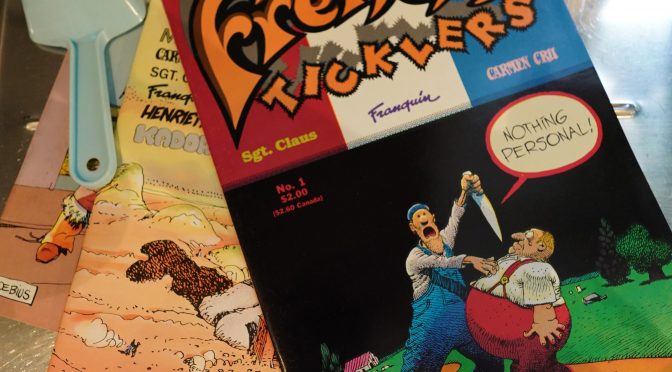

French Ticklers (1989) #1-3 edited by Randy & Jean-Marc Lofficier

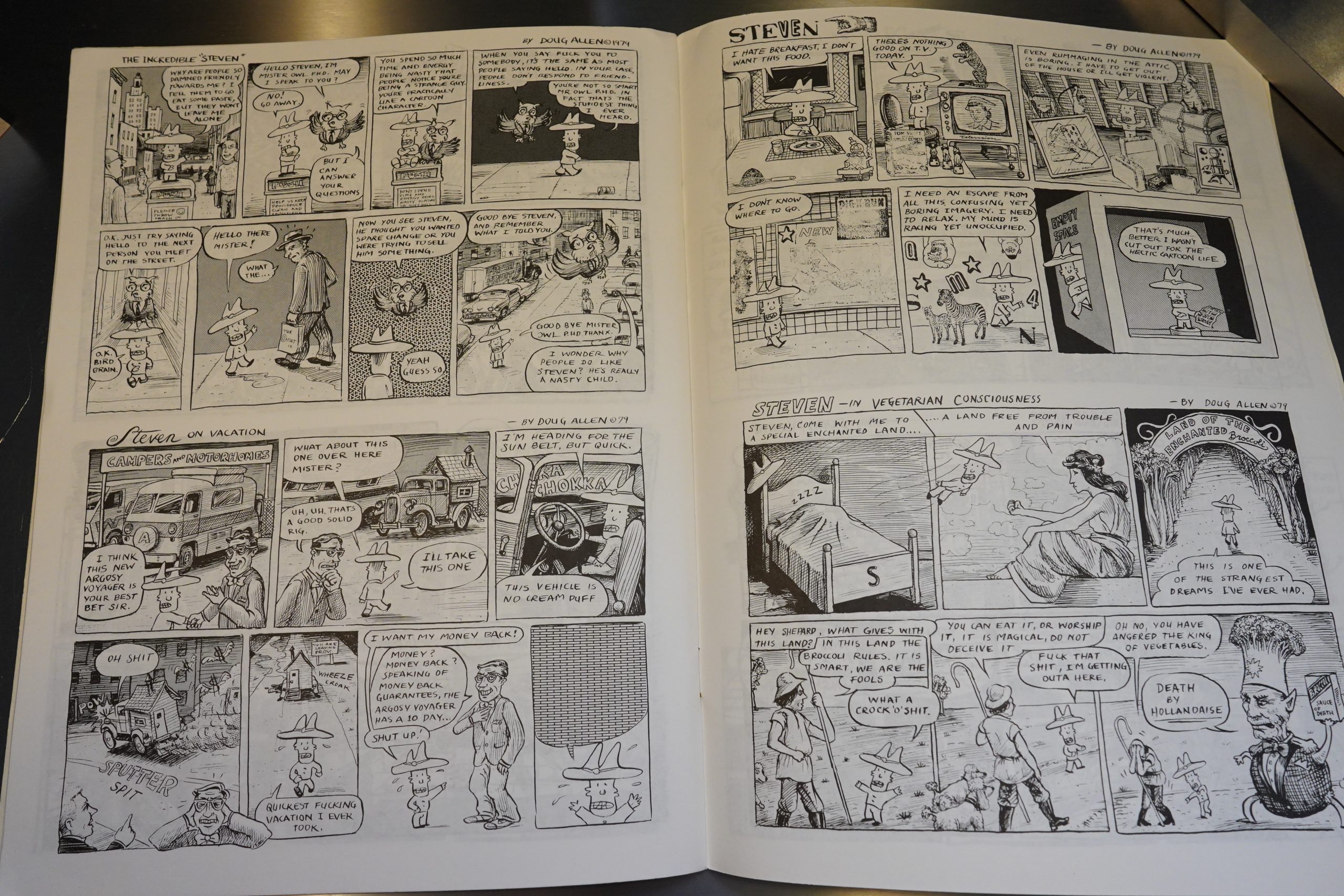

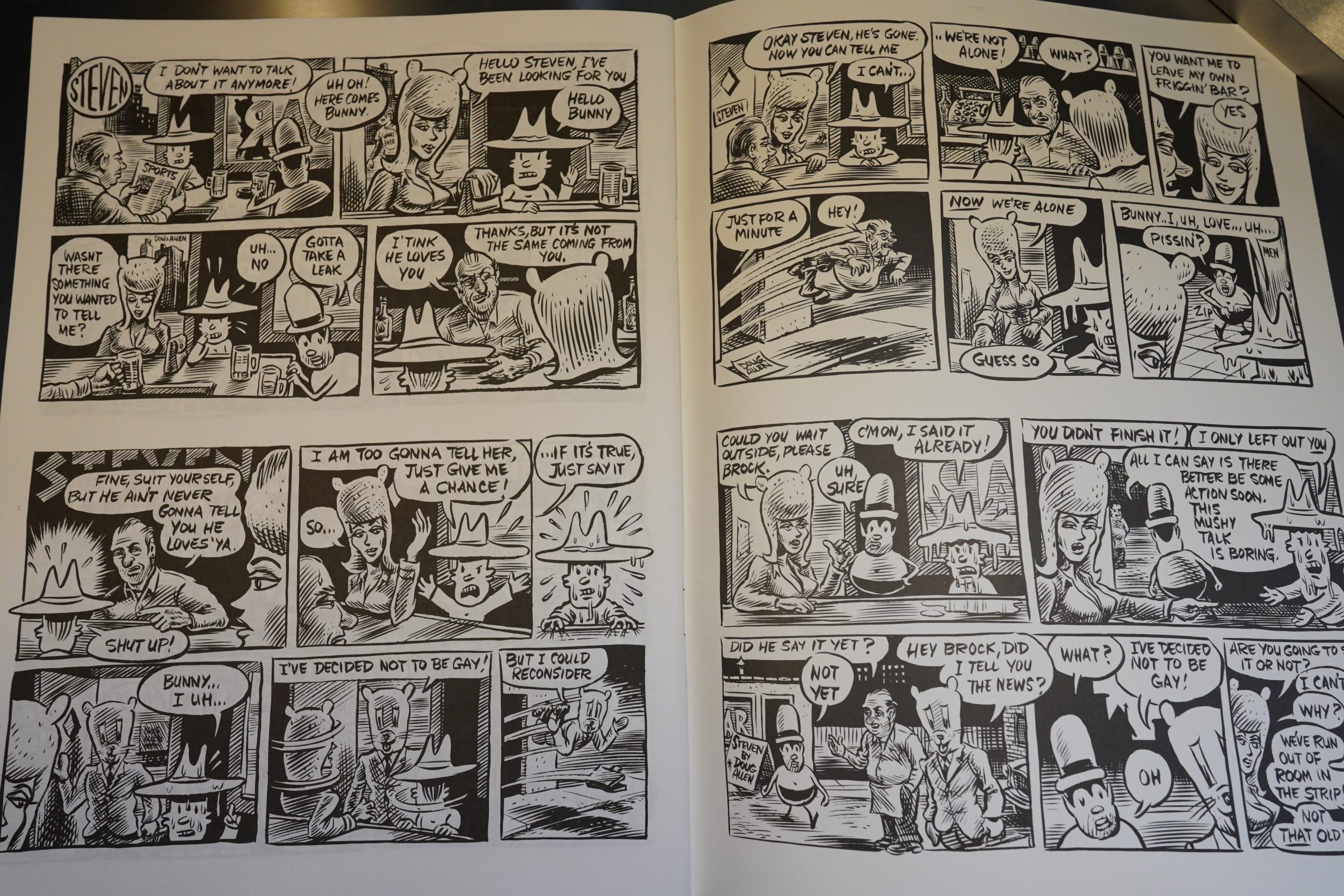

This anthology reprints stuff from the French humour anthology Fluide Glacial, which had previously been done by Renegade Press under the name French Ice. Which makes more sense, but I guess they couldn’t keep that name…

