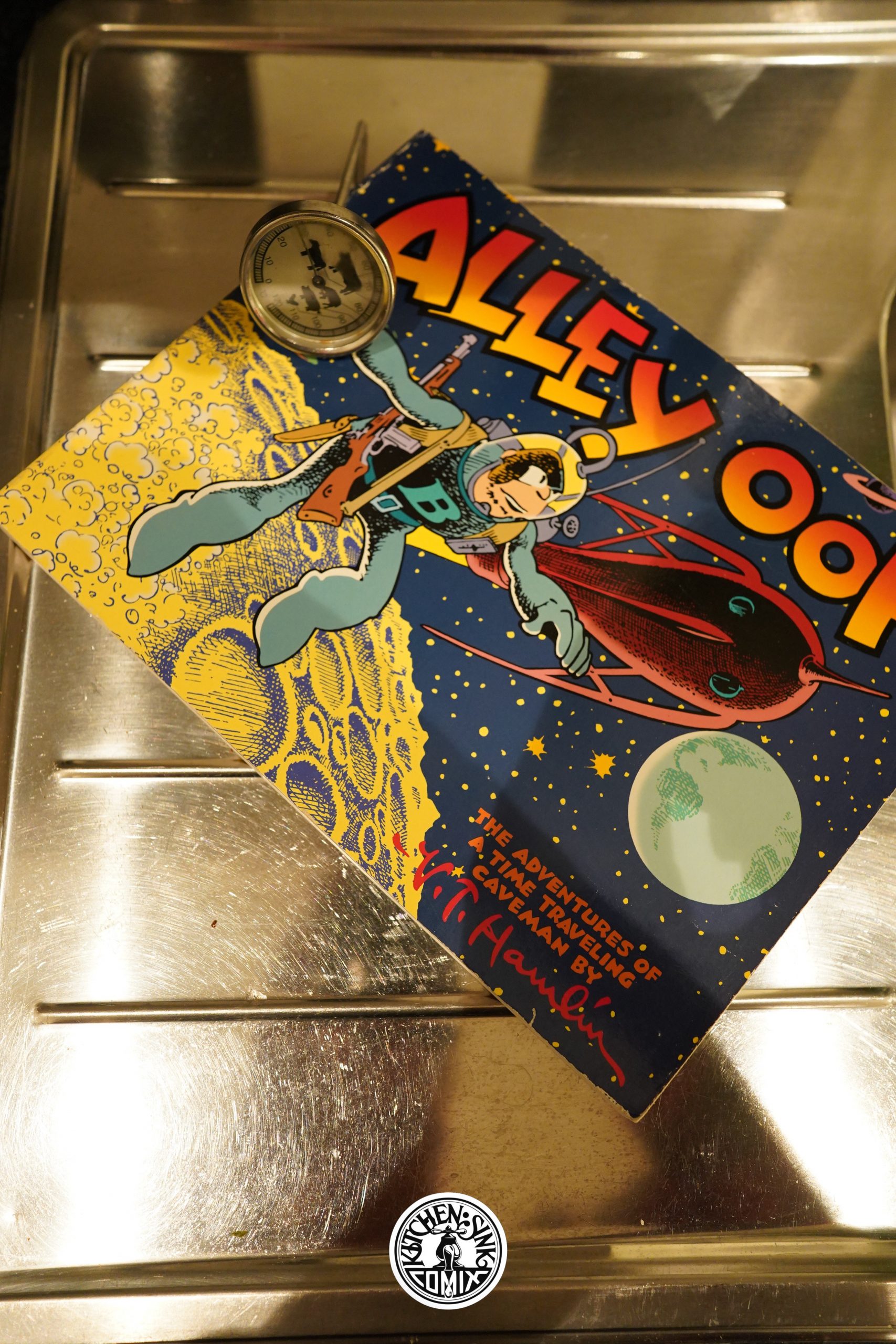

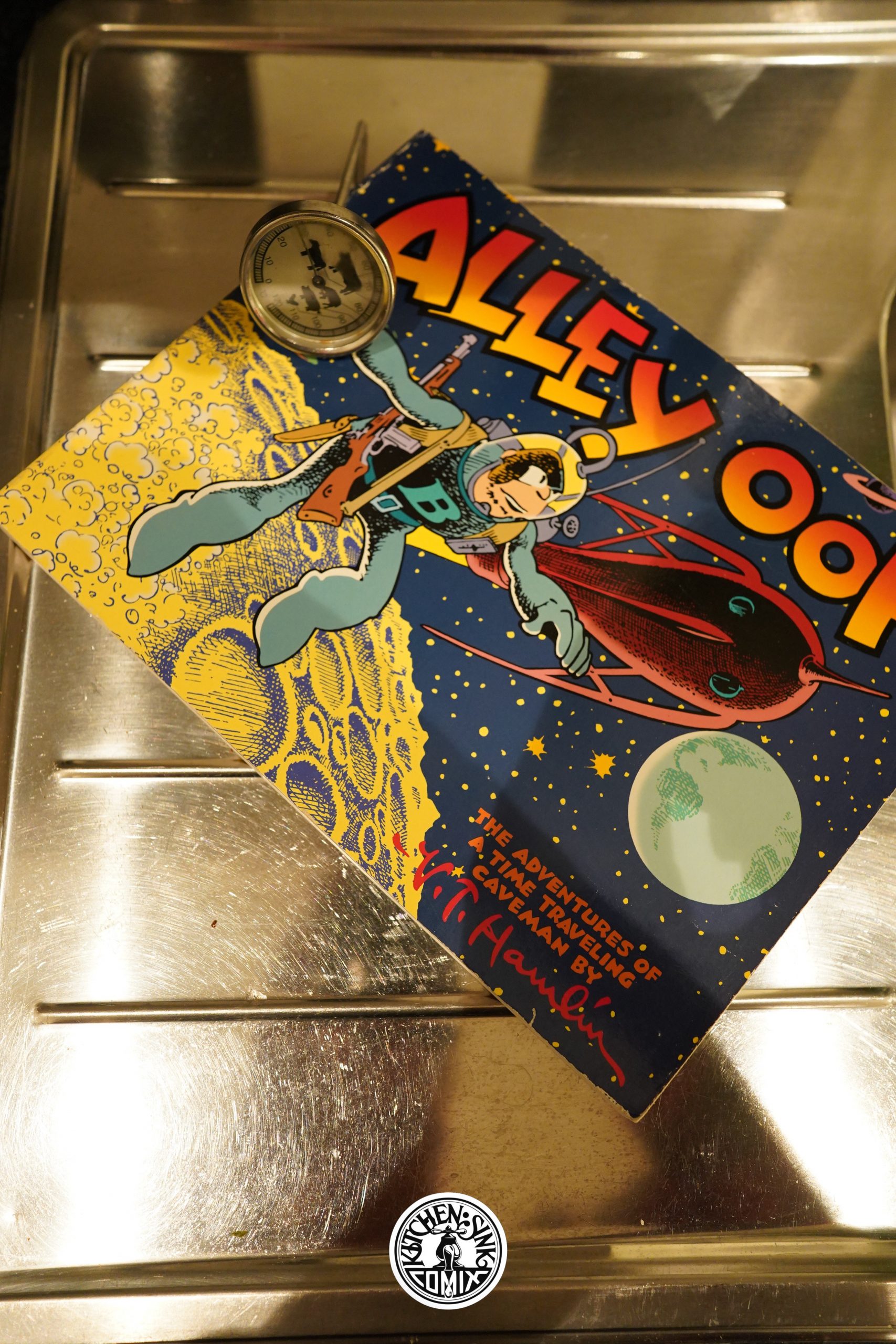

Alley Oop (1990) #1-3 by V. T. Hamlin

Oops. I forgot to buy the first two volumes of this.

Alley Oop is one of those oddball series I’d see in various comic strip anthologies as a child. (Cheap reprints of American and British comic strips used to be a big deal in Scandinavia, and I think there’s still a monthly Agent X-9 going in Sweden (doing Modesty Blaise and Agent Corrigan and all that stuff).) I don’t think it was ever that popular with anybody, because while we’d get one story Rip Kirby after another, we’d get an Alley Oop serial once in a blue moon, as far as I can recall.

