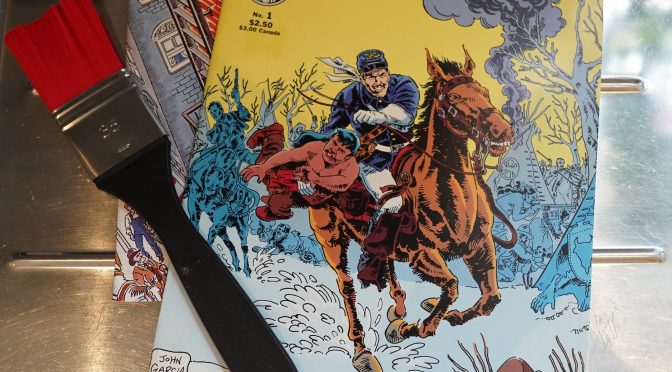

Owlhoots (1990) #1-2 by James Vance and John Garcia

Hot on the heels of the critical success of Kings in Disguise, Kitchen Sink publishes a new series written the same author (but with a different artist). I didn’t feel like Kings in Disguise was altogether successful, but it was certainly an attempt at doing something new and different in comics.

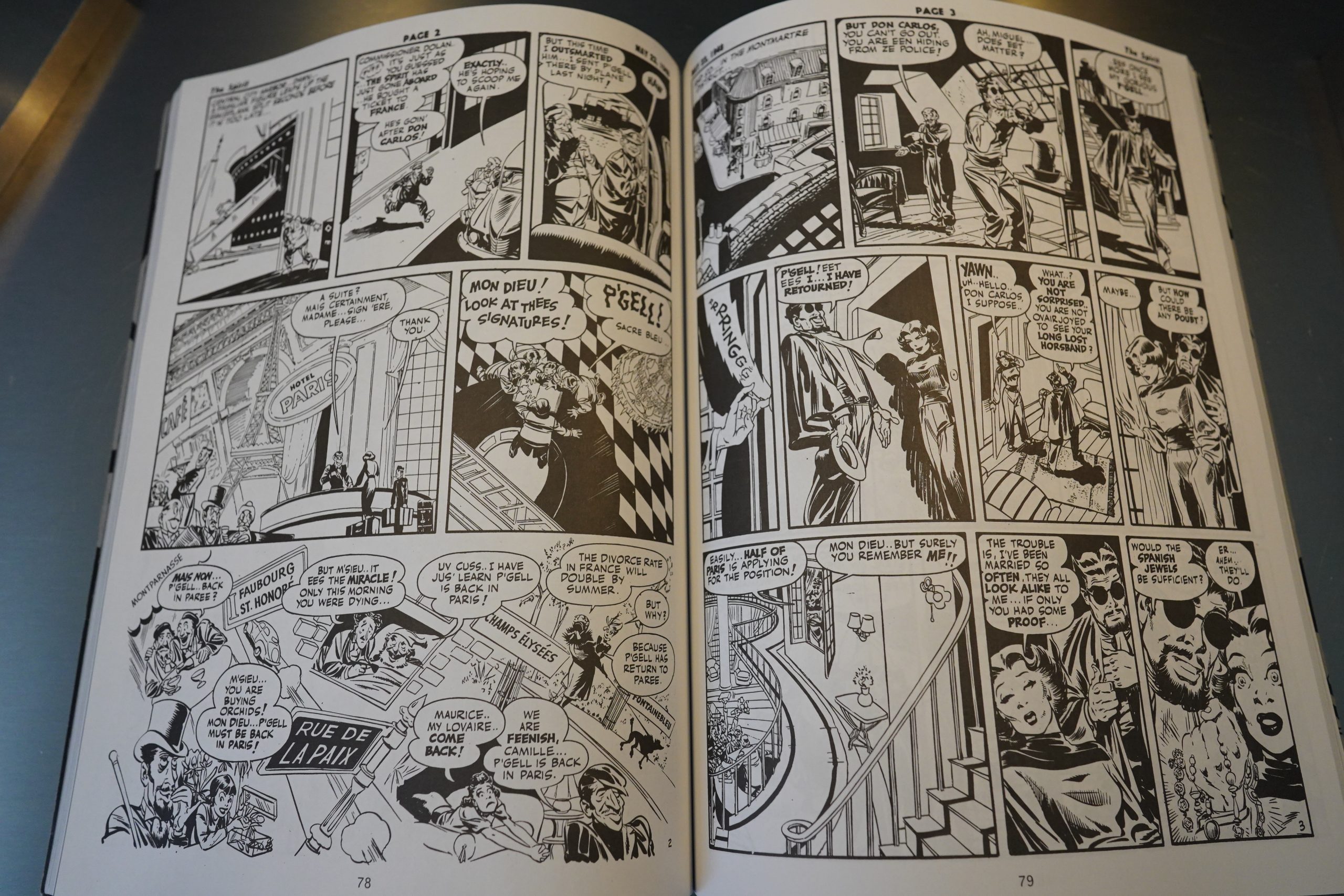

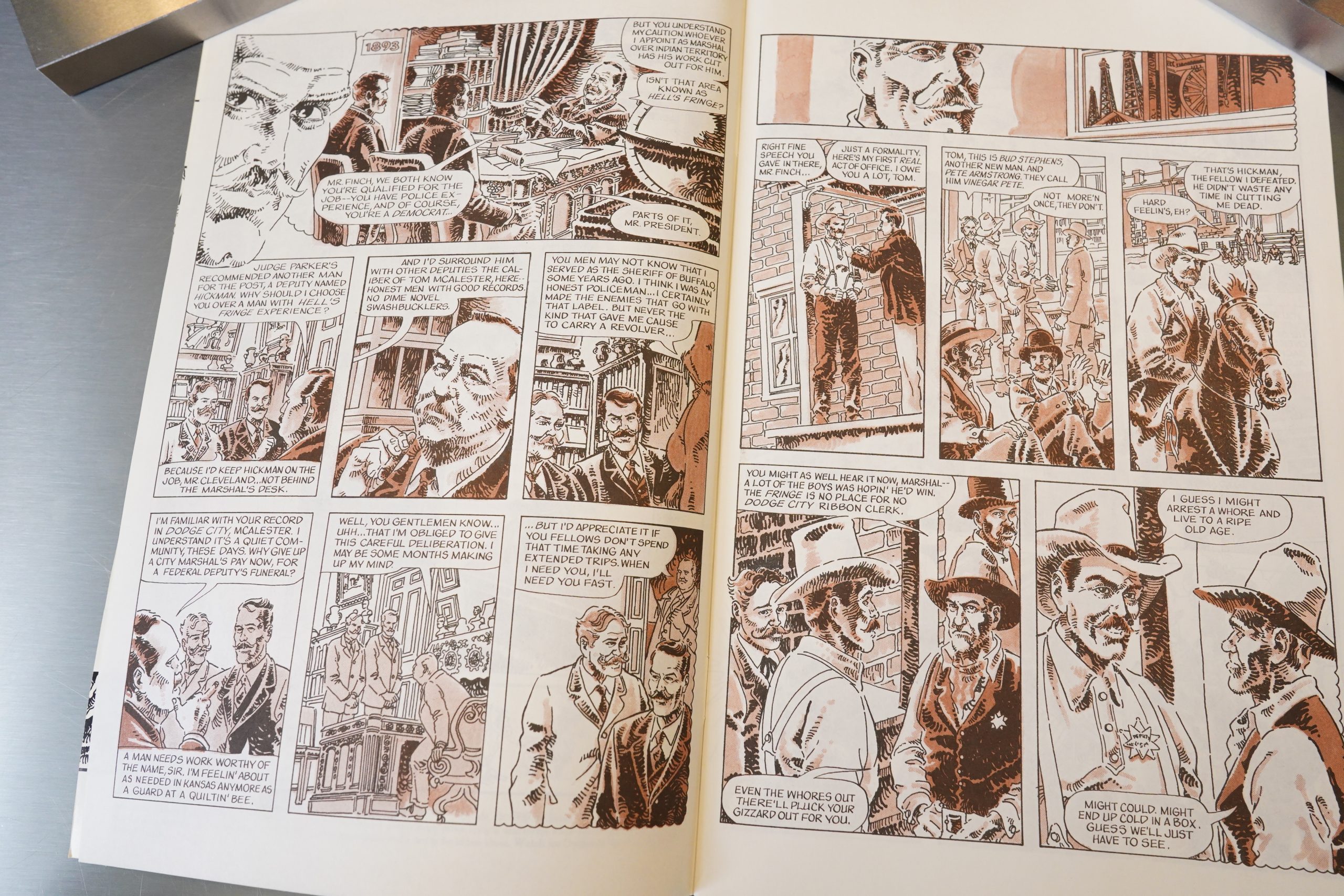

Just flipping through this book, it looks like it’s a bit ahead of its time: Using a single colour would become a signifier of Serious Comics a decade later, but usually not done in this way — it sits uncomfortably between being a kind of painterly wash and standard comics colouring.