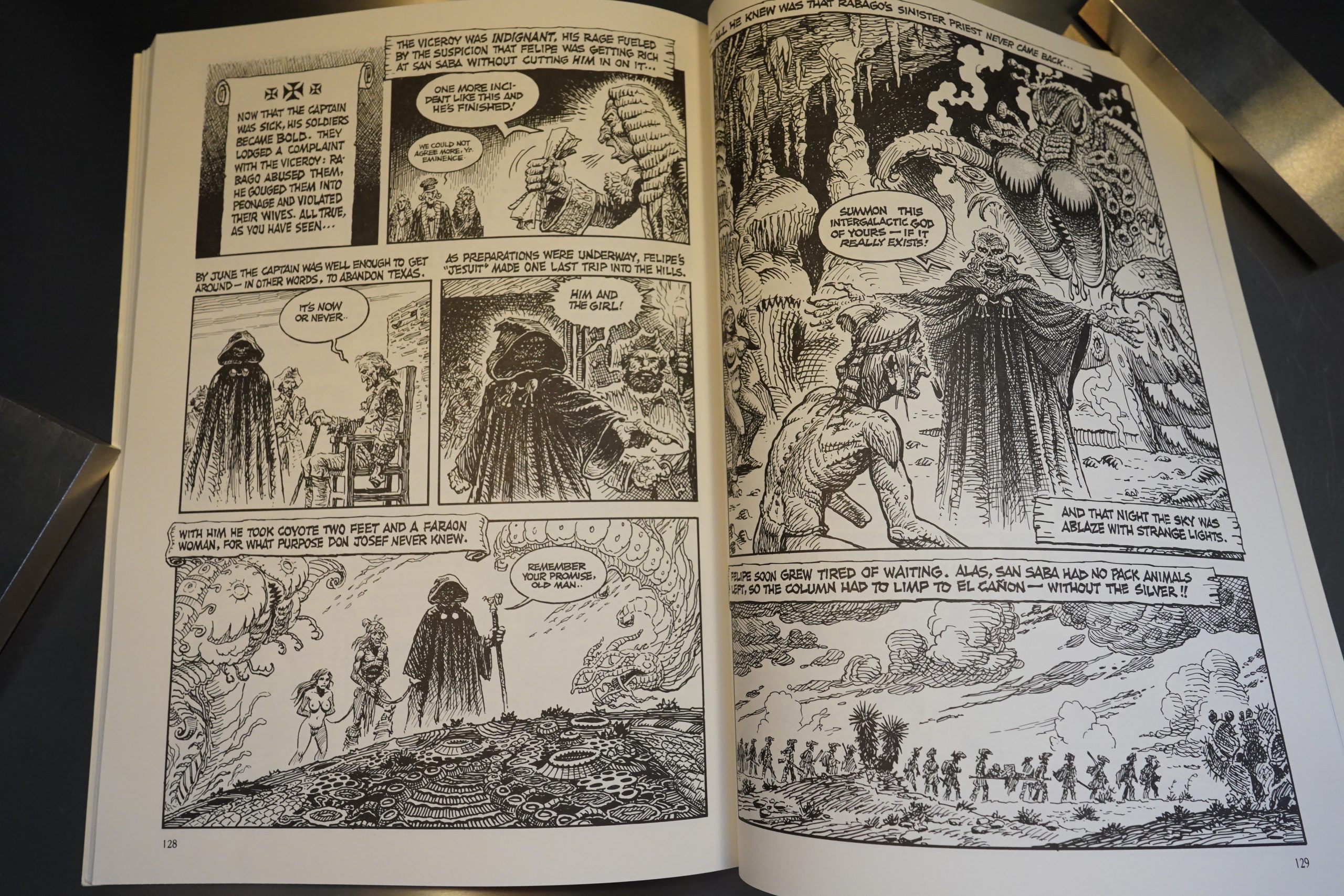

Like the Renegade series, this reprints the magazine-format pages much reduced, and with very large top/bottom margins. Somehow it’s even more unpleasant to read in this iteration, but perhaps my eyes just have gotten even worse over the past year? Because this tends towards the unreadable.