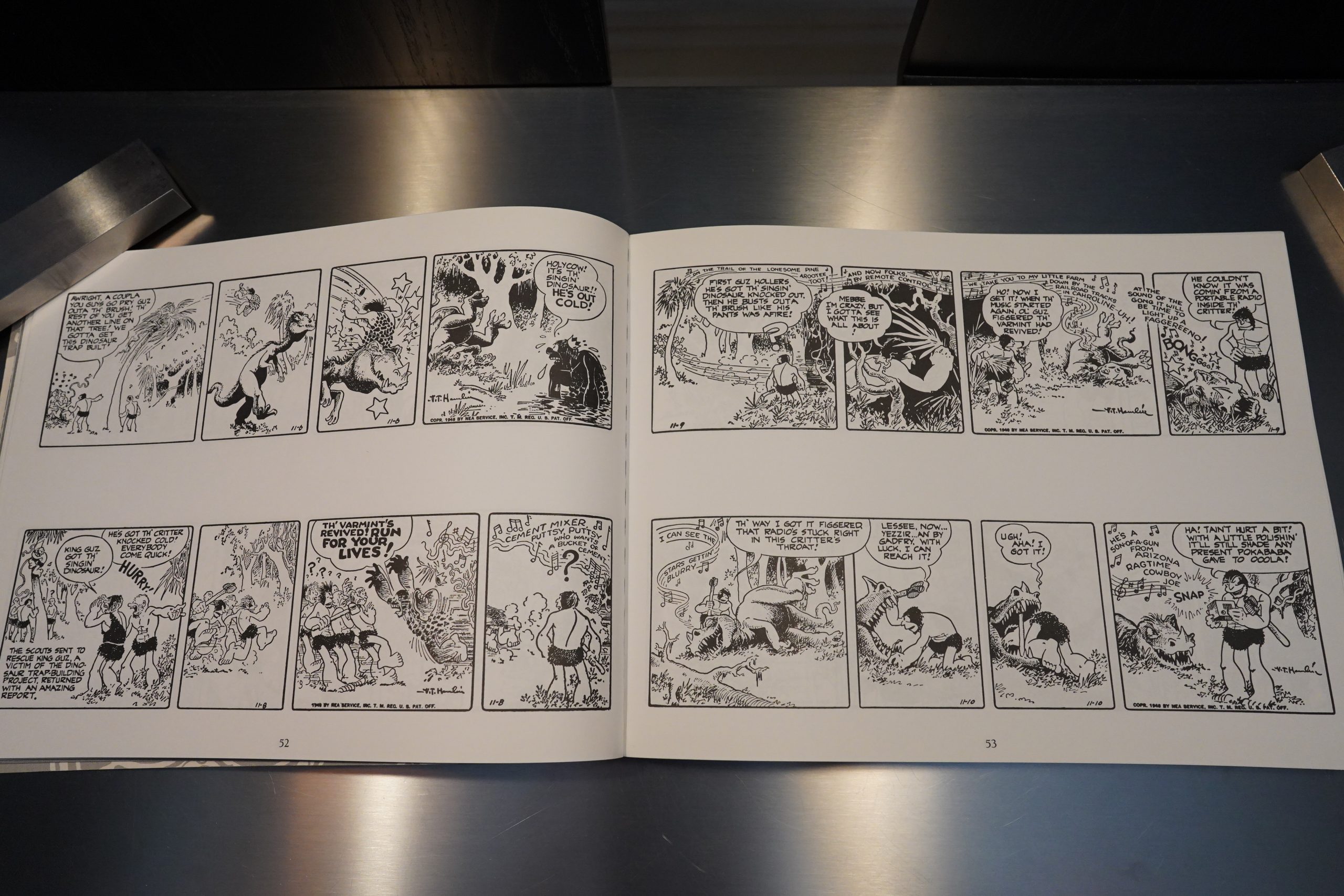

Perhaps one problem is the basic visual disconnect: The protagonist is a cartoony caveman, but the stories are basically sci-fi time travel adventure stories, and not zany humour things?

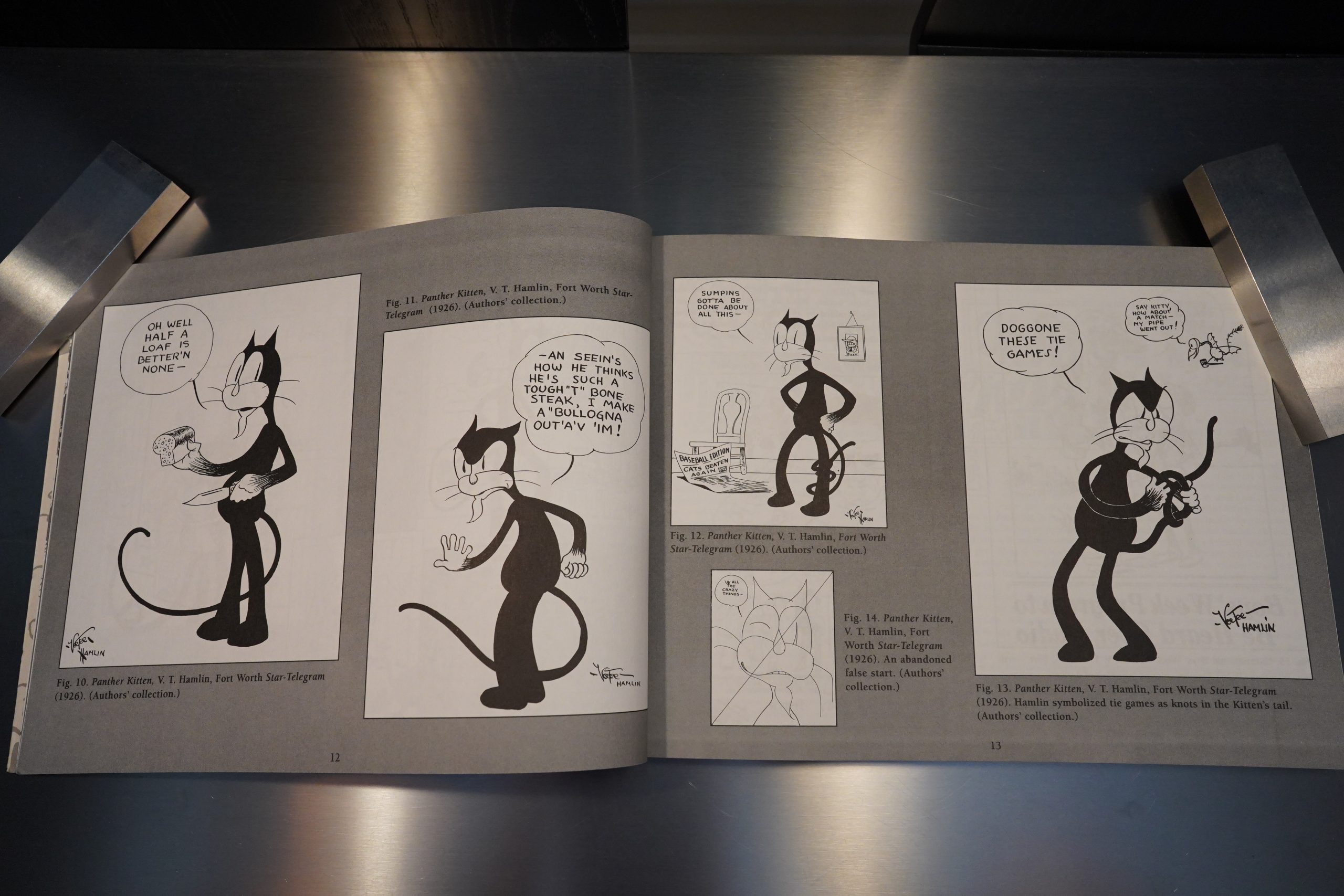

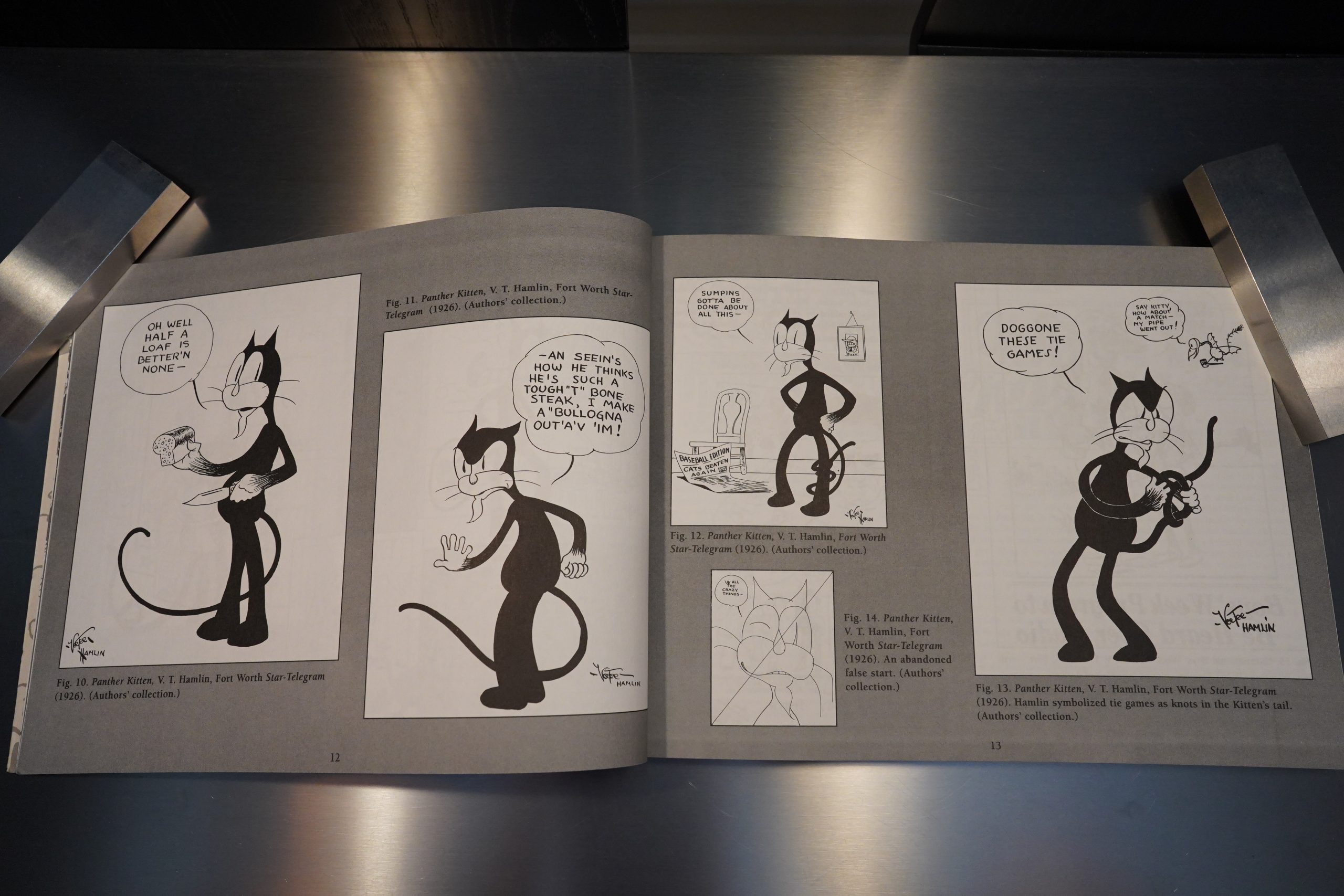

This book starts off with 20 pages of essays and pre-Alley Oop artwork from Hamlin.