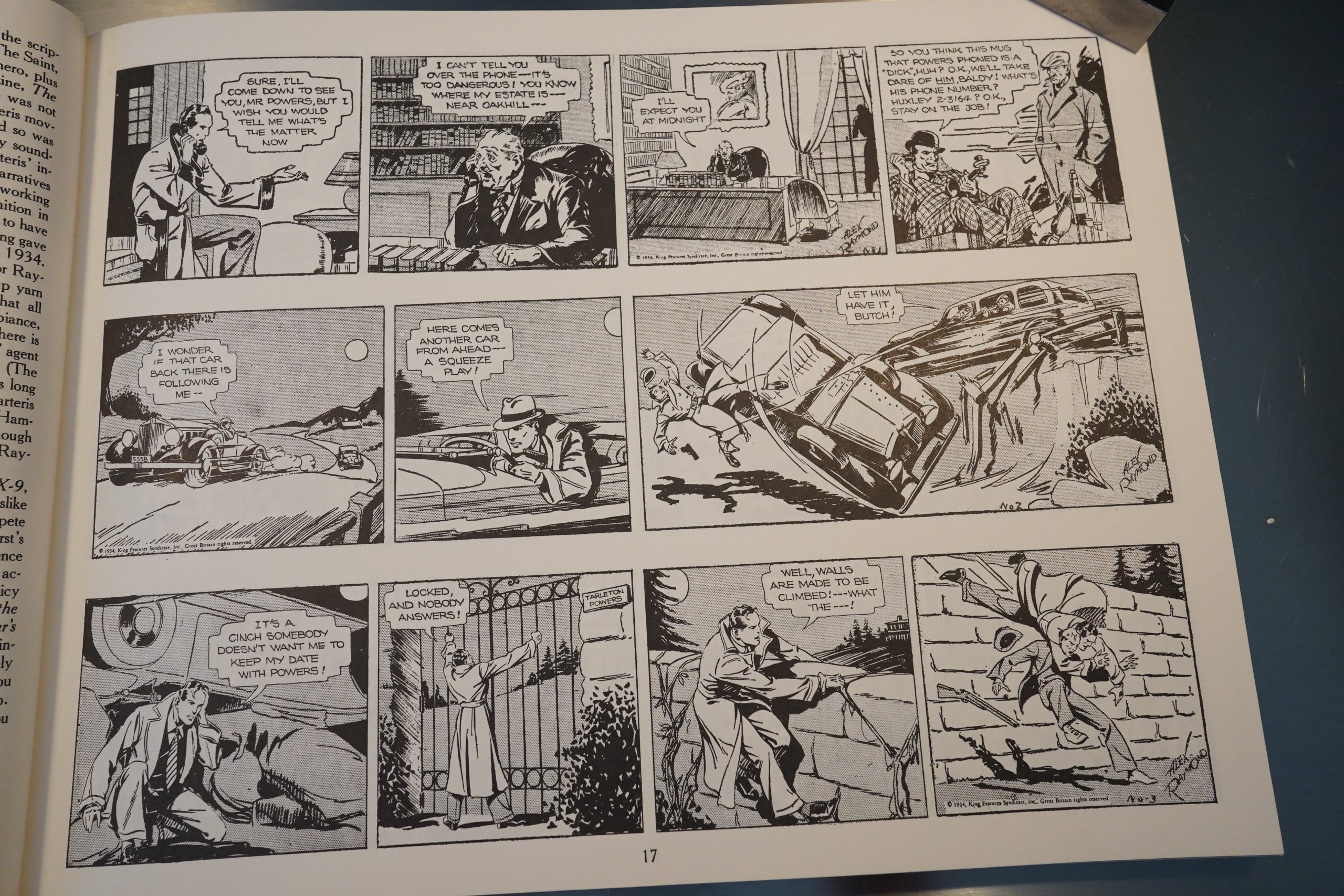

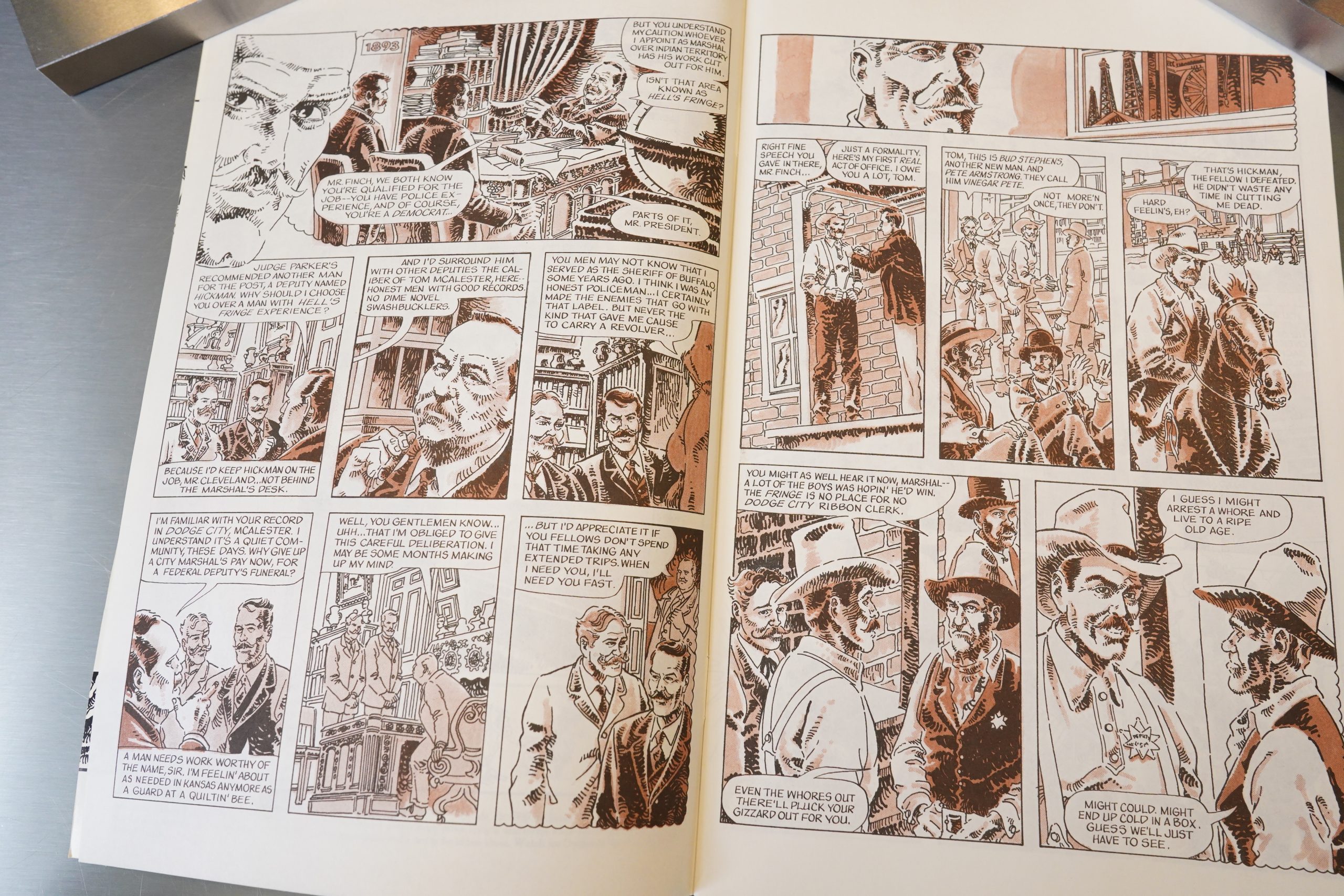

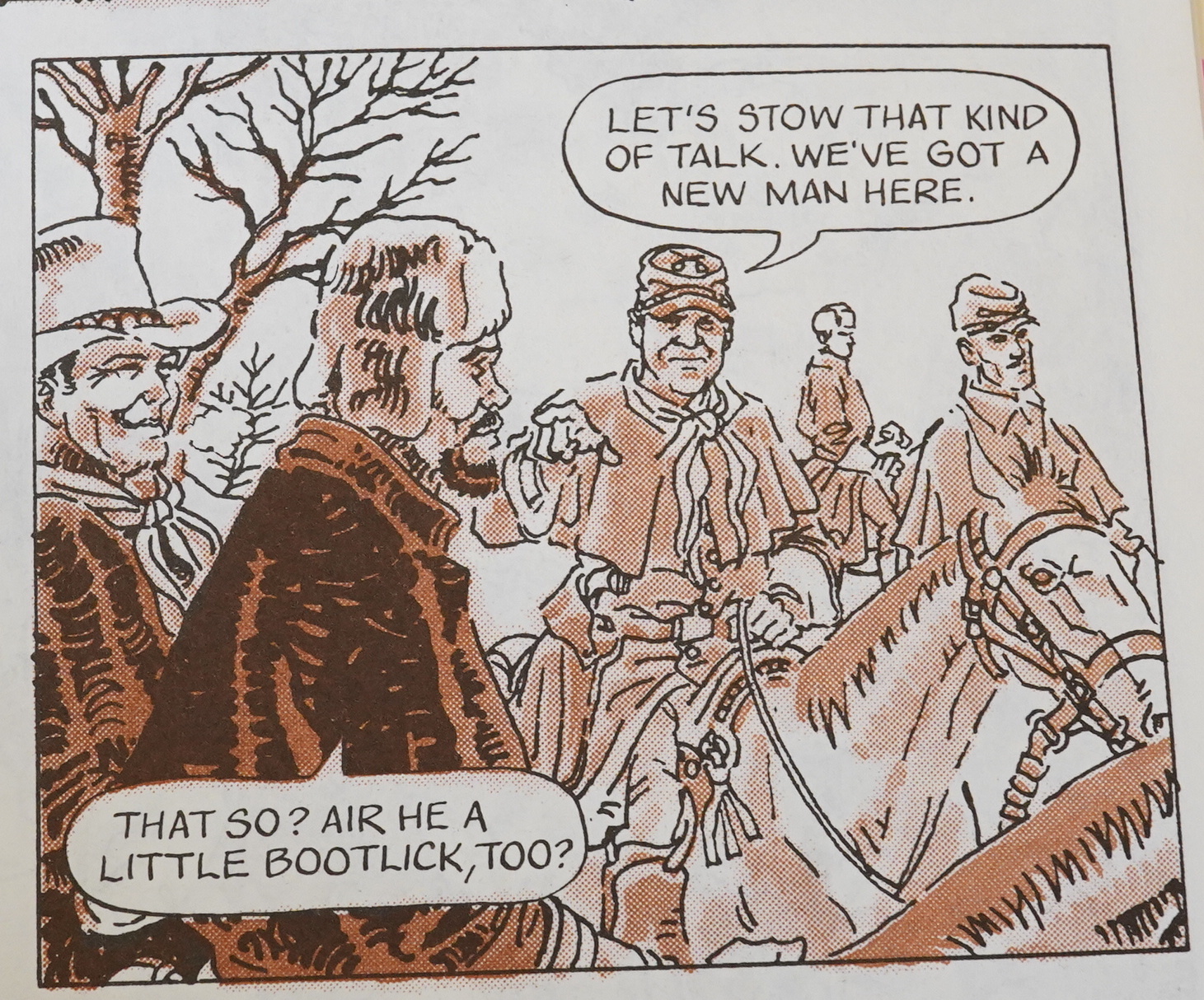

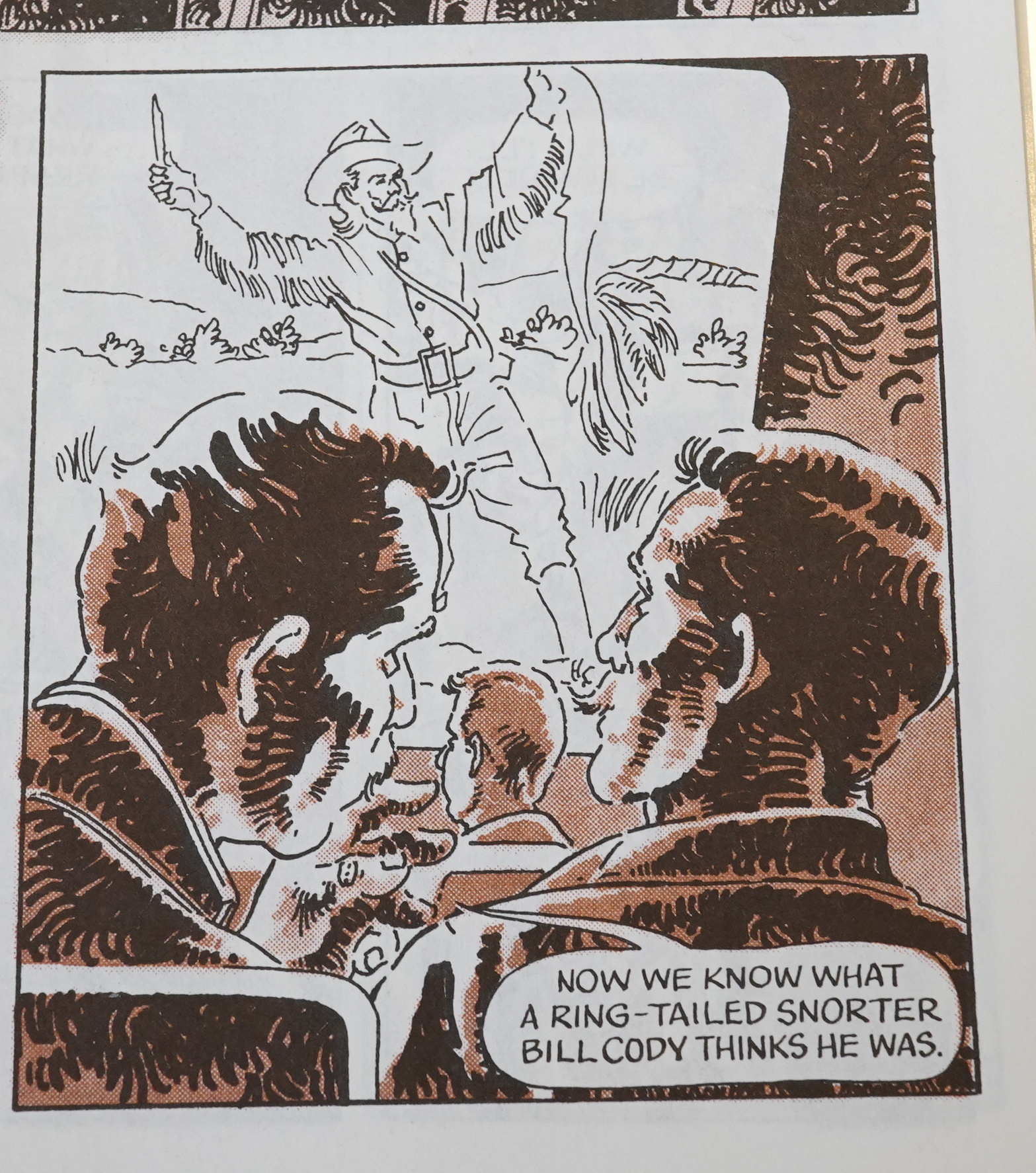

And this is how the book starts out: It looks like it’s going to be a very talky book about going out west and stuff…

… but that was just a flashback, and that guy is now old and working as a night watchman for a plant.