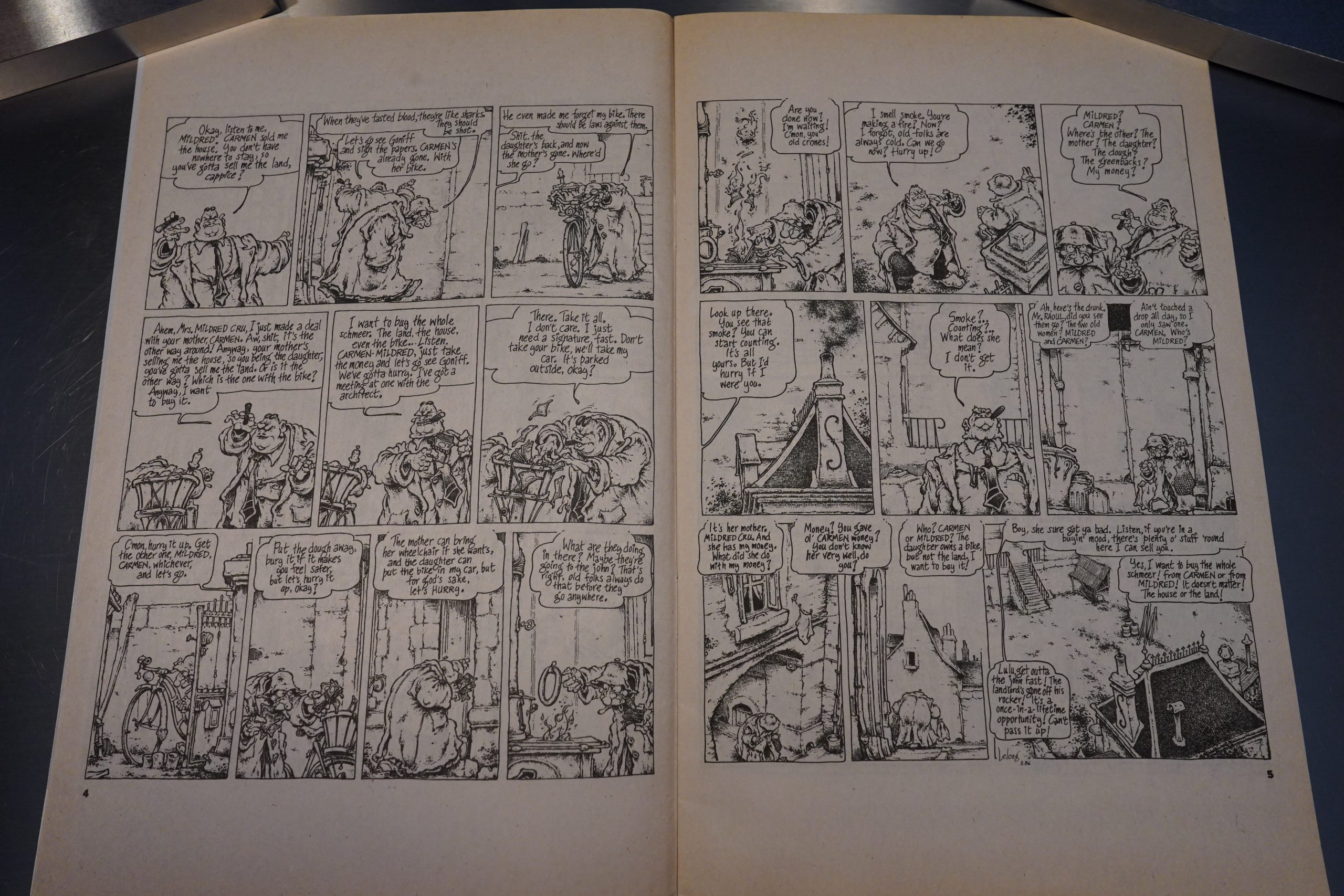

It’s especially bad in series like Carmen Cru (by J. M. Lelong) — it’s so detailed and has so much text that it’s just hard to tell what’s happening when it’s reduced in size like this (and apparently printed with a potato).

(It’s very, very amusing, though, if you manage to actually read it.)

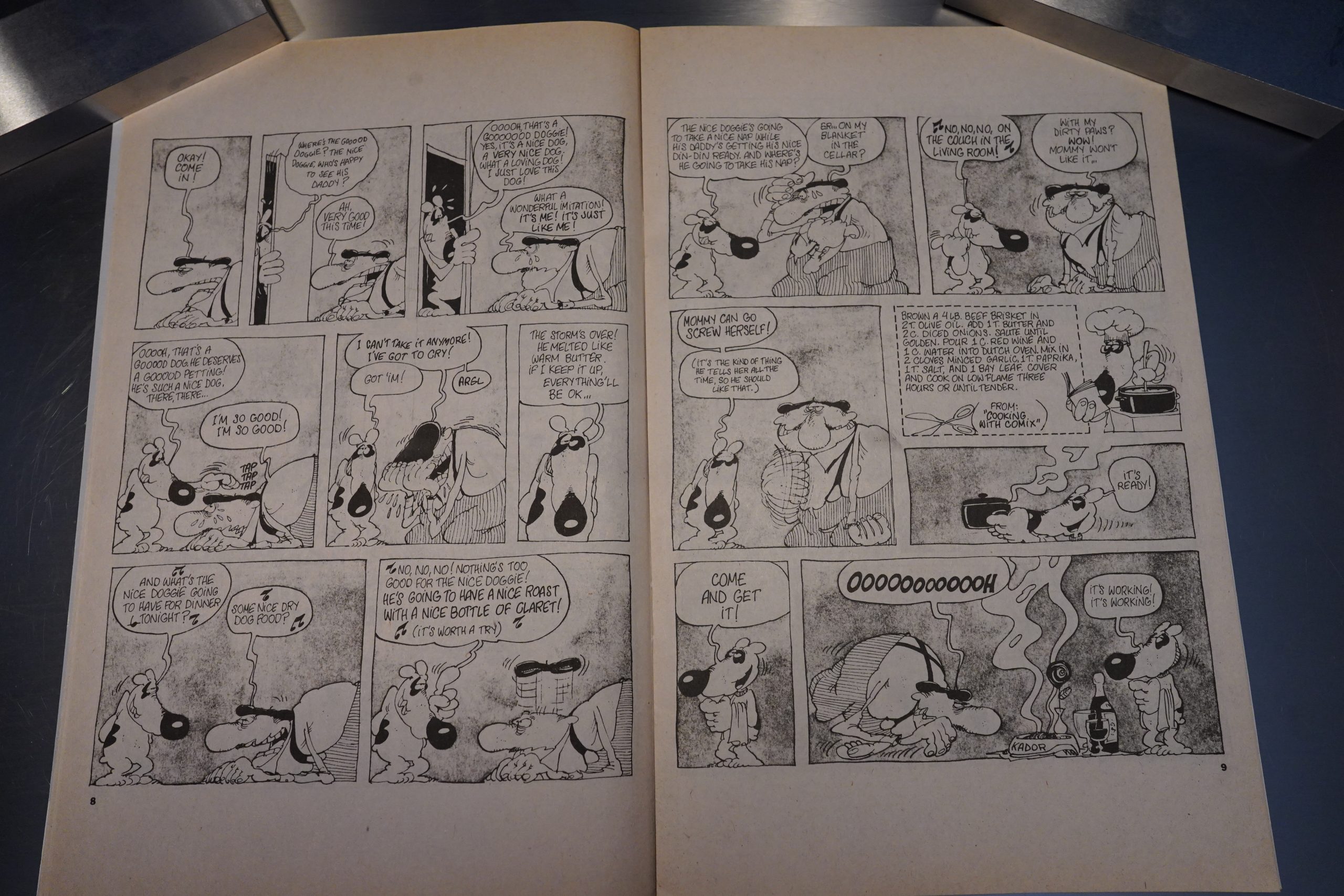

Kador (by Binet) fares a bit better, but… is it really meant to look like this? It looks like there should be grey washes in the backgrounds, but they’re just really splotchy and unsightly.