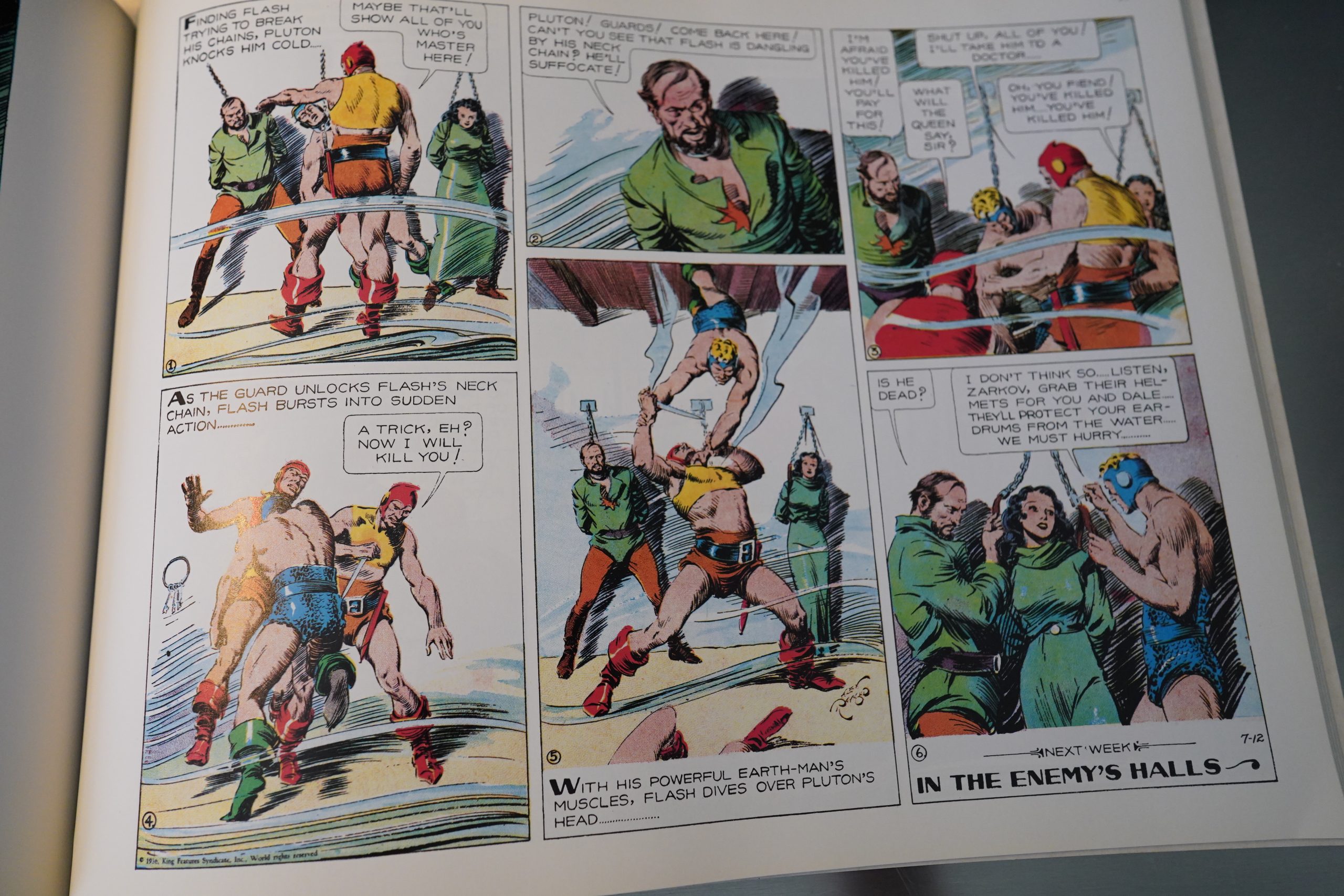

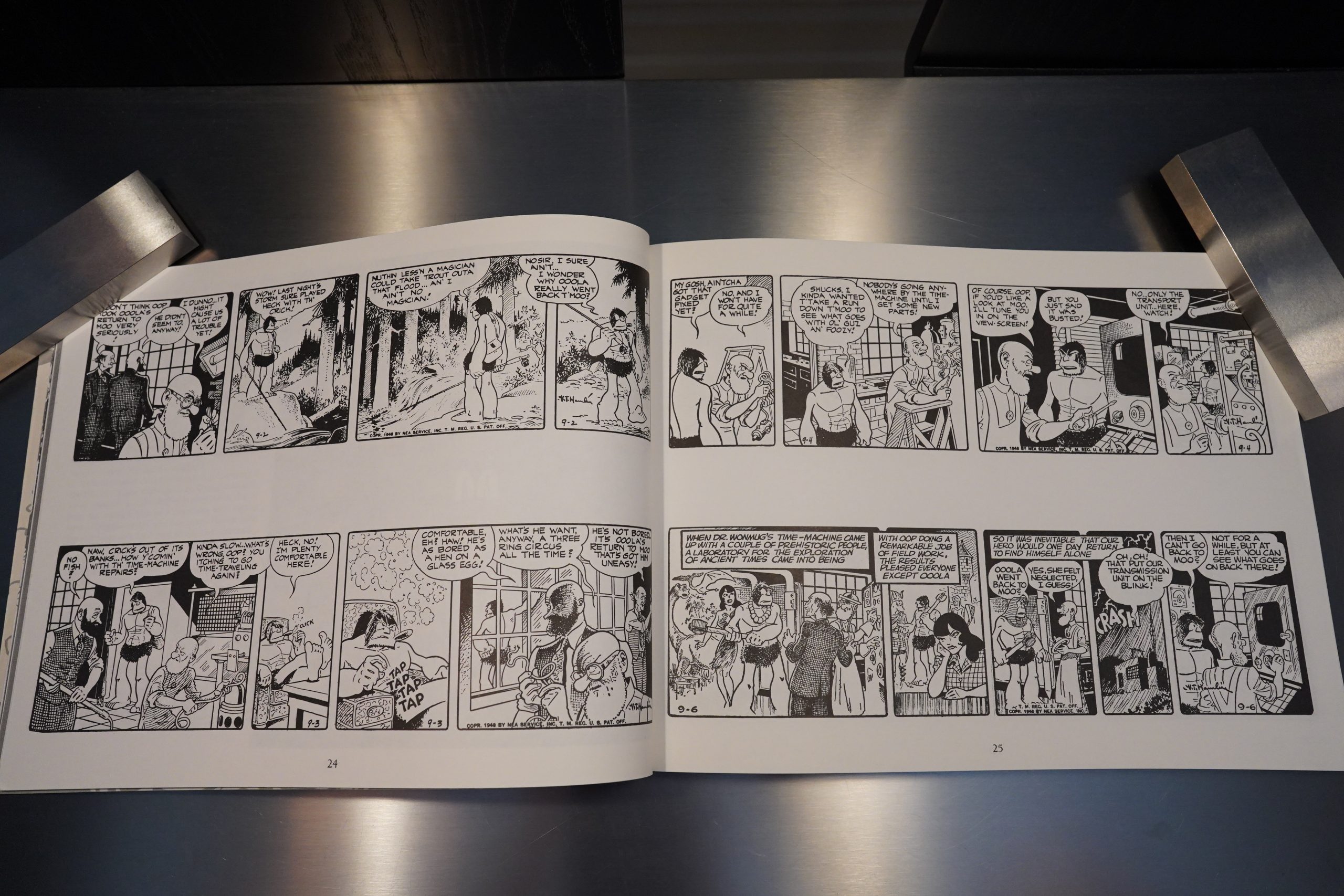

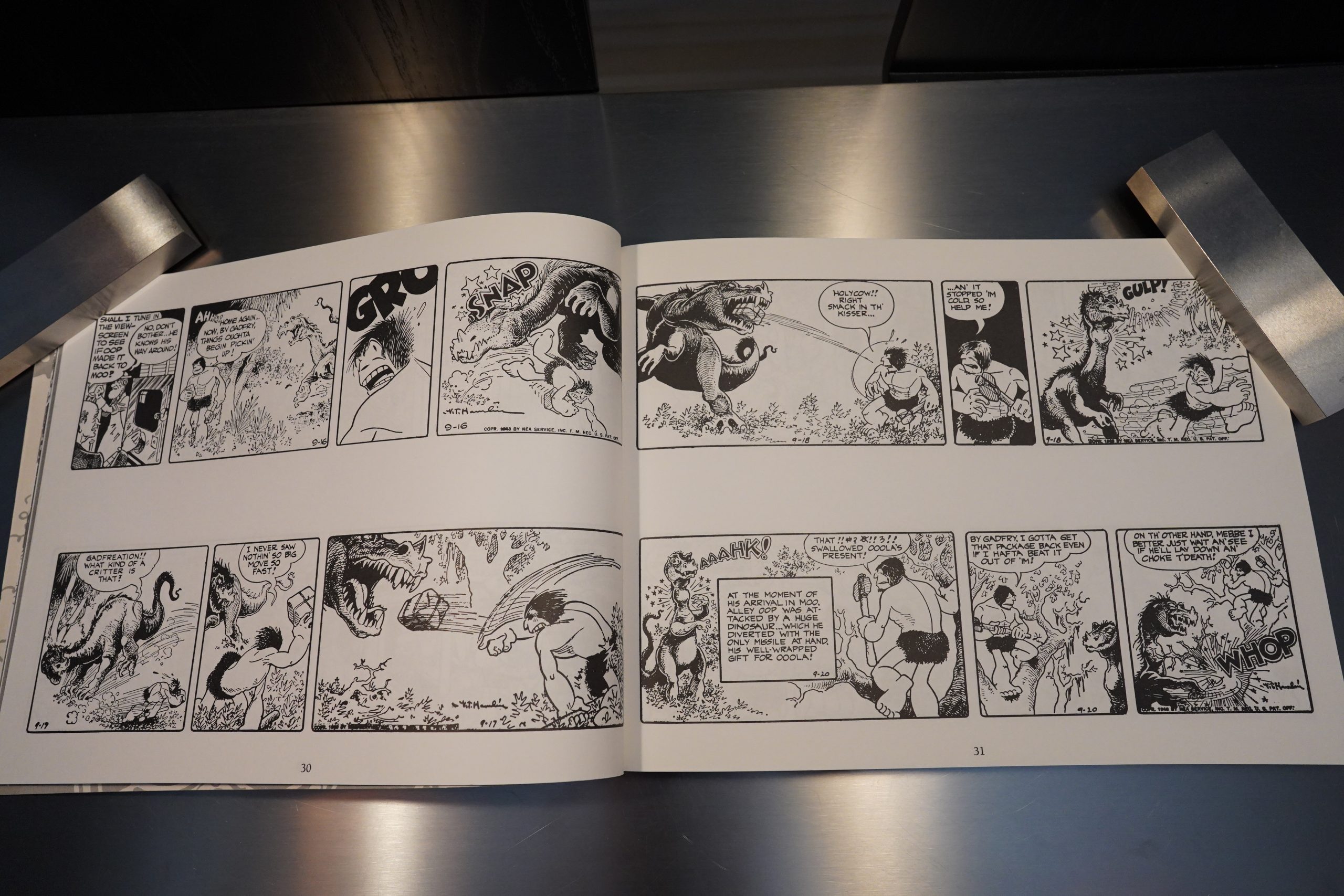

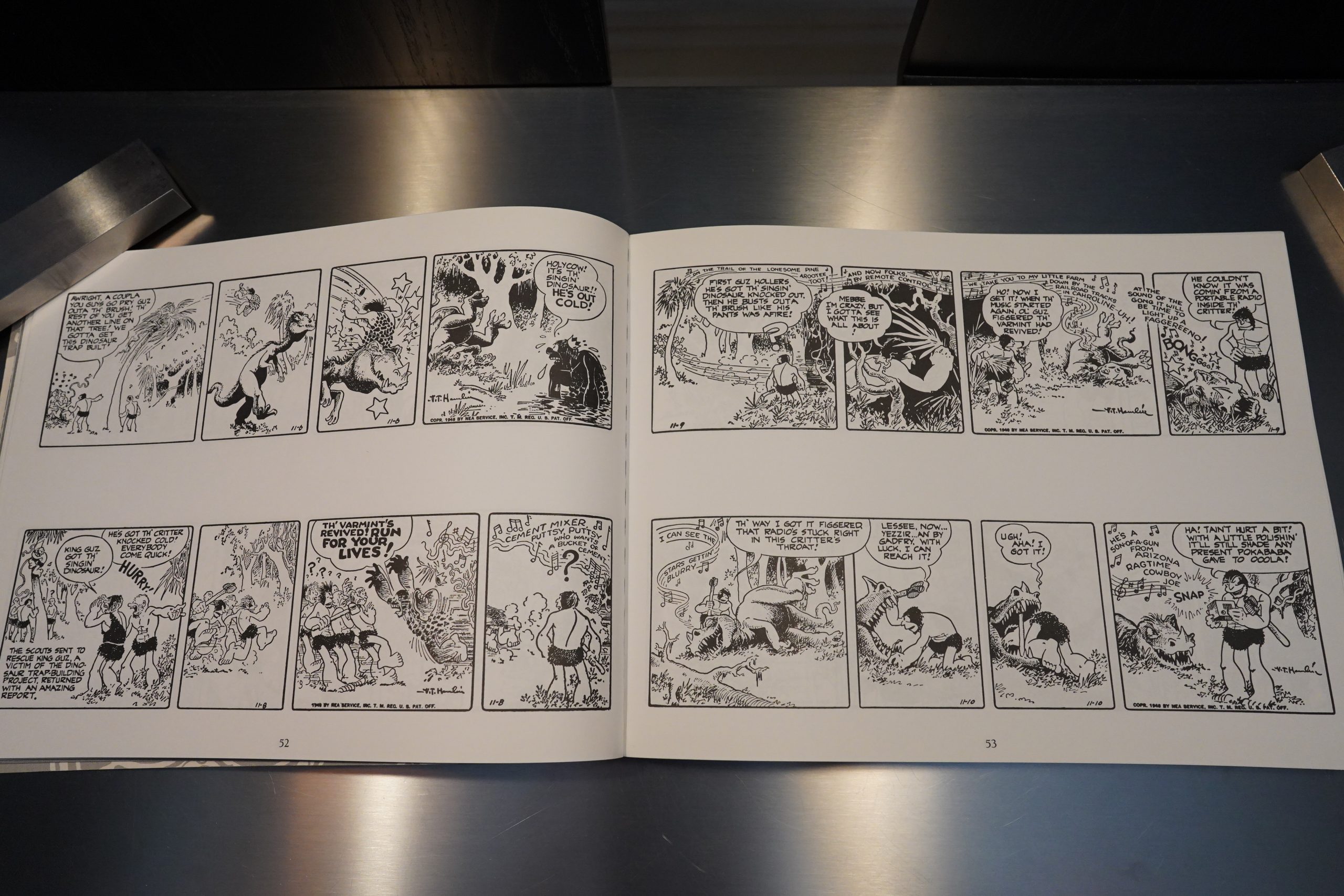

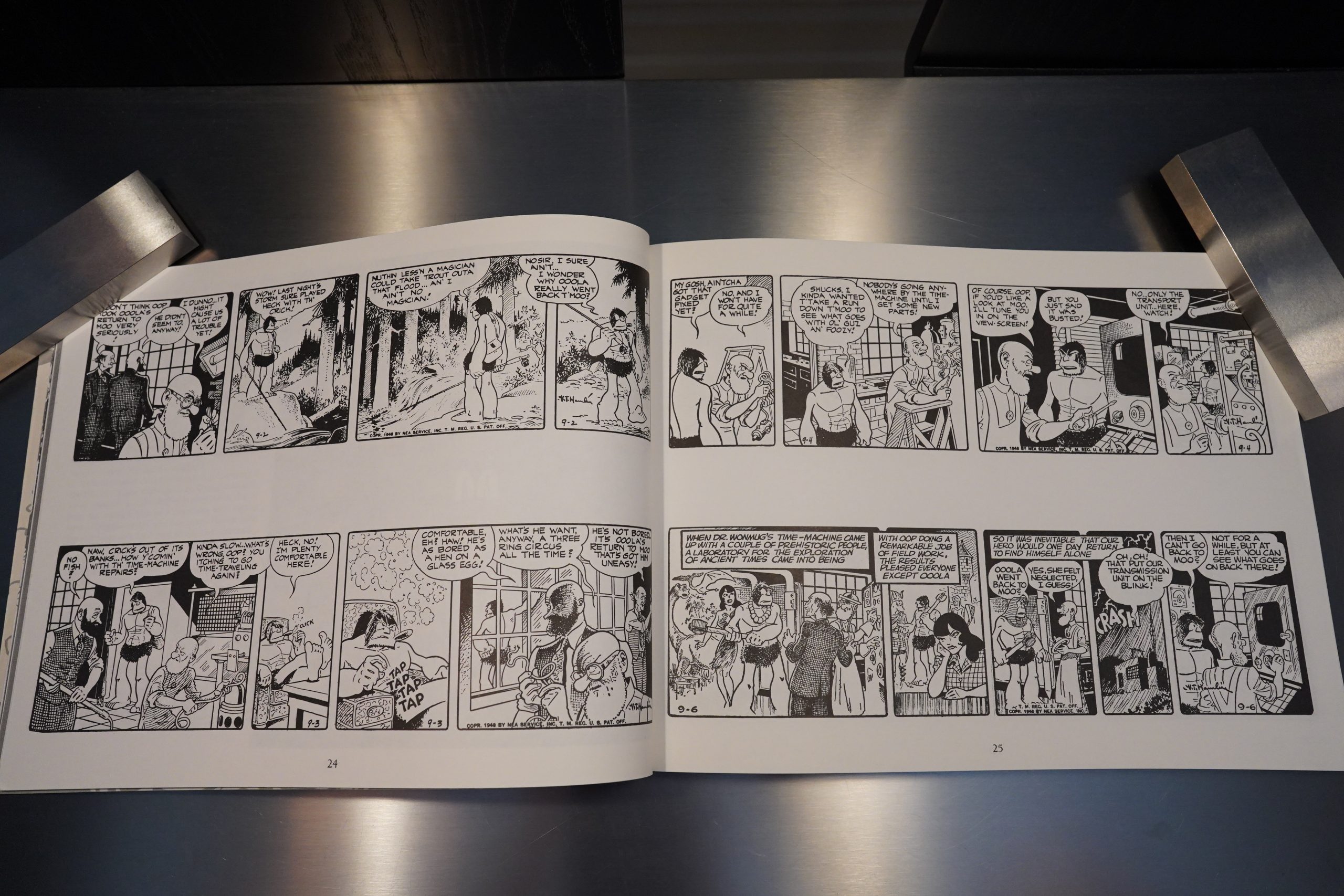

Ah, right. The strip is very chatty — people are explaining everything to everybody else all the time, so as a reader, you get the same information over and over and over again.

