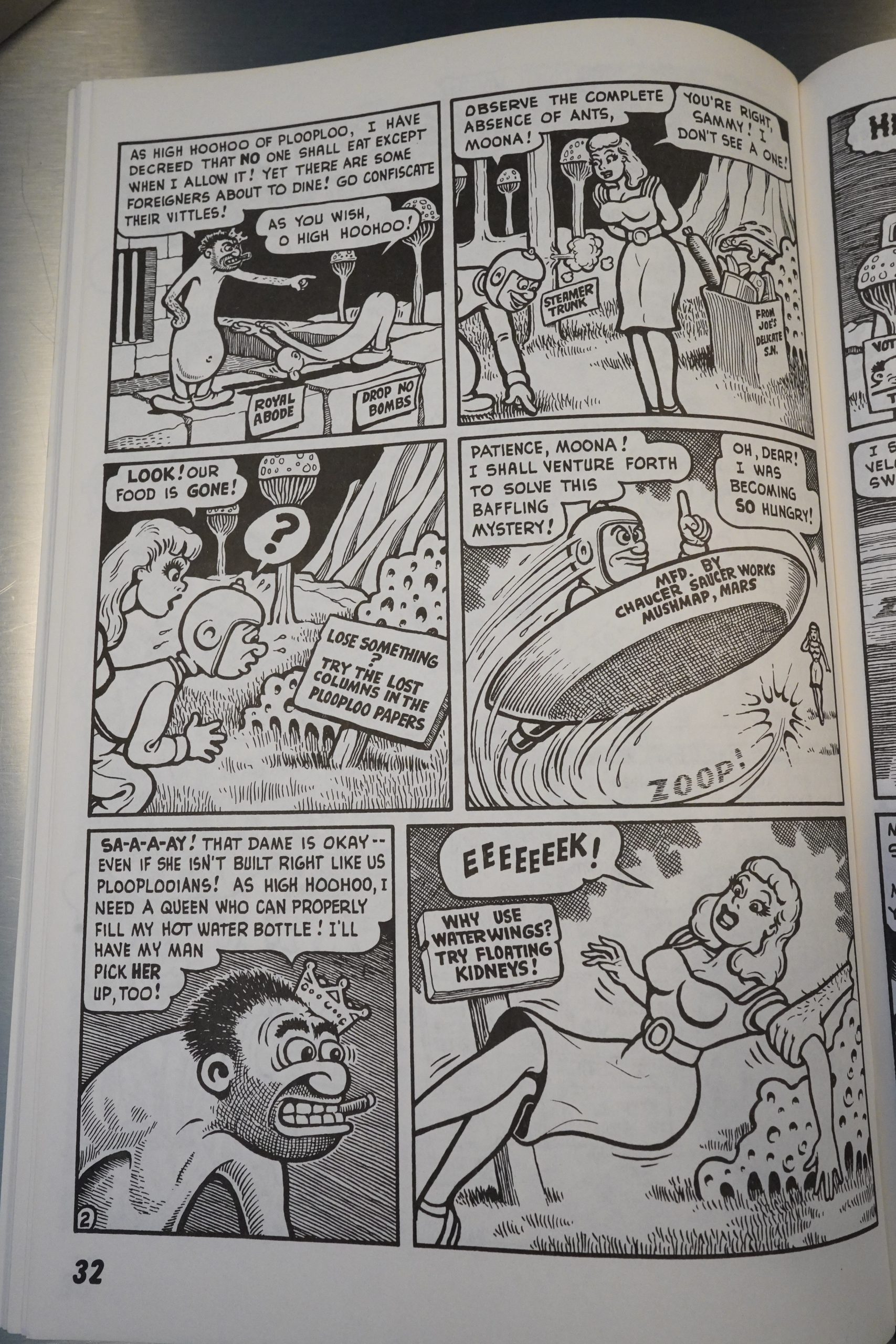

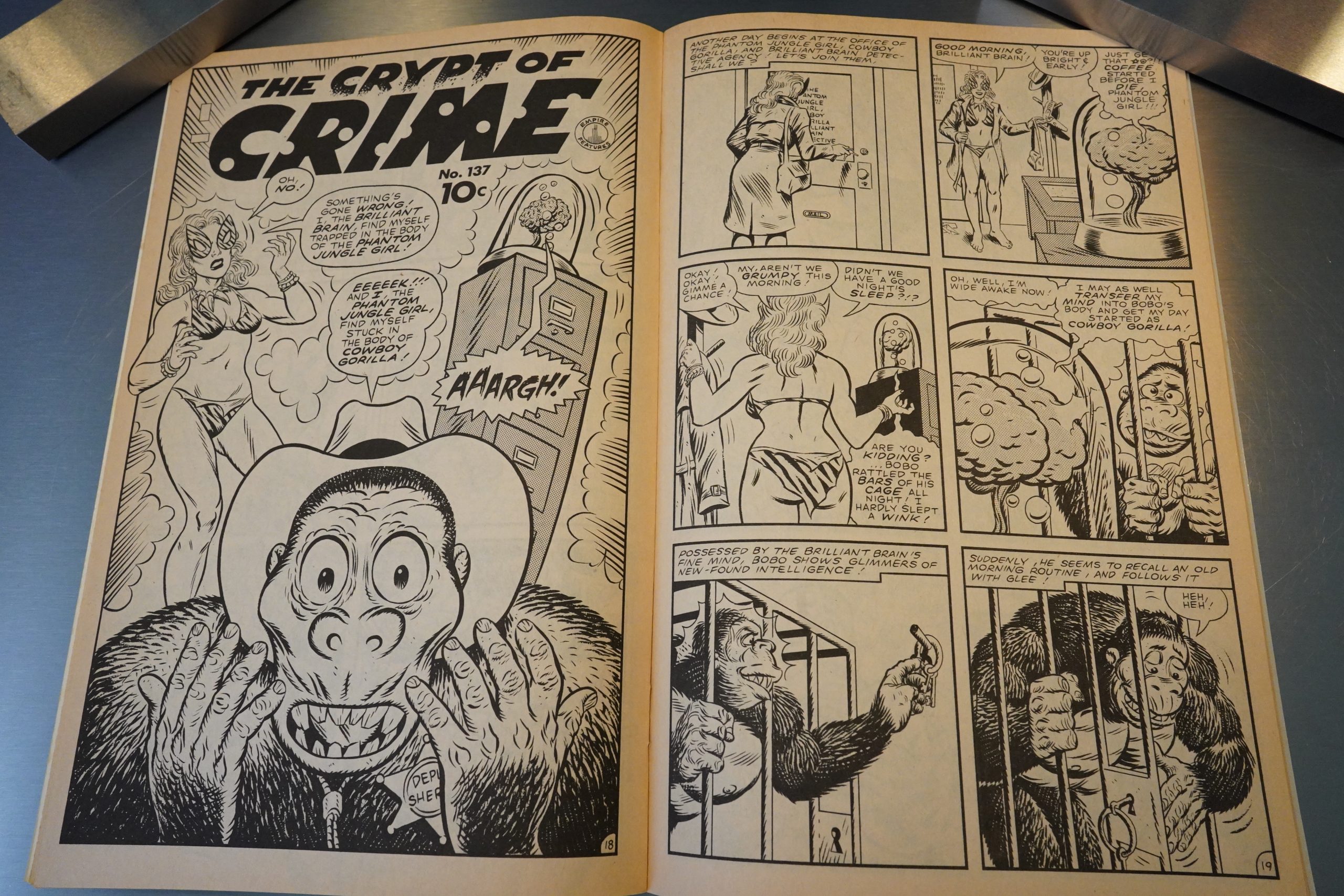

And Landman’s found a pretty good Wolverton story to reprint.