(But the strip is funny.)

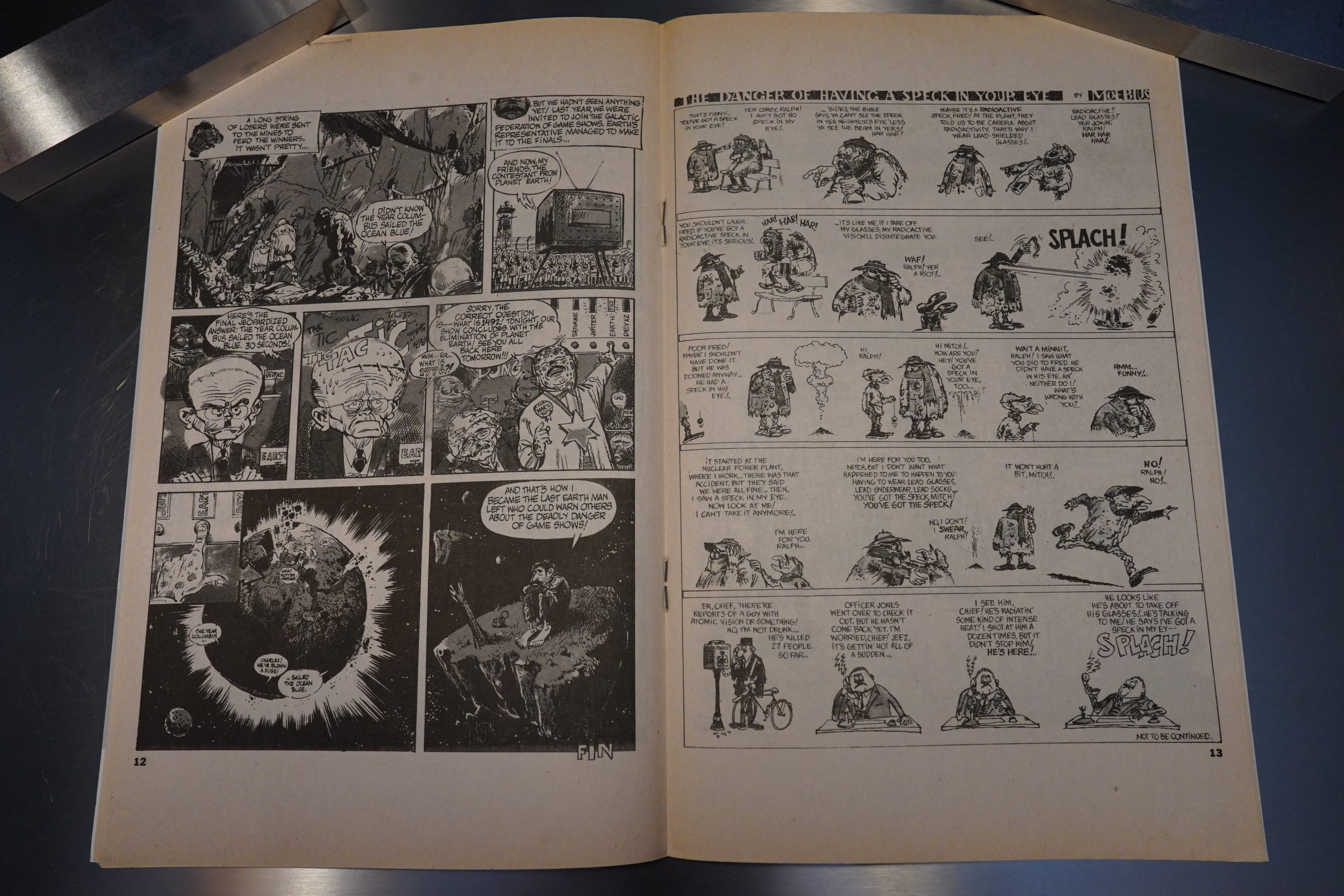

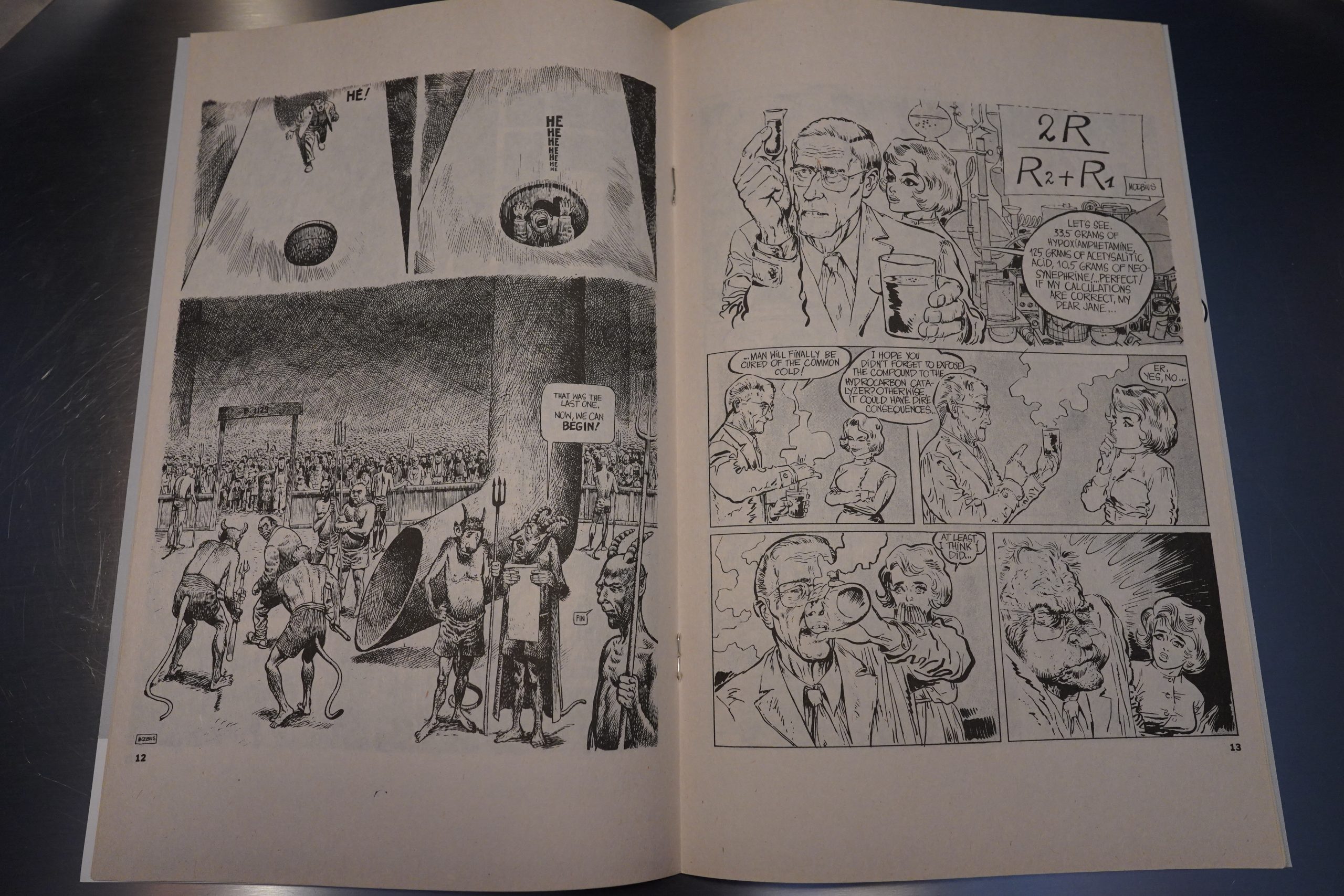

The book also (randomly enough) has a bunch of Moebius stuff… from 1963!!! I’ve never seen any of this before, and it’s a revelation. Moebius was