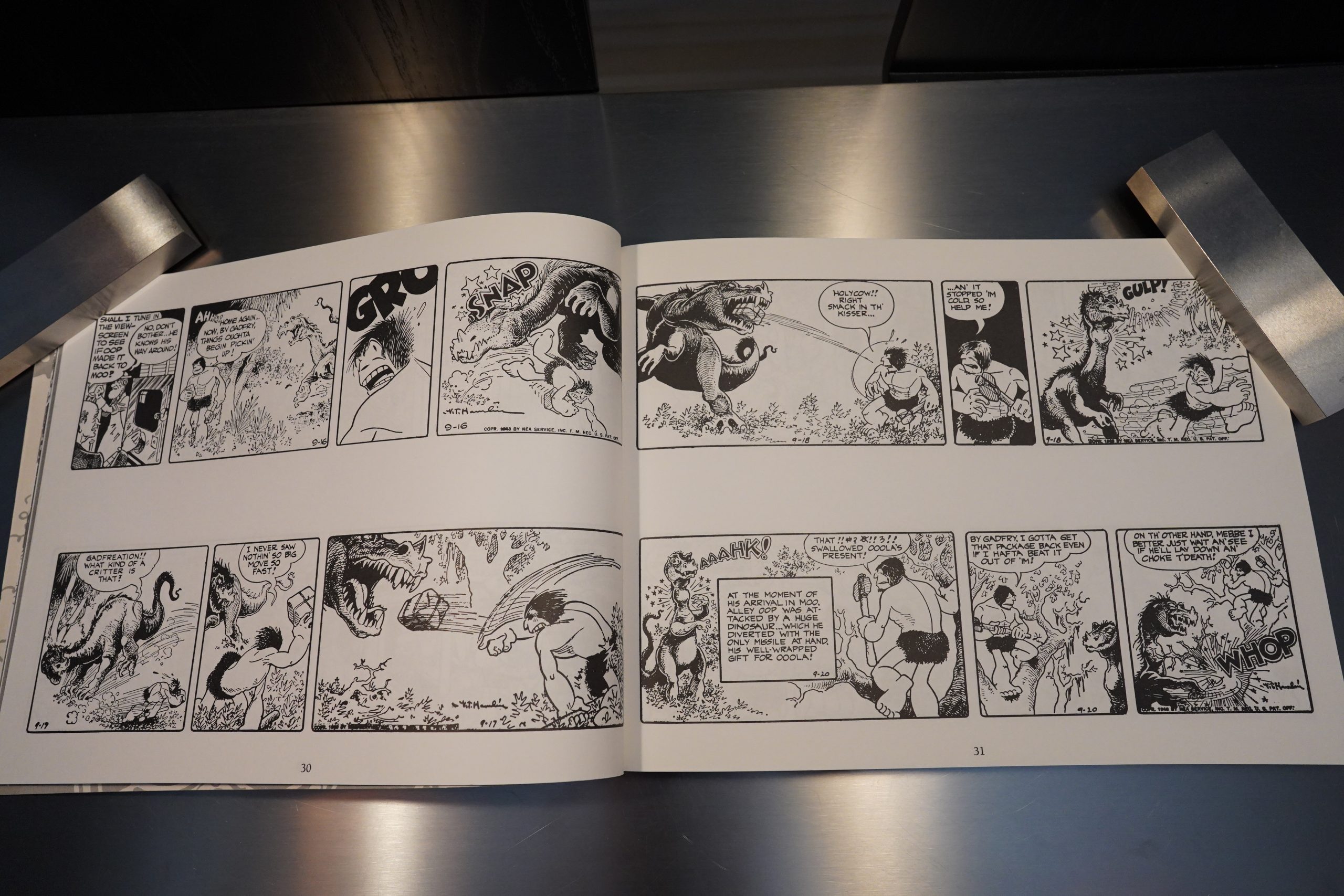

There’s some fun action scenes, though.

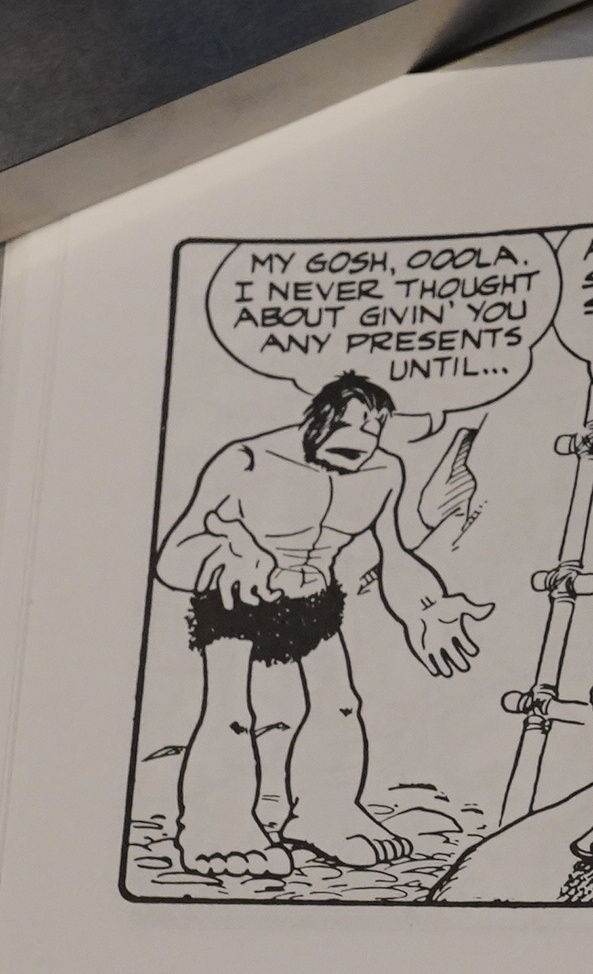

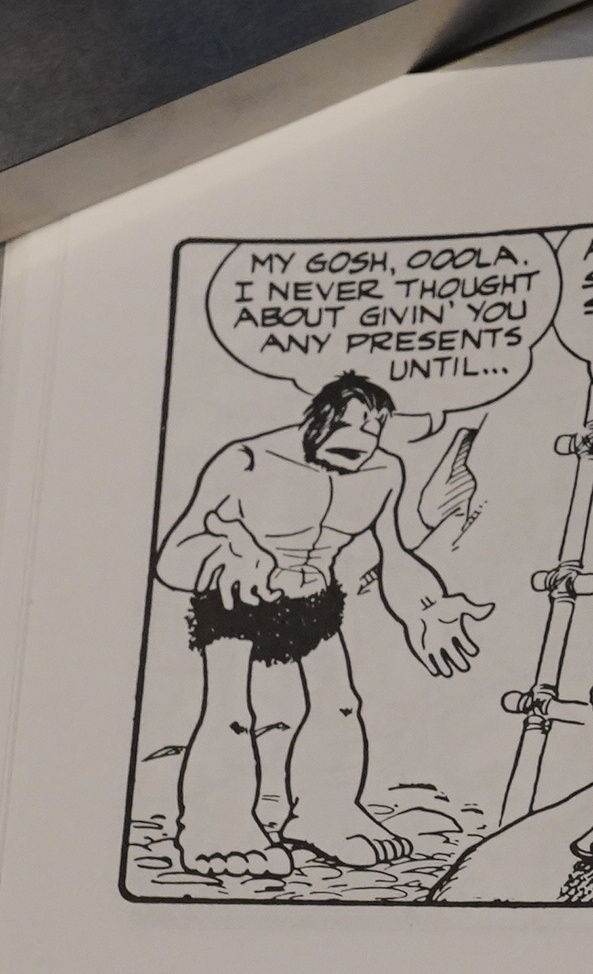

There’s something disturbing about how Hamlin draws the cave-man characters: How does those thighs connect up to the torso anyway? The gap between the thighs is wider than the thighs themselves, and the little furry shorts are so small that there isn’t space for… anything.

Deeply disturbing!

And… reading this, it’s clear both why editors back in the 70s tried to incorporate this strip into the strip reprint collections, and why it never worked well. Because this seems like it should be a breezy, fun, action-filled series, but instead nothing happens. But in a noisy sort of way. The first sequence is 40 or 60 pages long (depending on how you count), and it’s just the same over and over again. How many times did they fight that dinosaur? How many panels did Alley Oop spend fretting about his girlfriend?