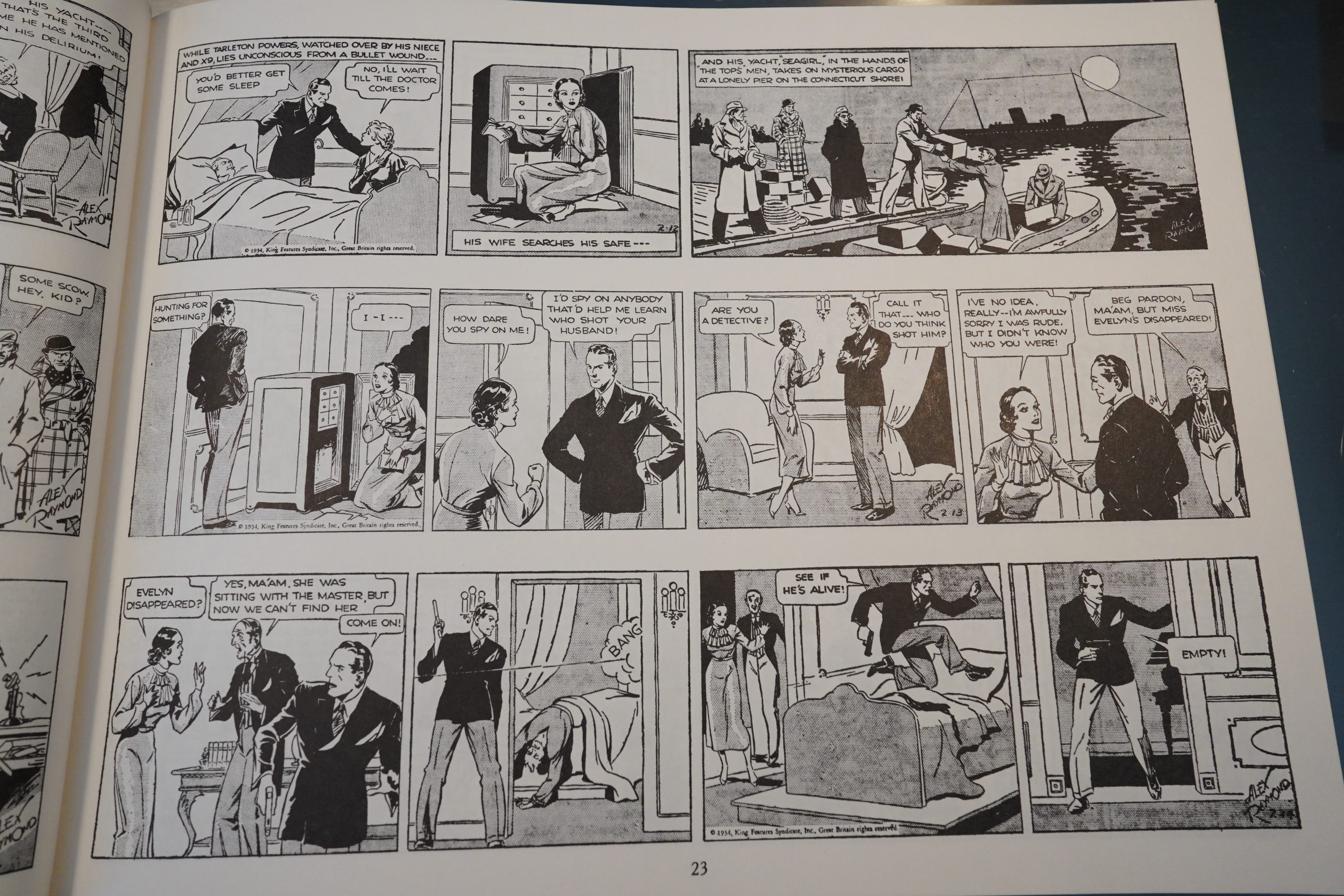

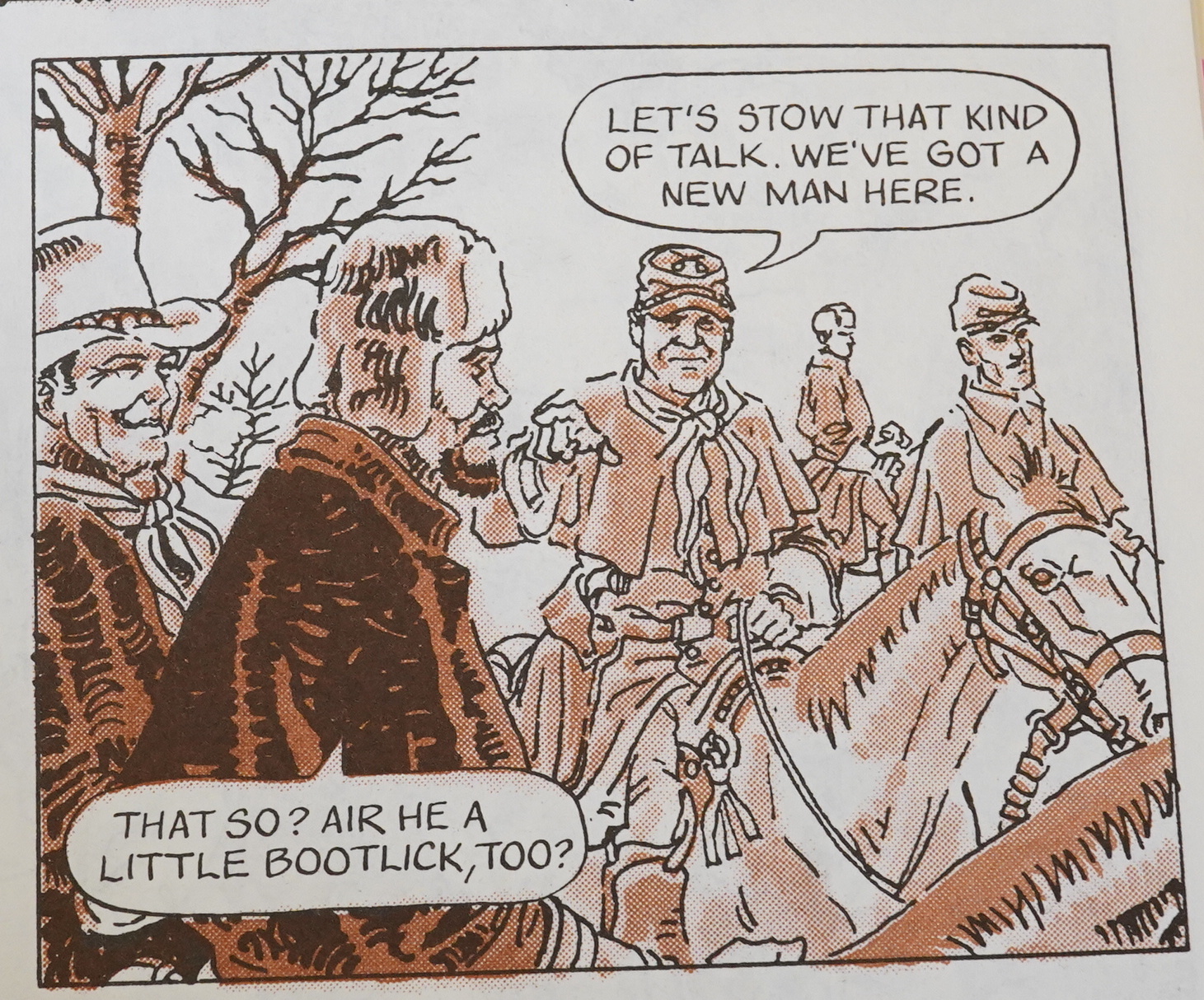

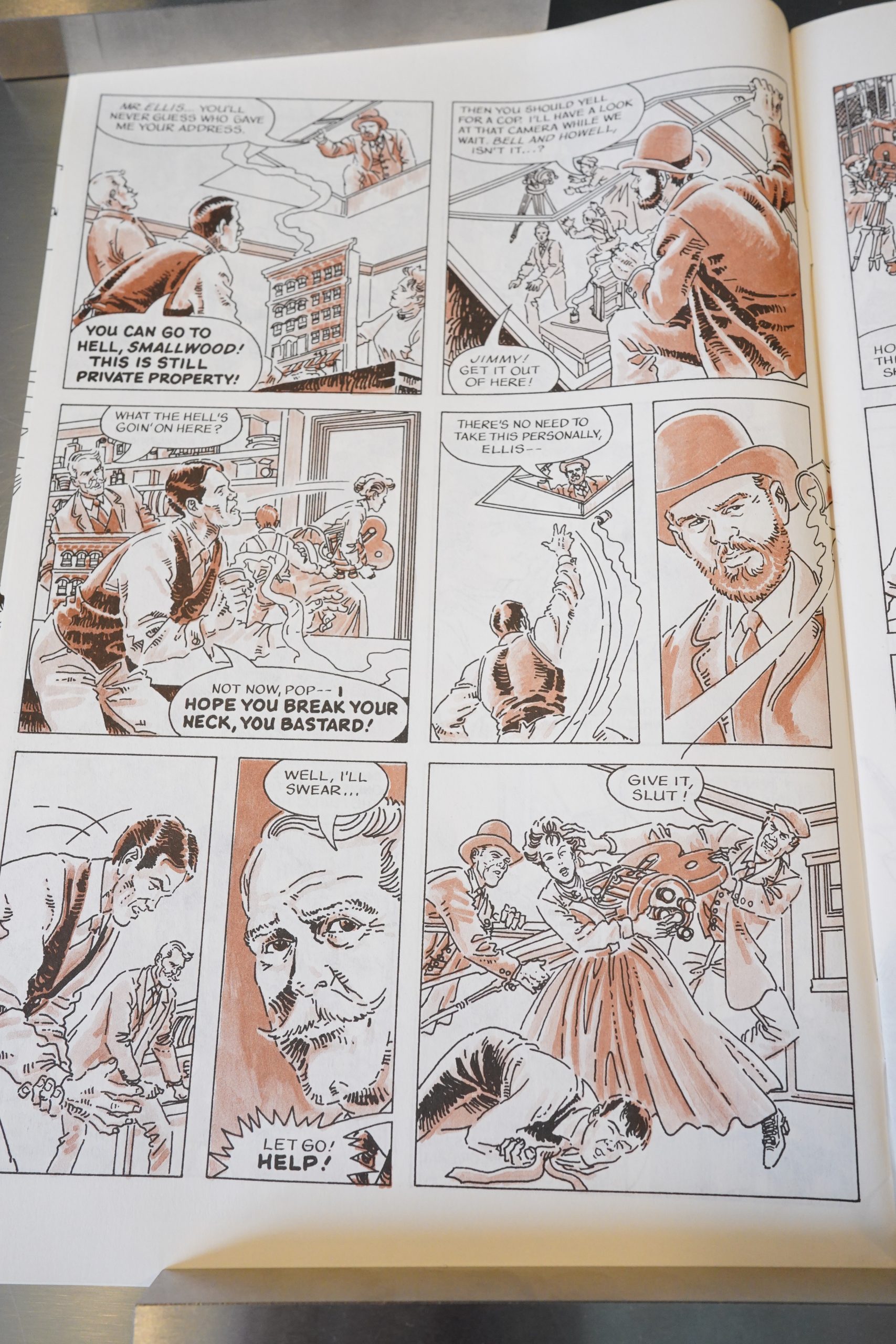

The storytelling problems happen immediately: We have no idea who these people are, and it’s pretty hard to tell what’s going on here, because the way the characters are drawn, it’s just hard to tell who’s who and even where they are in relation to each other. I wondered whether this was Garcia’s first comic, but apparently not.

The problems are exacerbated by Vance trying to give a lot of period colour to the dialogue, but landing at abstruse incomprehension instead.

I guess he air.