a huge Mad Magazine fan, I guess? I’d never have guessed that this was Moebius by looking at it.

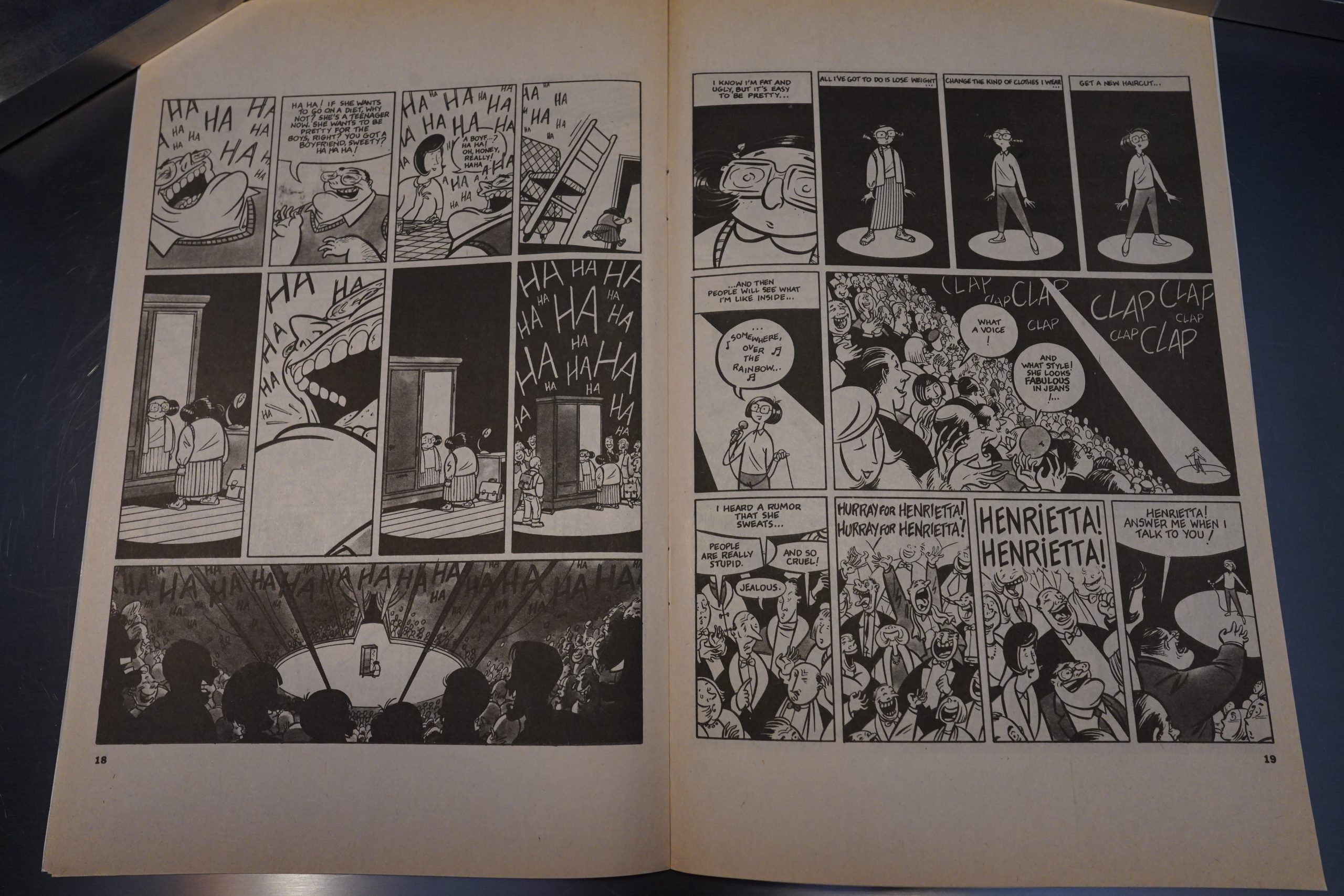

This is Dupuy and Berberian’s first strip, apparently — Henrietta? It’s really sweet, and I’ve never seen it before.