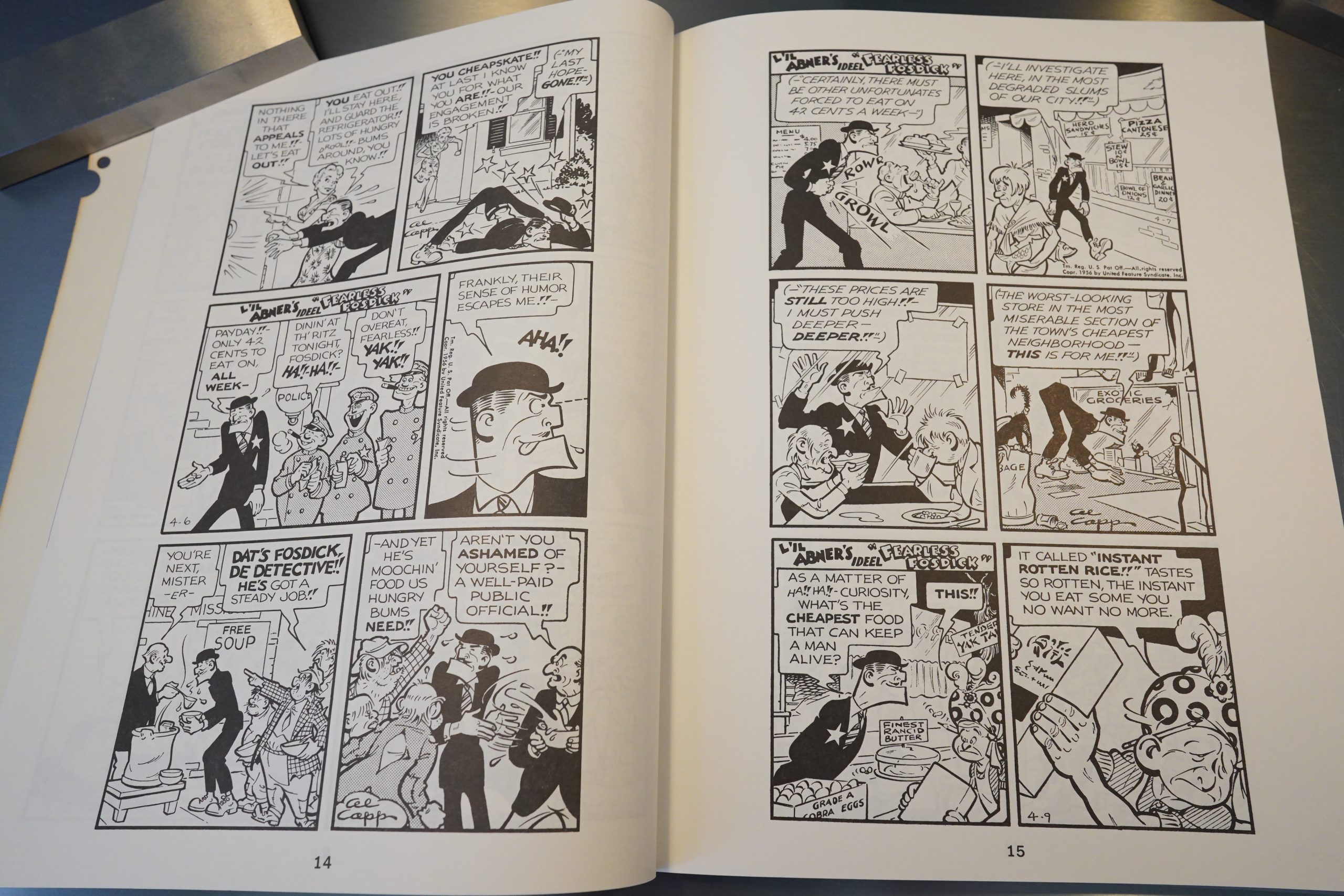

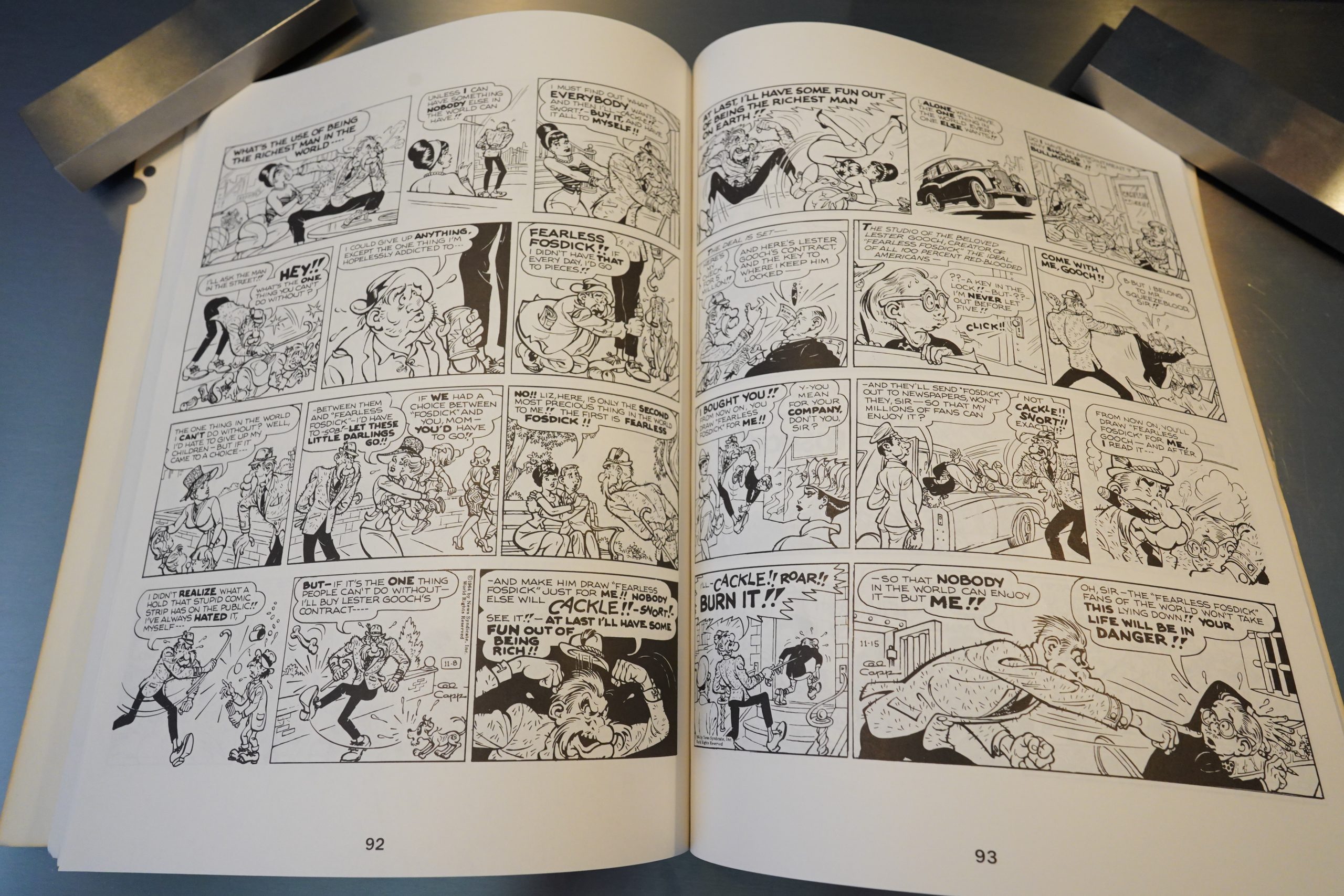

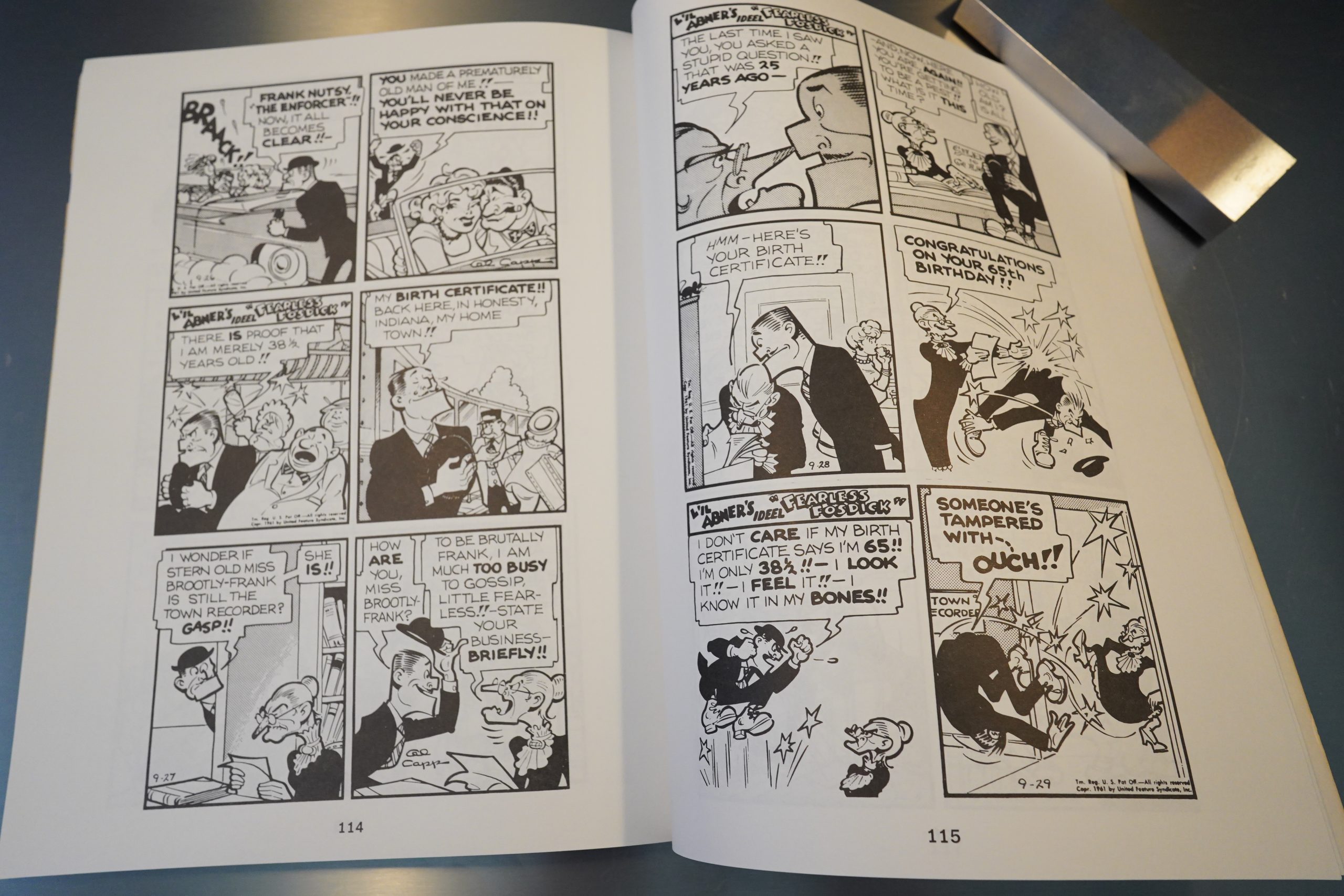

It’s just frustrating to read, and I’m not surprised that Kitchen Sink only managed to publish three of these collections before cancelling the series. Which is quite unusual for Kitchen Sink — they published thousand and thousands of pages of The Spirit, Steve Canyon, Lil Abner, and so on, but I guess nobody wanted to buy Alley Oop.