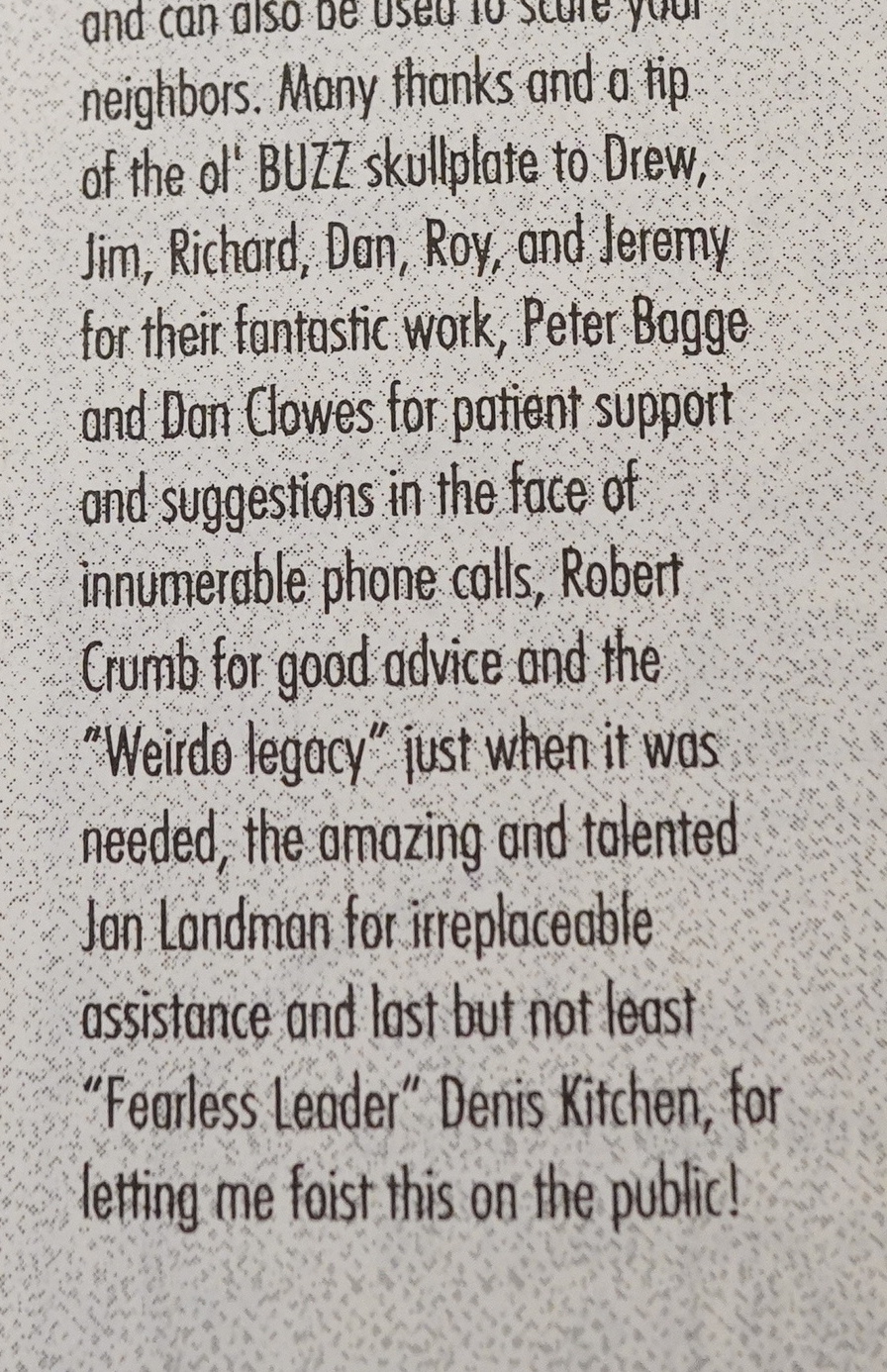

Landman’s apparently sent the book to everybody.

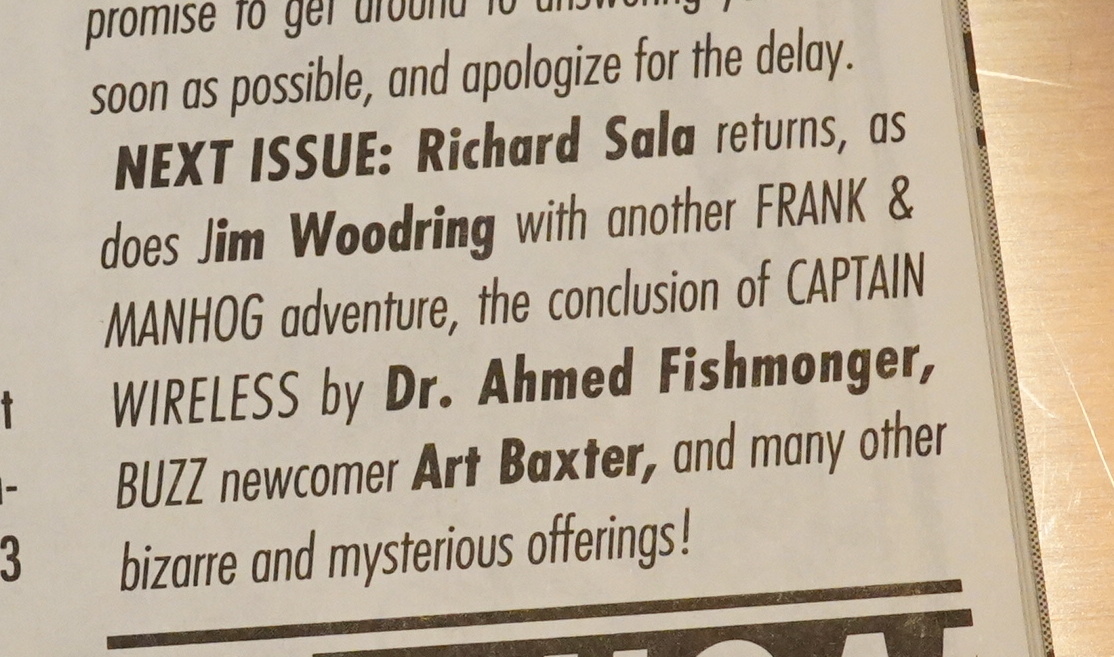

The third issue (which is 40 pages long) is the only one that has a “Next Issue” blurb. (Don’t you think?)