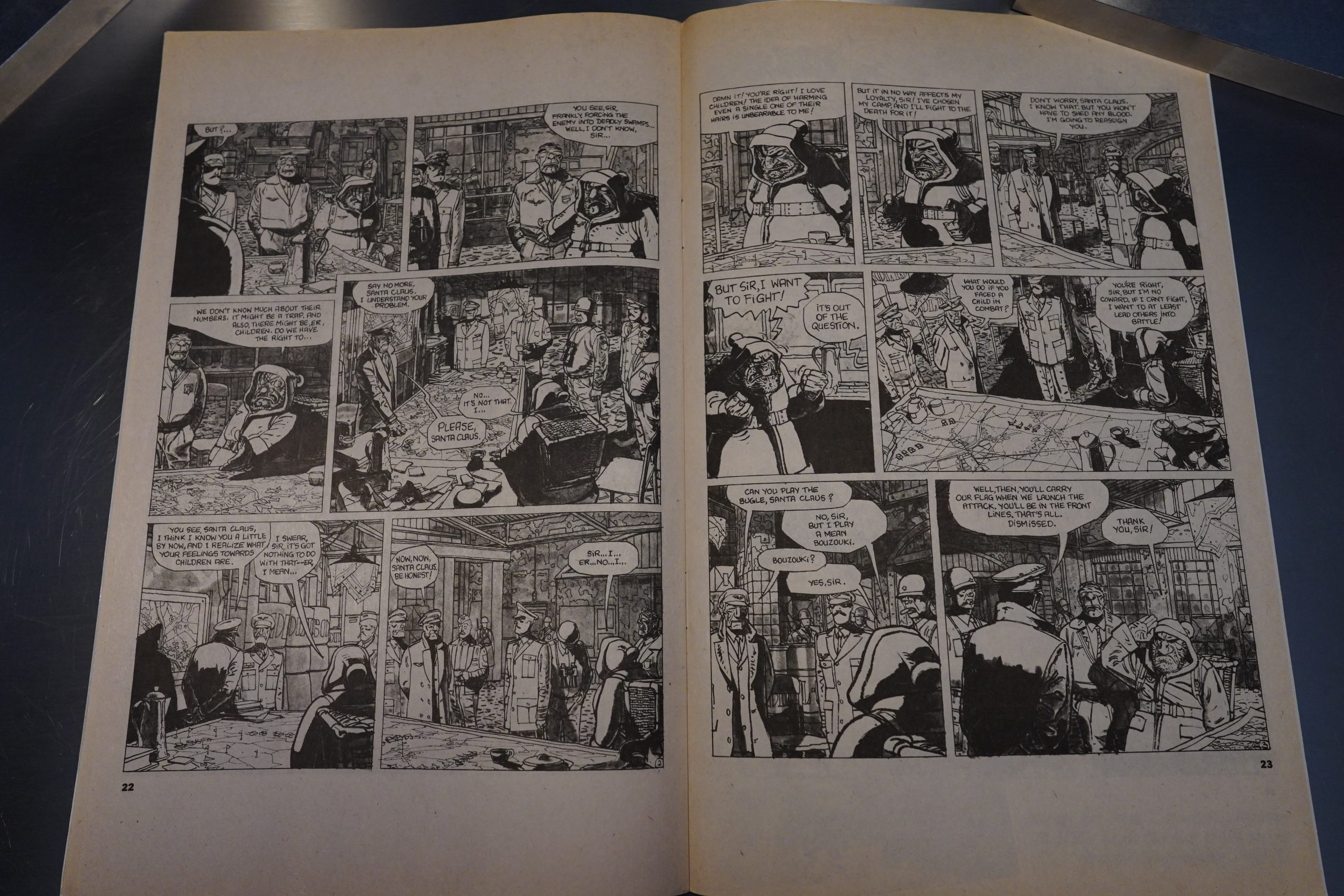

The Sgt. Claus strip (by Gossens) is very high concept: “What if Santa Claus was in the military?” But once you’ve heard the concept, you don’t really need to read the strip, because that’s the joke.

And it’s such a strain to read in this reduced format.

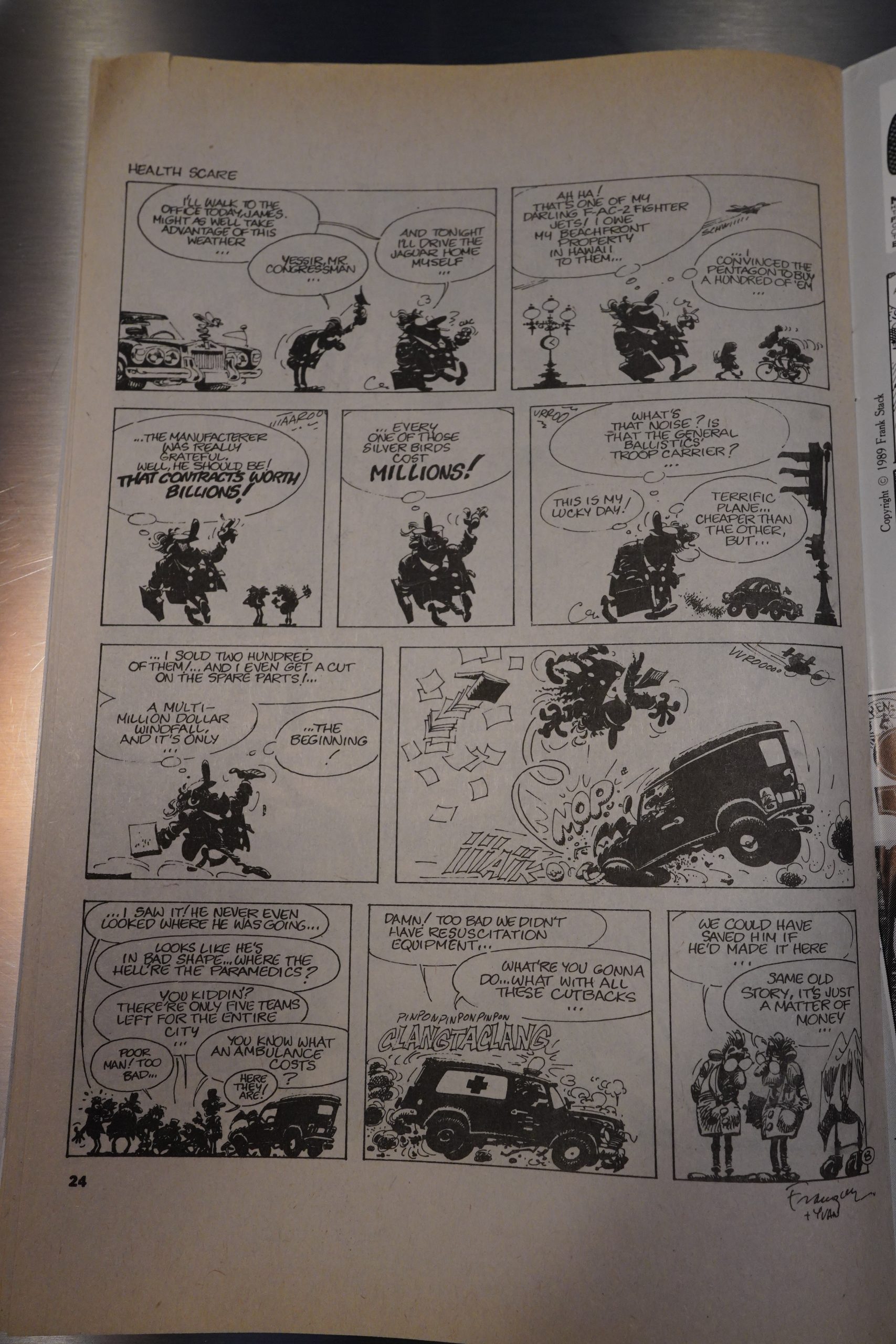

Finally, we have a Franquin Idees Noires page.

So… The issue is chock full, and it’s all good stuff, but it’s still not a good read. I know, I’ve been harping on the format, but it’s just hard to get past that. But in addition, there are so many features in this 24 page book that it’s just hard to get any feel for any of the features. It feels cramped and odd.