R C Harvey writes in The Comics Journal #200, page 33:

The strip Hamlin produced is unique,

unequalled in the history of the medium.

Couplingdramaticstowtellingtoa cartoony

style, he told rousing stories— high-spir-

ited adventure tales that bristled with plenty

of action and suspense, not to mention

comedy and genuine human interest. And

the greatest source of the latter is Oop

himself, an intriguing creation —a charac-

ter whose limited range Hamlin success-

fully expanded to serve the all-purpose

needs of heroic adventuring.

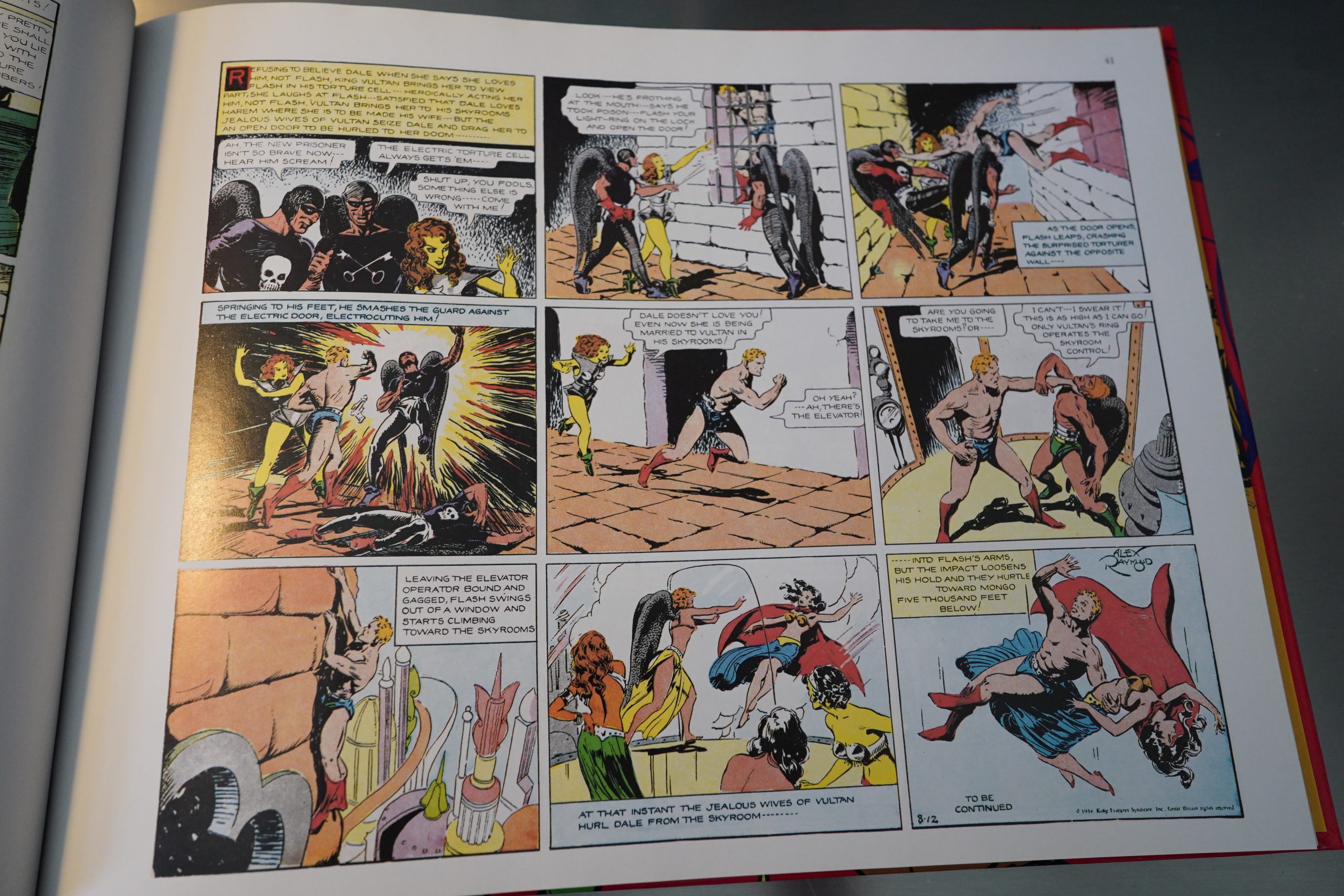

Alley Oop of the early strips is an ob-

streperous, truculent, club-wielding cave-

man. And if he isn’t actually looking for a

fight everywhere he goes, he nonetheless

finds one nearly everywhere. Not only does

he have the prickly disposition of a brawler,

he has the appearance of a strong man.

Hamlin gave his caveman a great barrel

chest and a bewhiskered bullet-head with

no neck (and no ears), and then he used the

same device that E. C. Segar had used in

showing Popeye’s strength. Instead Of mak-

ing OOP’s biceps bulge with power, Hamlin

bunched his hero’s muscles right behind his

fists in ballooning forearms, a graphic ploy

that gave ham-fisted a visual metaphor.

Although Oop is occasionally bested mo-

mentarily, he almost always triumphs at

feats requiring physical strength or, later,

military cunning. Pugnacious and cranky—

even somewhat peevish — he is quite un-

flappable ina crisis. Unflappable and nearly

invincible — and therefore virtually uncon-

trollable. Only Ooola can control him.

Ooola is a genuine hard case. Although

she is beautiful (and Hamlin’s treatment

Of her costumes always reveals rather

than conceals her figure). she is not at all

feminine in the traditional cringing man-

ner of an adventure tale’s damsel in dis-

tress. Ooola can think rings around Oop,

and if she can’t control him by out-smart-

ing him, she resorts to a swift right hook,

which she can deploy as effectively as Oop

can his stone-age axe.

[…]