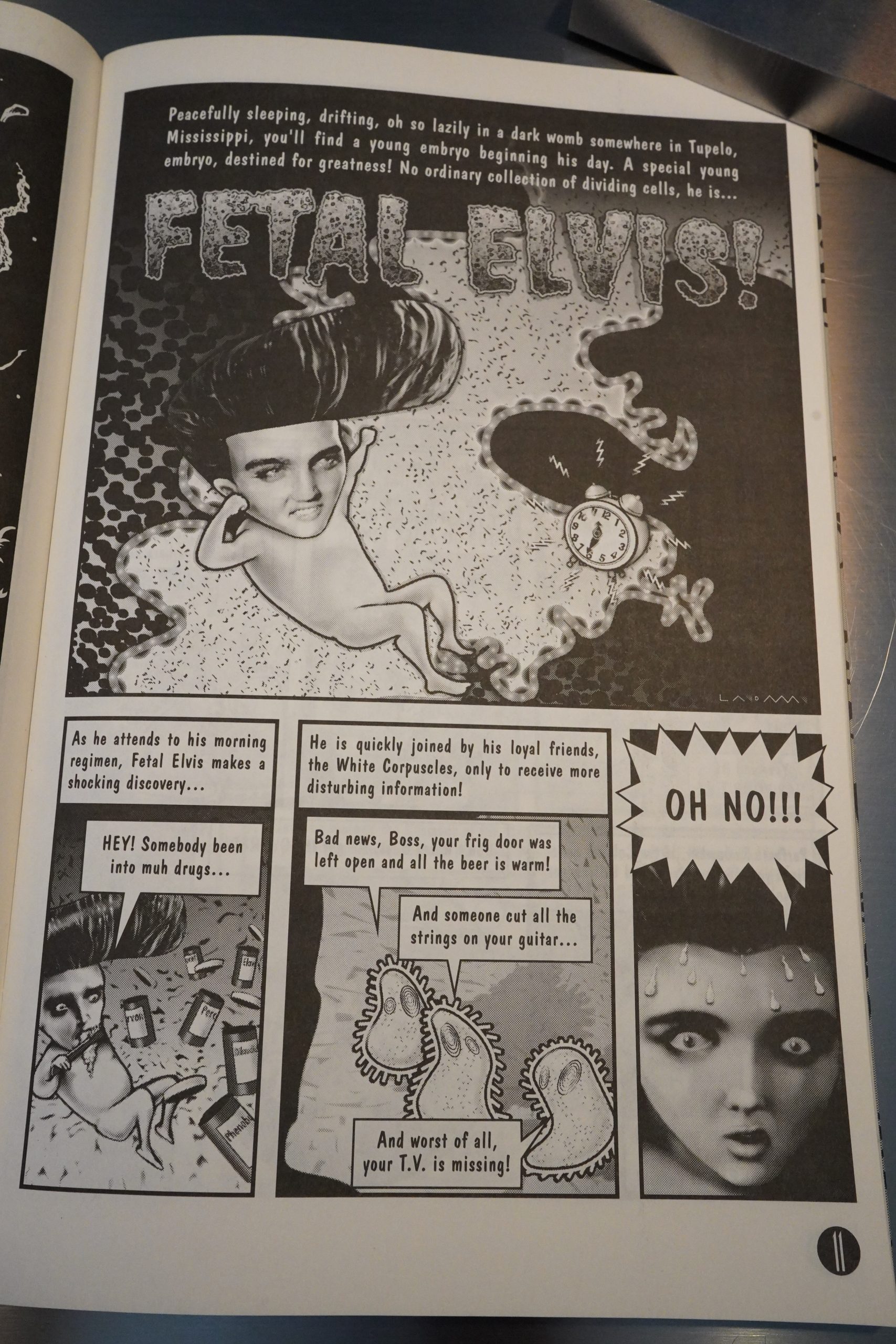

It has Landman’s most famous creation, Fetal Elvis, and the issue has more throw-away pieces than the previous issues. Perhaps Landman was kinda running out of steam, accepting more stuff?