Wow… more Moebius from (around) 1963. Amazing. I mean, amazing that the Moebius we know and love drew like this once, and then stopped drawing this way.

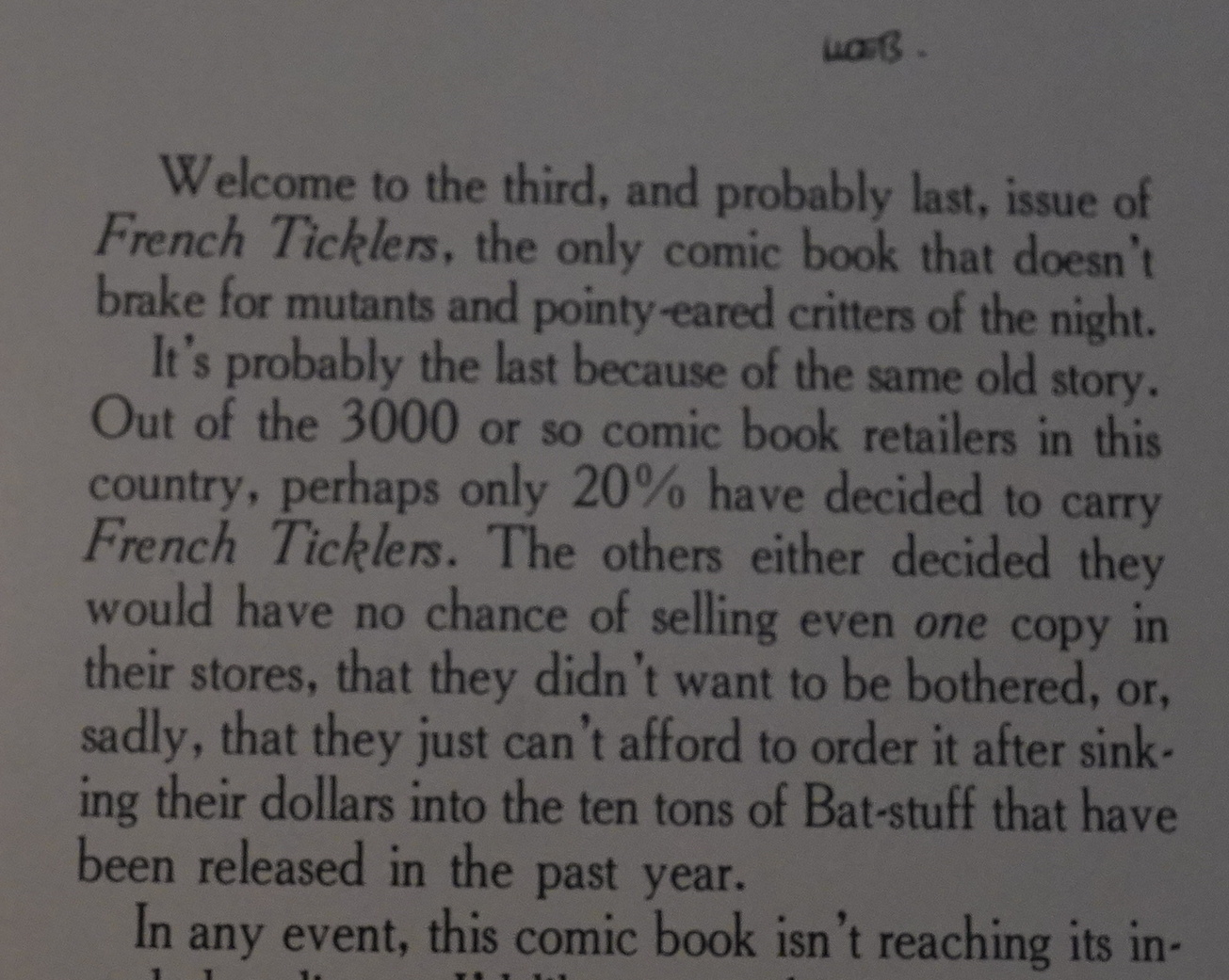

Surprising nobody, the book was cancelled due to low sales.