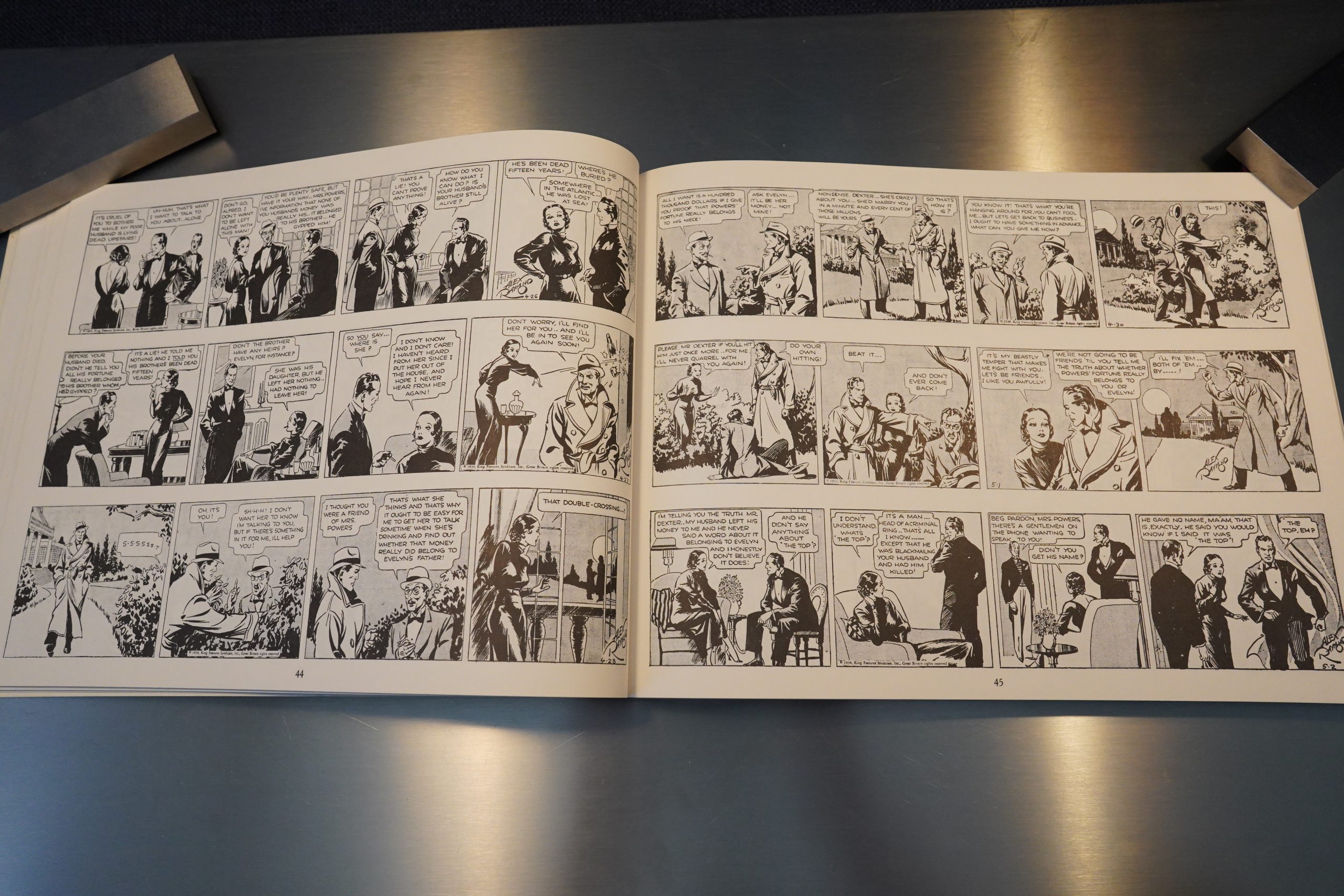

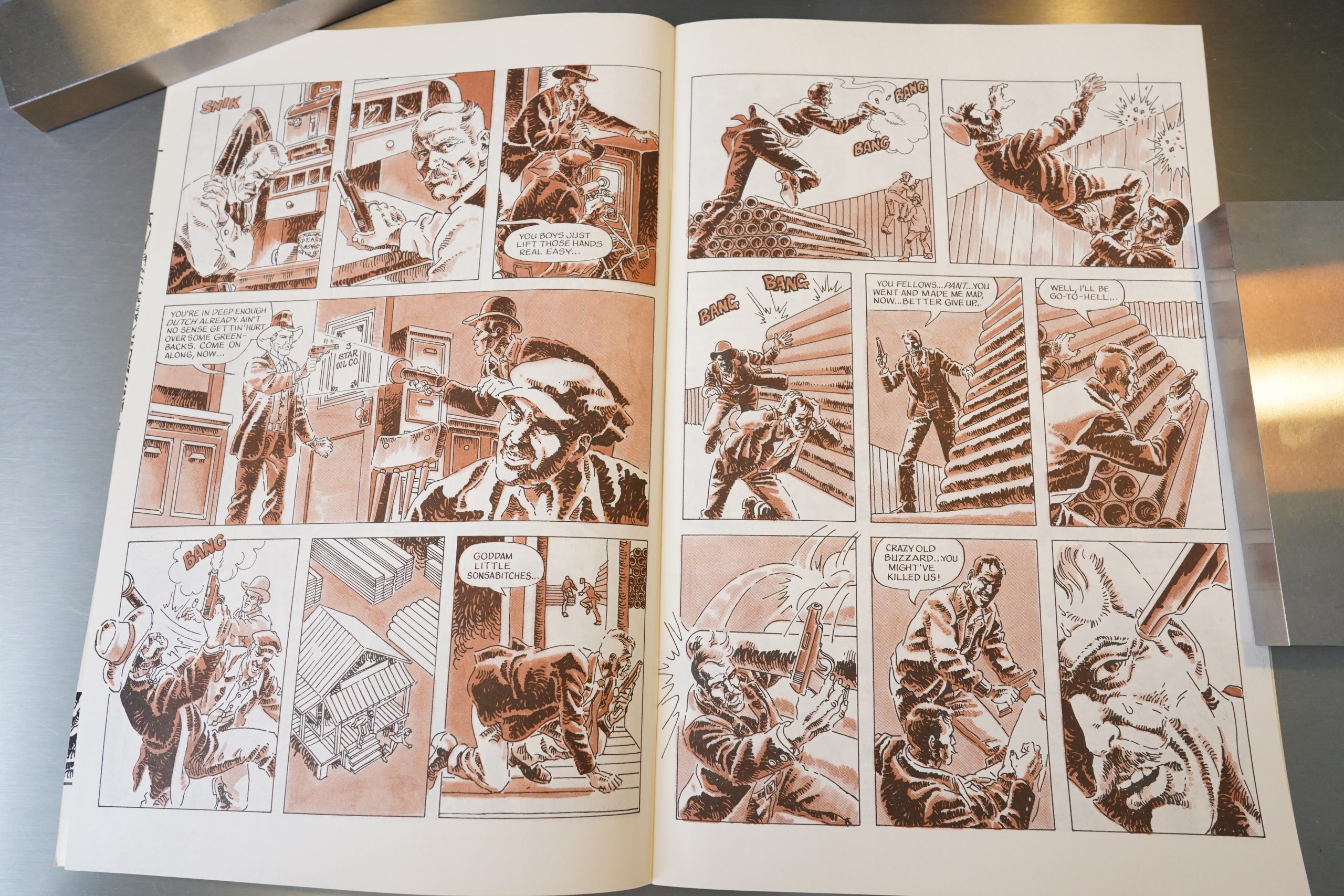

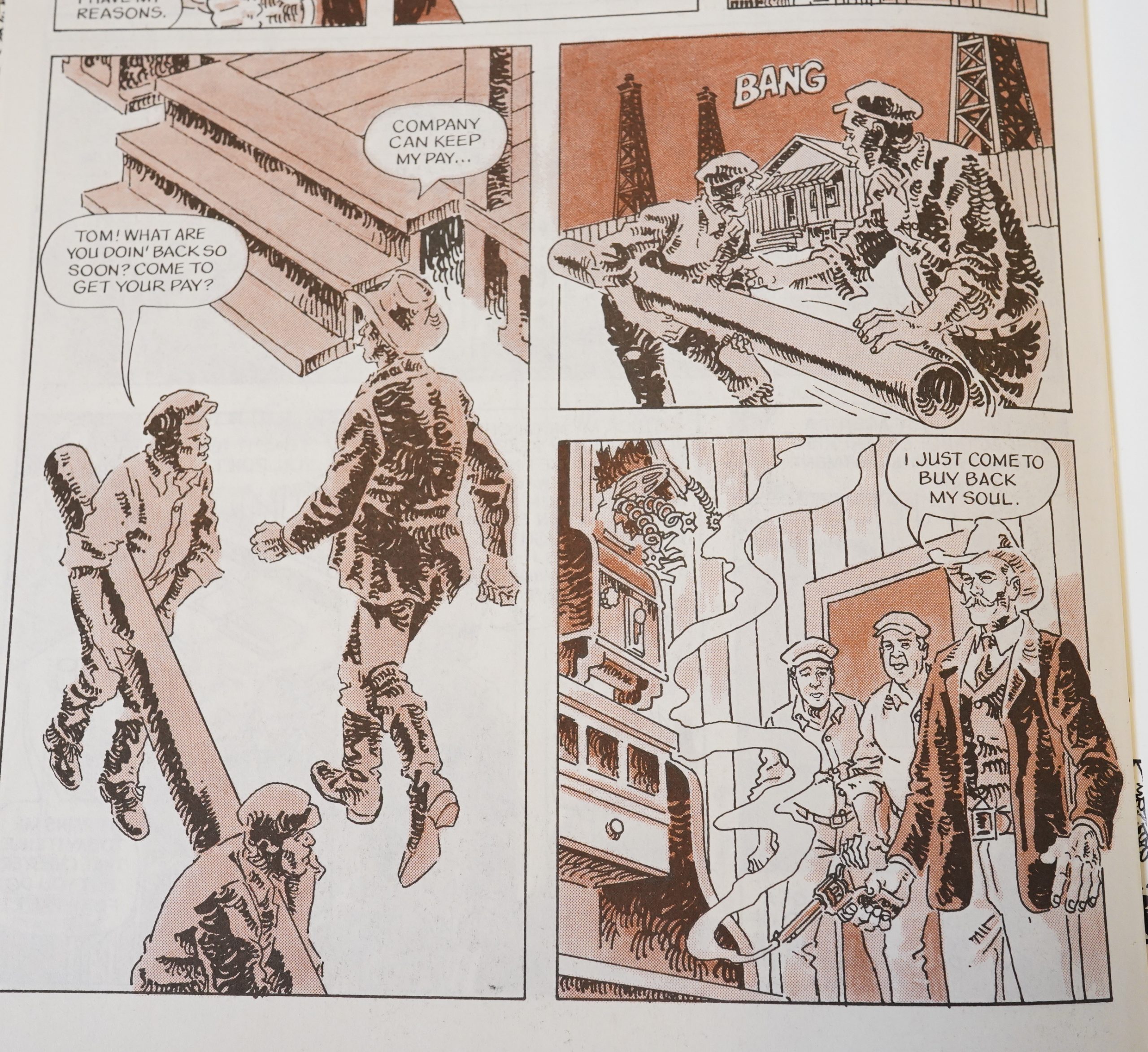

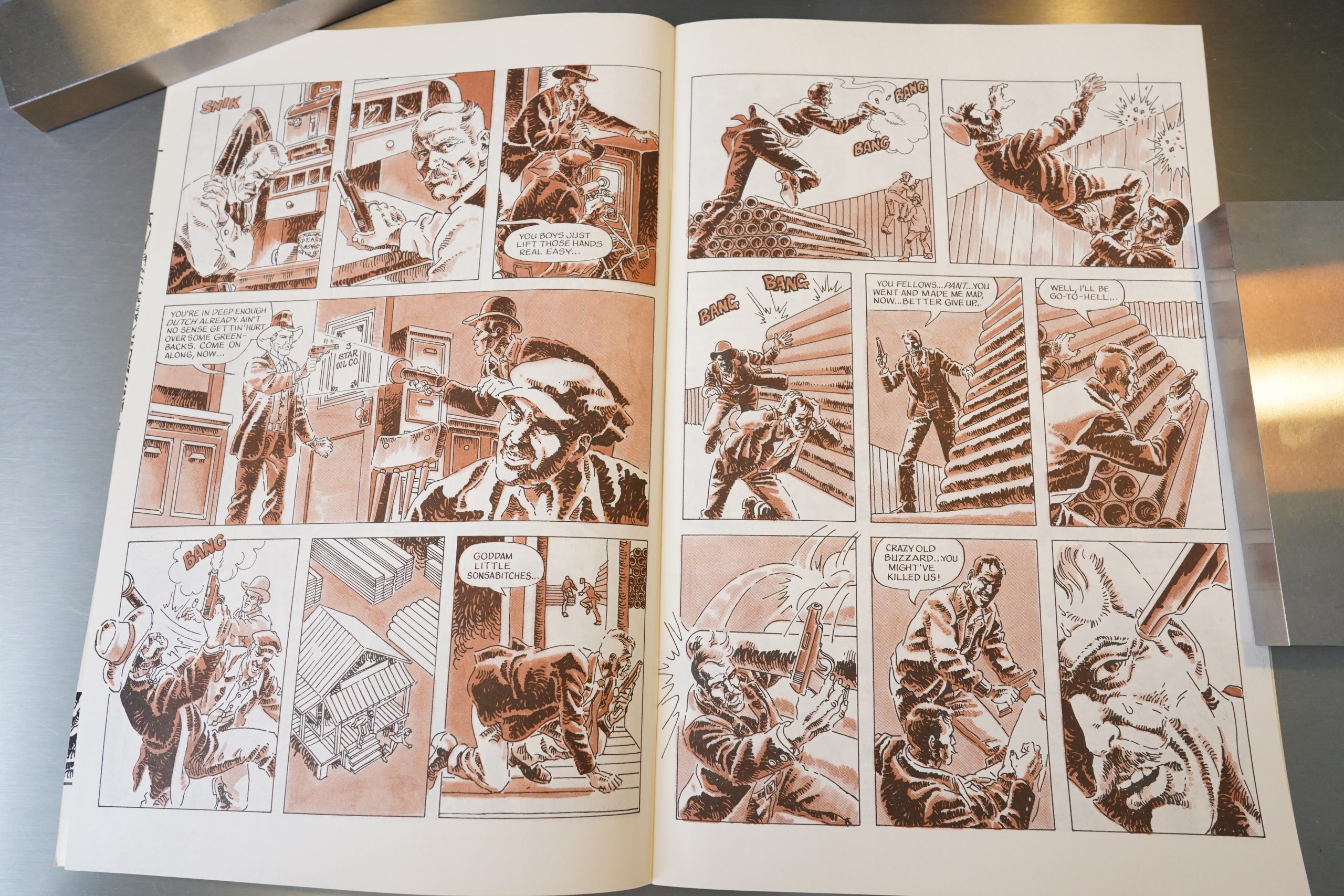

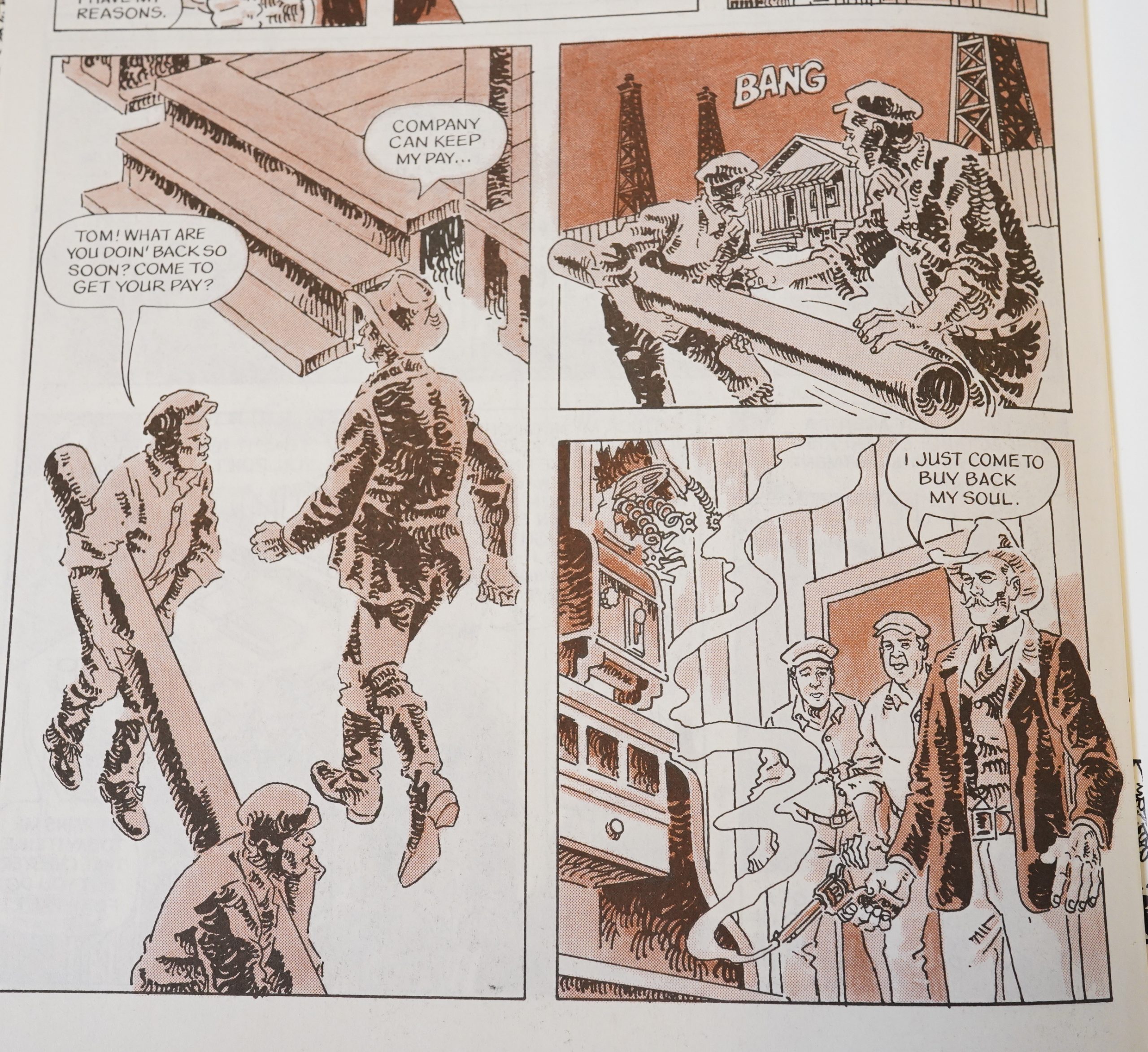

The scenes also veer between attempting verisimilitude and doing set pieces that even the cheesiest TV series would shy away from. Here, Our Hero takes revenge against his place of employment for… er… degrading him by giving him a job? How dare they!

(Oh, right, the plot: It’s about an old, forgotten western hero making a movie about his life.)