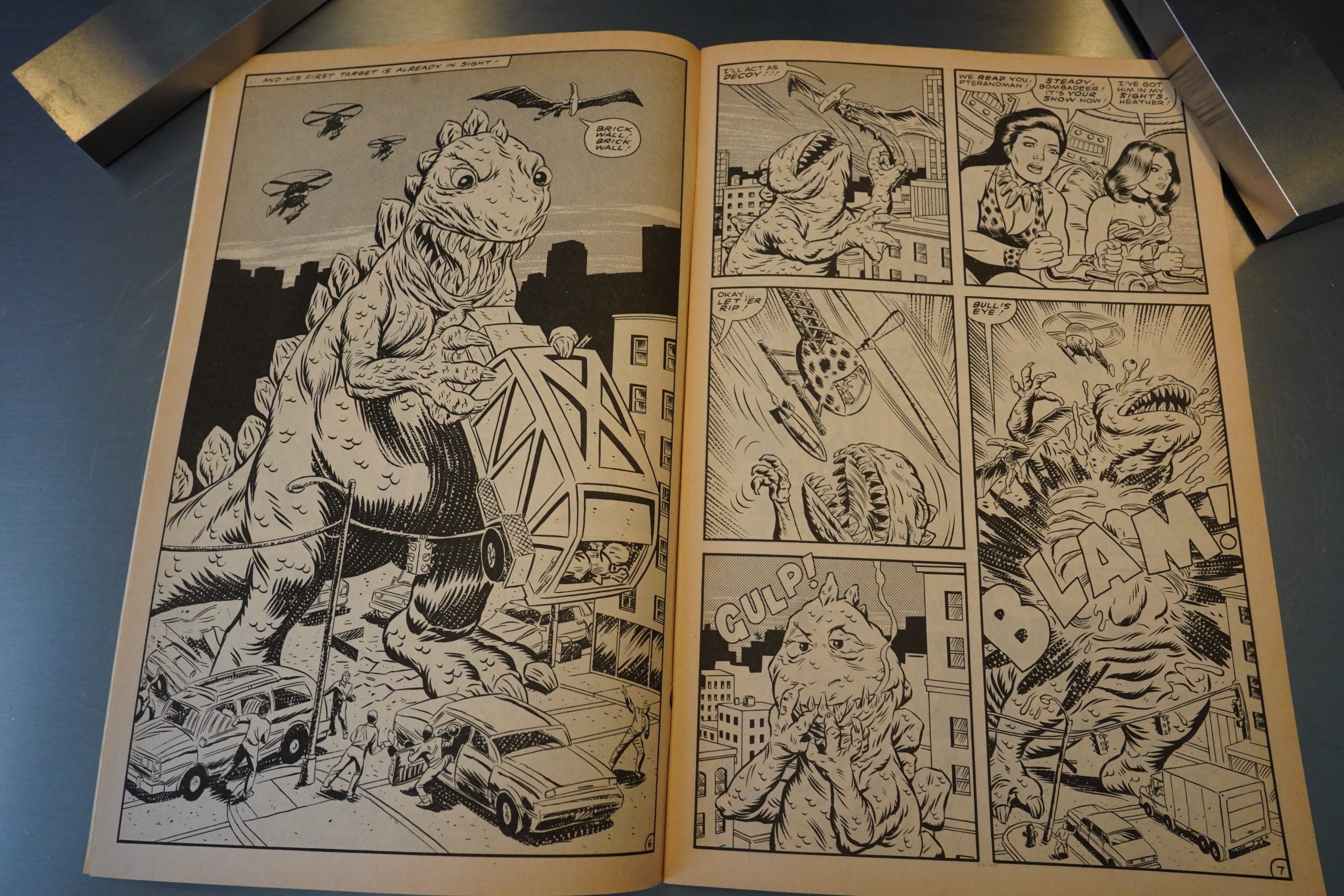

But with lunacy like this Mack White piece, you can’t really complain.