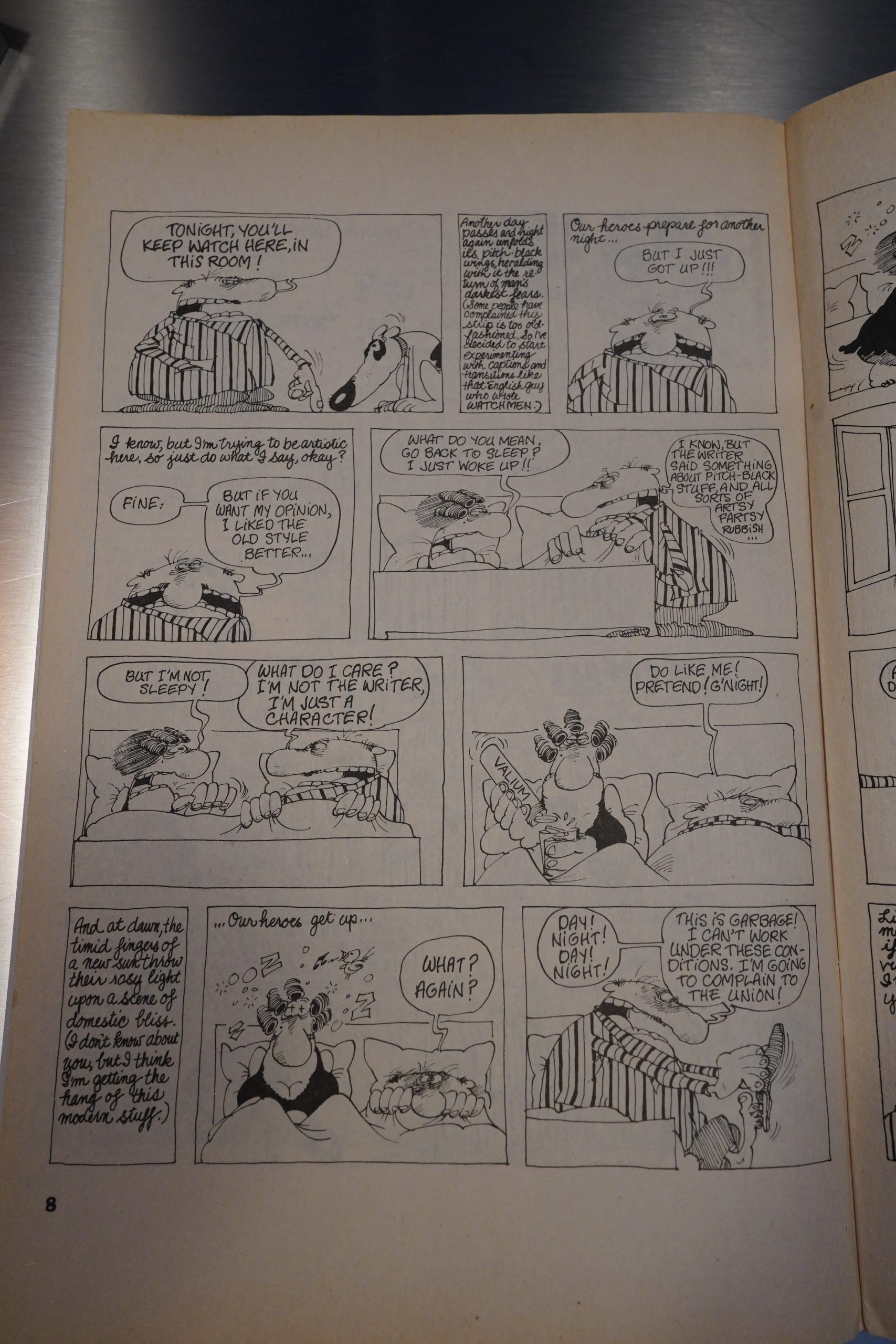

But this is more surprising: Kador takes on Watchmen and/or Dark Knight.

Craig Pleeth writes in Amazing Heroes #174, page 85:

Variety may be the spice of life, but

it’s not the spice of the comics indus-

try. Except around the halls of Kitchen

Sink Press.

The first issue of their new series

French 7icklers contains eight stories

by some of the best creators in French

comics. Presented here are some in-

teresting stories that should be brought

to the attention of any serious comics

aficionado.

The variety of material alone puts

most American creators (and publish-

ers) to shame, as there isn’t one story

that features a long-johned vigilante.

The closest thing to a caper we get is

Santa Claus.

The delicately rendered Carmen

Cru story by Lelong accomplished

more in five pages than a year’s Morth

of anything by Chris Claremont. A

sense of character and timing is effort-

lessly brought home during a greedy

land developer’s play at getting the

notorious bag lady’s land.

The Kador strip by Benet, which

features an incredibly smart dog brid-

with incredibly dumb masters, has

the look and flavor of a strange ani-

mated short. “Henrietta’s Diary”

Dupuy & Berberian brings together a

rather strange story (at least for Amer-

ican comics) coupled with a fantastic

visual telling of the tale.

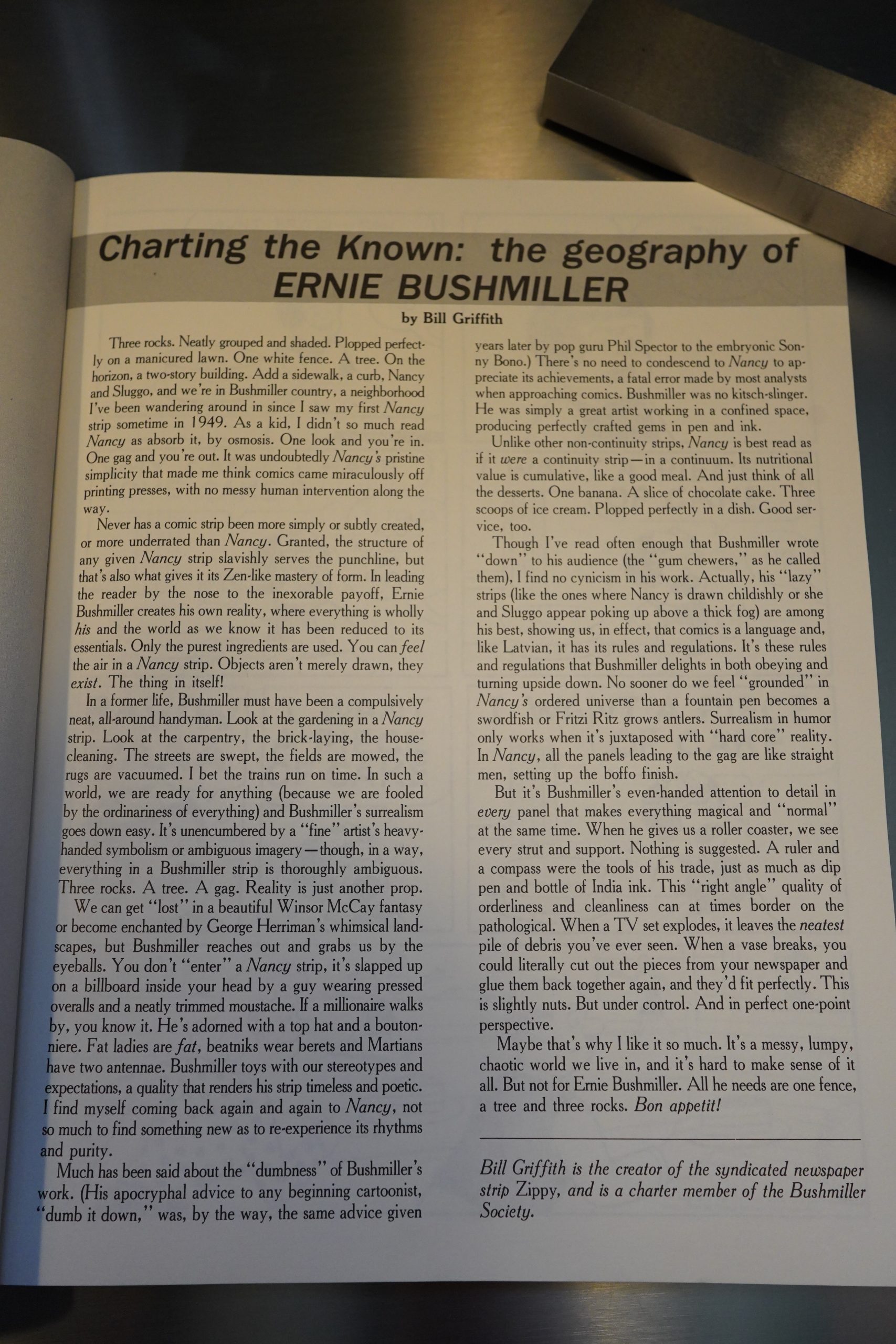

The most interesting pieces come in

the form of three never-before trans-

lated “Moebius Strips” from the ’60s

by famed creator Jean Giraud. Two of

the stories are done in a Harvey Kurtz-

man-Will Elder-MAD Magazine style,

while the third looks like something

more akin to the sequential art of Will

Eisner.

Though the ideas and artwork

expressed in French Ticklers are more

inspired than your average American

comic, the humor of the var-

ious strips does lose something in the

cross-cultural chasm that exists be-

tween Yanks and Frogs. However, the

obvious skills of the creators shine,

and, most importantly, you don’t have

to shriek and laugh out loud to appre-

ciate the work presented in this book.

Once again Kitchen Sink has spiced

up the comic racks. Let’s hope they

keep French Ticklers coming and

dreaming up books aimed at adults.

This is the one hundred and eleventh post in the Entire Kitchen Sink blog series.