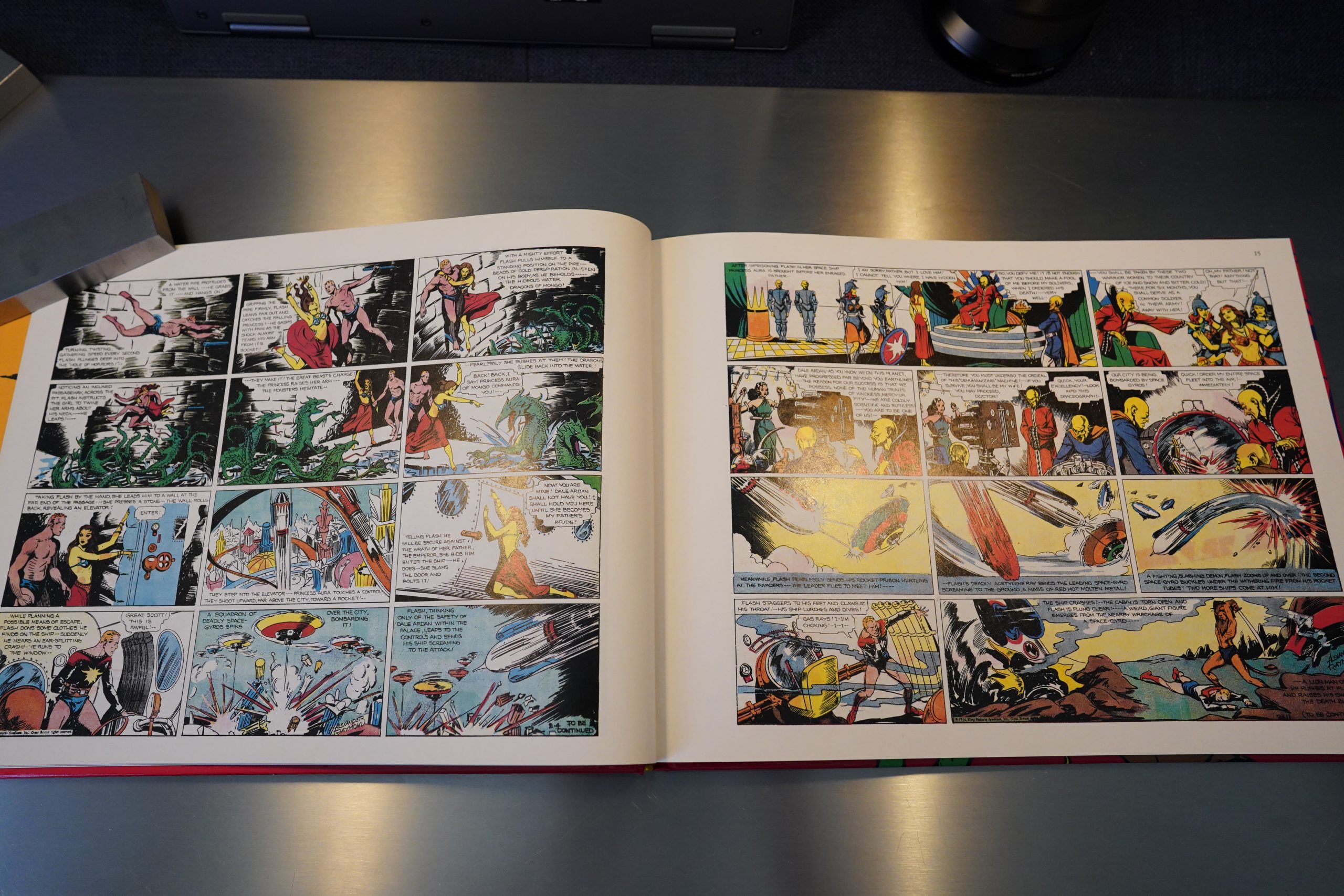

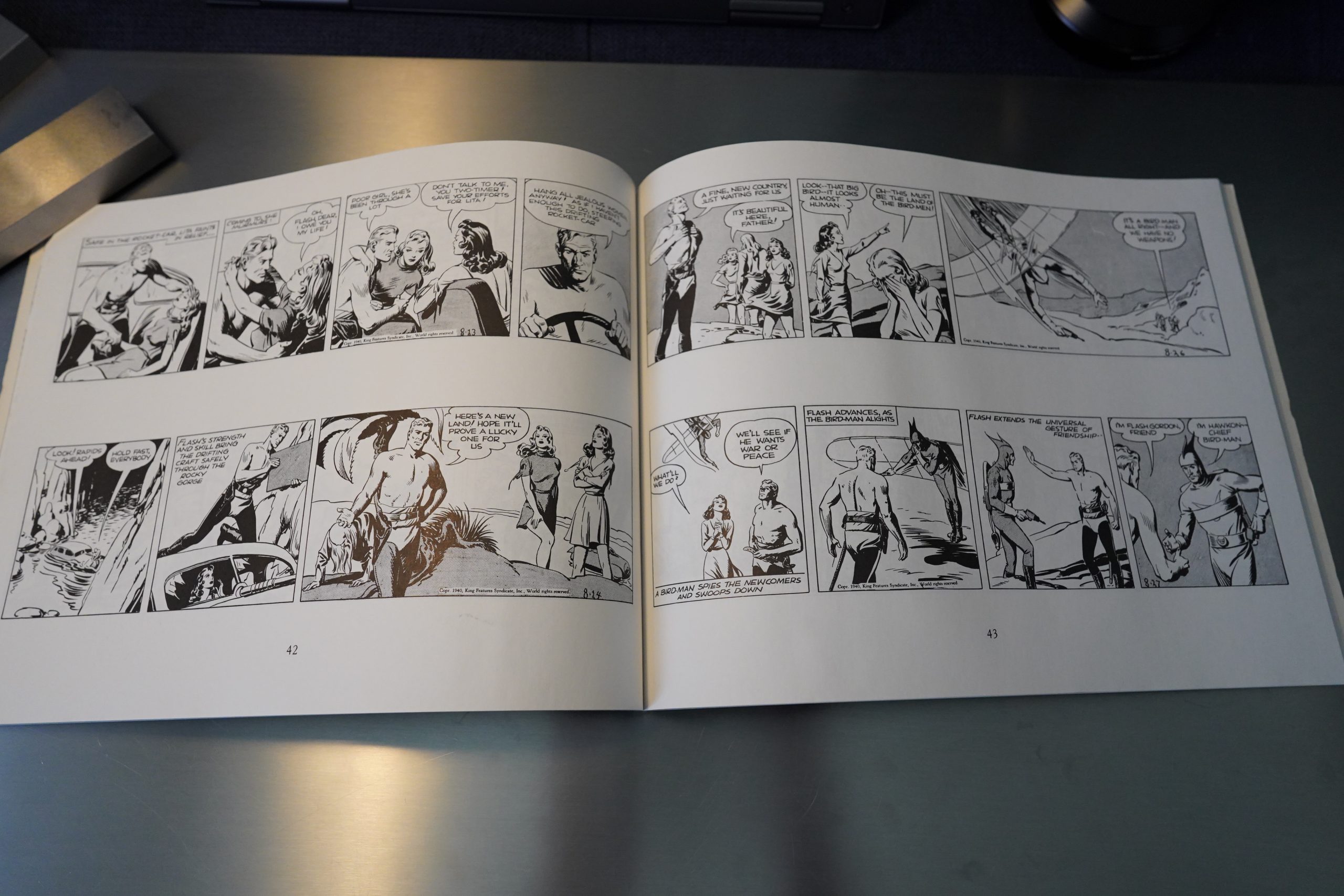

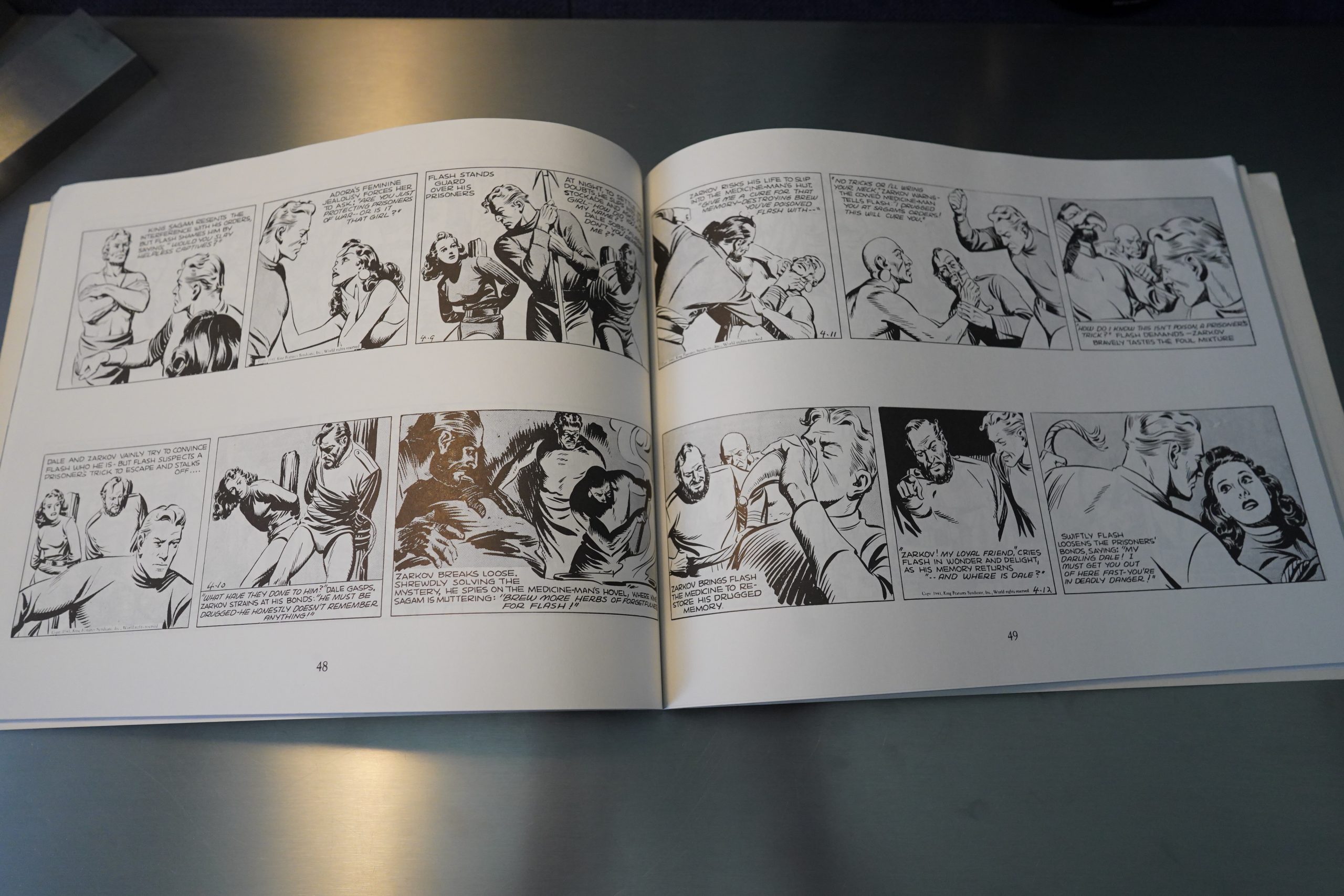

Hamlin clearly designed his daily

strips as single works of art not as

aggregations of so many panels per

day. Sometimes one panel plays off the

next, the drawing in one crossing the

intervening gap to precipitate the ac•

tion in the second. He also frequently

achieved a panoramic effect, breaking

a single scene in two with a panel

border to give the reader two narrative

focal points in one sweeping picture.

And he was sometimes just plain playful —

the tail of a speech balloon converted to

cigar smoke when Oop, smoldering in sup-

pressed anger, mutters a dire prediction.

And the Kitchen Sink volumes show•

case Hamlin’s intricate graphic artistry

superbly. The production values are high

here (as we’ve come to expect from Kitchen

Sink): excellent reproduction from syndi-

cate proofs (loaned by Hamlin himself

while he was still alive). And running the

daily strips only two to each 8 1/2xl l-

inch page gives each strip and Hamlin’s

distinctive graphic treatment the ample

display space they deserve.

This is the one hundred and twelvth post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.