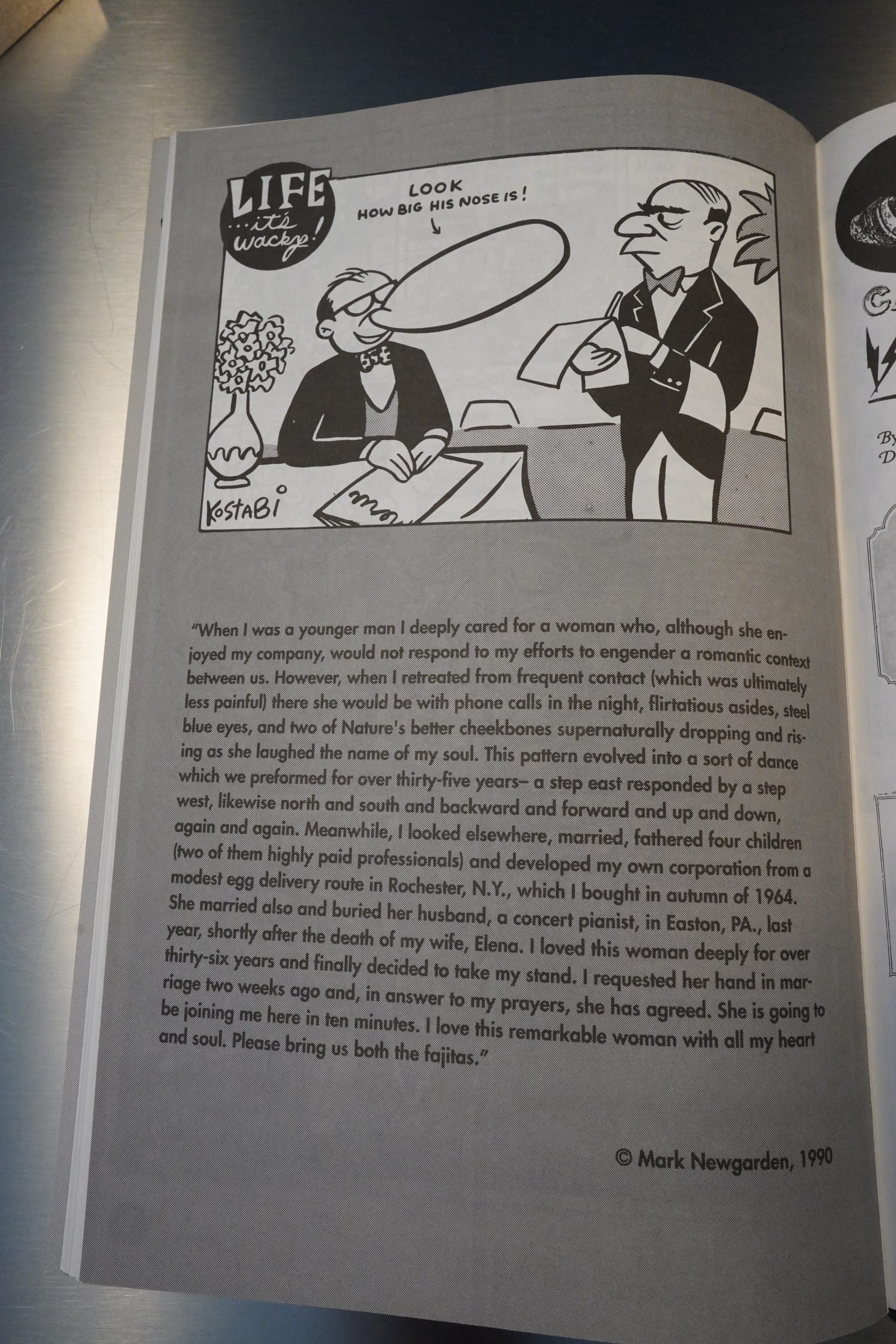

And we also get a couple of anti-humour Mark Newgarden pages.

So: This is a quality anthology, and it’s a shame that it only lasted three issues. But it’s a miracle that we got that many issues, so I’m not complaining.

Darcy Sullivan writes in The Comics Journal #146, page 46:

Kitchen Sink’s new Buzz also features a high

caliber of artists, loosely grouped around a

“wacky entertainment” theme. Two standout

covers created with computer graphics (as is

some of the interior work) have helped distin-

guish Buzz from KS’s somewhat similar Snarf.

But Buzz remains somewhat of a piffle.

The reprints are too familiar — Krazy Kat

and Basil Wolverton’s “Supersonic Sammy” so

far — and both the first two issues seem padded

A dime’s worth of non-stop zaniness usually

goes further than a dollar’s, which explains why

the books seem thin at 36 pages. And there’s

an odd sameness about the art, due to the pre-

sence of so many “hard-line” artists, from

maestros Dan Clowes and Charles Burns to edi-

tor Mark Landman, Jim Woodring, and Jeremy

Eaton, whose droll “‘Ork issyndicated

native papers.

The artists do give Buzz a seductive surface

energy, which accounts for most of the book’s

fun. Landman is apparently having a hoot of a

time putting this together, and his joy radiates

from page to reader. But Buzz comes across as

a dessert rather than a meal. It could use more

weight, perhaps a Mark Zingarelli or Carol

Tyler — someone whose work does more than

smirk. That said, we’re talking adjustment here,

not an abandonment of the book’s tone, sug-

gested by its very title. Lack of focus kills most

anthologies — take Bob Callahan’s book, ne

New Comics, which, in to include vir-

tually everybody, dissipates any possible synergy

between artists.

Jason Sachs writes in Amazing Heroes #188, page 123:

Kitchen Sink is also well-known as

one of the finest underground publish-

ers. Although undergrounds don’t

really exist any more in the classical

sense, their tradition still lives on with

such Kitchen Sink publications as

Blab! and the new Buzz. (By the way,

does anyone have any idea why so

many of these cool anthologies have

one-syllable titles?) Buzz #1 features

stories and art by such post-modern

comics favorites as Dan Clowes, Drew

Friedman, Richard Sala, and Jim

Woodring.

As you might expect, this comic is

something of a mixed bag. Woodring’s

three pieces are absolutely bizarre and

very nearly indecipherable. For in-

stance, one story, “Pulque,” has a

group of four cute kids meeting a

strange creature made up of cactus

Yes, it’s just as odd as it sounds.