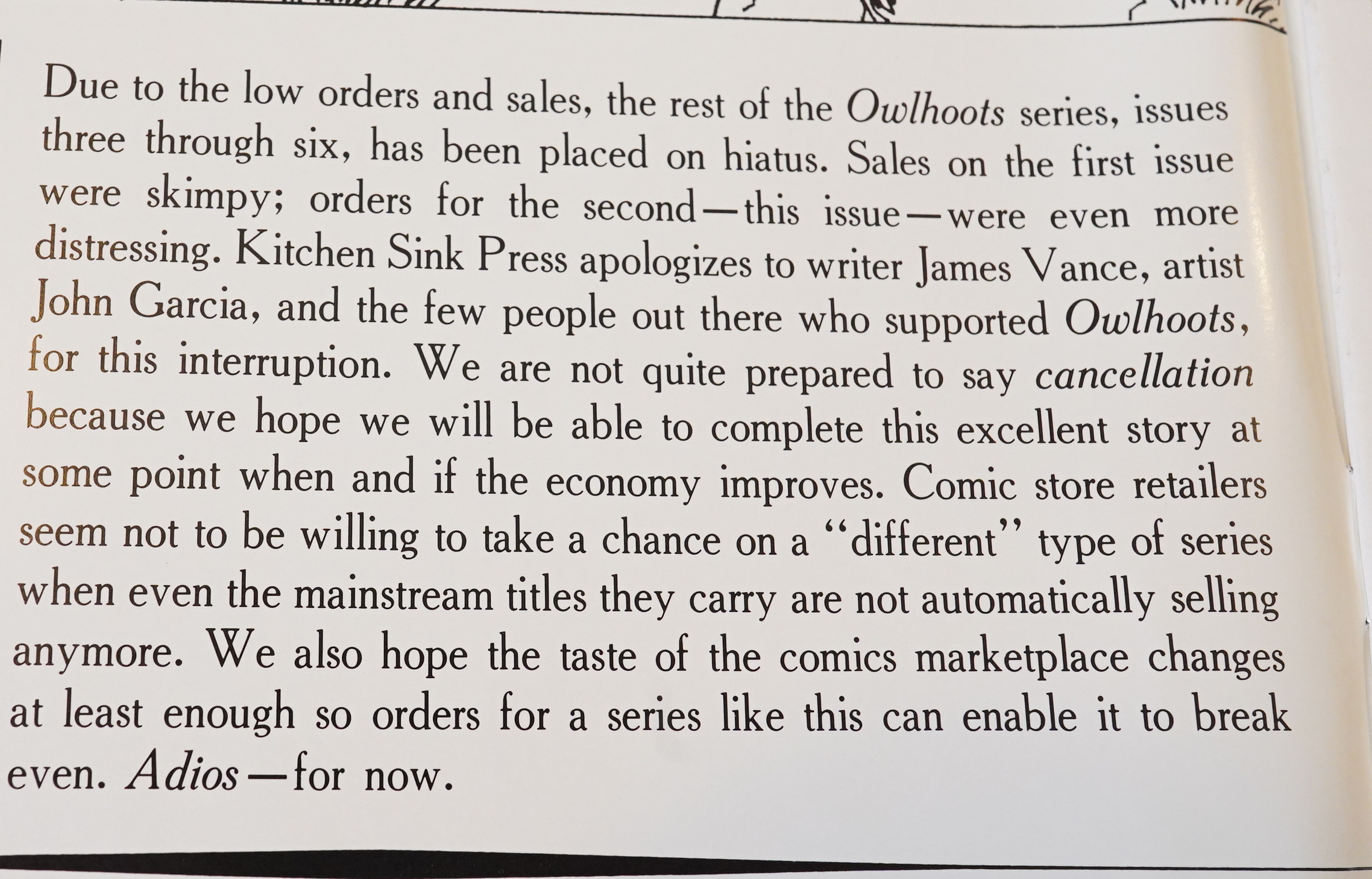

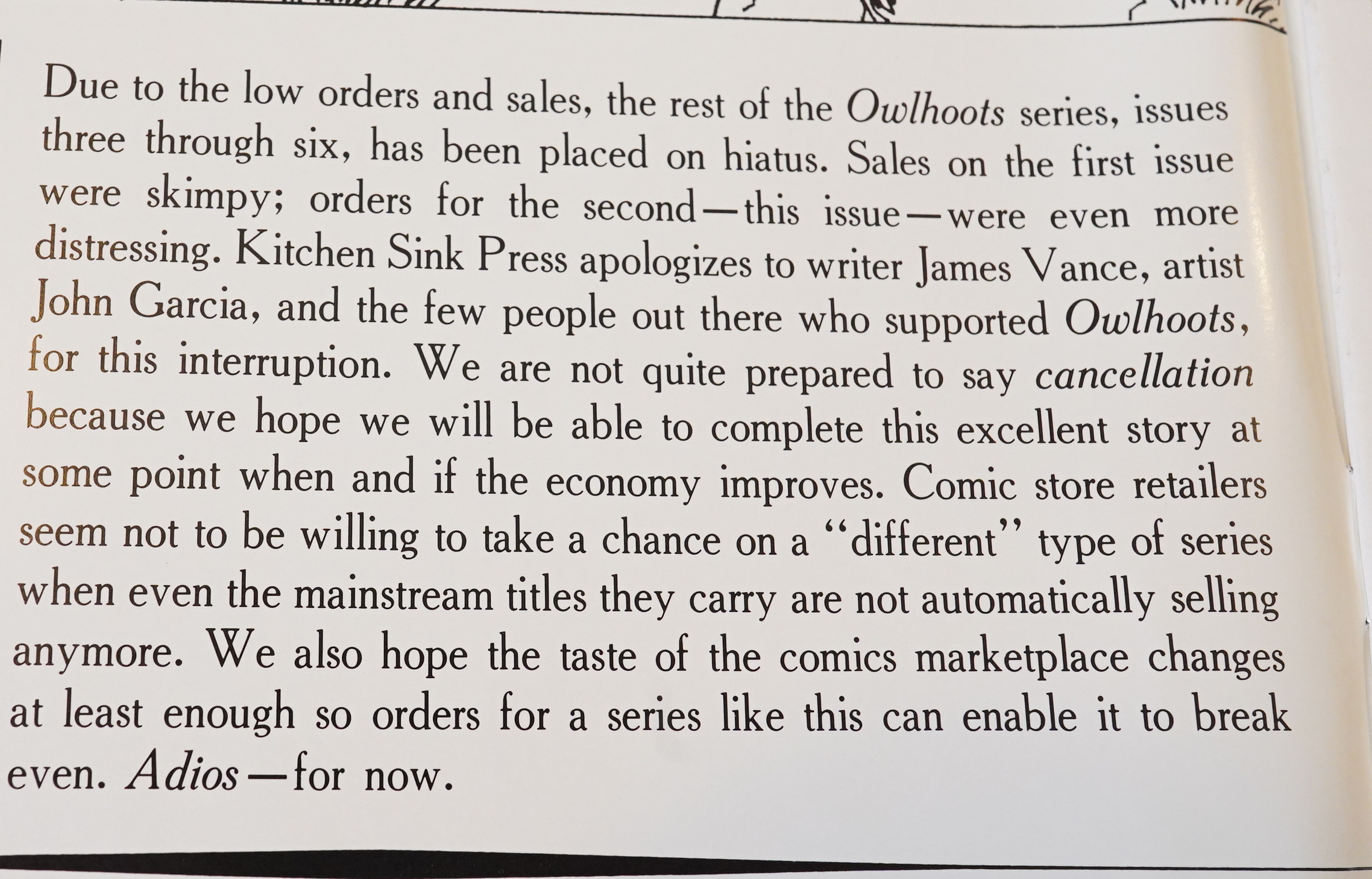

In the second issue, we’re told that the series is cancelled — the surprising thing is that they even published the second issue, but Kitchen Sink is nice that way.