Sala’s four-pager is yet another of his

explorations into bizarre neuroses,

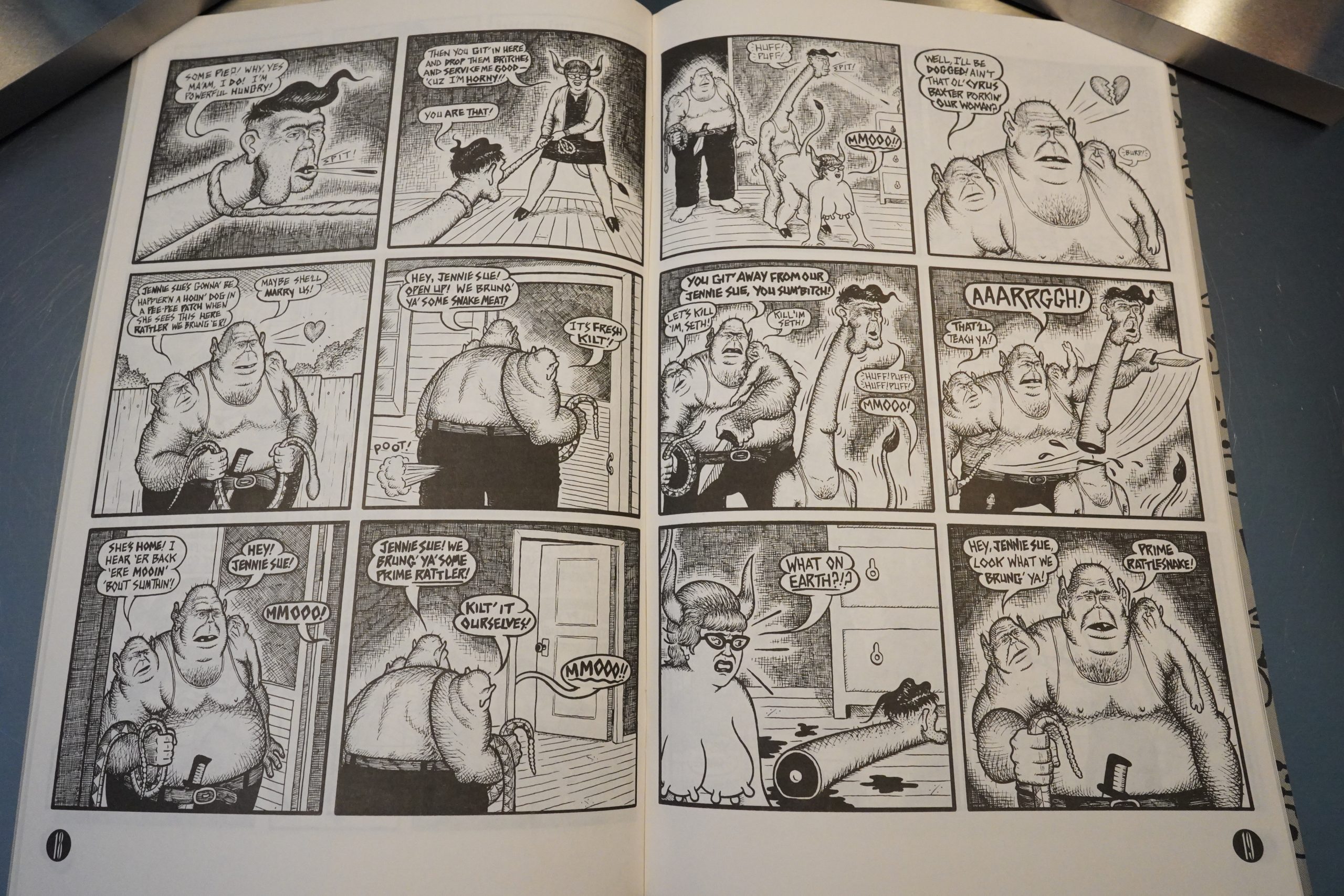

while Roy Tompkins tells the fairly

gross story of “Harvey the Hillbilly

Idiot,” and editor Mark landman tells

the alternately silly and strange story

of a freakish private detective.

Most of the work here is quite ac-

complished and some—Dan Clowes’s

back cover in particular—are quite

funny. However, all the new work in

Buzz pales in relation to the one page

of George Herriman’s Krazy Kat re-

printed here. Kmzy Kat is arguably the

greatest comic strip of all time. Few

artists come close to reaching Herri-

man’s consistent brilliance.

Readers looking for a good anthol-

ogy of post-modern cartoonists will

find one here. The Krazy Kat strip is

just a big bonus.

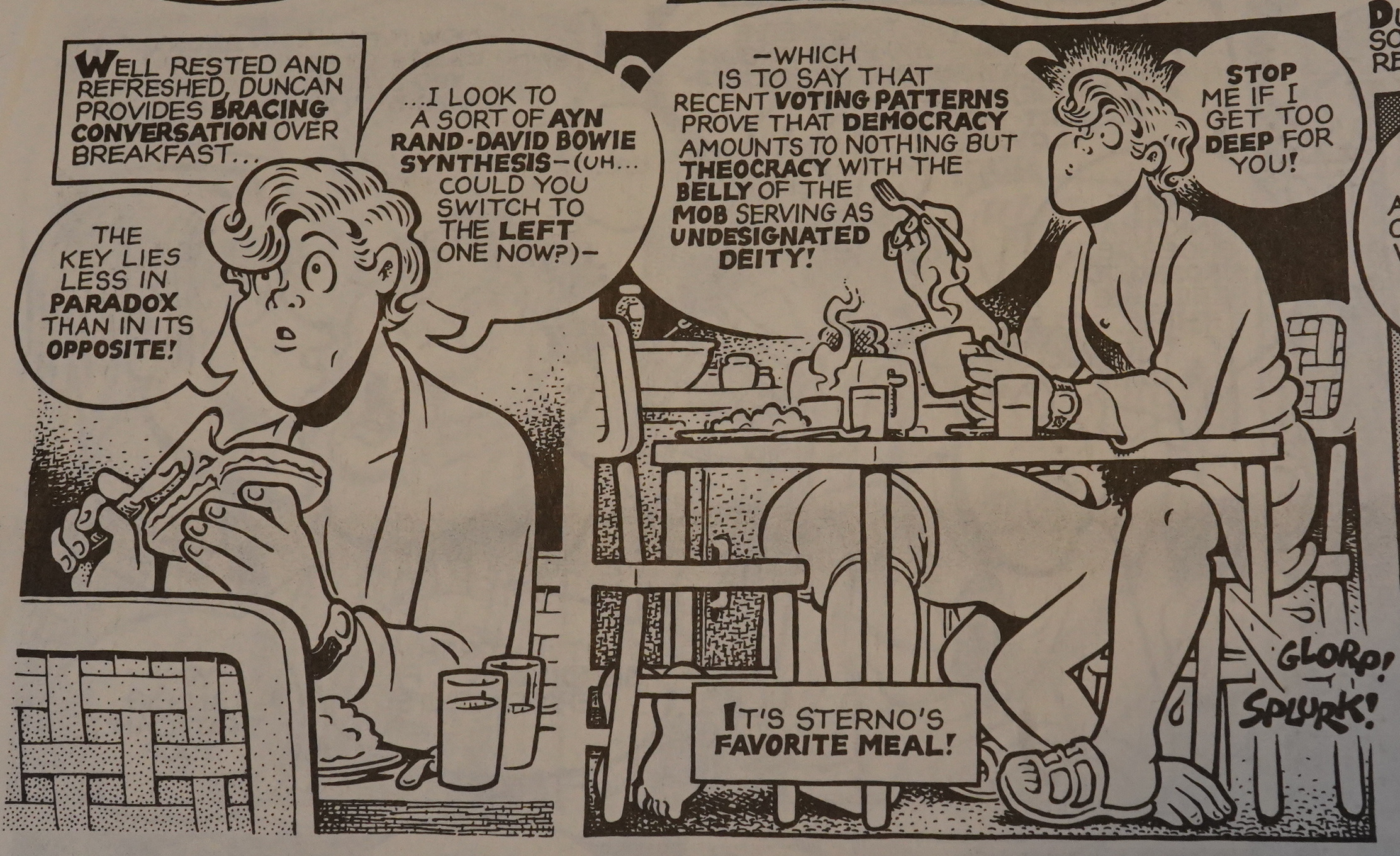

Burns is interviewed in The Comics Journal #148, page 78:

SULLIVAN: You brought up Manel; explain the Buzz story,

‘ ‘Naked Snack.

BURNS•. In the early ’80s, Marvel published something

called The Manel Comics Tryout Book, which was this

oversized book of blueline pencil drawings. You could try

out lettering, inking, pencilling, whatever. In a funny way

I was intrigued by the concept. My idea initially was to

buy maybe 20 Marvel Tryout Books and give them to all

my friends, and have them ink their versions of Spider-

Man.

I never pursued it. At that time the book was pricey

enough for me to go, “I can’t really afford to do this”;

it was 13 bucks or something. Years later, after I came

back from Italy and was wandering around New York,

some street person had one for three bucks. They prob-

ably stole them. So I bought a copy and just doodled on

it for a number of years, off and on. There was no real

intention behind it; I wasn’t thinking about ever having

it published.

When I was contacted by Mark Landman, the editor

of Buzz I knew that he worked with computers, and I knew

that I couldn’t force anyone I knew to letter this story. So

I asked him, ifl sent him a script, if he’d letter it for me.

And it worked out that way. I did a splash page and an

end page. so it’s fairly cohesive. It’s as cohesive as I get.

SULLIVAN’. And all the figures are your versions, drawn

BURNS: Some are very closely related. If you 100k at the

original Tryout Book, some are just inked versions of Peter

Parker or Aunt May or whoever. And with some I’ve done

something entirely different.

SULLIVAN: Your story is about people selling meat of sen-

tient animals on the black market. Sort ofa cannibalism

Story. What the original Story about?

BURNS: Oh, I have no idea. Just a Spider-Man story..

there’s nothing there.

SULLIVAN: I’ll go out in the alley and see if I can find

anyone selling Marvel merchandise.

BURNS: “Hey buddy… wanna buy a Manel Tryout

This is the one hundred and twenty-third post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.