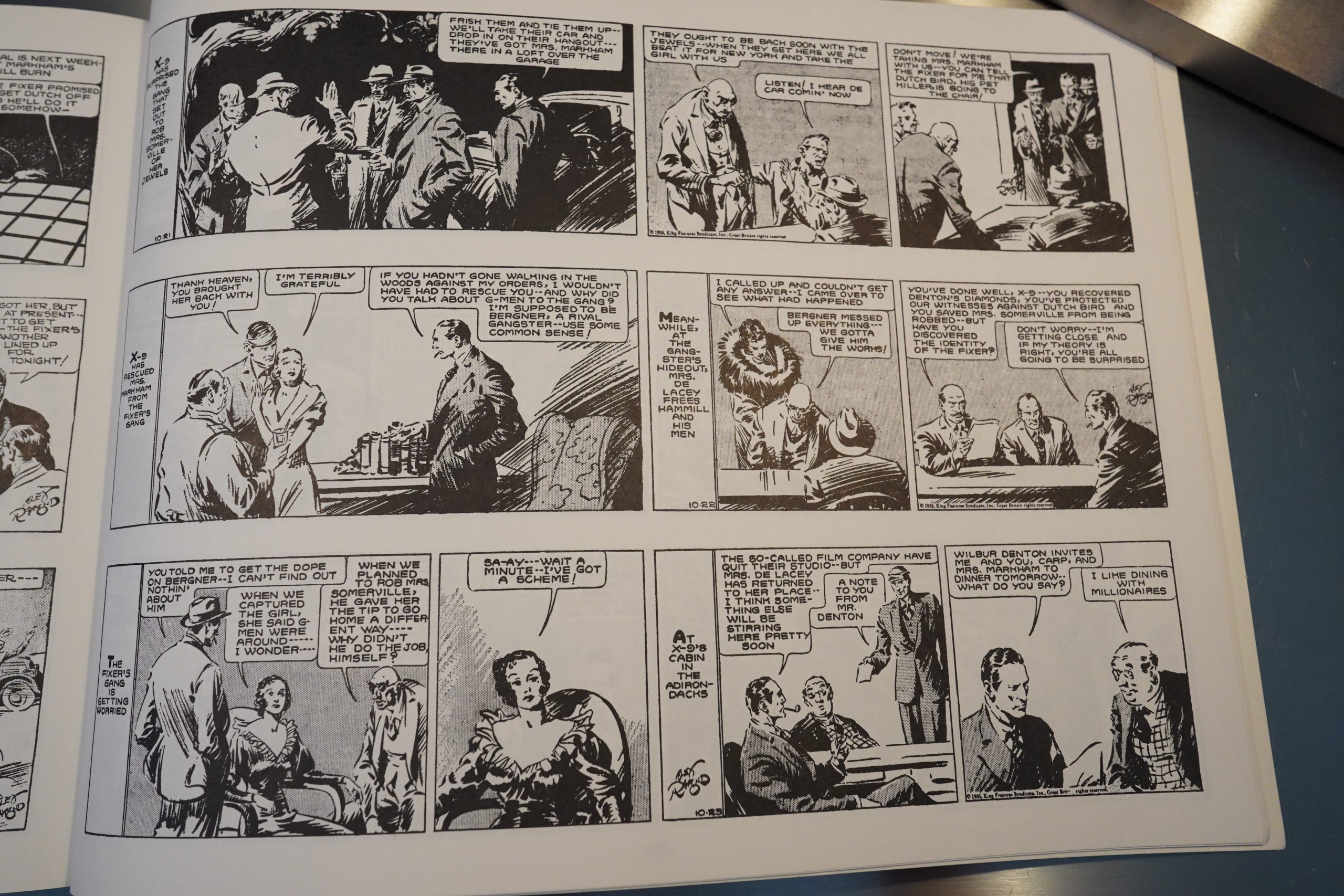

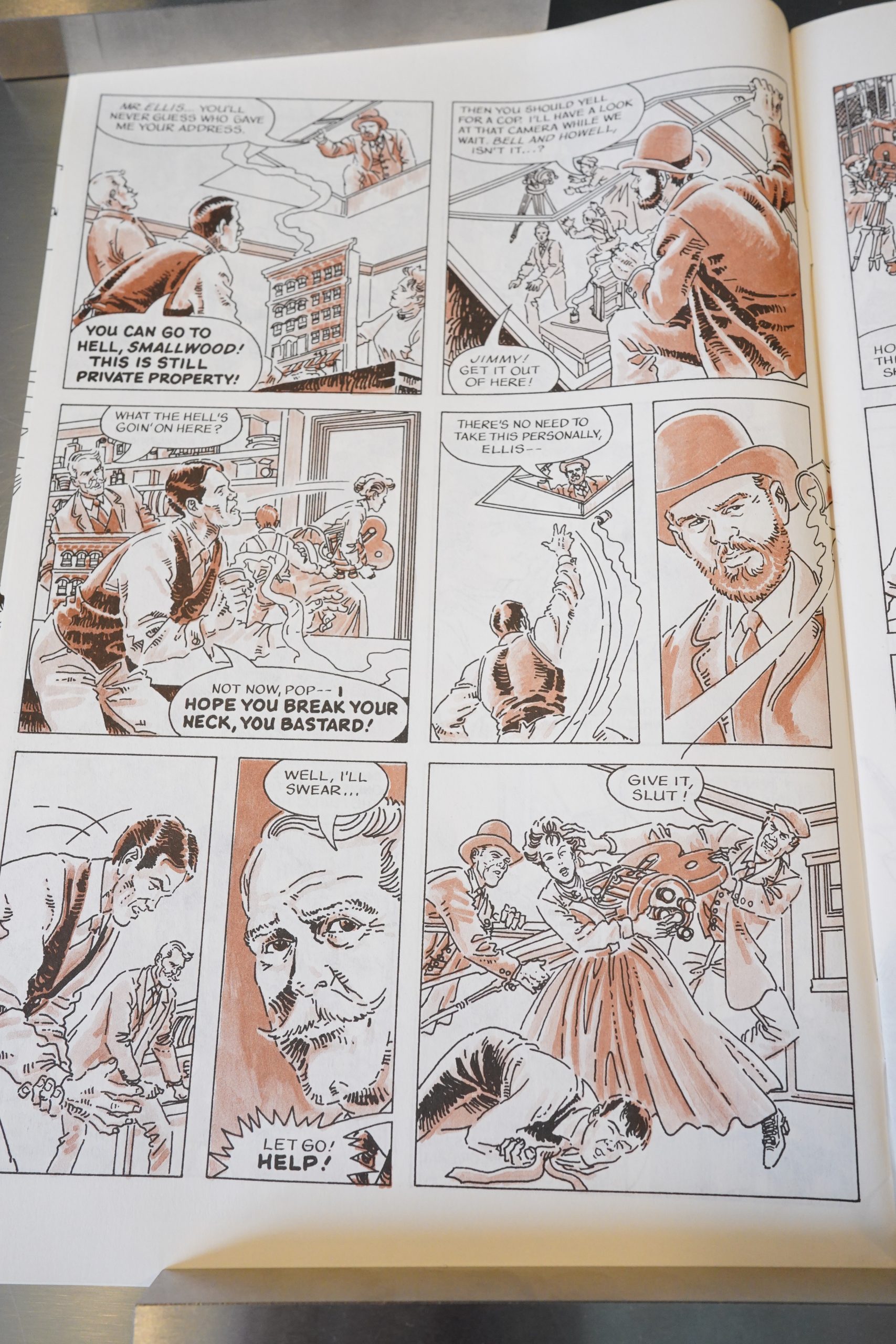

The storytelling is just so weak: OK, here it looks like that guy is… throwing a cup of steaming coffee up through the skylight at that guy in the bowler hat? And then it sort of makes a parabola around the guy? How does that even work from a geometry point of view? And then the guy throwing the coffee apparently has a heart attack? And the woman who was on the other side of the table, running out a door, is now suddenly back with the heart attack guy, and the table is gone?

Nothing in this blocking makes any sort of obvious sense: It’s just one badly composed panel after another that have little relation to the previous panel.

(Oh, and it’s not actually a cup of coffee: It’s a fire making er thing, and I guess he burned his hand — but only after throwing it? And that made him hurt so much that he had to crawl on the floor?)

Googling this book, it seems like it’s never been continued or collected.

But here’s a review:

A little talky, a little slow, but engaging and thoughtful. The loose, sepia-toned artwork by John Garcia is reminiscent, appropriately enough, of Frederic Remington’s cowboy-and-cavalry newspaper and magazine line work.

Russell Freund writes in The Comics Journal #144, page 46:

itchen Sink has killed Owlhoots

with the second issue, placing it (in the

euphemistic argot of network TV) ‘ ‘on hiatus”

with hopeful mention of its (unlikely) return.

While this is not a great crime against art,

Owlhoots was a work of good, modest virtues:

a period milieu carefully evoked, a solid nar-

rative, a sense of history. If the characters were

two-dimensional, that gave them one dimension

more than those peopling the vast majority Of

comics. This decent, intelligent book’s milure

to reach its intended sixth issue says nothing

good about the state of the marketplace.

[…]

Of series when even the mainstream titles

that they carry are not automatically selling out

anymore,” the reasons for Owlhoots• failure are

not entirely extrinsic. The characterizations, at

least over two issues, are thin. McAlester is a

åirly standard aging western hero, familiar from

countless elegiac, fin de siecle westerns from

Ride the High Country to The Shootist (actual-

ly, he’s stiffer than the heroes of either of those

films). Clayton Ellist, the moviemaker, is a

Coarse, modern opportunist; and Smallwood,

the Trust agent, is dignified and formidable, in

predictable contrast to his crude-talking hench-

men. These people are all types, stock charac-

ters unlikely to surprise us; and while this lack

of dimension might not be an impediment to

commercial success in a Marvel or DC book

(indeed, it is probably a must), it weakens

Owlhoots’ claims to higher status.

I also question the use of sepia tinting. This

sort of thing is usually meant to heighten the

“old time” feel of something; but its effect, to

the extent that it has any at all, is only to distance

the reader and to vitiate the immediacy of the

story.

And then there’s the title. I have no idea what

it refers to, and it sounds silly. Some works of

popular art are cursed with tides so bad that they

are an affront to commerce. Certain movies

come to mind: Cattle Annie and Little Britches,

Eegah!, A Girl, a Guy and a Gob. As a title,

Owlhoots is in this class.

Still, this book deserved a chance. If com-

ics are to claim a larger share of the popular

audience, there must be room in the medium

for superior middlebrow entertainments, and

Owlhoots showed promise of being one of those.

It was too early to tell if the historical material

would have provided any particular insights or

developed any depth, or to know if the main

storyline would have made full use of the

possibilities of its early century setting. But

the two issues of Owlhoots, briskly paced by

James Vance and agreeably drawn in a feathery-

but-substantial, neo-Severin style by John Gar-

cia, opened up a world of possibilities.

Intelligent genre fiction survives by giving

one kind of readership the payoffs it craves,

while exploring thematic territory of interest to

readers of another sort (actually, the “readers

of another sort” generally dig the lowbrow

payoffs too, or they wouldn’t put up with the

stuff). This book could have filled the bill.

McAlester’s attempt to write his life story

in shadows opened up some interesting avenues.

This is the one hundred and seventeenth post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.